Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 16

May 19, 2025

Kit Robinson, Tunes & Tens

Known as one of the formativefigures of the Bay Area Language poetry movement, Kit Robinson’s later poetry isin my mind some of his best, and his latest addition Tunes & Tens isno exception. During his years employed in the burgeoning tech industry in the80s and 90s, Robinson embedded his poetry in the interstices of his working dayby writing on the job, a practice Michael de Certeau called “la perruque,” the Frenchterm for a worker’s own work disguised as work for his employer. At times, thisinvolved sampling computer jargon and business-speak and torquing it towardcontrary ends that released it from its productivist logic, while at the sametime integrating references to business travel (airports, hotel lobbies) andhis daily commute. Rather than situating his poetry outside the labor thatdominates our day-to-day lives, confining it to solitary retreats freed from materialconcerns, Robinson situated his practice squarely inside the machine,what his colleague Robert Grenier called “the counting house,” referring to hisown job at a corporate law firm in the Bay Area at the time.

Now in retirement, references to Robinson’s travelscontinue but the language of the workplace has given way to the rituals of hisday-to-day life, which includes practicing and performing in Calle Ocho, anAfro-Cuban charanga band in which he plays the tres, an acoustic guitar withthree doubled strings. It’s only natural then that the first section of Tunes& Tens begins with a series of poems written “after” jazz titans likeHenry Threadgill, Thelonious Monk, Don Cherry, Carla Bley, and Billie Holiday,as well as the great late, dear friend of the poet’s, Lyn Hejinian, to whom thebook is dedicated. (Tim Shaner, “On Kit Robinson’s Tunes & Tens”)

Iwas curious to see the latest collection by Berkeley poet Kit Robinson,

Tunes& Tens

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2025). Despite having heard his namearound for some time, this is the first collection of his I’ve seen, and I’mappreciating very much Tim Shaner’s introduction, which does provide some helpfulcontext, especially for a collection that provides a shift through Robinson’slarger work, responding to Robinson’s own shifts into retirement from regularemployment. “I think to write freely,” the poem “BEAUTIFUL TELEPHONES,”captioned “after Carla Bley,” begins, “Like Spinoza / But not in Latin /Rather a dessicated English / Is my preferred medium / Bits of history / Clingto the underside of speech / A ray of hope in a glass tube [.]”

Iwas curious to see the latest collection by Berkeley poet Kit Robinson,

Tunes& Tens

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2025). Despite having heard his namearound for some time, this is the first collection of his I’ve seen, and I’mappreciating very much Tim Shaner’s introduction, which does provide some helpfulcontext, especially for a collection that provides a shift through Robinson’slarger work, responding to Robinson’s own shifts into retirement from regularemployment. “I think to write freely,” the poem “BEAUTIFUL TELEPHONES,”captioned “after Carla Bley,” begins, “Like Spinoza / But not in Latin /Rather a dessicated English / Is my preferred medium / Bits of history / Clingto the underside of speech / A ray of hope in a glass tube [.]” AsShaner speaks of in his introduction, the collection is built in two halves:the “Tunes” section, offering a selection of self-contained poems, each ofwhich are composed as respond poems, sparked by the music of a variety of jazzgreats, Cuban bands or the work of the late American poet Lyn Hejinian, and the“Tens” section, “a serial poem comprising 73 ten-line stanzas or decimas,” eachof which riff their own reactions to an array of very different prompts, whetherreferenced or otherwise. Composed from January 2, 2023 through to November 17of that same year, each poems offers a casual and clear glance that landsstraight at the heart of the matter, writing meditations and clarifcations thatmight even echo short essays, comparable, in certain ways, to Anne Carson’sinfamous Short Talks (Brick Books, 1992). “Off the coast of France nearCherbourg / Is an important battle of the American Civil War,” he writes, to open“XXIV,” “The U.S.S. Kearsarge attacked and sank / The Confederate boat theC.S.S. Alabama / On June 18, 1865, an event depicted / By Edourard Manet in hisfirst known seascape / And first painting of a current event / The picture wasdisplayed in the window / Of Alfred Cadart’s print shop in Paris / Barely amonth after the incident took place [.]” There’s almost an element of Robinson’swork that provides an echo of surrealist poets Stuart Ross or Ron Padgett, butwithout the surrealism, offering curious turns and a deceptive smoothness tothe lyric that underplays its nuance, even as Robinson alters phrases akin to atrick of the light. Later in the sequence, as poem “LV” reads, in full:

The idea of writing andwriting are not the same

The idea of a river and ariver are totally different

A river requires tributariesand a mouth

An idea needs someone tooccur to

The mouth is speaking butit’s only words

If I could, I would singyou a melody so mild

How many different kindsof bird have occupied these

trees?

The idea of a poem and apoem are next door

neighbors

There is no such thing assilence

Someone or something isalways making a sound

May 18, 2025

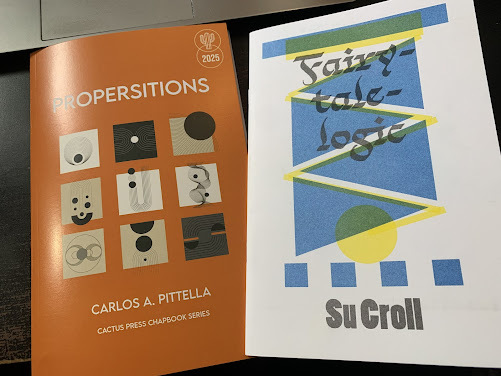

Ongoing notes: mid-May, 2025 : Carlos A. Pittella + Su Croll,

You are keeping track of the above/ground press substack, yes?

I mean, I’m notattempting to post there too often, but I am running a new series of authorspotlights once a month or so. Who might be number three?

And the ottawa small press book fair is but weeks away!

And I’m going to keep pushing the above/ground press postal increase sale until you order something(or the sale ends

; whichever comes first).

You are keeping track of the above/ground press substack, yes?

I mean, I’m notattempting to post there too often, but I am running a new series of authorspotlights once a month or so. Who might be number three?

And the ottawa small press book fair is but weeks away!

And I’m going to keep pushing the above/ground press postal increase sale until you order something(or the sale ends

; whichever comes first).Montreal QC: I was very excited to see Montreal-based poet Carlos A. Pittella’s second poetry chapbook in English, PROPERSITIONS (MontrealQC: Cactus Press, 2025), following his English-language above/ground press debut last summer. I’m appreciating Pittella’s play and sense of line break andrhythm, such as the poem “BETWEEN / IN CASE THEY RUN / YOUR LICENCEPLATE” that begins: “Once I broke my front tooth / out of a poem & stillhave the chip / to show—not a great poem but it tasted / like bone it was real Iremember / the pain & the scar-tissue/ of writing it that became my face.” There’s such a lovely propulsion to Pittella’slyrics, one with a stagger and staccato very nicely employed through those linebreaks and spaces. Held as a kind of call-and-response, or Greek chorus, thereare five “properstitions” poems, numbered via Roman numerals, each with a kindof aside or counterpoint follow-up poem. As the poem “PROPER / STITIONS 1” reads:“I wanted to carve my home mine / with a physical word on the wall & beyond/ hope of getting a deposit back / but I wanted my own alphabet since / neitherlandlord nor family / would understand it anyway. Would you?,” the second poem,“FROM / LATIN, / BIBER,” begins: “beer this verb to be anaftertaste / bitterness my father said / you gotta learn how to love / same ascoffee no one likes / at first he thus expounded [.]”

Edmonton AB: It is interesting to see titles by a new Canadianchapbook publisher, Edmonton’s Agatha Press, run by Matthew Stepanic, a presswith exquisitely-designed titles in limited edition. The eighth title through thepress is Edmonton poet Su Croll’s Fairy-tale logic (2025), an assemblageof poems produced in a numbered edition of one hundred copies. The poems in Fairy-tale logic are composed across familiar fairy tale narratives, but across verydifferent perspectives. “Imagine you are a bad mother.” she offers, to open thepoem “Imagine the poison,” “You are an evil step-mother. // Imagine the face inyour magic / mirror announces you can grow // younger if you eat your beautiful/ step-daughter’s heart // boiled and sprinkled with salt.”

Boast

It was a boast that beganthis

whole bouleversé world.

The boastful father’sfalse

claim of his daughter’sskill,

the lie that she couldspin

gold from grass or leaves

or straw. The yellow ofit

transformed. Transformed.

Yet it was the father

who disappears so completely.

In the end, he was noteven

at church to give thisgolden

package of a bride away

to her new master.

Theysay old stories take on the purpose and character of the times they are told,the speaker of those stories, and Croll offers her unique take on a history ofvariations that might never be exhausted. There are multiple examples one cancite over the years through contemporary poetry—from British Columbia poet Ruth Daniell’s TheBrightest Thing (Caitlin Press, 2019), to Louisiana poet Lara Glenum’s SNOW (NotreDame IN: Action Books, 2024) [see my review of such here], Jessica Q. Stark’s Buffalo Girl (RochesterNY: BOA Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here], Katie Fowley’s TheSupposed Huntsman (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) [see my review of such here]or even Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster’s Three Bloody Words (above/ground press, 1996;2006)—most of which engage with elements of female agency or lack thereof,throughout so many of at least those European-originated tales (such as popularizedby the Brothers Grimm). There’s a curious way that Croll’s narratives bob andweave in and around and through well-familiar narratives, her own perspectiveproviding either highlight unexplored moments or simply question the narrativeswe’ve all taken for granted. “Why does the king need straw / spun into gold?”the poem “Questions for Rumpelstiltskin” begins, “He’s the king. / Doesn’t theking have all the gold / in the kingdom? Doesn’t the king / have more gold thanhe knows / what to do with?”

May 17, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Christy Climenhage

Christy Climenhage is the authorof The Midnight Project (Poplar Press (Wolsak & Wynn), 2025). A fullmember of SFWA and CSFFA, she holds a collection of graduate degrees (PhD and 2Masters) in International Political Economy, European Administration and SocialSciences from a past life and alternate existence as a social scientist,academic and diplomat. When she’s not writing you can find her in a forest inQuebec walking her dogs.

1 - Howdid your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

TheMidnight Project, which comes out in May 2025, is my first novel. I can’t really understatehow life changing I feel this is. Its publication represents crossing the Rubiconand shifting from an unpublished writer trying to sell a book I wrote in thedark to an author with a publisher and an agent. This transition into thebusiness of writing and publishing feels very transformative. Of course, nothing has practically changed forme at this moment, except I’m a person who writes and publishes thingsnow.

2- How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Ifirst came to fiction as a child when I started reading. I read early and oftenand devoured chapter books from a young age: Stuart Little and Charlotte’sWeb were the earliest books I remember. Then, ravenously, I read just aboutanything. I would imagine characters and dialogue. I’ve always been a reader.

Howdid I come to writing fiction? I always wrote a bit, had a story going. I wrotepoetry too but it didn’t grab me the same way. I went to university and thengrad school, and I pivoted to academic writing and non-fiction. Non-fictionfelt grown-up and serious. I dabbled infiction when inspiration struck (which is to say, hardly at all) but didn’t tryto publish, or indeed, finish anything.

Theway I came to writing fiction, in the end, was by force of will—by a singulardecision to undertake and finish projects and try to share them.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Theidea needs to germinate first. It usually begins with a phrase or a sentence.The phrase can come to me in front of my computer but more often when I’mwalking the dogs or driving the car. But then it niggles until the storyunfolds. I have ideas from years back just waiting for the spark to turn itinto a project but this part of the process can’t be forced. Short stories area much easier, much more linear process than novels. It’s so simple to write ashort story, be dissatisfied and put it aside, then come back to it, than witha novel.

Bythe time I am committed to sitting down and writing a novel, the words of thefirst draft come fairly quickly, but the first draft is quite different fromthe finished work, which takes a few more re-writes to polish into shape. I trynot to get bogged down with research while I’m writing a first draft. Though Ido a lot of reverse outlining and research for draft 2.

4 - Wheredoes a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Myprojects are stories and I usually know when I start whether they are “little”stories or “big” stories, but I can always be surprised. In general, my novelsare novels from page one, and I approach them in a fairly linear way, but I’mat the beginning of my career as a novelist so this may change.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Theyaren’t currently part of my creative process because I haven’t done any. So I guess we’ll see.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Thesame things that interest me about the world show up in my fiction. I’mfascinated by political movements, economic systems and how human relationshipsare the bedrock of society. Some themes, like the role of late-stage capitalismand science in shaping society are embedded in my novel The Midnight Project,as well as how people react to crisis, especially ecological crisis. Thosethemes as well as colonialism are figuring heavily in my current work inprogress.

Thecurrent questions for me are: how do we live well (and ethically) in a world indecline? How can we connect better with each other? How can we resist thestorm?

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writershave a central role in shaping culture but it isn’t usually intentional. Thewondrous thing about writers is there are so many roles they can take on, andtheir works can play, out in the world. Writers can entertain, inform, provoke,bolster or assuage. They can educate; they can inspire. Different writers cantake on different roles too. Not every work has to save the universe–sometimesit’s okay to just provide a little humour or comfort. Our culture can beprofound and thoughtful while also being goofy or funny. Writers are criticalto creating culture but I think this is an organic rather than architecturaleffort.

8 - Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

Workingwith an editor has been both challenging and incredibly rewarding. That extraset of professional eyes on your work trying to bring out the best in it issuch a privilege to have. But the self-reflection required when you have tolook at parts of your work that may not be working for your reader takes alot. You need to (a) re-write itaccording to the advice you’ve been given; (b) cut it out completely; or (c)defend it with your whole heart; it’s really difficult to work through what todo. You have to be fair and thoughtful and open but also know where you can’tcompromise. It’s a conversation and you have to hold up your end.

9 - Whatis the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Writingadvice and publishing advice are two different things.

10 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? Howdoes a typical day (for you) begin?

Ihave a lot of life that infringes on my writing so I either schedule time earlyin the morning or I write on the margins of other things. So a typically goodwriting day would start early with coffee and CBC News, then write for an hour,then do all the other things.

11 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

Thebest action to take when I’m stalled is to sit down and write anything. Badprose can always be turned into better prose through re-writing but waiting forinspiration to strike can mean you lose weeks getting the story down.

WhenI get stalled, I also do a quick check on whether I am writing the thing in myhead. When inspiration is flowing, my characters will lurk in the corners andrandom ideas and dialogue will come to me at all hours. If that dries up, Ineed to ask – am I writing the right thing? How can I get the words down?

Regardinginspiration, that can come from anywhere at anytime – during a walk in thewoods, a random conversation, a private reflection on the world or society.

12 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Sunscreen,pine needles and wet dog.

13 - DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Scienceand music. I always have a playlist for a work in progress. The natural world andadvances in science tend to be an influence.

14 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I takea lot of inspiration and enjoyment in the Canadian speculative fictioncommunity. We have so many award-winning and best-selling science fiction andfantasy authors. And when I’ve met them in person they tend to be really nice!

Ialso have a kickass writing circle of amazing authors. We critique each other’swork, as well as support each other through the querying and submissionprocesses. Their feral enthusiasm has really made the publishing journey fun. Beingable to connect with other writers helps to lessen the feelings of writing intoa void.

15 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’dlike to collaborate more with other writers. And write more books, of course. Ihave a lot more books in me to write.

16 - Ifyou could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Forme, being a novelist is the fantasy occupation. In my professional life I’vebeen a student, an academic, a teacher and a diplomat. All these things havecontributed to who I am and has percolated into the kind of writer I am today.But for me, the dream is to be a full-time author.

17 -What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Therealization that only I could write the story in my head. And if I didn’t, itwouldn’t get written.

18 -What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Sohard to pick just one, and I don’t really have favourites…

Film:Mary Shelley. A really interesting biopic about the life of the author ofFrankenstein.

Book:Countess by Suzan Palumbo. Anti-colonialist, sapphic space opera novella.I’m really looking forward to what she writes next in this universe.

19- Whatare you currently working on?

I’mworking on two things – a novel set in the same time period and world as TheMidnight Project. I’ll get back to it when my brain organizes and separatesreal-life and fictional dystopias.

Andthen I have a fun project about middle-aged feminist rage that makes me smilewhenever I take it up.

May 16, 2025

Spotlight series #109 : Terri Witek

The one hundred and ninth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring American poet and asemic artist Terri Witek

.

The one hundred and ninth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring American poet and asemic artist Terri Witek

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau, Indiana poet Nate Logan, Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn, North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson, award-winning poet Ellen Chang-Richardson, Montreal-based poet, professor and scholar of feminist poetics, Jessi MacEachern, Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell, San Francisco poet Micah Ballard, Montreal poet Misha Solomon and Ottawa writer and editor Mahaila Smith.

The whole series can be found online here .

May 15, 2025

the ottawa small press book fair, spring 2025 edition: June 21, 2025

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

the ottawa

small press

book fair

will be held on Saturday, June 21, 2025 at Tom Brown Arena, 141 Bayview Station Road.

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:

the ottawa small press book fair

noon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$25 for exhibitors, full tables

$12.50 for half-tables

(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: due to demand, we offer half as well as full tables (because not everyone needs a full table, and this allows more exhibitors to participate).

To be included in the exhibitor catalogue: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming Ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by June 10th if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And we're doing the pre-fair reading as well at Anina's Cafe! see info here!

: and we're on Bsky now! that's exciting, yes? follow us!

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, although preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by exhibitors including: above/ground press ; Anvil Press / A FEED DOG BOOK ; Apt. 9 Press ; Arc Poetry Magazine ; Manahil Bandukwala ; battleaxe press ; Jessica Bebenek ; Book*hug Press ; Bird Lips Zine ; The BumblePuppy Press ; Bywords ; Dave Cooper ; CreateSpace ; Amanda Earl ; Dr. Softpaws' Fur-Imagination ; Elliott Dunstan ; equitableEducation.ca ; flo. lit mag ; Good Golly Zines ; The Grunge Papers ; John Haas ; Seymour Hamilton ; Heartlines Spec ; Horsebroke Press ; Shirley MacKenzie ; Robin Blackburn McBride ; Patricia McCarthy ; Kersplebedeb Publishing (LeftWingBooks.net) ; Paragon of Virtue Press / la presse POV ; phafours press/Writebulb app/Pearl Pirie ; Proper Tales Press ; Puddles of Sky Press ; Raccoon Comics ; Claudia Coutu Radmore ; ROOM 3o2 BOOKS ; Sarah's Zines ; Simulacrum Press ; shreeking violet press ; swooncor ; Tel # Publishing ; Things in my Chest ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] ; Turret House Press ; Alberte Villeneuve-Sinclair ; Wyrdsmyth Press ; etc etc etc.

the ottawa small press fair is held twice a year (apart from these pandemic silences), and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. Unfortunately, we are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

And don't forget: the fall event (31st anniversary!) has already been announced for Saturday, November 22, 2025;

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table.

May 14, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Thomas O'Grady

Thomas O’Grady was born and grew up onPrince Edward Island. He is Professor Emeritus at the University ofMassachusetts Boston, where he served as Director of Irish Studies from 1984 to2019. He was also Professor of English and a member of the Creative Writingfaculty. He is the author of three books of poems, What Really Matters (2000) and Delivering the News (2019), bothpublished by McGill-Queen’s University Press in the Hugh MacLennan PoetrySeries, and Coming Ashore: New & Selected Poems (2025),published by Arrowsmith Press in Boston. He is currently Scholar-in-Residenceat Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

On an earthy level, I’ll admit that for a guy growing up on PEI, thephrase “published poet” rang almost as magically as “NHL defenseman” or “leadguitarist.” On a loftier level, holding What Really Matters in my hands,I felt a certain sense of arrival—and of affirmation that maybe I had somethingto say that was worth saying. But then 19 years passed before the publicationof my second book, Delivering the News. Tellingly, I suppose, the“Selected Poems” of Coming Ashore: New & Selected Poems includes only15 poems from the first book and only 20 from the second. I’m not disowning allthe rest, but I feel that the ones that I’ve included resonate moreconsistently with the 55 (or so) “New Poems” gathered in Coming Ashore underthe title Nuages. With What Really Matters, some of the poemsI’ve omitted seem more “earnest” now than they did when I wrote them. In Deliveringthe News there are poems that I still love that seem now more “of theirmoment,” so they got sidelined. I think that Nuages has more poems thatare built to last. Time will be the judge of that.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

I published a couple of short stories before I committed to writingpoems. I still write fiction, but the writing of poems—short-ish lyric poems,to be exact—fit more neatly into my available time: I was an IrishStudies/English professor with an ambitious scholarly agenda (which I’mmaintaining in retirement), and my wife and I also had a very full domesticlife with three daughters underfoot (literally) when I was setting out. But Iwas also teaching a lot of poetry in my literature classes, so I think I gravitatedtoward that genre because it was very much in the air I was breathing . . . andI felt comfortable breathing it, both inhaling and exhaling.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

For me, poems are like cats—they appear mysteriously and unannounced. Igrew up with cats, and my wife and I are currently on our third and fourthcats, beautiful sisters, and I pay close attention to feline quidditas.Likewise, I pay attention when I feel a poem stirring in me: of course I try tocoax it into being, but sometimes I have to let it emerge on its own terms andin its own good time. That being said . . . I’ve written poems in one sitting,and I have poems that have sat silently inside me for years, even decades,before they start to show themselves.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I never sit down with the express intention of writing a poem. Mypoems can start with a word, with a sensation, with a vague memory that hasbeen randomly triggered, with an emotion. Once I jot down a phrase or a line, Imight be off to the races . . . or I might not. None of my three books of poemsstarted out with even the slightest notion of a “book” in the offing: I writeone poem at a time. Eventually the poems accumulate (sometimes I feel likethey’ve bred like rabbits behind my back) and then I try to herd them into somesemblance of order. With each of my books I’ve recognized through that processof herding that there are certain themes or motifs that recur, and I’m happy tohear the poems shout out to each other either in a sequence or sometimes acrossa distance of many pages.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’m very happy to share my poems by way of readings. For me a reading isa social occasion (friends, family, kindred spirits), and the poems are mostlyjust “the occasion” for that larger occasion. My poems tend to be short—muchshorter than the stories I tell to set them up!—so I think they’reaudience-friendly for on-the-spot ingestion. Also, I think that when hearing mypoems read aloud, an audience can more easily tune in to my natural tendency asa writer to work, or play, with the intrinsic musicality of language. But,frankly, when I’m writing a poem I’m not thinking of an audience: I’m thinkingabout the poem, of trying to get it right. I recently came upon, and wrotedown, this observation by Seamus Heaney: “the onesimple requirement—definition even—of lyric writing is self-forgetfulness.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I read widely, and I am open to all sorts of poems even if they aren’tthe sort that I might write myself. I would never prescribe or proscribe forother writers what poems should or shouldn’t do or be—they either speak to usas readers or they don’t. Do they or don’t they—that is the question! In thecase of my own poems, I recognize, and admit unabashedly, that I am at least acollateral descendant of poets in the Irish lyric tradition—but with a PEIaccent. From the start, my poems have mostly steered clear of highfalutin’ orobscure diction, though I don’t shy away from a rich sonic texture (alliteration,assonance, consonance, internal rhyme) or even from a sonic structure like aformal rhymed sonnet. I’ve written a lot of sonnets—maybe more than my fairshare—but the abiding lesson I’ve learned from working with fixed formsinvolves the reciprocal relationship between the formal structure and therhetorical structure of a poem. As I work on a poem, I eventually becomeconscious of the movement of an idea through the movement of the words and thelines and then try to shepherd everything toward satisfying closure.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

Robert Frost purportedly said: “Poetry is about the grief, politics about the grievances.” In ourpolitically, socially, and culturally fraught day and age the boundary linebetween grief and grievance seems not only blurry but perhaps fluid. But I worrythat some writers (and readers) give too much credit to poetry’s capacity toredress the wrongs of the world. Airing grievances under the guise of poetrymay get the blood boiling, but I subscribe to Zbigniew Herbert’s position: “It is vanity to think one can influence the course of history by writing poetry. It is not the barometer that changes the weather.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I have never worked with an outside editor. I never even took a CreativeWriting course or workshop. I don’t show unfinished work to other writers. Iguess I learned how to write poems simply by . . . writing poems! My wife is myfirst reader, but I never show her what I’ve written until I’m fully satisfiedwith it myself. With Coming Ashore, the publisher/editor made only onesuggestion, which I accepted—that the “New Poems” section be titled Nuagesas a nod toward the poem with that title which is itself a nod toward manoucheguitarist Django Reinhardt’s wistful melody that became the unofficial anthemof the French Resistance during World War II. Did the publisher/editorrecognize that lyric poetry also sings against the darkness of the differentclouds that hang overhead in our place and time? Maybe . . .

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Perhaps this rationalizes my slow process of writing and my modestoutput, but I think often of the advice CzesławMiłosz proffers in a poem titled “Ars Poetica?” that dates to1968: “poems should be written rarely and reluctantly, / under unbearableduress and only with the hope / that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us fortheir instruments.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry tocritical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think it would be overly simplistic to say they use different parts ofthe brain, though there may be some truth to that. Back in my teaching days, Iwould encourage both my Creative Writing students and my literature students toengage with a text by “reading like a writer.” Even as a scholar or a critic I alwaystry to engage with a poem, or a book of poems, or a work of fiction, or lit-crititself on its own terms first: that, I hope, gives me a generous way of takingits measure before I take a more “evaluative” stance toward it. So I suppose thatfor me it’s a first take and then a double-take.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Nowadays, my day starts around 6:50 a.m. with a quick cuppa java beforeheading out with our new puppy tugging at the far end of the leash. Back in theolden days, when we had three highschoolers under our roof, I would set thecoffeemaker for 5:45 and try to get some writing done before the rest of thehouse awoke around 6:45. I like to start pushing words around the screen asearly in the day as possible—usually nothing of substance comes of that, butit’s at least an act of faith. Then during the day I move from project toproject to project—currently, an article on James Joyce and an essay on Heaney,a review of a fine new Irish novel (Colin Barrett’s Wild Houses), afeuilleton about walking the dog that may end up engaging with Polish poet AdamZagajewski . . . But then several mornings each week get interrupted by coffeemeet-ups with friends, though I must say that interruption is a small price topay for a good chat.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Because my teaching career had me on a steady heavy diet of “serious”writing—“literary” fiction, “major” poets, masterpieces of drama, and so on—Ialways kept on hand a good supply of “palate cleansers,” mostly classic noirnovels and international spy thrillers. Page-turners. That’s still the case. Irecently read a couple of novels by Jack Beaumont—The Frenchman and DarkArena—and I’m currently deep into Nick Herron’s Slow Horses . . .I’m also deep into Sebastian Smee’s Paris in Ruins (about the birth ofImpressionism) and I recently read John Higgs’s Love and Let Die (aboutJames Bond and The Beatles) . . . Sometimes, simply coming up for air from theheavy stuff can get the creative juices flowing again . . .

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Well, being from Prince Edward Island—sometimes referred to as “themillion-acre farm,” sometimes as “Abegweit,” from the Mi’kmak word Epekwitk,commonly translated as “cradled on the waves”—I have to acknowledge twofragrances: freshly-turned soil and briny air.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

The natural world has been a steady subject for me pretty much from thetime I started writing poems: landscapes and shorescapes and riverscapes, birdsand animals, the changing of the seasons . . . Ditto for music and musicians—Isuspect that somewhere in my subconscious, guitarists like Wes Montgomery andDjango Reinhardt and fiddlers/violinists like Michael Coleman and Paganini andmarquee artists like Irish tenor Josef Locke and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie are“avatars” for “the poet” . . . And another ditto for the visual arts—woodcuts,linocuts, paintings, etchings, photographs: Picasso and Chagall, Bonnard, DavidBlackwood . . . they all trigger my ekphrastic reflex . . .

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Many years ago, I published an essay in The New Quarterly in whichI wondered what it would feel like to write a poem like Seamus Heaney’s “The Skylight.” Maybe someday I’ll find out, but in the meantime his poems set ahigh standard for me . . . a standard reinforced frequently, I’ll admit, by myongoing scholarly commitment to his total body of work. Another poet whose workI like—I especially appreciate his use of simile and metaphor, but also hisdown-to-earthiness—is Ted Kooser. Early on, Mary Oliver showed me ways ofobserving the natural world: I love her line that “A poem should always havebirds in it”! Although I have no real way to measure this, I feel that myreading of Adam Zagajewski and Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer added some“sinew” to my writing in recent years. At our summer home, we have dozens ofsingle volumes of poems by writers from across the spectrum—I start manymornings there by plucking a random volume from the stack and reading a fewpoems to jumpstart the day. But mostly I read fiction and, increasingly,nonfiction—quite a bit of it involving Paris. I am especially drawn to theperiod of the 1920s into the 1950s. Giants walked the earth in those times.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

In literary terms . . . I feel that I have a lot of fiction in me, bothshort stories and novels, set mostly on PEI. I’d probably have to give up myscholarly life to go down that path, and maybe I will . . .

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

I always aspired to be a musician—specifically, a guitarist . . . When Iwas a highschooler and an undergrad, I developed pretty decent blues chops. Butthen I stopped playing for about 25 years. When I got back in the saddle, Ibecame obsessed with jazz guitar. I took some lessons and then played in anafter-hours combo for 19 years. I probably plateaued just before COVID pulledthe plug on everything, and then I moved a 15-hour drive away from my bandmates.I still have eight guitars, but as a guy in a guitar shop said to me recently,“Is that all?”

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Proximity, perhaps? Osmosis? My father was an English professor—we were avery bookish family! Seven children and we were all readers . . . I don’trecall much poetry in the house, though I have a specific memory that back inhigh school I happened upon Langston Hughes’s poem “The Weary Blues” in ananthology: I typed it out and thumb-tacked it to my bedroom wall—it was awindow into a world far beyond PEI. As it turns out, I followed in my father’sprofessorial footsteps and ended up having a rich 36-year career at a fineuniversity in Boston teaching books that I loved and having the license to workwith words both on the clock and off.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was James Kaplan’s 3 Shades of Blue, atriple biography of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans. The author’smastery of the material was remarkable, but he wore his knowledge lightly andthe writing was compelling. The last great film I watched was Gilda,starring Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford: it was screened in a noir film seriesI’m attending. I had never heard of it before—it was a revelation.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Mostly I’m trying to clear my desk of some of the scholarly projects thatjust won’t let me go. And at the same time, I’m trying to kickstart some of theaforementioned fiction projects. But like the old saying goes, Art is long,life is short!

May 13, 2025

Luisa Muradyan, I Make Jokes When I’m Devastated

Don’t Write Mom Poems

The best writing advice I’veever been given

is to avoid poems aboutmotherhood.

Too sappy. Too sentimental.I agree.

Which is why I only writepoems about

myself bare-chested on ahunt,

dragging my latest kill

back to my cabin

and feasting

on what I can

only describe

as truth. No room in thiscabin

for a nursery or

a metaphorical child

who sleeps when I

sleep and on waking

looks at me not ascreator

but as created, singingsome ancient

song in the moonlight.

Oh,I am very taken with Luisa Muradyan’s incredible second collection,

I Make Jokes When I’m Devastated

(Dallas TX: Bridwell Press, 2025). According to theauthor biography on her website (as this is the first I’ve heard of her and herwork), Muradyan is originally from Odesa, Texas, has a Ph.D. in Poetry from theUniversity of Houston, currently lives in the United States and is also theauthor of

American Radiance

(University of Nebraska press, 2018) and theforthcoming When the World Stopped Touching (YesYes Books, 2027). Thepoems in I Make Jokes When I’m Devastated are funny and odd and sad andsharp, offering lines that bend into surreal and twisted shapes, writing onparents, family, children, the scope of war and multi-generational trauma (allof which make me completely understand how she has a collection forthcomingwith YesYes Books, as her work fits perfectly with their aesthetic). “Friends,”she writes, to open the absolutely delightful “Woman Posting in ParentingForum,” “I have come to the end of my rope. / My child has decided that he isthe moon / and I cannot convince him otherwise. His entire / face a moon, not aman in the moon, but a toddler / that is the moon, and yes he does give offlight / in the darkness and yes some days he pulls the ocean / current towardhis body and yes I’ve noticed / that when I take him to poetry readings / orart museums everyone cannot help but stop what / they are doing and begin todraw pictures of him […].” This slim and sharp poetry collection is anassemblage of poems around the narrator’s mother, but is also so much more thanthat. “[…] my mother somehow knowing how to pilot,” she writes, as part of thewonderfully-propulsive and evocative “My Mother as Tom Cruise,” writing hermother’s strength through the visage of a Hollywood Blockbuster action hero, “ahelicopter my mother pulling her abusive / father out of a bathtub my motherslamming / her fist down on the table during an arm / wrestling tournament […].”This collection is an assemblage of poems around the trauma of war in Ukraine,connecting to memory and trauma comparable to other recent works such as AnnaVeprinska’s Bonememory (Calgary AB: University of Calgary Press, 2025)[see my review of such here] and Ilya Kaminsky’s Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo Press, 2004), but is alsoso much more than that. “The missiles that fell on the village / did notdirectly hit my grandmother’s / childhood home,” she writes, to close the titlepoem, “but they were close enough. / The Russian invaders claimed they did notmean / to bomb Babyn Yar, but their shells were close enough. / Mygreat-grandmother wasn’t that Jewish, / but she was close enough. When you askme for / another response to tragedy, I tend to begin with a joke. Which isn’t /exactly the shape of sorrow, but I assure you, / it is close enough.” These arehigh-wire poems, perfectly executed with an enormous amount of risk witheverything gained, and poems such as “When I Say I Am Not the Speaker of MyPoems,” “I Just Need You to Understand that / Chickens Are Basically Dinosaurs,”“The Aushcwitz Exhibit Asks Me / to Rate My Experience,” and “My Mother Insiststhat I Stop Telling / People She Was a Smuggler” really need to be read to be believed,for all of their sharp, even devastating, possibilities. As “My Mother Insiststhat I Stop Telling / People She Was a Smuggler” begins: “You see she wouldonly pay a guy to take some stuff / to a place. It could have been nothing butmostly / it was diamonds and furs, whatever she could get her / hands on. One timeit was endless yards of tent material / and what could you even do with that?”There is such an articulation of the human and emotional cost of war throughoutthese poems, referencing the war in Ukraine and the Holocaust, a backdrop toalmost every word she places on each page, one against the other. Muradyanoffers a sense of beauty and curiosity layered in surreality underneath a layerof humour, all of which covers, even collides with, an underlay of multi-generationalgrief, each and all wrapped into and around and through. These poems are smartand savage and subtle, even outlandish, as the end of the poem “Everything isSexy” writes:

Oh,I am very taken with Luisa Muradyan’s incredible second collection,

I Make Jokes When I’m Devastated

(Dallas TX: Bridwell Press, 2025). According to theauthor biography on her website (as this is the first I’ve heard of her and herwork), Muradyan is originally from Odesa, Texas, has a Ph.D. in Poetry from theUniversity of Houston, currently lives in the United States and is also theauthor of

American Radiance

(University of Nebraska press, 2018) and theforthcoming When the World Stopped Touching (YesYes Books, 2027). Thepoems in I Make Jokes When I’m Devastated are funny and odd and sad andsharp, offering lines that bend into surreal and twisted shapes, writing onparents, family, children, the scope of war and multi-generational trauma (allof which make me completely understand how she has a collection forthcomingwith YesYes Books, as her work fits perfectly with their aesthetic). “Friends,”she writes, to open the absolutely delightful “Woman Posting in ParentingForum,” “I have come to the end of my rope. / My child has decided that he isthe moon / and I cannot convince him otherwise. His entire / face a moon, not aman in the moon, but a toddler / that is the moon, and yes he does give offlight / in the darkness and yes some days he pulls the ocean / current towardhis body and yes I’ve noticed / that when I take him to poetry readings / orart museums everyone cannot help but stop what / they are doing and begin todraw pictures of him […].” This slim and sharp poetry collection is anassemblage of poems around the narrator’s mother, but is also so much more thanthat. “[…] my mother somehow knowing how to pilot,” she writes, as part of thewonderfully-propulsive and evocative “My Mother as Tom Cruise,” writing hermother’s strength through the visage of a Hollywood Blockbuster action hero, “ahelicopter my mother pulling her abusive / father out of a bathtub my motherslamming / her fist down on the table during an arm / wrestling tournament […].”This collection is an assemblage of poems around the trauma of war in Ukraine,connecting to memory and trauma comparable to other recent works such as AnnaVeprinska’s Bonememory (Calgary AB: University of Calgary Press, 2025)[see my review of such here] and Ilya Kaminsky’s Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo Press, 2004), but is alsoso much more than that. “The missiles that fell on the village / did notdirectly hit my grandmother’s / childhood home,” she writes, to close the titlepoem, “but they were close enough. / The Russian invaders claimed they did notmean / to bomb Babyn Yar, but their shells were close enough. / Mygreat-grandmother wasn’t that Jewish, / but she was close enough. When you askme for / another response to tragedy, I tend to begin with a joke. Which isn’t /exactly the shape of sorrow, but I assure you, / it is close enough.” These arehigh-wire poems, perfectly executed with an enormous amount of risk witheverything gained, and poems such as “When I Say I Am Not the Speaker of MyPoems,” “I Just Need You to Understand that / Chickens Are Basically Dinosaurs,”“The Aushcwitz Exhibit Asks Me / to Rate My Experience,” and “My Mother Insiststhat I Stop Telling / People She Was a Smuggler” really need to be read to be believed,for all of their sharp, even devastating, possibilities. As “My Mother Insiststhat I Stop Telling / People She Was a Smuggler” begins: “You see she wouldonly pay a guy to take some stuff / to a place. It could have been nothing butmostly / it was diamonds and furs, whatever she could get her / hands on. One timeit was endless yards of tent material / and what could you even do with that?”There is such an articulation of the human and emotional cost of war throughoutthese poems, referencing the war in Ukraine and the Holocaust, a backdrop toalmost every word she places on each page, one against the other. Muradyanoffers a sense of beauty and curiosity layered in surreality underneath a layerof humour, all of which covers, even collides with, an underlay of multi-generationalgrief, each and all wrapped into and around and through. These poems are smartand savage and subtle, even outlandish, as the end of the poem “Everything isSexy” writes:or maybe it’s just youtending to the garden

that I promised I wouldwater and never

do and yet here you arein your gray

gym shorts and this isthe summer

of cucumbers as big as mywant

and I’m holding an emptysalad bowl

waiting for you to comeinside.

May 12, 2025

Kyo Lee, i cut my tongue on a broken country

My review of Waterloo, Ontario-based Kyo Lee’sfull-length poetry debut,

i cut my tongue on a broken country

(VancouverBC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2025), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of Waterloo, Ontario-based Kyo Lee’sfull-length poetry debut,

i cut my tongue on a broken country

(VancouverBC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2025), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

May 11, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Adam Haiun

Adam Haiun is a writer from Tiohtià:ke/Montréal. In2021 he was a finalist for The Malahat Review’s Open Season Award for fiction.His work can be found in filling Station, Carte Blanche, and TheHeadlight Anthology.

1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

I feel I’m still midway through the change and lack the ability to fully describe it… I just recently held the book in my handsfor the first time, that was a trip. I’m so happy with it. I’m happy!

I’ve always had my fascinations. Dreamsand the feeling of dreams, architecture, sickness, masculinity, mourning. I’vebeen playing with different levels of abstraction, or obfuscation, depending onhow you want to look at it. This book is more abstract (or obfuscated) as partof its premise, or thanks to the conceit of the speaker. The things I’ve beenworking on most recently feel a bit more forthcoming. I’m also enjoyingintroducing some more humour, though I think there’s parts of this book thatare funny, to me anyhow.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I definitely intended to be a fictionwriter first. Poetry for me was a happy accident. In one of my first fictionworkshops I wrote a bad poem inside of a bad short story (one of the characterswas a poet) and some of my peers pointed out that there was some promise in thepoem, and that got me started. I realized how often I had to contrive of entirescenes in my stories just to present an image or mood that I liked, and how Icould drop that usually uninteresting scaffolding if I wrote a poem instead. I lovefiction, to be clear, I love the novel, and I’m working on one now, but poemsare always going to be my preferred medium, as a way of skipping to the goodstuff of language as it were.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

The start comes quickly for me, and thenthe trial begins. It needs to prove itself as having legs. If it doesn’t, Icannibalize whatever I can from it and use that in the next thing, ifapplicable. I can handle only about two projects at a time.

Five or so years ago I started writing allmy first drafts by hand. I have trouble permitting myself to be messy or to useplaceholders when typing things up, and I don’t have that trouble in anotebook. And so when I go about transcribing that piece, the act oftranscription becomes the first round of editing, and the document once typedup ends up looking surprisingly clean and good. Very useful practice for mepsychologically.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’m often drawn to write book-lengthconcepts, or section-length concepts, or long poems, more than shorter,disconnected pieces. I do write shorter pieces, and they’re useful to have, asan arsenal to bring to readings or to send out to mags. They can demonstraterange. But for whatever reason they’re never the ones I’m most proud of. Irespond well to the exercise of cultivating a particular voice and maintainingit or orbiting a particular subject matter and attacking it from variousangles. When you isolate a part of a conceptual project like that, I feel thatyou can sense all the weight of the work around it, if that makes sense.

5 - Are public readings part of or counterto your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I wish I had either more readingcommitments, or less. I feel like just enough time goes by between my readingsfor me to forget that I do enjoy them, and I get the jitters all over again. Iwouldn’t say they are part of my creative process necessarily, though I oftenget lovely feedback, and I really value the social component, seeing andsupporting writers I care about. I like readings, but aspects of them frustrateme. I always want to approach the readers and ask: “What does your poem looklike? What’s its shape on the page?” Maybe that demonstrates a lack of duerespect for the oral tradition… Nobody’s perfect.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’ve read my fairshare of theory, and if I were an impressive kind of writer I’d cite somethinggood here. But I have the memory of a goldfish.

I think the question I’m asking is: “Iseverybody seeing this?” I’m trying to translate the state of my mind textuallyand see if it resonates, and if it does then I can be a bit more confident inmy experience of reality.

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

My partner is an editor, and she describeswriters as existing on a spectrum between people who write because they havesomething of value to communicate, a story, a theory, a lifetime’s worth ofknowledge, and people who write because they can make anything they write aboutgood, and for me the gulf between those two ends of the spectrum is so widethat I feel loath to assign that immensely varied wedge of humanity anyparticular cultural role. On the one end you have sensible people writing underthe intended purpose of language, and on the other you have little goblins whowant to waste your time contorting this ultimate tool of communication into anobject that pleases the brain against its own better judgement. In allseriousness, writing isn’t a calling. It’s a human practice, a human behaviour.Some people decide to exacerbate that behaviour, maybe tone it a little, anddisseminate it, if they’re lucky, by way of the industry we have in place forits dissemination. The people who take that path aren’t ennobled, they haven’ttaken on a sacred mission. Maybe the role of the writer should be to writewell, and as much or as little as is conveniently possible for them, and to bea good person.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

This book was my first time working withan outside editor, and it was incredible. Ian Williams is a fantastic writerobviously, and he was the perfect fit to edit this project. We edited togetherover video calls, just talking over the poems, reading them aloud, discussingwhether the formal moves were working, whether the voice was consistent,whether the persona of the speaker was present enough. His suggestions were sonatural, so clearly aligned with the spirit of the piece, that they barely feltlike changes, and often I found myself answering him with: “Oh, of course!”

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Salt at every stage of cooking. Forwriters I think that means trying to be consistently surprising.

10 - What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m trying my very best to have one. WhenI work on fiction writing, that requires sitting down, in an uninterrupted way,with goals set and a block of time reserved. When I write poetry I find I canbe looser. My aforementioned notebook is with me at all times when I read, asso much of my note-taking involves cribbing from or responding to things I’veread, and any kind of reading too, from theory to poetry to interviews to thenews. I often transcribe my dreams in the morning.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, wheredo you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I find it’s important to turn to the rightthing for the kind of block I’m experiencing. If I’m feeling like I lackpermission, for instance, I read a scene from Gravity’s Rainbow, notbecause I love it necessarily, but to remind myself that, oh, right, there arevery many things that can be gotten away with, in form, content, and style.

But often a block is a symptom, usuallythat I haven’t been social enough, or haven’t spent enough time in naturelately, or haven’t seen a good film in a while. Or tried out a new recipe.

12 - What was your last Hallowe'encostume?

Gomez Addams. I don’t have a pinstripesuit so I wore a silk robe and I was very comfortable the whole night.

13 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I grew up in the suburbs, and so I spent alot of my childhood and adolescence being driven into and around the city ofMontreal as a passenger. Looking at the city through a car or bus window was myunspoken favourite pastime, and the feeling and moods it produced in me arefoundational to my desire to make art. I love concrete and overpasses and oldfactories. I love the character of the different neighbourhoods. I didn’tinternalize the geography of the city itself until I was a full adult, becauseanytime we drove anywhere, I was so absorbed by the act of looking at it.

14 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Guy Davenport, Cormac McCarthy. Anne Carson is absolutely undefeated. I love Tolstoy. Tolkien was my first.

15 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

Either learn to sail or learn to properlyride a horse. I’ve been in boats and I’ve been on horseback, but in bothcircumstances I wasn’t really in control… These feel like skills that will makeme whole.

16 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

As a kid I loved to draw and paint andwasn’t bad at it either. I could certainly imagine a version of myself whobecame some kind of visual artist instead. Maybe that’s a copout. Lately I’vebeen thinking of doing a course in tiling, maybe mosaic. I want my somedaydream kitchen to have some kind of unique mosaic backsplash that I’ll have mademyself. My point is I’d likely have done work involving my hands in some way.

17 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

A lot of people told me to, and I tried toignore them, and was sad for that whole time, and when I decided to listen Ibecame happier. Really, haha. I tried to be an architect, then an engineer,neither went very far. I struggled to conceive of myself as somebody who couldwrite something worth reading, and it was people who loved me who showed methat I did have that in me, that I had a deep curiosity, an observational eye,a passion and talent for language, et cetera. These are things I’ve onlyrecently felt able to say about myself.

18 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

I read and loved Tove Jansson’s Fair Play,which is a book of short, slice-of-life vignettes featuring the same pair ofcharacters. I feel like it taught me a lot about how to make the most of theepisodic, how the characterful microconflicts and sweet microresolutionsbetween people who love one another can be interesting enough to carry a book.

I recently watched Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession(1981) as part of the endless journey my partner and I are on to find afilm that will legitimately haunt us, in the way you’re haunted by things whenyou’re a child. This one got very close to that for me. The blend of therealism or groundedness in the domestic scenes with the horror or absurd, thefrightening and traumatic injected with just enough humour, the performances,my God, Isabelle Adjani, the West Berlin setting. An instant favourite for me.Two very oppositional pieces of art, both about relationships.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a novel about a youngishperson leaving the city to live with his aunt and uncle in rural Quebec. Theconceit is that this character is endlessly forgetful (you can now probablyguess who I pulled this from) and impossibly obliging, and his aunt and uncleare very strange and very demanding. And there will be some absurd and surrealstuff happening, which of course the character will have to be totally finewith.

I’ve also recently started a new poetryproject, where I’ll be writing a kind of oblique response to each of Montaigne’sessays. Whether it’ll be a chapbook or a section of a book or a whole book isup in the air at this point. This idea came out of an exercise in SarahBurgoyne’s most recent poetry studio, which I was very fortunate to participatein. So many of the best things I’ve written have come out of great prompts fromother people.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 10, 2025

Apt. 9 Press : Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi + Jo Ianni,

laid down to theirbuilding blocks

word and word and thenbrick-light

the attack and decay

of every action-sentence

made its own assemblyline

like take the darkroomfor example

and build an apiary

like take the gun chamberfor example

and build an apiary

like take the steamengine for example

and build an apiary

like take the black pagefor example

and build an apiary(Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi)

Itis always an exciting mail day when the latest titles from Cameron Anstee’s Apt. 9 Press land [see my notes on his prior titles, SOME SILENCE: Notes onSmall Press and APT. 9 PRESS: 2009-2024: A Checklist, here], withthe two latest being Toronto poet Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi’s Gavel sound. Gravel sound. (February 2025),produced in a numbered first edition of eighty copies, and Toronto poet JoIanni’s FAT LUCK AND FUZZY SONG (April 2025), a title produced in anumbered first edition of one hundred copies. It is interesting in how bothtitles, hand-sewn and gracefully-produced, and with French flaps, hold extendedpoems that each offer a different sense of ongoingness, of chapbook-lengthstructure, one short poem and section and fragment at a time.

Itis always an exciting mail day when the latest titles from Cameron Anstee’s Apt. 9 Press land [see my notes on his prior titles, SOME SILENCE: Notes onSmall Press and APT. 9 PRESS: 2009-2024: A Checklist, here], withthe two latest being Toronto poet Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi’s Gavel sound. Gravel sound. (February 2025),produced in a numbered first edition of eighty copies, and Toronto poet JoIanni’s FAT LUCK AND FUZZY SONG (April 2025), a title produced in anumbered first edition of one hundred copies. It is interesting in how bothtitles, hand-sewn and gracefully-produced, and with French flaps, hold extendedpoems that each offer a different sense of ongoingness, of chapbook-lengthstructure, one short poem and section and fragment at a time.Thereis such lovely detail to the moments, the fragments, of Khashayar’s Gavel sound.Gravel sound., offering poems and condensed fragments and short sketches,holding to the smallest possible utterance amid what might be an extended,single piece. “a poem / is just / what light / thinks about,” Khashayar writes,just near the end. There isn’t a wasted word throughout this entire sequence,taking the entirety of a single poem and dismantling it across such a length ofthought. “I’m struggling to kich the poem / out of my neighborhood,” offers anearlier poem-fragment, “sea urchins / like riddles / or ruin // flicked by toetip / into lake Ontario [.]”

Thereis something really interesting in the way that Khashayar’s work has progressedthrough and since the publication of their first two collections—Me, You,Then Snow (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]and the dos-a-dos WJD conjoined with The OceanDweller, by SaeedTavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Mohammadi (Gordon Hill Press, 2022)[see my review of such here]—extending into projects of smaller moments thataccumulate and stretch in really fascinating and quiet ways, such as theirthird full-length collection, Daffod*ls (Pamenar Press, 2023) [see my review of such here], or through the collaborative G (with Klara du Plessis; Palimpsest Press, 2023). There’s already a further full-length due this fall with Wolsak and Wynn, which I am very much looking forward to.

under

neath the

patient

spider

golden

in its thereness

I laid

beside you

weepy

a landscape for ants

for grass to tickle

pushing up dandelion

clocks and

raising up dirt

JoIanni is one of only a handful of repeat authors through Apt. 9 Press, with inside inside inside appearing with the press in 2022 [see my review of such here]. Akin to Mohammadi, Ianni’s FAT LUCK AND FUZZY SONG (the openingpart of the title I keep mis-reading as something much ruder, admittedly) is abeautifully-crafted long elegant thread of extended sequence, constructed outof condensed curves, bends and moments, lyric stretches and the weight of theoccasional underlined passage or word. The underlined passages are curious, andthere were moments I wondered if these were to highlight for the sake of apoem-title for these small, self-contained fragments, but the fact that otherpoems hold more traditionally-placed titles while still offering underlinedpassages contradicts that, making me wonder if these are simply points in eachpoem where the eye is to be drawn, slightly, and possibly held. The poems arequiet, thoughtful, odd, with gestures and utterances in the direction of Robert Duncan, here and there, which is curious, the poem “Itty bitty ditty,”“for Robert Duncan + his cat,” that includes “Where else will I go but heredeeper still wish my knees bent and belly full of soup / There’s no more I cando for the moon than glory [.]” Oh, how I delight in the quiet, extendedstretches of Jo Ianni’s lyric structures; more people should be reading thework of Jo Ianni.