Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 19

April 19, 2025

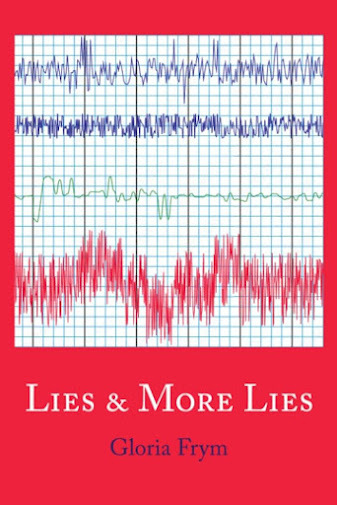

Gloria Frym, Lies & More Lies

Reality

We’re not at thebeginning of the beginning. Or at the middle of the beginning. We’re not at theend of the beginning. We’re at the beginning of the middle. It will take sometime to reach the middle of the middle. Speaking truth to constituents, we don’tknow when we’ll be at the end of the middle. It will take more time to get tothe beginning of the end, perhaps forever. We may not be around for it, I mean,when we reach the middle and the end of the end. So finally, it’s a good thing,we believe, to attach people to the new reality.

Self-describedas a “wildly honest and forceful collection of prose poems, satires, and shortfictions,” Berkeley, California-based poet, fiction writer and essayist Gloria Frym’slatest is

Lies & More Lies

(Kenmore NY: BlazeVOX [books], 2025), anassemblage of short pieces that form a considerable collection of sharp fictions.Who was it that offered of artists, that we fight laziness and lies in oursearch for the truth? I hadn’t heard of Frym or her work prior to thiscollection, but she’s the author of an armload of titles of poetry and prose,including Back to Forth (The Figures, 1982), By Ear (Sun and MoonPress, 1991),

How I Learned

(Coffee House Press, 1992),

Distance No Object

(City Lights Books, 1999),

The True Patriot

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2015)and

How Proust Ruined My Life & Other Essays

(BlazeVOX, 2020), aswell as a book of interviews with women artists, Second Stories (ChronicleBooks, 1979).

Self-describedas a “wildly honest and forceful collection of prose poems, satires, and shortfictions,” Berkeley, California-based poet, fiction writer and essayist Gloria Frym’slatest is

Lies & More Lies

(Kenmore NY: BlazeVOX [books], 2025), anassemblage of short pieces that form a considerable collection of sharp fictions.Who was it that offered of artists, that we fight laziness and lies in oursearch for the truth? I hadn’t heard of Frym or her work prior to thiscollection, but she’s the author of an armload of titles of poetry and prose,including Back to Forth (The Figures, 1982), By Ear (Sun and MoonPress, 1991),

How I Learned

(Coffee House Press, 1992),

Distance No Object

(City Lights Books, 1999),

The True Patriot

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2015)and

How Proust Ruined My Life & Other Essays

(BlazeVOX, 2020), aswell as a book of interviews with women artists, Second Stories (ChronicleBooks, 1979). Acrossthe thirty-five pieces that make up Lies & More Lies, Frym pushes atthe boundaries of prose in intriguing ways, offering narratives that stretchand pull at the elastic of the sentence. “Because I made one,” she writes, toopen the story “Hunger,” “I wanted to make another. Then there were two, and I wanteda third. My greed grew daily because there were none for such a long a time. I reallydesired dozens, not content with what was. I knew I was playing with a sharpinstrument by wanting a bunch, but Mother always said my eyes were bigger thanmy stomach.” Frym’s pieces seem very comfortable in that between-space neithershort story nor prose poem nor essay but blending all of the above, writingstraightforward sentences that bend at the waist, and accumulate into somethingfar beyond. “There’s no need for lips anymore. There’s no need for lipstick,”she writes, to open “Need During the Pandemic,” “wear the same jeans for work,no place for Socratic method on Zoom, no new shoes, no need except for this tobe over and out. A day is a one-way street.”

April 18, 2025

Adam Haiun, I Am Looking for You in the No-Place Grid

Thefull-length debut by Montreal poet Adam Haiun is the intriguing I Am Looking for You in the No-Place Grid (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2025), a bookof lines, grids and shapes set across each other in lengths. I might imaginethat if the late Canadian poet and dramatist Wilfred Watson (1911-1998), once famousfor his own grid poems (but more enduringly well-known as being the husband ofwriter Sheila Watson), had been able to shake Modernism, he might have emergedas Adam Haiun. I Am Looking for You in the No-Place Grid offers a longpoem sketchbook of narrative threads set in overlapping text, overlappinggrids, moving in multiple directions simultaneously, and deliciously difficultto replicate in the form of a review (although I shall make an attempt). “Andwhere am I to / be found in this equation.” he writes, early on in the assemblageof untitled pieces, set in the table of contents as a listing of first linesdemarking self-contained pieces, twenty-one in all. “The head the hindquartersintact / the heart presumably obliterated / if any logic governs the placement/ of organs. And you only notice / today how there are little grey / apartmentsabove that grocery / store. The miniaturizing impulse. / In terms of the heart.In relation / to the glands. All the pungency / of the ripe orange in the stairwell/ and the recognition of the smell / as belonging to her very pits. The /stretch of land that constitutes a / lesson from out of the past. The / engorgement.”

Thefull-length debut by Montreal poet Adam Haiun is the intriguing I Am Looking for You in the No-Place Grid (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2025), a bookof lines, grids and shapes set across each other in lengths. I might imaginethat if the late Canadian poet and dramatist Wilfred Watson (1911-1998), once famousfor his own grid poems (but more enduringly well-known as being the husband ofwriter Sheila Watson), had been able to shake Modernism, he might have emergedas Adam Haiun. I Am Looking for You in the No-Place Grid offers a longpoem sketchbook of narrative threads set in overlapping text, overlappinggrids, moving in multiple directions simultaneously, and deliciously difficultto replicate in the form of a review (although I shall make an attempt). “Andwhere am I to / be found in this equation.” he writes, early on in the assemblageof untitled pieces, set in the table of contents as a listing of first linesdemarking self-contained pieces, twenty-one in all. “The head the hindquartersintact / the heart presumably obliterated / if any logic governs the placement/ of organs. And you only notice / today how there are little grey / apartmentsabove that grocery / store. The miniaturizing impulse. / In terms of the heart.In relation / to the glands. All the pungency / of the ripe orange in the stairwell/ and the recognition of the smell / as belonging to her very pits. The /stretch of land that constitutes a / lesson from out of the past. The / engorgement.”Theauthor’s note at the end of the collection—“Although I wrote this book in thevoice of a digital speaker, I employed no generative software in itscomposition.—suggests a kind of polyvocality of not just overlapping text butoverlapping sound, furthering structural echoes of some of the work of Montreal poet, translator and performer Oana Avasilichioaei’s own explorations aroundsound, language, meaning and performance, most recently through her seventhfull-length collection, Chambersonic (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2024)[see my review of such here] (although there are numerous over the years thathave played with an overlapping of text, certainly, from Chris Turnbull tobpNichol to jwcurry, among others). Haiun’s overlapping sentences and phrases playthe glitch and stagger, overlay and staccato of fragments across a far broadertapestry of construction and destruction, how things are built and how theyfall apart. Every sentence a further step across an endless stretch ofnarrative across the length and breath of the long poem, as he writes, mid-waythrough the collection: “The head the hindquarters intact / the heartpresumably obliterated / if any logic governs the placement / of organs. And youonly notice / today how there are little grey / apartments above that grocery /store. The miniaturizing impulse. / In terms of the heart. In relation / to theglands. All the pungency / of the ripe orange in the stairwell / and the recognitionof the smell / as belonging to her very pits.”

April 17, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Louise Akers

Louise Akers is a poet living inBrooklyn, NY. She is a PhD student in English at NYU and is theco-organizer of the small press and working group, the Organism for Poetic Research. Akers is the author of two books of poetry, Alien Year(Oversound, 2020) and Elizabeth/The story of Drone (Propeller Books,2022).

1 - Howdid your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook came out in 2021 with theexceptional people at Oversound, but the process of writing it had begunprobably in 2016. It was a sharply condensed version of a much longer, moregangly and amorphous manuscript that I had taken a pretty sculptural approachto cutting down. Working with Oversound was a wonderful and generousexperience, and I am very proud of that little chap! My second book, Elizabeth/the story of Drone (PropellerBooks, 2022) is a very different beast. I wrote it mostly in the summer andfall of 2019 while I was working part time at a museum, and it is much moreproject-based, much less distilled. For instance, it has characters and scenes,which was a stretch for me! My editors at Propeller were also incrediblythoughtful and supportive, so it retains, I think, a kind of frantic, creepyspontaneity that’s much less condensed. Now my work feels much more personal;both of those books I think were self-consciously non-confessional, almostanti-autobiographical. I lost both of my parents in the last two years, whichreally put my writing on hold. It also kind of disallowed me from avoidingmyself in my work anymore. I think going through that really changed how Iapproach language and self-disclosure in language. Grief makes your braindifferent.

2 - Howdid you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve always been really attracted to language asa medium you can manipulate or organize into something that can exceed orsubvert or complicate its so-called “content.” I’m fascinated by how far awaylanguage can get from its meaning, from anything resembling “information,” butstill do or activate so much else. That’s really what got me into poetry.Admittedly, I tried to make Elizabeth intoa novel, but fell quite short of the mark, I think. I struggle with maintainingthat level of fidelity to an object, maybe.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My writing comes quickly or not at all really,haha. I write in pretty huge deluges and then kind of try to take a scalpel toit. In some cases, the first shot is the final one, but in others only a lineor two will survive the purge so to speak, so it really depends. I take a lotof notes. I go through periods where I feel like I am just accumulating andaccumulating language in a kind of stockpile, and then suddenly, withoutwarning really, I am ready to let her rip.

4 -Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I think I am always aware of a future life of apoem in a book, but I don’t necessarily proceed with that intention. I willhave one document full of writing or poems that I can fully conceptualize manydifferent books around. I think I am more successful when I am moreconceptually agnostic and just kind of let my writing develop constellations ofmeaning over time.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings–because they are fun andsocial and ephemeral experiences, but also it is a hell of a way to edit apoem. When I know I am reading something out loud in front of strangers, I willbe totally ruthless in a way that only vanity can inspire. Also sometimes whileI’m reading it, and really hearing and feeling its living reception I willchange little things to allow for clarity or rhythm or some other immediate andinterpersonal effect.

6 - Doyou have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questionsare you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

My questions or concerns have emerged really outof my professional/institutional backgrounds, which include the art world andacademia. Elizabeth was reallyconcerned with the media-technological intersections between the commercial artworld and the USAmerican war machine; drones became a kind of figure for thatacute anxiety, but also defanged self-disgust in a sense of complicity. Now, Iam thinking more about grief, on an individual level but also on a sociallevel. Covid happened and f*cked us all up in ways that we are still only justbeginning to recognize, let alone understand. The ongoing genocide in Palestinehas revealed many things about the West and the US, including just how tightthe chokehold that the executive branch of government has on the academic andcultural institutions that we, as writers and artists and scholars, have triedvery hard to be a part of, actually is. Grief feels really close, and closerstill the more it is held at bay. There is so much more to say about this, butI’ll leave it there for now.

7 – Whatdo you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oh, it’s hard not to just quote Walter Benjaminon this one. I think critique is important; I think it is important to registerthe fact that throwing language at a problem (“problem” standing in here verybroadly and clumsily for any of the myriad social-political-environmental-economiccataclysms we are enmeshed in currently), policing the language around aproblem, or even diagnosing a problem discursively are all deeply incompleteprojects, while also realizing that that is not an excuse or a reason not to dothose things. Very clunky sentence, but hopefully you get the drift.

8 - Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

I like it. I find it pretty easy to takecriticism, and also I kind of appreciate the moments where I instinctively digmy heels in. I think it’s revealing about what is important to me in ways Imight not register otherwise. I do have to say I have had really exclusivelywonderful experiences with editors, so maybe I am just lucky!

9 - Whatis the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Not every single thing you do has to be done inthe most efficient way. It’s ok to get somewhere via a circuitous, delayed, orotherwise imperfect route.

10 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? Howdoes a typical day (for you) begin?

I am in graduate school getting a PhD somaintaining a routine is really a cherished pipe dream of mine. I am workingwith my therapist on it! My only real routine comes from my dog, Moose, whoneeds four walks a day. Everything else can fall apart, but she always gets meout of bed for that first walk!!

11 -When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

When I am really struggling, the only way for meto move at all is to read. I often will just grab a comically heavy hitter likeRimbaud or Ashbury or Dickinson off the shelf and open to a random page andstart reading until I feel like I have a brain again. It doesn’t always work.

12 -What fragrance reminds you of home?

The ocean and those little lavender scentedpillows that deter moths.

13 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My sister is a visual artist and she and I arevery close, so visual art has always been really important to me and mypractice. I worked in galleries for a few years, and studied art history inundergrad. I think a lot about Impressionist painters like John Singer Sargentand Romantic painters like JMW Turner, because their work seems to suggest alot about what I think poetry can do: say a lot with a little, which is to say,perform a deceptively spontaneous gesture, and perform it with excruciating precisiondespite its purported lack of realism. I also listen to a lot of music, buthave famously uncool taste haha.

14 -What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

A brief and non-exhaustive list of writers whoare very important to me presented in no particular order: Anne Carson, William Blake, Fred Moten, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sean Bonney, Samuel Delany,Wallace Stevens, Denise Ferreira da Silva, Diane di Prima, Alice Notley, Louis Zukofsky, Lucretius, John Donne, Dionne Brand, William Wordsworth (I’m aRomanticist, technically, so I can’t help it), Lyn Hejinian, Walter Benjamin…the list goes on and on!

15 -What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to write a play. That form ofcollaboration and interpretation and spontaneity attracts me immensely, butalso intimidates me!

16 - Ifyou could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

I think if I had not been a writer, I would stillbe in the art world. I think if I could start over and have a different life, Iwould be a professional athlete lol.

17 -What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Growing up, my older sister was alwaysdemonstrably exceptionally talented as a visual artist; I was not. I think myparents really didn’t want us to be in direct competition with each other, so Iwas kind of pushed into sports because I was better at that. I had this kind ofcomplex that because she was so good at creative arts, that wasn’t for me. Ihad to be good at something else entirely. It wasn’t until after college reallythat I started writing creatively, and I think it was mostly because my sisterwasn’t a poet, so I thought I could do that. I got into poetry because itseemed the most precise way to get at wiggly, uncertain feelings and thoughtsand desires I didn’t have language for otherwise.

18 -What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I very rarely read novels, which I shouldn’tadmit, but I read Portrait of a Ladyby Henry James last month and it was an absolute delight. I also really lovedRobert Eggers’ new take on Nosferatu, withthe caveat that film is not my strong suit.

19 -What are you currently working on?

Right now I am working on a book about grief.It’s also about certainty. It hasn’t really happened on purpose, but whenever Istart writing it’s like this kind of elliptical return. It’s also heavilyinfluenced by my very conflicted but somewhat obsessive reading of ImmanuelKant’s Critique of Pure Reason. I’mvery curious about ways in which philosophers, misguidedly and dogmatically,try to make their readers feel betterabout how impossible it is to know anything about anything or anyone with anycertainty. Philosophy is supposed to be something like therapy, you know? Butit fails, and often leads us down worse rabbit holes with more distressingquestions, or accusations. I miss my parents and I feel like time stopped whenI lost them. But it didn’t for anyone else. I don’t know what to do with that,so I’m writing about it.

April 16, 2025

today is Aoife's ninth birthday,

Happy birthday, Aoife!

Happy birthday, Aoife!Nine. god sakes.

She had a birthday party this past Sunday, during which she and seven of her friends, as well as sister Rose and myself, could not figure out how to escape the escape room (I absolutely hate escape rooms, but that was her request). But the kids had enough fun, and no-one cried or fought or anything so it probably still worked. Once the time ran out we were released for pizza and cake. Everybody loves cake.

April 15, 2025

Spotlight series #108 : Mahaila Smith

The one hundred and eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa writer and editor Mahaila Smith

.

The one hundred and eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa writer and editor Mahaila Smith

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau, Indiana poet Nate Logan, Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn, North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson, award-winning poet Ellen Chang-Richardson, Montreal-based poet, professor and scholar of feminist poetics, Jessi MacEachern, Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell, San Francisco poet Micah Ballard and Montreal poet Misha Solomon.

The whole series can be found online here .

April 14, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lesley Wheeler

Lesley Wheeler, Poetry Editor of Shenandoah, is the author ofMycocosmic, runner-up for the Dorset Prize and her sixth poetry collection.Her other books include the hybrid memoir Poetry’s Possible Worlds andthe novel Unbecoming; previous poetry books include The State She’s In and Heterotopia, winner of the Barrow Street Press Poetry Prize.Wheeler’s work has received support from the Fulbright Foundation, the NationalEndowment for the Humanities, Bread Loaf Environmental Writers Workshop, andthe Sewanee Writers Workshop. Her poems and essays have appeared in Poetry,Poets & Writers, Kenyon Review Online, Ecotone, Guernica,Massachusetts Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Virginia and teachesat W&L University.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

This is weird to saybecause poetry books earn virtually nothing, but the biggest way publicationchanged my life was economic. Publication is artistically validating and joyous,and those first books in each genre transformed my sense of identity, but inthe academic reward system, books enable tenure and promotion.

Mydebut full-length poetry collection, Heathen, was, like many firstbooks, a best-of album honed at live readings. Mycocosmic is a concept album aboutthe underworlds that support above-ground transformation.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry suits me becauseI love sound patterns and my brain prefers associative to logical moves. Iwrote fiction constantly as a child, though, and I’ve circled back to bring thatgenre into my writing life again.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Initial drafts tend to flowrapidly: the bad first draft of my novel Unbecoming, for example, emerged in a seven-week writing binge. It’s veryrare, though, for me to draft a poem or anything else that doesn’t then requiremassive revision. I tend to put a draft away for months, pull it out for a radicaloverhaul, and repeat the process a few times. It takes me a long time to seethe work from a critical distance.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I’ve worked both ways,but most commonly: I write by impulse until I accumulate a pile of poems. ThenI sift through them, thinking about throughlines. Finally, I start writing andrevising toward that throughline, and the book comes together. “Underpoem [FireFungus]” in Mycocosmic, a verse essay that unites the book by threadingacross the bottom of every page, was probably the last poem I wrote for thecollection.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I always feel lucky to givea reading to a live audience—to connect with people through poetry in real time.I enjoy conversations about poetry even more, whether in interviews orclassrooms. Like a lot of professors, though, I’m an introvert-extrovert: it’sfun to ham it up, but then I have to pay myself back with solitude.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I tell students when Iteach speculative fiction that its operative questions are “what’s real, whatmatters.” That’s true for poetry as well, whether it arises from a documentaryimpulse, relies on autobiography, imitates prayer, or springs from some otherfield. For the past ten years I’ve also been probing the question “who am Inow?” Midlife transforms a person in many ways, but it’s electrifying to readabout microbiota, too. If 80% of the DNA in my body is not human, is it in anyway meaningful to use first-person singular pronouns? Obviously I’m doing soright now, but I’m interrogating the habit.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

It’s incredibly various,thank god. I’m so glad there are activist poets, linguistic experimenters,spiritual poets, entertainers, and more.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

To engage deeply withsomeone else’s work in progress is an act of incredible generosity. I find thatpush-and-pull rewarding. Yes, occasionally I’ve thought an editor got somethingwrong or, ouch, could have managed their tone a bit better, but in poetry, forme, that’s never, never seemed motivated by ego. Literary editing is a labor oflove.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I always give adifferent answer to this question, but what’s on my mind today is somethingAsali Solomon tells her fiction students: the first obligation of any writer isto be interesting.

10 - How easy has itbeen for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction to critical prose)?What do you see as the appeal?

I never stopped writingcritical prose or had trouble toggling between criticism and poetry. Writing literaryprose, though, is not, as I once foolishly thought, a natural meeting pointbetween the two. Managing verb tenses alone—wow! As in poetry, the writer ofprose narrative is always juggling the question of what to explain and what toelide, but the math is fundamentally different.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I wake up slowly, drinka pot of tea, do puzzles. When I’m alert, I reluctantly drag myself to thedesk, but I’m happy once I get going, even if I’m mainly prepping for class. Actualwriting and revision happen only sporadically during the academic terms butdaily during summers and sabbaticals—I’m pretty disciplined then.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I read or take a walk,trying not to worry about it, because the writing always comes back. If movingmy body or immersion in someone else’s book doesn’t work, I just switch gears.It’s good to have multiple projects going so there’s always a productive way toprocrastinate.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Bus exhaust in the rainreminds me of my mother, which isn’t very flattering, but when I was six wevisited her home in Liverpool for the first time. Everything amazed me, thatfirst time on a plane, even the smelly rank of buses that greeted us at theairport.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Walking around a museumoften jolts me into poetry. Mycocosmic came largely from scientificreading about mycelium and biochemical transformations. TheState She’s In drawsat least as much from history and politics. Poetry’sPossible Worldswas inspired by narrative theory and cognitive science almost as much astwenty-first-century poetry. Sources are always myriad—the whole world canexcite the writing impulse, if you’re paying attention—but some projects leanon one discipline more than another.

15 - What other writersor writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of yourwork?

Emily Dickinson, H.D.,Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes are poets I steer through the world by. Iread fiction daily, and when the news is this terrible, I lean toward mysteriesand fantasy. This year there’s been a lot of Martha Wells, T. Kingfisher, andJohn Dickson Carr.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

I aspire to write abook-length poem, but everything keeps splintering on me. I came closest in aterza rima novella called “The Receptionist” in TheReceptionist and Other Tales. That was crazy fun to write, but could I sustainthe energy in a less narrative mode? We shall see!

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Making some kind of artwould always have been an avocation. Teaching undergraduates is a good fit forme as a day job, to the point that I wonder if any other paying employmentcould have satisfied me as much. Honestly, I have no idea.

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I loved painting anddrawing when I was young, but AP Physics clashed with Art in my high schoolschedule and my father insisted on the former. I envy singers, but I can’tcarry a tune.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

I have trouble with theword “great.” It’s not that I don’t make judgments constantly, I’m veryopinionated, but it suggests stable hierarchies of value I don’t believe in.Context matters so much: great for what, for whom, where, when? I still feelawe when I reread “The Book of Ephraim,” Life on Mars, Montage of a Dream Deferred, or just about anything by Ursula K. Le Guin, but last year Ireread Anne Carson’s Autobiography ofRed, which has always inspired thesame feeling, and it wobbled for reasons I can’t articulate yet. Was I just ina bad space that week? I don’t think A Complete Unknown was a perfectmovie by a long shot, but it was utterly absorbing and great to talk aboutlater.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I’vebeen writing poems that in various ways invoke the spiral as subject matter orformal principle. I also have a novel ms, Grievous,under consideration, and I’mdrafting a nonfiction collection with the working title Community with the Dead: Reading ModernismStrangely.

April 13, 2025

Zane Koss, Country Music

tell the cougar story

so jerry and tom go out

this one time to checkjerry’s traps he’s got a line out

for lynx and you have tocheck these quite regularly

so the poor thing isn’tstuck there so long that it starves

to death or chews its legoff to get out it’s just

a regular foot trap stakedto the ground

and they get there towhere it’s supposed to be

and it’s gone but there’ssome tracks heading out

over the snow, bigtracks, not a lynx and they follow the tracks

and there it’s this hugecougar the trap stuck on its paw

dragging the chair andstake and jerry’s only got his 22

because he’d thought itwould just be the lynx

Guelph, Ontario-based poet and translator Zane Koss’ second full-length collection,following

Harbour Grids

(Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2022) [see my review of such here] is

Country Music

(Invisible Publishing, 2025), abook-length poem of stories, ghosts and the country music of rural BritishColumbia upbringing. It is a very different tone and approach from, say, themusic of Dennis Cooley’s Country Music: New Poems (Kalamalka Press, 2004)or Robert Kroetsch’s “Country and Western” section of his

Completed Field Notes

(University of Alberta Press, 2002). As the back cover offers, Koss’music emerges from stories told around campfires or the kitchen table, held “againstthe backdrop of rural British Columbia,” offering working-class tales of “humourand violence of life in the mountains.” Koss weaves these stories through andaround the shape of an understanding of his own origins, and how he got towhere he is now. As he writes, early in the collection: “where have our fathers/ gone i have still lived more years / of my life // on a dirt road than a /paved one, / i tell people that, and // though true, it doesn’t / feel that way; mike, /where have we gone [.]” He opens the book, the poem, with a sequence of storytellingnarratives to establish his foundation of a good story, plainly told;conversational, sections of which feel comparable to The Canterbury Tales,but all told by the same unnamed narrator. The poems, the extended long poem,of Country Music, is structured in accumulating sections, offering shortnarrative bursts of storytelling lyric, notational across the pause and parry acrosseach storyteller’s particular diction.

Guelph, Ontario-based poet and translator Zane Koss’ second full-length collection,following

Harbour Grids

(Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2022) [see my review of such here] is

Country Music

(Invisible Publishing, 2025), abook-length poem of stories, ghosts and the country music of rural BritishColumbia upbringing. It is a very different tone and approach from, say, themusic of Dennis Cooley’s Country Music: New Poems (Kalamalka Press, 2004)or Robert Kroetsch’s “Country and Western” section of his

Completed Field Notes

(University of Alberta Press, 2002). As the back cover offers, Koss’music emerges from stories told around campfires or the kitchen table, held “againstthe backdrop of rural British Columbia,” offering working-class tales of “humourand violence of life in the mountains.” Koss weaves these stories through andaround the shape of an understanding of his own origins, and how he got towhere he is now. As he writes, early in the collection: “where have our fathers/ gone i have still lived more years / of my life // on a dirt road than a /paved one, / i tell people that, and // though true, it doesn’t / feel that way; mike, /where have we gone [.]” He opens the book, the poem, with a sequence of storytellingnarratives to establish his foundation of a good story, plainly told;conversational, sections of which feel comparable to The Canterbury Tales,but all told by the same unnamed narrator. The poems, the extended long poem,of Country Music, is structured in accumulating sections, offering shortnarrative bursts of storytelling lyric, notational across the pause and parry acrosseach storyteller’s particular diction. seen that picture of you

with the gun

with the twelve-gauge pump-action

shotgun

and the dead birds,pixelated

while you mourn yourgrand

father; i bet you arewondering;

but me,

i never shot anythingexcept

popcans and papertargets,

but i know it, clubbed

fish to eat; gutted

them, myself

one time my dad brought

home a tiny rabbit

in a cardboard box that

his skidder had disturbed

Thereis a way that Koss writes these stories as part of his own DNA, but as much deliberatelyleft behind, distancing himself from the roughness, the low-level violence; of knowingone is from a particular space but no longer of that space, no matter how foundationalsome of those experiences, that thinking. “when they tell these stories now //i fill in the lost details // as they try to tell them // wanting it exactly //as i remember it // every rhythm // every detail [.]” Or, this particularmoment, as one’s own learned impulses make unexpected appearances:

these days hand-fees the cat scraps fromthe table;

but sometimes, the urgeovercomes me, to lay my hot

coffee spoon against thethinnest skin on the back of

kate’s hand; it comes updeep from below, faster than i

know how to fight it;when i tell her you used to do that

to me at the breakfasttable, every morning, she can’t imagine

you thus.

Thenext page, the next line, writing: “truthfully, i can no longer either [.]” Thisis a thoughtful and powerful collection, as Koss articulates a roughness, and aparticular kind of low-level toxic masculinity taught that he still works to removefrom himself. Through such, Koss’ Country Music is comparable to DaleMartin Smith’s Flying Red Horse (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2021) [see my review of such here], in which Smith speaks of fathers and sons, and whatpasses through and what he works to prevent passing along. Koss, in his ownway, works to think across similar spaces and distances, attempting toarticulate even how to utilize the page as that best thinking space, to find bothcomprehension and comfort. “how to make the page the space,” he writes, “wherethat happens /// alone,” he writes. “the page the context in whichimprovisation could //driven by the difference only // only possible in otherness // to make the pagea space of // confronting my own otherness to myself // as a means ofimprovisation // cannot quite [.]”

Aswell, there’s a particular kind of pacing and visual rhythm displayed in Koss’long poem that is reminiscent of the late Prince George poet Barry McKinnon’s classicI wanted to say something (Caledonia Writing Series, 1976; Red Deer CollegePress, 1990); whereas McKinnon’s wrote the stories of prairie immigration acrosshis family history, focusing on parents and grandparents, Koss writes a moreimmediate setting of attempting to articulate and understand himself through familystories, including the telling and retelling of many tales he was directlyaround for, leading up to the present moment. “the beer bottles / mark time,”he writes, “gathered around, telling new / ones [.]” Koss writes not purely throughthe lens of what these stories tell but in the telling, of the attempting toclarify what it is that helped make him, and those elements he chooses to hold,and others he attempts to leave behind, all while wishing to remember the wholeof it, as best as he can. And, as Barry McKinnon opened sections of his prairielong poem with “I wanted to say something,” so too, Koss, composing his structuralecho across the interior of his own particular British Columbia upbringing:

I wanted to write a poem

that would somehow

place me

late night

kitchen table

stories

a campfire

All my sense

depends upon

that

April 12, 2025

Susan Landers, What To Carry Into the Future

It’s common in dystopiasfor people to go underground to survive after all possibilities on the surfacehave been exhausted. To go underground is to separate oneself from the mostbasic indicators of direction and time. Without stars or the sun, any naturalsense of direction or time is lost.

From their verybeginning, the trains offered New Yorkers a new way to live. (“My QuotidianIcon”)

I’mfascinated by how Brooklyn poet Susan Landers approaches poetry collections as culturaland historical mapping projects, from her Franklinstein (Roof Books,2016) [see my review of such here], a collection subtitled “Or, the making of amodern neighborhood” and described as a “hybrid genre collection of poetry andprose [that] tells the story of one Philadelphia neighborhood, Germantown,” toher latest, What To Carry Into the Future (New York NY: Roof Books, 2025).As the press release to this new collection offers, What To Carry Into theFuture is “a poetic exploration that cultivates an anarchic desire to ridethe entire [New York subway] system, not to commute, or to travel directly frompoint A to point B, but to approach the subway map as an artist and apassenger.”

What To Carry Into the Future usestransportation and location as a metaphor and a conduit to explore beleaguered socialrelationships and standards that are challenged by political and naturalforces. When we look for a city’s infrastructure, where do we find it, what dowe see, and what does it tell us about how we’re living?

Constructedthrough three extended poem-sections—“My Quotidian Icon,” “Sidewalk Naturalist”(recently produced as a chapbook through above/ground press) and “Water Finds aWay”—each section also includes a date and geographic stamp at the offset: “NewYork City, 2017-2018,” “Brooklyn, 2022” and “New York City, 2023-2024.” “I’m drawinglines / to help me see,” she writes, as part of the opening poem-section, “how Ilive in such a city.” If Franklinstein wrote out Landers’ roots, WhatTo Carry Into the Future writes of where she has chosen to land, weaving throughthe spaces and traces of geography, history, currency, chaos and gesture. “Thismay be / a love letter.” Landers writes, “This may be my vows.” A few linesfurther: “You always win, / New York. / You always get / whatever you want. /But I can still lay / tracks inside you, / reinscribe in lines / the old names/ we have for each other— / Atlantic, Pacific— / how the maiden names stick, /familiar as an ocean, / along the elevated track.”

Constructedthrough three extended poem-sections—“My Quotidian Icon,” “Sidewalk Naturalist”(recently produced as a chapbook through above/ground press) and “Water Finds aWay”—each section also includes a date and geographic stamp at the offset: “NewYork City, 2017-2018,” “Brooklyn, 2022” and “New York City, 2023-2024.” “I’m drawinglines / to help me see,” she writes, as part of the opening poem-section, “how Ilive in such a city.” If Franklinstein wrote out Landers’ roots, WhatTo Carry Into the Future writes of where she has chosen to land, weaving throughthe spaces and traces of geography, history, currency, chaos and gesture. “Thismay be / a love letter.” Landers writes, “This may be my vows.” A few linesfurther: “You always win, / New York. / You always get / whatever you want. /But I can still lay / tracks inside you, / reinscribe in lines / the old names/ we have for each other— / Atlantic, Pacific— / how the maiden names stick, /familiar as an ocean, / along the elevated track.” Curiously,the first two sections also begin with short introductory notes, whereas the thirdand final section includes a sequence of paired notes and poems, almost as asequence of call-and-response pairings, fifteen sets with subject-titles suchas “Atlantic Ocean,” “Gowanus Canal,” “Coney Island Creek,” “Spuyten DuyvilCreek” and “Harlem River.” Throughout the collection, Landers moves through theunderground of city as she writes of history, landmarks and landscapes, watersystems, death, an unsolved murder, floods in Texas, capitalism, seasons and Columbus,offering threads on what remains and what holds, the seen, unseen and buried, whathad been and should not be forgotten. “Line by line // to build such // tenderthoughts.” she offers, as part of the second poem-section, “To know that I’m home.// Like, // really, // even in the gravity of it all.” However rebuilt oroverbuilt, history is held in place through place, which itself remains asmemory. “Every day // we choose // what to carry // into the future.” shewrites, to end the second section, a sequence of poem-fragments that accumulatealong a slow and steady path, “Today, // there are seed pods // on the honeylocust. /// And look, // that one // there— // —it has thorns.” Or, as thesecond part of the paired “Spuyten Duyvil Creek” writes:

Where the devil spews acurrent

and the crow caws underthe high-rise

past the swing bridgewhere the train

horns blow and the ospreyhunts

on the rocky promontoryinside the glacial

potholes where marblelies beneath the schist

above a witch hazelunderstory between

the ridges in the wadingplace beside

the cove and the nightheron’s mudflat

near the scullers the recoveredmarsh

the place of the reedsthe flooded path

the glistening placewhere I saw that rat

and the sandpiperreleased its metallic spink

at the tip of the islandon my day off.

April 11, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Shannon Arntfield

ShannonArntfield is asecond-career trauma informed therapist whose work explores the challenges andrewards of saying ‘yes’ to all of life’s effluence. Her first full length bookcollection Python Love was published by the University of Alberta Pressin February 2025. Her debut chapbook Fallen Horseman was published byAnstruther Press in 2023. Individual poems have been featured in CV2, PRISMInternational, The Antigonish Review, The Examined Life Journal,and Snapdragon Journal. She lives in London, Ontario.

Arntfield launches Python Love in Ottawa on April 15 at Octopus Books, alongside Christine McNair.

1 - How didyour first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m not sure it‘changed my life’. But something invisible became visible – which offered asense of coherence, of integration, in my personal and professional life. Whichfeels really good. The publication process also engendered a ton ofinterconnectedness – which was very developing. Between me and parts ofmyself, which was healing, and between me and others – my editor, thepublishers, colleagues who are helping me promote it, the community who comesto listen – all which has been simultaneously humbling and encouraging.

I’m working on asecond full-length manuscript now (just submitted a chapbook length excerptover the weekend – eek!) for something quite different – on the theme of ‘Initiation’.It connects to Python Love, because it extends my exploration of the waysin which love and suffering are inexplicably and inextricably linked – but itgoes wide instead of just deep – looking outwards to the archetypal andenergetic voices that inform our understanding of our connection to others andthe natural world.

2 - How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I would say itcame to me, as opposed to the other way round. I tried to write fiction – butit always fizzled…like I didn’t have the imagination to develop and sustain theideas and the characters. Poetry appealed to me in being so spare, so essential,so urgent. So completely dependent on being boiled down to the bare essence,to honesty and directness. All of that feels right, and resonant, withwhatever or whoever it is inside me that needs to write.

3 - How longdoes it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s both. Some poemsjust come. In a flood, in a single moment – waking me up from sleep, alreadyfull and complete. Others have taken me over 10 years – several of which are inPython Love. The idea was there, but I wasn’t ready…or it wasn’t fullyformed yet, or both. More things needed to happen – personally andprofessionally – for it to open, for me to understand, for me to have thelanguage to share it.

4 - Where doesa poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

The former.Though my awareness of what I’m working on – the themes and my synthesis of it– is coming much more quickly as I work on my second book.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I’m not sure yet!I brought a lot of public speaking experience with me from my first career, inboth large and small gatherings – and I have a longstanding commitment to beingauthentic – but poetry readings are perhaps the first time where I am encouragedand invited to do both things simultaneously. Medicine is famous forrequiring a veneer and impermeability when in front of others – nothing issupposed to affect you – but that never felt natural, and I fought against italways. The risk/reward ratio of being vulnerable and human amidst professionalengagements, however, often came with experiences of being ‘othered’ – offeeling misunderstood, of being perceived as weak, of swimming upstream. Poetryis amazing because it is just so honest, and people who gather to readand listen to poetry are – consciously or unconsciously – often seekingauthenticity, truth, and connection. We are all just human, and when weare surrounded and invited to participate in that experience with others, itfeels good. I mean, it feels uncomfortable too…but that friction is productivewhen you let it be – when you say yes to it. So yes – I’d say readings are partof my process. Though I didn’t know it was until you asked me.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

I’ve worriedabout telling other people’s stories – both personally and professionally. Weall have such different experiences – even when we’re in the same room, beingexposed to the same stimulus – and I am aware that my version of what happenedmay not be reflective of, and could even be in competition with, someone else’sexperience of the same event. And, I’ve worried about upsetting people withwhat I write about – the medical sections of Python Love would neverhave been a thing if I hadn’t been encouraged by one of my writing groupmembers to develop a short poem I submitted one week. I didn’t think anyonewould be interested – and I was worried about injuring someone else throughsharing my experience. It turns out people are interested – at least I have toassume they are, given that the book was promoted and published – and I’velearned I have to trust people to do what is best for them, both in theirdecision to listen (or not) in the first place, and in caring for themselvesafter, if they choose to engage.

The kinds ofquestions I am trying to answer?

Why and how do we become?

What is the role of love and suffering inour lives?

Why do some people open, and some peopleclose, in response to their experience?

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To ask questions.To invite curiosity, and reflection – of self, and of others. To tell the truth– yours – and invite others to do the same. To take risk. To add your voice tothe masses, trusting it’s important – while simultaneously recognizing that youare a speck of dust. To learn from others. To be open.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

Both. Though Ionly have so much experience, let’s be honest. When U of A Press accepted mymanuscript, they offered/accepted the opportunity for me to continue workingwith my existing editor, Jim Johnstone. That was amazing – the project and thewriting felt super vulnerable, many of the poems being directly about trauma –and I was so grateful to continue working within the safety net that Jim and Ihad established. Having said that, the first stage of the U of A processinvolved responding to two independent and anonymous reviewers, who had providedfeedback on the manuscript that I had to either incorporate or justifydeclining, in order for the manuscript to pass through from acceptance to aformal invitation and contract. And that was challenging. Edifying, butdefinitely challenging.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

a) Just keep submitting - aim for 100rejections a year.

b) Only submit when you feel moved to.

10 - What kindof writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I intentionallyblock off two days a week for writing. I don’t always use them – but they arealways available.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

I just wait. Iknow it will come. In the meantime, I do the things I know are supportive, andresourcing. I read. I journal. I talk to other people. I meditate. I pray. Ikeep working. I keep parenting. I keep relating. I keep curious.

12 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

My mom’s perfume.The ocean. Windy rain.

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature is a bigone - the biggest. Institutions where systems and people intersect would beanother – medicine, faith, and faith-based practices and scriptures. And mostrecently, visual art – specifically the practice of SoulCollageÒ , which has been the basis for many of the poems in my secondmanuscript. In SoulCollageÒ, I work with the energy emanating from avisual medium (which I created, using an intuitive collaging process). Thatenergy ‘speaks’ with a voice of it’s own, which I then record. In some cases, apoem results from the process – which has been a fabulous and wholly new way ofwriting that’s been both expansive and exciting.

14 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

15 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Go wild in someway, in self-expression.

16 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I surprisedmyself and other people by already doing this – leaving medicine to become atherapist. The choice was coherent with my ‘pluripotent’ younger self, whocouldn’t decide between medicine, ministry, and counseling. Now, I feel like Ido all three.

17 - What madeyou write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had to.

18 - What wasthe last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I don’t watch alot of films…so I’ll take the opportunity to plug Amor Towles and Ann Patchett –literally anything they write.

19 - What areyou currently working on?

A perfect loop!See question 1.

Thanks rob! Thiswas really fun J

April 10, 2025

David Dowker (May 20, 1955 – March 24, 2025)

Sadto hear that Toronto poet David Dowker has died, after an extended illness. He wasalways quietly generous with other writers, slipping into small press fairs tosay hello, making his way from table to table. I first heard his name in the1990s, through his online journal Alterran Poetry Assemblage, probablyfirst through the SUNY-Buffalo list-serve, offering publication to a wholerange of experimental poets and poetry, showcasing work that pushed at theboundaries of what might be possible. He was a champion for experimentalwriting, although never one to push his own work too hard, although that wasthere, also. Some of his publications over the years include Machine Language (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010), Virtualis: Topologies of theUnreal (with Christine Stewart; BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here], Mantis (Tuczon AZ: Chax Press, 2018) and Dissonance Engine(Book*hug, 2022) [see my review of such here]. I was fortunate enough toproduce a chapbook of his, Chronotope (2021), through above/groundpress, he guest-edited issue #23 of GUEST [a journal of guest editors] in 2022, and I interviewed him in 2019 for Touch the Donkey [a small poetryjournal]. He had been an above/ground press subscriber and supporter formore years than I can count, and always attempted to come through small pressfairs to say hello if I was ever in Toronto. I shall miss his quiet dedicationand attentiveness. He was a kind man.