Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 15

May 29, 2025

some reviews + interviews re: On Beauty: stories (University of Alberta Press, 2024)

I've been feeling very fortunate for the amount of reviews/interviews around my collection of short stories,

On Beauty: stories

(University of Alberta Press, 2024), a book not yet a year old. And might we see you this afternoon at the Made in Alta Vista Market? Jim Tubman Chevrolet Rink, 2185 Arch Street, Ottawa (outside the Canterbury Recreation Complex). I'll have copies of On Beauty available for sale (along with a whole slew of other books/chapbooks etcetera) from 4-8pm. Come on by! And don't forget I'm reading in Ottawa with Amanda Earl and Christine McNair this coming Sunday! June 1, 2pm at the Lieutenant's Pump at 361 Elgin Street (most likely from a slew of unpublished work, fyi)

I've been feeling very fortunate for the amount of reviews/interviews around my collection of short stories,

On Beauty: stories

(University of Alberta Press, 2024), a book not yet a year old. And might we see you this afternoon at the Made in Alta Vista Market? Jim Tubman Chevrolet Rink, 2185 Arch Street, Ottawa (outside the Canterbury Recreation Complex). I'll have copies of On Beauty available for sale (along with a whole slew of other books/chapbooks etcetera) from 4-8pm. Come on by! And don't forget I'm reading in Ottawa with Amanda Earl and Christine McNair this coming Sunday! June 1, 2pm at the Lieutenant's Pump at 361 Elgin Street (most likely from a slew of unpublished work, fyi)I recently caught Andrew Torry's review over at Alberta Views, which is pretty good, but it was Salma Hussain via The Temz Review that is easily my favourite (she really gets what the book was attempting/doing, etcetera). There's also Michael Greenstein via The Seaboard Review, Joyce MacPhee via Apartment613, Natasha Baldin via The Charlatan, the piece "8 Alberta Books That Don't Follow the Rules" at ReadAlberta.ca (is mine an "Alberta Book"? I mean, it was produced by a publisher in Alberta; does that make it an "Alberta Book"?), Alice Violett via her blog and J Jill Robinson, via Goodreads. So nice! Hugely appreciating how many folk are responding at all, let alone so positively. As well, further reviews of my work I've linked over here, on my author website.

There have even been a few interviews around the collection, which is pretty cool. Hollay Ghadery and I discussed the collection as part of the New Books Network podcast not long back, via JWT BookAdventures, reposted for reading ease at my clever substack, with Jamie Tennant over at his podcast last fall, with Ivy Grimes via her substack, and with the delightfully-brilliant Alan Neal as part of CBC Ottawa's All in a Day, which was enormously cool. As well, further interviews I've done exist over here, in case such appeals (there's a whole bunch of them, including some other recent ones). Here's hoping I can place the follow-up collection, which has been making the rounds since last summer (and hopefully this year I can complete the novel-in-progress that sits between the two collections, finally). And, naturally, there's always that small part of me that wants to get all of this off my plate so I can begin to dig deep into some new prose-thoughts I've been having lately around The Crystal Palace, of all places. Where might that go?

May 28, 2025

Norma Cole, Alibi Lullaby

Halo of Blood

oblivious to others

the same hour

apparent order

or actual order

sugar and candle

stand up

fingers of rain

walk without

contradiction

come on

witness the set

another time

Thelatest from Toronto-born San Francisco poet, translator and editor Norma Cole,following numerous titles over the past decade-plus including

Where Shadows Will: Selected Poems 1988-2008

(San Francisco CA: City Lights, 2009) [see my review of such here],

To Be At Music: Essays & Talks

(RichmondCA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2010) [see my review of such here],

Coleman Hawkins Ornette Coleman

(Providence RI: horse less press, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Fate News

(Omnidawn, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

RAINY DAY

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book, 2024) [see my review of such here], isthe poetry collection

Alibi Lullaby

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2025), a book-lengthsuite of sharp, short lyrics. Cole’s short poems sit as accumulations ofclipped phrases, stitched and quilted lines and phrases that hold to sound andsensation, rhythm and reading, tone and temper. “take a book for instance,” shewrites, as part of “On the Sensations of Tone,” “melody incomplete / inexact orparadise // the last to know / accuracy a moment / or the last to know [.]” Throughhalts and hesitations, parsed language and precision, Cole’s poems move throughcadence and sound as much as into and through meaning. Moving betweencompression and accumulation, her narrative moments set one upon another revealinglarge, sweeping truths and small mercies. “silent objects / saturation not able/ inside the magnitudes / suppression,” she writes across the single sentenceof her second poem titled “Mum’s the Word,” “oppression / falling, failing / oblivious[.]”

Thelatest from Toronto-born San Francisco poet, translator and editor Norma Cole,following numerous titles over the past decade-plus including

Where Shadows Will: Selected Poems 1988-2008

(San Francisco CA: City Lights, 2009) [see my review of such here],

To Be At Music: Essays & Talks

(RichmondCA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2010) [see my review of such here],

Coleman Hawkins Ornette Coleman

(Providence RI: horse less press, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Fate News

(Omnidawn, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

RAINY DAY

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book, 2024) [see my review of such here], isthe poetry collection

Alibi Lullaby

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2025), a book-lengthsuite of sharp, short lyrics. Cole’s short poems sit as accumulations ofclipped phrases, stitched and quilted lines and phrases that hold to sound andsensation, rhythm and reading, tone and temper. “take a book for instance,” shewrites, as part of “On the Sensations of Tone,” “melody incomplete / inexact orparadise // the last to know / accuracy a moment / or the last to know [.]” Throughhalts and hesitations, parsed language and precision, Cole’s poems move throughcadence and sound as much as into and through meaning. Moving betweencompression and accumulation, her narrative moments set one upon another revealinglarge, sweeping truths and small mercies. “silent objects / saturation not able/ inside the magnitudes / suppression,” she writes across the single sentenceof her second poem titled “Mum’s the Word,” “oppression / falling, failing / oblivious[.]”

May 27, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lorri Neilsen Glenn

LorriNeilsen Glenn’smost recent books are The Old Moon in Her Arms: Women I Have Known and Beenand an updated edition of Threading Light: Explorations in Loss and Poetry (Nimbus,2024) and Following the River: Traces of Red River Women (Wolsak andWynn, 2017). Her work has appeared in Prairie Fire, The Malahat Review, ThisMagazine, Juniper and numerous anthologies (Bad Artist, Good Mom onPaper, Sharp Notions: Essays from the Stitching Life), among otherpublications. Poet Laureate Emerita of Halifax and Professor Emerita, sheteaches in the University of King’s College MFA program in Creative Nonfiction.Lorri lives in Nova Scotia.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was my dissertation, published as a book. As a narrative,it sat somewhere between scholarly and trade and I recall the thrill of seeingit show up in the public library system. It was an ethnography filled withlocal stories and, although everyone had freely given permission for me towrite about them, it caused a fuss with a few people. It reinforced for me howpowerful the written word is. My recent book, The Old Moon in Her Arms,seems to be the closest I’ve come to telling my own story in ways that might appealto me as a reader.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

After writing and editing scholarly books, I began to write poetry at 50at the suggestion of a novelist friend who’d read my work. I’d always chafed atthe often agonistic nature of academic writing, and back then it seemed usingfigurative language in research was a bit suspect, lacking gravitas perhaps, afrill or indulgence, when it was naturally how my mind works. Writing poetrymade me fall in love with the possibilities of language all over again.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

My writing comes slowly. My books come slowly. Unless it’s aresearch-informed work, I don’t take notes. I simply start writing and see whathappens. I’m a string-saver. Soon I become aware of themes emerging and if it’snonfiction, such as memoir, I typically need several drafts; if it’s poetry,sometimes dozens. Revising is my favourite part.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Except for a couple of anthologies I’ve edited that had a specific goal(the lives of 1950s mothers, for example), I usually write short pieces orpoems about what’s on my mind at the time, then if the pieces seem to be gellingin some way, I will then write to that theme. My Red River book (Followingthe River: Traces of Red River Women) came about as a request from mycentenarian aunt who wanted to know the story of her grandmother’s death; aftera year or so, my field notes and journal entries from my travels to NorthernManitoba began to feel like the beginnings of a book. When I realized theprofound absence of the stories of Cree and Métis women in the archives and inhistory books—actually, the erasure—the personal search turned into a projectto try to give those women, along with my grandmothers, a presence, a voice.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’m deeply introverted, but teaching and public events have forced me tolearn to override that part of my character. I like readings, yes, and writers’gatherings, and I love hearing other writers’ works. A voice in a room bringsanother dimension to the work, deepens it somehow. I’m not sure if my ownreadings are part of my creative process, but being inspired by others’ writingis.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

What’s woven in my writing the last decade in particular includeenvironmental degradation, climate change and the global assaults on women andgirls (domestic, institutional, cultural, social, political and more). I mournthe loss of our ability to attend to one another and to honour the naturalworld. I refer a lot to wahkohtowin, the Cree concept of kinship, theinterrelationship of all things—land, people, flora, fauna, all of it—aconnection that implies responsibility and care.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

While more books are being published than ever before, it seems fewerpeople are reading whole books, especially young people. Like all artists,writers can document, question, warn, remind, honour, celebrate and provoke,but only if we’re heard or seen and valued. The arts enlarge our perspective,offer us beauty or stimulation, introduce us to untold stories, particularlystories we need to make room for. I’m grateful for the Canadian writingcommunity—writers in this country seem to be more about the writing itself, howand why it matters, than about climbing a bestseller list.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

Editors are essential. I love working with them. We can’t see ourselvesclearly without a mirror. Books can take a long time to write, so why publishthem without a good edit? The strongest writers I’ve worked with seem to be themost enthusiastic about receiving editing suggestions. Regardless of ourexperience, we’re all still learning.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Thenpractice losing farther, losing faster:

places,and names, and where it was you meant

totravel. None of these will bring disaster---Elizabeth Bishop

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toessays to memoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s not the genre that leads me—it’s the moment or the topic or theitch or the stone in my shoe. Only once I start writing do I learn whether thematerial wants to be poetry or prose. Both appeal to me—and I love blurring thelines between them. I try to resist hardening of the categories.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no routine. Jamaica Kincaid said she’s always been amazed bywriters who have routines. “They seem mostly to be men,” she says. If I canfind a quiet hour or two with no one around—usually any time during the day—Ican write. By around 9 in the evening, though, my mind stops working—when I wasyounger, it was the other way around. Now that my children are grown, I havethe luxury of starting a day with coffee and staring off into the middledistance. If I’m lucky, it leads to writing.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading other people’s work—anything from science to research studies topoetry to fiction. An art gallery. A walk. Music of all kinds. Anything thatshakes up the neural pathways in my brain.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I’m not sure. I couldn’t tell you what fragrance is in my home now (likethe fish who can’t see the water it swims in). Old Spice aftershave used toremind me of my father, the odour of rising dough reminds me of the early daysof being a mother when I seemed to bake a lot of bread. Dry grass in the hot summercalls forth my prairie years; the salt of the sea reminds me of days at thebeach with my children.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

All of them. Anything, really. I found a couple of ladybugs on thewindow this morning—they got me thinking. The roaring wind I hear as I’mwriting this. The whitecaps on the water. The sounds of the guy repairing theeaves on the house. Seeing a name in my contact list and remembering the friendhas died.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I’m a big fan of podcasts—and although they’re aural, not print, I canlisten to an author read their work, a scientist explain an aspect of thebrain, a psychologist describe personality disorders, a stoic describe dailyhabits. It’s all information that feeds my curiosity.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Sleep for eight hours at a stretch.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

Perhaps a visual artist of some kind. I often joke I’d like to have beena country singer. I have a couple of chords and partial truths, but I don’talways sing in tune.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Probably reading. Once I was of an age to fill the basket of my bikewith a pile of books from the library every week, my curiosity was piqued aboutlives beyond my own. Later, I realized we are all stories and it’s important wehear or read one another’s.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great filmyou saw?

Ooh, too hard, and too many. Claire Keegan’s So Late in the Day andSmall Things Like These stay with me. As do Christina Sharpe’s OrdinaryNotes and John Vaillant’s Fire Weather. Great film? I think theSouth Korean movie, Past Lives.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Since my most recent book was published, I’ve spent most of my timedoing readings and giving workshops. Occasionally, I’ll draft a poem. I’m in afallow period now, I think, so I read, live my life, try to stay open andcurious. Something will emerge.

May 26, 2025

Carrie Hunter, The Flow of the Poem’s Display of Itself

The light patched uplater, after the fact.

The conversational you,interjected.

Bright, snazzy, fabulousslownesses, fantasticality.

Skipping a comma just tothrow you.

The center disappears inthe middle.

The furniture, what wewalk around,

use’s communication

came to beseen, comes, to seam.

If you view yourself fromwithin the ecoterritory,

and no separate from,

there is no need toreplicate the self. (““Finally, the Memory Became an Object””)

I’mvery pleased to see a new poetry title by San Francisco poet, editor and chapbook publisher Carrie Hunter,

The Flow of the Poem’s Display of Itself

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2025), following The Incompossible (BlackRadish Books, 2011), Orphan Machines (Black Radish Books, 2015) and

VibratoryMilieu

(Brooklyn NY: Nightboat Books, 2021) [see my review of such here].Composed in four sections of poems—“Richly Flows Contingency,” “All GabledRoofs Will Fall,” “Poetry’s Anti-Monument” and “The Flow of the Poem’s Displayof Itself”—the accumulated poems read akin to a thesis, offering a book ofpoems on and around poetic structure. “I’ve heard that the subject matter is onits way.” begins the poem ““Glamour and Chrystoprase”,” “No saying exactlycreates a space to pull meaning out of / vs a specificity which is useless.// Memories mixed up, only recognized as such through changing pronouns.” Thesepoems are nimble, punch-smart and quick, stretching out across a wealth ofliterary reference and citation, as Hunter offers a book on lyric and poeticform, even arguing poetic form as inadequate through those very structures. As shewrites in the poem ““Gravity Isn’t About to Save Us””: “The difference betweendisintegration and return. / Awareness as a scientific measurement.”

I’mvery pleased to see a new poetry title by San Francisco poet, editor and chapbook publisher Carrie Hunter,

The Flow of the Poem’s Display of Itself

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2025), following The Incompossible (BlackRadish Books, 2011), Orphan Machines (Black Radish Books, 2015) and

VibratoryMilieu

(Brooklyn NY: Nightboat Books, 2021) [see my review of such here].Composed in four sections of poems—“Richly Flows Contingency,” “All GabledRoofs Will Fall,” “Poetry’s Anti-Monument” and “The Flow of the Poem’s Displayof Itself”—the accumulated poems read akin to a thesis, offering a book ofpoems on and around poetic structure. “I’ve heard that the subject matter is onits way.” begins the poem ““Glamour and Chrystoprase”,” “No saying exactlycreates a space to pull meaning out of / vs a specificity which is useless.// Memories mixed up, only recognized as such through changing pronouns.” Thesepoems are nimble, punch-smart and quick, stretching out across a wealth ofliterary reference and citation, as Hunter offers a book on lyric and poeticform, even arguing poetic form as inadequate through those very structures. As shewrites in the poem ““Gravity Isn’t About to Save Us””: “The difference betweendisintegration and return. / Awareness as a scientific measurement.”Denise Newman’santi-paradise, Dana Teen Lomax’s guilt.

Model of possibility,“your” possible situation.

An old “chromo” on thewall, innocent as a “lintel.”

Hate-filled cubicle jobs

and how that leadsto an explanation

of what Osiris would do.

How snow is truth and howyou show truth.

Against reinvention andfor becoming more and more the self.

Votive angel gatekeeper’sactions at the gate. (““The Saga of the Sheepgirl and Her Friend / the PelicanMerchant””)

May 25, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Madeline McDonnell

Madeline McDonnell’s latest book is the novel Lonesome Ballroom (Rescue Press, 2025). You can find her in Oregon, or here

Madeline McDonnell’s latest book is the novel Lonesome Ballroom (Rescue Press, 2025). You can find her in Oregon, or here

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Picture me at my desk, sometime in the late aughts, a credulous, timorous rictus stilling my face. Argh!? My rictus was supposed to be a confident confidence woman’s! The agents who’d visited my MFA program had counseled chicanery, after all… According to them, I had nearly enough stories for a collection-nobody-would-ever-read, a collection they might be able to trick a corporation into buying if I pretended I had a novel. I’d been working at amassing the words that might abet this lucre-producing lie, not thinking about the rot at its center, just thinking I couldn’t look at my trick doc any longer. So I checked my email, dead heart near-beating with expectancy even though I had nothing to expect… But lo! A message from two incredulous, incredible friends. They’d started a small press and wanted to publish a brief book of big stories—three of my longer ones, if I’d let them. Wha—!? Just three!? I hadn’t thought such a book possible, but why not—when omne trium perfectum—when I could immediately see the three that needed to be one, that were already speaking to each other even outside the covers to come—

I think about this moment all the time, and still cannot believe my luck. One click, and there!: a revelation and reminder that a book might be only what it wanted and needed to be.

Lonesome Ballroom is the novel this early and essential correction made possible. A campus novel / tale of movie-watching, marriage-plotting, and mother-daughtering, it is also a swirling/twirling/whirling wannabe movie musical, a 32-bar-ballad-in-222-pages, a nascent 5.5x8 gallery exhibit featuring photos by actual fantastic photogs, and a 3-D art-creature whose right-side-up-upside-down cover doubles as a lachrymose laser-launcher.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

When I was a kid, I’d read these retrograde manners guides masquerading as radical mysteries for hours, delighting less in their wacky events than their wack voice: Nancy Drew, an attractive girl of eighteen, was driving home along a country road in her new, dark-blue convertible. She had just delivered some legal papers for her father. “It was sweet of Dad to give me this car for my birthday,” she thought. “And it's fun to help him in his work.” Afterward, I’d still hear those wicked, restrictive rhythms: Madeline McDonnell, an attractive girl of eight, was walking into the kitchen because she wanted a snack. “It was sweet of Dad to buy these Chips Ahoy,” she thought. “And it’s fun to eat them!” F*cked up, yes! But from then on I dreamed of making (and messing with) that sort of authoritative story sound, of changing the score of my own—and others’—interiors.

In college, I became passionate about poetry, and wrote a lot of lines featuring mythical figures about whom I knew almost nothing, and a long series of Meadowlands-esque dialogues between a me-speaker and her faithless boyfriend. Maybe I knew I could never achieve greater poetic glory than when I was given the oddball opportunity to read that sequence aloud to a workshop whose students included said FB!? Or maybe I stopped writing poetry because my fiction accommodated the jokes that the strained restraint of my wannabe Louisean lines wouldn’t abide.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

There was this one time I started typing out a story I’d only just begun thinking about. While I was typing, a person came into the brightly lit room (I usually close the blinds and barricade myself) and started talking to me (i.e. messing with the music of my prose!?!?) and I didn’t even get mad, I think I actually might have responded, if distractedly? I finished the story maybe 20 minutes later, then sent it to a magazine I’d long admired (I never send out anything), where it appeared soon after.

That said, I started the book that would become Lonesome Ballroom in 2008 and I was still making not insignificant edits the night before it went to print this January, 2025!

By these calculations, any particular writing project takes me an average of 8.25 years, which actually isn’t that bad?

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Hm… The works that have become realest seem to require that I derealize their origins. I suspect they usually arise from some overlap between what I’m reading and what I’m lying to myself about?

I think more about “books” now that I’ve made a few and understand how the object can make the text mean more, and mean more clearly and complex-ly (!?). Also, I have two little kids, and, though parenting makes it harder to sit for concentrated hours in a chair and write, it doesn’t interfere that much with thinking about what I would like to be writing, so I’ve had a lot of time to sort my ideas into secret brain-bound containers I’m hoping will one day be physical books. If my life were different, I might spend more time writing, less time sorting/book-planning—I’m not sure!?

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Many have noted the useful pressure a public performance can place on a private, page-bound performance. But this note bears resounding, maybe? I’ve been flummoxed by phrases for years, only to see them come clear in the moment before I say them aloud to a crowd. Can we fix this!? Probably not, so thanks to all those intrepid souls who organize readings! Another reason for thanks: reading is the best, so it feels only right that we get dressed up and have parties for it from time to time even if they’re not as wild as this one.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My work has long been curious about whether conventional narrative shapes (particularly those of the climactic-Freytagian-pyramid-causal-event-chain ilk) are the best containers (or even mediocre containers!?) for stories interested in feminine cultural practices and reproductive labor.

I am also wondering how I might become an intentional, rather than, accidental researcher. As I worked on Lonesome Ballroom, subjects and texts I had long knowledge of, or was drawn, frictionlessly, to, informed my subjects and found their way into my text, which ultimately became “an inquiry into gender’s relationship to popular aesthetics that swirls from ancient epics to turn-of-the-millennium reality shows, mid-century melodramas to neo-noir car chases, beauteous battle scenes to boy-next-door meet-cutes,” per my flap copy! Now I’m trying to write about some things I’m afraid to know, and I’ve found I’m not very good at learning about such things, go figure!?

As for the current questions, they seem manifold! Urgent! But for me, the main one is more practical than theoretical: how do we get people to read more literature (esp. when the attention economy has turned so many of us into at least partial objects rather than subjects, the most devalued, no-good goods!). This podcast doesn’t answer that question exactly, but its erudite hosts, Hilary Plum and Zach Peckham, are building “an archive of grassroots knowledge that serves the future of publishing,” and it is both a galvanizing and a soothing archive, o strange and wondrous combo!

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Well, one thing a literary writer might do is articulate experiences and even truths (!?) that are reduced, or, worse, turned into slick, initially soothing, but ultimately desolating lies by more explicitly societal modes of discourse (whether the awful argot of in-person or online sociality, the oft-mocked overcirculated jargon of the academy or religion or name-your-institutional-mass, or even the essential, life-saving, culture-changing language of political action, visionary policy, or persuasive public dissent). Maybe one writer can complicate and contradict and confess in the way a social collective cannot, which, strangely, beautifully, can enable a more profound collectivity?

And maybe a writer should also proselytize about the power of reading here or there, esp. as reading is ever more disempowered in our culture? When I say “our culture,” I’m referring to the one that’s insidiously distracted from the workings of power by the very powermongers fracturing its attentions; ongoingly depressed and suppressed by so-called “market demands”; and increasingly isolated inside dying urban, suburban, rural, and linguistic structures! Attending closely, and for long intervals, to the more vital structures inside our literature can maybe help with these problems?

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I am lucky because the “outside editor” I have worked with most is not really so outside, given that there is a Caryl-Pagel shaped ventricle in my heart, and a synaptic cleft in my brain hosting this ongoing neurotransmission: Neuron 1: “C!” Neuron 2: “P!” There is no editor better than CP if you’re looking to rescue what you didn’t even know you’d lost, i.e. the intra- (stylistic, formal, narrative) and extra- (bookmaking, promo-as-performance-and-collaboration) textual possibilities you were too terrified to see. I am especially lucky to have her not just as my editor, but as one of my early readers: where normies might just see a mess, she discerns the better book I don’t yet daydream of, and explains which narrative and stylistic choices sent her these complex, and unexpectedly encouraging, secret messages.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I had a so-wonderful-she’s-actually-kind-of-famous English teacher in high school who gave out a list titled “What Every Sophomore Should Know” (I think!? Forgive me, Mrs. G., if I’m misquoting), featuring a delightfully rangy range of recs for living. One I remember: Marry Late. A good edit might be: Marry Later. Like, do you really need to do it now?

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m not teaching right now and so have been trying to write when my kids are at school. Keeping this routine is complicated by the way a typical day begins for me, which involves dragging myself and three other humans out of bed before the sun has risen, picking some !@#$ up off the floor, feeding and clothing a bunch of people, picking some more @#$ up off the floor, yelling or telling others to stop yelling, picking some additional @#$ up off the floor, driving blearily around, crying, making a bunch of beds (it’s psychologically disastrous to skip this step!), realizing I’m not even dressed, etc. By the time school starts, I’m often pretty tired, and the vision, concentration, and weird optimism writing can require often feel remote. But I try!

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Right now, stalled-ness seems to stem less from lack of inspiration and more from the exigencies I described in the previous response. Luckily, reading or walking around outside seem to help no matter my stalled-ness’s source.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The only place that really smells like the home I mostly grew up in, is the home I mostly grew up in. But if it’s summer and I smell sun on certain conifers I remember my grandparents’ house in Southern California.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes. Or, more accurately: OMG, where do I even begin!? I suppose I might as well b. with Lonesome B., whose form and composition were made possible by musical compositions and forms. When figuring out how to render the experience of a character who feels bitterly trapped but somewhat rapt by her trap, it helped to think of the tender trap that is a 32-bar American-songbook standard, the kind that kicks you out via the same rhythms and chord changes with which it invited you in. (But are you really out? Don’t you kind of want to play it again?) While working on LB I was also thinking about visual art: how crucial Sara Cwynar’s hyper-pretty palette is to her rigorous investigations of gendered consumer culture, how her retro (color) grades enable work that is anything but retrograde. Could I do something similar with the sentence, using syntactic and verbal “prettiness” as lure and cudgel, engine and blown gasket? LB’s main character, Betty, also thinks a bit about Cindy Sherman, and LB incorporates one of Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. I was definitely thinking about Cindy as I tried to find a structure for Betty’s story, the way UFS uses received (patriarchal) cinematic tropes, but builds an entirely new, non-causal, anti-action structure to contain and thereby remake them. Joan Brown’s wild couplings (flat encaustic stasis + mobile patterning; cartoonish colors + gritty weird scenes; composed/performed set-ups + discomposed/not-fully-readable subjects, etc.) were also huge for me!

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A question whose responses I love reading (there are so many great recs in this series!), but one that’s tough to answer fully! So I’ll partially respond to the first clause (work) by naming two idols whose last names begin with the excellent (am I rite?) letter “e”: Deborah Eisenberg and Jenny Erpenbeck, and by linking to this little list of books that have helped me think about structure.

And I’ll answer the second clause (life outside) by naming a few children’s books that a) aren’t glutted with the saccharine and coercive falsehoods endemic to the genre and b) are as likely to delight a five-year-old as they are a ten-year-old or a forty-five-year old (all ages currently represented in my household): Telephone Tales by Gianni Rodari, the Moomin novels by genius Tove Jansson, all the Dory Fantasmagories by Abby Hanlon, and the goat, The Complete Polly and the Wolf, by Catherine Storr. I hope this helps some depressed literary parent out there!

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d love to make “a wage” for (/against!) housework!

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Audio book reader?

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In my youth, I loved the total transportation out of myself the performing arts could effect… But then I’d be in a play or onstage playing music and find myself seized by performance-sabotaging ideation. I discovered that when I was writing I could not only find similar transportation and me-obliteration, but also that those intermittent intellectual interventions made my work better rather than worse. In other words, writing required both thinking and not-thinking, self and non-self, and I was glad!

More practically, I was never very good at anything more practical.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Star Lake by Arda Collins. Diary of a Pregnant Woman by Agnès Varda.

19 - What are you currently working on?

In the hope of not getting trapped in the same novel for the next 16-17 years, I’ve started several books at once. Maybe if one book isn’t working I can pause and work on another? But so far this is just making me feel like I might be in this new morass for 48-51 years? So…see you back here when I’m 93-96, I guess?

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 24, 2025

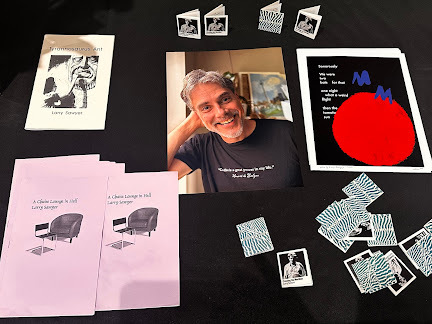

periodicities: Judith Copithorne, Larry Sawyer + Alice Notley,

With the recent losses of Vancouver poet Judith Copithorne (1939-2025), Canadian-American poet Larry Sawyer (1970-2025) and American poet Alice Notley (1945-2025), there have been a couple of memorial pieces posted for each of them over at

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

. Amanda Earl offered her notes on Judith Copithorne, as did Eric Schmaltz. D.S. Black wrote on Larry Sawyer, an American poet who spent years in Chicago but moved to Toronto during the first Tr*mp administration, and Alina Stefanescu wrote on American poet Alice Notley. More pieces are forthcoming, possibly.

With the recent losses of Vancouver poet Judith Copithorne (1939-2025), Canadian-American poet Larry Sawyer (1970-2025) and American poet Alice Notley (1945-2025), there have been a couple of memorial pieces posted for each of them over at

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

. Amanda Earl offered her notes on Judith Copithorne, as did Eric Schmaltz. D.S. Black wrote on Larry Sawyer, an American poet who spent years in Chicago but moved to Toronto during the first Tr*mp administration, and Alina Stefanescu wrote on American poet Alice Notley. More pieces are forthcoming, possibly.May 23, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with John Amen

is the author of five collections of poetry, including

Illusion of an Overwhelm

, finalist for the 2018 Brockman-Campbell Award, and work from which was chosen as a finalist for the 2018 Dana Award. He was the recipient of the 2021 Jack Grapes Poetry Prize and the 2024 Susan Laughter Myers Fellowship. His poems and prose have appeared recently in Rattle, Prairie Schooner, American Literary Review, and Tupelo Quarterly, and his poetry has been translated into Spanish, French, Hungarian, Korean, and Hebrew. He founded and is managing editor of

Pedestal Magazine

. His new collection,

Dark Souvenirs

, was released by New York Quarterly Books in May 2024.

is the author of five collections of poetry, including

Illusion of an Overwhelm

, finalist for the 2018 Brockman-Campbell Award, and work from which was chosen as a finalist for the 2018 Dana Award. He was the recipient of the 2021 Jack Grapes Poetry Prize and the 2024 Susan Laughter Myers Fellowship. His poems and prose have appeared recently in Rattle, Prairie Schooner, American Literary Review, and Tupelo Quarterly, and his poetry has been translated into Spanish, French, Hungarian, Korean, and Hebrew. He founded and is managing editor of

Pedestal Magazine

. His new collection,

Dark Souvenirs

, was released by New York Quarterly Books in May 2024.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It was thrilling, I have to say, when my first book, Christening the Dancer , came out. I was overjoyed, did numerous readings, got reviews, etc. That was 20 years ago! My new work, I hope, has evolved. Themes are different, style is probably less personal, family-oriented. The process of writing is still a thrill, typically. Publishing is enjoyable but also brings up so much of what isn’t great about being human: doubt, competitiveness, worry, and occasional hits of mania, which then, of course, lead to crashes.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I was always drawn to the form, the expressive and cathartic possibilities. I didn’t start out with narrative impulses, that seems to have evolved over time. I was very drawn to the surreal. Also, as a teen who struggled with various issues, including addiction, the way that poetry transformed ugliness into beauty was magical. I think writing poems, or at least aspiring to, saved my life.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Things sort of flow. I’ve been fortunate that I’ve never suffered from an extended block. I do tend to revise quite a bit, but there’s the occasional piece that emerges pretty much intact!

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Until my last book, Dark Souvenirs, I didn’t think or write in terms of an overarching theme, though Illusion of an Overwhelm did revolve around four series, so they were loosely theme-driven. I write poems, per se, individual pieces, but I do tend to think, How will these cohere in a book form? Will they?

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readings have always been a pretty big part of my post-release process. I do enjoy doing readings, and for years, traveled all over the place sharing work. Since Covid, things have slowed down a bit, and we’ll see how things unfold going forward. But generally speaking, I enjoy people and an audience, so I do hope to keep getting out there in some way.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

With some of what I’m doing now, yes. I’m working very much with the notions of impermanence, inconsequence, and non-self (Buddhist ideas). I’m not writing non-fiction, so I’m not spelling these things out, but they’re informing the work, yes. I’m not sure what I’m trying to answer as much as I’m trying to get at how a life unfolds so quickly, and regardless of what successes, failures, loves, and disappointments you experience, somehow there’s an emptiness or insubstantiality that endures. Memory isn’t exactly real; neither is self.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Good question! I’m not sure what the so-called larger role is, but I think art in general is important in the micro. In terms of literature, one writer, one reader. Art has small and important impacts. And of course, it’s primarily transportive for the artist or creator. A life in the arts can be rewarding, enriching, can even translate to being a better person. In the end, I think that everything, even if it seems to occur on a macro level, has an effect in a smaller way, one person at a time.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I work with editors more in terms of my music reviewing. I do quite a bit of music writing, and different editors have different approaches, preferences, etc. I find it rewarding for the most part, or at least a good exercise. Most editors have good suggestions. I also work as an editor, so I kind of know what it’s like from that side too.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Hmm, not sure, probably something around making sure you don’t miss out on your life because you’re so busy trying to write about it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I move between poetry and prose (music reviewing) on a regular basis. These days, even with poetry, I’m writing a good deal of prose poetry. Mining those overlaps between the linear and nonlinear, the poetic energy and prose grounding, is intriguing. I feel that the review process has certainly helped in terms of prose construction. But then, infusing that with the poetic flare is compelling. Now, in some ways, I’m not sure what I’m writing. Is it poetic prose, prose poetry? Maybe I should just refer to the pieces as texts.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t really have a routine, other than I try to write something or at least dive into focused editing every day. The morning is kind of busy with animals, etc., but I can usually get to a good stretch of writing by late morning or sometime in the afternoon.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Well, I usually wait for something to move me, or again, I dive into some revisions. There are various poetry and prose projects in the works, so I can usually get traction with something if I clear the space and commit to it. I’m also grateful that in terms of poetry I’ve always been able to land “where I am”, so to speak. I think sometimes people have blocks when they can’t authentically revisit earlier themes and yet don’t have a clear orientation about what’s happening in the present. Somehow I’ve been pretty consistent aligning my writing with my current state, even if I’m writing in the third person.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Grass, dogwoods, bay leaves. Smoke sometimes. Peonies. Sometimes certain cleaning products.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Oh, most definitely. Music for sure. Film. Art, yes. I would say that these other forms influence or inspire as much if not more than lit.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are numerous writers I’ve returned to over the years, and keep returning to. I’m also pretty engaged in Buddhist practices. I’m not sure if I’m a Buddhist, really, but the ideas and experience of impermanence and non-self are very important to me and have a greater and greater influence on my work.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to write a novel … or perhaps a memoir. I’d like to write some more songs (I wrote quite a few songs in the past but haven’t written many lately. That said, I do review a lot of music, which is very gratifying and inspiring). I’d like to travel a bit more.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I don’t know, maybe I could’ve taught lit somewhere. Or gone into mathematics. Or even pursued a more focused editing career. My dream job would be as a pro comedian, but I’m not fundamentally funny enough and I don’t know that I could generate humor consistently.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was always drawn to it, from the age of 12 on. It had a magic that nothing else had. I was hooked!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently reread Patrick Modiano’s Out of the Dark. The atmospherics in that book are extremely compelling, the way he creates a kind of European, post-WW2 dreamscape, how the past is so much a part of the present. And while I’m mentioning re-visits: Just re-watched Paris, Texas . The acting subtleties in this film are striking, how a simple dialog carries so much weight. A film brimming with implications, the spoken and the unspoken.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a series of new prose poems or, again, perhaps this is poetic prose. Certainly narrative driven, though the language and music are as important to me as ever. I’m reimagining/reconfiguring the lives of various figures, pointing out alternate life trajectories and how people make peace with emptiness, impermanence, even inconsequence.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 22, 2025

rob sells books at the made in alta vista market, participates in an above/ground press zoom reading + an upcoming in-person ottawa reading,

In case you hadn't heard, I’ll be tabling at the Made in Alta Vista Market in Ottawa on Thursday, May 29 at the Jim Tubman Chevrolet Rink, 2185 Arch Street (outside the Canterbury Recreation Complex), from 4-8pm, sitting a table attempting to sell copies of various of my books and chapbooks; you should totally show up. Curious to think we’ve been in this house long enough that I’ve now a handful of books now entirely composed here. Also next week, check out the above/ground press ZOOM launch we’re doing on Wednesday, May 28, 7pm EDT, with myself reading alongside Orchid Tierney (OH), Meredith Quartermain (BC), Brook Houglum (BC), Sandra Doller (NY) and Tom Jenks (UK), all of whom have recent above/ground press titles. Check here to join the event. I’m also reading in Ottawa on June 1, 2pm with Christine McNair and Amanda Earl at The Lieutenant’s Pump, 361 Elgin Street, most likely from unpublished work, including a short story and a handful of poems. I’ve been working on all sorts of things lately that you probably don’t know about. Secret, exciting things. (probably).

In case you hadn't heard, I’ll be tabling at the Made in Alta Vista Market in Ottawa on Thursday, May 29 at the Jim Tubman Chevrolet Rink, 2185 Arch Street (outside the Canterbury Recreation Complex), from 4-8pm, sitting a table attempting to sell copies of various of my books and chapbooks; you should totally show up. Curious to think we’ve been in this house long enough that I’ve now a handful of books now entirely composed here. Also next week, check out the above/ground press ZOOM launch we’re doing on Wednesday, May 28, 7pm EDT, with myself reading alongside Orchid Tierney (OH), Meredith Quartermain (BC), Brook Houglum (BC), Sandra Doller (NY) and Tom Jenks (UK), all of whom have recent above/ground press titles. Check here to join the event. I’m also reading in Ottawa on June 1, 2pm with Christine McNair and Amanda Earl at The Lieutenant’s Pump, 361 Elgin Street, most likely from unpublished work, including a short story and a handful of poems. I’ve been working on all sorts of things lately that you probably don’t know about. Secret, exciting things. (probably).

May 21, 2025

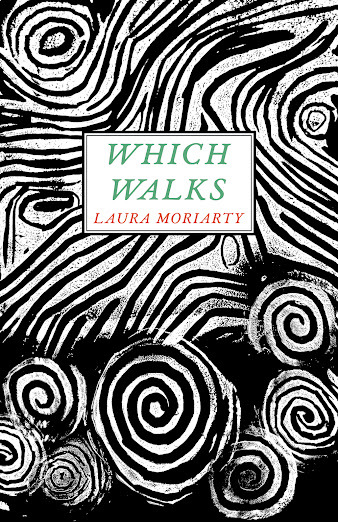

Laura Moriarty, Which Walks

AN OLD WOMAN WANDERS thepestilential streets. She sees herself from the outside. She feels like anarchaeologist of the present. She makes “finds.” At firs, she is afraid to pickup the items in case they are covered in viruses. Eventually she lets go ofthat idea and many objects appear on her worktable. Some are arranged intoboxes. She finds herself to be obsessed with metal, glass, game pieces,marbles, tools, jewelry, and figurines, and with assembling.

The days come together in the form of these objects andtheir arranging. The woman’s incessant movement is simultaneously search andresearch. Gradually the collected items (as with the words and notes collectedfrom each morning’s reading) are assembled. The practice of assembling morphsto one of attaching and building. At a local beach, once a dynamite factory,she discovers a source of sea glass and later, in a nearby town, one ofstained-glass remnants. She attaches them to a metal grid with aluminum wire. Ina lucky break, she has her first art exhibition of this and other works. She writesin relation to the making and walking—assembling a series of linked piecescalled Which Walks. This is where the love comes in. (“PROLOGUE”)

Thelatest from Northern California poet, editor and writer Laura Moriarty is thepoetry title

Which Walks

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), a bookthat follows on the heels of numerous prior titles such as

Verne &Lemurian Objects

(Mindmade, 2017),

The Fugitive Notebook

(CouchPress, 2014 ),

Who That Divines

(Nightboat Books, 2014), A Semblance:Selected and New Poems, 1975-2007 (Omnidawn, 2007),

A Tonalist

(Nightboat Books, 2010),

Personal Volcano

(Nightboat Books, 2019) andthe novel Ultravioleta (Atelos, 2006). Composed during the Covid-19pandemic, Which Walks presents itself as a book on walking and being, andbeing present within an unprecedented global event. “reaching back / to owneddevices,” the opening walk offers, “feel free, imaginary, / and tactile as theshudder // of daily acquisition, / domestic, time-bound, // vexed by practitioners,/ whose practice // like ours, / a consummation, // is thrown up and out / asthe poison // presence of each entrance / of nonlife into life [.]”

Thelatest from Northern California poet, editor and writer Laura Moriarty is thepoetry title

Which Walks

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), a bookthat follows on the heels of numerous prior titles such as

Verne &Lemurian Objects

(Mindmade, 2017),

The Fugitive Notebook

(CouchPress, 2014 ),

Who That Divines

(Nightboat Books, 2014), A Semblance:Selected and New Poems, 1975-2007 (Omnidawn, 2007),

A Tonalist

(Nightboat Books, 2010),

Personal Volcano

(Nightboat Books, 2019) andthe novel Ultravioleta (Atelos, 2006). Composed during the Covid-19pandemic, Which Walks presents itself as a book on walking and being, andbeing present within an unprecedented global event. “reaching back / to owneddevices,” the opening walk offers, “feel free, imaginary, / and tactile as theshudder // of daily acquisition, / domestic, time-bound, // vexed by practitioners,/ whose practice // like ours, / a consummation, // is thrown up and out / asthe poison // presence of each entrance / of nonlife into life [.]” Ithas been interesting across the past few years to see the variety, volume andintimacy of literary responses to the Covid-era, a flood of eventual titles weall knew was coming, including British writer Zadie Smith’s Intimations: SixEssays (Penguin Books, 2020), Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov’s il virus(Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], Barcelona-basedAmerican poet Edward Smallfield’s a journal of the plague year(above/ground press, 2021), Toronto poet Nick Power’s chapbook ordinaryclothes: a Tao in a Time of Covid (Toronto ON: Gesture Press, 2020) [see my review of such here], Tacoma, Washington poet Rick Barot’s chapbook Duringthe Pandemic (Charlottesville VA: Albion Books, 2020) [see my review of such here] and American/Canadian writer Lisa Fishman’s One Big Time(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2025) [see my review of such here], not tomention my own pandemic-suite of essays, essays in the face of uncertainties(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2022). Each title, in their own individual ways,working amid and between the two poles of anxiety and calm, navigating thetreacherous and uncertain waters of a once-in-a-century global pandemic. ThroughMoriarty, as her thirteenth walk offers: “appears in the thickets / whosesteady readiness // measures the commotion / it is impossible not to feel // aswhen ‘bacteria don’t know / they’re bacteria’ but do know // they’re real asmental constructs / allow us (me) to execute [.]”

Moriartycomposes forty-six pieces, “Which Walks,” set in a variety of untitled section-clusters,each of which hold between a series of short, self-contained pieces, from theopening “prologue” to “symmetry,” “inevitably,” “thefallen world,” “the case,” “slant step,” “future present”and “epilogue.” If the “Which Walk” pieces are composed within theimmediate, offering poems of attention and grounding, these other pieces providelarger context, even counterpoint. These interspersed pieces act like linksbetween sections, or perhaps the forest for the individual trees. As she writesto begin “the case”:

The present is blurred orperhaps smeared across the page. Filled with desire. She lives by the seasonswhose perspective is never quite right. The pictures behind her eyes emerge. Theone of her face, the other of a place she was in, the objects there, the light.Each one many times. She longs for the cafes of her youth but prefers thetables, tables, and trails of the moment. The work. Its blots and curves. Unexpectedevidence of everything. “I get stronger as I get older,” she wrote as a youngwoman. “But never strong enough.”

The case stays open. She reviewsher options, asking herself again what is true as she often used to do. Despitedelusions and obsessions, she knew it then. Knows it now. She recognizes thisas her main skill. Figuring it out, she moves on through

Thisis a book of attention, of poems composed across a meditative, thinking space,set purposefully and perpetually in the present moment; a book of and around time,both the movement of such and its seeming immobility, a continuous present,offering echoes, even ripples, of time as articulated as well by American poetStefania Heim’s second full-length collection, Hour Book (Boise ID:Ahsahta Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] or Pacific Northwest poetEndi Bogue Hartigan’s oh orchid o’clock (Omnidawn, 2023) [see my review of such here] or, more specifically, New York City poet Brenda Coultas’ TheWriting of an Hour (Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. “(we) submit,” Moriarty writes, as part of “WHICH WALK 6,”subtitled “problem of reversable time,” “to the reversable fortunes //of muscle memory and the / illusive person in the poem // including types ofknowing as when // The Land That Time Forgot / or trip into symbolicspace [.]” There is something of the fact of the author’s walks and the walkingsimply the mechanism through which time is explored (which is why I’m notoffering a whole list of walking titles, by the way, from Meredith Quartermainto Stacy Szymaszek to Stephen Cain to Cole Swensen to Mark Goodwin). Covid-19 lockdowns,especially across those first unknown weeks that stretched into months, aperpetual and ongoing timelessness, one that fell into a completely uniquegenerational cultural moment. As her prologue suggests, Moriarty uses thisperiod to attempt to find something grounding: “She zooms, and occasionallywalks, with close friends and family. They keep each other alive. She continuesto work.” She continued to work, even working to return to those poets that originallyprompted her writing and thinking, a really fascinating project of returning toone’s literary roots during a period of such deep and continuous uncertainty:

All of it—walking, writing, assembling, time—seems like asingle practice involving lines. Eventually, drawing is added to assembling. Thelines of what she now sees is a long poem are written in relation to her artspractice, to her own precarity, and to that of her loved ones, which, terrifyingly,seems to include everyone. She rereads the long poems of her youth by H.D.,Williams, and Zukofsky, also rereading Duncan, Brathwaite, Howe, Dahlen,DuPlessis, M. NourBese Philip. She gets all the way through Nate Mackay’s DoubleTrio and then starts back in at the beginning. She feels at the beginningof something herself, though she has just turned seventy.

Thetone and tenor of Moriarty’s Which Walks reminds me that, in his novel WhyMust a Black Writer Write About Sex? (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1994),Haitian-Canadian writer Dany Laferrière wrote that he wrote his first book, publishedin English as How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired (CoachHouse Press, 1987), “to save his life.” Perhaps Moriarty’s situation throughthe onset of pandemic might not have been as dire, but it was also impossible forher to know for certain, providing this collection a way through which shemight have worked the same as Laferrière, allowing her to articulate herpresent and remain grounded, through whatever other uncertainties swirled.

WHICH WALK 31

varieties of which

“Oh, that I could fly…”

—William James

as charms of finches,diaries

of doves, and otheravians

hover, humming down into,

hunger, delight, and desire

having gone as oneself

around, finding who orwhat

holds the breast pressedby

feral prayer into foldsof

the heart’s featheredweather’s

beating declaration ofbeing

free and aware of theheft

of iridescence in thevery air

followed by day’s waryinsight

into staying high whileabiding

being equivalent to notdying

which is, in turn andtime,

the same as flying

May 20, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kevin Stebner

Kevin Stebner is an artist, poet and musician. He produces visual art using old videogame gear, and produces music and soundtracking with his chiptune project GreyScreen, post-hardcore in his band Fulfilment, as well as alt-country in the band Cold Water. Stebner has published a number of typewriter visual poems and other concrete work in chapbooks, including Timglaset, The Blasted Tree, No Press, above/ground, among others. and has recently published two books,

Game Genie Poems

, a collection of lipogram poems written in a Nintendo Game Genie from The Blasted Tree, and

Inherent

, a collection of 100 letraset concrete poems from Assembly Press. He is also the proprietor of Calgary’s best bookstore that’s in a shed, Shed Books. Stebner lives in Calgary, Alberta. kevinstebner.com

Kevin Stebner is an artist, poet and musician. He produces visual art using old videogame gear, and produces music and soundtracking with his chiptune project GreyScreen, post-hardcore in his band Fulfilment, as well as alt-country in the band Cold Water. Stebner has published a number of typewriter visual poems and other concrete work in chapbooks, including Timglaset, The Blasted Tree, No Press, above/ground, among others. and has recently published two books,

Game Genie Poems

, a collection of lipogram poems written in a Nintendo Game Genie from The Blasted Tree, and

Inherent

, a collection of 100 letraset concrete poems from Assembly Press. He is also the proprietor of Calgary’s best bookstore that’s in a shed, Shed Books. Stebner lives in Calgary, Alberta. kevinstebner.com1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I'm trying to even think of what I would consider "the first" - and I honestly can't even place it. I simply see what I do as a lineage of artistic output. In terms of the literary, this was a big year for me, publishing two major works with two incredible presses: Game Genie Poems with The Blasted Tree and Inherent with Assembly Press. To be perfectly honest, the difference in feeling comes from the external, that these projects found such loving and caring homes, that there's been such an overwhelming response to them from their readership. For one so used to indifference (and that sentiment is a universal for the creative, I know, but, boy, it always feels like you're the only one) it's really gratifying to have these books doing what they're doing.

2 - How did you come to visual poetry first, as opposed to, say, more traditional narrative forms?

I came to visual/concrete after endeavours into more traditional, prose writing. But after a long hiatus of leaving that type of writing aside (my creative endeavours largely focused on bands and music, community projects, installation art) - but coming through the pandemic, it gave me the time to work on longer-form projects. So out of it came a novel, a music album of Kraut inspired work, and a swath of concrete poems (typewritten and letraset work). I've spoken of this at length, but I don't see myself as a writer per se, I am a multidisciplinary artist, and that artistic endeavour can move into any realm it so wishes, which can develop into novels, poetics, concrete poetics, art curation, wrestling trivia, various genres of music, and so on. It can manifest in any number of things, but this variance of interest forms the variance output.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm a many projects, many bands, many books on the go at any time kind of person. In a way, I do my best to simply plug away at projects, not thinking about the end, until at some point, that end arises. Thinking about something taking too long, thinking about what it needs to look like, those factors are already a stress on what should ultimately be a joy: creation! The question seems to be dancing around the unspoken notion of "perfection" - and that word I find a debilitation.

In the case of the concrete work in INHERENT, the sheer nature of the process (letraset on paper) doesn't allow for "editing" in a major sense. The letters, once on the paper, are there and cannot be changed once down - or perhaps the editing occurs during the process of the writing itself, the slow and conscious choices that happen when composing. Especially for my concrete work, some come from notes, an inspirational mode where I need to get the idea down, but other times it flows out, letting the letters, or keystrokes, decide for themselves how they move. Once done, the editorial process consists of what to include and what to leave out, which pieces are strong enough to want to show and include. I would not say I'm a strong editor. I always attempt to present work as best as possible, but there comes a point where an edit washes away the interesting rough edges, the places where the life of a work lives. Vigour and excitement always trump professional slickness, for me. The goal is never perfection, the goal is documentation.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I tend to view things as "project" designations. So rarely would I think in larger "book" sized confines. Those might be too daunting, the scale of those might be too vast to see them doable. Within INHERENT, each "chapter title" was its own project in itself. And many of those were published on their own as their own chapbooks ("Agalma" from above/ground, "Peaceful" came out from The Blasted Tree, "Significant" from No Press). Each section was bourne for a single sheet of letraset, and so was only initially thinking about the confines as to how to use that sheet, that was the project. Only after completing a number of those was I even thinking of a "book" as a whole. Working in smaller project modes, and assembling into a larger later, was helpful. Even writing a novel, or working on an album, I would suggest mere looking at the one smaller piece as the project - let's complete this song, let's complete this story arc - and then do that a number of times, to eventually there's enough to assemble into a larger whole. I think that thinking of projects in "book" terms can be debilitating, whereas seeing it as a collection of individual pieces is a more helpful creative mode.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

In this case, releasing INHERENT, I was really confronted with how to "read" it publicly. A book of concrete poems, which purposefully eschew semantic meaning all together. This idea led to the chapbook "Extrins"which I released alongside INHERENT, in which I asked a number of poem friends (concrete and otherwise) the question as to how to read the book. Their responses were inspirational and lovely and curious (but ultimately didn't help me getting closer to "reading" them in public). For the release then, I did a sort of Q&A type events, intended more as a (not dissimilar to the Explication in the back of the book itself) invitational explanation of the work in INHERENT, offering some insights into where it came from, how to engage concrete poetics, and where it came from. In general, I wouldn't consider a reading at all when creating the work itself (so no, not part of the initial creative process at all - I would potentially go so far as to say that if you're thinking about an end audience in general, that would potentially stunt the artfulness of the work in a major way), but how to engage the work publicly becomes a NEW creative endeavor.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I'm still stewing on this one, frankly. In some ways, Inherent was attempting to be free from exerting my own control and ideas into it. Can these poems have their own voice, not an authorial one? But I wonder how possible that is. A good question that: what are the current questions? Maybe that's a theoretic concern in itself - we've said all humans can say, perhaps there's a message from the structure of typefaces and synergy that can give an insight? My newer series I'm working on I'm leaning more into titles, each being more of a piece of wishful thinking, a hope, for what these poems could embody. Putting a little more of myself, giving a little less distance. I wonder if that changes the nature of what these poems do? (I'll answer your questions with even more questions...)

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I'll stretch this to an artistic thinker in general - writer, musician, visual artist, game designer, pro wrestler, etc... The role I see is that for the artist to fight the mundanity and ubiquity of our society as a whole. And this need not be an overt political, need not be a gigantic pipe bomb of an act - they can be tiny little pieces to chip at the darkness. The creative act is a defiant act in itself, an exertion of individual ebullition. And there's a kinship in that. Even those making bad art, at the very least we have that, I'll be on board with anyone chipping away at that poison control of ubiquity.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Difficult, certainly. So much of the work I do, either being constraint based, or very process-based - essentially both being uneditable - the poems simply become what they are. There are no better synonyms, only one word can fit the confines, or once a typewriter keystroke is made, or letraset put to paper, there is no going back. The only real edit sometimes is to cut the whole poem or not. Through my process, though, I tend to self edit. Make more than you need and keep the cream. Make 10 , keep the best 7 or 8. That usually allows me to end up presenting the best of the bunch.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best piece of advice comes from (one of) the best songs of all time, "Academy Fight Song" by Mission of Burma, the penultimate line of the song being "I'm not judging you, I'm judging me" - to me, this has meant to that the outside world is always going to have something to say, a culture of poison is going to constantly be in your ear, telling you you're not good enough, holding you to some unattainable benchmark, a comparison to another's success. Whereas, you just simply put it on yourself, the little bit you can control, holding yourself to your own standard, holding yourself accountable to your own fabric. I may not always succeed, but that change of focus on my little corner, on me and what little artistic output I can accomplish, that focus is the best thing I've found to keep the bitterness at bay.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try (and the advice I give to others, is) to do one creative thing every day. This can manifest as a written poem, and concrete poem or two, writing a song, writing a chapter in a book. Those are obvious examples. But it could also be something as small as writing down one good line in my notebook, finding a chord change to steal, making a mix tape, researching typefaces, sending mail to pals, stapling zines, reading something you'll use later... It's about never making your art a chore, or an obligation, but something that remains exciting, something that's responsive to inspiration and the muses, something that's still joyful when you sit down to do it. What you make doesn't have to be grandiose, it can be minorly incremental, and that's valid.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I've spoken on this before in "Make a Thing" - my zine of encouragement to friend who are making art in general. But for me, I've found is that getting stalled on projects and writer-block cannot be controlled. The muse moves as she likes and she cannot be forced. The solution then is to have MANY projects on the go. When you're stuck on one, pick up another. I don't know where this novel is going, I can't find a chorus to this song, etc. Move on to something else and come back to it. As long as you're exerting that creative muscle in some manner, it's staying active. This will inevitably leave room for the muse to return, giving you time to find that tidbit that reinspires the project from before.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

n/a

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

(Related aside: I discovered McFadden as a young teenager while I was working as a Page at the Red Deer Public Library. I had shelved a copy of (the brilliantly designed and ever charming) A Trip Around Lake Erie, was wildly taken with it, and I've been studying and collecting him ever since. I'm only missing a few titles. He remains my favourite Canadian "writer" writer). Though, I'll disagree with the man here, mostly in it's small limits - I'm very much a proponent of the "if you're an artist you make art" mind, and that to limit oneself to one mode of art is a stunt on oneself and one's artistic output. Art comes from Art, gotta go much wider. Writing is one way it manifests, certainly. And all that to say I am collector scum, eater or media, student of culture, high and low alike, - Yo La Tengo's kraut-like chooglers, Lungfish and Daniel Higgs' poetic esotericism, Kenny Omega's pro-wrestling matches, cassette culture, circuit bending. Ultimately as a punk, someone involved in DIY and hardcore, and all that surrounds it, that mindset remains the biggest influence in my work, and especially in how I approach it, what's behind it, the ethics of it. Art comes from art. The net is wide.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Why are these exclusive? I write, and do something else!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;