Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 24

February 27, 2025

Lesley Wheeler, Mycocosmic

Garden State

A man in a suit approachedand touched my arm.

Would I pose in front ofthe merry-go-round?

I was thirteen, free foran hour in the middle

of Paramus Park Mall, inAmerica. I was America.

The man was leading atour; the tourists spoke

no English. My English mothersaid, Your sister

is beautiful, but you arereasonably attractive.

She chose my clothes,that day a blouse abuzz

with flowers, a pinkpleated skirt. Yes, I said,

and sat on the bench. Everybodysmiled. My hair

curled like orchidpetals. A carousel horse whispered,

Why would they pointtheir cameras at you?

As if you were pretty. This will bea story, I replied.

Of cold glass eyes thatsaw the bloom in me.

Thesixth full-length poetry title by Lexington, Virginia poet Lesley Wheeler, andthe first I’ve seen, is

Mycocosmic

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2025),a collection that, at least on the surface, echoes Toronto poet Jay MillAr’s secondfull-length collection, Mycological Studies (Toronto ON: Coach HouseBooks, 2002) or the more recent full-length debut by Queens, New York-basedpoet Amanda Monti, Mycelial Person (Milwaukee WI: Vegetarian AlcoholicPoetry, 2021) [see my review of such here] for their book-length lyric focus onand around the mushroom. Whereas MillAr’s poems emerged out of direct fieldwork, akin to Lorine Niedecker’s Lake Superior [see my review of the more recent reissue of Niedecker’s poem here], and Monti approached the physicalinterlay of mushroom interconnectivity through the long poem, Wheeler embracesthe mushroom-as-metaphor, offering an underlay of strands that connect togetherher compact first-person lyrics. Wheeler writes of family stories, motherhood,the female body, agency and childhood through first-person observations, seekingclarification through the minutae of all that connects, including to her and herimmediate landscape. “Meanwhile my sister,” she offers, as part of the extendedsequence “Map Projections,” “marooned. // It’s as vivid to me as ahistory book.”

Thesixth full-length poetry title by Lexington, Virginia poet Lesley Wheeler, andthe first I’ve seen, is

Mycocosmic

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2025),a collection that, at least on the surface, echoes Toronto poet Jay MillAr’s secondfull-length collection, Mycological Studies (Toronto ON: Coach HouseBooks, 2002) or the more recent full-length debut by Queens, New York-basedpoet Amanda Monti, Mycelial Person (Milwaukee WI: Vegetarian AlcoholicPoetry, 2021) [see my review of such here] for their book-length lyric focus onand around the mushroom. Whereas MillAr’s poems emerged out of direct fieldwork, akin to Lorine Niedecker’s Lake Superior [see my review of the more recent reissue of Niedecker’s poem here], and Monti approached the physicalinterlay of mushroom interconnectivity through the long poem, Wheeler embracesthe mushroom-as-metaphor, offering an underlay of strands that connect togetherher compact first-person lyrics. Wheeler writes of family stories, motherhood,the female body, agency and childhood through first-person observations, seekingclarification through the minutae of all that connects, including to her and herimmediate landscape. “Meanwhile my sister,” she offers, as part of the extendedsequence “Map Projections,” “marooned. // It’s as vivid to me as ahistory book.”Aswell, Wheeler offers a textual underlay, a separate thread of lyric that runsacross the bottom of each page, connecting and wrapping through and across thecollection as a whole, reminiscent of how Darren Wershler (then Darren Wershler-Henry)ran a similar thread across his own second collection, the tapeworm foundry, or the dangerous prevalence of imagination (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2000) (I’msure there are other examples as well). Wheeler plays her thread as a secondarybut interconnected narrative, rolling and strolling across “Some commensaldecomposers are infamous for other / kinds of magic / spirit-work: soothing wrath& grief in humans, disintegrating toxic feelings. / Researchers describe movementof feelings from separateness to / interconnectedness… / catharsis…forgiveness.”

“Peopleradiate light they cannot see.” Wheeler writes, to open the poem “Particle-Wave,”“The subatomic universe blazes with chances.” Across a sequence offinely-honed lyrics, Wheeler writes of what connects and what falls free, ofwhat holds together and what isn’t possible.

February 26, 2025

Farah Ghafoor, Shadow Price

But what do I know ofsuffering?

This summer, we pickedwhite blooms to last a week

in our crystal vases.Their siblings flourished safely

into berries and figs,wild as dusk.

We feasted, calling themgifts.

Even the earth is apresent

if we echo it loudlyenough.

Even time can serve you—

decorated in fruit andforest is, after all,

the first museum oflooted treasure.

Inside our mouth lay theartist,

the wasp, which, too, waseaten

by its masterpiece. (“TheDream-Eaters”)

Award-winning Toronto-based poet Farah Ghafoor’s full-length debut is

Shadow Price

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2025), a collection that wraps a first-person lyric aroundtemporality, death, capitalism and colonialism, and the dangers of not knowingor understanding history. “The Present is reminded of its bones only whenbroken,” she writes, as part of “Natural History Museum,” “and then the Futureis considered, its supposed desires / and plans. The Future, for whom the dooris always open, / a sweet wind blowing in petals and leaves, sticks andfeathers. / The same doorway through which the Present passes, / and forgetswhat it was doing, its reasons why.” The movement and evolution of time is athread running through Ghafoor’s poems, articulating how it moves but in onedirection, however far one looks back. “I’ve been lying for a long time,” sheoffers, to open “The Jungle Book: Epilogue,” “so let me tell you a story. /Despite the bravado of the dog quaking before the wall, / we can never go backto who we were.”

Award-winning Toronto-based poet Farah Ghafoor’s full-length debut is

Shadow Price

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2025), a collection that wraps a first-person lyric aroundtemporality, death, capitalism and colonialism, and the dangers of not knowingor understanding history. “The Present is reminded of its bones only whenbroken,” she writes, as part of “Natural History Museum,” “and then the Futureis considered, its supposed desires / and plans. The Future, for whom the dooris always open, / a sweet wind blowing in petals and leaves, sticks andfeathers. / The same doorway through which the Present passes, / and forgetswhat it was doing, its reasons why.” The movement and evolution of time is athread running through Ghafoor’s poems, articulating how it moves but in onedirection, however far one looks back. “I’ve been lying for a long time,” sheoffers, to open “The Jungle Book: Epilogue,” “so let me tell you a story. /Despite the bravado of the dog quaking before the wall, / we can never go backto who we were.”Setin five sections—“SHADOW PRICE,” “TIME,” “THE LAST POET IN THE WORLD,” “THEPLOT” and “THE GARDEN”—Ghafoor’s expansive and epic lyrics offer shimmeringnarratives, flipping between the present and the past, the old and the new,articulating time as something physical, something that can be touched, held. Ghafooris a natural storyteller, and her lyrics offer the temperament of the ancientseer, able to discern what is long behind and ahead, all that is hidden and allthat is obvious; what others simply refuse to see, if only they’d listen. “Toobtain my severance package,” she offers, as part of the extended lyricnarrative of “The Whale,” “I will be required / to hold my breath until furthernotice. / Of course, I can barely register all of this / without the auralsupport that my insurance did not cover.” She weaves such marvellous andmagical tales, such gestures. “They have all the time in the world,” shewrites, as part of “The Jungle Book: Epilogue,” “but the story must end, as allstories do.” This is an absolutely solid debut.

February 25, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Aaron Burch

Aaron Burch

is the author of the essay collection,

A Kind of In-Between

; the novel,

Year of the Buffalo

; the memoir/literary analysis

Stephen King’s The Body

; and the short story collection,

Backswing

. He edited the craft anthology

How to Write a Novel: An Anthology of 20 Craft Essays About Writing, None of Which Ever Mention Writing

, and is currently the editor of the journals

Short Story, Long

and

HAD

.

Aaron Burch

is the author of the essay collection,

A Kind of In-Between

; the novel,

Year of the Buffalo

; the memoir/literary analysis

Stephen King’s The Body

; and the short story collection,

Backswing

. He edited the craft anthology

How to Write a Novel: An Anthology of 20 Craft Essays About Writing, None of Which Ever Mention Writing

, and is currently the editor of the journals

Short Story, Long

and

HAD

. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I'm not sure. Feels true both that it changed my life in massive ways and also not at all? On a basic level, it feels validating. Like someone cares, like pursuing this is worth it. I think my most recent work feels even more me than anything that came before it. Like I've, to some degree, found my voice. I'm more confident as a writer, and also just as a person, and I think all of that shines through in more confident prose too. It's probably more earnest and more open-hearted, maybe even more fascinated by my obsessions than ever — nostalgia, friendship, growing up, storytelling.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Fiction is just always what felt most interesting to me. I write nonfiction, and a little poetry, and read some of those too, but fiction is generally what I want to read, what most excites me. When I first started reading for pleasure during college and then as I graduated, it was novels — Fight Club , The Beach ... and then Kavalier and Clay , The Corrections , Geek Love ... — and from there I found McSweeney's and that was all the stuff that just lit up my brain and felt exciting and made me want to read more and mroe, and also write.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Everything feels a little different. I wrote a new story over winter break and it came out pretty fast and the first draft wasn't that different from the published version. But I'd been thinking about it for weeks, rolling it over and over and over in my brain. I was busy with classes and I'd told myself I was taking the semester "off" from writing, mostly so I wouldn't feel guilty if/when I didn't while busy, but also to kind of replenish the tank, as it were. And I held myself to it, which meant once my classes finished, this story just spilled out of me pretty fast. It took a couple more drafts of moving pieces around and tightening some language and a few deletions and additions, but it was largely there.

On the other end of that spectrum is a longer project like a novel. I finished a novel last summer and have been thinking about and wanting to start a new one (but was giving myself the semester off!). I have this novel that I started a few years ago but then got overwhelmed with and busy with other stuff. So I've returned to that, and what I thought was "a few years ago" was actually 2017, and new writing is going well, but I can't imagine having a draft done sooner than next summer, and could be way longer than that, and so by then it will have been "in-process" in one way or another for almost a decade??

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Again, it's a little all over the place. With a novel, I normally know it's a novel from the beginning. With stories, I'm usually just writing them here and there and then at some point they start to coalesce into a "book." With my essay collection, A Kind of In-Between, it is all personal essays, mostly short-shorts. I don't think I ever thought those would make up or even be included in a book. They felt like fun little off-shoots as breaks from or when I was getting frustrated with my novel. I really really love everything Autofiction is doing and I love that they are usually these short, tight, fun books and so In-Between kinda happened by accident, with me just wanting to work with Michael Wheaton and Autofocus. I looked around and had a lot more of these short-shorts than I'd realized, and so I just sent him all this stuff and went, "Is there a book here?" There wasn't — not quite, not yet, lol — but he helped me find one.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings! I don't think they're part of my creative process really though. I do think a lot of what I'm trying to do, in both fiction and non-, is for the writing to sound like you're being told a story, and so that usually goes well for doing readings but it starts from wanting to capture that on the page.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

With nonfiction, it is often something pretty explicit and specific to the essay — Why did I do that? Why did I respond the way I did? Why do I keep thinking about this? With fiction, there's probably versions of those same questions, though they're much more subconscious. I rarely ask it consciously, but an underlying question that I think is often driving me is how to lean into and convey this fascination with and tendency toward nostalgia that I have, in new and interesting ways. How can I complicate it, how can I make it interesting and engaging, and not just fall into the trap of lazy, one-dimensional sentimentality.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oh, I don't know. This isn't something I think or worry about. My role is to write. And to promote and encourage and champion writers and writing I love. The larger culture isn't really my business.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. I love it. I love working with an editor who reads a work excitedly and deeply and curiously. One of my favorite parts of writing is working with an editor and having them push a piece to get even better. (And, being an editor, when I can help a writer push a piece to get even better.)

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Hm. I don't too much think of writing in terms of advice. That said, there's this George Saunders essay, "Rise, Baby, Rise," that I love a lot. There are two titled subsections: “A Story Is Made of Things that Fling Our Little Car Forward” & “Ending is Stopping Without Sucking.” That's kinda everything there is right there!

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to essays to memoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

It's felt pretty natural! I think I moved into nonfiction largely because that's mostly what I teach. One of my most common classes I teach now is an intro cnf class, The Art of the Essay, though my teaching load used to be mostly, and often entirely, comp. But I taught a personal narrative essay in that class, and after doing that for semesters and years, I got inspired. By what my students were writing, and by the readings I was assigning and our discussions of them, and also just the way that I taught them. At some point, I think some version of "I do a pretty good job teaching these, I should try to take some of my own lessons and advice and write them."

My fiction often starts with something that happened to me, something I've observed, something I'm thinking about. And then the process, and the joy, is playing these games of "what if" and letting myself extrapolate and fictionalize and really take it from there. When I first started writing essays, I would have these moments or memories or whatever from my life and I would be unsure if it felt like something usable for fiction or non. But the more I wrote both, the more it started to just feel natural and instinctual.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have much of a routine. With teaching, it's pretty catch-as-catch-can. During the summer, I do often try to write every morning, more or less first thing, usually for anywhere from 2-4 hours. Five days a week feels "right." But that is ideal, and few things ever are. I've had moments of "write every day" practice, but those probably feel more the exception than the rule. This semester, I have classes Monday-Thursday, and it is only a couple weeks in, but I've so far designated Fridays as writing days. I go to a coffeeshop, write longhand for a couple hours. On the one hand, one day a week feels so minimal. On the other hand, every little bit counts, and any kind of consistency is better than nothing! If I can keep it up, I should have as little as a quarter, and maybe as much as half, of a new novel drafted! Which would then be an incredible headstart to take into summer.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Read, read, read. Live life. Do stuff. Read some more.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Rain on concrete.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

EVERYTHING influences me. Nature, music, visual art, TV and movies, being active. I find just being a human in the world incredibly influential to creating art. I go see live music and some part of me thinks, "How do I translate this — this singer's growl, this lighting setup, this feeling of being in the audience... — to the page?"

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Feels almost caricature-like, but Jesus' Son is incredibly important for me, and the book I most often return to for inspiration. In general, everything I read becomes pretty important to my work. I also spend a lot of time and energy with various editorial work — HAD and Short Story, Long, specifically now. I love reading submissions and getting excited about and accepting work and working with writers.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I don't have any specific goals, to be honest. That said, a kinda joke-y answer that is also serious: get an agent, sell a book to a bigger press, make some money from writing, be read more people, win major awards, be championed as a great writer... all that shit, lol.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I'd love to say something fancy and cool like movie director, or even actor, though those never actually felt like "real" jobs. That said, "writer" never really did either... and it still isn't! (Not in the paying any bills, anyway.)

If I hadn't become a writer, I bet I'd just have some kind of manager job at, like, a book printer or something. Which is where I worked before I went back to school for my MFA. But even that is book related, as is a bookstore, which is the other thing that jumped to mind.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don't know that I ever knew it about myself but I think I always liked telling stories and being something of a storyteller. Entertaining people, holding the attention of an audience, making people laugh. And then in college, I discovered these novels, and then lit journals and short stories, and it all just immediately felt exciting and like something I wanted to do and be involved with, and then when I started, it just felt... right. And as I've moved through life, nothing else really quite has.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I've been raving about this book a lot on social media the last few weeks, but I loved Amy Stuber's Sad Grownups. I'm only about 1/4 of the way into it, but Ben Shattuck's story collection The History of Sound is totally knocking me out and I foresee raving about it for a long time to come. And earlier this year I read Bright Lights, Big City and was surprised just how much I loved it.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm in the beginning stages of a genre-y novel that is a contemporary riff on the Jacob and Esau story from the Bible, set in 07/08.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 24, 2025

Lisa Fishman, One Big Time

Two weeks is better thanone week

which reminds me

this is quarantine, bylaw

staying in place

14 days

Border Control will callevery day

they said, but haven’t yet

I make a list

two moose one loon thesingle

constant chipmunk

multiple birds

no boats except a metalrow

& scruffy kayak

cloud sky

temptation

to plainest words (“July10-13”)

I’mcharmed by duel American/Canadian writer Lisa Fishman’s most recent title, thecompact and Covid-era

One Big Time

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books,2025), following her debut short story collection,

World Naked Bike Ride: Stories

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here],and a handful of prior poetry titles including

Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition

(Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here]. One BigTime is composed as a kind of lyric sketchbook—less a density than an exactnessand easy precision—across eight small temporal poem-captures. The table ofcontents for the collection, titled “TABLE OF DAYS, 2020,” lists her eightlyric poem-sections as “July 10-13,” “July 14,” “July 15,” “July 16-18,” “July19,” “July 20,” “July 21-22” and “July 23-24.” While the poems offer an immediacyof moments, sketches and relays, the framing sets this firmly as a pandemicresponse, and a title that suggests the uniformity across that time, the perpetual,endless now of timeless space that occurred within lockdown. “you could justsay / not anything / in the forest / under hemlock,” the opening poem begins, “waterbeinggoing by // meant to write waterbody // but it came out waterbeing / undertreebody [.]”

I’mcharmed by duel American/Canadian writer Lisa Fishman’s most recent title, thecompact and Covid-era

One Big Time

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books,2025), following her debut short story collection,

World Naked Bike Ride: Stories

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here],and a handful of prior poetry titles including

Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition

(Wave Books, 2020) [see my review of such here]. One BigTime is composed as a kind of lyric sketchbook—less a density than an exactnessand easy precision—across eight small temporal poem-captures. The table ofcontents for the collection, titled “TABLE OF DAYS, 2020,” lists her eightlyric poem-sections as “July 10-13,” “July 14,” “July 15,” “July 16-18,” “July19,” “July 20,” “July 21-22” and “July 23-24.” While the poems offer an immediacyof moments, sketches and relays, the framing sets this firmly as a pandemicresponse, and a title that suggests the uniformity across that time, the perpetual,endless now of timeless space that occurred within lockdown. “you could justsay / not anything / in the forest / under hemlock,” the opening poem begins, “waterbeinggoing by // meant to write waterbody // but it came out waterbeing / undertreebody [.]”Theimmediacy of Covid-era responses of titles such as British writer Zadie Smith’sIntimations: Six Essays (Penguin Books, 2020), Toronto poet LillianNećakov’s il virus (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], Barcelona-based American poet Edward Smallfield’s a journal ofthe plague year (above/ground press, 2021), Toronto poet Nick Power’schapbook ordinary clothes: a Tao in a Time of Covid (Toronto ON: GesturePress, 2020) [see my review of such here] and Tacoma, Washington poet RickBarot’s chapbook During the Pandemic (Charlottesville VA: Albion Books,2020) [see my review of such here], not to mention my own pandemic-suite ofessays, essays in the face of uncertainties (Toronto ON: MansfieldPress, 2022), composed across lockdown’s first hundred days, find new ground inFishman’s lyrics. There’s a calm to this collection, even with the framing, thebackground, of uncertainty across that first Covid-era summer. There’s also somethingquite graceful to the subtleties of a smaller collection—the poems themselvestake up but thirty of the fifty-six pages of this published book, allowing fora great deal of open space, which I very much appreciate here, and seems a smartand deliberate design-response to the requirements of the poems—one fully awareof the lyric geographies she moves through. “The river Niedecker / wrote ofminerals / comprising blood / I think she said we’re made of / rock,” shewrites, as part of “July 20,” “she of the Rock / River / but I think she saidthat / near Lake Superior [.]” The immediacy of Fishman’s notes providesomething far quieter, more immediate and localized. Fishman offers somethingintimate, and detailed, through her sketchnotes from the landscape of a borrowedlakeside cabin, somewhere on the Ontario side of the border, syllables across adeliberate wish to retreat and refocus, in part through the very act of writing—“Presentlocation / for nine more days: / up hwy 129 / north of Thessalon / Ontario //North of U.S. / Undone States”—where she holds to solitude, and an attempt, asense, of grounding calm. “and down there is the lake / full of fish / andthere is no reason / to stop writing [.]” Or, elsewhere, as she offers: “Wherethe lake cuts through the forest it does not / show you.” she remarks. “Goaround.”

5:30 a.m.

Morning star and Crescentmoon

in dusky light (orange redpurple)

an hour later, light’sbright yellow

then silvery yellow

then clear or no color,transparent

light

A novel confused me justthis year

bc she was talking aboutdusk

first thing in the morning,at dawn

so I looked into it andsure enough

dusk is really

a quality of light, not atime of day

(light with colors)

& yesterday “at dusk”

the dusky light was blue

I notice not beingtempted

to say so what (“July 14”)

February 23, 2025

Summer Brenner, Dust

I’mappreciating the ease of San Francisco writer Summer Brenner’s prose throughher recent memoir, Dust (New York NY: Spuyten Duyvil, 2024), a book exploringher upbringing and family circumstances: from her father’s distraction, hermother’s deflections and entitlements, and her brother’s difficulties andenduring sweetness. In his blurb for the collection, James Nolan writes howBrenner “captures the tumultuous fifties and sixties of a genteel Jewish familyin Atlanta, with the South’s oppressive segregation and anti-Semitism. Thefamily drama is fraught: the brother is a schizophrenic, the mother is aGucci-clad Medusa, and the father a suicide.” The prose is engaged, engaging;offering the distance of time but an immediacy of enormously rich detail. Thelanguage seems uncomplicated, but is crafted, riveting. As she begins the thirdchapter, “The Toy Store”: “In summer the daylight is nearly white. Its color isdulled by the flat, hot, heavy air. The sky and sun are buried in a white vaporthat hangs like a starched sheet. The thick air presses down on everything. Thenearby objects—my red wagon, my parents’ blue car, the houses—pulse with theheat around them. From the road, the asphalt sends up zigzag waves of heat.”

I’mappreciating the ease of San Francisco writer Summer Brenner’s prose throughher recent memoir, Dust (New York NY: Spuyten Duyvil, 2024), a book exploringher upbringing and family circumstances: from her father’s distraction, hermother’s deflections and entitlements, and her brother’s difficulties andenduring sweetness. In his blurb for the collection, James Nolan writes howBrenner “captures the tumultuous fifties and sixties of a genteel Jewish familyin Atlanta, with the South’s oppressive segregation and anti-Semitism. Thefamily drama is fraught: the brother is a schizophrenic, the mother is aGucci-clad Medusa, and the father a suicide.” The prose is engaged, engaging;offering the distance of time but an immediacy of enormously rich detail. Thelanguage seems uncomplicated, but is crafted, riveting. As she begins the thirdchapter, “The Toy Store”: “In summer the daylight is nearly white. Its color isdulled by the flat, hot, heavy air. The sky and sun are buried in a white vaporthat hangs like a starched sheet. The thick air presses down on everything. Thenearby objects—my red wagon, my parents’ blue car, the houses—pulse with theheat around them. From the road, the asphalt sends up zigzag waves of heat.”“Wheneverthe KKK marches through downtown,” Brenner writes, “they pass Leb’s. Theydeliberately choose a route that passes Leb’s. They wear long white robes andcarry their hoods in their hands. They can’t hide behind their hoods. There’s alaw now that makes them show their faces.” She continues:

I know about the KKK. Iknow they burn crosses and do things that I can’t let myself imagine. I knowthey hate Jews. They hate Blacks, Catholics, and Jews. Because Daddy stands upfor the rights of Blacks, I worry they’ll come to our house. I worry they’llburn a cross in our yard.

At Leb’s our family likes to sit in a booth by thewindow. If the Klan is marching, I see them through the window. They’regrinning when they pass us. Or maybe grin is incorrect. Maybe grimaceis the correct word. I see how proud and happy they are to march. I’ve beentaught you’re only supposed to be proud of good things. I wonder if they thinkthey’re good. I wonder if it makes them happy to hate.

It is a remarkable storyof how one emerges, able to find clarity in one’s surroundings and chaos, andbe able to step outside of it, seemingly unhindered by the limitations of herparents, of her community; of where and how she grew up. How she managed toemerge as a seemingly-emotionally healthy, capable and empathetic person.Through all the chaos. Through all the bluster and anger and resentment andturmoil, capturing the detail of a time and a place and a sense of it that isdeeply compelling.

February 22, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Aaron McCollough

Aaron McCollough

is the author of seven poetry collections, most recently

Salms

(University of Iowa Press, 2024). He is also the co-publisher (with Karla Kelsey) of SplitLevel Texts.

Aaron McCollough

is the author of seven poetry collections, most recently

Salms

(University of Iowa Press, 2024). He is also the co-publisher (with Karla Kelsey) of SplitLevel Texts.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

To say my first book changed my life would feel strained. At least in the most obvious practical terms, it had little to no impact on my life. I know I had hoped it would lead me to a more concrete professional footing and therefore translate into material change in the form of income. That did not happen. Subsequent books were no more life altering in this sense. That being said, it would be very hard to overstate how much publishing that first book (or second, third, etc.) has meant to me and has meant for keeping alive that part of my life that is "being a poet." So, the first book feels now like it represented a kind of culmination of a long phase of student writing and aspiration while at the same time opening the horizon on an equally long phase of establishing myself in my own mind as a "real" writer (rather than a hobbyist, I suppose). In short, it felt fundamentally validating even if it never served me as a professional credential in the way that publications do in the academic marketplace, and it also established an expectation within me for pursuing further such validation. Twenty-two years later, the need for validation has changed a good bit, but I won't pretend it has completely gone away. I do trust my own artistic inclinations much more deeply now then I did then, confirmed in part through two decades of further reading, writing, and testing of those inclinations in the actual experience of life. Where once I hoped to leverage a livelihood out of poetry (which even then struck me as a somewhat dubious pursuit), I have long been free to let poetry's work be a sufficient end in itself. I believe this translates into something more purely in keeping with my own idiosyncratic artistic vision, which in turn feels more validating than the early accomplishments, if in a slightly different, more wholly personal way.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

The simple answer is that other forms seemed impossible to me whereas poetry did not and so I started doing it. I still don't know how people manage to write imaginative prose, even though I have many close friends who do so very well. Probing a little more deeply, I have always been drawn to the elliptical nature of even the most straightforward lyric writing. The compression and leaping of lyric figuration, as well as the blend of revealing and obscuring that serves as the lyric's engine has always made poetry feel like the most memetic of modes for experimenting with the materials of what it is to be alive. And this sort of experimentation is what I find most compelling about literature.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don't have a tidy answer for this question. Process and project for me have tended to be pretty organic and have developed at different speeds. Likewise, some poems have come quickly, some slowly, many more have foundered and been abandoned. On average, I guess I'd say most poems that have survived have appeared quickly and then been revised meaningfully but not radically over the course of a few years. As poems appear, they tend to influence the way I think about the ones that preceded them, which guides the way I revise.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For the most part I think I am an example of the former. In a couple of cases I thought I had a project-level concept in mind from the outset ( Little Ease and No Grave Can Hold My Body Down ). But, in the end, even those books ended up dictating their own path to me as I went. At most, I think I have a vague idea from the outset of what a gathering of work is going to be interested in, but I tend to learn the real nature of the interest as I'm going and as I'm finishing up.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don't love giving readings. I'm too shy for that, which means that I have to push past my shyness to perform, and pressing in that way feels inauthentic. In some ways, it feels perverse to make public the product of poetry's very solitary and private work, but that of course is a kind of contradiction, given that the meaning of publication is literally "to make public," and I've pursued publication for years. In short, I don't think readings have much to do with my writing, but I do want (for reasons I can't completely justify) to share that writing with other people. Sometimes I give readings as a result, and sometimes it goes relatively well, although it never feels quite right to me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

There definitely are. Most broadly speaking, I'd say my poetry is concerned with the place where metaphysics, ethics, memory, and psychology come together in the present moment. In practice, this has always been a kind of soteriological inquiry: of kairos and eschaton and an accounting of a new heaven and a new earth fitfully breaking into lived history, specifically history as lived out through the dot, in the great network of being, represented by my own mind-body-soul.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have always trusted the idea that artists (including writers) should pursue their own weird paths with as little distraction as possible. They belong in the wilderness, and so their role is outside of typical systems we tend to associate with ideas like "role." First, their role is to be marginal by virtue of their devotion. Secondarily, the products of that devotion may serve the culture, but that's the culture's business, not the artist's.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It has been helpful to me to have another, trusted person challenge my decisions. It hasn't always been a formal editor who has done this most helpfully, but once the wilderness work is over, I find it very valuable to get feedback from people who know my work and can see with fresh eyes.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Cut the longest swath you can for as long as you can.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I start every day early with an hour of coffee, reading, and contemplation. It sounds a little precious, but I find it makes my life much more manageable. I don't write every day, but often this beginning does lead naturally into writing, and when it does I'm always grateful.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I tend to be in agreement with David W. McFadden, as cited in question 13 below. I tend to go back to reading, always. I guess I'm less inclined than I used to be to think in terms of writing being stalled or not. I want to say that at this point I see living and writing being close enough to one another that I'm writing as long as I'm living, even if there isn't ocular proof left behind. Sooner or later there tends to be some kind of receipt, and that's gratifying, but often I feel like the work that needs to be done first needs to be done in silence. So, I don't do as much conscious looking for inspiration as I once did.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Junipers. Honeysuckle. 'Lectricshave.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The 17th-Century English poets continue to be very important to me in both my work and my life. Dante has continued to figure more prominently in my imagination over the years than I expected. Rilke, Kierkegaard, Bergson, the Black Mountain poets, Ortega-y-Gasset, Deleuze, Karl Barth, Jürgen Moltmann.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Priest. Were I not a writer it's hard to imagine being at all, but writing is not my occupation. I've had many jobs, and being a writer has rarely gotten in the way.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wasn't very good at much else. Or, I seemed to have a talent for writing and less talent for other things.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great book was Septology by Jon Fosse. Last great film was Vesper by Kristina Buožytė and Bruno Samper.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I've been writing quite a bit the year since I finished the Salms manuscript. I'm not sure what all this writing might amount to, but formally these are short lyrics. They seem very quiet to me, and I'm not sure how many of them are really even really poems. I've been thinking of them of "figures," so eventually I will have to figure out what that really means.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 21, 2025

Sean Howard, overlays

PREFACE

Tidelines in &

out of print (the

only ever briefly

laid stress): cloth-

bound back-

wash. So

soon,

the

self’s

worn copy! I

don’t know: gha-

zal? haiku? rain

to snow…Just

gulls, rough

edges

I’mfascinated by Cape Breton poet Sean Howard’s latest poetry title, thedeceptively-subtle and sleek production of his wildly inventive

overlays

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2025), a book subtitled “( scored poems ),”with addendum “from Sea Run: Notes on John Thompson’s Stilt Jack, byPeter Sanger.” The poems that make up Howard’s overlays quite literally respondto the work and structure of Nova Scotia poet, prose writer and critic PeterSanger’s critical monograph on the late John Thompson’s posthumous StiltJack (Toronto ON: Anansi, 1978), a monograph originally published by XavierPress in 1986 (a “fully revised and expanded edition” appeared with Gaspereau Press in 2023). As British Columbia poet Kim Trainor writes of the first edition of Sanger’s monograph in a review on her blog back in March 2014, thebook is “a meticulous line by line commentary on Thompson’s Stilt Jack,”and Howard’s collection holds to the structure and spirit of Sanger’s shortwork while entirely dismantling the language. “Canada, still harrowing? Pen /knife (but why?),” opens the poem “IX: SCRAPES,” “scraping star- //light from stone. Keats’ cease / fire (so the world we shut // up…): negativesleave / room for the dark. // Left standing, / children’s // voices / over //the wall.”

I’mfascinated by Cape Breton poet Sean Howard’s latest poetry title, thedeceptively-subtle and sleek production of his wildly inventive

overlays

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2025), a book subtitled “( scored poems ),”with addendum “from Sea Run: Notes on John Thompson’s Stilt Jack, byPeter Sanger.” The poems that make up Howard’s overlays quite literally respondto the work and structure of Nova Scotia poet, prose writer and critic PeterSanger’s critical monograph on the late John Thompson’s posthumous StiltJack (Toronto ON: Anansi, 1978), a monograph originally published by XavierPress in 1986 (a “fully revised and expanded edition” appeared with Gaspereau Press in 2023). As British Columbia poet Kim Trainor writes of the first edition of Sanger’s monograph in a review on her blog back in March 2014, thebook is “a meticulous line by line commentary on Thompson’s Stilt Jack,”and Howard’s collection holds to the structure and spirit of Sanger’s shortwork while entirely dismantling the language. “Canada, still harrowing? Pen /knife (but why?),” opens the poem “IX: SCRAPES,” “scraping star- //light from stone. Keats’ cease / fire (so the world we shut // up…): negativesleave / room for the dark. // Left standing, / children’s // voices / over //the wall.”Onemight say that Howard’s project responding to Sanger’s text is very meta, setas an homage to an homage, a response to a response, riffing off Sanger writingon Thompson. “Key / note,” opens Howard’s “XXXV: GREENS,” “silence’s /tonic: soon, a // plenty. History’s / dead aims: as Joyce // might sway, gnaw-/ ledge is dour…(Me- // thodically, Occam cuts / the world shaving: High// Table, Apollo’s spoon / on the moon.)” The poems are precise, playfullyclipped and exact, seeking the moment within the moment, within and around theboundaries of Sanger’s own possibilities, and Thompson’s as well. Howard’spoems are precise, but packed with a density that is both wildly propulsive andaccumulative, offering a joyfully-jagged rhythm and staccato that display himclearly having an enormous amount of fun across this myriad of collaged lyrics.As the poem “BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY: SEVERAL SELVES” begins:

Blackouts: child’s-eye,searchlights…(Everywhere, sold-

iers, compulsoryfigures.) Cold War: atoms, butterflies &

wheels. (Learning class,Manchester’s grammar.) Ill-

fitting, often, sign& sound: after the storm, find-

ing language’s anchor.(On course in the

woods? Trout make themselves

clear?) A while, Dylan

Thompson: double

vision,

loose

locks.

Whereasthe notion of the response or translation is more familiar in other corners ofcontemporary (experimental, avant-garde, what have you) poetics—whether bpNichol’sTranslating Translating Apollinaire: A Preliminary Report (Milwaukee:Membrane Press, 1979), Erín Moure’s Sheep’s Vigil by a Fervent Person (asEirin Moure; Toronto ON: Anansi, 2001) or more recent book-length projectsresponding to different poetry books through her own individual poetry-length worksby American poet Laynie Browne [see my review of her latest here; see my interview with her on her ongoing projects here]—it is a form and approach lessvisible across those working more formal lyrics. One can cite poems here andthere, certainly, including the endless array of responses to Wallace Stevens’ 1917 poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” but very few in the way ofbook-length works, making this poetry title a kind of formal outlier (and anabsolutely delightful one).

Echoingthe structure of Sanger’s poem-by-poem critical response, Howard’s overlaysis structured with three opening poems—“PREFACE,” “INTRODUCTION” and “BIOGRAPHICALESSAY: SEVERAL SELVES”—prior to the body of the collection, a sectiontitled “NOTATIONS TO STILT JACK,” made up of the opening poems “EPIGRAPHS”and “THOMPSON’S PREFACE” before launching into thirty-eight Roman Numeralnumbered poems (a la Thompson’s original ghazal-sequence) to close the section withthe poem “CRITICAL ESSAY: JONAH’S ROAD.” The book then ends with Sanger’s own pieceresponding to the response of his response to John Thompson’s infamous ghazals,the short essay “NIJINSKY’S LEAP: AN AFTERWORD,” that opens:

Sean Howard invited me tocomment on his book. He suggested I might respond to his use of Sea Runas framing context for Overlays. I accepted, hoping to say somethinguseful about my intuition that prose commentary, even when as focused as thatof Sea Run, can only be penultimate in nature and can only be completewhen it is renewed in poetry. I connect that intuition with Mandelstam’s remarkin his essay “Conversation about Dante”: “a metaphor can be defined onlymetaphorically.” In other words, it takes a poem to know a poem.

Itcan’t be overstated the effect that Thompson’s original Stilt Jack hadon Canadian writing, introducing the English-language translation of the Urdustructure of the ghazal [see my review of the 2009 issue of Arc PoetryMagazine, “A Gathering of Poets for John Thompson” here], a structure furtheredas well by Phyllis Webb (I think it was Agha Shahid Ali who introduced the forminto the United States). I think it is fair to consider Thompson, and his work,beloved across elements of Canadian poetry, especially upon the east coast,making this a project not just of playful and inventive structure, but inloving homage. It is an absolutely delightful work. And, in a similar spirit,might some further critic attempt to look at the three works in tandem, or evenattempt to respond in some other, further way?

February 20, 2025

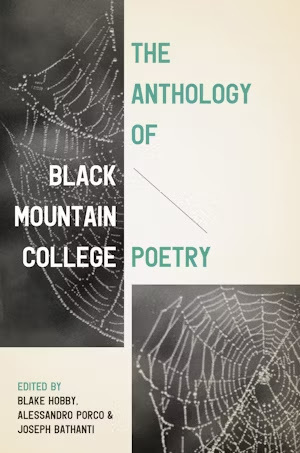

The Anthology of Black Mountain College Poetry, eds. Blake Hobby, Alessandro Porco + Joseph Bathanti,

The Anthology of Black Mountain College Poetryrecognizes and celebrates the historical importance of BMR [The BlackMountain Review] and NAP [The New American Poetry: 1945-1960]but, at the same time, aims to transcend their respective limits, providing afar more inclusive sense of the BMC experience. It does include [Paul] Goodman,[Edward] Dahlberg, and [Michael] Rumaker, as well as [Gael] Turnbull and [Irving]Layton. In addition, the anthology emphasizes the “people who were there,” toborrow from Fielding Dawson. For nearly twenty-five years, faculty, students,families, and visitors lived and learned together at Lee Hall or Lake Eden,though not necessarily in perfect harmony and not always under the easiest conditions.They hiked into the Smoky Mountains, seeking inspiration in nature’s forms;they fertilized the soil, and they milked cows; they debated poems, plays, andnovels; they enjoyed dancing on Saturday evenings, as well as the occasional romanticintrigue; they played football and softball (by all accounts, Fielding Dawsonwas an exceptional starting pitcher); they snuck out to Ma Peek’s Tavern fordrinks; and they played poker after dark, listening to the latest beboprecords. Somewhere along the way, the faculty and students also found time toproduce some of the most exhilarating poetry of the twentieth century. (AlessandroPorco, “INTRODUCTION”)

I’dbeen quite eager to get my hands on the nearly four hundred and fifty pages of

The Anthology of Black Mountain College Poetry

, edited by Blake Hobby,Alessandro Porco and Joseph Bathanti (Chapel Hill NC: The University of NorthCarolina Press, 2025). I hadn’t heard of the other two editors, but Canadianpoet, editor and critic Alessandro Porco, of course, has been been enormouslybusy over the past decade-plus down there in North Carolina, clearly focusingon archival projects, having also edited the critical edition of Jerrold Levyand Richard Negro’s Poems by Gerard Legro (Toronto ON: Book*hug Press,2016) and authored the afterword to Toronto poet Steve Venright’s The LeastYou Can Do Is Be Magnificent: Selected & New Writings (Vancouver BC: AnvilPress, 2017), as well as working on projects such as

Deportment: The Poetryof Alice Burdick, selected with an introduction by Alessandro Porco

(WaterlooON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], GaryBarwin’s For It Is a PLEASURE and a SURPRISE to Breathe: new & selectedPOEMS, edited with an Introduction by Alessandro Porco (Hamilton ON: Wolsakand Wynn, 2019) [see my review of such here] and put together the originalmanuscript for Barwin’s Scandal at the Alphorn Factory: New and SelectedShort Fiction, 2024-1984 (Picton ON: Assembly Press, 2024). And doesn’t healso produce an occasional (and very quiet) chapbook series as well?

I’dbeen quite eager to get my hands on the nearly four hundred and fifty pages of

The Anthology of Black Mountain College Poetry

, edited by Blake Hobby,Alessandro Porco and Joseph Bathanti (Chapel Hill NC: The University of NorthCarolina Press, 2025). I hadn’t heard of the other two editors, but Canadianpoet, editor and critic Alessandro Porco, of course, has been been enormouslybusy over the past decade-plus down there in North Carolina, clearly focusingon archival projects, having also edited the critical edition of Jerrold Levyand Richard Negro’s Poems by Gerard Legro (Toronto ON: Book*hug Press,2016) and authored the afterword to Toronto poet Steve Venright’s The LeastYou Can Do Is Be Magnificent: Selected & New Writings (Vancouver BC: AnvilPress, 2017), as well as working on projects such as

Deportment: The Poetryof Alice Burdick, selected with an introduction by Alessandro Porco

(WaterlooON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], GaryBarwin’s For It Is a PLEASURE and a SURPRISE to Breathe: new & selectedPOEMS, edited with an Introduction by Alessandro Porco (Hamilton ON: Wolsakand Wynn, 2019) [see my review of such here] and put together the originalmanuscript for Barwin’s Scandal at the Alphorn Factory: New and SelectedShort Fiction, 2024-1984 (Picton ON: Assembly Press, 2024). And doesn’t healso produce an occasional (and very quiet) chapbook series as well?Withnearly sixty poets represented within its pages, The Anthology of BlackMountain College Poetry is structured as an expansive portrait, one largerthan what had previously been presented around the poetries, poetics, peopleand publications around Black Mountain College, a private liberal arts collegeoriginally founded in 1933 that hosted a slew of faculty and students thatwould become highly influential across numerous arts, not purely poetry, beforeclosing in 1957. When one thinks of Black Mountain, one immediately thinks ofCharles Olson (1910-1970), Robert Creeley (1926-2005), Denise Levertov (1923-1997),Robert Duncan (1919-1988) and Joel Oppenheimer (1930-1988), of course, butthere is also May Sarton (1912-1995), John Cage (1912-1992), R. Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller (1895-1983), Jane Mayhall (1918-2009), Galway Kinnell (1927-2014), Ed Dorn (1929-1999), John Wieners (1934-2002), Paul Blackburn (1926-1971), William Bronk (1918-1999) and Larry Eigner (1927-1996) and numerous others that theeditors have included within this volume, even including two poets from this sideof the border: Gael Turnbull (1928-2004) and Irving Layton (1912-2006). The wealthof activity represented here is vast, and essays included by all three editorsoffer different perspectives upon a context for the space, the period and theparticipants, and the collection as a whole deliberately works to widen whatprior portraits have historically depicted. As editor Joseph Bathanti writes,to close his “AFTERWORD” to the collection:

It isgratifying, but also a tad jarring, to see the municipality of Black Mountainlisted in Allen’s preface along with Berkely, San Francisco, Boston, and NewYork City as hot spots for the emerging avant-garde of the period—especially whenone conceptualizes Black Mountain in the 1950s, not to mention in 1933 when thefirst pioneering students and faculty of the newly founded BMC arrived by trainin the tiny village. But in truth, what did provincial, very rural BlackMountain—the place, the locus, its geography, its ether and ethos, immuredgloriously yet invisibly in the heart of Appalachia—have in common with itsobviously more sophisticated cosmopolitan counterparts in Berkeley, SanFrancisco, Boston, and New York?

Gauging placeas inspiration, as shaping oeuvre, as the Muse incarnate, requires what infiction we call “the willing suspension of disbelief.” But nothing less than akind of willed predestined magic, true intuitive mysticism, the Muse in spades,was at play at Black Mountain during those [Charles] Olson years that produceda cadre of writers, unapologetically experimental, derivative of no one exceptperhaps one another, that would profoundly influence not only its owngeneration but generations to come. The Anthology of Black Mountain CollegePoetry champions, restores, rediscovers, uncovers, and introduces anexponentially more diverse roster than Donald Allen, clairvoyant though he was,dished up in 1960. Including more names and titles than Allen did sixty-fouryears ago, this anthology expresses the ongoing, fertile yield of BMC in theseensuing years.

AsBlake Hobby offers in his preface, it was Donald Allen who first brought thepoets of Black Mountain College to national attention through his 1960anthology The New American Poetry: 1945-1960. “To his credit,” Hobbywrites, “Allen recognized BMC as a locus of creativity and invention in thepoetic arts. He demonstrated the influence those associated with the collegehad. He also showed how the writing and thinking departed from othercollections of poetry. […] While Allen carefully selected ten figures torepresent BMC, I knew from researching and from reading poems by BMC faculty,visiting faculty, students, and affiliates during my visits to BMCM + AC [BlackMountain College Museum + Arts Center] in Asheville and to the BMC holdings inthe North Carolina Western Regional Archives in Oteen, just outside ofAsheville, that the diversity of the BMC experience transcended Allen’s group. Followingthe inspiring example set by Mary Emma Harris in her highly influential bookThe Arts and Black Mountain College, which aimed to be faithful to thehistorical record and to be inclusive, I vowed to show how BMC’s lived creed of‘democracy as a way of life’ was reflected in the poetry of the college’s faculty,visiting faculty, students and affiliates.”

Whatintrigues about this anthology, paired with its openness, is the way the bookis structured, offering a section of “FACULTY : in order of appearance,” “VISITINGFACULTY: in order of appointment,” “STUDENTS: in order of enrollment” and “AFFILIATES:who visited Black Mountain College or published in the Black Mountain Reviewby year,” as well as an appendix, listing names and biographies of three poetsthey were unable to secure the rights to include in the book itself—George Zabriskie(1918-1989), Max Finstein (1924-1982) and Edward Marshall (1932-2005)—alongsidea list of selected works, so any interested readers might attempt on their ownto garner their own completion on this project.

There’sa Frank O’Hara quote I half-recall and can’t source, of how schools areimportant, as they provide the possibility of remembering activity at all, withthe added caveat that such depictions are often woefully incomplete, recallinga core group over any larger kind of activity. Comparable “schools” wouldcertainly include The New York School, TISH, the Vehicule Poets, the Beats, the Berkeley Renaissance and the San Francisco Renaissance, the groupings of most ofthese that offer their own fluidities, and argued-upon members. The broadening presentwithin this anthology is reminiscent, somewhat, of a more expansive TISHanniversary event circa 2004 at the Vancouver Writers Festival (including asone of their readers a poet who had only appeared in the pages of thenewsletter but once), or even editor Robert McTavish’s expansive selection of A Long Continual Argument: The Selected Poems of John Newlove (Ottawa ON:Chaudiere Books, 2007) and editor/critic Cameron Anstee’s expansive selectionof The Collected Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudiere Books, 2015).

I’dbe curious, even, to hear what Toronto poet and critic Michael Boughn’s take onsuch a collection, as his own recent essay collection, Measure’s Measures:Poetry & Knowledge (Barrytown NY: Station Hill Press, 2024) [see my review of such here], was set around the central core of certain of those poetswithin The New American Poetry: 1945-1960, including Robert Duncan.Either way, this is an impressive, expansive and important collection, one withlayers of curiosity and research, enough that one could easily get lost within.

February 19, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nuala O'Connor

NualaO’Connor livesin Co. Galway, Ireland. Her poetry and fiction have been widely published,anthologised, and won many literary awards. Her sixth novel Seaborne,about Irish-born pirate Anne Bonny, is nominated for the Dublin Literary Awardand was shortlisted for Eason Novel of the Year at the 2024 An Post Irish BookAwards. Her novel NORA (New Island), about Nora Barnacle andJames Joyce, was a Top 10 historical novel in the New York Times. Shewon Irish Short Story of the Year at the 2022 An Post Irish Book Awards. Herfifth poetry collection, Menagerie, will be published by Arlen House inspring 2025. www.nualaoconnor.com

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst book (a poetry collection) cemented my commitment to the project of beinga writer. I was full of the joys, so hopeful, so (naively) sure of a steadyupward trajectory, rather sure I would make an OK living as a writer. I hadn’ta clue what that meant at the time; if I had, I probably would’ve stayed longerin the trad workplace.

Mynew poetry collection, Menagerie (Arlen House, March 2025), has the samedevotion to language, but is perhaps a little freer in spots. It’s hard to beobjective about the work. I think I am a better writer since book #1,after twenty-two years of writing/publishing.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Iwas writing poetry and fiction in tandem – I had enough work for a poetrycollection sooner.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

Istart quickly (I’m impatient) and tend to research as I go, which presents itsown issues but works for me. Drafts are like holey cardigans that eventuallyend up mended, and quite wearable, between the efforts of me, my agent, and theeditor I’m working with. Some editors are hands off, some hands on, some aregifted and hands on. It depends how many holes the cardi has, I guess.But first drafts are almost never what is published.

Yes,notes galore, I’m incessant.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Itvaries. Some things that start tiny – a spark that becomes a poem, flash, story– end up as novels because I can’t stop thinking about the character. In fact,that happens a lot e.g. with my novels Miss Emily, Becoming Belle, andNORA. I have my writerly obsessions – mother-child stories; the body;breaking love – so I tend to write across the genres on those. Others arebook-shaped from the start, novels like my WIP, a contemporary novel setbetween Ireland and Greece.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process?Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Theyare part of it – we’re expected to do them, and I also have to earn a living. I(almost) always enjoy them in the moment, but being autistic, I live on mynerves, so I’m in a constant state of anxiety, and I tend to dread everysocial/public encounter. So, the public side is genuinely challenging for me,and I rarely relish doing events, BUT, I also enjoy them, and I like meetingbookish people and talking about literary things. The Dread is one of thecentral conundrums of my life.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

Feminismhas always been central to me. Also justice. I grew up working class, so I’minterested in social standing, money, the working vs the middle class andopportunity. But I don’t think in themes or symbols as I begin a project – it’sjust about the characters and what they’re dealing with. Obviously, war, thecollapsing environment, and capitalism are upfront for all of us, and they leakonto the page.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

Thewriter just needs to write the human experience in honest, realistic, andimaginative ways. That’s all. Great language and something like a story. We’reall struggling; most of us haven’t a clue what we’re doing here, and we’re basicallyflawed and bonkers. We need to write that. Writing honestly is political, inand of itself. It’s not the writer’s job to write a palatable version of lifewith thoroughly decent players – we can pretend those people exist but theydon’t. If our work offers comfort, so be it, but each writer’s duty is tothemselves – to make the best work with the tools and understanding they have. Andnot to be a fuckwit.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Both.One always hopes to write a beautiful, breathtaking, meaningful work on thefirst go. It rarely happens. Criticism is not easy, but fresh eyes are useful. Agood editor is a gift to a writer. I’ve had brilliant experiences on some books(my last novel Seaborne, for example) and middling ones on others.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

‘Eyesopen. Heart open. Feet on the ground.’ From the wonderful English writer AndrewMiller.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toshort stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

Writingis my safe-space, my joy, my comfort. The difficulty is in brain-space andbandwidth. When I’m working on a novel, I don’t have the time or head-energyfor much else. I can break off from the novel to deal with story commissions,for example but, in novel-land, I don’t have the lovely, swirly capaciousnessneeded for poems and stories to brew naturally. So, I miss the green grass ofshorter work while engaged in long form and vice versa, often. Writers arenever happy…

Theappeal is the different momentum – the comfort blanket of the novel, the longhaul of it, versus the electric rush of completing something short.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Asan autistic person, routine is very necessary to me; I have to be at my desk by9am, five days a week, or I get a bit loopy. I stay there for about threehours, longer when I have a deadline.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Goodwriting (Elizabeth Bowen and Virginia Woolf, often; the classics; good poetry);visual art; any cultural experience – a live poetry reading. Nature walks. Thesea. Historical happenings. Inspo is everywhere.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lavender.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Visualart is the big one for me. I write a good bit of ekphrastic stuff, poems andfiction. I’ve always been an art dabbler – my family is chockers with visualartists – so I make things too. Mostly collages and cards these days. A lot ofwriters I know draw or sew or knit. Creativity is a nest – for most creatives, wehave our main branch, but we like to play with, and weave in, other seductivetwigs.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Ilike work that is tricky, dark-ish, language based, deep, empathic. I likehumour. Bowen, Joyce, Anne Enright, the Brontës,Austen, John Banville. Too many to name, really.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Writea novella. A good one.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

Iwanted to be a bus conductor or a nun, when I was a kid, neither of which wouldhave suited me 😊 Realistically: Archivist/researcher. Conservationist. Architect.Interior designer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’sthe perfect occupation for an introverted, shy, non-drinking, autistic lonerwho loves words, anthropology, and history. Previously I was a translator,librarian, and bookseller, and I worked in a theatre and a writers’ centre. Youcan see my special interest never really waned: words, words, words.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Iloved the Netherlands-set novel Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden: sharp,challenging characters, a house as the main setting (I love buildings), a foldand re-fold structure, strong sentences. Very good.

Idon’t watch many films these days, though I recently enjoyed Lonely Planetabout a writer in Morocco. I’m more of a series binger. I’ve recently loved Shetland(rugged island landscapes; great characters).

20 - What are you currently working on?

Finishingup my Greek novel. I’m also working out the plan for a memoir about autism,writing, and hope. It can be upsetting to examine past life-blunders, and seewhere I went wrong, but I’m in my mid fifties now so I care less than I used toabout what others think of me. So, onward!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 18, 2025

Ian Lockaby, Defensible Space / if a crow

if a crow—

then a black ice cubepressed

against the grain of thesun

while the afternoon mugsdrop

pattering spoils of a milk’d black coff-

-in the over grown carpets

lay a caffeinated belly bitter against

the sleep against thedamn

bright slipping away. if a crow—

remembers you,

by what:

Something growly

in the vanilla leaf—

don’t dawdle now

it’s plenty late.

I’dbeen seeing his name around for a while, so I’d been curious about New Orleans-based poet, translator and editor Ian Lockaby’s full-length debut,

DefensibleSpace / if a crow

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2024), a collection unsectioned,as a book-length stretch of clusters of shorter lyrics on and around alandscape of language, fields and shadows within the American PacificNorthwest. “cicadas hum and / mysteriously kill // songbirds—,” he writes, aspart of “Songbirds Mysteriously Dying,” “a panic / takes in the internet //birding groups / arguing over whether // to offer the birds water— // throw itin the trees / instead, they say // outside of one’s reason / is another life[.]” I’m intrigued by the spacings and pacings of these poems, how they’re heldagainst and through visual and even physical space on the page, offeringmoments, fragments, somehow held in air or breath. And through all the smoke,all the branches and trees, the repeated appearance of crows. There’s such aprecision to his lyric progressions, casual and easygoing and exact across suchwonderful pacing. “you’ve grown and used / different times—,” he writes, aspart of the second poem, “A Way to Tell,” “You’ve learned to keep // thyme witheach / of them, stacked and riveted / to your ribcage now // And every time youstand, I try to // stay still—to be / located inside of the ways I hear [.]”Or, as the poem “At Trillium Lake” begins:

I’dbeen seeing his name around for a while, so I’d been curious about New Orleans-based poet, translator and editor Ian Lockaby’s full-length debut,

DefensibleSpace / if a crow

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2024), a collection unsectioned,as a book-length stretch of clusters of shorter lyrics on and around alandscape of language, fields and shadows within the American PacificNorthwest. “cicadas hum and / mysteriously kill // songbirds—,” he writes, aspart of “Songbirds Mysteriously Dying,” “a panic / takes in the internet //birding groups / arguing over whether // to offer the birds water— // throw itin the trees / instead, they say // outside of one’s reason / is another life[.]” I’m intrigued by the spacings and pacings of these poems, how they’re heldagainst and through visual and even physical space on the page, offeringmoments, fragments, somehow held in air or breath. And through all the smoke,all the branches and trees, the repeated appearance of crows. There’s such aprecision to his lyric progressions, casual and easygoing and exact across suchwonderful pacing. “you’ve grown and used / different times—,” he writes, aspart of the second poem, “A Way to Tell,” “You’ve learned to keep // thyme witheach / of them, stacked and riveted / to your ribcage now // And every time youstand, I try to // stay still—to be / located inside of the ways I hear [.]”Or, as the poem “At Trillium Lake” begins:There is nausea on theshelves

of A.’s grandmother

the eve of it A traveler

who hasn’t been here since

she was bedded down

in asylum for softening

in the violet inconsistencies

of mind

but who once set out fromhere—

mornings she’d take on

mountaintops alone