Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 27

January 28, 2025

Eva H.D., the natural hustle: poems

THE BOYS AT THE PIZZERIA

Drinking wine from a canfrom a glass. Wood

table, mittens. Moved inthis way and in

that. The young pizzaguys: doughty stand ins

looking like boys I mighthave loved. They could

have been, bouquet ofzinfandel lips, good

hands, ranginess ofyouthlimb, easy grin:

the lush sweetness of it,getting things done, thin

skin at their collarsblistering so you’d

want to soothe that itchwith cool fingers, palms.

You’d have wanted that,once, and gotten—or

not: let the bombs go offall over your

body then snuffed thewinedark flame of its song,

get lit again. turnedback toward the heat, youth,

rising like dough in theoven’s hot mouth.

I’monly seeing this now, Toronto poet Eva H.D.’s the natural hustle: poems(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2023), a collection that follows herfull-length debut,

Rotten Perfect Mouth

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press,2015) [see my review of such here] and collaborative art/photography volume withphotographer Kendall Townend,

Light Wounds

(2021). The poems that makeup the natural hustle offer an assemblage of declarative scenes; amontage of moments wrapped around other moments, attending the immediate, itwould suggest, of both the author’s urban landscape and memory. “Every summer,”she writes, as part of the poem “DONNA SUMMER,” “you entertain thoughts you’vehad before; through / a sweating glass, lacerated with heat, consider //whether there’ll ever be enough July, consider / the menu, the news fromAleppo, the breathing/ Chablis. You misapprehend, fail to think through /anything but your own righteous outrage, friends’ / afflictions, your partisanposture.” Through H.D., the past and the present interact, intermingle and evenreact, providing a suggestion that there are no singular moments, but thosethat connect in loose sequence. Everything holds, somehow, and everythingconnects. Composed as first-person narratives, these poems are rooted inlandscape, even across great distances, meditative swirls and the backlash ofrecollection. “Back to the highway.” she writes, as part of the extended sequence“GOD AND THE PATH TRAIN,” “Ramones doing their / Cretin hop syncopations like a/ bulimic mid-vomit like / this one song just has to leave my body, / acar cuts us off so close it’s / practically driving backwards. // Sunflowerdust on everything.” Or, as the same poem offers, near the end:

I’monly seeing this now, Toronto poet Eva H.D.’s the natural hustle: poems(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2023), a collection that follows herfull-length debut,

Rotten Perfect Mouth

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press,2015) [see my review of such here] and collaborative art/photography volume withphotographer Kendall Townend,

Light Wounds

(2021). The poems that makeup the natural hustle offer an assemblage of declarative scenes; amontage of moments wrapped around other moments, attending the immediate, itwould suggest, of both the author’s urban landscape and memory. “Every summer,”she writes, as part of the poem “DONNA SUMMER,” “you entertain thoughts you’vehad before; through / a sweating glass, lacerated with heat, consider //whether there’ll ever be enough July, consider / the menu, the news fromAleppo, the breathing/ Chablis. You misapprehend, fail to think through /anything but your own righteous outrage, friends’ / afflictions, your partisanposture.” Through H.D., the past and the present interact, intermingle and evenreact, providing a suggestion that there are no singular moments, but thosethat connect in loose sequence. Everything holds, somehow, and everythingconnects. Composed as first-person narratives, these poems are rooted inlandscape, even across great distances, meditative swirls and the backlash ofrecollection. “Back to the highway.” she writes, as part of the extended sequence“GOD AND THE PATH TRAIN,” “Ramones doing their / Cretin hop syncopations like a/ bulimic mid-vomit like / this one song just has to leave my body, / acar cuts us off so close it’s / practically driving backwards. // Sunflowerdust on everything.” Or, as the same poem offers, near the end: I sit here in a cleancool blue

plastic seat not caringless

about Camus who never

as it turns out even

once mentions the PATHtrain—

whether god is at the end

or Hoboken—I dunno

what people see

in the guy.

He’s not a map.

January 26, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Alice Fitzpatrick

AliceFitzpatrick hascontributed short stories to literary magazines and anthologies and is afearless champion of singing, cats, all things Welsh, and the Oxfordcomma. Her summers spent with her Welshfamily in Pembrokeshire inspired the creation of the setting of the Meredith Island Mystery series. She was a third of the way through the first draft of Secrets in the Water, the first book inthe series, when she realized this story of lost family history was inspired byher own family. Alice lives in Toronto but dreams of acottage on the Welsh coast. To learnmore about Alice and her writing, please visit her website at http://www.alicefitzpatrick.com.

1 - How did yourfirst book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

I always imaginedif I ever became a published writer, I would spend my days writing, but I underestimatedthe amount of marketing I have to do to get my name, my book, and my series outthere. Because I live in Canada butwrite a aeries that’s set in Wales, I have to promote to three geographicalareas: Canada, the US, and the UK. Self-promotion doesn’t come naturally to me,but I’ve learnt to push myself. While I’mgetting more and more comfortable with it all, I still wish I had time to write.

2 - How didyou come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

My first publicationwas in an anthology of high school poetry edited by Canadian poet GeorgeBowering. Buoyed by this success, I decidedto become the youngest poet to win the Governor General’s award, until I realizedI wasn’t a poet. I need space to tell mystories, and so I moved on to short fiction and later the novel.

3 - How longdoes it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s relativelyeasy for me to come up with ideas by asking “what if this happens?” I don’t normally do an outline for my books,but I do make notes on the characters, their relationships to each other, and theirsecrets. Before I begin to write, I haveto know the identity of the first victim, their killer, and the motive. This gets me through the first seventy or sopages. When I’m writing, I need to knowwhat’s happening in the next few scenes so I don’t get stuck.

4 - Where doesa work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I always know whatform a story will take. Obviously some ideaslend themselves to a shorter focussed format while others need the space of anovel. Having said that, the idea for Secrets in the Water came from a forty-pagestory I’d written decades before about the Welsh seaside resort where I spentmy childhood summers. At that point, myprotagonist, Kate, was a fourteen-year-old investigating her aunt’s death. When I decided to turn the story into afull-length novel, I made Kate a retired English teacher who wrote historicalnovels and gave her a sidekick.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy public readings. As a teacher, I’m quite comfortable standingin front of people and sharing my work with them. However, I get nervous if I’m recordedreading or being interviewed. I fear anymistakes I make will exist forever, whereas an in-person reading is ephemeraland quickly fades from memory.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

As someone whowrites genre rather than literary fiction, I don’t feel my work offers anyinsight into deep philosophical issues, but I do have themes for each book beyondsolving the mystery. Secrets examines different kinds of loveand what we’re prepared to do for that love. It’s also about recovering family history, the fragility of memory, andhow we tend to mythologize people who have disappeared from our lives. This makes Kate’s job of solving thefifty-year-old murder of her aunt all the harder. Whereas other authors might write crimefiction because it allows them to set the world straight, to provide justice tovictims, and bring order to chaos, for me it’s the need to understand whathappened and why. I’m intrigued by what makes seemingly ordinary people commitmurder.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

In times ofdistress and uncertainty, we all need an escape. During the Depression, people flocked tomovie houses, and the movie musical was born. The world of Meredith Island is one of community and support, and thesedays we need that more than ever.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

I don’t have betareaders or belong to a writing group, so I value my publisher’s objective eye. When my edits arrive, I’m always nervous incase I’ve got things so wrong that the book can’t be saved.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My favouritepiece of advice comes from Darcy Pattison: “The first draft of a story is totell you what the story is. The nextdrafts are a search for the best way to tell this story.”

As aperfectionist—and what writer isn’t or doesn’t aspire to be—I would get hung upon getting the first draft as good as I could. In the past, this would often stop me in my tracks as I edited andre-edited what I’d already written, often afraid to go on. Pattison’s advice gives me permission to letgo of expectations of immediate perfection. Wandering off the path is a valuable part of the process.

10 - How easyhas it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? Whatdo you see as the appeal?

I started mycareer writing literary short stories. Secrets took me so long to write becauseI had to learn not only how to write a full-length novel, but the requirementsof crime fiction. At the first Bloody Wordsconference I attended, an established crime writer gave me feedback on an earlyversion of my first chapter. She observed there was very little description. When I told her I was a short story writer,she smiled and said, “Oh, that explains it.”

11 - What kindof writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I’m awake ateight, read for an hour, and then check my emails and social media—just in casethere’s something important that has to be dealt with right away. There never is, although I tell myself thiswill free me to write uninterrupted for the rest of the day. While I’m eating my breakfast of oatmeal andtea, I watch one crime TV show which I rationalize as research and to kickstartthe little grey mystery-writing cells. By now it’s noon, guilt is setting in, and I can’t put off writing anylonger. This is when I drag myself up tomy office and start to write—after checking my emails and social media one moretime. The good news is that once I get started, I usually keep going until six,seven, or even eight o’clock.

12 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

My writing onlygets stalled when I don’t know what the characters will do next. That’s usually because I’ve started writingbefore fully understanding who they are and what motivates them. At that point, I have to take the time to fleshout their backstory.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Because I spentmy summers at my aunt and uncle’s hotel on the Welsh coast, home is the yeasty smellof beer coming from open doors of pubs, the greasy odour of fish and chips fromcafes, and of course seaweed and salt water. All of these have found their way into my books.

14 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

When I wasyounger, I would listened to classical music and imagine that my writing wouldcreate the same deep emotional feelings in the reader that music brought out inme. However, music touches a place deepin the soul, bypassing the analytic brain. Words can’t do that. They needour brains to decode their meanings.

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

When I firststarted writing my series, I discovered Jasper Fforde, a Welsh fantasy crimewriter, whose books opened my mind to a new world of possibilities, giving mepermission to create quirky characters and to ask my readers to suspend morethan a little disbelief.

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like totravel to Ireland and other parts of the UK. Ultimately I’d love to buy a seaside cottage in Wales.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

For most of mylife, I was a high school ESL and English teacher. I taught people—and myself—about language andstory-telling structure, and that has served me well. But I would also have loved to have been anarchaeologist. My Master’s degree is insocial history, and a lot of archaeology is social history. But I don’t have a head for science. So instead, I decided to have somearchaeology students come to the island to dig for the remains of an earlymedieval monk’s cell in the second Meredith Island Mystery, A Dark Death.

18 - What madeyou write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve been astoryteller ever since I can remember. It’s how I comprehend and interact with the world. While other people arrive late and offervague references to problems with public transit, I delight in recounting everydetail. Before I graduated from highschool, I’d received my first rejection letter when I sent Carol Burnett asketch I’d written, completed my first novel, and was published in a poetryanthology edited by Canadian poet George Bowering.

19 - What wasthe last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

Magpie Murders by Anthony Horowitz both awed and intimidatedme, while Thomas King’s CBC Massey Lectures TheTruth about Stories: A Native Narrative taught me about the power ofstorytelling. I rarely watch films, but Ido watch a lot of British television mysteries such as Midsomer Murder, Father Brown, and Sister Boniface Mysteries.

20 - What areyou currently working on?

I’ve justfinished the edits for A Dark Deathto be released in June, 2025, and am writing The Secret House of Death, the fifth book in the Meredith Island Mystery series. I’m also searching for apublisher for a stand-alone private investigator/police procedural/suspensenovel called That Which Was Lostwhich was inspired by a horrific car accident that killed eight teenagers in my hometownfifty years ago. Andif someone would like to make a series or film from the Meredith Island books,I wouldn’t say no.

January 25, 2025

Charles Bernstein, The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays & Comedies

If story’s other isnarrative, what is lyric’s other? Lyric is so generic that it’sdifficult to find a term to contrast with it, unless one moves to anothergenre, typically epic. Even so, the hegemony of a single-voice, “scenic”lyric, the Vampiric heart of Romantic Ideology, has been contested since Blake,Byron, Swinburne, Poe, Dickinson, and the slave songs, in the nineteenthcentury, and Stein, Loy, Williams, Pound, Eliot, Tolson, and Riding in theearly twentieth. The conventional lyric’s American other in the 1930s was the“objectivist” poem, in the 1950s “Projective Verse” and the “serial poem.” Inthe 1960s, Antin and Jerome Rothenberg suggested “deep image” and Amiri Barakaand company, “Black Arts.” There was a time in the early 1980s that poetsadvocated against the scenic lyric with terms such as “analytic lyric” or“transcended lyric.” Ron Silliman’s “new sentence” and David Antin’s “talkpoems,” as with “language-centered,” specifically presented themselves againstthe vanilla lyric.

Not voice, voices; not craft, process; not absorption,artifice; not virtue, irreverence; not figuration, abstraction; not thestandard, dialect; not regional, cosmopolitan; not normal, the strange; notemotion, sensation; not expressive, conceptual; not story, narrative; notidealism, materialism.

For binary opposition to intensify their aestheticengagement, and not become self-parody, it helps if they fall apart, so thatyou question the difference, confuse one with the other, or understand thedistinction as situational, as six is up from five but down from infinity,diction so low its high, solipsism so radical it dissolves into pure realism.(“The Unreliable Lyric”)

Thelatest from American poet and critic Charles Bernstein is the hefty collection TheKinds of Poetry I Want: Essays & Comedies (Chicago IL: University ofChicago Press, 2024), an assemblage of talks, essays, lectures, interviews,musings, reviews and speeches presented in a triptych ofsections—“Pixellation,” “Kinds” and “Doubletalk”—offered with no introduction,but a preface by his friend, the late New York writer Paul Auster (1947-2024),“Twenty-Five Sentences Containing the Words ‘Charles Bernstein’,” originallyoffered by Auster as an introduction to a reading Bernstein was doing atPrinceton University on March 14, 1990. As Auster spoke, nearly thirty-fiveyears ago this month:

Charles Bernstein is apoet. Charles Bernstein is a critic. Charles Bernstein is a man who talks. Andwhether he is writing or talking, Charles Bernstein is a trouble-maker. Beingfond of trouble-makers myself, I am particular fond of the trouble-maker designatedby the words Charles Bernstein.

Charles Bernstein has reintroduced a spirit of polemicinto the world of American poetry. in the exhausted atmosphere in which so muchof our writing takes place, Charles Bernstein has battled long and hard to makeboth writers and readers aware of the implications embedded in each and everylanguage act we partake of as citizens of this vast, troubled country. Whetheror not you agree with what Charles Bernstein has to say is less important thanthe fact that it has become more and more important to what he is saying.

Theintroduction Auster make then still holds, certainly, although I would havebeen interested in some kind of framing as to why these particular piecesarranged in this particular way for this particular collection. Trouble-maker,trickster, indeed, that wiley Bernstein, providing just enough for a reader tosupply the rest, I suppose. The back cover, at least, offers this paragraph,the first of two, as copy: “For more than four decades, Charles Bernstein hasbeen at the forefront of experimental poetry, ever reaching for a radicalpoetics that defies schools, periods, and cultural institutions. The Kindsof Poetry I Want is a celebration on aesthetics and literary studies,interviews with other poets, autobiographical sketches, and more.” The piecescollected here are playful, thoughtful and dense, running a length and breadthof American poetry and poetics, including a handful of clusters of shortercritical responses on poets such as Robert Duncan, Robin Blaser, David Bromige [see my review of the collected Bromige here],Louis Zukofsky, Robert Creeley, Madeline Gins, Rae Armantrout [see my review of her latest here], RosmarieWaldrop [see my review of her latest here], Johanna Drucker, Tonya Foster [see my review of Foster's debut here] and Pierre Joris, among others, runningthrough the contemporary and historical of American poetics. “It’s funny tohave to be brief about Robert Duncan,” the opening section of one of theseessays begins, “since there is nothing brief about his work or my responses toit.”

Theintroduction Auster make then still holds, certainly, although I would havebeen interested in some kind of framing as to why these particular piecesarranged in this particular way for this particular collection. Trouble-maker,trickster, indeed, that wiley Bernstein, providing just enough for a reader tosupply the rest, I suppose. The back cover, at least, offers this paragraph,the first of two, as copy: “For more than four decades, Charles Bernstein hasbeen at the forefront of experimental poetry, ever reaching for a radicalpoetics that defies schools, periods, and cultural institutions. The Kindsof Poetry I Want is a celebration on aesthetics and literary studies,interviews with other poets, autobiographical sketches, and more.” The piecescollected here are playful, thoughtful and dense, running a length and breadthof American poetry and poetics, including a handful of clusters of shortercritical responses on poets such as Robert Duncan, Robin Blaser, David Bromige [see my review of the collected Bromige here],Louis Zukofsky, Robert Creeley, Madeline Gins, Rae Armantrout [see my review of her latest here], RosmarieWaldrop [see my review of her latest here], Johanna Drucker, Tonya Foster [see my review of Foster's debut here] and Pierre Joris, among others, runningthrough the contemporary and historical of American poetics. “It’s funny tohave to be brief about Robert Duncan,” the opening section of one of theseessays begins, “since there is nothing brief about his work or my responses toit.” CharlesBernstein’s poetic allows him to respond critically through prose and poetryboth, accumulating points across a series of seamless grids. If Vancouver’s George Bowering has been our plainspeaking Canadian troublemaker and critical thinkerthrough lyric and experimental poetry across the decades, responding to theworks of those around him since the 1960s, Bernstein is the other side of thatsame play, but with a far denser approach through academic language. As Bernsteinwrites on New York poet Tonya Foster: “My comments on Foster are abstract andtechnical. But Foster’s work doesn’t feel abstruse or conceptual (two qualitiesI often like in poems). Foster’s work is constructed as a system or environmentthat explores the emergence and disappearance of identity and place. It’s not apoetry of, or about, fixed points of reference that are described. The sitesemerge and submerge in the flickering probes of Foster’s accumulation ofvoices, her collection of verbal markers and shifting signs.” As well, Iparticularly enjoyed the opening to his first response in “Groucho and Me,” aninterview conducted by Robert Wood, in which Bernstein offers:

I only know what I thinkwhen I am in conversation. Conversation’s an art: my thinking comes alive indialog. I don’t have doctrines or positions, I have modes of engagement,situational rejoinders, reaction deformations. It takes two to tangle, three torumble, four to do the Brooklyn trot. I want my writing to dance to thechanging beats of the house band.

Thereis an incredible amount of writing, thought, critical detail and response inthis collection, assembling notes, longer essays, talks and conversations acrosssome four hundred pages, the density of which cannot be overstated. If you wantsome of that serious play that the late Toronto poet bpNichol mentioned, this mightbe what he meant.

January 24, 2025

Lily Brown, BLADE WORK

I heard the voice ofreason

swerve boneward as itmouthed

the high hills of Art.

I know both sides:

the violence of artifact

and the living tree,

airy branches full ofweeds.

Once a sitting thing in athing

that stuck me back, I walk

straight out in heavyrain,

trying not to aim,

his lungs gum-thick,

each word towed out witha chain

pulled simultaneouslyback.

I make another motion,

send a jagged gift. (“VenusTransit”)

I’vebeen an admirer of the work of American poet Lily Brown, a poet and writingteacher currently based in Maine [see her 12 or 20 questions here] ever sincediscovering her work through the chapbook Being One (Brave Men, 2011)[see my review of such here]. That particular title was soon followed by herfull-length debut,

Rust or Go Missing

(Cleveland OH: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2011) [see my review of such here] as well as afurther handful of chapbooks, including

The Haptic Cold

(Brooklyn NY:Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013) [see my review of such here]. Her latestcollection, her second full-length, is

BLADE WORK

(Anderson SC: ParlorPress, 2025), produced as Winner of the New Measure Poetry Prize, as selectedby Carl Phillips. I’m amazed at the carved sharpness and meditative distancestravelled across her purposeful, tactful lyrics. Through Brown, every word,line and step is deliberately and carefully set, but with such a cadence ofease, composing poems of disruption, description and a hint of surrealism, setin pure stone. “The horse gallops / fog under its chin,” she writes, to openthe poem “After Susan Rothenberg’s Untitled Drawing, No. 41, 1977,” “behinda hind leg, / haze in parts erased. / The smudge in the body’s / portioned air.Darwin / threw lizards / by the tail / into the ocean / to find out if theyswim.” There’s such a clarity, a density, to her poems, one that allows forstunning moments, the narratives of her poems accumulating with such force intoperfect phrases, perfect landings. As the second half of her short poem “Transparency”offers: “All day I splinter leaves / with my feet, conduct them // in, singedflags. / I think I see you in the back window, // waving there, your showmoving / west then east. // Torso turns to see // how great a distance / I earnedto make.” The underplayed power of her poems are enormous, landing her endingswith incredible grace, the click of a latch to know that door is now closed. “Givesome back to the mapland.” She writes, to open “The Complete Poems,” a piececomposed “after Elizabeth Bishop.” “Material qualities, stammering /repetition. More interested / in atmosphere, leaf and cloud, / than clock-like architecture’salarms.”

I’vebeen an admirer of the work of American poet Lily Brown, a poet and writingteacher currently based in Maine [see her 12 or 20 questions here] ever sincediscovering her work through the chapbook Being One (Brave Men, 2011)[see my review of such here]. That particular title was soon followed by herfull-length debut,

Rust or Go Missing

(Cleveland OH: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2011) [see my review of such here] as well as afurther handful of chapbooks, including

The Haptic Cold

(Brooklyn NY:Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013) [see my review of such here]. Her latestcollection, her second full-length, is

BLADE WORK

(Anderson SC: ParlorPress, 2025), produced as Winner of the New Measure Poetry Prize, as selectedby Carl Phillips. I’m amazed at the carved sharpness and meditative distancestravelled across her purposeful, tactful lyrics. Through Brown, every word,line and step is deliberately and carefully set, but with such a cadence ofease, composing poems of disruption, description and a hint of surrealism, setin pure stone. “The horse gallops / fog under its chin,” she writes, to openthe poem “After Susan Rothenberg’s Untitled Drawing, No. 41, 1977,” “behinda hind leg, / haze in parts erased. / The smudge in the body’s / portioned air.Darwin / threw lizards / by the tail / into the ocean / to find out if theyswim.” There’s such a clarity, a density, to her poems, one that allows forstunning moments, the narratives of her poems accumulating with such force intoperfect phrases, perfect landings. As the second half of her short poem “Transparency”offers: “All day I splinter leaves / with my feet, conduct them // in, singedflags. / I think I see you in the back window, // waving there, your showmoving / west then east. // Torso turns to see // how great a distance / I earnedto make.” The underplayed power of her poems are enormous, landing her endingswith incredible grace, the click of a latch to know that door is now closed. “Givesome back to the mapland.” She writes, to open “The Complete Poems,” a piececomposed “after Elizabeth Bishop.” “Material qualities, stammering /repetition. More interested / in atmosphere, leaf and cloud, / than clock-like architecture’salarms.”

January 23, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Scott Ferry

ScottFerry helps our Veterans heal as a RN in the Seattle area. His twomost recent books are Sapphires on the Graves from Glass Lyre Press and 500Hidden Teeth from Meat For Tea Press. More of his work can be found @ferrypoetry.com.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

My first published book was The only thing that makes sense isto grow back in 2019. I was really trying to win a Write Bloody Contest andwrote many of the poems for that purpose. But when Moon Tide Press and EricMorago became interested in my project, I focused on the work itself as awhole, as an entity. It is that book that many of us has to write which is thecore bile and lymph of our story and the answer to: who am I? I felt I neededthis signature piece, this clear portrait.

My recent work does not need to tell as much of a narrative, itdoesn’t need to explain or legitimize itself. I am writing from the ether,catching fleshy cicadas out of the air and spitting them on to the page.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposedto, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Most of my poems have written themselves, honestly. From thebeginning it has flowed easily. I didn’t choose this shit, it chose me. I amjust a monkey mouthpiece for the ghosts.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

Oh no, no notes besides maybe an idea or a vignette. I will writemyself a note or an email to remember for later. An example is last night myson turned in his sleep and said “read it.” I wonder what book he wanted readto him? There is a poem there I will have to sit down and write. Once I open upto the subconscious, I just let it go out and direct it a bit and maybe fix aword later. Most of my poems are first and final drafts. I don’t agonize overthem at all. They are better when they are allowed to just spring out andsplat!

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With the last two books I had an idea what I wanted to do from thebeginning. Sapphires on the Graves was going to be a book of prose poemswith very little punctuation and a cyclical and surreal feel. 500 HiddenTeeth began as a project where I was going to write 500 separate poems inone-line sentences. As the book progressed the sentences began to connect andwaver and connect again and many of the sentences ended up as groups that couldbe seen as poems. Yet, my intent is that each sentence is still a poem and thewhole book is one large poem. I like the last description best.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter toyour creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I mean I love doing readings! I used to get nervous but now Idon’t give two fucks. I know my poetry is solid, I am not going to fake beinghumble. I realized it is an ok thing to give myself, that confidence. I havedone readings for like three people in an audience before and it was great! Ilove feeling the way the sound hits people. I also love hearing good poets readand let the hum of it all wash over me. I love the brotherhood of it. I wish Iwent to more readings, actually. Being a father of two doesn’t allow for lotsof school night outings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?What do you even think the current questions are?

I am always trying to deconstruct God, god, I, i, We, we. I try tofind the places where the seams are coming apart and unravel them more. I bringthe dead into the living room. I chase ancient trains into melting icecaps. Ilaugh and scream and rip out my throat and make it sing. I care about mankind,about innocence, about intent, about karma in real time. I will always lift themoon out of the well and feed the lampreys my fears. I can dig into my tendonsand find lead. I can chew roots. I watch the crows. I burn most of it in theprocess of washing.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

Shit. Like I said I am here for the harpies and the shadows andthe veins. I only tell what I have heard in trance. My job is to go into thatbroken avalanche of ribs and bring out spells and ash. I strive for magic. Istrive for honesty. In that place it is all one water.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I haven’t really gotten much from editors, honestly. I have had mygood friends (Lillian Necakov and Lauren Scharhag) to read things sometimes andgive me feedback which many times I don’t use. I trust the original poem mostof the time. In terms of producing a book, I am pretty hands-on with my coverart and layout. I feel that I have an eye for that and I don’t compromise much.I haven’t had problems or conflicts with publishers on this, thankfully. I seereally great books of poems with really old-fashioned covers and it just irksme. At least use a cool font. Get some original art!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard(not necessarily given to you directly)?

I heard something the other day which resonated with me. Don’tspend your time hoping people will be the way you want them to be. Deal withthem as they are. Work on yourself to be that version. Focus inside, let go ofexpectation. That is freeing. Not that I have been able to do it .

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write at work a lot because I have a desk job that I can usuallyfinish in a few hours. And my work group is pretty quiet. I also can write lateat night, but that is less desirable.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do youturn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t stress it. I wait. I read poetry that I admire. I listenfor triggers.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cedar, eggs cooking, toast, cilantro, onion, coffee, the burntsmell of my gas fireplace, my roses and lilies, rain.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

I do a lot of photography. Mostly nature stuff, clouds treesreflections abstracts. I get much of my inspiration from images and patternsunder the images and patterns. Music, usually KEXP. Jazz, shoegaze, some punk,REM, Radiohead. Lately a really cool band called Peel Dream Magazine. Anysurrealistic art.

14 - What other writers or writings are importantfor your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Lillian Necakov, Lauren Scharhag, Diane Seuss, Daniel McGinn,Douglas Cole, Gary Barwin, George Franklin, Connie Post are some of mycontemporary favorites. Poetry that has flow and weirdness and honesty. AnyMagical Realism, Marquez, Borges.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven'tyet done?

Travel around Europe.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, I was a high school English teacher for about 5 years. Bignope. I have heard that AI is ruining college teaching as well so teaching isout. I mean I would love to teach poetry. I am a licensed acupuncturist but itnever paid the bills. I have a low-key nursing job which I love.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

Well it came naturally starting my junior year in high school. Icertainly never made any money doing it. It is the way I get to shout into thewind.

18 - What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

I really liked Lauren Scharhag’s Screaming Intensifies abook of well-crafted horror stories. I read Diane Seuss’s last two books.Lillian and Gary’s book duck eats yeast, quacks, explodes; man loses eye waspretty mindblowing. Douglas Cole’s The Cabin at the End of the World,fantastic. George Franklin’s What the Angel Saw, What the Saint Refusedis important.

As for a film, I watched Killing Eve in its entirety and itwas the best series for me since Breaking Bad.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I am currently involved in two collaborations, one with Lindsey Royce using the art of Sarah Petruziello as ekphrastic prompts and one still very much in process with Aakriti Kuntal. Both are really stretching my abilityto interface and bounce off other artists, which is wonderful.

I don’t have an individual project yet, but it will show up like amole in my cat’s claws.

January 22, 2025

On Susanne Dyckman and Elizabeth Robinson’s Rendered Paradise

My review of Susanne Dyckman and Elizabeth Robinson's collaborative Rendered Paradise (Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2024) is now online at Seneca Review.

My review of Susanne Dyckman and Elizabeth Robinson's collaborative Rendered Paradise (Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2024) is now online at Seneca Review.January 21, 2025

Karla Kelsey, Transcendental Factory: For Mina Loy

Mina Loy. Not her birth nameMina Gertrude Lowy, or Löwy, depending on the scholar, or the flourish. Not hermarried name, Mrs. Stephen Haweis, or her nickname, Dusie, but “Loy”—the nameshe’d chosen to exhibit under since her first public success as an artist inthe 1904 Salon d’Automne. The name under which her first published writing, “Aphorismson Futurism,” will appear in Alfred Stieglitz’s journal, Camera Work, in1914.

Photographs of Mina Loy areMina Loy, have become Mina Loy. Glossy black-and-white inserts of Haweis’sphotos—a touch of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, James McNeill Whistler, and EdwardBurne-Jones—are joined by those taken by Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, and LeeMiller in Carolyn Burke’s Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy,published in hardcover by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1996. And then paperbackby the University of California Press in 1997. Stacked at the front ofbookstores and years later appointed the best place among the remainders, Loylooks out from the cover as she leans toward the small bronze statue shecradles in her left hand, eyes catching Haweis’s camera sidelong. A pleasantblouse, hair pulled softly back. Also in 1996, The Lost Lunar Baedecker,selected poems edited by Rober L. Conover, is published by FSG, and for thefirst time Loy’s poetry reaches a wide audience. Here she poses for Man Ray inprofile. A thermometer she’s fashioned into an earring dangles from her ear. Eyesclosed, she tilts her head toward the light.

I’dbeen curious about this recently-published self-described fiction/biography byAmerican writer and editor Karla Kelsey [see my review here of one her poetry titles], her

Transcendental Factory: For Mina Loy

(Winter Editions, 2024), a book that offers this further descriptionon the back cover: “Combining experimental biography with fiction and fact,poet Karla Kelsey’s lyric-documentary rendezvous with iconoclastic writer and visual artist Mina Loy (1882-1966) creates a resonating space for the lost and undocumented.”Through her detailed exploration and excavation of the legendary, almostmythical, figure of Mina Loy, Kelsey is clearly aware of how portraits areshaped, prepared, and made, framed and crafted, her own narrative swirlingaround an impossible centre that suggests itself too evasive to properlycapture. Structured across eleven chapters, each of which is titled a differentyear from 1886 to 1965, Kelsey composes her biography out-of-sequence, focusingon moments in time and their interplay, allowing the story to almost unfold asripples out from a single moment. The book opens with a chapter titled “1905,” thathas Loy in a photography studio: “Twenty-three-year-old Mina Loy poses as Mrs.Stephen Haweis, the artist’s artistic wife. She sits before an easel wearing aprint dress, black belt, and straw hat she’d bedecked with enormous rosebuds.”Kelsey begins with an image of Loy that is crafted, curated, by another, withthe full participation of Loy herself; one that allows for a shimmering effect,far more performative than documentary in purpose. From this moment ofartifice, Kelsey begins. Two paragraphs later:

I’dbeen curious about this recently-published self-described fiction/biography byAmerican writer and editor Karla Kelsey [see my review here of one her poetry titles], her

Transcendental Factory: For Mina Loy

(Winter Editions, 2024), a book that offers this further descriptionon the back cover: “Combining experimental biography with fiction and fact,poet Karla Kelsey’s lyric-documentary rendezvous with iconoclastic writer and visual artist Mina Loy (1882-1966) creates a resonating space for the lost and undocumented.”Through her detailed exploration and excavation of the legendary, almostmythical, figure of Mina Loy, Kelsey is clearly aware of how portraits areshaped, prepared, and made, framed and crafted, her own narrative swirlingaround an impossible centre that suggests itself too evasive to properlycapture. Structured across eleven chapters, each of which is titled a differentyear from 1886 to 1965, Kelsey composes her biography out-of-sequence, focusingon moments in time and their interplay, allowing the story to almost unfold asripples out from a single moment. The book opens with a chapter titled “1905,” thathas Loy in a photography studio: “Twenty-three-year-old Mina Loy poses as Mrs.Stephen Haweis, the artist’s artistic wife. She sits before an easel wearing aprint dress, black belt, and straw hat she’d bedecked with enormous rosebuds.”Kelsey begins with an image of Loy that is crafted, curated, by another, withthe full participation of Loy herself; one that allows for a shimmering effect,far more performative than documentary in purpose. From this moment ofartifice, Kelsey begins. Two paragraphs later:A third photograph capturesLoy from the bust up. She’s pinned her paisley-patterrned robe to make of herbare chest a white diamond while artfully covering her breasts. She looks insharp profile to the right, hair Athena-coiled atop her head and tied with afloral scarf. Budapest means British Empire. Elegant, bohemian, so “Loy (MlleMina), née à Hampstead (Àngle-terre), Anglaise”—as she’s listed in thecatalogue for the 1905 Salon d’Automne above the titles of the four portraitsshe exhibits. Found on a Weebly site, someone’s school project on Loy, withtarot cards and a map of the Arno, this photo is my favorite, but—unattributed andwithout citation—it might not be of Loy at all.

Iwould argue slightly with the description of the book, as Kelsey’s approach tothe whole project is reminiscent of other titles also blending non-fiction researchwith a kind of lyric memoir, specifically Ottawa writer Elizabeth Hay’s CaptivityTales: Canadians in New York (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 1993) and Montrealwriter Gail Scott’s Furniture Music: A Northern in Manhattan: Poets/Politics[2008-2012] (Seattle/New York: Wave Books, 2023) [see my piece on such here]. While someone, whether publisher or author, might suggest Kelsey’s worksits under “Fiction/Biography,” Transcendental Factory reads firmly setwithin the genre of creative non-fiction, a genre in which the author is not adistant narrator, separate from the action, but one deeply engaged within thenarrative of the story. Early in the fifth chapter, “1925,” Kelsey writes:

I don my faux Turkish foxover an unseasonably thin dress to create a Mina Loy—or Myrna Loy—type woman.Psychically I’m all Hannah Höch collage, machine arms stuck to a Siren’s body. Whilethe interior remains private, for the outfit to work does it matter whether I stylemyself as Mina Loy, born December 27, 1882, with the name Mina Gertrude Lowy ina North London suburb or as Myrna Loy, born August 2, 1905, as Myrna Adele Williamsin Helena, Montana? In her early twenties Williams changed her last name to Loyat the suggestion of a wild Russian writer who’d found his way to Hollywood. Thisman, let us call him Sasha, let us give him a shock of white hair andsand-colored eyes, could have been Mina Loy’s lover when, after a summer inVienna, 1922—sketching Freud’s portrait as he read some of her prose—she movesto Berlin and stays there until relocating to Paris in spring of 1923.

I’mcharmed by the music, the lyric, of Kelsey’s prose, all highly deliberatethrough such luscious sweep and gesture; the prose is reminiscent of how Isaac Jarnot originally worked chapters of their biography of Robert Duncan, wellbefore the multiple-year peer-reviewed process appeared to smooth over the remarkablemusic to land as

Robert Duncan, The Ambassador from Venus: A Biography

(Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2012). “Loy’s Jemima,”Kelsey writes, “thought to be a self-portrait and shown in London at the NewEnglish Art Club’s 1910 summer exhibition, will be lost. Also from circa 1910, Ladiesat Tea is lost, Ladies Watching a Ballet is lost, Ladies Fishingis lost, Heart Shop is lost, The Little Carnival is lost, Voyageursis lost. Lost, lost— [.]” Kelsey offers a biography of depictions and smoke, oftenarticulating a particular lack of archival information by detailing all thatsurrounds it, offering details and surrounding context so fine that the contoursof Loy’s story can’t help but find definition. She digs deep into all thatthere is to uncover and decipher, but there is still, as Kelsey suggests, somuch of Loy’s narrative that is missing; too much of Loy’s image defined by theworks and depictions of those that surrounded her, certain of which remainsincomplete, contradictory and even incorrect (including the portrait on thebook’s cover, long attributed to be of Loy but actually, as Kelsey learnsthrough her research, of American actress Evelyn Brent, circa 1920). Kelseyworks through such wonderful prose across research, informed speculation,conjecture and intricate wanderings across and around her subject, providing paragraphsof context around what else was happening during those same years as Loy, asimportant to her story as those bare facts of her life, of which there are toofew. Early in chapter “1965,” for example, she offers one of a number of passagesthat provide a broader context from which Loy can’t help but exist in the worldalongside and within, whether directly or indirectly. As the passage begins:

I’mcharmed by the music, the lyric, of Kelsey’s prose, all highly deliberatethrough such luscious sweep and gesture; the prose is reminiscent of how Isaac Jarnot originally worked chapters of their biography of Robert Duncan, wellbefore the multiple-year peer-reviewed process appeared to smooth over the remarkablemusic to land as

Robert Duncan, The Ambassador from Venus: A Biography

(Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2012). “Loy’s Jemima,”Kelsey writes, “thought to be a self-portrait and shown in London at the NewEnglish Art Club’s 1910 summer exhibition, will be lost. Also from circa 1910, Ladiesat Tea is lost, Ladies Watching a Ballet is lost, Ladies Fishingis lost, Heart Shop is lost, The Little Carnival is lost, Voyageursis lost. Lost, lost— [.]” Kelsey offers a biography of depictions and smoke, oftenarticulating a particular lack of archival information by detailing all thatsurrounds it, offering details and surrounding context so fine that the contoursof Loy’s story can’t help but find definition. She digs deep into all thatthere is to uncover and decipher, but there is still, as Kelsey suggests, somuch of Loy’s narrative that is missing; too much of Loy’s image defined by theworks and depictions of those that surrounded her, certain of which remainsincomplete, contradictory and even incorrect (including the portrait on thebook’s cover, long attributed to be of Loy but actually, as Kelsey learnsthrough her research, of American actress Evelyn Brent, circa 1920). Kelseyworks through such wonderful prose across research, informed speculation,conjecture and intricate wanderings across and around her subject, providing paragraphsof context around what else was happening during those same years as Loy, asimportant to her story as those bare facts of her life, of which there are toofew. Early in chapter “1965,” for example, she offers one of a number of passagesthat provide a broader context from which Loy can’t help but exist in the worldalongside and within, whether directly or indirectly. As the passage begins:In 1965 the US increasesmilitary forces in South Vietnam and begins Operation Rolling Thunder, an aerialbombardment campaign over North Vietnam which will last until 1968, killingmore than fifty-two thousand people. In 1965 most of Congress and much of theUS support the war, although tens of thousands attend the antiwar teach-in atthe University of California at Berkeley. Half the population of the US isunder twenty-five. Eva Hesse is awarded a year-long fellowship in an abandonedtextile factory in Germany and begins to move into the three-dimensional spaceof found objects and papier-mâché. By the end of her residency, she willconsider herself a sculptor. Carolee Schneemann teaches herself how to makefilms.

Thepublication of Transcendental Factory follows close on the heels of Lost Writings: Two Novels by Mina Loy, edited by Karla Kelsey (New Haven CT: YaleUniversity Press, 2024), a pairing that offers an echo to Ianthe Brautigan’smemoir of her late father, Richard Brautigan, You Can’t Catch Death: A Daughter’s Memoir (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001) alongside the posthumous appearanceof Richard Brautigan’s final novel, An Unfortunate Woman (St. Martin’sGriffin, 2001), two years after a third title, Brautigan’s long-lost volume, TheEdna Webster Collection of Undiscovered Writings (Mariner Books, 1999). Forbest effect, one might suppose, these titles appear in clusters, to catch theattention. Are you paying attention?

January 20, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Eric Weiskott

Eric Weiskott grew up in Greenport, NewYork, on the east end of Long Island. He teaches poetry and poetics at BostonCollege, with a focus on the fourteenth and twenty-first centuries.

Weiskott is the author of thefull-length poetry book Cycle of Dreams (punctum books, 2024), thepoetry chapbook Chanties: An American Dream (Bottlecap Press, 2023), andthe scholarly book Meter and Modernity in English Verse, 1350–1650(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). His poems appear in Fence, TexasReview, and Exacting Clam.

How did your first book or chapbook changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

Well, Chanties came outa year before Cycle of Dreams but was written much later. I’vebeen living with the core poems of Cycle of Dreams in someform since college (2005–2009), whereas I wrote Chanties in2023. A difference between the books is that Chanties isexploring the prose poem form, while Cycle of Dreams is moreinterested in couplets and the sonnet. Also, Chanties isthemed where Cycle of Dreams found a medieval interlocutor inWilliam Langland. It’s like the difference between a concept album and aninterview.

How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I guess I have always been a poet and areader of poetry, from the time I could. And for me reading poetry and writingit are two sides of the same activity. I don’t remember a time before poetry. Iadmire short stories and novels that are done well, but they rarely inspire meto write fiction.

How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

Most of the righthand-side poemsof Cycle of Dreams, the original ones, have been percolatingfor over a decade. The project was languishing for the longest time—its themesand gestures made sense in my head, but not to readers, until I realized thatwhat it needed was a second dimension, something to simultaneously ground itand question it. I found that in William Langland’s fourteenth-century dreamvision Piers Plowman. The lefthand-side poems are free adaptationsof passages from Piers Plowman. The work of Anne Carson (who saysshe never works with fewer than three desks full of different materials) helpedme see the energy that could come from combining things. Christian Schlegel’s HonestJames (2015) was also an influence.

Where does a poem usually begin for you?Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project,or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?

Poems usually begin for me with a phrasethat catches my attention. It’s usually not my own language, but language I’ve(over)heard during the normal course of my day. My mentor, the poet Elizabeth Willis, has said that it is amazing what you can hear in political discourse ifyou listen to it poetically. I find this to be true of all language: it’sconstantly coming at us, and it’s the poet’s job to catch language as itscreeches past. The dead metaphors in idioms are gemstones for poetic making.To answer your second question, I find it difficult to write a standalone poem.While (as my last answer reveals) the shape of the book is frequently unclearto me for most of the composition process, I’m always writing toward somethinglarger than a poem.

Are public readings part of or counter toyour creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy doing readings. I’ve read atthe Brookline Booksmith and at Trident in Boston, as well as at Boston Collegealongside colleagues. I’m thankful to have many poet-friends in my department:Allison Adair, Allison Curseen, Sarah Ehrich, Kim Garcia, Suzanne Matson, JamesNajarian, Maxim Shrayer, Andrew Sofer.

Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?What do you even think the current questions are?

For me, the poems find the questionsrather than the questions leading the poems. With Chanties Inoticed that a lot of poems ended with references to climate change—like “Forecast”does in Cycle of Dreams. In Cycle of Dreams somethemes that emerged were the politics of memory and the practice of annotationor commentary. A late addition to the manuscript that I felt really openedthings up was the addition of italicized glosses or marginal notes here andthere, often taken from other, non-poetic texts. This mimics how medievalreaders marked up their manuscripts. It allowed me to bring extra voices intothe poem without having to create a tunnel between voice A and voice B: A and Bcan simply sit side by side on a single line of type, because all readersintuitively grasp what it means to write or type in the margins. There’s powerin the margins, and the margins are places for questioning power.

What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

There’s a long tradition of (aprivileged few) writers taking up a lot of air. Think of Vladimir Nabokov’s lectures, later published as books. “Here is the master.” In a way theinstitution of the MFA continues that tradition, as does, in a low-brow mode,MasterClass’s videos by subscription. In response to this, the zeitgeist in2024 suggests that writers (even poets) are just like anyone else. That claimsstructures Ben Lerner’s Hatred of Poetry (2016). “Don’t worry,I, a published poet, also find poetry weird and aggravating.” I think writersare among the people doing the work to question our world and realize a betterone, but lots of other people are also doing that work: activists, parents,teachers of all kinds.

Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

As you know, unlike fiction, poetrygenerally isn’t edited too heavily by the press. I have a small group ofwriters I share work with; it has taken a lot of time and happenstance to findthem and figure out what to trade in kind (since they are not all writingpoetry now), but it’s working. I began searching more actively for fellowwriters around the time when I began teaching creative writing workshops. Itdidn’t make sense to host this formative intellectual community with mystudents, which resembled my experience of poetry in college, and not work tocreate something similar for myself in the present.

What is the best piece of advice you’veheard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Allison Adair visited my class and toldmy students, “When you’re moved by the spirit, write; when you’re not, revise.”It’s fantastic advice.

How easy has it been for you to movebetween genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

In hindsight I can see that I gravitatedtoward the Middle Ages because it was the great era of self-theorizedliterature. It was only much later that “poetry” and “critical writing”diverged. As Ingrid Nelson writes, “Where a modern reader sees in a literarytext something to be analyzed in a separate critical work, medieval literatureitself serves the purpose of dilation and explication typical of much moderncritical analysis” (“ Form’s Practice ,” 38). So I suppose I have alwaysbeen interested in how poetry and critical thought can speak to each otherinstead of just blocking each other. We are all familiar with the poem thatthinks it has all the answers, or the essay that buries the poem underirrelevancies. Cycle of Dreams achieves a poetry/criticismmeld in one way, by placing lines of poetry and sentences of criticism on thesame line of type; my current monograph project, which comparesfourteenth-century and contemporary poetries, does it in another way and inanother mode. That’s not to say it is easy to do. There’s an inescapableasymmetry between poetry (even critically inflected poetry) and criticism,because poetry is fundamentally an event, but criticism is fundamentally acommentary.

What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Teaching creative writing has reopenedmy creative writing practice. I write along with my students, then do deeprevisions over the summer.

When your writing gets stalled, where doyou turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When my writing gets stalled, I read.Some poetry books I have loved lately are Alice Notley’s Mysteries ofSmall Houses (1998), Solmaz Sharif’s Customs (2022),and Prageeta Sharma’s Grief Sequence (2019). Studying medievalliterature, so much of which is translated from or otherwise derivative ofearlier texts, has given me permission to be directly influenced by writerswhom I admire. Billy Collins once read at BC, and in the q&a he said hefound his voice in poetry by deleting all other influences. The poet in avacuum: I thought it was bad writing advice as well as a shallow account of howpoetic voice is made (though unsurprising, coming from Collins, whose poemshave an annoying sameness).

What fragrance reminds you of home?

Salt air! I grew up on the shores of theLong Island Sound.

David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

Music is a close second to poetry forme. I listen to music all day and tend to binge on individual singers orgroups, going deep into their catalog to get a comprehensive sense of theirsound. I guess I can’t help approaching it like another form of research.Neither of my poetry books is primarily music-based, but a chapbook manuscriptI have drafted contains ekphrastic poems about Bob Dylan and Gillian Welch. Thepoem is a kind of song, less because of the shared lineage of lyric thanbecause it’s words in time. My current monograph project has a chapter onDylan.

What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

See my answer to your question aboutgetting stalled.

What would you like to do that you haven’tyet done?

Right now I’m working on a long poem.All my poems are short; I want to tap into the capacity of a poem that goespages without ending, like Lerner’s “The Dark Threw Patches Down upon Me Also,”his Walt Whitman poem. Even the page-and-a-half poems of Notley’s Mysteriesof Small Houses are mysteries to me. I can already feel the poemI’m writing subdividing itself into sections. I’m essentially a lyric, not anarrative, poet.

If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

I could have imagined a career as alawyer or a mediocre guitarist.

What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

I’m uncertain how to answer, as I don’texperience writing as a choice. It’s a compulsion I have always felt, since Ilearned to read and write. For most people, there is a certain autumn when theyare no longer returning to school, and reading and writing therefore take onsome new professional, instrumental significance in their lives, or elsereading becomes strictly for pleasure. Because this turn never happened in mylife, I’ve never really reassessed my relationship to writing or reading. Theclosest was in graduate school, when I went on a long creative-writing hiatusto become an expert in medieval literature and write a dissertation. I wouldhave found it too hard to do both at once, though my cohort-mate, the poet and professor Edgar Garcia, managed to do it. Cycle of Dreams islike a synthesis of my college and graduate-school selves.

What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

I think it is not too early to callElizabeth Willis’s Liontaming in America (2024) “great.” Anextraordinarily multifaceted and moving book, it’s destined to become a classicof American literature. It’s part critical history of Mormonism, part spiritualbiography, part defense of poetry. Willis doesn’t write remotely like Nabokov,but her book has a Nabokovian (or Langlandian) kaleidoscopic quality, as if allof life has rushed into the prose. I’m more of a TV-series junkie than a filmbuff, but the last film I remember loving was The Long Goodbye (1973),directed by Robert Altman and starring a young Elliott Gould.

What are you currently working on?

I have a chapbook manuscript I will berevising in the new year. Working title: Sisyphus the Completist.And I’ve just this semester begun writing toward a second full-length poetrybook, possibly combinable with Sisyphus. Too early to say muchabout it, but I am drafting it on blank pages in a rare book of mine from 1745.

January 19, 2025

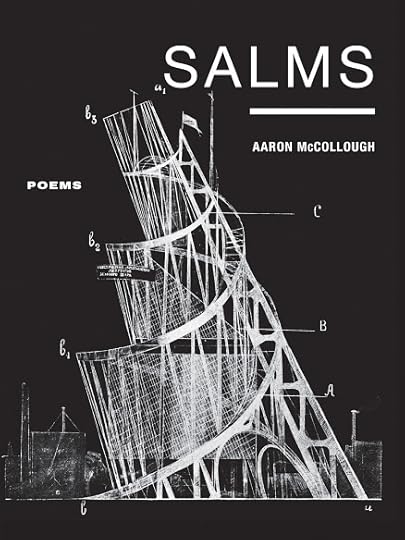

Aaron McCollough, Salms

Good morning, shadows

who love us, how we look,

the ripple

around the actual coastof our day

Without knowing our trueplace,

I pull at my face

Antenna feels thedistance

in an open door

Pure tension. Under gravity.

All of what we do issmall,

demoralizing.

I organized my day around

nothing, conjuringnothing,

and you actually appeared(“FIRST FORM”)

Tennessee poet and publisher Aaron McCollough’s latest is Salms (Iowa City IA:University of Iowa Press, 2024), published as part of University of Iowa Press’Kuhl House Poets series. I seem to be quite behind on McCollough’s work, havingonly sketched out a few notes on his third collection,

Little Ease

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2006) [see my review of such here], having completelymissed out, it would seem, on his Welkin (Ahsahta Press, 2002),

Double Venus

(Salt Publishing, 2033),

No Grave Can Hold My Body Down

(AhsahtaPress, 2011),

Underlight

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012) and Rank (Universityof Iowa Press, 2015). Where have I been, one might ask? Composed across foursection-clusters of short lyrics—“A MIRROR,” “SALM,” “THE SURVIVAL OF IMAGES”and “MERE”—with opening sequence “FIRST FORM,” the poems assembled across Salmssuggest themselves as a blending of poems, song and prayer. As Sally Keithoffers as part of her back cover blurb, Salms “[…] is as attentive tothe merging of poems and psalms as it is to the nearly indistinguishable soundof salms and songs.” Just listen to the music of the narrative in thecentre of the poem “The Wonderful Wood: A Mirror,” the opening of a series ofpoems with “A Mirror” suffixing or subtitling their titles:

Tennessee poet and publisher Aaron McCollough’s latest is Salms (Iowa City IA:University of Iowa Press, 2024), published as part of University of Iowa Press’Kuhl House Poets series. I seem to be quite behind on McCollough’s work, havingonly sketched out a few notes on his third collection,

Little Ease

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2006) [see my review of such here], having completelymissed out, it would seem, on his Welkin (Ahsahta Press, 2002),

Double Venus

(Salt Publishing, 2033),

No Grave Can Hold My Body Down

(AhsahtaPress, 2011),

Underlight

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012) and Rank (Universityof Iowa Press, 2015). Where have I been, one might ask? Composed across foursection-clusters of short lyrics—“A MIRROR,” “SALM,” “THE SURVIVAL OF IMAGES”and “MERE”—with opening sequence “FIRST FORM,” the poems assembled across Salmssuggest themselves as a blending of poems, song and prayer. As Sally Keithoffers as part of her back cover blurb, Salms “[…] is as attentive tothe merging of poems and psalms as it is to the nearly indistinguishable soundof salms and songs.” Just listen to the music of the narrative in thecentre of the poem “The Wonderful Wood: A Mirror,” the opening of a series ofpoems with “A Mirror” suffixing or subtitling their titles:One lived with hergrandmother who was not well. In a lonely

cottage she can’t go,nowhere to go and no one to send her.

Every space between peopleand things her hazard. The world

we find is notreassuring, certainly. Qualities, bodies, and time.

They were too poor, sothey hide in the cottage where they

earned their breadthrough piecework and spinning. The only

world. They worked withtheir hands in the cottage near a

wonderful wood no onedares go into.

Light reflected in the open stream

I’mintrigued by the heft of his prose poems, even across poems with line breaks orlook akin to more traditionally-set lyrics. These are poems of beginnings, eachallowing the unfolding unto anything and everything across a structure ofheartfelt singing, a musical lyric through the details of memory, childhoodrecollection, travel stories, ordinary moments and contemporary truths. “Visitinga friend of my mother’s in Atlanta,” the cool lyrics of “salm 12.13 resurrection,imperfect.” begins, “it was a boy I never / met again who showed me anillustration from one of his / father’s books depicting rear entry, saying that’swhat your / parents do, leaving me dismayed and lonely in my universe. // Andthen Bucky and I saw two dogs in a bend in the road, / and I thought so that’sit, and was calm.” Through McCollough’s lyrics, there is the depiction and thereflection, and how things are recollected, rooted and turned; how stories gettold, one might say. How moments are held, or displayed. “In a place famous forgreat wind / it turns on.” opens the short lyric “Wind,” a poem, nearly a dozenlines further, ends with the precise moment of this: “Until the fervor passes,and what’s left / is everyday still.” What is everyday, as he writes. Still.

January 18, 2025

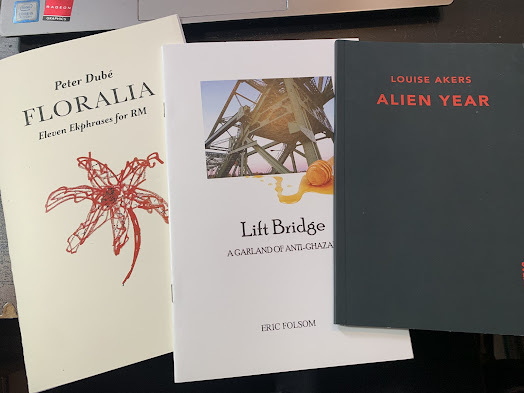

Ongoing notes: mid-January, 2025: Peter Dubé, Eric Folsom + Louise Akers,

Newyear, new round of chapbooks, as well as a mound I should still get throughfrom 2024. Will I ever get through? And don’t forget to catch new titles floating across above/ground press, as well as the new issue of

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]

. So much is happening!

Newyear, new round of chapbooks, as well as a mound I should still get throughfrom 2024. Will I ever get through? And don’t forget to catch new titles floating across above/ground press, as well as the new issue of

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]

. So much is happening!Montreal QC/Cobourg ON: Lovely to see Montreal writer and translator Peter Dubé’s new chapbook through Proper Tales Press, FLORALIA(2025), subtitled “Eleven Ekphrases for RM,” a note that references (on firstreading, as the chapbook is dedicated in part “in memoriam RM Vaughan”) the late Canadian poet, fiction writer, filmmaker and critic RM Vaughan (1965-2020)[see my obituary for him here]. Each poem floats across such lovely prose poems,some set in blocks while others in paragraphs, such as the poem “Easter Lilies,”that begins: “In imitation of orbit. In appetite for revelation. An exposure. Anunveiling. A pair of searching pools of light course with brutal regularity,descending from this pair of isolated towers: luminous raptors plunging fromthe peaks to scan a landscape. Each one as broad as a man’s reach, if eager toencompass what he sought. First one swirls by, and then the next.” I must havemissed the publication of what his author biography offers, “his most recentwork, a novel in prose poems entitled The Headless Man (A Feed Dog Book/AnvilPress, 2020),” a title I’m now curious about; edited as well by Stuart Rossthrough his imprint at Anvil Press, the book was apparently shortlisted for boththe A.M. Klein Prize and the ReLit Award. As Dubé offers as his “Author’s Note”at the end of FLORALIA:

The body of workcollected here, as a series of ekphrastic poems, is one effort to bringtogether my practice as a poet and my years of work as an art writer. The poemswere composed using a personal, indeed idiosyncratic, method combing Gold Dawn-stylescrying with surrealist automatism in order to capture or create a particularaesthetic space and moment.

The RM in the title,appropriately enough, also brings together two figures in a single form. Thefirst RM is, clearly, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, an artist whosework has long been an interest of mine and whose well-known flower photos arethe inspiration for this sequence of prose poems. The other RM is my dear,late, and much-lamented friend RM Vaughan, with whom I shared many discussionsabout writing, art, magick, the complicated relationship between them, and manyother topics. (We were both chatty types…) This chapbook is written partly in hourof your friendship, and in memory of those exchanges.

Kingston/Ottawa ON: I’m frustrated I missedthis chapbook by Kingston poet (and first Kingston poet laureate) Eric Folsom,his Lift Bridge: A Garland of Anti-Ghazals (Ottawa ON: catkin press,2020), as I had long ago produced (and even ran a second printing) of anti-ghazalsby Folsom through above/ground press, his NORTHEAST ANTI-GHAZALS(2005/2011). The notion of the English-language variation on the Urdu form ofthe ghazal has run through Canadian poetry for decades, prompted by JohnThompson’s posthumous Stilt Jack (Toronto ON: House of Anansi Press,1978), with a further thread of “anti-ghazals” begun through Phyllis Webb’s Waterand Light: Ghazals and Anti-Ghazals (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1984) (bothof these works in full can be seen through each of their still-in-printcollected volumes, from Thompson’s through Goose Lane Editions and Webb’s through Talonbooks). Set as the “anti-sonnet,” the English-language play on theghazal usually works incredible distances in narrative between couplets, and I wouldbe curious to hear Folsom’s thoughts on how he approaches the form (especiallyone he’s been working on, occasionally, for such an extended period of time),from ghazal to anti-ghazal, stretching his narrative out across couplets, aleap of thought in that single open space between them. His poems offer poemswithout excess, each sequences of narrative straightforward lyrics that allowfor that open space, where the poem truly begins to set.

MAY POSSIBLY

Grind coffee finely, pourpowder from the grinder’s bowl,

Tip the mill and tap,wipe the inner surface clean.

Empty this head of despairand pretension, shut down

The surly old voices andlisten to what’s really outside.

What if I replace thisbad feeling with colour, replace

The colour with sound,then write down the sound?

Broad lapels on oldjackets, tulip petals flopping open,

The baby knuckles oflilac buds uncurl like newborn hands.

The green leaves of grassspear the hurricane fence;

Your voice singing, thefloorboards creak in counterpoint.

My dreams wordlesslyrepeating, desire your dreams

Take shape like rockcandy crystalizing on string.

Columbia SC: Winner of the 2020 Oversound Chapbook Prize,as selected by Brandon Shimoda, is Alien Year (Oversound, 2021) byLouise Akers, a Brooklyn-based poet that appears to have published a fullcollection since, ELIZABETH/THE STORY OF DRONE (Propeller Books, 2022)that I’d be curious to get my hands on. There’s a subtlety I’m enjoying inthese short pieces; an ease, one that allows for a sharp, quiet wit and seriesof turns. “I find it hard to believe I am going to die,” she offers, to openthe poem “THE PASSION,” “an animal in an accident rich environment: / a priorifoundation, a limited / foundation.” Her turns offer straightforwardness butare anything but, providing a clever density of lyric thought that requiremultiple readings, even across a clear sense of music across each line.

AS SEQUELS

For us while longing,

no single horizon canremain

distinct. Science topped

/pummeled

into patience becomestorture.

The self retreats

to the position of hell,

which I don’t find verybrave,

despite its warmth.

As for dying, I know you.

We will live,

patiently as taxonomicalstrangers,

losing all reality assequels

to your silence.