Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 28

January 17, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Stephanie Cawley

StephanieCawleyis a poet in Philadelphia. They are the author of

No More Flowers

(Birds, LLC) and

My Heart But Not My Heart

(Slope Editions). Recentpoems have been published in Protean, Prolit, and the tiny.More at stephaniecawley.com.

StephanieCawleyis a poet in Philadelphia. They are the author of

No More Flowers

(Birds, LLC) and

My Heart But Not My Heart

(Slope Editions). Recentpoems have been published in Protean, Prolit, and the tiny.More at stephaniecawley.com.1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Mybooks have felt like an outward materialization of what I had been orienting mylife around and towards for a long time in a sometimes more private or interiorway. That’s a sideways answer. I guess I think life changes and books are partof life so they both do and don’t change a life. My second book is in many waysvery different from my first, because the first is a kind of enclosed,contained sequence written out a specific period in the aftermath of myfather’s death, while the new book is a collection of more individual poems andis a little bit more sprawling. But I think it is obvious that the same personwrote them, even though in some ways I’m not really the same person.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Ilike thinking of myself as a poet first, as someone working in the field ofpoetry, because it feels so expansive, and so concerned with the material oflanguage itself. I’m aware that the other fields are expansive and concernedwith language, too, and that this is likely just my own baggage andassumptions. A lot of what I write is in prose. I have difficulty with the ideaof writing fiction because I have trouble with the ideas of narrative andcharacter and plot, but I suspect this is also a me problem.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Iam not particularly project-oriented, usually, though there have been timesI’ve set myself some constraints or committed to a particular experiment. I dotend to write poems kind of quickly, kind of all-in-one-go. I’m saying that butlately I’ve had some poems I’ve written in pieces over a period of a few weeks,so maybe it’s not true anymore, or right now. And often I have to let a poemsit around for a long time before I can decide if it’s worthwhile, or make thesmall changes needed for it to be finished. I also produce a lot of writingthat isn’t very good or that I know will go nowhere. Or it points towards thenext attempt, or helps me work something out that clears the way for the nextattempt, perhaps. So in that way, it is also a slow process.

4- Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Apoem is often preceded by a certain kind of itchy poem-feeling that arises. Ioften write poems while reading, putting a book down to write, or thepoem-feeling emerges while I’m in transit. In terms of process, though, I feellike as soon as I have a grasp on a given process or method for myself, itchanges. Historically, I have liked to give myself a lot of spaciousness aroundwhatever it is I am writing, letting myself make things without necessarilyknowing where they are heading. Then the process of shaping those things into abook is a more deliberate sitting down with whatever I’ve accumulated andfiguring out if there’s a book to be made from the mess.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ilove doing readings, though I’m not an especially performative kind of reader.I like that readings can be a space to sort of test out new material, orincentive to finish something new in order to share it. And then you can learna lot from how it feels to put a poem out into the air for others to hear.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Ionce said, in a poem “I have no / theoretical positions to explore / in thispoem. I have no ideas about / anything.” In a more recent poem, I wrote “I hadno ideas / and my ideas got better / the fewer of them I seemed to have.” Ofcourse, writing about having no ideas is itself articulating a sort oftheoretical concern about the relationship between ideas and writing, orwriting and life itself. That sounds very abstract. I guess I can tend towardsbeing a kind of bootleg philosopher. I’m interested in writing, feelings,ideas, love, desire, despair, the future, and film. And my questions aboutthose things are like, what even are those things? How do we stay alive in aculture committed to the destruction of human life? How can we find anythinglike freedom?

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Idon’t think writers are that special in terms of their role in the culture. Byculture I guess I am thinking of and generally preoccupied by the realm of the“political.” I think there is much more risk in writers thinking their writing“achieves” something in and of itself as an exertion of a desire for changerather than thinking about how to use their human time, energy, and resourcestowards that end more directly. I have just finished reading Ben Davis’ 9.5Theses on Art and Class, which I found really interesting and useful inarticulating this entangled relation between the artist and the “world.” Allthese terms feel kind of insufficient. And I do also believe in the kind ofmysterious potency of art to transform the world, or the culture. I just don’tthink that’s so literal, or straightforward, or obvious. And I think a lot ofwriters, particularly those in academia or with money, seem frankly divorcedfrom the material reality of life for most people in this country and world,but see themselves and their lives as contributing meaningfully to someabstracted “cultural” realm that transcends that world, which I find reallytroubling. Recently I found myself being kind of hard on myself for strugglingto write, and I was like well I live in impossibly horrific conditions andtimes for human life: maybe struggling to make art in such conditions is reallynot an indicator of my personal failing. But I do believe in struggle, andfailure, and persistence. I don’t know.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Iloved working with Sampson Starkweather, one of the editors for Birds, LLC, whoworked with me on No More Flowers. Other than with friends, I have neverhad such a fruitful and open editorial relationship, where I felt like I couldshow him some of my messy half-starts and see what he thought should go or notgo into the book. It made the book better, and more interesting, to have aneditor who I knew could see what I hoped the book could be, and figure out howto help it become richer and wilder.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Idon’t know why but I cannot come up with an answer to this question. Maybe I’mopposed to blanket advice.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to hybridwriting)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ithink a lot of my writing is animated by rhythm, and sometimes that rhythm isoperating on an engine driven by the sentence, and thus emerges as prose, andsometimes driven more by lineation or fragment. So it’s just a matter of tuningin to the frequency a certain expression seems to be asking for.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’mcurrently still getting adjusted to a new rhythm and routine with a new job.Previously, I have not been particularly routine oriented, except I have hadlong stretches of time (years) where I have written poems at 11am on Sundaymornings in writing groups with friends. I’m glad for that standing commitmentto time for writing. Otherwise, my daily habits are pretty erratic so I try tocarve out larger blocks of time when I can. With my new job, I’d like to beable to read and write a little before work sometimes, but that’s an endeavorfor a little later on.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

UsuallyI just need to take the pressure off. Read, watch movies, see friends, takewalks, let the writing sort itself out.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pinetrees, the ocean.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Iwatch a lot of movies, which appear in my writing quite a lot in direct ways,but I also think of them as useful for thinking about structure, texture, andtone.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Mystandard answer to this question is usually Alice Notley, because I admire herlifelong commitment to poetry, and the wide-ranging and shifting nature of heraesthetic and intellectual development. I find similar inspiration in , whose films are often reduced to tropes but who, I think, has beenusing his films to approach a set of questions about human life and the body ina much more wide-ranging and interesting way than he is often given credit for.I find that kind of sustained investigation really inspiring when thinkingabout how to have a long life in writing. There are many others. The list islong, but I don’t like to make one for fear of who I might accidentally leaveout.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Ireally would like to write a novel, to find out what my version of that wouldlook like.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Iguess I don’t necessarily think of writing as my “occupation.” It feels like Iwas sort of bound to be some kind of writer, no matter what. There was analternate trajectory for my life when I was young where I could have becomemore serious about music. I think I wanted to write film scores, but I mighthave actually liked being a piano teacher. Instead, I have spent a lot of myworking life teaching, but even that has been inconsistent. I recently startedin a new line of work as a paralegal, which so far I quite like. I like beingvarious in many parts of my life, but my writing life is really kind of theconstant. I try to think of it always as the larger project, even thoughmaterial reality at times makes that difficult to do.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Iloved books from the time I was very young. I wrote a lot, often justprivately, from a very young age as well. I think I like that writing is aquiet, private creative practice, and that you can take it with youanywhere.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Themost recent true greats are Margery Kempe by Robert Glück, and a rewatchof Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, but I also watched Robert Altman’s 3Women for the first time a few weeks ago, so I’ll slide that in.

20- What are you currently working on?

I’vebeen more seriously trying to get to a place where I feel finished with amanuscript mainly of fragments that I’ve been working on off and on for 4-5years now, which may never go anywhere but I need to finish so I can stopthinking about it. Other than that, trying to find my footing writing new poemsagain in what feels like a new season of my life.

January 16, 2025

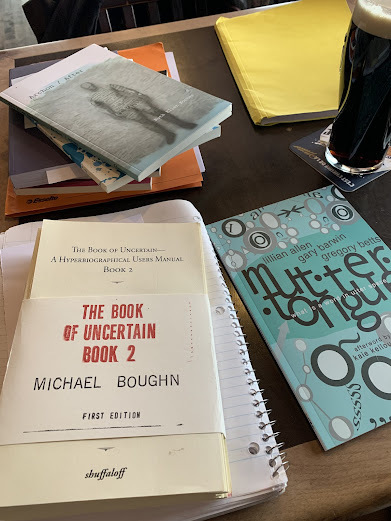

Michael Boughn, THE BOOK OF UNCERTAIN BOOK 2

Tropos remains a matterof immaterial

condensation turns the poemagainst the current

tattered grimace peersbetween cracks

in the Mall’s magisterialfaçade mutters

glory and grace can beyours as well

as that three-dollarArmani shirt Progress

delivers from tinyforeign hands to your

doorstep

Away borders onleaves

seasoned with pulsion’sdirection

as restless negativity,not to haggle

over minor inflections

but to indicate bentphilosophical

familiarity and Hegelian digressions

through back-and-forthinterruptions

sometimes mistaken fortropological

ontologies’ second cousin

twice removed (hereincest reveals

blurred edges leadintrepid

into mansions of theNight

and surprise’s incubation

lost in words’ headstrongconnections

this way, that cave theRiver Alph

pours from, whereuncertain still leads it in

spike of Porlockian Interference|

Patterns universaldowner) (“Tropological Ontology / of Uncertain Emotions”)

I’lladmit I’ve seen but a scattering of titles by Toronto poet and critic Michael Boughn over the years, from his incredible collection of essays,

Measure’sMeasures: Poetry & Knowledge

(Barrytown NY: Station Hill Press, 2024)[see my review of such here], to poetry collection

Great Canadian Poems for the Aged, Vol. 1

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2012) [see my review of such here],as well as the chapbook The Battle of Milvian Bridge (shuffaloff, 2021)[see my review of such here], not to mention his chapbook

In the shadows

(2022) that I produced through above/ground press. Whenever I do encounter hiswork, I’m always curious why it hasn’t received more attention than it has,Boughn somehow sitting as one of our unheralded senior Canadian poets andthinkers. Wrapped together as eleven chapbook-sections and pamphlet coda is THEBOOK OF UNCERTAIN BOOK 2 (2024), the first edition of which is produced ina hand-numbered edition of twenty-five copies (mine is number twenty-five). Subtitled“A Hyperbiographical Users Manual,” this book-length assemblage follows THE BOOK OF UNCERTAIN BOOK 1 (Brooklyn NY: Spuyten Duyvil, 2022), and extendsacross eleven sections, each of which are set in their own numbered chapbook-binding—“TropologicalOntology of Uncertain Emotions,” “Uncertain Micro-Politics in Pirate Utopias,” “UncertainWave Functions in Local Populations,” “The Box of Uncertain,” “The Box ofUncertain: Subsequent cats/

I’lladmit I’ve seen but a scattering of titles by Toronto poet and critic Michael Boughn over the years, from his incredible collection of essays,

Measure’sMeasures: Poetry & Knowledge

(Barrytown NY: Station Hill Press, 2024)[see my review of such here], to poetry collection

Great Canadian Poems for the Aged, Vol. 1

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2012) [see my review of such here],as well as the chapbook The Battle of Milvian Bridge (shuffaloff, 2021)[see my review of such here], not to mention his chapbook

In the shadows

(2022) that I produced through above/ground press. Whenever I do encounter hiswork, I’m always curious why it hasn’t received more attention than it has,Boughn somehow sitting as one of our unheralded senior Canadian poets andthinkers. Wrapped together as eleven chapbook-sections and pamphlet coda is THEBOOK OF UNCERTAIN BOOK 2 (2024), the first edition of which is produced ina hand-numbered edition of twenty-five copies (mine is number twenty-five). Subtitled“A Hyperbiographical Users Manual,” this book-length assemblage follows THE BOOK OF UNCERTAIN BOOK 1 (Brooklyn NY: Spuyten Duyvil, 2022), and extendsacross eleven sections, each of which are set in their own numbered chapbook-binding—“TropologicalOntology of Uncertain Emotions,” “Uncertain Micro-Politics in Pirate Utopias,” “UncertainWave Functions in Local Populations,” “The Box of Uncertain,” “The Box ofUncertain: Subsequent cats/Boughn’sis an extended and packed lyric sentence of collaged language, reference, soundand influx, a poetics reminiscent of Toronto poet Stephen Cain’s recent Walking &Stealing (Book*hug Press, 2024) [see my review of such here], but with afar denser language and heft of materials. “Midden heap / of nothing’sdiscarded remains,” he writes, in the first section of the fourth poem-chapbook,“layer // after layer after layer has already / signified more than decencywould have / circulate in polite company , a normative / exclusionary sig-fixdesigned to keep power / well-contained and ordered according / to bleachrequirements […].” There is just so much happening, so many simultaneousdirections, to his ongoingnesses through these lines. As he spoke of the project,then still very much in-progress, as part of an interview for Touch theDonkey in 2019:

Well, this is really thecrucial question facing us at this moment of intensifying crisis. Modernitydestroyed a mode of being-together that was an intimate proximity, both toother people, to other animals, and to the divine. It wasn’t idyllic by a longshot. It was by all accounts brutish, violent, and horribly intrusive. But itwas a different mode of being-together than what awaited us in the cities.Living cheek by jowl, we insulate ourselves from the people who live closest tous for privacy, where the only animals we ever encounter are domesticated pets,where our meat is purchased in cellophane wrapped packages, and where thedivine, as Jean-Luc Nancy put it, no longer flutters except exsanguinate andgrimacing.

What’s missing isbelonging in a human sense of being-together. We struggle to live among thewold vagaries of vast markets, including labour markets that force people intomotion all the time. Witness what just went down in Oshawa. Society is a placeof probabilities and statistically verifiable behaviours among alienatedindividuals determined by a set of social imaginary significations and governedby imposed norms. We are seeing the result of that process that has been goingon now for some 500 years in the rise of reactionary populists like Trump andBolsonaro who are able to exploit that deep alienation by creating a “movement”in which people experience a sense of belonging to something with others whoalso belong – a being-together, but one that is finally based on exclusion andviolence against those who don’t belong.

I’mintrigued by the potentially-endless ongoingness of such a project as this,even before the consideration of this as a second volume, and makes me curiousas to see what that larger arc of his published work actually looks like. Shouldsomeone be working on a selected poems of Michael Boughn? And how far might thiscurrent work extend, whether to a BOOK 3 or beyond? As part of the sameinterview, he speaks of his larger, ongoing work, saying: “Well, it’s reallyall the same work, ever since Iterations of the Diagonal back in 1995.It’s the work of finding ways to weave the complexity and mystery of beingherein language.” Of language itself, one might say. Of being in that exact, singlemoment, however many languages and gods may have been or have ever been. Or, asthe final poem in the collection, the coda-pamphlet “Numinosum Aftermath”reads:

but in the difference

lies soul’s challenge toembrace

what’s beyond yet withinit, what we bring

to it as it is brought tous, light and dark,

seen and unseen, knownand unknown

twists us around being’spoles, flings us

willy nilly into the roilof common day

where we catch a glimpseof a new world

in confusion’s pain andgrief

and are surprised by thegreeting

of a stranger

who is us

January 15, 2025

Fast-Vanishing Speech: The 2023 Douglas Lochhead Memorial Book Arts Panel: Jim Johnstone, Klara du Plessis and Christopher Patton, with an introduction by Lisa Fishman

When a book ora poem or essay or performance has already been made, are there ways for it tokeep changing, so to speak, in part by means of being thought about, spokenabout, written about, overhead by others? We know that the answer is yes, andthat criticism is one word for that process, even if cultural space formeaningful criticism seems to be shrinking. A practice discussed at length bythe panel is curation; each writer approaches curation in ways likely toexpand and refresh one’s sense of what critical engagement is. When AndrewSteeves sets type as a printer and publisher, when Jim Johnstone reviews abook, when Chris Patton exhibits fragments of a text written by a person whowas once alive, when Klara du Plessis creates the conditions for a new text orexperience to be made by way of bringing writers together to share their workin unforeseen ways (her name for this is Deep Curation) – when any suchendeavours are undertaken, work by someone is brought forward to be encounteredby someone else. Curation lays the ground for conversation, critical inquiry,collaboration, and – as the panelists light upon with palpable hope –community. (Lisa Fishman, “INTRODUCTION”)

Irecently caught a copy of Fast-Vanishing Speech: The 2023 DouglasLochhead Memorial Book Arts Panel: Jim Johnstone, Klara du Plessis andChristopher Patton (Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2024), originally curated asone of the Wayzgoose Talks via Gaspereau Press, the full list of which isincluded at the back of this collection. “At the annual Gaspereau PressWayzgoose,” the collection cites, “authors Jim Johnstone, Christopher Patton,and Klara du Plessis were invited to discuss the topic of Literary Criticismand Curation by their publisher, Andrew Steeves.” Have publications beenproduced of every talk-do-date? It would seem a very Gaspereau thing to do,certainly. Either way, I would hope that transcripts of such might beavailable, somewhere, as a kind of checking-in on how various writers, curators,thinkers etcetera are considering their craft. As Steeves began theseparticular proceedings: “I think the best place to start would be for all of usto just locate ourselves. Briefly, in what way do each of you write aboutwriting?”

Irecently caught a copy of Fast-Vanishing Speech: The 2023 DouglasLochhead Memorial Book Arts Panel: Jim Johnstone, Klara du Plessis andChristopher Patton (Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2024), originally curated asone of the Wayzgoose Talks via Gaspereau Press, the full list of which isincluded at the back of this collection. “At the annual Gaspereau PressWayzgoose,” the collection cites, “authors Jim Johnstone, Christopher Patton,and Klara du Plessis were invited to discuss the topic of Literary Criticismand Curation by their publisher, Andrew Steeves.” Have publications beenproduced of every talk-do-date? It would seem a very Gaspereau thing to do,certainly. Either way, I would hope that transcripts of such might beavailable, somewhere, as a kind of checking-in on how various writers, curators,thinkers etcetera are considering their craft. As Steeves began theseparticular proceedings: “I think the best place to start would be for all of usto just locate ourselves. Briefly, in what way do each of you write aboutwriting?”Forthose unaware, Klara du Plessis has been engaged for some time with what sheterms Deep Curation, an absolutely fascinating curatorial structure shediscusses as part of this conversation. As part of the panel, she offers thather sense of the term “literary curator” “[…] includes my more recent andongoing project, Deep Curation, that experiments with collaborative poetryperformance and centers the poetry reading as more than a vehicle for disseminatingpublished texts, as an artform in its own right. In my academic work, I’ve beenthinking a lot about the kind of labour that goes into organizing poetryreadings (like the ones we saw here today). It’s very under-valued andunder-theorized work. Both in the practical and theoretical sense, for me, thisliterary curatorial work is a form of thinking about and enlivening writing. Thiswork becomes an analysis, whether I engage with more traditional scholarlyforms or not.”

Theensuing conversation floats easily through and across literary curation as eachparticipant sees such, specifically around each of their individual practices, muchof which begins to overlap, in quite interesting ways, one I dearly wish I couldhave attended in person. So much of this work, this community effort, is beingattended by multiple across the country, so any kind of deep dive into the conversationaround such is essential, especially given the rarity of such conversation. It isone thing to say there aren’t enough reviews, for example, but then even fewerare discussing the arguments and ethos of reviewing, let alone anyconsideration of literary curation, from editing books and chapbooks to writingreviews or essays and organizing and curating literary readings. “When we’retalking about curation,” Johnstone says, near the end, “we’re talking aboutfiltering noise. There are a lot of people who write, and there’s a lot ofwriting waiting to be published – a good curator can get a community excitedabout what’s happening. They can bring voices into perspective in a way thatmakes you want to hear them.”

January 14, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Deirdre Simon Dore

Deirdre Simon Dore is a Canadianwriter. Her short fiction has won, among other awards, The Journey Prize andhas been published in numerous journals and translated into Italian. Her playshave been produced in Vancouver and Calgary. Originally from New York and agraduate of Boston University, she has an MFA in creative writing from UBC.After homesteading on a remote island in BC, she moved inland where sheacquired a woodlot license on which she planted trees and learned to use achainsaw. She lives near a large lake in the interior of British Columbia withher husband, black lab and assorted livestock. She has two children.

1 - How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Funnily enough, Iwas just thinking the other day: There I was, with some writing experience inother genres, finally tackling the novel. Years I worked on it. Writing,revising, editing, notes, outlines, storyboards, etc…then seeking out apublisher, editing and revising again and finally looking forward to thepublication date like the best Christmas ever. But then? What changed? Basicallynothing. Lol. Except to say there have been some strange reactions to the workfrom people very close to me. So maybe my life did change a little and I’m alittle bit hoping to change it back. Enough said on that.

2 - How didyou come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Well first was avery short living autobiography, followed by playwriting, followed by poetry,followed by short fiction, followed by screenplays and then the novel. If I hadended up a journalist or lawyer or space engineer I might have worked innon-fiction but I studied psychology in school and I think that an interest inpeople and what makes them tick is why I gravitate to fiction.

3 - How longdoes it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Depends. Bothquick and slow. Sometimes initial drafts are very close to the final shape andsometimes vastly, hugely different.

4 - Where doesa work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I have not turnedshort pieces into a larger project though I wonder sometimes about trying that.This first novel, plus the one I am working on now were/are earmarked to benovels at the outset.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I have done acouple of readings at my local library and was gratified to get positivefeedback. That’s a good feeling and encouraging.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

(a playwright) once wrote to me in a letter that these sorts ofquestions are ‘afterwords’ sort of questions and not something he worries aboutwhen he starts writing. I think I feel about the same.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I’m leery ofputting the writer in such a box. For me the role is simply to bear witness tolife.

p.s. Justliterally moments after I came up with that answer to this question I opened atrandom a Deborah Levy book I had not read yet and found this quote by Georgia O’Keeffe: “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’syour world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else.” NYPost, May 16, 1946

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

Love working withan outside editor. Especially if they are fans of the draft. I think it wouldbe depressing if they were not.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I don’t know ifthis qualifies as the ‘best’ piece of advice I’ve ever heard but once, yearsago, my father said to me “Don’t be afraid to put sex in it.”

10 - How easyhas it been for you to move between genres (short stories to plays to thenovel)? What do you see as the appeal?

Poetry gives youan appreciation for the economy of words, for the value of imagery andmetaphor, for the beauty of language. Playwriting gives you dialogue andcharacter. Short stories give you emotional snapshots and also character.Novels are all that and long.

11 - What kindof writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

Before we hadlots of critters to tend, I would write first thing in the morning uponawakening, with a cup of coffee in my hand. Now I have to feed the ducks andchickens and let the geese into the pond and walk the dog first. Before evencoffee. By then I’m ready to sit at my computer and do a little work. But -walking the dog - a lot of ideas come then.

12 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

I have some booksthat I like to read, to help with tone or inspiration, from authors likeOttessa Moshfegh and Donna Tartt. I also like to just put it all away, anddream about it, or walk mindlessly in the woods.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of thespring blossoms of cottonwood trees puts me squarely back in the valley where Ispent many years of my life. And then there’s a particular smell ofblackberries that puts me in England. Not that I’m from England but I haveroots there.

14 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Not really, I’m prettymuch in the McFadden camp on this one.

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I have a list ofwriters that I love, it’s on my website – deirdresimondore.com

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like toorganize all my sketchbooks in one place. And all my journals. And destroy theones that I don’t want hanging around.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

This is anoccupation which I actually have a little experience in, and that is live lifeas a cowboy. I would hope for a really good horse.

18 - What madeyou write, as opposed to doing something else?

Living for manyyears in a rural, somewhat isolated situation, writing became my interestingother reality. Kept loneliness and boredom at bay.

19 - What wasthe last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last greatbook I read was Daughter, by Claudia Dey.

The last greatfilm? Well, how about a series – The Money Heist. Loved that series!

20 - What areyou currently working on?

Thank you forasking. I’m working on a second novel. My first was female and plot driven –this one has male protagonists and I’m trying to steer it more towards character,maybe less plotty. It’s about letting them make their own choices I guess.

January 13, 2025

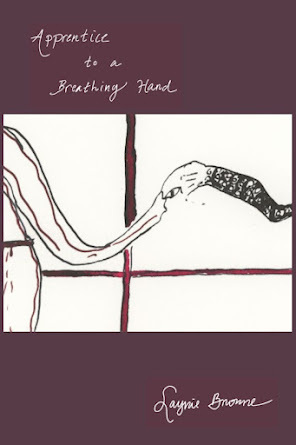

rob mclennan : Interview with Laynie Browne

My interview with Pennsylvania poet Laynie Browne, focusing on her forthcoming

Apprentice to a Breathing Hand

(Omnidawn, 2025), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her latest here, and her three prior here.

My interview with Pennsylvania poet Laynie Browne, focusing on her forthcoming

Apprentice to a Breathing Hand

(Omnidawn, 2025), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her latest here, and her three prior here. January 12, 2025

Spotlight series #105 : Conor Mc Donnell

The one hundred and fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell

.

The one hundred and fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell

.

The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau, Indiana poet Nate Logan, Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn, North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson, award-winning poet Ellen Chang-Richardson and Montreal-based poet, professor and scholar of feminist poetics, Jessi MacEachern.

The whole series can be found online here .

January 11, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tracy Wise

After an internationalchildhood lived throughout Asia because of her father’s non-profit aid work, Tracy Wise has spent her career in theatre, opera, and then higher educationadministration. She currently writes university presidential speeches, campuscommunications, and news stories in California’s Inland Empire. She has a BA inTheatre and Spanish from Washington University in St. Louis (which includes ayear at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK) and an MA in CulturalStudies (a historiography degree) from the University of East London in the UK.A life-long passionate reader, she designs social media for the Friends of herlocal Redlands, California A.K. Smiley Public Library in her free time. Facebook: Tracy Wise, Author and Freelance Writer

1 -How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

MADAME SOREL’S LODGER, to be published by TypeEighteen Books in February 2025, is my first work to be published.So, watch this space! It is incredibly exciting to see my creative (as in,non-work related) writing entering the wider world.

2 -How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I’vebeen writing stories my whole life, and so fiction is the space in which I feelmost at home. There’s a type of discipline for writing poetry which I simplylack. I know there will be somenon-fiction in my future (apart from my day job), but I don’t feel ascomfortable in it as a form of creative expression.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Itend to start writing and see if the story continues to call me forward. Ibasically have a sense of where the story is going, but what happens along theway is part of the daily discovery. To get started on a project, I need themental space to be open to it. Once the opening is there, it tends to continueuntil it says, I’m done.

4 -Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Itis not a fixed thing for me. Projects may start as a short story and then say,there’s more here, keep going. Or not. Or they may emerge from the first as afull novel.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ilove reading out loud. I’ve done it my entire life and used to record storytapes for my younger cousins and then their children when they were small. Ihugely enjoyed recording the audiobook for MADAME SOREL, for instance. But Ihave yet to do a public reading of my creative work (apart from in writer’s critiquegroups)—am looking forward to diving in.

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Ifully believe writers need to be alive and aware to the current moment,including concerns about racism, sexism, misogyny, and anti-LGBTQIA issues, aswell as to issues around the question of appropriation. That being said,writers also need to be free to write. I believe that writers can tap into thatwell of creativity which is part of our common humanity, and that should becelebrated and supported.

For example, in MADAME SOREL’SLODGER, the central character who I simply name “the Artist” is trying to pullall of life down onto a painted canvas, so that the canvas comes fully alive. Iam striving to create a vivid experience for my reader using letters on a flat,white page or screen, so that this world and its characters come fully alive.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Thewriter is a fellow human being in the larger culture and, therefore, they haveas much right as anyone else to speak up. If they are published and well known,it can add weight to what they say in the public square and who is willing tolisten to them. Perhaps I am an idealist, but I believe informed thoughtfulnessand considered reflection can promote discussion and can strengthen us as aculture and as a society. Did I saw I was an idealist?

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Inmy view, a writer always needs an outside pair of eyes on their writing (aka, aneditor), the same way that an actor always needs an outside pair of eyes ontheir performance (aka, a director). We need another perspective, becausegetting lost in our own head can weaken what we are trying to do. So, yes, itis essential.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Thereare no rules when it comes to writing. Write. And read-read-read-read-read.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to news storiesand speeches)? What do you see as the appeal?

Writingis how I best express myself, so moving from fiction to press releases tospeeches is natural to me. That is, once you understand the “feeling,” format,and intention of each “mode,” it becomes an easy switch. And it all provides anopportunity to hone your writing. No effort is ever truly lost. Honestly, Icredit my years spent on Twitter as providing an excellent training ground fordistilling what I want to say into as clear and concise a statement aspossible.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

WhileI dream of having a set, orderly routine (just as I dream having a tidy,minimalist, organized house), I have come to the realization that I will alwaysresist that. I am very Type A—I map each day out, with all my tasks, deadlines,and goals, and then set to work getting them done. Which then also involvesrearranging like mad as the day throws new things at you.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Forme, the biggest hurdle is carving out both the time and the headspace to letthe creativity free. I tend to overschedule myself.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Mycollege roommate was from Pakistan, one of the places where I grew up as achild. I came back to the dorm late one night after a theatre rehearsal. It waswarm and humid, and she had the window open, the lights off, a couple ofcandles burning, and some Pakistani music playing softly. I opened the door andI was enveloped by the sound, the sight, and the smells, and I did not knowwhere or even when I was. I have never forgotten that moment.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Honestly,for me, everything I do is somehow connected to music. When I am writing, it isthe rhythm and cadence of the sentences as well as the sounds of the wordsthemselves which I listen to. And I also want to put clearly down on paper thescenes I am seeing in my mind so the reader can see them, too. But all of that is also informed by alifetime of being read to and then, from the age of 6, reading ferociously onmy own.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Thereare so many incredible writers out there, it is hard to narrow it down. As achild, poetry was hugely important for me. A childhood writer I loved was Joan Aiken. Recent discoveries include Sarah Winman and Alice Winn. Maggie O’Farrell’s THE MARRIAGE PORTRAIT moved so well into the mind of an artist andmade her come alive, which added a whole other level to the impact of Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess” for me. I have loved Barbara Pym’s novels agreat deal. Also, Robertson Davies has been very influential. Edward Carey’s LITTLE really spoke to me—the rhythms of his writing in the novel conveyed thestrangeness and familiarity of fairy tales. Julie Otsuka’s ability to pack sovery much into her short novels seems extraordinary to me—you get lost in herworld and think you’ve been gone for hours, but you haven’t been. And Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ THE LOVE SONGS OF W.E.B. DUBOIS was just incredible (you cantell she is a poet in how she constructs her sentences and tells her story). Thereare also some amazing non-fiction writers in history and philosophy—I read alot of history these days, especially in the years since I earned my M.A. Iknow I will leave someone off whom I love…

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Ialways knew I wanted to write, but I also knew I wanted to perform. I decidedto do the performing when I was younger and spent several years as an actressand then an opera singer (the first was something I had only dreamed of and thesecond I had never dreamed of; getting to do both was magical). I am revelingin my opportunity now to finally give time and attention to my writing.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Ido wonder what it would have been like to have gone fully into academia and theprofessoriate, instead of just dabbling around the edges (I call myself a“closet academic”). I also wonder what it would have been like to have goneinto the non-profit aid work my father did or into the diplomatic service.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writingis like breathing for me. I tried balancing it with my full-time work when Iwas living in Chicago but woke up one night just before my head hit thekeyboard. I couldn’t afford to quit my day job at that time, so regretfully hadto put it all away. So, it feels like coming home.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Thelast non-fiction book I really appreciated was Sebastian Smee’s PARIS IN RUINS:LOVE, WAR, AND THE BIRTH OF IMPRESSIONISM. The last fiction book I really enjoyed was Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel’s DAYSWORK: A NOVEL and now I am re-thinking Herman Melville. I confessthat I have largely stopped watching films, after a lifetime of being an avidfilmgoer, and I am looking forward to that switch being turned on again.

20- What are you currently working on?

Ihave lots of ideas! When you put off doing something for so long and then yousay, okay, it’s time, everything that has been in the back of your brain jumpsup and says me-me-me-now! I have completed the first book in a trilogy which isagain literary fiction and that flirts with the Regency trope and format butmoves away from it at the same time. I have an idea around the years I spentcaring for my mother through her dementia. And I have some ideas based on myrather itinerant and international lived experience.

January 10, 2025

Matthew Gwathmey, Family Band

FAMILY BAND

What was there to do butto play music?

Me on guitar and mysister on fiddle.

Father came out aftertuning to blow

The porch top off withhis harmonica.

Then a second cousin, onseeing shingles

falling sure onembouchure, would bring

his five-string banjo,mumbling about picket

fences, Double Dutch and potlucksuppers.

Singers, we always hadlots of singers.

Back in the house, nextdoor, up in the hollow.

Singers we couldn’t hear.Singers we didn’t want to.

Our songs turned outgrief lessons:

“The Little Lost Child,” “O Molly My Dear,”

“How Can We Stand SuchSorrow,” “Bury Me

Under The Willow Weeping.”

Nothing in return butquick toe taps

and off-beat claps, nexttune chosen

by the fastest caller. Thatis,

until a few of our auntscame,

right hands flicking withrulers,

and made us all sing gospelhymns,

about life after life after.

Thethird full-length collection by Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, following

Our Latest in Folktales

(London ON: Brick Books, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Tumbling for Amateurs

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023) [see my review of such here], is

Family Band

(Guelph ON: The Porcupines’Quill, 2024). There’s long been a playfully-askance approach Gwathmey has takenblending formal elements of lyric and narrative, and this collection is nodifferent, offering sharp lines across a folksy, familial and detailedbackdrop. “2022 is the year of the lilac,” he writes, to open the poem “LILACS,”according to the almanac. // So tonight let’s walk the trail behind our house.// To the bushes growing in very great plenty and already divided. // Find anoffshoot. Plant it in our side yard where it scent can flourish / in the fullsun. // Water and wait. We’ll alternate scions with random grafts, // until itsflowers appear at eye level, appearing just before summer / comes into season,// blooms lasting only a couple weeks.” Through short, sharp lyrics, Gwathmey swirlstogether a mixtape’s-worth of earworms and experience, documenting road trips,birdwatching, visual art, nature walks and playing music, a broadband of allthat circles the domestic of family life, rippling quietly outwards. “Savannahsparrows gather ten times / their weight in detail to orchestrate / the ratioof land to water,” he writes, as part of the lyric “BIRD CARTOGRAPHERS,” “calla light tsu. Caroline / chickadees, cleaner edge of cheek patch, / markdots of cities and dashes / of contours using a broad palette.” I particularlyenjoyed the triptych prose-poem sequence “PHOTOGRAPHS OF BUILDINGS / BY DIANEARBUS,” the first of which begins: “Chimneys can’t push out but so much steam,even the outline’s unfocused in blurry vapour. A quiet loosening of rigidmatter. And how far they jut into the postsecular project of this guy, the sky.Just imagine such alternatives.”

Thethird full-length collection by Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, following

Our Latest in Folktales

(London ON: Brick Books, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Tumbling for Amateurs

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023) [see my review of such here], is

Family Band

(Guelph ON: The Porcupines’Quill, 2024). There’s long been a playfully-askance approach Gwathmey has takenblending formal elements of lyric and narrative, and this collection is nodifferent, offering sharp lines across a folksy, familial and detailedbackdrop. “2022 is the year of the lilac,” he writes, to open the poem “LILACS,”according to the almanac. // So tonight let’s walk the trail behind our house.// To the bushes growing in very great plenty and already divided. // Find anoffshoot. Plant it in our side yard where it scent can flourish / in the fullsun. // Water and wait. We’ll alternate scions with random grafts, // until itsflowers appear at eye level, appearing just before summer / comes into season,// blooms lasting only a couple weeks.” Through short, sharp lyrics, Gwathmey swirlstogether a mixtape’s-worth of earworms and experience, documenting road trips,birdwatching, visual art, nature walks and playing music, a broadband of allthat circles the domestic of family life, rippling quietly outwards. “Savannahsparrows gather ten times / their weight in detail to orchestrate / the ratioof land to water,” he writes, as part of the lyric “BIRD CARTOGRAPHERS,” “calla light tsu. Caroline / chickadees, cleaner edge of cheek patch, / markdots of cities and dashes / of contours using a broad palette.” I particularlyenjoyed the triptych prose-poem sequence “PHOTOGRAPHS OF BUILDINGS / BY DIANEARBUS,” the first of which begins: “Chimneys can’t push out but so much steam,even the outline’s unfocused in blurry vapour. A quiet loosening of rigidmatter. And how far they jut into the postsecular project of this guy, the sky.Just imagine such alternatives.”January 9, 2025

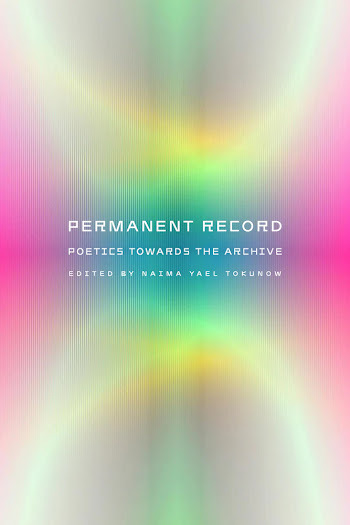

PERMANENT RECORD: Poetics Towards the Archive, ed. Naima Yael Tokunow

Before coming to this project, I had spent nearly adecade thinking critically about the Black American record (or lack thereof),and how my understanding of myself as a Black American, my family, and myculture has been shaped by what I can, and do, know through searching archives.These archives include materials from my family and the state, from papers andoral histories, and from political and artistic recordings. Many records aremissing, misremembered, or unfindable. Some are full and jumbled, hard to decipher.Most are couched in death, grief, and loss. This cannot be and is not the “fullstory,” although we are socialized to understand records as such, rewarded forreinforcing its “wholeness,” and often penalized for pointing to its deficiencies.Many have written beautifully about the wound of not-knowing—our homeland, ourpeople, our tongues, our separation from culture.

[…]

And so, Permanent Record hopes to apply the kindof pressure that turns matter from one thing to another by asking hardquestions: How do we reject, interpolate, and (re)create the archive andrecord? How do we feed our fragmented recordings to health? How do we pullblood from stone (and ink and shadows and ghosts)? What do we gain from our flawedsystems of remembrance? How does creating a deep relationship to the archiveallow us both agency and legibility, allow us to prefigure the world we want? Throughthis reclamation, we can become the ancestors we didn’t have.

Permanent Record wants to reimagine who isincluded in the archive and which recordings are considered worthy ofpreservation, making room for the ways many of us have had to invent forms ofknowing in and from delegitimized spaces and records. In doing so, we explore “possibilitiesfor speculating beyond recorded multiplicity” (thank you, Trisha Low, for thisperfect wording). This book itself is a record. The book asks what can becounted as an epistemological object. What is counted. Who is counted, and how.(“INTRODUCTION: Archives of/Against Absence: exploring identity, collective memory,and the unseen,” Naima Yael Tokunow)

Newlyout is the anthology

Permanent Record: Poetics Towards the Archive

(NewYork NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), edited by Albuquerque, New Mexico-based writer, educator, artist and editor Naima Yael Tokunow. Since being announced as Nightboat’s inaugural Editorial Fellow back in 2023, Tokunow has put togetheran impressively comprehensive anthology on loss, reclamation and the archive,working to gather together elements of what had, has or would otherwise belost, pushing through conversations on what might emerge through and becauseand even despite those losses. “you spend a lot of time thinking about loss,”writes Minneapolis poet Chaun Webster, as part of “from WITHOUTTERMINUS,” considering if what is missing has / a form, wondering if there is amethod to tracing what is not visible. there was / a time when you thought thatif you just had greater powers of imagination, or / if you could somehow placeyourself securely along the tracks of family and / cultural history that youcould gather sufficient evidence, collect all the bones / to make something ofa complete structure.” Across a spectrum of lyric by more than three dozenpoets, Permanent Record speaks of a range of cultural and personal losses,from a loss of language, home and family, reacting to colonialism and globalconflict to more intimate details, writing against erasures both historical andongoing. There is an enormous amount contained within these pages. “In theobits mourning the billionaires,” writes Hazem Fahmy, a writer and critic from Cairo, in “THE BILLIONAIRE / (ARE YOU BOAT OR SUBMARINE?),” “it is mentionedthat they paid / $250k to die before the eyes of the entire world // alaughably cheap ticket / compared to the cost of carrying // a child onto afloating grave. Whose mercy / would you rather stake your life on? The ocean’s?”

Newlyout is the anthology

Permanent Record: Poetics Towards the Archive

(NewYork NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), edited by Albuquerque, New Mexico-based writer, educator, artist and editor Naima Yael Tokunow. Since being announced as Nightboat’s inaugural Editorial Fellow back in 2023, Tokunow has put togetheran impressively comprehensive anthology on loss, reclamation and the archive,working to gather together elements of what had, has or would otherwise belost, pushing through conversations on what might emerge through and becauseand even despite those losses. “you spend a lot of time thinking about loss,”writes Minneapolis poet Chaun Webster, as part of “from WITHOUTTERMINUS,” considering if what is missing has / a form, wondering if there is amethod to tracing what is not visible. there was / a time when you thought thatif you just had greater powers of imagination, or / if you could somehow placeyourself securely along the tracks of family and / cultural history that youcould gather sufficient evidence, collect all the bones / to make something ofa complete structure.” Across a spectrum of lyric by more than three dozenpoets, Permanent Record speaks of a range of cultural and personal losses,from a loss of language, home and family, reacting to colonialism and globalconflict to more intimate details, writing against erasures both historical andongoing. There is an enormous amount contained within these pages. “In theobits mourning the billionaires,” writes Hazem Fahmy, a writer and critic from Cairo, in “THE BILLIONAIRE / (ARE YOU BOAT OR SUBMARINE?),” “it is mentionedthat they paid / $250k to die before the eyes of the entire world // alaughably cheap ticket / compared to the cost of carrying // a child onto afloating grave. Whose mercy / would you rather stake your life on? The ocean’s?”Onthe back cover, the collection self-describes as a “visionary anthology thatreimagines the archive as a tool for collective memory. Reflecting on identity,language, diasporic experiences, and how records perpetuate harm, thiscollection seeks to reframe what belongs in collective remembrance.” “When theceiling drops / the rain stops / beating down but / now you’re beaten down,”writes Okinawan-Irish American poet Brenda Shaughnessy (one of only a handfulof poets throughout the collection I’d been aware of prior), as part of thesequence “TELL OUR MOTHERS WE TELL OURSELVES / THE STORY WE BELIEVE IS OURS,” “thoughit’s the beat / that drops now / and we dance / in the rain / like sunbeams /made out of metal cloth, / tubes of blood, / and scared, sewn-up eyes.” Theanthology includes writing by more than forty writers, most of whom are basedin or through the United States and further south (with at least twocontributors on this side of the border in the mix as well: Hamilton, Ontario-based Jaclyn Desforges and Toronto-based Em Dial). The work in thisanthology is rich, evocative and very powerful, even more impressive when oneconsiders that the bulk of the list of contributors are emerging, with but asingle full-length title or less to their credit. Tokunow offers an expansivelist of contributors from all corners, with an eye for language, purpose; onewould think if you want a sense of the landscape of who you should be readingnext, Tokunow’s list of contributors to Permanent Record is entirelythat. Listen to the lyric of this excerpt of the poem “QUADROON (ADJ., N.)” byEm Dial, that reads:

QUADROON (adj., n.) languageof origin: once again, linguists spit their bloodied air: from Spanish cuarteron,or one who has a fourth. i pinch the linguist’s tongue and gawk at theway they betray themselves. not one who has three fourths. not thehaystack with a needle inside. instead, any drops of life in a sterile lakeare isolated and named. the lake’s volume is doubled again and again and againand again until science feels faultless renaming them Statistically Insignificant.

Theanthology is organized in a quartet of loose cluster-sections—“MOTHERTONGUED,” “FILENOT FOUND,” “THE MAP AS MISDIRECTION” and “FUTURE CONTINUOUS”—each of which, asTokunow offers in her introduction, “begins with an introduction of sorts—a lyricmap legend to the work within, inviting you to pull the threads of theframework through the pieces.” The approach, as one essentially lyric, isintriguing, offering a collection of writing sparked by purpose, but driven andpropelled by a core of stunning writing: Tokunow clearly has a good eye (partof me wants to ask: where are you finding all of these writers?), and knowswell how to organize material around a thesis. The introduction to the finalsection, for example, reads: “We have your number and all quarters. Fortune foldsus up—without a line to the dead we can hear the blood rushing, a cup againstour drum. The gifts we make ourselves (destiny or doom) hold up in flatdaylight, some familiar oath, some new contract: we are finger-deep in the sand,spinning and spiny, no new lines but this soft, fat earth. Still falling offthe page, we ziiiiiiip. We hold the mirror slant—sky and her big feelingsbounce. What can we mine of the future and if, oh not extraction, then what canwe lift, whole and breathing, over our heads?” As San Francisco-based poet Talia Fox writes, to close the lyric “NOTES ON TIME TRAVEL / IN THE MATRILINEAL LINE,”as held in that same closing section:

the curse is simple, and itbegins with water

the water my mother bathed me in was crabwater (it is, after all, the water

alotted for soldiers andthe children of soldiers and their children and especially

their children)

like a spell, like aspell !

when i close my eyes i amwading through a shallow river at evening. i come|

across a forest clearingwhere bodies have been strung up, faceless, bobbing

in the trees

AsI mentioned earlier, more than forty contributors, and I was previously awareof only a few, such as poet and translator Rosa Alcalá [see my review of her latest here], Jaclyn Desforges [see her ‘12 or 20 questions’ interview here], EmDial [see her ’12 or 20 questions here], multimedia poet and author Carolina Ebeid [see my review of her Albion Books chapbook here], Phillippines-born California-based poet Jan-Henry Gray[see my review of his full-length debut here], Minnesota-based poet and critic Douglas Kearney [see my review of his Sho here], and Brenda Shaughnessy (all ofwhom I clearly need to be attending far better). The wealth in this collection isincredible. Or, as Brooklyn-based writer, playwright, organizer and educator Mahogany L. Brown writes as part of the expansive “THE 19TH AMENDMENT &MY MAMA”:

The third of an almostanything

is a gorge always lookingto be

until the body is filledwith more fibroids

than possibilities

January 8, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Emilie Buchwald

Emilie Buchwald’s book of poems, The Moment’s Only Moment won a silver BenjaminFranklin Award. Her poems have been published in Harper’s, The AmericanScholar, Kenyon Review, The Lyric, Sleet, Sing,Heavenly Muse, When Women Look at Men, Rocked by the Waters,among others. She is the editor of the Poetry Society of America’s WallaceSteven Centenary Celebration, The Poet Dreaming in the Artist’s House,Mixed Voices, and This Sporting Life. Her award-winningchildren’s titles include Gildaen and Floramel and Esteban (HarperCollins), and Buddy Unchained.

Buchwald, PhD, Hon DHL, was the cofounder and publisher of Milkweed Editions, editor or coeditor of more than 200 books ofpoetry, fiction, and, nonfiction titles centered on social justice and theenvironment. Books she edited received more than two hundred awards orrecognitions. When she retired, the press had more than a million books incirculation. In 2006, Buchwald became the founding publisher, editor, and nowcopublisher with Dana Buchwald, of The Gryphon Press, publishing children’s picture books about the human-animal bond, addressing thechallenges real animals face and the impact of human kindness and caring.

Distinctions include The Lyric Memorial Award,The Kay Sexton Award, the McKnight Foundation Distinguished Artist of the YearAward, the A.P. Anderson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle IvanSandrof Lifetime Achievement Award.

1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent? I’ve always writtenpoetry; I’ve had poems published in various journals, but my first and second publishedbooks were children’s novels, and, after that, editing four poetry anthologies,all before my first published book of poems. Each experience was positive, but havinga body of work together in a first book was thrilling and very positive.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? Poetry came early and very naturally to me as a way of expressing my thoughtsand experiences with people and especially about describing my thoughts about thenatural world.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes? There’s a first rush of excitement when I’m smitten by anidea for a book. After that, the project takes a great deal of time because Idraft and redraft until I’m satisfied. Sometimes I have to put the project onhold because I can’t see the best way to conclude it.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fictionusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning? It usually begins with an image or an idea. I don’t beginby thinking about a book at the outset but about capturing what I’m seeing andfeeling in each individual poem.

5 - Are public readings part of or counterto your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I very much enjoycommunicating with readers in person. There’s energy coming from an audienceduring a reading, as well as in th questions and answer, and having conversations about thebook afterwards.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are? I’m concerned that as a culture, we aredeliberately shut off by business and government from what happens behind thescene, to animals as well as to people. Writing about the reality of beingalive and in touch with the experiences of the residents of the planet isimportant to me.

7 – What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be? I think that one’s writing should expressone’s personal values. If you can truthfully and persuasively share thosevalues with readers, that’s a meaningful addition to the cultural conversation,and it means committing in our writing to what we really think and care about.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? I have been an editor and publisher for much of my adult life. As aneditor, I do my very best for a manuscript; that is, I speak truthfully aboutwhat would make it better and what I see as holding the work back from being assuccessful and energizing as it might be.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? This is a very old piece of advice: After you’vewritten something and you think you’re finished, put the manuscript away anddon’t look at it for at least a few weeks. The Roman poet Horace suggestedwaiting two years! However, whenever you come back to your work, you will seeit much more clearly, without the first rush of excitement. Tincture of time givesyou the opportunity to be your own best editor and your own harshest critic.

10 - How easy has it been for you to movebetween genres (poetry to books for children)? What do you see as the appeal? I happen to enjoy writing in bothof those genres, and I do think experience in one genre is useful in moving toanother.

11 - What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? An idea for something I’m working on often comes to me unbidden. I jotdown as much as I can of that initial thought until I have time to return toit. But, once I’m engaged in a writing project, I establish a routine for thatwork, and I give it as much time as I can.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, wheredo you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? I read—the writers whose work I admire in the genre I’m working in. That’soften just what I need to do before going back to the project— because I’ve observedways and means to do a better job.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home? Cooking fragrances like cinnamon, parsley, dill and of course, onionsfrying, the great TS Eliot objective correlative. These fragrances jog mysenses into greater connection with the world around me.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art? When I see greatworks of art, I want to know how to admire them, what makes them unique. Thenatural world, however, is a constantly available resource. When I’ve beenenergized by the ever-changing reality outside my door, I feel recharged, andconsider that I might have somethingworthwhile to say.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? Like many writers I know, I’m always keenly interested in what’s new aswell as what books I’ve missed over the years. I follow certain writers,especially poets whose work I love, like Wislawa Szymborska; their writing is nurturing.It’s also fun to talk about books with other writers.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done? Write acollection of short stories. I have a few that I continue to think areworthwhile.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer? I have another occupation, as a publisher and editor, anoccupation that keeps me close to writers and writing.

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else? It wasthe only thing I wanted to do. I was drawn to writing from mu earliest years, becauseI wanted to see whether I could come up with something that I, as a reader,would find worthwhile. I’ve thrown out much, much more than I’ve kept.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film? Recently I’ve been reading nonfiction about the natural world we’reindustriously destroying. I would recommend Ed Yong’s An Immense World as consistently enthralling and enlightening.

20 - What are you currently working on? I’ve started on my next book ofpoems. I’ve also gone back to the most recent draft of a children’s novel thatI think could be more interesting than anything I’ve written thus far. One ofthe joys of writing for me is the constant opportunity to break through intonew territory, to say it better.