Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 30

December 27, 2024

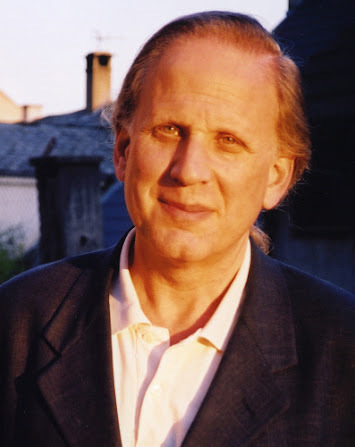

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Roger Greenwald

Roger Greenwald grew up in New York City. He attendedThe City College and the Poetry Project workshop at St. Mark’s ChurchIn-the-Bowery, then completed graduate degrees at the University of Toronto,where he founded and edited the international literary annual WRIT Magazine.He has published four books of poems: Connecting Flight(Williams-Wallace), Slow Mountain Train (Tiger Bark), The Half-Life(Tiger Bark), and in October 2024, An Opening in the Vertical World(Black Widow). He has won two CBC Literary Awards (for poetry and travelliterature), the 2018 Gwendolyn MacEwen Poetry Prize from Exile Magazine,and the 2024 Littoral Press Poetry Prize, as well as many awards for histranslations from Scandinavian languages. More, including videos from booklaunches, at www.rogergreenwald.org .

Q: How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

A: My first book didn’t change my lifeat all. It bestowed on me the label “published poet,” a phrase that peopleoutside the literary world imagine is a compliment. I think that formally myfirst book was my wildest, its music the jazziest. To whatever extent mysubsequent books are edgy, their venturesome explorations are more about statesof mind or states of being than about form. But in my most recent work(published only in journals so far) I have sometimes tried to stretch formagain, though in different ways from those in my first book.

Q: How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

A: As a reader I first came to poetryas a kid: Dr. Seuss and then Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous anthology, A Child’sGarden of Verses. I wrote my first two “serious” poems around age eight. Mymother’s father, who was a Linotype operator, set them and printed them ongalley sheets. Wish I could find those!

Q: How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

A: In poetry I don’t have writingprojects (aside from translations). In prose fiction or memoir, sometimes. At aconference once, a Norwegian poet, adopting a false-naive tone, said to me, “What’sa ‘literary project’? I thought writerswrote books.” I replied, “A literary project is something that can bedescribed on a grant application.” But hats off to poets who conceive of andwrite through-composed books of high quality, crowns of sonnets, long poeticsequences, etc. The time that poems take to germinate varies, but once I’mready to write a poem, that usually goes fast. Sometimes my first draft isclose to the final version; at other times, especially with longer poems, Irevise quite a bit, in stages, and in response to feedback.

Q: Where does a poem usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?

A: A poem usually begins with a linethat I know is a good line of verse. Often it’s the first line of a potentialpoem, but sometimes it’s the last line. I make book mss from pieces I havewritten. They may be short or long, and there may be a sequence of severalpoems. But I don’t start out working on a book.

Q: Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

A: I love reading to an audience andam never nervous. I like seeing how different poems go over and hearing anycomments that people may offer. Although my readings aren’t part of my writingprocess, they do involve creative work, because I usually work with a musician,and that collaboration affects my choice of poems and increases attention totone, mood, and pacing.

Q: Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

A: I have a few principles (whichtheorists may choose to regard as theoretical, but which I regard aspractical). One is that in verse, every line should work as a line. That isdifferent from saying that line breaks should do something. The craft ofthe break is easier to master than the art of the line, which is a rhythmicunit held at least somewhat taut by a certain tension, and at the same time asemantic and syntactical unit that strives to offer some interest by virtue ofhow it begins and ends and what relations its words have to one another. Thoserelations may depend on logical meaning, image, and sound.

I am not trying to answer-pre-existing questions. Each poem may grow outof its own question and may then raise other questions. There are always thequestions of how to make the poem speak to others and how to shape it so itoffers aesthetic rewards, but these are not questions that can be described assubject matter.

The current questions are “What day is it?”; “Who will publish my nextbook?”; and “How can it get a competent review?”

Q: What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

A: The writer’s role qua writeris to write well. The writer’s role as “author” is to try to give the gift ofhis/her work to readers. Writers who choose to be active in the larger cultureor polity do so as citizens and as humans.

Q: Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

A: “Everyone needs an editor.” But by “editor”I mean any perceptive reader who can offer constructive criticism. For poetsthat is most often a poet colleague. But if someone at a publishing house hasqueries and suggestions to offer, that is all to the good, because all feedbackis potentially helpful. If I reject 90% of a colleague’s suggestions, I saythanks for the 10% that yielded improvements.

Q: What is the best piece of adviceyou’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

A: The best advice about poetry that Iever got came from the American poet Francine Sterle: Keep assembling yourpoems into book manuscripts. Don’t wait for one book to be published or evenaccepted to start making the next one.

Q: How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to translation to critical prose)? What do you seeas the appeal?

A: It has been relatively easy for meto move between poetry and prose (whether prose poetry or fiction), and fromwriting to translating and back. But I found that writing a lot ofdiscursive prose (e.g. a dissertation) put my language-generating brain in agroove that felt more like a rut when I tried to climb out of it. As for theappeal, translation kept my hand in when for one reason or another I wasn’twriting. And the contact with another language, as well as the deep immersionin another writer’s worldview and voice that translation requires, canstimulate and broaden one’s own work.

Q: What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A: I don’t have a writing routine. Atypical day begins with reading and answering e-mail.

Q: When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A: I don’t consider not-writing to bea stall. A poet can’t be writing poetry all the time. (Pity the poor novelist,Who wishes she could’ve left home, Who uses all her hours to write pages, Butstill feels like she’s pushing a stone.) At one point in my life when I simplycould not write, I did a lot of translating. But since 2016 or so I have moreor less withdrawn from translation to focus on my own work and on getting itpublished.

Q: What fragrance reminds you of home?

A: Or “Which home reminds me of afragrance?” The Bronx: furniture polish and perfume. Bergen: juniper and oldleather. Toronto: the absence of salt in the air, the smell of what’s missing.

Q: David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

A: Music is perhaps the largestinfluence on my poetry: on the shape and movement and sound of the poems, thefeeling carried by the voice. Music is also part of the subject matter of agood many of my poems. But I have also written poems inspired by and/or aboutfilm, dance, nature, and visual art. My scientific background supplies some ofmy imagery and vocabulary, but science is not a dominant element.

Q: What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A: This could be a long list!Catullus, Whitman, Shakespeare, Donne, Hopkins, Yeats, Wallace Stevens, Dylan Thomas, Stanley Kunitz, Muriel Rukeyser, Joel Oppenheimer, John Ashbery, Joel Sloman, Robert David Cohen, Gunnar Harding, Henrik Nordbrandt, Gjertrud Schnackenberg, James Salter, Susanne Langer.

Q: What would you like to do that youhaven’t yet done?

A: Travel back in time and make betterdecisions. But “yet” implies possibilities and the future. Organize myarchives. Get my manuscripts published. Get sensitive reviews in print andreach a wider audience. Ah, the impossible creeps back into the list.

Q: If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A: If I had had musical training froman early age I probably would have become a composer. If my early life had beenso different that I had not become writer, I might have become a medicalresearcher or, more likely, a lawyer.

Q: What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

A: Magical thinking. The need toimagine that I could communicate with the dead and that the right incantationcould have an effect on others.

Q: What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

A: Poetry: Heavenly Questions, byGjertrud Schnackenberg. Novel: The Werewolf (a purely metaphoricaltitle), by Aksel Sandemose, which I was re-reading. Film: La Grande bellezza (The Great Beauty).

Q: What are you currently working on?

A: Putting together the manuscript ofanother book of poems. Submitting to journals and festivals. Trying to get myjust-published book reviewed.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 26, 2024

from Fair bodies of unseen prose,

, point youtoward the entrance of a house or a jagged stone wall.

How close we are. Surfaces. The difference of clocks. Shoulders, curvedin the light. In which blood flows. And from this day, earth. All electrons. Ibegun my education with redundancies. Pattern recognition, charred residue.Sequels, reboot. Recalculating. Inverted time, a cramped bed for two. My owndisruptiveness. Absolute integrity. Words, itch. Noisily. To talk againstwishes, false in the mouth. Repetitions. Walk, a bit. The water’s edge. Doomed,to consequence. Into the air. This sparkling mist.

, or locked awayin the nonsense of lungs.

Slated, never in ourselves. The missing stone, water. Determining practice. You do not wish tochange geometry. Is there love on Mars? Am I unavailable? The way a beat socasually, drops. The temperature, across red sands. The moon’s influence. Howintrepid. The ear, you lend. Be clear about instructions, what. Or flows, afortress. Tears. My only elsewhere.

We are relationalforms unseen, linings becoming more porous with time.

How visible, thissong of words. How rational, relational. Row upon, the body’s memory. Thismishmash, practice. This loss, arising. To disrupt weather patterns. No soundis, less. A logical objection. One wishes to outlive. I descend some steps.

December 25, 2024

happy holiday things!

from all of us to all of you, there. (and there,

from all of us to all of you, there. (and there,oh, and might we see you on Friday night at our PFYC annual holiday event?

December 24, 2024

filling Station #83 : a bit of love and something to believe in,

As the clavier (still?)makes clear… (The angels between us

& God?) Woodcutforests. Blake, ‘London’ less real than its

soot. Locked in,language’s rooms of one’s own? Death’s life

like ellipsis. Ah, thebody-length turban of prose! Out of Epic

sorts? Words: gods, lemontrees. Reality’s crusts: gaunt readers,

digest. (The round abouthere – poetry, poesy, jars of old light-

ning…) Wind, shardsin the vase. (In moonlight’s chambers,

simile’s slow gin.)Queerly vital lilacs: Being, such an

exhibitionist! (Atoms,abyss abacus.) The slow-

ly rose shadows: thestill yellow

cups. (Sean Howard,“Still Poems (for Wallace Stevens)”)

Incase you weren’t aware, Calgary’s filling Station magazine recentlycelebrated their thirtieth anniversary this year, and a whole slew of pieces celebratingthis milestone, by past contributors and editors, appeared recently via TheTypescript (including Derek Beaulieu, Karl Jirgens, Doug Steadman, r rickey). Thirty years is a long time in publishing, I hope you know,especially a journal with such a combined high turnover of editorial, as wellas its range of high-quality material. The journal originally emerged during animportant period in Calgary writing: one that expanded and exploded acrossexperimental poetry and prose, centred around the University of Calgarycreative writing program [Derek Beaulieu and I worked to acknowledge a numberof the practitioners that emerged from this explosion through our anthology TheCalgary Renaissance]. Throughout all sorts of activity, filling Stationremained, and continues to remain, the publishing heart of that movement, onethat continues to pubish and champion work that might otherwise be seen as toofar “out there.”

Incase you weren’t aware, Calgary’s filling Station magazine recentlycelebrated their thirtieth anniversary this year, and a whole slew of pieces celebratingthis milestone, by past contributors and editors, appeared recently via TheTypescript (including Derek Beaulieu, Karl Jirgens, Doug Steadman, r rickey). Thirty years is a long time in publishing, I hope you know,especially a journal with such a combined high turnover of editorial, as wellas its range of high-quality material. The journal originally emerged during animportant period in Calgary writing: one that expanded and exploded acrossexperimental poetry and prose, centred around the University of Calgarycreative writing program [Derek Beaulieu and I worked to acknowledge a numberof the practitioners that emerged from this explosion through our anthology TheCalgary Renaissance]. Throughout all sorts of activity, filling Stationremained, and continues to remain, the publishing heart of that movement, onethat continues to pubish and champion work that might otherwise be seen as toofar “out there.”Partof what is always interesting about filling Station is the blend ofstyles, leaning an experimental bent (but open to the straighter lyric) acrosswork by emerging and established writers, allowing for the possibility ofpushing against boundaries of form, in matters lyric, visual and through thesentence, and everything in-between. While the visual collage of South Bend, Indiana-based Toronto poet Camille Lendor’s “The Best Pizza Dough Recipe” mightbe built upon the central core of a more traditional lyric, Calgary poet David Martin’s “Mnemotechnics” and California-based poet [Sarah] Cavar’s “GoodbyeForever Party” are curious to see side-by-side, given their echoes of eachother’s striking lines of accumulation. “I go like smoke pulled toward aceiling,” Cavar writes, “Leave bad black brackets on pastel walls.” I’mintrigued as well by the small points, the accumulated moments, of Ottawa poet Frances Boyle’s poem “inflorescence,” more pointillist than her “Stroll,” but withinthe same field of structure. In each poem, she structures a singlesentence-thought across breaks of space, line, breath and thought. “who gave melife / give me this,” the second half of her first poem reads, “our relativesthe air / flood // our rich friend / silt [.]”

There’sa curious short scene, a short story by Cobourg writer, editor and publisher Stuart Ross, “The Red Ink,” that is quite intriguing. He writes to explore and expandupon a single frame [read my essay on his most recent collection of stories, in case you hadn’t seen], a structure he’s used often across his prose, but heldhere as a focus upon that singular moment, one that still allows a view of therippling effect beyond. As he writes, near the end:

“I am happy here,” perhaps he explained, “but your time isgetting short. The winds are changing, the air is desiccated. The red ink thatflows through your veins will soon start to search for a way out.”

In the distance, laughter.

Skates arcing through the air.

December 23, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kira Rice

Kira Rice is a Chicago-based writer. She is inspired by non traditionalforms of love, femininity, nature, mental health and humanity. Her publishedworks include A Lengthy List of Lovers, Love Language, and DeathBy You Is Beautiful: Poems all available on Amazon.

1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

- The first book I ever wrote and self-published was essentially apolished version of my own diary. It was a collection of short stories, goinginto an embarrassing amount of detail about every boy or girl I ever thought Iwas in love with. Each chapter was titled with the name (or some version) ofthem. Going through old diary entries and revisiting all of those memories,some of them fond and some of them painful, was therapeutic. I think writingthat book was a necessary part in my growing up, becoming more self-aware, andmoving forward.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

- Poetry has always been myfirst love. When I was in middle school I thought I’d be a songwriter. I don’tquite now how or when I attached myself to it, but I assume it was my love formusic as a child. It’s always felt like a safety net, or a security blanket.There for me to pick up and put down when I need it.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

- It’s weird, because I’ll have an idea or two floating around inmy head for months or years even. And then one day, I’ll have a completely newidea that I’m so excited about I get started immediately. Rather than sittingon it, and planning properly, I’ll just start feverishly working until I havesome type of rough draft. And then I’ll find that the longer I take to rewriteand edit, the less I like it. So once I really get started on something, I tryto get it out of my system as quickly as possible so to speak.

4 - Where does a poem or work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

- I’m always writing poetryjust to write it. I’ll post them to social media here and there or send them assubmissions. After a year or two of that I’ll realize just how many I havesitting on my desk, and I’ll try to format some sort of book out of them. OnceI have a theme, I’ll rework some, or write new ones to add.

5 - Are public readings part of or counterto your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

- I so wish I had the gutsto do spoken word poetry. The most I can conjure is to post videos online. It’sa goal of mine, definitely. But I haven’t quite crossed that bridge yet.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are?

- I think I’m always writing a poem to work outan emotion or a memory that doesn’t quite sit right with me. Poetry helps meconnect the dots, and understand things about myself and my relationships. So Ithink the question is always, what does this mean, how do I feel about it, andwhy?

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

- I don’t really know. It’shard to place that sort of responsibility on anything creative. I don’tconsider it a role, but I do hope at the most my writing puts words to feelingsand situations that another person may not be able to, or helps them grapplewith issues that may be similar to whatever I’m writing about. Books are a toolin that way, I think.

8 - Do you find the process of working withan outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

- So far I’ve actually neverworked with an outside editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you'veheard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

- When you’re in a creativeslump or dealing with writers block, think of your project as an exciting newlover. Sneaking away at whatever hours you can manage to visit them. Seeingthem with hopeful and fresh eyes.

10 - How easy has it been for you to movebetween genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

- I haven’t published any fiction yet. It’s beendifficult for me, actually. I haven’t figured out how to make fiction feel ashonest and authentic as poetry. Maybe that’s the point and I’m missing it.

11 - What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

- I try to write every day,and I do most of my writing late afternoon to early evening. I have a day joband a family so I try to squeeze writing in wherever I can really.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, wheredo you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

- Anything nature helps me.Going on walks, looking out windows, sitting in romantic looking coffee shopsand bookstores and listening to chatter. If that doesn’t work I’ll turn tofilms, music, other poets for inspiration.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

- I’m from a pretty ruraltown in the Midwest, so naturally.. Fresh cut grass and the morning after rain.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that bookscome from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

- Nature!! And humanitiescollaboration with it. Film is big for me too, as well as music.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

- I read a lot of intersectional feminist theoryand nonfiction. I’m also drawn to books that speak to the complexities andnuances of femininity, womanhood, female friendships. I’m a sucker for a messymother daughter story, too.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

- Travel more. I’ve traveleda bit but not so much out of the country.

17 - If you could pick any other occupationto attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

- I’ve always wanted to tryacting or filmmaking. I admire both so much but the skill level and talent thattakes is intimidating to me, for sure.

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

- Writing always camenaturally. I’m not the best with words out loud, and writing has always been myway of saying what I really mean.

19 - What was the last great book you read?What was the last great film?

- The last great book I readwas My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante. I’m late to the party, but itwas definitely worth the read. The last great film I saw was A24’s Civil War.Otherwise I’ve been rewatching a lot of my favorite horror films this season.

20 - What are you currently working on?

- I just finished my newcollection of poems, Death By You Is Beautiful, and it comes outNovember 8th. So right now I’m just working on trying to push that out!

December 22, 2024

Eileen Myles, a ‘Working Life’

The sky hates me

I must be calm

I must be calm

if I have any

chance of good

ness

at all

a child in

a snowstorm

a man faces

death

slow (“Love Song”)

I’mworking my way through the latest poetry collection by New York poet Eileen Myles,

a

“

Working Life

”

(New York NY: Grove Press, 2023) [see my reviewof Myles’ selected poems here; and of a prior poetry collection here], acollection that offers, to open the “Acknowledgments”: “I wanted to say a ‘WorkingLife’ means the poems are the plan, not that this book is about laborexactly.” “That’s not a new thought / & every single thing u / Built is a perch,”Myles writes, to open the short poem “Painting Is the Sky.” A life livedthrough writing, as the legendary Myles continues their exploration acrossfirst-person directness—the clarity of a straightforward lyric that is rich incomplexity—offering writing not a means to an end but a means of methodology andfunction: to write one’s way into being. “It is the first / day of the new /Year. The city honors / This day by not / Requiring us / To move our / Cars.” (“Pigs”)

I’mworking my way through the latest poetry collection by New York poet Eileen Myles,

a

“

Working Life

”

(New York NY: Grove Press, 2023) [see my reviewof Myles’ selected poems here; and of a prior poetry collection here], acollection that offers, to open the “Acknowledgments”: “I wanted to say a ‘WorkingLife’ means the poems are the plan, not that this book is about laborexactly.” “That’s not a new thought / & every single thing u / Built is a perch,”Myles writes, to open the short poem “Painting Is the Sky.” A life livedthrough writing, as the legendary Myles continues their exploration acrossfirst-person directness—the clarity of a straightforward lyric that is rich incomplexity—offering writing not a means to an end but a means of methodology andfunction: to write one’s way into being. “It is the first / day of the new /Year. The city honors / This day by not / Requiring us / To move our / Cars.” (“Pigs”)Acrossa “working life,” Myles is the intellectual flaneur, writing ofgroceries, libraries, love and planets, building lobbys and blades of grass; acity poet since famously arriving in New York from Boston back in 1974, landingdirectly in with elements of the New York School and street-level punk poets. Onecan see echoes of the intimate directness and documentary through language of NewYork School poets Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley, as well as elements of thediaristic walking and thinking “I did this, I did that” lyrics of Stacy Szymaszek and Frank O’Hara, and the electrified language and intimate propulsionof Kathy Acker. “The poetry / of accident / haunts / like a circus / tent over/ my days,” they write, as part of “March 3,” “and that / fades / and a new /one. I / begin to / write / about dying.”

Ifyou are interested in Myles’ work, I would also highly recommend James Yeh’sstunning interview with Myles in a recent issue of The Believer (Vol.21, No. 2; Summer 2024). The interview is incredibly rich, as Myles offers theirown knowledge based on skill, experience, and too much to repeat here:

I just think it’srepetition. It’s like anything. It’s really similar to how you know if a poemis good. You know because you’ve just been there and you’ve been repeating andrepeating. For some reason lately I’m freaky on repetition as a value. Because everythingthat’s good, you’ve done it again and again and again and it becomes yourfriend and it becomes your turf and it becomes your nest and then it’s just theright place to be and the right way to be.

Howto not only figure out how best to write but how best you should be writing.This is, after all, an important distinction, and one not everyone seems tohave figured out. It took me close to a decade of active prose writing before Icame to that same conclusion: not how I thought a novel should bewritten, but how best to write a novel in my own way. Give out all your tools,I say. A bit further on in the same answer, as Myles offers:

You kind of make your ownnest, that’s the thing.

December 21, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Douglas Cole

Douglas Cole haspublished eight poetry collections, including

The Cabin at the End of the World

, winner of a Best Poetry Award in the American Book Fest, and thenovel

The White Field

,winner of the American Fiction Award. His work has appeared in journals such asBeloit Poetry, Fiction International, Valpariaso, The Gallway Review and Two Hawks Quarterly.

Douglas Cole haspublished eight poetry collections, including

The Cabin at the End of the World

, winner of a Best Poetry Award in the American Book Fest, and thenovel

The White Field

,winner of the American Fiction Award. His work has appeared in journals such asBeloit Poetry, Fiction International, Valpariaso, The Gallway Review and Two Hawks Quarterly.Hecontributes a regular column, “Trading Fours,” to the magazine, Jerry Jazz Musician. Healso edits the American Writers section of ReadCarpet, a journal of international writing produced in Columbia.

Inaddition to the American Fiction Award, his screenplay of The White Field won BestUnproduced Screenplay award in the Elegant Film Festival. He has beenawarded the Leslie Hunt Memorial prize in poetry, the Best of Poetry Award fromClapboard House, First Prize in the “Picture Worth 500 Words” from Tattoo Highway, and theEditors’ Choice Award in fiction by RiverSedge.He has been nominated Six times for a Pushcart and Eight times for Best of theNet. His website is https://douglastcole.com.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

The first book Ipublished was a short collection of poetry. That opened some doors, I think,that led to other publishers perhaps looking more seriously at my work. Each publication after that raised a few moreeyebrows, journal editors paid more attention, and it all changed my way ofthinking about the publishing process, the collaborative part of which I enjoy.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I didn’t really come topoetry first, but it was the first book form I published. I started writingfiction and poetry and had no plan to focus on one or the other. So, fiction,poetry, drama, essay and even screenplay writing all have poetry in them. Theforms are just different.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don’t tend to dragthrough fallow periods, as such. I also waited to publish until I had what feltlike a good amount of work. When I’ve got something I feel pretty sure I wantto make public by publishing, I tend to work quickly in the sense that I know I’mchanging and given enough time I could change my thinking about a pieceinfinitely, so I try to stay focused so that the style or vision or whateverwon’t suffer from gaps in attention. Some first drafts are just born ready andrequire only minor adjustments. Some, and I enjoy this journey, might get torndown to the studs and built up again, maybe unrecognizable to anyone else, butI know where they came from.

4 - Where does a poem orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

It’s fun to work onsomething that can be more or less completed in a day: a poem draft or shortstory draft. They build up and then, hmmm, that could make a book. Sometimes aseries of poems come together, and there’s a chapter. They don’t always go quicky,though. But I have set out to craft a novel, knowing I am making a novel. In thosesituations, I tend to set mini deadlines of manageable parts that will fit intoa book. Sometimes, there’s just this whole story in my head and I have to stickto the road and get to the destination, the ending, if I have an idea what thatis.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I’ve spent a lot of timeteaching as well, so that’s helped my confidence in front of a group. Dependingon the setting, reading can be a lot of fun, especially if the audience is intoit and I can feel that lock-in, like we’re having a collective dream. Also, agood part about the idea of reading is that it reminds me that with poetry orprose, the words have to travel elegantly through the mouth. I feel that’s atarget: not only to make whatever it is be beautiful on the page but beautifulto the ear. Reading aloud puts a spotlight on that.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Fascinating. I think ofwriting as an exploration. I’m less attracted to presenting textbook cases thandoing a forensic close up. If the message is clear, what’s the point? I like alittle mystery in what I read and write. I want the work to be more than thesum of my ideas and edits, even if that sounds odd. Art should be a window nota sandwich board. In other words, being too attached to “meaning” is likeputting blinders on. Not that random, excruciatingly private references andhaphazard language or automatic writing are better, but in the process, alittle of that might open some thought, some vision I wouldn’t have had if Istuck to thinking I want to say X or Y or whatever.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

The diversity of writersand their creations is our culture. I think writers both clarify theexperience we’re having in this life in beautiful ways, acting as mirrors,commentators, guides. And I think writers (like all artists) are the creatorsof our religions, philosophies, laws, histories. All of them describing theelephant and some dreaming of bigger fish than that.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve been pretty lucky towork with good editors, some great. Only once did I ever work with an editorwho seemed less clear as the process continued. I pulled that piece eventuallybecause it seemed like the process was going in circles and had less to do withthe work than something else. So, by the time I’m ready to try and publishsomething, I relish the input.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Get off the subject.”(R. Hugo)

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to screenplays)? What do yousee as the appeal?

They’re different clothesthat all fit well. And I like the way they inform each other. A little poetrymight help a flat piece of prose. A little narrative continuity might help animpressionistic, lyrical poem keep its feet on the ground. In the same way youshould know all the religions and philosophies but keep them out of your art, Ithink you should work in all the forms and treat them equally as language asmuch as formal adventures.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Well, I like to get up,have a cup of coffee, read a little, write a little, start the day with my headin the words. Sometimes a few fleeting dream images come along, and I oftenlike to write them down because I think that’s information, experience, welargely dismiss as irrelevant or just too confusing to bother with. But it’s agreat mystery well we’re nightly dropped into, and I think worth exploring, andgood practice for getting beyond the limited, rational, conscious ways we thinkand feel about our lives.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Reading. Walking. Playingguitar. And there’s no law against taking a break. While I love the mystery andexploration of writing, I’ve never felt I must be brilliant every moment.Sometimes writing is just a way to remind myself how to see, how to think moreopenly. I tend to be pretty disciplined about writing something each day, justfor the fun of it. It doesn’t have to be on the way to a poem or story orpublication. In fact, I didn’t publish for a long time to avoid the mindsetthat I need to “produce.”

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Rain, wisteria,woodsmoke, the sea.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of it. Movies, songs,paintings, dreams, but some of the very best sources have come from overheardconversations or a moment a scene unfolds on the corner of 3rd and PikeStreet on the way to work. So, always be alert!

15 - What other writersor writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of yourwork?

Roethke. Great teacher ofthe music. Patti Smith. I love the poetry of her language. She talks to you.But it’s beautiful poetry too! Borges. I love the surreal but again poeticlanguage in his writing.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

I think I really want to direct.

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I love music, but I’venever felt confident about my singing voice. I also teach, and I love that. Iwould have liked to be an astronaut, but we’re not really going anywhere beyondthe solar system, so, I think I’ll wait.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

It was just a fun thing Icould do on my own, anywhere, anytime, no technology beyond a pen and paperneeded.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Great book…maybeMurakami’s Wind-up Bird Chronicle. I wrote a lot of notes in themargins. I also really loved Joy Harjo’s Crazy Brave. The last greatfilm I saw…I liked Alejandro Iñárritu’s Bardo.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I’m editing another Bookof poetry set for publication later this year called Drifter, poetrybased on Guy Debord (French writer, part of the Situationists International)and his ideas on the dérive. “One of the basic situationist practices is thedérive [literally: “drifting”], a technique of rapid passage through variedambiances. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness ofpsychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classicnotions of journey or stroll.”

December 20, 2024

Dawn Lundy Martin, Instructions for The Lovers

In the end, I suppose,defeat is inevitable,

the closing of something once delicately propped

open, a silk curtainfloated back to its nature,

or a mother, which is what this is really about—fetish of

the mother, the fetish ofher under my tongue, bleating

about. Even I can’t let go, can’t sift her being (thatpart

of her that’s her) frommy hands. What’s wanted

is not to be gotten, no frolic in dancing fields,

no cupping of theinvisible cup, gentle water, soft hand,

sweet ache of breath into mine. Mine, slats between—what

was it? What is it now? Whenyour voice comes through

my ear, technological and distant, the crack of it

as much a weapon as afrozen foot, as much the desert’s

reflective waterwell as any ( )—

You see that? My handsarching around what would be absence

If absence were rot inside the body. We both hold it. (“FROMWHICH THE THING IS MADE”)

Thefifth full-length poetry title by American poet and essayist Dawn Lundy Martinis the remarkable

Instructions for The Lovers

(New York NY: NightboatBooks, 2024). I admire the delicate precision of Martin’s lyrics, set with aclear sense of music and the line. “The lover was here and then was not.” she writes,to open the prose-block “INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE LOVERS,” This is always / thecase. The lover persists in loverness and then, poof. / Not poof poof but outof the kitchen and casual naked- / ness. The lover is a long tail though. Whippingaround.” Her poems hold a determination, weave and pitch; a clarity of purposeand a narrative delicacy, weaving simultaneously around and through hersubjects, fully aware of the shapes of her stories.

Thefifth full-length poetry title by American poet and essayist Dawn Lundy Martinis the remarkable

Instructions for The Lovers

(New York NY: NightboatBooks, 2024). I admire the delicate precision of Martin’s lyrics, set with aclear sense of music and the line. “The lover was here and then was not.” she writes,to open the prose-block “INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE LOVERS,” This is always / thecase. The lover persists in loverness and then, poof. / Not poof poof but outof the kitchen and casual naked- / ness. The lover is a long tail though. Whippingaround.” Her poems hold a determination, weave and pitch; a clarity of purposeand a narrative delicacy, weaving simultaneously around and through hersubjects, fully aware of the shapes of her stories.Openingwith a minimalist sequence, “[After wind was water],” the poems evolve across threesection-clusters of sharp lyrics before ending with a sequence of prose poems,and an extended, accumulated phrase-lyric. While some might shift form asexploratory, Martin already employs a mastery across a variety of structures,all of which allow for her particular rhythm of narrative unfolding. “And yet,”the poem “A WILD WEED” offers, “what savagery disrobes inside order? / Whatstreet fight made fragile in a hot / face glow parted so that, so that / allliquid is in retrieval.”

December 19, 2024

VERSeFest (mini) 2024 : a report from the ground,

In case you hadn't heard, we did a mini-"fall into VERSeFest" in November, all part of our rebuilding period for our much beloved poetry festival, heading into our sixteenth year with current plans for spring 2025 programming. Can you believe it? And you know, we do have charitable status, if you are ever open to sending a donation our way. What might spring bring?

In case you hadn't heard, we did a mini-"fall into VERSeFest" in November, all part of our rebuilding period for our much beloved poetry festival, heading into our sixteenth year with current plans for spring 2025 programming. Can you believe it? And you know, we do have charitable status, if you are ever open to sending a donation our way. What might spring bring?And you caught my report on our spring 2024 festival as well, yes?

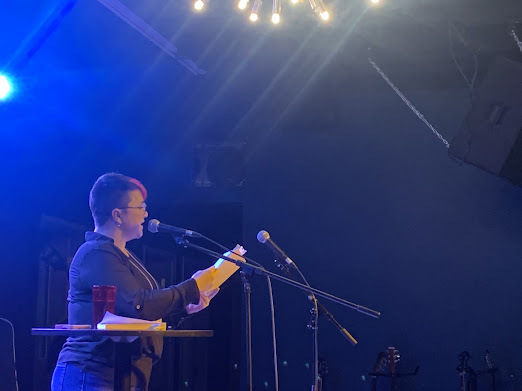

Our November trio of nights opened on Thursday, November 28 at RedBird Live in Old Ottawa South with the delightful

Madeleine Stratford

as host, filling in for the scheduled host Stephen Brockwell, who was unable; she played up that she was Stephen Brockwell, "not feeling myself," and looking like another, a poet and translator. The evening held a quartet of stunning readings. Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick read from her new poetry title with Anvil Press,

Ox Lost, Snow Deep

(2024) [did you see my recent interview with her here], and it was interesting to hear her stretch the possibilities of her work through the long poem [catch my review of her new book here, in case you missed]. She even conducted a small afternoon in-person poetry workshop as part of the festival on Saturday afternoon,

Our November trio of nights opened on Thursday, November 28 at RedBird Live in Old Ottawa South with the delightful

Madeleine Stratford

as host, filling in for the scheduled host Stephen Brockwell, who was unable; she played up that she was Stephen Brockwell, "not feeling myself," and looking like another, a poet and translator. The evening held a quartet of stunning readings. Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick read from her new poetry title with Anvil Press,

Ox Lost, Snow Deep

(2024) [did you see my recent interview with her here], and it was interesting to hear her stretch the possibilities of her work through the long poem [catch my review of her new book here, in case you missed]. She even conducted a small afternoon in-person poetry workshop as part of the festival on Saturday afternoon, Following Burdick, Ottawa/Burlington poet Manahil Bandukwala [catch my recent interview with her here] launched her second full-length title with Brick Books,

Heliotropia

(2024), a book I'm still waiting to get my hands on (perhaps as the mail starts up again), accompanied by her "electric guitar boyfriend,"

Liam Burke

. Our French-language Ottawa poet laureate Véronique Sylvain followed, offering poems from her second collection, which launched only a few weeks prior through Éditions Prise de parole.

Following Burdick, Ottawa/Burlington poet Manahil Bandukwala [catch my recent interview with her here] launched her second full-length title with Brick Books,

Heliotropia

(2024), a book I'm still waiting to get my hands on (perhaps as the mail starts up again), accompanied by her "electric guitar boyfriend,"

Liam Burke

. Our French-language Ottawa poet laureate Véronique Sylvain followed, offering poems from her second collection, which launched only a few weeks prior through Éditions Prise de parole.

And, to close out our opening evening, Cobourg, Ontario poet, editor, writer, publisher, events organizer etcetera

Stuart Ross

(who had also edited Alice Burdick's latest collection, as well as her prior), launching his new poetry title with Coach House Books, a publisher he offered he'd been waiting decades to work with:

The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky

(2024) [see my review of such here; see my essay on his short fiction as well here]. The collection does seem a culmination of everything he's accomplished to date, and I'm curious to see where he might go with his work next.

And, to close out our opening evening, Cobourg, Ontario poet, editor, writer, publisher, events organizer etcetera

Stuart Ross

(who had also edited Alice Burdick's latest collection, as well as her prior), launching his new poetry title with Coach House Books, a publisher he offered he'd been waiting decades to work with:

The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky

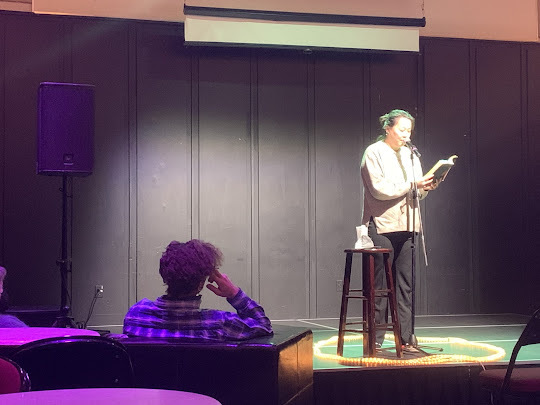

(2024) [see my review of such here; see my essay on his short fiction as well here]. The collection does seem a culmination of everything he's accomplished to date, and I'm curious to see where he might go with his work next. Our second night, Friday, November 29, opened in the Arts Court Studio with an event celebrating fifteen years of

Urban Legends

(who have been running spoken word poetry workshops, in case you weren't aware), hosting performances by three of their current/former directors, opening with

Billie Nell

, who I thought stole the show. As they said as part of the event (and others have said over the past couple of years as well), spoken word in and around Ottawa is but a shadow of its former self, and I admire greatly that these folk are working to keep the form current, active and relevant (attend their workshops!).

Our second night, Friday, November 29, opened in the Arts Court Studio with an event celebrating fifteen years of

Urban Legends

(who have been running spoken word poetry workshops, in case you weren't aware), hosting performances by three of their current/former directors, opening with

Billie Nell

, who I thought stole the show. As they said as part of the event (and others have said over the past couple of years as well), spoken word in and around Ottawa is but a shadow of its former self, and I admire greatly that these folk are working to keep the form current, active and relevant (attend their workshops!).

Apollo the Child

[above] is always a solid performer, one of the standards of the Ottawa scene for some time, and he even had copies of a recent publication, with a further publication to appear soon in the new year. Much like Billie Nell, the work of

Playto aka Panos

was entirely new to me, and he performed a handful of poems that focused on new and recent parenthood (with one of his small children in the crowd, also).

Apollo the Child

[above] is always a solid performer, one of the standards of the Ottawa scene for some time, and he even had copies of a recent publication, with a further publication to appear soon in the new year. Much like Billie Nell, the work of

Playto aka Panos

was entirely new to me, and he performed a handful of poems that focused on new and recent parenthood (with one of his small children in the crowd, also).

Our second event of the evening was hosted by Ottawa poet and newly-minted VERSe Ottawa board member (with a debut novel forthcoming, you know)

Ben Ladouceur

. The first reader was Ottawa-favourite

Chuqiao Yang

(clearly the lighting in the space changed, and these photos seem terrible, don't they?), reading from her long-awaited full-length poetry debut,

The Last to the Party

(Goose Lane Editions, 2024) [see my review of such here].

Our second event of the evening was hosted by Ottawa poet and newly-minted VERSe Ottawa board member (with a debut novel forthcoming, you know)

Ben Ladouceur

. The first reader was Ottawa-favourite

Chuqiao Yang

(clearly the lighting in the space changed, and these photos seem terrible, don't they?), reading from her long-awaited full-length poetry debut,

The Last to the Party

(Goose Lane Editions, 2024) [see my review of such here].

Admittedly, I was extra excited to hear from Montreal-based poet

Faith Paré

, who is doing remarkable work, and even moreso when one considers she hasn't yet a full-length book [see the interview I did with her earlier this year, prior to her winning the Bronwen Wallace Award].

Admittedly, I was extra excited to hear from Montreal-based poet

Faith Paré

, who is doing remarkable work, and even moreso when one considers she hasn't yet a full-length book [see the interview I did with her earlier this year, prior to her winning the Bronwen Wallace Award]. It had been a while since I'd heard Vancouver poet Stephen Collis read in person (most likely in spring 2013; I have a recollection of him reading in Ottawa back then), here to launch his latest poetry title from Talonbooks, The Middle (2024) [see my review of such here]. It is interesting to hear how his work has progressed, becoming more expansive and thoughtful as he moves ever forward, extending his lyric reach ever outward, even as his work becomes more grounded, intimate.

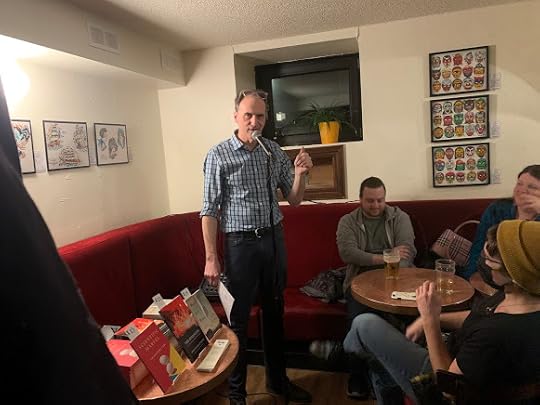

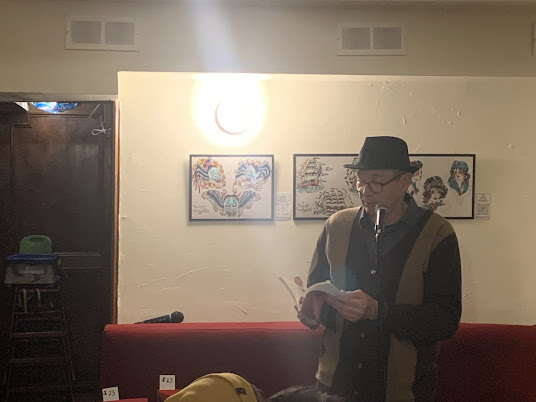

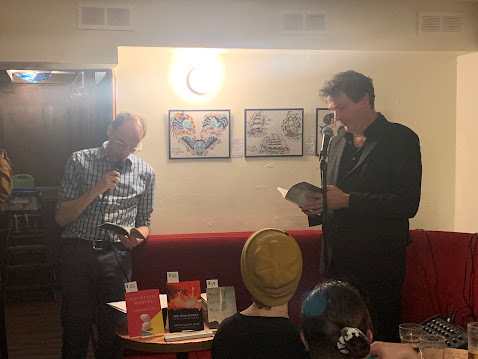

Our final event came the following afternoon (including some attendees from Alice Burdick's afternoon poetry workshop) at The Manx Pub, hosted by Ottawa English-language Poet Laureate David O'Meara and his Plan 99 Reading Series, a packed house to hear our final trio of exceptional poets [catch my interview with O'Meara on his laureateship here]. To open the afternoon was Kingston-based poet, writer and filmmaker

Armand Garnet Ruffo

[see my recent interview with him here]. He used to live in Ottawa, you know, so a whole slew of audience was there to hear him, especially that he was launching a new title with Wolsak and Wynn,

The Dialogues: The Song of Francis Pegahmagabow

(2024).

Our final event came the following afternoon (including some attendees from Alice Burdick's afternoon poetry workshop) at The Manx Pub, hosted by Ottawa English-language Poet Laureate David O'Meara and his Plan 99 Reading Series, a packed house to hear our final trio of exceptional poets [catch my interview with O'Meara on his laureateship here]. To open the afternoon was Kingston-based poet, writer and filmmaker

Armand Garnet Ruffo

[see my recent interview with him here]. He used to live in Ottawa, you know, so a whole slew of audience was there to hear him, especially that he was launching a new title with Wolsak and Wynn,

The Dialogues: The Song of Francis Pegahmagabow

(2024). Current Winnipeg Poet Laureate

Chimwemwe Undi

followed, reading from her Governor General's Award for Poetry winning (debut!) title,

Scientific Marvel

(Anansi, 2024) [see my review of such here], an award she won between announcing our line-up and her landing in Ottawa to read (so extra kudos to O'Meara's curation for this particular event). She did mention how unreal the award seemed to her, and expecting that she could still hear from them that the award was supposed to go to someone else instead, akin to Moonlight [the Academy Award "envelope-gate" debacle from 2017, in case you'd forgot]. I suggested that, no, she was not the La La Land of Canadian poetry.

Current Winnipeg Poet Laureate

Chimwemwe Undi

followed, reading from her Governor General's Award for Poetry winning (debut!) title,

Scientific Marvel

(Anansi, 2024) [see my review of such here], an award she won between announcing our line-up and her landing in Ottawa to read (so extra kudos to O'Meara's curation for this particular event). She did mention how unreal the award seemed to her, and expecting that she could still hear from them that the award was supposed to go to someone else instead, akin to Moonlight [the Academy Award "envelope-gate" debacle from 2017, in case you'd forgot]. I suggested that, no, she was not the La La Land of Canadian poetry.

It was good to have

Dutch poet Erik Lindner

back in Ottawa! He's read in town a few times over the past decade-plus, starting with an event years back through the Ottawa International Writers Festival. He read his poems in Dutch, and David O'Meara read from English translation, some of which came from his

Words are the Worst: Selected Poems

, as translated by Francis Jones (Vehicule Press, 2021).

It was good to have

Dutch poet Erik Lindner

back in Ottawa! He's read in town a few times over the past decade-plus, starting with an event years back through the Ottawa International Writers Festival. He read his poems in Dutch, and David O'Meara read from English translation, some of which came from his

Words are the Worst: Selected Poems

, as translated by Francis Jones (Vehicule Press, 2021).Thank you to our host and our venues, and everyone who helped out! Thank you to the City of Ottawa and the Dutch Embassy for support! Thanks to Brian Pirie for his web design and ongoing assistance! And to the current VERSe Ottawa board, without whom this couldn't have happened at all.

Keep an eye on our website! We're hoping to announce an occasional series of in-person poetry workshops in the new year, and of course our spring festival! We've already been having meetings, you know. And did you hear we're hoping to announce the next nominees for our Hall of Honour come spring? Stay tuned!

December 18, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kirsten Allio

Kirstin Allio receivedthe Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize from FC2 for her 2024 storycollection, Double-Check for Sleeping Children. Previous books are the novels Garner(Coffee House Press, LA Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction finalist),Buddhism for Western Children (Universityof Iowa Press), and the story collection Clothed,Female Figure (winner of the Dzanc Short Story Collection Competition).Recent stories, essays, and poems are out or forthcoming in AGNI, American Short Fiction, Annulet,Bennington Review, Black Sun Lit, Changes Review, Conjunctions, Fence,Guernica, Guesthouse, Harp & Altar, The Hopkins Review, Interim, NewEngland Review, The Paris Review Daily, Plume, Poetry Northwest, The SouthernReview, Subtropics and elsewhere. Her honors and awards include theNational Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 Award, the PEN/O. Henry Prize, theAmerican Short(er) Fiction Prize from American Short Fiction, chosen byDanielle Dutton, and fellowships from Brown University’s Howard Foundation andMacDowell. She holds an MFA from Brown, and lives in Providence, RI.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, Garner, isa morality tale set in 1920s New Hampshire that chronicles an individuated,city sensibility encroaching on tradition and communal repression in a smallrural town. A mystified layer or two deeper, it’s a rape novel. I learned, bywriting, that I write in search of moral clarity. If there’s a moral formulationfor being an artist it’s shaky, but the sense of calling is true. Becoming awriter with my first book stuck me in the moral crosshairs between service andself-fulfillment, where I remain.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetryor non-fiction?

That feeling of being both enchanted and overwhelmed by reality,and wanting to grasp it, understand, metabolize, reproduce it… An analogy for realistfiction for me is the still life. A vase. Just a vase—that leaps off the table,rolls, shatters, recombines—that’s a novel.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I am slow. Time itself is a key player, a creative agent. I meanthat time actually does the work of composition and editing for me. I’lltypically take a flurry of fragmentary notes, impressionistic, outside thehabitat of my office. Many stories start on trains, or sitting in somebodyelse’s park, somebody else’s city. Layer by layer, over years, I build up astory.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I usually know whether any given material—and it could be as smallas a single image, or an exchange, or a glob of language—is a poem or shortstory or a novel. The seed material is sensitive to genre, as if it had a DNA. Ihave never turned a poem or a story into a novel. A novel has never turned outto be a story. I don’t know why this is so unerring for me.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love to read out loud, and every single time, I’m shocked by howeffective an editing tool it is, a truth serum. When I read from publishedwork, I always edit at the last minute, and then again in real time, and itkind of kills me, because of course it’s too late to change on the page, andthen I vow to read out loud at all stages of writing…

So in that sense, public readings are essential to my writingprocess, and I’m grateful to friends and strangers who attend.

I shrink, however, from explaining my work, from claims ofaboutness. Of course meaning isn’t finite, can’t be depleted, but I have a fearof foreclosing, cauterizing infinite meaning if I suggest one meaning oranother. I’m also just not very fluent in summary. I could never write a bookreport in grade school. I feel there’s a risk of betraying the fiction if Italk about it in the language of nonfiction, or conversation, or explication—ifI translate it into that unholy aboutness. Or maybe I’m the actor who has areally tinny, tiny voice, who’s just kind of a bimbo outside the film. I don’twant to disappointment readers.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

Theories of the human condition! Theories of feminism—the koan-likequestion that opens The Second Sex,“Are there women, really?” Injustice, technology, nature, time.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

When a writer or a philosopher comes up with some gem of ajustification, I’m the first to scribble it down on my napkin. Hannah Arendt,in Men in Dark Times: “The storyreveals the meaning of what otherwise would remain an unbearable sequence ofsheer happenings.” Art saves lives, and that kind of thing. I am always, alwaystrying to justify my place on the planet. I can justify a calling—I feel I haveone—but I cannot justify art-making as separate, isolated from, or even aboveservice to humanity. So there I dwell, unjustified, called, uncomfortable,writing.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

It’s a rare pleasure.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

Surely something that hit in the moment and then evaporated…

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetryto short stories to novels)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s easy and necessary.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write as much as I can, every day. I’m always fighting to write,and I’m endlessly greedy.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

In recent years I’ve been experimenting with collage. It’s an admissionof defeat, and a real-time commitment, to kick writing out of my office andtake over the floor, the desk, every surface cluttered with cuttings. Detritus.I keep all kinds of old pictures and papers. I have a 3-D collage on an oldfencing mask I’ve been working on for 10 years with beads and feathers, oddjewelry and Lenin lapel pins from a summer in the USSR when I was 14. I’m awedby how much time it takes to make decisions in visual art. Part of the processis watching time dilate and get sucked into the void.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Gertrude Stein: “And then there is using everything.”

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

No fixed work—what’s important is the slowly, tectonicallyshifting stacks of books that fill my office.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

That’s a wolf of a question hiding in sheep’s clothing! I realizeI’ve been fixated on returning to things I’ve let lapse, picking up threads andweaving old time into the present. I have never grown a garden. I would like tohave the kind of time to try.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

I was a great waitress. I wanted to be a dancer. I could havetaught high school and grown that garden in the summers.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had early, obsessional love affairs with first, the cello, andthen modern dance. So I recognized the feeling when writing swept me off myfeet. That was 30 years ago this fall—1994, I had transferred to NYU fromdancing—the institution at the time took “life experience” credits, the jackpotof financial aid—and I walked in to a creative writing workshop, having neverheard of creative writing. That first class was all it took, thanks toProfessor Chris Spain. I wanted to get those feelings into words in my barehands.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

I have just seen the greatest film I’ve seen in years. It’s calledLook Into My Eyes, and it’s a newdocumentary by the painterly, underworldly, hauntingly brilliant filmmaker LanaWilson, about psychics in New York City.

I hated Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairosuntil I loved it, at the very end. It is a novel built for its ending, when ananti-love love story gives way to grief for the lost communist dream, for anEast Germany that might have veered away and solidified against capitalism to becomewhat seems like an oxymoron, a humane nation. In Erpenbeck’s telling, the pullof plentiful, cheap goods and the similarly cheap frisson of competition weretoo strong, and here we are.

20 - What are you currently working on?

An experimental, hybrid story constellation of tautly codediterations, inter-referential lyrics, frame-grabs from a contemporarycollective subconscious—working title Matterand Pattern. Theme and variation are the dangers of emotional rationality,the violence of common sense, feminist philosophy and aphorism, femaleexperience as negative space. Pattern acts on matter, matter provides contentfor pattern, language is both analysis and synthesis, thinking and knowing.