Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 140

December 26, 2021

Did I mention I'm still working on a novel?

Some further untethered selections of this novel-in-progress:

*

Patience’s great-grandfather, Alder Buckley Adams, was known in his time for his business prowess in manufacturing. One hundred years ago there was the Famous Adams Match, for example, and the Adams Biscuit. For fifty years, AB Adams earned money from every item made, received or passed through Baltimore. Half the waterfront buildings carried his name, at one point or another. After he died, her grandfather, Leland Buckley Adams took the reins of what had become the family business, providing apprenticeships and opportunities for his own children, and later, setting up a monthly stipend for his grandchildren out of the company’s profits. These dispensations continue, maintained by one of her cousins, who currently runs the company. While the money may not enough for any of them to live off, and has changed over the years, it is a worthy amount. She is surprised every time it lands in her bank account.

All she recalls of her grandfather is his grand, empty house, and his library. From her memory as a six-year-old, his house was built out of carpets and dust and forbidden rooms. His library and study on the first floor. Bookshelves as far as the eye.

According to family legend, what prompted her grandfather’s gift was the death of his brother, Archibald Cornelius Adams, when Leland was six years old. Archie was only two years old when he slipped under a carriage wheel, and was instantly killed. The loss of his brother affected Leland profoundly, watching as it nearly broke their father in half. Their mother mourned for the rest of her life, and was often found weeping in Archie’s still-preserved bedroom. Leland would watch over his own children closely. It developed in Patience’s father, and his siblings, the inability to know their own minds, away from the comfort of family. We have to look after them, her grandfather would say. And for her part, Patience slipped from the family bonds as soon as she was old enough and able, and as quickly as possible. Those airless, empty, ancient rooms.

From the back of her house, you can hear the river. From the river, the lake. From the lake, the ocean. Patience has not yet seen an ocean. She imagines how an ocean might sound.

She dreams of the ocean. Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink.

The east wind brings rain, taps at the shutters.

She has been dreaming of water. She dreams of water, although she wonders if this might be triggered by hearing the sump-pump click on from their unfinished cellar. It reeks of rust, of waste. A leak from the hose. She is surrounded by water, although none of it what she wants.

She preps her morning tea. She steps out on the porch.

*

Stella practices scales. The only time during the day I allow myself to stop moving. Thirty minutes of pause. Down the road, a pick-up truck with township logo slows down and stops, and men emerge to patch a particularly egregious pothole. Finally. I watch them work. I watch them work until they are finished, return to their vehicle and drive on. And once they do, I realize there isn’t a sound in the house.

*

When their boys were small, Felix established a dinnertime routine, asking everyone at the table in turn to say the best and worst parts of their day. Most days were benign in their offerings, but it allowed Felix and Patience to hear bits of their boys’ days at school, allowing more than the requisite silence of children. What did you learn at school today? Nothing. Who did you have lunch with? Felix claimed it was an extension of mindfulness, asking them to be attentive to a particular moment, their individual days. The stretch of weeks Hamilton would repeat the same schoolyard incident, before he understood better the passage of time. Vincent’s interest in trains, airplanes and race cars. The movement of snow, and of clouds. Of snow plows. They learned to weigh their days, and realize that tomorrow was always a way to start fresh.

*

Name any fruit or vegetable, and there is most likely a town or a village or a city that hosts a festival. An apple festival, a snap-pea festival, a currants festival. In the Valencian town of Buñol, in the East of Spain, they hold La Tomatina, a celebration of the tomato that includes a street-sized tomato fight. Wayne County, Ohio, annually hosts the Kidron Beet Festival. Are there festivals for butter, for loaves of bread, lobster or salt? A pepper festival, perhaps. Might every element of food production be allowed their own festival? Alliston, north of Toronto, is known for its annual potato festival, held for more than fifty years. I imagine kiosks that offer baked skins, French fried and even shakes, although I suspect they refrain from a similar street-sized fight to the Spanish. I imagine characters in costume, dressed as potatoes to entertain children. Just how far does it go?

December 25, 2021

happy christmas holiday what-sis goodness etcetera

There's an awful of anxiety over the past few years, but I'm extremely grateful for these young ladies. We've been laying low, and even lower, lately, given rising numbers, but we are still here. Hoping whatever it is you celebrate is safe, and everyone around you remain healthy. This is perhaps all we really require.

There's an awful of anxiety over the past few years, but I'm extremely grateful for these young ladies. We've been laying low, and even lower, lately, given rising numbers, but we are still here. Hoping whatever it is you celebrate is safe, and everyone around you remain healthy. This is perhaps all we really require.Jenna of Four Leaf Photography

December 24, 2021

Damon Potter and Truong Tran, 100 Words: Poems

It is occurring to me even as I am writing this now that this is not an experiment, or case study or collaboration or partnership. Damon is not the subject nor am I. This is a shared endeavor, an experience lived between two very different lives trying to understand what it means to be, to see the other. There is a word inside this book that neither of us can seem to hold, examine, write about with real honesty. And yet this feels like an endeavor of love. There. I just said it. I am saying this to you Damon. I am saying this to you reader. What are we trying to do if not to care for one another? To Protect, to understand, to share in the burden, to share in the comfort that is life. To see you in the hopes that you see me. In all our nakedness in our bodies and in our language. It has taken me a lifetime to write these words. It will take me a lifetime to finish this thought.

It has been a while since I’ve seen a poetry title by American-Vietnamese poet Truong Tran, so I was intrigued to see his collaboration with San Francisco poet Damon Potter,

100 Words: Poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021). The poems that make up 100 Words: Poems are very much composed via a collaborative call-and-response, as they each respond to the prompt of an individual word, set as each poem’s title. As the book asks: how does one see the other? Composed through one hundred words-as-prompts, the project is reminiscent, somewhat, of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel, In the Language of Love(1994), a book composed in one hundred chapters, each chapter prompted by and titled “based on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test, which was used to measure sanity.”

It has been a while since I’ve seen a poetry title by American-Vietnamese poet Truong Tran, so I was intrigued to see his collaboration with San Francisco poet Damon Potter,

100 Words: Poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021). The poems that make up 100 Words: Poems are very much composed via a collaborative call-and-response, as they each respond to the prompt of an individual word, set as each poem’s title. As the book asks: how does one see the other? Composed through one hundred words-as-prompts, the project is reminiscent, somewhat, of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel, In the Language of Love(1994), a book composed in one hundred chapters, each chapter prompted by and titled “based on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test, which was used to measure sanity.” Composed as a process of vulnerability and exchange, there is something curious in Tran and Potter’s shared poems, uncertain as to which poet wrote which section, a process more open and interesting to read through than had each section been credited. The point, I suppose, was entirely to bleed into uncertainty, and a closeness of reading. In terms of potential authorship, some sections appear rather straightforward, and others, less so. As they write as part of “perhaps an afterword or a new beginning,” a sequence set at the end of the collection: “i am documenting a way of getting to you. it is a map to be shared in the / hopes that one day should that day come that you can use it as a way to / get to me.” There is something quite compelling in the depth of this conversation, into the bare bones of being, speaking on elements of race and privilege, belonging and othering, difference and sameness, either perceived or actual, and how perception itself shapes our lived reality. Opening an endless sequence of questions, there aren’t answers per se, but the way in which each writer responds, both to the prompt and to each other, that provides the strength of this collection. It is the place where these two writers meet, in the space of the poem, of the page, that resounds. As the second stanza/section of the poem “why” writes:

its the question i find myself asking of just about everything in life. why did that happen? why am i here? why are we doing this? why would it matter. that you would agree to do this with a stranger. why? amendment to the word that came before. i hope we are not stranger from this word forward.

Seemingly a debut by Potter, 100 Words: Poems follows a children’s book and an artist monograph by Tran, as well as five previous full-length poetry collection: The Book of Perceptions (Kearney St Workshop Press, 1999), Placing the Accents (Apogee Press, 1999), Dust and Conscience (Apogee Press, 2000), Within The Margin (Apogee Press, 2004) and Four Letter Words(Apogee Press, 2008). A further collection, book of the other (kaya press, 2021), appeared this past year, but I have yet to see it.

self

self is ones body. self is the way one sees their own chest legs waist and or torso or internal self what we think of brains. self is how you see other people see you. receive information. self is a carriage rolling along its pulled by a horse it might be a pumpkin. self is too often a value thought thing and that feels wrong

*

to take a picture of your foot before it is eaten. to take a picture of you eating your food. the ice cream is melting. the children are crying. we forget how to be humans in the face of inhumanity. we use a telescoping stick to extend our reach. to look back. to capture what’s lost in the act of capturing.

Daman Potter and Truong Tran, 100 Words: Poems

It is occurring to me even as I am writing this now that this is not an experiment, or case study or collaboration or partnership. Damon is not the subject nor am I. This is a shared endeavor, an experience lived between two very different lives trying to understand what it means to be, to see the other. There is a word inside this book that neither of us can seem to hold, examine, write about with real honesty. And yet this feels like an endeavor of love. There. I just said it. I am saying this to you Damon. I am saying this to you reader. What are we trying to do if not to care for one another? To Protect, to understand, to share in the burden, to share in the comfort that is life. To see you in the hopes that you see me. In all our nakedness in our bodies and in our language. It has taken me a lifetime to write these words. It will take me a lifetime to finish this thought.

It has been a while since I’ve seen a poetry title by American-Vietnamese poet Truong Tran, so I was intrigued to see his collaboration with San Francisco poet Damon Potter,

100 Words: Poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021). The poems that make up 100 Words: Poems are very much composed via a collaborative call-and-response, as they each respond to the prompt of an individual word, set as each poem’s title. As the book asks: how does one see the other? Composed through one hundred words-as-prompts, the project is reminiscent, somewhat, of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel, In the Language of Love(1994), a book composed in one hundred chapters, each chapter prompted by and titled “based on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test, which was used to measure sanity.”

It has been a while since I’ve seen a poetry title by American-Vietnamese poet Truong Tran, so I was intrigued to see his collaboration with San Francisco poet Damon Potter,

100 Words: Poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021). The poems that make up 100 Words: Poems are very much composed via a collaborative call-and-response, as they each respond to the prompt of an individual word, set as each poem’s title. As the book asks: how does one see the other? Composed through one hundred words-as-prompts, the project is reminiscent, somewhat, of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel, In the Language of Love(1994), a book composed in one hundred chapters, each chapter prompted by and titled “based on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test, which was used to measure sanity.” Composed as a process of vulnerability and exchange, there is something curious in Tran and Potter’s shared poems, uncertain as to which poet wrote which section, a process more open and interesting to read through than had each section been credited. The point, I suppose, was entirely to bleed into uncertainty, and a closeness of reading. In terms of potential authorship, some sections appear rather straightforward, and others, less so. As they write as part of “perhaps an afterword or a new beginning,” a sequence set at the end of the collection: “i am documenting a way of getting to you. it is a map to be shared in the / hopes that one day should that day come that you can use it as a way to / get to me.” There is something quite compelling in the depth of this conversation, into the bare bones of being, speaking on elements of race and privilege, belonging and othering, difference and sameness, either perceived or actual, and how perception itself shapes our lived reality. Opening an endless sequence of questions, there aren’t answers per se, but the way in which each writer responds, both to the prompt and to each other, that provides the strength of this collection. It is the place where these two writers meet, in the space of the poem, of the page, that resounds. As the second stanza/section of the poem “why” writes:

its the question i find myself asking of just about everything in life. why did that happen? why am i here? why are we doing this? why would it matter. that you would agree to do this with a stranger. why? amendment to the word that came before. i hope we are not stranger from this word forward.

Seemingly a debut by Potter, 100 Words: Poems follows a children’s book and an artist monograph by Tran, as well as five previous full-length poetry collection: The Book of Perceptions (Kearney St Workshop Press, 1999), Placing the Accents (Apogee Press, 1999), Dust and Conscience (Apogee Press, 2000), Within The Margin (Apogee Press, 2004) and Four Letter Words(Apogee Press, 2008). A further collection, book of the other (kaya press, 2021), appeared this past year, but I have yet to see it.

self

self is ones body. self is the way one sees their own chest legs waist and or torso or internal self what we think of brains. self is how you see other people see you. receive information. self is a carriage rolling along its pulled by a horse it might be a pumpkin. self is too often a value thought thing and that feels wrong

*

to take a picture of your foot before it is eaten. to take a picture of you eating your food. the ice cream is melting. the children are crying. we forget how to be humans in the face of inhumanity. we use a telescoping stick to extend our reach. to look back. to capture what’s lost in the act of capturing.

December 23, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Claire Hopple

Claire Hopple is the author of four books. Her fiction has appeared in Hobart, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, New World Writing, Timber, and others. More at clairehopple.com.

Claire Hopple is the author of four books. Her fiction has appeared in Hobart, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, New World Writing, Timber, and others. More at clairehopple.com.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The first book was a slow buildup of almost a decade of writing. After that, the process sped up. Tell Me How You Really Feel , my third book, was different than the first (and second) in that I tried to break from my short story core. Attempting a novella was only possible by thinking of the chapters as stories. I had a lot more fun with it than I thought I would.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or nonfiction?

Writing poetry and nonfiction seems impossible. At least good poetry and nonfiction. I think I'm just naturally inclined to fiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm a turtle when it comes to writing. I start with bullet points in a notebook until they've built up into something. Then I lay them out on notecards and write the first draft in a notebook by hand. After that, I type it up and continue editing.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually I'm only thinking about what's in front of me. But when a series of short pieces are written in a set period of time, there's a general theme that emerges. There's something trying to get out and I try to listen to it as best as I'm able.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy them and want them to be over with as soon as possible, simultaneously.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I love this question. Yes! I think the act of writing is always posing questions on some level. Occasionally writers even try to answer them. Each book of mine has asked different questions, from struggling with what it means to be an adult to the connections we attempt to make with others.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The current role of a writer is embracing the echo chamber. The role of a writer should be anything other than what it is.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely both. It depends on the editor too. My most recent experience for my forthcoming book with Word West was outstanding. Joshua Graber is exactly the kind of editor you want. He sees what you're trying to do and he helps you get there.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The high school classic: Say something old a new way/avoid cliches.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it. But really I learned they're a lot more similar than I imagined.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work 8.5 hours a day at my regular job, read books on my half-hour lunch break, and read as much as I can during my free time. Ideas will form with enough reading of others' work and by giving myself the space to think.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading widely always helps. There are some books that I don't even think are all that good on their own but they get my brain firing in a certain way.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The sweet wood smell of dresser drawers and cedar chests.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above can be amazing influences. Also traveling and giving yourself space to play/breathe/think.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Amelia Gray, Renee Gladman, Sam Pink, Tao Lin, Scott McClanahan, etc. As far as presses go, I really like Dorothy, Soft Skull, New Directions, Two Dollar Radio, Coffee House Press, Dzanc Books, and The Cupboard Pamphlet.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

It's hard for me to differentiate between external pressure (whether real or perceived) and personal goals. I don't think about it much, just see what's ready to come out that's worth letting out.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A website developer perhaps. Coding is intriguing to me. It's language just like anything else. Maybe I would have been normal, started a family or something, but it's difficult to imagine. Sometimes I long to be normal and other times I think it seems awful.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I can't not write. I've tried to quit and it didn't work. I've resigned myself to the fact that it will always be there, like eating or brushing my teeth, and that I'll always be enamored with words and how they come together.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Semi-recent favorite books: All Fires the Fire by Julio Cortázar (trans. Suzanne Jill Levine), The White Dress by Nathalie Léger (trans. Natasha Lehrer), Pets: An Anthology ed. Jordan Castro, Imaginary Museums by Nicolette Polek, The Dominant Animal by Kathryn Scanlan, Temporary by Hilary Leichter.

Recent fave films: A New Leaf (1971), Some Kind of Heaven (2020), Home Movie (2001), Shadows in Paradise (1986), The Conversation (1974), The Long Goodbye (1973), The Swimmer (1968).

20 - What are you currently working on?

Last week, I just finished a novella about a woman who takes over the lives of others. She literally steals their identities, or at least tries. It's the most fun thing I've ever written.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 22, 2021

What I’ve been reading lately: Lydia Davis and The Paris Review, (and The Beatles: Get Back,

And while you comply with this alien style, while you fit your own prose into it, you may also, positively, react against it, in your hours off, your away hours: it was while I was translating, with such pleasure, Proust’s very long and ingenuity-taxing sentences that I began, in contrary motion, to write the very shortest stories I could compose, sometimes consisting only of the title and a single line.

Lydia Davis, “Twenty-One Pleasures of Translating (and a Silver Lining),” Essays Two

We had a couple of days in Picton visiting father-in-law and his wife over the weekend (driving straight there without stopping, driving straight home without stopping) for some holiday enjoyments, one of the rare few we’d planned that we hadn’t cancelled or postponed. Our young ladies played in the yard, went tobogganing and did their own gingerbread house crafts, among other activities. As part of the trip, I took a mound of books for potential reading, focusing on things that I wasn’t going through with the express purpose of working a review or other types of commentary, despite whatever random notes I might be sketching out. It would be good, I thought, to just sit and read. Christine, on her part, attended to her knitting.

We had a couple of days in Picton visiting father-in-law and his wife over the weekend (driving straight there without stopping, driving straight home without stopping) for some holiday enjoyments, one of the rare few we’d planned that we hadn’t cancelled or postponed. Our young ladies played in the yard, went tobogganing and did their own gingerbread house crafts, among other activities. As part of the trip, I took a mound of books for potential reading, focusing on things that I wasn’t going through with the express purpose of working a review or other types of commentary, despite whatever random notes I might be sketching out. It would be good, I thought, to just sit and read. Christine, on her part, attended to her knitting.

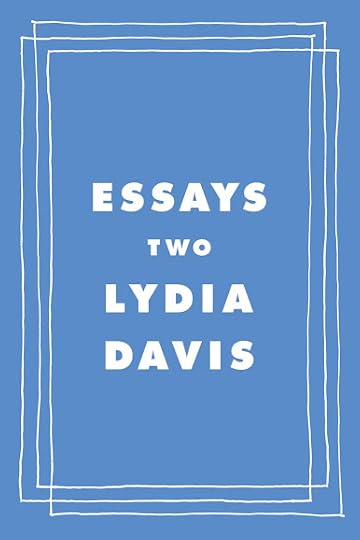

The first volume I brought along was Lydia Davis’ latest,

Essays Two

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021). I’m a huge admirer of the work of Lydia Davis, having gone through

Can’t and Won’t

(2014) [see my note on such here],

Essays One

(2019) and

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis

(2009), among others, much of which has sparked numerous different threads and direction in my own writing over the years. Just as Essays One focused on her pieces on writing and writers, Essays Two collects her various essays, lectures and talks on the process of translation, something that features heavily in her creative work. It is fascinating to hear her experiences attempting to explore languages she has either only a passing knowledge of, or simply no knowledge whatsoever, navigating an endless sequence of paths attempting to read, understand and translate a language, such as Norwegian, into English, deliberately without utilizing a language dictionary. She probably doesn’t know of Hugh Thomas’ ongoing project of translating poems into English from languages he doesn’t know, including Norwegian (I should certainly mention this chapbook, for example). She had me thinking in a number of directions, including, through attempting to translate a relative’s two hundred year old English prose memoir into a contemporary narrative poem, about the notion of the line break. It reminded me of Dennis Cooley’s classic essay on the line break, collected in

The Vernacular Muse

(Turnstone Press, 1987), an essay, and a collection, I can’t recommend highly enough. Through this piece, as well as with others, it is interesting to hear Davis speak of her uncertainty with language and form, attempting to feel her way through a puzzle to the other end, without any sense of what the final form might look like. As she offers as part of her explorations of the line break:

The first volume I brought along was Lydia Davis’ latest,

Essays Two

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021). I’m a huge admirer of the work of Lydia Davis, having gone through

Can’t and Won’t

(2014) [see my note on such here],

Essays One

(2019) and

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis

(2009), among others, much of which has sparked numerous different threads and direction in my own writing over the years. Just as Essays One focused on her pieces on writing and writers, Essays Two collects her various essays, lectures and talks on the process of translation, something that features heavily in her creative work. It is fascinating to hear her experiences attempting to explore languages she has either only a passing knowledge of, or simply no knowledge whatsoever, navigating an endless sequence of paths attempting to read, understand and translate a language, such as Norwegian, into English, deliberately without utilizing a language dictionary. She probably doesn’t know of Hugh Thomas’ ongoing project of translating poems into English from languages he doesn’t know, including Norwegian (I should certainly mention this chapbook, for example). She had me thinking in a number of directions, including, through attempting to translate a relative’s two hundred year old English prose memoir into a contemporary narrative poem, about the notion of the line break. It reminded me of Dennis Cooley’s classic essay on the line break, collected in

The Vernacular Muse

(Turnstone Press, 1987), an essay, and a collection, I can’t recommend highly enough. Through this piece, as well as with others, it is interesting to hear Davis speak of her uncertainty with language and form, attempting to feel her way through a puzzle to the other end, without any sense of what the final form might look like. As she offers as part of her explorations of the line break: Or I could take Ashbery’s answer as, really, the best an only answer, and here is how it might work: you would simply have to keep attempting your own line breaks, trusting your instincts and then listening again to what you had done, examining your line breaks, reexamining them. You would also, when you wer not writing your own poems, study the line breaks of other poets, especially poets you unquestionably admired. You would then return to examine your own, and in that way inculate in yourself a feel for line breaks, until you could confidently, without worrying, break the line “wherever it felt right.”

I took a lot of notes (including some thoughts in prose of my own, including scratchings toward a potential essay or two, and some possible fiction), but couldn’t bring myself to shape up those notes into a review, as though simply wishing to retain the experience of reading and absorbing the material. I suspect I’ll do the same here, despite Davis being one of my favourite prose writers. Sometimes it’s a matter of allowing the experience of reading to prompt my own writing and thinking, not wishing to be distracted or sidetracked through composing a review. I’ve had a similar experience earlier this year when attempting a review of Gail Scott’s Permanent Revolution: Essays (Book*hug, 2021). There are certain books that render themselves slippery when it comes to commentary, prompting me to, instead, simply prefer to lose myself in the reading and thinking. It is entirely for this reason, as well, that I never did do proper write-ups for Joshua Beckman’s paired 2018 Wave Books essay titles, despite the wealth of notes I made when working through those collections.

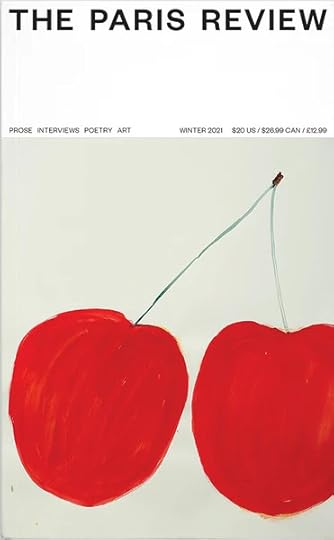

The first thing I always read in a new issue of

The Paris Review

is the interviews. Really, a good interview can be revelatory, allowing a point-of-entry for a writer with whom I’d little to no prior knowledge. Even if I never get around to reading that particular writer, there are elements that one can always pick to add to one’s own thinking around process, and how writing and books are potentially made. My mother-in-law gifted me a subscription last year for Christmas (I hope she renews), so I’ve been able to see a regular run of issues for a while now, all without leaving the house. I had begun to pick up the occasional issue prior to this, which I think had been noticed by either Christine or her mother during one of our cottage-jaunts, so perhaps that where the thought originated. I’d pick up one every year or so, depending on who was being interviewed within. The interview with Doris Lessing was deeply satisfying, for example, and I enjoyed the interview with Robert Haas far more than I’d expected, especially at his admission that even he considers that his wife, Brenda Hillman, is a more interesting poet than he is (which is actually where my own preference sits, also: sorry, Bob).

The first thing I always read in a new issue of

The Paris Review

is the interviews. Really, a good interview can be revelatory, allowing a point-of-entry for a writer with whom I’d little to no prior knowledge. Even if I never get around to reading that particular writer, there are elements that one can always pick to add to one’s own thinking around process, and how writing and books are potentially made. My mother-in-law gifted me a subscription last year for Christmas (I hope she renews), so I’ve been able to see a regular run of issues for a while now, all without leaving the house. I had begun to pick up the occasional issue prior to this, which I think had been noticed by either Christine or her mother during one of our cottage-jaunts, so perhaps that where the thought originated. I’d pick up one every year or so, depending on who was being interviewed within. The interview with Doris Lessing was deeply satisfying, for example, and I enjoyed the interview with Robert Haas far more than I’d expected, especially at his admission that even he considers that his wife, Brenda Hillman, is a more interesting poet than he is (which is actually where my own preference sits, also: sorry, Bob).

The current issue of The Paris Review is #238 (Winter 2021), and includes interviews with American fiction writer Gary Indiana and American non-fiction writer Annette Gordon-Reed. I’d heard of the first, but not the second at all. It is impossible, after all, to even hear the name Gary Indiana without being reminded of a very young Ronnie Howard singing the song named for the geography, as part of The Music Man (1962). It was fascinating reading through Indiana’s process of novel-building, and the particular political and cultural era he wrote through the midst of, the 1970s of Los Angeles, and the beginnings of the AIDS crisis. I’m aware of some of the writers and writings from this period, particularly the New Narrative writers, but I get the sense that Indiana was working a more mainstream direction in his fiction, which is how I hadn’t encountered it as of yet.

The real revelation was the interview with Annette Gordon-Reed. Apparently she was the researcher and writer who verified the long-held rumour that American President Thomas Jefferson had fathered children with a woman he owned. As the introduction to the interview begins:

Annette Gordon-Reed will always be most famous for having confirmed, beyond a reasonable doubt, the centuries-old rumors about Thomas Jefferson having had multiple children with a mixed-race woman named Sally Hemings, whom he owned. In 1997, armed with only the analog tools of traditional historiography, she made a resounding case for the relationship in Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. The book touched off a fierce debate followed a year later by the DNA testing of male descendants in Jefferson’s family, the results of which proved her theories.

It seems stunning to me, at least from this perspective of geographic and cultural distance, that this part of Jefferson’s history had only been proven so recently, as I’d long presumed it was simply known, and widely-so. It speaks, yet again, to the importance of history as being a moving target, and one that requires ongoing updates, as new information is revealed, or even better understood. Gordon-Reed, herself, sounds absolutely fascinating, as someone deeply engaged and curious, seeking out answers to questions that had either been deliberately buried, or ones that other historians simply hadn’t thought to pose. She sounds, in all honestly, utterly brilliant.

Other than that, I haven’t dipped into much of the issue, although I was intrigued by the poem “Strange as the Rules / of Grammar,” by Terrance Hayes, a poem that ends:

The scar is so old others must tell you

how it was made

It doesn’t count as reading, but a week or two back, I spent a few nights watching that new Beatles documentary, the eight hours of watching them noodle around to create the Let It Be album, culminating in that 1969 rooftop performance—their first public performance in three years, and their final public performance as well. I saw some on social media complaining about the documentary, not able to get through that first hour, citing the level of complaining and bickering (which is fair; that first hour or two has some rough spots in it). But I found it utterly fascinating in the same way I used to enjoy

Inside the Actors’ Studio

: conversations on and around process, building and creation, which is why I even bring it up in the context of this assemblage of reading notes. How does anything get made? Even for the Beatles, which were, at that moment, the biggest band in the world, sitting through uncomfortable stretches and bickering and nonsense and the pressure of deadlines. Christine had no interest in the series at all (she also ignored the George Harrison doc, which I had to watch after she’d gone to bed, also, as well as a Brian Eno doc I caught last year). She offered that part of the appeal for such a documentary is having to be actually invested in these particular musicians and their music, which is fair enough. I suppose she was just never into the Beatles, whereas I spent much of my teen years attentive to same, including and up to 1987, celebrated in certain media as the “second summer of love,” pushing the 20th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s, and other elements of the 1960s. I think I watched Yellow Submarine 25-plus times during that period. My ex-wife even had her 1960s-era Beatles 45s, left over from elder brothers. And every Sunday morning, an hour long radio program I caught that featured music by the Beatles. So I suppose I was the right audience for this thing. The documentary was fascinating in the way songs emerged, and the back-and-forth between the band, both individually and as a group, attempting to shape and hammer whatever came into their heads into workable songs, some of which were abandoned, and others reshaped into long-familiar classics.

It doesn’t count as reading, but a week or two back, I spent a few nights watching that new Beatles documentary, the eight hours of watching them noodle around to create the Let It Be album, culminating in that 1969 rooftop performance—their first public performance in three years, and their final public performance as well. I saw some on social media complaining about the documentary, not able to get through that first hour, citing the level of complaining and bickering (which is fair; that first hour or two has some rough spots in it). But I found it utterly fascinating in the same way I used to enjoy

Inside the Actors’ Studio

: conversations on and around process, building and creation, which is why I even bring it up in the context of this assemblage of reading notes. How does anything get made? Even for the Beatles, which were, at that moment, the biggest band in the world, sitting through uncomfortable stretches and bickering and nonsense and the pressure of deadlines. Christine had no interest in the series at all (she also ignored the George Harrison doc, which I had to watch after she’d gone to bed, also, as well as a Brian Eno doc I caught last year). She offered that part of the appeal for such a documentary is having to be actually invested in these particular musicians and their music, which is fair enough. I suppose she was just never into the Beatles, whereas I spent much of my teen years attentive to same, including and up to 1987, celebrated in certain media as the “second summer of love,” pushing the 20th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s, and other elements of the 1960s. I think I watched Yellow Submarine 25-plus times during that period. My ex-wife even had her 1960s-era Beatles 45s, left over from elder brothers. And every Sunday morning, an hour long radio program I caught that featured music by the Beatles. So I suppose I was the right audience for this thing. The documentary was fascinating in the way songs emerged, and the back-and-forth between the band, both individually and as a group, attempting to shape and hammer whatever came into their heads into workable songs, some of which were abandoned, and others reshaped into long-familiar classics. It is odd, to me at least, the slight backlash the documentary has prompted, articles suggesting “Its not their fault we thought them the greatest rock band in the world.” An article in The Washington Post was titled “The Beatles are overrated. That’s our fault, not theirs.” One has to think of context, certainly. Weren’t they the perfect storm of talent, industry, timing, everything? Brian Epstein wouldn’t let them tour the US until a Number One single on American charts, whereas The Animals just went over (where are they now?), or the sheer onslaught of songs writ and sold by Paul/John, which I’m sure allowed them enough financial comfort to hang about and write their own material without requiring side-gigs. I mean, context is everything, isn’t it? It seems silly as a response, and a complete misunderstanding of who they were within that particular period, and what they were actually accomplishing. “We don’t like them now because culture has progressed further”? It has been fifty years, after all. I mean, really.

December 21, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Gale Marie Thompson

Gale Marie Thompson is the author of

Helen or My Hunger

(YesYes Books, 2020),

Soldier On

(Tupelo Press, 2015), and two chapbooks. Her work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Tin House Online, The Adroit Journal, jubilat, BOAAT, and Crazyhorse, among others. She has received fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. She is the founding editor of Jellyfish Poetry and co-host of the arts advice podcast

Now That We’re Friends

. She lives in the mountains of North Georgia, where she directs the Creative Writing program at Young Harris College.

Gale Marie Thompson is the author of

Helen or My Hunger

(YesYes Books, 2020),

Soldier On

(Tupelo Press, 2015), and two chapbooks. Her work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Tin House Online, The Adroit Journal, jubilat, BOAAT, and Crazyhorse, among others. She has received fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. She is the founding editor of Jellyfish Poetry and co-host of the arts advice podcast

Now That We’re Friends

. She lives in the mountains of North Georgia, where she directs the Creative Writing program at Young Harris College. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? Soldier On came out in 2015. It was my graduate thesis that I finished in 2011, so my relationship to it was a little complicated. But now I feel more connected to it, and am pretty proud of that young writer. I miss the joy in those poems, and the whimsy in their imagery. I loved language then. I don’t think Soldier On changed my life—or, it taught me a lot by not changing my life. A lesson that I keep learning is that I should never rely on outside approval when it comes to writing, that I should write for myself, for my own goals and objectives. Of course, this is near impossible to someone like me who has sought outside approval for almost everything. Publishing Helen in the middle of 2020 has retaught me this lesson as well.

Helen or My Hunger has been the most openly personal collection for me by far, and therefore the most difficult to write (and to read in public, eek!). Through Helen of Troy, I was able to address anger and misogyny and dysphoria more directly, as well as trauma and mental illness, while also working to build a kind of hope in the speaker’s story itself, or a way to come back and face what is there (“that I deserve / this riddled hunger”). My new poems post-Helen attempt to build on this even further, without the scaffolding of myth. I know this new work is asking me to give things a name, to put language to subject matter more directly. There is a succinct body and self writing these poems, a self at stake, and I think I am moving toward facing this self even more directly, for better or worse.

Since Soldier On, I got my PhD and am now directing the Creative Writing Program at Young Harris College in North Georgia. My new work is harder to write—mainly because I’ve become a bit distrustful of writing anything, especially in relation to the performativity of social media. I’ve found my new work harder to love, or feel joy in. But I do think it’s work I need to do, and hopefully produces better poems. I’m also spending a lot of time working closely with undergraduates, trying to decipher the code of “good” (or “effective”) poems, and so at the moment it is kind of hard to write a poem and not think about the pretty little machine I can make. I know that poems are crafted machines, objects of wonder, but for me the artifice of it can sometimes feel performative. So I’m working on reconciling that with my writing process. Any tips are welcome!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? I’ve been singing and playing music my entire life, so I think it just came naturally to see language as pattern, as little jewels of sound you can keep with you and turn over in your hand again and again. I also think it helped me trust my intuition, to lean into what feels right, or sounds right. That may be something fiction writers have as well, but seeing words as patterned sound more than anything helps me lean toward the lyric. I almost wanted to be a fiction writer in college, but after my first fiction class I realized it wasn’t going to be sustainable for me. I wrote the two short stories I wanted to write, and that was it. I was very proud of them, but I didn’t feel the need to make any more. But with poetry, something new always comes in.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? My process is full of hesitancies and stumbles, notes and notes and notes until I build solid drafts from those notes. Over the last few years, I’ve paid more attention to revising, and taken riskier moves than I had before. I’ve felt more confined in what I can envision for a poem, and so I often ask other people for advice or ways to approach something. One new thing that has come up in the last few years is that I will write an essay and realize it’s a poem, or a poem and realize it should be an essay. Things also take a bit longer the last year or so because of my new job. I’m not someone who can write in the small minutes of the day. I need to be able to hyperfocus, and that’s not super compatible with having a stressful job with a lot of responsibilities. I’m becoming accustomed to the fact that most of my poems will have to be written in the summer, or over the weekend.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? Except for Helen, which is of course a larger project, I generally don’t tend to think in terms of project. I do go through periods of obsessions, or thematic resonances, where I know that the poems I write are going to be in the same book, and that the book is going to be thinking about certain things. But I honestly try not to think about it too soon, because as soon as I have that realization—I’m writing a book!—I lose touch with the process. It happens when I bowl, too. If I start to notice that I’m bowling well, I can’t bowl at all after that. Sometimes, though, I’ll write a poem that really pulls at the different strings of thought I’m working through, and that’s when I’ll start to see a collection building.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? I do enjoy readings. They’re as close to stand-up as I’m going to get, haha. I do wish I could be more free with them, though. I get very conscious of how I look, how I act, and I zone out so much that I miss out on the embodiment of actually reading the poem, sometimes. That being said, though, I found so muchjoy and power in reading the poems from Helen or My Hunger. I got to relish in the sounds and patterns and battle cries that are a part of the series, and people seemed to really like it; I felt so supported when I read from it. When Helen came out last year, I decided that this year was going to be the year I was going to go on book tour! Then we had a little pandemic that changed that idea.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? Helen or my Hunger contends with a main theoretical concern that I’ve been battling for a while: that there is harm, as well as power, in putting something into language. That even to give words to an experience or feeling makes it real, but also takes away from the wholeness of an experience (or as Clarice Lispector wrote, “coherence is mutilation”). That for better or worse, there is always ego in the I of the poem (or any writing). In Helen, this concern of course shows up most explicitly by tackling the oppressive narratives of Helen of Troy, and of women in general. But instead of refuting these myths by saying “but this is Helen’s real story!” the book ends up questioning the idea of the “correct” story at all. I wanted to show that we will never be able to access any “real” Helen of Troy, or her story. As the poems in the book move further out and into my own experiences, the book questions the artifice of turning anyexperience, especially painful experience, into language. So much of the book is about the struggle to write at all: I braid into others’ layers. My hands fill others’ pockets. Here I am slipping on the same page. Even my handwriting changes when trying to get to you. Scratching into the screen I get only echoes. / Tell me what deserves intimacy, Helen. The public orange of writing, too much, much too much. How do I decipher my own name in its largeness?

I’ve had a hard time, especially in the last few years, battling the idea of the writer’s ego. The act of turning experience into language that ornaments, that makes patterns of beauty, makes it all feel inauthentic and theatrical. I’ve obviously been struggling with my writing process because of this main concern: how do you write about turning off a writer’s ego without using the writer’s ego? How do you use language to navigate your experiences when you don’t think your experiences are worth language at all?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be? Clearly based on my last answer I’m a little unsure about my role, but I do know that writers have saved me time and time again. Writers give reality to unspoken experiences, voices, or ideas, they mark time passing, they create and sustain communities that we find mystery and magic in, they help us recognize ourselves in another, and to recognize another in ourselves. They give us a world to aspire to, or they show us our world and press us to change it, they ask us to be moved—and here is where I quote Adrienne Rich again: “poetry / isn’t revolution but a way of knowing why it must come.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? I think it depends on the editor and the project, really. I do think deeper and more clearly when I’m in dialogue with another person, and so I often find that outside editors can make suggestions that make the nebulous, intimidating world I’ve created into something coherent that a reader can take part in. KMA at YesYes Books was my editor for Helen or My Hunger, and I don’t know where the book would be without her insights and questions, pressing me to go further.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? This part in James Tate’s introduction to the Best American Poetry 1997: “When I make the mistake of imagining how a whole poem should unfold, I immediately want to destroy that plan. Nothing should supplant the true act of discovery. […] What we want from poetry is to be moved, to be moved from where we now stand. We don't just want to have our ideas or emotions confirmed. Or if we do, then we turn to lesser poems, poems which are happy to tell you killing children is bad, chopping down the rainforest is bad, dying is sad. A good poet would agree with all of those sentiments, but would also strive for an understanding beyond those givens.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? I don’t really (yet) have a writing day that is combined with a work day. Right now I’ve taken on a bit much, so I’ve been in survival mode for a while. I tend to hyperfocus to get any writing done, so I use weekends and summer breaks to do the bulk of my work. But it always starts with reading. I need to see other people making language so I can feel comfortable doing it, or remember even what words are. My longer answer is here, on my (small press) writing day.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? Reading. Always reading. It gets me out of the vacuum. A few books I always turn to: Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, Inger Christensen’s alphabet, Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, Marni Ludwig’s Pinwheel, and Bhanu Kapil’s Ban en Banlieue. I am also learning that if my writing gets stalled, it’s not always a bad thing. I am learning to be better at listening, and letting things marinate. Of course, it means fewer poems, but it’s much healthier for me. If I try to write and I’m not ready, nothing good is going to happen.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Gardenias. My old house in South Carolina had this huge gardenia bush outside that bloomed like, eight times a year, and my mom would cut the blossoms off and float them in water on the kitchen island. Also, the smell of vanilla when I’m baking.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? Nature documentaries have been my go-to for years, as well as music. I also read a lot about science, especially physics and astronomy. Parts of Helen are written after watching a documentary about the Northern Passage, the indigenous cultures that comprise it, and how climate change is affecting their lives in the Arctic. Because of this film I also began listening to throat-singing artists, and had such an emotional response to it that it ended up being a big part of the book’s resolution. I also did a lot of adult ballet classes for a few years that helped me navigate some big ideas in my writing. I also feel like baking is the form most similar to poetry, for me. All of these involve the beauty of intuition, and the tiny alterations a craftsperson makes onto each iteration of the object. The form becomes the telling: The palette marks on a cake, the way an ankle bone holds fifth position, the tiny fluctuations in a throat-singer’s breath, how nature carves itself into itself.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? All of the above books, along with Adrienne Rich, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath (poems yes, but the journals are so necessary), Paul Celan, Elena Ferrante, and the work of my friends. I also owe most of my dream of being a writer to reading the diary of Anne Frank over and over again as I was growing up.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? 1) write a non-poetry book, maybe a novel, 2) write a song, 3) actually write habitually in a journal.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? I was going to be a veterinarian, and I still dream about it. That, or something in the medical field. But my life is so different that it’s hard to imagine that now. But I loved biology and math, I loved learning languages, and I felt like I had to give those things up in college to focus on writing. I also have a secret wish to be a singer-songwriter-slash-rock-star.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? I think I’ve used it to tie myself to the world a bit. It sometimes is very easy to feel like you’re slipping away from the world—from people, or from your own life, your own experiences, your life’s purpose. Memories blur, experiences and faces blur, and time becomes a flat circle when I can’t use language to make it real. I want to be able to see and experience this world, not just pass it through; I don’t want to be a sieve, and I think writing helps me do that.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? I haven’t been able to read too many non-required books lately, but over the last year I read The Overstory and The Great Believers and both ripped my heart out and made me want to be a new person. I felt like I wanted to get a print copy of The Great Believers and read it like a sacred text every day, and I’ve only felt that way about a very small number of books. In terms of poetry, I got to teach Ross Gay’s Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude and Kiki Petrosino’s White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia this year, both books I had fallen in love with and couldn’t WAIT to share with my students. Molly Brodak’s The Cipherwas an incredible read as well, and come to think of it, explores a lot of the same questions I’ve been thinking about in this interview…just 100x more brilliantly and skillfully—the limits of knowing and seeing, and how we come to be known and seen. Oh! And Emily Skaja’s The Brute was such a thrilling, delicious recent read as well.

19 - What are you currently working on? I’ve been working on this manuscript called Dummy Prayer for a number of years now, and new poems come in each year and change its face a bit more each time. During the pandemic I’ve been hiking and reading in the mountains around where I live, and even before the pandemic I was living a pretty isolated life here in North Georgia. Over the last few years, I’ve had a few friends pass away unexpectedly, as well as some other losses and oblivions and changes that (like always) have affected my relationship with the world. So, all of that together means that my poems are very much influenced by the messiness of nature in Appalachia, along with the messiness of loneliness and grief, of a longing for connection. In these poems, nature is constantly working on its own disappearance. The rotting plants and animal bones and organic matter are housed in the same world as the ramps and bellflowers on the verge of opening. All this to say, I’ve been thinking quite a bit about how we connect with each other, or, to quote Adrienne Rich, “the grit of human arrangements and relationships: how we are with each other.” The frictions in communicating public and private experiences to each other. And so I was thinking about these arrangements, how we keep each other alive, and that’s a huge part of Dummy Prayer.

The title “Dummy Prayer” comes from an episode of The West Wing Weekly podcast, when Josh Molina describes performing a prayer for Passover seder on an episode of Sports Night. (For the sake of clarity: I am not Jewish, I just love theology). Because he wasn’t literally praying to God in this episode, he decided to use the substitutes (adoshem/elokeinu) for the name of God to protect it. He described this use as “a kind of dummy prayer,” a fake or model prayer to use as a reference. This concept resonated with me so strongly, the idea of following through with the ritual act, still going through the gestures, still living in the reality of it and understanding its meaning and purpose—even if it’s outside of its intended use. The impacts of ritual on community and communication outside of a historical, literal meaning. And it made me think about the importance of those almost-performative gestures in building trust and connecting with people. In its simplest terms: That you do need to call your mom on Fridays, no matter what; that cliché words of comfort might be more helpful now to your friend in need than anything else; or that you do need to say I love you before leaving no matter how pissed off you are at your partner/parent/etc. It is how we treat ourselves and each other, it is a longing for connection, it is the calling out, even if we never get an answer.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 20, 2021

Etcetera : some commentary, and a few new(ish) poems,

Thanks to Katie Naughton's Etcetera, I did some short write-ups on particular works by Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Susan Howe, Joshua Beckman, the anthology on grief co-edited by George Bowering and Jean Baird, and the infamous 1960s Canadian poetry anthology by Eli Mandel (through which I discuss Bowering and John Newlove), all of which you can read here (alongside two new poems, as well). Also, Nate Logan was good enough to post a poem of mine (originally composed for Scientific American, but I couldn't figure out how to submit to them) up at his buffalopluseight. So many things!

Thanks to Katie Naughton's Etcetera, I did some short write-ups on particular works by Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Susan Howe, Joshua Beckman, the anthology on grief co-edited by George Bowering and Jean Baird, and the infamous 1960s Canadian poetry anthology by Eli Mandel (through which I discuss Bowering and John Newlove), all of which you can read here (alongside two new poems, as well). Also, Nate Logan was good enough to post a poem of mine (originally composed for Scientific American, but I couldn't figure out how to submit to them) up at his buffalopluseight. So many things!December 19, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tony Trigilio

Tony Trigilio’s

[Photo credit: Kevin Nance] recent books of poetry include

Proof Something Happened

, selected by Susan Howe as the winner of the 2020 Marsh Hawk Press Poetry Prize (Marsh Hawk Press, 2021), and

Ghosts of the Upper Floor

(BlazeVOX [books], 2019). His selected poems, Fuera del Taller del Cosmos, was published in Guatemala in 2018 by Editorial Poe (translated by Bony Hernández). He is editor of

Elise Cowen: Poems and Fragments

(Ahsahta Press, 2014), and coedits the poetry journal Court Green. He is a Professor of English and Creative Writing at Columbia College Chicago.

Tony Trigilio’s

[Photo credit: Kevin Nance] recent books of poetry include

Proof Something Happened

, selected by Susan Howe as the winner of the 2020 Marsh Hawk Press Poetry Prize (Marsh Hawk Press, 2021), and

Ghosts of the Upper Floor

(BlazeVOX [books], 2019). His selected poems, Fuera del Taller del Cosmos, was published in Guatemala in 2018 by Editorial Poe (translated by Bony Hernández). He is editor of

Elise Cowen: Poems and Fragments

(Ahsahta Press, 2014), and coedits the poetry journal Court Green. He is a Professor of English and Creative Writing at Columbia College Chicago.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I was ecstatic when my first book of poems, The Lama's English Lessons (Three Candles Press, 2006), was published. The book gave me an incredible jolt of confidence. I'll always be grateful to publisher Steve Mueske, an excellent poet in his own right, for believing in those poems. My overall body of work is eclectic, but looking back on that first book, I can see that it's sort of a template for the kinds of poetry I'm still interested in: autobiographical lyric poems; historically-based or documentary poems; poems that experiment with traditional forms; and poems that engage difficult questions of family dynamics. When The Lama's English Lessons first came out, I felt like poets were dividing themselves into distinct camps that pitted so-called narrative poets against so-called experimental poets. Since the publication of this first book, I've tried to blur the boundary between these two camps in my poems (and I'm glad to see fewer and fewer poets invested in dividing ourselves into these kinds of camps).

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My introductions to poetry were music and song. As a young child, I was obsessed with my sister's Beatles records. "The Fool on the Hill" and "Eleanor Rigby," especially, produced emotional reactions in me that later resembled my response to poetry. As I got older, it became clearer to me that I wanted to generate the same kind of feelings in readers that songs and poems produced in me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My individual poems (and segments of poems that are part of longer, book-length projects) always start as a many-tentacled mess that reaches in too many directions. In the early drafting process, I'm inspired by William Blake's dictum, "You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough." It takes me a lot of time, though, and many drafts, before I can actually sculpt the what-is-enough from the more-than-enough. Some poems definitely come quickly. But for the most part, I have to be patient with myself that I need many drafts before the work really starts to feel like a poem.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

It's both for me, depending on what I'm working on. Often, I'm writing shorter pieces that I trust eventually will cohere into a larger book. But I also love composing book-length poems. I'm working on the fourth volume of my ongoing project, The Complete Dark Shadows (of My Childhood), which I started in 2011. The first three books were published in 2014, 2016, and 2019. For this project, I'm watching all 1,225 episodes of the old U.S. daytime soap opera Dark Shadows , a gothic soap that featured a vampire as its main character. I write one sentence in response to each episode, and I use each sentence as a conduit for autobiographical excursions. (When I was a small child, I watched the show every day with my mother, so autobiography is at the heart of my childhood viewing experience.) My newest volume (in progress) and Book 3 are both composed in hybrid poetry/prose forms, which is also a departure from the kinds of books I've written previously.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. The circuit opens when I start writing the poem, and it doesn't usually feel "complete" until I've read the poem for others.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think most of all my interest lies in fusing the autobiographical mode with the documentary or historical mode. I'm interested in language and situations that emerge from the collision of an individual's self-consciousness with an individual's historical moment. Also, as I mentioned earlier, I'm still invested in poems the dramatize family and community belonging, especially poems that explore immigrant identity (my parents were first-generation) and working-class identity. In my documentary poems, I try to tell an unofficial version of the histories we have been told to accept as master narratives.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

For me, the role of the writer is to dramatize for their readers new ways of seeing the world. Sometimes those ways of seeing can be internal and psychological, and sometimes they're social and political.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It's essential for me. I see my work with outside editors as collaborative relationships; every book I've done is a collaboration between myself and the editor/publisher. I feel the same about my work as a coeditor for the poetry journal Court Green .

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

It's probably the quotation from Blake I mentioned earlier: "You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough." Blake's remark reminds me that the editor-who-lives-inside-my-head needs to go away during my initial, generative drafts so that I don't overthink the early invention stage of the writing process. This editor-in-my-head definitely needs to come back for later drafts. But the editor-in-my-head's self-judging voice tries to dominate, and it's important for me to mute that voice in the earliest stages of a piece of writing.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

It took a while for me to be comfortable moving back and forth between these genres. But it's much easier now because I have a decent sense of which projects/ideas/feelings are best suited for poetry and which are best suited for critical prose. I'm drawn to both kinds of writing because of the way they light up both hemispheres of my brain. I want my poems and critical prose to be equal parts emotion and intellect.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't know that I have one particular routine. Instead, I try to adapt my routine to what else is happening in my life at any given time (some periods allow me to set up a solid routine; but other periods require that adapt to busy times at work or in my home life). I've learned over the years, though, that the best times for me to write are early in the morning and late at night. There's something in the quiet, sparse ambience of those times of the day sparks me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Usually, I can get back on track by reading. Paying attention to how other poets and prose writers are working with language/vision/mystery helps realign my voice productively. When I'm stalled, I also turn to music, movies, or comics so that my imagination can still be energized without obsessing on what's happening (or not happening) with my writing.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The tangy, fungal smell of a Great Lake in early spring. I grew up a couple miles from Lake Erie. I currently live a block from Lake Michigan.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I'm also a musician (drums and percussion), so music is a definite source for my books, whether directly or indirectly. I compose poems as a musician, and compose music as a poet. I'm also hugely influenced by movies and television (especially, of course, by late-1960s/early-1970s goth vampire soap operas, haha!).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

As for poets: William Blake, George Oppen, Harryette Mullen, Bernadette Mayer, Allen Ginsberg, H.D., Joanne Kyger, Audre Lorde, James Schuyler, and Denise Levertov, among so many others. Fiction writers like Don DeLillo and are also huge influences on how I experience writing and how I move through the world, as is the historian and philosopher Michel Foucault. As I mentioned earlier, comics are a big part of my creative process. Bill Griffith's Zippy the Pinhead comic strip made me want to write poetry (and introduced Dada and Surrealism to me), and Harvey Pekar's American Splendor taught me how to experiment with narrative and make it strange.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

One of my dreams is to play drums and percussion in Eugene Chadbourne's band.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In my twenties, I left the music business to go to graduate school, so if I hadn't become a writer, I probably would've continued playing and recording music. I still do, though music is more of a serious hobby these days. If writing and music hadn't worked out, I would've probably tried law school. Back in high school and early college, I wanted to become a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

More than any other art form, writing makes the world coherent and representable to me. But music comes really close.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book of poems I read is Wanda Coleman, Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems (ed. Terrance Hayes), and the two best novels I've read recently are Sigrid Nunez, The Friend, and Don DeLillo, The Silence. Also, since I read a lot of comics and graphic novels, I have to add that the last great one I read is Derf Backderf's Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio. (I did my undergraduate degree at Kent State, and I'm never far removed from my outrage at the infamous 1970 National Guard shooting that killed four students and wounded nine.) I haven't seen many films since the pandemic hit. But of the films I saw right before the pandemic, my favorites are Parasite (dir. Bong Joon-ho) and Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice (dir. Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman).

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm just past the halfway point of Volume 4 of The Complete Dark Shadows (of My Childhood). As with the third volume, this one is a poetry/prose hybrid. I recently transitioned from a series of prose poems into a pantoum. I'm spending this week trying to write myself back into prose.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 18, 2021

Camille Martin, Blueshift Road

Identity as Norwegian Pagoda

It never was the right time to travel to Rome

to find yourself. Autumn fog and rainy wind

are symbols of crushed hopes—miasma

birthing counterfeiters who clutter the globe

with shields of Sistine junk. Praise the miasma.

Who wants to be gulled by the hand

that pulls back the curtain? Better to re-invent

metacarpals for houseflies, to hullabaloo

down the pike tearing blank after blank to bits.

Rome’s an imposter. Mimicry ripples

from the dying words of the last spelunker on earth.

Surf’s roar summons beached puddles ad infinitum.

Bred in chiaroscuro, savvy pilgrims fashion

caves of ice adorned with sequined plums

and settle in for a long night.

It has been a while since we’ve heard from Toronto poet Camille Martin (and some of us have missed her, truly), the author of the trade collections Sesame Kiosk (Elmwood CT: Potes and Poets, 2001), Codes of Public Sleep(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2007), Sonnets (Shearsman Books, 2010) and Looms(Shearsman Books, 2012), as well as a variety of chapbooks, including Plastic Heaven (New Orleans: single-author issue of Fell Swoop, 1996), Magnus Loop (Tucson, Arizona: Chax Press, 1999), Rogue Embryo (New Orleans: Lavender Ink, 1999), If Leaf, Then Arpeggio (above/ground press, 2011) and Sugar Beach (above/ground press, 2013). Her fifth full-length collection, and first in nearly a decade, is Blueshift Road (Toronto ON: Rogue Embryo Press, 2021), an assemblage of poems working a variety of forms, continuing numerous structural threads that have existed throughout her work [see the text of my 2011 Influency talk in her Sonnets here], from the sonnet to the short sequence to the prose poem to the open lyric. As she discusses one of the poems that made its way into the eventual collection back in 2014, over at Touch the Donkey:

Each of my books seems to find its own centripetal pull. Sometimes it’s formal, as in Sonnets (a book of variations on the form), or as in R Is the Artichoke of Rose (a collection of short-short poems). And sometimes it’s thematic—even if loosely so—as in Codes of Public Sleep, in its way a tale of two very different cities (New Orleans and Toronto).

“Page Dust for Will” will probably be woven into a manuscript with the working title Blueshift Road, some of whose poems find their inspiration in the sciences, especially astronomy.

As part of that interview, Martin offers that the manuscript, then very much still in-progress as a singular unit (poems out of the chapbooks Magnus Loopand Sugar Beach are included in the collection), was working inspiration from “the sciences, especially astronomy,” although there seems just as much conversation around distance, and a search for both meaning and identity. She writes of not only shifts of air, weather and of attention, but of uncertainties around them. As her title poem opens: “Recalling a slight breeze of little consequence / on an unremarkable cloudless morning, // except for wearing blue plaid, / picking blackberries along an ancient // riverbank. And the breeze, of course.”