Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 136

February 5, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Alyda Faber

Alyda Faberhas published two poetry collections,

Poisonous If Eaten Raw

(2021) and Dust or Fire (2016), with Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry. Her poems have also appeared in a chapbook, Berlinale Erotik (2015), and in Canadian and Frisian literary magazines including Arc Poetry Magazine, Contemporary Verse 2, the Fiddlehead, the Malahat Review, and Riddle Fence. She lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she teaches Systematic Theology and Ethics at Atlantic School of Theology.

Alyda Faberhas published two poetry collections,

Poisonous If Eaten Raw

(2021) and Dust or Fire (2016), with Goose Lane Editions/icehouse poetry. Her poems have also appeared in a chapbook, Berlinale Erotik (2015), and in Canadian and Frisian literary magazines including Arc Poetry Magazine, Contemporary Verse 2, the Fiddlehead, the Malahat Review, and Riddle Fence. She lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she teaches Systematic Theology and Ethics at Atlantic School of Theology. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Getting the first book published was heartening and humbling—especially the excitement of Goose Lane Editions’ poetry board about my manuscript, and their dedication to making it the best book it could be. The family themed poems in Dust or Fire emerged over almost a decade, beginning with a suite of poems that springboard off odd Frisian sayings, including, “I may visit you, but I’m not God.” My father died when I was finishing the book, so the eulogy (poem) I wrote years before his death settled into the sofa of the collection as if it had not been an early guest. My parents’ first meeting at the Leeuwarden train station is the subject of a long poem, and the closing (short) poem. Among other things, the book evokes parental hauntings (haunting not limited to the dead). In the second book, Poisonous If Eaten Raw, the father stands in the wings, while the shape-shifting mother—the many mothers in the mother—takes the stage in wild array of performances—as funnel spider, a chickadee, Geddy Lee, and more. The book stops at seventy-one portraits without exhausting the possibilities; perhaps, as my friend Kathleen Skerrett suggests, opening out into questions: “what is a metaphor? what is a portrait?” My impression is that the poems in the second book have more sonic richness and structure, an impression confirmed by a colleague, David Deane, who refers to the second collection as “stylistically more ‘abundant’” than the earlier work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I spent years writing (though not publishing much) short fiction, or auto-fiction as it’s called now, and I came to poetry afterwards. In 2007, I attended a poetry reading in Halifax given by Ken Babstock and Mark Strand—something in Babstock’s temperament jarred an internal shift in me, the realization that I could and should try writing poetry, and I cast my lot with the poets from that point on.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A writing project takes a long time to emerge for me. Years ago, at a conference dinner, I recall a man saying (in a Southern accent), “writin’s a temperamental thing”—my temperament requires long gestation, not quite as long as the cicada, but long. In a letter, Emily Dickinson says she’s becoming a snail. I’m a writerly snail. My first drafts are very messy, but within them a few shiny trails take me to feeding spots.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem usually begins with attention—to what I see on walks, hear in conversations or on the radio, read, anything I find jarring or delightful or resonant in some way. I began writing with a more fragmented approach, poem by poem. Now I often have a sense of a larger project but it doesn’t necessarily work out the way I originally envisioned it.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

There is a creativity to public readings—selecting poems that talk to each other in unanticipated ways because they’ve been placed next to each other. The Q & A after readings can intensify the question: what have I done in this book? At the same time, I find it takes immense psychic energy to do readings, even, or especially because of the pleasure involved.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes, I think so, but I may not be the best person to identify them. I explore questions rather than answering them—any question that persists over time is a question I want to engage—these questions have greater ethical moment and momentum for me. How do we avoid “the avoidance of love” (to cite the title of a brilliant Stanley Cavell essay)? How do we limber our capacity for witness to our own strangeness, the strangeness of others, and the world? How might “the unknown that remains unknown” (Thomas Merton) keep burbling up, a spring agitating the sands inside us?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

A writer, and other artists, manifest a non-dominant way of thinking, sometimes called right brain or gestalt thinking, that is critical to social well being. In her book, The Experience of Meaning, Jan Zwicky contends that the sidelining of gestalt thinking in favour of “thinking as calculation” (working in discrete steps, breaking down into parts) is implicated in our climate crisis. While she admits the importance of calculative rationality, she finds the practice of gestalt thinking at the heart of our experience of meaning, of resonance to and within the world, a practice of perception and discernment. “Real thinking does not always occur in words; it can decay under analysis; its processes are not always reportable. This means that real thinking is in some sense wild: it cannot be corralled or regulated” (95 italics added). I often have the sense that my thinking, out loud, sounds zigzaggy, baggy, and I tend to devalue this in favour of speech that sounds as if it’s walking a straight line. I felt surges of joy in response to Zwicky’s affirmation of wordless or baggy thinking as a source of insight, beauty and vision, making the experience of reading of her book unforgettable hours of delight.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Difficult and essential. I can’t see the tonal drift of a work as a whole when I’ve been immersed in it for years. I rely on regular meetings with a poetry group, and occasional writing workshops to jumpstart or re-invigorate what I’ve been working on in a solitary way. Are others hearing what I’m hearing in this poem? How far can I go into idiosyncrasy, and still communicate? The intricate work comes at the end, with a poem by poem walk through of the manuscript (for both books, with Ross Leckie). He’s a tough, generous editor, who, among other things, has helped me distinguish when a brief, delicate poem is finished or when it’s a sketch of a potentially much longer poem. When needed, he’s taken the car apart to analyze the mechanics of particular poems.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I often recall Sue Goyette saying, “Allow yourself to write a really bad poem—I mean really bad.” Also, “you begin again with nothing.” As I hear her, writing is a spiritual exercise, an acceptance of our fallibility, without which we can’t love ourselves and others. A long lesson to learn.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

The energy and time I have for writing used to be expended on critical prose almost exclusively, essays on theology/religion in film and literature. Then for a time I was writing only poetry, and while I’m planning to continue in this vein, I’d like to explore hybrid forms where ideas move through complex poetics as in Anne Carson’s Economy of the Unlost and Decreation: Poetry, Essays, Opera; Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and Argonauts, and Jan Zwicky’s “Lyric, Narrative, Memory” in A Ragged Pen, and her books, Wisdom & Metaphor, and Lyric Philosophy.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A typical day begins with yoga and feeding animals (cats and me). I have to schedule writing, since my work as a professor often involves many brief but urgent tasks (administration) and the intensity of teaching. I prioritize writing in the first part of my day whenever I can, and have the good fortune to often have months of sabbatical or large chunks of summer term to devote almost exclusively to writing.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The same things I turn to when it is going well: books, exercise (cycling, walking, gardening), art, conversation. Overall, though, writing for me isn’t a particularly fluid process; it feels like a continual struggle, from stall to start to stall to start again, giving it a spasmodic feel. Related to this, I return frequently to Louise Gluck’s Proofs & Theories: Essays on Poetry, particularly her observation that when “the aim of the work is spiritual insight, it seems absurd to expect fluency.”

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of lake. I live near the ocean, but that is not a home smell. Also the fragrance of horse manure from the Bengal Lancers stables close to downtown Halifax.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature, music, science, visual art, conversations—beauty in some form, though that beauty could be perceived by others as ugly. Wherever this influence comes from, it is often a surprise: as a visit to an art gallery will show, you don’t know which painting will arrest you and why—it may not be the famous vase of sunflowers by van Gogh, but a more obscure painting, and the reason it surprises and provokes curiosity is elusive.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Mystic writers throughout the centuries (Augustine, Evagrius Ponticus, Marguerite Porete, Meister Eckhart, Simone Weil, Thomas Merton….), Adam Phillips, Stanley Cavell, Talal Asad, Thomas Bernhard (Gathering Evidence), Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Anne Carson, Kathleen Roberts Skerrett, Rowan Williams, Catherine Keller, John D. Caputo, Iris Murdoch, W. G. Sebald, J. M. Coetzee, Hannah Arendt, Alice Munro, Steven Heighton, Carole Langille, Sue Goyette, Jan Zwicky, Maggie Nelson, Jack Gilbert, Don McKay, Brian Bartlett, Ross Leckie, Sue Sinclair, Don Domanski, Jorie Graham, Rainer Maria Rilke, John Barton, Anne Compton….

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Travel from Nova Scotia to British Columbia by train. Odd people often take trains, as I discovered in 1999 on the Southwest Chief travelling between Chicago and Albuquerque. I was a doctoral student then, and did the twenty-nine-hour journey sitting upright (in my seat or the dining car), reading the first two volumes of Virginia Woolf’s diary. With its entries of varying lengths, the diary was perfectly suited to long pauses of looking out the window or talking with strangers who were not in a hurry to get to where they were going.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Rancher, psychoanalyst? Though I like the diversity of my present occupations.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have always felt the necessity to write, though for a great many years I also felt immense internal constraints against the threat and pleasure of being seen (a struggle that continues).

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (found in one of those free mini-libraries on posts driven into people’s lawns). Mesmerizing idiosyncratic characters, intriguing and elusive lines between fiction and non-fiction, runic physicality of trauma, marvelous use of black and white images.

Film: Francis Ha. In an interview with Sarah Polley, Greta Gerwig (co-writer, actor in the film) talks about the style of dance in the film, based on a “release technique” of learning how to fall—letting the joints and skeleton fall, the knees to slip out, and the whole body follows; using the momentum of the fall to get back up again. It’s dance performance that looks like random seeming movements, or mistakes. Gerwig’s character Francis inhabits this practiced falling in some cringe-worthy conversations and her dance performances, which captured my imagination because of my fear of falling, my fear of making mistakes (in life and art). Recently I’ve become aware of how a physical fall feels different to me now, something I attribute to the physical meditation of a yoga practice. A few weeks ago, walking home from the grocery store, I fell to my hands and one knee; my body, spring-like, bounced back up, an amazing visceral feeling—but I also felt ashamed of being seen falling, and walked on quickly without pausing to see what caused my fall. I hope my mind and spirit is gradually getting more attuned to that fleshly spring.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A Book of Psalms. A project as yet undefined, praise and lament for the earth. A few years ago, while cycling, I stopped at my usual rest spot, Cranberry Lake. In a brief conversation, a man sitting on the rock that edges the lake, asked me what I do, and in response to my reply, “I’m a theologian,” said, “how presumptuous.” This would be an appropriate response to my imagined project.

February 4, 2022

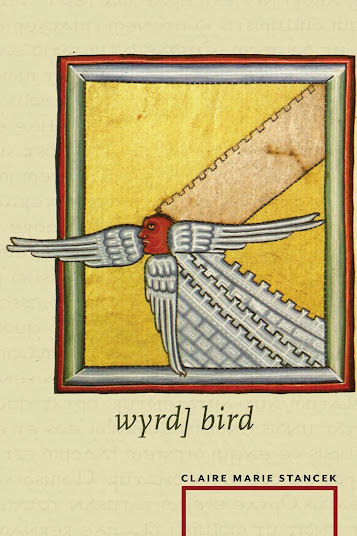

Claire Marie Stancek, wyrd] bird

Sometimes the visionary epiphany is a simple one: wind.

When to call & when not to call. Against absence we measure our absence. Like a sudden seizing, cold air rushes the highrise, seals some doors at its random whim, building’s breath, slapping hatches open & closed like gills. Even that blind god, the elevator, pauses, hovers mid-shaft under gustheavy force, a force present though unseen.

In my dream we ate ashes. Where are you? Your voice on the phone but the sidewalk charges ahead. The wail in the trees.

Your voice on the phone and in broken glass my image reflected, broken, a piece of neck, a partial ear, a snagged snakelike earphone wire.

O my love, what have we made of what we made.

Still working through my stack of Omnidawn titles from the past two years, I’m just now getting to the third full-length collection from Canadian-born American poet and editor Claire Marie Stancek, her

wyrd] bird

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2020). Originally from outside Toronto, Ontario, Stancek lives in Berkeley, California, and is the author of the collections

Mouths

(Noemi Press, 2017) and

Oil Spell

(Omnidawn, 2018), co-editor (with Daniel Benjamin) of

Active Aesthetics: An Anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry

(Tuumba Press/Giramondo 2016), and, with Lyn Hejinian and Jane Gregory, is the co-founder and co-editor of the chapbook press Nion Editions. Deceptively offering a table of contents that is, one quickly realizes, a sequence of first lines, wyrd] bird sits as a collection of untitled, self-contained accumulations that form a book-length suite, akin to a lyric essay, echoing works by poets such as American poets Cole Swensen and Pattie McCarthy, or Ontario poet Phil Hall. There is a way in which she utilizes the lyric mode and lyric sentence as a space for critical exploration, writing through and around Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098 – 1179), “also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, [who] was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner during the High Middle Ages. She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern history. She has been considered by many in Europe to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.” (Wikipedia). wyrd] bird is a meditation on attending and attention, one that includes prayer, visions and nature, utilizing Hildegard of Bingen as a kind of jumping-off point into further inquiry through an extended period of grief.

Still working through my stack of Omnidawn titles from the past two years, I’m just now getting to the third full-length collection from Canadian-born American poet and editor Claire Marie Stancek, her

wyrd] bird

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2020). Originally from outside Toronto, Ontario, Stancek lives in Berkeley, California, and is the author of the collections

Mouths

(Noemi Press, 2017) and

Oil Spell

(Omnidawn, 2018), co-editor (with Daniel Benjamin) of

Active Aesthetics: An Anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry

(Tuumba Press/Giramondo 2016), and, with Lyn Hejinian and Jane Gregory, is the co-founder and co-editor of the chapbook press Nion Editions. Deceptively offering a table of contents that is, one quickly realizes, a sequence of first lines, wyrd] bird sits as a collection of untitled, self-contained accumulations that form a book-length suite, akin to a lyric essay, echoing works by poets such as American poets Cole Swensen and Pattie McCarthy, or Ontario poet Phil Hall. There is a way in which she utilizes the lyric mode and lyric sentence as a space for critical exploration, writing through and around Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098 – 1179), “also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, [who] was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner during the High Middle Ages. She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern history. She has been considered by many in Europe to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.” (Wikipedia). wyrd] bird is a meditation on attending and attention, one that includes prayer, visions and nature, utilizing Hildegard of Bingen as a kind of jumping-off point into further inquiry through an extended period of grief. Coleridge, bewildered by his baby’s cries, rushed the infant Hartley out into nightingale night, to where the moon calmed the child, as it had calmed Coleridge himself in another poem, like friendship, and friendship’s strength, imparting an abstracted absorption from which, childlike, he rose, and found himself in prayer.

O green vigor of the night air, dense with heavenly bodies made of cold and light.

This really is a stunning collection, one that works a unique complexity and depth through such dark, amid the searching, stretching and attending. In an interview conducted by Valentine Conaty, posted on November 10, 2021 at Full Stop, Stancek speaks of some of the prompt of the poems that made up the collection, and of writing through Hildegard of Bingen’s visions: “The experience of embodiment is central to wyrd] bird not just in what the book describes but also in how it speaks and thinks. I wrote this book during a time of intense personal suffering, when my individual experience seemed inextricable from larger societal violences. And I kept a notebook during this time, carried it everywhere, and even slept with it (the book begins, ‘I slept with my book open, woke into strange thoughts pen in hand’).” Stancek continues:

My pain took the form of receptivity and I wrote the overlapping thoughts, synaptic conjunctions, coincidences and convergences that felt in my heart and lungs, in my body-as-brain. The body’s intelligence is not less than that of the mind, but is immersive, multivalent, and often exceeds the possibilities of language. And notebook writing lends itself to the fleeting and the temporary, the unfinished.

February 3, 2022

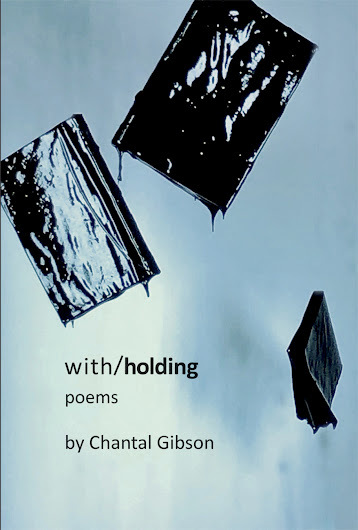

Chantal Gibson, with/holding: poems

I come to you withholding. Let’s

not loiter in the truth. The evil is

already written, our files forever

corrupted. No free antivirus. No

algorithmic way out. The content

is sponsored, baked with our DNA,

the machines busy with the mind-

less work of reproduction. There’s

no Science in remembering, no Art

in the daily curation of our suffering,

no wonder in their wretchedness,

no limit to the limits of their artificial

intelligence. That Error message—

just a distraction. The evil is set on

a loop. Our horror lies not in what

w consume. It’s in the grinning

tyranny of copy n paste, the geno-

ciding rate we feed on our own

afflictions. It’s in the dead-ending

way we spend our pain per diem. (“Terms n Conditions”)

Award-winning west coast poet, artist and educator Chantal Gibson’s second trade poetry title, after

How She Read

(Qualicum Beach BC: Caitlin Press, 2019) [see my 2020 interview with her here], is

with/holding: poems

(Caitlin Press, 2021). Gibson’s engagement with shaping language is clearly related to her experience as a visual artist, allowing visual elements and aesthetics into the work that feel very different in texture and tone than the directions that emerge out of concrete and visual poetries. As Hannah McGregor offers as part of her blurb for the collection, “with/holding embeds the reader in the flattening aesthetics of the internet, where every expression of Black life is always already a meme waiting to be reprinted on a yoga mat.” These are poems that unpack and respond to violence, racism, culture and history, and the complexicities of depiction and representation. Gibson utilizes the structures and dehumanizing trickery of online advertising to explore how Blackness is depicted, dismissed and flattened in media, utilizing the language and structures of online advertising copy to social media. Gibson’s work examines a distinct narrative of corrosive speech built out of advertising and corporate language, one that quickly collapses under its own altered meanings. “A white-collared Uncle Ben will never look like / Obama,” she writes, early on in the collection, “and light Aunt Jemima still looks like Auntie-Blackness. It’s hard, letting / go. Unless it’s fixed to your head, a brown face is still blackface, no matter how / you render it.” Through a compelling study shaped and formed in part through collage, she writes of outliers and borders, writing of what has been erased, bordered, boundaries and blacked out. “it’s the way she bites the heads off first,” she writes, to open “Phobogensis,” “it’s the way she shows her teeth // it’s the way she holds up each head // less body like a tiny black trophy be // tween her pinchy-pink finger tips [.]” She includes a long sequence of white text in black boxes, reframing a design shape of slogans. There is a sing-song quality to her experiments and alterations, one that engages heavily with a play of sound and visual propelled by intellectual rigor.

Award-winning west coast poet, artist and educator Chantal Gibson’s second trade poetry title, after

How She Read

(Qualicum Beach BC: Caitlin Press, 2019) [see my 2020 interview with her here], is

with/holding: poems

(Caitlin Press, 2021). Gibson’s engagement with shaping language is clearly related to her experience as a visual artist, allowing visual elements and aesthetics into the work that feel very different in texture and tone than the directions that emerge out of concrete and visual poetries. As Hannah McGregor offers as part of her blurb for the collection, “with/holding embeds the reader in the flattening aesthetics of the internet, where every expression of Black life is always already a meme waiting to be reprinted on a yoga mat.” These are poems that unpack and respond to violence, racism, culture and history, and the complexicities of depiction and representation. Gibson utilizes the structures and dehumanizing trickery of online advertising to explore how Blackness is depicted, dismissed and flattened in media, utilizing the language and structures of online advertising copy to social media. Gibson’s work examines a distinct narrative of corrosive speech built out of advertising and corporate language, one that quickly collapses under its own altered meanings. “A white-collared Uncle Ben will never look like / Obama,” she writes, early on in the collection, “and light Aunt Jemima still looks like Auntie-Blackness. It’s hard, letting / go. Unless it’s fixed to your head, a brown face is still blackface, no matter how / you render it.” Through a compelling study shaped and formed in part through collage, she writes of outliers and borders, writing of what has been erased, bordered, boundaries and blacked out. “it’s the way she bites the heads off first,” she writes, to open “Phobogensis,” “it’s the way she shows her teeth // it’s the way she holds up each head // less body like a tiny black trophy be // tween her pinchy-pink finger tips [.]” She includes a long sequence of white text in black boxes, reframing a design shape of slogans. There is a sing-song quality to her experiments and alterations, one that engages heavily with a play of sound and visual propelled by intellectual rigor. Elevate the content. Make a donation. Promote diversity from within – Offer everyone a seat at the table. Try making new BLACK FRIENDS. Find an athlete, an actor, a celebrity scholar, an influencer, a reformed gangster rapper.

It’s time for change and authenticity comes at a price.

Don’t panic. Spin it.

Call it Reparations.

Call it Rap!arations.

Just keep your eye on the bottom line.

February 2, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jean Day

Jean Day

is a poet and editor. Her most recent book is

Late Human

(UDP, 2021). She lives in Berkeley, where she has just retired from several decades as managing editor of Representations and continues to do advocacy work for members of the University Professional and Technical Employees Union.

Jean Day

is a poet and editor. Her most recent book is

Late Human

(UDP, 2021). She lives in Berkeley, where she has just retired from several decades as managing editor of Representations and continues to do advocacy work for members of the University Professional and Technical Employees Union. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The first book (Linear C, a chapbook) offered the great pleasure of being taken somewhat seriously by some of the writers I cared about.

I’d like to say that recent work is freer from what I thought the terms of rigor were in 1980; it’s certainly much less concerned with the notion of an avant-garde. While newer poems seem to me more considered, they aren’t, I hope, more conservative. Thematically, I think my touchstones have remained pretty consistent: who has the power to say what they say, and why is it so revealing—and often funny/tragic?

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve always been interested in multivalent, cryptic, difficult, and eccentric meaning systems, which, with some obvious exceptions, seem much more prevalent in poetry than in prose.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It varies. Sometimes an almost fully formed idea strikes me (I want to write a book of odes; I want to wring every last change on my own name); sometimes I write and write until I perceive a thread. Often individual works or series come out of my notebooks, although “copious notes” is much too ponderous to describe what’s in them (all sorts of detritus). The specific content—words—of a first draft often change, but the sound of it is generally what gives it an initial shape, a framework from which to move forward, and I usually stick with that.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think I just answered that; it happens both ways.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings, but not because I make any claims for a performative element in the work; I just think my own voice is probably the best way to hear the poems, or for me to hear the poems. I love hearing people laugh, and I love socializing afterward.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

It would be silly to say I don’thave theoretical concerns when I’m writing; I’m just never clear (and actually somewhat uninterested in) what they are, or if they’re coherent. I don’t think I’m trying to answer any particular or persistent questions except the most basic ones that any human confronts: who am I, what am I, who are you, and why? Why is there suffering and what can I do about it? How am I going to deal with death? And so on. I don’t think of my writing as solving these or any other problems, much as I would be happy if it did. For the most part, I think, it’sunscripted, or unforetold—just part of the ongoing human story. I think we all know what the current questions are, at least on the planetary, political, and social scales, and I think all but the very tone-deaf among us are writing toward those questions in one way or another—some straight, some slant.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I’d like to think “the writer” can be an agitator, a thorn—but I’m not sure “the larger culture” recognizes her (or the poet, at least) as having even that much power, or any legitimate role. We’re just people doing our jobs.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

To the extent that I’ve experienced a real “outside” editor (one who asks important questions about the work), the interaction has been so rewarding. Having to justify one’s choices can be fruitful—even salvific.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Never take no cutoffs, and hurry along as fast as you can.” –Virginia Reed, of the Donner Party. Hers was advice given to the emigrants who might follow her. This may be anti-advice in the realm of poetry, but it cuts to the quick.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Translation of poetry is on a continuum with writing it, even if, in a sense, it’s also unwriting (taking things apart). Having “translated” only a small number of poems, with only the most rudimentary knowledge of the language of the original (Russian), I can have little to add to what real translators think and do. Even the occasion of my first involvement with translation was a bit of happenstance: In 1989, Lyn Hejinian and Arkadii Dragomoshchenko paired five American poets, of whom I was one, with five Russian poets for a sort of experiment in translation. This was during Perestroika, so before the fall of the USSR, and the enthusiasm for communication across what was left of the iron curtain was high. The idea was to do it transpersonally, not just transtextually. So the ten of us met in Stockholm and Helsinki, and then Leningrad, to talk face to face and, with that dialogue as a kind of substrate, to read and translate each other’s work. “Translation,” on these terms, involved a great deal of talking, eating, drinking, smoking, reading, walking around, guessing, second guessing—being—all activities (except smoking) that figure into my own process.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Sadly, unlike HD, Proust, and some others, I’ve never had the leisure to write from bed. Daytime (while working a full-time job) seems to have required all my practical faculties, so I’ve tended to write, when possible, for an hour or so before or after dinner and here and there on weekends. Reading, which has always been a big part of my practice, I can do any time a few minutes make themselves available.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Almost any change of direction will do: carving wood, drawing, talking to neighbors (or friends or strangers)—even willful nonendeavor sometimes helps, but I’m usually too goal-oriented for that.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Seaweed.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above. Definitely every instance of culture I consume, plus human conversation—the sound of people talking—really anything that crosses my perceptual bow. Lately I’ve been interested in what John Rapko calls “proto-art”—what you might think of as “found” objects in nature (or culture), naïve works, things that were once thought “primitive” or were at one time thought important, now not. The attraction is the lack of finish or determined meaning—the fact that meaning can occur unintentionally or quasi-intentionally. That there can be an unadulterated, unfiltered perceptual reward in something that didn’t mean to be art. Perhaps a weird thing for someone who makes art to say.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Things come and go. (And so many! Any list I could give would necessarily be hopelessly partial. For my own work, at one time or another:

Some of the classic works of anthropology, especially Malinowski

Research on the development of language and early childhood

The literatures of enthusiasm, hot-headedness--religious and otherwise

Enlightenment quackery

Early American journals and narratives from all sides of “contact”

The Gettysburg Address

Balzac, Flaubert, Stendhal, Chekhov, Dostoevsky …

The anonymous 18thC British work Low Life, or, How the Other Half …

Amanda Goldstein’s Sweet Science, which turned me on to Shelley’s “Triumph of Life”

Narratives of “discovery,” ships’ logs, expedition diaries

Old science; plus naturalists, scientists, and observers of any era; field guides

Geometry textbooks

Outsiders in any genre

Anything/everything on odes, especially Ilya Kutik’s PhD dissertation

T.J. Clark’s The Sight of Death

Christa Wolf’s One Day a Year, 1960-2000

Poets and poetries too numerous to mention

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Travel by train across Canada (actually anywhere I haven’t already been by train), see Walter de Maria’s Lighting Fields, beat my partner at Scrabble.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Being a writer has never been an income source, nor has it ever taken up the majority of my time, so in that sense it’s never been an “occupation.” The only trajectories I considered even half seriously before understanding that writing would be the main thing were ballet (a dream dead by the time I got glasses in 6thgrade) and visual art. For a brief time, when I first moved to SF, I thought learning how to print, either letterpress or offset, might lead to some career options, but the former was absolutely nonremunerative, and the latter, I realized, would have bored me as a real job. So I drifted into small-press bookselling (SPD) and then academic editing. In hindsight, fieldwork in botany sounds … romantic. But I’m not very good with detail.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

At a summer camp for teens in the arts, where I was doing mainly drawing, I saw that it was the “writers” who were having verbal thoughts and articulating them. I’m not sure why, but that seemed far more interesting to me than what the art people were doing, so I switched.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Olga Togarczyk’s House of Day, House of Night, is a wonderful novel; I read all of her novels in English during the lockdown. They’re all great in different ways, but House of Day… has a miraculously quiet touch while getting to the core of something—lived life? Mushrooms? The only “great” movies I’ve seen at all recently are some of the filmic works of the South African artist William Kentridge, shown online through his gallery in 2020. The collaborative film by Abbas Kiarostami and Victor Erice, Correspondences (ten filmed “letters” between the two filmmakers), made in 2016 but seen in the last year, also made a big impression.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Finding a publisher for The Night Before the Day on Which, a 3-part project finished more than a year ago. It’s hard to talk about work that’s actually in progress (not finished), but I can say that I’m still dithering around with another multi-part project whose overall, but very provisional (because entirely unoriginal) title is The Elements. So far, it’s “about” foundations, morphologies, ur-circumstances, branching structures, seaweed. The first section, “Adamant” (also provisional), is finished, but the sheltering in place threw my psychic and work lives, my schedule, my brain function for a loop … so, however I go forward, I will have to deal with that break somehow.

February 1, 2022

Lawrence Giffin, Untitled, 2004

October 12 or 15, the twelfth

surely, certainly 2016 that I know,

your mother and I took the train

uptown to see the Agnes Martin

retrospective at the Guggenheim,

and still a year and change before your birth,

we hadn’t thought of naming you Agnes

and wouldn’t until your mother was

well into her pregnancy with you.

Shakespeare’s wife Ann was born

Agnes Hathaway, back when

people thought Agnes was just

a version of Anna, which is not,

like Agnes, from the Greek but comes instead

from the Hebrew meaning “grace.”

And so begins the latest poetry title by American poet and editor Lawrence Giffin, the extended poem Untitled, 2004 (New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020). Untitled, 2004 follows on the heels of his array of previous books and chapbooks, including Get the Fuck Back Into That Burning Plane(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009), Sorites (Tea Party Republicans Press, 2011), Ex Tempore (Troll Thread, 2011), (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012), Just Kids (with Lauren Spohrer; Agnes Fox Press, 2012), Ad Pedem Litterae, 3 vols. (Troll Thread, 2012), Quod Vide (Troll Thread, 2014), Non Facit Saltus (Troll Thread, 2014), White Future(orworse, 2014) and Plato’s Closet (Roof Books, 2016).

“The trouble with beginnings is / they never take place quite at the / beginning.” he writes, close to the beginning of the collection (but not actually at the beginning). There is an ongoingness to this piece that is quite interesting. Giffin composes a long poem that moves through accumulation of section upon section, layering an epistolary meditation directed at his young daughter while folding in lengthy critiques and observations on the work and life of Saskatchewan-born American painter Agnes Martin (1912-2004), as well as a wealth of elements of history, theory and memoir. There is a sense of the epic throughout Giffin’s poem, as well as something deeply intimate and personal, sketched as a diary for the young Agnes, in a book titled after an artwork by her infamous and late namesake.

I wouldn’t say you were named for

Martin, only that the name Agnes

served to mark the promise

of those early days, when

everything that had gone before

willy-nil toward an indefinite future

was roughly abridged into

a prefatory note hastily

scribbled in anticipation

of what was sure to come after.

Now we live in the relief

of waking from the nightmare where

you are yet to be born, which itself

was a nightmare, medically induced,

expectant joy debrided

into merciful deliverance.

Survival was the strait gate

through which you crammed

the contents of our world

compressed into an age-old name.

“Boredom is the desire for desire, / desire at its purest and so also, / strangely, at its most empty.” Throughout Untitled, 2004, Giffin writes on boredom, error, desire, perception, reflection and observation, folding in other elements, artworks, conversations and thoughts along the way, from St. Augustine on craft, a wealth of observations on Agnes Martin and her work, to his thoughts on “an enormous outdoor maze / by Patrick Dougherty [.]” “I walk through museums, Agnes,” he writes, “like I walk through the mall: / purposeless loafing, letting the / fantasies on offer move in / and out of my consciousness / like curtains in an open window.” There is also a particular kind of pivot he discusses, about a third of the way through the poem, citing Agnes Martin’s habit of destroying the paintings of hers that she considered imperfect or flawed in some way, not wishing to allow an artwork with a “mistake” to exist; the pivot, of course, being she did this with all of the artworks she created that she considered imperfect, but for the singular piece Untitled, 2004, […] functioning thus / as the style’s own self- / consciousness, as the fulcrum / on which her entire career / pivots back on itself. It’s / as if her seven-year break from / painting and the accompanying / break in her style is referenced / in this splotch, which becomes / a sign of that difference between / the tension of the early works / and the harmony of the later ones.” Through this, I’m uncertain Giffin’s consideration of this, if he’s attuned to this particular artwork because of its perceived flaw and is thusly connecting his own pivot-point, composing a poem on attempting perfection and the further-beauty and further-possibility of imperfection through this particular epistolary-meditation.

“Boredom is the desire for desire, / desire at its purest and so also, / strangely, at its most empty.” Throughout Untitled, 2004, Giffin writes on boredom, error, desire, perception, reflection and observation, folding in other elements, artworks, conversations and thoughts along the way, from St. Augustine on craft, a wealth of observations on Agnes Martin and her work, to his thoughts on “an enormous outdoor maze / by Patrick Dougherty [.]” “I walk through museums, Agnes,” he writes, “like I walk through the mall: / purposeless loafing, letting the / fantasies on offer move in / and out of my consciousness / like curtains in an open window.” There is also a particular kind of pivot he discusses, about a third of the way through the poem, citing Agnes Martin’s habit of destroying the paintings of hers that she considered imperfect or flawed in some way, not wishing to allow an artwork with a “mistake” to exist; the pivot, of course, being she did this with all of the artworks she created that she considered imperfect, but for the singular piece Untitled, 2004, […] functioning thus / as the style’s own self- / consciousness, as the fulcrum / on which her entire career / pivots back on itself. It’s / as if her seven-year break from / painting and the accompanying / break in her style is referenced / in this splotch, which becomes / a sign of that difference between / the tension of the early works / and the harmony of the later ones.” Through this, I’m uncertain Giffin’s consideration of this, if he’s attuned to this particular artwork because of its perceived flaw and is thusly connecting his own pivot-point, composing a poem on attempting perfection and the further-beauty and further-possibility of imperfection through this particular epistolary-meditation. Giffin writes on knowing and unknowing, and the benefits of being open to both, including the arena of falling full into what might otherwise be impossible. “Agnes, I know almost nothing,” he writes, towards the end, “and it has taken me nearly / forty years to learn how dumb / I’ve always been.” He writes of first encountering the woman who would become Agnes’ mother, and the first steps of their courtship, a story that includes wandering a gallery and seeing work by Agnes Martin. “The weekend / your mother and I met, she lost / her fingertip cutting kale, / and we spent the better part of / the evening in the ER, surrounded by / bloodied Chux, with curling wisps / of lunar caustic floating up / from the wounded nail bed. / Her pointer finger even now, / years later, remains disfigured / and, no longer round, / comes to a point instead.” There is such a wonderful openness to this book-length epistolary poem, one composed with the care and attention of a new parent and a deeply considered aesthetic, one that seeks to embrace a kind of change, however uncertain those changes might be.

January 31, 2022

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Heather Campbell on Latitude46

Heather Campbell has spent over 30 years in communications and freelance writing, specializing in issues relevant to Northern Ontario communities. A graduate of York University (BA Sociology ’92), she has combined her education, experience and ‘need to initiate’ by starting a local chapter of the Professional Writers Association of Canada and the Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival. She has held the position of Chair for LitDistCo, a small book distribution collective of literary book publishers, since February 2020 and she is a Board member of the Ontario Book Publishers Organization.

Heather Campbell has spent over 30 years in communications and freelance writing, specializing in issues relevant to Northern Ontario communities. A graduate of York University (BA Sociology ’92), she has combined her education, experience and ‘need to initiate’ by starting a local chapter of the Professional Writers Association of Canada and the Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival. She has held the position of Chair for LitDistCo, a small book distribution collective of literary book publishers, since February 2020 and she is a Board member of the Ontario Book Publishers Organization. Latitude 46 is a member of Literary Press Group, Ontario Book Publishers Organization, Association of Canadian Publishers and eBOUND. We receive funding from Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council of the Arts, Ontario Media Development Corporation and Canada Book Fund.

1.When did Latitude46 first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

We started on March 31, 2015 and published our first anthology, Along the 46th: Short Fictionin November 2015.

Latitude 46 was started by myself and Laura Stradiotto, a fellow freelance journalist, who agreed that we wanted to ensure Northern Ontario continued to have a publishing house after Scrivener Press closed. Our mandate to publish Northern Ontario authors and stories has not changed. We receive approximately 50-60 submissions each year (increasing every year), plus I seek out diverse authors.

Laura left to pursue other interests in 2019 but remains supportive of the press. Our consulting editor Mitchell Gauvin now Dr. Mitchell Gauvin (English), also a published author (Vandal Confessions) continues to work with us.

I initially approached the owner of Scrivener Press to purchase from him, however, his response was “the learning curve is too much” which I took as patriarchal at the time. It has been an enormous learning curve indeed but certainly achievable. I have had many mentors including Leigh Nash, Karl Seigler, Hazel and Jay Millar and many professional development opportunities. I am never not learning about different aspects of publishing. Currently I am diving into exporting and foreign rights.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?

I spent the first 30 years of my life in Toronto before moving to Sudbury. When I was 19 years old I loved reading and had a dream of becoming a novelist. After finishing high school I met with a counsellor at Centennial College to explore the Book Design and Production program, however, I also was interested in university and was exploring social work. I decided on sociology with a minor in English at York University. The next 30 years I spent my career in communications and writing (freelance journalism). At 50, my kids were gone to university and Scrivener Press was closing. I had some experience ghostwriting and self-publishing for others so I understood a bit about making books. Before I started the press though, I met with ACP Executive Director, Denise Truax of Prise de parole (Francophone publisher in Sudbury) and Laurence Steven, retiring publisher of Scrivener Press to get their perspective on starting a brand new press. Based on what we learned, we then decided to climb this mountain.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

Small press, Indie publishing, is here to ensure that all voices are heard, particularly those who are overlooked because they don’t meet the criteria for selling enough copies to support a corporation. Indie publishing spends a great deal of time nurturing emerging authors, or at least I do! I am so impressed by the books being published by my fellow indie presses. Books that have the power to inform, inspire and tell the truth. We are focused on storytelling by Canadians for the whole world to read.

As a small press in Northern Ontario, where many authors are distanced from the “publishing industry”, I invest a great deal of time to answering questions, encourage young authors, and raising the bar on quality of writing. I also started Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival in 2013 and we are presenting our 9thedition this year. I have such a passion for writing and books and wanting others to have access to the industry. I always bring professionals from the industry, award winning authors as well as local authors to the festival.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is? We are a regional press. It limits us in some ways, but at the same time creates a clear focus. We are the only English language trade publisher in Northern Ontario. For Ontario in particular, Northern Ontario is often overlooked. However, the culture and stories that reside here are connected to the land and unique experiences. I am not sure if other small presses find this but having a publisher who is accessible means I get a lot of people contacting me, approaching me at events to ask questions about publishing or pitch me directly. I am not able to hide in an office tower in a big city, or away from view in a rural location. I feel a certain responsibility, as a community member, to help in some way whether directing to a more appropriate publisher ie children’s, more writing assistance or even self-publishing.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new books out into the world?

Interesting question as the world around us is “pivoting”. If this is a distribution question, lots could be done. We need to have the return of local independent bookstores. I have very recently been getting involved in the conversation between booksellers and publishers and so much can be done in this relationship that would move books better. My experience with the festival has shown me that readers love meeting and hearing from writers. They immediately go buy the books. Book clubs and video chats move books. In terms of marketing to move books, we have relied on social media and the digital environment but we are finding out that we have so little control over who actually sees those messages. I am also behind advocating for more Canadian books in Canadian schools.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

The most editing I do as the publisher is a light touch to start and then hand over to an editor who can dig deep. We hire editors based on the book and author. For example, we just published Aurore Gatwenzi’s debut poetry collection, Gold Pours this past fall and she really wanted to work with Britta Badour. We had Britta at Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival so we hired her to work with Aurore. I love that! Not only great editing but great mentorship too. Mitchell Gauvin will work on the majority and he is such a thoughtful and thorough editor. I also meet with each author I sign prior to signing and we have the discussion about their approach to editing. I need to see that they are keen and willing for a good edit.

7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

Our books are distributed by LitDistCo and I have held the role of Chair for LitDistCo since February 2020. I also do a good number of sales from our online shop.

I have been keeping our print runs low since initially printing 500 – 1,000 on early books only to have them sitting in my shed :<( We have been printing with Rapido Books and they have a program where each print run on a single title adjusts unit price to reflect the total amount run. (Hope that makes sense). I will typically run 350-400 to start, and go up from there depending on demand.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

As mentioned before we hire editors based on author and book. I am currently working with Sarah Jarvis for our first YA Novel. I have hired Nathan Adler as a sensitivity reader. I hire local proofreaders.

We started with hiring a designer but I eventually learned to design because it was frustrating to wait for them to get to a small edit or rushing through a design.

I like hiring by book. I think we do well for the author and the story when we have an interested team working on the book. I have purchased local art for covers as well.

The only drawback I have encountered is timing on design work. There is an immense amount of administrative work to publishing and I find myself leaving the layout or design to the last minute.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

When I initially started the press and read through submissions it made me want to write again. Over time, I am much too busy to even think about writing! I just read Linda Leith’s memoir and welcomed her to Sudbury for the Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival, we have some similarities in establishing a literary festival and publishing house. I find her writing beautiful and maybe someday I will write a beautiful memoir too.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

I won’t publish my own writing at this point. For me, I don’t have time but I would likely do what Linda Leith did and find another publisher. I do believe there needs to be some objectivity to creating and promoting your work. If I published under Latitude 46, it would feel more like self-publishing.

11– How do you see Latitude46 evolving?

My dream for Latitude 46 is to have a long life – another 20 years and hopefully sell so it can live on after me. I hope we uncover some talented and impactful authors who provoke conversations. We are working on exporting more books into the US, but I also hope we can negotiate more foreign translation rights for our authors and attend book fairs around the world.

It has been an immense amount of time and work to reach where we are now. I decided in the beginning that we would make our mistakes in the early years but hone our craft of publishing in subsequent years. We are honing the publishing process now in order to reach that dream.

Building a committed and solid team is also important for longevity.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

The fact that we are still here after 2020 is such an accomplishment! That was a tough year. We were in operation for only 5 years when the pandemic hit.

I sometimes feel the industry wants Latitude 46 to prove itself, will it last? will they publish “literary” work? It has been a tough slog to get media attention on our books yet The Miramichi Reader has awarded recognition to our books a few times and we have received Northern Ontario Literary Awards. We published Danielle Daniel’s memoir and she eventually was picked up by Harper Collins. We have supported Rod Carley (A Matter of Willand Kinmount) who was longlisted for the Stephen Leacock Award. We have released 31 titles in 7 years and on a shoestring budget. I have yet to pay myself as well.

I have also given back to the industry by Chairing LitDistCo through challenging times and sitting on the Ontario Book Publishers Organization board.

My biggest frustration is that I am doing all the right things to build a publishing house from the ground up yet struggle for my authors to get any national attention. I am so grateful to be working with Nathaniel Moore who has been able to move some media to consider what we are doing in Northern Ontario.

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out? I am so grateful for making a connection with Jay and Hazel Millar in our second year of opening the business and watched them handle their publishing house name change. Was so impressed with their handling of the situation. Jay had said to me once, “Every week we make a toast we are still here this week!”. It let me know that our experiences were as they should be for starting out. We may never reach “midsize house” but I do watch House of Anansi and ECW. David Caron has always been encouraging with me and I love their innovative and progressive approach to business. What I love about publishing is how supportive most publishers are to each other.

14– How does Latitude46 work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Latitude46 in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

As mentioned earlier I am the founder and Festival Director for Wordstock Sudbury Literary Festival, and in both of these roles I strive to influence the literary arts community to work collaboratively to support and encourage writers to live and work in Northern Ontario.

I have not had the opportunity to connect much with journals but have a few of my favourites such as subTerrain.

I attend all the ACP, LPG and OBPO meetings to connect with other presses and contribute to conversations about industry challenges from funding, supply chain and marketing. I love that kind of work where we are moving the industry forward yet always keeping our values intact. To me it’s not just about the physical book but the voices, ideas and intellectual contributions from so many voices that we are ensuring have airtime.

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?

Prior to Covid we held in-person launches to celebrate. In 2017 when we launched our 5 fall books, we welcomed 200 people to an in-person event. I believe that public readings are vital to the scope of reading and writing. Having a conversation about what we are reading is important to readers, and writers. It also makes an enormous difference to have author signings. We do not have a local independent bookseller in Sudbury, we do have a Chapters store though.

My perk as festival director is when I have programmed a diverse lineup of authors and they engage in a thoughtful conversation both among themselves and with contributions from the audience. I love watching the audience come out and give me feedback on the session with beaming faces and exclamations of “that blew my mind”, that is why I do this!

The festival has also held a regular Poetry Slam (I am fond of this genre) and have found a few poets through this community event. I do attend readings and Open Mics to be aware of what’s happening with local authors as well.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

I like to think we have a good presence online – website, social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn), YouTube and news items – we also have an online bookshop which are all accessible online.

17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

We have always had an open submission. Our submission guidelines can be found on our website. I would really love to receive more diverse voices stepping forward. Our mandate is to publish Northern Ontario authors and stories about Northern Ontario. We publish literary fiction, non fiction, poetry and YA.

We do not publish children’s literature, fantasy, genre fiction. I am drawn to smart, provocative and unique stories.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

Our Fall 2021 titles are two of my favourite. Adam Mardero’s Uncommon Sense: An Autistic Journey. Adam shares how he navigated the darkest dungeons and brightest triumphs of life on the Autistic Spectrum and through it all discovers the ultimate treasure: what it really means to find yourself and live life on your own terms. He has an incredibly generous personality. I met Adam in 2015 at a community event. We were standing beside each other and he introduced himself, not knowing I was a publisher. Through our conversation he shared that he was thinking of writing about his experience with Asperger’s. We encouraged and guided Adam for the next several years until he had a manuscript ready for publication. I am thrilled with the end result.

Aurore Gatwenzi is a young Black poet who is born and raised in Sudbury by Burundi immigrants. Her debut poetry collection is called Gold Pours. She talks about God, identity, heartbreak and passion. She has an honest approach to writing that exposes readers to humility, surrender and lessons learned from courageous acts of vulnerability. I met Aurore when she performed her poetry at a festival poetry slam. She is also an aspiring actor.

We are publishing another emerging Northern Ontario poet, Noelle Schmidt with her debut collection Claimings and Other Wild Things in April 2022. She is a young queer, non-binary poet and sheds light on growing up in Northern Ontario but also about her German heritage. She has some impressive blurbs. Noelle approached us in 2018 to complete her university placement with us and later submitted her manuscript.

These three emerging writers with diverse perspectives shed light on growing up and finding their authentic selves despite the distance from a large urban centre and limited diversity.

January 30, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Aimee Wall

Aimee Wall

[photo credit: Richmond Lam], a Newfoundland native, is a writer and translator. Her essays, short fiction and criticism have appeared in numerous publications, including Maisonneuve, Matrix Magazine, the Montreal Review of Books, and Lemon Hound. Wall’s translations include Vickie Gendreau’s novels Testament (2016) and

Drama Queens

(2019), and Sports and Pastimes by Jean-Philippe Baril Guérard (2017). She lives in Montreal.

We,Jane

is her first novel.

Aimee Wall

[photo credit: Richmond Lam], a Newfoundland native, is a writer and translator. Her essays, short fiction and criticism have appeared in numerous publications, including Maisonneuve, Matrix Magazine, the Montreal Review of Books, and Lemon Hound. Wall’s translations include Vickie Gendreau’s novels Testament (2016) and

Drama Queens

(2019), and Sports and Pastimes by Jean-Philippe Baril Guérard (2017). She lives in Montreal.

We,Jane

is her first novel. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I don’t know that I’ve considered it in those terms or whether I am far out enough from the experience yet to see it clearly, but there was definitely something thrilling about finally feeling the little heft of a physical book. It felt like all the work I’d done over the years had led up to this thing.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I read pretty widely but it always comes back to novels. Fiction just felt like the most natural way for me to explore the questions I wanted to explore.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I spent a lot of time circling the novel before I found my way into it. I read a lot, took a lot of notes, tried on different perspectives. But then once I found my way in, it came faster, if still in fits and starts.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For We, Jane, I envisioned it as a novel from the very beginning. It was a question then of trying to wrap my brain around something that big. Sometimes it felt like trying to hold a jellyfish.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I admit to loving readings. I read aloud to myself as I’m writing so I can work toward a certain rhythm and speed, and so it’s fun to get another opportunity to sing the song you wrote, so to speak.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

There are different questions at different times, and I am maybe more interested in the asking than the answering, but for We, Jane, I was thinking a lot about collectives and the desire to belong. I was also thinking about intergenerational friendships and the way we put people on pedestals and whether we ever forgive them for falling from them, and about duty and inheritance, and about obligation.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have been thinking about this again lately, whether it is to reflect the world as it is or present something else, something new or unexpected, and probably it is some measure of both, in a balance that is ever shifting—I guess I maintain a healthy sense of uncertainty on this front.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Working with an editor was one of my favourite parts of publishing a book—it never stopped feeling like such an honour to have this smart person engaging so thoughtfully with my book, and asking interesting questions, and making suggestions, and just helping me see the novel more clearly, and ultimately make it better.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I remembering reading something once by Alexander Chee where he says something about how being too afraid of your own bad taste is a trap, and I think about that a lot.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (translation to fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s fun to move from writing to translating and back again. Translating lets me “write” in other voices and other styles that I would maybe never take on myself as a writer, which is endlessly interesting. There’s also never a blank page in translating. But then I’m always happy to regain my own voice too.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have a day job as a translator so I often write in the early mornings before work, and then try to steal longer sprints of time, a week or two here and there, where I can hole up and go a little deeper.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Favourite books, old movies, conversations with friends, a lot of long walks.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Summer savory.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Film, often. Photography, sometimes, and occasionally visual art.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many, but among them and off the top of my head, Lucia Berlin, Lynne Tillman, Michael Winter, Zadie Smith, Joni Murphy, Lisa Moore, Nicole Brossard, Gail Scott, Elif Batuman, Deborah Levy, Nicholas Mosley, Jane Bowles, Brigid Brophy.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

The kind of hike that’s so long you might call it a trek.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Lately I wonder how I could spend all day with a nice gang of dogs, is dog foster mom an occupation?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t think I ever seriously entertained doing anything else.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just finished the third instalment of Deborah Levy’s living autobiography, Real Estate, not long after reading her novel The Man Who Saw Everything, and both are brilliant and invigorating. For film, I recently watched Costa-Gavras’ 1969 film Z for the first time and it blew my mind.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am putting final touches on my translation of Alexie Morin’s Open Your Heart, which will be out this fall [ed. note: this interview was conducted in the summer of 2021].

January 29, 2022

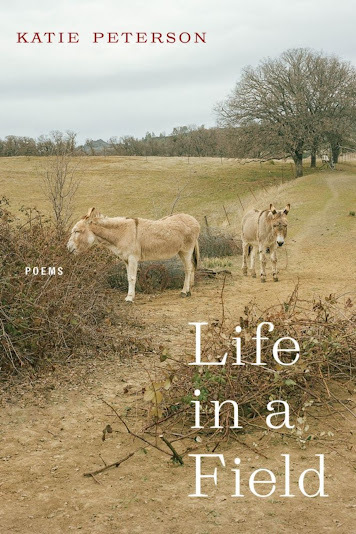

Katie Peterson, Life in a Field: Poems

Maybe it wasn’t a narrative at all. Maybe it was a sequence or a constellation. I think the storyline came after the fact. The lines were drawn through the facts after the facts happened. At the beginning of what is now England, in that dark part of history, humans learned certain abilities, for example, literacy, for example the ability to make pottery on the wheel, and lost them when violence between tribes overtook the skeleton of the Roman system. They used cups and bowls made on home soil for hundreds of years, not knowing how they had been made.

I’m charmed by the prose sweep of Davis, California poet Katie Peterson’s fifth poetry collection,

Life in a Field: Poems

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn, 2021), winner of the “Omnidawn Open,” as judged by New York poet and essayist Rachel Zucker. Peterson is the author of

This One Tree

(New Issues, 2006), which was awarded the New Issues Poetry Prize by judge William Olson,

Permission

(New Issues, 2013),

The Accounts

(University of Chicago Press, 2013), which won the Rilke Prize, and

A Piece of Good News

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019). As her author website writes, Life in a Field is built “as a collaboration with the photographer Young Suh,” a photographer who also happens to be Peterson’s husband. As Rachel Zucker begins her piece to open the collection: “I found the book you are about to read delightfully easy to enjoy, and yet I find it difficult to explain what I love about it, and why I knew, with conviction, that from among a group of extremely strong entries, I would pick this manuscript for publication. Like most great poetry, Life in a Fieldis impossible to summarize or paraphrase. More than most poetry, it eludes formal categorization. Life in a Field is hybrid, mongrel—part allegory, part parable, part fable, part fairytale, part futurist pastoral set in the past or an alternate reality. In this short collection, Peterson has created her own original, heterodox form.” Peterson’s texts exist as the best kind of collaboration, in that the connections between text and image aren’t obvious or even replicated between them. These aren’t pieces depicting in photography or written word, for example, what is offered in the other form; it is as though the text and image exist in a curious kind of conversation with each other, each in turn reflecting upon and building beyond the other. As Peterson offers, herself, towards the end of the collection: “I have always thought that the opposite of chance was focus.”

I’m charmed by the prose sweep of Davis, California poet Katie Peterson’s fifth poetry collection,

Life in a Field: Poems

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn, 2021), winner of the “Omnidawn Open,” as judged by New York poet and essayist Rachel Zucker. Peterson is the author of

This One Tree

(New Issues, 2006), which was awarded the New Issues Poetry Prize by judge William Olson,

Permission

(New Issues, 2013),

The Accounts

(University of Chicago Press, 2013), which won the Rilke Prize, and

A Piece of Good News

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019). As her author website writes, Life in a Field is built “as a collaboration with the photographer Young Suh,” a photographer who also happens to be Peterson’s husband. As Rachel Zucker begins her piece to open the collection: “I found the book you are about to read delightfully easy to enjoy, and yet I find it difficult to explain what I love about it, and why I knew, with conviction, that from among a group of extremely strong entries, I would pick this manuscript for publication. Like most great poetry, Life in a Fieldis impossible to summarize or paraphrase. More than most poetry, it eludes formal categorization. Life in a Field is hybrid, mongrel—part allegory, part parable, part fable, part fairytale, part futurist pastoral set in the past or an alternate reality. In this short collection, Peterson has created her own original, heterodox form.” Peterson’s texts exist as the best kind of collaboration, in that the connections between text and image aren’t obvious or even replicated between them. These aren’t pieces depicting in photography or written word, for example, what is offered in the other form; it is as though the text and image exist in a curious kind of conversation with each other, each in turn reflecting upon and building beyond the other. As Peterson offers, herself, towards the end of the collection: “I have always thought that the opposite of chance was focus.” In this story there is a girl and there is a donkey. The girl approaches the donkey because the girl has something to say. What is it?

Through blocks and stretches of contained prose, she writes the narrative of the donkey, and the narrative of the girl: two threads that run throughout, occasionally meeting, mingling and spiralling out again, in among the other elements. One could offer how Life in a Field is a story of how perception works to telling a story, or how narration shapes perception, whether the truth of the donkey or the truth of the girl, or the truth of the girl within her church, and the boundaries such offers, contains and constricts. “Because we are so far past this story,” she writes, “I wish to linger on it. This story is not your story. You are not meant to relate to it. You are meant to pitch a tent inside this page like a down and out person might do by the American River, under the trestle tracks, where the outgrowth and heat and greenery and shade in proximity to water makes a drought as unlikely as a marriage of equals in a century where women can’t read. You are meant to believe you can live there.” Between text and image, this is a book of mood, tone and shifts, writing far more than the writing might first offer, and threads of narrative that float, rather than hold, hang or pull.

Peterson writes of a donkey, and of a girl. One could almost suggest the collection as a whole—prose poems, poems and image—is constructed not as a narrative-per-se but as a collage across a large canvas, one that speaks around privilege, love, labour, time, decay and empathy. The book, Life in a Field, is simply the final, completed single image; one simply has to stand back far enough to get a good look, and take it all in.