Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 132

March 17, 2022

Ko Ko Thett, Bamboophobia

People in the picture

She who is in the centre of a group photo always smiles miles

higher than those around her

Only when you are in the centre of a group picture you smile

like she who is in the centre of a group picture.

That explains the gravitational pull of the centre. The more

people from the margin push towards the centre the more the

centre loses centrality.

No lens of history is inclusive enough to keep everyone in the

picture. An extremely long shot is necessarily if everyone wants

to be in the picture.

In an extremely long shot people resemble matchsticks.

Matchsticks think everyone is the centre.

In any group photo, people’s shadows can be seen inclining

towards the centre. Knowingly or unknowingly people tend

to move towards what they believe is the centre.

In so doing—

they move history with them.

Comprised as “a collection of new and selected poems published in the 2010s, including over a dozen poems presented in the original Burmese” alongside translations by the author is Burmese-born poet Ko Ko Thett’s latest collection,

Bamboophobia

(Brookline MA: Zephyr Press, 2022). I was immediately struck by the deceptive quality of his lines, a lyric of multiple, overlapping layers presenting itself as being straightforward, but is so clearly not. Thett writes an interesting combination of direct and slant on endurance, trauma, exile and the physical and metaphysical, presenting the familiar in a way difficult to articulate: both tangible and intangible, allowing an effect of lyric smoke, cloud and pure light. “It’s a monsoon.” he writes, to open “A very special day.” “The sun is out. The sky is blue. // But for the better weather, today is no different than any / other monsoon day. today is the first waning day of the / moon. No bank holiday. // There have been several misunderstandings surrounding / today in history. What has been sacrificed? To what end? // Crazy is not nearly insane. Spot on is off the mark.” There is a particular clarity that Thett manages, to write just below the surface of the immediate moment, and of his surroundings and internal monologue, glancing off references as a way to assemble a portrait of resistance: as an articulate, empathetic and thinking human being. “It’s no coincidence that snake venom is packed with its own / counteragent.” he writes, to open the poem “The Ouroborous.” “Snakes are reptiles of repentance.”

Comprised as “a collection of new and selected poems published in the 2010s, including over a dozen poems presented in the original Burmese” alongside translations by the author is Burmese-born poet Ko Ko Thett’s latest collection,

Bamboophobia

(Brookline MA: Zephyr Press, 2022). I was immediately struck by the deceptive quality of his lines, a lyric of multiple, overlapping layers presenting itself as being straightforward, but is so clearly not. Thett writes an interesting combination of direct and slant on endurance, trauma, exile and the physical and metaphysical, presenting the familiar in a way difficult to articulate: both tangible and intangible, allowing an effect of lyric smoke, cloud and pure light. “It’s a monsoon.” he writes, to open “A very special day.” “The sun is out. The sky is blue. // But for the better weather, today is no different than any / other monsoon day. today is the first waning day of the / moon. No bank holiday. // There have been several misunderstandings surrounding / today in history. What has been sacrificed? To what end? // Crazy is not nearly insane. Spot on is off the mark.” There is a particular clarity that Thett manages, to write just below the surface of the immediate moment, and of his surroundings and internal monologue, glancing off references as a way to assemble a portrait of resistance: as an articulate, empathetic and thinking human being. “It’s no coincidence that snake venom is packed with its own / counteragent.” he writes, to open the poem “The Ouroborous.” “Snakes are reptiles of repentance.”

March 16, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with AJ Odasso

AJ Odasso's

poetry, essays, and short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies since 2005. Their first full poetry collection, Things Being What They Are, an earlier version of The Sting of It, was shortlisted for the 2017 Sexton Prize. The Sting of It was published by Tolsun Books and won Best LGBT in the 2019 New Mexico/Arizona Book Awards. AJ holds an MFA in Creative Writing (Poetry) from Boston University. Currently a PhD candidate in Rhetoric & Writing at the University of New Mexico, they teach at University of New Mexico, Central New Mexico Community College, and San Juan College. They have served as one of the Senior Editors in the Poetry Department at Strange Horizons magazine since 2012.

AJ Odasso's

poetry, essays, and short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies since 2005. Their first full poetry collection, Things Being What They Are, an earlier version of The Sting of It, was shortlisted for the 2017 Sexton Prize. The Sting of It was published by Tolsun Books and won Best LGBT in the 2019 New Mexico/Arizona Book Awards. AJ holds an MFA in Creative Writing (Poetry) from Boston University. Currently a PhD candidate in Rhetoric & Writing at the University of New Mexico, they teach at University of New Mexico, Central New Mexico Community College, and San Juan College. They have served as one of the Senior Editors in the Poetry Department at Strange Horizons magazine since 2012. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The Sting of It, my first full-length poetry collection with Tolsun Books, felt like a more significant achievement than my previous two chapbooks with Flipped Eye Publishing. I expanded my Boston University MFA in Poetry thesis manuscript into what is now The Sting of It. Unlike my earlier shorter works, these poems went through an extensive workshopping process with colleagues over the course of a year - which is something I can't say about those earlier manuscripts! They were emotionally and intellectually labor-intensive because they had a responsive, reactive audience right from the start. The Sting of It is also the first work of mine to win a major honor (Best LGBT Book in the 2019 New Mexico/Arizona Book Awards). While the shorter chapbooks (Lost Books, 2010; The Dishonesty of Dreams, 2014) got my name in circulation, The Sting of It put me on the poetry map in a more substantial way. That's a long-winded way of saying the entire process that created this book was life-changing. I owe a great deal to my Boston University MFA mentors and cohort, because they were not only this book's first audience, but helped to shape the direction it took. I was determined to use it as a coming-out on the last few aspects of my queer identity that weren't fully public (intersex, nonbinary). They were supportive and insightful every step of the way, but also constructively critical when it truly mattered!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I had a fantastic teacher in my elementary school gifted program, Mrs. Briggs, who introduced us to full Shakespeare plays as early as 4th grade. We did one production each year in 5th and 6th; in my case, that was The Tempest and Macbeth. The poetry inherent in those lines of dialogue were fascinating to me, and Mrs. Briggs urged me to read Shakespeare's sonnets as a result. Fast forward to my 10th-grade self, newly devastated by Hamlet and my maternal grandfather's death. Among my grandfather's possessions in the basement, my mother found a crumbling 1920s leatherbound edition of Shakespeare's complete works. The sonnets were at the back, after all the plays. I read all of the plays, but it was the sonnets I got stuck on. I started playing with various poetic forms as a result, and I found that I had a knack for it. Coming to prose through the lens of poetry has made me a stronger, more ruthless writer. As a poet, I grew accustomed to counting every syllable and questioning every word-choice. I'm less afraid of aggressively editing my prose as a result; that has been poetry's gift to me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

If I feel strongly about a project concept, I don't have much trouble starting it. Autistic hyperfocus has been a useful tool for me as a writer; as a result, I can work efficiently and linearly. Sometimes I draft a loose outline before I start, but not always. When I outline, it doesn't look like a traditional formal outline with lettered and numbered organizational tiers. It looks more like bracketed paragraphs with sketched-out scenes - what needs to happen in them, snippets of dialogue I know that I want to include. I think in scenes rather than chapters quite a lot of the time, although it's easy for me to conceive of how many scenes need to go in a given chapter, if the project is a chaptered work. Most of my prose out there, up until this point, has been short stories and nonfiction essays. Because I'm a ruthless self-editor, I tend to do that work as I go. The result is that my drafts, when complete, go through relatively little editing at the publisher level. I pride myself on the ability to produce clean (or at least near-clean) drafts. I find that I don't talk about this often, because a lot of writers have quite the opposite experience!

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems begin as compelling first lines or stanzas that I need to follow until they stop (and I often have no idea where they're going, which is the fun of it). In contrast, stories begin as conceptual maps with a discernible starting point and ending. Most of the discovery in those cases comes when I fill in the finer details of plot and characterization within the conceptual framework. Some short stories become long enough to classify as novellas, which is where The Pursued and the Pursuing started its life; it was under half the length it is now. I've written novel-length prose in the past, predominantly in transformative works/fandom contexts. That's the reason I haven't previously sought out publication for my longer prose works. Most of them exist within a sphere where writing is done for the love of it, as well as for the enthusiastic, often immediate exchange of ideas that arises from a highly interactive readership. It's not unusual for prose writers to get their start in online communities where feedback often drives and shapes production. It's not unlike the workshop environment I was talking about earlier! I've made some of my most lasting friendships and mentorships in fandom writing communities, and I wouldn't change that for anything.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I've done a lot of public readings, and I enjoy them a great deal! I teach college students, so being in front of an audience isn't difficult. Moving from Boston to Albuquerque 5 years ago drastically cut down on the number of reading opportunities, although I've taken each and every one I've been offered. Local literary scenes that offer open mic opportunities are a favorite of mine, too, because they're how I got my start with reading poetry publicly in the early 2000s (my first poems were published in 2005, just as I was graduating from college). Having drama background from college, grad school, and community theater also helps.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?

While my academic research and teaching in Composition and Rhetoric have been concerned with theory, I wouldn't say that my writing is heavily theoretical, or even overly concerned with it. The closest I come is queering existing media and texts in my writing, as well as my poetry being concerned with making less talked-about queer lived experience visible. I feel like the most persistent question behind my work is almost always some permutation of What if? This isn't an uncommon question with writers, but from a queer perspective, it's one that still regularly needs asking (and answering).

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of the writer is whatever we most need it to be in a given context. Individual readers seek out literature to fulfil their needs, wishes, and desires; literature has always been there to console, entertain, inspire, provoke, and every motivation in between. For example, now more than ever, writers serve a vital purpose in activism and social justice movements. I rarely think about about the writer as a monolithic figure, if only because diverse writers have always existed and are more visible than ever. We effect change by any and all means possible - or by whatever means are available to us.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I enjoy working with editors, primarily because I enjoy the process of editing my own work and others' work. I've been one of the Poetry Editors at Strange Horizons (www.strangehorizons.com) magazine since 2012, and I've worked as an editor on digital writing textbook projects for several years now. My editorial experience and my experience giving students feedback on their writing have inextricably informed each other. Even though I'm a ruthless self-editor, I hope that teaching has made me a more compassionate editor of others' work. Editing should be a collaborative process, not one in which there's a power imbalance. I've been extremely fortunate in the editors I've worked with for my published poetry and prose works.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

A novelist friend of my family once told me, when I was a teenager who'd begun to show promise as a writer, "Start where the plot looks hardest." This may be why I'm such a linear writer. The beginning always looks hardest, but once I get the ball rolling, the forward momentum tends to be self-sustaining.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I sort of spoke to this in my answer to an earlier question. My background as a poet has permitted me to develop a poetic prose style, and it has made me a better self-editor and more judicious in my stylistic choices. Once I started writing prose, I didn't find it difficult to switch back and forth between that and poetry. The appeal is knowing I'm versatile, I guess!

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have to grab time on evenings and weekends due to my teaching load, so I wouldn't say there's any set routine at the moment. In addition to teaching full time between three institutions, I'm starting my second year of a doctoral program in Rhetoric and Writing at the University of New Mexico (which is also one of the places I teach). A typical day for me starts with responding to emails, grading, teaching one of my class sections, or attending departmental meetings - depending on what day of the week it is, and also depending on how my schedule shifts from semester to semester!

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I tend to rewatch favorite films and TV shows, for some reason - ones emotionally and narratively immersive in ways that I'd like my work to be. are frequently in this rotation, as well as films that might strike the casual observer as bewilderingly random (Benny & Joon,The Last Unicorn, Watership Down, Hot Fuzz, Gladiator, In the Flesh, Gravity Falls, Kubo and the Two Strings, V for Vendetta, Prince of Egypt, the 1980 BBC production of Hamlet, Baz Luhrmann's 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, Groundhog Day, Kevin Smith's Askewniverse films, etc.). It's another list that gets long and eclectic!

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The combination of moss, bluets, and chipped gravel after rain. That's my childhood in rural Western Pennsylvania. Prior to New Mexico, where I'm still a relatively new resident, much of my adult life was spent between Boston, MA and the United Kingdom. New England and England are both defined by old city brickwork and milky black tea as only train station kiosks and pubs can serve it (the tea you can get in other establishments is objectively much better, but it's not as nostalgic).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Drama, music, and visual art - the latter of which I collect from artist friends and hang all over my house. There's so much poetry inherent in those art forms, and I enjoy harvesting it. I listen to music sometimes while I'm writing to enhance both the experience and the emotional pitch of my words.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Almost every writer whose work I've loved, or whose work has had an impact on my life in some way, has influenced my own writing. If I were to start listing names, I'd take up far more space on this blog than you bargained for! Aside from Shakespeare, who I feel looms as large here as Fitzgerald (given The Pursued and the Pursuing is a partial retelling and sequel to The Great Gatsby now that it's in the public domain), Connie Willis has had a profound influence on my approach to storytelling (and probably even on my prose style). When it comes to poetry, some significant modern influences have been T.S. Eliot, Emily Dickinson, Louise Glück, Rita Dove, Mark Doty, Tracy K. Smith, Marge Piercy, Naomi Shihab Nye, Ursula K. Le Guin (who has also influenced my prose), and Patience Agbabi.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a play. I've adapted a text for stage (Chaucer's Franklin's Tale) and directed it during the course of my grad school misadventures, but I have yet to write a play from scratch. Acting and stage work are fun, but writing is even more fun - so doing the writing that permits those other things to happen would be exciting!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I might have gone into counseling, because the pastoral aspects of teaching are some of the aspects I enjoy most about it. I might also have worked in radio or other forms of audio performance; I've always had enthusiasm for it as a medium for both information dissemination and entertainment.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Well, writing is hardly the only thing I do - but I definitely write because I'm miserable if I don't! It connects me to others in a way that I find almost effortless, whereas other forms of social interaction and exchange are often stressful for me. Writing and teaching are the two pursuits I love most in the world.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently reread Christopher Barzak's One for Sorrow, and it was just as brilliant as the first time I read it. I absolutely loved The Green Knight, as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is my favorite vernacular English work from the Middle Ages. It did a spectacular job of capturing the spirit of the source text, and was also surprisingly faithful to it! When adaptations and transformative works hit their narrative mark, it's the most satisfying thing I can think of as a media consumer.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I've been on hiatus for most of this year due to the confluence of heavier than usual teaching loads and work surrounding The Pursued and the Pursuing coming out on September 28th [2021]. I put in a lot of work completing and preparing the manuscript, and the DartFrog Blue team has put in a lot of work to get it out there. Otherwise, the project I need to get back to is my next poetry collection with Tolsun Books. It's tentatively hung on the concept of cataloguing what I'd grab, and why, from various museums around the world depending on what city I'm stuck in when the (theoretical) zombie apocalypse arrives! It's likely going to be called Loot List.

March 15, 2022

today is my fifty-second birthday;

My third pandemic-era birthday. How am I feeling? I’m not exactly sure; I’ll admit to feeling an unease about moving in through my fifties (although: aging is far preferable to death; remember, that my long-running plan includes an eventual passing at the age of one hundred and five). And, given my fiftieth was scheduled two days after original pandemic lockdown, I decided some time ago that I would remain in my forties until this whole period passes (it only seems fair), to only enter my fifties once this is over. To enter my fifties, as one might say, “already in-progress.” We are home, we are home, we are forever home. Staycation day #732, by my count, although Christine has begun the occasional day in the lab over the past couple of weeks (including today). The children remain in their e-learning, at least until the end of the school year.

My third pandemic-era birthday. How am I feeling? I’m not exactly sure; I’ll admit to feeling an unease about moving in through my fifties (although: aging is far preferable to death; remember, that my long-running plan includes an eventual passing at the age of one hundred and five). And, given my fiftieth was scheduled two days after original pandemic lockdown, I decided some time ago that I would remain in my forties until this whole period passes (it only seems fair), to only enter my fifties once this is over. To enter my fifties, as one might say, “already in-progress.” We are home, we are home, we are forever home. Staycation day #732, by my count, although Christine has begun the occasional day in the lab over the past couple of weeks (including today). The children remain in their e-learning, at least until the end of the school year. Where was I last year? The year before that? All of that, in the house.

This morning, Christine and the wee girls an array of cards, gifts. Christine always picks me up curlywurlys from the Scottish and Irish Store, as I recall them from my eastern Ontario childhood; why were they easily available then but not now? Had they a different name? Yesterday, a birthday card from my birth mother, and a text from my eldest. This morning, an email from sister, and half-sister. This morning, before I awoke, as Christine attended Aoife, who barfed into her hands and ran to the bathroom (after which, she claimed, she felt far better). And now, as they’ve breakfasted, downstairs with tablets and Netflix. Christine at the lab.

Note the button I wear in the photo: yes, I shall be wearing this all week (had it on since Sunday, already).

Yesterday, I cleaned the house (convincing the young ladies, finally, to work on their room). Worked on some reviews, addressed an above/ground press mailing. Aiming to spend the next few days reading, perhaps working on novel, or poems, or both, given the clearer-space that March Break allows (not having to worry about e-learning schedules or Guides/Sparks or forest school or anything else). The novel I began during the summer of 2020 (that I haven’t look at since November or so), with pandemic in background of a series of character-threads, including the character Alberta, introduced in my second novel, and furthered through a handful of short stories. Where is she now? The novel, Missing Persons, that wrote her teenaged self near a fictional version of Lumsden, Saskatchewan in the 1980s, an array of short stories that have written her at various points throughout the space in-between there and here, and the new novel, now, as she sits in her empty, widowed house, zoom-calling her preschool-age grandson and slowly working her novel. Everything takes so damned long, it would seem.

Today I am at my desk. Yesterday I was at my desk. Most likely dropping off new above/ground press titles off at the printer’s today. Most likely. Most likely also working on final edits for my fall book with Mansfield Press, a suite of pandemic essays composed across those first one hundred days of lock-down, essays in the face of uncertainties. Stuart Ross has done a remarkably thorough and thoughtful edit. Hoping to be able to use, for cover, the photo that Stephen Brockwell took of us, through our living room window.

And poems. Including this one, my annual birthday missive:

Forty-twelfth birthday

1.

Two years ago,

two days into original Coronavirus lockdown,

I refused: declared my forties persist

until the world re-opens. And only then

to ease into my fifties, already well in-progress

2.

Cobwebs , horizontal; the familiarity

of this single room. To hear sound

in relation: parents, children, siblings. Pets. To sleep,

to sleep, and age across such spectrum.

The limits of this field. How

might my children die? Why were my parents

not my own? Once more into the weeds.

3.

Birthday, birthday: what do you want of me?

Banal acquiescence

of cake, pints, comic books ; has nothing changed

across these thirty-odd years? A dreamlike curiosity; held down

with equations. The math is nigh impossible.

4.

My third annual isolation birthday. A rehearsal

of inarticulate space,

a glass, reflects. This breath by breath. Half-century, plus. A hand

between palms.

PS: AND ACCORDING TO CANADA POST, COPIES OF MY NEW POETRY TITLE WITH UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY PRESS (CURRENTLY AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER), SHOULD BE LANDING ON MY DOORSTEP TODAY?

March 14, 2022

Spotlight series #71 : Matthew Firth,

The seventy-first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa writer Matthew Firth.

The seventy-first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa writer Matthew Firth.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall and Toronto writer Bahar Orang.

The whole series can be found online here.

March 13, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Carmella Gray-Cosgrove

Carmella Gray-Cosgrove is the great granddaughter of Jewish immigrants and early French and Irish settlers. She was raised in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver on the traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples and lives with her partner and child in St. John’s, on Ktaqmkuk, the traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq and the ancestral homelands of the Beothuk. Her fiction has appeared in Prism international, Broken Pencil, The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review, and elsewhere. Nowadays and Lonelier was a finalist for the NLCU Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers. She holds a master’s degree in Geography from Memorial University and was an F.A. Aldrich Fellow.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book is also my only book! I’m working on a new book now but it’s in very early stages of first draft writing. My life changed while I was writing my collection of short stories for a bunch of reasons, but primarily because I wrote the bulk of it just after giving birth and during the first year of my kid’s life. So, the changes that I experienced were book related, but were also because the book and parenthood were linked experiences. In retrospect, I see that the stories in the book are all reflections on times and places in my life that are pre-parenthood, and were written while I was digesting my new life and recalling experiences I will never have again because of this big shift that happens with a kid where suddenly freedom looks different, where suddenly, for me, wild times and erratic decisions are no longer sustainable parts of existence. And so the book is maybe, in part a farewell to my past. The novel I’m writing now is partly told from the perspective of a mother, a perspective I can newly write in a concrete way that I didn’t have access to before becoming a parent.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Oh god. I wrote so much terrible poetry and continue to. I don’t think I came to fiction first, I think fiction is the only type of writing I’m not embarrassed to show other people. I’ve written and read stories obsessively since I was a kid. It’s just a big part of my life. My parents gave me that love of fiction, my mum as a reader, my dad as a writer. But I also have many journals full of very awful poems. I do write some non-fiction, and enjoy it, but I find it to be soul-bearing in a way that is almost intolerable for me. I am fairly private and when I have written personal essays I’ve really struggled knowing that people I don’t know will have these bits of intimate information about my life. At least in fiction there is plausible deniability. And the ability to make lives more interesting is irresistible.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I produce good writing very unpredictably, but I write almost every day. When good writing comes it is fast and the first drafts are fairly clean. But there are long stretches of unusable and frankly really bad writing in between these fits. While I was writing Nowadays and Lonelier, I would have a bunch of story ideas stewing at once and would keep them in my brain and in jot notes until they festered out onto the computer, usually in one fell swoop.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I have only really written short things, short fiction, some of which has amassed into this book. But I’m working on a novel now and am struggling in ways I hadn’t anticipated. I find short stories appealing and non-threatening because there doesn’t have to be total closure. Not everything is going to be solved or answered. I am finding the idea of working on a novel is very daunting because it is implicitly a book, a whole, a complete thing. Whereas, writing a collection of stories, if you bail on the book, you still have the stories.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love readings but find them so nerve wracking. My publisher recently provided me with an online session with this amazing acting coach, Sara Bynoe, to get tips for reading and it was the most helpful and wonderful thing. I had a reading a month after the session where I used the techniques Sara gave me and it was the best reading I’ve ever done. I love performing but have this introverted part of my personality that I have to work really hard to quell. But I am working on it and so far so good.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I write and think a lot about poverty and class and how these conditions affect relationships. I live in this very privileged reality where I can move freely between socioeconomic groups and have moved in this way throughout my life since being a kid, despite being brought up in poverty and as a product of my whiteness, but also because of my education and my body, my gender, my family, all these factors. So I write about that a lot, even if it’s not always explicit. About who has this freedom and who doesn’t, and why, and how. About how class privilege and class mobility change the ways we interact with people and move through the world.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t know the answer to this but I think about this question a lot. I think there has been a move toward a public demand that art and writing be productive, be toward an end, or be social justice, or be all things, cover all the bases. But I think, maybe the role of the writer is just to write the stories they think are important and urgent for them, for whatever reason, whether it’s political or to make change or to explore language or to experiment with form, or maybe just to survive this hard world. And maybe the role of the reader is to decide if it’s good. And maybe the role of the society is to decide if it’s relevant. To keep or to discard. As artists and writers and readers and as the audience and sometimes as members of all of these groups at once with the ability to project our thoughts to wide audiences over the internet, I think we get confused about what our roles are, and what they should be and so we make demands when not long ago we would have made criticism, had a conversation. More than anything, perhaps this is the role of the writer, to help us all think and talk and be critical.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love everyone who has ever edited my writing. It is such a beautiful thing, to have someone, often someone you don’t know, read your writing and bring all their difference of experience and all their thoughtfulness to the work. With magazines and books you know that when an editor is working on the piece, they chose to work on it. It is work they like and they want to make it the best it can be. There is no one better to edit your work than someone who has chosen it from a slush pile or from a mass of agent submissions. The wonderful thing about writing short stories is that each story that is published in advance of the collection has at least one editor and then the collection has at least one editor. I try to be as open as possible to edits, to set aside my ego and to try to see the writing as clearly as possible. I am so grateful to the many many editors my book had, but especially for Shirarose Wilensky, and for the hours of thoughtfulness and clarity of mind and empathy that editing requires.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

There is so much good advice! I love that kinda cheesy quote from Annie Dillard about not saving anything. She says:

Spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give now.I think about that often as I have an impulse to hoard. On a more personal level, I think the big and unromantic advice, or just practical measure that I have heeded over the past ten years talking to so many people, but especially my mum who is a visual artist and obviously also a parent, as well as my mentor, Lisa Moore and my dear friend Susie Taylor, is that I need to write every day even if it sucks, even if it is painful, the most important thing is always to do it and if I always do it, eventually it will be okay, maybe even good. This really became more important when I had a kid and time was suddenly not in surplus. Even if writing just happens for 15 minutes in a day, it still has to happen.

The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing routine really depends on my childcare. I write as my full-time job now, as in, it’s my only job, which is amazing. But full-time when also parenting and living on a tight budget and living through a pandemic is an unpredictable thing. Under ideal circumstances I write in the morning while my kid is in childcare. In the winter I write a lot more than in summer, which is a very short season in Newfoundland, where I live, and so must be taken full advantage of. I free-write first thing in the morning when my brain is most alert, then take a break to get my kid and get him fed and down for his nap. I try not to get too sleepy and then do editing and admin work (submissions, grants, editing for other people) in the afternoon until about 3 when he wakes up, which he just did at this very moment. Since March 2020 this has obviously looked different at times, but this is the ideal scenario.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

For years I have had a list of things to do when I’m struggling up on the wall next to my desk. It says: read, exercise, write about what you’re reading, write anything, listen to something good. Moving helps me a lot. I listen to fiction podcasts most days. I try to read outside my interests. All these things help. But, much to my dismay, and a reality I often try to avoid, is that what helps most is to just sit back down and plow through it.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

In Vancouver, mold. Wetness. That smell of mildew so common in the Pacific Northwest. The smell of the butcher on Keefer Street. Overripe fruit. The smell of sweet bread and coconut buns from Maxim’s Bakery. The very specific tang of the Strait of Georgia. The smell of linden trees in Mount Pleasant in summer, that almost bitter smell of cherry blossoms on tenth avenue in spring. The smell of days and days of rain on concrete. But I’ve lived in Newfoundland for over a decade and the smells here are creeping into my heart too. The Atlantic smells so different. The oysters from here taste different. The smells are colder and less full of algae and that rank smack of the seaweed. Here smells like evergreens and iceberg-fresh water and wood fires and grains boiling at the brewery on Leslie Street. My house smells like hundred-year-old timber, musty and wet, but also like food. Oregano, sage and garlic hanging from the railing to dry.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My understanding of the world, my interactions with my community and family, and so also my writing are of course influenced by all these things. But maybe particularly by visual art. I think and write about art a lot, and it mediates the way I experience the world. While I was writing the stories that came to make up my book, I looked at a lot of art by Sandeep Johal, Janice Wu (who drew the cover image), Jessie McNeil, my mom Joyce Cosgrove, Kym Greeley, and also a lot of old and really famous art while travelling, in Italy and in Norway, before the pandemic. Jessie McNeil, who is a dear lifelong friend and who makes incredible collage scenes, recently showed me Louise Francis Smith’s photographs of Chinatown in Vancouver and they so exactly capture the details of that neighbourhood where I grew up, the landscape that shaped my whole life and where much of my writing takes place. I also spend a lot of time outside, in my garden and in the forest. Most of my writing is conceived while I pull knotweed, hemlock and creeping buttercup out of my garden.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are too many to list. Short story writers who have really affected me are Edwidge Danticat, Carmen Maria Machado, Ottessa Moshfegh, Souvankham Thammavongsa, Lisa Moore, Jack Wang, Miranda July, Heather O’Neill. The list could go on forever. I love Muriel Spark. My work is really influenced by my friends’ writing, Susie Taylor’s work is brilliant and Eva Crocker too. I’ve had the pleasure of reading their work in all stages and obviously there is always a conversation in the writing when you’re sharing work in that way.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Finish my novel! And visit my family’s homelands, Gomel in Belarusin particular, and the Pale of Settlement from where my paternal great-grandparents fled in the early 20th century.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would really like to teach writing and literature. That’s the long game. I love teaching and have been so lucky to have great teachers.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was working doing harm reduction and housing support work after I finished my MA and loved that work. But it’s emotionally exhausting and I didn’t ever have time or creative energy at the end of a work day to write or really do much at all except subsist. When I was on parental leave after giving birth, I realized this was maybe my one shot to try and make career out of writing full time while I had EI and an infant who napped a lot, and a lot of family support to help make it happen. I don’t think there was ever really another option though. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was a kid, I just didn’t have the confidence and didn’t realize it was a thing I could do as a career until I was 31.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m reading Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli right now and I love it so much. Luiselli is a master of weaving together history, politics, philosophy, and family drama. Girl, Woman, Other, by Bernadine Evaristo is the best book I’ve ever read. Loitering With Intent, by Muriel Spark is a close second. I’m terrible at watching films, which is a big point of contention in my relationship. I like watching trash.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a novel! It is early first draft days yet, so I can’t say much about it, but I’m excited!

March 12, 2022

Stuart Ross, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers

When I worked with Dave McFadden on his volume of selected poems, Why Are You So Sad?, I thought we would reproduce the poems exactly as they had been originally published, and in chronological order. But first the order thing: Dave wanted them to appear in random order. He presented me with a random order for the poems in the book, but I think the order wasn’t entirely random. Dave was wily that way. But the other thing: Dave wanted to edit his poems for this new volume. He was a better poet now than when he had originally written those poems in the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s, and he could make those poems better. In several of his poems from the 1960s, Dave replaced the word love with the word thing. And it was true: it made the poems better.

So Dave was a poet who put the word love into his poems when he was in his twenties and took the word love out of his poems when he was in his sixties.

Here’s what I do: I put the word hamburger in my poems when things are getting a little too heavy. Because the word hamburger makes you laugh. So this manoeuvre makes a heavy poem lighter. You can lift it more easily.

The latest from Cobourg, Ontario poet, writer, editor and publisher Stuart Ross is

The Book of Grief and Hamburgers

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022), a blend of essay, memoir and prose poem that moves its slow way through and across an accumulation of grief and personal loss, attending the personal in a way far more vulnerable than he has allowed himself prior. As the back cover attests, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers was composed “during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, shortly after the sudden death of his brother – leaving him the last living member of his family – and anticipating the death of his closest friend after a catastrophic diagnosis, this meditation on mortality is a literary shiva, a moving act of resistance against self-annihilation, and an elegy for those Stuart loved.” The form of lyric homage and recollection certainly isn’t new, although one might think it not as prevalent as it might be, and I can only think of a handful of examples in Canadian writing over the past thirty years, such as George Bowering’s book of prose recollections, The Moustache, Memories of Greg Curnoe (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1993), James Hawes’ writing Peter Van Toorn through his new chapbook

Under an Overpass, a Fox

(Montreal QC: Turret House Press, 2022), Erín Moure writing her late friend Paul through

Sitting Shiva on Minto Avenue, by Toots

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2017) [see my review of such here], or even Sharon Thesen writing Angela Bowering through her

Weeping Willow

(Vancouver BC: Nomados, 2005), a chapbook-length sequence that later landed in her full-length

The Good Bacteria

(Toronto ON: House of Anansi, 2006).

The latest from Cobourg, Ontario poet, writer, editor and publisher Stuart Ross is

The Book of Grief and Hamburgers

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022), a blend of essay, memoir and prose poem that moves its slow way through and across an accumulation of grief and personal loss, attending the personal in a way far more vulnerable than he has allowed himself prior. As the back cover attests, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers was composed “during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, shortly after the sudden death of his brother – leaving him the last living member of his family – and anticipating the death of his closest friend after a catastrophic diagnosis, this meditation on mortality is a literary shiva, a moving act of resistance against self-annihilation, and an elegy for those Stuart loved.” The form of lyric homage and recollection certainly isn’t new, although one might think it not as prevalent as it might be, and I can only think of a handful of examples in Canadian writing over the past thirty years, such as George Bowering’s book of prose recollections, The Moustache, Memories of Greg Curnoe (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1993), James Hawes’ writing Peter Van Toorn through his new chapbook

Under an Overpass, a Fox

(Montreal QC: Turret House Press, 2022), Erín Moure writing her late friend Paul through

Sitting Shiva on Minto Avenue, by Toots

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2017) [see my review of such here], or even Sharon Thesen writing Angela Bowering through her

Weeping Willow

(Vancouver BC: Nomados, 2005), a chapbook-length sequence that later landed in her full-length

The Good Bacteria

(Toronto ON: House of Anansi, 2006). The difference in the examples I’ve cited, of course, is that each of these were composed around a single person, whereas Ross explores the layering and accumulation of grief itself, one that has built up over the years through the deaths of his parents, and a variety of friends, mentors and contemporaries including David W. McFadden, Richard Huttel, John Lavery, Nelson Ball and RM Vaughan. While this particular project was triggered by the sudden and unexpected loss of Ross’ brother Barry in 2020, twenty years after the death of their brother, Owen, and through hearing of the terminal cancer diagnosis of his longtime friend, the Ottawa poet Michael Dennis (one shouldn’t overlook, as well, the simultaneous loss of their beloved dog, Lily), all of these relationships are referenced, explored and layered through an attempt, through the narrative, to come to some kind of, if not conclusion, an acknowledgment of how best to allow for this space, and to move forward.

There is very much an “I Remember” element to Ross’ collection—from Georges Perec’s infamous Je Me Souviens (1978), which was, itself, influenced by Joe Brainard’s I Remember (1975)—but one that moves through the larger subject of multiple connections and ongoing conversations. In certain ways, Ross examines the subject of grief in ways similar to American poet Heather Christle writing on the subject of crying in her own non-fiction memoir, The Crying Book(New York NY: Catapult, 2019). And still, unlike Christle’s exploration blending memoir with studies, stories and statistics, Ross works through a far more personal list of references, including elements of his prior writing and personal library, and recollections of each of those friends and family members.

Is the death of one person the thing that launches grief? What about two people? Or three or four? What happens when your entire family is gone?

So many members of my family disappeared in the Holocaust. How can I even complain about anything?

Am I mistaking self-pity for grief?

There is an interesting way he threads a conversation through the bones of the narrative, exploring how he’s written heavy subjects over the years, adding the word “hamburger” to poems (although I’ve long seen his use of the word “poodle” in similar terms) as a way to lighten, acting as both distraction and counterbalance against his darker (self-described “sad sack”) impulses. And yet, who, at any given point, wouldn’t wish to distract themselves from overwhelming loss? The distance he travels and the ground he covers through The Book of Grief and Hamburgersis quite extensive, and, despite knowing that such projects aren’t enough to properly process any amount of grief, there is certainly something to be said for capturing such examinations in print. This really is a remarkable book, as Ross writes of grief and he writes of hamburgers, fully conscious of how the word had become a personal kind of safe-word. He connects this string of losses, and the tether that pulls once more as each new loss takes hold, even as he catches himself lob a hamburger into the fray. Although, I, myself, might have hoped for more poodles.

This book feels like one big hamburger. My intention was to make myself face things I don’t think I’ve succeeded in facing.

To frighten myself.

To make myself cry.

To make myself mourn.

To hurl myself into the bubbling vat of grief.

But I won’t do it.

It’s not like I don’t cry, though. I cry pretty much every day, even if just for a moment.

But isn’t grieving more than crying? Isn’t it a “coming to terms”?

I have never come to terms.

I want to force myself to come to terms. That’s what I’m trying to do here.

Won’t you please join me?

March 11, 2022

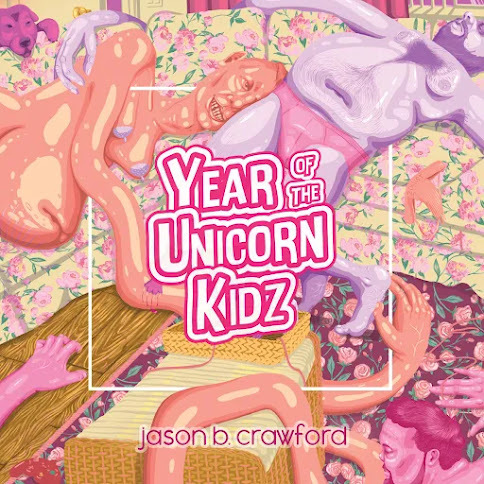

Jason B. Crawford, Year of the Unicorn Kidz

Some debts can only be paid with the body. And in jason b crawford’s rebellious and desirous debut, a life is the cost of an errant belonging. Crawford shows that to exist outside of the paradigms of a racist and homophobic society, one becomes even more indebted to it. Blood is the price, token money, a down payment. The poems in this collection are full of everything a queer Black boi should and should not say, should and should not do—‘i went where the boys found me irresistible and i made it out alive’—now what must be paid for that? Throughout this collection is the paranoia that the piper/the collector/the reaper will show at any minute. Yet, despite the foreboding, there is a precarious life that continues as it must. (“Forward,” Jonah Mixon-Webster)

American poet Jason B Crawford’s full-length poetry debut, following chapbooks through Variant Lit and Paper Nautilus Press, is

Year of the Unicorn Kidz

(Knoxville TN: Sundress Publications, 2022), a book that works through trauma, cruising, sex and what one keeps from one’s father. “What is the act of playing with dolls,” Crawford writes, to open the poem “Boys and Dresses,” “other than putting the boy in a dress? // What is the act of homophobia / other than ripping the doll from the boy’s fingers? // What is this act other than calling your own kin / a faggot, removing him from every family photo?” In certain ways, Crawford mines a similar terrain as does Toronto poet Jake Byrne, guest editor of the recent “Daddy” issue of CV2: queer identity and sex, experiences with homophobia and marked or broken connections including family, personal and intimate. “The way to a man’s heart,” Crawford writes, as part of the poem “Anatomy of the Jaw / Lessons on giving head,” “is through his gutting/how much / of him you digest in a single sitting / It is through the slick slit / and how it hungers / to be filled/with him / it is never a question of when is dinner / rather where/and what limit / is he allowed to consume [.]” Composed through forms including the English-language ghazal, the pantoum and the sonnet, there is something interesting in the way Crawford utilizes formal constraint and poetic form, quite possibly, as a certain kind of stability through which to explore and articulate deeply personal, intimate and occasionally messy content. In this way, one might also think of Diane Seuss, and the one hundred and twenty-eight sonnets that make up her

frank: sonnets

(Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. As part of the poem “A Pantoum of Yellow Fields,” Crawford writes:

American poet Jason B Crawford’s full-length poetry debut, following chapbooks through Variant Lit and Paper Nautilus Press, is

Year of the Unicorn Kidz

(Knoxville TN: Sundress Publications, 2022), a book that works through trauma, cruising, sex and what one keeps from one’s father. “What is the act of playing with dolls,” Crawford writes, to open the poem “Boys and Dresses,” “other than putting the boy in a dress? // What is the act of homophobia / other than ripping the doll from the boy’s fingers? // What is this act other than calling your own kin / a faggot, removing him from every family photo?” In certain ways, Crawford mines a similar terrain as does Toronto poet Jake Byrne, guest editor of the recent “Daddy” issue of CV2: queer identity and sex, experiences with homophobia and marked or broken connections including family, personal and intimate. “The way to a man’s heart,” Crawford writes, as part of the poem “Anatomy of the Jaw / Lessons on giving head,” “is through his gutting/how much / of him you digest in a single sitting / It is through the slick slit / and how it hungers / to be filled/with him / it is never a question of when is dinner / rather where/and what limit / is he allowed to consume [.]” Composed through forms including the English-language ghazal, the pantoum and the sonnet, there is something interesting in the way Crawford utilizes formal constraint and poetic form, quite possibly, as a certain kind of stability through which to explore and articulate deeply personal, intimate and occasionally messy content. In this way, one might also think of Diane Seuss, and the one hundred and twenty-eight sonnets that make up her

frank: sonnets

(Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. As part of the poem “A Pantoum of Yellow Fields,” Crawford writes: I am piss drunk off love for you

or the 5 shots of whiskey that smoke like

midsummer and stain the chest like drenched leaves

We roll around the dry grass, dogs shattering in heat

or the shots barreled into the moon still smoking

He asks if he could kiss me on the rough edge of my thigh

Rolls around me like a field of shattered glass

and this time I am not too drunk to tell him yes

March 10, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sydney Hegele

Sydney Hegele (formally Sydney Warner Brooman) lives in Toronto, Canada with their fiancé and French bulldog. They are the author of the short fiction collection

The Pump

(Invisible Publishing 2021), and an alumnus of the Tin House Summer Workshop (2021) and the Lighthouse Summer Workshop under Sheila Heti (2021).

Sydney Hegele (formally Sydney Warner Brooman) lives in Toronto, Canada with their fiancé and French bulldog. They are the author of the short fiction collection

The Pump

(Invisible Publishing 2021), and an alumnus of the Tin House Summer Workshop (2021) and the Lighthouse Summer Workshop under Sheila Heti (2021). 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having a book out has allowed me to have a lot of interesting conversations with people who care about the same things that I care about, through workshops and readings and festivals–opportunities that I’ve only really started getting since The Pump was released.

The current project I’m working on feels very different from The Pump. Short stories feel like little lightning strikes to me – like bright bursts of moments or feelings or realizations. Novel writing feels like building a dollhouse. Slow, careful painting. Designing little objects. The Pump felt easier somehow, like twelve short trips up and down steps, back and forth, going back over the ground I cover, whereas writing my current project feels like walking a tightrope.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As a kid, I wrote a lot of nonfiction. I would create little books about subjects I thought I was an expert on, like My Big Book of Art, or My Big Book Of Dolphin Friendly Tuna. I came into poetry when I was about eleven, and fiction-writing when I was thirteen.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m a notorious “edit while I work” kind of writer. My first drafts usually take me a long time, but once they are done, the line edits in subsequent drafts are a lot easier because I’ve already put a lot of thought into the diction and syntax. My second drafts are usually the most difficult, where I figure out what I’m really trying to say and how I’m going to say it.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I write all my fiction scenes as dialogue on my phone first, with little notes in between like “insert description of house here” or “paragraph about what it means to be a mother”. My very first drafts of anything look very much like screenplays, with character action in-between lines. If I think a scene is working, I transfer it to my computer and add everything else (thoughts, actions, descriptions). I have one master document where the book itself is written in order, but I’m normally cutting and pasting these pre-made scenes into the master rather than writing in the document. I’m a pretty intuitive writer in terms of drafting whatever scenes I feel like writing at one moment, but I always like to have an anchor document where I can see my progress in a linear way.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I read all my fiction out loud in front of my computer as part of the editing process to see how it sounds before I submit anything anywhere, so readings feel like a good extension of that. I’m a former theater kid, so the musicality and cadence of my lines, even in fiction, are important to me. I see readings less as reading a piece and more as performing it for others. If I have lines that I wouldn’t want to read out loud to someone, I wouldn’t include them in the final draft.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I feel like my work is frequently trying to answer two questions. The first is, can good people do bad things, and vice versa? And the second is, is it possible to separate where you grew up from who you are? I think about these a lot, and I don’t think my work fully succeeds in answering them, but rather, works very hard to look for the answers.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think that writers can have a lot of different roles. The ones I personally find important are to make readers feel seen, heard, and represented, and to encourage/mentor the next generation of writers behind us.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find it essential to my work. The Pump owes so much of what it is to Annick MacAskill. Finding an editor who had the same vision and excitement for my work as I did really turned my work into what it needed to be.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was twelve, a woman sitting next to my mother and me on a GoBus told me that life is not about finding the right person, but about being the right person. I haven’t been able to shake that moment from my head since. I think about it often.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to screenplays to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Although I do write in different genres, I find switching between projects very difficult. Even switching between a short story and a novel is hard for me. When I’m writing something that I want to submit somewhere, I think about the project all day every day until it is finished. To me, each new thing is at the bottom of a lake, and I need time to swim down farther and farther to get to the heart of what I want to write about, and if someone were to tell me to come up for air and dive into a different lake, I would say “But I need time to swim back up!”

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I admittedly don’t write every day. I’ve tried things like morning pages, but they don’t really work for me. I write the outlines and dialogue of my scenes on my phone in bed or while I’m on transit whenever I feel like it. When I have a day off from work and can finally write out the scenes I want on my computer, I have a backlog of them from my phone to choose from. When I’m on deadline, I write new material in the morning, and edit at night, as many days as I can without burning out.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

My writing usually gets stalled when I think a piece or a chapter isn’t working, and I don’t think that it’s fixable. Rather than throwing it away like I want to, I show it to a friend, usually another writer, who can help. I don’t often run out of things to write about, but I am often frozen by the fear of writing something bad.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Algae and rotting fish (Lake Ontario)

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

A few are lake Ontario and the Niagara escarpment, Pre-Raphaelite art; summer camp songs, used cars, and borrowed, stolen, and inherited objects that sit around houses. I’ve also had a couple of strange jobs that bleed into a lot of house descriptions that I write (I spent one summer as a pioneer village actor, and another as a house brick and patio stone house supplies salesperson).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Gordon Korman and Roald Dahl are definitely the reason I started writing so young. I think that every writer has that one book they read at a young age where you read it and go “Oh, that’s why they care about the things they do” and mine is Danny The Champion of The World . If I had to choose one thing that my writing is about, I would choose “complicated parent-child relationships in strange, almost surreal scenarios”, and so much of that comes from Dahl.

Others are definitely Heather O’Neill, Sylvia Plath, Daisy Johnson, Sheila Heti, Homer, Alison Bechdel, Markus Zusak, and J. D. Salinger.

Currently, I’m obsessed with Brandon Taylor’s work (including his newsletter).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I hear that Goat Yoga has really taken off. I’d like to try some Goat Yoga.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wanted to be a marine biologist when I was young, until I realized I was afraid of accidentally touching fish. This writing thing is probably for the best.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve never entertained the idea of not writing. Every time I have a career-related existential crisis, I always imagine myself taking on a new career in addition to writing books. I think I will be writing new work right up until I die. I can’t imagine a life where that isn’t the case.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe. I would recommend it to everyone and anyone. The last great film I watched was Inherent Vice . I wouldn’t necessarily recommend this to everyone, but I’m a sucker for a well-written script and an interesting aesthetic.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m redrafting my debut novel before it goes out on submission with my agent early next year. It’s about sirens (the bird kind) and taxidermy and priesthood and fortune-telling and carnivals and tourism and motherhood and some other things. It’s ruining my life (in a good way?)

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 9, 2022

Touch the Donkey : eighth anniversary sale,

To celebrate the eighth anniversary of the quarterly Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] this April: anyone who subscribes (or resubscribes) anytime between now and the end of April 2022 has the bonus option of three (3) items: three Touch the Donkey back issues of your choice, OR three above/ground press (2021 or 2022) titles of your choice (while supplies last) OR any combination thereof.

Issue #33 of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] lands on April 15, 2022.

2021-2022 above/ground press titles include chapbooks by: Rob Manery, Lillian Nećakov, Amanda Earl, Karl Jirgens, df parizeau, Wanda Praamsma, Lydia Unsworth, Michael Schuffler, rob mclennan, Natalie Simpson, Nate Logan, Stan Rogal, Sean Braune and Émilie Dionne, Urië V-J, Sarah Rosenthal, Andy Weaver, Simon Brown, Mayan Godmaire, Phil Hall, Kevin Varrone, Susan Rukeyser, Barry McKinnon, Benjamin Niespodziany, Ken Norris, Terri Witek and Amaranth Borsuk, George Bowering, Franklin Bruno, Gary Barwin, Emily Izsak, Jen Tynes, Valerie Witte, Robert Hogg, Ken Sparling, Jessi MacEachern, Nathan Alexander Moore, Katie Naughton, Summer Brenner, Monica Mody, Kōan Anne Brink, Gregory Betts, Michael Sikkema, M.A.C. Farrant, Jamie Townsend, Conor Mc Donnell, Adam Thomlison, Alyssa Bridgman, James Lindsay, David Miller, Amish Trivedi, Ava Hofmann, JoAnna Novak, Sandra Moussempès (trans. Eléna Rivera), Helen Hajnoczky, Edward Smallfield, Valerie Coulton, James Hawes, Anik See, David Dowker, Shelly Harder, Alexander Joseph, Joseph Mosconi, Brenda Iijima, Al Kratz, Saeed Tavanaee Marvi (trans. Khashayar Mohammadi), Jason Christie, katie o'brien, N.W. Lea and Andrew Brenza.

Canadian subscriptions $35 for five issues / American subscriptions $40 / International subscriptions $50 / All prices in Canadian dollars /

To order, e-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button at www.robmclennan.blogspot.com or www.touchthedonkey.blogspot.com

Issues are also available as part of the above/ground press annual subscription.

Because everybody loves a birthday. Who doesn’t love a birthday?

Touch the Donkey. Everywhere you want to be.

March 8, 2022

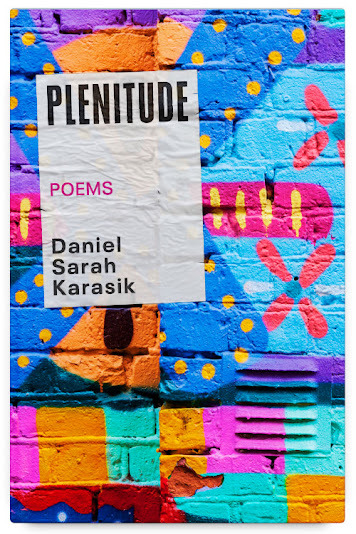

Daniel Sarah Karasik, Plenitude: Poems

messianic time

imagine there were no oppression to shape our identities. instead:

limitless forms of descriptive difference not essentialized and

politicized by violence. if we were to say I in such a world, we might

mean almost nothing but a historied, futured, networked locus of

desire

Toronto writer and organizer Daniel Sarah Karasik’s fifth book and second poetry collection, following the full-length poetry debut, Hungry (Toronto ON: Cormorant Books, 2013), is

Plenitude: Poems

(Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2022). Composed as a collection of urgencies, desires and reclamations, Plenitudeis composed in six sections—five sections of shorter lyrics and a long poem—and opening salvo, the short lyric burst “messianic time.” As Karasik writes as part of the poem “radiant incipience”: “when the police locked comrades / in the library and lied / about it, our chant said / trans rights are human rights, / but what we meant was / rights won’t save us / if we don’t protect each other.” Plenitude offers a lyric attending to “our difficult present,” writing the imperils of police brutality, anti-trans violence and of the possibilities of a body not held by gender boundaries. “as in strife and envy and competition and violence yes sometimes / ineluctably violence but outside the death cult of capital,” Karasik writes as part of the sequence “trans-socialist,” a poem that makes up the entirety of the book’s second section, “of the wage. // as in no bosses no cops no shortcuts no utopia no final peace no (in / the final analysis) final poem against the police.” Or, as part of the title poem, which opens the third section: “Interchangeable / to suit the day. And also would like Gender / to be overthrown, and every woman / now alive and also every boi / to adore me—goals / that need not be contradictory.”

Toronto writer and organizer Daniel Sarah Karasik’s fifth book and second poetry collection, following the full-length poetry debut, Hungry (Toronto ON: Cormorant Books, 2013), is

Plenitude: Poems

(Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2022). Composed as a collection of urgencies, desires and reclamations, Plenitudeis composed in six sections—five sections of shorter lyrics and a long poem—and opening salvo, the short lyric burst “messianic time.” As Karasik writes as part of the poem “radiant incipience”: “when the police locked comrades / in the library and lied / about it, our chant said / trans rights are human rights, / but what we meant was / rights won’t save us / if we don’t protect each other.” Plenitude offers a lyric attending to “our difficult present,” writing the imperils of police brutality, anti-trans violence and of the possibilities of a body not held by gender boundaries. “as in strife and envy and competition and violence yes sometimes / ineluctably violence but outside the death cult of capital,” Karasik writes as part of the sequence “trans-socialist,” a poem that makes up the entirety of the book’s second section, “of the wage. // as in no bosses no cops no shortcuts no utopia no final peace no (in / the final analysis) final poem against the police.” Or, as part of the title poem, which opens the third section: “Interchangeable / to suit the day. And also would like Gender / to be overthrown, and every woman / now alive and also every boi / to adore me—goals / that need not be contradictory.” In Plenitude, Karasik writes a lyric around gender, writing into a sense and a self, including the political mechanisms of required resistance to exist as a transgender person in the world, as well as the energies required, and the exhaustions that would surely follow. “The poets have described the world;” they write, to close the poem “Regarding the Prophetic Tradition,” “the point, however is / to change / yourself into the kind of person / who can suss out where the most / effective point of struggle is / and go there, or support those / who are there already, on life’s side. / And to get free. Which is to say, / to sing desire into a loving, / fighting sociality.” At turns the poems are, as John Elizabeth Stintzi suggests via cover blurb, political, frisky, personal and furious, as Karasik writes of being in the world as, by itself, the purest act of resistance; a way through which to safely emerge and safely love. As the title poem ends:

I don’t as much.

I blink, demure.

Solicitously, I extend

my round bottom to you.