Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 131

March 27, 2022

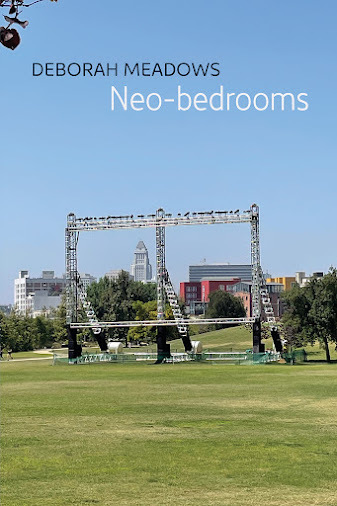

Deborah Meadows, Neo-bedrooms

So the story involved (as a mode) a crisis of confidence, so begin to hear as many upon a time, pulled up stakes, no longer housed with hucksters but conditional subtle ones—calibrated a wisp, tongue flap, holy allegory in smithereens, our task, our grief. (“keep profane objects close, the argument”)

Los Angeles poet Deborah Meadows’s latest [see my review of her 2013 selected poems here] is the poetry title

Neo-bedrooms

(Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2021), an assemblage of lyric bursts, language riffs and meditations, composed through folding one line overtop another in sequence, akin to a suite of sequences assembled into book-length shape. “Nothing is given that condences down.” she writes, to open the poem “Hammer of Justice.” “Can we consider this defaced old-age couple a form of iconoclasm?” Her writing exists as a rush, propelled by cadence and carefully-placed words. As part of the prose sequence “Croud-prone,” she writes: “Funeral comes forth once. Heavy-laden steps, that uncanny shift from / time to not. Cloud’s perimeter somehow contained in front right here: / haloed filthy puddle. Clouds.” There are echoes in her work of the prose poems of Rosmarie Waldrop, although looser in her lyric, and without Waldrop’s specific complexities writing between a German structure and an English tongue; Meadows follows a delicate line up against instability and insecurity, writing on making, thinking and artistic production. “When field workers transferred all of it to written form,” she asks, as part twenty of the twenty-five part sequence “keep profane objects close, the argument,” “did they aspire / to scripture? A song of ‘I’ for loss, deadened by type, a song of ‘I’ for / legitimacy, deadened prior where few makers, many users glom on like / a fad, and a figure emerges without intending it only one might go on / to play the pro’s—told enough to be credible, a figure preserved in oil: / who knows, we might have been left behind.”

Los Angeles poet Deborah Meadows’s latest [see my review of her 2013 selected poems here] is the poetry title

Neo-bedrooms

(Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2021), an assemblage of lyric bursts, language riffs and meditations, composed through folding one line overtop another in sequence, akin to a suite of sequences assembled into book-length shape. “Nothing is given that condences down.” she writes, to open the poem “Hammer of Justice.” “Can we consider this defaced old-age couple a form of iconoclasm?” Her writing exists as a rush, propelled by cadence and carefully-placed words. As part of the prose sequence “Croud-prone,” she writes: “Funeral comes forth once. Heavy-laden steps, that uncanny shift from / time to not. Cloud’s perimeter somehow contained in front right here: / haloed filthy puddle. Clouds.” There are echoes in her work of the prose poems of Rosmarie Waldrop, although looser in her lyric, and without Waldrop’s specific complexities writing between a German structure and an English tongue; Meadows follows a delicate line up against instability and insecurity, writing on making, thinking and artistic production. “When field workers transferred all of it to written form,” she asks, as part twenty of the twenty-five part sequence “keep profane objects close, the argument,” “did they aspire / to scripture? A song of ‘I’ for loss, deadened by type, a song of ‘I’ for / legitimacy, deadened prior where few makers, many users glom on like / a fad, and a figure emerges without intending it only one might go on / to play the pro’s—told enough to be credible, a figure preserved in oil: / who knows, we might have been left behind.”

March 26, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Abby Hagler

Abby Hagler

lives in Chicago. Previous work has appeared in Entropy, FANZINE, Ghost Proposal, and Deluge among others.

There Was Nothing Left But Gold

was selected the winner of the 2020 Essay Press chapbook contest and appeared in summer 2021. With Julia Cohen, she runs Original Obsessions, an interview column at Tarpaulin Skymagazine about writers’ childhood obsessions manifesting in their current work.

Abby Hagler

lives in Chicago. Previous work has appeared in Entropy, FANZINE, Ghost Proposal, and Deluge among others.

There Was Nothing Left But Gold

was selected the winner of the 2020 Essay Press chapbook contest and appeared in summer 2021. With Julia Cohen, she runs Original Obsessions, an interview column at Tarpaulin Skymagazine about writers’ childhood obsessions manifesting in their current work. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I learned the value of traveling as research for writing. And of letting whatever happens on the trip be inspiration. There Was Nothing Left But Gold takes place on a road trip to experience the settings of ghost tales and folklore. However, that trip got totally waylaid by grief over losing the relationship with my mom. The essays that came out take place in a single location, an unintended stop. I didn’t come away with any material centered on what I was originally looking for. Once back home, that outcome felt okay about that after realizing I wanted to write into the reasons why I stopped driving instead. And I suppose that’s a little bit how deep-dives into research work. You find yourself somewhere totally different than where you began whether or not you physically end up elsewhere. It’s a necessary excess, something you just have to give yourself to. It is funny that I now know way too much about skunk bites and rabies, which is not in the chapbook. But, without that trip, I may not have read anything about hauntology or looked into Willa Cather as a person, which is the backbone of the writing itself.

2 - How did you come to essays first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

The material for this chapbook started out as prose poems three or four years ago. When they were finished, I just felt like there was more to say. There were conclusions they were reaching for that poetry might not reveal or solidify without the narrative arc an essay uses.

John Keene’s Annotations and Lyn Hejinian’s My Lifealso inspired me. All those lush, teeming sentences shooting off new ideas, reveling in descriptions, adding up to the arc of a personal evolution reminded me of what it feels like walking through grass. I was fortunate enough to read them back-to-back, and that’s when a sort of theory about sentences and grass first occurred to me. I was thinking about how poetic prose works, variating off of Susan Sontag’s notion of it from her essay “A Poet’s Prose.” For her, poet’s prose is elegiac and it discusses the journey of becoming a writer. For me, this means poetic prose can be resistant to nostalgia but also tender to past selves. It embraces the contradictions and complexities of an identity in its excess, its racing through line breaks. Poetic prose makes room for the simple fact that the story of an identity is not straightforward. Gertrude Stein talks about this too. A portrait can be composed of many details, emotions, and perspectives that are not in competition. And I see this as the way that grass, or even a protest, works as well.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It could take forever for me to realize a writing project is happening. Anything I write now has roots that go back ten or so years. There are lots of connections between the pieces I put away and pick up again, which is definitely my process.

The time it takes to finish an individual piece depends on how much material I have in notes and whether or not the structure of the piece is clear. I work at 9-5 job, so I’m a pretty slow writer in that it takes a month or probably more to get to what I would consider a first draft. I think I’ve only ever written one essay that came out in one sitting and was published with few changes. Beginning is easy as far as getting words on the page. The time-consuming part for me is finding what the piece is really talking about. Journaling helps with that. When I find what a piece is talking about, it’s much easier to organize. All that takes a while.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The beginning of an essay, to me, is often an ask: Tell me about… I think of it like an invitation to excavate textures and smells and colors. Capturing details within memories is important because everything but the feeling I was left with/ conclusion I reached fades so quickly. Maybe all this is a practice in improving my memory. Sometimes it’s just a small revelation coming from understanding why I do/ have done certain things that have altered my life or relationships in the past – the kind of therapy stuff I think about on walks. Broad topics are also generative: A favorite kind of light; why grass could be considered monster; a superstition to own up to; the most terrifying thing about water.

This chapbook began as lists of instances of gold and types of grass mentioned in Cather’s novels. Then I got to wondering what I have to say about the grassland where I grew up. And what gold means to me after all this collecting.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I was a very serious competitive speech (ahem, forensics) kid in high school, so I’m always okay with giving readings. Even back then I knew that there really is something electrifying about hearing someone read aloud. It’s different than reading aloud to myself, which I do often. To sit and listen to someone read their work gives me this energy toward writing. Recently I was a part of a reading where we discussed how the pandemic opened up really helpful new avenues for readings using web conferencing services. I’m interested to see how online readings and in-person readings are determined in the future because they both have strengths. Overall, no matter the form of the reading, it’s a particularly good experience when the content the readers choose feels curated, like they are all in conversation. I absolutely love when people read new works in progress. I perk up when a reader makes that introduction. Those have consistently been at the top of my most memorable readings list.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

A primary concern behind writing these essays was the notion of possession – especially as I realized I was writing about land as much as I was writing about kinship. I kept thinking: What narrative of return can I construct that isn’t centered on claim? Wrestling with (dis)possession became a way to see myself in relation to values rather than as someone who is helpless to them or unaware of them all together. Deciding to write a different kind of return narrative helped me to identify evolution of self within the text, which, for me, is its own narrative arc.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Every job I’ve ever worked has necessitated a writer. Most writing does not look like writing. Keeping logs, taking minutes, composing emails, organizing meetings, talking to people, creating to do lists, saving meeting notes. I’ve been a writer working at Wendy’s, in a homeless shelter, as an executive assistant, shelving books in a library, or even scrapbooking with my mom. Writing is the work of gathering, of finding an order for things. Sometimes it makes it on paper. I think a lot of people are writers and they don’t really know it – especially working people. Writing is more often than not something a person volunteers to do. But it happens everywhere. Someone has to be willing. I guess the job of a writer is to keep doing that work, to keep recording for the benefit of the group, to keep giving people new visions of reality to think about, to keep reminding people of what happened.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I don’t have a ton of experience with this but I have found it to be very positive. I’m always appreciative of anyone who has taken time with my work, and it’s really helpful to have conversations about what’s going on in a piece of writing. It always broadens my own writing and editing process.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Several years ago, when I was thinking about starting to write after a long hiatus, I asked a possibly unfair question to a friend, What do people need from me, as a writer, right now? She really surprised me by saying, People need the same things you need. They need to know how you healed. And I think that’s an interesting place to start from.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work in smaller chunks of time: Saturday mornings, for an hour after work, on a slightly extended lunch break, for 30 minutes before work when the coffee finally hits. It’s always this process of reading over the piece and then taking random notes as I mull it over while going about the day. Then I come back to the computer with my notes and keep writing. Editing takes hours, so it’s best to have at least one morning totally free to do that.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

My phone is full of random little notes taken on walks or while commuting that I can later scroll through. There’s always old work in dropbox. Carole Maso’s writing is something I consistently return to for immediate inspiration.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pennies. A storm brewing. Fermented foods at the deli counter in Polish corner groceries. Sweaty t-shirts. Dust in the air during a heatwave.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Performance art about relationships or work centered around everyday living is most influential to me. I have for years and years been a big fan of Miranda July’s many conceptions of togetherness through projects like Learning to Love You More or It Chooses You. I don’t think I want to do without owning Dario Robleto’s Alloy of Love. Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit and Acorn are treasures. I also like to read about artists who are living in performance spaces, depriving themselves of some form of interaction, making clothes, testing their bodies, or even testing the audience. There are also comedians doing great stuff like this such as .

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

For several years, I have read over and over “The Silver World” by Carole Maso, which, to my knowledge, is only published in an issue of Conjunctions. I keep that issue close by wherever I live. And also: It Is Daylight by Arda Collins, Anne Boyer, Roland Barthes, Anne Carson’s Plainwater, Mary Ruefle, old issues of Lucky Peach and Cabinet magazines, installation pieces at galleries or art museums, history podcasts, playing Criterion Collection roulette, random dissertations I find at the library, ghost tours.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have an idea for a novel. It will probably never make it to paper. I’ll just keep regaling friends with the story while on long hikes.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I like to think I would have tried my hand at becoming a reality dating show contestant.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing just makes a lot of sense to me and I would honestly be sad if I stopped. I’m a diaries person, I suppose. Writing essays or poetry is not my full-time job but it’s a necessity that I’ve learned to put on the priority list whether or not I’m making something intended for others to see.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Elizabeth Robinson’s On Ghosts

Rungano Nyoni’s I Am Not a Witch

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a full-length essay collection about working night shifts in a housing first project in the early 2000s.

March 25, 2022

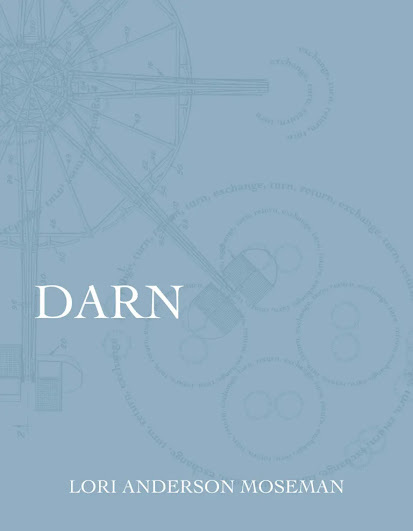

Lori Anderson Moseman, DARN

this boat wouldn’t survive the Kootenai before or after the Libby damn

this boat tries not to carry tremolite-actinolite from vermiculite mined

by Grace where Cobbler’s great granddaughter clerked

400 dead to date from asbestosis

this boat tries to contain neither the shotgun nor the story of suicide

nor the non-viable evidence that it was not murder

the Cobbler’s granddaughter gone

this boat contains whatnot and ecological thought all partial and mortal

oh lift us up up up to soar (“there’s a hole, dear lyre”)

I’m fascinated by American poet Lori Anderson Moseman’s assemblage of text and image, the poetry collection DARN (Delete press, 2021).

DARN

is composed as a gathering of sentences, phrases and images patched and stitched and sewn together into a kind of lyric quilt. There are elements here reminiscent of the work of Kemptville, Ontario poet Chris Turnbull, utilizing a blend of photograph and text, although Turnbull’s work is more of a 3-D whole that includes text, whereas Moseman works very much in the lyric mode, utilizing fragment and photograph, as well as text, as structural elements of her lyric framework. I am reminded, instead, of some of the visual stitchwork of Erín Moure, photographs of stitched pages, elements of Toronto poet Kate Siklosi’s visual poems, or even the collage-effects of the poems of Susan Howe, the image of one line layering atop another. Moseman’s work also includes echoes of Perth, Ontario Phil Hall’s work, attuned to the precision of the physical lyric and the physical object, offering a particular reverence, with each object and phrase resonating off each other. “if infinitesimal text,” she writes, as part of the opening section, “from ‘The Little Man from Nuremberg’ could each us tolerance //// perhaps we have the tools we need to house Syrians camped // in Jordan waiting for world powers to broker a temporary peace // not pictured an Egyptian Copt selling vintage santas on a seashore // flea market in California to earn money to help refugees in Lebanon [.]” She writes of world events and local gestures, the impact of each deeply felt upon the other. I like the way her lyric simultaneously leans into the memoir, the essay and threads of history, weaving multiple approaches together into a singular, quilted structure of deeply-felt, and deeply-considered, offerings:

I’m fascinated by American poet Lori Anderson Moseman’s assemblage of text and image, the poetry collection DARN (Delete press, 2021).

DARN

is composed as a gathering of sentences, phrases and images patched and stitched and sewn together into a kind of lyric quilt. There are elements here reminiscent of the work of Kemptville, Ontario poet Chris Turnbull, utilizing a blend of photograph and text, although Turnbull’s work is more of a 3-D whole that includes text, whereas Moseman works very much in the lyric mode, utilizing fragment and photograph, as well as text, as structural elements of her lyric framework. I am reminded, instead, of some of the visual stitchwork of Erín Moure, photographs of stitched pages, elements of Toronto poet Kate Siklosi’s visual poems, or even the collage-effects of the poems of Susan Howe, the image of one line layering atop another. Moseman’s work also includes echoes of Perth, Ontario Phil Hall’s work, attuned to the precision of the physical lyric and the physical object, offering a particular reverence, with each object and phrase resonating off each other. “if infinitesimal text,” she writes, as part of the opening section, “from ‘The Little Man from Nuremberg’ could each us tolerance //// perhaps we have the tools we need to house Syrians camped // in Jordan waiting for world powers to broker a temporary peace // not pictured an Egyptian Copt selling vintage santas on a seashore // flea market in California to earn money to help refugees in Lebanon [.]” She writes of world events and local gestures, the impact of each deeply felt upon the other. I like the way her lyric simultaneously leans into the memoir, the essay and threads of history, weaving multiple approaches together into a singular, quilted structure of deeply-felt, and deeply-considered, offerings: not pictured tattooed neighbor

slamming trashcan lids

“I survived the camps”

not pictured a friend

tribunal’s translator ushering

a shaking woman

out of the war crime courtroom

the yet-to-be regurgitated

rape rattling each bone

this is voice this is voice

not the tool that bore the holes

not the tool that smoothed the edge

not the thread beings spun

the need for payment

the thirst under adornment

The structure of the book is segmented into sections, the first of which, “DARN,” includes the extended structures “there’s a hole, dear lyre” and “there’s a glitch, dear orbit,” and “OH WELL,” made up of the extended sequence “shoot.” There is such a physicality to her lyric, one that weaves together sewing, text, photographs and legal text, archives and story-excerpts and even patents. “darners like pie tins like baskets carry great distances / buffer zone,” she writes, in a couplet that is set on the page to read two possible ways: “darners like pie tins like baskets / buffer zone / carry great distances.” The ebbs and flow of DARN simultaneously offer multiple ways of thinking, suggesting and being, and no answers, but an invitation to explore more than one perspective.

Although this is the first I’ve seen of her work, Moseman is the author of numerous titles including Cultivating Excess (The Eighth Mountain Press, 1992), Persona(Swank Books, 2003), Temporary Bunk (Swank Books, 2009), All Steel(Flim Forum Press, 2012), Flash Mob (Spuyten Duyvil, 2016), Light Each Pause (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017) and Y (The Operating System, 2019), as well as a collaboration with artist Karen Pava Randall, Full Quiver, from Propolis Press. I’m fascinated by the ways in which history, memoir, the archive and multiple other elements are folded into the lyric of DARN, incorporating into the larger structure, and even the larger narrative, of the book. Darn, she titles, playing off both the exclamation of frustration and the stitching together. Through her lyric quilt, Moseman offers a collection on what holds us, and what holds us together, and what might save, and even redeem, us yet.

March 24, 2022

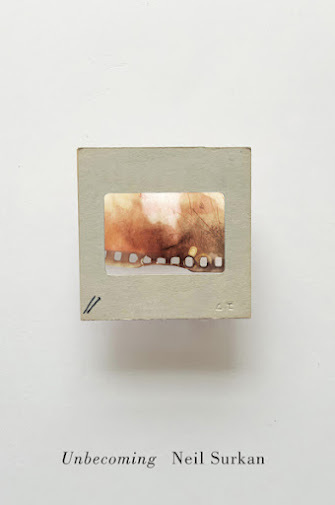

Neil Surkan, Unbecoming

INFINITIES

At this sharp

crook in Beaver Point

Road, a cumulus

of blackberries

frizzes with ripe fruit,

veined leaves. Cars slip

past like swallows

in the throat while

three wild horses

tug drupelets

off the spiny

boughs, their wire-

twisting plier lips

tenderly efficient.

On this crisp

July evening,

they’re completely

ignoring me. Looking

down, I suddenly notice

the grasses teeming

with baby toads.

The second full-length collection by Calgary poet Neil Surkan, after

On High

(Montreal QC: The Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018), is Unbecoming (The Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), a collection of delicately-carved portraits of attention, characters sketches and family stories, all held together by heart and hearth. Surkan articulates a sequence of restrained lyric bursts, composed as tightly-packed narratives that reveal spaces, scenes and recollections, and stories writing out all the words for silence. “Why are we taking these strands / of words so seriously?” his narrator is asked, at the offset of the poem “POETRY WORKSHOP / WITH MEDICAL STUDENTS,” writing a short scene of a seeming-difference of opinion between the workshop attendees and facilitator. The poem answers, ends, as the narrator/facilitator turns the question back: “Why are you so invested / in keeping us alive?” Through a poetics of attention, there is a curious way through which Surkan attempts to articulate the whys and ways we should care about such things, including lines of poetry, and the humans that surround us, utilizing a descriptive language that is as unusual as it is striking. “Third-generation firs,” he offers, to open the poem “GLOAMING IN A MONOFOREST,” “planted like barcodes, / repeat, scaly and bald / to their modest tops, where // smoky-green tufts sway. / The ground, needles and salal / around silo-wide stumps, // springs underfoot – or shrugs.”

The second full-length collection by Calgary poet Neil Surkan, after

On High

(Montreal QC: The Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018), is Unbecoming (The Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), a collection of delicately-carved portraits of attention, characters sketches and family stories, all held together by heart and hearth. Surkan articulates a sequence of restrained lyric bursts, composed as tightly-packed narratives that reveal spaces, scenes and recollections, and stories writing out all the words for silence. “Why are we taking these strands / of words so seriously?” his narrator is asked, at the offset of the poem “POETRY WORKSHOP / WITH MEDICAL STUDENTS,” writing a short scene of a seeming-difference of opinion between the workshop attendees and facilitator. The poem answers, ends, as the narrator/facilitator turns the question back: “Why are you so invested / in keeping us alive?” Through a poetics of attention, there is a curious way through which Surkan attempts to articulate the whys and ways we should care about such things, including lines of poetry, and the humans that surround us, utilizing a descriptive language that is as unusual as it is striking. “Third-generation firs,” he offers, to open the poem “GLOAMING IN A MONOFOREST,” “planted like barcodes, / repeat, scaly and bald / to their modest tops, where // smoky-green tufts sway. / The ground, needles and salal / around silo-wide stumps, // springs underfoot – or shrugs.”

March 23, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Helen Chau Bradley

Helen Chau Bradley

[photo credit: Surah Field-Green] is the author of Automatic Object Lessons (House House Press, 2020) and Personal Attention Roleplay (Metonymy Press, 2021). Their essays, stories, and reviews have appeared in carte blanche, Cosmonauts Avenue, Entropy Magazine, Maisonneuve Magazine, the Montreal Review of Books and elsewhere. They host the Strange Futures book club, which focuses on BIPOC speculative fiction, via Librairie Drawn & Quarterly.

Helen Chau Bradley

[photo credit: Surah Field-Green] is the author of Automatic Object Lessons (House House Press, 2020) and Personal Attention Roleplay (Metonymy Press, 2021). Their essays, stories, and reviews have appeared in carte blanche, Cosmonauts Avenue, Entropy Magazine, Maisonneuve Magazine, the Montreal Review of Books and elsewhere. They host the Strange Futures book club, which focuses on BIPOC speculative fiction, via Librairie Drawn & Quarterly. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Personal Attention Roleplay is my first book. Too early to say how its publication will affect my life, but the writing of it has been a revelation, in terms of finally taking my own writing seriously.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I did publish a poetry chapbook before this book of fiction, but fiction comes first for me, it’s the medium I feel most comfortable in, possibly because I read more fiction than anything else. I continue to be compelled by narrative structures (or un-structures) and by characters’ inner workings, I am always experimenting with how to pull those elements together into something like a whole.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes me forever to start a new writing project, whether it’s a story or a series of poems, or dare I say, a novel. I have to mull the thing over in my head for weeks, or months, or possibly years, before I can commit even the first word to paper (or screen). First drafts are more like fifth or tenth drafts, because I’ve thought about the piece’s shape for so long, so they do tend to predict the piece’s final shape fairly reliably. I’d like to write a story or a poem that changes shape completely, though. Seems like a worthwhile exercise.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Up until this point, I’ve never had the confidence to approach “writing a book” from the get-go. It’s been a slow accumulation of shorter pieces into some sort of final product that I never would have imagined from the beginning of writing. Now that I’ve published a chapbook and a book, however, I worry that I’ll start approaching projects as “books” and that that will somehow hinder my ability to write anything risky or interesting. The idea of “writing a book” makes me overly aware of an audience.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love reading in public. In a previous life, I was the lead singer in a band, and I haven’t lost that desire to perform. I also love hearing other writers read. Words spoken aloud ring differently than they do on the page.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

A concern I have is how to write characters whose material realities and backgrounds are deeply considered, without resorting to a tepid form of identity politics that I see being promoted a lot in reading and writing circles these days. As a writer of “hyphenated experience,” I do tend to write characters who have similar identity markers to me, but I never want my stories to be driven by identity alone, or to imply that because a person is, say, Asian and queer and nonbinary, that they would experience or view the world in the same way as any other Asian, queer, nonbinary person, or that they need to represent a specific identity “correctly.” I am deeply uninterested in didactic fiction-writing, or fiction-writing that is meant to “build acceptance” for certain groups of people. Otherwise, I am concerned with how to write queerness, and I don’t mean how to write queer characters, but more so how writing itself may be queer, in its structure. Gail Scott, for instance, is a helpful writer to me, as she has been thinking through and working with this question for years.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

As mentioned, I dislike didactic writing, writing that tells us what to do politically. I think that fiction writers, if we have any useful role at all, should be asking difficult questions, though. Puncturing the veneer of the status quo! Not in an edgy, shock-value kind of way, but in a way that illuminates power structures, emotional complexities, historical contexts, cultural dissonances. I think that asking questions is more important and more desirable in fiction, than answering them. I also think that humour is important in fiction-writing, that making people laugh or grimace, sometimes in self-recognition, might be an essential writing role: being a funhouse mirror?

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential! Once I feel I have a final draft of a piece, that I’ve gone as far with it as I can alone, I welcome collaboration with a thoughtful, incisive editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Being on the internet too much means wading through a constant maelstrom of conflicting advice about everything, so it’s hard to say. I’ve definitely heard people recommend reading dialogue out loud, so as to illuminate any excess or clichés, and I think that’s pretty solid advice.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to prose to reviews to songwriting)? What do you see as the appeal?

I enjoy moving between genres. If one form is feeling tired to me, it is energizing to turn to another form. I’ve been trying to work on a novel lately, and when it’s felt like drudgery to write prose, I’ve turned to a perfume-review-based poetry project that I devised as a distraction. Even reading in other genres helps—reading a lot of poetry has helped me shape my prose, to cut out what is superfluous, to make phrases sharper.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I am terrible at having a writing routine. My first book was written mainly when I was supposed to be doing something else (my day job). I am trying to figure out how to be a writer first, and a worker second, if that makes any sense, and a lot of the struggle has to do with discipline. I’m used to writing being a thing that I do to procrastinate on my actual responsibilities. If there is nothing I need to be doing except writing, how do I stop myself from turning away from that? When it’s the only thing left to be done, how to do it?

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Other writers and artists. I read a lot, and I watch a lot of movies and listen to a lot of music. I never want to be creating in a void. Other artists are the only people, usually unbeknownst to them, who can unstick me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I’ve gotten into perfume during the pandemic, as a way to subtly differentiate one day from another. I spilled a sample of Zoologist’s Tyrannosaurus Rex, which is this gargantuan scent filled with bright flowers, smoke, leather, and incense, all over my kitchen table a while ago, and now my apartment smells like the late Cretaceous, which is fitting since we are now in the middle of another massive extinction event.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music always makes its way into my writing. So does whatever I’m watching. So do the things I overhear on the bus. So do the things my friends say. Everything eventually makes its way in—look out!

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many. Renee Gladman, Gail Scott, Julio Cortázar, Yoko Tawada, Kiese Laymon, Hoa Nguyen, Jamaica Kincaid, Clarice Lispector, Silvina Ocampo, Qiu Miaojin are some favourite voices. I certainly wouldn’t claim to be able to write anything near any of them, but I keep them around, to help and challenge me. I also like to read gay smut (e.g. Straight To Hell), which is direct and filthy and keeps me honest.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Go to Hong Kong.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I actually love being a bookseller. I did it for five years and would have happily kept doing it forever, had it been financially viable.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I tried doing a lot of other things first, partly because I was too scared to write, even though I’d wanted to since I was a kid. So I guess it’s a deep compulsion, because finally, at 33 or so, I couldn’t stop myself anymore.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Minor Detail, by the Palestinian writer Adania Shibli (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette) is a book that marked me recently. Isabel Sandoval’s film Lingua Franca stuck with me, and made me search out all her other work.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am slowly and painstakingly learning Cantonese, my mom’s first language. It is a humbling experience. I’m also working on a novel and a series of poems.

March 22, 2022

some march break, picton;

We were in Picton for a few days. Did I mention that? We were in Picton for a few days, heading off down the 401 Highway west to visit with father-in-law and his wife for a few days. It was March Break, after all, and the young ladies required a change of scenery. Perhaps we did, also.

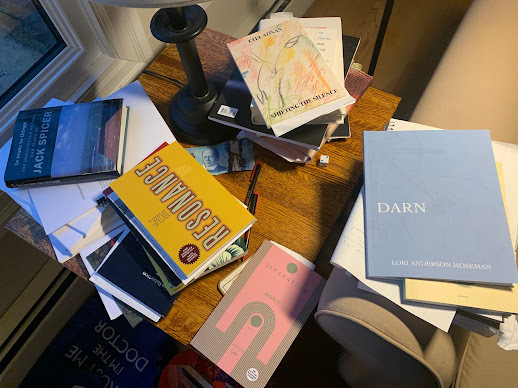

We were in Picton for a few days. Did I mention that? We were in Picton for a few days, heading off down the 401 Highway west to visit with father-in-law and his wife for a few days. It was March Break, after all, and the young ladies required a change of scenery. Perhaps we did, also.Christine on the couch for five days with her knitting, books. Myself on the other couch for five days with my books and manuscripts and notebook and chapbooks and so many other paper-mayhem. Admittedly, there were stretches where one day did bleed into the next, watching the mist stretch across the length of the river beyond father-in-law's backyard, as the young ladies fell from activity to activity. I think they saw alpacas at one point, and even did a shirt-painting event at the public library. Did they manage both parks, or just the one?

I finally finished the Stanley Tucci memoir while there. Christine gifted me the book for Christmas, and I read half on Christmas Day, and the rest during March Break. It's hard not to read such a book without feeling hungry, and wishing to try every recipe. It's hard not to read such a book without feeling so comforted through his tone that somehow, unbelievably, we're already friends. I should really go over. No, no. And apparently father-in-law gifted same for Christmas, and he did try one of the recipes: the martini. A lot of alcohol, he said. Do you think Stanley Tucci knows of the martini/martinus joke in the classic Wayne and Shuster "Julius Caesar sketch" that I regularly post every year on my birthday? Probably not. Perhaps I should write him a letter just to make sure.

I finally finished the Stanley Tucci memoir while there. Christine gifted me the book for Christmas, and I read half on Christmas Day, and the rest during March Break. It's hard not to read such a book without feeling hungry, and wishing to try every recipe. It's hard not to read such a book without feeling so comforted through his tone that somehow, unbelievably, we're already friends. I should really go over. No, no. And apparently father-in-law gifted same for Christmas, and he did try one of the recipes: the martini. A lot of alcohol, he said. Do you think Stanley Tucci knows of the martini/martinus joke in the classic Wayne and Shuster "Julius Caesar sketch" that I regularly post every year on my birthday? Probably not. Perhaps I should write him a letter just to make sure. I probably made initial notes on at least twenty-five or even thirty reviews while there, working through an array of books and chapbooks, including a few that I realized I didn't quite wish to review (this happens, for a variety of reasons, including "I don't feel as I have anything constructive to say," or even "I don't really care for this and don't wish to spend that much time with it" etc; reviews take a considerable amount of time and attention, after all, and it is mine to give). Going slowly through the new McClelland and Stewart poetry titles, the new Coach House Books poetry titles, the new House of Anansi poetry titles and a handful of plenty of other things (a Vehicule title, a University of Nebraska Press title, a McGill-Queen's title, a Delete Press title, an Omnidawn title, a Shearsman Books title, a Litmus Press title, etcetera). Of course, part of the push is just knowing how much there is still to come, and wishing to get some of these things dealt with before the rest lands. How much is enough? Curious to see, also, the new Anvil, Turnstone, Vehicule, Talonbooks, New Star, Invisible, etcetera.

I probably made initial notes on at least twenty-five or even thirty reviews while there, working through an array of books and chapbooks, including a few that I realized I didn't quite wish to review (this happens, for a variety of reasons, including "I don't feel as I have anything constructive to say," or even "I don't really care for this and don't wish to spend that much time with it" etc; reviews take a considerable amount of time and attention, after all, and it is mine to give). Going slowly through the new McClelland and Stewart poetry titles, the new Coach House Books poetry titles, the new House of Anansi poetry titles and a handful of plenty of other things (a Vehicule title, a University of Nebraska Press title, a McGill-Queen's title, a Delete Press title, an Omnidawn title, a Shearsman Books title, a Litmus Press title, etcetera). Of course, part of the push is just knowing how much there is still to come, and wishing to get some of these things dealt with before the rest lands. How much is enough? Curious to see, also, the new Anvil, Turnstone, Vehicule, Talonbooks, New Star, Invisible, etcetera.  With the young ladies, we played checkers, read stories and caught the new Pixar flick, also (it was delightful, honestly), watched via Disney+ on their downstairs couch. Good to see parts of Toronto, including Skydome and the CN Tower. Did you know my eldest daughter attended the same high school in Ottawa's west end as did ? Very different years, obviously. Apparently Gary Barwin attended there, as well. Rose and I finished reading the second Harry Potter novel, also (she's really been into those lately; we haven't the heart to tell her the author is a terrible person). We finished book two, which allowed the opportunity to then see the film. I established the rule that we can't see one of the Potter flicks until we're finished the book. We caught the film Sunday night, soon after home. She's already eager for book three.

With the young ladies, we played checkers, read stories and caught the new Pixar flick, also (it was delightful, honestly), watched via Disney+ on their downstairs couch. Good to see parts of Toronto, including Skydome and the CN Tower. Did you know my eldest daughter attended the same high school in Ottawa's west end as did ? Very different years, obviously. Apparently Gary Barwin attended there, as well. Rose and I finished reading the second Harry Potter novel, also (she's really been into those lately; we haven't the heart to tell her the author is a terrible person). We finished book two, which allowed the opportunity to then see the film. I established the rule that we can't see one of the Potter flicks until we're finished the book. We caught the film Sunday night, soon after home. She's already eager for book three.

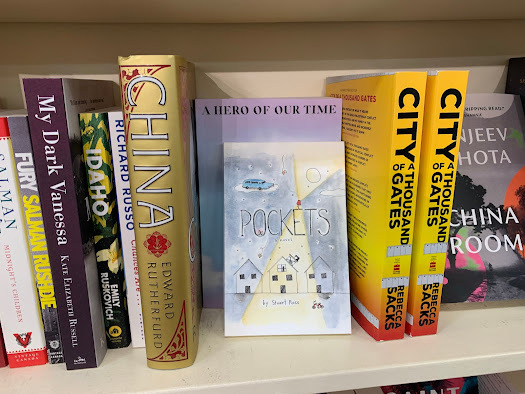

One one of our last afternoons, father-in-law and his wife tossed us out for a "date afternoon," with a birthday-related gift card to Gillingham Brewing Company, which we liked well enough (I think I preferred the prior visit's jaunt, over to Parson's). Christine had the oysters, naturally. I had some drinks, and even brought a handful of them home. We hit the bookstore en route, as one does. It was good to see the display of Invisible Publishing titles, and then realize there were associated displays, including Snare Books and our own Chaudiere Books (both of which Invisible had acquired, at various points). Our books are still in stores! Very nice. Every time I walked by any books by Zoe Whittall, it would fall from the shelf and land loudly upon the floor, which prompted me to wonder how Zoe might have rigged up such a thing. And, I thought, whomever put Stuart Ross' book to this position in the bookstore in Picton, offering a particular kind of banner above, "I approve of your messaging" [I have since discovered that this was Cameron Anstee, but a day prior to our discovery]. I picked up a couple of things, including a Sheila Heti title, and the latest by Kim Thúy. I also excitedly picked up a book for the wee children, excitedly offering it to Aoife, only for her to respond: "We already have that." Dammit.

One one of our last afternoons, father-in-law and his wife tossed us out for a "date afternoon," with a birthday-related gift card to Gillingham Brewing Company, which we liked well enough (I think I preferred the prior visit's jaunt, over to Parson's). Christine had the oysters, naturally. I had some drinks, and even brought a handful of them home. We hit the bookstore en route, as one does. It was good to see the display of Invisible Publishing titles, and then realize there were associated displays, including Snare Books and our own Chaudiere Books (both of which Invisible had acquired, at various points). Our books are still in stores! Very nice. Every time I walked by any books by Zoe Whittall, it would fall from the shelf and land loudly upon the floor, which prompted me to wonder how Zoe might have rigged up such a thing. And, I thought, whomever put Stuart Ross' book to this position in the bookstore in Picton, offering a particular kind of banner above, "I approve of your messaging" [I have since discovered that this was Cameron Anstee, but a day prior to our discovery]. I picked up a couple of things, including a Sheila Heti title, and the latest by Kim Thúy. I also excitedly picked up a book for the wee children, excitedly offering it to Aoife, only for her to respond: "We already have that." Dammit. What else? Not much, honestly. Five days of being able to breathe just a bit; that was nice (and our hosts are quite good cooks, also, with very good taste in wine, I might add). And the kids ran around in different surroundings, with different folk (they even had tea and separate park play-date with neighbour's fully-vaccinated five-year-old granddaughter). And then we returned home, all looking forward to landing back in our own space, and back into our routines. Hopefully a wee bit refreshed.

What else? Not much, honestly. Five days of being able to breathe just a bit; that was nice (and our hosts are quite good cooks, also, with very good taste in wine, I might add). And the kids ran around in different surroundings, with different folk (they even had tea and separate park play-date with neighbour's fully-vaccinated five-year-old granddaughter). And then we returned home, all looking forward to landing back in our own space, and back into our routines. Hopefully a wee bit refreshed.March 21, 2022

Laurie D. Graham, Fast Commute

I don’t want to write it. I know the scene as home:

the oil refineries rising from poplars

overlooking the river, the tank farms downstream,

the offgassing from stacks painted like candy canes,

the manufactured cloud formations—

they treat these flames as eternal, eschewing the clean

for the cheap and the quick. I don’t want this

tied to the trees or spoken aloud, this

inheritance, our confluence, our shame,

the windows of the houses on the opposite bank

observing the transfers, the neighbourhood park

that used to be the dump, and the quiet

of the river through each process, the banks

dropping away slowly, the river so large and old

it’s thought both impervious and already dead,

but instead it’s eroding the ground, and for good reason.

Toronto poet and editor Laurie D. Graham’s third full-length poetry title, after

Rove

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2013) and

Settler Education

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2016), is

Fast Commute

(McClelland and Stewart, 2022). Much like Toronto poet Phoebe Wang’s simultaneously-published Waking Occupations (McClelland and Stewart, 2022), Fast Commute attempts to come to terms with our colonial past and present, viewed through an ecological lens—two elements clearly intertwined and impossible to separate—something her work has been engaged with for some time. “Cities joined,” she writes, early on in the collection, “though separated by rivers, / cities twinned by growth, tension nested in the hyphen [.]” Set as a long poem through short, collaged sections, introduced by a self-contained opening salvo, there are structural echoes of Don McKay’s infamous Long Sault (London ON: Applegarth Follies, 1975) through her narrative layerings, historical asides and attentions to landscape. “Knowledge of home in danger of becoming academic.” she offers. “An empty can of energy drink under a sugar maple. / A black squirrel crossing critical thresholds: // roadwall, greenstrip, chainlink, trail, wooden fence, property.” She writes on refineries and tearing resources from the eroding landscape, citing settler histories and occupation, and the ways in which these opposing thoughts can’t help but find conflict.

Toronto poet and editor Laurie D. Graham’s third full-length poetry title, after

Rove

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2013) and

Settler Education

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2016), is

Fast Commute

(McClelland and Stewart, 2022). Much like Toronto poet Phoebe Wang’s simultaneously-published Waking Occupations (McClelland and Stewart, 2022), Fast Commute attempts to come to terms with our colonial past and present, viewed through an ecological lens—two elements clearly intertwined and impossible to separate—something her work has been engaged with for some time. “Cities joined,” she writes, early on in the collection, “though separated by rivers, / cities twinned by growth, tension nested in the hyphen [.]” Set as a long poem through short, collaged sections, introduced by a self-contained opening salvo, there are structural echoes of Don McKay’s infamous Long Sault (London ON: Applegarth Follies, 1975) through her narrative layerings, historical asides and attentions to landscape. “Knowledge of home in danger of becoming academic.” she offers. “An empty can of energy drink under a sugar maple. / A black squirrel crossing critical thresholds: // roadwall, greenstrip, chainlink, trail, wooden fence, property.” She writes on refineries and tearing resources from the eroding landscape, citing settler histories and occupation, and the ways in which these opposing thoughts can’t help but find conflict. Refinery giving way to ravine, giving way to

river. The refinery’s chainlink lining one side of the trail.

Dragonfly hovering, the bank

receding, their chainlink in danger.

The smell of thistle, the sweetness of an open field under sun.

Sky and ground, half and half.

The roses, the raspberries, the human

scale. The massive rumble always there.

As you near the road,

you must turn toward it.

Her meditations move through homesteading and settler culture, including around her Ukrainian forebears landing in the prairie sod, pulling up the earth for the sake of establishing roots. Writing of roots simultaneously broken and established, she cites the forest’s edge against the encroaching machinery. “The extractive machinery scrapes away / a wide, wide swath, an industrial-yard welcome. / Buildings poke out of the curved horizon, / appear as one in the distance, / a tasteful sci-fi dread. / After a feeling of bush and home, / recalling the warmth as a child / of lights in the dark in the distance, / of the city appearing.” She writes of depictions, and of names, histories and contexts ignored, for the sake of colonialism. “Dufferin, Simcoe, Dundas, King, Queen, Victoria, so I never know / where I am and could be anywhere and this is heritage,” she writes. While offering no conclusions, Graham’s Fast Commute focuses on acknowledging and articulating the length and breath of losses, breaks and potential losses still to come, and how much she herself emerged along a particular path of colonial thinking through her own genealogical trail, working to challenge her own thinking as she attempts to move forward. As she writes:

Manitou Asinîy in the Royal Alberta Museum,

which we crawled all over on field trips.

They renamed it Iron Creek meteorite, obscured its meaning,

Manitou Asinîy powerful and not to be touched,

and what did we do by touching it

March 20, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Elise Marcella Godfrey

Elise Marcella Godfrey’spoetry has appeared in literary journals such as subTerrain, Room, Prism, and Grain. She now lives with her family on the traditional and unceded land of the QayQayt First Nation.

Elise Marcella Godfrey’spoetry has appeared in literary journals such as subTerrain, Room, Prism, and Grain. She now lives with her family on the traditional and unceded land of the QayQayt First Nation. How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

This is my first book. I could say that it may have saved my life, in that working on it led me to discover that I had a piece of pitchblende in my possession. But the book itself hasn’t actually been published yet.

How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry in childhood, or maybe even in infancy, through lullabies and nursery rhymes. I have always loved song lyrics and stories told in verse.

How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

This particular writing project took a long time. A lot of thought. False starts. Research. Copious notes. Some poems came as impulses, and arrived relatively complete, and they are probably the strongest.

Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem could begin anywhere. Usually an image or a flash of insight. Or a phrase.

Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

It has been so long since I have read in public, I am not sure that I am able to answer this question. The last time I read from this work in public, when it was very much in progress, I lost all composure, burst into tears, and had to leave. So I need to be careful about which pieces I read, and when, and where, and to whom.

Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My concerns are more practical than theoretical, in my opinion. Climate anxiety, climate grief. Nuclear anxiety, nuclear grief. There are questions that I feel compelled to ask, but I am not sure that I am able to answer them. I think the biggest question is how do we address the necessity of reconciliation in a nation that continues to obfuscate and deny its own genocidal history? How do we reconcile when we continue to tacitly condone police brutality against Indigenous land defenders? Thinking of Fairy Creek. Thinking of CGL and TMX. How do we survive when we continue to cling to land that we clearly do not know how to care for? Speaking as a settler. Thinking of wildfires and how chronic mismanagement by a settler-colonial government has contributed to the worsening of fire season, in tandem with accelerating climate change. I could go on.

What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t know. I think perhaps certain people are more perceptive or insightful than others, or at least more interested in articulating those perceptions or insights in language. Writing can be a mirror. It can make connections and illuminate patterns. It can also open up inner worlds. Any other form of creative expression could also do this but words come more easily to some than to others.

Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

For this book, it was essential. Without Randy, the book would not be a book. Without Randy, the book would still be a file buried on an external hard drive.

What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Stay in your own lane, which is something I did not do in writing this book, but sometimes things fly off of other people’s vehicles and into our lanes, or through our windshields, like the piece of pitchblende I found in my possession. Sometimes other people’s business becomes our own when it begins to affect us directly. To be clear, this piece of pitchblende did not actually arrive through a windshield. To conclude, I’m not big on advice, as I have been given a fair bit of bad (or at least inapplicable) advice over the years.

What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My life has been ruled by the element of chaos since March 2020, as I have been home with my twin preschoolers. They start kindergarten next week [September 2021], so maybe I’ll figure out a routine soon. My day always starts with tea and news. I need caffeine and I need to know what’s happening.

When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I abandon writing regularly. I go outside. I go for walks. I talk to animals. I photograph other people’s flowers. I collect seeds in back alleys. My writing has mostly been stalled though as the demands of caregiving have eclipsed any desire I might have to articulate myself.

What fragrance reminds you of home?

Seaweed and woodsmoke.

David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Patterns in nature, sounds, concepts. Anything could be an influence.

What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My mind goes blank whenever I am asked these kinds of questions. The top shelf in my office is currently occupied by Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Anne Waldman’s Fast Speaking Woman, and Anne Carson’s fragments of Sappho, If not, Winter.

What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Grow a giant pumpkin.

If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I used to want to study languages and maybe work as a translator. Or a spy.

What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I do other things. I mostly do other things, other than write. My life is also not over yet.

What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I am reading A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghriofa and it is great. Film? I haven’t watched a film, as such, in a while, sadly. I’ve watched some pretty great music videos and TV shows. I just don’t get the stretches of time required for a film.

What are you currently working on?

Staying alive. Fighting a minor rhinovirus. Harvesting sunflower seeds before the lactating squirrel consumes them all.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 19, 2022

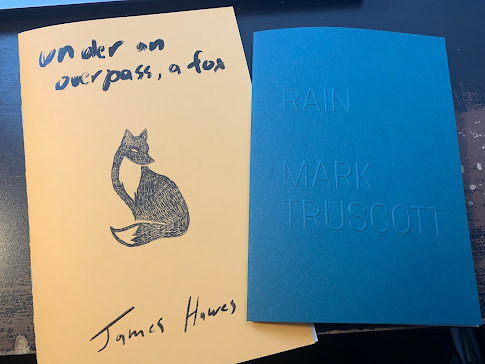

Ongoing notes: mid-March 2022: James Hawes + Mark Truscott,

Is it spring yet? Soon enough, I suppose. I think by the time you are reading this we are in Picton with father-in-law, but who is to say, from here, a week prior. What are days?

Is it spring yet? Soon enough, I suppose. I think by the time you are reading this we are in Picton with father-in-law, but who is to say, from here, a week prior. What are days? Montreal QC: Published as part of his new chapbook press Turret House is Montreal poet James Hawes’ latest, under an overpass, a fox (2022), a meditative sequence composed as homage to his friend and mentor, the late and legendary Montreal poet Peter Van Toorn. As the short sequence opens: “It’s nighttime and I’m awake thinking / about my friend. Outside is autumn / under streetlights in orange and pale / yellow and the fury of squirrels. And / the moon. The hum of cars in the air / in the distance. Something drips in / the kitchen. My friend is in a box / somewhere, his body burned away. I / start to feel cold in my chair.” There is an element to Hawes’ work—through the full-length collection and two chapbooks I’ve seen—that present the impression of the finely-tuned quick take, writing around a subject to attempt to catch from multiple sides, whether writing the hotdog through the chapbook-length sequence via his above/ground press title, or writing out grief around a friend’s death, set around the core of a particular memory. Hawes’ combination of pause and rush, pause and break are interesting, and in certain ways, this collection could have been longer.

And then a fox. He is a fox.

Toronto ON: The gracefully-produced three-poem chapbook RAIN(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book, 2022) furthers Toronto poet Mark Truscott’s deep engagement with the condensed lyric (across, to date, three full-length collections and a couple of chapbooks), although more straightforwardly-lyric than some of his prior works, which echoed structures akin to the work of Cameron Anstee, Marilyn Irwin, the late Nelson Ball or certain pieces by Michael e. Casteels, jwcurry, Stuart Ross and Gary Barwin, etcetera. There is something curious about the thickness of his lines and phrases. “If a pattern settles into / freshly relevant contours,” he writes, to open the poem “LEAVES,” “think / breeze perhaps, though the world / may be opening there too (by / way of changes shaped solely / within). And where are you?” He composes three poems each less than two dozen lines long, but from a writing history made up of poems short enough that eight or ten of his prior pieces combined might only achieve the same word count as a single piece here. He writes on physical features of leaves, rain and water, each poem akin to a single, experienced moment, slowed-down and stretched. “The chaos of rain / is the desperation / of a crowd hemmed in.” he writes, to open the third and final poem in the collection, which also happens to be the title poem. “We can watch it / through the window. / I’ve seen it / on the front page.” The shutter clicks, one might say, and there it is. How to write deeply on something so thoughtfully, strikingly condensed?

March 18, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Carol Harvey Steski

Carol Harvey Steski’s

debut poetry collection is

rump + flank

(NeWest Press, 2021). Her poems have appeared in Another Dysfunctional Cancer Poem Anthology and literary magazines including CAROUSEL, FreeFall, Room, untethered, Prairie Fire and Contemporary Verse 2. She won first place in FreeFall’s 2019 poetry contest and was nominated for The Pushcart Prize. Her work has also been featured in Winnipeg Transit’s Poetry in Motion initiative.

Carol Harvey Steski’s

debut poetry collection is

rump + flank

(NeWest Press, 2021). Her poems have appeared in Another Dysfunctional Cancer Poem Anthology and literary magazines including CAROUSEL, FreeFall, Room, untethered, Prairie Fire and Contemporary Verse 2. She won first place in FreeFall’s 2019 poetry contest and was nominated for The Pushcart Prize. Her work has also been featured in Winnipeg Transit’s Poetry in Motion initiative. Harvey Steski grew up in Treaty 1 Territory (Winnipeg). She now lives in Tkaronto (Toronto) with her husband and daughter and works in corporate communications. Visit her website: carolharveysteski.com. Connect with her on Twitter: @charveysteski, Instagram: @carolharveysteskiand Facebook: carol.harveysteski

For starters, it’s totally surreal. I began writing poetry a long time ago and took a several-year break while I was dealing with medical challenges (and triumphs – I also had my daughter during that time). Eventually I returned to writing in what I call my “second act.” So having this book published has made me trust that good things can happen when one sticks with a dream. I am very grateful to NeWest Press for giving me this shot. I’m still in shock, to be honest.

The publishing and marketing process have required me to deeply examine every aspect of the book and myself as a writer, the recurring themes in my work, my overall approach to poetry: what am I trying to say?

I became turned on to poetry while immersed in a post-secondary communications program in Winnipeg, with (the legend!) Patrick Friesen as my creative writing instructor and later, mentor. Patrick introduced us to Lorna Crozier and The Garden Going On Without Us was so important to me. Her “Sex Lives of Vegetables,” poems blew my mind with their bold sexuality, absurdity and sense of play.

At the exact time this tantalizing new creative world was opening, my real world fell apart when I was diagnosed with melanoma. Facing mortality as a young adult was terrifying. I feel strongly that the universe brought poetry into my life at the exact right time – to hold my hand and guide me through the dark. I chose to write a poetry manuscript for my major project and was determined to use my cancer diagnosis as a catalyst to creating art, not purely for cathartic therapy (though that’s totally legit – I just wanted to move beyond that singular purpose). The first poem I submitted to a literary magazine, Contemporary Verse 2, was accepted, so I thought I might be onto something.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A few of the poems in my new collection were written in the 90s, so it’s fair to say my process is pretty slow. But I’ve come to realize, and trust, that there is a natural cadence to my creative cycle. Writing poetry while immersed in a deep emotional or health struggle is almost impossible for me. During those periods, I need sufficient distance and time for productive brooding. I keep plenty of notes, mostly on my phone these days, snippets of ideas, dreams, phrases, objects I think are interesting. I move at my own pace, trying to manage and balance all the other priorities in my life as required, and remain open for when my inner voice eventually whispers, “ok I’m ready, let’s go.”

Once the actual writing starts, drafts happens both ways for me – a first draft can be fairly close-to-final with some tinkering, while others take much more time and persistence. I know a poem is finished when it plays over and over in my head on a loop, even waking me up in the night. Which is weird, but I love it.

years ago, but the majority were produced in my “second act.” I was just getting back into writing poetry, like learning to walk again, so the collection is a curation of what I deemed to be my strongest pieces. Fortunately, the common themes and connections between poems happened organically. For my next project, while I hesitate to set a rigid singlular theme at the outset – as that sense of constraint can sometimes come through – the publishing process for rump + flank has shown me that I could probably benefit from having a more defined thematic strategy up front.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

When I was young and fearless, I loved doing readings. The pandemic has unfortunately triggered some extra social anxieties in me (this is happening to everyone, right??) so I’ve had to work through those demons to prepare for public readings. Events are still virtual right now, which helps. I do have great respect for an audience and so I write with performance in mind, having an emphasis on rhythm and vivid imagery that will translate across a room (or the screen, now).

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t think I’m trying to answer questions so much as provoke, raise more questions. I have so many questions! In kindergarten, I wasn’t keen on going to school so one day my mom took me to visit the vice principal and talk it out with him. He told her that I kept answering all his questions with questions. So apparently I have zero answers – only questions!

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer has many roles and it’s completely up to the individual to decide – for some, the role is to report, broaden horizons, influence change. For others, to stir emotions, convey humanity, create connections or purely to entertain, provide an escape. Or any combination.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It can be extremely helpful to me as I work in a self-induced vacuum. Editors can see big-picture trends and themes when I’m stuck in the weeds. At the ground level, they can smoke out elements that aren’t working effectively in individual poems, as well as highlight style inconsistencies. I was privileged to have Douglas Barbour as my editor for rump + flank. Very sadly, he passed away in late September and I’m so very grateful to Doug for his expert eye and guidance. But it’s his positivity and kindness I will remember the most. He supplied me with a steady dose of confidence. And he believed strongly in the author’s final say, which was wildly empowering.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Patrick Friesen drove home the vital importance of rhythm in a poem and that reading aloud during the writing process is essential: the poet’s ear must be satisfied before a poem should be considered finished. This excellent advice has been baked into my own process.

And, from Plath: “I must be true to my weirdnesses.” This resonates hard with my own weirdo nature, haha.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

The pandemic threw me into a creative tailspin but in the Before Times, a writing period would require great swaths of dedicated time alone. The day would begin with a fun latte, extra-caffeine. And end with scotch. No talking, except to read my work out loud (singing is allowed). Music is essential.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Using a different part of the brain than where words live can be extremely helpful. My career in corporate communications involves lots of writing and editing, so I’m manipulating language constantly (and often “corporate-speak,” to boot). Periodically allowing a non-verbal creative force to take over and give my verbal brain a break has worked wonders. Several years ago, I enrolled in guitar lessons and tinkered with oil painting, and it was probably my most productive period. And sometimes I just need to take a cold break and trust the process.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Slow-rendering duck fat. Yum!

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Honestly, all of the above. Many are reflected in my poems: clouds, frogs, shark’s teeth, mosquitoes, cherries, decaying fish, the process of cooking and rendering, states of matter, disease and medicine, design typefaces, van gogh, and much more. I’m constantly dissecting the world around me trying to figure out how things work and what attracts me. Everything influences me. Music is a huge force and great lyrics, in particular, fuel me. Also lyricists: John K. Samson is a national treasure.

In my early writing years, Lorna Crozier was enormously important. Also, Sylvia Plath (“Suicide Off Egg Rock” is imprinted on me), Dylan Thomas, Seamus Heaney, Maya Angelou, Patrick Friesen, P. K. Page, Carol Shields, Michael Ondaatje, Karen Connelly, Di Brandt and Catherine Hunter. Years later, in my “second act,” Karen Solie’s Short Haul Engine resonated strongly for me, as did the work of Priscila Uppal, Sharon Olds, Paul Vermeersch, Catherine Graham and Sara Peters. Right now, there are so many talented voices, I’m constantly blown away and just trying to keep up!

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Properly learn guitar and write a song.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was always drawn to languages and drama, so having a career in communications (and my poetry side hustle) makes sense.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

My attention span, which was dysfunctional to begin with, has been completely shattered during this pandemic so reading for pleasure has been nearly impossible. The last full book I read was my own (the manuscript and design proofs) and, like, 100 times. The last great film I saw was Casablancacuddled up with our daughter. Nothing like watching a war movie during a global pandemic lockdown to remind you of the much-greater sacrifices other generations have made for the common good.

19 - What are you currently working on?

In this past year and a half, I’ve poured all of my energy into family, my hectic job and preparing for the production of rump + flank so I’m very hopeful to be able to start a new creative phase soon. I have a number of poems in various stages which hopefully will form a next collection. There’s still a strong element of body in these new poems, but I’ve also begun to explore the body’s connection to place.