Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 135

February 15, 2022

Spotlight series #70 : Bahar Orang

The seventieth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto writer Bahar Orang.

The seventieth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto writer Bahar Orang.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan and Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall.

The whole series can be found online here.

February 14, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with James Scoles

James Scoles

is the author of

The Trailer

. He holds degrees from Arizona State, North Dakota & Southern Illinois Universities & he has lived, traveled & worked in over 90 countries. His poem “The Trailer” won the 2013 CBC PoetryPrize & his short stories are featured in

Coming Attractions 13

(Oberon Press) & his writing has been nominated for The Journey Prize, the Pushcart Prize & both the Western & National Magazine Awards. He lives in Winnipeg, where he teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Winnipeg & also helps run a small, 120-year-old family farm.

James Scoles

is the author of

The Trailer

. He holds degrees from Arizona State, North Dakota & Southern Illinois Universities & he has lived, traveled & worked in over 90 countries. His poem “The Trailer” won the 2013 CBC PoetryPrize & his short stories are featured in

Coming Attractions 13

(Oberon Press) & his writing has been nominated for The Journey Prize, the Pushcart Prize & both the Western & National Magazine Awards. He lives in Winnipeg, where he teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Winnipeg & also helps run a small, 120-year-old family farm. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

If you write, any publication changes your life a little bit & my first book was a beautiful little chapbook (Coming Attractions 13, Oberon Press) featuring my short stories & it was exhilarating & unbelievably satisfying. Several publishers were interested in my story manuscripts but Coming Attractions series (and Fiddlehead) editor Mark Anthony Jarman had rejected enough of my work over the years to have confidence in me, strangely enough. Publishers were also interested in rejecting my poetry over the years, but my first full-length poetry collection—The Trailer—was submitted, accepted & published within a year & surprised the hell out of me. Immediately, it put me on a stage I’d only dreamed of being on. It was disheartening not to be able to launch in-person & tour The Trailer, but it still feels magical to see a dream come true.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I fell in love with language & poetry at an early age & have never lost that love. I was encouraged by my mother, who read to me from the womb onward. She read voraciously all her life & a huge variety of books. She bought me books that opened my mind to that creative world of words & imagination. I’ve always felt that poetry is the most efficient, intimate road between writer & reader, words & wonder, sound & the page.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Not that I’m any good at it, but at this stage I can write at will, when I need to, under deadline, etc. & when it comes to poetry & fiction & memoir, each beautiful idea can fly or fester off the hop. I can sit down & start & finish a poem or story in a single sitting & I can also find myself ‘wallowing in complexity’ for a while, drafting, starting and stopping, seeking the right voice or tense. I have whole shelves full of chapters, drafts of novels in one tense, another with the tense & voice altered; poems on one page in free verse while on the opposing page I’m trying to force it into a sonnet, etc. Over the course of my life I have had many ‘inner-mad-scientists’ that love the craft & writing & playing with words so much that the end-product isn’t the aim—it’s about the journey, not arriving. That said, if you want to make a living or 'part of your living’ (as I like to think of things), you need to focus. Sue Goyette talks about being able to ‘start at the seventh draft’ & that’s what I try to aim for, even if some pieces are perfect first drafts on a bar napkin or take years to make their public appearances.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My writing process varies between projects & because I tend to write for myself first & foremost, my projects have a personal connection & importance, so I take the work very seriously—like a job that needs to be done. With poems I’m seldom thinking ‘book’ as I write them, except a little more so now that I have a book out there.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I tell my students & truly believe that reading poetry aloud changes the world. With that sort of pressure I love doing readings & wish there were more opportunities.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

When I write, I’m always just trying to write, to get it down, do the work & understand something about the world in me & around me or tell a story, express some emotion & try to not consider my creative work in a theoretical way.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer’s role is to explore the important questions in our world, those to do with our climate & environment, human rights & identity, race, family & relationships & we have a responsibility as communicators to consider those questions as we try to entertain, inform & persuade in our creative work. In this world where people can instantly ‘publish’ their words to a worldwide audience we must be held constantly accountable for the ideas we share.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

With the amount of rejection I’ve had, I could say my work with editors over the years has been absolutely disastrous. But I’ve been blessed to have had only wonderful experiences with the editors I’ve been given the opportunity to work with & I just had an incredible experience working with Clarise Foster (The Trailer would not be The Trailer without her).

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I taught creative writing for a short time in a women’s prison in Arizona & the university was hosting Adrienne Rich for a reading & lecture & we invited her to come to the prison & she actually agreed to visit my class. As the two of us were walking through the yard, I decided to ask a master for advice. I told her that I had no problem writing lots every day, just a hard time revising my work & she grabbed my arm & pulled me in close & looked me in the eye & said: You have to revise. Revise. Revise. Revise. That’s where the art is in writing: revision.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s easy for me to move between genres, especially when I change my special hats that I wear: my fiction-hat is an Irish flat cap & of course the poet-cap is a jaunty beat-up beret. Actually, I tend to focus on one genre in a writing session. It might be poetry in a morning session, then work on a short story or novel in the afternoon, or vice versa. I’ve always challenged myself to work on & explore different forms & genres (my non-fiction-cap is a crooked old Captain’s hat). The appeal is the range of speakers, voices, characters, narratives, soundscapes & settings (among so many more literary elements) you get to play with when you blend writing with feeling, imagination & action.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Early morning sessions work best for me, when the world is mostly asleep & there’s a deeper silence to the day. Cinnamon coffee & focus: pen on paper, even if it begins with a to-do list for the day (that always includes writing time). Then I dive into whatever project is on that list until I can at least partly check that off. That moment satisfies my deep desire to create & satisfies it early. To be able to keep listing & checking that ‘writing time’ off as much as possible throughout the mornings, days, weeks & months is the aim & I’ve worked hard to cultivate a worth ethic that I can adapt to different settings & times of day, depending upon the deadline or the project. Sometimes, if I’m miraculously-able to have a short nap, I can ‘trick’ myself into believing I’m into another ‘morning’ session & have a really good burst. The process can be fun, at times, but it’s 95% work the rest of the time for me. As one ‘successful’ writer told me once: Making a living as a writer isn’t all fields of daffodils & daisies & sunshine once you get there. Always lingering is that dark, spider-filled shit-house without any paper.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Outside of a good, long sit in a spider-filled shit-house, usually a long walk will snap me back. I also know I can always return to my teachers—the great writers on my bookshelves that I look up to & still learn from. I can take down a collection or novel or biography & open in up & read & get inspired & be reminded that everyone fights their fight. My mother also painted me some simple little sayings on boards that line my book shelves & desk & remind me to: Dare to dream! Keep Focused! Stay Strong! Never Give Up! & Believe!

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Childhood home: Old Spice, Chanel No. 5 & fresh muffins, baby! Old family cottage: crackling fires, wet bathing suits, du Maurier cigarettes, Old Vienna beer, sawdust & the acrid smell of someone ‘getting a perm.'

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, for sure, especially whatever I’m listening to as I write—I’ll often loop a song or put a certain album on repeat. I sometimes have a sort of soundtrack playing in my head as I write; especially with fiction, for some reason. I’m also a huge fan of silence & nature & natural soundscapes—early mornings, my cabin on our old family farm, long walks under the elms & in the back alleys of Winnipeg.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I have a deep respect & admiration for a lot of Irish & Northern Irish writers & poets—from Patrick Kavanagh to Yeats, Heaney to Wilde, Joyce to Behan, Longley to Muldoon & poet-fighters like Bobby Sands. People who have persevered, writers that made me want to write in the first place, who lived ‘full’ lives, stood up for what they believed in & never stopped dancing with their dreams.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

In no special order: travel two continents I haven’t been to (Antarctica & South America), publish a travel memoir, short story collection & novel (then repeat); become the eleventh poet in space; find lots more dimes.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

As a writer, I love teaching writing & literature, but having worked at various occupations & attempted (not-so-admirably) others, it’s a clear toss-up between five: carpenter, cosmonaut, dime-finder, professional golf caddy & dentist. I love working with wood & the idea of letting ten poets forge a path into space before me (plus cosmonauts are allowed to drink en route); dimes find me, I don’t even have to look; caddies have far less pressure, carry the weed & have full access to the world of leprechauns & I’d only do dental work on myself & leprechauns.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Those same former teachers, bosses, bullies, lovers, leprechauns & the like all made me write, for various reasons. It started with poetry & a journal that became a daily habit of not only having a conversation with myself, but with creativity itself. Getting out the ‘complaints’ & ‘passions’ & deep emotions, or exploring a surface-level issue or relationship is part of wanting to write. Playing with form & structure. Understanding that a story wants & needs to be told, whether it be in my journal or a poem. Reading definitely made me write, as well as the idea of storytelling, getting a reaction or especially a laugh was something I really enjoyed—the opportunities to do that on the page seemed open & endless to me & I went to work writing in every genre I could (poetry, short stories, novels, screenplays & travel writing), regardless of the outcome.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Burning in this Midnight Dream, by Louise Halfe. Her history & journey—the stories & trauma of her experiences in & out of residential school—is real & raw & inspiring & we can all learn so much from her. I’m teaching her collection in a course & want my students to deeply consider how history & language shape us.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A trilogy of Irish novels based on my Irish family history & a card game (Spit in the Ocean) set in 1840s Ireland, a travel poetry collection (The Stone Roses of Sarajevo), a collection of short stories (The Electricity of Crime) & a travel memoir (Around the World in 800 Days).

February 13, 2022

Bianca Stone, What is Otherwise Infinite

God Searches for God

Of my unclear and unimaginable self

I want none of it. There is nothing

higher than I. Only monks at my feet kissing warts.

I have nothing to give but tears, of which one

is too much and a whole sea

not enough. Do not fathom me here.

Do not touch this. Having laid the cosmic egg

who will take my eternal life in their hands?

It is said this planet came to be

when I was pulled apart.

It has been some time since I’ve seen a book by Vermont poet Bianca Stone, since her full-length debut,

Someone Else’s Wedding Vows

(Octopus Books and Tin House, 2014) [see my review of such here], having clearly missed out on

Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours

(Pleiades Press, 2016) and

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief

(Portland OR: Tin House, 2018), so I was curious to see her latest collection,

What is Otherwise Infinite

(Tin House, 2022). In sharp, first-person narratives working around (as the front flap of the collection offers) “how we find our place in the world through themes of philosophy, religion, environment, myth, and psychology,” Stone composes poems as threads connecting accumulating points; her narratives stretched as sequences of stunning lines and connective tissue. “Time does not go beyond its maiden name.” she writes, as part of “Does Life Exist Independent of Its Form?,” ending the stanza with the offering: “how uncomfortable we are with happiness.” I remember, years ago, Ottawa poet, publisher and archivist jwcurry describing the long poems of northern British Columbia poet Barry McKinnon: how every poem worked its way toward, and then away from, a singular, central point. In comparison, Stone isn’t writing with such length, nor with a single point, but up and away from multiple points-in-succession. It is as though she is composing poems as a series of communiques across telephone wires, connecting pole to further pole to build each poem’s thesis. Through What is Otherwise Infinite, the dense lyric structures of her debut have become far more complex, extended and philosophical; there is a further depth of attention here, one that could only be achieved through experience, as the second half of the poem “I’ll Tell You” reads:

It has been some time since I’ve seen a book by Vermont poet Bianca Stone, since her full-length debut,

Someone Else’s Wedding Vows

(Octopus Books and Tin House, 2014) [see my review of such here], having clearly missed out on

Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours

(Pleiades Press, 2016) and

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief

(Portland OR: Tin House, 2018), so I was curious to see her latest collection,

What is Otherwise Infinite

(Tin House, 2022). In sharp, first-person narratives working around (as the front flap of the collection offers) “how we find our place in the world through themes of philosophy, religion, environment, myth, and psychology,” Stone composes poems as threads connecting accumulating points; her narratives stretched as sequences of stunning lines and connective tissue. “Time does not go beyond its maiden name.” she writes, as part of “Does Life Exist Independent of Its Form?,” ending the stanza with the offering: “how uncomfortable we are with happiness.” I remember, years ago, Ottawa poet, publisher and archivist jwcurry describing the long poems of northern British Columbia poet Barry McKinnon: how every poem worked its way toward, and then away from, a singular, central point. In comparison, Stone isn’t writing with such length, nor with a single point, but up and away from multiple points-in-succession. It is as though she is composing poems as a series of communiques across telephone wires, connecting pole to further pole to build each poem’s thesis. Through What is Otherwise Infinite, the dense lyric structures of her debut have become far more complex, extended and philosophical; there is a further depth of attention here, one that could only be achieved through experience, as the second half of the poem “I’ll Tell You” reads: my sister tells me things

that frighten me

what I mean is

how did we get here

made of gingerbread in the oven

eaten by the mother

eaten by the wolf

my little pale nephew standing on the porch

explaining lava in the netherworld

that if you fall in a certain hole

in his game

you keep falling forever

and you don’t get to keep

any of the things

you made.

There is something curious in the way Stone attends to the “infinite,” writing around and through Biblical stories and texts, illuminated manuscripts and other religious depictions, considerations and conversations. “Human nature is bifolios,” she offers, as part of the poem “Illuminations,” “versos, even blank pages / with preparatory rulings for the scribes, never painted upon. / Little books of suffering saints and resurrections. / That’s what we are.” A few lines further, offering: “On this sheet / the Evangelist dips a pen into an inkpot / and rests an arm on the side of a chair, / inspired, like Luke, by the dove, / preparing to set down an account of a life / on paper made from the skin of sheep.” There is a wit to these poems, as Stone offers both guidance and clarity through lived experience and wisdoms hard-won, articulating her takes on depictions of the spiritual from sources high and low. She writes from a world that includes faith, medieval texts and trips to Walmart, and both a sense of ongoing intellectual and spiritual pilgrimage alongside flailing, falling and being nearly overwhelmed. “A serious drama in a cosmic joke. / Scarred,” she writes, as part of the poem “The Way Things Were Until Now,” “masked, dangerous. / And what of the new Eucharist? / How hungry I always am. How I long to lack. / Though in Walmart / my heart beats a little faster. / I want the world to heal up.” Here, Stone becomes the pilgrim, and the composition of these poems-as-pure-thinking are, in effect, as much the act of pilgrimage as they are the articulation of that same journey. “I don’t know. What is it to be seen?” she writes, as part of “Artichokes,” “I can forget / it’s language I long for. Man and his ciphers / cannot save me.” This truly is a stunning collection, as Stone offers her narrator a chaos equally physical and metaphysical that requires balance, one that can only be achieved through a constant, endless and attentive search.

February 12, 2022

Ellie Sawatzky, None of This Belongs to Me

WAYS TO WRITE A POEM

Imagine how you might be murdered, but

make it beautiful.

Think about sex but never do it.

Unlearn how to swim.

List eleven hundred verbs

and types of trees.

Think about which of your friends you’d

have sex with and why.

Say everything you might want to say

to your ex, but you’re a bird.

Sit in a room with some

blank-faced balloons until

you burst.

Don’t drink anything, not even

coffee. Be thirsty.

Imagine you’re in a car full of poets

and the car explodes, but

add magic.

Cut off a single finger.

Put on black lipstick.

Touch the white part

of the fire.

I’m enjoying the lyric narratives in Vancouver poet Ellie Sawatzky’s full-length debut,

None of This Belongs to Me

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2021), a collection of small studies each articulating different elements of her ongoing attempts to navigate and adapt to the various elements of entering the lived space of adulthood. She writes of her aging parents to the unfolding of expanded expectations, both from without and within. “In the silence now / we’re all adults and no one knows // what’s best.” she writes, towards the end of the poem “RECALCULATING.” Or the poem “COWHIDE, PLASTIC,” that includes: “How did I grow up and arrive // here, of all places, and who are / these people with their cowhide // from Key West, Pomeranian peeing / in the corner on plastic grass. Grown-ups // made me, explained things like sex / and art and garbage.” Sawatzky’s poems are carved portraits of thinking, less meditative than more immediately responsive to and within the moment. From her home base of Vancouver, a city she has been in long enough to have established roots, she writes of her shifting relationship to her hometown of Kenora, Ontario, the introduction of two points requiring her to seek a new sense of grounding between them. “My mother’s // voice in the smooth tunnel / of the telephone. She’s alone // in the loft with her nine-patch / and oldies channel. Hopeful // quilts on every wall,” she writes, to end the poem “I PRESS AN EAR TO ONTARIO,” “and Lassie / bounding black and white // across the Scottish Highlands.”

I’m enjoying the lyric narratives in Vancouver poet Ellie Sawatzky’s full-length debut,

None of This Belongs to Me

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2021), a collection of small studies each articulating different elements of her ongoing attempts to navigate and adapt to the various elements of entering the lived space of adulthood. She writes of her aging parents to the unfolding of expanded expectations, both from without and within. “In the silence now / we’re all adults and no one knows // what’s best.” she writes, towards the end of the poem “RECALCULATING.” Or the poem “COWHIDE, PLASTIC,” that includes: “How did I grow up and arrive // here, of all places, and who are / these people with their cowhide // from Key West, Pomeranian peeing / in the corner on plastic grass. Grown-ups // made me, explained things like sex / and art and garbage.” Sawatzky’s poems are carved portraits of thinking, less meditative than more immediately responsive to and within the moment. From her home base of Vancouver, a city she has been in long enough to have established roots, she writes of her shifting relationship to her hometown of Kenora, Ontario, the introduction of two points requiring her to seek a new sense of grounding between them. “My mother’s // voice in the smooth tunnel / of the telephone. She’s alone // in the loft with her nine-patch / and oldies channel. Hopeful // quilts on every wall,” she writes, to end the poem “I PRESS AN EAR TO ONTARIO,” “and Lassie / bounding black and white // across the Scottish Highlands.” There is something of this collection that really does seem engaged with seeking out the correct questions with which to properly move forward. Writing also on imaginary boyfriends, health and travel, she writes from that nebulous space of having arrived in adulthood, and the loose threads of her prior self that remain. She seeks a sense of grounding, one might suggest, before any further steps are possible, not wishing to untether from any sense of her history, community or family. Composing lyric meditations akin to the work of poets such as Stephanie Bolster or Karen Solie, Sawatzky’s poems display a polished craft that confidently articulate uncertainty, searching for what might not yet connect, but through which can’t help but reveal. “is freedom the opposite of anxiety?” she asks, in the first section of the five-part “IF YOU’RE WRITING THIS DOWN,” “what’s the opposite of stone?” She seeks to connect, and to hold. Later on, in the same poem, asking: “what’s the opposite of island?”

February 11, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kimberly Quiogue Andrews

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews is a poet and literary critic. She is the author of

A Brief History of Fruit

, winner of the Akron Prize for Poetry from the University of Akron Press, and

BETWEEN

, winner of the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Prize from Finishing Line Press. Her recent work in various genres appears in Poetry Northwest, Redivider, Denver Quarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing and American literature at the University of Ottawa, and you can find her on Twitter at @kqandrews.

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews is a poet and literary critic. She is the author of

A Brief History of Fruit

, winner of the Akron Prize for Poetry from the University of Akron Press, and

BETWEEN

, winner of the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Prize from Finishing Line Press. Her recent work in various genres appears in Poetry Northwest, Redivider, Denver Quarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing and American literature at the University of Ottawa, and you can find her on Twitter at @kqandrews. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first full-length book came out at the very beginning of the pandemic, so I guess I wish it had changed my life more than it did. But that's not being generous enough -- having my first book out in the world has opened all sorts of doors for me, from readings to whole jobs. It's irritating, on a systemic level, that a printed collection is required to open such doors. But on a more personal level, it is exceedingly gratifying to see those years and years of work coalesce into an object that you can hold in your hands, that other people can hold in theirs and have on their shelves. Unlike individually published poems, a whole book has the time to make a series of arguments that are, to use the old cliché, greater than the sum of their parts. My first book taught me that, to a degree; my more recent work really takes it to ridiculous extremes. What I'm writing now feels both much more experimental (formally) and much more rhetorically coherent; if my first book seems like it's aiming for a kind of formal range or virtuosity, my new work is just like these huge weird blocky or spindly bits of texts that are all hammering home a big, almost academic-critical point.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

This is probably a common answer, but: I cannot write plots. I've never been any good at telling stories; my imagination also seems incapable of the gymnastics required to actually make up a whole character. The first poem I ever wrote was in early high school, in response to a friend's sudden and devastating illness. I was trying to capture a kind of social shock, and it seemed to me at the time like a compressed, singular thing, like a bright light shining in your face. I suppose that's why it came out as a poem and not as a narrative. I've been stuck with the genre ever since.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm in the fortunate position of having several ideas going right now; starting creative projects has always come relatively easily to me (starting scholarly ones, on the other hand, I find nearly impossible). I don't do a huge number of drafts of a given poem; I do, however, take a lot of notes. I tend to write a lot of single drafts of different poems and then discard whole drafts and start over; I tell my students that I'm a notorious "blank-page" reviser.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I'm definitely a "book" poet, though I suppose that always starts by being a bit of a "theme" poet, by which I mean I'll get stuck on a thing that I want to write about, and then write like ten poems about that thing, and sometimes that stops shortly thereafter (hence, for example, my chapbook BETWEEN) and sometimes it turns out to have legs. I wish, at times, that I could be one of those poets whose books are simply a series of only loosely connected poems. I'm not really sure if books like that exist anymore, so great is the impetus towards "project" books.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I adore doing readings. Adore it! If you are reading this, email me and ask me to read for your class/book club/friend group/rowing association! I'm not sure if I'd say they're a part of my "creative process," but I find them energizing and fun and an integral part of being a writer.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

For better or for worse, the writing I'm doing now is 100% theoretical concern. My current project grapples with the question of how our lives might be different if we allowed sadness and slowness to be a part of them; it takes an explicitly anti-capitalist (which is to say, anti-productivity, anti-speed, anti-consumable-happiness) stance. The real current question, though--not for me, but for everyone--is climate change. It's not something I'm currently writing about in a concerted way, though of course one cannot write about degrowth without also sort of writing about climate change. My next project is about steel manufacturing, though (see, I told you I'm a horrible "theme" poet) so it will be interesting to see how it comes up when I can finally get to that book.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

There are lots of different types of writers, and correspondingly different types of roles for them. For poets and scholars, though, there's a type of demonstrated non-instrumentality to our work that is I think (a) increasingly vanishing and/but (b) increasingly important to safeguard. Lots of people want to be artists because there's some idea of "freedom" in there. Is that ideological? Probably. But is there also some truth to the idea that it's hard to alienate the work of a poet or a painter. When you do, you get slogan-writing and graphic design, which are not the same things, though of course they can be very good careers. The role of the writer, then, is maybe just to demonstrate that we should abolish all careers. A strange thing about me is that I am very pro-professionalism and very anti-career. I do think they're separate.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I've not worked with that many outside editors, but my experiences have been good. My poetry editor, Mary Biddinger, is a marvel. She will provide exactly the amount of help you need on a given thing. Usually the process of publishing poetry is a pretty hands-off affair.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Learn to recognize the people around you whose actions are dictated by opportunism or other kinds of jobbery, and then proceed to avoid them to the fullest extent to which that is possible.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I cannot do scholarship when I am writing poetry and vice-versa. The two genres influence each other enormously -- I'm a scholar of experimental poetry -- but I can't do them both at the same time. I'm a one-hat kind of person. That said, when I am writing poetry, I am thinking about scholarship, and when I am doing scholarship, I am thinking about poetry projects. In that sense they're inseparable, but the work itself happens almost entirely separately.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I, like most people I suspect, am in constant search for the perfect routine. Right now, I'm finishing a scholarly project, and I write prose best in the afternoons. So mornings are devoted to walking and administrative procrastinating, and then I'll (hopefully) settle into writing after lunch. For poetry, it's the opposite -- I write it best in the mornings, so I'm going to have to change things up when I get back to it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading in the general vicinity of what I might want to be writing about. Every time, no exceptions. Not just poetry, though that's a lot of it. The reason I have a current book project is because I found a PDF of Saturn and Melancholy on the internet and was so smitten with it I decided to write an entire book basically in response to it. That's it!

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I feel like my mom used to have a small bottle of White Diamonds lying around, and I'd bet almost anything that if I smelled that perfume again I'd be walloped right back to the suburbs of eastern PA. My other, adopted, home is central Maine, which smells unavoidably of pine.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of those things influence my work, which sounds like a non-answer, but when your guiding philosophy is that poetry is just particularly intense noticing, it kind of doesn't matter what the focus of the noticing is. It can all become fodder.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The classic answer: too many to name! John Ashbery's work gave me my start, in a real sense, even though that "start" was at the very end of my MFA. W.G. Sebald keeps me going. Dionne Brand is constantly teaching me how to think. John Keene is not only one of the world's most remarkable writers, but also one of the world's most generous and thoughtful people. I go to Brigit Pegeen Kelly when I want to be astonished. And to Brian Lennon when I want to remember what's important. There's no end to this list, really.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

[Insert a bunch of deeply un-laudable personal ambitions here.]

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

This was always kind of it for me, I think, though had my knees held up I probably could have been a ski instructor forever.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Being really shit at both team sports and acting?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just read Rebecca Makkai's The Great Believers and it's just as devastating as everyone says it is. Last great film would definitely be Face/Off. I hadn't seen it until this past summer! It belongs in the Louvre.

20 - What are you currently working on?

See question 6, though I'm also trying desperately to finish up a scholarly book called The Academic Avant-Garde that should be out with Johns Hopkins University Press late next year. Catherine, if you're reading this: I'm working on it!

February 10, 2022

CrossCountry – a magazine of Canadian-U.S. poetry/CrossCountry Press (1975-1983): bibliography, and an interview

Jim Mele is a journalist and writer living in Connecticut. He was co-editor of CrossCountry, a Canadian/US literary magazine and publisher, and also served as general manager of the New York State Small Press Assn., a non-profit created to distribute literary and artistic publications. He has traveled broadly both as a journalist and as a curious private citizen. His journalism has been recognized with numerous awards including three Neal Awards for op-ed commentary, and has published four collections of poetry and a critical study of Isaac Asimov’s science fiction. He holds a BA in English from Stony Brook University and an MA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York.

Ken Norris was born in New York City in 1951. He came to Canada in the early 1970s, to escape Nixon-era America and to pursue his graduate education. He completed an M.A. at Concordia University and a Ph.D. in Canadian Literature at McGill University. He became a Canadian citizen in 1985. For thirty-three years he taught Canadian Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Maine. His latest poetry title is South China Sea: A Poet's Autobiography (Guernica Editions, 2021), and he’s published nine chapbooks with above/ground press, including three in 2021. He currently resides in Toronto.

Q: How did CrossCountry first begin?

Q: How did CrossCountry first begin? Jim Melé: Ken and I met as freshmen at Stony Brook University on Long Island about 60 miles outside of New York City. We remained close all four years, even hitchhiking across the country to California one summer and sharing a house in our last year. We also both discovered a passion for poetry at Stony Brook although through slightly different paths. Ken found his enthusiasm through the classes of Louis Simpson, a Pulitzer winning poet and Yeats scholar, and me though a younger lecturer named George Quasha. But for both of us poetry was an exciting world.

When we graduated in 1972, Ken moved back to NYC to pursue music with a band and I went on to the creative writing program at the City College of NY, studying with the beat poet Joel Oppenheimer. By 1974, I’d moved on to my first job on a strange newspaper for merchant seamen and Ken had taken off for Montreal to study at Concordia and then McGill. Poetry still consumed us, and we began an active correspondence.

For me, I was beginning to read and then meet many of the young non-academic poets that filled NYC bars and other venues as well as discover the non-traditional poets that inspired them, poets like Jack Spicer, Gary Snyder, William Bronk, Ted Berrigan. And Ken was quickly finding his cohorts in the young Montreal poets like Artie Gold and Endre Farkas, as well as other Canadians like bp nichol and George Bowering. Few of the Canadian poets were being read in the US, and most of the Canadian ones were somewhat removed from the active young poetry scene I was finding in NY. To Ken and me it felt like there were unnecessary parochial boundaries dividing two vibrant poetry cultures along meaningless national lines. Naïve on our parts, yes, but also true to a large extent.

And that’s how Cross Country started. We decided there was room for another small magazine that presented Canadian and US poets on a single stage. The hope was to introduce both groups to broader audiences. We published the first issue in 1975.

Q: How did you get the word out for that first issue? Was all the work within solicited? Did you send out a call? And, given you were working with systems on both sides of the border, how were issues distributed?

Ken Norris: I THINK I was still in New York as we started to put the first issue together. I must have sent a letter to George Bowering, because he’s in the first issue (I think). And the Davinci chapbook poets are in it (Ezzy, Farkas, Ferrier, Lapp). I wrote an essay about Atwood. I’m pretty sure all the work was solicited, and that would have been by mail. I think there were distribution networks on both sides of the border to plug into. We recruited institutional/library subscriptions, and got about 100 of them, I believe.

JM: Yes, all the work was solicited. Ken and I simply wrote letters to poets we admired and told them that we were starting this US/Canadian small magazine, and most sent us contributions. We ended up with a really diverse mix, probably the most diverse in the entire course of the magazine. Besides Bowering and the Davinci group, it included Robert Kelly, Eve Merriam, Muriel Rukeyser, Tom Konyves, Phillip Lopate, William Bronk among others. Established poets who had no idea who we were were incredibly generous.

Distribution was a problem, as it was and is for almost all small magazines. I took the magazine around to all the bookstores in NY that I knew. The important literary independents like the Gotham and St. Marks were open to taking a few, but also a number of others did as well, if with a bit of reluctance. The big boost came from library subscriptions, which we solicited by direct mail using some lists we managed to scrape up. And we did the same with review copies, which began to bring us some individual subscriptions and submissions. I believe we also listed the magazine with some of the writers’ resource publications.

Q: You both mention “the Davinci group.” Could you explain this reference? It isn’t one I’m aware of.

KN: Eldorado Editions. Four chapbooks came out in 1974, by Tom Ezzy, Endre Farkas, Ian Ferrier, and Claudia Lapp. Not that much was going on in Montreal, publishing-wise, at that time, so these were a big deal. I think they were an offshoot of Davinci magazine, which was edited by Allan Bealy.

Q: What kinds of response did you receive for those first few issues? Were there any responses you weren’t expecting, whether in terms of straight response, or even potential submissions?

JM: I don’t have any specific memories, but after the first issue we started attracting a large volume of unsolicited submissions at the US address. And if I remember correctly, Ken had the same response in Canada. Subscriptions and single-issue sales were much slower building.

The second issue, published in the Summer 1975, represented a big step forward in my mind. On a superficial level, the production quality was much improved over No. 1, which had been typeset on an IBM electric typewriter and printed on remanent paper stock. More importantly, it was entirely work Ken and I had solicited personally and reflected the poetry that was exciting us. For my part, the poets I approached were enthusiastic about the idea behind establishing a Canadian/US poetry platform.

The next issue pushed things to an entirely new level. It was focused solely on Montreal and was largely Ken’s baby, so I’ll let him talk about it. But I do remember that we doubled the print run from our usual 500 copies and even so it was the first issue to sell out. Also by that time was I was involved in the New York Small Press Fair, an annual event that drew nearly 100 small literary presses as exhibitors and large crowds. Our Montreal issue attracted a lot of attention, selling every copy we’d brought to an audience we’d never have reached relying only on direct mail and limited bookstore sales.

KN: We’d get in trouble with poets like Robin Mathews soon enough. Some “Canadian nationalists” didn’t like what we were up to.

The Montreal issue (#3/4) was a lot of fun to put together. We built a bridge to the les herbes rouges poets—so there were ten Quebecois poets in the Montreal issue, including Claude Beausoleil, Yolande Villemaire and Nicole Brossard. The Vehicule poets would continue to collaborate with les herbes rouges poets for years.

Right from the get-go, I asked a lot of Canadian poets for poems, and they rarely refused. I remember the time I asked Al Purdyto send me a few poems, and he sent me the entire manuscript of Piling Blood. He told me to take the ones that I really liked. Frank Scott invited me over to his house and we dug up a couple of unpublished poems. In the Montreal issue we published a section of John Glassco’s long poem Montreal. Interesting things happened with just about every issue.

Q: The basic argument for the journal, as I’ve always understood it, is simply poets from either side of the border engaged in a larger conversation with each other. How could anyone have a problem with that? I suppose the next question to ask: prior to this, how easily was writing travelling across the border? How easy or difficult was it for someone in either country during those days to purchase a book from a poet in the other country?

JM: On a personal level poets on either side of the border would trade books with each other, but Canadian poets were largely unavailable in bookstores unless like Leonard Cohen they also had a US publisher. And I believe it was the same in Canada, at least for any poet not with a major commercial publisher. I think the interest was there, but there were practical barriers that went beyond unfamiliarity. Sending even a single box of books across the border into Canada or into the US was an expensive, long and complex process that required paying duties and hiring a customs broker to handle all the paperwork. If you didn’t follow the rules, it was likely the shipment would be seized. That happened to us with Lionel Kearns’ Ignoring the Bomb. Ken sent me a box of copies to distribute that never emerged from US Customs. Literary presses in the 1970s and 80s just didn’t have the resources or experience to navigate customs. The one exception might have been Coach House since I do remember seeing their titles in a few major NYC literary bookstores. For the most part we relied on my car trips to Montreal to bring CrossCountry across the border.

KN: Those were different days. Xenophobia could masquerade as nationalism. Lionel's book got seized because they thought it was anti-nuclear propaganda. Weird things happened sometimes.

Globalization changed all that. We wound up being on the right side of history.

JM: In Lionel’s case that was probably true, but the legal correspondence with US Customs and the proposed bills from customs brokers as well as warehousing bills were awe inspiring. The big publishers on both sides supported and promoted those trade barriers as business strategies. No exceptions for small literary publications unless they were small enough to slip under the regulatory gaze.

Q: You mention Eldorado Editions. What other publishers or publications were around during those days? What publications did you see CrossCountry in conversation with, if any?

KN: I was an editor at CrossCountryand CrossCountry Press while also being one of the poetry editors (along with Endre Farkas and Artie Gold) at Vehicule Press. So there was that.

In a time of Canadian nationalism, we kind of stood out. I think there was a magazine called New that was also publishing Canadian and U.S. poetry. And I always had a soft spot for Unmuzzled Ox. And I liked what 52 PIck-Up was doing. And, of course, Coach House.

At that time I was also the Quebec regional rep of CVII.

Through Artie we came into contact with Geoffrey Young and The Figures. I became a big fan of Stephen Rodefer’s poetry. And we had a bird’s eye view of the language poetry scene, which we liked and didn’t like.

I can’t remember if we published any poetry by Stephen Rodefer and Lyn Hejinian in CrossCountry. I certainly wanted to.

JM: NY was swarming with literary presses in the 1970s and 80s, and CrossCountry was in the mix through things like the NY Small Press Assoc and the Small Press Book Fair. But there was little Canadian content beyond what we were publishing. We did have loose connections with Unmuzzled Ox, publishing a chapbook by its editor Michael Andre and a collection by Larry Zirlin, one of the editors at SOME/Release Press.

Q: What moved you into publishing chapbooks and books as an extension of the journal?

Q: What moved you into publishing chapbooks and books as an extension of the journal? KN: Grant money. We were eligible for National Endowment of the Arts grants.

But the first two chapbooks were one of mine and one of Jim's. We were able to get them printed cheap, so why not do them? Under The Skin was my second publication, after Vegetables.

JM: As Ken said, we became eligible for grant money from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Arts Council. And a production/printing organization subsidized by the NY council was created to help support literary and arts publishers, which gave us access to typesetting facilities and low cost quality printing, so we started expanding into chapbooks first and then full-length books to complement the magazine. We eventually published 15 books along with 16 issues of CrossCountry.

Q: It is one thing to run a journal with a border between you, but how was it running a publishing house? I know of at least one book that disappeared through the mail. What were the difficulties in attempting to produce chapbooks and books?

KN: As I remember it, most of the CrossCountry Press titles were produced in the States. So there really wasn't a border between us. The funding for the books was in the States, and the book production was in the States. There were a few exceptions. Artie’s some of the cat poems and John McAuley's Hazardous Renaissance and Mattress Testing were printed at Vehicule. I remember typesetting some of the cat poems AT Vehicule.

Ignoring The Bomb was a co-publish with Oolichan. They had the title in Canada and we had it in the U.S. Oolichan produced the book.

Ignoring The Bomb was a co-publish with Oolichan. They had the title in Canada and we had it in the U.S. Oolichan produced the book. All the rest of the titles were produced in the States, with Jim overseeing their production.

So, at the time, I felt like book publishing was working like a dream. But I wasn't doing most of the work. Jim was doing most of the work.

JM: Yes, most of the resources – money and physical production capability – were in the US so that’s where most of the books were produced. The major hurdle wasn’t the border – it was distribution in both countries. The book distribution business was set up to accommodate large publishers with sales, promotion and fulfillment staff. Unless they were really committed to giving visibility to small literary presses, bookstores didn’t have the resources or will to deal with them. And to be truthful most of us running small presses didn’t have the experience or will to address that side of publishing. So we had to rely on direct sales to libraries and interested individuals that managed to find us. We had a few successful titles – the Baudelaire essays and McFadden’s chapbook The Saladmaker were two I recall offhand, but for the most part even the good reviews many of our titles got were not enough to attract the audiences they deserved.

Around 1981 I began working part-time as the general manager of the NY State Small Press Association, which was created with public and private grants specifically to distribute literary and art books. At its peak it had titles in stock from well over 100 presses. But it never evolved into an operation that could stand on its own and compete with major publishers, so once the grants ran out it faded away. That’s also when Ken and I moved on from CrossCountry to other projects.

Q: Did either of you notice a difference in response to books from either side of the border? A couple of years back, Jay MillAr at Book*hug mentioned a stretch of time when the books they published by American writers did well in the United States, but not in Canada, and the books they published by Canadian writers did well in Canada, but not in the United States, despite their entire catalogue having equal distribution and marketing in both countries. Had you a version of the same?

Q: Did either of you notice a difference in response to books from either side of the border? A couple of years back, Jay MillAr at Book*hug mentioned a stretch of time when the books they published by American writers did well in the United States, but not in Canada, and the books they published by Canadian writers did well in Canada, but not in the United States, despite their entire catalogue having equal distribution and marketing in both countries. Had you a version of the same? JM: Pretty much. Among the Canadian titles, Artie Gold’s cat poems and David McFadden’s three attracted the most interest from US readers. And when we participated in US book fairs, there seemed to be a lot of curiosity about both the magazine and the Canadian authors.

KN: Hmm. I think I would say No. We were small press. Responses to small press tend to be quirky. Individuals on either side of the border would chance upon a title and register a response to it. We weren't being swept up in large-scale cultural trends.

Forty-three people across North America would discover and respond to David McFadden's A New Romance. We were really presenting a North American argument. At that time, we were trying to dissolve the differences between U.S. and Canadian poetry.

The Tish poets and the Coach House poets made the most sense to me of the poets in Canada, and they were cut more from North American cloth rather than from Canadian cloth.

Readers. My old friend Burt Hatlen used to say that we have more readers than we think we do. Poetry circulates in a really unusual fashion. I think borders and nationalities tend to be meaningless, and these days I think we concede that every poet establishes their own tradition that has nothing to do with nation-states. But the most influential poet in my life since I was seventeen is the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. And after him it's probably Lorca. I'm a Canadian poet who reads a lot of Canadian poetry, but it isn't all that I read, and the local isn't maybe even all that important much of the time.

CrossCountry was an invitation to discuss how poetic tradition works. Again, I would say that we were making an argument for North American poetry, and in a way that American poetry doesn't subsume Canadian poetry. We were interested in a mode of presentation in which Robert Creeley and George Bowering, say, would be seen as equals.

JM: That was certainly our intention with CrossCountry, magazine and books both.

Q: What prompted your movement into special issues, whether the postcard issue, the detective issue or the “New Romantics” issue?

KN: The first special issue was the Montreal issue (#3/4). We got a grant to do that one.

The Postcard issue gave me a chance to work with the designers at Dreadnaught Press. Coach House specialized in “visual arts” postcards, and there were some other poetry postcards making the rounds.

The Postcard issue was 20 postcards, 10 Americans and 10 Canadians. Margaret Atwood sent us a poem for that one, George, David McFadden. The Vehicules got into the mix: Artie, Tom, Endre, myself. I think there was a William Bronk poem. Jim and I were BIG fans of William Bronk.

The postcards got a lot of use. Back then, a writer’s life took place in the mail. It was all letters, submissions, acceptances and rejections. The postman was my favorite person.

JN: The detective issue was just fun. I was reading a lot of pulp noir from the 1930s and 40s (with enthusiastic prompting from Artie Gold) and other poets responded to the proposal so we commissioned an art director I knew to create a pulp cover and deco initial caps, and we were off.

The New Romantics was a response to a trend we saw among the poets we admired, a modern take on the romantic movement of the 19th century and a reaction to the abstract, cerebral work that predominated the academic journals.

Q: Your Montreal issue included a section of poems composed in French, with a French-language editor on the masthead, alongside a selection of poems composed in English. What were the interactions between the English-language and French-language poets in the city at that time? How was the issue received?

KN: The collaboration with the editors of les herbes rouges was a one time event. But it established that my crowd, the Vehicule Poets, was interested in working with their crowd. Claude Beausoleil, one of the poets in the Montreal issue, went on to be the French “editor” of the poetry on the buses project. With Lucien Francoeur and Claudine Bertrand, Endre Farkas and Ruth Taylor and I edited Montreal Now, a mag/reading series in the mid-1980s. In the early eighties, Michel Beaulieu and I used to go out for a weekly lunch in Chinatown, to discuss what was going on in poetry in the entire city. Michel took me to vernissages, where I had the opportunity to talk with poets like Gaston Miron and Nicole Brossard. I was very interested in the Quebecois scene.

Our generation of Montreal Anglo poets probably had more contact with our Quebecois peers than Klein’s generation did, or Dudek’sgeneration did. A number of the Vehicule poets had books that were translated into French. And most of the les herbes rouges poets had books appear in English.

JM: This was really Ken’s project so I don’t have much to add. We talked a bit about it being impossible to do something that claimed to capture poetry in Montreal without participation by Québécois poets. But we also recognized why some might not want to be included in an Anglophone magazine no matter how good our intentions. Ken did a great job of handling that conundrum.

Q: Tell me about the les herbes rougespoets! I know absolutely nothing about them.

KN: At the time (mid-70s) they were the young avant garde, like we were. The Hebert brothers (editors) also included Nicole Brossard in their selection. There are books translated into English by Claude Beausoleil, Yolande Villemaire, Andre Roy and Francois Charron. I think also by Philippe Haeck and Roger Des Roches. They’re all old now, like we are. Claude passed away recently. Guernica Editions published quite a number of translations of their work. As you know, many of Nicole Brossard’s books have been translated into English.

Q: In hindsight, what do you see as the takeaway from your time together doing CrossCountry? What do you feel the journal and press most accomplished, or made possible?

KN: Jim and I were friends at university (SUNY at Stony Brook) and we were also poetry friends. So, CrossCountrygave us a way of making our enthusiasms real. Running CrossCountry, the magazine, gave us a way of proselytizing for the poetry that we loved; it also got our names out there, as editors and as poets. So, there was a bit of career-building.

And running the press REALLY gave us a way of getting behind the poetry that we loved.

It’s hard to explain how “insular” Canadian literature could be back in the early seventies. I think we let in a lot of fresh air, and also backed up the Tish poets and the Coach House poets in seeing American poetry as a valid influence upon Canadian poetry. Robin Mathews chastised Raymond Souster and me for cultivating American influences. I thought that was really stupid at the time, but his line of argument got some traction among the nationalists.

JM: At the time US poetry was exploding (in a relative way) beyond the traditional voices as small presses began aggressively popularizing a much broader and more diverse perspective on what poetry could be. For the most part Canadian poetry was not part of that new mix, maybe because there were so many new voices competing to be heard. Opening a venue in the US for the vibrant new poetry scene growing in Canada was exciting. And consciously choosing to downplay, if not ignore, nationalistic claims to relevance was both our reason for creating CrossCountry and what in the end I consider our real achievement.

Q: What was behind the decision to end the journal and press? Were the two shuttered simultaneously? Was it really just a matter of the two of you wishing to move on to other projects?

Q: What was behind the decision to end the journal and press? Were the two shuttered simultaneously? Was it really just a matter of the two of you wishing to move on to other projects? KN: Things were winding down around 1983 or 1984. By 1985, I was moving back to the U.S., to teach Canadian Literature at the University of Maine. That put us both on the same side of the border.

The magazine ran sixteen issues. Those that make it past twenty usually make it to a hundred. We didn't have that kind of energy.

And the press had made its statement, with twenty-something titles. We wound up not being in it for the long haul. I edited at Vehicule Press for six years and at CrossCountry Press for eight. In 1984, Leonard Cohen suggested to me that I focus on my own work, and when he said that I was ready to hear it.

JM: As Ken said, it wound down slowly over a few years. He’d moved from Montreal to Maine, and I’d moved from New York to Connecticut. I’d also taken on a new job at a business magazine that proved highly immersive and more than full time. And I was a new parent.

We’d had a good run with both the magazine and press, and it was time to make room in our lives for the next stages.

CrossCountry – a magazine of Canadian-U.S. poetry bibliography:

No. 1. Winter 1975. Editors: Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Contributing Editor: Robert Galvin. Poems by Terry Stokes, Tom Konyves, Mary Morris, Carmen Vigil, Frederick Feirstein, Robert Kelly, Jim Mele, Thomas Danisi, Eve Merriam, George Bowering, Marguerite Harris, John Hollander, Ken Norris, Phillip Lopate, Robert Galvin, William Bronk, David Lehman, Richard Elman, Muriel Rukeyser, Claudia Lapp, Ian Ferrier, Tom Ezzy and Andre Farkas. SURVIVAL IN THE WRITINGS OF MARGARET ATWOOD by Ken Norris. Art Work: Debbie Creamer, Ruth Bauman and Simona Oelbaum.

No. 2. Summer 1975. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Poems by Barbara Holland, David McFadden, Artie gold, Janet Marcus, Ken Norris, Jim Mele, Dan Gabriel, richard sommer, Matt Tolland, Robert Galvin, George Jonas, Alden Nowlan, George Woodcock, Claudia Lapp, Allen Ginsberg, Raymond Souster, Kathleen Chodor, Fraser Sutherland, Len Gasparini, Monica Raymond, John Robert Columbo, Janet Sternburg, David Bromige and Terry Stokes. Review: Jim Mele on Terry Stokes. Artwork: Debbie Creamer, Allan Bealy, Ken Gugliolmo, Paul Adam and Bill Luddy.

No. 3/4. 1975. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Editeur français: Marcel Hébert. Editorial Assistants: Tom Konyves, Jill Martinez. Art Direction: Faigy Fudem. Layout & Typesetting: Si Dardick, Guy Lavoie. Special Issue: Montréal. Poèmes en français: Claude Beausoleil, Yolande Villemaire, Renaud Longchamps, André Beaudet, Normand De Bellefeuille, Phillippe Haeck, André Roy, François Charron, Roger Des Roches and Nicole Brossard. Poems in English: Stephen Morrissey, David Skyrie, D.G. Jones, Artie Gold, Morgana Fair, Tom Konyves, John McAuley, Matt Tolland, Claudia Lapp, Gary Livingston, Gertrude Katz, Louis Dudek, Andre Farkas, Richard Carson, Martin Newman, R.G. Everson, Richard Sommer, Carol H. Leckner, Shulamis Yelin, Ken Norris, Tom Ezzy and John Glassco. Reviews: Joanne Harris Burgess on Hutchman, Glassco, Gordy, & Sutherland; Michael Springate on Yelin, Thornton, Leckner, & Katz; Carol H. Leckner on Metcalf, Woods, & Kent; Tom Konyves on Gold, Burgess, Solway, Van Toorn, & Plourde; Ari Snyder on Ferrier, Farkas, Ezzy, Lapp, Norris, & McGee. Art Work by Daniel Pearce, André Desjardins, Jill Smith and Allan Bealy.

No. 5. 1976. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Poems and prose by George Bowering (a serial poem, an interview, a review), David Ignatow, Ralph Gustafson, Peter Cooley, Opal L. Nations, ken Norris, David McFadden, William Bronk, Louis Dudek on Ezra Pound, Terry Stokes, Rochelle Ramer, Richard Elman, D.W. Donzella, Jim Mele, Artie Gold & Goeff Young, Barbara Holland and J. Michael yates. Reviews: John McAuley on Seymour Mayne, Jim Mele on William Bronk & Peter Cooley, Tom Konyves on J.B. Thornton McLeod. Short Reviews & Excerpts. Graphics by Debbie Creamer, Leavenworth Jackson and Bill Luddy. Cover photo by Scott Bowron.

No. 6/7. 1977. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. A Special Reprint Issue. The Lady Poems, by Terry Stokes. The Saladmaker, by David McFadden.

No. 8/9. 1977. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Poems and prose by Steve McCaffery, Colette Inez, Jared Smith, Morgan W. Nyberg, David McFadden, Jean Berrett, Artie Gold, Al Purdy, Shulamis Yelin, Opal L. Nations, Anne McLean, Lionel Kearns, Arthur Stone, Constance de Jong, Wilbur Snowshoe, Tom Konyves, F.R. Scott, Earle Birney, Murphre Roos, George Bowering, Patrick Lane, Andrew Suknaski, Vladimir Banjo, Jim Mele, Rochelle Ratner, Ken Norris and bpNichol. An interview with bp Nichol by Jack David & Caroline Bayard. Reviews: Colin Morton on John Pass & Brian Brett; Ken Norris on Tish; Elliot S. Glass on poetry in the Barrio and Pedro Pietri.

No. 10/11. 1978. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Murder, Mystery and Poetry – A Special Detective Issue. Contents: “The Black Mountain Influence,” George Bowering; “IF They Hang You,” Murphre Roos; “Danger Came on Rainwet Streets,” Eugene McNamara; “A Reading of Rex Stout,” Mona Van Duyn; “For Raymond Chandler,” John Love; “The Dead Line,” Larry Zirlin; “Detective Work,” Abigail Luttinger; “The Investigator,” Joseph Bruchac; “The Private Dick,” “Moonlighting,” Jim Mele; “A Man From The Water,” David Young; “Whodunit,” Florence Trefethen; “Private Eye,” Artie Gold; “Gruber,” “There Was No Knock on the Door,” Andre Farkas & Ken Norris; “Poem ‘Murder’: A Scenario,” steve mccaffery; “A Theater Piece,” Rene Magritte; “Nat Pinkerton,” “The Surrealists’ Use of Detective Fiction,” Rochelle Ratner; “The Occupant,” steve mccaffery; “Some Evidence of Foxing,” Paul De Barros; “The Case of the Missing Secretary,” Arden Kahlo; “Archer,” Sydney Martin Dore; “Motive, Opportunity & Weapon,” Ken Norris; “The Glass Key,” “Missing Persons,” Mark Jarman; “The Chaplin Kidnap,” Opal L. Nations; “Murders in the Welcome Cafe,” Andre Farkas.

No. 12. 1979. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Special Postcard Issue. Poems on postcards by Margaret Atwood, George Bowering, William Bronk, Siv Cedering Fox, Tom Clark, Andre Farkas, Robert Flanagan, Artie Gold, Anselm Hollo, Tom Konyves, Patrick Lane, Gerald Malanga, David McFadden, Jim Mele, Ken Norris, Murphre Roos, Terry Stokes, Peter Van Toorn, Geoffrey Young and Larry Zirlin.

No. #13-15. 1982. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Poems and prose by Lew Welch, Gloria Frym, Artie Gold, Stephen Rodefer, Christopher Dewdney, Geoffrey Young, Liz Lochhead/John Oughton, Ken Norris, Jim Mele, Paul Kahn, George Bowering, Richard Elman, Gerri Sinclair, Tom Hawkins, Diana Hartog, Robert Galvin, Stephen Bett, Lyn Lifshin, Norman Fischer, Penny Kemp, Susan Mernit, Rochelle Ratner, Jim Smith, Peter Brett, Erling Friis-Baastad, jack Hannan, Peter Van Toorn, bill bissett, Louis Dudek, Frank Davey, bp Nichol, John McAuley on Philip Whalen, Artie Gold on Gloria Frym and Ken Norris on a Baker’s Dozen Poetry Books.

No. #16. 1983. Editors: Robert Galvin, Jim Mele, Ken Norris. Special New Romantics issue. Contents: Jim Mele, “The Art of Discovery” (essay), David McFadden, “Night of Endless Radiance” (poem) and Ken Norris’ “Acts of the Imagination” (poem).

CrossCountry Press (books and chapbooks) bibliography:

Ken Norris, Under the Skin. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1976.

Jim Mele, An Oracle of Love. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1976.

Terry Stokes, The Lady Poems. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1977.

Ken Norris, Report on the Second Half of the Twentieth Century. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1977.

David McFadden, The Saladmaker. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1977.

Jim Mele, The Sunday Habit, 1978.

Artie Gold, some of the cat poems. 1978.

John McAuley, Mattress Testing. 1978.

John McAuley, Hazardous Renaissance. 1978.

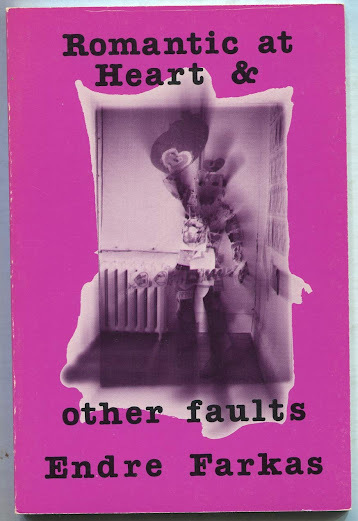

Endre Farkas, Romantic at Heart and Other Faults. 1979.

David McFadden, A New Romance. 1979.

Larry Zirlin, Awake for No Reason. 1979.

Ken Norris, Autokinesis. 1979.

Michael Andre, Letters Home. A CrossCountry chapbook. 1979.

Murphre Roos (Jim Mele), Sonnets & Other Dead Forms. 1980.

David McFadden, My Body Was Eaten by Dogs: Selected Poems, ed. George Bowering (simultaneously published by McClelland and Stewart). 1981.

Charles Baudelaire, Fatal Destinies: The Edgar Allan Poe Essays. 1981.

Lionel Kearns, Ignoring the Bomb: New & Selected Poems (co-published with Oolichan Books). 1982.

Jim Mele, The Calculation of Two. 1982.

Paul Metcalf, Louis the Torch. 1983.

February 9, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Richard Hamilton

Richard Hamilton is a Black, queer, gender non-conforming writer with a disability. He is a poet and cultural worker who spent much of his adult life as an itinerant worker in the service industry, indifferently housed. A Cave Canem alumnus, his poetry has appeared in CONSEQUENCE magazine, XCP: Cross Cultural Poetics, Steel Toe Review, The Drunken Boat, and Cave Canem Anthologies edited by poets Cornelius Eady and Toi Derricotte. He is the recipient of fellowships from The Chatauqua Writers' Festival and The Vermont Studio Center. In 2020, he received the Oscar Williams and Gene Derwood Award. He holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Alabama and MA in Arts and Public Policy from New York University. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Richard Hamilton is a Black, queer, gender non-conforming writer with a disability. He is a poet and cultural worker who spent much of his adult life as an itinerant worker in the service industry, indifferently housed. A Cave Canem alumnus, his poetry has appeared in CONSEQUENCE magazine, XCP: Cross Cultural Poetics, Steel Toe Review, The Drunken Boat, and Cave Canem Anthologies edited by poets Cornelius Eady and Toi Derricotte. He is the recipient of fellowships from The Chatauqua Writers' Festival and The Vermont Studio Center. In 2020, he received the Oscar Williams and Gene Derwood Award. He holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Alabama and MA in Arts and Public Policy from New York University. He lives in Washington, D.C. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It hasn’t changed my life, per say. When I reread my thesis manuscript from years ago as an MFA student at the University of Alabama, I get the sense that my work has matured in some ways and remained the same in others. It feels different in terms of my commitment to subject matter and the handling of that via received and free verse poetic forms. I am definitely less confessional.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry seriously after taking a survey course in poetics taught by Laura Mullen at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. Fiction writer John Calderazzo was on staff there and I dabbled with fiction and literary nonfiction as well as nature writing, all genres I still love. I learned of Rebecca Solnit, Edward Abbee, Barbara Kingsolver, and others whose work I reference when thinking about lyric essays. Still, Laura’s class stuck to my bones. Culturally speaking, she made sure we read a great many poets from the diaspora: Yusef Komunyakaa, Sonia Sanchez, Jayne Cortez, Amiri Baraka, Marilyn Nelson, Rita Dove, Wanda Coleman, Harryette Mullen, Lucille Clifton and so many more. Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program, I like to say, was up the block in Boulder. So, the ghost of beat writing past always held sway. I got a dope ass foundation in poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am a note-taker. In fact, one of my favorite things to do is visit footnotes and endnotes for source material and elaboration on a topic. For me, it takes longer to find out the shape and form of the poem. The ideas come fast, but there is still some hesitation in gathering those thoughts for fear that they are muddy waters best traversed with protective gear. Of course, I am messy—dive right in, looking for jewels, words or phrases that signify and push at a thesis. I like to think that all poems, no matter how cryptic, have the material parts that elucidate an argument the way a good essay does.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

It begins as an investigation, as a subject that irks me, as something I want to, need to clarify or complicate. Poetry is beautiful that way. We spend so much time recycling talking points in “the real world” that it is nice to visit a space where nuance rules. As for projects, it's safe to say I am working on a chapbook from the very beginning. Never a whole collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love poetry readings. I do get bored because I think that some poetry lends itself to being read versus listened to in a public space. At the end of the day, I think whatever poets one enjoys reading, they’ll enjoy seeing them perform that verse. If you like reading Tony Hoagland’s poetry, for example, then chances are you’d kill to see him in a live context. Yes, readings drive my creative process.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I like to write through my understanding of and concerns for history from below. Who are the actors, persons, objects, movements that are written out of official narratives? I don’t know if there are current questions that we should all conform to. Justice is always central to my writing projects.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?