Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 138

January 16, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kylie Gellatly

Kylie Gellatly is a visual poet and the author of

The Fever Poems

from Finishing Line Press (Summer 2021). Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Action Spectacle, Counterclock, DIAGRAM, Iterant Magazine, Gasher, La Vague Journal, Petrichor, Literary North, SWWIM, and elsewhere. Kylie is the Book Reviews Editor for

Green Mountains Review

, Editor-in-Chief of

Mount Holyoke Review

, and a Frances Perkins Scholar at Mount Holyoke College. For more, visit www.kyliegellatly.com

Kylie Gellatly is a visual poet and the author of

The Fever Poems

from Finishing Line Press (Summer 2021). Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Action Spectacle, Counterclock, DIAGRAM, Iterant Magazine, Gasher, La Vague Journal, Petrichor, Literary North, SWWIM, and elsewhere. Kylie is the Book Reviews Editor for

Green Mountains Review

, Editor-in-Chief of

Mount Holyoke Review

, and a Frances Perkins Scholar at Mount Holyoke College. For more, visit www.kyliegellatly.com 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

To be honest, I sent the poems out as a manuscript just to see what would happen. I had spent the summer building up these visual poems, about 45, of them, and was about to start my first semester in a new program. It made sense to stop working on them as I was preparing for the academic year, so I bound them up as a “manuscript” and sent them to Finishing Line Press—which I had had my eyes on as a good starting point. They accepted the manuscript within two days and that was that. For most of the school year, I really didn’t have to think about it at all, but once pre-sales started, right in the middle of the spring semester, things got crazy. My understanding of these poems is completely retrospective, as they were written over a couple months—months that were absolutely teeming with change and importance—and I can only look back and draw connections. I’ve learned a lot about my writing and process from this experience and know more of what to expect the next time around.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or nonfiction?

I’ve been reading mostly poetry for some years now, though when I started writing I was writing short fiction. I was in a fiction workshop once and was basically told: “we can’t do anything with this: this is poetry.” What draws me in so close to poetry is its boundlessness. I feel pulled toward art in which the narrative is not the point of the work, when there is no cohesive answer to “what is it about?” I need that freedom, since creativity, for me, has always been a process of discovery.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Because I am working in found/collage form, there is a slight urgency to getting something, once it has taken form, glued down. Otherwise, the tiny, precariously placed scraps of paper with each word (or letter) on it become subject to breeze through an open window or my cat jumping on the desk. That being said, it can take weeks before the scraps start to come together into a poem—though once they begin to, it happens rather quickly. The unique thing about the process is that, once the collage is glued and the poem is in it, there is no revision! No way benefits to workshopping a poem beside asking what I can do differently next time. There was one poem that I tried revised, which was actually very very cool. I had left a good deal of space between each line, so ended up adding 2-3 lines between each original piece, making sure each new line picked up where the previous left off and could also segue into the original predecessor. It grew from 8 lines to 15.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The impetus of The Fever Poems was to make cards I card send to friends. I cut up a couple magazines then found something more interesting—a book that I was tired of holding onto for sentimental reasons that I could turn into something else. It had illustrations too! I made one card with a few words cut out and pasted onto it and then suddenly was writing full lyric poems in that way. Also suddenly, there were more than forty poems. I am working on a new project now that is very much a self-contained book project, replete with an extensive reading list for research and piles and piles of notes on what it aims to explore.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Definitely. I found them more useful when I was writing “free form” and not in this new collage approach, because I could edit while I read and would learn more about the poem each time I read for an audience. From readings, I learned to compose out loud and imitate the experience while it’s being written, which offered a noticeable change to my writing as soon as I started doing it. I have a background in music and always got so much out of playing for an audience. Every performance showed me something I had never heard before. The anxiety or excitement of having an audience can be so altering to one’s perception.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’ve often questioned whether abstraction, in my own work, is a way around craft, which I’m sure comes from an insecurity about my non-traditional education. One concern, in particular, that comes up when working with found poetry, is how the poems engage with the source text or what it means to be working with a source text. For me, I’m interested in how to break narrative, so the idea of butchering a book is very clear for me. From there, it’s which book and why.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Huge question, one I can only answer in terms of myself. I write out of a need to communicate, express, and relate, operating on internal beliefs that I otherwise could not do so. On the other hand, so much of my life has been informed by artists and access to the arts, that creating, myself, is one of the many ways that I can see that kind of availability continue.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I haven’t had much experience working with an editor. This book is made up of found/collage poems, which makes them unchangeable beyond whether or not to include the piece. Mostly what I have found with editors is validation—most journals do not consider this sort of hybrid work and finding ones that not only print it, but encourage and foster it, is very exciting.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I have a clipping above my desk that acts as advice:

“I am a procrastinating writer an unnecessary writer an undisciplined writer a blocked writer a distractible writer a perfectionist writer a very slow writer who spends most of their time teaching and parentings and washing groceriesa writer who writes under the conditions of late Western capitalism, now in new global pandemic form.” — Andrea Lawlor

Andrea is also a professor of mine and I receive advice from them on the regular that can be more tailored to my circumstance.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I work in the mornings, which can last all day or not. Some days I read before sitting down to write, others it’s reversed. Depending on where I am with one particular poem, “sitting down to the desk” may not mean writing at all. For example, these past few days I’ve spent working on a collage and spending time with the visual aspect of the poem, which sits in pieces, unfinished, off to the side. Sometimes, working with the collage is a step I turn to if I feel I don’t understand where the poem has gone. What can the visual aspect reveal or direct in what is already at work?

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Besides spending more time with the visuals of the poem, I try to read more. It usually means I’ve been writing too many emails and don’t have the rhythm in my head. It’s a foolproof antidote, unless I’m between books or have, what I call, reader’s block.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I recently went for a hike in the woods and I came upon a horse farm just as it started raining. I had to stop and sit down because of how overwhelmed I was by the smell and how transportive it was. I grew up across the street from a house with horses and extensive gardens, where my father would take me for walks every day, and at that moment it felt like I had not smelled that combination since then.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I curated a playlist that I can write to, the three main ambassadors of which are Alice Coltrane, Phillip Glass, and Sleep.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve been very lucky in getting to know a lot of the artists and writers who inspire me most. I lived down the street from the Vermont Studio Center for a number of years and never took for granted the people I was coming into contact with, meeting, and getting to know. The prowess and genius of their work in everyday life made such an impression on me. It is the encouragement I found in that community that motivated me to take myself more seriously in my writing—which has made all the difference.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a screenplay.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve dabbled in a number of occupations—park ranger, cook, data processor, bookseller, etc. I recently went back to school to study English and am now an unemployed student… so I guess we’ll see.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was raised by artists and thus grew up believing that one I needed to find an outlet for expressing myself — which I understood to mean or else you won’t be able to. It took many years and trials across the disciplines to find that poetry—the manipulation of the very thing I felt was holding me back—was the most freeing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve finally read Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties and I am blown away. Also, forever changed by Ross Gay’s Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, which I also finally read this year.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m taking the methods I learned in creating The Fever Poems and directing them into a deeper, more conceptual project, that uses a selection of cookbooks to reflect on my time working as a butcher in fine dining, while directing the language into addresses of gender, agency, the individual, and the insidiousness of the anthropocene. The visual and research components of this project have changed my processes drastically and I feel that I’ll be working on this for a long time.

January 15, 2022

Angela Hume, Interventions for Women

ruled by appetite

i wanted to write

a truth from the

whole

of the scratched-

out line

between what you

call mine

what counts as

your body

and what’s a

depository

for Roundup Teflon

sphenol A

Bay Area, California poet and editor Angela Hume’s [see her 2016 “12 or 20questions” interview here] second full-length poetry title, following Middle Time (Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2016) as well as a smattering of chapbooks [see my review of her most recent here], is Interventions for Women (Omnidawn, 2021). Through an accumulation of six sequences, themselves composed as accumulations of short, lyric bursts, Hume sketches one phrase on top of another, writing on the impact of the world on women’s bodies, from climate to agriculture, settler colonialism and sexual violence, white supremacy to genetic engineering on food, writing wave upon wave of interlocking, interconnected wave of assault upon the physical and spiritual body. Set in sections of extended, accumulative fragments—“may the human animals,” “interventions for women,” “drowning effects,” “you were there,” “meat habitats” and “say no”—each section opens with a brief introduction of sorts, situating the poem-section in very specific temporal and subjective spaces; she sets the scene, as it were, allowing her lyrics to open and expand from that singular point. The section “you were there,” for example, opens: “Oakland and Point Reyes National Seashore, California, 2017-2018. // I wrote this poem after the April 15, 2017, Berkely community demonstrations against white nationalist and neo-Nazi groups who staged a rally at Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park, and also at the end of the 2011-2017 California drought.” The poem itself, begins:

out of the drought

and the dead land

we came undone

cortisol hypotension

Maalox adrenaline

beneath a shrill

unblinking cerulean

we’re all writing

this poem i join in

Her poems accumulate, phrase upon phrase, but exist almost as Jenga-towers: to remove one word or one phrase would be to tear the whole structure apart. The intricacy of her point-by-point is overshadowed, slightly, through the ease and flow of the lines, allowing her lines to sit on the page as a series of stretches, but amass in the readers’ attention as a singular structure.

Her poems accumulate, phrase upon phrase, but exist almost as Jenga-towers: to remove one word or one phrase would be to tear the whole structure apart. The intricacy of her point-by-point is overshadowed, slightly, through the ease and flow of the lines, allowing her lines to sit on the page as a series of stretches, but amass in the readers’ attention as a singular structure. Through these brief introductions to each section, Hume provides context and even boundaries to her poem-sections, stretching out her lyric across a broad spectrum. The communal aspect of the writing, “i join in,” as Hume offers, connects the work in Interventions for Women to a far larger movement of resistance, something comparable to, for example, Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas(Graywolf, 2017) [see my review of such here], as well as works composed-in-resistance to the Northern Gateway Pipeline in Burnaby BC, including Christine Leclerc’s Oilywood(Nomados Literary Publishers, 2013) [see my review of such here] and Stephen Collis’ Once in Blockadia (Talonbooks, 2016) [see my review of such here], and, more generally, various pieces in Nyla Matuk’s Resisting Canada: An Anthology of Poetry (Signal Editions/Vehicule Press, 2019) [see my review of such here]. The writing exists consciously and deliberately alongside and as part of a far larger movement and structure of resistance, offering support, critique and weight and a call-to-action. As the title sequence, second of the six, opens:

Cambridge, Massachusetts, North Branch and Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Oakland, California 2019-2020.

I wanted to write a poem about how the industrial food system alienates feminized people from their bodies, and how this alienation requires, colludes with, an exacerbates economic and racial oppressions along with the exploitation of animals. And about how the industrialization of agriculture has been more or less coextensive with the development of modern institutions and technologies for the surveillance and control of the intimate body activities (eating, fucking, reproducing) of women and girls.

While “interventions for women” addresses global food systems and hunger, along with the state and NGO approaches to naming systemic failures, its focus is on settler food production and eating in the United States. There is much more to be said about the violence of the food system internationally, not to mention everything else.

I wanted to say that I intend the title ironically.

January 14, 2022

Three poems for Heather Spears

1.

Between fluidity,

attentive cells, an illustrated

pantomime. She captured medical standards, poetry

readings, courtroom action. The face

of stillbirth. Bedside

vigils. Hand, hand,

fingers,

thumb. A blueprint for intimacy,

against a vast

seduced indifference.

2.

Such papery fields: the animation

of a poetry panel, gestures

behind the open window. This filament of lines

our only access. An elusive quality,

from which there is only memory.

3.

My mis-pronounce of Van Gogh, responding

with her pulsing Khokh, hard-pressed

the guttural Dutch. She rolled

her eyes. She

savoured, stared. She handed

me my portrait. Here.

January 13, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Eugene K. Garber

Eugene K. Garber

has published seven books of fiction, most recently

Maison Cristina

. His fiction has won the Associated Writing Programs Short Fiction Award and the William Goyen Prize for Fiction sponsored by TriQuarterly. His awards include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the New York State Council of the Arts. His short fiction has been anthologized in The Norton Anthology of Contemporary Fiction (1988), Revelation and Other Fiction from the Sewanee Review, The Paris Review Anthology, and Best American Short Stories. He is the author with eight other artists of Eroica, a hypermedia fiction for web.

Eugene K. Garber

has published seven books of fiction, most recently

Maison Cristina

. His fiction has won the Associated Writing Programs Short Fiction Award and the William Goyen Prize for Fiction sponsored by TriQuarterly. His awards include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the New York State Council of the Arts. His short fiction has been anthologized in The Norton Anthology of Contemporary Fiction (1988), Revelation and Other Fiction from the Sewanee Review, The Paris Review Anthology, and Best American Short Stories. He is the author with eight other artists of Eroica, a hypermedia fiction for web. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The first book, Metaphysical Tales, affirmed my perception of myself as a serious writer. It won the Associated Writers Award for Short Fiction and contained a lovely foreword by Joyce Carol Oates. My most recent book, Maison Cristina, continues quite definitely the element of mythography in the first book, a lifelong preoccupation. The difference may be more in variety and intensity than in any radical reorientation.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I did dabble in poetry, but it was fiction that caught my imagination when I was a teenager—southerners mostly, Thomas Wolfe, Faulkner, Eudora Welty, but also Dubliners, and Portrait of the Artist. I imagined writing something like that.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

In my early days as a short story writer, after failed attempts to write a novel, the stories came quickly and were born fully fashioned. As I essayed longer fictions, rewriting and revising became more necessary. My latest novel, Maison Cristina, required three starts before getting off the ground.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Even for novel length works I have always tended to construct interrelated sections rather than lay out a long scheme—Bach vs. Mahler.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy reading my works aloud. I have been fortunate enough to receive praise for my prose style, even though it exhibits marked changes in register. So I feel confident as a reader.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t think I could be called a novelist of ideas like, say, Huxley or Richard Powers, but ideas are very important to my work. Lurking within each work, or even explicitly, is the question of what’s really out there. Have we constructed everything or is there an implacable reality out there that we always butt up against? In my latest work, Maison Cristina, the central question is this: can we fashion our reality by telling stories?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Some critic cracked about novels laden with social criticism that the novelist had sold his art for a pot of message. I do agree that “tract” novels built explicitly to convey a message are questionable. Roth has written a couple of these. My own work might be criticized for taking too little account of repeated and current malaise in our culture. I favor aesthetic values over social critique. I might even be tempted to claim that the best way to critique cultural deformity is to confront it with aesthetic power.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have a friend, my fiction writing Double, you might say, who has the uncanny ability to penetrate my writing and show me what’s wrong. There is no other “editor” whom I trust to anything like this degree.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I always found Faulkner’s “kill all your darlings” the best advice for getting rid of sludge, self-indulgence. Odd, since he himself was hardly a spare writer.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to novels to collaborative works)? What do you see as the appeal?

As I mentioned before, I am not a long-distance runner. My longest work to date, the current Maison Cristina, is, to continue the metaphor, a relay race with the baton passed numerous times. It’s the only way really that I know how to work.

A while back I collaborated with eight other artists on a hypermedia fiction for web, Eroica. It is currently being revised for republication. It is divided into three parts—Vienna, the Amazonian basin, and a gothic house on the Hudson River. The work with the other artists was enormously invigorating and demanding. It led to the three novels of my Eroica Trilogy.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I used to write for two hours each morning—this over a period of years. Later, institutional duties required me to carve out irregular blocks of time. Now my duties as a caregiver also require stealing time when I can.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

My writing gets stalled not because I lack invention but rather because I invent wrongly. I end up in a hole. I have to climb out and reimagine. I find I can do some of this reimagining at almost any slack moment, e.g., when swimming.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Home would have to be the South of my early childhood. Baking biscuits.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

From time to time I find inspiration in all the other arts. I once wrote a long novel using motifs from Mahler’s Second Symphony. It was a failure but not because of the Mahler. In Maison CristinaI found inspiration in the visual arts. But McFadden is right. It is the word as beautifully deployed in the works of previous writers that is inescapable.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

As a longtime student of literature, from grade school through graduate school, I have inevitably been exposed to and borrowed from a great variety of writers. A moment of freedom that has informed all my work since was reading the work of Robert Coover and understanding that literary fiction is unstable and for that very reason amenable to marvelous invention. To this day I would call myself a fabulist.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

This answer would serve also as an answer to your last question below. I would like to complete a series of very short parable-like works that follow The Stations of the Cross in two very different versions: the Christian ritual usually performed during Lent and Barnett Newman’s fifteen panels entitled, formally I believe, Eli Eli lama Sabachthani. On the one hand stands the affirmation of salvation and on the other the ultimate cry of abandonment and existential suffering. I keep feeling that somewhere in the space between these two lies the very essence of human hope and human despair.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I once tried ardently to learn to play the piano. It didn’t happen. But to this day nothing can touch me as deeply as music. Recently I went to a rare performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem. I warned my companion that I would be OK until it came to the “Sanctus” and then I would break down. I was right.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I can’t answer this except to say that I grew up with a mother and father and with a paternal grandmother who held literature in the highest regard. They read to me. They quoted famous passages to me. At one point my mother had to ask my grandmother to stop reading Oliver Twist to me. It was emotionally too charged.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Richard Powers’ The Overstory. Without seeming stubborn or doctrinaire, I hope, I find The Seventh Sealto be the greatest film for me. And other of Bergman’s films rank very high. I want to watch again Buñuel’s Discreet Charms of the Bourgeoisie having read a fascinating review of Thomas Ades’ opera based on the film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Please refer to 16. Above.

January 12, 2022

Joshua Nguyen, Come Clean

I am afraid of being a light-year

because I fear what lies in the dark.

I fear the dark, because it can be so easy to lie.

For instance: when I said I needed some space,

I hoped you would’ve read the space

between my breath as a cry for more attention.

(“An Argument about Being Needy while / Underneath Binary Stars”)

Winner of the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry, is Vietnamese American writer Joshua Nguyen’s full-length debut,

Come Clean

(Madison WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2021), a collection that, according to the cover copy, “compartmentalizes past trauma—sexual and generational—through the quotidian. Poems confront the speaker’s past by physically—and mentally—cleaning up. Here, the Asian American masculine interrogates the domestic space through the sensual and finds healing through family and in everyday rhythms: rinsing rice until the water runs clear, folding clean shirts, and re-creating an unwritten family recipe.” The poems of Nguyen’s Come Clean exist as an accumulative memoir of trauma and growing up, writing via a variety of poetic forms (including haibun, which is always good to see), something reminiscent of Diane Seuss’ recent frank: sonnets (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], a collection that also explored the accumulative poetic memoir via poetic form (hers being, for that particular project, exclusively the sonnet). Nguyen writes on culture, conflict, abuse, sexuality and masculinity, and to a younger brother, composing poems that are self-effacing and embracing failure, even while examining trauma and the ways in which one can unpack, and move beyond. As the poem “A Failed American Lục Bát Responds” asks: “Can I be read from / fathers who don’t speak, who find love / in Vietnamese fantasy, / in warriors trying to find their way home? / O monosyllabic birthplace, / can I self-colonize myself, / be the fusion the world doesn’t want to see?” These poems are emotionally raw, performative and lyrically sharp, carefully crafted to embrace a lyric that punctuates and punches without holding back.

Winner of the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry, is Vietnamese American writer Joshua Nguyen’s full-length debut,

Come Clean

(Madison WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2021), a collection that, according to the cover copy, “compartmentalizes past trauma—sexual and generational—through the quotidian. Poems confront the speaker’s past by physically—and mentally—cleaning up. Here, the Asian American masculine interrogates the domestic space through the sensual and finds healing through family and in everyday rhythms: rinsing rice until the water runs clear, folding clean shirts, and re-creating an unwritten family recipe.” The poems of Nguyen’s Come Clean exist as an accumulative memoir of trauma and growing up, writing via a variety of poetic forms (including haibun, which is always good to see), something reminiscent of Diane Seuss’ recent frank: sonnets (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], a collection that also explored the accumulative poetic memoir via poetic form (hers being, for that particular project, exclusively the sonnet). Nguyen writes on culture, conflict, abuse, sexuality and masculinity, and to a younger brother, composing poems that are self-effacing and embracing failure, even while examining trauma and the ways in which one can unpack, and move beyond. As the poem “A Failed American Lục Bát Responds” asks: “Can I be read from / fathers who don’t speak, who find love / in Vietnamese fantasy, / in warriors trying to find their way home? / O monosyllabic birthplace, / can I self-colonize myself, / be the fusion the world doesn’t want to see?” These poems are emotionally raw, performative and lyrically sharp, carefully crafted to embrace a lyric that punctuates and punches without holding back. As much an underpinning examining trauma, there is a tenderness that comes through the lyric as well, such as the second stanza of “American Lục Bát for Peeling Eggs,” that reads: “Love, you are old / enough now to unfold the skin / back on these white shells.” Or the opening lines of “March 4th,” set at the opening of the collection:

Tell the priest to wait outside the hospital room.

I am wiping the blood of his handsome head.

My son must be presentable to the world.

My son, the world will try to bury you.

January 11, 2022

Spotlight series #69 : Sara Renee Marshall

The sixty-ninth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall.

The sixty-ninth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis and poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan.

The whole series can be found online here.

January 10, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ryan Dennis

Ryan Dennis is a former Fulbright Scholar in Creative Writing and has taught creative writing at the University of Education, Schwäbisch Gmünd and the National University of Ireland, Galway. In addition to appearing in various literary journals such as The Cimarron Review, New England Review, Fourth Genre, and The Threepenny Review, époque press published his debut novel

The Beasts They Turned Away

in March 2021. Ryan is a syndicated columnist for agricultural print journals in four countries and two languages. In 2020 he founded

The Milk House

, an online initiative to showcase the work of those writing on rural subjects in order to help them find greater audiences. More information about Ryan can be found at penofryandennis.com.

Ryan Dennis is a former Fulbright Scholar in Creative Writing and has taught creative writing at the University of Education, Schwäbisch Gmünd and the National University of Ireland, Galway. In addition to appearing in various literary journals such as The Cimarron Review, New England Review, Fourth Genre, and The Threepenny Review, époque press published his debut novel

The Beasts They Turned Away

in March 2021. Ryan is a syndicated columnist for agricultural print journals in four countries and two languages. In 2020 he founded

The Milk House

, an online initiative to showcase the work of those writing on rural subjects in order to help them find greater audiences. More information about Ryan can be found at penofryandennis.com. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having The Beasts They Turned Away published now meant that I could formally try to elbow my way into the Irish writing community (the country I live in now). It's a card I can flash to guards at the door and they have no choice but to let me in. Other than that, and additionally knowing that my work was out in the world now, it doesn't seem much different. I still feel like there's a chip on my shoulder, and that I have something to prove.

The Beasts They Turned Away is different in that it is set in an Irish context, while my previous work was based in the US. In some ways, it was the same story--the decline of the family farm and its consequences--but putting it into another culture made the project feel entirely fresh and exciting for me.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Having taught creative writing, I have witnessed that most young writers are like myself: they come into the classroom to learn about fiction because they find it more exciting, and then later started dabbling in nonfiction. I found it easier to write and publish nonfiction, but have still enjoyed the particular challenges of fiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Starting a project is fine for me...it's the thousand-plus hours spent on a book that wears me down. I hate first drafts. No enjoys vomiting, and often for me that's what it is--I force myself to get as many words on the paper as possible so I can go back later and try to find the story within all the shit. On the other hand, I love editing. It feels like putting a puzzle together (which I actually don't enjoy in real life, but sure).

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For the three book projects that I've put work into (the first unpublished novel in my twenties, the recently published The Beasts They Turned Away, and the current nonfiction book) I've always known they would be books. For whatever reason, every story I wrote turned out to be just that. For the nonfiction project I'm working on now I do borrow from earlier essays. I guess that's autoplagiarism.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy a crowd. It's a way to connect with readers directly, as well as sometimes try to convince them that your book is good before they have a chance to make up their minds themselves. That can be important when you're trying to peddle nonconventional fiction like I am.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Nearly all of my writing--and certainly the reasons why I write--relate to one specific concern, and that has to do with the loss of family farming. I've always pursued what it means to be a small farmer in a modern context, regardless of what else is happening around me. For all I know, there can be a pandemic going on, and I probably won't write about it.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's funny that the day after you publish a book your insight into the world is suddenly much more valuable than it was the day before. I tend to reject the notion of writer as sage. However, that being said, and perhaps both because of the type of people who tend to write, and because of the expectations placed on us, I think writers do tend to live an examined and conscious life. Or at least more than many other types of figures that have platforms.

Does The Writer (with a capital "W") have a specific responsibility towards society? Maybe not. But I would argue each individual, regardless of our occupation, has an obligation to works towards a constructive cultural environment.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I was very lucky that the editing team with époque press were great. They made the story better, which was all you can ask of any editor. They even did the hard work of having to convince me of certain changes, which in the end were good ones. In total, I think the editorial relationship is dependent on both sides having the same vision for the piece, which is imperative.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I heard Salman Rushdie speak once. He said that sometimes you have to teach readers what type of animal you are, and it can take several books to do that. I feel that applies to my publishing career so far, since The Beasts They Turned Away is written in a singular type of style that is not for everyone.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to personal essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don't find any problems going between fiction and nonfiction. I haven't written poetry in almost ten years, which is probably a shame. I think, in particular, trying to write poetry has informed my writing in other genres. In particular, I think it has sharpened by attention to language and the rhythm it holds. In the same way, I find that my fiction gets a better reaction from poets.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Sure, try to make me feel guilty.

Like everyone, the non-writing aspects of life are always shifting, so I have to adjust around that. In the best of times I have a routine, and in the worst of times I don't. Ultimately, I try to set myself hourly goals every week. I find that putting a daily or weekly word count on progress can sometimes effect it, whereas if I'm giving myself credit for simply sitting down at the desk, I'm less likely to feel the pressure. On days I don't have to work anywhere else I try to open the notebook right after breakfast, as the morning is usually the best time for me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Growing up, the repetition of farming acts, from feeding heifers to fieldwork, always helped free up my mind and allowed it to wander in useful ways. Now that I'm off the farm, sometimes I need a good and hard session in the pub just to clear my mind and start fresh again. Note, however, that neither I nor the health board are endorsing this tactic.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cow shit. See answer above.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

The type of people I write about inform my writing the most. These folks are often from rural stock that have seen a struggle or two and have a story that needs to be told. Whatever they have went through is harder than me writing about them, and I try to remind myself of that.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love Cormac McCarthy. In my opinion, he is the preeminent figure in English-language writing. Sometimes I open up Blood Meridian to a random page just to pump me up. It made me believe in the possibilities of the English language, and showcased just how much intensity can be seething on a page. He won't get a Nobel Prize, but I believe he deserves one.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I was going to say win a major award, but now I think the better answer is to effect positive change in the world.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

The answer to both would be to farm. In the end, the reasons I didn't were partly due to its poor economics, and partly due to what I might be losing out on if I did. I still have fancy notions of finding a way to break even with a small herd or a couple hundred acres, but that's easier said than done these days. Still, most of my identity is tied up into farming, and for now the only way I can deal with that is to write about it.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The first story I wrote, at the age of 14, was about the area myth of the Hairy Women of Klipnocky. It was published in the Canaseraga Creek Criar, the monthly flyer for the residents of the 500-person town. It wasn't good, because it was written by a 14-year-old, but the locals really enjoyed it because it was essentially a narrative about them. The experience taught me the value of telling someone's story and giving voice to their experience. Growing up on a farm, I saw that the story of people like my family and neighbors weren't being told, so I sought to fill that gap.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Stoner, by Jonathan Williams. It moved me to tears, which seldom happens. The last great film was Happy as Lazzaro , an Italian movie from 2018. Whatever it is, sometimes the Italians come out with something extremely special on the screen.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm working on a memoir-based nonfiction book that seeks to explicitly pinpoint the the political moments that ruined the family farm in the United States, as well as show the consequences of those decisions by telling the particular story of our family. I was fortunate enough to recently receive a Writer-in-Residence post at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth to help me carry out this project.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

January 9, 2022

Kate Siklosi, leavings

Comprised of seventy-three large full-colour photographs of visual poems comprised of a combination of object (leaf, bark, branch) and text, is Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi’s full-length debut, leavings (Malmö, Sweden: Timglaset Editions, 2021). leavings is a collection of visual pieces composed through a combination of printed text, visual poems and letraset combined with leaves, twigs, branches and fir to reveal, in close detail, the physical interactions between nature and language, and the impact of absolute brevity. In her piece “Hot and Bothered: Or, How I Fell In and Out of Love With Poetic Conceptualism” at The Puritan (posted May 1, 2017), she writes on “the trajectory of my personal love affair with conceptualism” through looking at M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!(The Mercury Press, 2008) [see my review of such here] and Jordan Abel’s Un/Inhabited (2014) [see my review of such here] and Injun (2015) [see my review of such here], writing that “Sure, in some sense, it is ‘enough’ to screw around with language and create art that floats inside a beautiful ether. But in the face of the continuing projects of settler colonialism—to which we are all subject, to lesser or greater degrees—I could no longer ignore the ways in which authors consciously use and abuse poetic material in their work.” Through such, she writes of both the requirements of properly acknowledging the materials with which she works, as well as a deeper purpose than simply messing about with language. As she writes: “in revealing the (mis)use and arbitrariness of language, and of his-tory writ large, social activism and aesthetic praxis are fused. Their poetic labour combines conceptualism’s interrogations of language and symbolic representation with a persistent concern for equity and social justice.” She writes of, as her endquote by bill bissett offers, a “shared fragility,” as well as a particular kind of interconnectedness. One side of her work could not exist at all without the other.

The pieces are structured in four titled sections, with a single large image per page: the twenty works of “a leaf,” the twenty-three pieces of “a leave,” the eleven pieces of “a left,” and the nineteen pieces of “a mend.” By section titles alone, Siklosi’s quartet hints at an echo of bpNichol’s infamous eight-line poem etched into the concrete of the Toronto lane that now shares his name: “A / LAKE / A / LINE / A / LONE [.]” Just as in Nichol’s poem set in concrete, Siklosi’s poems are uniquely physical, and deliberately temporal; the delicate nature of some of these pieces suggest that most, if not all, might no longer exist in the forms shown in the photographs, leaving the photograph as both framing and document of an object that can’t easily, or ever, be archived. Is her purpose, then, through the exploration, the object or the documentation? There is something fascinating in the way the pieces in leavings also suggest an approach in tandem with her found materials. These pieces exist, one might say, in collaboration between Siklosi and her materials (leaves, branches, etcetera), as opposed to her simply dismantling and repurposing whatever materials she may have found as part of her walks (her acknowledgments include a “Thank you to NourbeSe for our ravine walks, on which many of these leaves and thoughts were collected.”). Instead, Siklosi appears to respond, from her collaborative corner, as a way of shaping to and around the materials-at-hand. It is no accident, I would think, that her dedication reads, simply: “for the land, our wisest poet [.]” As she writes to preface the collection:

a life is composed of leavings: the remains of crusts and skins, the remnants of night in a dawn sky, the residue of mourning, loves too deep and too shallow, the hard words left unsaid, the time taken, the dust in our tracks. in our tiny expanse, things pass and things grow. we kill and we cultivate. we hurt and we mend. we pick up the pieces and create. we do better and we fail. we thread ragged beginnings from the trodden decay of our pasts. beginnings still. we collect, windswept and tired, in piles against a fence. in our shared fragility, we quilt a being, warm and enough.

Over the past few years, Timglaset Editions has emerged as one of our most important, and even most visible, publishers of concrete and visual poetry, producing numerous bits of ephemera along more substantial trade editions, including Amanda Earl’s landmark anthology Judith: Women Making Visual Poetry (2020) [see my review of such here], a book that Siklosi’s work was also included in, and this book is stunning for the delicate care clearly evidenced through productions. After seeing Siklosi’s work for so long in smaller publications, such as her wealth of chapbooks and pamphlets over the past few years—po po poems (Ottawa ON: above/ground press, 2018), may day (Calgary AB: № Press, 2018), coup (Calgary AB: The Blasted Tree, 2018), fragile armies (England: Penteract Press, 2018), 1956 (above/ground press, 2019), She Bites (Wilmington, NC: Happy Monks Press, 2019) and 6 feuilles(Toronto ON: nOIR:Z 2019)—it is interesting to see her work stretch itself across such a larger and broader canvas. Given she has a further collection forthcoming in 2023 with Invisible Publishing, a manuscript combining text and image, one can only imagine this as simply our introduction as readers to a range of thinking that she has been engaged with for some time, merely hinted at through all she has published so far.

January 8, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anna Dowdall

Anna Dowdall

was born in Montreal and recently moved back there after living all over North America. She's been a reporter, a college professor and an urban shepherd, as well as other things too numerous to mention/best forgotten. She first tried her hand at YA fiction. She was nominated for the US Katherine Paterson YA prize and for Canada's Arthur Ellis Award in the unpublished category. After being told by an agent that her words were too "big" for YA, she switched to adult fiction. Her novel,

APRIL ON PARIS STREET

, is a bittersweet literary mystery tinged with black humour. Her well-received previous books include

AFTER THE WINTER

and

THE AU PAIR

.

Anna Dowdall

was born in Montreal and recently moved back there after living all over North America. She's been a reporter, a college professor and an urban shepherd, as well as other things too numerous to mention/best forgotten. She first tried her hand at YA fiction. She was nominated for the US Katherine Paterson YA prize and for Canada's Arthur Ellis Award in the unpublished category. After being told by an agent that her words were too "big" for YA, she switched to adult fiction. Her novel,

APRIL ON PARIS STREET

, is a bittersweet literary mystery tinged with black humour. Her well-received previous books include

AFTER THE WINTER

and

THE AU PAIR

. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I don’t think After the Winter changed me much, except that it was like finding a key to a lock, especially after the good reviews. April on Paris Street, coming out this fall, is definitely a game changer. I took deliberate and substantial risks with the mystery genre, with an unusual plot, unusual roles for the female characters, black humour and even some postmodern themes/embellishments you can take or leave. The legendary Guernica Editions picked it up and I’m still pinching myself.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I like stories, to tell and to read and listen to. But poems can be stories too. I’m too lazy to focus on non-fiction, all that fact checking.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write fiction the way I used to write government policy reports. Haha. But true. Lots of careful prep and planning, and then the writing is smooth. It might take me 6 months to churn out a polished first draft, and 2-3 months for reworking. But several months of planning and tergiversating might have gone into that.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A very simple idea, usually borrowed from a book or film or even real life, and then I drag it wildly off in my own direction. For example, the germ of the idea for April on Paris Street came from an interest I had in combining Montreal and Paris as settings in a book. I just thought it would make for a fun read. Like a tale of two cities, I said to myself—and the filing cabinet of my mind promptly exploded with doubles, doppelgängers, splits, masks, twins, duplicates, impersonations, dual solitudes and other unreasonable facsimiles littering the place. I’ve pretty much described the symbolic structure of the book, but it’s also a suspenseful Thelma and Louise style mystery adventure in which, however, women come out on top. The Au Pair, my second book, was based on the urge to retell the story of the sketchy relationship between Henry and William James and their sister. And After the Winter was the answer to the question, how good could a disguise be?

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

With my fake extravert face in place, I tell myself I like meeting my readers. Twice, at Word on the Street Toronto, I actually sold out my books, and the competition there is pretty stiff. I was like one of those telemarketers, or that terrifying pushy parent we all remember from our child’s figure skating.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I write semi-literary mysteries set in Quebec. My preoccupations include women living in a man’s world and what happens when women come up against the justice system. And then, since I like to plumb commercial fiction conventions in relation to these oh-so-lofty themes, how much can I get away with, aka how stretchy are the conventions?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To survive.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

If you mean a freelance editor, versus the publisher’s editor(s), I’ve never used one. I think I work well with publisher’s editors, but you shouldn’t be asking me, you should be asking them.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t get your writing ideas from the internet. Especially memes, gifs and short sentences in quotation marks attributed to Hemingway and Stephen King.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

In active writing mode, I write according to a schedule. Monday to Friday, all morning. When I worked FT, I devoted a full day off every week to it.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t really get stalled. Even if I don’t feel inspired, or the cat woke me at 5, the little jerk, I tell myself it is what it is and carry on. Write you must.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Heat-scorched zinnias growing by the back door. Also burnt toast (we had one of those little manual flip toasters.) In keeping with the spirit of the question, I’ll add that the echoing halls of our post-war box were haunted by these odours.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Books, mainly, and of course let us not forget my demons.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

It’s hardly a coherent group, but Ursula Curtiss, Mervyn Peake, Rebecca West and, especially, Constance Beresford-Howe. It drives me crazy that we Canadians don’t read more Canadian books. We are brainwashed by American mass consumerism. I feel choosing insistently Canadian settings is an act of resistance, but it probably costs me readers. I’m really glad that Crime Writers of Canada has a new book prize, sponsored by the family of Howard Engel, for a mystery set in Canada. Someone had to do it.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want to go to the Frankfurt Book Fair and talk my way into film and translation deals by channeling my inner annoying figure skating parent as per question 5.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I have been a practical nurse, university prof, reporter, graphic artist, translator of Harlequin romances, horticultural advisor, book conservationist, pilot, union thug, literary pundit, film extra, baker and policy wonk, and I’m sure there are others things I’m forgetting, so I feel I’m good.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

At a guess, my runaway imagination and my zinnia-growing mother’s frustrated ambition to be a writer.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m on a BIG Anthony Trollope kick right now. I loved Phineas Finn. I might like The Eustace Diamonds even more when I get to it.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I just completed the first draft of my 4th book, but have set it aside to concentrate on pre-launch marketing for April on Paris Street. So right now I’m working on things like luring people to Netgalley to provide early reviews. Did you know that books up for review on Netgalley are free to read? As for the mysterious book 4, suffice to say that if you like the Sister Pelagiaseries by Boris Akunin, you will like this one. Also, I have strayed into magic realism. Magic realism crime.

January 7, 2022

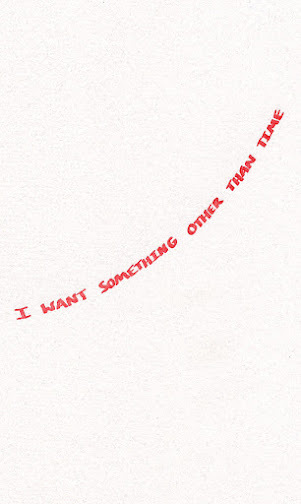

Lewis Freedman, I Want Something Other Than Time

I Want Something Other Than Time

I want to feel ok

right here. I want to

say I’m not wasted

in the choppy paint of

thinks itself, & a dreamy

obedience to the music proceeds me.

As I’ve said before, a dream might not be

built of representation.

So cheap a ransom where the accident

is almost repeated, is an interior plane of

expiring breath, hello & then let go.

I think the devil’s in

going back to a withheld meaning &

letting its deferred presence

prescribe a place we’ll never get to.

We’re assuming then that

this is one of them, uh,

special clovers, abandoned,

like all things here, to the hype

of liberation.

O mortar get me higher,

the loud voice goes,

move away

from the shore.

I’m fascinated by the echoes that ripple across the sixty-four poems that make up Lewis Freedman’s second full-length collection,

I Want Something Other Than Time

(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021), a book that follows a debut I clearly missed seeing, (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016). Each poem in I Want Something Other Than Time is self-contained (each poem set on a different, single page), but also all share the same title, something that this collection shares with Denver poet Noah Eli Gordon’s Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down? (New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]. There is something I’ve always found curious about the repeated-title, allowing poems to echo each other and accumulate, even as they simultaneously exist as singular pieces. After a while, the differences and the echoes shift, and become more prominent (reminiscent, slightly, of the character Auggie’s daily photographs in the Paul Auster-writ 1995 feature length film, Smoke). Freedman’s poems speak through physical and cognitive boundaries, working to stretch beyond into further connection, all while articulating from a kind of insularity. “I get up feeling / numb,” he writes, to open one of the poems further in the collection, “but not really / numb, more like I get up / feeling contempt for a / numbness.” Or, a page prior: “From the body cave / to the body boundaries, / we are immersed in the / circumstance of holding our / selves in place.” The meditative lyric that Freedman writes is deeply evocative, writing a kind of dislocation through the self that is intriguing to work through. Or, as the first poem in Freedman’s collection begins: “The aim of this writing / is to show that / I does not disappear. / Even when I disappear I / does not disappear.”

I’m fascinated by the echoes that ripple across the sixty-four poems that make up Lewis Freedman’s second full-length collection,

I Want Something Other Than Time

(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021), a book that follows a debut I clearly missed seeing, (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016). Each poem in I Want Something Other Than Time is self-contained (each poem set on a different, single page), but also all share the same title, something that this collection shares with Denver poet Noah Eli Gordon’s Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down? (New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]. There is something I’ve always found curious about the repeated-title, allowing poems to echo each other and accumulate, even as they simultaneously exist as singular pieces. After a while, the differences and the echoes shift, and become more prominent (reminiscent, slightly, of the character Auggie’s daily photographs in the Paul Auster-writ 1995 feature length film, Smoke). Freedman’s poems speak through physical and cognitive boundaries, working to stretch beyond into further connection, all while articulating from a kind of insularity. “I get up feeling / numb,” he writes, to open one of the poems further in the collection, “but not really / numb, more like I get up / feeling contempt for a / numbness.” Or, a page prior: “From the body cave / to the body boundaries, / we are immersed in the / circumstance of holding our / selves in place.” The meditative lyric that Freedman writes is deeply evocative, writing a kind of dislocation through the self that is intriguing to work through. Or, as the first poem in Freedman’s collection begins: “The aim of this writing / is to show that / I does not disappear. / Even when I disappear I / does not disappear.”