Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 142

December 7, 2021

Cal Bedient, The Breathing Place

Two police cars outside: flush yr Centaur.

The sea-squids of the congresses

swim among the flooded people;

a star urinates over Cupcake mountain;

cloud livers drip on the gardens.

We take it as a sign, pixelated –

we, a short fever in space

combining

ones and the empty sign for nothing. (“Sat Down and Wept By Lake and Cloud Gear”)

From California poet, critic and editor Cal Bedient comes

The Breathing Place

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), following

Candy Necklace

(Wesleyan University Press, 1997),

The Violence of the Morning

(University of Georgia Press, 2002),

Days of Unwilling

(Saturnalia Books, 2008) and

The Multiple

(Omnidawn, 2012). There is something curious in the way his narrative lyrics write their expansivenesses from a foundation of poets such as Emily Dickinson, William Blake and Herman Melville, whether the long line or the sharpened space. As he writes to open the poem “What Was to Be an Elegy for Emily Dickinson”: “Why should there be red shoes if the earth was never born, / it was never born and these are its red shoes, / these the cerise Atlantic clouds to be taken with no comedy / remainder, why should there be a suchness of the day, // when a lightning suspender is no union.” In a curious combination of response and translation, his poems each establish a particular and expansive field, and write from within such in slightly different ways, whether filling up that space, or establishing the space through writing around particular absences. As he writes to open his “NOTES” at the end of the collection: “Now and again, this collection echoes (adopts, adapts) material from William Blake, César Vallejo, Tomaz Salamun, Fredericke Mayröcker.” “If breath were a sort of gigantic torso / will all possible earths in it,” he writes, to open the poem “Breathless,” “all Hatchling / molecules; If it could be jacked into the music / of Many Fountains starting up Together [.]”

From California poet, critic and editor Cal Bedient comes

The Breathing Place

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), following

Candy Necklace

(Wesleyan University Press, 1997),

The Violence of the Morning

(University of Georgia Press, 2002),

Days of Unwilling

(Saturnalia Books, 2008) and

The Multiple

(Omnidawn, 2012). There is something curious in the way his narrative lyrics write their expansivenesses from a foundation of poets such as Emily Dickinson, William Blake and Herman Melville, whether the long line or the sharpened space. As he writes to open the poem “What Was to Be an Elegy for Emily Dickinson”: “Why should there be red shoes if the earth was never born, / it was never born and these are its red shoes, / these the cerise Atlantic clouds to be taken with no comedy / remainder, why should there be a suchness of the day, // when a lightning suspender is no union.” In a curious combination of response and translation, his poems each establish a particular and expansive field, and write from within such in slightly different ways, whether filling up that space, or establishing the space through writing around particular absences. As he writes to open his “NOTES” at the end of the collection: “Now and again, this collection echoes (adopts, adapts) material from William Blake, César Vallejo, Tomaz Salamun, Fredericke Mayröcker.” “If breath were a sort of gigantic torso / will all possible earths in it,” he writes, to open the poem “Breathless,” “all Hatchling / molecules; If it could be jacked into the music / of Many Fountains starting up Together [.]” Constructed in three sections—“Limits of the Containing Air,” “The Era” and “Green Water”—the poems in The Breathing Place display both an alertness and a fierce intelligence, offering both deep inquiry and descriptive strength, swirling simultaneously lyrically surreal and direct language into a series of sharp, stunning observations. “I liked my cheek,” he writes, to close “Ferns, Fingers, Gorges,” “against his baby. I put my tongue on Time, / I cry and crouch in her blindswarm, / my vaulting lady.” Or, as he writes to close the short sequence “Self-Portrait as Absence of Days,” composed “In Memory of ‘Annah Sobelman” (a poet I am sad to discover died in 2017 [see my review of her 2012 poetry title here]):

Comes the moment when, Flashlight dead,

You cannot go farther into the abandoned mine,

You cannot return:

There was no cry of “fire in the hole.”

But there is always fire in the Hole.

December 6, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Caitlin Galway

Caitlin Galway’s

debut novel Bonavere Howl was a spring pick by The Globe and Mail. Her short fiction has appeared in The Puritan as the winner of the 2020 Thomas Morton Prize, Gloria Vanderbilt’s Carter V. Cooper Short Fiction Anthology, House of Anansi’s The Broken Social Scene Story Project, and Riddle Fence as the 2011 Short Story Contest winner. Her nonfiction has appeared on CBC Books as the winner of the 2011 Stranger than Fiction Contest, judged by Heather O’Neill.

Caitlin Galway’s

debut novel Bonavere Howl was a spring pick by The Globe and Mail. Her short fiction has appeared in The Puritan as the winner of the 2020 Thomas Morton Prize, Gloria Vanderbilt’s Carter V. Cooper Short Fiction Anthology, House of Anansi’s The Broken Social Scene Story Project, and Riddle Fence as the 2011 Short Story Contest winner. Her nonfiction has appeared on CBC Books as the winner of the 2011 Stranger than Fiction Contest, judged by Heather O’Neill. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Bonavere Howl was the first time I centred family grief in a story and, though I didn’t realize it at the time, I think that this needed to be done. Complex grief dominates every page of the book, whether it’s the narrator’s own tangled feelings, or the dynamics of a family all suffering from a different strain of the same trauma. The book also explores the sort of joyful, strange, fiercely private world siblings can build. Only in writing the story of the Fayette family did I realize how deeply my own childhood still affected me, in positive and negative ways.

My most recent work is a short story that I’m still plugging away at, and it takes place in 1980s Nevada, mostly the Las Vegas Strip and the Mojave Desert. It explores the fragmenting of self that often follows abuse or assault, but in a fairly abstract way that allows me to play with notions of time loops and wormholes. The contrast between this story and the one I wrote immediately before it is pretty stark (the latter deconstructs a complicated friendship between two women in Depression-era North Tarrytown, as well as the nature and role of folklore), but just as with Bonavere Howl, there are shared themes of trauma, identity, the stories we tell ourselves, and the fear of losing one’s mind.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Fiction is what’s natural to me. I remember being little and getting my first journal. The one time I tried to use it as a diary and write about my day, I got distracted imagining ways to describe what I saw through sound imagery. I prefer being immersed in the abstract, while also exploring ideas through the vehicle of another person, and following them through their unique space and time.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Initial story ideas are a little inexplicable and instantaneous for me. They sort of jump out and hit me in the head. An image, a sense of atmosphere, a sharp feeling. After that spark, tons of ideas flow out, followed by an often blurry process of figuring out what to make of it all. I also do a lot of layering, so even after the notes have been shaped into a proper story, there’s a long process of stepping away, working on something else, then returning and adding another layer. Stepping away, adding a layer, over and over. It feels like adding subtle layers of paint, and seeing how each one enriches and gradually shifts the story.

Some aspects of a story remain the same from first to final draft, but there are always drastic changes. In my story “The Lyrebird’s Bell”, for example, the narrator Betsy was entirely crystallized from the start. A hundred things were altered around her—the setting moved from Connecticut to Victoria, Australia, and the folklore weaving throughout changed from Norse to Russian—but Betsy was entirely Betsy from day one.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My earlier short stories felt standalone, but I’ve been working on a collection for the past few years; though each story is quite different, and I haven’t been writing them with any intention to connect them, I feel that they speak to each other.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t really factor public readings into my process, but neither are they counter to it. I appreciate, enormously, any reading that I’m invited to participate in, but I’m also extremely shy and anxious. School speeches made me physically ill. That said, I always walk away from readings feeling closer to my community. It’s such a warm feeling that I’ve come to value more and more.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Theoretical concerns certainly find their way into my underlying themes. I tend to play with questions of identity and where the pure “I/we” exists when stripped of the external, as well as the interplay between self and environment, self and others. We’re asking so many deeply valid questions about identity right now, many of which have been asked for a long time and are only now receiving widespread consideration. My fiction comes from a very personal place, though, and I follow my instincts; concerns or commentary are rarely mapped out early on.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I believe there are countless roles, and they’re fluid and ever-changing. I value the cultural critic, the satirical agitator, the poet healer, the experimental surrealist deconstructing genre, and so on.

8 – Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely both! Considering the opinions of informed, capable editors and readers is important. We have to be able to shove our egos aside and soften to the perspective of others. We also don’t know all of our own biases. It’s an invaluable quality to be able to fully acknowledge that learning is an ongoing process. We can have full confidence in our vision and still understand that we might miss something that someone else could see.

9 – What is the best piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” It’s from Kafka, and it’s always spoken to me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

Short story structure has always come naturally to me, but the structure and pacing of a novel initially required some tinkering. I needed to figure out how to make my own way of storytelling fit within the mechanics of a novel. For me, the appeal of writing a novel lies in not feeling done with the characters’ journey. I simply haven’t finished telling their story.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My day starts a little oddly. I’ve been an extreme night owl for about 15 years and usually go to bed just after sunrise. I’m completely out of sync with the world. I wake up in the early afternoon and edit manuscripts, or teach writing and reading to students. Then, I spend the night—which is, thankfully, much quieter and more solitary than the day—writing and reading until I fall asleep.

12 – When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If a particular story gets stalled, I put it aside for a couple of weeks or months and work on another piece. It’s typically a matter of needing some breathing room. If I sense that I do really need to keep scraping away at it, though, I’ll read and read and read and read. “The Lyrebird’s Bell” didn’t have enough wind in its sails until I read the first page of Picnic at Hanging Rock. That my story could only possibly be set in the Australian bush seemed immediately and almost painfully obvious.

13 – What fragrance reminds you of home?

For years, my rather large family lived a bit crammed in a small townhouse, and every winter, my mother bought clementines. The scent of clementines makes me think of Christmas with my family all together, tripping over each other, which for me is home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature and history are both profound influences. Setting is inextricable from just about every aspect of my stories. I become obsessive about the era and place in which the story is set, and everything from its natural environment and folktales to its wars and architecture becomes essential.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Simply as a reader, I’d say the Brontë sisters are important in my life. They wrote strange, darkly imaginative, honest things, and I know it’s silly, but they feel like friends across time. I’m also a big reader of anything covering current affairs. I believe that it’s important to be informed, and to evolve in our understanding of what “informed” means. As a chronic insomniac, I’d say that fairy tales hold a special place in my life, as well. I’ve always found them soothing. I have a first edition Magic of Oz and sometimes I read it and admire the old inking errors before bed.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want to explore a rainforest. Any rainforest, all of the rainforests. I’ve been held back by a dark suspicion that a tiger or jaguar is going to maul me.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

There was a time when I thought I might be both a writer and a lawyer. I become obsessively consumed by my projects, though. I’m always forehead-deep in a story, and it takes running out of food to make me stop and leave my apartment. I’d be the same as a lawyer. An overworking legal drama cliché. Pursuing both would never have worked.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’m one of those irritating people who knew they wanted to be a writer in kindergarten. Writing is how my brain shapes and processes the world.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was . Once I finished it, I sat thinking about how much human connection I allow into my life. It really shook me, and I crave books like that, the jolt they provide. The last great film I watched was Little Women. I read the novel as a little girl and connected with Jo, but it troubled me—as it troubled Alcott, whose hand was forced in this direction—how great an emphasis was placed on Jo finding romance. The film blew past it in such a self-aware, validating, and funny way, and it finally let Jo’s commitment to autonomy and her dream of storytelling be the height of her emotional journey. It was a clear-eyed adaptation and just brought me a lot of joy.

20 - What are you currently working on?

At the moment, I’m working on two projects. One is a short fiction collection exploring the themes and avenues I find most integral to my work, through my particular version of magical realism. The other is a novel based on “The Lyrebird’s Bell”, which follows the friendship between two isolated girls in the post-war Australian bush. The novel picks up where the short story finished, and shows the aftermath of an act of violence, the history that led to it, and the complicated family dynamics in which the girls are trapped.

December 5, 2021

JoAnna Novak, New Life

Thalamos

Beyond copse and corpse, hedgerow and scarlet hip,

the tent is white and obvious. Inside, a bride

begins her tour. Her train is gone, veil a jubilate

square. Now congratulations and congratulations and

this baby suits you. I have traded my Napoleon

for chicken. I am one sad stop, inevitable as a dandelion

clock. A dessert fork dings the first glass. Cousins

constellate and fib. Look at little mama, how

beautiful, peacocks gawping the photo booth, look

at some smokers off stubbing cigarettes on the empty

lawn. It is easy enough to smile through toasts, friends’

confessions, a brother’s snafus in a dress

of Normandy blue. Secrets macramé the neck,

and silence the sonar, starlit in rain.

Across the lawn, our story skips the dogwood grove:

I too walked an aisle, really very happy.

Writer, editor and publisher (founder of the chapbook publisher and online journal Tammy) JoAnna Novak’s third full-length poetry collection, following

Noirmania

(Inside the Castle, 2018) and

Abeyance, North America

(New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

New Life

(New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2021). Constructed in five numbered sections of narrative lyrics, New Life articulates her pregnancy, often in surreal, descriptive tones, composing short bursts of lyric narratives that explore around and through the core of the experience. As the title poem, “New Life,” opens: “does not survive on protein alone. My ankles are bound / to tear marching this reef, yet what a thrill—bloodying / white pumps. The island is mine. A mole on earth’s back, / bull’s eye, bingo, scratch, bite. At seven and twelve and thirteen / weeks, the pulse shimmers like a firefly: interruption.”

Writer, editor and publisher (founder of the chapbook publisher and online journal Tammy) JoAnna Novak’s third full-length poetry collection, following

Noirmania

(Inside the Castle, 2018) and

Abeyance, North America

(New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

New Life

(New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2021). Constructed in five numbered sections of narrative lyrics, New Life articulates her pregnancy, often in surreal, descriptive tones, composing short bursts of lyric narratives that explore around and through the core of the experience. As the title poem, “New Life,” opens: “does not survive on protein alone. My ankles are bound / to tear marching this reef, yet what a thrill—bloodying / white pumps. The island is mine. A mole on earth’s back, / bull’s eye, bingo, scratch, bite. At seven and twelve and thirteen / weeks, the pulse shimmers like a firefly: interruption.” There is a shift in tone and tenor from her previous collection, one held in state and space, “ultrasounds and sustenance” (“Forecast”), engaged in a simultaneous anxiety and calm, the contradictions of anticipation, agitation, isolation and connection through the stages of pregnancy. “Wading in waist-high— // wait,” she writes, as part of the flow of the poem “Tides,” “where is the waist? My bulge, // my bilge, my breasts, my rolled // neck: feels like the rest of my life, // totting / weeks to translate days, [.]” She writes of phallus, lake, glitter and agency with a swagger and rapture. Clearly, hers is a lyric of pointed precisions and very physical gestures; of effects bore down to bone. “What would you do with / a thick moment off the map?” she asks, in “House Sitter,” or in the poem “Trimester,” where she writes: “Give me grander // reptiles on this inhospitable island. Garter on a swing tray, / diamondback tub, / Animal, I don’t want to go in the pool / and I won’t lose my tongue // and I won’t like your table. Give me ether, / at least twilit sleep, Tonga Room / dreams, trek over stream, / rain and rum on the half hour— [.]” There is such firm confidence in her lyric, even as she navigates such unfamiliar terrain as this particular state of the body and impending birth; a confidence that holds firm to every lesson garnered, glanced and won, as the two-page poem “Everything and fireworks” ends:

I’ve learned what I have

to do is a sentence;

what I get to do

is a gift.

December 4, 2021

(Re)Generation: The Poetry of Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, selected with an introduction by Dallas Hunt

not calling you at this moment means only that i am writing poetry

because my voice cannot tell the story

of this (“driving to santa fe”)

I remember hearing Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm perform a handful of times throughout the 1990s, so I’m appreciating the opportunity not only to revisit her work, but to garner a far wider and deeper appreciation through the recently-released

(Re)Generation: The Poetry of Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm

. Selected with an introduction by Dallas Hunt (Waterloo ON: Wilfrid Laurier University, 2021), (Re)Generationwas produced as part of the Laurier Poetry Series of critical selecteds. As Hunt offers through his critical introduction, Akiwenzie-Damm’s work emerges out of a community, influenced by and responding to the work of those around her, from forebears to contemporaries. Hunt writes on the emergence of her work as a publisher (founding Kegadonce Press, an Indigenous publishing house, in 1993), editor and organizer, all of which simultaneously broadened the scope and possibility of her poems, including how “she ‘started thinking about sex and sexuality and the utter lack of it in Indigenous writing.’” Selecting from her five books and chapbooks, as well as some uncollected pieces, Akiwenzie-Damm writes an accumulation of direct statements, one upon the other, constructing single thought-line/phrase upon single thought-line/phrase; sometimes with pause, and other times at full speed, in a rush. She blends a storytelling and spoken word aesthetic with the act of capturing full on the page a sensuality, full heart and a rush, writing history and heartbreak and breath. Writing on her explorations of desire and the erotic, Hunt offers, further on: “In many ways, this is what Akiwenzie-Damm’s work achieves: the ability for Indigenous peoples and communities to feel joyous touch, sexual pleasure, and intimacy, in spite of a colonial world that has attempted to rob us of these affective registers, both historically and in the contemporary moment.”

I remember hearing Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm perform a handful of times throughout the 1990s, so I’m appreciating the opportunity not only to revisit her work, but to garner a far wider and deeper appreciation through the recently-released

(Re)Generation: The Poetry of Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm

. Selected with an introduction by Dallas Hunt (Waterloo ON: Wilfrid Laurier University, 2021), (Re)Generationwas produced as part of the Laurier Poetry Series of critical selecteds. As Hunt offers through his critical introduction, Akiwenzie-Damm’s work emerges out of a community, influenced by and responding to the work of those around her, from forebears to contemporaries. Hunt writes on the emergence of her work as a publisher (founding Kegadonce Press, an Indigenous publishing house, in 1993), editor and organizer, all of which simultaneously broadened the scope and possibility of her poems, including how “she ‘started thinking about sex and sexuality and the utter lack of it in Indigenous writing.’” Selecting from her five books and chapbooks, as well as some uncollected pieces, Akiwenzie-Damm writes an accumulation of direct statements, one upon the other, constructing single thought-line/phrase upon single thought-line/phrase; sometimes with pause, and other times at full speed, in a rush. She blends a storytelling and spoken word aesthetic with the act of capturing full on the page a sensuality, full heart and a rush, writing history and heartbreak and breath. Writing on her explorations of desire and the erotic, Hunt offers, further on: “In many ways, this is what Akiwenzie-Damm’s work achieves: the ability for Indigenous peoples and communities to feel joyous touch, sexual pleasure, and intimacy, in spite of a colonial world that has attempted to rob us of these affective registers, both historically and in the contemporary moment.” river song

take me down to the river’s edge with a rush of tears and the sound of angels’ wings

give me breath with a host of desire and a single touch lifted from despair

wash my fears at the martyrs’ grave with the blood of saints shouting holy names

sing my pain in mid-summer rain with forgotten words and a tongue of fire

dance my heart like a laughing child like a drunken man with sallow cheeks lash

my burdens to another cart with ropes of your hair and no mercy feed my head

with beauty and stories collected like shells from old women in kerchiefs

and storm whipped beaches forget my ugliness and the imperfections large

and small that make me ashamed but human carve my name in the dead of night

beyond all stars and forgiveness

December 3, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Shawn Rubenfeld

Shawn Rubenfeld

has had short fiction appear in journals such as Permafrost, Columbia Journal and Portland Review. He has a Ph.D. in English and Creative Writing from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he is currently a lecturer. He is the author of the novel,

The Eggplant Curse and the Warp Zone

, out May 2021 from 7.13 Books. He lives in Omaha.

Shawn Rubenfeld

has had short fiction appear in journals such as Permafrost, Columbia Journal and Portland Review. He has a Ph.D. in English and Creative Writing from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he is currently a lecturer. He is the author of the novel,

The Eggplant Curse and the Warp Zone

, out May 2021 from 7.13 Books. He lives in Omaha.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Luckily it didn’t. My life hasn’t changed, and I like it that way. In fact, I’d much prefer that my work changes someone else’s life--that someone, somewhere can connect with it in some impactful way.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I actually didn’t! As a kid, I was primarily drawn to poetry. I carried a notebook around school with me which I’d fill in with poems whenever I was supposed to be taking notes (I had a science teacher once tell me you take such good notes when really I had spent the entire year working on my poems ). Back then I wrote fiction, too, but it wasn’t until I was an undergrad that fiction became my primary focus. That was because of a generous professor of mine, Heinz Insu Fenkl, who I worked with as part of an Independent Study. I walked into his office at the beginning of my sophomore year and told him I wanted to write a novel. He asked for a sample of my work so I gave him a story I wrote for a recent workshop. He told me he was impressed by it but that I shouldn’t write a novel. At least not yet. I needed to read first, to start small. So, we spent the entire semester talking craft, reading work by Toni Morrison and Madison Smartt Bell. I walked away with two new stories--one of which would eventually make up part of my MFA applications--and an understanding of intellectual generosity that I try to carry with me throughout my own academic life.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s so hard to pinpoint because each project looks different. I’ve struggled slowly with some stories but really cooked through others. I would say that first drafts, at the very least, always resemble the finished product, even if just in tone. Revision is such an important part of my writing process, which is why I so frequently emphasize it when I teach.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

If it’s a novel then I know I’m working on it from the very beginning. Maybe it’s because one has to occupy a certain mental space before committing to a novel. But as soon as I get started, I know if it’s a novel or not. But story collections are “larger projects” as well. Often my stories align thematically with my other stories but I don’t realize quite how connected they are until I’m done writing. So in that case, I may not be working on a “book from the very beginning” at all, but rather short pieces that do end up combining into larger projects.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Definitely part of. It’s so rewarding to hear something being reacted to in real time, to see if jokes land, if people are digging it. I really feed off that energy.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Of course. It varies so much based on the project. For this particular novel, The Eggplant Curse and the Warp Zone, I was initially interrogating fandom and communities, millennial angst, and the conflicts and implications of regional identity. But a lot of my current work, especially my short fiction, examines intergenerational Holocaust memory.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers have always had a great responsibility and that is even more true now. The writer documents. The writer brings the world to the reader. By simply holding a mirror up to society, writers can help readers understand, which is also why it’s important we amplify voices from marginalized communities, which also happens to be where some of the best work today is being written. Of course writing can be fun and be purely for entertainment and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with work like that, but writing can also do so much more. Writing can bring about change.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. The critical, objective eye a good editor brings is everything.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

As I was working on my dissertation, my adviser often shared variations of Nike’s Just Do It. As in, just get it written. Just get it done. Just do the work. Sometimes it’s exactly what a writer needs to hear. Enough talking about it, just do it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories to the novel to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

While I don’t think that moving between genres is easy, I do think that a good fiction writer has a lot to gain from writing poetry, from thinking about the integrity of the word, the line, and vice versa. It can really change your work.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I do most of my writing in the morning, at my desk, with a view of the sun from my office window. Other than that, there isn’t a typical day for me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to remind myself that writer’s block is a myth. If you write yourself into a wall, you can write yourself out of it. But sometimes you’re out of juice for the day and when that happens, I go for a walk, I take a drive, I put a show on. I do something else. Often I’ll enter revision mode and read over what I already have written (this also serves as a gentle reminder to use my inventory when I need help moving forward), but sometimes the writing is done for the day and that’s okay too.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Salt. Seaweed. Sunscreen. The Atlantic meeting the south shore of Long Island.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’m very influenced by music. The right song helps to put me in the right headspace. But I also take influence from film, travel, and art. My debut novel, of course, was influenced by retro video games and is filled with references (some overt and some implicit) that reflects that.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Too many to list here. I would argue that almost every book I’ve read has influenced my work in some way, even if that influence was minor.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I like to travel, so I’d love to visit every country. I have a long way to go, but I also have a lot of life left to live.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I come from a family of accountants (literally: father, both brothers, uncles, cousins), so dare I say it...

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

See answer to previous question. But also, I wanted to engage with people. To explore. It wasn’t that I felt like I had something to say. It was just that I needed to write. I read books so often as a kid that writing was something I started to do without a second thought. I know that even if I step away from it for a bit, the pull of the work will draw me back.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Claudia Rankine’s Just Us. The last great film I watched (re-watched, really) was Come and See , a Soviet masterpiece loosely based on the Khatyn massacre in Belarus. It’s one of the toughest films I’ve ever seen, but it’s brilliant.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just put the finishing touches on my story collection, which is very exciting and I’m getting started on a second novel, which is tonally and thematically different from The Eggplant Curse and the Warp Zone. Speaking of, I’ll end this with a shameless plug: The Eggplant Curse and the Warp Zone is out now. Give is a shot. Support authors. Support indie presses.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 2, 2021

John Yau, Genghis Chan on Drums

O Pin Yin Sonnet (15)

We’re not talking about Asians; we’re talking about China

It is smart business to name a restaurant chain after a cuddly bear

Who happens to be a vegetarian, but it is another thing

To go big-game hunting in the African savanna

I would just as soon turn a panda into a huggy coat or hat.

Importing kudu horns or making a zebra into a rug—

This is real and different. For one thing, it’s permanent,

Not just a bowl of green weeds and brown meat scrape

Gobbled, wolved, or slurped up or jammed down with sticks

Standing beside a dead giraffe that you shot on a hot day

Proves something about the depth of your character

I respect a man or woman that displays big-game trophies

We had Teddy Roosevelt, his Big Stick policy and Rough Riders

What does China have: old men with canes and fallen zippers

It is impossible not to delight in the near two hundred pages of American poet John Yau’s latest,

Genghis Chan on Drums

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), a book that follows nearly a dozen poetry collections across more than forty years, as well as numerous chapbooks, works of fiction, criticism, collaborations and monographs. This is the first of his titles I’ve gone through, and I’m immediately struck by the clarity of the direct statements in his poems, especially the ways in which Yau returns years’ worth of racist comments, microaggressions and injustices back in the most powerful ways possible. The poem “On Being Told that I Don’t Look and Act Chinese,” opens: “I am deeply grateful for your good opinion / I am honestly indignant / I am, I confess, a little discouraged / I am inclined to agree with you / I am incredulous / I am in a chastened mood / I am far more grieved than I can tell you / I am naturally overjoyed [.]” There is a confidence and a strength here, one he knows when and how to play, push or hold back, from a poet who clearly knows exactly what it is he’s doing, and what tools he’s working with.

It is impossible not to delight in the near two hundred pages of American poet John Yau’s latest,

Genghis Chan on Drums

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), a book that follows nearly a dozen poetry collections across more than forty years, as well as numerous chapbooks, works of fiction, criticism, collaborations and monographs. This is the first of his titles I’ve gone through, and I’m immediately struck by the clarity of the direct statements in his poems, especially the ways in which Yau returns years’ worth of racist comments, microaggressions and injustices back in the most powerful ways possible. The poem “On Being Told that I Don’t Look and Act Chinese,” opens: “I am deeply grateful for your good opinion / I am honestly indignant / I am, I confess, a little discouraged / I am inclined to agree with you / I am incredulous / I am in a chastened mood / I am far more grieved than I can tell you / I am naturally overjoyed [.]” There is a confidence and a strength here, one he knows when and how to play, push or hold back, from a poet who clearly knows exactly what it is he’s doing, and what tools he’s working with. Structured via nine sections of poems, plus a prose poem in prologue, and two poems in epilogue, Yau appears to be engaged in multiple conversations, including a section of poems in which he responds to the previous administration, including the former American President, responding to history and culture as it occurs. “There are no words to express / the horrible hour that happened,” he writes, to open “The President’s Third Telegram,” “Journalists, like all fear, should be / attacked while doing their jobs [.]” Weaving in elements of culture and current events, much of which touch upon larger issues of fearmongering and racist dog-whistles, Yau’s is a very human and considered lyric sense of fairness and justice, composing poems that push back against dangerous rhetoric, outdated or deliberately obscured language and racist ideas and ideologies. In his own way, Yau works to counter the ways in which language is weaponized against marginalized groups, attempting to renew human consideration by showcasing how inhuman and destructive language has become. “We regret that we are unable to correct the matter of your disappointment,” he writes, as part of “Choose Two of the Following,” “We quaff mugs of delight while recounting the details of your latest inconvenience [.]”

Structurally, Yau appears to favour the extended suite: individual self-contained poems each sharing a title, although numbered in sequence, from the nineteen numbered “O Pin Yin Sonnet” poems, the eight “The Philosopher” poems to five “A Painter’s Thoughts,” each grouped together at different points in the collection. Given his lengthy publishing history, it would make sense that there are elements of this collection that extend further what he’s worked through previously, and there are points at which poems included here very much do feel an extension of a conversation I might not have encountered at the beginning. The most obvious suggestions of Yau working an ongoing series of conversations being, of course, how the nineteen “O Pin Yin Sonnets” begin their numbering at “10,” or how poet Monica Youn infers in her back cover blurb that the character/”alter-ego” Genghis Chan is one that Yau has utilized previously. Throughout, Yau engages in multiple and ongoing conversations, it would seem, from culture to politics to other writers, such as the first of the paired epilogue poems, “Nursery Song,” subtitled “(After Sean Bonney),” paying tribute to both the late British poet and activist, as well as engaging with some of Bonney’s own ongoing concerns. As the poem begins:

Don’t say “pandemic lockdown”

Say Fuck the rich/their private island getaways

Say Fuck their Aspen lodges/stocked with climate-controlled volcanoes

and children named after weather stations and rare cheeses

Don’t say “clubbed and beaten”

Say Fuck clubbing and slumming

Say Fuck following and liking

Don’t say “assortment of pretty much everything you can imagine,

at a loss for words, beyond your wildest dreams”

Don’t say “quartz countertops, home theater, private cul-de-sac, second getaway”

Say Fuck the rich, their carbon footprint, their dinosaur ways

December 1, 2021

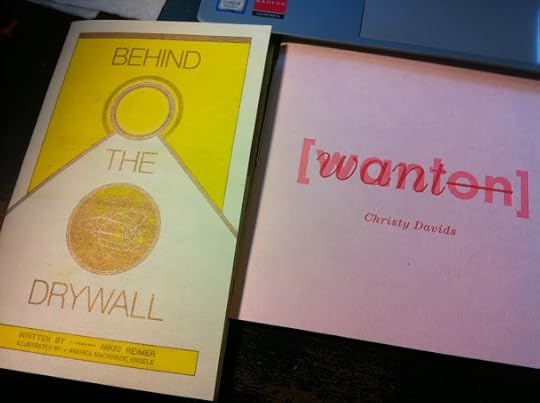

Ongoing notes: early December 2021: Christy Davids + Nikki Reimer/Andrea MacKenzie Engele,

I seem to be on a roll these days, it would seem. Chapbooks?

I seem to be on a roll these days, it would seem. Chapbooks? And you are keeping an eye on what’s been going on over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, yes? And Touch the Donkey? And many gendered mothers? And above/ground press? And the weekly interviews via the Chaudiere Books blog?

Brooklyn NY: It is good to see a new chapbook title by American poet Christy Davids [see her “Tuesday poem” here], her wanton(DoubleCross Press, 2020), a chapbook-length poem-sequence of accumulated lyric fragments that play with information and commentary around female desire, sexual fantasy, reproductive biology and Craigslist-like personals: “wanted edgy alternative tattooed nerd girl wanted single local / female wanted rough or ravaged wanted reversing role and using / strap-on wanted steady girl for bj weekly wanted something more [.]” There is less a sense of commentary here than simply offering a collage of related information and perspectives, bringing together a series of scraps and fragments to cohere into a larger shape. How does one idea relate to the next? How does one idea determine what follows? As her first footnote, to the line “I can appear fertile,” offers: “A 2006 study in the journal Hormones and Behavior found that women who had their pictures taken during fertile and non-fertile stints were judged to be trying harder to look nice on fertile days, suggesting the hormonal boost of ovulation may translate to real-life decision-making.” Given she has now produced a handful of small chapbooks over the past few years, one can only hope that Davids’ is working toward something full-length.

we are taught (re)production determines

the social value of female bodies, so

I can secrete with discretion

warrant only instances

of mating and sheer

prettiness, perpetual

arousal carousel

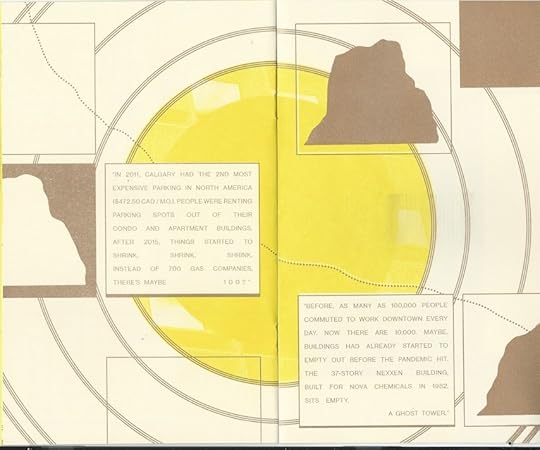

Calgary AB: How does one even discuss, properly, this new chapbook title by Calgary poet Nikki Reimer, BEHIND THE DRYWALL (Gytha Press, 2021)? “Written by Nikki Reimer / Illustrated by Andrea MacKenzie Engele,” BEHIND THE DRYWALL is a title that communicates in tandem, almost in collaboration, between the writer and illustrator/designer. BEHIND THE DRYWALL is composed as a lyric collage set to an illustrated, visual music, offering a critique of Alberta’s oil and gas industry, Calgary’s self-identifications and self-delusions, as well as the capitalist bent that has reduced an expansive and overly-aggressive construction into a downtown abandoned by humans. Hers is a Calgary caught between bust and boom, and the human expense of whichever side of the coin is in current play. In certain ways, Reimer and Engele’s BEHIND THE DRYWALL is a language-driven capitalist collaboration and collage update of Calgary writer Aritha van Herk’s infamous 1987 long poem, “Calgary, this growing graveyard,” which is, once one considers the comparison, a frustrating one, given how little improvement has followed, over those intervening years.

November 30, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dani Putney

Dani Putney

is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race Filipinx, & neurodivergent writer originally from Sacramento, California.

Salamat sa Intersectionality

(Okay Donkey Press, May 2021) is their debut full-length poetry collection. Their poems appear in outlets such as Empty Mirror, Ghost City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Juke Joint Magazine, & trampset, among others, while their personal essays can be found in journals such as Cold Mountain Review & Glassworks Magazine, among others. They received their MFA in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women & are presently an English PhD student at Oklahoma State University. While not always (physically) there, they permanently reside in the middle of the Nevada desert.

Dani Putney

is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race Filipinx, & neurodivergent writer originally from Sacramento, California.

Salamat sa Intersectionality

(Okay Donkey Press, May 2021) is their debut full-length poetry collection. Their poems appear in outlets such as Empty Mirror, Ghost City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Juke Joint Magazine, & trampset, among others, while their personal essays can be found in journals such as Cold Mountain Review & Glassworks Magazine, among others. They received their MFA in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women & are presently an English PhD student at Oklahoma State University. While not always (physically) there, they permanently reside in the middle of the Nevada desert.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It’s difficult to think that my first book changed my life in any significant way. I know some folks expect something to feel different post-publication, but it’s pretty much the same for me: write, revise, submit, repeat. No glory. (But then again, I don’t think most writers do it for glory...) However, my most recent work, especially the poems I’ve written since my book was accepted for publication at Okay Donkey Press, is very different tonally than the pieces in my collection. Perhaps it’s a more “mature” voice, but in any case, I feel that the speaker (or speakers, rather) I write into my poems now view the world, and themselves, much differently than before.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually didn’t come to poetry first! Like many writers, I started writing fiction first, but it quickly became apparent to me that the genre was, well, too prosaic. Too many words, too much time wasted. I wanted narrative to be in my work, sure, but the narratives of fiction felt too constraining to me. Poetry was the next genre I toyed around with, but it stuck—it made the most sense to me. I also write creative nonfiction, but when I was first starting out as a writer about 8 years ago, I wasn’t too familiar with the genre. Now, whenever I have an idea that’s too long for a poem, I turn to CNF to meander a bit; I mean, the word “essay” does come from “assay,” to experiment.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I suppose the best answer is “all of the above.” Sometimes I write poems very quickly, in less than an hour, but they usually take me several hours or a few days. Now, when I say “several hours or a few days,” I’m talking about the exact amount of time I spend writing a poem, not the in-between or break periods. With that in mind, it could easily take me, say, 10+ hours to crank out a “first” draft of a poem. But I suppose all the hours I spend on the front end ultimately mean I take less time on the back end, that is, during revision. Even after receiving lots of wonderful feedback on a poem from a workshop, for example, the revision period for that poem, at that particular point in time, might only be about 2 or 3 hours. I’m the type of person to meticulously craft something so that it appears pretty solid from the outset, but I still spend a good amount of time revising my work afterward. I’m just not, you know, somebody who can sit at a desk and sprawl; I’m always in the process of crafting my poetry.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems almost always begin as small phrases I write down in the notes app of my phone (which I lovingly refer to as my “journal”). For example, I recently wrote a poem about balikbayan boxes, a piece that started as the word “balikbayan” in my journal. I wrote this word down right after I’d walked by an LBC. (To give some context, balikbayan boxes contain items sent from overseas Filipinos to their family and friends in the Philippines. LBC is a popular Philippine courier service with many branches in the US.) You can essentially apply this process to, say, 80 percent of my poetry. However, I sometimes work on longer, multi-poem projects, which, of course, require more advance planning. As for writing with a book in mind, I think I always do that! When writing my first collection, for instance, I always thought about which poems could appear in the book and how I could eventually order it. Lots of pieces didn’t make the cut, but I was always thinking about the final “product,” if you will.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love me a good reading! I’m such a natural performer that any attention I can get gives me energy and life. It helps that I’m an ENFJ (if you know your Myers–Briggs personality types), with the “E” meaning “extroverted,” so I thrive at public readings with other poets and writers. I also think that there are so many bad readers out there—really, even some of the greatest writers are terrible at publicly reading their work—so I always come to a reading with the mindset that (1) I don’t want to suck and (2) I want to give somebody an experience, something they couldn’t get on the page alone. I think the fact that I mainly write poetry helps, too, because it started many years ago as an oral art anyway.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’d say theory is always at the back of my mind when I write poetry. Much of my first book, for example, dialogues with and reflects on ideas popularized by various philosophers and, more specifically, literary theorists. One of the poems in my collection ruminates on the mirror stage, a concept from Jacques Lacan. Another poem in my book is a direct address to Judith Butler’s earlier work regarding gender theory. Getting even more esoteric, I have a poem called “Jouissance” in the book that engages with Leo Bersani’s concept of the same name, as explored in his essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?” I wouldn’t say I’m answering any particular questions so much as I’m extending these theorists’ lines of thought and, more than that, appropriating their ideas to reflect on my own sense of identity as a poet. Specifically, much of the theory-focused poems in my collection deal with facets of my intersectional identity: my queerness, non-binary gender, etc.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t think writers have a specific societal role. To me, writing is a very selfish thing—but not in a bad way! I’m so glad I have readers who enjoy my work, but at the end of the day, I write for me. Publishing my work is an afterthought, not the impetus for writing. However, if I had to think of one thing writers do well in terms of larger culture, I’d have to say that they provide representation in a way that helps to make the world a more empathetic place. Of course, it’s a more complex phenomenon than simply encouraging empathy, but if we didn’t have writers, you know, selfishly writing about their complicated identities or sharing their experiences, then people would be much more in the dark about others’ diverse perspectives, I think.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely essential. The suggestions I received from the editorial team at Okay Donkey Press helped make my book an even better, well-rounded collection. We reordered some parts, added some poems, and took out a couple of pieces. I didn’t expect to receive such care for and attention to my poetry, but Genevieve and Matt at OKD gave me that and more. I understand the resistance to editors looking at one’s work, especially if one thinks the piece is “finished,” but trust me, they almost always have something helpful to add.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This is tough because I tend to think about all the bad advice writers receive! But if I had to choose one thing, I’d say it was when I was reaffirmed that I didn’t have to write each day. I’ve never been somebody to write every day, so hearing another person say it was okay to do so when, well, I’d been told for a long time that “good” writers were putting in daily work was very uplifting for me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Not that difficult, to be completely honest. I think poetry and CNF are incredibly alike; the latter simply appears in prose form. But even then, there’s so much experimentation allowed, and encouraged, in CNF that I feel at home when writing in the genre. I think poets and CNF writers are lucky in that regard. Of course, if a poet is writing really esoteric stuff that has no confessional or narrative elements at all, then I think it would be more difficult for that person to write CNF. However, that’s an edge case—most poets I know have at least tried to write a personal essay!

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Funny for you to ask this after I’ve already outed myself as somebody who doesn’t write every day! My answer, then, is that I don’t have a routine. Sure, I shouldn’t rely too much on moments of inspiration, but I do have some semblance of a structure in mind when I write. For instance, my bare-minimum goal every month is to write one full poem. Most of the time, I end up writing two, or even more, pieces in a month, so it ends up working out for me. Also, even if I’m not writing a poem, I still think and see like a poet every day, that is, I engage with the world, as well as with my interior self, in a deep, reflective way. This practice ensures that I always have ideas to write about and that my poems have fresh images.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Here’s the thing: I don’t believe in writer’s block, so I don’t believe in, well, such stalls. I write when I want to, meaning that I don’t feel stalled or blocked when I’m composing. If I weren’t in the mood to write, I wouldn’t be writing anyway. Maybe this is a cavalier attitude, but I’m not the type of person to force something to happen. Of course, when I write in an academic or professional setting, I must compose at inconvenient times, so there might be some blocks there, but creatively speaking? Nope, I try to enjoy the ride.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I’d have to say petrichor, or the smell of rain on dry earth. I’ve called Nevada my home for many years now, which is the driest state in the US, so when it rains, it’s a memorable experience, replete with a memorable aroma. I’ve yet to find a candle that perfectly replicates this smell, so if you know of one, please let me know!

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, all of the above! The landscapes of the American West, particularly across northern Nevada, are a work of art unto themselves and deeply inspire my poetry. In fact, my entire first book is set against the backdrop of the West, with deserts and mountains galore. I’ve also written poems directly inspired by ABBA and Orville Peck, as well as pieces that respond to scientific phenomena—like the formation of mountains via tectonic plate collisions or the Pauli exclusion principle in physics—or to visual art (I love me an ekphrastic poem!).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Definitely Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf, two women I have, literally speaking, tattooed on my thighs. (This was the inspiration for my poem “Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf Talk on My Thighs.”) I’m also inspired by Chen Chen, Ocean Vuong, C. T. Salazar (whom I proud to call my friend!), Janine Joseph (my PhD advisor), and many others.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d really love to visit Mexico. I’ve talked to my partner about this (in a casual way, of course), and he’s down to go as well. I’ve been reading lots of Silvia Moreno-Garcia books set in Mexico recently, and I feel an intimate connection to the country. Maybe it’s because I love the deserts of Nevada so much that, well, any other place that reminds me of home is appealing to me. (I also feel a strong connection to Australia’s Northern Territory for this exact reason.)

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Had I not pursued poetry, I’d probably be an art historian. I absolutely adore art, but more than that, I love learning about the sociohistorical context that surrounds a work of art, as well as the different artifacts the art dialogues with. Fortunately, I’ve gotten to study art history a bit anyway throughout my academic career, but yeah, if I didn’t love poetry so much, I’d put all of my eggs (or at least more of them) in the art history basket.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was a boy! What a sappy story, right?! But seriously, I wrote my first “serious” poem at the age of 17 because I was in love with a boy. Ever since then, I haven’t looked back. In high school, that is, pre–being in love with said boy, I thought I was going to be a doctor or a scientist, and I took all the AP and honors science classes to prepare me for that career path. (I was good at them, too!) However, I’d always been good at writing, and I’d always liked to do it, so even if I hadn’t fallen in love with that one boy, I probably eventually would’ve switched over to writing—it just would’ve taken a few more years.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

For the book, I’d have to say Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. This novel knocked my socks off. It really turns the horror genre, specifically the haunted house subgenre, on its head. I was gripped by suspense the whole time I read it. I highly recommend this book to everybody—and yes, even to those who say they don’t like horror! As for the film, this is a bit tougher for me to say, but I’m going to go with Supernova. I’m a big Colin Firth fan, and while this movie features two straight men in a gay onscreen romance, I was captivated. Plus, I love that this particular film doesn’t center the couple’s queerness, that is, it’s about their struggles, and they happen to be queer.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m presently writing and ordering my second full-length poetry manuscript, tentatively titled Mix-Mix, a poetic exploration of my mixed-race heritage. It features a lot of reformulated archival text (like from my late father’s Asian Romance Guide to Marriage by Correspondence handbook), as well as reformulations of verbiage taken from my AncestryDNA Story. I also explore many topics related to my Filipinx ancestry that I haven’t written about before, so that’s exciting. I hope to have this collection finished in the next couple of years!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

November 29, 2021

Yesterday, not my photo

1.

This tornado’s funnel kiss along the waters of Lake Huron.

Port Albert beach: a foreign language might be stripped

of borders, nothingness. The air thins, tinny. The scent

of low pressure vacuum. The hairs on each arm.

2.

When Amy and Andrew visited, he and I each gathered

our combined small children—two

toddlers, two infants—for a playground jaunt. I caught

the shift in the air and said, we have to go. We held

our boundaries. This onslaught of rain. We barely made

it back to the house.

3.

Environmental. I wish to make my questions

known, from lifted references. My beloved clash.

I found this image on the internet, I no longer

remember where. But it makes my point.

Displacement: where the rain meets silence,

where the word meets open space. The calm

converts to lawn.

November 28, 2021

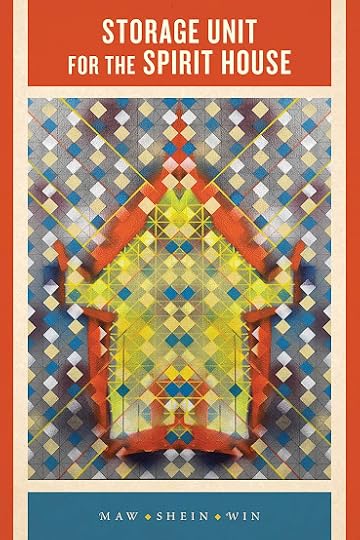

Maw Shein Win, Storage Unit for the Spirit House

Theater in Three Acts

where are the minnows

song of gongs in mini-mall

what happens to the body after soliloquy

mine in mottled fur coat

when does the future arrive

birthmark on forehead in shape of flame

California poet Maw Shein Win’s second full-length collection, following the chapbook

Score and Bone

(Nomadic Press, 2016) and the full-length debut

Invisible Gifts: Poems

(Manic D Press, 2018), is

Storage Unit for the Spirit House

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2020), a collection composed in short sketches, writing the small moments and perspectives that form together to articulate a particular stretch of both the external and internal workings of a life being fully lived. In a dense and sketched-out lyric, hers is a poetic of accumulated dailyness, a lyric journal of dreams and domestic composed via shorter units of precision around ordinary extraordinariness. She writes portraits of medical appointments, local landmarks, storage units and strange dreams, a litany of family and subconscious images, children who won’t sleep and a house on the lake. “she runs on four legs along a dry / river bed,” she writes, to close the poem “Bottle,” “mother sleeping // the sun blinking / the scar questions // why why the chickens / why why jam & eggs // why why the hand /caught in a bottle of laughter [.]” There are points at which her portraits lean into the dream-like and surreal, offering different levels of concrete detail, all while offering an otherworldly portrait, it would seem, of what might otherwise be considered uniquely and innately familiar. “tinctures for pain,” she writes, to open the poem “Hospital,” “capsized vessels / hand reaches into warm body / she believes in magic & so do I / painted things [.]”

California poet Maw Shein Win’s second full-length collection, following the chapbook

Score and Bone

(Nomadic Press, 2016) and the full-length debut

Invisible Gifts: Poems

(Manic D Press, 2018), is

Storage Unit for the Spirit House

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2020), a collection composed in short sketches, writing the small moments and perspectives that form together to articulate a particular stretch of both the external and internal workings of a life being fully lived. In a dense and sketched-out lyric, hers is a poetic of accumulated dailyness, a lyric journal of dreams and domestic composed via shorter units of precision around ordinary extraordinariness. She writes portraits of medical appointments, local landmarks, storage units and strange dreams, a litany of family and subconscious images, children who won’t sleep and a house on the lake. “she runs on four legs along a dry / river bed,” she writes, to close the poem “Bottle,” “mother sleeping // the sun blinking / the scar questions // why why the chickens / why why jam & eggs // why why the hand /caught in a bottle of laughter [.]” There are points at which her portraits lean into the dream-like and surreal, offering different levels of concrete detail, all while offering an otherworldly portrait, it would seem, of what might otherwise be considered uniquely and innately familiar. “tinctures for pain,” she writes, to open the poem “Hospital,” “capsized vessels / hand reaches into warm body / she believes in magic & so do I / painted things [.]” There is something curious about how certain of her poems are structured: stanzas single and even double-spaced within, but larger spaces between, akin to different sections/stanzas existing as a self-contained call-and-response, offering both perspective and reflection. Her play of space on the page allows for different levels of pause, break and connection, offering not, I suppose, hesitation, but levels of connection and commentary, such as the poem “Imaging Center,” that reads, in full:

the pointer stick she grips

trails my twisting spine

she plots movement

with the exactness of a fingertip

slow as the motion of a snail in love

my naked back on treatment table

coolness hardening into memory

The poem-portraits captured as part of her Storage Unit for the Spirit Houseeach offer perspectives of moments large and small—everything that goes through the mind as her narrator moves through the world and her day—each poem oriented to the detail of their individual frame; the gaze of her poems expand and contract, offering both the larger view and one so close it can only exist within. As the first half of the poem “Phone Booth” offers: “a Brownie camera slung around a sweaty neck // telephone wires crisscross // you didn’t hear that did you? you did not didn’t you? // child in a burlap cape leaps through the garden [.]” The poems are not set as a scrapbook, but as a photo album of memories, moments and ideas. “how does a painting speak?” she asks, as part of the poem “Diorama,” “language is the difference / among three things // who enters the spectacle? the brave ones with their silk skirts [.]”