Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 144

December 1, 2021

Ongoing notes: early December 2021: Christy Davids + Nikki Reimer/Andrea MacKenzie Engele,

I seem to be on a roll these days, it would seem. Chapbooks?

I seem to be on a roll these days, it would seem. Chapbooks? And you are keeping an eye on what’s been going on over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, yes? And Touch the Donkey? And many gendered mothers? And above/ground press? And the weekly interviews via the Chaudiere Books blog?

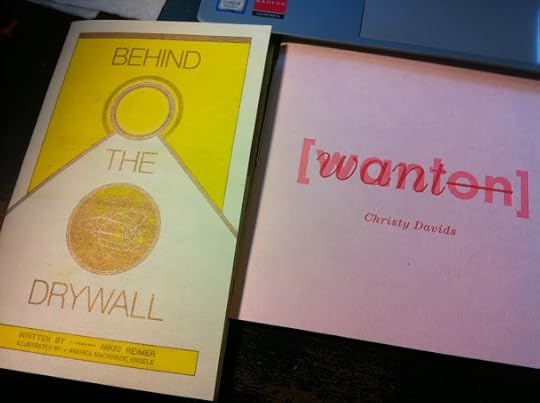

Brooklyn NY: It is good to see a new chapbook title by American poet Christy Davids [see her “Tuesday poem” here], her wanton(DoubleCross Press, 2020), a chapbook-length poem-sequence of accumulated lyric fragments that play with information and commentary around female desire, sexual fantasy, reproductive biology and Craigslist-like personals: “wanted edgy alternative tattooed nerd girl wanted single local / female wanted rough or ravaged wanted reversing role and using / strap-on wanted steady girl for bj weekly wanted something more [.]” There is less a sense of commentary here than simply offering a collage of related information and perspectives, bringing together a series of scraps and fragments to cohere into a larger shape. How does one idea relate to the next? How does one idea determine what follows? As her first footnote, to the line “I can appear fertile,” offers: “A 2006 study in the journal Hormones and Behavior found that women who had their pictures taken during fertile and non-fertile stints were judged to be trying harder to look nice on fertile days, suggesting the hormonal boost of ovulation may translate to real-life decision-making.” Given she has now produced a handful of small chapbooks over the past few years, one can only hope that Davids’ is working toward something full-length.

we are taught (re)production determines

the social value of female bodies, so

I can secrete with discretion

warrant only instances

of mating and sheer

prettiness, perpetual

arousal carousel

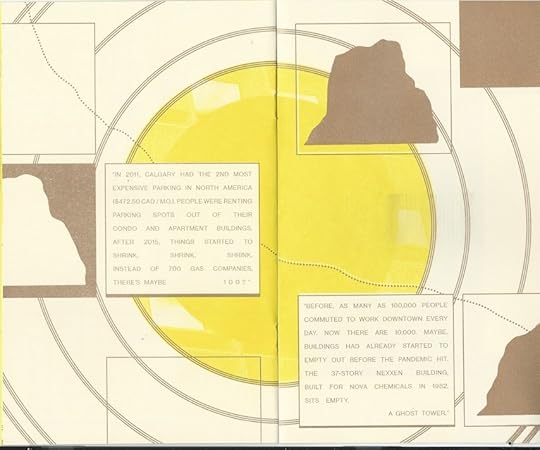

Calgary AB: How does one even discuss, properly, this new chapbook title by Calgary poet Nikki Reimer, BEHIND THE DRYWALL (Gytha Press, 2021)? “Written by Nikki Reimer / Illustrated by Andrea MacKenzie Engele,” BEHIND THE DRYWALL is a title that communicates in tandem, almost in collaboration, between the writer and illustrator/designer. BEHIND THE DRYWALL is composed as a lyric collage set to an illustrated, visual music, offering a critique of Alberta’s oil and gas industry, Calgary’s self-identifications and self-delusions, as well as the capitalist bent that has reduced an expansive and overly-aggressive construction into a downtown abandoned by humans. Hers is a Calgary caught between bust and boom, and the human expense of whichever side of the coin is in current play. In certain ways, Reimer and Engele’s BEHIND THE DRYWALL is a language-driven capitalist collaboration and collage update of Calgary writer Aritha van Herk’s infamous 1987 long poem, “Calgary, this growing graveyard,” which is, once one considers the comparison, a frustrating one, given how little improvement has followed, over those intervening years.

November 30, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dani Putney

Dani Putney

is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race Filipinx, & neurodivergent writer originally from Sacramento, California.

Salamat sa Intersectionality

(Okay Donkey Press, May 2021) is their debut full-length poetry collection. Their poems appear in outlets such as Empty Mirror, Ghost City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Juke Joint Magazine, & trampset, among others, while their personal essays can be found in journals such as Cold Mountain Review & Glassworks Magazine, among others. They received their MFA in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women & are presently an English PhD student at Oklahoma State University. While not always (physically) there, they permanently reside in the middle of the Nevada desert.

Dani Putney

is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race Filipinx, & neurodivergent writer originally from Sacramento, California.

Salamat sa Intersectionality

(Okay Donkey Press, May 2021) is their debut full-length poetry collection. Their poems appear in outlets such as Empty Mirror, Ghost City Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Juke Joint Magazine, & trampset, among others, while their personal essays can be found in journals such as Cold Mountain Review & Glassworks Magazine, among others. They received their MFA in Creative Writing from Mississippi University for Women & are presently an English PhD student at Oklahoma State University. While not always (physically) there, they permanently reside in the middle of the Nevada desert.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It’s difficult to think that my first book changed my life in any significant way. I know some folks expect something to feel different post-publication, but it’s pretty much the same for me: write, revise, submit, repeat. No glory. (But then again, I don’t think most writers do it for glory...) However, my most recent work, especially the poems I’ve written since my book was accepted for publication at Okay Donkey Press, is very different tonally than the pieces in my collection. Perhaps it’s a more “mature” voice, but in any case, I feel that the speaker (or speakers, rather) I write into my poems now view the world, and themselves, much differently than before.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually didn’t come to poetry first! Like many writers, I started writing fiction first, but it quickly became apparent to me that the genre was, well, too prosaic. Too many words, too much time wasted. I wanted narrative to be in my work, sure, but the narratives of fiction felt too constraining to me. Poetry was the next genre I toyed around with, but it stuck—it made the most sense to me. I also write creative nonfiction, but when I was first starting out as a writer about 8 years ago, I wasn’t too familiar with the genre. Now, whenever I have an idea that’s too long for a poem, I turn to CNF to meander a bit; I mean, the word “essay” does come from “assay,” to experiment.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I suppose the best answer is “all of the above.” Sometimes I write poems very quickly, in less than an hour, but they usually take me several hours or a few days. Now, when I say “several hours or a few days,” I’m talking about the exact amount of time I spend writing a poem, not the in-between or break periods. With that in mind, it could easily take me, say, 10+ hours to crank out a “first” draft of a poem. But I suppose all the hours I spend on the front end ultimately mean I take less time on the back end, that is, during revision. Even after receiving lots of wonderful feedback on a poem from a workshop, for example, the revision period for that poem, at that particular point in time, might only be about 2 or 3 hours. I’m the type of person to meticulously craft something so that it appears pretty solid from the outset, but I still spend a good amount of time revising my work afterward. I’m just not, you know, somebody who can sit at a desk and sprawl; I’m always in the process of crafting my poetry.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems almost always begin as small phrases I write down in the notes app of my phone (which I lovingly refer to as my “journal”). For example, I recently wrote a poem about balikbayan boxes, a piece that started as the word “balikbayan” in my journal. I wrote this word down right after I’d walked by an LBC. (To give some context, balikbayan boxes contain items sent from overseas Filipinos to their family and friends in the Philippines. LBC is a popular Philippine courier service with many branches in the US.) You can essentially apply this process to, say, 80 percent of my poetry. However, I sometimes work on longer, multi-poem projects, which, of course, require more advance planning. As for writing with a book in mind, I think I always do that! When writing my first collection, for instance, I always thought about which poems could appear in the book and how I could eventually order it. Lots of pieces didn’t make the cut, but I was always thinking about the final “product,” if you will.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love me a good reading! I’m such a natural performer that any attention I can get gives me energy and life. It helps that I’m an ENFJ (if you know your Myers–Briggs personality types), with the “E” meaning “extroverted,” so I thrive at public readings with other poets and writers. I also think that there are so many bad readers out there—really, even some of the greatest writers are terrible at publicly reading their work—so I always come to a reading with the mindset that (1) I don’t want to suck and (2) I want to give somebody an experience, something they couldn’t get on the page alone. I think the fact that I mainly write poetry helps, too, because it started many years ago as an oral art anyway.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’d say theory is always at the back of my mind when I write poetry. Much of my first book, for example, dialogues with and reflects on ideas popularized by various philosophers and, more specifically, literary theorists. One of the poems in my collection ruminates on the mirror stage, a concept from Jacques Lacan. Another poem in my book is a direct address to Judith Butler’s earlier work regarding gender theory. Getting even more esoteric, I have a poem called “Jouissance” in the book that engages with Leo Bersani’s concept of the same name, as explored in his essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?” I wouldn’t say I’m answering any particular questions so much as I’m extending these theorists’ lines of thought and, more than that, appropriating their ideas to reflect on my own sense of identity as a poet. Specifically, much of the theory-focused poems in my collection deal with facets of my intersectional identity: my queerness, non-binary gender, etc.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t think writers have a specific societal role. To me, writing is a very selfish thing—but not in a bad way! I’m so glad I have readers who enjoy my work, but at the end of the day, I write for me. Publishing my work is an afterthought, not the impetus for writing. However, if I had to think of one thing writers do well in terms of larger culture, I’d have to say that they provide representation in a way that helps to make the world a more empathetic place. Of course, it’s a more complex phenomenon than simply encouraging empathy, but if we didn’t have writers, you know, selfishly writing about their complicated identities or sharing their experiences, then people would be much more in the dark about others’ diverse perspectives, I think.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Definitely essential. The suggestions I received from the editorial team at Okay Donkey Press helped make my book an even better, well-rounded collection. We reordered some parts, added some poems, and took out a couple of pieces. I didn’t expect to receive such care for and attention to my poetry, but Genevieve and Matt at OKD gave me that and more. I understand the resistance to editors looking at one’s work, especially if one thinks the piece is “finished,” but trust me, they almost always have something helpful to add.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This is tough because I tend to think about all the bad advice writers receive! But if I had to choose one thing, I’d say it was when I was reaffirmed that I didn’t have to write each day. I’ve never been somebody to write every day, so hearing another person say it was okay to do so when, well, I’d been told for a long time that “good” writers were putting in daily work was very uplifting for me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Not that difficult, to be completely honest. I think poetry and CNF are incredibly alike; the latter simply appears in prose form. But even then, there’s so much experimentation allowed, and encouraged, in CNF that I feel at home when writing in the genre. I think poets and CNF writers are lucky in that regard. Of course, if a poet is writing really esoteric stuff that has no confessional or narrative elements at all, then I think it would be more difficult for that person to write CNF. However, that’s an edge case—most poets I know have at least tried to write a personal essay!

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Funny for you to ask this after I’ve already outed myself as somebody who doesn’t write every day! My answer, then, is that I don’t have a routine. Sure, I shouldn’t rely too much on moments of inspiration, but I do have some semblance of a structure in mind when I write. For instance, my bare-minimum goal every month is to write one full poem. Most of the time, I end up writing two, or even more, pieces in a month, so it ends up working out for me. Also, even if I’m not writing a poem, I still think and see like a poet every day, that is, I engage with the world, as well as with my interior self, in a deep, reflective way. This practice ensures that I always have ideas to write about and that my poems have fresh images.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Here’s the thing: I don’t believe in writer’s block, so I don’t believe in, well, such stalls. I write when I want to, meaning that I don’t feel stalled or blocked when I’m composing. If I weren’t in the mood to write, I wouldn’t be writing anyway. Maybe this is a cavalier attitude, but I’m not the type of person to force something to happen. Of course, when I write in an academic or professional setting, I must compose at inconvenient times, so there might be some blocks there, but creatively speaking? Nope, I try to enjoy the ride.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I’d have to say petrichor, or the smell of rain on dry earth. I’ve called Nevada my home for many years now, which is the driest state in the US, so when it rains, it’s a memorable experience, replete with a memorable aroma. I’ve yet to find a candle that perfectly replicates this smell, so if you know of one, please let me know!

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, all of the above! The landscapes of the American West, particularly across northern Nevada, are a work of art unto themselves and deeply inspire my poetry. In fact, my entire first book is set against the backdrop of the West, with deserts and mountains galore. I’ve also written poems directly inspired by ABBA and Orville Peck, as well as pieces that respond to scientific phenomena—like the formation of mountains via tectonic plate collisions or the Pauli exclusion principle in physics—or to visual art (I love me an ekphrastic poem!).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Definitely Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf, two women I have, literally speaking, tattooed on my thighs. (This was the inspiration for my poem “Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf Talk on My Thighs.”) I’m also inspired by Chen Chen, Ocean Vuong, C. T. Salazar (whom I proud to call my friend!), Janine Joseph (my PhD advisor), and many others.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d really love to visit Mexico. I’ve talked to my partner about this (in a casual way, of course), and he’s down to go as well. I’ve been reading lots of Silvia Moreno-Garcia books set in Mexico recently, and I feel an intimate connection to the country. Maybe it’s because I love the deserts of Nevada so much that, well, any other place that reminds me of home is appealing to me. (I also feel a strong connection to Australia’s Northern Territory for this exact reason.)

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Had I not pursued poetry, I’d probably be an art historian. I absolutely adore art, but more than that, I love learning about the sociohistorical context that surrounds a work of art, as well as the different artifacts the art dialogues with. Fortunately, I’ve gotten to study art history a bit anyway throughout my academic career, but yeah, if I didn’t love poetry so much, I’d put all of my eggs (or at least more of them) in the art history basket.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was a boy! What a sappy story, right?! But seriously, I wrote my first “serious” poem at the age of 17 because I was in love with a boy. Ever since then, I haven’t looked back. In high school, that is, pre–being in love with said boy, I thought I was going to be a doctor or a scientist, and I took all the AP and honors science classes to prepare me for that career path. (I was good at them, too!) However, I’d always been good at writing, and I’d always liked to do it, so even if I hadn’t fallen in love with that one boy, I probably eventually would’ve switched over to writing—it just would’ve taken a few more years.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

For the book, I’d have to say Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. This novel knocked my socks off. It really turns the horror genre, specifically the haunted house subgenre, on its head. I was gripped by suspense the whole time I read it. I highly recommend this book to everybody—and yes, even to those who say they don’t like horror! As for the film, this is a bit tougher for me to say, but I’m going to go with Supernova. I’m a big Colin Firth fan, and while this movie features two straight men in a gay onscreen romance, I was captivated. Plus, I love that this particular film doesn’t center the couple’s queerness, that is, it’s about their struggles, and they happen to be queer.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m presently writing and ordering my second full-length poetry manuscript, tentatively titled Mix-Mix, a poetic exploration of my mixed-race heritage. It features a lot of reformulated archival text (like from my late father’s Asian Romance Guide to Marriage by Correspondence handbook), as well as reformulations of verbiage taken from my AncestryDNA Story. I also explore many topics related to my Filipinx ancestry that I haven’t written about before, so that’s exciting. I hope to have this collection finished in the next couple of years!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

November 29, 2021

Yesterday, not my photo

1.

This tornado’s funnel kiss along the waters of Lake Huron.

Port Albert beach: a foreign language might be stripped

of borders, nothingness. The air thins, tinny. The scent

of low pressure vacuum. The hairs on each arm.

2.

When Amy and Andrew visited, he and I each gathered

our combined small children—two

toddlers, two infants—for a playground jaunt. I caught

the shift in the air and said, we have to go. We held

our boundaries. This onslaught of rain. We barely made

it back to the house.

3.

Environmental. I wish to make my questions

known, from lifted references. My beloved clash.

I found this image on the internet, I no longer

remember where. But it makes my point.

Displacement: where the rain meets silence,

where the word meets open space. The calm

converts to lawn.

November 28, 2021

Maw Shein Win, Storage Unit for the Spirit House

Theater in Three Acts

where are the minnows

song of gongs in mini-mall

what happens to the body after soliloquy

mine in mottled fur coat

when does the future arrive

birthmark on forehead in shape of flame

California poet Maw Shein Win’s second full-length collection, following the chapbook

Score and Bone

(Nomadic Press, 2016) and the full-length debut

Invisible Gifts: Poems

(Manic D Press, 2018), is

Storage Unit for the Spirit House

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2020), a collection composed in short sketches, writing the small moments and perspectives that form together to articulate a particular stretch of both the external and internal workings of a life being fully lived. In a dense and sketched-out lyric, hers is a poetic of accumulated dailyness, a lyric journal of dreams and domestic composed via shorter units of precision around ordinary extraordinariness. She writes portraits of medical appointments, local landmarks, storage units and strange dreams, a litany of family and subconscious images, children who won’t sleep and a house on the lake. “she runs on four legs along a dry / river bed,” she writes, to close the poem “Bottle,” “mother sleeping // the sun blinking / the scar questions // why why the chickens / why why jam & eggs // why why the hand /caught in a bottle of laughter [.]” There are points at which her portraits lean into the dream-like and surreal, offering different levels of concrete detail, all while offering an otherworldly portrait, it would seem, of what might otherwise be considered uniquely and innately familiar. “tinctures for pain,” she writes, to open the poem “Hospital,” “capsized vessels / hand reaches into warm body / she believes in magic & so do I / painted things [.]”

California poet Maw Shein Win’s second full-length collection, following the chapbook

Score and Bone

(Nomadic Press, 2016) and the full-length debut

Invisible Gifts: Poems

(Manic D Press, 2018), is

Storage Unit for the Spirit House

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2020), a collection composed in short sketches, writing the small moments and perspectives that form together to articulate a particular stretch of both the external and internal workings of a life being fully lived. In a dense and sketched-out lyric, hers is a poetic of accumulated dailyness, a lyric journal of dreams and domestic composed via shorter units of precision around ordinary extraordinariness. She writes portraits of medical appointments, local landmarks, storage units and strange dreams, a litany of family and subconscious images, children who won’t sleep and a house on the lake. “she runs on four legs along a dry / river bed,” she writes, to close the poem “Bottle,” “mother sleeping // the sun blinking / the scar questions // why why the chickens / why why jam & eggs // why why the hand /caught in a bottle of laughter [.]” There are points at which her portraits lean into the dream-like and surreal, offering different levels of concrete detail, all while offering an otherworldly portrait, it would seem, of what might otherwise be considered uniquely and innately familiar. “tinctures for pain,” she writes, to open the poem “Hospital,” “capsized vessels / hand reaches into warm body / she believes in magic & so do I / painted things [.]” There is something curious about how certain of her poems are structured: stanzas single and even double-spaced within, but larger spaces between, akin to different sections/stanzas existing as a self-contained call-and-response, offering both perspective and reflection. Her play of space on the page allows for different levels of pause, break and connection, offering not, I suppose, hesitation, but levels of connection and commentary, such as the poem “Imaging Center,” that reads, in full:

the pointer stick she grips

trails my twisting spine

she plots movement

with the exactness of a fingertip

slow as the motion of a snail in love

my naked back on treatment table

coolness hardening into memory

The poem-portraits captured as part of her Storage Unit for the Spirit Houseeach offer perspectives of moments large and small—everything that goes through the mind as her narrator moves through the world and her day—each poem oriented to the detail of their individual frame; the gaze of her poems expand and contract, offering both the larger view and one so close it can only exist within. As the first half of the poem “Phone Booth” offers: “a Brownie camera slung around a sweaty neck // telephone wires crisscross // you didn’t hear that did you? you did not didn’t you? // child in a burlap cape leaps through the garden [.]” The poems are not set as a scrapbook, but as a photo album of memories, moments and ideas. “how does a painting speak?” she asks, as part of the poem “Diorama,” “language is the difference / among three things // who enters the spectacle? the brave ones with their silk skirts [.]”

November 27, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lisa Summe

Lisa Summe

is the author of

Say It Hurts

(YesYes Books, 2021). She earned a BA and MA in literature at the University of Cincinnati, and an MFA in poetry from Virginia Tech. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Bat City Review, Cincinnati Review, Muzzle, Salt Hill, Verse Daily, West Branch, and elsewhere. You can find her running, playing baseball, or eating vegan pastries in Pittsburgh, PA, on Twitter and Instragram @lisasumme, and at lisasumme.com.

Lisa Summe

is the author of

Say It Hurts

(YesYes Books, 2021). She earned a BA and MA in literature at the University of Cincinnati, and an MFA in poetry from Virginia Tech. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Bat City Review, Cincinnati Review, Muzzle, Salt Hill, Verse Daily, West Branch, and elsewhere. You can find her running, playing baseball, or eating vegan pastries in Pittsburgh, PA, on Twitter and Instragram @lisasumme, and at lisasumme.com. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I wish this weren’t the case, but I definitely feel validated as a writer in a way that I didn’t pre-book. It’s also so nice when strangers reach out and tell you something positive they experienced when reading or hearing your poems. My book just came out this year, in January, but it’s been finished for a couple years now, and I’ve been working on other things. I finished a second manuscript in the fall, another collection of poems. I’d say it’s really different in that it’s just better. The poems feel a little more controlled and intentional. They’re just better because I’ve had more practice. In the second collection I’ve also delved into some topics I haven’t previously explored involving domestic violence, particularly in the home my mother grew up in, and the intergenerational trauma and grief that comes with that.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wanted to be a fiction writer once I switched to being an English major in college! But those workshops always filled up, every single term until I was a senior, so I settled for poetry, hoping to get a teacher who would talk to me about how to write a novel. Little did I know I’d never stop writing poems after that first class. Writing poems is what has actually changed my life.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I never think of writing as toward a project outside of assuming that once I have a big pile of poems I’ll make them into a book. The idea of starting anything new is pretty paralyzing for me, so I try to trick myself by doing very small steps like can you write a poem, any poem, this week. I was in a good rhythm for a couple years recently where I wrote a poem a week. A lot of those poems made up the second collection. My revisions don’t usually radically change a poem. If the poem sucks I just throw it away.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems happen different for me all the time, but usually it’s from making myself sit down and carve out the time for it. Sometimes I’m so stuck I just kind of journal until I say something complicated or interesting, then I try to latch onto that and make a poem. Better than that is coming up with a really interesting image or sentence while on a run or something, but that’s pretty rare for me. I always have to keep the mindset of just one poem at a time because I can only handle small tasks and goals, and so I’ve learned how to make big things small. The fun part of making a book, actually, isn’t writing toward a thing, but taking all the pieces and seeing how they talk to each other / what kind of story they tell.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I find giving readings to be pretty energizing but they don’t do anything for me in terms of my creative process really. It’s just nice to be in a room with other writers and seeing them do their thing. It’s nice to have someone tell you good job.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I never feel like I’m working to answer any questions on a large scale, though I, of course, hope my poems inform peoples’ feelings about major things, like love and grief and how one cannot or will not exist without the other. It feels a little too expected or easy or something for me to say that my concerns are feelings, mostly my own. Which are broad and both theoretical and not theoretical at all. Right now, I’m kind of obsessed with time and how it passes and how it can be measured very precisely and yet, depending on where a person is, physically in time and space, and where a person is emotionally, how we perceive time to be passing, the rate of it, is affected by those things. I don’t really know what to say about what the current questions are, but I hope, for all of us, writers or not, we’re thinking about how to live in a way that treats others (people, animals, the planet) kindly, and navigating that in a genuine way—there’s questions we all need to ask ourselves in order to do that.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think it’s similar to what I think, for me, is the role of literature, which is to provide emotionally honest perspectives on things so that readers become more imaginative and, therefore, more empathetic.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential, probably. Difficult, maybe. I only have one experience with YesYes for my one book, and it was really positive. The most difficult thing, I think, doesn’t have to do with the writing or editing at all, but maybe with people just having different organizational skills and approaches to completing tasks. I guess that’s true of any work environment.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Be nice to yourself.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t have a writing routine right now. What’s worked best for me is trying to write a poem a week. But I take months-years of breaks from doing that. I may be getting back into the swing of it now, but still feel kind of fried from a long stretch of writing from the last few years. Started taking an intentional break in December am not writing much these days. All my best days begin with avocado toast on seedy whole wheat sourdough and a run after a night in which I went to bed early.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I turn to books. The more poems I read, the more poems I write, usually. Alex Dimitrov, Matt McBride, and Wendy Xu are poets who come to mind, whose books I take off the shelf when I’m really struggling.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Anything that has just been cooked and is cooling by an open window.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Feelings lol.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Running is a big part of mental / emotional health maintenance for me that I think has helped me keep a somewhat clear head in which I’m able to kind of “organize” my feelings in a way that make sense for a poem, and helped me, too, I think with staying disciplined with writing when I choose to prioritize it, maybe from the high or the release that happens, maybe that helps me feel “motivated.” Reading books of poems and listening to music that make me feel excited about creating are important. All time fav poets are Alex Dimitrov, Olivia Gatwood, Hieu Minh Nguyen, Emily Skaja, Richard Siken, Danez Smith. But so many more, too.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get good at skateboarding. Learn to play the drums. Maybe write prose, but really I waver on that.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

This is such an interesting question. I always think of occupation as job as how you make money. I don’t make enough money from poems to live. If I did, that would be the dream for sure, I think, though there’s always the feeling of when something becomes your job maybe you don’t really like it anymore.

I started college as a dietetics major and have, in the last year or so, been toying around with the idea of going to nursing school, though right now, today, I don’t really think that’s something I’ll follow through with. I currently work an office job and I really don’t want to hang out a desk for the rest of my life, though working from home most of the time has changed my attitude quite a bit. I’m really into moving my body and a stationary job isn’t very good for me. Maybe I’d have gone to trade school for some kind of more physical job, which would suit me better, but I just went to college like everyone else around me did, like I was expected to. I would’ve never started writing had I not gone to college and then switched majors, but I also think college is kind of a scam, at least in the current model that puts many people in debt for the rest of their lives. I will also say I went to school for 9 years and have 3 degrees. So I mean I love school. I just think it’s fucked up everyone who wants to go doesn’t have the same opportunity to do that.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

How much I loved my freshman comp class in college.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve been reading a ton of poetry this year and have come across some real bangers. Two that stand out are Wound from the Mouth of a Wound by torrin a. greathouse (Milkweed Editions, 2020), and Pine by Julia Koets (Southern Indiana Review, 2021). I don’t see many movies. Promising Young Woman was pretty uncomfortable in a way I enjoyed. I liked that movie.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Giving 100% at baseball practice. Navigating nonmonogamy. Right now it’s April, and me and my girlfriend are trying to write a poem a week this month. I’m doing it but it’s taking everything in me.

November 26, 2021

Ongoing notes: late November 2021: Heather White + Michael Boughn,

More chapbooks! Hooray for this, yes? It is good that I’m finally seeing further appear in my mailbox (although now I have a mound of them I’ve yet to get to). Stay tuned!

More chapbooks! Hooray for this, yes? It is good that I’m finally seeing further appear in my mailbox (although now I have a mound of them I’ve yet to get to). Stay tuned! Montreal QC: I’m struck by this seeming-chapbook debut by Montreal writer Heather White, her chapbook DES MONSTERAS (Vallum Chapbooks, 2021). Subtitled “a long poem,” the eighteen poems within display a playfully-structured collage, folding in quotes by and elements of and around Mary Oliver, Taylor Swift and Paul Celan, among other references. “I roam the cold city with Taylor Swift,” she writes, mid-way through the collection, “singing voiceover. Her songs tell / their stories to the people in them.” The structure of the poems, as the back cover echoes, suggests poems quickly sketched via cellphone as journal notes, hastily written between thoughts as “both an insular retreat and an impulse to connect during the Montreal winter of the pandemic.” I’m curious about a number of things regarding White’s work: how far might this poem go, for example, beyond the boundaries of this debut publication?

signal bars|wi-fi|time|headphones|battery

<DES MONSTERAS share send

I slept and woke up remembering

that demonstratecomes from the

same root as monster. Both are

about pointing out or warning,

showing, montrer. A monster is a

messenger, often mistaken for the

message. A harbinger, coming

round the mountain, montagne:

nature’s pedestal. Mont Royal,

Montréal. What did I want this man

to put on a mountain for me?

Already his gaze released my face

from me for blissful long shifts. And

God knows how aching, how weary,

I’d become as the sole watchman of

my self, the last guardian of my

features, the one clerk left still

minding the store of my whole

buzzing, godforsaken body.

trash|list|photo|edit|new

Toronto ON: It is good to see that Toronto poet, editor and critic Michael Boughn is still producing chapbooks, the latest of which is The Battle of Milvian Bridge (shuffaloff, 2021), a playful and gymnastic eleven-part open-ended sequence around the Green Knight, a character from Arthurian lore that has lately fallen back into cultural awareness, thanks to the recent feature film, as well as Helen Hajnoczky’s recent Frost & Pollen(Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2021) [see my review of such here]. “Where’s the Green Knight,” the poem begins, “when you need him & his axe / to smarten up the Zeitgeist, when / the zeit’s geist is all / wham bam thank you ma’m, grab ‘em / by the— / well, Morgan Le Fay / might have a thing or two to say / about that […]” Boughn utilizes the legend of the Green Knight as a framework through which to mark and remark upon current affairs and cultural currency, language incursions, religious fervors and twisted meanings. As the sixth section ends: “nothing adds a depth / of understanding otherwise / circumscribed by judgement’s / geometry which brings the poem / back around to the Circular Slab / at the centre of our story / and the Green Knight / bearing news of the Hot Tamale [.]”

3. In Which The Mystery Ship Reappears

The absent ship sails by again

corposants merrily aflame

& signage boldly splayed

to let the poet know he made

a slip, & the elusive ship

is without a doubt Solomon’s

built at spousal request

(ah! the marriage bed)

to bear crown & sword

into story’s bleeding future

lances, fancy cups, the whole

round table schtick the Green

Knight brought to a quick

pause, the Cup recalling Morgan’s

judgment, a sign of eldritch

ledgibility, glyph’s untranslatable

clarity, indigestible scrawl

amid communication’s rubble

November 25, 2021

Amanda Moore, Requeening

Confession

In the chapel of our first days,

I put you to my breast again and again

and let you refuse me.

Half-life half-lived and with you

as my witness: I have been more

mother than woman. I have stayed up

all night lining the shelves of my life

with your toys and books.

It might be a comfort

the way my whole world spins

on the tip of your smallest toe,

but you will learn to be a woman

from the way I am a woman

in this world

and this is the litany

of my mistake.

From San Francisco poet and essayist Amanda Moore comes the full-length poetry debut,

Requeening

(Ecco/HarperCollins, 2021), 2020 winner of the National Poetry series, as selected by Ocean Vuong. Bees are, I’ve garnered, the earth-equivalent of the canary in a coal mine, and poets seem to return to bees fairly regularly, from Tonya M. Foster’s A Swarm of Bees in High Court(Brooklyn NY: Belladonna*, 2015) [see my review of such here] to Renée Sarojini Saklikar’s Listening to the Bees (Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2018) to Muriel Leung’s IMAGINE US, THE SWARM (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], among others. For Moore’s part, the figure and mantra of the bee follows from opening to central image: “This might have been the way I was born,” she writes, close to the beginning of the opening poem, “Opening the Hive,” “to move over my mother and wash from her / what was left of painful birth, her legs / like the old wood cracked with a hive tool, / my lips clamping and the bees burrowing / into honeycomb, bathed in sweetness, / a taste fresher when robbed this way.” She writes of the wisdoms and lessons passed from one generation to another, such as the poem “Sonnet While Killing a Chicken,” that opens: “The most important thing a girl can learn / is how to kill a chicken for a meal / to feed a man, so she begins to turn / the bird by neck and bound feet—this skill real, / precise, my mother wringing damp both towels / and snapping them on our rumps like the neck / snaps in the hand, wings sputter, bowels / release shit.” Moore writes of labour, industry, mothering, birth and daughters; a sequence of women and bees, and the physicality of bodies and work. “I prefer the mystery / of a bee’s body returning,” she writes, as part of “Waggle Dance,” “bright orange streaks of pollen / in the sacks on the backs of her legs // like fistfuls of hazy, polluted sun.”

From San Francisco poet and essayist Amanda Moore comes the full-length poetry debut,

Requeening

(Ecco/HarperCollins, 2021), 2020 winner of the National Poetry series, as selected by Ocean Vuong. Bees are, I’ve garnered, the earth-equivalent of the canary in a coal mine, and poets seem to return to bees fairly regularly, from Tonya M. Foster’s A Swarm of Bees in High Court(Brooklyn NY: Belladonna*, 2015) [see my review of such here] to Renée Sarojini Saklikar’s Listening to the Bees (Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2018) to Muriel Leung’s IMAGINE US, THE SWARM (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], among others. For Moore’s part, the figure and mantra of the bee follows from opening to central image: “This might have been the way I was born,” she writes, close to the beginning of the opening poem, “Opening the Hive,” “to move over my mother and wash from her / what was left of painful birth, her legs / like the old wood cracked with a hive tool, / my lips clamping and the bees burrowing / into honeycomb, bathed in sweetness, / a taste fresher when robbed this way.” She writes of the wisdoms and lessons passed from one generation to another, such as the poem “Sonnet While Killing a Chicken,” that opens: “The most important thing a girl can learn / is how to kill a chicken for a meal / to feed a man, so she begins to turn / the bird by neck and bound feet—this skill real, / precise, my mother wringing damp both towels / and snapping them on our rumps like the neck / snaps in the hand, wings sputter, bowels / release shit.” Moore writes of labour, industry, mothering, birth and daughters; a sequence of women and bees, and the physicality of bodies and work. “I prefer the mystery / of a bee’s body returning,” she writes, as part of “Waggle Dance,” “bright orange streaks of pollen / in the sacks on the backs of her legs // like fistfuls of hazy, polluted sun.” “Everything beautiful can be reduced // to scientific measurement:,” the same poem offers, to open, “this language / this dance // this swoop and waggle / across the hexagoned surface of comb [.]” The word “precarity” is utilized in Vuong’s blurb on the back cover, and Moore speaks to issues of health and other complications, writing a motherhood of bees and of just how easy the entire hive structure might simply collapse, and everything completely lost. Composing poems around the metaphor of bees, Moore writes of aunts, wasps, mothering and the lessons that emerge from each and all of the above, structuring her hard-won lessons through a variety of structures, from sonnets to a section of haibun to her carved accumulations of lyric couplets. And such hard lessons, certainly, through the ebb and flow of her prose lyric narratives, such as the opening of “20905 Caledonia Avenue Hazel Park MI,” that reads: “After tuning each floorboard / and scraping walls to chalky plaster // layering checkerboard tile and nailing / every shingle to the roof we made // a baby and I bore her in my body / until she broke me and we brought her there // where I milked myself each morning so happy / to make a home // for suffering, down to / the location even: the old place perched // on the edge of a city waking / from decades of cold dormancy.”

There is an attentiveness to Moore’s language; a precision to her explorations through mothers and bees, wasps and ants, and her own thoughts on mothering her own daughter. The slow evolution through the collection from writing of her mother to mothering to her own daughter is reminiscent of a couple of other titles over the years, most recently Silvina López Medin’s Poem That Never Ends (Essay Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. Moore writes not only of mothering, but of the shifts in perspective that emerge with the role. She writes of love, failure and exhaustion, and of moving through the accumulation into something akin to appreciation, and even wisdom and accomplishment, such as the end of the poem “Everything Is a Sign Today,” that offers: “The only difference / the season and time of day, which is to say / they are like this grief these months later: / all the same but for the light.”

November 24, 2021

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rebecca Salazar

Rebecca Salazar

(she/they) is a writer, editor, and community organizer living on the unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik. Published works include

sulphurtongue

(McClelland & Stewart),

the knife you need to justify the wound

(Rahila’s Ghost) and

Guzzle

(Anstruther). Salazar edits poetry for The Fiddlehead and

Plenitude

magazines, and co-hosts the Elm & Ampersand podcast.

Rebecca Salazar

(she/they) is a writer, editor, and community organizer living on the unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik. Published works include

sulphurtongue

(McClelland & Stewart),

the knife you need to justify the wound

(Rahila’s Ghost) and

Guzzle

(Anstruther). Salazar edits poetry for The Fiddlehead and

Plenitude

magazines, and co-hosts the Elm & Ampersand podcast. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

sulphurtongue feels like a private archive of everything I learned, unlearned, and grew through over a period of 12+ years. I have re-written it drastically multiple times, and it has changed so much from what I originally imagined to be—I think I needed to let it change me before I could write what it became, now.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I tried writing fiction first, but quickly realized I don’t currently have the skills to create and maintain plot. Poetry feels more fluid, less temporally bound, and more permissive of polyvocality. I do occasionally write non-fiction, but it feels less like switching modes and more like writing longer prose poems.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Most of the poems in sulphurtongue began as phone notes, fragments scribbled on scraps of paper, bits of conversation I overheard, and oral stories passed through my family that I tried and failed to research empirically, only to learn that the fragmentation was necessary to the truth they already contained. A few individual poems leapt into being fully formed, but those are very few—most of my poems have undergone multiple rounds of transformations.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Interruptions guide me: I start with fragments, try to puzzle out their general drive, become invested in that idea, and then inevitably end up changing course when something more urgent takes over what I thought was the initial project.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy sharing readings with other writers, especially with fellow queer and BIPOC writers. Getting to hear people read their work in their own voice—beyond what is available on the page—has helped me learn how embodied my own writing is. Readings can be anxious and fraught spaces, but the simple act of letting your voice resonate with others in your community matters more than most public readings seem to acknowledge.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’ll paraphrase two questions from years of study in feminist theory, queer theory, critical race theory, disability theory, and ecocriticism: 1. how to want to stay with a dying planet or body, and offer it care? 2. how to make a future in which my kin can do more than just survive?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To reduce it to one role would be to erase the skills and abilities of multiple kinds of writers, I think. There are writers who are educators and/or critics and/or activists and/or mentors to newer writers and/or leaders and/or healers and/or archivists and/or space-makers for those who have been erased and excluded. Not every writer can be everything, which is the beauty of finding which roles you yourself can perform.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential, but fraught. I have had the privilege of working with a few excellent editors—Dionne Brand, Triny Finlay, Mallory Tater, Katie Fewster-Yan, Ross Leckie. What is difficult is that I only found these editors after encountering a lot of abuse and tokenization in CanLit. If ever an editor or mentor undermines your autonomy, minimizes your identity, tokenizes your, or tries to fuck you, end that relationship. No writer should have to weigh the risk of being abused or taken advantage of, but that is the current difficulty of editing relationships in this community. I recommend Leah Horlick’s “Careful Inventory” columns on Open Book, which are a caring and honest look at the boundaries that poets need to stay safe—they are what I always needed to hear as a young writer.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This credit goes to a lifelong artist friend, Melanie Durette, who told me when we were about seventeen to never stop writing. I don’t think she realized how much it would mean to me for decades later.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

The kinds of non-fiction I am most drawn to feel like writing poetry—I mentioned already that non-fiction can feel like writing a longer prose poem. My process for both is similarly episodic, gathering fragments and voices and assembling them into something via associative logic rather than linear chronology. I think both are modes of connecting to what feels most urgent—not to say that fiction cannot do this, just that I personally haven’t succeeded in doing this with fiction.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Routine feels both necessary and unattainable in my writing and regular life, due to a combination of assorted freelance gigs, academic work, and chronic illnesses. I do have rituals that I use to put myself in writing mode—oolong tea, beeswax candles, tarot pulls, specific kinds of music—but keeping any kind of regular schedule is fickle.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I find myself re-writing old poems when I’m stuck, either splitting them into many new pieces or joining old fragments to try something new. I have found the pandemic an especially draining time, and have written very little in the last year. I try to understand this dry spell as a gathering period for whatever writing will come next.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Of the literal place: a pine forest on a summer night, with a hint of sulphur from the nearby mines. Of the concept: fresh-cooked rice and fried plantains.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Definitely—any art form that embodies the tone or sensations I want to write. It’s a synaesthetic process for me, in that every sound or texture has a colour for me, and that weighs into the way I channel things into writing. Music-wise, sulphurtongue was deeply influenced to Julia Kent, Lido Pimienta, Timber Timbre, FKA Twigs, Agnes Obel, Cold Specks, Valgeir Sigurdsson, Pallmer, and the Colombian folk songs and cumbias my family raised me in.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I keep a shelf of books, mostly poetry, that have changed or guided me most. To share just ten: Dionne Brand’s No language is neutral, Liz Howard’s Infinite citizen of the shaking tent, Joelle Barron’s Ritual lights, Billy-Ray Belcourt’s This wound is a world, Lauren Turner’s The only card in a deck of knives, Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, Kim Hyesoon’s Sorrowtoothpaste mirrorcream (translated by Don Mee Choi), an essay collection titled Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ Cien años de soledad, and literally every book written to date by Carmen Maria Machado.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

To abolish the white supremacist-colonial-capitalist hetero-patriarchy, and to live somewhere that I can start a garden.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I haven’t had the privilege of making a living wage from writing, so I have cobbled together a number of occupations to support myself since I started writing—bookstore inventory worker, part-time university instructor, apartment re-painter, editor, researcher for an academic theatre project, and more odd jobs than I can count. If I had the time and financial security, I would love to spend more time making visual art.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have joked before that I started writing as a way to compensate for starting school without speaking English, and I’m not sure it was entirely a joke. More seriously, I think writing is how I find ways to do everything else—it remains how I stay involved in academia, activism, therapy, spirituality, arts communities, everything.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: The Undying by Anne Boyer. Film: But I’m A Cheerleader, watched over video-call with two long-distance queer friends; somehow, none of us had seen it until now.

20 - What are you currently working on?

My dissertation, which includes a manuscript of poetry and a several essays-in-progress on ecological crisis, sexual trauma, and the struggle to imagine a kind future to survive in—that imagining is part of the work, too.

November 23, 2021

Tom Prime, Mouthfuls of Space

I Held Your Hand

walked a fog over the German Club’s

half-melted January waterfront

petrified by the raw-bone cheeks of god, two

police cars idled languid as alligators

under a crippled Moses-tree. we

walked for hours past ice-mud rivers. hot

sun. apple trees exist in purgatory

halcyon chickadees chirped bright

blossoming bloodroot

After a variety of solo and collaborative chapbooks, including his full-length collaborative volume with Gary Barwin,

A CEMETERY FOR HOLES, poems by Tom Prime and Gary Barwin

(Gordon Hill Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] (with a second volume forthcoming, it would appear), London, Ontario poet, performer and musician Tom Prime’s full-length solo poetry debut is

Mouthfuls of Space

(Vancouver BC: A Feed Dog Book/Anvil Books, 2021). Mouthfuls of Space is a collection of narrative lyrics that bleed into surrealism, writing of existing on the very edge, from which, had he fallen over completely, there would be no return. As a kind of recovery journal through the lyric, Prime writes through childhood abuse, poverty and trauma. “I am awarded the chance to die / smiling,” he writes, to close the short poem, “Capitalist Mysticism,” “clapping my hands [.]” Prime writes a fog of perception, of homelessness and eventual factory work, and an ongoing process of working through trauma as a way to return to feeling fully human. “I died a few years ago / since then,” he writes, to begin the opening poem, “Working Class,” “I’ve been / smoking cheaper cigarettes // I like to imagine I’m still alive / I can smoke, get drunk / do things living people do // the other ghosts think I’m strange / they busy themselves bothering people [.]” Or, as the last stanza of the poem “Golden Apples,” that reads: “if I loved you, it was / then, your pea-green coat and / fucked-up hair—staring out of nowhere / your cold October hands [.]”

After a variety of solo and collaborative chapbooks, including his full-length collaborative volume with Gary Barwin,

A CEMETERY FOR HOLES, poems by Tom Prime and Gary Barwin

(Gordon Hill Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] (with a second volume forthcoming, it would appear), London, Ontario poet, performer and musician Tom Prime’s full-length solo poetry debut is

Mouthfuls of Space

(Vancouver BC: A Feed Dog Book/Anvil Books, 2021). Mouthfuls of Space is a collection of narrative lyrics that bleed into surrealism, writing of existing on the very edge, from which, had he fallen over completely, there would be no return. As a kind of recovery journal through the lyric, Prime writes through childhood abuse, poverty and trauma. “I am awarded the chance to die / smiling,” he writes, to close the short poem, “Capitalist Mysticism,” “clapping my hands [.]” Prime writes a fog of perception, of homelessness and eventual factory work, and an ongoing process of working through trauma as a way to return to feeling fully human. “I died a few years ago / since then,” he writes, to begin the opening poem, “Working Class,” “I’ve been / smoking cheaper cigarettes // I like to imagine I’m still alive / I can smoke, get drunk / do things living people do // the other ghosts think I’m strange / they busy themselves bothering people [.]” Or, as the last stanza of the poem “Golden Apples,” that reads: “if I loved you, it was / then, your pea-green coat and / fucked-up hair—staring out of nowhere / your cold October hands [.]” Through the worst of what he describes, there remains an ongoing acknowledgment of beauty, however hallucinatory or surreal, and one that eventually becomes a tether, allowing him the wherewithal to eventually lift above and beyond the worst of these experiences. “we trudge across fields of hornet tails,” he writes, as part of the sequence “Glass Angels,” “planted by hyper-intelligent computer processors— / the moon, a Las Vegas in the sky // glow-worm light synthesized with the reflective / sub-surface of cats’ eyes [.]” Despite the layers and levels of trauma, there is a fearlessness to these poems, and some stunning lines and images, writing his way back into being. “life is a ship that fell / off the earth and now // floats silently in space,” he writes, to close the poem “Addictionary.” Or, towards the end, the poem “Immurement,” that begins: “I’m a large Tupperware container filled with bones [.]” The narrator of these poems has been through hell, but he does not describe hell; one could almost see these poems as a sequence of movements, one foot perpetually placed ahead of another. These are poems that manage that most difficult of possibilities: the ability to continue forward.

November 22, 2021

new from above/ground press: fifteen new/recent (September-November 2021) titles,

A Wolf Lake Chorus, by Phil Hall $5 ; how to count to ten, by Kevin Varrone $5 ; Whatever Feels Like Home, by Susan Rukeyser $5 ; G o n e S o u t h, by Barry McKinnon $5 ; The Northerners, by Benjamin Niespodziany $5 ; THE TRAVELING WILBURYS COLLECTION, by Ken Norris $5 ; W / \ S H: INITIAL CONTACT, by Terri Witek and Amaranth Borsuk $5 ; Hotels, by George Bowering $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #31 : with new poems by Brandon Brown, Rusty Morrison, Yoyo Comay, Stephen Brockwell, Melissa Eleftherion, Sue Bracken, Valerie Witte and Jessi MacEachern $8 ; G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] #19 : edited by Pearl Pirie : with new work by Cameron Anstee, Claudia Radmore, Lana Crossman, Rae Armantrout, Maxianne Berger, Rick Black, Charlotte Jung, Louisa Howerow, Anna Yin, Philomene Kocher, David Groulx, Monty Reid, Rob Taylor, Hifsa Ashraf, Geof Huth, Allison Chisholm, Michael Fraser, Phil Hall, Michael e. Casteels, Rich Schnell, Michael Dylan Welch, Janick Belleau, Sacha Archer and Chuck Brickley $8 ; STRAY DOG CAFÉ, by Ken Norris $5 ; ALL THAT IS SOLID MELTS IN YOUR MOUTH, by Franklin Bruno $5 ; SAYING “BOY” IN A WILDERNESS OF SONG, by Gary Barwin $5 ; Never Have I Ever, by Emily Izsak $5 ; Mushrooms Yearly Planner, by Jen Tynes $5 ;

A Wolf Lake Chorus, by Phil Hall $5 ; how to count to ten, by Kevin Varrone $5 ; Whatever Feels Like Home, by Susan Rukeyser $5 ; G o n e S o u t h, by Barry McKinnon $5 ; The Northerners, by Benjamin Niespodziany $5 ; THE TRAVELING WILBURYS COLLECTION, by Ken Norris $5 ; W / \ S H: INITIAL CONTACT, by Terri Witek and Amaranth Borsuk $5 ; Hotels, by George Bowering $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #31 : with new poems by Brandon Brown, Rusty Morrison, Yoyo Comay, Stephen Brockwell, Melissa Eleftherion, Sue Bracken, Valerie Witte and Jessi MacEachern $8 ; G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] #19 : edited by Pearl Pirie : with new work by Cameron Anstee, Claudia Radmore, Lana Crossman, Rae Armantrout, Maxianne Berger, Rick Black, Charlotte Jung, Louisa Howerow, Anna Yin, Philomene Kocher, David Groulx, Monty Reid, Rob Taylor, Hifsa Ashraf, Geof Huth, Allison Chisholm, Michael Fraser, Phil Hall, Michael e. Casteels, Rich Schnell, Michael Dylan Welch, Janick Belleau, Sacha Archer and Chuck Brickley $8 ; STRAY DOG CAFÉ, by Ken Norris $5 ; ALL THAT IS SOLID MELTS IN YOUR MOUTH, by Franklin Bruno $5 ; SAYING “BOY” IN A WILDERNESS OF SONG, by Gary Barwin $5 ; Never Have I Ever, by Emily Izsak $5 ; Mushrooms Yearly Planner, by Jen Tynes $5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

September-November 2021

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles (see the other two 2021 lists here and here), or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Forthcoming chapbooks by Joanne Arnott, Lydia Unsworth, Lillian Nećakov, Amanda Earl, Rob Manery, MLA Chernoff, Wanda Praamsma, df parizeau, Sarah Rosenthal, Mayan Godmaire, Vivian Lewin, Michael Schuffler, Karl Jirgens, James Yeary, Nate Logan, Sean Braune and Émilie Dionne, Simon Brown, Andy Weaver, Stan Rogal and Matthew Owen Gwathmey, as well as G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] #20, guest-edited by Edric Mesmer as Yellow Field #12!

and you should totally subscribe for 2022! can you believe the press turns 29 years old next year? gadzooks!

stay safe! stay healthy; wash your hands; be nice to each other,