Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 137

January 26, 2022

Lisa Samuels, Breach

a subcon-

trastic change

filiates barbells

make your arms

of co-captivity

duress

you dress

the part of civic

gendarme inhaled

‘I told you so’

in slabs on the front

lawn or fireball

muffled in the

basement dance

each cat arresting its

arithmetic

slumber

walks the walk

The latest from Lisa Samuels is the full-length

Breach

(Norwich England: Boiler House Press, 2021), a quintet of extended, numbered sequences, composed through punctuated sound, short lines of halting rhythms and accumulations. “Breach by Lisa Samuels performs a vital palilalia of lockdown. Starting with the dead, with Li Wenliang, who was the first to raise the Covid alarm, the book pitches and surges in deflections, hungers, and political feeling through pandemic-as-ordinary-life. The forced changes in relations we've all suffered derange the lines,” the online catalogue copy offers. “Breach is a song of lockdown: its tragedies, absurdities, non sequitur linguistic hilarities, and nightmarish lexical distortions, presented at a perfect moment for reflection, as we each continue adjust our bodies, lives and breaths...” Born and raised in the United States, but living and teaching in Aotearoa/New Zealand since 2006, where she is Associate Professor of English and Drama at The University of Auckland, Samuels has long been engaged with self-contained chapbook- and book-length projects for some time, shaping numerous of her collections around particular subjects and attentions to form, even as her work continues an ongoing experimentation, as well as, according to one online author biography, “transnationalism [as] fundamental in her ethics and imagination.” Some of her previous full-length works of poetry, memoir and prose include

The Seven Voices

(O Books, 1998),

Paradise for Everyone

(Shearsman Books, 2005),

The Invention of Culture

(Shearsman Books, 2008),

Tomorrowland

(Shearsman Books, 2009),

Mama Mortality Corridos

(Holloway, 2010),

Gender City

(Shearsman Books, 2011),

Wild Dialectics

(Shearsman Books, 2012),

Anti M

(Chax Press, 2013),

Symphony for Human Transport

(Shearsman Books, 2017),

Foreign Native

(Black Radish Books, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Long White Cloud of Unknowing

(Chax Press, 2019).

The latest from Lisa Samuels is the full-length

Breach

(Norwich England: Boiler House Press, 2021), a quintet of extended, numbered sequences, composed through punctuated sound, short lines of halting rhythms and accumulations. “Breach by Lisa Samuels performs a vital palilalia of lockdown. Starting with the dead, with Li Wenliang, who was the first to raise the Covid alarm, the book pitches and surges in deflections, hungers, and political feeling through pandemic-as-ordinary-life. The forced changes in relations we've all suffered derange the lines,” the online catalogue copy offers. “Breach is a song of lockdown: its tragedies, absurdities, non sequitur linguistic hilarities, and nightmarish lexical distortions, presented at a perfect moment for reflection, as we each continue adjust our bodies, lives and breaths...” Born and raised in the United States, but living and teaching in Aotearoa/New Zealand since 2006, where she is Associate Professor of English and Drama at The University of Auckland, Samuels has long been engaged with self-contained chapbook- and book-length projects for some time, shaping numerous of her collections around particular subjects and attentions to form, even as her work continues an ongoing experimentation, as well as, according to one online author biography, “transnationalism [as] fundamental in her ethics and imagination.” Some of her previous full-length works of poetry, memoir and prose include

The Seven Voices

(O Books, 1998),

Paradise for Everyone

(Shearsman Books, 2005),

The Invention of Culture

(Shearsman Books, 2008),

Tomorrowland

(Shearsman Books, 2009),

Mama Mortality Corridos

(Holloway, 2010),

Gender City

(Shearsman Books, 2011),

Wild Dialectics

(Shearsman Books, 2012),

Anti M

(Chax Press, 2013),

Symphony for Human Transport

(Shearsman Books, 2017),

Foreign Native

(Black Radish Books, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Long White Cloud of Unknowing

(Chax Press, 2019). Tell yourself stories of

perfection rot

fine documents

circa land

pools every

where transnational

circa newly won

bought chemicals

new fissures

in the antique documents

pouring in

between the cities

circa where the lumber

goes the slum plots

where you

not to ask for

bread

Structurally, one might say that hers is a restless and endlessly curious lyric, continually in motion, seeking out what else has yet to be explored, or solved. As she references the then work-in-progress during her 2020 Touch the Donkeyinterview:

Well, a new work that happened in the first lockdown here is titled Breach and is quite different from the TtD poems – it arrived unexpectedly across a few days of intense writing in relation to pandemic feeling. I had started a formal imitation exercise model for my poetry students and it turned into a book-length poem with very short lines, the kind of line brevity characteristic of the poet Pam Brown, whose style I was setting the students to imitate, though I suppose the Breach lines are closer to Tom Raworth’s in style. I almost never compose in such short lines, and I found the extreme enjambments and lexical parataxis delicious.

The pandemic, as Samuels is fully aware, doesn’t connect us, but simply reminds us of how interconnected and interlinked we have become, and Breach offers itself as one of what will eventually become a wealth of writing that engages with the current lockdowns and ongoing pandemic, and holds as one of the earlier published examples, alongside Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov’s il virus (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. Unlike Nećakov’s sequence, Samuels reaches back to the beginnings of public awareness, circling and cycling back to the late Li Wenliang (October 1986 – February 2020), the Chinese ophthalmologist who warned his colleagues about early COVID-19 infections. In turns she writes slant and direct, offering degrees of perception, she writes “someone who’ll / sit and tether to / mobility / what continuous / education?” Contagion and discourse breeds, after all, and Breach offers a cycle that continually returns to that central break, through poems riffing and rolling and prompted by the beginnings of this particular period, and seemingly-endless present. “even if the news / turns,” she writes, towards the end of the collection, “it won’t alter [.]” As she knows full well, the cases mount. The present loops, repeats, and continues.

oh I have to

Li Wenliang

although

one doesn’t know

just anything

without

the moan of some

home engine work

school friends in

delicate

nothing’s out of nature

parse of air

January 25, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Miranda Mellis

Miranda Mellis

is the author of Demystifications (Solid Objects); The Instead, a book-length dialogue with Emily Abendroth(Carville Annex); The Quarry (Trafficker Press); The Spokes(Solid Objects); None of This Is Real (Sidebrow Press); Materialisms(Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs); and The Revisionist (Calamari Press). She teaches writing, literature, and ecological humanities at The Evergreen State College.

Miranda Mellis

is the author of Demystifications (Solid Objects); The Instead, a book-length dialogue with Emily Abendroth(Carville Annex); The Quarry (Trafficker Press); The Spokes(Solid Objects); None of This Is Real (Sidebrow Press); Materialisms(Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs); and The Revisionist (Calamari Press). She teaches writing, literature, and ecological humanities at The Evergreen State College. How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Beginnings can go on for years. Sometimes a beginning gets worked over so much, so hard, that���s all there is. Beginning can feel precarious, so uncertain. A beginning is a kernel, an idea, a resonance of some kind, an attraction, an arrival, a rumor, an invitation. The middle space is more grounded, like when you know love is reciprocal and you can start to count on someone ��� when, in the story, you���ve got enough material to shape it, to work with. It���s also still indeterminate ��� how long might this be, or take?

Like starting to ask, in middle age, how long will I live?

Having been so preoccupied with just getting off the ground in the beginning of a story (or a life) one is still working out: what is this? Over time you begin to understand it (which is another beginning, as if every insight is a beginning), to know its shape, to be able to tack more knowingly, more intimately between chance and intentionality.

An edge may start to flicker into view ��� ���the sense of an ending��� ��� a horizon; a cliff; a place beyond which you���ll no longer write (or live); a closure that also opens out. Ending shapes everything that comes before and usually leads to more revisions, as the ending casts its light back; writing an ending is beginning all over again; seeing things anew (re/vision) is playful, rather than goal-oriented. Writing is more like an organism than a machine or tool in that sense. You don���t make it, plug it in, set it going, use it until it breaks. Instead you are created, you create, you change something, it changes you, in a symbiotic enacting, auto-poietic and transformational, of spiraling co-creative cyclicality.

How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I started out writing poetry and couldn���t understand why anyone would write fiction. How would anyone every decide what story to tell, among an infinity of possible narratives? I had a word for this: infinitivity. Fiction-curious, I took a weekend workshop with Rikki Ducornet.

She spoke of seeing an enormous jackrabbit in France, an impossible rabbit the size of a deer, and how that image became emblematic, a point of departure for writing. I wrote a piece in her workshop, as a way of exploring my skepticism about fiction (infinitivity). It was called ���Novellas by the Hour.��� It took place over 24 hours at 24 different moments: ���8:13AM ��� a squirrel sticks her head out of a gas pipe.��� ���9: 45PM ��� a veteran naps on a park bench; has a flying dream���, etc. I found pleasure pursuing these images, figments and fragments of diction, seeing where they might lead, what they might say. I wrote stories from that weekend onward.

Coming from poetry has shaped my approach to fiction. Love of and curiosity about language, about where it leads, interest in metonymy, sound, all that remains. I find writing about culture, writing essays, writing about what other people make and do a welcome respite from vicissitudes of fiction. Poetry is a constant, a way of thinking and being that we could describe, if we imagine it in relation to liberation movements, as a multilinguistic front line where opacity, difference, and multiplicity are at the fore.

How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The Revisionist (2007) was my first book and it did change my life, or in writing it I was changed. I was writing this strange book in the early 2000s very much in the minor key, taking up the positionality of someone paid to lie about climate change. This narrator was in my head as I tried to imagine the psyche of those who understood the dynamics of global warming and nonetheless lied, Exxon et al. (See Merchants of Doubt by Oreskes and Conway for a precis of the actions of the corporate mafia of the fossil fuel industry and their paid minions, terrorist members of what McKenzie Wark calls the ���carbon liberation front.���) Those executive facilitators of our current extinctions should be tried for war crimes. They have waged a war on all species, a war on animals, a war on futurity. My book was a response to the dissemination by the Bush administration of junk science about climate and the refusal of that administration to sign on to the Kyoto Protocol, an existentially disastrous mistake and a cause of despair. The Revisionist was very much a working through of environmental depression. I got revenge on my narrator by causing them to lose the capacity to perceive anything at all by the end, as a result of knowingly lying about climate change. That was almost 20 years ago. Think how different things might be now if the government had not been in bed with big oil, not only lying about climate change with propaganda campaigns, but invading Iraq on false pretenses to control the oil supply.

As for how my recent writing compares or connects, the venality, stupidity, and the infuriating, fatal incompetence of the reactionary capitalist state continues to be a source of inspiration. Ha ha! As we flee fires, floods, and droughts.

My current manuscript is a piece of forest writing that centers on a house sliding down a ravine due to monsoon rains and clear cuts which destroy stabilizing root systems causing mudslides and soil erosion. But it���s different from The Revisionist and other books in offering a vision of a good enough future, and pointing, in homage to The Dispossessed, to an ambivalent utopia.

Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a ���book��� from the very beginning?

I���ll start to draft something and often I just abandon it after a few revisions. (What about an anthology of most successful failed beginnings? Call it False Starts.) Other times the whole gesture is there. It���s compressed. One dream; one idea; one move; one scene. Other times something takes hold that���s too complex and indeterminate to sense its duration. It���s not a gesture, it���s a problem, a cluster-fuck, an open-ended question, something you���re going to be wrestling with for a while, that won���t let go of you, maybe for the rest of your life, for example grief.

Those can end up being ���books��� ��� I like that you���re putting quotation marks around that word. The quotation marks hold the telos of the ���book��� in suspense, in a state of potential. It���s fraught to have ���book��� in the mind, but it can also be generative, whether the imagined book comes to be or not.

Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Especially if sharing from a work in progress, public readings can become part of revision. Hearing the work out loud, anticipating real listeners, this can be clarifying, a tool for editing. You gain extra eyes, extra vision with that sense of address. If the work is complete ��� in a ���book��� ��� there are still questions about which parts you will read, in what order, and why, and you keep learning about how your writing registers in ways that might be surprising and that teaches you about the work itself, about the relationship between techniques and effects, especially comic effects, because you hear the laughter.

There are other things you can sense going on in the intersubjective space of a public reading, absorption, disinterest, identification, empathy, criticality, amusement, surprise, curiosity, judgment, care. You can also sense your own projections, what you imagine is going on; what you hope is going on; your own conflicts and intentions, your own befuddlement and absorption, curiosity and surprise, etc. Feeling into why you might feel drawn to reading one thing and not another at a given time develops sensitivity to what might be uncooked or overcooked in the work in progress.

Parts of your text can feel saturated for you, weighed down in a way that makes it difficult to read from. Conversely, it can be energizing (if also vulnerable and risky) to read something you���re unsure of, or haven���t read aloud before.

As for enjoyment, I���d say I have mixed feelings. You���re dealing with a whole range of things: how much sleep did you get the night before? How many other demands on your time, energy, and emotions were you dealing with that day? What shape are you in? People drink coffee, alcohol, take beta-blockers, find all kinds of ways to try to regulate themselves to be in the right frame of mind for appearing before a public. It can be terribly dysregulating. Readings can evoke a range of feelings, from enjoyment, excitement, curiosity and pleasure, to nerves, dread, shame and resistance. Over time one gets to know what the ride is like, as if a reading is a mind-altering substance: set and setting matter, but there is only so much you can control. After you���ve given a lot of readings over years, you���re not surprised by the feelings associated with the lead up, the range of things that can happen during a reading, and the roller coaster ride that it can sometimes be. You learn to phase shift, to discern, and not to get too caught up in any of it.

Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The disability and premature death of my mother, who was a communist, an activist, a teacher, an actress and a single mother (so a really complex interesting person who I didn���t get to know for as long as I wish I could have) is what started me writing seriously. Death is still my subject, but presently I am writing about it, in a manuscript called Two Problems in Three Parts, in different contexts: the context of sacrifice in a polarity with tyranny; and the context of ecologic in a polarity with industrialization.

Ecology and sacrifice are interrelated. Some people write (or live) towards an ending. Ending is a death, and deaths happen in a wide variety of ways. Some lives/stories have satisfying conclusions. They end with integration and closure. Others end abruptly, inconclusively, wrongly, unhappily, unfairly, tragically, suddenly, broken off, leaving wounds in their wake, so to speak.

Some endings allow for mourning to change its tenor. Others leave us with interminable, persistent melancholia.

The eco/logical way to think about it is that what dies is recycled, becomes and feeds new life. When we begin a new story, it is as if it begins where something else was left unfinished, as if every beginning points to something left. Something left that is usable is something that, in dying, gives itself to new life. It breaks down, is used, and is changed, rather than breaking and becoming an immutable, problematic object that can���t be used or changed, like tyrants who refuse to step down. Of what use is a tyrant who won���t give up power, to a democracy? Not only are they useless, they are toxic. The difference between squirrel bones or a gun, for example. Or a fallen tree, which feeds millions of microbes and life forms, and a microwave. Or a plastic bag thrown into a river which feeds nothing and no one, and chokes out life. Of what use are guns, microwaves, and plastic bags to the living biosphere? None whatsoever.

For life forms, every ending is a new beginning. For non-regenerative manufactured things, they never begin again, because they can���t rot, so they don���t accommodate change, and that is the true meaning of garbage. Nothing that can rot is truly garbage. Anything that can become something else, that can change, partakes of the genius of the living world and is not garbage. Only things that refuse to rot, to be transformed, to be changed are garbage, and they are filling up the world such that we have two worlds: a living world that self-regenerates, transforms, and symbiotically evolves through reciprocity, and a garbage world of tyrants, objects and toxins that don���t have lifespans but instead death spans: they are forever dead, never coming back to life, never changing. This is reflected in the culture of productivism, supported by necro-political, capitalist formations that require factories, mines, and extractive industries and police violence to enforce exploitation.

The normalization of all this produces people who misconstrue existence. A friend once told me about a neighbor of his who wanted all the trees on their street cut down because she thought of the leaves that fell from the trees, and the soil in which they grew, as garbage. Imagine how she feels about her body, which produces waste every day. But this would be a great person to write a story about, to do a character study of.

What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer is in a hard position. The culture doesn���t really support artists, so to be a committed artist is automatically to have to find a way to live against the grain. Artists are set up to compete, the way athletes are. In other professions, you learn your trade and hang a shingle, get a job. U.S. artists are precarious, have trouble getting a salary, getting work, and constantly have to scramble, unless they were born wealthy. That means that automatically privileged people have an advantage: they can make art, write, without worrying about how to make a living. Thus men of leisure with wives, servants, wealth have historically been very productive, and it���s no mystery why. It���s not because of any innate talent, it���s because they were free to do as they liked, supported by armies of working class people, including their wives: wives as servants.

Historically inequality resulted in men with tiny purview and very limited experience of life, having enormous platforms. Still to this day, some writers are rewarded over and over again in huge ways, while most struggle.

So my answer would depend upon the writer���s position. If you are someone who has already been highly rewarded, then stop hoarding awards, opportunities, social capital, prizes, grants, and start finding ways to redistribute the affordances that foster social ecologies in which working class and poor artists can make their work.

Don���t believe that those who are most rewarded are most talented and deserving, it���s simply not true. They are more likely the most well connected and the most economically advantaged. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young have done great research on the self-licking ice cream cone that is the literary prizes circuit. It���s shocking but not surprising. Coteries, schools and scenes are part of literary world-making. Social capital accrues as people reward each other and cliques build their reputations. It begins as community building rather than careerism. But when and as these scenes become reified, self-enriching, and self-involved, ethical contradictions must be addressed.

What is the best piece of advice you���ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Simone Weil: ���All true good carries with it conditions which are contradictory and as a consequence is impossible. Who keeps attention really ���xed on this impossibility and acts will do what is good.���

What fragrance reminds you of home?

As someone raised in San Francisco it would be fog, nasturtium, eucalyptus, wild fennel, gas fumes, pot smoke. I love this question. Thanks rob!

January 24, 2022

Michael Trussler, Rare Sighting of a Guillotine on the Savannah

of your attention once more My Single Lifetime in Exchange

for a Burst of your attention says everybody says

the dead utterly attentive entrepreneur so here’s some restorative

design Earth to Bauhaus Bauhaus to Earth come in

come in but nobody answers even today so breathe on these

very words right now and look your breath makes a grey fog

and these lines they in turn diagnose the denial that’s chronic

inside your chest our breathing

eventually becoming biodegradable

it’s a hassle and fun’s fun but isn’t

anyone gonna pick up the Goddamn ball offers

the dead entrepreneur Look around waking up these days is

so scattered waking up (“My Single Lifetime in Exchange for a Burst”)

I’m fascinated by the wide, slightly surreal narrative sweeps of Regina poet, fiction writer and critic Michael Trussler’s latest poetry collection,

Rare Sighting of a Guillotine on the Savannah

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2021). Following the poetry chapbook

Melancholy Girl with a Sitar

(Vancouver BC: The Alfred Gustav Press, 2020) and full-length

Accidental Animals

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2007), as well as a collection of short fiction,

Encounters

(Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2006), Trussler’s Rare Sighting of a Guillotine on the Savannah offers a rush of expansive lyric propelled by that which only poetry might allow, including ruminations on what Leo Tolstoy might have thought of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, to sketches around Rothko and Agnes Martin, and his recollections around the catastrophic eruption of Mt. St. Helen’s in May 1980. “I mean,” he writes, as part of “The Birds Now Suddenly Vanished,” “metaphysics / aside, I dimly remember // when Mt. St. Helens blew the day apart in Washington, but I didn’t know / then how / lava covered // Harry Truman and his 16 cats, his perfect bourbon / and coke, his lodge on Spirit Lake… [.]”

I’m fascinated by the wide, slightly surreal narrative sweeps of Regina poet, fiction writer and critic Michael Trussler’s latest poetry collection,

Rare Sighting of a Guillotine on the Savannah

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2021). Following the poetry chapbook

Melancholy Girl with a Sitar

(Vancouver BC: The Alfred Gustav Press, 2020) and full-length

Accidental Animals

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2007), as well as a collection of short fiction,

Encounters

(Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2006), Trussler’s Rare Sighting of a Guillotine on the Savannah offers a rush of expansive lyric propelled by that which only poetry might allow, including ruminations on what Leo Tolstoy might have thought of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, to sketches around Rothko and Agnes Martin, and his recollections around the catastrophic eruption of Mt. St. Helen’s in May 1980. “I mean,” he writes, as part of “The Birds Now Suddenly Vanished,” “metaphysics / aside, I dimly remember // when Mt. St. Helens blew the day apart in Washington, but I didn’t know / then how / lava covered // Harry Truman and his 16 cats, his perfect bourbon / and coke, his lodge on Spirit Lake… [.]” There is a curious layering effect Trussler employs in these poems, furthering an expansive narrative that turns and twists, offering the poem’s possibility through the sentence, as well as an interesting engagement with the ‘still life,’ exploring the narrative of the lyric to capture, possibly, the image of an idea. “Incoherence being the thread that joins us.” he writes, to open the poem “Everything Else is True.” In many ways, Trussler works his lyric as a form of exploratory thinking, seeking out his theses and thoughts as each poem unfolds, writing from a view that encompasses a wide range, from Saskatchewan rain to the Tokyo Marathon, translation to visual art, lettuce and the inflection of a child’s stomp. I’m enjoying the ease through which he shapes his explorations, shifting from lyric couplets to prose shapes and sonnets, seemingly very comfortable moving across form, including incorporating a variety of quoted texts to further propel both his arguments and narratives. Clearly, his years of teaching and academic work have provided him fuel, but not necessarily opportunity, for the explorations that drive his poetry, and his experience offers much insight, such as the prose piece “Zen and a Dinosaur,” a poem that opens “Home is what travels through us.” Further on, the poem reads:

Looking around the busy sunroom, this younger self would see that books have remained important. There are hundreds of them, in shelves and piled on the floor. Literature (poetry mostly), others on ecology, art history, philosophy, five or six concerning addiction, and an entire bookcase devoted to the Holocaust. Art postcards on the walls, binoculars on the desk facing a wall of windows, and a large photograph of a woman’s bare feet with the words welcome home painted on her toes. A stationary bicycle. Oddly, a few Polaroids. That both rooms are painted the same yellow is uncanny (not that he’d use this word): on the one hand, it feels exactly right, but, on the other, it’s slightly disturbing: don’t one’s tastes change or develop over time?

January 23, 2022

Niina Pollari, Path of Totality

Let me explain all the ways in which I felt embarrassed, even though it embarrasses me to say them. I felt embarrassed because I had let myself feel celebration and hope and joy, even though I now felt that I should have known better. I felt embarrassed that I had let everyone else know that a life as a mother to a live baby was something I desired. I felt embarrassed of my own certainty, which now felt foolish. I felt embarrassed that I would have to inform the world that what I desired was not going to be given to me, and that I had been let down. And I felt embarrassed of the embarrassment itself, as it centered my experience, and thus seemed selfish.

I’ve looked it up many times online, and found bewildered postpartum people writing on forums, asking why they felt embarrassed about losing their babies, asking whether anyone else felt that way. I’ve found that the tendency of the responders in the comments is usually to say You have nothing to be embarrassed about. This is because most of the responders have babies who are alive. Grief is complicated. What you’re feeling is normal. I don’t believe you. (“Embarrassment”)

American poet and translator Niina Pollari’s second full-length poetry title, following

Dead Horse

(Birds, LLC, 2015), is the devastating

Path of Totality

(Soft Skull Press, 2022). “I need you // But I can’t talk right now // I know you understand,” the poem “At the Drowned Valley” opens. As the press release offers: “This collection is about the eviscerating loss of a child, the hope that precedes this crisis, and the suffering that follows.” Crafted as a loose memoir through poetry and prose, the pieces in Path of Totality are emotionally raw and powerful, examining and writing through an impossible grief. There is something reminiscent here of other recent writings on grief and trauma, whether Anne Boyer’s memoir of living with breast cancer,

The Undying: Pain,Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care

(New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), Sarah Manguso’s memoir on her long-term illness,

The Two Kinds of Decay

(New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008) [see my review of such here], or even Joyelle McSweeney’s own writing on the loss of a child, through the dual poetry collection

Toxicon & Arachne

(New York NY: Nightboat, 2020). Pollari writes through the contradictions and confusions of grief, how it unsettles, clarifies and distorts, writing it simultaneously sideways and straight on. “I wanted to write a true poem.” she writes, to open “There Is No Word.” “I started with a fact: She had soft hair. I know because I / touched my chin to it when I held her. // The truth is that when I held her, neither of us cried.” The ending of the two-page piece offers:

American poet and translator Niina Pollari’s second full-length poetry title, following

Dead Horse

(Birds, LLC, 2015), is the devastating

Path of Totality

(Soft Skull Press, 2022). “I need you // But I can’t talk right now // I know you understand,” the poem “At the Drowned Valley” opens. As the press release offers: “This collection is about the eviscerating loss of a child, the hope that precedes this crisis, and the suffering that follows.” Crafted as a loose memoir through poetry and prose, the pieces in Path of Totality are emotionally raw and powerful, examining and writing through an impossible grief. There is something reminiscent here of other recent writings on grief and trauma, whether Anne Boyer’s memoir of living with breast cancer,

The Undying: Pain,Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care

(New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), Sarah Manguso’s memoir on her long-term illness,

The Two Kinds of Decay

(New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008) [see my review of such here], or even Joyelle McSweeney’s own writing on the loss of a child, through the dual poetry collection

Toxicon & Arachne

(New York NY: Nightboat, 2020). Pollari writes through the contradictions and confusions of grief, how it unsettles, clarifies and distorts, writing it simultaneously sideways and straight on. “I wanted to write a true poem.” she writes, to open “There Is No Word.” “I started with a fact: She had soft hair. I know because I / touched my chin to it when I held her. // The truth is that when I held her, neither of us cried.” The ending of the two-page piece offers: I walk through the body of every day like an organism be-

ing born. Through the red gel and muck of the underbelly.

Through all the female pain.

I say I walk but in truth there is no word for the locomotion

that I do.

The poems that make up Niina Pollari’s Path of Totality move through shock and sorrow, disbelief and grief, citing an anticipation that had suddenly, unbearably, gone dark. “All I have are facts and memories.” she writes, to open the prose poem “Facts and Memories.” “Facts are things that cannot be changed, and memories are impressions of a time when I did not yet know my own face contorted like this. // Facts are: Her weight and length. // Memories are: My loneliness. // After the fact, I invent a narrative. I see the story, its rising action, its fall. We all do this.” Throughout, Pollari works to plainly document her grieving as much as understand and work through it, moving through guilt, heartbreak, grace, silence and transformation. As the second section of the sequence “Animals” writes:

In human grief the cognitive response slows

As the human brain tries to understand the event

After an interruption to its sense of pattern

We always say I didn’t think things like this happened

The implication being to people like us even though death

is the only fact

But crows do not have a hard time acknowledging the fact

of death

Instead they move right into righteous anger

Becoming agitated upon seeing other crows dead

And never forgetting the circumstances

There is such an emotional upendedness to her narratives, writing plainly and clearly of a variety of tasks through and around such a devastating loss, simultaneously dream-like, allowing the writing to display the impossibility of belief and feeling throughout. As the extended lyric “Hungry Ghost” writes: “The funeral director, my husband, and me // I ordered a small caffeine-free tea // I needed to order something // To pretend we were there // For a normal reason // On this day in October // Just days after my daughter // Came out of me not breathing [.]” This is a remarkable collection, one that pulls the threads of self and sorrow and remains, somehow, coherent throughout, and manages, despite the weight of such a sorrow, to reach a kind of solace; or at the very least, the beginnings of a way to continue forward. Towards the end of the collection, the prose sequence “Sunflower,” she writes:

I realize now that you came from the eclipse. You were sucked back into it when it was over, when our time together came to an end. You were beautiful and world-ending. You shocked me with your beauty, and I became so scared.

A blind spot burned into my retina. A permanent hole, like film chewed up by heat.

Sunflowers are sunny. Why wouldn’t that be.

January 22, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Gillian Osborne

Gillian Osborne

is the author of

Green Green Green

, published in 2021 by Nightboat Books. Raised in upstate New York and trained as a poet and scholar at UC-Berkeley, she is currently Director of Curriculum at ASU’s Center for Public Humanities, and regularly teaches for the Harvard Extension School and Bard College. Her poetry, essays, and criticism have appeared in such publications as The Boston Review, LARB Quarterly Journal, Harpers, The New Republic, and The New Emily Dickinson Studies.

Gillian Osborne

is the author of

Green Green Green

, published in 2021 by Nightboat Books. Raised in upstate New York and trained as a poet and scholar at UC-Berkeley, she is currently Director of Curriculum at ASU’s Center for Public Humanities, and regularly teaches for the Harvard Extension School and Bard College. Her poetry, essays, and criticism have appeared in such publications as The Boston Review, LARB Quarterly Journal, Harpers, The New Republic, and The New Emily Dickinson Studies. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, this is my first book, so—to be seen! At the same time, this book draws on and grows out of a lot of past writing—poems, a dissertation, critical essays. The difference from that work is that this book more fully embodies the way I enjoy writing most, which is to combine creative and thoughtful energies, to pay attention to form on a line or sentence-level, but also to gain momentum and expand, associate, connect. Finishing the book has allowed me to experience my writing as for others in a new way, and myself as a writer as well as someone who writes.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’m attracted to how poetry wields peripheries. I love the empty, charged, space around and inside of poems, the way blanks gesture toward worlds beyond language, the way the slightness a poem comprises folds vaster outsides into it. For me, poems are the best expression of the interplay between texts and contexts, the way life feeds language and vice-versa.

That said, Green Green Green isn’t poetry! Even though it is a book I couldn’t have written without being a poet. I shared one of the chapters, “On Reading Natural History in the Winter,” in a draft phase with a shortly-lived writing group. The main feedback of one of the participants, who is a translator and a scholar, was that this wasn’t an essay; it was a poem! I’m not sure I agree, but I appreciated that comment.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m almost always writing, but much of that writing is exploratory: it’s about figuring out what I’m thinking about, what I’m working on, how to think and write, and what to pursue further. In that realm, I often get pulled in many directions, one after another. One week I’m interested in plants, the next in dirt, the next in vistas, then Anne Spencer, Francis Ponge, Robert Smithson, planets, that kind of thing.

I have another, very different, methodical, process for writing that responds to other texts. That process is: read, read, read; make massive amounts of notes; organize and expand; re-order; revise forever. There’s often some dancing back and forth between paper and screens. All the pieces in Green Green Green were heavily revised, and several of them, particularly the final essay, “Lichen Writing,” had very different forms before arriving in their current shape.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For a long time, poems would emerge on their own timing and often as a turn awayfrom something else that was more obligatory or rigorous in a defined way. Sometimes they’d emerge out of the exploratory process outlined above, but more often, they’d come from something else—a conversation or encounter—and initiate a new trajectory of investigation.

I’ve also had the experience of writing a lot of poems all at once in response to a particular life event that was especially devastating, or expansive—following a death, for example, or when my child first began using language. Those poems are ones I have trouble shaking, or drastically revising; for me, they maintain something of their original urgency, which maybe makes them harder to see objectively, and definitely makes them difficult to integrate into a larger “project.”

Since this winter, I’ve been practicing a very constrained kind of daily poetic writing—10 lines first thing in the morning over the course of an hour. This was something I started doing through a mentorship with Caroline Bergvall. Only some of the pieces are things I’ve come back to and worked on. But I’ve really loved the ritual of that process; it’s allowed me to eddy around language and ideas in a new way.

I’ve had ideas for projects or books, but often they aren’t the ideas that have the momentum to keep me writing. I want the process of writing to be one of genuine discovery and pleasure, so there has to be some element of the unknown, something I’m writing toward. Almost all of the pieces in Green Green Green began in that way, as separate inquiries; it was only later that they began to speak to each other.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Yes! I really enjoy the sound and feeling of words spoken deliberately, entering air, mingling. It’s one of the things I like about teaching, too, that statement and restatement and circling around a text, voicing and re-voicing of it. I’m not a very dramatic reader; in fact, I really like the juxtaposition between staid reader and lively written voice. But I’m also deeply attracted to performative poems by others, particularly those that are really stripped down, like Caroline Bergvall’s “Via” or M. Nourbese Philip’s Zong! poems. Both of those pieces are ones that need to be read aloud, I think; or at least need to be heard in order to really resonate. There’s a this-is-happening-in-real-time quality that intensifies the work and can’t be grasped purely visually. The earliest research I ever did was on Dickinson and performance—on her readings of Shakespeare and all the lengths she goes to suspend a moment of cessation in her poems, to keep the play going even after the player may or may not be dead. More recently, I’ve been drawn toward language that incorporates elements of ritual or prayer; chants, spirituals, old Shaker songs. All to say: I’m really interested in the ways in which words are animated, and I like to make that visible in my work in a variety of ways, including through readings!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

This question feels a little dangerous for me. Definitely lively. In short: yes! I trained as a scholar of literature, but also always wanted to be a poet; so theoretical questions about what poetry is, the work it does in the world—what magic is—are very active for me. I’m also drawn to contexts, texts, writers who are deeply besotted with, or concerned for, the natural world in some way—its current crises, but also its longer histories, and its bare, enduring, impersonal, materials.

As a scholar, I find it difficult to translate the questions that feel most compelling to me to a strictly academic audience. As a creative writer, it feels more open. For example, in Green Green Green, the theoretical concerns are quite meta: what is reading? How does it happen in time and place? How does the time of reading correspond to other time-scales? Why is repetition so affecting, even when it’s so seemingly linguistically basic? I’ve been thinking about this question again recently as I revisit 19th-century transcriptions of indigenous American chants and songs; I find those feats of language profoundly moving, not least of all for their insistence that language is an activation, causing something to happen in the world.

In terms of what the current questions are, I think there are a lot of them, and that writers should take up the ones that feel most pressing to them. Political questions and solutions often feel a lot clearer to me than the kinds of questions that invite me into writing. Questions like: how do we build a more habitable, just, planetary community are essential and also questions I don’t feel I can answer in a poem. Should we tax the rich? Yes! Should we redistribute funds to more equitably fund public schools? Yes! Those are some questions I already know the answers to. In my writing practice, I need there to be an element of the unknown; that’s what keeps language feeling alive for me.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers serve so many roles within culture—to invite others into thinking, to entertain, educate, to energize, activate, enrage, and provide solace. The one thing I think they all have in common, though, is the demonstration that language matters, and the renewal of that mattering. Writers write so that we can read or listen and have both experiences of companionable solitude and community facilitated by language.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I really like working with editors. The writer-editor relationship at its best can be generative and collaborative. Editors can also be invitation-givers, the same way that a teacher can craft questions in response to a student’s work that might lead to new ideas. I enjoy the process of writing something forsomeone else, or in response to a particular request. If anything, I’d like to write more often in conversation with editors. Editors, call me!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I remember hearing from another friend about a colleague of hers in creative writing that had written a book he thought “did everything” he knew how to do. I don’t know if that counts as “advice,” but the idea of the book that brings together one’s different faculties really stuck with me and was on my mind when I was putting together Green Green Green.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Early on in graduate school, the poet Jessica Fisher told me I should drop whatever else I was working on whenever I felt the urge to write a poem. That’s a more straightforward piece of advice, and one I took! For years, I was always pivoting in this way, back and forth, from reading to writing, arguing to imaging.

In a certain way, though, I think this turning from one to another created false boundaries between the two modes of writing, and made me feel like neither practice was whole. More than anything else I’ve ever written, Green Green Green draws together my training as a poet, essayist, scholar, and educator.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

See answer to #4! Just since this winter, I wake up most mornings around 5am and work on poems. Usually I write something new; occasionally I go back to something ongoing. For longer pieces of writing—like all the essays in this book—I need to carve out longer chunks of concentrated time to focus, which is increasingly hard for me to find. Some of these pieces were drafted when I had a fellowship; back then, I could spend the whole day reading and writing, so that was the routine, punctuated by breast-feeding, lectures, and meetings. These days, writing is more compressed, but even more precious and devotional because of that.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading! I’m a passionate and active reader. I’m generally reading multiple things at once. And these days, because my work isn’t bound by a particular historical or theoretical field, I can follow my reading inclinations, swerves, and enthusiasms. This past winter, for example, I read most of Inger Christensen’s work for the first time—poetry and prose. Earlier in the year, I read a lot of Alice Oswald’s and all of Lucille Clifton’s poems. Some of the poems I’ve been writing in the morning begin as direct responses to lines or phrases from another text. I often have ideas for essays—hardly ever poems—while walking.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I love this question. These days, it’s the smell of sage in California chaparral. The juniper and cedar that grows at my grandmother’s house in Massachusetts are another kind of home-smell. And the dear reek of the marsh mud there, too. In general, wet dirt smells homely to me.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Definitely the natural world! Also, history, and the way it gets written onto landscapes in particular. At one point, I thought Green Green Green might be a “bioregional biography” of a 50-mile square area in central Massachusetts at the middle of the 19th century. I spent some time walking around in that part of the world, looking at some of the wildflowers Dickinson or Frederick Goddard Tuckerman might have seen in their environs, looking at the low hills around Amherst.

Plants figure strongly in my work, and those fascinations arise from actual encounters. Now that I actually have a garden (I didn’t when I wrote most of the essays in Green Green Green), I feel increasingly drawn toward what’s going on under it, toward soil and stone more broadly. For the past few years, I’ve also been thinking and writing a lot about hills: these brief vantage points from which one could have some kind of experience of transcendence, if properly primed for that sort of thing, but that otherwise are quite approachable and mundane; local wildernesses that could go either direction—toward the sublime or the quotidian—depending on what you bring to them. I grew up in this little, hilly, village in upstate New York, with a river (the Hudson), and a cemetery and orchard at the top, with a view across a border to Vermont; that geography is deeply imprinted in my psyche. And I’ve lived beside a number of hills in California, Bernal Heights in San Francisco, and this small hill outside my window in Santa Barbara. I also had a number of very formative experiences of being—and getting lost in—mountains that continue to haunt me.

I like dance and performance art a lot, too—aesthetics in motion, which create an experience; I think of poems in those terms, also.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dickinson and Melville were the writers that brought me to grad school, and the reason I focused on American literature there. But prior to getting deeply into the weeds (and wildings) with them, I had a more cosmopolitan engagement with literature and art. (Ha!) I love the urban music of Apollinaire and the every-day documentary impulses of Ponge. Basho was a big part of why I lived in Japan, this idea that one could pilgrimage to a place where poetry had happened and recreate that experience. Jamaica Kincaid’s My Garden Book is one of my favorite works of prose ever; I find the balance of indirection, suggestion, and forthright declaration in her writing thrilling. I also really love books that demonstrate other ways of living with books that aren’t literary criticism; there are some passages of dizzingly-close reading in Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond that are like that. Helen McDonald’s H is for Hawk and Robert Glück’s Marjory Kempe are other examples of this that I’ve really enjoyed.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Publish a book of poems! Editors—see response to #8 above!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In terms of jobs, these days, I devote a lot more time to the work of being an educator than to my own writing work. When I was much younger, I thought I would like to be a farmer and a poet, but not like Wendell Berry, weirder. My first job was working for a farmer who had a PhD in comparative literature and used to tease me about how I should write poems for the vegetables. And later, I worked for some nurseries and “landscapers” in New York (“landscaping” living rooms and roofs). I really like working with plants, but I wouldn’t rather do that than writing or teaching. In any job I’ve ever had, reading, writing, thinking has always felt like the real work—the thing that's at the core.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I love words. More than other things!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Inger Christensen’s alphabet. I don’t know if it’s a “great” film, but I really enjoyed and keep thinking about My Octopus Teacher. That film made interspecies love feel way more real to me than anything I’ve ever read about encounters between humans and animals, or any of those encounters I’ve had myself.

20 - What are you currently working on?

1-3 collections of poems: see notes on hills, wildernesses, and rituals, above. A sequence about mushrooms, worms, and reproductive energies in the dirt. Something that may be a novel on mountains, desire, and obscurity. Ways to make writing a more embodied practice, generally. Watching this house finch and a hummingbird have a face-off out the window. An ecologically sustainable ornamental garden. Learning the names of the southern hemisphere trees in my town. A lesson plan. Dinner.

January 21, 2022

Sylvia Legris, Garden Physic

Equisetum hyemale (Rough Horsetail)

after a photograph by Karl Blossfeldt

Let the fossil records show:

Green of two winters;

Small scale fluctuations;

Multi-tempoed scouring-rush;

Rough scrub-music horsetail;

Amplified 40-fold brusque bray;

Silica-encrusted corrugations;

A living fossil cross-section;

Reedy wetland habitat;

Pewterwort the sonorous tin-herb;

Cone an E-flat apiculate pitch.

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris' latest, following

Circuitry of Veins

(Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 1996),

Iridium Seeds

(Turnstone Press, 1998), the Griffin Poetry Prize-winning

Nerve Squall

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2005),

Pneumatic Antiphonal

(New York NY: New Directions, 2013) and

The Hideous Hidden

(New Directions, 2016), is

Garden Physic

(New Directions, 2021), her second full-length collection (and third title) to appear with American publisher New Directions. Structured in four sections—“The Yard Wants What the Yard Wants,” “Where Horsetail Intersects String,” “Floral Correspondences” and “De materia Medicia”—Garden Physic is very much a space through which she examines both botanical and the lyric through the lens of language, offering the perspective of “the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force” (Wikipedia) on a space considered simultaneously wild, natural and domestic: the garden. The garden as a space for poets is one well-trod (perhaps through both forms, gardening and poetry, seen as meditative), with recent examples including Ottawa poet Monty Reid’s twelve-month cycle,

The Garden

(Ottawa ON: Chaudiere Books, 2014), Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster’s examination of formal gardens in

A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth

(London ON: Brick Books, 2011) [see my review of such here], New England poet and translator Cole Swensen’s exploration on the seventeenth-century French baroque gardens designed by André Le Nôtre in Ours (University of California Press, 2008) [see my review of such here] and California poet Hazel White’s exploration of the works of landscape architect Isabelle Greene and her iconic Valentine garden in

Vigilance Is No Orchard

(New York NY: Nightboat, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the latter three titles wrote directly around the Victorian ethos of the shaped wild of crafted gardens, Reid’s collection might be a more apt connector, given Legris’ attentiveness to the shape and movement of growth and seasons, articulating the language of horticulture. As the second half of Legris’ poem “Ferns and Fern Allies” offers:

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris' latest, following

Circuitry of Veins

(Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 1996),

Iridium Seeds

(Turnstone Press, 1998), the Griffin Poetry Prize-winning

Nerve Squall

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2005),

Pneumatic Antiphonal

(New York NY: New Directions, 2013) and

The Hideous Hidden

(New Directions, 2016), is

Garden Physic

(New Directions, 2021), her second full-length collection (and third title) to appear with American publisher New Directions. Structured in four sections—“The Yard Wants What the Yard Wants,” “Where Horsetail Intersects String,” “Floral Correspondences” and “De materia Medicia”—Garden Physic is very much a space through which she examines both botanical and the lyric through the lens of language, offering the perspective of “the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force” (Wikipedia) on a space considered simultaneously wild, natural and domestic: the garden. The garden as a space for poets is one well-trod (perhaps through both forms, gardening and poetry, seen as meditative), with recent examples including Ottawa poet Monty Reid’s twelve-month cycle,

The Garden

(Ottawa ON: Chaudiere Books, 2014), Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster’s examination of formal gardens in

A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth

(London ON: Brick Books, 2011) [see my review of such here], New England poet and translator Cole Swensen’s exploration on the seventeenth-century French baroque gardens designed by André Le Nôtre in Ours (University of California Press, 2008) [see my review of such here] and California poet Hazel White’s exploration of the works of landscape architect Isabelle Greene and her iconic Valentine garden in

Vigilance Is No Orchard

(New York NY: Nightboat, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the latter three titles wrote directly around the Victorian ethos of the shaped wild of crafted gardens, Reid’s collection might be a more apt connector, given Legris’ attentiveness to the shape and movement of growth and seasons, articulating the language of horticulture. As the second half of Legris’ poem “Ferns and Fern Allies” offers: Bladder-fern. Adder’s-tongue.

Where horsetail intersects string.

Where tone color is quillwort.

Spiny-spored or large-spored?

Bristle-tips or conspicuous tufts?

Upper bout an upswept moonwort.

Lower bout a smooth woodsia.

Diminutive growing in low fronds.

Rhizomes erect to ascending in perfect fifths.

The cover-copy to the collection offers a comparison to Louis Zukofsky’s 80 Flowers(Stinehour Press, 1978), and her work is long-known for its foundational influence by another of the Objectivists, Muriel Rukeyser, but I would offer, also, that Garden Physic seems akin to a lyric exploration in the veins of the botanical books that Emily Dickinson used to put together for friends and family. These are poems that approach the minutae of flora and fauna, both through the plant itself and its descriptions through language, nearly set on the page as research notes, marking and remarking on movement, growth and the unfurling of speech. If Lorine Niedecker’s “Lake Superior” emerged out of the poet absorbing a study of nature and carving out her thinking directly to the page, so, too, as Sylvia Legris writing her Garden Physic. As her short poem “Violet” reads:

A garland to rend off the dizzies.

A garland to keep the quinsy at bay.

March closes the seeded umbilicus.

April opens the musty secundina.

Equinox the half-melt rot.

Easter the thin asquintable light.

“The yard wants what the yard wants.” she writes, as part of “The Garden Body: A Florilegium.” Garden Physic is a detailed study of wildflowers and herbs composed through the lyric, citing a multitude of possibilities, and her language is densely-specific. Legris explores the Latin names and intimacies of plants, and there is something comparable to Toronto poet Kate Siklosi’s recent leavings (Timglaset Editions, 2021) [see my review of such here] in a shared approach to plant life on its own terms, from the opening poem of Legris’ collection, “Plants Reduced to the Idea of Plants,” that begins: “The flourish, the fanfare, the febrifugic feverfew. // An oleaginous emplastrum—with horehound leaf, / olive over olive, the oily parts, the dry. // An antidote for the unblessed, the blistering, / the dourly flowering flora, the corpse flora. // Greek turned Latin turned inordinately / angled and filed.” There really isn’t anyone else working this kind of study, blending scientific language through a language-centred lyric. One could cite St. Catharines, Ontario poet Adam Dickinson, for example, who works a more straightforward metaphor-driven lyric, and Toronto writer Christopher Dewdney, who was at the forefront of this kind of writing throughout the 1970s and 80s, hasn’t produced a new volume of poetry since Demon Pond (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1994). Her third section, “Floral Correspondences,” composes, as she writes, “an entirely invented exchange” between English author and garden designer, Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) and her husband, the British politician and writer Sir Harold George Nicolson (1886-1968). They are know for, among other things, co-designing “the celebrated garden at Sissinghurst,” and Legris’ explores a floral call-and-response that bounces through a language of gardens, including the poem “Oh Darling,” that reads:

Midges and techiness.

A constantly muddy mood.

In my impatience for mail it strikes me that the perianth is a floral

envelope—a cloak concealing the reproductive organs …

Alas, I forbear. A capacity for waiting defines both the gardener and the

letter-writer (the growing season longer than my endurance). I throw

myself into work and diversion but progress so slowly I fear there will be

frost by the time this reaches you. snow on your salpiglossis.

– H.

January 20, 2022

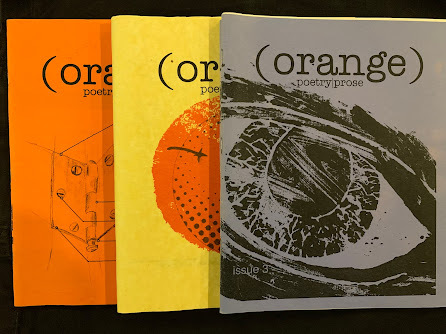

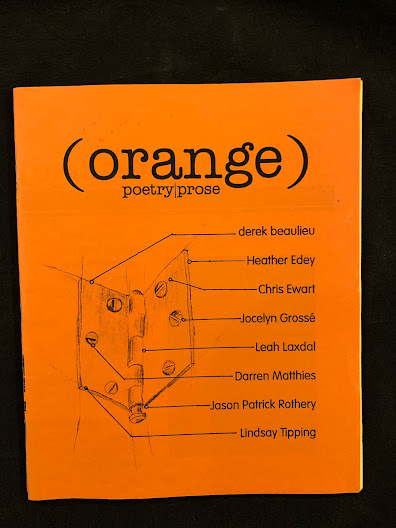

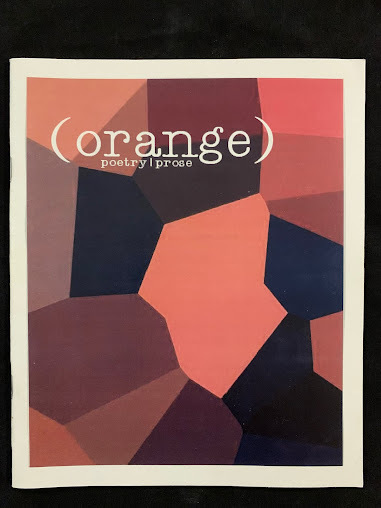

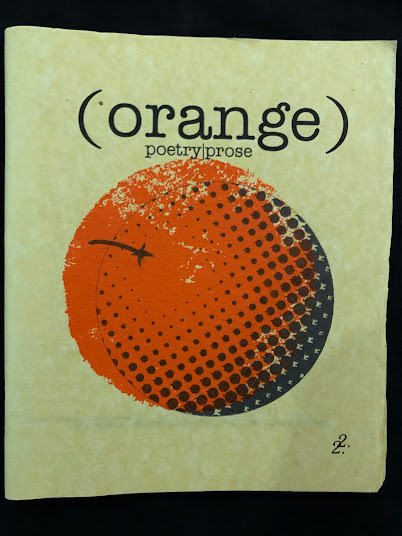

(orange) (2000-2002): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email from June 2021 to January 2022 as part of a project to document literary publishing. see my list of interviews and bibliographies of literary publications past and present here

Nikki Reimer is a poet, artist, and non-fiction writer living in Southern Alberta. Published books are My Heart is a Rose Manhattan, DOWNVERSE and [sic]. Work has appeared on stages, billboards, public art exhibits, pop-up bistro menus, and in various magazines, journals and anthologies. Visit reimerwrites.com.

Nikki Reimer is a poet, artist, and non-fiction writer living in Southern Alberta. Published books are My Heart is a Rose Manhattan, DOWNVERSE and [sic]. Work has appeared on stages, billboards, public art exhibits, pop-up bistro menus, and in various magazines, journals and anthologies. Visit reimerwrites.com. ryan fitzpatrick is the author of three books and over fifteen chapbooks of poetry, including Coast Mountain Foot (Talonbooks 2021) and Fortified Castles (Talonbooks 2014). Over the last twenty years, he has been involved in the poetry communities of Calgary, Vancouver, and Toronto. Currently, he is the editor of Model Press, an online poetry micropress founded during the pandemic. You can find him at ryanfitzpatrick.ca.

Chris Patrick Carolan is an author, editor, and hovercraft enthusiast, originally from Glasgow but currently based in Calgary, Alberta. He writes science fiction, fantasy (urban and epic), and steampunk, though he has also been known to turn to crime to make ends meet. Crime fiction, that is. THE NIGHTSHADE CABAL was published by Parliament House Press in 2020 and was a finalist for the Crime Writers of Canada Awards of Excellence 'Best First Novel' award. He can be found on Twitter as @cpcwrites but consider this fair warning… it’s mostly wisecracks about McNuggets and Simpsons memes.

Q: How did (orange) first start?

Q: How did (orange) first start? NR: It started when the UCalgary English department convened a meeting to see if anyone was interested in reviving Grove, the previous department undergraduate literary publication. The faculty advisor Frances Batycki may have been in attendance. A bunch of us said we were keen, and off we went. I think ryan and I took the leads because we were the keenest, but ryan’s memory may be sharper than mine.

rf: Yeah, I think that's right. Grove was the most recent in what was a chain of undergrad literary journals in the department. There was another one before Grove called Sanskrit. Frances Batycki called a meeting that was held in the English department lounge in Fall '99 maybe. Was it called because there was some leftover money from Grove? It was attended by quite a few people, but it ended up being Nikki, me, and Michael Thome who were the most interested. Michael was more vocally interested in being involved than I was. For me, at least, joining the undergrad journal felt more possible than joining something like filling Station, which might as well have been on the moon even though it was being run by people who were only a few years older than us and also didn't know what they were doing.

Q: I don’t know anything about Grove. What was Grove? And where did the title (orange) come from? It had always been my impression that it had been lifted from that prior Calgary journal, Secrets from the Orange Couch, yes?

NR: I must have a copy of Grove -- it was my very first publication credit -- at home; I will look and report back. I believe Micheline Maylor may have been an editor? And nope, we -- at least, I -- had no knowledge of Secrets from the Orange Couch when we began. I think we were riffing off “grove” and ended with “orange”... as in grove. A wee bit cheesy.

rf: Well, I might’ve known about Secrets from the Orange Couch, though I think I stumbled across it in MacKimmie Library right after we named the magazine. We named the magazine (orange) as a play on Grovefor sure. I vaguely remember conversations about not wanting what we were putting together to be like Grove, which was maybe not experimental enough for our tastes, but we still wanted to nod to the continuity. It also reminded me of the joke that nothing rhymes with orange. I do remember finding Secrets from the Orange Couch and thinking that we had somehow chosen the perfect name, since both Nikki and I were in Nicole Markotic’s intro poetry workshop and Nicole was one of the editors of Secrets.

NR: I just found my Grove, and the editor’s note from Micheline does mention a previous journal called Sanscrit. Someone should make a lineage of journals associated with the UCalgary English department.

rf: For sure, Sanscrit then Grove then us then Nōd.

Q: Honestly, it is blowing my mind a bit that (orange) wasn’t deliberately a furthering of Secrets from the Orange Couch (as I’d been presuming for years now). In hindsight, how do you see (orange) in relation to those other journals, both prior and what came after?

Q: Honestly, it is blowing my mind a bit that (orange) wasn’t deliberately a furthering of Secrets from the Orange Couch (as I’d been presuming for years now). In hindsight, how do you see (orange) in relation to those other journals, both prior and what came after? NR: I don’t know if I can give a satisfactory answer to this question, rob. I’ll admit that I haven’t studied what came before or after thoroughly enough to make any claims. ryan is the more intellectual of the two of us, and may have more to say. I did feel some jealousy at how professional Nōd appeared to be. I remember trying to figure out how to get sponsorships and ads so that we could become a grown-up magazine; I could have used a mentor.

rf: Hmm. I think that if we were picking up on the earlier vibes of Secrets from the Orange Couch (or Absinthe, or even filling Station), it had something to do with what Nicole and Fred were putting into the air as our teachers even though they weren’t pumping up their own small press histories. It’s not like Fred was bringing copies of Tish or Screeinto class or anything. Instead, he and Nicole would nudge folks into producing things and then those folks would nudge other folks and so on. I remember someone (maybe tom muir) telling me that filling Station started because Fred put the idea into the head of a few students and they ran with it. As for Nōd, I remember feeling some annoyance at how professional they seemed to be, maybe because I felt (and still feel) that poetry should be a little unprofessional. I like that (orange) was kind of unpolished. After (orange), the scene seemed to get more professional across the board. Not just Nōd, but Dandelion became a bigger fixture in the community and filling Station was getting squeezed by funding bodies to professionalize.

Q: How was the argument for the journal formed? Was it seeking to be a repository for the kinds of work that was being produced around Calgary during that time? Were you seeking a particular aesthetic or poetic?

NR: It wasn’t intended to be Calgary-centric. I think we had some inklings of wanting to publish work that pushed back against what was at the time a more dominant lyric movement, but we also really had no idea what we were doing. I do admit some jealousy towards journals like PRISM that are more embedded within the institutions they are part of, and where folks start as volunteers, and gradually learn how to run a magazine. We were just a bunch of scrappy kids photocopying our little magazine at Staples and trying to figure out what we thought was good. On the other hand, that’s pretty punk rock of us, which was very much in line with the Calgary I remember from that time.

Q: I think the “scrappy kids” aspect is what gave the journal character. How was work gathered for that debut issue? Were people solicited or was a call put out?

Q: I think the “scrappy kids” aspect is what gave the journal character. How was work gathered for that debut issue? Were people solicited or was a call put out? rf: Did we put out a call? I just remember asking people. Half the writers in the first issue are just people who were in our class.

NR: Gosh, I don’t think we put out a call for the first issue, no, we must have asked folks we knew. I do remember a later call for submissions poster ryan made with the line “submission is necessary”. Our vibe was pretty cheeky.

rf: I probably have a copy of that poster somewhere.

Q: Do you remember the response to those first few issues? And how were issues distributed? You say you didn’t want the journal to be Calgary-centric, but how did you get the word out, especially to anyone beyond the city’s borders?

rf: I always thought we were very local. This is probably a better question for Nikki.

NR: I thought we were too, though when I flipped through the issues for this discussion I saw quite a few contributors from other parts of the place we call Canada. But some of those people were friends, or friends of friends. We may have tried to get a call for submissions put onto some of the literary listservs that were active at the time. I think either Natalie Simpson or Jill Hartman wrote to a number of “big name” writers who were kind enough to submit as a favour to us -- Erin Moure, Nicole Brossard.

I seem to remember walking around to the used bookstores in town and trying to get them to carry us. The UCalgary Bookstore stocked us. I wrote a brash press release that got our inaugural launch party onto A Channel. Our activities made it into FFWD magazine a few times, which had been one of my goals for us. Otherwise, yeah, we mostly spoke and responded to what was happening locally around us.

CPC: I remember a lot of hand-selling copies to anyone who came to our events. I always preferred to lurk in the background at the readings, so I spent a lot of time at the table trying to get people to buy the latest issue. It felt like a very DIY punk rock way to get literature into people’s hands! I don’t know what percentage of our circulation came from selling at those readings and launch parties, and I don’t think we ever sold out a print run, but it was certainly fun.

Q: What else was happening during that time? Who else was around?

Q: What else was happening during that time? Who else was around? NR: filling Station was around and established at that time, and the Single Onion reading series. derek beaulieu was running house press. Jill Hartman, Ian Samuels, Tom Muir, and Natalie Simpson were all local writers I looked up to. Rajinderpal S. Pal and Richard Harrison were older, established writers and good folks who were mentors to me in the art of literary event organizing and hosting. We were all involved in the UCalgary writing classes, so literary events the department hosted were a part of the milieu, and our writing instructors Fred Wah and Nicole Markotic. I seem to recall a joint event with Single Onion at a warehouse in Bridgeland? ryan, what am I forgetting?

rf: Are you talking about that one reading at that place right on Memorial? The Emerald Cafe? I vaguely remember something like that. Couldn’t tell you anything else about it. Anyway, it felt like there was a lot going on, some of which in retrospect was pretty short lived. filling Station was around, but I was only vaguely aware of it when we started. Nicole gave us all an issue of it in class one day, I think. Dandelion was just about to be folded into the English department at that point, but wasn’t really a presence around town until after that. I found the microstuff more compelling. Jill and Natalie were in a writing group called the Phu Collective with Lindsay Tipping, Darren Matthies, Trevor Speller, and Tillie Sanchez (and Julia Williams, who seemed like a non-member of the group). I remember being really impressed by them because they had gotten an article in ffwd. And they had chapbooks in the University bookstore! Really, they were all just folks who were a year or two ahead of us in the English department. Single Onion had just recently started and maybe Ian Samuels was involved in it at that point, but it was pretty focused on lyric work and spoken word centered on a crew of Sheri-D Wilson, Kirk Miles, Fred Hollis, and some other folk. Some folks from our circles moved in and out of Single Onion a little later--I remember getting to read for them at different points because André Rodrigues and Jocelyn Grosse were on their collective. I think tom and derek were starting EndNote with russ rickey at that point, maybe? There was House Press of course, but there was a ton of other chapbook publishing going on too. I remember a class reading at the Beat Niq jazz bar in the basement of the Grain Exchange and the piano on the stage was covered in chapbooks that people had made. That was mind-blowing to me.

NR: No, it was called the Daniel Sponagle Centre for Contemporary Art & Mischief; the space i Bridgeland. That was closer to when we folded; maybe you were in Korea at that point ryan? I agree with you about the energy and excitement around the microstuff that was happening. Nicole Markotic had Jill Hartman come to our poetry class to show off the tiny perfect chapbooks she was making, and it blew my mind that it was possible to create in that way. EndNote was so great!

rf: Okay, the Sponagle place rings a bell, but maybe only from an email or something.

Q: From the outside, at least, this really did seem like an explosive period in Calgary poetics, with a huge array of writing and publishing and just general literary (and small press) activity. How did it seem from the inside? What did Calgary have at that time that other centres didn’t?