Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 121

July 5, 2022

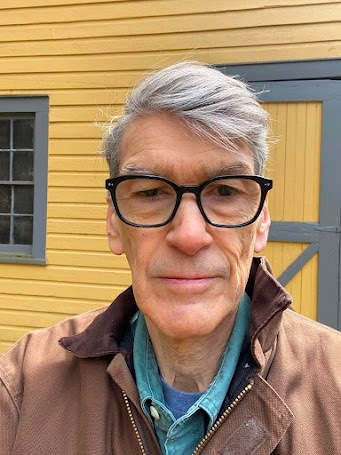

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Douglas Crase

Douglas Crase

is a poet and former MacArthur fellow who made his living as a speechwriter. His first book, The Revisionist, was named a Notable Book of the Year 1981 in The New York Times and nominated for the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. His collected poems,

The Revisionist and the Astropastorals

, was a Book of the Year 2019 in the Times Literary Supplement and Hyperallergic. His collected essays,

On Autumn Lake

, was noted for its “rare intimacy” and awarded a starred review by Kirkus in 2022. Crase lives with his husband in New York and Carley Brook, Pennsylvania.

Douglas Crase

is a poet and former MacArthur fellow who made his living as a speechwriter. His first book, The Revisionist, was named a Notable Book of the Year 1981 in The New York Times and nominated for the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. His collected poems,

The Revisionist and the Astropastorals

, was a Book of the Year 2019 in the Times Literary Supplement and Hyperallergic. His collected essays,

On Autumn Lake

, was noted for its “rare intimacy” and awarded a starred review by Kirkus in 2022. Crase lives with his husband in New York and Carley Brook, Pennsylvania. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The interval between the writing and the publication was so lengthy the emotional change had already occurred. One thing you learn from a first book, however, is that it matters to people you never envisioned and doesn’t matter to those you secretly hoped to persuade. This can be interesting. It changes the way you think about fellowship, which is bound to make a difference in your work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry came to me, twice. The first, before I was old enough to read, was when my grandmother read to me “The Song of Hiawatha.” The magic of it transformed her voice and it seemed she herself was Nokomis, daughter of the moon, the grandmother of the poem. The second was when my great aunt gave me a copy of Leaves of Grass. By then I was eleven. I'd written a would-be novel about a boy and his horse, so my aunt probably thought I needed an example of authentic literature. The magic this time transformed the farm where I was growing up, made it an arm of the cosmos, a proxy for Whitman’s cosmic democracy. Fiction couldn’t compete with that kind of power.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

If it’s a poem you don’t know when it started; you only know when it comes to the surface. But if it’s an essay it takes forever because you do know when it started. I am not a believer in first drafts. If there aren’t fifteen or twenty drafts the thing hasn’t been written.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Again it depends. If your question is about poems, they begin as inchoate problems. Sometimes, after they’ve been hanging around as a kind of hum, they introduce themselves by title. But in the case of “pieces” the problem is present at the outset, like an assignment, so the solution ends up most likely as prose. My ideal would be to combine the two in a single, unimpeded way of life.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They are apples and oranges. The audience when you write and the audience when you read are on different planets. You desire them both.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wish writers could position the new cosmology, post Hubble, Heisenberg, and Higgs, in a language that makes it inescapably natural. It should render the fear merchants ludicrous, as we know they are.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Well, this sounds like a tautology but the role of the writer is to write. Everything else is application and puts off the muse.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

When I wrote speeches for a living I got accustomed to the many edits you might need to satisfy a client. You couldn’t afford to resent them. Plus, they focus you on the destination of your words. So I learned to edit myself ahead of time. But the outside editing of an essay is rare in my experience, and of poems it just doesn’t happen.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The most memorable advice came from John Ashbery, when I had complained of being nervous about doing something. “I always find you’re saved by your own charm,” he said gently. Imagine the power of that, if you could put it in practice. It certainly worked for him.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

Too easy, and as I said earlier my ideal would be to make them the same. Freedom and accuracy at the same time.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Though I’d love to be among the writers who work at a certain time of day, for their whole lives, this would be a luxury that doesn’t always fit your responsibilities. For poetry, the best would be to procrastinate all day and start writing at four in the afternoon, trusting someone else to have dinner waiting at ten, or whenever I chose to reappear. For an essay I’d want to start after ten and write until five or six a.m. Life, obviously, is apt to intervene.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to go to a place, even if it’s just outside, and look at it. Emerson said we are never tired as long as we can see far enough. Oatmeal cookies help too.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Silage, manure, freshly mown alfalfa; or all at once.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

McFaddenwas right. Of course the other four—nature, music, science, and art—are all motivational too. What’s left? I guess I’d add love and the strange goads that come with it: anger, humiliation, guilt, desire, and care. They may not seem like forms but they are.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

When I began to write speeches for a living I met an older speechwriter, Joe Brickley, who had a lasting impact. It’s past time to acknowledge him. From Joe one learned to be amused by the tricks a writer employs, the play-by-play that gets you from beginning to end. In particular he taught me to recognize as egotism the kind of writing that itemizes every alternative. He called it the “on-the-other-hand-he-wore-a-glove” school of writing, where you balance everything and say nothing. That liberated my poetry as much as prose.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Become proficient with a chainsaw. There are a lot of trees here and the dead ones fall across the paths and get in the way.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

One of those aptitude tests they gave in high school, the Kuder Preference Test, said I should have a career in agriculture.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In law school I hated the drudgery. I took a couple outside writing jobs and discovered in their case I almost liked the drudgery. If I was writing a poem you could even say the drudgery kept me in thrall. So it took too long, but eventually I dropped out of law school and looked for a way to write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read recently a terrific first book, Irredenta, by the poet Oscar Oswald. His project, apparently, was to re-purpose the pastoral poem for a decolonized, climate-threatened, politically uncertain North America; and he succeeds in ways I couldn’t have imagined. So I looked again at the great original, the Idyllsof Theocritus, which I honestly didn’t remember very well. It turns out, if we ever thought pastoral was precious and irrelevant, we couldn’t be more wrong. As Oswald says in an essay for Lit Hub, there is no pastoral without threat of evil, doubt in our beliefs, or “rebuke of their slack power in the face of calamity.” From Theocritus it’s an inevitable step to the Ecloguesof Virgil, Leaves of Grass, and Irredenta. They amount to an epic more durable even than film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

The answer to that is always the same: It’s too early to tell.

July 4, 2022

Julie Doxsee, The Fastening

UNPACK

When the house decayed, I drove

around for days, messy swerves

in the foothills. I stared

at my foot on the brake,

swallowed by machine-tomb. I couldn’t

get out and lie on the grass—it was grave and grey with snowman

slush. I couldn’t swim under the snow-floor

feeling the prophecy creep. Prophecy,

I can’t love you. prophecy,

the future is rattling.

The fifth full-length poetry title (and first I’ve seen) by Pennsylvania-based Canadian-American poet Julie Doxsee is

The Fastening

(Boston MA: Black Ocean, 2022), a collection of sonic twists and gyrations, turns and parrys less surreal than jarring. “It isn’t that there’s no / honesty out there.” she writes, to open the poem “BANG EMOJI,” “It’s just / that storylines have always / discreeted themselves / into tree hollows, followers, / phoneys, mannequin-ruins.” Her work has the curious echo of the work of another Black Ocean author, Zachary Schomburg [see my review of his latest], offering a similar tone through examinations along prose and narrative disjuncture, although one with more interest in the possibility of the line-break. One could compare her work, also, to that of Canadian poet Stuart Ross, although his more an overtly-surreal bent; Doxsee’s poems, instead, offer something a perspective that, at first, is grounded, but then leans into a tilt. “There is a whole lot / of windy noise when / a sudden face comes / to kiss me in the recess.” she writes, as part of “10,000 GLINTS,” “A witness saw / this pair of hands / part my lips / from outside-in / and freeze there, / awaiting exhale / and the boundary / of my cold body.”

The fifth full-length poetry title (and first I’ve seen) by Pennsylvania-based Canadian-American poet Julie Doxsee is

The Fastening

(Boston MA: Black Ocean, 2022), a collection of sonic twists and gyrations, turns and parrys less surreal than jarring. “It isn’t that there’s no / honesty out there.” she writes, to open the poem “BANG EMOJI,” “It’s just / that storylines have always / discreeted themselves / into tree hollows, followers, / phoneys, mannequin-ruins.” Her work has the curious echo of the work of another Black Ocean author, Zachary Schomburg [see my review of his latest], offering a similar tone through examinations along prose and narrative disjuncture, although one with more interest in the possibility of the line-break. One could compare her work, also, to that of Canadian poet Stuart Ross, although his more an overtly-surreal bent; Doxsee’s poems, instead, offer something a perspective that, at first, is grounded, but then leans into a tilt. “There is a whole lot / of windy noise when / a sudden face comes / to kiss me in the recess.” she writes, as part of “10,000 GLINTS,” “A witness saw / this pair of hands / part my lips / from outside-in / and freeze there, / awaiting exhale / and the boundary / of my cold body.” Down the length of each page in accumulated short lines, Doxsee composes odd scenes and surreal stabs, tentacles and maps, writing out connections and disconnections, and almost a confusion between what we might think of either. She writes of childhood, death, love and other dark corners, as though composing a book of origins: seeking out, through the storm, the mouth of the river. “I enjoy phases of time / like that.” she writes, to open the poem “BANGKOK,” “I once enjoyed / a goat hoof in the heart, / kicking hard. Still, I have / skin-aches boring out and out / and out to the smothering / bricks. Am I taller than you?” There is a remarkable calm and even reassuring to Doxsee’s poems, amid such possible chaos. Perhaps it is simply the measure through which her lyrics speak. There is something of the monologue to her poems, after all, something theatrical, even performed, in her lyrics. It wouldn’t be out of place, one might think, to hear someone on stage reciting her lines, such as this section, the opening of the three-page poem “PLANET GRAVEL,” that reads:

I was awake all night

scrubbed of wires

and of the ribbons of veins

that used to pump

good blood around.

Mosaic flesh parts

head to toe, unpieced,

cracks blackening apart.

I ideated scrubbing

the planet gravel

with steel wool

to raw the commotion,

sheen it tender. The word

tender means kind and

loving and caring.

It means money

and pain and juicy.

How did thrall

wholly evaporate

then precipitate

me tight inside

a shucked shell

shaped just like

my body but more

lashed?

July 3, 2022

Luke Hathaway, The Affirmations

My lines insist upon what is:

you stalk me in the hill’s green gestures,

saying, Deare hart, how like you this?

Expect another, longer letter soon. (“FIRE FLOWER”)

The fourth full-length poetry title, following Groundwork (Windsor ON: Biblioasis, 2011), All the Daylight Hours: poems (Toronto ON: Cormorant Books, 2014) and Years, Months, and Days: poems (Biblioasis, 2018), and the first I’ve read by Halifax poet and composer/librettist Luke Hathaway is The Affirmations(Biblioasis, 2022), a book that examines, as much as anything else, poetic form. For example, the second piece in the collection is the extended “NEW YEAR LETTER,” a ten-part epistolary experiment across a dozen pages that opens with a lyric explanation, citing W.H. Auden’s own work in the form, the book-length poem New Year Letter (1941). As Hathaway explains:

In January 2018, I decided to try my hand at my own verse letter to a friend, a devotee of Auden, with whom I had been in conversation in person and in letter around some of Auden’s themes. Auden appears in my letter; so does the poem Richard Outram, who had died of hypothermia—his choice—a dozen Januaries earlier, and whose work I was studying at the time I wrote these lines. There are other spirits, familiar and unfamiliar—the poet Rilke, they lay-theologian Charles Williams, one of Bach’s unknown librettists, the great poet Anon…—but for the most part they are like guests at a dinner party: one doesn’t need to know their names (I hope) in order to enjoy the conversation.

As the seventh part of Hathaway’s sequence offers:

This morning I can hear the wind:

it held its fire on the morning

I was walking on the river,

talking to you in my mind,

but right now it howls around

my study. I can hear it in

this poem, the loneliness of letters:

this although the poets say

before the word was sign or symbol,

sacrament, or flesh and blood,

it was this—what? This gap, this Love.

Wiman calls Christ ‘contingency’.

What happens, to the God’s what is.

Sometimes I pray to that what is—

to help me value, as you say,

the actual over the possible,

and over freedom, yes, the good:

O da quod jubes, Domine.

Meanwhile what happens picks its way

amid the matted river sedges,

in among the hawthorn branches,

out on the wide river ice,

accident and happenstance

and chance encounter and the glancing

blow. Christ! Can one pray to that?

Hathaway sketches precision narratives across rhythms as skin across a drum, tightening the lyric when required, for higher effect. “The lights when on / and instantly // I saw it: you,” he writes, to open “EROS AND PSYCHE,” immortal; I, // consigned to any / trial your mother // might devise / (beans, rice, // golden fleece / in the thorn tree, // pick-up Styx): [.]” His is a storytelling lyric, perhaps echoing the story-and-song-telling of the libretto, composing examinations and observations and narratives that lean into the ethereal of lyric patters, lullaby, epistolary, essays and operatic nocturnes, and a wordplay of grand theatrical gestures. Hathaway seems to explore the boundaries of poetic form as it relates to an operatic storytelling, pushing at the edges of older forms with a new hand, and a new eye, and seeing what just might be possible. As part of “A POOR PASSION,” subtitled “after Bach’s Johannes-Passion,” Hathaway writes:

Hathaway sketches precision narratives across rhythms as skin across a drum, tightening the lyric when required, for higher effect. “The lights when on / and instantly // I saw it: you,” he writes, to open “EROS AND PSYCHE,” immortal; I, // consigned to any / trial your mother // might devise / (beans, rice, // golden fleece / in the thorn tree, // pick-up Styx): [.]” His is a storytelling lyric, perhaps echoing the story-and-song-telling of the libretto, composing examinations and observations and narratives that lean into the ethereal of lyric patters, lullaby, epistolary, essays and operatic nocturnes, and a wordplay of grand theatrical gestures. Hathaway seems to explore the boundaries of poetic form as it relates to an operatic storytelling, pushing at the edges of older forms with a new hand, and a new eye, and seeing what just might be possible. As part of “A POOR PASSION,” subtitled “after Bach’s Johannes-Passion,” Hathaway writes: I am not the first poet-translator, in English or otherwise, to offer up new words for Bach’s Johannes-Passion. There is a long tradition of this kind of work, which musicologists sometimes call contrafactum—a kind of poesis ‘whereby the music is retained and the words altered’ (OED). Common in medieval and Renaissance music, the practice is still with us in folk song and in hymnody—and of course in childhood: ask any six-year-old who has gleefully chanted, Joy to the world, the school burned down….The practice of contrafactum has analogies in written verse (think of stanzaic poetry) and in life. (What am I, post-transition, but an old tune with new lyrics?)

July 2, 2022

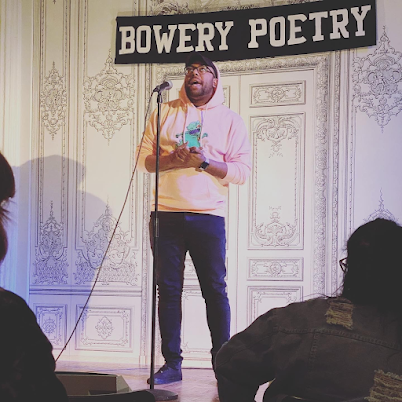

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jason B. Crawford

Jason B.Crawford

(They/Them) is a writer born in Washington DC, raised in Lansing, MI. Their debut chapbook collection

Summertime Fine

is out through Variant Lit. Their second chapbook

Twerkable Moments

is out from Paper Nautilus Press. Their third chapbook,

Good Boi

, is out from Neon Hemlock press. Their debut Full Length

Year of the Unicorn Kidz

was published in 2022 from Sundress Publications. Crawford holds a Bachelor of Science in Creative Writing from Eastern Michigan University and is the co-founder of

The Knight’s Library Magazine

. Crawford is the winner of the Courtney Valentine Prize for Outstanding Work by a Millennial Artist, Vella Chapbook Contest, and Variant Lit Chapbook Contest. They are the 2021 OutWrite chapbook contest winner in poetry. Their work can be found in Split Lip Magazine, Glass Poetry, Four Way Review, Voicemail poems, FreezeRay Poetry, HAD, among others. They are a current poetry MFA candidate at The New School.

Jason B.Crawford

(They/Them) is a writer born in Washington DC, raised in Lansing, MI. Their debut chapbook collection

Summertime Fine

is out through Variant Lit. Their second chapbook

Twerkable Moments

is out from Paper Nautilus Press. Their third chapbook,

Good Boi

, is out from Neon Hemlock press. Their debut Full Length

Year of the Unicorn Kidz

was published in 2022 from Sundress Publications. Crawford holds a Bachelor of Science in Creative Writing from Eastern Michigan University and is the co-founder of

The Knight’s Library Magazine

. Crawford is the winner of the Courtney Valentine Prize for Outstanding Work by a Millennial Artist, Vella Chapbook Contest, and Variant Lit Chapbook Contest. They are the 2021 OutWrite chapbook contest winner in poetry. Their work can be found in Split Lip Magazine, Glass Poetry, Four Way Review, Voicemail poems, FreezeRay Poetry, HAD, among others. They are a current poetry MFA candidate at The New School. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook, Summertime Fine, gave me the space to understand what MY poetics were and how they fit into the context of the larger conversation. I spent so much of my undergrad in writing trying to fit the mold of what I was being taught. As a rebel, I also tried to push against the “typical” poetic path and forge my own sense of what my poetry would hold. This pushed me to watching and reading poets such as Danez Smith, sam sax, Desiree Dallagiacomo, Porsha O, the list goes on. As a young poet, I often tried to pattern my poetics after these poets, losing my own voice in the process. Summertime Fine helped me step into my own; Year of the Unicorn Kidz is further proof of what I can do when focusing on my own narrative and voice.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Funny enough, I started as a fiction major at Eastern Michigan University. My professor, Rob Halpern, had me read my poem in front of the class that he encouraged me to rewrite. My love of poetry grew from there.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The typical first draft for me is not that long, maybe a few days per poem at most. Year of the Unicorn Kidz was completed in 3 weeks for most of the poems (some poems predated the start of the collection) however with edits, it did take a few months to hash out.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Most of my work is project based. I work best when thinking of a set goal or selected outcome of the poems. When I have an idea to work towards, I am able to put out a few poems a day towards it. However, when I am just writing to write, I often feel aimless and it takes awhile for me to produce any work that feels worthwhile.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love going to open mics, reading in front of people (even in zoom), checking to see if parts of the poem go off the way I intended during the writing process. I use reading to my friends and at public events as an editing tool, honestly. I actually use reading out loud as a tool to double check the way the poem sounds. Not only am I huge on the rhyme of my poems, but I want to make sure what I am trying to say is coming through in the poem.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My work focuses mainly on Blackness and Queerness in terms of survival and joy. Every poem, essay, fiction piece, anything I write will somehow include Blackness and Queerness because it comes from me.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This is a complicated question, we as writers are: the Visionaries, the idealist, the creators of space, the pacifist, the protesters, the builders, the Believers, and so much more. People are looking to writers to help guide society in the right direction. Sometimes this feels like too much pressure, I would love to just be a writer without the added weight, but I honestly I agree with how society looks toward writers at this moment

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

All my work goes through other writers and editors before I send it out. My little sister Taylor Byas and my darling Sofia Fey are some of the first eyes to see my work. I also go to a few workshops every couple months when I feel stuck on a piece. I believe collaboration when it comes to editing is the best form of community.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

There are two things I have been told that I hold true everyday when it comes to my craft and skills in writing: 1. You are not going to write something successful everyday nor will you successfully write everyday but that does not make you any less of a writer. 2. Taylor Byas once told me that she posts her drafts on Twitter because her favorite part of writing is sharing it with her friends.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I typically write when I can or while I’m moving around. I did, however, start a practice of writing every single day for 2022, my goal is to write 365 pieces this year. The writing is still sporadic and sometimes ends up is being completed at the end of the night, but the work is being created.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

In the creation of Year of the Unicorn Kidz, I found myself returning to Danez Smith’s Homie, Sam Sax’s Bury It, Sam Herschel Wein’s Fruit Mansion, and Hieu Minh Nguyen’s Not Here.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cheesecake, walking into an empty basketball gym, grilled ribs and mac and cheese, and Malibu cologne. Maybe hot chocolate with too much french vanilla creamer and marshmallows.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

For my first two chapbooks, music influenced me a lot. In “Twerkable Moments,” I wanted to be able to create a SoulTrain feel for the poems. We spend so much time dying, why not spend some time celebrating? In the collection I am polishing up to send out, nature and climate change play a very big role.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

It goes without saying for the first two, Danez Smith and Jonah Mixon-Webster. sam sax is also a huge influence, especially when it comes to Year of the Unicorn Kidz. Taylor Byas, not just because she is my little sister, but because she makes me want to write better. I love the ways she challenges the page. I am always working towards what she is doing (I also said I need to stop mentioning her in my interviews and here we are.)

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

My dream is to open up a nonprofit literary center for LGBT youths. A space where you are safe to be yourself and love who you want. A space filled with books that reflect who fills the seats. A space where wonderful LGBTQIA artist and writers can come speak to share what “It Gets Better” could really mean. Offering resources and space, but most of all, offering love that they might not be experiencing at home. That is something I started in 2019 and I would love to get back to that.

16 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I actually started off in the education program at Eastern Michigan University, as a math major on top of that. My passion as a child was always to write songs and play basketball, however, my father told me I had to do something practical so I chose to follow in his footsteps and start teaching. I soon learned I had a passion for teaching as well, but I could not sustain that passion during undergrad. The politics of teaching turned me off to being in a classroom. One class did help me realize I loved to write and that I could do it full time if I wanted. I am not there yet but I’m getting there.

17 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I have just started Joshua Nyugen’s book Come Clean. It is brilliant in the ways he folds language like laundry. As for most of us writing our first full lengths, it is a coming of age story, but those never get old. I am currently STUCK on Disney’s Encanto it is such a beautiful film with amazing music. Also, I can’t wait to see SING 2 because the first one has had me in a chokehold for five years.

18 - What are you currently working on?

My current project centers around colonialism and migration through storytelling and Afrofuturism. I am looking to tell the story of “what if we left this planet? What does leaving look like? What does colonization of different planets mean? Who do we leave behind in our leaving?”

July 1, 2022

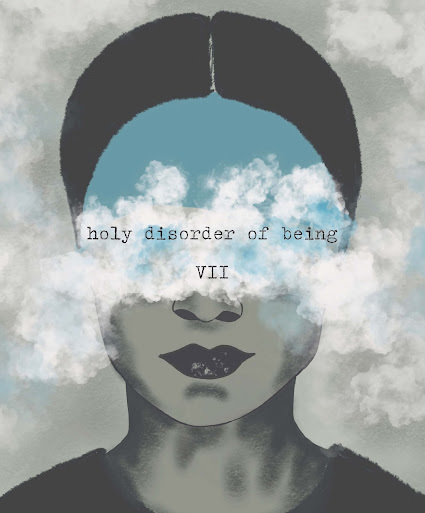

Ongoing notes: Canada Day, 2022: VII (Manahil Bandukwala, Ellen Chang-Richardson, Conyer Clayton, nina jane drystek, Chris Johnson, Margo LaPierre and Helen Robertson,

Another season of home, as the potential for nonsense descends, again, into Ottawa’s downtown. I care not for the deceptions, disruptions and dishonesties of these right-wing convoys (especially aware of how too many of them are being utilized as cannon-fodder by background interests with far darker agendas). But so it goes. Perhaps today is a day (among so many other days when such should be attended) to donate money and attention to one of the multiple charities that focus on Indigenous people and communities across the country. Happy Canada Day, indeed.

Another season of home, as the potential for nonsense descends, again, into Ottawa’s downtown. I care not for the deceptions, disruptions and dishonesties of these right-wing convoys (especially aware of how too many of them are being utilized as cannon-fodder by background interests with far darker agendas). But so it goes. Perhaps today is a day (among so many other days when such should be attended) to donate money and attention to one of the multiple charities that focus on Indigenous people and communities across the country. Happy Canada Day, indeed. Ottawa/Toronto ON: I didn’t see their collective debut, Towers (Collusion Books, 2021), I was curious to see the second chapbook-length offering, holy disorder of being (Gap Riot Press, 2022), by VII, an Ottawa-based collective and collaborative group that self-describes as “seven voices fused into one exquisite corpse: Manahil Bandukwala, Ellen Chang-Richardson, Conyer Clayton, nina jane drystek, Chris Johnson, Margo LaPierre and Helen Robertson. Based on the belief that seven minds are better than one and that many ideas make joyous chorus, we say: We are I and I is VII.” I’m fascinated by an ongoing collaborative group, aware of numerous examples of pairs of collaborators over the years, but scant examples of more than two: Pain-Not-Bread comes to mind, after the collaborations between Kim Maltman and Roo Borson brought on a third. The only other examples I can think of are sound poets, whether The Four Horsemen or Owen Sound. Are there any I’m either unaware of, or just not recalling?

take those ripped envelopes from the desk drawer

takeout containers from moth-filled cupboards, them too

take off the bovine-patterned briefs with the crotch chewed out, trash ‘em

take the soil from the shed where squirrels make scratchy holds

take up knitting or running or raking

tag friends witty Twitter posts

attack the accordion folder, sort

tackle the overgrown hard drive

tack glow-in-the-dark stars to the ceilings

tack glow-in-the-dark stars to the backs of our hands, let us

be the stars you don’t know are planets

be a green blink low on the horizon

be a moth mistaken for dust

be a memory of a library, an inflatable domed planetarium

be a rum-coloured ache the shape of a moon that’s not a window’s lemon light

not a clock’s ochre glow, not a burner left on through the night

The combined experience of the group is interesting to consider together, as every participant has published a single-author chapbook, with multiple already published first books (Manahil and Margo) and even a second (Conyer), and various of the group (Chris and nina, and possibly one or two others) have worked extensively with jwcurry as part of his sound poetry ensemble/choir, Messagio Galore. VII’s holy disorder of being appears to be exactly what their title suggests, a fragmentary, disconnected mix of styles, shapes and syntax, still feeling through what might be a rather complicated exploration to arrive at a coherent offering through seven different, distinct participants. Set as a chapbook-length assemblage of untitled fragments, lyrics pool into rhythmic and rhetorical corners before splaying off into other directions, from prose poems to full-page poems of expanded, open spacings (akin to American poets Jessica Smith or Melissa Eleftherion) to short, haiku-like bursts at the tail ends of what might be utanikki. The collection exists in a form wide open, blending a disorder into polyphony; not as a choir, but as a deliberate, ongoing collage. Either way, I am curious to see how this collective develops.

June 30, 2022

Sina Queyras, Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf

I reached up and into her sentences as though I were being pulled out of gravity because, for the first time in my life, I was encountering writing that felt organically similar to what was happening inside my mind – but, to be clear, I was not at all in control of the thoughts, or the words; my thoughts were broken here and there with clichés and fawning. Sentimentality was possible. Yes, she was sections of them all, and they were sections of her. ‘We are shaped by time and tide,’ I wrote, ‘exposed to the elements.’ I quoted directly from The Waves: ‘I have lived a thousand lives already. Every day I unbury – I dig up. I find relics of myself in the sand that women made thousands of years ago’ (127). I allowed more guessing about who, or what, Woolf was.

Of course, the question really being asked here was, who am I? (“Prologue”)

Montreal writer, editor and critic Sina Queyras’ latest title is

Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2022), a book-length essay/memoir that works through the author’s reading of Virginia Woolf, and how an early introduction to Woolf’s work offered them a way not only out but through an upbringing punctuated by abuse, poverty, loss and trauma. As Queyras’ writes early on: “It’s almost true that I have published only a handful of short stories and one novel – one that experimental novelists might argue is conventional and conventional novelists might describe as experimental – but I have, like Woolf (although certainly not at the same level as Woolf), studied, read, written, critiqued, and thought about writing across genres for more than thirty years. / Is that enough to convince myself that I might have something to say about Virginia Woolf?” Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf is an essay on influence, an essay on Virginia Woolf and a memoir of trauma, offering the details of how Queyras “got here from there”; how a discovery of Woolf’s work early on allowed them an example of how to lift beyond a dark history, and literally write themselves into the possibility of something else. “How did people who survived such trauma ever achieve smoothness in their lives? Equanimity? How did people who didn’t assume for themselves the right to safety, achieve safety, let alone perceive themselves as having a voice? As writers? Artists? Anything beyond a basic survival mode? It was bullshit. How could you tell your story if your story wasn’t one the world wanted to hear?”

Montreal writer, editor and critic Sina Queyras’ latest title is

Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2022), a book-length essay/memoir that works through the author’s reading of Virginia Woolf, and how an early introduction to Woolf’s work offered them a way not only out but through an upbringing punctuated by abuse, poverty, loss and trauma. As Queyras’ writes early on: “It’s almost true that I have published only a handful of short stories and one novel – one that experimental novelists might argue is conventional and conventional novelists might describe as experimental – but I have, like Woolf (although certainly not at the same level as Woolf), studied, read, written, critiqued, and thought about writing across genres for more than thirty years. / Is that enough to convince myself that I might have something to say about Virginia Woolf?” Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf is an essay on influence, an essay on Virginia Woolf and a memoir of trauma, offering the details of how Queyras “got here from there”; how a discovery of Woolf’s work early on allowed them an example of how to lift beyond a dark history, and literally write themselves into the possibility of something else. “How did people who survived such trauma ever achieve smoothness in their lives? Equanimity? How did people who didn’t assume for themselves the right to safety, achieve safety, let alone perceive themselves as having a voice? As writers? Artists? Anything beyond a basic survival mode? It was bullshit. How could you tell your story if your story wasn’t one the world wanted to hear?” Queyras writes of their reading and post-secondary experiences, of their relationships. They write of reading and experiencing the work of Adrienne Rich and Toni Morrison, Constance Rooke and Evelyn Lau, Jane Rule and Sylvia Plath; of academia, gender, sexuality and violence, and of linearity, writing on Woolf as figure, influence, possibility, anchor and example. “Lau wanted – and deserved – a literarycareer,” Queyras writes, describing a Constance Rooke reading and post-reading conversation during their time at the University of Victoria, and hearing the audience of predominantly older women tut-tut what they were hearing about Lau’s then-forthcoming memoir, Runaway: Diary of a Street Kid (HarperCollins, 1989), “and the way she found a book contract and entry into literature was by dragging herself through the streets and living to tell about it. Isn’t this why Sylvia Plath published The Bell Jar under a pseudonym? Because she saw that story as something not yet transformed? Too close to the bone? Something other than literature? Is this the women’s literature we’ve been fighting for?” Queyras writes of working and feeling through form and the difficulty of being present. They write of being transformed.

The text itself made me. It demanded a response. But it also literally made me.

And that is no small thing. Again and again, whenever I lose my way, I go back to Woolf. I go back to her texts and realign myself. Bring all the folds of my being into the work. I go back to the sentences that appear to contain while trajectories – subtle and extensive – and look up into them. I feel a complicated lineage. They appear before me like cathedrals and street maps, like soft spaces to settle, like flares, sent up in moments of anguish and adoration, lighting a path I can always go down. They appear like furrows of joy I might harvest. They appear like girders, vertical and reeking of futures Woolf herself could not have foreseen.

Queyras writes of an ongoing fight for space, and attempting writing not simply as a mode for thinking and responding but one through which best to experience and live. In Why Must a Black Writer Write About Sex? (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1994), referencing his infamous debut, How To Make Love To a Negro (Without Getting Tired) (Coach House Books, 1987), Dany Laferrière wrote of how he wrote that first novel to “save his life.” This is “no small thing,” as Queyras well knows, and they centre their third poetry collection, Lemon Hound (Coach House Books, 2006) as the beginning of where they wished to exist as a writer; the collection that first achieved what they were aiming for (and allowing all else to follow). Through the precise sentences of Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf, Queyras writes of the failures and attempts, the stumbles and missteps, and how Woolf remained an anchor through the worst of it. “It had been my intention to follow in Woolf’s footsteps – a ridiculous desire,” they write, early in Chapter One, “because of my impoverished education and the fact that essay writing has always been a challenge. But journalism, of a kind, and speaking to the common reader, have always been goals (as well as my first writing experience). Creatively, I wanted to try it all: write plays, novels, and essays, not only poetry. I fell, however, not to essays, but blog posts, and those devolved further into tweets. I meant to write more novels but wrote only one before I was caught up – for better and worse – in parenting and the business of a creative writing department. Or, with capital-S Service and Patriarchy.” Through Women, Writing, Woolf, Queyras writes on the pull and possibility, the destructive nature of rooms; finally able to remove themselves from one before even able to entertain another; they write on exactly what proponents of literature offer as the best example of what reading can offer: the transformative possibilities of the experience.

It isn’t until I say this out loud that I realize this is one thing I am trying to make clear in this book. the way that there can seem to be no exit at all from the trauma of the body. That it is ongoing. That we have all accepted this, not only for us, but for our children. And for our students. And that the room can be a place that keeps us apart from ourselves and the world. The room can easily become a closed door. A locked place. A prison of our own devising, or our own resignation, and that we have to get out.

June 29, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cynthia Good

Cynthia Goodis an award-winning poet, journalist, and former TV news anchor. She has written six books including

Vaccinating Your Child

, which won the Georgia Author of the Year award. She has launched two magazines, Atlanta Woman and the nationally distributed PINK magazine for women in business. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in journals including Adanna Journal, Awakenings, Book of Matches, Brickplight, Bridgewater International Poetry Festival, Cutthroat, Free State Review, Full Bleed, Green Hills Literary Lantern, Hole in the Head Review, Main Street Rag, Maudlin House Review, MudRoom, Outrider Press, OyeDrum Magazine, The Penmen Review, Pensive Journal, Persimmon Tree, Pier-Glass Poetry, Pink Panther Magazine, Poydras, South Shore Review, The Ravens Perch, Reed Magazine, Tall Grass, Terminus Magazine, They Call Us, and Voices de la Luna and Willows Wept Review, Semi-Finalist: The Word Works 2021, among others. Her new chapbook,

What We Do With Our Hands

, is published by Finishing Line Press.

Cynthia Goodis an award-winning poet, journalist, and former TV news anchor. She has written six books including

Vaccinating Your Child

, which won the Georgia Author of the Year award. She has launched two magazines, Atlanta Woman and the nationally distributed PINK magazine for women in business. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in journals including Adanna Journal, Awakenings, Book of Matches, Brickplight, Bridgewater International Poetry Festival, Cutthroat, Free State Review, Full Bleed, Green Hills Literary Lantern, Hole in the Head Review, Main Street Rag, Maudlin House Review, MudRoom, Outrider Press, OyeDrum Magazine, The Penmen Review, Pensive Journal, Persimmon Tree, Pier-Glass Poetry, Pink Panther Magazine, Poydras, South Shore Review, The Ravens Perch, Reed Magazine, Tall Grass, Terminus Magazine, They Call Us, and Voices de la Luna and Willows Wept Review, Semi-Finalist: The Word Works 2021, among others. Her new chapbook,

What We Do With Our Hands

, is published by Finishing Line Press. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book Words Every Child Must Hearimproved my life because the research for it and writing of it taught me tons about how to raise my young child. My current focus on poetry is entirely different than anything I have published in the past. My previous and continuing nonfiction work has been externally focused, with specific goals i.e. helping women advance in business, in contrast to poetry, which for me is about interiority and the possibility of expressing and communicating what words alone cannot convey.

2 - How did you come to journalism first, as opposed to, say, fiction, poetry or non-fiction?

I am a communicator. After graduating from UCLA I set out to find an on-air job reporting the news, thinking I could have some positive impact on the world by shining a light on what was happening.

Poetry is different. I turned to poetry when I felt bombarded by mainstream media at a time when the structures in my life were falling apart; my marriage of 25 years, my home bulldozed, my children graduating from college and moving on, my mother dying. In five weeks time, I became divorced, was forced out of my home and buried my mother. I realized that many of the belief systems I had learned and relied on didn’t apply any longer. I felt immersed in a media culture that rarely addressed the things that consumed me and tore me apart every day. It was extremely alienating. But then, there was poetry, waiting for me all along, a way to express experiences for which there are no words. I had discovered an entire language and realized I wasn’t going crazy. It was such a gift. I believe poetry saved my life, and continues to save me again and again.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It is organic, sometimes fast… words pouring out like a geyser. Other times not so much. Sometimes a poem will take ages to finish; most never make it out of the initial word doc. Others, on occasion, practically write themselves. I carry a small notebook in my bag, if not I will write on scraps of paper, napkins and coffee shop receipts. Ideally I’ll write in a larger notebook I keep at the house and once I move what I’ve written to the computer I cross it out on the handwritten page.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me poetry is not something that is strategic. The work dictates the process. So as themes come together and a larger project takes shape then that’s interesting.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readings are a lot of fun. Poems seem different to me when read aloud because of the sound, as well as the energy and the ears in the room. The poems themselves change a bit and maybe come more alive.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

For me poetry is about the questions. Sometimes the poem inadvertently may answer a question I have. I may think I know how it’s supposed to end but the musicality of it falls flat… so I have to add something and there you have it.. a poem that says something entirely different than I intended or wanted, which is very exciting.

I have so many questions and somehow the chance to address these questions or just raise the issue, and or find a metaphor, makes it easier to tolerate not knowing the answer. Depending on where I am in my life, the questions are different; where to live, how to live, how to age, questions about death, why we are here and grappling with opposite extremes that often occur simultaneously.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

In my journalistic work I feel a huge responsibility. For me journalism is a service. When it comes to poetry, it is much more selfish and freeing. I want it to be raw and honest. To me this is not some gift I am giving to the world. While I’ve been told my poems are empowering, this is not the motivation or goal. The objective is to be as truthful as I can, to avoid self-censorship. I think this is the space for the kind of poetry I am most attracted to. We are so good at hiding who we are and what we experience at a deeper level, that sometimes we even lose sight of ourselves. This happened to me. There needs to be a place to go to read what is unfiltered and true for the speaker. That’s why I turn to poetry.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

To have a poetry community and an editor makes a huge difference. Usually I’m writing in a vacuum. It’s a very solitary thing. It is easy to lose objectivity. I owe a debit of gratitude to my poetry community and to my wonderful editor Travis Denton.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write like no one will ever read it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s still hard to avoid the reportorial default and this is something I worked on during my MFA at NYU and still work on; how to keep the facts and even the truth from interfering with art, interfering with what the poem wants to be.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A perfect day begins with espresso, music, reading something and writing for about 30 minutes. I like to save editing for later in the day or in the evening after a glass of wine. But also love to write when I’m alone at a restaurant, and of course whenever particularly moved to do so. I do write something nearly every day.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Read anything long enough and I’m inspired. Or just simply wait till life happens, a text from my cousin David telling me that his sister-in-law died and a few days later his grandchild was born.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Other people’s colon and weed, because I rent out my home in Mexico and traces of the visitors always remain until the saltwater and mountain air washes them away. Rosemary, lavender and carnitas cooking.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I live in Mexico near the ocean so there is the constant inspiration of water, waves, whales, witch moths! and storms, and the rich life and people in this community, the stone roads and sewage that sometimes runs through the streets, the barbed wire, the guava trees and sidewalks overflowing with bougainvillea.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Adrienne Rich, Toi Derricotte, Jamaica Kincaid, Camille Dungy, Marie Howe, Catherine Barnett, Deborah Landau, Audre Lorde, and too many more to name. They are important to me because of their honesty, vulnerability and courage, and their exquisite grasp of language and playfulness with words and musicality.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Everything. Travel the world, write about everything, and truly enjoy my one amazing life.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I love to build, and had the chance to design a house in Mexico and before that a cabin in the north Georgia mountains near a waterfall. It’s a lot of fun to visualize something night after night, then turn it into something tangible. My brother does this too with a home he built on top of a red rock in Sedona, and our mother did it before us, building on the cliffs in Pacific Palisades over PCH before anyone wanted that land. Oh and I love raising animals, chickens, goats, horses like my great grandparents did when they immigrated to the US from Russia to escape the war and antisemitism years ago.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t really have a choice in the matter. My longest and deepest relationship has been with the blank page. Throughout my life the page has been my best friend and confident, never once failing to be there for me.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just read Amor Towles’ Rules of Civility and Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, which I loved. Last week I saw My Father’s Violin, which speaks to the power of art to transform relationships and lives.

20 - What are you currently working on?

My first Chapbook, What We Do With Our Hands is available for order in April 2022 and comes out this summer.

I’m continuing to write, edit and share my poems and taking a look at possible themes for another book. There is a full-length manuscript in the works as well.

June 28, 2022

Brandan Griffin, Impastoral

BAT LOCATING FROM MOUTH A

TOUR DE FORCE

—flapping over hills in no human

what sings better

at this frequency

that spreads out mapping

and returns

nightswain guiding fruit

feeling about with sound edges

a farr off paperiness

a swarm

silenscreeching, from

ipsude dwon, i mean upside down

to ridesight up,

echolocolocating

keys from my sonar

on the letters

the trees, the delicious frownflies

cellunotes

prickling births

on air glutted with sensewine,

fruit crooking me,

i go suckling after all species

why this one place that’s me

while the sououound

ripples and i

wripple in it, in faroff chimes

the city

is verywhere,

as much here

the pan frenzy fills my ears

and then no bat,

but visible audio

no shepheard

just remembrance, ocation, form

I am completely taken by the charming flips and phonetic twirls and twists of Sunnyside, New York poet Brandan Griffin’s full-length debut, Impastoral(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2022). There is such song in his ecopoetic, furthering a particular rich strain of ecological lyric that has rippled across Omnidawn publications for the length and breadth of my attention to their titles: book-length examinations of ecological possibility, articulating both the positive and negative, including indictments and responsibilities of humanity’s disruptive manner. Through the structure and content of his Impastoral, Griffin is reminiscent of the work of Brian Teare (who blurbs the back cover of the collection)[see my review of his latest here], composing moments as much physical upon the page as meditative. It’s hard not to see either Teare, or even the physicality of CAConrad [see my review of such here] through such poems as “SEW AGE TREAT MENT PLANT,” that includes:

assoon I try to thinkit itt quiets down to unlit basin no thinking

in writing how many drafts chewd cudded down below in

back of the book where you don’t you can’t look has no back of

the back of course I can speak straight and then we’ll get somewhere

but the other places th passage voids from itslef frm th linear

landscape

get ddumped

As well, the use of twisted language is reminiscent of what Conan O’Brien said of the late Norm Macdonald’s work as part of Macdonald’s recent posthumously-released final comedy special, how Macdonald would deliberately mispronounce the occasional word during talk show appearances, aiming to keep listeners attentive, and even slightly off-balance. Griffin, on his part, appears to be less about off-putting or keeping one off-balance than to offer something further, extra; a way of offering a new sequence or element of shape or sound or meaning to extend possibility, as the poem “ANIMALS LIVES IN PLANT,” offers: “un / conscious leaves / on green yarn / the / yairn falls and floats up in / telepithy [.]” The sense of play begins with the visual, rippling out into meaning and sound, prompting both pause and propulsion in ways that echo, as well, elements of the late bpNichol, Montreal poet Erín Moure or even the possibility of created and/or mismashed wordplay of Paul Celan (or Lisa Robertson or George Herriman’s Krazy Kat): offering and adding and even layering both meaning and intent. The same poem, further down the page: “plant on table in front of books / blooks on / tlable / in twowo clusters of leaves gathering up // twu upclusters of leefeafing / turn faces / w their yellow streaks to me / next to me, to // winsundowlight [.]” There is such a delightful way that Griffin’s otherwise-mangle of deliberate misspellings is compelling, welcoming and utterly charming, bringing the reader into his song of true, central awareness. Despite my own upbringing in rural landscapes, it might be only through Griffin that I can finally be able to begin to understand. Or, as the final poem of the ten-stanza “PROBE” provides:

As well, the use of twisted language is reminiscent of what Conan O’Brien said of the late Norm Macdonald’s work as part of Macdonald’s recent posthumously-released final comedy special, how Macdonald would deliberately mispronounce the occasional word during talk show appearances, aiming to keep listeners attentive, and even slightly off-balance. Griffin, on his part, appears to be less about off-putting or keeping one off-balance than to offer something further, extra; a way of offering a new sequence or element of shape or sound or meaning to extend possibility, as the poem “ANIMALS LIVES IN PLANT,” offers: “un / conscious leaves / on green yarn / the / yairn falls and floats up in / telepithy [.]” The sense of play begins with the visual, rippling out into meaning and sound, prompting both pause and propulsion in ways that echo, as well, elements of the late bpNichol, Montreal poet Erín Moure or even the possibility of created and/or mismashed wordplay of Paul Celan (or Lisa Robertson or George Herriman’s Krazy Kat): offering and adding and even layering both meaning and intent. The same poem, further down the page: “plant on table in front of books / blooks on / tlable / in twowo clusters of leaves gathering up // twu upclusters of leefeafing / turn faces / w their yellow streaks to me / next to me, to // winsundowlight [.]” There is such a delightful way that Griffin’s otherwise-mangle of deliberate misspellings is compelling, welcoming and utterly charming, bringing the reader into his song of true, central awareness. Despite my own upbringing in rural landscapes, it might be only through Griffin that I can finally be able to begin to understand. Or, as the final poem of the ten-stanza “PROBE” provides: Then I saw beyond this

froth of variables.

no I don’t quite see I have

a boundary. over

where I end, found that

I end. What to be, the strands

My directives

cauterized. Something crops up,

it’s beyond me.

June 27, 2022

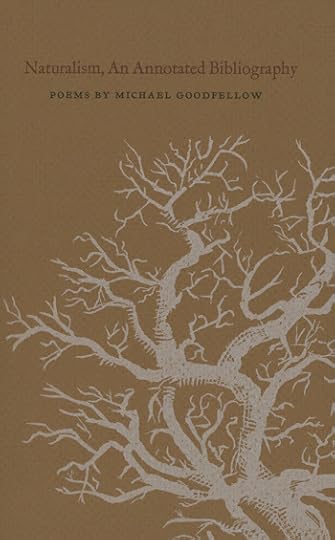

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems by Michael Goodfellow

DIESEL

Tide was a motor,

gap in the sparkplug

twisted black.

Sea shone

with undercoat,

windy days

were gears

grinding, clutch

of a storm.

Rockweed choked

the beach in wire,

cable running

the pitchy bottom.

Through rotten

cast iron, suck

of brackish water

in the basement

drain. The sump

ran all night,

jerrycan of diesel

at the basement

stairs. Nothing stopped

turning. Sunset

left a sheen.

I’m fascinated by the single, staggered, unbroken sentence of Lunenberg County, Nova Scotia poet Michael Goodfellow’s surefooted lyric as displayed in his full-length debut,

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022). Through an assemblage, nearly a suite, of short poems, Goodfellow offers a descriptive layering of landscape across the connective tissue of his self-described “small waterfront acre,” rippling slowly out from that central, singular focal point of roots, observation and interaction. He writes of home and his landscape, offering a lyric of the right words in the right order, and a tangible and concrete poetics of light across the water, the movement of human culture and sunsets, beaches and sullen hillsides. “The moon rose behind us,” he writes, as part of the poem “HIRTLE’S BEACH METONYMY,” “an animal // staring out the brush. / The thick, you called it. // You had other words for things, / you tongued them out, letting them shape // in the air, then dampen: / sand the colour of bark, // how night was the green of a burnt forest, / how years leaf-out loss, // their bloom.” Goodfellow’s approach to “naturalism” offers exactly what the word entails: the belief that everything depends upon that accurate description of detail, and his is certainly that, writing a lyric deeply attuned to his specific time and place, allowing it to breathe and react, attempting to determine and detail without overt interference. Even if a reader might know this place, this scene, Goodfellow’s tone and temper offers up a glimpse into the heart of it. “Ashley Conrad owned a general store,” he writes, as part of “HUNGRY,” “the kind that sold can goods, tobacco, salt, // whiskey, snowshoes, handwoven nets / and things the neighbours made—trade a rake // for a bristle broom, apples for a hooked rug. / The Depression was in another country. // No one along the river went hungry / or lacked a thing they needed.”

I’m fascinated by the single, staggered, unbroken sentence of Lunenberg County, Nova Scotia poet Michael Goodfellow’s surefooted lyric as displayed in his full-length debut,

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022). Through an assemblage, nearly a suite, of short poems, Goodfellow offers a descriptive layering of landscape across the connective tissue of his self-described “small waterfront acre,” rippling slowly out from that central, singular focal point of roots, observation and interaction. He writes of home and his landscape, offering a lyric of the right words in the right order, and a tangible and concrete poetics of light across the water, the movement of human culture and sunsets, beaches and sullen hillsides. “The moon rose behind us,” he writes, as part of the poem “HIRTLE’S BEACH METONYMY,” “an animal // staring out the brush. / The thick, you called it. // You had other words for things, / you tongued them out, letting them shape // in the air, then dampen: / sand the colour of bark, // how night was the green of a burnt forest, / how years leaf-out loss, // their bloom.” Goodfellow’s approach to “naturalism” offers exactly what the word entails: the belief that everything depends upon that accurate description of detail, and his is certainly that, writing a lyric deeply attuned to his specific time and place, allowing it to breathe and react, attempting to determine and detail without overt interference. Even if a reader might know this place, this scene, Goodfellow’s tone and temper offers up a glimpse into the heart of it. “Ashley Conrad owned a general store,” he writes, as part of “HUNGRY,” “the kind that sold can goods, tobacco, salt, // whiskey, snowshoes, handwoven nets / and things the neighbours made—trade a rake // for a bristle broom, apples for a hooked rug. / The Depression was in another country. // No one along the river went hungry / or lacked a thing they needed.” What intrigues about this collection is in how the lyric is textured, certain of itself while feeling out what words might best capture, or hold, more solid in its approach; a thickening lyric reminiscent of certain poems by Don McKay during the era of his Birding, or Desire (McClelland and Stewart, 1983). Or, as the fourth poem in the seven-part sequence “BOOK OF DAYS” reads, titled “Hop Bar”:

Metal slammed

to leave a hole,

water the suck

of wet dirt,

old mud, hand against

cold soil,

heart wood,

hard roots.

June 26, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sophie Mccreesh

Sophie Mccreesh is a writer living in Toronto. She is the author of

Once More, With Feeling

published by Doubleday Canada.

Sophie Mccreesh is a writer living in Toronto. She is the author of

Once More, With Feeling

published by Doubleday Canada. 1 – How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Right now, I’m just enjoying the feeling of having published my first novel. I have been appreciating all the support and kind messages from people who enjoyed the book. It makes my day when someone sends a note about the novel. I’m also really enjoying seeing people post photos.

2 – How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

For a while, I wrote poetry but then I realized I wasn’t very good, and I just stopped. At the risk of giving a boring answer, I’d say that I was drawn to fiction just from reading it when I was a kid. When I started writing, most of my stories evolved from a piece of dialogue that I found funny or interesting, so it makes sense for that to be the medium I chose. It’s also easier to for me to try and make jokes while writing fiction.

3 – How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I try not to overthink things when starting a new project. It’s important for me to try and navigate the pressures of perfection in the sense that I often remind myself that the project doesn’t need to be fully formed immediately. It’s easy for me to dwell on a piece, thinking over possible ways that it could simply be bad. For that reason, I find it useful to get a first draft out quickly without weighing in too much how I perceive its quality. I usually try and reach a point where I cut it off. My aim is to convince myself that it is the best that it can be and that only time can make it better. Then I move on to something else for a while.

4 – Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

When I write, I’m always conscious of character, as that is always the first thing I am drawn to when I am reading a novel or even watching a show. I usually start with an idea of a character in mind as well as a vague question that I want an answer to. I try to figure out the answer to whatever questions I have, writing though the character’s perspective, asking how they would respond to whatever situation I’m playing out. How can I show what I think and feel through their perspective? How is their perspective helpful? Can it add either humour or insight into the situation?

5 – Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

It’s great to share my work with my friends and I usually enjoy hanging out at whatever bar the reading is happening at. Although I feel like some of my material doesn’t always translate as well in a live reading (as a good deal of it is heavily based in dialogue), I still enjoy doing public readings. I like to see how some of the more humorous aspects of a piece will land with an audience—are people laughing, or did whatever joke I thought was funny not land?

6 – Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I usually end up writing about whatever vague, unanswered questions that feel important to me, or whatever I’m obsessed with at the time. I find that any questions or theoretical concerns I have change throughout the process of writing and publishing a short story or novel, so for that reason it’s hard to pinpoint any.

One of my goals for Once More, With Feeling was to write about female friendship in a way that was new and interesting, which I hope comes out between Jane and the character Kitty. As I kept writing, I found I was relating some of my own ideas to do with feeling vaguely inadequate while making art to the two friends. I wanted them to navigate wanting a career and a certain fear of failure.

7 – What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To get a silk pillowcase.

8 – How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s usually pretty easy for me to work on multiple projects at the same time. What I work on can depend on what mood I’m in. Sometimes, writing short stories can feel a bit more light-hearted and fun. When I’m working on a novel, I can start to take things too seriously, as I feel every scene/ interaction/ piece of dialogue must have more meaning in terms of the movement of the story.

9 – What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Although I tried to make myself into a morning person, I really only get meaningful work done at night. I think there is something about the emptiness of the late hours when everyone has already gone to bed. For a while, I was experimenting with a set word count. The number of words kept slowly decreasing until I decided it would just be better to spend a certain amount of time writing. Sometimes deleting a sentence can be as important as writing a new one.

I worked on parts of Once More, With Feeling at night after work so I would listen to electronic music to try and keep myself stimulated, awake, but not distracted.

10 – When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I try to start by reading more. Giving myself permission to pause the writing for a bit while I carve out time to read and experience new things.

11 – David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

It’s hard to speak specifically about how all these forms influence my work. I used to like to go to the AGO alone to relax and listen to music. I like it when it’s quiet and there’s no one there. I have attempted to write about music in my fiction—something that is a way for me to grasp how I relate to it personally.

Music comes up in different ways in my novel, Once More, With Feeling. The main character Jane is always conscious of what’s playing around her, trying to place the name of the song in her head. Maybe it’s a way for her to make sense of things. In a way, I think Jane views whatever music she is listening to as a way to connect to her emotions while she feels isolated and alone.

12 – What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I really like Mary Gaitskill’s writing.

13 – What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Make music. Or at least get to a point where I feel comfortable writing about it.

14 – If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would be a ballerina, simply because I love watching ballet. I also like the idea of being an architect. Sadly, I think I lack the skills for both.

15 – What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I can’t really think of a definitive moment when I decided to be a writer. Writing just feels like something I enjoy doing and feel committed to improve upon. Forgive this answer, but I always liked the idea of being a person who “writes novels.” haha

16 – What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I really enjoyed Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This. I recently watched The Lost Daughter