Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 124

June 6, 2022

Ongoing notes, still-early-June 2022: Elizabeth Wood + Simina Banu,

Isn’t it good I’ve started doing chapbook reviews again? Oh, why am I always behind on things? I know I have a couple of stacks of titles I have yet to get to (and still hope to). Perhaps I should get on that. And have you been keeping up with the interviews I’ve been posting weekly with Ottawa (either current or former) writers? More than one hundred so far!

Isn’t it good I’ve started doing chapbook reviews again? Oh, why am I always behind on things? I know I have a couple of stacks of titles I have yet to get to (and still hope to). Perhaps I should get on that. And have you been keeping up with the interviews I’ve been posting weekly with Ottawa (either current or former) writers? More than one hundred so far! And above/ground press turns TWENTY-NINE YEARS OLD in a couple weeks; can you imagine?

Montreal QC: Another title from James Hawes’ Turret House Press is Elizabeth Wood’s Outlaw, Rainy Day (2022), another pandemic/lockdown-specific project, through which Wood examines and re-examines erasure, offering both source text and erasures side-by-side. The chapbook is offered as a kind of ongoing or even final report from the period, sketched notes from a period of uncertainty, as though she works to excise or even rework time, distilling eleven erasures from an original source material of over two hundred and fifty prose poems. As her introductory notes offer: “In the case of erasure poetry, defining specific interventions mirrors the transit example above in its multiplicity of options: is it best to condense, but preserve the same spirit, tone, rhythm? Or to determine the poem’s essence, and carve away the superfluous?” Further on, writing: “At home, all I could do was to describe the outside COVID-world to my mother locked inside. Reality became medical appointments disguised as phone consults, endless work deadlines missed or botched, and a ritual of blithe pretense that all would be fine.” Her poems hold and rework the anxieties of the period, lifting up and even lifting out different elements at different points. How easily can we excise the present, or the past? How much or how little are we allowed to revise?

Standardization drives forward.

time out, fish awhile. Swirl

what matters.

Crave salt and find a dime. Or a

Field and take the leap.

Sweet salt-sweat trickles a family

in raucous chaos,

small branches overhead.

scream

Sweet saliva of discovery: taste, touch.

Rapacious heart.

Toronto ON: With a collaborative chapbook with Amilcar Nogueiraforthcoming with Collusion Books, Canadian poet Simina Banu’s latest [see my review of her full-length debut here] is the chapbook harmony in Beach Foam(Anstruther Press, 2022), a chapbook-length sequence of small points along a fragmented, almost disjointed thread. Banu composes small moments across pandemic-isolation, articulating a sloth interiority, flares of depression and other elements of mental health, what so many individuals were experiencing at different points of Covid-19 lockdown and isolation. “I can’t pronounce anesthetist.” she writes, early on in the collection. “I don’t comb my hair // because the plants survive // regardless. The ants // haven’t colonized. The mold’s benign.”

This apartment

looks like a relaxing place to die.

A sleepy sort of death,

undramatic.

Can you believe the hardwood?

It’s like a tree curled

into my kitchen.

roots tangle in my hair

and I finally do a dish

because there are no balconies

to leap from

now.

June 5, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Colleen Louise Barry

Colleen Louise Barry is an artist, writer, and teacher based in Seattle, WA. Her first book of poems, Colleen, appeared from After Hours Editions in April 2022. More at www.colleenlouisebarry.com or @colleenlouisebarry.

Colleen Louise Barry is an artist, writer, and teacher based in Seattle, WA. Her first book of poems, Colleen, appeared from After Hours Editions in April 2022. More at www.colleenlouisebarry.com or @colleenlouisebarry.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book is about to come out! I'm not sure that the fact of this book being completed and published is really a life-changing experience right now. Writing Colleen was more like a companion through change ~ not a major catalyst but a subtle process, or a container. Like a friend or a healing ritual.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

It's all mixed up. I have always been writing something in some way, painting and calling it narrative, building installations and calling them poems. My way of being in the world is making things. Language is an always accessible and infinitely rich material with which to do so.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A long, long time. I allow myself to operate under zero pressure in my writing life. Colleen took six years to write with large gaps of just not writing at all, or writing only by revising. I let poems come to me however they wish. Sometimes quickly while I'm driving to the store or some such thing, sometimes piece by piece over years. I do like to try to fit lines together, images together. There's just no set way. Creativity is equivalent to flexibility and receptivity. For me, that's the thrill.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Making a book was never a concrete goal for me. My poems are independent little creatures. They spring up from anywhere and we get to know each other.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I completely understand and respect poets who value and uphold the tradition of poetry as an oral, performative art. But for me, poems are on the page and their life is there. I really want anyone who reads my poems to get that private intimacy with them, without my intonation and timbre echoing in their heads. I do not enjoy reading my work aloud. I don't particularly even feel like the voice with which I speak out loud is the voice of the poems. Even though it was me who technically wrote the book, the Colleens in Colleen aren't really me. They could be anyone.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The current questions are all the old questions, too. Can we understand how language creates our reality and can we overcome its limitations? Is it possible to create a better world with words? What is underneath words; is it meaning? What is the nature of meaning without language? Is language our bridge to truth, or is it the veil obscuring it? Why are things funny? Why are things sad? Why am I me?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer's role is to inform and challenge. Writers should use their material (language) to change the way people see each other and to open them to alternative understandings of their world. I think it is true that excellent writing engenders empathy ~ empathy being the most essential ingredient to our species' survival.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I did not find outside editors particularly essential until I was ready to consider the poems in Colleen as a larger collection. I wasn't sure how to do that effectively ~ package them, order them, say confidently: these poems go together and you should buy them as such. Other than that, between myself and the poem I'm writing, there seems to be plenty of opinions already flying around.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Work hard with ease. Simple, true, a kind of relief.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (solo to collaborative work, poetry to multidisciplinary work)? What do you see as the appeal?

I love and in some ways need to move between genres all the time. My work informs my other work. It's like its own little ecosystem of creativity.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I dream of being a writer with a routine. I am, however, decidedly not. I write when I get that feeling to write ~ a feeling that is hard to describe. It's like a swelling in the chest. I drift off into another mode of observing. When that hits, no matter where I am, I write the words down. I use my iPhone notes a lot, or a little spiral notebook I bring around, or sometimes scraps from my bag, or the back of my hand.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I do not stress about this much. I just work on something else, a drawing or sculpture or dinner or anything. I also love to read. Reading always inspires me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Grass and dirt, wet dogs, a fireplace going out.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music was a huge part of Colleen. I love the way songs create intimacy with the listener. I also love the way a song can play over and over and over again, that it can come to mean a moment in time, that it can come to define a version of you. It's yet another reason I named the book after myself. Cher has Cher, Britney has Britney, why can't I call my debut book Colleen? (That's halfway a joke, but the serious half is very serious.)

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love any writer that can capture the absurdity of life with empathy and humor. Joy Williams, Emily Hunt, Wallace Stevens, Virginia Woolf. A certain precision with language. I love writers who know how to research. I am honestly blown away by contemporary journalists who have perhaps the most difficult job of all. They must use their writing like a weapon in defense of humanity, equality, democracy, science.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

This question makes me think about a piece by Jean Chen Ho that I read in the NY Times this morning, sitting in bed with my partner and my cat and some coffee. It was about the subjunctive tense and the power of grammar. She writes: "A subjunctive mode of inquiry uses narrative 'both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling...'"

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I am currently a middle school art teacher at an independent school in Seattle. It's what I'm supposed to be doing and probably what I always would have done.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I certainly do other things alongside writing. I love words and I love to play. I am curious about everything. And I want to communicate. I think it all just falls into line. I followed my heart to writing, as I have to almost everything else.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

My favorite recent books:

Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman by Robert K. Massie. Hoarders by Kate Durbin. My People The Sioux by Luther Standing Bear. We Die in Italy by Sarah Jean Alexander.

My favorite recent movies:

Licorice Pizza . The French Dispatch . Donkey Skin . Bull Durham . Into the Blue . Cutie and the Boxer .

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm working on daily sanity, a positive outlook, a lesson plan about action painting, a novel, a series of giant and soft artist books, an animatronic ride-turned-installation called "The Love Tunnel".

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 4, 2022

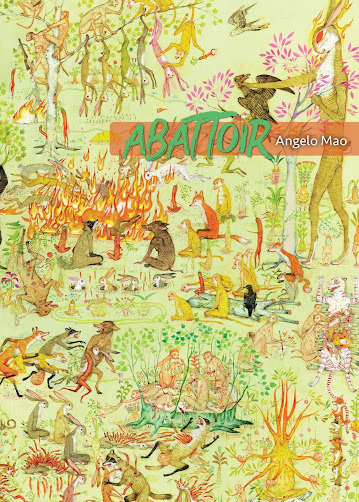

Angelo Mao, Abattoir

BIRD

What is a bird? How much does it cost? How much does its cage cost? The going price for laboratory mice is twenty six dollars an animal. What is it for birds? They used to sell them around the river, dry wicker cages, dried ribs like parallel construction. They sold them before I was born. How much did one cost then? How much would it cost not to be silent? You do not speak for yourself. Not while doing science. Abandon the project. Go back. go into the cage. Write about what you know. Tell me how to lower my voice near enough to silence so that the whole world can be heard, even the windings inside of this body can be heard, and finally I will know what stepped onto the park grounds and make an about face, turns around to look.

It turns out we know nothing about birds, neither the birds that have returned to the ponds, nor the ponds themselves, artificial as slaughter, whose overgrowing weeds are pulled out each night and burned. (Who does the burning? Where do they put the ashes?) Late night, walking home by the re-growing, re-heightening reeds slender as the knife tracks on a butcher’s board, I saw one bird hop branch to branch, like all of its kind baring a fantastically large breast, a rust red quarrel with air. I stopped. I looked.

Winner of the 2019 Burnside Review Press Book Award, as selected by poet Darcie Dennigan, is California-born Massachusetts poet and research scientist Angelo Mao’s full-length debut, Abattoir (Portland OR: Burnside Review Press, 2021). Constructed as a suite of prose poems, lyric sentences, line-breaks and pauses, Mao’s is a music of exploration, speech, fragments and hesitations; a lyric that emerges from his parallel work in the sciences. “They have invented poems with algorithms.” He writes, as part of the untitled sequence that makes up the third section. “They can be done with objectivity.” Set in four numbered sections, the poems that make up Mao’s Abattoir are constructed through a lyric of inquiry, offering words weighed carefully against each other into observation, direct statement and narrative accumulation, theses that work themselves across the length and breath of the page, the lengths of the poems. “The first thing it does / Is do a full backflip,” he writes, to open the poem “Euthanasia,” “Does the acrobatic mouse / Which rapidly explores / The perimeter comes back / To where it started / To where it sensed / What makes its ribcage / Slope-shaped as when / Thumb touches fingertips [.]” This is a book of hypotheses, offering observations on beauty, banality and every corner of existence, as explored through the possibilities of the lyric. Or the first stanza of the two-page “Dissection” reads:

Winner of the 2019 Burnside Review Press Book Award, as selected by poet Darcie Dennigan, is California-born Massachusetts poet and research scientist Angelo Mao’s full-length debut, Abattoir (Portland OR: Burnside Review Press, 2021). Constructed as a suite of prose poems, lyric sentences, line-breaks and pauses, Mao’s is a music of exploration, speech, fragments and hesitations; a lyric that emerges from his parallel work in the sciences. “They have invented poems with algorithms.” He writes, as part of the untitled sequence that makes up the third section. “They can be done with objectivity.” Set in four numbered sections, the poems that make up Mao’s Abattoir are constructed through a lyric of inquiry, offering words weighed carefully against each other into observation, direct statement and narrative accumulation, theses that work themselves across the length and breath of the page, the lengths of the poems. “The first thing it does / Is do a full backflip,” he writes, to open the poem “Euthanasia,” “Does the acrobatic mouse / Which rapidly explores / The perimeter comes back / To where it started / To where it sensed / What makes its ribcage / Slope-shaped as when / Thumb touches fingertips [.]” This is a book of hypotheses, offering observations on beauty, banality and every corner of existence, as explored through the possibilities of the lyric. Or the first stanza of the two-page “Dissection” reads: Bodice the color of rose. Ligaments

of cream. Undone: parted. Opening

and for a brief moment hooking breath

to a forced, indrawn stillness so as not

disturb whatever hypothesis might arise,

nor disturb the forceped hand that enters

with its set of impersonal instruments

as formal as beauty.

June 3, 2022

Ongoing notes: early June, 2022 : Douglas Piccinnini + Sarah Burgoyne,

Did you notice when we posted a new poem-a-day throughout April over at the Chaudiere Books blog, as part of our ninth annual acknowledgement of National Poetry Month (I mean, you did notice that, right?). And of course, the new issue of

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, where I’ve also been interviewing the shortlist for this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize?

Did you notice when we posted a new poem-a-day throughout April over at the Chaudiere Books blog, as part of our ninth annual acknowledgement of National Poetry Month (I mean, you did notice that, right?). And of course, the new issue of

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, where I’ve also been interviewing the shortlist for this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize? New England: I’ve been going through American poet Douglas Piccinnini’s [see my 2016 “12 or 20 questions” interview here] latest title, the chapbook A WESTERN SKY (Greying Ghost, 2022), a lovely title produced in a numbered edition of seventy-five copies. Piccinnini’s A WESTERN SKY is a twenty-nine poem sequence of fragments composed as a lyric meditation on change and space. He writes an abstract sequence on breaks and blocks, attempting to reach beyond the boundaries of this sequence of sketch-out notes into something larger. “Money, no money – // say where to speak and break,” he writes, early on in the collection, “the clockhands as my own. // The hands of a prisoner speaking up. // Don’t let them hit you. / Don’t let them take you apart.”

The future approaches as if it were fixed—no

days but days multiply. Rooms of a house

you know and have entered—remember

change—this custom like a place you feel

studded in a sky, swept away, in a substance

like a signal departing as it arrives, to keep time

to see a tree top touched breeze

to say that, for example, you lose

the keys everywhere to find them.

Montreal QC: You’ve probably heard that Montreal poet James Hawes started a chapbook press, yes? Over at his Turret House, one of the most recent titles is Sarah Burgoyne’s Double House (2022) [see my review of her latest book here], a handful of poems composed during, as she writes in a brief note to introduce the poems, “domestic exile,” thanks in no small part to Covid-19 lockdowns. As she writes: “Something had begun to come up in the poems I was writing and the poems my friends were writing: domesticity (b)loomed. Our interior spaces puffed up their lungs and insisted on their presence in our work. I started to see my home more and more like a living body—with currents, with moods, with breath (sometimes poisonous), with infection, also. I came to know much more intimately the rhythms of my hitherto unknown housemates (a pigeon and a mouse) and they inevitably made their way into my poems. In a way, through domestic exile and through these poems, I discovered the porousness of my home’s conceptual borders (and its physical borders every time the mouse emerged).” I’m fascinated by the shifts in Burgoyne’s work through this small collection, an assemblage of experiments, one might say, as much as anything else, flexing her muscles and seeing what other possibilities the lyric might offer, or allow. Also, there’s something really interesting in the way she notes at the back of the collection, how the poem “Double House Poem” was composed “by adapting one of C.A. Conrad’s (Soma)tic exercises. I studied the light in every room of my house. I listened to my refrigerator. I made myself steamed broccoli with olive oil and salt. I lay on the floor listening to Philip Glass’s ‘Music in Contrary Motion’ and reflected on violence.’” Honestly, in many ways, the writing she offers to speak of her writing, and her process, is equally interesting to the writing itself, and this small collection offers tidbits of both. And the poem itself, “Double House Poem,” that includes:

The sink is my palm, upturned on the floor

for you. Think of your house. Descend.

The fig tree’s shadow is a ladder

for you to climb.

Press your ear to the fridge

inside is a cautious poet echoing your poem.

June 2, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Phil Goldstein

Phil Goldstein is a poet, journalist and content marketer. His debut poetry collection,

How to Bury a Boy at Sea

, was published by Stillhouse Press in April 2022.

Phil Goldstein is a poet, journalist and content marketer. His debut poetry collection,

How to Bury a Boy at Sea

, was published by Stillhouse Press in April 2022. His poetry has been nominated for a Best of the Net award and has appeared in The Laurel Review, Rust + Moth, Two Peach, 2River View, Awakened Voices, The Indianapolis Review, Linden Avenue Literary Journal and elsewhere.

By day, he works as a senior editor for a content marketing agency, writing about government technology. He currently lives in Alexandria, Va., with his wife, Jenny, and their animals: a dog named Brenna, and two cats, Grady and Princess.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m still figuring that out, since How to Bury a Boy at Sea is my first book and it’s just been published. I can say that already it’s afforded me the opportunity to connect with a wide range of people and groups interested in preventing and helping others heal from child secxual abuse, which the book reckons with. That includes survivor groups, abuse prevention organizations, mental health professionals and others. And that’s been very rewarding. It’s also been incredibly heartening to hear from people who have purchased a copy – or who have passed along info about the book to others in their lives – who are also survivors of abuse, and tell me that it’s helped them feel less alone. That’s a huge goal of the work.

In terms of how it compares to earlier work it’s hard to say since almost all of my previously published poems are in this book. It’s definitely been the most intense and difficult and rewarding creative experience I’ve had in my life up to this point.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry when I was in seventh grade and wrote it through high school and into college, with my work in my college years being more of the slam poetry/spoken word variety. And then after I graduated and got a job it basically fell off and I was consumed with my writing for work, which has been business and technology journalism. I was always an incredibly avid reader of both fiction and non-fiction growing up, but poetry always spoke to me in a way that other forms of writing never did. My mom got me this anthology of American poetry aimed at kidswhen I was 11 or 12, which actually coincided with when I was being molested, and poetry as an art form just really stayed with me, as a way to express really complex feelings.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My writing comes in bursts or spurts, I would say. I’ll be walking the dog or in the shower or making dinner and an image or a line will pop into my head and I’ll write it down, and sometimes start jotting down the first draft of a poem on my phone. And there are weeks or months where that happens and I write half a dozen poems in a pretty short period of time. And then there are times where I’m not writing anything creative for weeks or months at a time because things are busy at work or in our household or in the world – there’s still a pandemic raging! – and that’s frustrating.

I would say there are a few poems in my book that came out relatively fully formed and required very minimal edits before they became their final form. But I think, like most writers, the vast majority of my finished work is the byproduct of multiple rounds of revision.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems always begin for me as an image. And then I build the architecture of the poem around or leading up to that image. Since I’ve only had one book published so far I can’t say that I’ve really written with a larger project in mind over a long period of time, except for this book. I think once I had written a dozen or two dozen poems dealing with the abuse that my then-girlfriend and now-wife really encouraged me to think of this as a potential book, so I have to give such immense credit to her for that.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ve always been a bit of a performer and did musicals in high school and slam poetry in college, so I really enjoy doing public readings. I enjoy reading poems on the page, sometimes aloud to myself, but I am definitely one of those poets who thinks that poetry was and is intended to be spoken out loud, hopefully in front of a decently sized audience of people. I think that poetry is obviously meant to evoke emotions in people who are reading or hearing it, and so I see public readings of poetry in the same way that I see public performances of music or people gathered in a movie theater. They’re all there to experience art and will all be influenced or affected in unique ways. I think that’s wonderful and as COVID-19 hopefully becomes more of an endemic disease over time and cases go down I really hope there is this burst of public readings. I love public readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wouldn’t say there are theoretical poetry concerns that I’m preoccupied with, but I think a deeper question my work confronts is, What does it mean to survive a trauma? Anyone who has experienced trauma in their lives has their own individual response to that trauma. And there’s no one “right” way to respond or heal from trauma. Everyone’s response is so particular and multifaceted, and so I want to explore that kaleidoscope of emotions and experiences. A corollary is, What does it mean to live a full life? No one is or should be defined by the worst thing that’s ever happened to them. There is obviously pain and suffering in life but there is joy, love, intimacy, connection, wonder. What does that look like in connection to the darker aspects of our existence?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writers at large continue to play the role of interpreting and explaining the human condition to others. Whether or not that is understood or appreciated by the public at large is an entirely open question in a world where the culture is so fragmented and atomized and our politics are so polarized. I think poets, in particular, have a responsibility to address and illuminate aspects of the human condition that do not get a lot of attention in other aspects of the culture, whether that’s TV, movies, the news media or anything else.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Editors are and will continue to be absolutely essential in my mind, whether that’s friends serving as informal editors or editors you are working with for a project that is under contract. My work would not look and sound the way it does without the incredible insight of editors. Sometimes one might disagree with their perspective, but those perspectives are totally essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Pare down your writing to the essential elements and lose the unnecessary ornamentation. What is it you are trying to convey with this one particular image or series of lines?

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I enjoy writing both and find it relatively easy to move between both since I write and edit news articles and narratives for living. I think poetry allows you to address emotions, thoughts and experiences in an abstract way and essays are appealing because they enable you to build an argument in a more straightforward way.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I honestly do not have a set routine for creative writing. I write so much during the week for my job that I try to snatch time whenever I can in the evenings on the weekends to work out poems or other creative work.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The work of poets I either know or am just discovering whose poetry makes me feel electrified. A long walk in the woods or along a body of water also always helps.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

For where I grew up: chicken wings (from my favorite restaurant in my hometown). For where I live now: the perfume and hand lotion my wife uses.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music is definitely a big influence for me. I listened to a lot of music while writing the poems that became my book and I even created a Spotify playlist to celebrate those songs and instrumental pieces that I think really resonate with the book’s themes or emotions I want to evoke. And being out in nature always inspires me and reminds me of the precious beauty of this fragile world.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

This could go on for a while so I will try to name just a few: Louise Glück, Walt Whitman, Adrienne Rich, Nikki Giovanni, William Faulkner, James Baldwin, Jericho Brown, Rainer Maria Rilke and Lucille Clifton. Whenever I read their work I am blown away.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d love to spend a significant period of time in a place that’s pretty disconnected from civilization, deep in nature. I’d also like to go skydiving at some point.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think maybe a nature or news photographer. I like taking photos on my phone but it would be amazing to get paid to take photos.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve always been writing in one form or another, going back almost as far as I can remember, so I’m not sure.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read is hard to pick! The last great novel I read is The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. I’ve also read some fantastic poetry collections in the past year, including Rachel Mennies’ The Naomi Letters and Catherine Pond’s Fieldglass. The last great film I watched was The Power of the Dog, which I watched at home with my wife. It’s such a beautiful, intriguing film. The director, Jane Campion, is a genius.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’ve been trying to work on some new poems where and when I can, but it’s honestly been tough lately amid my day job and work I’ve been doing to promote How to Bury a Boy at Sea. Hopefully I’ll encounter another burst at some point soon.

June 1, 2022

Ivan Drury, Un

history too erects signposts

“eighty years from Siberia:

to become it a place different

a Solzhenitsynist Tolkienite cloud world

never from we here

Bagram does not disappear

Guantánamo does not torture

no distance: no sign

where I grew up

we were all “middle class” and

everybody was “white”

all the time (“Enter the Municipality of Blacksite / (A Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone)”)

From BC-based editor and writer Ivan Drury comes the full-length debut,

Un

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2022), a book titled through a curious echo (for certain readers, at least) back to Toronto poet Dennis Lee’s own poetry title of the same name, published by Anansi in 2003. Where Lee offered his Unas the first step in a two-volume bookend around an undefinable space, Drury composes a language-lyric to acknowledge the lost, dismissed, overlooked and disappeared, writing the negative space around an ongoing colonial occupation. “I am casting off from Canada in search of un,” he writes, early on in the collection, as part of the poem “Chainlink’d,” “as though my recognition could be a cure [.]” Drury’s Un writes a lyric of trauma and witness, accessing elements of lyric and language writing, allowing a musicality that also offers echoes of the poetic structures of such as Jeff Derksen, Renée Sarojini Saklikar or Danielle Lafrance. “the spectre of apocalypse / has no folk songs,” he writes, as part of “The Spectre of Apocalypse,” “has poems only to remember / and organize genocide // has martyrs only to apocalypse // has no Victor Jara / to conduct handless the detained thousands / and raise soulful song / against fascism [.]” He writes of the US “War on Terror” and the disappeared, from America through the Middle East to North Africa, writing the spaces around what is impossibly silent, unknowable and numb.

From BC-based editor and writer Ivan Drury comes the full-length debut,

Un

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2022), a book titled through a curious echo (for certain readers, at least) back to Toronto poet Dennis Lee’s own poetry title of the same name, published by Anansi in 2003. Where Lee offered his Unas the first step in a two-volume bookend around an undefinable space, Drury composes a language-lyric to acknowledge the lost, dismissed, overlooked and disappeared, writing the negative space around an ongoing colonial occupation. “I am casting off from Canada in search of un,” he writes, early on in the collection, as part of the poem “Chainlink’d,” “as though my recognition could be a cure [.]” Drury’s Un writes a lyric of trauma and witness, accessing elements of lyric and language writing, allowing a musicality that also offers echoes of the poetic structures of such as Jeff Derksen, Renée Sarojini Saklikar or Danielle Lafrance. “the spectre of apocalypse / has no folk songs,” he writes, as part of “The Spectre of Apocalypse,” “has poems only to remember / and organize genocide // has martyrs only to apocalypse // has no Victor Jara / to conduct handless the detained thousands / and raise soulful song / against fascism [.]” He writes of the US “War on Terror” and the disappeared, from America through the Middle East to North Africa, writing the spaces around what is impossibly silent, unknowable and numb. Offering theory, poverty and politics through language, Drury’s is a documentary poetics, one propelled by an insistence upon acting as witness, reminiscent of contemporary titles such as Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas (Graywolf, 2017) [see my review of such here] or Cecily Nicholson’s From the Poplars(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here]. “this new Canada is at once academic and trrrrtrrrrial,” he writes, as part of the sequence “K. to the Prison of Grass,” “hard at the edges and marrow where the lives meet the days // pungent grey marrow // at the joints of these bones is / the lubrication of grinding contact [.]” His poems articulate the questions of how to continue, to move forward and not simply endure but thrive, fully aware that survival must certainly come first. Imagine the direct force of Winnipeg poet Colin Smith [see my review of his latest here], perhaps, but with a lyric edge. “The combustion of the sun’s daily nuclear fusion,” he writes, to close the poem “On Engels’s Dialectics of Nature,” “confronts the dark waters of the deepest craters of the / earth // as primary contradiction / as negation of negation // the purest synthesis of opposites / is humidity [.]”

May 31, 2022

Gary Barwin and Gregory Betts, The Fabulous Op

O this is a

poem become

minded whole

a great white

washed shall

adios

various radios

radiate variants

pliant plaints

record prophets

this wobbly planet

where poems

splint winds

I’ve been eager to explore titles from Beir Bua Press, an Irish publisher that appeared to emerge out of nowhere a short while back, and seemingly publishing stellar works of experimental writing from the get-go; the first of their titles I’ve managed to get my hands on is Hamilton writer Gary Barwin and St. Catharine’s, Ontario writer Gregory Betts’ collaborative The Fabulous Op (April 2022), a book of collaborative play, response and experiment through a bleed of text and image. “re new / re new grief / re language rising / re broken laugh / re always,” they write, mid-way through the collection, “recomposing / as what you / riot / you art [.]” Barwin’s collaborative explorations have become more prevalent over the past few years, although he’s been working in the form for some time, and this particular collection seems an extension of their previous collaborative effort, The Obvious Flap (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2011). As they offer as part of a preface:

The title of our book, The Fabulous Op has nothing whatsoever to do with its anagrams, “about hopefuls,” or “hub of foetal soup,” “Uh, upbeat fools,” “push taboo fuel,” or even, “Afoul pub ethos.” Rather, it is a collaborative poem which we—uh, upbeat fools—began by asking our social media contacts to post lines of poetry that they keep memorized, wanting the project to be grounded in the soil of the brain, the canon of the individual as sieved through their experience. We considered how the transmission of DNA is affected by the experiences of those who it both creates and describes through epigenetic processes. We imagined the canon (and our culture) to be a kind of genetic code who’s transmission is similarly affected by “the experiences of those who it both creates and describes” (unacknowledged source).

For the curious, other collaborative efforts by Gary Barwin include a forthcoming collaboration with Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov—Duck Eats Yeast, Quacks, Explodes; Man Loses Eye (Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2023)—two recent full-length collections with London, Ontario poet Tom Prime—A CEMETERY FOR HOLES, poems by Tom Prime and Gary Barwin (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Bird Arsonist

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2022) [see my review of such here]—

Frogments from the Frag Pool

(with derek beaulieu; Toronto ON: The Mercury Press, 2005),

Franzlations: the Imaginary Kafka Parables

(with Craig Conley and Hugh Thomas; New Star Books, 2011) [see my review of such here] and the collaborative novel

The Mud Game

(with Stuart Ross; The Mercury Press, 1995), as well as chapbook-length collaborations with Alice Burdick, Amanda Earl, Tom Prime and even myself. Ever since the publication of Barwin’s For It Is a PLEASURE and a SURPRISE to Breathe: new & selected POEMS, edited with an Introduction by Alessandro Porco (Hamilton ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2019) [see my review of such here], I’ve been curious at the possibility of editor Porco perhaps furthering his examination of Barwin’s ouvre with a volume of selected collaborations; it would be interesting to see the length and breadth of that particular and seemingly ongoing thread of his work. And one might argue, in certain ways, that everything Betts’ produces is in some way a “response,” from his collaborative efforts to his own solo projects, including

The Others Raisd in Me

(Pedlar Press, 2009), a collection of poems carved out of William Shakespeare’s sonnet 150 [see my review of such here], collaborative works with Arnold McBay, as well as the ongoing “Mutter Sound” collaborative project with Barwin and Toronto dub poet Lillian Allen.

For the curious, other collaborative efforts by Gary Barwin include a forthcoming collaboration with Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov—Duck Eats Yeast, Quacks, Explodes; Man Loses Eye (Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2023)—two recent full-length collections with London, Ontario poet Tom Prime—A CEMETERY FOR HOLES, poems by Tom Prime and Gary Barwin (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Bird Arsonist

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2022) [see my review of such here]—

Frogments from the Frag Pool

(with derek beaulieu; Toronto ON: The Mercury Press, 2005),

Franzlations: the Imaginary Kafka Parables

(with Craig Conley and Hugh Thomas; New Star Books, 2011) [see my review of such here] and the collaborative novel

The Mud Game

(with Stuart Ross; The Mercury Press, 1995), as well as chapbook-length collaborations with Alice Burdick, Amanda Earl, Tom Prime and even myself. Ever since the publication of Barwin’s For It Is a PLEASURE and a SURPRISE to Breathe: new & selected POEMS, edited with an Introduction by Alessandro Porco (Hamilton ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2019) [see my review of such here], I’ve been curious at the possibility of editor Porco perhaps furthering his examination of Barwin’s ouvre with a volume of selected collaborations; it would be interesting to see the length and breadth of that particular and seemingly ongoing thread of his work. And one might argue, in certain ways, that everything Betts’ produces is in some way a “response,” from his collaborative efforts to his own solo projects, including

The Others Raisd in Me

(Pedlar Press, 2009), a collection of poems carved out of William Shakespeare’s sonnet 150 [see my review of such here], collaborative works with Arnold McBay, as well as the ongoing “Mutter Sound” collaborative project with Barwin and Toronto dub poet Lillian Allen. Through the pieces of The Fabulous Op, Barwin and Betts offer twists of anagrammatic text and puns, texts shaped and re-formed as image, and images recombined and reconstituted, blending shifts and structures and expectation. There are ways in which their explorations of visual and sound exist almost prior to any consideration of meaning, less tethered to the possibilities of how words and images form meaning than the sense that their collage-suites of visual and aural explorations might provide. While their medium might heavily include language, one might attempt to seek meaning from their explorations in the same way one might seek similar from the paintings of Roy Kiyooka, an album by Dave Brubeck or a recorded performance by either The Four Horsemen or the Nihilist Spasm Band. The expectations of how one reads becomes important. Flip through the collection, and catch what they are doing. Can you see what they’re doing?

I am

rose ellipse this

wendering nothing

in-sparkling nothing

onsettling in air

moorning

May 30, 2022

Charles Rafferty, A Cluster of Noisy Planets: Prose Poems

Greetings

I counted the water towers, the active smokestacks. These were the breadcrumbs I thought would lead me back. Now I know it’s possible to drive so far we forget why we left, that the journey continues even after the car breaks down. I used to think I had no message, but the message is me—bloodshot and hungry, spilled coffee down the front of my shirt. People of the future, father round. I have traveled through ink to greet you.

The latest from , following eight chapbooks and six full-length collections of poetry, most recently

The Smoke of Horses

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2017) [see my review of such here], is

A Cluster of Noisy Planets: Prose Poems by Charles Rafferty

(BOA Editions, 2021). As I mentioned in my review of that prior collection, there are elements of his prose poems that lean up against an arbitrary and very fluid boundary between poetry and prose into the work of short story writers such as Lydia Davis, composing as much in the realm of postcard story as lyric prose poem. “The moon shows up like a cigarette hole,” he writes, to close the poem “Less Buoyant,” “and the weather keeps milling our mountains into sand.” He composes narratives, but one with a compelling music across his lines as important as the words and his placement of them. I’m also reminded of American writer J. Robert Lennon’s remarkable short story collection Pieces for the Left Hand (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2005) through the way that Rafferty paints such miniature portraits of scenes, moments and occurrences of action and/or thought. Across sixty short, individual and single-stanza prose poems, Rafferty composes short narratives and musings on beauty, attention and meaning, history and memory, and what sits beyond his front step.

The latest from , following eight chapbooks and six full-length collections of poetry, most recently

The Smoke of Horses

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2017) [see my review of such here], is

A Cluster of Noisy Planets: Prose Poems by Charles Rafferty

(BOA Editions, 2021). As I mentioned in my review of that prior collection, there are elements of his prose poems that lean up against an arbitrary and very fluid boundary between poetry and prose into the work of short story writers such as Lydia Davis, composing as much in the realm of postcard story as lyric prose poem. “The moon shows up like a cigarette hole,” he writes, to close the poem “Less Buoyant,” “and the weather keeps milling our mountains into sand.” He composes narratives, but one with a compelling music across his lines as important as the words and his placement of them. I’m also reminded of American writer J. Robert Lennon’s remarkable short story collection Pieces for the Left Hand (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2005) through the way that Rafferty paints such miniature portraits of scenes, moments and occurrences of action and/or thought. Across sixty short, individual and single-stanza prose poems, Rafferty composes short narratives and musings on beauty, attention and meaning, history and memory, and what sits beyond his front step. Evolution

The ice used to be a mile thick above your house, and every now and then the river uncovers a shard of Colonial flatware, an arrowhead, a piece of beer bottle incapable of cutting anything. The fragments add up. They tell us the story of how nothing can stay the same. I no longer worry that caterpillars are destroying my only oak. I don’t care if the Planning and Zoning Board approves another nail salon. Whenever you say that you’ll never leave your husband, I remind myself that whales used to live on land, that they weren’t much bigger than dogs.

It might be fair, as well, to refer to this particular collection as a kind of commonplace or sketchbook, composed of short pieces attending to the daily moments across his immediate scope of vision. If I had blurbed this collection, I might have offered: “Charles Rafferty strolls around his landscape, both internal and external, and takes pictures using only words.” There is something in the way Rafferty captures the essence of an idea or a moment across the short span of a sentence, or a collection of sentences; the way he encapsulates it, offering it up for a far broader and wider spectrum of readings. In certain poems, the distances he manages to cover from one end of the stanza to the other is quite stunning, and I find myself rereading almost in disbelief at what his narratives have accomplished, as though some of the most important elements of each poem is set not in the words he chooses or how he chooses them, but in what he sets amid and even beneath them. One marvels at what reads so easily, and yet, so utterly beautiful, wrenching and complex.

Evidence

On the map I have, the topographic lines of this hill look like God forgot to wipe away his fingerprint before he got into his Bible and fled. I knew one of the murdered boys. I had handed him a tissue once, to wipe his nose, as my daughter played piano at her recital. The apologists are full of mysterious ways, but I know evil when I see it. I can feel the thumb above me now, pressing down, fitting the grooves of this hillside.

May 29, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Robert Hough

Robert Hough

has been published to rave reviews in fifteen territories around the world. He is the author of

The Final Confession of Mabel Stark

(Vintage Canada, 2002), shortlisted for both the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for best first book and the Trillium Book Award;

The Stowaway

(Vintage Canada, 2004), one of the Boston Globe’s top ten fiction titles of 2004;

The Culprits

(Vintage Canada, 2008);

Dr. Brinkley’s Tower

(House of Anansi, 2012), shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for fiction and longlisted for the Giller Prize;

The Man Who Saved Henry Morgan

(House of Anansi, 2015), a finalist for the Trillium Book Award; and

Diego’s Crossing

(Annick Press, 2015), shortlisted for the Arthur Ellis Award. Hough lives in Toronto, ON.

Robert Hough

has been published to rave reviews in fifteen territories around the world. He is the author of

The Final Confession of Mabel Stark

(Vintage Canada, 2002), shortlisted for both the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for best first book and the Trillium Book Award;

The Stowaway

(Vintage Canada, 2004), one of the Boston Globe’s top ten fiction titles of 2004;

The Culprits

(Vintage Canada, 2008);

Dr. Brinkley’s Tower

(House of Anansi, 2012), shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for fiction and longlisted for the Giller Prize;

The Man Who Saved Henry Morgan

(House of Anansi, 2015), a finalist for the Trillium Book Award; and

Diego’s Crossing

(Annick Press, 2015), shortlisted for the Arthur Ellis Award. Hough lives in Toronto, ON. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, The Final Confession of Mabel Stark, was a hit! It sold all over the world, and Sam Mendes bought the film rights, with his wife Kate Winslet slated to play Mabel. I figure this is the reason I’m still writing twenty years later – I’m like a gambler who wins his first time out. When that happens, you’re almost sure to become addicted.

The Marriage of Rose Camilleri, meanwhile, is my seventh novel. Yet it’s the first since The Final Confession of Mabel Stark to be voiced by a female narrator. What does this mean? Mmmmm ... I’m not sure, actually. Maybe I finally decided that if it worked once, it can work again.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Before becoming a novelist, I was a full-time magazine journalist for a dozen years or so. The thing is, I never had that much interest in current events, which, it turns out, is a liability for reporters.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m not one of those writers who does a lot of thinking, or make a lot of notes, or writes down ideas for scenes and tapes them to his office walls. Unfortunately, I can’t really come up with anything unless my fingers are moving. So I do lots of drafts. Lots and lots of drafts.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don’t really read many short stories – the occasional one in The New Yorker and that’s about it. Oh no, I’m a novel guy, and that’s what I’m gunning for from the word go.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

It’s a bit of a moot question, since the vast majority of event organizers have figured out that people stay away in droves from readings. What people do like, however, is hearing writers talk. So most of the live gigs involve talking to an audience for twenty minutes about whatever you want to talk about. (Most writers blab away about the new book, with a bit of their process thrown in for good measure.) I get very nervous before hand, but as soon as I get my first laugh I really do enjoy addressing an audience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I was about to leave this question blank when it occurred to me that I do have this little trick. While it’s true that you have to understand your protagonist’s motivation, I think it really helps if you divide that chore into two: at a certain point, I try to understand what my character wants, and what my character subconsciously wants. And I gotta say: if those two desires are the same, then you have yourself a pretty dull character.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

If by a ‘writer’ you mean ‘novelist’ well ... I hate to say it but I don’t think we hold a lot of sway, these days. A case in point: often, at parties or social events, I’ll be asked what I do for a living. When I answer that I’m a novelist, the follow-up question, more often than not, is: “Really? So do you write fiction or non-fiction?” However, if you’re referring to TV writers, it’s the show runners who really have a grip on the world’s imagination. Think of (Mad Men), (Sopranos), (Breaking Bad), or (Silicon Valley and Barry): they’re as influential as film directors were in the 70s.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I welcome the point in which I’m assigned an editor, as it means I don’t have to work alone, any longer, in my lonely little writer’s abyss. I’d say that working with an editor is only difficult when the editor is an idiot, which has never happened with me on a book. But back in my magazine days, it did happen a few times, and I tell you -- when it does you just don’t want to get out of bed.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Early on, an editor read a failed, quasi-autobiographical first novel of mine and said, “If you can’t describe your novel in a single sentence, then you haven’t found your story.” And you know what? It’s true. With The Marriage of Rose Camilleri, that sentence is the following: “An exuberant Maltese woman learns to love her ex-criminal husband during a turbulent, 23-year marriage.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (adult fiction to young adult fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Mmmmm ... I wrote one young adult novel, but only because a publisher approached me with a commissioned idea, and I was like, “wait a minute ... whoa ... hold the phone .... you’ll give me money before I start writing?”

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

There’s something quite self-flagellating about novel writing. I work every morning, and I don’t let myself leave my office until I’ve written a thousand words. I write a lot more than that if I’m having a good day, but on those terrible days, when the ideas just aren’t coming, I still don’t let myself quit until I have a thousand words. Why? There’s so much writing to do with novels – all of those drafts and false starts -- that if you only write when the muse is with you then you will never finish.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I appeal to my pig-headed nature. Even when blocked, I force out those thousand words. Even if I go weeks without writing anything worthwhile, I keep typing. And then, one day, it comes back ....

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

A good question! Despite how I answered question #12, it just occurred to me that, when confronted by a large writing question or obstacle, I’ll go down to the Art Gallery of Ontario and look around. I don’t know why, but something about looking at all those paintings helps me see around corners.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

In no particular order, these are my five favourite novels, based solely on the number of times I’ve read them:

The Thought Gang by Tibor Fischer

Memoir from Ant-Proof Case by Mark Helprin

Gould’s Book of Fish by Richard Flanagan

A Fraction of a Whole by Steve Toltz

The Buddha of Suburbia by Hanif Kureishi.

The question is: have these novels influenced me? All of these writers are a lot more talented than I am, and I’m smart enough to realize that I could never pull off what they pull off, so I don’t even try. So I feel like they haven’t influenced me, though on some level maybe they must have, right?

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

You mean as a writer? I’d like to write a really great horror novel. But in general? I’d like to see a live volcano.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve never not been a writer. I have a good imagination, but not good enough to imagine what else I could’ve been.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

When I was ten, I started writing a detective novel. I can still remember the title: “A Pipeline to Diamonds.” I finished about a page and a half, and then I went outside to play road hockey. I remember being good in net.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

During the lock-down, I discovered three great novels: Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World by Donald Antrim, Wittgenstein Jr. by Lars Iyer, and London Fields by Martin Amis. My favourite covid film, meanwhile, wasn’t a film at all; it was a scabrously funny television series entitled The Great, which chronicles Catherine the Great’s efforts to rid the Russian court of savagery, idiocy and bad government. The chancesthat show takes with its humour....

20 - What are you currently working on?

A novel in which one of the characters is the anarchist Emma Goldman. I’m far along, actually, as the publication of The Marriage of Rose Camilleri was delayed by about a year due to a combination of covid and supply chain disruptions. I’m pleased with it. No, really, I am.

May 28, 2022

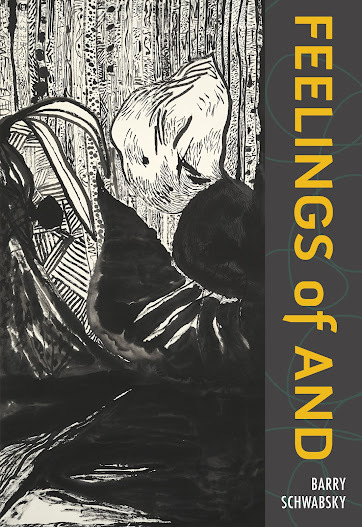

Barry Schwabsky, Feelings of And

The Smell of Burning Trees

Once before running out of breath

matching sky against sky

if your mind is not paranoid these days

you’ve got a big problem

scantily represented in the literature

of bridge and tunnel lyricism

not particularly frightened by my death

—the rest I think you know

a powdered eye

don’t ask me about it now

in an atlas of cold weather

drawn to its inconclusion

From Long Island, New York poet and critic Barry Schwabsky comes the poetry collection

Feelings of And

(New York NY: Black Square Editions, 2022), a collection built as a suite of meditative lyrics that weave through commentaries and explorations around history, theory, culture, humanity and psychology. His lyrics are thoughtful, and straightforward with an easygoing manner, and the ease through which his lines flow offer a clarity across complex ideas. “I had to agree that politics is a higher calling than art.” he offers, to open the poem “Conversation with a Revolutionary.” The short poem (but two sentences long), continues/ends: “But not, I / insisted, a more productive one, since the chances of turning out / to have made a good revolution are even less than those of having / made a good painting.” There is a curious back and forth through his poems, neither showing nor telling but easing, prompting and exploring what he seeks to comprehend, his poems existing as documents of what might otherwise seem quick observations. As the poem “Christmas on Earth, Noon on the Moon” ends: “nibbling at some sugar maple gloom / sweet knowledge saved up or drowned / in the stifled promise of an airless year.” The poems sit as minor miracles, offering an enormous amount in small spaces, from sharp lines to sharp observations, all of which are offered in deceptively-plain but clearly a highly-crafted language, all which can only be rewarded further through repeated readings. “just remember,” he offers, to close the poem “Living Within Your Meanings,” “starlings do nothing in moderation [.]”

From Long Island, New York poet and critic Barry Schwabsky comes the poetry collection

Feelings of And

(New York NY: Black Square Editions, 2022), a collection built as a suite of meditative lyrics that weave through commentaries and explorations around history, theory, culture, humanity and psychology. His lyrics are thoughtful, and straightforward with an easygoing manner, and the ease through which his lines flow offer a clarity across complex ideas. “I had to agree that politics is a higher calling than art.” he offers, to open the poem “Conversation with a Revolutionary.” The short poem (but two sentences long), continues/ends: “But not, I / insisted, a more productive one, since the chances of turning out / to have made a good revolution are even less than those of having / made a good painting.” There is a curious back and forth through his poems, neither showing nor telling but easing, prompting and exploring what he seeks to comprehend, his poems existing as documents of what might otherwise seem quick observations. As the poem “Christmas on Earth, Noon on the Moon” ends: “nibbling at some sugar maple gloom / sweet knowledge saved up or drowned / in the stifled promise of an airless year.” The poems sit as minor miracles, offering an enormous amount in small spaces, from sharp lines to sharp observations, all of which are offered in deceptively-plain but clearly a highly-crafted language, all which can only be rewarded further through repeated readings. “just remember,” he offers, to close the poem “Living Within Your Meanings,” “starlings do nothing in moderation [.]” There is something here reminiscent of the ongoing work of Canadian poet Ken Norris[see my review of his latest here] for the shared aesthetic of the straightforward lyric, offering a poetics of lived experience, although Schwabsky’s is one that offers more in the way of lyric complexity. “We wanted more loveable / gods,” he offers, as part of the opening poem “The Selected Cosmos,” “a blind sky tossed / over distracted misdemeanors. / Or Godzilla, a way of making / radiation visible. But who will tell him / this is poetry?” There is something of the idea that if you wish to communicate a complex thought, offer it through the lens of a poem by Barry Schwabsky.

Polonaise Fantaisie

Strange gestures of musicians. The way a pianist might draw a hand up with resolve, as if to entice some weighty chord to linger in the air just that much longer, or even haul a stray note bodily from the abyss of the keyboard as one would a child that has tumbled into the well. What bothers me is how this useless coaxing sometimes seems to work.