Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 120

July 16, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Katie Welch

Katie Welch writes fiction and teaches music in Kamloops, BC, on the traditional, unceded territory of the Secwepemc people. Her short stories have been published in EVENT Magazine, Prairie Fire, The Antigonish Review, The Temz Review, The Quarantine Review and elsewhere. She was first runner-up in UBCO’s 2019 Short Story Contest. Her debut novel

MAD HONEY

was released in May 2022 by Wolsak and Wynn.

Katie Welch writes fiction and teaches music in Kamloops, BC, on the traditional, unceded territory of the Secwepemc people. Her short stories have been published in EVENT Magazine, Prairie Fire, The Antigonish Review, The Temz Review, The Quarantine Review and elsewhere. She was first runner-up in UBCO’s 2019 Short Story Contest. Her debut novel

MAD HONEY

was released in May 2022 by Wolsak and Wynn. Katie holds a BA in English Literature from the University of Toronto (1990). Her daughters, Olivia and Heather Saya, share her passion for nature and outdoor recreation. Katie loves to cycle, hike and cross-country ski with her husband, Will Stinson, and they are creating a remote home on Cortes Island, in Desolation Sound.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, a self-published novelette, was an impetuous and ill-advised project. It was good practice, but like its musical equivalent, writing practice is best accomplished in private. It was a mistake to do something solo which in fact requires the combined effort of many professionals. Mad Honey, by contrast, is the result of seeking traditional publication and it feels fantastic, polished, the book I wanted to write. I’m deeply grateful for the excellent team at Wolsak and Wynn.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I fell in love with fiction as soon as I could read: escape, exploration, adventure! I told my little sister stories to soothe her after nightmares, and it wasn’t long before I was writing those stories down. These days I’m reading lots of non-fiction, so I’m beginning to have ideas for non-fiction projects. I enjoy and admire poetry but I am not a poet.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

When I have an idea paragraphs flow from me fast, as if I’m running out of time. I amrunning out of time! The first draft is very rough and requires many revisions before it’s ready for beta readers / an editor / submission.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think in terms of novels. I write short stories to hone my craft.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I didn’t expect to like public readings. I was fine with scribbling away anonymously in a cold garret until I keeled over, but to my surprise I discovered that engaging with readers in person is a fun and powerful experience. It’s a delight to meet someone who enjoyed a story that I wrote.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I want to orient my characters in nature. We’re nothing without clean water, butterflies and skunk cabbage; all our modern problems point to the perils of self-congratulations and navel-gazing narcissism. It’s clear that colonial arrogance towards Indigenous people and Indigenous wisdom has gotten us into serious trouble. If humans are going to survive, we have to care deeply about alllife forms on Earth. So are we going to survive? If so, how? I don’t know if these are the current questions; they’re my concerns, things I think about a lot.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers should write honestly and to the best of their ability, full stop. Writers entertain, interpreting the world through their unique lens and incidentally holding up the proverbial mirror. Writing succeeds when it resonates with an audience and uncovers truths readers didn’t know they knew, but this achievement can’t be deliberate. “No matter how humble the spirit it’s offered in, a sermon is an act of aggression,” said Ursula K. LeGuin, answering a question similar to this one.

That said, we write from experience, and writers cannot help but reflect their milieu; I was dismayed in 2021 when many literary magazines refused to consider pandemic pieces. Shout-out here to The Quarantine Review, curated by Jeff Dupuis and Sheeza Sarfraz, a wonderful platform for pandemic-inspired creative work.

Many contemporary ‘larger culture’ arenas involve blurting contentious views in virtual echo chambers. Personally I prefer well-researched, well-reasoned essays to flippant mini-opinions. I appreciate writers who post links to thoughtful work.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

A brisk and unflinching edit is clarifying, inspirational and necessary. A writer needs to be capable of hearing the truth about their work. You can either have the best possible version of your project or preserve your fragile ego. Actually, unless you intend to burn / delete without publishing, you will never spare your ego. Eventually you’ll get feedback, and some of it will be negative, a larger percentage if the editorial process has been resisted. I choose the honest opinions of consummate professionals during development to the disparagements of disappointed readers.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Over the years and in many ways, successful writers have counselled me to (a) be patient and (b) persevere in spite of failures and setbacks: great advice for both writing and life. I find (a) particularly difficult. On the cusp of my debut novel’s publication, I would like to thank everyone who recommended putting my head down and getting back to work.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

For me, short stories are like little practice novels. I resisted them because I wanted to skip straight to novels (impatient!) which in retrospect is like a musician wanting to get directly to an album without writing any songs. Revising and submitting stories keeps me sharp and focused, and there’s quick gratification when one gets picked up by a journal or magazine, but I still prefer the size and depth of a novel.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Coffee at the crack of dawn, start writing while the mind is fresh. I take breaks to cook, clean and exercise, and teach music in the late afternoon / evening.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I allowed decades to elapse without writing which created a kind of creative bottleneck: I have more ideas than I can use before I die. DM me on my deathbed!

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Mud.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above! Inspiration comes from everywhere! I never know what will tweak my imagination, bring up a weird memory and cause nuclear idea-fusion. Mad Honey was sparked in part by a Discover Magazine article about Barbara Shipman, an American mathematician and quantum physicist. I endeavour, with varying degrees of success, to bring my passion for nature to the page.

Music is a strong influence. During revision I scan passages for rhythm. I try to relax my jaw and get into a flow-state, a music performance technique. I recently read an adult novel consisting almost exclusively of short, one-clause sentences. Statement after statement, repetitive as hammer strikes. I was reminded of trance music. Not my cup of tea but the book is very popular; as with music, literary taste is infinitely wide and varied.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Ursula K. LeGuin for writing instruction and philosophy: Steering The Craft and Words Are My Matter. I also love her fiction. It’s essential that I admire what I’m reading while working on a manuscript so I often re-read favourites, to name a few: Washington Black by Esi Edugyan; Do Not Say We Have Nothingby Madeleine Thien; Donna Tartt’s novels; The White Bone by Barbara Gowdy; All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews; The Magicians series by Lev Grossman.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Keep bees.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I teach music and find it enormously gratifying, so I would probably teach music full time. I planted trees and love working outside, so maybe gardening or farming?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was meant to write. Writing is my vocation.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Ian Williams’ Reproduction blew my mind. I loved the gorgeous, precise language and surprising structure / grammar. Bonus, it’s also a gripping page-turner! I raced through the first read and have enjoyed it twice more at a leisurely pace.

Films: Denis Villeneuve’s Dune is beautiful, riveting and weirdly relevant. Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up, a smart satire of our planetary predicament, has an excellent script and some fabulous performances. Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, released three years ago, is lodged in my head and heart.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I recently completed a short story collection, thanks to the generosity of a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts. I’m working on a second novel. A memoir/biography including stories from Ottawa and Fisher Park is in the planning stages.

July 15, 2022

Noah Eli Gordon (1975-July 10, 2022)

Like so many, I’m stunned to hear of the death of American poet Noah Eli Gordon, author of over a dozen poetry books over the past two decades, including

The Frequencies

(Tougher Disguises, 2003),

The Area of Sound Called The Subtone

(Ahsahta Press 2004), INBOX (BlazeVOX, 2006),

Figures for a Darkroom Voice

(with Joshua Marie Wilkinson; Tarpaulin Sky, 2007),

A Fiddle Pulled from the Throat of a Sparrow

(New Issues, 2007),

Novel Pictorial Noise

(Harper Perennial, 2007),

The Source

(Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here],

The Year of the Rooster

(Ahsahta Press, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2015) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous chapbooks. He was a prolific reviewer and critic (I think he even reviewed the Kate Greenstreet above/ground press chapbook for Rain Taxi), the editor/publisher of and most likely a whole slew of other things I either can’t recall or don’t know, as well as a singular presence on the literary scene. His was stoic and solid confidence across uncertain terrain, composing thoughtful poems that went to the most unexpected places, and rocked the foundations of what made poems possible, and confused those who wished for more straightforward or flashy language.

Like so many, I’m stunned to hear of the death of American poet Noah Eli Gordon, author of over a dozen poetry books over the past two decades, including

The Frequencies

(Tougher Disguises, 2003),

The Area of Sound Called The Subtone

(Ahsahta Press 2004), INBOX (BlazeVOX, 2006),

Figures for a Darkroom Voice

(with Joshua Marie Wilkinson; Tarpaulin Sky, 2007),

A Fiddle Pulled from the Throat of a Sparrow

(New Issues, 2007),

Novel Pictorial Noise

(Harper Perennial, 2007),

The Source

(Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here],

The Year of the Rooster

(Ahsahta Press, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2015) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous chapbooks. He was a prolific reviewer and critic (I think he even reviewed the Kate Greenstreet above/ground press chapbook for Rain Taxi), the editor/publisher of and most likely a whole slew of other things I either can’t recall or don’t know, as well as a singular presence on the literary scene. His was stoic and solid confidence across uncertain terrain, composing thoughtful poems that went to the most unexpected places, and rocked the foundations of what made poems possible, and confused those who wished for more straightforward or flashy language. I first encountered a selection of Gordon’s work (I can’t recall if I caught a stray poem or two in a journal, prior to this) through the since-late Peter Ganick being good enough to mail me, circa January 2006, a copy of a chapbook of Gordon’s he’d produced, twenty ruptured paragraphs from a perfectly functional book [see my review of such here]. It was Gordon’s subsequent chapbook, winner of the 2007-2008 Pavement Saw Press Chapbook Award, Acoustic Experience (Pavement Saw Press, 2008) [see my review of such here], that really struck my attention, and prompted me to take his work far more seriously. The chapbook included a piece that stayed with me for years, the tone and structure of which I attempted to replicate repeatedly, without luck:

An Old Poem Embedded In A Final Thought on the Airplane

About five years ago, I wrote a short poem called "Yesterday I Named a Dead Bird Rebecca". The title came to me while in Florida visiting family. Going for a short walk, I passed the carcass of a crow swarming with small flies. There was something so repugnant about this particular dead animal that, although oddly aware of its lack of any sort of odor, I was, nonetheless, overcome by a strong, debilitating nausea, one which I suspect arose simply from the smell I imagined the bird to have. The poem reads:

were a defused heart

wintering the clock

time kept

by counting birds

I'd call flight

a half-belief in air

a venomous lack

when the ticking is less so

What could be more obvious than that this poem transposes its prepositional way of understanding gravity into the structure of its own identity? Something that lies beyond its lone sentence speaks to me now as the kind of nostalgia one feels upon watching an airplane pass overhead. It means making distance disappear.

Gordon and I interacted occasionally over the years, whether his ’12 or 20 questions’ interview in 2007, or through above/ground producing a chapbook of his (with accompanying artwork by Sommer Browning) a few years later. I admired the seriousness of his approach through lyric play, including his experiments through repetition, composing entire manuscripts of poems that each held the same title; it’s a bold experiment if it doesn’t work, and through Gordon, it provided some incredible possibilities. If you don’t know his work, I would recommend seeking it out, especially some of those last few titles. His absence will leave a considerable space, and I am sad for it, especially knowing he leaves a young daughter. I can’t imagine much worse.

There is currently a space for donations to offer support Sommer Browning and their daughter Georgia. Please help if you are able.

July 14, 2022

Krystal Languell, Systems Thinking With Flowers

BASEBALL POEM WRITTEN BY A WOMAN

In St Louis tonight, the shortstop tips over the left

field wall, his left arm extended to break his fall lands

in a woman’s nacho cheese and as he slips his right

leg flies up to kick a plastic tray of nachos out of a fat

white man’s hand. The man drops his jaw. He licks

his wrist. Workers kick dirt over the man’s cheese—

maybe for safety, for aesthetics, lack of a broom—

and the trainer comes out to sponge his hand. One

of those Renaissance paintings. The open mouths.

The athlete’s body linking the spectators and their

nacho cheeses never stop moving.

The fourth-full length poetry title by Chicago poet Krystal Languell, following Callthe Catastrophists (BlazeVOX, 2011), Gray Market (1913 Press, 2016) and Quite Apart (University of Akron Press, 2019), is Systems Thinking With Flowers (Portland OR: fonograf editions, 2022). Systems Thinking With Flowers, winner of the 2019 Fonograf Editions Open Genre Book Prize, as selected by Rae Armantrout, is a collection that opens with a section of baseball poems in the mode of Jack Spicer (something followed since by the likes of George Bowering and Kevin Varrone, among others), as the opening poem, “PROPRIOCEPTION,” begins:

like phenomena, the importance of

of baseball to my marriage

can best be articulated

as extra-sensory perception

unexplained response

unidentified stimuli

Languell writes baseball, “the thinking person’s game,” very specifically, while simultaneously utilizing the subject as a way to write through and about far beyond the game. “The celebratory fireworks are suspended / when the stadium opens to dogs.” she writes, as part of “BOO CLEVELAND BOO,” “My friend’s child put down her hot dog / and a golden retriever licked it. // This freed her up to focus attention on / cotton candy, showing us her tongue.” Throughout, Languell’s syntax and rhythms are bulletproof, composing lines that any bird would trust to light upon; the ways in which she writes poems propelled and set by and through rhythm. She writes the nuance of baseball, and how language ripples, providing linkages to deeper things, something Spicer knew full well, but never explored, at least so thoroughly. As the poem ‘HOW BORING!” offers: “I know obscurity is boring as replays / Necessary fabric to tie the room together [.]”

Languell writes baseball, “the thinking person’s game,” very specifically, while simultaneously utilizing the subject as a way to write through and about far beyond the game. “The celebratory fireworks are suspended / when the stadium opens to dogs.” she writes, as part of “BOO CLEVELAND BOO,” “My friend’s child put down her hot dog / and a golden retriever licked it. // This freed her up to focus attention on / cotton candy, showing us her tongue.” Throughout, Languell’s syntax and rhythms are bulletproof, composing lines that any bird would trust to light upon; the ways in which she writes poems propelled and set by and through rhythm. She writes the nuance of baseball, and how language ripples, providing linkages to deeper things, something Spicer knew full well, but never explored, at least so thoroughly. As the poem ‘HOW BORING!” offers: “I know obscurity is boring as replays / Necessary fabric to tie the room together [.]” Set in two sections of short lyrics, the second section of the collection moves away from baseball into observational postcards, furthering her sharp examination of language and perception, offering a narrative ease but an exactness that cuts down to bone. “Pull a loose hair out of my bra,” she writes, to open the poem “PARDON MY FRIEND, BUT YOU’RE AN ASSHOLE,” “What do I have to show for it / A better set of pens might be the perfect thing / she was grieving on a yacht on Instagram / That doesn’t concern anyone you’d know [.]” As Rae Armantrout offers as part of her brief foreword to the collection: “There is a provocative tension here and elsewhere in the book between the precise, science-laced language employed and the shifty phenomena it seeks to describe and understand.” This is a collection with a subtlety that rewards, especially upon rereading, thanks in part to Languell’s precision, and the ability to make impossible turns. Armantrout continues: “Every word of that strikes me as just right. Languell identifies not with the flag, but with the loneliness of its flap. It makes me think about being simultaneously at home and in exile.”

July 13, 2022

Greg Kerr (June 28, 1969 – June 28, 2022)

I’m not sure what happened yet, but Ottawa cartoonist and musician Greg Kerr died at the end of June, and on his fifty-third birthday, no less. I don’t want to believe it.

I first encountered Greg’s work through his self-published BUNCHA STORIESchapbook-sized comics (almost in a Chester Brown Yummy Fur vein, offering separate issues of stand-alone but interconnected stories) at Crosstown Traffic in the Glebe, these small roughly-made first-person comics of drinking and other ridiculous adventures. I was immediately struck by the energy of Greg’s work, and his ability to tell stories. The comics were rough, but he understood narrative, and how to pace out the action. He was really good at telling stories, whether through comics or in-person. During that period, I knew an editor at Carleton University’s weekly newspaper, The Charlatan, who was letting me do whatever I wanted in their centre spread, so managed to find a contact with Greg and meet up for an interview (which allowed me to meet him in person for the first time), which can be found online here. He did give me the original of his illustration of me interviewing him, but unfortunately, that, along with my personal copies of the piece, disappeared after a particular move. Not long after that, he even did a back cover illustration for one of my chapbooks.

Most of my encounters with Greg were on the streets of Ottawa’s Centretown, throughout the 1990s and into the aughts, encountering him randomly on the street or at the original Royal Oak Pub on Bank Street, just by MacLaren. My interactions with Greg were always positive, always random, always a bit ridiculous. On the surface he seemed quiet, almost shy, his comics allowing for a more outgoing, gregarious (so to speak) self. A personal favourite was a single-panel comic displaying, basically, all the things he realized he now owned after a particularly rowdy evening of drink, a list that included “a chair from McDonalds,” a traffic barricade light and other completely random items. He later drew me a couple of times, including an “author photo” included on the cover of my first full-length poetry collection with Broken Jaw Press, back in spring 1998. At one point, during the stretch of years I wrote daily at a Dunkin’ Donuts at Bank and Gloucester (where a Tim Horton’s now sits), he wandered by and displayed a pair of hugely oversized trousers he referred to as “Czechoslovakian winter pants” (large enough that four or five of us could have comfortably fit simultaneously within), purchased while drunk from Irving Rivers that they wouldn’t allow him to return. At another point, he wandered by with a Yogi Bear lamp sans lampshade that he gave me, although he paused to remove and keep the light bulb.

Most of my encounters with Greg were on the streets of Ottawa’s Centretown, throughout the 1990s and into the aughts, encountering him randomly on the street or at the original Royal Oak Pub on Bank Street, just by MacLaren. My interactions with Greg were always positive, always random, always a bit ridiculous. On the surface he seemed quiet, almost shy, his comics allowing for a more outgoing, gregarious (so to speak) self. A personal favourite was a single-panel comic displaying, basically, all the things he realized he now owned after a particularly rowdy evening of drink, a list that included “a chair from McDonalds,” a traffic barricade light and other completely random items. He later drew me a couple of times, including an “author photo” included on the cover of my first full-length poetry collection with Broken Jaw Press, back in spring 1998. At one point, during the stretch of years I wrote daily at a Dunkin’ Donuts at Bank and Gloucester (where a Tim Horton’s now sits), he wandered by and displayed a pair of hugely oversized trousers he referred to as “Czechoslovakian winter pants” (large enough that four or five of us could have comfortably fit simultaneously within), purchased while drunk from Irving Rivers that they wouldn’t allow him to return. At another point, he wandered by with a Yogi Bear lamp sans lampshade that he gave me, although he paused to remove and keep the light bulb. I kept this lamp for years, until I realized it required an electrical repair I’d never get around to. When I mentioned the lamp to Greg again, he had no recollection of any of it, and thought him taking the bulb back was confusing, hilariously funny, even mean. He laughed: Why did I take the bulb?

I spent the latter half of the 1990s most late afternoons and evenings at that particular Oak, usually working on fiction, and hanging around with whoever might be around. Greg would go in to socialize, and read the newspaper. We spent hours upon hours together. He once did a comic depicting a full day spent at the Royal Oak where he accidentally spent his entire paycheque, writing our pal Sunny further into the story and writing me out—I had been part of the first eleven hours of his twelve-hour misadventure, as he purchased round upon round of drinks for the two of us, finally switching to gin-and-tonics around 10pm. Because, as he said at the time, “beer takes; gin and tonic gives.” He eventually cut me off because I wasn’t drinking fast enough. Later, upon seeing the comic, I asked why he’d edited me out and he laughed, saying that he figured he’d drawn me enough.

Greg knew more trivia about WKRP in Cincinnati (the greatest television program of all time) than anyone else, and even produced a couple of comics around the show. Greg Kerr was a Centretown standard, even when he ended up moving to Gatineau. Do you remember rhat period of time when he’d be without a phone because he’d refuse to pay the phone bill and get disconnected? Eventually, Bell would convince him to reconnect, and they’d be off again, and he'd be cut off again after another period of months before they realized he had no intention of giving them any money. This went on for years, a cycle that seemed to be a strange kind of game that he delighted in, and Bell Canada never quite picked up on. Over the years, Greg performed in numerous bands, and worked in a restaurant kitchen or two (where the head chef would put on CFRA Talk Radio’s right-wing provocateur Lowell Green, which prompted Greg to fume every morning at work).

During the period he was part of the band The Deadbeat Dads, they were an episode’s guest-band on The Tom Green Show (during Tom’s Rogers Ottawa days), and started an off-camera fight during taping. If you watch that particular episode, you can hear a scuffle, as Tom turns from the camera and looks to his right. Apparently, after that, the floor director would warn bands not to cause problems during taping, thanks to their scuffle. Apparently, as Greg claimed later on, he just saw bandmate Scott Fairchild’s “big ugly red head” in front of him on stage, “and just had to hit it” with his bass. And that was that.

Greg made comics. I even produced an above/ground press title at one point, Drunkboy Stories (1997), around the time I was publishing his comics regularly in my journal Missing Jacket (the same comics he ended up re-selling, years later, to the Ottawa X-Press, actually). He was ridiculous and extremely fucking talented, without a speck of malice beyond a kind of impish impulse to cause trouble. He was curious, and I always wondered why he didn’t push to continue his comics; a kind of ambition that perhaps conflicted with his interests in doing other things, whether playing music or hanging out with friends or simply not worrying about any of that stuff. He was a good dude, and I will miss him.

A memorial for Greg Kerr will be held on SATURDAY AUGUST 6th, 2022 (3pm to 7pm) at The Dominion Tavern, 33 York Street, Ottawa. Mark your calendars.

July 12, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ellie Sawatzky

Ellie Sawatzky

(@elliesawatzky) grew up in Kenora, Ontario. A past winner of CV2’s Foster Poetry Prize, runner up for the Thomas Morton Memorial Prize, and a finalist for the 2019 Bronwen Wallace Award, her work has been published widely in literary magazines across North America.

None of This Belongs to Me

is her debut full-length poetry collection, published by Nightwood Editions in October 2021. She is currently an editor for FriesenPress, a member of the Growing Room Collective, and curator of the Instagram account IMPROMPTU (@impromptuprompts), a hub for prompts and literary inspiration. She lives in Vancouver with her partner and a cat named Camus.

Ellie Sawatzky

(@elliesawatzky) grew up in Kenora, Ontario. A past winner of CV2’s Foster Poetry Prize, runner up for the Thomas Morton Memorial Prize, and a finalist for the 2019 Bronwen Wallace Award, her work has been published widely in literary magazines across North America.

None of This Belongs to Me

is her debut full-length poetry collection, published by Nightwood Editions in October 2021. She is currently an editor for FriesenPress, a member of the Growing Room Collective, and curator of the Instagram account IMPROMPTU (@impromptuprompts), a hub for prompts and literary inspiration. She lives in Vancouver with her partner and a cat named Camus. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first poetry collection just came out in October 2021, so it still feels so new. It’s been incredibly validating and fulfilling. It’s been wonderful to be able to share it and celebrate it and feel proud of it. It’s wonderful to receive emails from strangers who’ve read and resonated with my poems. And in another way it’s been a humbling reminder that as a writer, you just have to keep writing. On to the next project. I spent ten years writing the poems for None of This Belongs to Me, so there was a feeling, in launching it, of throwing the baby bird out of the nest. Now it’s out there; it’s flying away from me, living its own life without me, and I have to focus on the next thing.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I would argue that I came to fiction first. I drew stories before I knew how to read and write. I had this great teacher in Grade 1, Mrs. Delamere, who helped her students “publish” books. She transcribed my stories, I drew the pictures, and then she “bound” them into books. She included an “About the Author” page, and she even had a “Unicorn Publishing” stamp. It was very cute. I would say that’s when I first knew I wanted to be an author.

Then I came to poetry as an angsty teen, as so many of us do, and it stuck. No matter what genre I’m writing, though, my goal is often the same: to tell a story. A lot of my poems are narrative. My approach to writing a poem is much the same as my approach to writing a short story. I start with a landscape or character or image, and the story unfolds from there.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s slooooooowwwwwww. So slow. It’s almost always slow. Poems can sometimes come quickly, but it’s rare. There are a couple of poems in my book that I recall writing relatively quickly (“Finlandia”, “Sun Valley Lodge”, “The Missed Connections Ad Writes Itself”). But I’m very methodical, and I edit as I go, so that slows me down. Often first drafts appear looking very close to their final shape.

I’m currently working on a novel (eep). It’s an idea I started pondering a year ago, and I only actually started writing words on a page in January of this year. But pondering is an important part of my process; I feel like I started writing words on the page when I was ready, when I had a stronger sense of intention, of the story I wanted to tell.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

It depends on what I’m writing. My poetry collection is a cumulation of poems I’ve written over ten years. Eventually I had enough individual poems that I started to think about putting them together in one manuscript. But I think the moment I first felt that my handfuls of poems could be a book was when a friend of mine, Joelle Barron, made a suggestion for the title, None of This Belongs to Me. Which is a line lifted from one of the poems in my book that I wrote about my experiences working as a nanny over the last decade. The moment that Joelle suggested that title to me was the moment that I started to see my poems—which previously had felt like very disparate scraps of my experience—forming a narrative and becoming something like a book, and that inspired me to write more.

I wrote a short story collection for my MFA thesis, and that was a very similar kind of experience, of gathering together individual stories. But writing a novel, the kind of writing I’m doing now, is, of course, completely different. Thus far, it’s taken more planning, more forethought, more consideration of its trajectory as a book than any of my previous projects.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. I have the stage fright, like anyone, but it gets easier every time I do it, and I love interacting with an audience, gauging how my work is received, what people find funny or profound. Or maybe it falls flat—that happens too. I find it changes my relationship with the piece; it gives me a better understanding of how it’s working.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The poems in None of This Belongs to Me ask some big questions that I feel are pertinent to the current cultural moment. How do we heal? How do we move forward in blind faith? How do we give and receive care? How do we find compassion for each other when our perspectives are so different? In what ways do we both nurture and harm each other and our environment? What is inherited from previous generations? How have I become the woman I am today, based on what I’ve observed, learned, inherited from the women in my lineage? These are all questions I try to answer in my work. There’s a lot of crossover into my fiction as well.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

For me, both reading and writing are processes of making sense of the world around me, synthesizing the information of the world, which is done through feeling. I think it’s all about feeling. Both reading and writing are practices in going inwards, feeling into oneself, seeking the truth, or truths, of our experiences.

But on a more superficial level, I think the role of the writer should be to entertain. To make people laugh. To tell a good story. To take readers on an adventure. To provide an opportunity for escape.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I was once given some great advice by Ken Babstock. He was my poetry instructor at UBC at the time. I had written a poem (“This Little Girl Goes to Burning Man”) that was inspired, in its form, by one of his poems (“Carrying Someone Else’s Infant Past a Cow in a Field Near Marmora, Ont.). Rob Taylor recently did me a solid and came up with a name for this form: “shrinking quatrains.” In a discussion about my poem, Ken told me that if I found that a particular form or shape really worked for me—i.e. shrinking quatrains—to write more poems in that shape. Which I did. I wrote “Crystals” after that, and then “Kenora, Unorganized.” I’m often concerned about hitting the same note too many times in my writing, but that piece of advice from Ken encouraged me to work within structures that feel good for me.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s not easy for me to write in more than one genre in a period of time. I had to, during my UBC Creative Writing days, which was a good challenge for me. But I tend to be in either a fiction-writing phase or a poetry-writing phase. My last poetry-writing phase lasted five years, and now I’m back to writing fiction.

In poetry, often I’m confronting the hard truths of my life, which can be very appealing or very unappealing, depending on where I’m at. Fiction, right now, feels like a bit of an escape into someone else’s life, into my characters’ struggles and triumphs. It also feels like a bit of an escape into a pandemic-free world, which is very, very appealing at the moment.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Routines are good for me, but I’ve struggled in the past to keep one. I work from home as an editor for FriesenPress, so I get to make my own schedule. In January I started a new routine: I wake up and write. Sometimes I write in bed. Sometimes I write at my desk. Sometimes I write for one hour, sometimes four or five. When I’m done writing, I take a break and transition—usually by doing yoga or going for a walk. Then I get into my FriesenPress work, and I edit until dinnertime. I recently got a BC Arts Council grant for my novel, so I’m going to be taking a little sabbatical from FriesenPress and spend full days writing, which I’m very much looking forward to.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading a good book or a good poem often does the trick. Or I free write or write from prompts. I love prompt writing. I curate an Instagram account, IMPROMPTU (@impromptuprompts), a hub for literary inspiration and writing prompts. I find, also, that talking about the project with a writer friend helps me to work through whatever it is that’s stalling me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Wild rose.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, all of the above. Anything and everything can inspire my work. My poem “Chihuly’s Mille Fiori” was inspired by the glass sculptor Chihuly’s exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Montreal in 2013. I have another poem “Spotify My Body” that’s a cento, a poem made up entirely of song titles. “The Falling Man” came to me while I was scrolling through Google images randomly, looking at pictures of “The Falling Man” from 9/11 for no particular reason (as one does). The idea for my novel came to me while having a beach fire in Robert’s Creek on the Sunshine Coast, looking through the lit windows of the cabin behind me.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I did my BFA and MFA at UBC. The friends, colleagues, teachers, and mentors I met during that time have been boundlessly important to my life and my work. This includes—but is not limited to—Rhea Tregebov, Nancy Lee, and Keith Maillard. Also Erin Kirsh, Joelle Barron, Erin Stainsby, Cara Kauhane, Reece Cochrane, Kyla Jamieson, Alessandra Naccarato, and Selina Boan.

I also met my partner, Adrick Brock, in the Creative Writing program (though we didn’t start dating until many years later). We’re both currently working on novels, and we’re at similar stages. A few weeks back, we workshopped each other’s outlines. It’s wonderful to be able to talk through our projects and to share new work. The creative energy in our house is very motivating. There’s also a light implication of competition. He’s a Virgo, type A, and very diligent, whereas I’m a Gemini, often hopelessly adrift, but his focus inspires me to be more focused.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

This is not writing-related, but I’d like to buy a house in Greece.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think I would have been a musician if writing hadn’t taken me by the hand. I’m not sure what kind of musician. A fiddler in a bluegrass band. Or a violinist in a symphony. Or a trombonist in a folk/cabaret fusion group.

Alternatively, I would have become something more practical and lucrative, like a doctor or a lawyer. To fund my international house-buying aspirations.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wish I knew. I feel like I didn’t have a choice. Like I said, writing took me by the hand.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently read Inside by Alix Ohlinand got totally swept up in it.

A film I enjoyed recently was Tick, Tick .. . Boom, about Jonathan Larson, creator of Rent. I thought it was so clever: a musical inside a movie about a guy trying to write a musical. I loved the overall messaging about youth and the experience of the writer, the pressure that writers and put on themselves, and the value of art. This notion that as a writer, you just keep throwing things against a wall, hoping something sticks. You just have to keep writing.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m currently writing a novel about a young, Mennonite woman—raised in a conservative family on a goat farm in northwestern Ontario—who secretly begins an ASMR YouTube channel. One of her patrons, a man named Jared, becomes her long-distance boyfriend. The discovery of her alter-ego by her parents incites flight from her family home to Jared’s beachfront property on the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia. That’s all I’ll say.

July 11, 2022

retreat report : home,

I was calling it such, but it was more complicated than that (as things so often are). Ridiculously early on Saturday, July 2nd, Christine and her mother took our young ladies through two flights to Winnipeg, leaving directly that morning from mother-in-law’s Ottawa residence, Christine and the girls having left ours the evening prior (that seemed more efficient, they decided). Christine’s 94-year-old Oma lives in Winnipeg, as do mother-in-law’s two sisters, none of whom had met Aoife yet, and had only met Rose once before, when we made a similar trip with baby Rose. They spent four days running around Winnipeg visiting various friends and family, and even managed a trip to the Winnipeg Zoo (which always reminds me of the poem by Robert Kroetsch), as well as various other excursions (all safely masked, of course). I received multiple daily updates.

I was calling it such, but it was more complicated than that (as things so often are). Ridiculously early on Saturday, July 2nd, Christine and her mother took our young ladies through two flights to Winnipeg, leaving directly that morning from mother-in-law’s Ottawa residence, Christine and the girls having left ours the evening prior (that seemed more efficient, they decided). Christine’s 94-year-old Oma lives in Winnipeg, as do mother-in-law’s two sisters, none of whom had met Aoife yet, and had only met Rose once before, when we made a similar trip with baby Rose. They spent four days running around Winnipeg visiting various friends and family, and even managed a trip to the Winnipeg Zoo (which always reminds me of the poem by Robert Kroetsch), as well as various other excursions (all safely masked, of course). I received multiple daily updates. All of this left me solo at home (with our dear boy, Lemonade the cat, naturally) from Friday evening until late Tuesday afternoon, which I’d planned to spend returning back with full force into working on that novel I started back in summer 2020 (as well as watching various television things that Christine hates); remember that? I don’t even think I’d looked at the novel since last fall, having focused instead on reviews and reviews and poems and poems and poems. I’d spent the month-plus prior to their first Covid-era jaunt pushing myself to complete and post as many reviews as possible for the blog, thinking I could carve a path of a couple of weeks to simply work on prose without distraction (beyond, say, our wee ridiculous children, of course). Was such a thing possible?

A home-based retreat. Well, retreat doesn’t presume going away. Retreat means to step away, as I’m sure you know. To withdraw. I didn’t need to head to Banff or Sage Hill. Just a few days at the pub would have been more than enough, honestly.

Of course, once they left, it sparked my simultaneous and inevitable plans to deep-clean the house, and put together multiple above/ground press mailings, folding and stapling as much material as possible. Does this all count as writing? And my first evening solo was spent in Kanata at my brother Darren’s house, celebrating his mother’s (my birth mother’s) birthday (this was only the second time I’d seen her in person). It was a grand evening, that.

I did manage two different writing-related outings of pub afternoons, pushing to return to the space of the thinking of the novel, including one at my favourite, The Carleton Tavern. I also spent an outdoor patio hour at the most god-awful sportsbar closer to home (for the sake of time I didn’t wish to travel further) which made do, I suppose, but geez. Once Christine and the young ladies were home, I did manage a second afternoon at The Carleton, eventually pushing at least two further drafts through the process. Might this be the year I finally manage to complete this and start sending it out?

If I can get enough drafts furthered, I might even post another excerpt (there are a few earlier excerpts posted here and here and here and here), but I’m not quite there yet.

And beyond that, might I ever return to that novel I started on New Year’s Eve 2007, “Don Quixote”? I still consider that project in-progress, despite not having looked at it in years. I’ll get there, someday. Once this project is out of the way, perhaps I can even try.

July 10, 2022

Victoria Mbabazi, FLIP

PERFECT IS A FALSE SPACE

I’m no longer complacent

I don’t erase or peel layers

my skin will callous fuck

Becoming invisible

perfection is a cracked

mirror I fell in

love with myself just being

in me I didn’t lose myself in us

I wont lose myself

in loss I can’t lose

Self-described in their bio as “their second and third chapbook” is Brooklyn-based poet Victoria Mbabazi’s full-length

FLIP

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book, 2022), following on the heels of their chapbook debut,

chapbook

(Toronto ON: Anstruther Press, 2021). Produced as a flip-book, “SHE DOESN’T COME BACK” and “SEND MY LOVE TO IVY,” the poems in FLIP exist as a series of self-contained monologues, performative and theatrical gestures that sweep up against hesitation and pause at breakneck speed, writing sex, Biblical characters, pop culture and politics, queerness and blackness. “I don’t have it in me to be polite all the time a phone service wants me to / talk about mental illness as a thing to overcome but let me melt into it,” they write, as part of “FEMME FATALE,” “when a bitch hurts me I do not wish her well let me be pre and post / traumatic I know you find me stressful you hate perfection even its illusion [.]” There is a rush to their lyric narratives, offering breathless stretches, hard stops and song lists. They write of dreams, and sun, gender, sex and heat. Or, as the poem “REFRIGERATOR WOMAN” begins: “I don’t have to be a woman to be treated like one you like me the way you / know me by your side a frame for portrait your night in day I’m the sun / spinning round the earth you are happy for me as long as I keep you warm / if the heat is bearable [.]”

Self-described in their bio as “their second and third chapbook” is Brooklyn-based poet Victoria Mbabazi’s full-length

FLIP

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book, 2022), following on the heels of their chapbook debut,

chapbook

(Toronto ON: Anstruther Press, 2021). Produced as a flip-book, “SHE DOESN’T COME BACK” and “SEND MY LOVE TO IVY,” the poems in FLIP exist as a series of self-contained monologues, performative and theatrical gestures that sweep up against hesitation and pause at breakneck speed, writing sex, Biblical characters, pop culture and politics, queerness and blackness. “I don’t have it in me to be polite all the time a phone service wants me to / talk about mental illness as a thing to overcome but let me melt into it,” they write, as part of “FEMME FATALE,” “when a bitch hurts me I do not wish her well let me be pre and post / traumatic I know you find me stressful you hate perfection even its illusion [.]” There is a rush to their lyric narratives, offering breathless stretches, hard stops and song lists. They write of dreams, and sun, gender, sex and heat. Or, as the poem “REFRIGERATOR WOMAN” begins: “I don’t have to be a woman to be treated like one you like me the way you / know me by your side a frame for portrait your night in day I’m the sun / spinning round the earth you are happy for me as long as I keep you warm / if the heat is bearable [.]” One element of their work that truly strikes is the ways in which Mbabazi writes poem-endings that deliberately and deliciously refuse narrative closure or the full stop while simultaneously ending with the full force of the lyric; endings not as conclusion but points to pool one’s thinking about the distances that both reader and the poem have travelled to get there. The poems in FLIPare explosive, confident and exploratory, insisting on presence as much as possibility, offering hope and heartbreak, simultaneously being and searching and performing. Or, as the poem “MY GENDER IS WHATEVER SONG IS PLAYING,” begins: “It’s electric guitar with a solo that’s mostly distortion it’s being sad in / major chords it’s the smell of the bar where the local bands play it’s break / ups in the summer time like I’m not a girl [.]”

July 9, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Larry Pike

Larry Pike’s

debut collection of poetry,

Even in the Slums of Providence

, was published by Finishing Line Press in October 2021. His poetry and fiction has appeared The Louisville Review, Seminary Ridge Review, Cæsura, Exposition Review, Cadenza, Capsule Stories, Jelly Bucket, several anthologies, and other publications. His play Beating the Varsity was the “Kentucky Voices” production at Horse Cave (Ky.) Theatre in 2000, and it was published in World Premieres from Horse Cave Theatre (Motes Books, 2009); two other plays have received staged readings. He is a graduate of Mars Hill College (B.A., English) and Purdue University (M.A., communication). A retired human resources manager, he worked for the same company for over forty-two years. He lives with his wife, Carol, in Glasgow, Kentucky.

Larry Pike’s

debut collection of poetry,

Even in the Slums of Providence

, was published by Finishing Line Press in October 2021. His poetry and fiction has appeared The Louisville Review, Seminary Ridge Review, Cæsura, Exposition Review, Cadenza, Capsule Stories, Jelly Bucket, several anthologies, and other publications. His play Beating the Varsity was the “Kentucky Voices” production at Horse Cave (Ky.) Theatre in 2000, and it was published in World Premieres from Horse Cave Theatre (Motes Books, 2009); two other plays have received staged readings. He is a graduate of Mars Hill College (B.A., English) and Purdue University (M.A., communication). A retired human resources manager, he worked for the same company for over forty-two years. He lives with his wife, Carol, in Glasgow, Kentucky.1 - How did your first book change your life? Since it is my only as well as my first book, it was very exciting, and the excitement repeated itself in several stages. I was stunned when I was notified that Finishing Line Press wanted to publish Even in the Slums of Providence. Then, there was a giddy feeling when I received the cover design and first galley proofs. I was out of town when books arrived at my home; I had a friend open the box and take a few pictures and email them to me. Over the next several days, I would view the photos every hour or so, it seemed, just to make sure they were real. How does your most recent work compare to your previous? I’ve never focused on one theme or topic, so I don’t get a sense of dramatic changes over time. I think my work has gotten sharper, more polished, but that may just be my view. How does it feel different? My confidence in what I’m trying to achieve has increased. I believe I’m more ambitious in constructing a piece.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? A friend in high school, Susan Webster Vallance, encouraged me to write a poem. I don’t recall why she did it or what the specific outcome was, but it’s all her fault.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? If I’m intrigued or challenged by a subject, “starting” doesn’t take long. Developing momentum with a piece might. Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? I generally go through a lot of drafts, but the changes from one to another often are minor, so first and final drafts are clearly related.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? With an image or a discrete experience, something that demands to be considered. Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? Since the poems in Even in the Slums of Providence were written over a period of fifty years, I can’t say I was working on a “book” from the beginning.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? I really enjoy doing readings. Poems are visual, but they need to be heard too. The process of thinking about how to deliver or perform a poem informs what it means to me and how an audience might understand or interpret it.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? I don’t think so. I write about what grabs my attention in the moment. It could be a small thing. What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? In the larger sense, I’m not trying to answer any questions or make any statements, other than those that might be prompted by what caused me to write the piece. If I encounter some little truth in a subject that interests me, I’ll do my best to address it. What do you even think the current questions are? There are lots of important questions now: equality, fairness, faith, the pursuit of peace, and many more. I’m not qualified to issue pronouncements on them, but maybe I have something to say about some aspects of them.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Individual writers have different roles. Some teach or persuade. Others entertain. Some report, or perform other functions. The lines among roles blur, overlap, change all the time. Does s/he even have one? I think to be true to how he or she sees his or her calling. What do you think the role of the writer should be? Use his or her talent and inspiration to do the best work he or she can do, whatever it is.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? The occasions when I’ve worked with an editor have benefited my work, usually a great deal. I think an editor’s interests and mine are the same—to produce the best piece possible. I try to listen and not be defensive.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? Show up, do the best you can, which I learned from my parents. “Stay in the room,” which I learned from Ron Carlson.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to plays)? What do you see as the appeal? Easy wouldn’t be the best word. I am primarily a poet, but I have written fiction and three plays. In my experience, some subjects or ideas seem better suited to one genre or another, or they evolve that way. I try to be open to where the piece wants to go.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? Unlike many writers I admire, I don’t have a routine. I try to pay attention to things around me, things that might prompt a poem or whatever. Typically, I start the day reading the news.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? Being with family, friends, and in various social gatherings helps me, just being exposed to conversation and ideas; I’ve used a lot of lines that I overheard. Also, I read a lot; exposure to good writing helps me get on track.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home? Fresh air. My wife likes to have some windows open, even in winter.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? I joke that, unlike my wife, I’m an avid indoorsman. I like learning about a lot of different things, though. You never know what might be useful.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? I read a lot of fiction, especially spy novels and thrillers; I just like them. I really enjoy James Lee Burke’s Robicheaux novels. I recently read several of Lionel Shriver’s novels; her So Much for That is an all-time favorite. I re-read some of Ron Carlson’s short stories frequently. I’ve got a lot of favorite poets. I keep a copy of Tom Stoppard’s play, Arcadia, on my nightstand; reading it always helps me glimpse anew what’s possible in writing.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? I want to drive across country; I’ve seen very little of the Plains and the West. I also want to travel through Central and Eastern Europe.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? I did have a forty-year career in human resources, and during part of that time I was also an adjunct instructor. Ever since I started reading Sports Illustrated as a kid, I’ve wanted to be a sportswriter, so maybe I’d give that a shot.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? See #2. Also, my parents encouraged reading and learning. At a very young age, I had subscriptions to not only Sports Illustrated and Boy’s Life, but The Atlantic, Harper’s and Esquire. I grew up with an appreciation for the clever and effective use of words.

19 - What was the last great book you read? Ann Napolitano’s Dear Edward. What was the last great film? The Shawshank Redemption (I watched it again not long ago after touring the old Ohio prison where it was filmed).

20 - What are you currently working on? A children’s book.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

July 8, 2022

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with Stuart, Niespodziany, Melançon, LaPierre, Pinder, Kaplan + Win,

Anticipating the release later next week of the thirty-fourth of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the thirty-third issue: Cecilia Stuart, Benjamin Niespodziany, Jérôme Melançon, Margo LaPierre, Sarah Pinder, Genevieve Kaplan and Maw Shein Win.

Anticipating the release later next week of the thirty-fourth of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the thirty-third issue: Cecilia Stuart, Benjamin Niespodziany, Jérôme Melançon, Margo LaPierre, Sarah Pinder, Genevieve Kaplan and Maw Shein Win.Interviews with contributors to the first thirty-three issues (more than two hundred interviews to date) remain online, including: Carrie Hunter, Lillian Nećakov, Nate Logan, Hugh Thomas, Emily Brandt, David Buuck, Jessi MacEachern, Sue Bracken, Melissa Eleftherion, Valerie Witte, Brandon Brown, Yoyo Comay, Stephen Brockwell, Jack Jung, Amanda Auerbach, IAN MARTIN, Paige Carabello, Emma Tilley, Dana Teen Lomax, Cat Tyc, Michael Turner, Sarah Alcaide-Escue, Colby Clair Stolson, Tom Prime, Bill Carty, Christina Vega-Westhoff, Robert Hogg, Simina Banu, MLA Chernoff, Geoffrey Olsen, Douglas Barbour, Hamish Ballantyne, JoAnna Novak, Allyson Paty, Lisa Fishman, Kate Feld, Isabel Sobral Campos, Jay MillAr, Lisa Samuels, Prathna Lor, George Bowering, natalie hanna, Jill Magi, Amelia Does, Orchid Tierney, katie o’brien, Lily Brown, Tessa Bolsover, émilie kneifel, Hasan Namir, Khashayar Mohammadi, Naomi Cohn, Tom Snarsky, Guy Birchard, Mark Cunningham, Lydia Unsworth, Zane Koss, Nicole Raziya Fong, Ben Robinson, Asher Ghaffar, Clara Daneri, Ava Hofmann, Robert R. Thurman, Alyse Knorr, Denise Newman, Shelly Harder, Franco Cortese, Dale Tracy, Biswamit Dwibedy, Emily Izsak, Aja Couchois Duncan, José Felipe Alvergue, Conyer Clayton, Roxanna Bennett, Julia Drescher, Michael Cavuto, Michael Sikkema, Bronwen Tate, Emilia Nielsen, Hailey Higdon, Trish Salah, Adam Strauss, Katy Lederer, Taryn Hubbard, Michael Boughn, David Dowker, Marie Larson, Lauren Haldeman, Kate Siklosi, robert majzels, Michael Robins, Rae Armantrout, Stephanie Strickland, Ken Hunt, Rob Manery, Ryan Eckes, Stephen Cain, Dani Spinosa, Samuel Ace, Howie Good, Rusty Morrison, Allison Cardon, Jon Boisvert, Laura Theobald, Suzanne Wise, Sean Braune, Dale Smith, Valerie Coulton, Phil Hall, Sarah MacDonell, Janet Kaplan, Kyle Flemmer, Julia Polyck-O’Neill, A.M. O’Malley, Catriona Strang, Anthony Etherin, Claire Lacey ,Sacha Archer, Michael e. Casteels, Harold Abramowitz, Cindy Savett, Tessy Ward, Christine Stewart, David James Miller, Jonathan Ball, Cody-Rose Clevidence, mwpm, Andrew McEwan, Brynne Rebele-Henry, Joseph Mosconi, Douglas Barbour and Sheila Murphy, Oliver Cusimano, Sue Landers, Marthe Reed, Colin Smith, Nathaniel G. Moore, David Buuck, Kate Greenstreet, Kate Hargreaves, Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Erín Moure, Sarah Swan, Buck Downs, Kemeny Babineau, Ryan Murphy, Norma Cole, Lea Graham, kevin mcpherson eckhoff, Oana Avasilichioaei, Meredith Quartermain, Amanda Earl, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims, Stephen Collis, Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming thirty-fourth issue features new writing by: Jade Wallace, Katie Naughton, Nathan Austin, Barry McKinnon, Monica Mody, T. Best and Leah Sandals.

And of course, copies of the first thirty-three issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe? Included, as well, as part of the above/ground press 2022 subscriptions! We even have our own Facebook group. It’s remarkably easy.

July 6, 2022

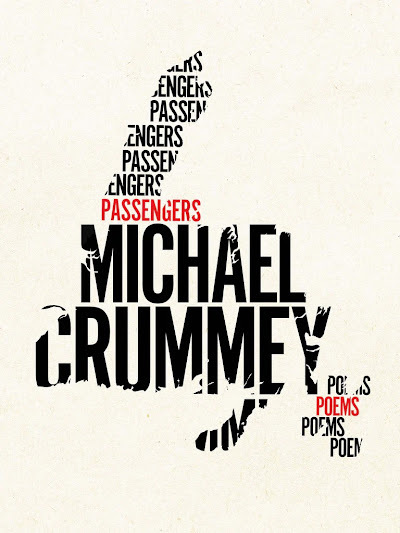

Michael Crummey, Passengers: Poems

The details of the world disappear like coins

lost among tissues and lint in a mother’s handbag.

What we might make of ourselves is suddenly

too far off to see clearly. (“TRANSTRÖMER ON THE HAWKE HILLS / AND THE ISTHMUS OF AVALON”)

It has been a while since I’ve read anything by St. John’s, Newfoundland writer Michael Crummey [see his 2009 '12 or 20 questions' interview here], and possibly even longer, given his latest poetry title, Passengers: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2022), is his first new poetry title in nine years (with his Little Dogs: New and Selected Poems apparently appearing in-between, in 2017). Passengers follows his previous poetry titles Arguments With Gravity (Quarry Press, 1996), Hard Light (Brick Books, 1998; reissued 2015), Salvage (McClelland and Stewart, 2002) and Under the Keel (Anansi, 2013), as well as numerous works of fiction, and the publication of a chapbook or two. Set in three hefty sections of poems, the first is a conversation with and around the Swedish poet, psychologist and translator Tomas Tranströmer (1931-2015) in quite an interesting way, as though offering a look at Crummey’s home space of Newfoundland through, potentially, Tranströmer’s lyric and distance. It is as though Crummey wishes to be the tourist, although a highly articulate and very specific example of one. Written utilizing Crummey’s attempts through Tranströmer’s voice, syntax and perspective, the poems from this section, “YOU ARE HERE: A CIRCUMNAVIGATION,” include poems such as “TRANSTRÖMER ON THE BELL ISLAND FERRY,” “TRANSTRÖMER ON BRIMSTONE HEAD” and “TRANSTRÖMER ON THE MOST EASTERLY POINT / IN NORTH AMERICA.” There is an observational sharpness to Crummey’s lyric, one that exists simultaneously fully-fleshed and composed as a kind of shorthand, managing a clear and solid turn of phrase and line that contains multitudes. As the final third of the poem “TRANSTRÖMER ON THE TABLELANDS, / GROS MORNE NATIONAL PARK” offers:

The journey is longer than it seems from the road. Further than we can carry what we cherish most in the world and all but a handful have turned back toward the waiting vehicles. Where the climb toward the centre of the Earth begins, the path disappears under stones relinquished by those who came this far and carried on.

To introduce the section, Crummey writes: “What follows are loose, amateur translations of pieces I imagine Tranströmer might have written had he recently visited the island of Newfoundland and the coast of Labrador. I’ve tried to remain true to the spirit and tone and to some of the most obvious strategies of Tranströmer’s poetry. But it goes without saying that these pieces would in every way be superior in the original Swedish.” Now, I suspect Crummey might have added that last piece as a kind of tongue-in-cheek throwaway, but I think there would have been something enormously interesting had he attempted to get at least one of these poems translated into Swedish by someone familiar with Tranströmer’s work, and then, through a further translator, returned the poem back into English, to see if the poems, in English, at least, might have lined up with a voice similar to that of Tranströmer. Admittedly, there are moments where it is unclear where the lens of Tranströmer specifically fits into these poems and why, in poems that could just as easily exist without him referenced at all, allowing them to become entirely Michael Crummey poems on elements of Newfoundland culture, history and landscape. Crummey’s engagement with the syntax and thinking of Tomas Tranströmer’s work might suggest itself as the impulse for these poems, but that might simply be a means to a particular end, seeking to works this particular collaboration with voice and the idea of distance, to approach a geography and it’s people that he understands deeply; perhaps seeking a different perspective on home, for the sake of seeing what he otherwise might never could. It is though, through Tranströmer, Crummey is attempting to approach his home again as for the first time. As the poem “TRANSTRÖMER ON THE SOUTHSIDE HILLS” begins: “The Natives are most notable for their absence. / Even their graves are vacant. / The marker erected to explain these circumstances // is playing hide & seek with neighbourhood children / and can’t be located. It keeps very still / even after the youngsters go home to their beds, // even when it suspects they’ve forgotten the game entirely.”

To introduce the section, Crummey writes: “What follows are loose, amateur translations of pieces I imagine Tranströmer might have written had he recently visited the island of Newfoundland and the coast of Labrador. I’ve tried to remain true to the spirit and tone and to some of the most obvious strategies of Tranströmer’s poetry. But it goes without saying that these pieces would in every way be superior in the original Swedish.” Now, I suspect Crummey might have added that last piece as a kind of tongue-in-cheek throwaway, but I think there would have been something enormously interesting had he attempted to get at least one of these poems translated into Swedish by someone familiar with Tranströmer’s work, and then, through a further translator, returned the poem back into English, to see if the poems, in English, at least, might have lined up with a voice similar to that of Tranströmer. Admittedly, there are moments where it is unclear where the lens of Tranströmer specifically fits into these poems and why, in poems that could just as easily exist without him referenced at all, allowing them to become entirely Michael Crummey poems on elements of Newfoundland culture, history and landscape. Crummey’s engagement with the syntax and thinking of Tomas Tranströmer’s work might suggest itself as the impulse for these poems, but that might simply be a means to a particular end, seeking to works this particular collaboration with voice and the idea of distance, to approach a geography and it’s people that he understands deeply; perhaps seeking a different perspective on home, for the sake of seeing what he otherwise might never could. It is though, through Tranströmer, Crummey is attempting to approach his home again as for the first time. As the poem “TRANSTRÖMER ON THE SOUTHSIDE HILLS” begins: “The Natives are most notable for their absence. / Even their graves are vacant. / The marker erected to explain these circumstances // is playing hide & seek with neighbourhood children / and can’t be located. It keeps very still / even after the youngsters go home to their beds, // even when it suspects they’ve forgotten the game entirely.” Really, the opening section sets the tone of the entire collection, as Crummey examines poems that seek out alternate perspectives on geography and space, for the sake of a broader perspective. In the second section, “THE DARK WOODS,” individual poems seek out a sense of European travel, writing poems such as “BELFAST,” “WARSAW,” “INNSBRUCK,” “STOCKHOLM” and “VIENNA,” writing of outsiders, locals and foreigners, suggesting that the sheen of the entire collection aims to include and envelop the perspective of the outsider, one who might not carry all the information, but who might be able to catch what locals may have overlooked, or lost through familiarity. Even John Newlove, through his poem “The Permanent Tourist Comes Home,” wrote of the newness that distance allows, ending his poem “Enough / of this. The mountains are bright tonight / outside my window, and passing by. / Awkwardly, I am in love again.”

The poems of Passengers seek freshness, although less of mere passengers than the attempt at seeking the perspective of outsiders, looking in. “No tourist escapes cliché.” he writes, a line that opens both the poem “TRANSTRÖMER ON SIGNAL HILL” as well as “STOCKHOLM.” The mantra he offers is true, and I’ve known more than a few poets unwilling to even engage with the dread notion of the “travel poem,” not wishing to inflict one’s own limited understandings and biases (potentially colonial ones, as well) into a lyric imagining “other,” but Crummey perhaps sidesteps elements of this through working so fully to begin with his home space, seeking a voice through which to otherwise speak. He is aware of those limitations, and the poems that stretch across Europe are less all-encompassing visits than engagements with elements of history (including, no less, an encounter with ABBA), one moment after another, even into and through a slight rippling of abstract. “No one dropped in on Sarajevo during the war.” he writes, to open that city’s namesake poem, “Sarajevo barely slept and rarely left the house // scanning the hills from upstairs windows, / weathering the blockade with black humour // and booze as it waited for the worm to turn.”

Into the third and final section, Crummey turns from Tranströmer’s relatively contemporary Newfoundland to a character Christianity sees as the original outsider, Lucifer, moving through Newfoundland over the centuries since landing as a stowaway, as the opening poem, “NATIVE DEVIL,” writes, “at the tail end of the Middle Ages.” Again, Crummey writes home from the stance of the outsider, offering Lucifer as counterpoint to Tranströmer, as he writes again through elements of Newfoundland landscape, history and culture, speculating the perspective the devil might have on his home ground. And yet, Crummey writes as he seems to have done his entire publishing history-to-date, writing of his deep love for his home province, from the intellectual curiosity of Tomas Tranströmer, to a land even the devil would love. As the poem “NATIVE DEVIL” continues: “The country he landed in seemed little more than a breeding ground for / blackflies. An idiot wind, granite half-cloaked in a ragged hair-shirt of / spruce. / It was love at first sight.”

LUCIFER ON GEORGE STREET

The cobbled pavement hobbles his cloven feet. He lurches drunkenly as he navigates the drunken crowds, the bleary racket. He wears a leather coat to his ankles, his sulphur stink muted by the cold drizzle. Two city blocks of bars, but for all its rowdy dissipation the street disappoints him. Most of the shamelessness on display is carnival stupidity, infantile gratification. His mirrored horns are dismissed as costume. A girl in a miniskirt drapes her still-warm underwear from one bony thorn. Shit-faced boys crowd him for selfies, flashing their barnyard tongues at the screen. These are his children, by all accounts. The thought makes him want to eat something raw.

He has always felt more at home in a church.