Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 118

August 4, 2022

Dara Barrois/Dixon, Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina

My review of

Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina

(Wave Books, 2022), by Dara Barrois/Dixon is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. And I even reviewed her

You Good Thing

(Wave Books, 2014) [see such here] a million years ago as well!

My review of

Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina

(Wave Books, 2022), by Dara Barrois/Dixon is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. And I even reviewed her

You Good Thing

(Wave Books, 2014) [see such here] a million years ago as well!August 3, 2022

Emma Healey, Best Young Woman Job Book: A Memoir

My mother’s play is co-written with two of her best friends. Each woman plays a fictionalized version of herself, stalking the stage in red lipstick and a black cocktail dress. Sometimes they speak all in one voice like a Greek chorus; other times, they split apart to deliver individual monologues.

Each of the three characters has recently ended a significant relationship—with a boyfriend, a live-in partner and a husband, respectively. My mother plays an anxious, obsessive, organized single mother who’s in the middle of divorcing the father of her child. The thesis of the show is that with time, even the worst parts of your life can become just a story. All you have to do is tell it again and again.

I’m very charmed and delighted by Toronto poet and critic Emma Healey’s latest,

Best Young Woman Job Book: A Memoir

(Toronto ON: Random House Canada, 2022), a particular kind of coming-of-age storytelling that is vibrant, evocative in detail and rich in propulsive storytelling. Healey is the author of two poetry collections—

Begin with the End in Mind

(ARP Books, 2012) and

stereoblind

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2018) [see my review of such here]—and her shift from prose poem into memoir displays a clear sense of narrative and music throughout her sentences. There is a funny, witty wealth of description to her prose, as she writes of being the daughter of two playwrights, and being raised by her single mother, who both wrote plays and acted throughout her childhood. There is something fascinating about the ways in which Healey writes of her experiences around language, performance and writing through these connections, and Healey is a natural storyteller, as she tells a variety of stories that a number of literary folk might catch echoes of, but told in a way to leave out certain kinds of specifics (names, locations). It is as though to become specific would take away from the purpose of the stories herself: to articulate those experiences and how she moved through them. She writes of family, worthwhile and terrible jobs (including in publishing) and relationships, including a toxic and even abusive relationship or two, and how these affected her, and what she may have garnered from each of them, as well as what she might, in the end, have been left with. These are the facts that exist behind the text, and the focus of her narrative is far more on a young woman navigating the world, showing elements of fearlessness, apathy, empathy, depression, youthful carelessness and a slow, continuous push to move forward and beyond all the chaos into the positive. Honestly, this is a delightful read by a seriously talented writer; I can’t really say anything else beyond that.

I’m very charmed and delighted by Toronto poet and critic Emma Healey’s latest,

Best Young Woman Job Book: A Memoir

(Toronto ON: Random House Canada, 2022), a particular kind of coming-of-age storytelling that is vibrant, evocative in detail and rich in propulsive storytelling. Healey is the author of two poetry collections—

Begin with the End in Mind

(ARP Books, 2012) and

stereoblind

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2018) [see my review of such here]—and her shift from prose poem into memoir displays a clear sense of narrative and music throughout her sentences. There is a funny, witty wealth of description to her prose, as she writes of being the daughter of two playwrights, and being raised by her single mother, who both wrote plays and acted throughout her childhood. There is something fascinating about the ways in which Healey writes of her experiences around language, performance and writing through these connections, and Healey is a natural storyteller, as she tells a variety of stories that a number of literary folk might catch echoes of, but told in a way to leave out certain kinds of specifics (names, locations). It is as though to become specific would take away from the purpose of the stories herself: to articulate those experiences and how she moved through them. She writes of family, worthwhile and terrible jobs (including in publishing) and relationships, including a toxic and even abusive relationship or two, and how these affected her, and what she may have garnered from each of them, as well as what she might, in the end, have been left with. These are the facts that exist behind the text, and the focus of her narrative is far more on a young woman navigating the world, showing elements of fearlessness, apathy, empathy, depression, youthful carelessness and a slow, continuous push to move forward and beyond all the chaos into the positive. Honestly, this is a delightful read by a seriously talented writer; I can’t really say anything else beyond that.August 2, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Aaron Kreuter

Aaron Kreuter

[photo credit: Rick O'Brien] is the author of the short story collection

You and Me, Belonging

(2018) and the poetry collection

Arguments for Lawn Chairs

(2016). His writing has appeared in places such as Grain Magazine, The Puritan, The Temz Review, and The Rusty Toque. Kreuter lives in Toronto and is a postdoctoral fellow at Carleton University.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

is his second book of poems.

Aaron Kreuter

[photo credit: Rick O'Brien] is the author of the short story collection

You and Me, Belonging

(2018) and the poetry collection

Arguments for Lawn Chairs

(2016). His writing has appeared in places such as Grain Magazine, The Puritan, The Temz Review, and The Rusty Toque. Kreuter lives in Toronto and is a postdoctoral fellow at Carleton University.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

is his second book of poems. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’d say the main way my first book changed my life is that I now had a book out in the world, not to be too tautological about it. It gave me the space and clean slate to being working on new poems, new books. The poems in Shifting Baseline Syndrome, my second collection of poems, are more energetic, more flippant, more desirous, and more frisky than my earlier work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry has been an annoying friend since earliest childhood. I couldn’t get away from it if I tried.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

As for many aspects of writing for me, it is entirely dependent on the project. Some poems take weeks, months, years, to germinate, root, stalk, and flower (if flower it ever does). Sometimes I write down a title for a poem, and come back to it years later (or not at all). Sometimes a poem falls out of me like a piece of blowdown in the forest. It could be years between poems, or minutes.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Since the first book of poems (Arguments for Lawn Chairs, available in my basement), I have more or less written towards a project. This doesn’t mean anything more than the book is in mind as I write, out there, in the future.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I definitely enjoy readings. I remember the first time I read publicly—in Montreal, for one of my first publications, at Concordia’s undergraduate journal Soliloquies. I was terrifically nervous. But I went on stage, and I did it. I never thought I’d be the kind of person who could just go up on stage and perform, but apparently I can be, and I am. I’m looking forward to in-person readings starting up again, I enjoy the energy of, and interaction with, an audience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’d say that behind any one poem, story, or longer piece I write is a frothing ocean of idea, concern, rage, and love. Unless, of course, I’m just trying to be funny. An all-star list of some of the theoretical concerns of Shifting Baseline Syndrome would have to include: the metaphysics of television; the destruction of the world; what I enigmatically refer to as “Jewish stuff”; heritage, legacy, family; and acid trips in portapotties.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer, mostly, is here to make fun of the powerful, to disrupt, to shake up and shake off, to celebrate and complain. Or, you know, whatever.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. Or one or the other, depending on the project, the editor, and the ebb and flow of my moods.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To always take care of your shoes.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories to creative non-fiction to the novella)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ve never had much trouble moving between genres. For me, each project is its own genre.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write most days. But, that being said, I’m a firm believer in the fact that the mind is always working.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The guitar. Music. The lake. The river. Alice Munro. Ursula Le Guin.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Bowties and kasha (though that’s really my grandmother’s home).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, most definitely: rock, jazz, folk, classical, but most importantly improvisational rock and roll. The way a jam moves, changes, opens, builds, peaks, comes down.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Alice Munro. Ursula Le Guin. Michael Chabon. Mordecai Richler. Leonard Cohen. Toni Morrison.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Canoe a massive river. Like a fifty-day river.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Canoe guide. Commune chef. Daycare teacher.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s never really seemed like a choice.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently reread The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin, and it rewired my brain once again. Amazing how in each reading I focus on a different aspect. I also just read Matrix by Lauren Groff, which is absolutely, absolutely fantastic.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m finishing up a draft of a novel, called Lake Burntshore, that takes place at a Jewish summer camp in Ontario, and is about settler colonialism, Jewish stuff, and the land. There’s also a new batch of poems slowly working its way up from the deep.

August 1, 2022

Ongoing notes: early August, 2022: Mia Ayumi Malhotra + Cassidy McFadzean,

August, already. All I can do is remind you: check out

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, the new issue of which starts posting today! And you remember that above/ground press is holding a 29th anniversary big ridiculous sale this summer, yes? And I'm still selling copies of this new poetry book of mine! So many exciting things!

August, already. All I can do is remind you: check out

periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, the new issue of which starts posting today! And you remember that above/ground press is holding a 29th anniversary big ridiculous sale this summer, yes? And I'm still selling copies of this new poetry book of mine! So many exciting things! San Francisco CA: Following her full-length debut, Isako Isako (Alice James Books, 2018), and winner of the 2022 BOOM Chapbook Contest is Bay Area poet Mia Ayumi Malhotra’s charming and utterly striking Notes from the Birth Year (bateau press, 2022), a suite of lyrics that write out elements of new motherhood, and connecting deeper to a lineage; the threads that begin to open fully and further across both genealogical directions. “With this telling,” she writes as part of “On Mind and Memory,” “I am weaving her an origin story—one in which, I realize, / I am incidental. This is about her, not me.” Hers is a lyric simultaneously casual and crafted, set as sketched notes on the possibilities of newness and connectivity around having a small child. These poems are remarkable for their intimacy and their scale, written across and through distances great and small, long lines of calm, hesitation and memory, reaching out into a new way of seeing what was already there. “Strange,” she writes, as part of “On Gestation and Becoming,” “how what is closest most eludes us.” She composes poems that engage with the emergence through their own possibilities, seeking to connect poetic form and structure with an openness that having a growing child allows. As the poem “On Form” begins:

I became a mother and I began to write like a Japanese woman.

Which is to say: I began to write like myself—from the imaginary whence my mother’s mother and her mother and her mother before her came.

Things That Are Distant Though Near: Festivals celebrated near the Palace. The zigzag path leading up to the temple of Kurama.

When I became a mother, my lines began to grow less mannered, less sculpted—and this wild, itinerant prose did not adhere to shapeliness.

Instead it spilled from birth into death and questions of beauty and my opinions about this and that, arranging itself as it wished.

An unruly, yet artful text.

Kentville NS: From Regina-born and Brooklyn-based Canadian poet Cassidy McFadzean, the author of the full-length collections Hacker Packer (McClelland and Stewart, 2015) and Drolleries (McClelland & Stewart, 2019), comes the chapbook Third States of Being (Gaspereau Press, 2022), a title composed as “a crown of sonnets written for my mother, Catherine Mae McFadzean (née Warriner), who was born May 29, 1957, and died September 24, 2020.” Admittedly, I had to look up the specific term, as the Poetry Foundation website offers: “The sonnet redoublé, also known as a crown of sonnets, is composed of 15 sonnets that are linked by the repetition of the final line of one sonnet as the initial line of the next, and the final line of that sonnet as the initial line of the previous; the last sonnet consists of all the repeated lines of the previous 14 sonnets, in the same order in which they appeared.” As her poem begins: “The way loss ricochets through memory / altering every moment that preceded / Those left behind forever changed by it / with renewed engagements tending / ever loyally to the earth and its labours / like caretakers in the palace gardens [.]”

There is a curious language to her elegy, one that seeks a particular crafted phrase, accumulating line upon self-contained line until the lines begin to narratively collage into a larger shape. She writes her elegy slant against the loss of her mother, attempting to articulate points through the loss and the very notion of scattered, shuffled memory through shuffled language. Each step is both the same and not the same, all of which ends up in that particular spot.

IX

Galloping off and never turning back

Was your death swift and unexpected

because a long and drawn-out illness

would have destroyed me, unable to rise

to the occasion? In the night I berate myself

with circular thinking: if we’re only given

what we can handle is it my fault for being

too weak to bear your suffering?

I search through pages of histopathology

to find the arteries of your heart calcified

A pink marbling on the tissue slides

tiny cells became lilac buds in a river

floating downstream, almost beautiful

with knowledge the invisible will betray

July 31, 2022

Dustin Pearson, A Season in Hell with Rimbaud: Poems

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud

I dreamt I was showing my brother around in Hell.

We started inside the house.

Everything was brown besides the white sheets

in the bedrooms. I let him look

outside the window, told him it was hottest there,

where the flames rolled against the glass,

as if a giant mouth were blowing them,

as if there were thousands caught in the storm,

pushing it onward with mindless running,

save a desperation for something else.

How had there been a house in Hell

and we invited with time to spend? Why was it

I hadn’t questioned how I got there? My brother

growing so tired from the heat, the sweating?

surely we could open the door, he said. Surely there’ll be

a breeze. Even seeing already, even burning himself

on the doorknob. His eyes turned back in his head

working his way to the bedrooms, straining

the sheets with his blistered hands, and though I knew the beds

weren’t for the rest of any body, I sat by and let him sleep.

The third full-length poetry collection by Tulsa, Oklahoma poet Dustin Pearson [see my 2018 ’12 or 20 questions’ interview with him here], following

Millennial Roost

(C&R Press, 2018) and

A Family Is a House

(C&R Press, 2019), is

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud: Poems

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2022). Pearson writes of brothers, masculinity and borders, and of a fear and vulnerability that is deeply felt throughout the collection. “Hell is a state of mind I slipped into / years ago,” he offers, to open the poem “Regardless,” “tossing a red balloon / to my brother. Even then, // I’d never be able to do what he couldn’t. / I’d always fall short of what he could do. / I couldn’t convince myself // I went because I loved him.” There is such a sense of music and rhythm to these lyrics, such a sense of singing punctuated by trauma. Pearson’s narrator writes his brother and a dream of his brother, writing a journey through Hell and how he got there, seeking out a beloved sibling, and mourning a loss he refuses to let go of. “He was the first person who told me I stood out,” he writes, as part of “Pain on a Soft Surface,” “something my mother had tried to, lovingly, / make me feel, something my father denied / completely. I resigned myself to the idea. / In a man’s world, I’d never be anything, / even if I’d still be forced to compete.”

The third full-length poetry collection by Tulsa, Oklahoma poet Dustin Pearson [see my 2018 ’12 or 20 questions’ interview with him here], following

Millennial Roost

(C&R Press, 2018) and

A Family Is a House

(C&R Press, 2019), is

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud: Poems

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2022). Pearson writes of brothers, masculinity and borders, and of a fear and vulnerability that is deeply felt throughout the collection. “Hell is a state of mind I slipped into / years ago,” he offers, to open the poem “Regardless,” “tossing a red balloon / to my brother. Even then, // I’d never be able to do what he couldn’t. / I’d always fall short of what he could do. / I couldn’t convince myself // I went because I loved him.” There is such a sense of music and rhythm to these lyrics, such a sense of singing punctuated by trauma. Pearson’s narrator writes his brother and a dream of his brother, writing a journey through Hell and how he got there, seeking out a beloved sibling, and mourning a loss he refuses to let go of. “He was the first person who told me I stood out,” he writes, as part of “Pain on a Soft Surface,” “something my mother had tried to, lovingly, / make me feel, something my father denied / completely. I resigned myself to the idea. / In a man’s world, I’d never be anything, / even if I’d still be forced to compete.” “Every body that hits the ground in Hell / will get up should they choose it.” Pearson writes, to open the poem “Lying Down,” “There’s plenty of death and destruction / but no dead.” Composed in six sections of narrative lyrics, the poems in Pearson’s A Season in Hell with Rimbaud: Poems are searching, desperate and impossible, and the lengths through which this narrator would travel. “I cast a wide net in Hell for my brother. / I was both the person who held the net / and the bait inside,” he writes, to open the poem “Hell’s Wide Net,” near the end of the collection, “my arms craning / back and throwing forward, letting / the string reel through my hands.”

July 30, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Prathna Lor

Prathna Lor is the author of

Emanations

.

Prathna Lor is the author of

Emanations

. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Not sure yet but so far refreshing and lifting. Publishing a book is like watching yourself from 5-10 years ago come onto the stage. Meanwhile you are in the present trying to figure out what to do.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry via fiction, specifically through Woolf. In her work, each line is like a bent horizon and I’m always trying to figure out what is emerging.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Slow, agonizing, and always surprising.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Trying to write one poem continually, trying to say one thing, continually; always emerging though never fully glimpsed.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Yes, something happens between voice and text on and off the page – it is essential to be in the body of your own work, to live in the sound of your own voice as fully and boldly as possible.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

How can we hold onto each other at great distances?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Living beautifully, out of mind.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential and never difficult, in my experience, since a good editor (and I have been blessed in this regard), will always want the work to reach its potential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Let others gift and receive you.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

It is complete chaos.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Outside.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pork bone, incense, lime leaf, dried persimmons.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Just walking.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anything I can get my hands on.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Sculpture.

16 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

An intractable feeling or being bad at most everything else.

17 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Liz Howard’s Letters in a Bruised Cosmos.

18 - What are you currently working on?

A novel.

July 29, 2022

Annick MacAskill, Shadow Blight

On the invention of the seasons

You can’t blame that part on the heaven &/or hell

For Hades hath no such fury

Nor Jove

But a woman can do anything in her pain

If she had to lose so the world would lose

First she tore at her hair

She beat her breast

Then she turned her rage to the black soil itself

& to the sheep like tufts of cloud

& the Sicilian shepherds w/ their felt caps

They say she broke the plows w/ her own hands

That in her sorrow the mother became the blight

Halifax poet Annick MacAskill’s latest—after No Meeting Without Body (Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2018) [see my review of such here] and Murmurations (Gaspereau Press, 2020) [see my review of such here]—is Shadow Blight (Gaspereau Press, 2022), a book that works through, as the back cover offers, “the pain and isolation of pregnancy loss through the lens of classical myth. Drawing on the stories of Niobe—whose monumental suffering at the loss of her children literally turned her to stone—and others, this collection explores the experience of being swept away by grief and silenced by the world.” Shadow Blight opens with all potential and possible ghosts before drifting through a contemporary into a backdrop of mythological figures, writing the enormity of loss and the slow and sudden loss into and through the isolating realities of rage and grief. As the third and final stanza of the opening poem, “Swimming Upwards,” reads:

But April hosts its own—the ghost

of my due date, drifting

in the hypothetical—one silver week,

its arms outstretched—

From there MacAskill slips into citations of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, writing mothers and other changed figures from Greek myth, including Dryope (who went into labour while dragging a sacrificial bull by its horns) and Chloris (who was transformed into the deity Flora, and was said to have been the one to transform Adonis, Attis, Crocus, Hyacinthus and Narcissus into flowers), but focusing her attention on the figure of Niobe, who wept for the loss of her many children, all of whom had been killed by the Titan Leto as punishment for Niobe’s pride. As MacAskill’s poem “Delos” ends: “as when before the birth / her children weren’t living facts // but a cloudy possibility.” Miscarriage still seems a subject that sits in the shadows, away from open conversation, and the experience of losing a child would be isolating enough, even without so much silence attached. MacAskill attempts to not only write out the silences but through them. “body stubborn / blood slowing / limbs / already / turning / to rock,” she writes, to close the extended poem “Homeric Similie,” “mouth / wide / o / pen [.]”

From there MacAskill slips into citations of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, writing mothers and other changed figures from Greek myth, including Dryope (who went into labour while dragging a sacrificial bull by its horns) and Chloris (who was transformed into the deity Flora, and was said to have been the one to transform Adonis, Attis, Crocus, Hyacinthus and Narcissus into flowers), but focusing her attention on the figure of Niobe, who wept for the loss of her many children, all of whom had been killed by the Titan Leto as punishment for Niobe’s pride. As MacAskill’s poem “Delos” ends: “as when before the birth / her children weren’t living facts // but a cloudy possibility.” Miscarriage still seems a subject that sits in the shadows, away from open conversation, and the experience of losing a child would be isolating enough, even without so much silence attached. MacAskill attempts to not only write out the silences but through them. “body stubborn / blood slowing / limbs / already / turning / to rock,” she writes, to close the extended poem “Homeric Similie,” “mouth / wide / o / pen [.]” There is a way that MacAskill writes her way through the threads of myth, utilizing the details of myth as a means to work her way through, beyond a simple retelling, is reminiscent, slightly, of North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson’s Helen Or My Hunger (YesYes Books, 2020) [see my review of such here]. One should mention, also, American poet and translator Niina Pollari’s Path of Totality (Soft Skull Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], a collection that more overtly and directly writes “about the eviscerating loss of a child, the hope that precedes this crisis, and the suffering that follows.” In comparison, MacAskill writes not as diary but working through the portrait of such a loss through the lens of the stories of mythological Greek women. “But a woman can do anything in her pain,” she writes. Or, as the poem “First Snow” offers: “She scales // the choss, and on the way, ties Proserpine’s yellow ribbon / across the slim arm // of a spontaneous birch tree.”

At sixty-four pages, Shadow Blight isn’t a lengthy collection, but her lyric allows for an openness, an extension of line and phrase that stretches her phrases and sentences across multiple pages; perhaps Shadow Blight is less a collection than a single poem writing out an experience, pulled into and wrapped up as a lyric suite uniquely broken, collected and packed. “—o how beautiful / the poets make our catastrophes—” she writes, to close the poem “Dryope.” And yet, through the grief there is a kind of hope, examining the stories of mythological women and connecting them to her own experience, one that allows for the loss to become less isolating, and less singular. Stepping back, beyond myth, and bookending the collection to close is the short sequence “Miscarriage,” that includes:

on a Saturday in September

we waited in the ER seven hours

where the thought that we might see you

puffed up my chest

the ultrasound was hazy

as unreality

because you were already out

ahead of me

July 28, 2022

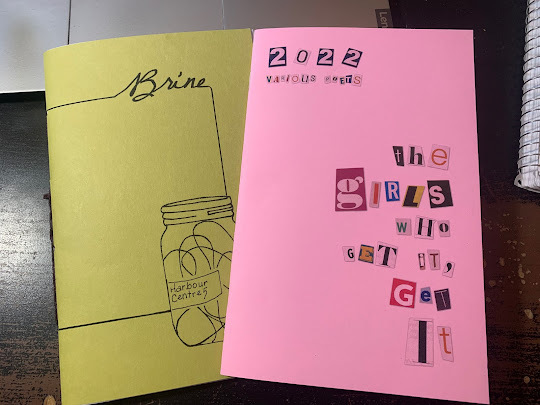

Ongoing notes: late July, 2022: Ryan Fitzpatrick’s ENGC86 + the Harbour Centre 5

I’ve always been fond of writing group and/or workshop chapbooks. Seymour Mayne used to produce annual chapbooks from his workshops at the University of Ottawa, going back to the 1970s, I believe; and I think Irving Layton produced at least one during his time at York University (around here somewhere I still have a copy that Robert Kroetsch handed me, produced by himself after a session at Sage Hill): a collection of poems by the various participants in that particular group. Recently, two different chapbook titles have landed on my doorstep (what I am saying here is: mail me copies of these things; I like these things and am open to discussing them), so I thought it might be fun to discuss them together:

I’ve always been fond of writing group and/or workshop chapbooks. Seymour Mayne used to produce annual chapbooks from his workshops at the University of Ottawa, going back to the 1970s, I believe; and I think Irving Layton produced at least one during his time at York University (around here somewhere I still have a copy that Robert Kroetsch handed me, produced by himself after a session at Sage Hill): a collection of poems by the various participants in that particular group. Recently, two different chapbook titles have landed on my doorstep (what I am saying here is: mail me copies of these things; I like these things and am open to discussing them), so I thought it might be fun to discuss them together: Toronto ON: From Ryan Fitzpatrick’s ENGC86 Creative Writing: Poetry II, the spring 2022 class at the University of Toronto Scarborough comes The Girls Who Get It, Get It (Toronto ON: Block Party, June 2022). As Fitzpatrick’s “Foreword” offers:

At the beginning of the semester, I tasked this group of promising writers with the problem of the poetry project. In other words, I asked them to tell me what they wanted to write about and we’d hash out the how and the why together. We’d grapple with the three corners of a questionably drawn Venn diagram I threw up in the middle of a Zoom call. We’d concern ourselves with form as an extension of content and content as an extension of relation. We’d move from the problem of just how to approach the villanelle to the explosive narrative possibilities of a million internet forms. We’d occasionally ask the dreaded question “So What?” like someone was about to go down for elimination in the MasterChef kitchen. We’d move between narrative flows and imagistic surprise. Eventually we reached the oft repeated refrain “The girls who get it, get it” as a way around the complex and sometimes messy specificities of our poetry, because life is messy and not everyone will understand everything all the time, but you also have to have faith that what you write will find the audience who has been searching everywhere for the right words at the moment they needed them.

The collection includes writing from Isla McLaughlin, Mary Maliszewski, Shanti Dhoré, Catherina Tseng, Morgen Mulcaster, Regina Zhao, Timea James, Sonika Verma, Georgea Jourjouklis, Alexis Murrell, Kasthuri Kanesalingam, Uniekar Bacchus, Lamia Firasta, Rana Sulaman, Alexa DiFrancesco, Victoria Butler and Joseph Donato. “share that quote from / Maggie Nelson,” Isla McLaughlin writes as part of “is this what it means to be a girl online?,” “hope at least one / person recalls // your crying, it’s / intensity // continue to / suffer so loud [.]” “it’d be so sweet if things just stayed the same,” Alexa DiFrancesco writes, as part of “when mom is ukrainian,” “do you know who you are?” There is such a lovely mix of confidence, swagger and curiosity through the poems assembled here, each of them reaching out in their own ways into attempting to get a handle on writing, thinking and where this all goes. As much as anything, also, it is the range of styles that intrigues about this small collection. “But they’re not available at 11:50pm,” Lamia Firasta writes, in “Assignment: 11:59,” “When I am checking all my citations / And wondering if there’s an i in lowercase [.]” I am intrigued by the narrative leaps and associations of Sonika Verma’s “Kaleidoscope,” a piece that begins: “to this day my bank pin number is my middle school friend’s / birthday. every winter i bake a cheesecake the way a bakery which / i haven’t gone to in four years advised me to. my pajamas are a / worn-down shirt from high school volunteering of an event that / relocated.” Or the first half of Catherina Tseng’s “pear-shaped ladies,” a poem that includes some very sharp phrases and observations:

scar-slicked thighs stick to the bottom of the plastic chair,

twisting uncomfortably as white men walk with their asian

girlfriends. at starbucks a girl with small tits and sweat-stained

armpits browses for swimwear on amazon. her mid-range crop

top says that there is no ethical consumption under capitalism

as she clicks clicks clicks lrg tankini two-piece red women’s sexy

cute high-waist tie knot into the cart. body knows nothing. only

instinct and survival and potential and nerve. body is divine.

gooseflesh rises along roadmaps of stretch marks and cellulite,

charting rivers, climbing mountains, marking crossroads,

claiming territories. a god is just a baby.

I am hoping to see more work by these folk; I am curious to see where they might go. I also have an extra copy of this, if anyone is interested. Otherwise, check here.

Vancouver BC: I recently received a copy of the chapbook Brine (2022) by Vancouver’s Harbour Centre 5. I hadn’t been previously aware of this particular writing group, although I’m aware of at least two of their members (I interviewed Christina Shah through the “Six Questions” series, and both Shah (posted June 16, 2021) and Robbie Chesick (scheduled for August 23, 2022) have poems in the “Tuesday poem” series). As Shah’s opening poem, “dig in,” begins:

learn to become lignin

living, but stiff

the interdependent men

will talk

over you

at you

about you

object, topic

nascent agent

put your roots down

and pretend

the storms are normal

The poets collected here are Christina Shah, Jaeyun Yoo, James X. Wang, Rebecca Holand and Robbie Chesick, all of whom, according to their author biographies, have been emerging in a variety of literary journals across Canada, but haven’t yet chapbooks or full-length collections. There is a nice narrative bob and lyric bounce to the poems of Jaeyun Yoo, such as the final stanza of the three-stanza “a woman of water,” that offers:

most days, she scurried past and went to bed

a tadpole hiding under clumps of mud

another day, I had to wrest the bottle away

and watched her balter, like cattails lurching

their swollen heads back and forth

some days, she nibbled the sandwich crust

curled around me as if a warm palm to a cup

then I would finally lean my weight

boulders in her water, briefly buoyant

As they write at the back: “Brine is a collaborative chapbook created by Harbour Centre 5, a collective of emerging poets who met through Simon Fraser University’s Weekend Poetry Course. They craft poetry with a process akin to brining—words submerged, cured, until rich in flavour.” Dedicated “to our mentors, Fiona Tinwei Lam & Evelyn Lau,” I’m reminded of when I was first introduced to the work of Newfoundland writers Michael Winter, Lisa Moore and others, through a group anthology self-produced back in 1994, the culmination of nine years of self-directed workshopping a group of emerging writers had managed, after their creative writing class had ended. It is, as they say, possible to get there from here.

July 27, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Frances Peck

Frances Peck (North Vancouver) is a long-time editor, ghostwriter, and instructor. She’s the author of Peck’s English Pointers, an online grammar and writing resource; a co-author of the HyperGrammar website; and an occasional essayist and blogger. She wrote fiction and poetry until her early twenties, when she stopped (ironically) to earn a living from words. Now she’s rediscovering the magic of making things up. Her debut novel is

The Broken Places

(NeWest Press, April 2022). Connect with Frances on Twitter (@FrancesLPeck) or visit her website (francespeck.com).

Frances Peck (North Vancouver) is a long-time editor, ghostwriter, and instructor. She’s the author of Peck’s English Pointers, an online grammar and writing resource; a co-author of the HyperGrammar website; and an occasional essayist and blogger. She wrote fiction and poetry until her early twenties, when she stopped (ironically) to earn a living from words. Now she’s rediscovering the magic of making things up. Her debut novel is

The Broken Places

(NeWest Press, April 2022). Connect with Frances on Twitter (@FrancesLPeck) or visit her website (francespeck.com). 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Confusingly, the first novel I wrote, Uncontrolled Flight, will be the second one published, in fall 2023; the second novel I wrote, The Broken Places, is the first to hit the shelves. Regardless, to have a novel, any novel—first, second, fifth—published, with my actual name on it (not ghostwritten) is the realization of my oldest, most secret dream. Oldest because I started cranking out the beginning chapters of novels around age nine. And most secret because until recently I couldn’t admit to anyone that I wanted to write a novel. It felt like something I could never do, that I wasn’t worthy of. Other people wrote novels. Not me.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

It was a kind of imprinting. In grade three, the teacher gave several of us who were easily bored these story prompts to work from. They were all about—at least, this is how I remember it—dustballs or hairballs or furballs. Something slightly nasty and clumpy and not quite human. We were to write stories about these balls as if they were people. It was the most stimulating thing I’d done up to that point, apart from reading and cutting pictures out of catalogues. For the next fifteen years, I wrote a steady stream of short stories, novel chapters, comic strips, magazines, school newspaper articles, plays, and poems. I kept coming back to poetry. I had a couple of poems published in my university’s literary magazine. But I was a terrible poet. Everything sounded like fake Yeats. (That sounds like a band name: Fake Yeats.)

After that, I made a career from writing and editing non-fiction, or what nowadays we’d call “content”: reports, marketing material, training manuals, essays, web copy, and so forth. All the while, the word “novel” kept sounding in my head. As a young writer I’d made many stabs at novels, but I’d never finished one. I desperately wanted to finish one.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m a slow starter. The image that precipitated my first novel, the one that will be published second, haunted me for years before I started to write. There’s always something more pressing, and frankly more appealing, to do than churn out that painful first draft. But once the draft is done, the editing can begin. After years of being an editor and teaching editors, I feel great relief when I get to that stage. The two novels I’ve finished so far have needed heaps of reshaping, because I’m a pantser all the way. It’s inefficient, but I don’t care. For whatever reason, rigorous outlining kills the magic for me.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Leaving aside my freelance work, which has usually involved shorter pieces, my projects are always books. Novels are all I’m interested in writing just now. I wish it were otherwise. At one point I tried to convince myself to write a short story, just for the satisfaction of finishing something in less than, say, two years. But stories don’t come to me. Novels do.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ask me in a year! At the time of writing, with my book officially out under a month ago, I’ve done a grand total of three readings: two online, one in person. Though it’s scary to say my own words out loud to a crowd, I suspect I’ll learn to enjoy readings. In my family we were made to read aloud, and to memorize poems and recite them for unsuspecting visitors. I did stuff like debating and drama and deejaying on campus radio, and I’ve been an instructor and presenter alongside my writing and editing career. I’m pretty comfortable with public speaking. There’s a spark you get from a live audience that’s unlike anything else.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

All I want to do is write books about interesting characters doing interesting and at times unexpected things. That’s it, really.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Again, this isn’t something I think about, at least not in connection with myself. No question, there are writers out there doing influential, world-changing things with their work—interrogating culture, dismantling stereotypes, posing key political and philosophical questions, amplifying stories and voices that have historically been stifled. I’m not one of them. I’d just like to write stories that keep people reading and that make them feel something.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Editors are my tribe. I adore working with them; they are like ER doctors for manuscripts. My editor at NeWest Press, Leslie Vermeer, and I co-wrote a blog post about what it’s like for one editor to be edited by another. Outside editors are indispensable. It’s the interior editor, the one battling the writer inside my head, that’s the troublemaker.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

BIC: bum in chair. Writer, instructor, and retreat organizer Ruth E. Walker handed me that nugget years ago. Get your bum in the chair, and do it regularly. That’s most of the battle. Once you’re there, the writing will come.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I usually set weekly and daily goals, but they vary a lot depending on what else is going on in life. Right now I’m aiming for three one-hour sessions a week on my new novel. In the past, I’ve set page quotas. A few months back I did adopt one routine, which is to do accountability check-ins with another writer. All we do is message one another to say “did my first session,” “did my second,” etc. There are many, many days when I wouldn’t write a word if not for that arrangement.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

It’s only now, chipping away at my third novel while promoting my first and getting ready to revise my second, that I’ve begun to feel stalled. How to get going again? Probably I should read the answer to this question in all your other interviews! More and more I’ve been turning to non-verbal inspiration, like music. I’ve listened to Radiohead’s In Rainbows scores of times hoping that the trance it puts me into will result in some number of words on the page. I’m also collecting images that match the time frame of the story I’m struggling with and that make me think of the characters. I use Padlet, a free app that lets you to create a corkboad you can stick pictures on. It’s like Pinterest, but private.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Salt cod. My dad would always have leathery slabs of it soaking in a pail just inside the back door. This was in rural Cape Breton. When we’d come crashing in from the school bus, leaving the fresh air behind, it was often the first thing we’d smell. That and his hand-rolled Player’s cigarettes.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music for sure. There have been times in my life, like back when I deejayed or tinkered with the piano or played (rudimentary) bass in a basement band, when music has meant as much to me as books. Film is a huge influence too. Less now, when movies are all about comic book characters and merchandise, but good films, like gritty 1970s movies or classic screwball comedies or really scary horror flicks—they are hugely inspirational.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

That is a list I can’t begin to compose. I read all the time, and nearly everything feels important while I’m reading it. I try to read widely. I gravitate toward Canadian books more than anything, but I try to keep up with works from other countries too. Fiction and non-fiction. Well-written literary works and fun genre stories. Books mostly, but magazines as well, and blogs sometimes.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Go to England. I did a master’s in English literature, but I’ve never set foot in England. I want to see the moors and the Cornish coast, the hills and dales, all those places I’ve only ever read about.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d have given just about anything to sing well. To be a great, belt-it-out singer like Aretha Franklin or maybe Janis Joplin (without the drugs and untimely death). Though that’s not really what you asked. I guess if I hadn’t become a writer and editor, I’d have been a librarian, ideally in a bookmobile. Books would have to be involved.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Part of it, probably, was growing up in a rural area where there wasn’t much to do. I remember being bored a lot except for when I was reading, and writing seemed a natural extension of reading. Part of it was having little money. There weren’t going to be lessons of any kind, or entertainment that involved fees. Writing cost nothing and it was absorbing and it gave me a break from reading. It whiled away the endless Sunday afternoons. I wrote stuff from such an early age that I guess it just stuck.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I really enjoyed Karen Hofmann’s linked novels What Is Going to Happen Next and A Brief View from the Coastal Suite. And I was transfixed by Deep Water, a 2006 documentary about a sailing race that is more character study than adventure film (though there’s plenty of adventure).

19 - What are you currently working on?

My third novel. It’s coming out in such hiccups (see question 11), but I’m doing my best to keep at it. It’s about childhood friendship and music and betrayal, and about the fallibility of memory, how impossible it is to ever know the truth of things.

July 26, 2022

Spotlight series #75 : Jamie Sharpe

The seventy-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring something something Jamie Sharpe.

The seventy-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring something something Jamie Sharpe.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day and Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek.

The whole series can be found online here.