Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 123

June 16, 2022

Spotlight series #74 : nina jane drystek

The seventy-fourth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek.

The seventy-fourth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel and Winnipeg poet Julian Day.

The whole series can be found online here.

June 15, 2022

Amanda Larson, Gut

When Anne writes of desire, she does not write in gender, but rather the lover and the non-lover, the desire and the desired. For her, fear of possession is legitimate; desire splits and splits, gives way to deluge. Is melting a good thing?

*

In which case, the flood is something that happens to you, upon you. I don’t recall that sensation when I when I was younger; I remember capitalizing on absence, speaking of those other than myself, lowering a risk. It was good, there, to be defined by a man, to be wavering at a grey-lit bar at sixteen, my being confirmed by the sheathe of his palm stitched to the small of my back. that was what my love looked like, Anne. It was not the same for him.

*

For there to be a flood, there must be a landscape that is flooded, fields to be clogged and relics to be ruined, but I did not have a house, or a landscape. I feared another so wholly that I would become whatever it was they wanted. (“II: Spring”)

New Jersey poet and New York University student Amanda Larson’s book-length debut is the stunning Gut (Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2021), a lyric triptych writing and examining the aftermath of sexual trauma. “That was how E.’s mind was then,” she writes, early on in the collection, “and remains today. / I held onto his goodness for so long. It blew up in the / presence of the man who did those things to me, magnified / as a microscopic image, a cell giving way to a deranged / shield of white on the pupil, and with my hands erratic / around the zooming knob; I looked, and drowned.” Set in suite-sections “II: Spring,” “III: Summer” and “I: Fall (Timeline),” Gut is a book of accumulations, a lyric chain-length of interconnected, sequential prose poems interspersed with occasional breaks of rhetorical question-and-answer sessions, akin to a Greek Chorus within the bounds of her examination.

Q: The night of, the televisions broadcasted a story of the fires in California. The leaves and the branches appeared on fire, culminating in the trunk, the forest, and then an entire town.

Can you only be annihilated once?

A:

A burn is a singular event, manifested on the flesh; its change is linear and permanent. The image of the fire recurs, a constant.

The questions, as much as to anyone, turn back to herself, and the possibilities of how one endures, and begins to move beyond such an experience, one that is held as an impossible point. “That is to say: I would function under certain deliberateness,” she writes, “a type that I could remember and understand. I would not have called E. at 5:30 in the morning after another man had tried to rape me. I would not have done it regardless of the sky, how it was then, the color of a bloodied gum.” Composed as lyric elegy/essay, Gut dismantles and interrogates the direct experience and aftermath of her assault, writing a philosophical approach to violence, articulating it, and seeking to open the mind after and potentially beyond trauma. Composed as the opposite of silence, the poems here are startling, even shocking, writing a violence not described but experienced. Gut is composed as an interrogation, including of herself, that refuses doubt, self-recriminating or guilt, but seeks to turn over and across a series of questions for the sake of an astonishing clarity. “I knew I was going to do it before I did it.” she writes. “How badly I wanted some part of me to be understood as decadent, / or unforgivable.”

The questions, as much as to anyone, turn back to herself, and the possibilities of how one endures, and begins to move beyond such an experience, one that is held as an impossible point. “That is to say: I would function under certain deliberateness,” she writes, “a type that I could remember and understand. I would not have called E. at 5:30 in the morning after another man had tried to rape me. I would not have done it regardless of the sky, how it was then, the color of a bloodied gum.” Composed as lyric elegy/essay, Gut dismantles and interrogates the direct experience and aftermath of her assault, writing a philosophical approach to violence, articulating it, and seeking to open the mind after and potentially beyond trauma. Composed as the opposite of silence, the poems here are startling, even shocking, writing a violence not described but experienced. Gut is composed as an interrogation, including of herself, that refuses doubt, self-recriminating or guilt, but seeks to turn over and across a series of questions for the sake of an astonishing clarity. “I knew I was going to do it before I did it.” she writes. “How badly I wanted some part of me to be understood as decadent, / or unforgivable.”June 14, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Katie Peterson

Katie Peterson

is the author of five collections of poetry, including

Life in a Field

(2021), chosen by Rachel Zucker for the Omnidawn Open Book Prize. Her previous collection,

A Piece of Good News

, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award. Her work is forthcoming in the Harvard Review, Poetry London, and the Yale Review. Her collaborations with Young Suh have been shown nationally and internationally, most recently at the Datz Museum in Gawngju, South Korea. She directs the Creative Writing Program at UC Davis, where she is Professor of English and a Chancellor's Fellow. She was born in California.

Katie Peterson

is the author of five collections of poetry, including

Life in a Field

(2021), chosen by Rachel Zucker for the Omnidawn Open Book Prize. Her previous collection,

A Piece of Good News

, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award. Her work is forthcoming in the Harvard Review, Poetry London, and the Yale Review. Her collaborations with Young Suh have been shown nationally and internationally, most recently at the Datz Museum in Gawngju, South Korea. She directs the Creative Writing Program at UC Davis, where she is Professor of English and a Chancellor's Fellow. She was born in California. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Oh my god I was so young and then I had to take myself seriously. At that point in my life, the publication of that book made plain that I didn’t really want to write a critical monograph (I was in a literature doctoral program). Some poets do both of course and I’m not dead yet, maybe I’ll write a critical book (see below). But publication meant permission, which is sad, because shouldn’t a person who wants to be a poet give themselves their own permission (by the way, the title of my second book is PERMISSION so I guess I was working that one out). The year my book came out I got my degree and keep teaching at Deep Springs College, which is in remote Inyo County, California. I loved the job but I was so far away from everything that had grounded me and I felt very alone in poetry, very solitary with it.

My most recent book Life in a Field is a collaboration with my partner, the photographer Young Suh. The writing emerged during an extended collaborative process between the years 2014 – 2016 that culminated in a show of our work together titled Can We Live Here? Stories from a Difficult World at the Mills College Art Museum. I can’t imagine this work without Young’s influence and presence, I think the book arrived in my imagination as the telling of a story to the child we didn’t have (we have her now). A fairy tale, a parable, an explanation of the real world that needs to hold the real world at a distance in order to say something about it.

I spend so much more time with visual art – specifically with photography – than I used to. I wanted Life in a Field to move slowly, as I suppose I want time to move more slowly now in the middle of my life. I embrace the fantasy of slowness that poems sometimes have, the fantasy of holding things still, I am interested in indulging it rather than poking the obvious holes in its lies. Photography has made me love poetry more for the qualities they share – an aspirational stillness, a lushness in the moment, a dream of coherence, a fantasy of accuracy.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I don’t think I did. I loved stories first. The first stories I wrote were in a fairy tale structure about ordinary people in an unenchanted world. I remember that I wrote a story about a man who wrote a woman love poems, and the woman responded by eating the poems. I liked things like that, a tweak inside the ordinary, a vein of strange in the rock of the normal. But I couldn’t move past a statement of the conflict. I didn’t like resolving the conflict. I didn’t like making things happen, I liked making them unhappen. I’d write scenes and no one would leave the room.

A beloved English teacher gave me Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poetwhen I graduated from high school. I wonder if I loved the vocation of the poet first, the sense of purpose and the agility of mind. I used to recite that passage, “learn to love the questions themselves, like locked doors and books written in a foreign language,” all the time to myself. I knew it was armor; I knew then the usual world is determined towards answers. And it seems now the world is even more determined, that questions are even less valued. There is so little time and space for our wandering.

I was a bright schoolgirl and good at forms so every time I was assigned a poem, I excelled at it. What I respected, early on, was that the moment you went into form consciously, it turned whatever sincerity I brought in on its head. My sentiments became rhymes; my thoughts turned into stressed and unstressed syllables. Form dissected my certainties. Even if the poem sounded or looked successful I knew better – the poem showed me how little I knew about all the certain statements I brought into it. One reason people like Bishop’s “One Art” is it presents a credible humility, credible because the voice of the poem thinks she’s figured something out and all her figuring is a disguise for the opposite. I kept going back to poetry because I couldn’t fool poetry, however smart I was, poetry always knew more than me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I feel like I am always working on something, if not on the page, in my head. And I have left certain projects behind like half built houses or abandoned ships, and I feel no better about that than I do about breakups with humans that have ended poorly. In my writing life I have to live alongside my mistakes. But at a certain point you draw a line and you are working towards the completion of something rather than experiencing its promise. I am in an uncomfortable place right now, maybe 7/8 of the way to a book and it makes me long for the writing, poem by poem, I was doing a while back. There is nothing like writing if the poems are close by, it is a grand feeling, nearly luxurious, like the night before Christmas or something like that.

I used to write poems at my desk and now I do them anywhere – having a child has made me more flexible and more tenacious. I often think about a poem as I drive Emily to school and try to catch it on the way back, or in the driveway, which makes me a distracted drop-off parent sometimes, which is interesting to me, why do I want the poem to get in the way of dropping my daughter off, what am I trying to do with that. Also, is that moment of our separation the poem of my life right now that I am avoiding? Maybe so.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually I begin with an image, though sometimes a bit of overheard speech (I guess I think overheard speech is also an image, if you get down to it). I often write poems in a series, which I always think about more as repetition than narrative – I like the spiritual activity of repeating a gesture in the mind after it gets memorized or stale, like prayer, and trying to refresh it. Or it might be true that I repeat an act of mind because I don’t understand it yet. I don’t think I’m ever working on a book from the very beginning. I like to work piece by piece.

But it is true that the more I have finished books, the more I see, earlier on, in the process. For example I was very sure this summer of the structure of my next collection and then over the course of the fall I lost faith in that structure and had to try again. But in order to see it, I had to put the whole thing together. I think a lot of people do this. I guess I would say that I used to think I could develop a less fixed and judgmental mind, that I could stay in a state of “negative capability” for longer, stay in process longer. What I’ve discovered is that part of my process is making a judgment, seeing it’s wrong, changing it, making another, maybe getting closer, changing it, making another, maybe being more right, or more likely, having exhausted all but the most necessary option for the book. When I revised both of my last books, A Piece of Good News and Life in a Field, I wanted them to live as lightly on their feet as possible.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I used to love readings and relish them. Now I love them and they freak me out. Why? I have no idea why. I just get really scared right before, even online. Like I’m going to mess something up.

And I do mess things up! More than once I’ve had the experience of reading a poem the way it should have been written, not the way I wrote it on the page. Ouch. But the living voice, to me, always has more authority than the page, sometimes it just pops up.

Can’t lie, virtual readings can be thrilling because you see people’s rooms, because it feels so shoddy and secret. I think I have a romance of making lemons out of lemonade, maybe I’ve enjoyed the difficulty of the virtual reading for this reason.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Love and violence are hard to talk about. I’m interested in all sorts of things that are hard to talk about. I think poetry’s less involved in saying the direct truth about those things than in representing the difficulty in approaching them. Our world seems terrified of love and dead to violence, and I guess I’ve been wondering lately why this is and whether it’s going to last and what it has to do with the language of our time. I’m always wondering whether this sort of thing is a problem of right now or something true through time. I long to be connected to other times and places, to guess or intuit what this moment shares with other moments from long ago or might with future moments.

There are many other people interested in the same set of questions, but I think most of them prefer to ask it in cultural terms – “intergenerational trauma” is a phrase I hear and think about. Many people are asking these question as immigrants or migrants, or concerning race, or sexual orientation. I think of my trans friends and how they have to ask every day why on earth anyone would want to do violence to them just because they are human and themselves. Or of the way my partner has experienced more aggression in public in the last year because he’s Asian. I don’t know what it would be like to be American and not care about the murder of George Floyd.

There is a passage in Henry David Thoreau’s essay on John Brown where he considers who people are to each other in American culture – he’s imagining his way into how people must have felt the day after John Brown was killed in 1859, since some were sympathetic to his cause and others reviled him. He talks about how people must have been more than strangers to each other in the wake of that historical moment, and of other similar moments – that they were like aliens, utterly strange to each other, on the eve of the Civil War. I think about that passage and that predicament a lot these days – this sense of a broken understanding between people – and I wonder if it will change in my lifetime, and, because I refuse to idealize things, whether it was ever different.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t mind that poems feel like small things. They bring us closer to what’s true and what matters by refreshing our senses with imaginary, lucid activity.

Poetry prefers knowledge to information. It prefers music and verbal patterning to facts. It tells the truth “slant” for a reason – it is interested in truths that are difficult to share.

The role of the writer is to keep refreshing our access to what’s most true which is the reason why love poems are so important, because they argue that truth and love have something to do with each other.

I think the role of the writer is to help us survive by bringing us closer to what’s beautiful, and by reminding us how our relationship with what’s beautiful invites us into a thousand amazing conversations, about justice, about nature, about grieving and sorrow, about weather and time, and home and love and other matters.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ll take any help I can get. The editors I’ve worked with have been angels. Advice can be useful even if you don’t use it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

If you keep making the same mistake, make a different mistake.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to collaboration)? What do you see as the appeal?

I was living with a photographer for whom English is a second language and Korean the first. But it was even more complicated than that, he’s a photographer! There’s a line by the poet Rob Schlegel – “language is not my first language.” We had to find a way to communicate if we were going to stay together. You can fall in love with a lot of people but if you want to spend your life with someone you have to develop a language together. What was a necessity in my life became the necessary conditions of my work.

Collaboration is not a picnic. As I say this I remember that Young and I made a movie about a man and a woman having a picnic with a donkey – with an actual donkey. The donkey messed up every shot we planned, though we also planned the donkey’s messing up into the shooting script. When I say “collaboration is not a picnic” I mean it’s not a unity, it’s not a perfect marriage, and if it’s going to be interesting it can’t stay play or process forever. Collaboration surfaces misunderstandings and ruptures, it reminds one always of the distances one cannot travel. It can’t hide a power struggle even if it converts that into the making of something.

The appeal is that it’s real. Forrest Gander’s book Twice Aliveuses the word “combinatory” to describe this intuition, that one’s perceived aloneness is at least in part an illusion. I am not sure whether we are truly alone or truly collaborative beings. I do not know the nature of the great web of things, the way we might be connected to animals and plants and the earth, but I know I am involved with the question, sleeping or waking, paying attention to it or not.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I used to write in the mornings, early as possible – I wrote all of my third book The Accounts in the early hours – and I loved that schedule. Now I write whenever I can. I used to write down all my dreams, but now my daughter comes in and tells me hers before I have time to remember mine and isn’t that just like a poem, itself, and shouldn’t we just leave that there without comment?

So I start messy, her and Young awake, and breakfast and everyone getting out the door, grabbing a thought or a headline or an intuition, trying to organize myself, check in with the members of my family who don’t live in my house by phone, maybe texting a friend, trying to get to coffee, but maybe remembering an image from a dream, or maybe starting a fight with Young about politics or whose turn it is to do something. Right now, listening to Emily say things about the world, or tell stories with her made-up characters, like the Windy Robot, who puts metal leaves on the trees. Just totally messy all morning. Maybe a poem surfaces out of all of that, mainly not.

The best part of the day is walking. I love to walk, I’d walk two or three hours a day if I had time. Lately (last four years or so) the poem or the revision comes out of the walk.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Cooking makes me feel like I am temporarily in control of making something that is supposed to disappear. It’s just like poetry or it’s not like poetry at all, I guess. Baking is not my gift – I think it appeals to qualities I don’t have, like making a complete and unbroken whole, or setting up and executing and savoring a process of waiting. Though I am not a stranger to delayed gratification (is there any other kind?) I like to stir something in a pot and look at it while my expectations change and come to fruition. So lately I like making Italian recipes (Marcella Hazan) and Korean food, at which I’m a rookie. I like reading cookbooks too, and I like reading about food (Olia Hercules, Madhur Jaffrey, Ronald Johnson).

I never feel better than on a road trip. Those have been harder to take. But I find if I drive myself around or go up to a very high place, or go to the ocean or to a weird town somewhere, something often breaks apart in me that needed to be broken. I love what I call the “lost feeling,” which you might find in a Tarkovsky movie or in a poem like “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg” by Richard Hugo. The last time I had the lost feeling was on a road trip this summer. We were in Kingman, Arizona. The train rolled by right outside our motel in the middle of the night, and we ate ramen from the gas station, and watched the last night of the Olympics and I swear I was in heaven, I swear I cried of happiness.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My mom used to put a bay leaf from the Spice Islands jar in a tomato sauce she pulsed in the blender with an equal measure of carrot, celery, onion, tomato. We seemed to have it forever in the winter for a decade but now it’s gone. If you could get it back for me I’d give you everything I have except Young and Emily. Ah, I am 47, my home is still my mother. Eucalyptus, Monterey Pine, rosemary hedges woken up by the Bay Area’s marine layer.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I love the ballad tradition, Irish folk music, all folk music, all forms of country music from bluegrass to Miranda Lambert. John Prine, Townes Van Zandt, Iris DeMent, Gillian Welch, Rhiannon Giddens. Women’s vocals from all countries. I love hearing the voice tell a story in verses and I love it when old songs feel new again. The Smithsonian recordings of Elizabeth Cotton have been in my ears pretty deep for a few years.

Jesus from the New Testament and all his paradoxes. Sacred texts like the Bhagavad Gita, the prayers of St. John of the Cross, Nietzsche’s aphorisms, but less for the meaning than the rhythm and the style.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I just did a few podcasts for my graduate workshop, titled “Putting Poetry at the Center of Your Life” and “Why You Should Read,” both so moralistic, I should be ashamed of myself! The third one is going to be called “The Self in Poetry.” I wanted to just try to say what I thought about some basic things at the center of poetry and I didn’t want to do too much research, or planning, I wanted it to come out like I was just talking to a friend of mine about things, like a California version of poetry Socrates. So I didn’t plan the talks out, I just sat and wrote them, remembering a poem or poet or book when I got to it, instead of taking notes. The writers I mentioned again and again – Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Fanny Howe, Flannery O’Connor, Simone Weil. Catholics, New Englanders, converts.

For years, I taught what we used to call Western Civ, or the Classics, or the Great Books – Plato’s dialogues, Homer in translation, Nietzsche, Shakespeare (seen as a writer of ideas), Jane Austen, James Baldwin. This kind of teaching, its limitations and its uncertain legacy, matters to me still, after doing so much of it. It wasn’t what I planned – it was the job I got, coming out of grad school, and a fortunate fit at that time. I continue to be involved in educational projects that do this kind of work for a reason, even though it is more than out of fashion. It was the method, of using books of this kind almost as workbooks for the soul, that mattered as much as the texts themselves. I still think this way about books – I want to do critique, to see what’s wrong with arguments, but I learned the pleasure of following an argument itself, and the artfulness of knowing the mind of a book well. The idea of the classics might be over, but I learned something so real from this kind of reading about what reading is for. I am so confused about what we’re doing in education if we’re not trying to raise responsible adults, or cultivate free individuals. I also just love books so old you can kick them around a bit.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Life stuff – I’d like to do the pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayo in New Mexico with my friend Sarah, I’d like to go to Jeju Island in South Korea, I’d like to go to the Isle of Skye, and the Faroe Islands, and I’d like to go back to the Aran Islands, where I went in 2015. Iceland. But I’d like to do just about all of these things with my daughter, and she is only four, so it’s ok for them to wait.

When I decided not to turn my thesis on Emily Dickinson into a critical book I think I also turned away from the idea of writing a prose book at all, but I’ve been wondering lately whether I’m ready to return to the idea of writing a critical prose book on poetry. I didn’t ever want to write anything research-driven, or archival, or footnoted. After years of getting to say what I think in the classroom, I am getting closer to knowing what I think. I think I could only write a critical book if I could first speak it, put it in my voice, so I am hoping these podcasts for my class help me figure out what to do.

I love swimming. I’d like to get really comfortable ocean swimming.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I just think I was always going to be a teacher. Aristotle talks at the beginning of the Ethics about what makes people go – in the sense of what makes them happy. He says most people are motivated by love of pleasure, that’s what makes them happy. But there are some people motivated by love of understanding. I have tried over the course of my life to be motivated by love of pleasure, or love of other people (i.e. an interest in community). I love pleasure and I love other people but it’s not my thing, I guess I’m terminally attracted to knowledge. And I love watching other people learn things, come to an understanding. I love giving people the freedom of books, that power. I love pointing people to their inner teacher. And I do think teaching is different than writing, I don’t think writers have to be teachers. I think I would have been a teacher if I had never been a writer.

But let’s say you could remove all of that or imagine it away, that I wasn’t a teacher, either? I’m telling you, I’d just want to be a singer. A Rickie Lee Jones or a Joni Mitchell, an Aretha Franklin or a Leonard Cohen. A Miranda Lambert under the lights. A Beyonce with the outfits. I’d want to make it big when I was young, make a mess, then make a comeback with an album of covers so unexpected you’d think of me not just as a chanteuse but as a sentiment-curating diva singing your sadness on your behalf. I’d be fine doing my time on the road or a lackluster residency in a dive as long as I broke a few hearts a night. I’m compelled by the idea of having to repeat something a zillion times like it was the first time I ever did it.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I think it was the easiest thing to keep secret – it didn’t need an audience. It was something I could do without the approval of what seemed to me like the general population. It was only much, much later I thought about a writing “community” and it still doesn’t come naturally to me. I loved that poems began in such a secret place, and then, like a shirt turned outside-in, seemed, if they were good, magically transmissible. I still love this about poems – that they go in in order to go out, that they embrace the partial telling of a secret not to expose the material truth of that secret but to tap into a language just under the surface of admissible speech. When I was young, I could write and write and not show anyone anything and no one could tell me I was being ridiculous.

And I had an aptitude for music, and I was a pretty good painter, and for a time I was gifted enough as a stage actress to play some wonderful roles, but I wasn’t nearly as good as any of that as I was at telling stories. I could forget about the world, telling a story. The story was all that mattered.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Romance in Marseille by Claude McKay. It’s some of the best, most delicious prose I’ve read in years. It’s about a West African sailor named Lafala who’s had his legs amputated after trying to stow away to America; he receives a settlement from the shipping line and courts a prostitute named Aslima. Nothing works out for anyone but the plot keeps returning to the question of whether we can save each other, a question I really care about. It wasn’t published for decades because people worried the content was offensive. McKay was Jamaican, better known to us as a poet. It’s a wild, joyous book – the descriptions of multicultural Marseille are so vivid.

I watched Bright Star, Jane Campion’s movie about John Keats, this fall, after not seeing it for years and it is still as amazing as it ever was, a feast for the eyes and heart.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am close to finishing a collection I might call Fog, History, and Smoke. I started writing it in earnest when my daughter went back to day care some months into the pandemic and I had some time to walk, and then to write – the poems talk about landscapes but I think they’re really interested in this numinous feeling of violence between people these days, like someone’s about to throw a punch.

I also started working on another narrative book, a bit like Life in a Field. It’s about an apartment two families have to share, and how they live together – it’s set in a world in the future in which people have doubled up in apartments, been assigned mandatory roommates. In this future, there are also all sorts of other weird rules – everyone has to move every five years, when you have a child, you have to change jobs, everyone plays a musical instrument. It’s set at Christmastime, but no one believes in Christmas. It’s complicated. I’m still working it out.

June 13, 2022

Qorbanot: Poems by Alisha Kaplan; Art by Tobi Aaron Kahn

GUILT OFFERING

thank you for making me a woman for letting me reside in the book of life inside of which is the pizza shop I was afraid to enter wearing jeans the movie theater I was afraid to be seen at with a boy the shower I was afraid to sing in the chair I was afraid to sit in lest my skirt rise my sex I was afraid to look at till I was twenty-five thank you for teaching me to be afraid of the stranger for making the shoulder something to look over bless you thank you thank you

I was curious to see poet Alisha Kaplan’s name on this past year’s Gerald Lampert Memorial Prize shortlist for the collection Qorbanot: Poems by Alisha Kaplan; Art by Tobi Aaron Kahn (Albany NY: State University of New York Press, 2021), having neither heard of the author (who divides her time between Toronto and Hillsburgh, Ontario) nor the publisher prior to that shortlist announcement (the book subsequently won this year’s award). Titled after the Hebrew word for “sacrificial offerings,” Qorbanot exists as a paired examination of how words and image simultaneously hold and contain memory, history, hope and trauma. The paired threads of text and visuals are set in seven numbered sections, collected and ordered brilliantly to fully adhere to a conversation between works by two separate artists, from the “studies” of painter Kahn—“Study for YMNAH,” “Study for VEIKUT,” “Study for EIKA” and “Study for AKYLA”—counterpointing the “offerings” by poet Kaplan (a number of titles of which repeat through the collection)—“Guilt Offering,” “Peace Offering,” “Masada Offering” and “Offering to the Lost Poet Rosemary Tonks.” The works included and enclosed speak of loss, and possibilities extinguished, as well as those that might still remain.

BURNT OFFERING

The last time my grandmother saw her father, he blessed her and said: Eat whatever you are given and be among the first to offer to work.

Akin to the ongoing work of Canadian poet Anne Carson, Kaplan’s lyrics contain multitudes, but offering as much spiritual as lyrical articulations on history, historiography and faith. Kaplan’s writing exists very much in conversation and collaboration with Kahn’s full-colour artworks (individually created across a span of some three decades, some of which might even pre-date the birth of Kahn’s collaborator), set in dialogue throughout the book, offering insight into faith and practice, offering and sacrifice, furthering a theology that speaks to a faith lived best and fully only through study and attention. As Kaplan writes as part of the essay “AVODAH,” which closes out her contribution to the collection: “This is fact: a sand grain can range from one-sixteenth of a millimeter to two millimeters. And the number of life spans to get there? I try to calculate how wide my hips are, measure with my eyes the dimensions of the hole.” As the back cover offers, Qorbanot

[…] explores the concept of sacrifice, offering a new vision of an ancient practice. A dynamic dialogue of text and image, the book is a poetic and visual exegesis on Leviticus, a visceral and psychological exploration of ritual offerings, and a conversation about how notions of sacrifice continue to resonate in the twenty-first century.

Both from Holocaust survivor families, Kaplan and Kahn deal extensively with the Holocaust in their work. Here, the modes of poetry and art express the complexity of belief, the reverberations of trauma, and the significance of ritual.”

This is a remarkable collection, one that opens, uniquely for a new poetry title, with a foreward by James E. Young, and closing essays by Kaplan, as well as Ezra Cappell, Lori Hope Lefkovitz and Sasha Pimentel. It is as though the creative sequence of call-and-response by Kaplan and Kahn exist as a foundation of study, and the supplemental pieces that surround this powerful and unique collaborative conversation exist to provide a fuller portrait of their work, and everything that surrounds it. As Young writes to close his foreword:

But if a postwar, antiredemptive generation of artists and poets remains averse to recapitulating the cycle of sin-destruction-redemption in the face of massive destructions like the Holocaust, it may still be open to finding some sort of artistic redemption in response to the small losses and micro-destructions of daily life. These are the qorbanot I believe Tobi Aaron Kahn and Alisha Kaplan have in mind as they ask whether their acts of art and poetry can redeem such losses without fully compensating them—or whether it is ever possible to articulate the voids left behind without filling them in. As this volume’s poet, artist, and contributing writers make so clear, the answers to these questions necessarily lie in the open spaces between words and images.

June 12, 2022

Sueyeun Juliette Lee, Aerial Concave Without Cloud

it was easy to form mental pictures

of waves and particles

easy to make certain kinds of predictions

concerning the probable results of future observations

which remained logically consistent

and frequently very useful

yet this picture may be unsuited to describe

certain other types of observations (“the appropriate information in the negative”)

Denver, Colorado-based Korean American poet Sueyeun Juliette Lee’s full-length debut is

Aerial Concave Without Cloud

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), a collection that pulls together the sequence, the fragment and an extended accumulation of hesitations and meditations on solar light and basic theory, broad spectrums and refinement, silhouette and clouds. “it has been said at various times / however that the advent of such / vehicles for thought and certain materials,” she writes, as part of the opening sequence, “the appropriate information in the negative,” “obviate our need for insight / reflecting a misconception / as it occurs in the central value / of the human body // a further misconception emphasizes / craft at the expense of / human longing [.]” Across four sections plus opening salvo, Lee examines depictions of light and space, offering, as well, quotes at the offset by Gaston Bachelard and Ansel Adams. She offers glimpses, composing an assemblage of short poems and longer stretches, writing lyrics against her study of light and consequence, and how it falls where it lays. As she offers as part of her “Notes on the text:” at the end of the book: “I composed the primary materials for this book while in residence at Kunstnarhuset Messen (Ålvik, Norway), Hafnarborg (Hafnarfjörður, Iceland), and UCross Foundation (Ucross, Wyoming). I spent the summer of 2014 in Norway, where the intensely long summer days over the fjord infiltrated my body.” Aerial Concave Without Cloud is very much composed as a book of observation, examining just as much ways of seeing as what might be seen, and the impact of different elements and angles of light, as well as the evolution and impact of time. “In gray light and wind,” she writes, as part of the second section, “the inconstant quarreling turn of it over absent walls. / Then a sudden sleet, shifting. Am I alone. // The pressure of it—the atmosphere here is an intensity of small children, / their insistence.” Or, as the sequence “a pale saturation (in day,” set as the opener of the second section, asks:

Denver, Colorado-based Korean American poet Sueyeun Juliette Lee’s full-length debut is

Aerial Concave Without Cloud

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2022), a collection that pulls together the sequence, the fragment and an extended accumulation of hesitations and meditations on solar light and basic theory, broad spectrums and refinement, silhouette and clouds. “it has been said at various times / however that the advent of such / vehicles for thought and certain materials,” she writes, as part of the opening sequence, “the appropriate information in the negative,” “obviate our need for insight / reflecting a misconception / as it occurs in the central value / of the human body // a further misconception emphasizes / craft at the expense of / human longing [.]” Across four sections plus opening salvo, Lee examines depictions of light and space, offering, as well, quotes at the offset by Gaston Bachelard and Ansel Adams. She offers glimpses, composing an assemblage of short poems and longer stretches, writing lyrics against her study of light and consequence, and how it falls where it lays. As she offers as part of her “Notes on the text:” at the end of the book: “I composed the primary materials for this book while in residence at Kunstnarhuset Messen (Ålvik, Norway), Hafnarborg (Hafnarfjörður, Iceland), and UCross Foundation (Ucross, Wyoming). I spent the summer of 2014 in Norway, where the intensely long summer days over the fjord infiltrated my body.” Aerial Concave Without Cloud is very much composed as a book of observation, examining just as much ways of seeing as what might be seen, and the impact of different elements and angles of light, as well as the evolution and impact of time. “In gray light and wind,” she writes, as part of the second section, “the inconstant quarreling turn of it over absent walls. / Then a sudden sleet, shifting. Am I alone. // The pressure of it—the atmosphere here is an intensity of small children, / their insistence.” Or, as the sequence “a pale saturation (in day,” set as the opener of the second section, asks: What do you wish to forget?

Becoming attuned to the monaural surround drives you to dehisce into the artic pale above, mirrored in a traceless horizon. This space “of blue” eats up the limits of the human body—my organs coalesce instead as a slow pulse of asymmetrical gray light.

In deep saturation and swarm, in this ultramarine aeriality. What storm.

Breathe lightly across my face. My cheeks are already languid floes across my features. Peer into me with the warmest winter ice I have never touched.

to reach

The third section of the collection is the expansive “Relinquish the Sky,” a section that incorporates photographs and dance, offering the centre of what the press release suggests: “Aerial Concave Without Cloud is a collection of poetry steeped in the bluest apocalypse light of solar collapse and the pale, ghostly light of personal devastation and grief. Through a combination of academic research and the salp’uri dance form, Sueyeun Juliette Lee channels and interprets the language of starlight through her body into poetic form. Through deep conversation with this primary element, Lee discovers that resilience is not an attitude or posture, but a way of listening.” This section focuses beyond the movement of light and space to include the body, offering forms of dance and conversations around resistance, ghosts, posture, loss and ancestors. “I began my inquiry into light,” she writes, as part of “Daylight, No Grief,” the opening poem of the third section, “simply: can I decipher a similar capacity to translate and speak the light with my living human body?” She writes of resistance, and the orphan, resisting, as well, the very notion of the orphan, disconnected completely from that of the mother, as offered through North Korean propaganda: the revolutionary-as-orphan, the simultaneous broken link in the chain of both family and history. “To speak with light is to encounter the trace of the originating mother body through its lost child. An orphan being, the light reaching us is jettisoned without turning its head back home.” What does the light bring, she asks, and what might it reveal? And what might it take with it once it finally leaves? The light she depicts and shapes is complex, revealing and, at times, dark. Or, as the poem “Northern Light” begins:

From 2015-2016, I traveled in sub-arctic and arctic coastal environments in order to observe strong variations and durations of light. I traveled in the fjords of Norway, into the arctic circle, and meditated alone in the howling blue-white expanse of Iceland’s northwest fjords and frozen plains.

I was anonymous and alone, among kind but ultimately indifferent strangers. I often spoke to and saw nobody for days.

(fjord water lap at a rough gray shore)

Our bodies require light.

I seek the opening of understanding.

What is being said and said again with me. What am I now saying, too. If my skin were composed of eyes, what would it see. If my body were a gigantic listening drum, what would I perceive. What do they want to pour into me.

June 11, 2022

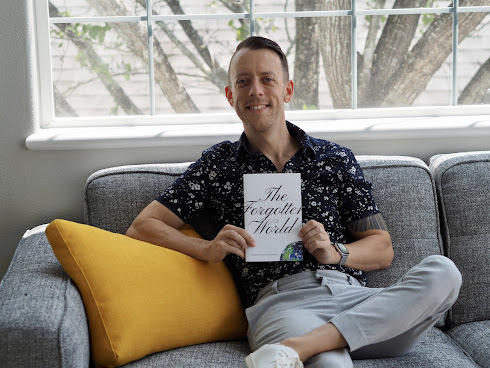

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nick Courtright

Nick Courtright is the founder and Executive Editor of Atmosphere Press. He is the author of

The Forgotten World

, about Americanness and identity in a vast global culture,

Let There Be Light

, called “a continual surprise and a revelation” by Naomi Shihab Nye, and

Punchline

, a National Poetry Series finalist. His prose and poetry has appeared in such places as The Harvard Review, The Southern Review, Kenyon Review, Boston Review, The Huffington Post, The Best American Poetry, Gothamist, and SPIN Magazine, among dozens of others. Find him at nickcourtright.com.

Nick Courtright is the founder and Executive Editor of Atmosphere Press. He is the author of

The Forgotten World

, about Americanness and identity in a vast global culture,

Let There Be Light

, called “a continual surprise and a revelation” by Naomi Shihab Nye, and

Punchline

, a National Poetry Series finalist. His prose and poetry has appeared in such places as The Harvard Review, The Southern Review, Kenyon Review, Boston Review, The Huffington Post, The Best American Poetry, Gothamist, and SPIN Magazine, among dozens of others. Find him at nickcourtright.com. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I think my first book, Punchline, which came out in 2012, gave me a sense of relief. Not validation necessarily, but I think it freed me to write when I wanted, rather than write as if life depended on it. My newest book, The Forgotten World, is my third, and by far my most personal book, and my book most rooted in the real world, rather than any sort of metaphysical space. Being the Executive Editor of Atmosphere Press, which is not tied to the academic calendar, gave me the opportunity to explore the world more fully, and that exploration made for a book set in places, rather than in the one place of the abstract.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually came to fiction first, back in high school, but poetry eventually became my mode. I was more interested in ideas than I was in telling stories—the invention of characters and plots started to seem like a weird game to me, whereas with poetry I could run straight at a problem, whether it be love, the universe, or culture.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I used to write prolifically, but now I take my time. My first two books were released two years apart, and it wasn’t until seven years later that I had a third. I wrote probably three books worth of material between that second and third book, though—I was writing whole books and chucking them. I think I needed to go through that process to get something that felt most authentic. As for drafts, they are usually 90% of what the final will look like, but that other 10% can take eons to figure out.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ve done both, and for The Forgotten World it became clear along the way that I was writing a travel book and a book about the intellectual struggle of being American while not in America, and respecting cultures that have been mistreated by people who look like me. Once I realized that that was the subject matter I felt compelled to write, I just had to spend the years it took to go the places I needed to go to learn. This book is a product of years of feet-on-the-ground research in a way my others weren’t.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings, and I think going on tour for my first two books changed me substantially as a writer. I realized that I wanted to entertain and be accessible on a first listen, rather than just write poems that have to mulled over many times in quietude. I always imagine my poems as being read aloud, though some of them are better suited for this than others. But connecting to the random folks you find in an audience became a key part of my vision for the type of poet I wanted to be: engaging and challenging, but very much not elite.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think the question of accessibility is a major item, and what is the goal of poetry? Why do we do it? I believe that writing is mostly something we do for ourselves, even if we have big goals of connecting to others—the act itself, the pleasure of refining one’s work…so much of it is just a hobby to enjoy, with the hope that someone else enjoys the product being secondary. In my PhD we often discussed matters of the lyric, “the overheard,” etc., and I do buy this idea, though lyric can be both navel-gazing and also a means for intellectual problem-solving. I think poets, given the economic limitations of the art (so long as their output isn’t connected to career advancement in academia) are freed to be their own souls.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Connected to the previous answer, I think one of the greatest roles of writing is to make the writer a more satisfied and content person. People often look to the value of a writer in relation to a reader, but I think the contrary view of what the writing does for the writer is more interesting. If all these writers weren’t writing, would they be less fulfilled individuals? Of course, the role of the reader is where this question would usually go, but as someone who helps writers every day with Atmosphere Press, it’s the satisfaction that writing can bring an individual that is at the forefront of my mind. Writing as art is a public service to the creator as much, if not more, than it is to the outside viewer of the creation.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both, haha. It’s always tough to hear the thoughts of a good editor, because a good editor will challenge the writer. But…you’ve gotta hear those thoughts, because they’re going to help the work. You don’t have to work with an outside editor, but it’s almost certain that you won’t see everything your work has to offer.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

From Nobel economist and psychologist Daniel Kahneman: no problem is as important as it seems when you are thinking about it. It helps keep things in perspective, and keeps the anxiety from going crazy. All things are transitory, and the sun is only too bright when you are staring directly at it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

My main art form nowadays is writing emails. That’s my primary genre, haha. I try to put a little of the poetic in there, though.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t keep a rigid writing routine, other than the aforementioned emails! A typical day begins for me with coffee and work at around 6:20am. Bright and early!

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books of poetry. That’s really the key thing that gets my mind in the mode to write poetry. That and place, but really, it’s just finding a book of poetry that inspires me to write. They are pretty hard to find, so when I get hold of one, I’ll read it again and again. Recent stars for me were by Anders Carlson Wee, Kaveh Akbar, and Bianca Stone.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Diesel exhaust in the winter. Reminds me of having to ride the bus to school in Ohio in January. I’ve lived in Austin, Texas for nearly twenty years, but every time it’s cold and I catch a hint of this smell, it takes me back to childhood.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’ve been inspired a ton by science, and by all of these mentioned things. The world is the filter through which the coffee of all poetry must run. That’s an absurd sentence, but you get what I’m saying.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Well, my fiancée Lisa Mottolo is the most important poet in my life. No doubt about that! She’s a great inspiration, and her book will be coming out in 2023 with Unsolicited Press. It’s gonna be awesome and devastating. Just on the literary front, though, I’ve always found kinship in Robert Bly, Federico Garcia Lorca, and the Bhagavad Gita, and my PhD work was on Whitman. These have all had a big effect on me. Emily Dickinson took me an eternity to comprehend in the slightest, but her genius is remarkable.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Gotta get Antarctica and Australia. Those are the two continents I still need to see. I’m also psyched to be a grandparent, but since my kids are 12 and 8, I’m good waiting another twenty years, haha.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I was a professor for a long time and thought that was what I was going to be, until I somehow found myself the Executive Editor of a successful publishing company. Weird how life does that. If I’d gone a wildly different route, I think I would have been an architect. Which is basically just poetry, except for buildings.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Had no choice when I was young: even when I was in elementary school I was always writing stories. Writing picked me, not the other way around.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Wine Simple by Aldo Sohm. Of course, this isn’t a literature book, but as someone who was totally ignorant about wine but wanted to learn, this was the perfect way to get started. Hard to say the last great film I saw, but I will mention the Italian film La Grande Bellezza as a great work I come back to again and again. It is a piece of literature.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working hard on the most ambitious artistic undertaking I’ve ever pursued, and that’s running Atmosphere Press. There’s always so much to solve, so many processes to refine, so much magic to witness. It’s a creative act every day, and the satisfaction I get from designing a workflow that will help my team and help our authors…as crazy as it sounds, it’s no different than landing the right ending for a poem.

June 10, 2022

Steffi Tad-y, From the Shoreline

Water

Before you could talk, you swam,

took up residence

in water

To decipher if there is life out there

the first thing

astronauts look for is water

It seems in order

to live a river of stars

we trade for a roadhouse of startles

What is it

The hush that hardens you and me

over time

Hear water gushing

over a grandfather’s

scraped knee

Hear water like hunger

lacing its shoes, rallying

on a bright spit-laden street

The full-length debut from Vancouver-based poet Steffi Tad-y, following chapbooks from Rahila’s Ghost Press and Frog Hollow Press, is

From the Shoreline

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022), a collection of sketched-lyrics of gestures, pause, halts and clipped phrases. “What else can I tell you?” she offers, to close the two-page “Gising,” a poem set as the second in the collection. “Let us go. // There is side-street parking. / The ticket machine // looks like a pair of binoculars / across an orchid mural. // Keys & raincoat are on the table. / I have been late all this time.” Set in two numbered sections of short poems, there is both an immediacy and meditative quality to her observational lyrics on interiority, writing poems that speak carefully, occasionally pausing to hold breath. She writes of speculations, and shortness of breath, connecting wide swaths of thoughts with deceptive ease. “I placed years of words inside a word cloud / as an attempt to sift through / a record of thoughts racing / I prefer as rain on my rubber boots,” she offers, to open the poem “Writer’s Archive,” a poem subtitled “After Joanne Arnott,” “small & wet I can shake off by the door / beside a mop & a red bucket.” The poems are open, working an assemblage of efficient narrative lyrics on rhythm, repetition and orientation, seeking to understand where she is, where she stands and how it is she has arrived, citing language and emigration, and all points between. “I do not know what it is like,” she offers, to open the poem “Elegy from a Wave,” “to lose a beloved to the sea. // Their body found / by watchful eyes // of a fisherman’s tugboat. / The raft it tows // so close to one’s leaving.”

The full-length debut from Vancouver-based poet Steffi Tad-y, following chapbooks from Rahila’s Ghost Press and Frog Hollow Press, is

From the Shoreline

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022), a collection of sketched-lyrics of gestures, pause, halts and clipped phrases. “What else can I tell you?” she offers, to close the two-page “Gising,” a poem set as the second in the collection. “Let us go. // There is side-street parking. / The ticket machine // looks like a pair of binoculars / across an orchid mural. // Keys & raincoat are on the table. / I have been late all this time.” Set in two numbered sections of short poems, there is both an immediacy and meditative quality to her observational lyrics on interiority, writing poems that speak carefully, occasionally pausing to hold breath. She writes of speculations, and shortness of breath, connecting wide swaths of thoughts with deceptive ease. “I placed years of words inside a word cloud / as an attempt to sift through / a record of thoughts racing / I prefer as rain on my rubber boots,” she offers, to open the poem “Writer’s Archive,” a poem subtitled “After Joanne Arnott,” “small & wet I can shake off by the door / beside a mop & a red bucket.” The poems are open, working an assemblage of efficient narrative lyrics on rhythm, repetition and orientation, seeking to understand where she is, where she stands and how it is she has arrived, citing language and emigration, and all points between. “I do not know what it is like,” she offers, to open the poem “Elegy from a Wave,” “to lose a beloved to the sea. // Their body found / by watchful eyes // of a fisherman’s tugboat. / The raft it tows // so close to one’s leaving.”

June 9, 2022

reading in the margins: Kristjana Gunnars

I’m appreciating the reminder of how important Kristjana Gunnars’ novels were to shaping my early thinking on writing, thanks to

The Scent of Light

(2022), a reissue of her five novels—The Prowler (1989), Zero Hour (1991), The Substance of Forgetting (1992), The Rose Garden: Reading Marcel Proust(1996) and Night Train to Nykøbing (1998)—in a single volume, offered with a stunning introduction by American poet and critic Kazim Ali. “Perhaps it is not a good book, he said, James Joyce said,” Gunnars wrote, to open The Prowler, “but it is the only book I am able to write.” I most likely picked up second-hand copies of those first three novels somewhere in my early twenties, possibly from the now-defunct Richard Fitzpatrick Books, a store that sat somewhere along Ottawa’s Dalhousie Street. Returning to these novels, I’m startled by how deeply some of these sentences resonated, and became foundational for my thinking of, and approach to, composing fiction. The very notion that we write the books we do and in the ways that we do, in large part, because we simply haven’t the ability to write them in any other way. How did you do that, someone might ask. Practice, intuition, judgement. The question becomes unanswerable, beyond what might otherwise sound flippant. Experience.

I’m appreciating the reminder of how important Kristjana Gunnars’ novels were to shaping my early thinking on writing, thanks to

The Scent of Light

(2022), a reissue of her five novels—The Prowler (1989), Zero Hour (1991), The Substance of Forgetting (1992), The Rose Garden: Reading Marcel Proust(1996) and Night Train to Nykøbing (1998)—in a single volume, offered with a stunning introduction by American poet and critic Kazim Ali. “Perhaps it is not a good book, he said, James Joyce said,” Gunnars wrote, to open The Prowler, “but it is the only book I am able to write.” I most likely picked up second-hand copies of those first three novels somewhere in my early twenties, possibly from the now-defunct Richard Fitzpatrick Books, a store that sat somewhere along Ottawa’s Dalhousie Street. Returning to these novels, I’m startled by how deeply some of these sentences resonated, and became foundational for my thinking of, and approach to, composing fiction. The very notion that we write the books we do and in the ways that we do, in large part, because we simply haven’t the ability to write them in any other way. How did you do that, someone might ask. Practice, intuition, judgement. The question becomes unanswerable, beyond what might otherwise sound flippant. Experience. I recently read a passage in Montreal poet Gillian Sze’s quiet night think: poems & essays (2022) that caught my attention: “Why do you write? was a question that I was often asked, and my answer for both weeding and writing was Rilkean: I must. Yes, there was something inherently futile with every weed I pilled, but I did so stubbornly, thinking of what Mordecai Richler said: Each novel is a failure or there would be no compulsion to begin again.” I was struck by Richler’s quote (I would be curious of the context around the original source), one that suggests a difficulty around such an adherence to scale: the massive narrative undertakings of his novels, writing hundreds of pages encompassing such a wide swath of detailed, world-building, narrative prose. The scope of works might be comparable to other Canadian writers of his era such as Margaret Lawrence or Robertson Davies. Eachnovel, Richler said. Well, each novel of his, maybe. As with the example of Gunnars, my own sense of writing is not to encompass the whole world, or even the whole world of a space, but a particular portrait of a scene or a sequence. I don’t agree, I suppose, but it also doesn’t apply. But the difference in approach is interesting.

I spent a great deal of my twenties telling myself that I preferred the French-language aesthetic of writing interior monologues over the English-language aesthetic of the exterior description—pages upon paragraphs to describe every inch of a tree, for example, or what colour a particular character’s hair might be—none of which I considered required unless it is actually essential for the story itself. It took years to realize that my prose didn’t require dialogue, something I didn’t know how to include either way. I wonder now if it was actually through Gunnars that I became interested in novels propelled by language over cinematic scenes, and assembled via a narrative constructed through accumulation. Whatever else a book-length project might be, at least in my thinking, it is less all-encompassing than a kind of lyric, narrative burst, which relate to my early readings of writers such as Kristjana Gunnars, Elizabeth Smart and Dany Laferrière, all of whom also explored the form of the novel as accumulations, and of auto(biographical) fictions. “For eight hours we concentrated,” Gunnars writes, as part of The Substance of Forgetting, “not noticing time passing. Dawn turned to morning. The sun rose and shone on the water. Once we stepped out and watched the blank stillness of the water. The thick forests of the mountainsides mirrored themselves in the lake.”

“I have sometimes thought: it is possible there is no such thing as chronological time. That the past resembles a deck of cards. Certain scenes are given. They are not scenes the rememberer chooses, but simply a deck that is given. The cards are shuffled whenever a game is played.” I held on to this passage of The Prowler for more than a decade. Thinking back on it now, the notion of memory as a deck of cards shifted the foundations of how I saw the construction of narrative prose. A deck of cards, or a photo album: each section imparts the possibilities of the next. The novel I fumbled to compose across the mid-1990s, titled “Place, a novel,” was a collaged-suite of self-contained bursts that attempted to hold itself together across a very loose narrative, akin to how my twentysomething self understood Gunnars’ novels. It didn’t cohere, but it was certainly the narrative structure I furthered across my two published novels—white(2007) and Missing Persons (2009)—as well as my current work-in-progress. As Ali writes as in his introduction to the new edition:

The struggle of the writer to transform or transmute life into literature in a meaningful way may be why in each book there is a fluidity of time (the story as it happens, but also the narrator writing the story) as well as place (Denmark/Iceland, Winnipeg/Portland, BC, Interior and Coast, Trier/Hamburg, and Denmark/Saskatoon/Calgary). The shifts in time and space are required by the core structure of each book: a writer is writing a book. She writes the book and she tells you about what it was like to write the book.

There is such a lovely and lyric interiority to her passages. Gunnars’ novels exist as much through ideas, theory and speculation, writing internal monologues over descriptive scenes, and writing out the ways in which one writes, far beyond simply offering a story told through sentences. As the opening paragraph of The Prowler reads, in full:

Perhaps it is not a good book, he said, James Joyce said, but it is the only book I am able to write. It is not a book I would ever read from. I would never again stand in front of people, reading my own words, pretending I have something to say, humiliated. It is not writing. Not poetry, not prose. I am not a writer. Yet it is, in my throat, stomach, arms. This book that I am not able to write. There are words that insist on silence. Words that betray me. He does not want me to write this book. The words make me sleep. They keep me awake.

So much of my articulations on Gunnars’ work appear in the past tense, although that shouldn’t suggest I’d been absent from thinking about her writing across those intervening years. More recently, I was fortunate enough to produce a chapbook of her poems in 2016, snake charmers : a cycle of twenty poems, for an event we were both participating in through the University of Alberta’s department of English and Film Studies, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of their writers-in-residence program. A bit later, I produced a chapbook-length essay of hers as well, a moment in flight: essay on melancholy (2020). “There are fragments of eternity in all passing things.” she writes, as part of that essay, suggesting a clear linkage between those early novels and her current work, although the essay was restructured into a long poem, set as the opening sequence of Ruins of the Heart: Six Longpoems (2022). I’m not sure why the difference in structure, but it does alter the flow, just a bit. I am still looking into it.

June 8, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Patrick Connors

Patrick Connors

[photo credit: Linda Kooluris Dobbs] first chapbook, Scarborough Songs, was released by Lyricalmyrical Press in 2013, and charted on the Toronto Poetry Map.

Patrick Connors

[photo credit: Linda Kooluris Dobbs] first chapbook, Scarborough Songs, was released by Lyricalmyrical Press in 2013, and charted on the Toronto Poetry Map. Other publication credits include: Spadina Literary Review; Tamaracks; and Tending the Fire, released last spring by the League of Canadian Poets.

His first full collection, The Other Life, is newly released by Mosaic Press.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Scarborough Songs legitimized my decades-long dream of being a writer. I am extremely grateful to Luciano Iacobelli of Lyricalmyrical Pressfor giving me that opportunity, especially since nobody else would have touched me with a ten-foot pole at that point. The Other Life is when I became an author. When Howard Aster and Mosaic Press accepted my work, it was a rite of passage. It took me several years and many attempts to get it right. I hope my next full collection doesn’t take as long, but if so, it will be worth it. It’s about being more professional, more complete, in something I have always been passionate about.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wrote short stories from a very young age. For the most part, I thought poetry was not cool enough for me to pursue or appreciate, unless it originated from Neil Peart, Muhammad Ali, or King David. However, a poetic sensibility always came through in my stories, my sense of humour, and my viewpoint on life. Poetry became the embodiment of my personal struggle when I was a tweenager, as seen in my piece, “My Father the Poet” (page 40 of The Other Life), and then when I went through profound personal crises in my thirties.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My most recent poem, “Violet”, took me about 20 hours to write. I sometimes get lucky and blessed enough to have this happen, this sort of “struck by lightning” experience. Most of the time, it takes me about 3 weeks to write a poem, or 4 to write two related pieces, or 6 to write a suite. In those 3 or more weeks, there will be sleepless nights, endless revisions, and the feeling that the work is crap and I should give up on it. That’s how I usually realize it’s worthwhile and that I should pursue it. The real challenge is to make those pieces seem as relatively simple as “Violet” was to bring to completion.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I am definitely an author of short pieces with the idea of having them eventually contribute to a larger whole. I have focussed on writing more multi-page poems as I work on my next collection. The poem “Killdeer”, written by Phil Hall, inspired me to not cheat anyone who might want to read my work by feeling the need to cut myself short. I am hoping this spring to write a poem two-thirds as long and half as good as “Killdeer”. If successful, I will be pretty close to having another manuscript to submit.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love public readings (We met at Pivot). I miss them more than pretty much anything since the pandemic, except perhaps volunteer work. I love the community of like-minded people with a common interest. I love the exchange of ideas. I love the opportunity to share a little piece of myself with an audience. I have curated and hosted many events over the years, I relish being invited to feature at different series, and I get a real kick out of doing open mics from time to time, as well.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I hope to answer the question of how we belong, how we fit in together while being unique. We have become compartmentalized and generalized and also very alone. I think we have these problems more than ever, not just because of Covid, but because of the widening gap between rich and poor, the proliferation of technology, the decreased value of labour. More than ever, there is an emphasis on “us” vs. “them” without really knowing who “us” are, and that we are all one.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's dangerous, and also limiting, to say artists SHOULD play a role in progressive movements, just as it is dangerous to say artists should NOT play a role in such movements. However, art gives a tremendous opportunity to give a counter-cultural voice, a check and balance on the establishment, and a means to aspire to something better. Poetry which is well constructed, with clarity and depth of thought, but also speaks to everyday people without talking down to them, is the quest for ultimate good, a noble attempt for the human race as a whole to evolve.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I became a better writer and a better man while working with Mick Burrs, God rest his dear soul. Terry Barker kicked my ass and forced me to make The Other Lifebetter. So, both, definitely!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

A poem I wrote last year, “Finding Myself”, begins with the following epigram by Lawrence Ferlinghetti: ‘Strive to change the world in such a way that there's no further need to be a dissident.’

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?