Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 125

May 27, 2022

Nanci Lee, Hsin

Hsin is less a set of moral standards than an appeal to tune. Heart-mind and nothingnessare fair English translations, but their tidiness risks losing some of the sharper, wider sides of absence and appetite. As a historical process, according to Thaddeus T’ui-Chieh Hang, Hsin frustrates “the psychological fragmentation and compartmentalization of the West.”

I focused on Hsinfor this book because it is the word at the centre of Su Hui’s ancient, intricate, and lost palindrome of longing.

It took a few days to begin to write out my notes on the full-length poetry debut by Nova Scotian poet Nanci Lee, her Hsin (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2022), given the prompts it generated in my own thinking around adoption and identity, especially based on information garnered over the past two years through multiple genetic connectors (but enough about that). The poems of Hsin fragment, collect and pool across a wide stretch of narrative and meditative lyric, composed as a way to situate, navigating adoption, and seeking to connect properly to her disjointed cultural threads and elements of family. “It’s been decades.” she writes. “I can imagine that you, / too, must have had a full life.” Structured in three sections—“Who are you?,” “What do you obey?” and “How will you prepare for your death?” she writes from a very specific prompt, seeking resolution, clarification and the ways through which the proper questions might emerge. She seeks clarification on questions that have been building across the length and breadth of her life, some of which might never find the answers she seeks, in the forms she might seek them. In the first section, she offers:

Found, Children’s Aid Society Records

You were born too

soon. Long and lean,

sallow skin. She left

Hong Kong to study.

He left just after

your birth. Syrian,

medium build. You were

fussy, didn’t like to be bathed,

undressed. She showed

little interest in you.

Said they were friends.

She was raped.

You loved to talk.

When you were made

ward of the crown,

she stayed poised.

In certain ways, this is a collection of poems composed around and on the very idea of silence (reminiscent, through that singular element, of Nicole Markotić’s debut novel). “My birth / mother found me decades later,” Lee offers, “only to lose her own mom. This was / a sign, she was sure of it. The gods made her a trade for silence.” Composed through great care and a deep attention, Hsinemerges as a work of grief and loss, discovery and searching, held as the notes produced across the journey as it unfolds, unfolding. “predictable /// if you know // from where / in the sequence ///// does a mother / want [.]” she offers, elsewhere in the first section. There are elements of this collection that echo some other titles that Brick has been producing lately, especially since the shift in editorial and ownership; an echo of other of their book-length poetry debuts that explore familial loss, identity and placement through the gathering of meditative and narrative lyric fragment, whether Andrea Actis’ Grey All Over (2021) [see my review of such here], or David Bradford’s Griffin Prize-shortlisted Dream of No One but Myself (2021) [see my review of such here]. “Nothing from nothing means nothing,” Lee writes, early on in the collection, “she hummed from the back- / seat of the Pontiac, swallowed in afternoon sun.” To open the collection, she offers a brief note for the sake of context to her title. The short note ends: “Body is history and Hsin holds silence in ways that both claim and keep it at bay.”

In certain ways, this is a collection of poems composed around and on the very idea of silence (reminiscent, through that singular element, of Nicole Markotić’s debut novel). “My birth / mother found me decades later,” Lee offers, “only to lose her own mom. This was / a sign, she was sure of it. The gods made her a trade for silence.” Composed through great care and a deep attention, Hsinemerges as a work of grief and loss, discovery and searching, held as the notes produced across the journey as it unfolds, unfolding. “predictable /// if you know // from where / in the sequence ///// does a mother / want [.]” she offers, elsewhere in the first section. There are elements of this collection that echo some other titles that Brick has been producing lately, especially since the shift in editorial and ownership; an echo of other of their book-length poetry debuts that explore familial loss, identity and placement through the gathering of meditative and narrative lyric fragment, whether Andrea Actis’ Grey All Over (2021) [see my review of such here], or David Bradford’s Griffin Prize-shortlisted Dream of No One but Myself (2021) [see my review of such here]. “Nothing from nothing means nothing,” Lee writes, early on in the collection, “she hummed from the back- / seat of the Pontiac, swallowed in afternoon sun.” To open the collection, she offers a brief note for the sake of context to her title. The short note ends: “Body is history and Hsin holds silence in ways that both claim and keep it at bay.” He slept in church and cycled to fires. The gods didn’t mind because he fed the animals, cleaned their cages.

Silent, bent over steaming wok.

He stuffed the gaps with garage-sale finds. Didn’t fly or borrow, marry Chinese or make a single apology I can remember. As the attic filled, we threw out the junk.

But now I recognize a man who can make himself comfortable.

Eccentric, or as they say of those with no money, odd. Simply hung up the phone when he had nothing left to say.

When I came from meeting my birth mom, he asked, So, was she good lookin’?

May 26, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brianna Ferguson

Brianna Ferguson

is a writer from the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. A current MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia, she also holds a BA in Creative Writing and a B Ed in Secondary Education from UBC. Her poems and stories have appeared in various publications across North America and the U.K.

A Nihilist Walks into a Bar

is her first book.

Brianna Ferguson

is a writer from the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. A current MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia, she also holds a BA in Creative Writing and a B Ed in Secondary Education from UBC. Her poems and stories have appeared in various publications across North America and the U.K.

A Nihilist Walks into a Bar

is her first book. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I promised myself at the beginning of this year that I’d make an actual effort to get my book published. I sent it out to a couple Canadian presses in January, and by the end of February, I had an email from Mansfield Press saying they would like to publish it. I was very lucky in the quick response--I know it usually takes much longer than that. So far, the book’s only been out for a week or two, so it hasn’t really had much time to take the world by storm yet. Just knowing my poetry was good enough to end up in a book, though, has been life-changing. I was fortunate enough to work with Stuart Ross as my editor, and he really dove in. He didn’t hold anything back, which was exactly what I’ve always wanted. With pretty much every prior publication I’ve had, there was maybe a single back and forth about content or grammar and that was it. With Stuart, though, by the time the book was finished, we’d discussed every single comma and word choice.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I can definitely go into the way, way back origins when I was a wee child and I used to make up rhymes and poems and keep them in a little collection, but that’s probably less interesting than my honest-to-goodness adult self just falling in love with poetry. I love words and I love things that don’t require the longest attention span and poetry is all about brevity and specific word choices. I always wanted to be the type of writer who makes up characters and falls half in love with them and their plights, but that’s never been me. I’m far more obsessed with the minutiae of daily life and the beauty and horror that can come from commonplace things. There’s so much drama and excitement and poignancy in just the regular, daily things that go on, and I love to capture it as best I can. I also really do not have the attention span for anything longer anymore. Maybe once, but not now. I like short, punchy pieces. Just tell me what you want to tell me so we can all move on.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

First drafts of poems usually come to me in a burst. Some little exchange or moment will happen when I’m out and about, and the first lines will happen suddenly. I’ll get those down, then the rest will trickle in after. As I’m getting things down, my mind will start making connections to whatever overarching philosophical thing I think the poem might relate to, or capture. I’ll tweak things just a bit to paint a fuller picture and pull everything together, and voila.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Nihilist was the first time I ever really started to aim for a theme. I mean, a lot of the poems are from years ago, before I realized I was focusing on specific ideas, but I definitely started to hone the collection a few months before I submitted it anywhere. It’s hard for me not to write on the themes I’m interested in, though. Like Bukowski, always drinking and gambling and dating random women and then writing about those things, I can’t help writing about belief systems and beer and the embarrassing things we don’t like to talk about that nevertheless take up so much time in our days. Eventually, after writing about them long enough, I’ve got a book.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I used to love them during my BA, but my BEd was much more comprised of people who wanted to teach (go figure) than of straight-up writers, so I wasn’t part of the scene really when I was doing my teaching degree in Vancouver. And then my entire MFA has been online, due to covid, so honestly I haven’t really been behind the mic in five years or so. I do find enormous value in reading my stuff out loud to someone I want to impress, though, like my husband, who’s not really a natural poetry lover. If I can impress him, or keep him listening through the whole thing, it’s a good sign I’m doing something right. If I don’t read my stuff to him, I run the risk of getting a little too obscure and stuck in my own head. And then I’ve got a friend I always bounce things off of, and my sister, who loves reading my first drafts, too. Naturally, most of her responses are more gushing than constructive, but it helps just as much.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t want to accidentally hurt anyone’s feelings, and I don’t want to accidentally say something super incendiary or stupid without realizing it. Sometimes, when you’re taking risks or just being super honest, it’s easy to say something horrible without realizing it. I desperately want to add something useful to the conversation of “who are we” “what is this all for” “is there a point to life” because I feel like awe and wonder are too often shoved aside for easy answers. Or, if not easy, then at least answers. And I don’t think there really are answers for some things--not that we can comprehend in any sort of meaningful way. Like my poem about my dog being afraid of the vacuum cleaner, and me trying to tell her--in English--that it’s okay and necessary, and her never understanding, and us going through this weekly rigamarole of necessity and fear and drama, I think life is just this swirl of attempts and missed connections and chaos that can’t really be cut through with the tools we have. If you’ve got seven names for colours, and an eighth colour comes along, and you just can’t really describe it, I mean, that sucks but I guess that’s that. I love that language can try--I applaud it for that--but I also want people to be able to embrace the unknowable without always trying to cram it into the things we do know, or think we know. Sometimes unknowable means “beyond any stupid theory you can cobble together” and that’s fine.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I had a prof in my BA, Sonnet L’Abbe, who talked quite a bit about the importance of writers in the scientific community, and how necessary it is that people who understand communication and nuance be the ones to communicate things. You see it sometimes in science where something happens or something’s discovered and there’s a press release around it that makes no sense or sounds entirely different from what actually happened, and everyone’s confused and drawing their own conclusions and it’s like okay, maybe this could have been prevented from happening if a writer or two had simply been part of the conversation from the get-go. I mean, look at politics and the ways that narratives and catch phrases totally decide elections. That’s the collective fates of entire countries and millions of lives that are decided entirely by the words used to describe things. Even things as simple as “global warming” vs “climate change” and how necessary it was to explain to people that cold days can still happen--that doesn’t mean the Earth isn’t heating up. Look how many years we wasted on that one, because of a couple carelessly chosen words.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? Having Stuart go through all my poems and give me his honest suggestions--always with the understanding that I could take or leave his ideas--really opened up my mind about my own work. Seeing what someone else saw when they looked at my work--the things they were confused about, the endings they felt were too tidy or obvious--really helped clarify my thinking. There’s a terrible movie that I absolutely love called Total Eclipse, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and David Thewlis, and it’s about Rimbaud and Verlaine. There’s this exchange where Thewlis (Verlaine) asks DiCaprio (Rimbaud) if he thinks poets can learn from each other, and DiCaprio says “only if they’re bad poets.” Obviously, I think that’s stupid, but on a lonely, insecure day, sometimes I’m like “that’s absolutely correct. If I were a genius, I’d have all the best words from the get-go.” Naturally, that’s stupid--I learned tons from working with Stuart, and it doesn’t matter at all that I learned them from another writer--but every once in a while it’s fun to pretend there’s such a thing as a totally self-made anything.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

One of the best conversations I ever had was with my husband, Marshall, after a really dull work day. I felt like I was wasting my life, and the added pressure of trying to “make something of myself” or do something “great” just underlined how little my daily grind meant to me. Marshall kind of threw my nihilistic approach back at me and said that if nothing means anything in any sort of narrative arc, then it’s literally impossible to waste your day, or waste your life. In a narrative sense, anyway. You can’t be in the wrong place or doing the wrong things, because there’s no right place or right things. That just released me from the whole added pressure of trying every day to make my personal story a good one. After that, I just did what I felt. I mean, as much as a poor person can. If I felt like writing, I did that. If I felt like writing a poem about beer or bodily functions, I did that. I didn’t judge it for not being the next Grapes of Wrath. I just did it. And now I have a book. It’s like Bukowski’s whole “Don’t Try.” Just do what comes naturally. For me, that’s sporadic poems about beer and butts.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

For most of my writing life, I saw The Novel as the holy grail of writing. It was just The Thing you do if you’re a real writer. It’s what sells. It’s what gets turned into movies. It’s what struggling writers agonize over until they have their big break. I didn’t know where else to aim. I brought up the whole “holy grail” thing with some poet friends at a party once, though, and they were like no, absolutely not. That’s stupid. You can do whatever you want. If you gravitate to poetry, be a poet. If you naturally write scripts or songs, do that. There’s no ultimate best form. That really freed me up. I still wasn’t sure what I preferred to write, though, and I wrote a ton of short stories and four or five first drafts of different novels, but where I usually enjoy my poems once they’re done, the novels were--to me--so bad, I wondered if I was actually literate. It just didn’t really work for me. Short stories still work from time to time, because their brevity gives me the chance to just say the thing I want to say as fast as I can, and they give me a little more space to explore things than poems can at times, but poetry just comes far more naturally to me. Any time I have to work on something longer, my gut reaction is to write poetry instead. I never get as much poetry done as I do when I have an essay due. It’s just where I go to cool off.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m a morning writer, for sure, but only once I’ve got something in the world. If I’m not teaching on a given day, and I’ve got something started, I get up, make coffee, and plop myself down on the couch with my laptop. If I’ve got nothing started, I go for walks, drive around, do some people-watching at the mall, and watch movies with dialogue that gets the juices flowing. Most of my ideas come from eavesdropping some inane conversation or seeing somebody do some boneheaded thing in traffic. Often, that somebody is myself. An idea will hit and I’ll chuck it in the Notes app on my phone as fast as I can. The first draft usually explodes out of me, and then the morning writing happens for edits.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I’ve read Douglas Walbourne-Gough’s collection, Crow Gulch,a ton of times now. He’s so careful with his language, it always reminds me to revel in words themselves. When in doubt, focus on sensory details and the rest will come. I also delve into any random poems I can find by Catherine Cohen. Her first book of poems, God I Feel Modern Tonight came out this year from Knopf, and it’s hilarious. She just writes about anything and everything, and she’s just so funny. Laughing really gets my creative juices flowing. Reading a funny thing about some stupid random event gets my mind running full speed about all the inanities I saw earlier in the week that I didn’t pay much attention to.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilac trees--my mom had some bushes in front of our house, and there are a million wild ones in this grove near my childhood home. Also cleaning supplies. My mom’s a housekeeper and super clean, and our house always smelled freshly cleaned.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Movies influence me literally 100% of the time. I’ve seen so many movies so many times over. I love the cadence of dialogue delivered by a good actor. I love pacing and cinematic moments. I love and and and . Careful writers and directors and careful deliverers of dialogue. A good, musical line will stick with me forever. I’m terrible at hearing lyrics when I listen to music, but for some reason The Avett Brothershave a million songs where I hear and love every word. They’re proper poets who really understand rhythm and imagery, in addition to being fabulous instrumentalists and singers.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve read a million poems by Bukowski and all of his novels, and while I’ve largely moved on from him now, he did so much for me as a writer. His writing is so accessible and relatable. Obviously, Catherine Cohen has been the dominant poetic voice in my head the last year or two, and then the five or so movies I watch on repeat, which I won’t name because most of them are embarrassing.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’ve been working on a memoir for years--literally over ten years, and several different iterations, most of which have been fictionalized accounts of things--and I need to finish it before I die. It’s become my MFA thesis, and it’s this big unwieldy thing about my teen years. It’s not terribly poetic--all the iterations before this latest non-fiction draft have been novelized versions of things--but it is the story I have to tell in order to be able to move on with my life.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

As obsessed with movies as I am, I would have loved to be an actress. I’m so not an actor--I hate acting exercises, nothing about acting comes naturally to me--but there are so many movies I couldn’t live without. I’d have loved to be born a natural actor, but it just didn’t happen that way. That, or a banjo player in a bluegrass band. It’s so unfair we can’t choose what gifts we’re born with (if any) but that’s life.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

That’s a harder one to answer. I’ve always written, as so many writers will tell you. It just came naturally. I don’t know of a better way to communicate than to communicate. Anything can be misinterpreted, but I feel like the written word has the best chance of saying what it wants to say. I also have no talent for anything else besides probably knitting. If I’m ever lost or low, I just start writing. It’s cliche to say, but writing’s probably saved my life several times over.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently finished Kiese Laymon’s memoir Heavy, which I thought was pretty fantastic. It was fascinating to read about a life so different from my own, yet so relatable in so many ways. Moviewise, it’s tricky to say, because I watch the same movies so many times over. I’ve been absolutely hooked on Phantom Threadfor a year or so now, though. Like so many other good little English majors, I adore Daniel Day-Lewis.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m always working on new poems about the neighbours, my mortality, my dog, etc, but in terms of more directed projects, I’m working on my MFA thesis, which is a memoir about learning I was intersex and bisexual and all that fabulous stuff in the early 2000s. I’ve written so many versions of this story before--a thriller, a literary novel, several essays, a novella---but I’m hoping I’ve finally landed on the right medium. You’d think a memoir would be the natural first choice for a true story about oneself, but I was so devoted to the idea of being a novelist, I couldn’t let myself abandon the idea of turning it into a novel. As it turns out, though, the only way to really get it off my chest and move on was to write it as it happened, and to explore the various ways it’s affected me throughout the subsequent years. It might still turn out awful, but at least I’ll be able to move on. I’m also working on a poem about how Fall is basically one big hangover after the Saturday night that is Summer. It’s a dazzling, towering metaphor, and no doubt destined for the New Yorker.

May 25, 2022

Court Green : three poems and an interview (conducted by Lisa Fishman,

In case you didn't catch, I was interviewed back in 2020 by Lisa Fishman, and the interview was posted recently over at Court Green, along with three recent poems! Huzzah! I actually returned a variation on Fishman's questions to her, not long after our interview was conducted, posted over at periodicities last year (but you already knew that, right?).

In case you didn't catch, I was interviewed back in 2020 by Lisa Fishman, and the interview was posted recently over at Court Green, along with three recent poems! Huzzah! I actually returned a variation on Fishman's questions to her, not long after our interview was conducted, posted over at periodicities last year (but you already knew that, right?). May 24, 2022

Julie Carr and Lisa Olstein, Climate

Some of it I’ve touched on already, some of it we’ve been circling since our first exchange, some of it this particular twelve days I’ve been feeling all over, messy and vivid and focused and vague: precarity, jeopardy, fear of loss. You felt some breeze of it, I think, that made you worry your letters were somehow insufficient or ill’ received which wasn’t the case in any way. I’ve felt a version of this worry, from time to time, too: what if in a letter or in a real-life scenario I’m stupid or insensitive or one of us realizes, meh, not so much, less than I thought.

I see from my earlier note to myself that I wondered also how much wish infuses this connection, this relationship sprung up between us, its listening and avenues for thinking through. But I don’t feel worried or even really wonder about that today, right now, as I actually write to you. Right now, I feel that this, our collaboration, which is a certain kind of companionship, is exactly as you wrote: an exactment of searching together with, to, through our microclimates, these presents, these I’s and you’s. (Lisa Olstein, July 19, 2018)

I’m very much enjoying the epistolary essays that make up Julie Carr and Lisa Olstein’s collaborative call-and-response, the non-fiction

Climate

(Essay Press, 2022). Writing to each other in a sequence of letters, Carr and Olstein write out their anxieties, fears and stories around #Metoo, climate change, parenting, school shootings, sexual abuse, Trump’s election crimes, a friend’s suicide, the Paris Climate Accord, and other events, documenting their experiences and fears as two women, two poets, writing directly to each other in an intimate space. “I have no stomach for violence.” Olstein writes, as part of “July 19, 2018.” “I stick on it—snag, catch, fray, fall apart. I think it’s normal, to a point. It’s something, it seems, that varies quite a bit person to person. Kindly, in an email, E. called it a form of empathy, my inability to stop imagining into the violence of Ian’s death, a way of trying to understand—both to literally register and to fathom.” Opening with Carr’s January 7, 2018 “Dear Lisa,” and ending on April 17, 2019, they write the space of sixteen months across American culture through a prose that at turns is breathtakingly beautiful, anxious, grief-stricken, supportive and deeply intimate, weaving in thoughts around literature, politics, culture and their daily lives. As Olstein writes as part of her entry for October 25, 2018, referencing the televised hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee to confirm Brett Kavanaugh:

I’m very much enjoying the epistolary essays that make up Julie Carr and Lisa Olstein’s collaborative call-and-response, the non-fiction

Climate

(Essay Press, 2022). Writing to each other in a sequence of letters, Carr and Olstein write out their anxieties, fears and stories around #Metoo, climate change, parenting, school shootings, sexual abuse, Trump’s election crimes, a friend’s suicide, the Paris Climate Accord, and other events, documenting their experiences and fears as two women, two poets, writing directly to each other in an intimate space. “I have no stomach for violence.” Olstein writes, as part of “July 19, 2018.” “I stick on it—snag, catch, fray, fall apart. I think it’s normal, to a point. It’s something, it seems, that varies quite a bit person to person. Kindly, in an email, E. called it a form of empathy, my inability to stop imagining into the violence of Ian’s death, a way of trying to understand—both to literally register and to fathom.” Opening with Carr’s January 7, 2018 “Dear Lisa,” and ending on April 17, 2019, they write the space of sixteen months across American culture through a prose that at turns is breathtakingly beautiful, anxious, grief-stricken, supportive and deeply intimate, weaving in thoughts around literature, politics, culture and their daily lives. As Olstein writes as part of her entry for October 25, 2018, referencing the televised hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee to confirm Brett Kavanaugh: The wound of that testimony. The wound that is Facebook right now, that is my email queue, that is the steady stream of often nuanced and searing think pieces by women. The wound of hearing the cordoned-off voices of the pro-Kavanaugh women they keep digging up to interview. In my “bubble” it’s women split open, all wound. That Rukeyser quote has been going around again—what would happen if one woman told the truth about her life / the world would split open—but the problem is it doesn’t, the world doesn’t split, the woman does.

There is something of the call-and-response, two different voices responding and reacting, that is reminiscent of San Diego poets Sandra Doller and Ben Doller’s collaborative prose-work The Yesterday Project (Sidebrow Books, 2016), both writing in collaboration (albeit blindly) in the shadow of a life-threatening diagnosis [see my review of the book here]. Writing the multitude that “climate” suggests, the Carr and Olstein work through the events and news cycles that permeate their daily lives, writing a climate that would allow for someone such as Brett Kavanaugh to succeed, a climate of gun culture and repeated incidents of mass shootings, and the environmental damage that continues to be perpetrated upon the landscape, and every species set upon the earth. The book is also broken into sections that suggest thematic breaks, offering each section the same list upon each title page, but with different elements highlit, from “Bomb cyclone (Boston, MA),” “#Metoo (accrual)” and “Mass shooting (Santa Fe High School, Houston TX)” to “Package bombs (Austin, TX),” “Trial for sexual abuse, Larry Nassar” and “Women’s March (2nd annual).” This is a politics lived on the ground, as both are aware of how deeply affected either of them could be through any of this, whether the close proximity to a particular shooting, or witnessing the Special Senate hearings with Christine Blasey Ford through the lens of their own experiences. These events don’t live beyond their experiences or their immediate worlds, but are deeply connected across culture, in a way perhaps more deeply felt, and far better understood, by Carr and Olstein than by generations prior. As Carr writes as part of “November 2, 2018”: “If this were a letter in the mail and not over email, I’d send you a piece of tree bark. My poets all write sad songs, but they also keep believing in poetry’s ‘viewless wings.’ I never really understood why ‘viewless.’ Because poetry doesn’t see the suffering that it speaks of? Because you can’t see poetry’s power, though it’s there?” This is a book that documents grief and trauma across American culture in the immediate moments, existing within a conversation between two friends who are both poets, thinkers, critics and mothers, and articulating a deep connection between living and thinking with poetry and political culture. As much as anything, this book examines how deeply connected these seemingly-disconnected threads of politics, literature and daily life truly are and can be, in a lived sense; their lives propelled by the pure vulnerability of their open, thinking hearts. And that, by itself, is stunning.

You were writing about collectivity: how the work at NASA is no one person’s work, and that even failure adds to the whole. The other day, I was reading something a friend wrote about breath: how we breathe in common. He rejects the notion of the self, the notion of the human, is seeking something more radically in-common to define us. Breath. Earth. Soil. Every version of self is painful to us, he says.

My fingers stopped there, because I don’t know if he’s right.

But still, I would say that the collaborative nature of the Lab reflects something we do want, always, which is to fade away into the project and feel, if nothing else, our sentences as they move in a landscape.

Love,

Julie.

May 23, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joshua Nguyen

Joshua Nguyen

is the author of

Come Clean

(University of Wisconsin Press), winner of the 2021 Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry and the chapbook,

American Lục Bát for My Mother

(Bull City Press, 2021). He is a Vietnamese-American writer, a collegiate national poetry slam champion (CUPSI), and a native Houstonian. He has received fellowships from Kundiman, Tin House, Sundress Academy For The Arts, and the Vermont Studio Center. He has been published in The Offing, Wildness, The Texas Review, Auburn Avenue, and elsewhere. He has also been featured on both the VS podcast and The Slowdown. He is a bubble tea connoisseur and loves a good pun. He is a PhD student at The University of Mississippi, where he also received his MFA.

Joshua Nguyen

is the author of

Come Clean

(University of Wisconsin Press), winner of the 2021 Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry and the chapbook,

American Lục Bát for My Mother

(Bull City Press, 2021). He is a Vietnamese-American writer, a collegiate national poetry slam champion (CUPSI), and a native Houstonian. He has received fellowships from Kundiman, Tin House, Sundress Academy For The Arts, and the Vermont Studio Center. He has been published in The Offing, Wildness, The Texas Review, Auburn Avenue, and elsewhere. He has also been featured on both the VS podcast and The Slowdown. He is a bubble tea connoisseur and loves a good pun. He is a PhD student at The University of Mississippi, where he also received his MFA. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

There are more things to think about and to juggle. A lot more emails. A lot more things to schedule. It’s a lot of extra work when your first book comes out when you don’t have a booking agent or literary agent. I had to create my own promotional materials, I had to schedule all my readings, I had to make sure bookstores hold my books, and I also had to edit proofs.

Because I am still in school, in a creative writing PhD program, the book stuff feels like a reprieve from the stress of school. I am glad that my book tour is all during the winter break— I was able to focus on my schoolwork during the fall semester, and then during the winter break, I can stay present with my book and the people I am reading with.

It does bring me a lot of happiness when I see people holding my book. For a while, it didn’t feel real. Now, it feels as real as ever with the physical object of the book in the world. I’m not nervous about what people will say about it, I am more nervous about what they don’t say. I want to know the poems that people like and don't like! That’s probably because I cringe at positive reinforcement— ask all my friends, they know it’s hard for me to take a compliment.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually fell in love with short stories first. It was Flannery O’ Connor and Poe. But I came to love poetry when I tried out for the Houston Youth Poetry Team called Meta-Four Houston. Writing workshops and practices were held at the Houston Downtown Library and I had to compete to get on the team— they were taking the top 6 of the competition. I actually got 8th place first, but then someone actually got a time penalty, and another person couldn’t do the time commitment, so I got the final 6th spot! This was when I was 14 years old— and I have been writing poetry ever since.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Because of being in consistent writing workshops, three - four days a week, during my high school summer years— I can churn out a poem (though it’s a bad draft) in 5 minutes or less. The editing process takes me a while. Editing and revising can take me like 2 weeks.

Typically, I come up with loads of ideas for poems for a particular project, and put them in one note on my phone. I spend half of the year coming up with ideas and projects. Then I’ll usually spend two months (the summer or winter break) writing first drafts of these poems. Then I spend any free time I have editing the project up until it gets picked up somewhere.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like starting with the project first because it funnels my pen. I work best with constraint— which is why I tend to turn to form. The idea of the project works as a form so that I can stay focused and not go everywhere.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love readings! Open mics are instant editing workshops. If you read your poem allowed, you’ll hear things you don’t like. You can also gauge the audience and see which parts of the poem they respond to.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m invested in caesura. In my book, Come Clean, I use the enclosed bracket throughout the book as a caesura, as acrots (acot?), and as place-markers. I’m fascinated by it because it can be seen as something as an aside, but what if the aside is what’s trying to be unhidden? I also think you can show breath with your caesuras and enjambments, but what happens if you enclose the breath?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer, if they choose so, can be a voice in trying to express the inexpressible. At best, they can unlock something in a reader— that something can be emotional, mental, or physical.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s essential— as long as you find an editor that you mesh with.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My dad always taught me to be content yet always be ambitious. He taught me to be grateful for where I am at and what I have in the present, but to not be afraid to want more.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (text to more performance-driven work)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think I went the opposite route. I went from performance-driven work to text. But either way, I think it shouldn’t matter. A good poem should be good while read on the page. And that same poem should be good if read on a stage.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t have a particular routine. Which is why I got an MFA and why I am in a creative writing PhD program. The fact that I have to write poems for workshop, and eventually for a dissertation, requires me to learn to create a writing routine. I have a writing pattern for the year (refer to question #3).

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read read read. Sometimes I’ll pick up a book, and then not be able to finish it, because something in the book inspires me to write. I also like watching movie analysis videos on YouTube.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Probably the smell of white rice and coffee.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music and music videos help me get weird in my writing. If you open up Come Clean, you’ll see that Mitski is a huge influence on that book. When I was writing a lot of these poems, Mitski was the soundtrack for a lot of the sadness I was feeling. I am such a huge fan. When I first saw her in concert, I teared up when she slowly walked out onto the stage. I bought the rights to use lyrics from one of her songs (“Last Words of a Shooting Star”) for Come Clean.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I am indebted to all the writers who are, or have been, a mentor to me. I think Patricia Smith is always in the top 5 for me. Blood Dazzler is a big one I turn to often when I want to study how to put together an entire book. I also look to that book when thinking about persona. I turn to Duy Doan’s We Play a Game because it delightfully plays with both the English language and the Vietnamese language.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to visit Austria. I would also love to work in a writers room. I would be good for a sitcom or animated series where wordplay is part of the humor.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I could’ve been a dentist. I was on track to be a dentist up until 2016. I did a biochemistry degree in undergrad, I studied for the DAT (Dental Admissions Test), submitted to multiple dental schools, and then got one dental school interview.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I guess this could continue on from question 17. After I got that first dental school interview, I had a gut feeling that it wasn’t the right path. I didn’t feel joy. I went to Waffle House with my best friend, Tony, and I asked him what he learned in undergrad. He said, “Do not lie to yourself.” At the same time, I was listening to Mitski’s song, “Because Dreaming Costs Money, My Dear”, which has this idea of following your dreams even though it might hurt.

And the third thing that happened all within the same time, was that my friend, Julian Randall, posted on Facebook about the University of Mississippi MFA program. I reached out to ask him questions about it and then I applied. I had two weeks. I drove to Dallas to hunker down at my friend's apartment, worked on my personal statement and my writing sample, and then I got in.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great book — Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward blew me away, made me tear up.

Last great film — Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings was gorgeous. I also loved Jojo Rabbit .

20 - What are you currently working on?

I have two poetry projects that I am working on. One incorporates asexuality studies and the other is a love letter to Houston’s perseverance.

I have a short story collection that I am editing and submitting to contests soon.

I have a novel that I want to publish in the future and a collection of essays about the Asian-American experience.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 22, 2022

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch, knot body

It does not start the way you imagine. The last breath is the first breath, the lungs stretched to their capacity, and yet too little air makes its way through. The breath hitched, strangers looking back to see you walking towards their backs, quick enough for your shins to stiffen, to forget you have a body long enough to make that last spring and catch the bus before it rushes off.

You sit up straight on the bus seat and avoid the white lady glares, but you’re sitting too straight and looking away with your neck in that crooked way, and you feel it shooting signals all the way down your back. Trading one avoidance for another.

The shame takes a backseat. When was the last time you had the luxury of forgetting about your body? (“Portrait Of A Body In Pause”)

A collection I only picked up recently is Montreal poet Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’sfull-length debut,

knot body

(Montreal QC: Metatron Press, 2020), a title that was subsequently followed-up with their second collection,,

The Good Arabs

(Montreal QC: Metonymy Press, 2021). The epistolary prose poem collection knot body focuses on illness not as metaphor, but writing disability, including chronic and daily pain, expanding the possibility of what has been termed “disability poetics” (following work by Nicole Markotić, Roxanna Bennett, Shane Neilson and multiple others); a body that for merely existing is considered political. El Bechelany-Lynch writes of the many layers and levels of endurance, attempting to comprehend how one might safely and comfortably live within the body. “The pain hovers above an impossible memory.” one piece begins, early on the collection. Writing a pain endured, and even lived, one might suggest. The next piece offers: “I worry that in writing this, I am revealing too much.” Written through a kind of direct and even stark tenderness, the poems of knot body examine the possibilities of a body that exists with constant pain, attempting to negotiate the daily elements of living in a world and culture that perpetually denies their existence. There is something really striking in these prose poems, in the way that El Bechelany-Lynch writes as a way to articulate the self into, if not being, but into an acknowledgment and a belonging; writing themselves into existence that, until this point, perhaps had been pushed into invisibility by just about everyone else.

A collection I only picked up recently is Montreal poet Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’sfull-length debut,

knot body

(Montreal QC: Metatron Press, 2020), a title that was subsequently followed-up with their second collection,,

The Good Arabs

(Montreal QC: Metonymy Press, 2021). The epistolary prose poem collection knot body focuses on illness not as metaphor, but writing disability, including chronic and daily pain, expanding the possibility of what has been termed “disability poetics” (following work by Nicole Markotić, Roxanna Bennett, Shane Neilson and multiple others); a body that for merely existing is considered political. El Bechelany-Lynch writes of the many layers and levels of endurance, attempting to comprehend how one might safely and comfortably live within the body. “The pain hovers above an impossible memory.” one piece begins, early on the collection. Writing a pain endured, and even lived, one might suggest. The next piece offers: “I worry that in writing this, I am revealing too much.” Written through a kind of direct and even stark tenderness, the poems of knot body examine the possibilities of a body that exists with constant pain, attempting to negotiate the daily elements of living in a world and culture that perpetually denies their existence. There is something really striking in these prose poems, in the way that El Bechelany-Lynch writes as a way to articulate the self into, if not being, but into an acknowledgment and a belonging; writing themselves into existence that, until this point, perhaps had been pushed into invisibility by just about everyone else. For some writers, the memoir is a space of control, a way to reveal the facts they want to reveal, to share their stories so others know they are not alone, to share their stories in the hope that they are not alone. I try to learn from other writers, and give small parts of me, dropped into a glaze of fiction, fired twice over until the reality of it all changes colour, a lilac purple into raw clay brown. Charles Baxter says poets don’t particular care about the study of character so I guess he’s never met a poet. Tommy Pico would rip him to shreds. Mix around some random details and turn myself into a character, so far away from me that I can convince both you and I that nothing bad has ever happened to me.

May 21, 2022

Annharte, Miskwagoode

Mothermiss

What is the difference between motherless and mother loss? Probably the time factor involved. Motherless might go on for a long time while mother loss is seemingly a one time event. Being motherless for me happened when I was about nine and my mother disappeared. She had been coming and going since I was seven but the last time I saw her I did not know I would never see her again. She had been to jail and served about a year’s sentence. Before that, she had been going on long drinking binges. I developed the feeling of shame about her absences. My father said nothing much at all to either comfort or give any information about her.

The result was a growing silence what went on for years starting in the fifties. I do remember him saying that she was last heard of as being in Ontario. He mentioned the police suggested he make a formal inquiry. I had been abandoned by her but did not know it exactly. I did not know the terminology that went with either the concept of motherless or mother loss. The motherless aspect took over though I think of it as a time when I did not think that much about my mother. I did miss her but had not cried about her leaving. It had been a shock that had numbed out most of my feelings. I did expect her to return at some time so I did not think of her as being dead or lost to me forever.

The fifth full-length poetry collection from Anishinaabe poet Annharte, a/k/a MarieBaker [see my piece on an earlier collection over at Jacket2], is

Miskwagoode

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2022), a collection composed against a backdrop of loss: “Taken from the Anishinaabe for ‘woman wearing red,’ Miskwagoodeis an unsettling portrayal of unreconciled Indigenous experience under colonialism, past and present.” The collection opens with an introduction by her son, Forrest Funmaker, and another by her granddaughter Soffia Funmaker. “When my coocoo was just nine years old,” Soffia Funmaker writes, “her mother went missing and was never found. She was one of thousands of Indigenous women who are either missing or murdered in what is now called Canada. My jaji (father) named me Soffia and when he told my coocoo the name he chose for me, he said, ‘I hope she can have a better life than her.’”

The fifth full-length poetry collection from Anishinaabe poet Annharte, a/k/a MarieBaker [see my piece on an earlier collection over at Jacket2], is

Miskwagoode

(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2022), a collection composed against a backdrop of loss: “Taken from the Anishinaabe for ‘woman wearing red,’ Miskwagoodeis an unsettling portrayal of unreconciled Indigenous experience under colonialism, past and present.” The collection opens with an introduction by her son, Forrest Funmaker, and another by her granddaughter Soffia Funmaker. “When my coocoo was just nine years old,” Soffia Funmaker writes, “her mother went missing and was never found. She was one of thousands of Indigenous women who are either missing or murdered in what is now called Canada. My jaji (father) named me Soffia and when he told my coocoo the name he chose for me, he said, ‘I hope she can have a better life than her.’” Across a layering of shifting form, Annharte’s Miskwagoode offers a collision and cadence of words that flow across possibilities, writing of violence, grief and addiction, and the loss of so many through the legacy of colonial trauma. “where goes this naked ndn // not born Indigenous without,” she writes, as part of “Jack Identity,” “blue mark on bum // fail to act indifferent // national inquiries hold on [.]” The poems explore form, identity, community and “a backdrop of unreconciled realities within Indigenous experience,” from prose bursts to poems set as layered accumulations of staccato phrases, all set as disjointed descriptives across a documentary poetics she’s been crafting for years. “explain what is possible,” she writes, to open the poem “Better Yet Explain,” “for right now create / street surveillance position / post qualifications / employ non-gloved hand / feel out resistance / anticipate interference / from driven class interests / encourage cultural revival / lessen neo-liberal outreach [.]” And, as much as she presents herself as the documentarian, she sits precisely within the scope of her poems; more than simply an observer, she offers commentary, advice and option, neither passive nor unbiased, but deeply invested what is happening, and what should be happening; the ways in which things need to improve, both from without and from within. One might claim this, in the end, a book of deep grief and honesty, and how healing (and reconciliation) can only emerge through a true acknowledgment of the devastation wrought through colonialism. Moving her lyric across a landscape of mourning, the tone of her poems shift slightly in the final section, “Wabang,” through a suite of poems composed as prose declarations, and even calls-to-action. The poems are hopeful, engaged with a playful wit and gymnastic cadence, composing a blend of sound and storytelling to provide something to hold and hold on to.

Down with Big Stink

Fight takes Giant Skunk down Wolverine held squirter but tail still up

Pressurized spray got right in his face dirty job somebody would do

Suspicious vibrations why Great Skunk followed animals escape after

They cross his path broke rule so they made a stand special bear song

Ask help to take out big bully after all Wolverine washed his face at

Hudson Bay explains why salty dirty water why Winnipeg so named

May 20, 2022

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lisa Moore

Lisa Moore

is the acclaimed author of the novels Caught, February,

Alligator

; the story collections Open and

Something for Everyone

; and the young-adult novel

Flannery

. Her books have won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and CBC’s Canada Reads, been finalists for the Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize and been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Lisa is also the co-librettist, along with Laura Kaminsky, of the opera February, based on her novel of the same name (2023). She lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Lisa Moore

is the acclaimed author of the novels Caught, February,

Alligator

; the story collections Open and

Something for Everyone

; and the young-adult novel

Flannery

. Her books have won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and CBC’s Canada Reads, been finalists for the Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize and been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Lisa is also the co-librettist, along with Laura Kaminsky, of the opera February, based on her novel of the same name (2023). She lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was Degrees of Nakedness, a collection of short stories published by Mercury Press. When some copies of the book arrived at my house, in a cardboard carton, wrapped in paper, I remember thinking they were wholly magical objects. Completely magical. Beverly Daurio was an amazing editor. The edits came in the mail with her handwriting on the manuscript. She was careful and exacting and generous. All of that work, the mailing back and forth of stories, and all the writing and rewriting, so neatly contained between the covers of a book. I realized how many people make a book come together, how many people it takes to get a book out in the world. And of course, readers. Each reader makes the book come alive by reading it, a different book in each pair of hands. It was astonishing to think that someone I had never met before could read my thoughts, know my sensations – the intimacy of that. It felt supernatural. I still feel that awe – about imagining a story, the engine of the story revving up, and the transmission of it to readers. And how is the experience different now? I’m not sure it is different. I experience the same mystery about the process, the same thrill.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I read novels for children and young adults, and then the older stuff, for a long time all I read was fiction – Black Beauty, Five Little Peppers and How They Grew, Little Women, all the Judy Blume I could get my hands on, gothic romances, Franny and Zooey, Thomas Hardy, DH Lawrence, Tolstoy, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, The Tin Drum, Toni Morrison, the Carry-on novels about stewardesses, Love’s Tender Fury, Roots, James Baldwin’s Go Tell It On the Mountain, The Thornbirds, Tolkien, CS Lewis, – I was indiscriminate. I just read whatever fell into my lap. It didn’t matter what the books were about, or when they were written, or if they were good or not, they were all excellent! As long as they were engrossing, elaborate in terms of character development, big stories with lots of landscape and if at all possible, horses galloping through, big fat doorstoppers, or slim things, like Raymond Carver’s stories - it was the act of getting lost in them, as many as I could get my hands on – starting when I was probably 9 or 10, to really fall headlong into short stories and novels. I just love the drama of fiction, the suspension of disbelief it demands, giving over to an imagined, made-up world. And I loved writing it, even as a kid. Trying to make a story convincing. I loved that it was imagined. That I was investing in something that didn’t actually exist.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I usually jump right into another project as soon as the last one is done and dusted. I often start with an idea. The shape of a novel changes dramatically over the years it takes to write. I write long hand in a journal every day. I try to write scenes, things that happened the day before. I try to write the way people move, the gestures they make, the way a particular person looks when they think, when they chew, when they sleep. And if I get close to capturing a gesture, I will attribute it to a character in a novel or short story. I remember reading in an Anne Enright novel about a character washing her face, cupping water in her hands and splashing her face, and the water running up her forearms, up the sleeves of her shirt. Enright did a better job of describing it, but every time that happens to me, water running up my sleeves, I think of Anne Enright. It’s that kind of detail in writing that makes us aware of our own experience, so that we live with more attention to the sensations and feelings that make and remake us, on a daily basis, minute by minute.

I love travelling, and on a train or bus or airplane really studying the person beside me and trying to guess who they are, in the very marrow of their bones, just by the way they look and move. Often, when I speak to them, even briefly, I learn that the whole edifice I have built up around them in my imagination - based on their perfume, whether their hair is long or short, if they fall asleep with their mouth hanging open, giving over wholly to a dream – often I learn that I was entirely wrong. That the person is not in fact a tourist who only speaks English, but is, instead, French, and has a problem with her car, and hangs up her phone without saying good-bye, and speaks emphatically, explaining to me, I have to get off at the last stop, which, she says with great solemnity that I hadn’t guessed was coming – is the end of the ride. I love being proven wrong. But I also love it when I’ve imagined a glimmer of the truth of who a stranger might be. It reminds me, that since we are all changing, all the time, we are all, in some ways strangers to each other, and ourselves. And we have to stay attentive in order to catch even a filament of truth about our lives. But I won’t even try to think about what truth is – I’m a fiction writer!

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I love writing short stories, because they demand you jam a whole world into a few pages. This Is How We Love grew from a short story. Usually though, a novel starts from a fragment of an idea about a character and requires scene upon scene to make that character feel alive, solid, full of bones and blood.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing readings. I love sharing a story with a live audience, I love the tug-of-war, pulling them into the story, or maybe losing them and pulling harder, or more softly. I love the give and take with an audience, feeling them absorb the story, maybe laugh, or get tense. It makes the story feel like a living breathing thing.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I think about the tactility of language, how it is a material. And I think about whether the texture of the language is in the foreground or background of the drama in the story. Is the reader aware of the rhythm of the sentences, of the kind of vocabulary the narrator is using, of the distance between the narrator and the unfolding action of the story. Is the fabrication of the story laid bare for the reader, so they don’t feel duped? And I am interested in what makes a novel or story. We crave a kind of unity, as readers. Like walking into a house where the rooms feel like they have a satisfying proportion, something almost impossible to articulate, but a size and shape that is right for the human body, that gives a sense of being held and sheltered, but provides an airiness, space enough to live a life. The shape of a story or novel is like the architecture of a house, a human scale, I sometimes think. Other times I think a story or novel has to break down all the walls of such a house, or such a shelter, and instead, make the reader uncomfortable, so uncomfortable that the things that they have held to be true must be questioned, maybe abandoned. I don’t think any of that while I’m actually writing – I just write. I probably don’t think those things even when I’m rewriting – not consciously. But later, much later, when I read other books, and when I consider things I’ve written in the past, think about the shape of the story, ask myself if the story held the reader, and also, if it sent the reader outside into the raging storm.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer might be able to make the reader feel deeply, question assumptions, and act with generosity. Fiction (maybe) has the ability to hone the imagination and it’s with imagination that we can hope to get ourselves out of this mess (maybe, or maybe it’s already too late? Does fiction then, prepare us for the end?). A good story makes us recognize the complexity, the brevity, the depth of our experience, and with any luck, helps us share, teaches us to love. Tall order. If fiction fails at all that, maybe it allows us to experience beauty, and I think beauty is radical. Beauty changes everything.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have been very, very fortunate in having the very best editors in the whole world. Beverly Daurio, Martha Sharpe, Lynn Henry, Sarah MacLachlan and for the last four books, Melanie Little. They are all geniuses, as fate would have it. And also, beautiful people. I am eternally grateful to them. There have been editors at various magazines too, who have edited short stories of mine for publications. I have never had a bad experience with an editor. I am just felled by gratitude.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Listen.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think stories come in different lengths. Some stories swoosh through in an instant, a flood of feeling, a revelation. And some cover a bigger geography. I’ve written a few novella too – and I love that length, it’s kind of a cheat, you get the best of both worlds.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I get up at five and write then. I don’t look at email or the news until later. I reread what I’ve written – not necessarily from the day before, I can read from any part of the story or novel to re-immerse myself. I try to write without stopping for about two hours. I don’t think I should write for two hours – but when I look up from whatever I’m doing, two hours have gone by, eaten up in a millisecond. When I am working on edits I can work for hours and hours and it gets dark without my noticing. I need to walk after a two-hour stint. Walk really fast.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read authors whose sentences feel like nobody else’s sentences. Those author’s whose voice I can hear, even though I’ve never heard them speak in real life. A paragraph or two of those authors, and I am ready to get back at it.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Orange spruce needles on the floor of a forest.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I like to paint and draw. I’m interested in the quality and texture of the mark. I love the physical energy that goes into a drawing or painting, especially if its big and you have to stretch to cover the paper or canvas, stand on tippy toes. Or if it’s lying on the floor, walk around it.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I teach creative writing, so the work of my students is very important to me. Just the aliveness of it, and how it belongs to the moment, how they are capturing such varied representations of this time and this space. Everything fresh, new.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Grow or forage all my own food. Or…grow anything edible, just once! I’ve got some rosemary started! Wish me luck!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Fashion designer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was obsessed with writing, for as long back as I can remember. It was always what I wanted to do.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Paul Takes The Form of A Mortal Girlby Andrea Lawlor – this is a raunchy, hilarious, stunning novel that completely upended every thought I had about gender. Film? I watched Pedro Almodovar’s Madres Paralelas recently. It is haunting.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just gave a talk about climate crisis and genre fiction, the use of the supernatural to make us face up to the damage we’ve done to the earth, Freud’s idea of the return of the repressed, all those fears we bury really deep, but burst back up in different forms, to overpower us, despite our best efforts to shove them back down, how ghosts in Victorian literature never wander far from whatever castle or mansion or abbey they haunt, how ghosts are chained to the place, but that global capital is unfettered and roves all over the world free of the chains of say, oil clean-up, or fair labour practices or environmental restrictions easily brushed out of the way. How oil is buried too, how it is perhaps our worst nightmare, how digging it up might haunt us forever. How oil rigs are like gothic castles, with their soaring heights, and fragile looking spires, and how they are already ghostly, because this can’t go on for much longer folks. In case it’s not immediately evident, this talk still needs work!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 19, 2022

Prathna Lor, Emanations: Poems

I write endlessly in the register of prayer

Inside of my voice is our sound

Thinking the fractures

Where I emerge

From every monument

Listening for my footsteps

So, unloved – can the body ever speak? (“ON SEVERAL SERENADES FOR BENEVOLENCE”)

The full-length debut by Prathna Lor, following the chapbooks Ventriloquism(Future Tense Books, 2010) and 7, 2 (knife│fork│book, 2019) [see my review of such here], is Emanations: Poems (Hamilton ON: Buckrider Books/Wolsak and Wynn, 2022). Emanations is constructed as a triptych of suites—“ON SEVERAL SERENADES FOR BENEVOLENCE,” “RED BEACON” and “PEDAGOGY OF RIDICULOUSNESS”—each assembled as accumulations of lyric fragments, halts and hesitations stretching the boundaries of narrative and connective tissue, moving forward without clear endings or closures. “Think like a painting.” Lor writes, to open the second section. There is such an openness to Lor’s ongoing, meditative lyric, one that wrestles simultaneously with spirituality, self-determination and the boundaries of commodification, as the opening to that second section continues:

In a cavern before a headless Buddha, heads stolen and sold, now common as decoration, where refuse was lost because the cities were emptied, because labour triumphed over thinking, over beauty. Because it was in the name of the people. I hear the serpents’ call. They cloak the Buddha, shading reverie.

I follow the agony as a descendent of the viper.

Cadmium can be a beautiful word. And I a bang.

Lor writes across the contours of self-creation and discovery, articulating values of both the collective and the personal, and the ways through which so much is lost through commodification. “How a poem / never lies,” the second section offers, “only / dilutes what is given to speak / what is given to breath [.]” Later on, in the same sequence-section: “And there you are thinking light / an incomplete fabrication / moved by a pronoun / I am living, finally, / because I learned the death in the line [.]” Lor’s lyric presents a metaphysics of concrete language, writing out the nuts and bolts of the space where language speaks, and not only informs but holds meaning. “You can dream in another tense.” Lor writes, as part of the second section. In Lor’s 2020 interview via Touch the Donkey (which offered a slightly different title of their full-length forthcoming than what emerged), they offer:

The difficulty, again, for me, is thinking about the breath of the poem, the work of voice and reading, over a longer period of time, or via a larger scale, when the poetic tenor I am trying to explore is so punctual, economical, propulsive. Rhythms and intensities would have to change, modulate, etc., but, of course, over the course of one’s life, I feel as though it is a single line, a single rhythm, towards which I am relentlessly returning, and I suppose that part of my anxiety about sustaining over time/distance is the fear of it dulling over each reiterative sensation.

May 18, 2022

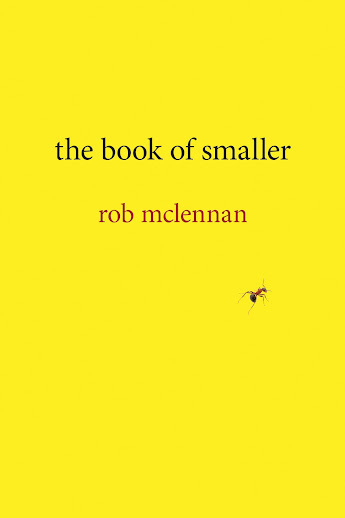

the book of smaller : now available!

my latest poetry collection, the book of smaller, is now available from the University of Calgary Press! hooray!

my latest poetry collection, the book of smaller, is now available from the University of Calgary Press! hooray!#25 in the "Brave and Brilliant" series over at the University of Calgary Press, which might also be my twenty-fifth (or so) full-length poetry collection (but who can keep track, really).

and a collaborative review has already appeared, writ by those brilliant and lovely people Kim Fahner, Margo LaPierre and Jérôme Melançon!

https://periodicityjournal.blogspot.com/2022/05/kim-fahner-margo-lapierre-and-jerome.html

and did you see this interview with me that Lisa Fishman conducted, recently posted over at Court Green? https://courtgreen.net/issue-20/rob-mclennan-interview

i do have copies of the book on-hand, if anyone is interested ; if such appeals, send $20 (via email or paypal to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com) ; obviously adding $5 for postage for Canadian orders; for orders to the United States, add $11 (for anything beyond that, send me an email and we can figure out postage); for above/ground press subscribers, I'm basically already mailing you envelopes regularly, so I would only charge Canadians $3 for postage, and Americans $6 (that make sense?)

or: if you live close enough, I could simply drop a copy off in your mailbox (or you come by here, I suppose)

or you can order direct from the publisher! (that's really what you should be doing, yes?)

https://press.ucalgary.ca/books/9781773852614/

although I've heard that it isn't easy/possible to order into the United States from the publisher's link, so I'd offer (unfortunately) the amazon.com link:

https://www.amazon.com/book-smaller-rob-mclennan/dp/1773852612

hooray books! and keep in mind I am very good at answering interview questions; if you wish for a media copy for potential review or interview, let me know and I can put you in touch with the publicist.

stay healthy out there,