Louise Dean's Blog, page 15

August 29, 2020

Back to School for Writers at The Novelry. Our Writing Classes.

The Autumn Term Starts 7th September.

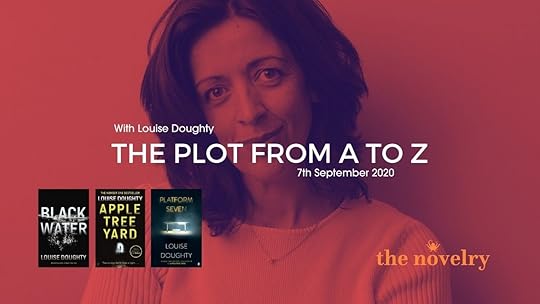

We will be kicking off with a week on plot, with some plot-busting tips, a worksheet and a special boot camp Monday 7th September with the author of Apple Tree Yard, the redoubtable Louise Doughty. Members can sign up at our class booking page here.

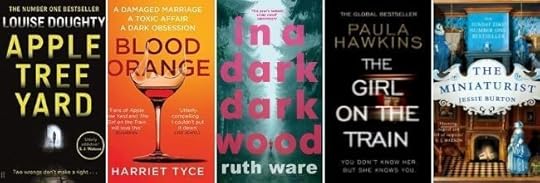

The immersive programme of events for this writing season at The Novelry includes live sessions with former Publishing Editor of Penguin's Doubleday imprint Marianne Velmans and guest tutors, bestselling authors, Louise Doughty, Harriet Tyce, Ruth Ware, Paula Hawkins, and Jessie Burton.

If you join us in the first week of September, you'll have 7 relaxed and inspiring days of lessons in the Ninety Day Novel course to consider and hone your idea, before your first tutor session.

At that first session, we sign off on together on the best idea to achieve your goal, and you start writing. You could be holding your novel manuscript in your hands on the 1st December. Sign up now and experience the joy of completing the first draft of your novel this year.

Happy writing!

Our Events.

This autumn the focus is very much on PLOT. Our guest tutors have been chosen for their crafty expertise and plot wiles.

Our writers can sign up at our class booking page here.

The Louise Doughty Boot Camps. September, October, November.

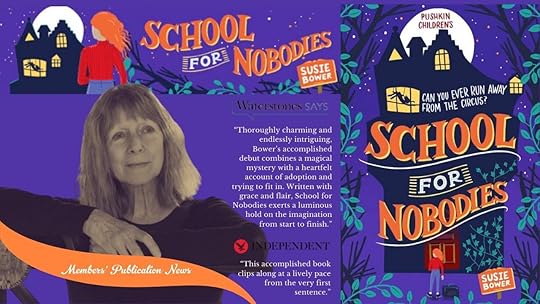

Writing for Children and Getting Published With Graduate of The Novelry, Susie Bower.

A Live Q&A With Former Publishing Editor of Penguin Doubleday, Marianne Velmans.

Writing a Bestselling Suspense Thriller With Harriet Tyce Monday 21 September.

A Q&A With International Bestseller Thriller Writer Ruth Ware 19th October.

A Q&A With Global Bestselling Author of The Girl on the Train, Paula Hawkins 16th November.

A Live Session with Sunday Times Bestselling Author of Historical Fiction Jessie Burton 14 December.

And our regular sessions for all members every two weeks:

The Story Clinic. (Tues 1st Sept at 3pm UK time, Tues 15th Sept, Tues 29th Sept and so on) with our tutors on rotation to troubleshoot our writers story problems.

The Sunday Evening Team Chat. Every other Sunday (August 30th, Sept 13th, Sept 27th and so on.)

And don't forget you regular one-to-one session with your tutor!

Book in advance for sessions by Zoom at our booking page here.

Wishing you all happy writing this autumn.

Lost the Plot?

If you have been and are still creating material at first draft stage of your novel, carry on regardless. Get it down, and continue with your steady writing regime, and well done!

If you have had to take time away from the novel, you should use this opportunity to look at your novel from a distance and be a little rude and rough on it. Take a helicopter view and look at the market and marry what the market is loving to your intentions for your novel. (You might as well get readers, right?)

This is where we begin work with all of our writers - what are your intentions and ambitions, how do we best align this to publishing success?

You are the author. You remain in the driving seat, either agreeing or rejecting the suggestions of others because fiction, like fortune, favours the brave and your novel is the only place in your life you get to exercise your own authority. But we will always give you our best advice for you to find a way to make a life writing books.

Fast Tips:

Many writers come to us with a novel that needs a major reboot. Many come with nothing, not even an idea. Either way, these things ought to be top of your list. (If your novel hasn't found an agent yet, the problem may be here.)

Go first person or very close third for perspective or point of view. Omniscient perspective is a passion-killer in 2020, it's old school. This fashion will pass, and one day we'll all be writing like Tolstoy again, but for now, if you want to get published be up close and personal with the reader.

Voice. It's so very much about voice these days. Look at the big hits of this century - The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz - is often ranked as the novel of the 21st Century. These novels draw on the heritage of The Catcher in the Rye. Sorry, but you have to locate it and channel it. It could take a while, even a few drafts to hear it. Ideally, you know it. It needs to be close to home. Don't fight or write with one hand tied behind your back. Use all your strengths and gifts. Bring it closer to home.

The Big Question. What are we reading to find out? It's okay to change this as you work over numerous drafts, but when you're moving to final drafts of your novel, make sure we know this on the first pages.

The Stakes. Are they high enough at the outset for us to care? Life and death, my friends, life and death.

Cause and Effect. Not every writer is much good at this logic flow. This happens, so that happens. See this blog on What is Story? for a guide. And it's okay to have fluffed it in early drafts entirely when creating material with whimsy. But use the re-boot of September to be brutal. I will be working with my writers to nail this as a priority in September at our monthly boot camp with the wonderful Louise Doughty and will be providing all of you writing with us, with a worksheet. It should be easy, but it's not. All of my writers can write, I don't doubt you reading this can write, but very few of us can nail the this-then-that of storytelling which seems such basic mathematics. I am weak with this personally, therefore I love the lifetime, ongoing learning we share at The Novelry which keeps me on track.

And a bonus tip: Conflict and Theme. A writer who is acquainted with the wonderful Tayari Jones who wrote An American Marriage (read it!) told me that one of Tayari's great skills is the way she deliberates over the selection of the conflict in her work, taking time to find it. Then she writes cool and clean. (Because you can, once you know it.) What's the conflict in yours? Why is it timely or important? How does it speak to the theme of your work?

The tutors of The Novelry invite all of our writers to come to our virtual desks in September for a re-boot session and to talk through, plot point by plot point, the story, story, story.

See you in class.

Now's The Time.

(September Comes But Once a Year.)

When you sign up to write your novel with us, we're here to take on some of the heavy-lifting of writing your novel. We keep on track with your novel during your writing with our amazing system which tracks your progress and storyline alongside you as you go. Not only that we keep tabs on how you're feeling. So when you sag or lag we can intervene to give you a morale boost.

The course is structured to build your confidence and word count daily with regular interventions with your tutor. Our method is to encourage and support even the faintest glimmer of an idea, to see what's great in it, to help you honour your ever-so-slightly mysterious intentions at outset and achieve your ambition. We urge you not to share your precious but quite naturally flawed work at first draft with anyone but your tutor, who believes 100% in you and your idea. Once we have a draft in the bag, it's all systems go at The Novelry to lift it to publishing standard. We need that draft in the bag. Once we've got it, we can start making it into a piece of art fit for publication. Your confidence and joy is top of our To Do list, and that's what makes The Novelry a very special place, a haven for many wonderful writers.

We live and breathe the magic of the white page and the craft of making marks on it, conjuring a spell that transports writer and reader to another time and place where anything could happen...

Yes, I want to start and complete the first draft this year.

August 22, 2020

Dual Timelines (Part 2.)

Dual Timelines - Part Two. From the Desk of Katie Khan.

In the very beginning, when I experienced the first gleam of an idea during a nap in my parents’ attic, my debut novel Hold Back the Stars was to have only one timeline. A couple were falling through space with only ninety minutes of air remaining, I imagined, and as they fell, they talked about their relationship and how they came to be in the great vacuum of space. I queried myself – could they be treading water, surrounded by sharks, would that be easier to write? I lived on a hill in north London surrounded by sky, obsessively tracking the International Space Station each night as it passed overhead. No, I decided, it had to be space. But the idea felt quite thin; perhaps a (long) short story or a novella. It was only when I came up with the second timeline – that same couple’s entire relationship, shown chronologically as it happened on the Earth beneath them – that I knew I had enough for a novel.

Many dual timeline novels fall into the historical fiction category: one timeline set in the past, often during the war; the other in the present day. The dual protagonists might be relatives – a grandmother and granddaughter, say, or a modern-day sleuth exploring what happened at a particular moment in history. So while my speculative fiction might be considered an unconventional dual narrative, I learned a lot about what it means to balance and craft a story that takes place in both the present and the past.

Why is it worth considering? Because dual timeline is an extremely commercial structure for a contemporary novel. In Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, an elusive actress towards the end of her life recounts her golden years in Hollywood to a young journalist, revealing the true love of her life. (If memory serves me correctly, a man also recounts his incredible survival story at sea to a journalist in Yann Martel’s Life of Pi. And a vampire to a journalist in Ann Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. What a great formula!) In Abigail Dean’s forthcoming Girl A, optioned by the director of Chernobyl and publishing next year with Harper Fiction, a novel already touted by her publisher as ‘the novel that will define a decade’, a girl who escaped horrendous childhood abuse at the hands of her fanatical parents, must confront what happened to her and her siblings in the famed ‘House of Horrors’ after the death of her mother. The novel shifts back and forth in time between ‘Girl A’ as an adult, and the girl as an imprisoned child.

Whether you are writing two equal timelines that form 50:50 of your novel, or a plot that requires flashbacks or backstory, there are some key considerations to take into account:

Both timelines must be equally compelling, or a reader will flick through one to get back to the other. Worse still, they’ll put the book down;

The moments where you choose to cut from one timeline to the other are the number one generator of tension and suspense in the story;

What you reveal in one timeline shows us a truth in the other. Plus, the impact of one timeline is felt in the other. Cause and effect.

The more separate your two timelines are, the more ineffectually disparate, the less successful the storytelling. Dual timelines as a device exist to create connection, to demonstrate the impact one generation can have on the next, or to show us how the echo of the past is still heard in the present.

The writing process

You have a couple of choices here. You could draft your two timelines separately, then interleave them in the edit. I’m sure you can guess by my slightly cynical use of italics that I don’t personally recommend this. It’s nigh-on impossible, except for the most gifted writers, to lose the silo feeling of two stories told separately. Instead what I recommend (and how I wrote Hold Back the Stars) is to write your timelines already interleaved, an alternating story unfurling as one. This can take a bit of plotting. You might balk at a spreadsheet, but a scene list will be invaluable (particularly when it comes to the many edits down the road). Consider colour-coding: Storyline A, Storyline B. Where do you get in and out of each storyline? Leave us on a cliff-hanger, so the reader longs to return to find out the ‘answer’. And what is the trigger or the transition that sends us tumbling towards the other timeline?

Transitions

This, for me, is one of the key techniques for writing dual timelines. Some stories work well to create structural boundaries between the two plotlines. Chapter 1: storyline A. Chapter 2: storyline B. Other novels, particularly those dealing with memory, backstory or flashbacks, work even better when the transitions between the two timelines are seamless. Both timelines lie alongside each other on the page, bound together within the same chapters. Remember Sally Rooney’s ABA structure in Normal People: action-backstory-action. Or for me, in Hold Back the Stars: present-past-present. (Potato, potato – these are the same thing!)

Consider this transition in Richard Yates’ iconic 1960s novel Revolutionary Road. This isn’t a dual timeline novel, but rather the portrait of a failing marriage, and it presents a beautiful juxtaposition of the romance of first love against the sagging weight of a long, difficult marriage. In chapter one, we sit with Frank Wheeler in a suburban am-dram theatre, watching his wife April perform badly in a terrible local play. A fraction of a moment later, we are watching a sparkly-eyed Frank meet April for the first time at a New York party. When I was writing my debut, I spent weeks looking at this. How did the author do it?

Frank drives a crushed and embarrassed April home from her disastrous play, the couple heading towards a major argument:

“With a confident, fluent grace he steered the car out of the bouncing side road and onto the hard clean straightaway of Route Twelve, feeling that his attitude was on solid ground at last.”

As Frank drives, we are flung years back, to their first meeting:

“And now, as it often did in the effort to remember who he was, his mind went back to the first few years after the war and to a crumbling block of Bethune Street, in that part of New York where the gentle western edge of the Village flakes off into silent waterfront warehouses, where the salt breeze of evening and the deep river horns of night enrich the air with the promise of voyages.”

Frank and April meet at a party, and then:

“a week after that, almost to the day, she was lying miraculously nude beside him in the first blue light of day on Bethune Street, drawing her delicate forefinger down his face from brow to chin and whispering: ‘It’s true, Frank. I mean it. You’re the most interesting person I’ve ever met.’

‘Because it’s just not worth it,’ he was saying now, allowing the blue-lit needle of the speedometer to tremble up through sixty for the final mile of highway. They were almost home.”

A few pages of flashback and we’re right back in that car with them, about to get into the mother of all fights. There weren’t even line breaks to separate the scenes.

Let’s dig into the ‘how’. The word ‘now’ jumps out a mile, twice, establishing each timeline. See how Richard Yates gets us in late and takes us out early – April is mid-sentence in that last dialogue line to Frank, after their first night together; Frank is mid-sentence to April, in the first dialogue line back in the car. Notice, too, the entire transition takes place in a travelling car, mirrored and echoed with the line ‘the promise of voyages’ in the past timeline of Bethune Street. This is important; like a memory triggered by a scent or place, using reflected imagery between both timelines eases the shift between them. I used this myself in Hold Back the Stars, when Carys and Max are falling in space above the Earth, watching the sun rise across a continent; the next scene on Earth is a sunset beneath which they decide to break up.

Tenses

The experience of writing my own ABA structure of past-present-past was a little bit trial and error, but I hit upon a technique that seemed to anchor the reader, so it was always clear which timeline I was dropping us into. My publishing houses (Doubleday/Penguin Random House in the UK, and Gallery/Simon & Schuster in the USA) assisted with this clarity in the typesetting of the book, by separating the Earth and space scenes with a dividing symbol of a star, though I had written the transitions often without line breaks at all – heavily influenced and inspired by Revolutionary Road! This level of clarity for the reader (where and when am I?) is particularly important if your dual timeline contains the same characters in both, and less essential if your dual timeline features separate characters, for example the grandmother and granddaughter.

I wrote my present timeline, unsurprisingly, in present tense. I wanted the reader to feel the immediacy of their dire situation, the helplessness of Carys and Max fighting to survive, oxygen levels ticking down in every scene as they try and fail to save themselves:

“‘We’re going to be fine.’ He looks around, but there’s nothing out here for them: nothing but the bottomless black universe on their left, the Earth suspended in glorious technicolour to their right.”

But Carys and Max’s relationship on Earth, which were memories, are written in past tense:

“He had left the dinner party around midnight and she’d seen him to the door, leaning against the frame, her arms huddled inside her cardigan against the chill. ‘Thanks for tonight,’ he said.”

Here’s the technique, which I recently found summarised perfectly in the marvellous 2019 book Dreyer’s English by Random House copy chief Benjamin Dreyer. My word, how I wish I’d had that book to hand as I’d laboured through the transitions of my first novel and discovered a version of this method for myself.

Two or three “he/she/they had”

Abbreviate down to “he’d/she’d/they’d” once or twice

Then switch to simple past tense – dialogue is a good place to do this (“he said”).

Foolproof. Lovely stuff.

But what if you’re not writing dual timelines? Is any of this useful? The short answer is: yes. I’m currently writing a novel with alternating perspectives from two different characters, and the experience of writing a dual timeline novel has been invaluable in showing me how to handle the shifts. The first list of bullet-points in this blogpost all apply if you’re writing a multi-POV story: both (/all) arcs must be equally compelling; the moments you choose to cut away generate the driving tension and suspense of the novel, and what happens in one arc should reveal a truth in the other.

Best of luck if you’re writing dual timelines – I cannot wait to read them, and I hope these techniques assist with the push-pull of balancing your two interwoven narratives.

Happy writing,

Katie

August 15, 2020

Dual Timelines

Dual perspectives on 'Dual Timelines' from two of our tutors. This week, Louise Dean, next week, Katie Khan, the flipside.

Dual Timelines - Part One. A View From the Desk of Louise Dean.

I've worked with dual perspectives before. In my historical novel, This Human Season, I told the story set during The Troubles in Northern Ireland chapter by chapter, alternating between a former English soldier prison guard, and a Catholic mother of one of the prisoners. I wanted to show how the two sides had much in common by running them alongside each other to tell the story of the events leading up to the Hunger Strike. The story came first, and I told it blow by blow, with the timeline in 'real-time' for both parties, day by day. The structure of your novel can serve its theme, it should serve its theme, and it can almost perform the theme.

This time, I'm writing a novel with dual timelines. I didn't mean to, I confess. I had a story drafted out in contemporary 'real-time', told in chronological order, but a character emerged, the grandfather of my hero, and I wanted to show the way our family history weighs on us covertly, from the use of phrases handed down, to an attitude or approach to life. An inherited 'coping strategy'.

This has given me the opportunity to expand the theme of the novel from one person's quest for meaning, to a re-interpretation of what it means to be a 'hero' context and look at the mythology of heroism in the Twentieth Century. In a low brow way.

I'm looking at the person who resists, not through courage but uncertainty, and blithe contentment with what they have, in a 'bubble', and how such inert resistance is not always a bad thing. Call it complacence, call it stoicism. I'm showing how much good the person without ambition can bring to the world. Yes, it's comedic. And I want to show it through the generations of one American family, whereby the original impulse of 'betterment' whimpered and died on Ellis Island in 1896.

I hope I am bringing 'bathos' to the American dream. I guess that's the dance here. I'd love it if Alan Bennett wrote a Western... Not so much The Magnificent Seven as The Modest Seven (with much to be modest about.) In my story there's the same dying fall of bathos from the grandiose to the humble - in a hop (across the pond) a skip (participation in the first American imperial war - the Korean War) to a jump (making model automobiles to avoid noticing you're being robbed.)

As an example of bathos, British darts commentator Sid Waddell was famed for his one-liners, including this example:

“When Alexander of Macedonia was 33, he cried salt tears because there were no more worlds to conquer..... Bristow is only 27.”

It's not easy writing a dual timeline novel; it's heavy lifting. I'm weaving into the novel the story of three generations and pairing content chapter by chapter so that the past amplifies the present. I've structured both stories along the lines of the story structure we teach at The Novelry - The Five F's - and am doing a preliminary draft of insertions. (I had done five drafts of the first story.) I like what it's bringing to a deeper understanding of the present tense story, but I'm finding it challenging as the historical story packs more clout, largely as I move across time more boldly, wrought in first person. The second story - the historical family saga - is leading me by the nose, moving ahead of me, and I feel like I'm hanging onto the pram with my knees being grazed on the ground as we go.

I'm going to be spreading that manuscript on the dining room table and examining the connections and cutting with a pair of scissors to ensure one chapter kicks the other right up the backside, and to bring to it the mystery of a few token 'icons' handed down, and catchphrases too, as well as parallel events treated with the same naive and hopeful ineptitude by grandfather and grandson. And yes, I need a linking device, a rationale, and this conceit is that those who love us never leave us, and are present if invisible. A personal Jesus, or a poltergeist.

From my experience, stories happen outwards in ever-increasing circles, draft by draft. I'm a worrier, a dog with a bone. One of my maxims is - if it seems hard, make it harder. What I mean by that is being tough enough to find the single-minded theme, a story elegance, that requires some roughing up of the material, and tough decisions; some junking and cold-shouldering of 'cute' in favour of 'purposeful'.

I certainly never expected to be at first draft at the fifth draft. But when you start asking silly questions, you start getting silly answers. What was life like on a USS naval carrier in 1950? Every week confounds me with another hard question. But I wake to visions of someone watering the lawn of a home that never existed, and she turns and says something, and I ask - who? Who is that? And we're off on another wild goose chase... Expanding and contracting, conjuring and reigning myself in, I revise my plan weekly.

No doubt there are better ways. Most storytelling on TV series drives suspense by featuring dual timeline techniques, as flashbacks or flashforwards. The point is not to let either of the timelines run away from the thread of the story, never to lag so that the reader need not care what happens next, and to ensure the event in one serves the other and the story.

In Vonnegut's multiple timeline novel Slaughterhouse-Five, the cutting is done with a sharp knife. At one point we have Billy Pilgrim about to address an audience of optometrists in 1961 and he opens his mouth to speak, and we're back in 1946.

'Listen, Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.' He is abducted by an alien species, Tralfamadorians, who are able to see all of time. They explain that instead of experiencing the linear progression of time like the rest of humanity, Billy can experience events out of order, and eventually choose parts to relive. (This is how fiction works!)

‘The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one.'

Slaughterhouse 5. Kurt Vonnegut.

Despite his many attempts to write about Dresden in the twenty-four years between the end of the war and the publication of Slaughterhouse-Five, it was not until very late in the writing process that the novel included so much of what has made it famous, including its shifting chronology, its science fiction tropes in the form of the novel’s alien race (the Tralfamadorians), and its central character, Billy Pilgrim.

The structure served the theme of the novel. It was important to blend events, and create a chaotic (and real) experience of how we consume life in the present on a continuum of the past and the future, memories and projections.

The treatment for the novel is bathos, the heroic reduced to the ridiculous so that the fatalistic theme plays out through story and prose.

'The same general idea appears in The Big Board by Kilgore Trout. The flying saucer creatures who capture Trout’s hero ask him about Darwin. They also ask him about golf.'

Slaughterhouse 5. Kurt Vonnegut.

Ask yourself, how your structure serves your theme?

In my scheme, the past weighs on the present, all its myths and corners and secrets are there, and sometimes we catch sight of them out of the corner of our eye or in a dream, but the past weighs upon us privately, invisible to the outsider. So my second story, the family saga, no longer the pretender to the throne, must have its sway and bear down upon the present.

What's your structure and why?

Something to discuss with your tutor at The Novelry at your next chat?

Dual Timeline Novels to Explore:

Most dual timeline novels depend on diaries or letters. I didn't want to do that! Here are three others which resist that device:

The Time Traveler's Wife - Audrey Niffenegger

The Silent Patient - Alex Michaelides

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox - Maggie O'Farrell

All the Birds Singing - Evie Wyld

Next week, Katie Khan gives us the other side of the story, a rather more elegant approach to creating dual timelines from the outset. See you then, unless you're reading this in the future and wish to read both blogs side by side?

August 8, 2020

Creating Atmosphere in Fiction.

From the Desk of Emylia Hall.

We were lucky to have a live session with suspense writer Kate Hamer at The Novelry recently. Kate spoke about the importance of creating a potent atmosphere, particularly in the opening chapters where we’re really focusing on drawing the reader in. She told us that a childhood favourite of hers was Treasure Island, and how she remembered the arrival of Blind Pew being so affecting.

‘So things passed until, the day after the funeral, and about three o'clock of a bitter, foggy, frosty afternoon, I was standing at the door for a moment, full of sad thoughts about my father, when I saw someone drawing slowly near along the road. He was plainly blind, for he tapped before him with a stick and wore a great green shade over his eyes and nose; and he was hunched, as if with age or weakness, and wore a huge old tattered sea-cloak with a hood that made him appear positively deformed.’

When Jim Hawkins goes on to recall ‘I never saw in my life a more dreadful-looking figure’ we’re right there with him; the understated grief, the sea-fog shrouding the village, the arrival of this strange man – all combines to create a mood of unease and portent.

Kate’s words on the importance of atmosphere struck a chord with me. I read in bed every night, and at intervals throughout the day I’ll think of the book and it’s always the atmosphere of the novel that rises first in my consciousness; a sense of the world I’ll be stepping back into. If the atmosphere doesn’t call to me then there’s a very good chance that I won’t be hooked on the story either – it will feel two dimensional. Years on, plot details or character names might be lost to time, but I’ll always remember the mood of a book. Maya Angelou said ‘People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel’ – and it’s true of novels too.

It’s much through atmosphere that we become immersed in stories, enjoying a sensory experience that goes beyond language. A novel feels atmospheric when the setting and the narrative are deeply involved with one another; when characters and plot are physically embedded in their surroundings, and a near-tangible mood lifts from the pages and wraps itself around the reader.

Take Wuthering Heights, a novel I read and loved as a teenager. For me – I’d guess for anyone – it’s impossible to think of that book without bringing to mind the wild, bleak moors, and the irrepressible forces of nature – both external and internal. Imagine transposing the events of Brontë’s novel to a different location altogether; how altered the tone would be, if Heathcliff and Cathy roamed urban streets together, their drama playing out by railway sidings and in back alleys. Would Heathcliff be half the romantic hero that he’s held up to be (discuss), without the backdrop of harsh beauty?

Or Joanne Harris’ Chocolat - a book I devoured, transported to a world of ancient cobbled streets, sweet smells, and temptations. I can’t picture Vianne Rocher in any other setting except the one that Harris so expertly gave us. Writing this now, I can practically smell burnt sugar, taste cocoa, feel the wind whipping through the alleyways of Lansquenet.

Knowing what we respond to as readers is instructive when it comes to our own writing. Consider the opening of the second chapter of Tim Winton’s Breath. Instead of writing - I grew up in a house that was a long way from the sea but sometimes you could still hear the waves at night - we’re treated to this:

‘I grew up in a weatherboard house in a mill town and like everyone else there I learnt to swim in the river. The sea was miles away but during big autumn swells a salty vapour drifted up the valley at the height of the treetops, and at night I lay awake as distant waves pummelled the shore. The earth beneath us seemed to hum. I used to get out of bed and lie on the karri floorboards and feel the rumble in my skull. There was a soothing monotony in the sound. It sang in every joist of the house, in my very bones, and during winter storms it began to sound more like artillery than mere water.’

In these few lines, we get the extremes of the natural world, the power of water, and Bruce Pike’s visceral connection to it: his desire to not just inhabit the experience but have it inhabit him (‘the rumble in my skull’). This speaks to the heart of 'Breath'. Winton’s artistry means we get to lie on the karri floorboards (karri is a eucalyptus tree native to southwestern Australia) alongside ‘Pikelet’, and we’re as immersed in the song and thrash of this moment as he is. Note the efficiency of the prose: not one word wasted. Winton is a writer who is lyrical but controlled.

Atmosphere is about conveying mood through well-chosen details. We see Pikelet as someone who’s drawn to water that ‘pummels’, that sounds like ‘artillery’, whose sounds gets inside his skull and his bones. It’s an act of foreshadowing too; at this early stage we understand that he’s not going to be content to admire waves from a distance.

In Helen Walsh’s The Lemon Grove, we’re transported to summer in Mallorca, where a British woman on holiday with her family finds herself taking liberties she’d never permit herself at home – an illicit attraction towards her teenage stepdaughter’s boyfriend.

‘Nothing moves. The darkness deepens. Jen shivers, intoxicated by the magic of the hour. The road is no longer visible. The first stars stud the sky. A wind rises, and, borne on it, familiar sounds of industry from the restaurants in the village above, the clang of cutlery being laid out, ready for another busy evening. She rubs her belly where it is starting to gnaw. It’s a good kind of hunger, she thinks, the kind she seldom experiences back home; a keen hunger that comes from swimming in the sea and walking under the sun.’

A few lines later, Jen sparks up a cigarette she finds in a kitchen drawer. ‘The kick of it,’ Walsh writes, ‘dirty and bitter, fired her up, made her light-headed.’

Walsh uses simple short sentences to good effect. We’re not distracted by reams of prose – we’re simply there with Jen experiencing what she experiences. Just like Winton, Walsh foreshadows. Jen is different, here in this place; she’s hungry, and she’s not afraid to find appeal in the ‘dirty’. As the story unfolds we feel the heat of the place, the portentous ‘she can sense the rain before it falls’, and the ensuing family disaster. The narrative, the setting, and the weather work together to create a taut, sultry experience for the reader plunged into the intricacies of desire and tension. I’ve only read The Lemon Grove once, but I remember the feeling of rising heat and a storm about to break.

While as a reader I love to be immersed in the atmosphere of a story, as a writer I know the graft that goes into generating that effect. For we’re not just building the blocks of a narrative, we’re tasked with creating something that’s less tangible. Something that, if we get it right, our readers won’t forget.

When I’m writing, I use music to connect me to the atmosphere I want to create. Just as a lover might dim the lights and slip on a record, I light a scented candle and go to iTunes to try and move things in the right direction. For The Sea Between Us it was the album An Awesome Wave by Alt-J which conjured vast landscapes and the swell of the sea. For my current work-in-progress I’m listening to a lot of Mazzy Star; the vibe is languid but there’s an unsettling undercurrent that makes me want to look over my shoulder. That sense of unease is just right.

The feeling we want to create is often right at the heart of the idea for the story, but it takes a consciousness on the part of the writer to draw it out and craft it into something distinctive and memorable. Ask yourself, what’s the atmosphere you want for your story? Once it starts to come alive in your work you’ll feel it for yourself – just as your readers will feel it – and your writing sessions will become all the more transporting.

Happy writing,

Emylia

Enjoy mentoring with our tutor, author Emylia Hall, when you sign up for one of our Book in a Year plans or the Ninety Day Novel course.

The music in the header video is from Milk and Honey by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Press play to sample some atmosphere.

August 1, 2020

Members' Stories.

Two of our writers describe their recent adventures in fiction with The Novelry. With thanks to Justine Gilbert and Sir Dexter Hutt.

From the Desk of Justine Gilbert.

UNLEARNING

The art of reversing everything you were taught in school about writing.

I was a teacher for 25 years. For the majority of my career, I was 'Head of English'. I knew my job, and the children in my care did well in exams. I taught KS2 English, GCSE English and I tutored A level English. I was also a dyslexia specialist. If you brought me a child that was underperforming, I could diagnose what was needed to help them improve.

I wrote short stories, poems, and children’s plays, some of which were performed. I read avidly - particularly children’s fiction and I advised pupils on suitable books to read. My writing lessons followed the National Curriculum. I taught many genres of writing: letters, journalism, speech writing, essay writing. My story writing unit went something like this: I drew a shape on the whiteboard which resembled the Matterhorn. I explained Beginning, Middle. End. Followed by: Set the Scene, Develop a Problem. Solve it. I avoided the word ‘climax’. (You had to watch for the double entendres that could destroy a class’s attention.) Sometimes I drew a line in the middle of the mountain, so that the picture resembled a capital A. This was the Sub-plot.

Next, came the opening paragraph. Setting. Use the five senses - sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell. The second paragraph. Character. Hair, eyes, build, mannerisms. Do you remember these lessons at school?

Then - Use of Language. In addition to Sentence Structure and Punctuation - shortened to SSP - we went methodically through: Adverbs, Adverbial Clauses, Adjectives, Adjectival clauses, Alliteration, Simile, Metaphor, Repetition, Rhyme & Rhythm, Proverbs & Common Clichés, Caesura. There are at least ten more points, but you get the gist. After that came story structure: Theme, Motifs, Historical Background, Flashbacks...

I like to think my lessons were entertaining, but the reason I mention those topics was that all of them counted in the Marking Scheme. If you wanted a child or teenager to get an A++, all those factors had to be evidenced on the page. Looking at the list I wonder how Hemingway might have scored. Yet I taught children to make a mnemonic so that they would write using as many of these literacy devices as they could squeeze in. It went something like: MARACAS … They had to tick off each letter as they used them to get the required grade. Creativity was unnecessary. Originality - not needed as long as you didn’t plagiarise. And it worked.

A decade ago, I signed on to become a SATs marker. Two things worried me. One was that not a single teacher in the room gained full marks on the Reading Comprehension. The KS2 SATs valued the ability to infer from text and apparently none of the experts could infer with 100% accuracy. No surprise that the children fared little better in the actual exam. But my second qualm occurred when I was marking the writing. There were always three writing options for Free Writing. That year, one of them was: 'Write about something new that happened in Year 6'. In one school, every child in the class wrote about their new teacher. In their differing accounts, one thing was clear: she had had a profound effect. Many of the pupils wrote eloquently and received their due marks. But one boy’s writing was far below standard for his year group. He wrote something like this:

I was a norty boy untill Miss came. Now wen I am norty, she comes over to me and says Jon you have to try harder. And I give her a cheesy grin and I put my thum up and I say Yes Miss and she smiles at me. And I will try harder and I will be beter becos I now my teacher likes me.

He didn’t get top marks, but he brought a tear to my eye with the simplicity of his writing. I wanted to give his teacher - and him - a hug. But there were no marks possible to reward such purity. I wrote to the TES to question whether our exams were fit for purpose and they published it as a full article, but nothing changed.

Do you know why so many schools teach ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Of Mice and Men’ at GCSE? Because they are short. You can get a teenager an A to C grade without them ever having read the whole text. I understood what drove the curriculum and I worked within the government paradigms. I also saw its limitations.

Then in 2011, I wrote my first book. It was a blast. I loved every minute of concocting the story and I put it up as an e-book. Friends liked it, but I was under no illusion that it was well written. Oddly, I can now see it was reasonably constructed because I had modelled it tightly on an existing book. Success by accident. A few years later, I met a retired police officer, who told me hair raising stories about his work. I felt compelled to fictionalise his exploits in a novel. He was racist and corrupt and it was a tale that should have resounded with modern audiences. In other words, it was a red hot story, but in contrast, my prose was a deflated souffle. I did like my clichés and metaphors. I had a huge prologue with backstory, irrelevant to the main tale. I knew how to set scenes and draw characters but not where to position them. I’d never heard of a premise. What was that? So I wrote an exposé of corruption with a meandering tale. I had dialogue that varied from said to chuckled with adverbs galore. He hissed 'menacingly' and shouted 'loudly'. Well, it’s what I taught, wasn’t it?

I knew that my style was awry. I read a great deal and I had always told my pupils to read widely. You will write as you read, I told them. And The Novelry says much the same. But I ignored this when I wrote. I wrote as I had taught.

I have great ideas, I told myself, but I write like a teenager. What am I doing wrong? And then while searching for a course on creative writing, I came upon The Novelry. Here, I learnt to examine texts differently. I plotted books in a new fashion. I had never heard of the Five F’s of The Novelry, but it did not take me long to recognise the soundness of the structure. Modern audiences have little patience and that includes me. I want to be plunged into the story. I want to be shown the dilemma. In my writing to date, I had made frequent wrong turnings.

Schooling is whipped into shape by politicians. Popular writers complain about this. I worked hard at teaching, but now I am a writer and it demands the same attention. I have to unlearn everything I learnt and taught, and re-learn what is needed. The Novelry has introduced me to the new leaner, clearer prose for the modern market place. My head is down, nose to the screen. I am being taught. I write. I can learn from my mistakes. So I’m learning.

From the Desk of Sir Dexter Hutt.

OFF TO THE RACES.

Watching the two-year-old racehorses taking part in their first race at Goodwood this week caused me to reflect on my journey to become a writer. They had all been on the practice gallops, were all now poised and ready to discover their potential. But some of them were very reluctant to enter the starting stalls. The stall handlers coaxed, cajoled, blindfolded, turned them around, pushed hard. And still, some wouldn’t go in – indeed one or two were in the end withdrawn and did not come under starters' orders.

What has this got to do with my journey to be a writer? Well, I too have had many years on the literary practice gallops in my quest to become a writer. I purchased almost every book on ‘how to write’ – and made detailed notes. I read a wide range of fiction, I travelled to London to attend Guardian masterclasses, and I researched various topics linked with ideas for my novel. I had my study refurbished with an expensive chair to protect my back, and I bought a new computer. I was ready to go! And then frustration reigned. I just could not master the discipline of sitting down and actually starting to write a book. I would not, could not, enter the literary starting stalls.

Then Covid-19 happened. Golf, concerts, plays, and films no longer provided enjoyable but also convenient distractions to ease my conscience. And taking a long, hard look in the mirror, I knew it was now or never. Two glasses of red wine later, I had joined The Novelry, signing up for The Ninety Day Novel course.

I was not rushed into the starting stalls. The first phase of the course did what it promised – I really did have a week of motivation and inspiration. I was excited! On my first writing day, Tuesday 31st March, I had the obligatory cup of coffee and then trotted into my stall without a whinny or a whimper. I sat and wrote for an hour, totally focused until the oven timer – my study runs off our kitchen – signalled that the hour was up. I was relatively slow out of the stalls – three hundred words on my first day – but gradually built up speed to a more acceptable five hundred words daily.

And every day a lesson to inform, inspire, and motivate. I could not believe the treasure trove that I had stumbled upon. My fear was that I could work out a plot but not develop a character. So I changed my approach to the one of driving a car along a country road in the dark, the headlights allowing you to see so far at a time, but always moving you on to see farther. My characters began to develop a life of their own, and the headlights revealed the plot bit by bit. When I faltered in my literary race, my jockey, Louise Dean, provided words of encouragement that motivated and inspired: Isabel Allende’s “Show up, show up, show up, and after a while, the muse shows up, too,” I printed it off and pinned it to the wall of my study. I have found it to be true. Hemingway’s advice about the need to know the iceberg even if you are writing only about the tip has led me – as lockdown has relaxed – to visit two crematoriums that figure briefly in scenes from my story. I picked up speed as I ran my race, it was natural rather than forced; the timer found itself being set two or three times, and the word count became a regular 1000 words.

And I had a lucky escape. My initial idea had been stimulated by the subject matter of a major criminal case in the Midlands; I felt a reading of the case was essential research for my story to have verisimilitude. The response to my application for a transcription of the case was bureaucratic and slow; I was unsure whether to carry on writing or wait until I had read the details of the case. Louise strongly advised that I carry on, cautioning me that too detailed research can become a creative straightjacket. So I ran on with my story, and as the headlights showed me the way, and the imagination flowed, the relevance of the missing court case became fainter and fainter. Which was just as well, as when after almost three months the quote for the transcription arrived it was over £18,000. (Yes, that’s what I thought!)

I finished my first literary race last Thursday 24th July. I have written just over ninety-thousand words in under four months – having previously failed to write a thousand in four years. I know that the job is not yet done. I am mindful of Hemingway’s “The hard part of a novel is to finish it.” I will now go off to literary pastures and graze for the next month. And then I will trot excitedly into the starting stalls for my next race – The Big Edit. Bring it on!

And what do I think of Louise Dean and The Novelry? Sliced bread doesn’t even come close.

July 25, 2020

Clean, Good Writing.

It is a fine thing, growing older, as a writer. One has experience to draw upon, of people and all their animal behaviour, but also where to draw the line. Where to end the sentence. Enough said. Maybe we speak to each other in shorthand as we get older. There is the unspoken ellipsis that follows a word or a phrase, which draws on a hinterland of colourful experience. The Marquee Tent.... And so many moments come to mind for both the user of the word and the recipient. One develops a reticence to say more. Or maybe much.

Writers develop over time. No bad thing maybe that you weren't published at nineteen. I was struck this week by the changes in the work of the author Norman Mailer (1923-2007). Over time, he wrote leaner and cleaner. (I see a similar thing in Orwell's work, the same with Graham Greene. Happy the young writer who cracks it early.)

In Normal Mailer's novel, Barbary Shore (1951) one is struck by the coddy language. It's so over-written I could take my editing pen to it and whittle it down by half. The dialogue between two characters is a vehicle for Mailer to expound upon various less interesting philosophical themes and swagger intellectually. (He is wrong to do so. Since the readers he's likely addressing know this stuff.)

He had the kind of mind which could not bear any question taking longer than ten seconds to answer. “There are the haves and the have-nots,” Willie would declare; “there are the progressive countries and the reactionary countries. In half the globe the people own the means of production, and in the other half the fascists have control.”

I would offer a mild objection. “It’s just as easy to say that in every country the majority have very little. Such a division is probably the basis of society.”

(..)

To elaborate at such length upon Willie is not completely necessary...

Insert reader's groan. Thanks, Norm. We've had a few pages of Willie and his second-rate opining now. But Mailer dissimulates (bad Norman!) and continues with Willie's views on politics regardless. 'He massaged his chin, fully embarked upon a lecture. "Conditions are brutal in this country—slums, juvenile delinquency. I mean when you add it up there’s an indictment, and that’s just counting the physical part of it." etc. We are half way through the second chapter when Mailer releases us from this foil for his rhetoric with the words:

Witness my surprise—for I had become convinced that he would finally end by awarding his room to some other acquaintance—when Willie came to the dormitory one morning, and told me he was leaving for the country.

Witness my surprise? I think not, kind sir, you have delighted us long enough!

It was only the fact that Joan Didion described 'The Executioner's Song' (1979) as an 'astonishing novel' which gave me the confidence to sample another of his works.

Wow. Twenty-eight years and light years ahead. This is a fine Pulitzer Prize winner, not one whit heavy-handed or didactic but completely without pretence.

Based upon a true story, it's concerned with the events leading up to the execution of Gary Gilmore for murder by the state of Utah. Gripping and page-turning. We are plunged into the accident waiting to happen when Gilmore is released from a 12-year sentence, a man in his thirties, wolfish and over-keen. He is impatient for life. And there's the irony. His explosive neediness is a time bomb ticking on every page. The prose is under-written to allow the tension of the nervy dialogue between those in his circle, likely to be affected, to ring true.

Brenda knew she was making Gary nervous as hell. She kept staring at him constantly, but she couldn’t get enough of his face. There were so many corners in it.

“God,” she kept saying, “it’s good to have you here.”

“It’s good to get back.”

“Wait till you get to know this country,” she said.

She was dying to tell him about the kind of fun they could have on Utah Lake, and the camper trips they would take in the canyons. The desert was just as gray and brown and grim as desert anywhere, but the mountains went up to twelve thousand feet, and the canyons were green with beautiful forests and super drinking parties with friends. They could teach him how to hunt with bow and arrow, she was about ready to tell him, when all of a sudden she got a good look at Gary in the light. Speak of all the staring she had done, it was as if she hadn’t studied him at all yet. Now she felt a strong sense of woe. He was marked up much more than she had expected.

Mailer, Norman. The Executioner's Song

Notice how much less conspicuously 'clever' this is? Being clever is not the same thing as having wit. The education level attained by your reader, writers, is no concern of yours.

Mailer maintains the same plain language and if he is lyrical, it's visually helpful at the same time as poignant, in other words the expression serves to economize. (Note: the corners in the smile). This low-key, no-fuss prose, allows him to maintain pace, change narrative perspective, and honour the truth.

I mention this so you too can make your life easier sooner rather than later. As Hemingway said, it takes a lot of suffering to write a truly funny story. Well, maybe It takes a lot of experience to write simply. But you can fake it until you make it.

Our author tutor, Katie Khan, has some tips for you.

From the Desk of Katie Khan.

As I tackle a new draft of my latest novel, I’m confronted once again by my own unpolished prose sitting ugly on the page, trying too hard. It’s true that in many first drafts, the story and characters can feel thin and under-written; often, the problem with prose is the exact opposite. It’s over-written.

We have the privilege of seeing many writers’ work in progress at The Novelry and so I know many of you fall prey to the same urge. We think our way into the scene, growing our wordcount by describing every minute movement or emotion, until the page is littered with characters turning, looking up, looking down, walking to the door, turning back, lifting a hand in farewell, clutching their stomach… not to mention their hearts fluttering and pulses racing as they describe agonies of fear and pain…

Feelings and movements are the number one fingerprints of over-writing. I have a few suggestions about how and why to excise them from your writing, and some tips for how to put more sophisticated prose in its place.

When it comes to movement, less is more.

Imagine a scene set in a house. The scene follows Jeanette, who wakes up in the morning, brushes her teeth in the bathroom sink, and drinks a cup of tea leaning against the kitchen cabinet, before heading off to work. What we don’t need to show is Jeanette walking from the bedroom to the bathroom, then sauntering slowly down the stairs to the kitchen, bending down to put on her shoes and finding her umbrella in the hallway, before closing the front door, turning the key and trudging off down the path. (Phew! Did you feel the pace of that paragraph lag?) This is a character walking around a domestic setting we all know, doing a daily routine we all do, and we can absolutely gauge the flow without Jeanette having to do a million movements in-between. Cut from the bedroom to the bathroom, the kitchen to the office. I guarantee the reader will be able to follow. Even better, start the scene in the workplace, where I’m guessing the action really happens. (And if you really, really want to include these detailed movements, you’re likely writing a literary character study that relishes in the mundane minutiae of the everyday, and for it to be effective you absolutely must include dissonant details to give Jeanette’s dull, predictable movements some life.)

You can get away with very little movement in contemporary commercial fiction. Trust me.

Because the more we describe actions and movements on the page, the more the characters appear as marionette dolls. She looks up. She looks down. She gazes into space. She lifts the teacup to her mouth.

And the more the characters appear as marionette dolls, the more we draw attention to ourselves, The Author, pulling the strings behind the scenes. The artifice of the novel is exposed.

The novel is now a puppet show instead of a live, flickering reel of images created by us and projected directly into the reader’s brain. With our jauntily moving marionette dolls, we have failed.

Search for ‘walks’, ‘moves’, ‘turns’, ‘looks’, and any other variation thereof in your manuscript, then cut like the devil.

“The reason novels were so thick for so long was that people had so much time to kill. I do not furnish transportation for my characters; I do not move them from one room to another; I do not send them up the stairs; they do not get dressed in the mornings; they do not put the ignition key in the lock, and turn on the engine, and let it warm up and look at all the gauges, and put the car in reverse, and back out, and drive to the filling station, and ask the guy about the weather.” Kurt Vonnegut.

When it comes to feelings, less is definitely more.

Almost every early draft of almost every writer’s novel has a whining hero or heroine who feels bad. Who freezes. Who is in pain. Who quivers and shivers or hugs themselves, distraught. But if they start the story complaining, how will they handle the trial we’re looking forward to in the story? And can we bear to spend 300 pages in their company if they’re whining at the outset?

Last year I sent Louise, to my shame, a scene in which a character who is afraid of the dark steps out into the night for the first time. She was trembling. (Not Louise! Though I expect Louise was, too.) She exhaled at least a few times, turned dizzy, clutched something (a lamppost, perhaps? And did she inhale, or did she ‘catch her breath’? I bet you can guess the answer). Her heart was tap-dancing against her ribcage. (I can only apologise.)

Oh, the shame. That scene, rightly, is now covered in potato peel and coffee grounds in the dustbin of fiction.

Just like our marionette dolls jerking their articulated limbs around the stage, over-emoting in the prose only makes the emotion shallower. Once again, The Author is exposed, telling the reader what to feel from the outside. The irony is that if you understate an emotion, the reader often fills it in with their own imagination and experience. They are walking, metaphorically speaking, in that characters’ shoes. They feel what the character feels from the inside out.

To be human is to know grief. To know fear. To love and to hate, feel heartbreak and loss, loneliness, or joy. You can understate all of these in fiction and yet the reader will feel them tenfold.

For me, a master of discreet emotion is American writer Siri Hustvedt. Take this heartrending depiction of a marriage on the brink from her 2003 novel, What I Loved:

Under our love making I felt a bleakness that couldn’t be dispelled. The sadness was in both of us, and I think we pitied ourselves that night, as if we were other people looking down on the couple who lay together on the bed.

That’s it. That’s all you get. No weeping, no clutching each other by the shoulder, no groaning or moping, and certainly no hearts feeling as though they might cleave in two. Later in the novel (no spoilers!), Hustvedt writes grief so beautifully understated it verges on minimalism – and is all the more impactful for it. It’s a masterclass.

Search your manuscript for the tell-tale sign of over-emoting: ‘feel’.

So you’ve cut the over-written movements and feelings. What next?

Of course, you still want to evoke emotion and propel your characters forward in the scene.

You could consider using pathetic fallacy or sympathetic background to evoke the mood of the protagonist: think of the weather in Wuthering Heights, from the blizzard overhead at the first appearance of Catherine’s ghost, to the rattling storm the night Heathcliff runs away. Even the word ‘Wuthering’ is an adjective describing ‘the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather’. Dogs, too, are an example of representative characterisation in Wuthering Heights; the traits of the dogs are symbolic of the emotional state of key characters throughout the novel.

Or you could utilise what T.S. Eliot called object correlative: “A set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.” It’s shorthand for creating the feeling without directly referencing the feeling. Set a miserable looking ornament down on poor Jeanette’s bedside table. Or, writ large, look at how Jacqueline Woodson piles up the landscape to evoke the narrator’s mental state without ever saying how she feels in Beneath a Meth Moon:

I sat up front with Daddy, stared at the flat land as we drove. Big sky that I couldn’t look up into without thinking about M’lady and Mama. Green land moving fast toward us, then passing us by. Farms and fields. Whole stretches with nothing at all.

Write a scene where a character describes the field outside their window having just committed a murder. It would be different, wouldn’t it, to a character flushed with the joy of first love, even though it’s the same field…

Perhaps your chapter now feels too short or too thin, the scene too quick?

If I’m over-writing movements and pontificating over expansive from-the-heart emotions, they’re often symbolic of the fact I haven’t quite got enough going on in the scene. It’s likely too linear; remember poor, dull Jeanette walking around her house, or my character stumbling through her fear of the dark at night. The scenes are one-note. They’re flat.

In the words of Kurt Vonnegut: “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” What does your character want at this moment in time?

I really like this tip by Fleabag creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who believes there should be at least three things going on in one scene at the same time. For example, the scene in which an overheated Fleabag tries to take off her jumper and accidentally flashes her bank manager, while applying for a business loan.

"I feel like the more you put on a person, the more real it feels, because otherwise it’s just a conversation about a bank loan. But then if she’s sweaty and she’s under-prepared, and she forgot to put a top on underneath but she needs to impress this guy… When there are three things going on at the same time, at minimum, I think you instantly have reality.”

Yes, lovely. I’ll take novelistic reality over a juddering puppet show any day. Now I’m off to cut words from my manuscript and sneak in some of these devices – I hope this was helpful, as we set off on another creative week at The Novelry.

Happy writing,

Katie

Join us at The Novelry and get wise eyes on your work from the outset when you choose one of our Book in a Year plans including The Novel Kickstarter and The Novel Development Plan. Or simply complete a first draft in 2020 with our Ninety Day Novel plan. There's still time!

July 18, 2020

Before and After: From First to Last Draft.

As I entered into the fourth draft of my current novel, set in Brooklyn where I lived happily for a few years at the turn of the century, I turned back to console myself that the redrafting process was ever the same, even in the glory days and checked my process for my first novel.

I decided to look at first draft vs. final draft to see 'what gives', and to examine some other authors' first and last drafts too.

Becoming Strangers by Louise Dean.

It was 19 years ago this month, July, that I set about writing my 'proper' first novel. I had two in the drawer and I meant business. I was heavily pregnant (due November) and had two boys under 5 at home in Brooklyn. I had a premise which started out as pretty hokey in February 2001 but by July I'd been turning it around in my mind for a few months.

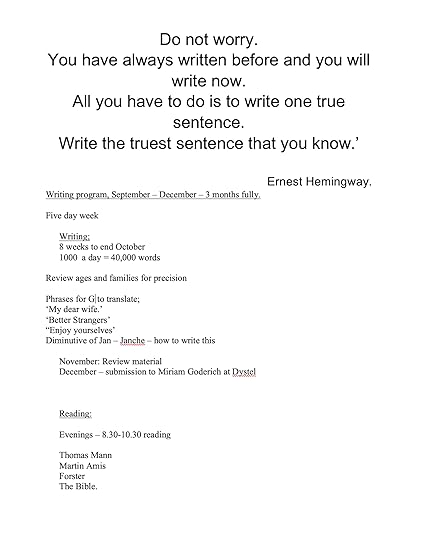

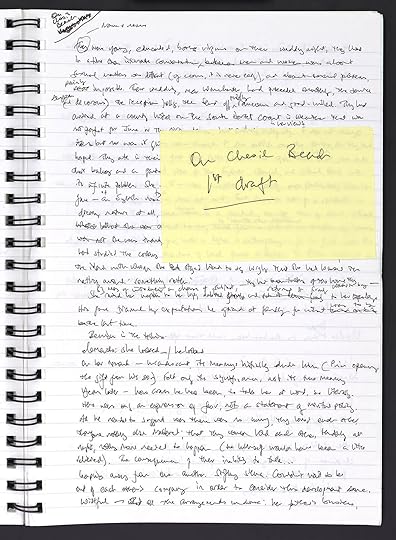

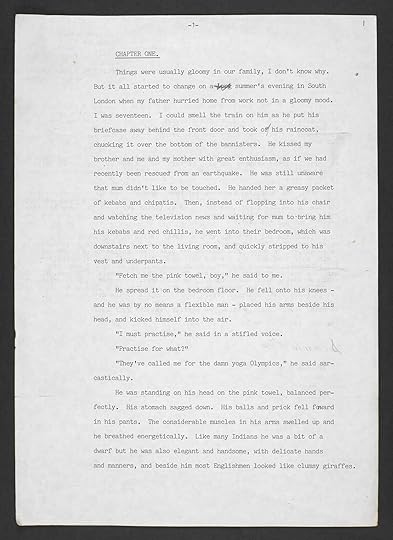

This was what I set down in July when I began:

The working title for what was to become 'Becoming Strangers' was 'The Last Resort'. I must have felt at some point the latter was a bit too on the nose. Jonathon Myerson, who reviewed the book for The Independent, hated the published title, but he and his wife Julie who reviewed it for The Guardian, loved the opening line. The line that became the opening sentence emerged through a process of 'cut and paste' - to find what the hell this book was about, and where to drop in hard and fast.

I set myself a routine and a process, which won't come as a surprise to writers of The Novelry. What has come as a big surprise to me, reviewing the evidence, as for some reason I had assumed all my re-drafts were contractions, is that I always intended to expand it. The novel ended up 70k+. Here I set out to write 40k. Funnily enough, this new fifth novel of mine came in at 48k at first draft and will be about 70k when I submit. The time frame for writing took into account the November due date. But as you'll see as the birth neared, I got busier.

I can't recall reading Amis at all, though I enjoyed his memoir, and I think I may have added that to try to bring some modern 'grit' to the storytelling. I extended the reading list to Graham Greene's 'The Heart of the Matter' and relied on that book heavily later, comparing page by page, noting how and where and why I fell short. I love the heavy cadence of the verses of The Bible and have read the New Testament a number of times with pleasure. Yes, I am a nerd. No, I am not a good Christian. I did pitch to Miriam Goderich, but I don't think I heard back or else it must have been one of what I'd come to dub 'my pretty rejections'. I pitched to agents in the UK in February 2002.

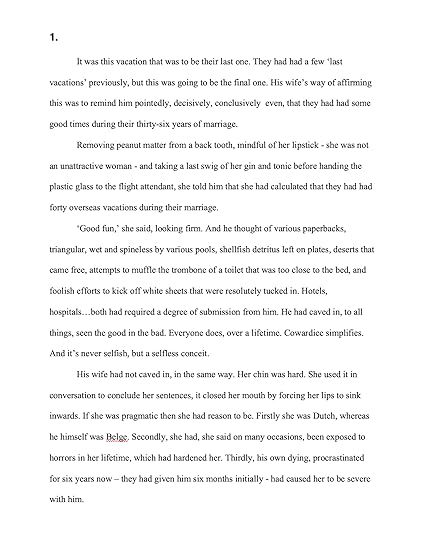

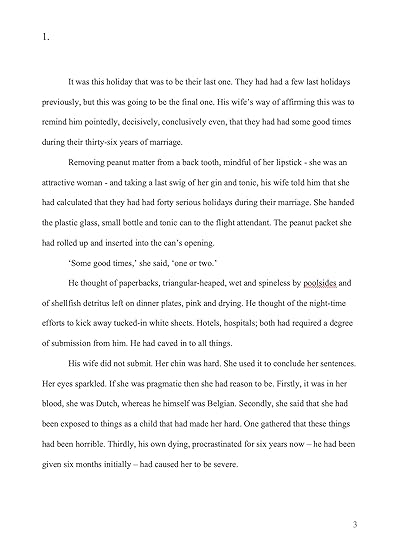

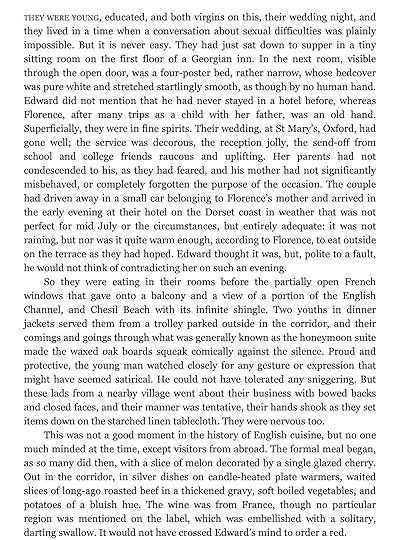

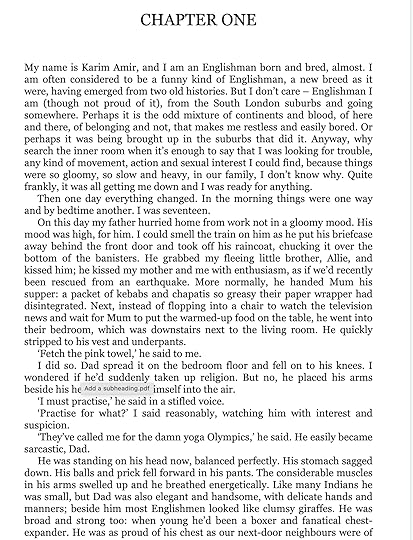

The opening page in July read like this (see left-hand side). The Twin Towers came down in September, visible from our home, and that was a time of great worry and distress both locally and of course internationally. By November I had completed the first draft and the opening page read like this (right-hand side) and was pretty much the same with the obvious change to British English wording:

I gave birth to my daughter at the end of November, and we had Christmas with the three kids, and I pressed on and completed the next draft to send to agents. Somewhere in between, I found the way into the book which had been lurking in another guise at the first draft down in Chapter 5:

When I moved that sentence (and surrounding material) to the opening, I felt confident I'd somehow pinned into position the theme or gambit of the novel, and I felt ready to submit, and did so in February 2002 as follows left-hand side. The published version of the book is here right-hand side:

You can see the original opening line has been pushed down.

In retrospect, the longest part of my process then was getting the idea right, the premise, which took me 5 months from February to July, a process we fast track with the Classic course at The Novelry. The writing of the first draft took 3 months, the revision 3 months. (My second historical novel took 9 months planning and 9 months writing, I believe. My mother claims I wrote 9 drafts.) It's interesting to look back and see how one almost physically manoeuvres sentences to locate the life or liveliness of the idea. All I can say is you know, with a sagging heart, when it's flat, and you know when it's got a spring in its step. When you get that bounce, you're good to go because the bounce gives you the energy to move on with the book in a sprightly fashion.

For your comfort and delectation, here are some 'Before and After' shots of first drafts and finished novels.

Hold Back the Stars by Katie Khan.

Our tutor, Katie, explains:

Because Hold Back the Stars opens on the inciting event - an accident in space, sending Carys and Max tumbling away from each other, their air ticking down to zero - the opening always received the least amount of edits and amends; it was the 'proof of concept', I suppose. It had to be right there on the page from the start, because without it, there was no story, and nobody would have read on. I recall in some of the later edits with the publisher (Penguin Random House), my editor said the opening line was hard to visualise without any context (foots, knees, tumbling...), so it shuffled down the scene. The whole thing reads much sharper, much faster. I always had a thing for 'two pointillist specks on an infinitely dark canvas', and if I'd been braver I might have kept that as the opening line. Looking at the published version now, I'd probably remove the speech marks from around the first line ('This is the end.') and given its boldness to the narrative voice instead - ah, hindsight. What a thing for writers to wrangle with: our own evolving taste!

Though this was my first draft, I did attempt to write it in a couple of different styles at the outset; I always play around with different executions, trying passages in first-person versus third-person, past tense versus present, limited perspective versus omniscient. When it has a flow that I like - here, it needed to feel 'immediate' and sudden - I carry on and write the whole novel in that style. There is an early version of this chapter on my hard drive, written from the point-of-view of the A.I. character, Osric, who is observing Max and Carys falling in space and narrating it for viewers at home. It has a really boomy Douglas Adams-style voice, and will never see the light of day!

Here's the first draft (left) alongside the published version:

The Thousand Lights Hotel by Emylia Hall.

Our tutor, Emylia, explains:

The first paragraph of the first draft of The Thousand Lights Hotel starts with the description of a photograph. There were a number of these italicised sections running throughout the book, the idea being that they’d form a way into the main character’s memories. My agent, who was reading the manuscript before my editor on this occasion, said that she didn’t think they added anything and I had to agree that they were a largely decorative addition. With each book, I’ve become better at ‘killing my darlings’. I was also conscious that I’d employed a similar device in my first novel, so even to me, it felt a little tired. After making the cut, I simply turned what was Chapter 2 into Chapter 1. And, as you’ll see below, that opening to Chapter 1 doesn’t end up being dramatically different in the final draft. It’s tighter, there’s a tense change, and I’ve taken out extraneous detail. For instance the idea of Kit running with her eyes closed – an image I liked, and one I enjoyed writing – is now distilled to the line ‘it was possible to believe in the safety of infinity’; I realised that any more than that would have been unnecessary and distracting at this point in the novel.

I always had a clear idea of how The Thousand Lights Hotel would begin, however reading it again now I’m not sure about the line ‘The question charged along with her’ - three years on, that feels a little heavy-handed to me!

Here's the first draft (left) alongside the revised submitted version (right):

Published version:

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan.

1984 by George Orwell.

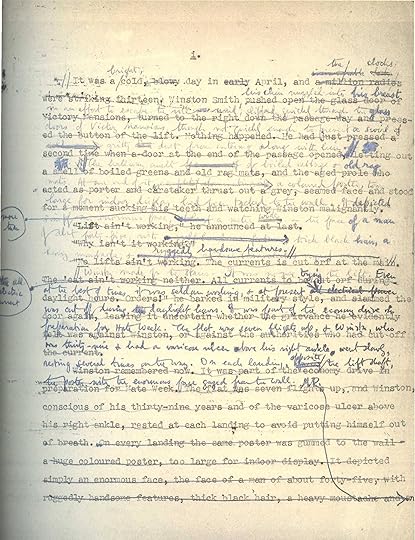

1984: draft version

It was a cold day in early April, and a million radios were striking thirteen. Winston Smith pushed open the glass door of Victory Mansions, turned to the right down the passage-way and pressed the button of the lift. Nothing happened. He had just pressed a second time when a door at the end of the passage opened, letting out a smell of boiled greens and old rag mats, and the aged prole who acted as porter and caretaker thrust out a grey, seamed face and stood for a moment sucking his teeth and watching Winston malignantly.

“Lift ain’t working,” he announced at last.

“Why isn’t it working?”

“No lifts ain’t working. The currents is out at the main. The ‘eat ain’t workin’ neither. All currents to be cut orf during daylight hours. Orders!” he barked in military style, and slammed the door again, leaving it uncertain wheter the greivance he evidently felt was against Winston, or against the authorities who had cut off the current.

Winston remembered now. It was part of the economy drive in preparation for Hate Week. The flat was seven flights up, and Winston, conscious of his thirty-nine years and of he varicose ulcer above his right ankle, rested at each landing to avoid putting himself out of breath. On every landing the same poster was gummed to the wall – a huge coloured poster, too large for indoor display. It depicted simply and enormous face, the face of a man of about forty-five, with ruggedly handsome features, thick black hair, a heavy moustache and an expression at once benevolent and menacing. It was one of those pictures which are so contrived that the eyes follow you about when you move. BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU, the caption ran.

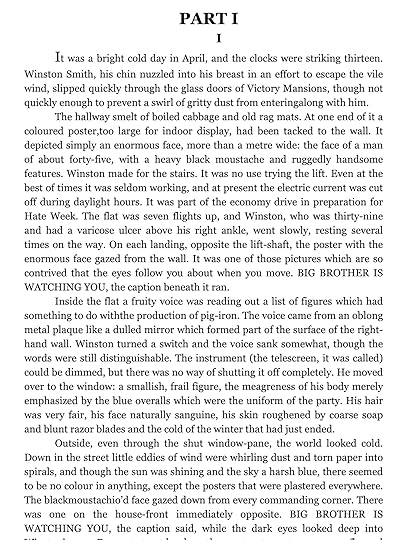

1984: published version

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. Winston Smith, his chin nuzzled into his breast in an effort to escape the vile wind, slipped quickly through the glass doors of Victory Mansions, though not quickly enough to prevent a swirl of gritty dust from entering along with him.

The hallway smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats. At one end of it a coloured poster, too large for indoor display, had been tacked to the wall. It depicted simply an enormous face, more than a metre wide: the face of a man of about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and ruggedly handsome features. Winston made for the stairs. It was no use trying the lift. Even at the best of times it was seldom working, and at present the electric current was cut off during daylight hours. It was part of the economy drive in preparation for Hate Week. the flat was seven flights up, and Winston, who was thirty-nine and had a varicose ulcer above his right ankle, went slowly, resting several times on the way. On each landing, the poster with the enormous face gazed from the wall. It was one of those pictures which are so contrived that the eyes follow you about when you move. BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU, the caption beneath it ran.

The first line: 'a million radios' becomes simply 'the clocks'.

The slightly hammy exposition and info dump of 'Oh, yes, I remember…' of the power cuts and Hate Week is dropped in favour of another dull, frustrating fact in another dull, frustrating day. Orwell rules in favour of understatement.

Then there’s the porter, neatly excised from the final version, leaving Winston Smith alone with the images of Big Brother.

The Budha of Suburbia by Hanif Kureishi.

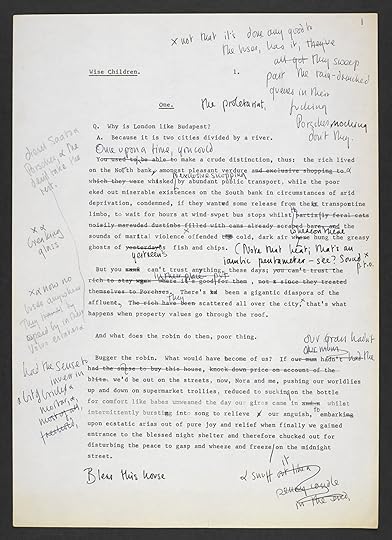

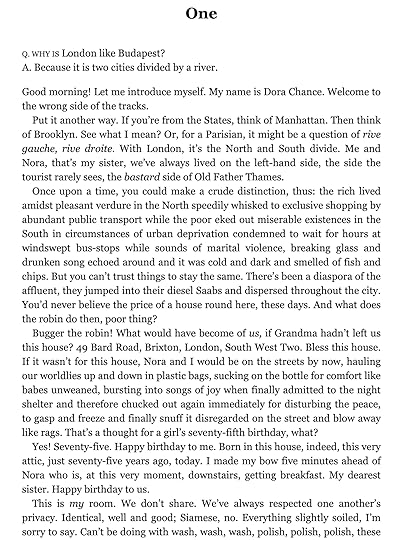

Wise Children by Angela Carter.

These are my core precepts:

1. Get the idea right and tight. Spend time turning it to the light. Invest a lot of time in the few sentences of the premise. Know the agony of the dilemma and twist it until it pops its pips. Look for the dramatic irony.

2. Write the first draft with glee, mischief, wit and on fire. Get on with it. Try to keep it lively and stay open to possibilities as you discover the story.

3. Revise and streamline the story in the next draft or drafts, head back to the premise. If it's changed, change the brief, and rework the material again, but when in doubt remind yourself what it was that got you excited in the first place. (Chances are if you spent aeons on the first draft whatever moved you originally may be missing.)

If that original insight or movement is still meaningful to you, carve hard and find the place or phrase that cuts to the heart of it. It might not be in your first chapter, it might be later on. In my current novel, as in my first, by coincidence, I located it after my third draft in chapter 5. I'd felt a little dissatisfied and asked myself in the wee hours one morning - which part of this story do you love most? So I went, got it, and raised it to the opening.

A bold move like that will cause upheaval upon upheaval, and you'll be grinning from ear to ear because you've set your standard higher. Whatever happens with that novel, it's the novel you wanted to set down.

I think I have to start with a bugle call that summons the story and the reader to the hilltop. I need that rallying call too; the reveille! When you return and meet the original premise, face to face, after months of work in all sorts of directions, you'll reunite as old friends, shake hands and find the joy of the thing again.

July 11, 2020

Meet Emylia Hall - Our New Tutor.

Emylia Hall, a bestselling author of four novels and a Richard and Judy Book Club favourite is joining The Novelry as a tutor. She's a wonderful teacher, a mother, a fellow of The Royal Literary Fund, and she's currently at work on a murder mystery. Read more about Emylia here. Our writers are invited to come and meet Emylia via Zoom on Thursday at 6pm BST.

From the Desk of Emylia Hall.

When I was 27 I left my job in a London advertising agency and went to work in the French Alps as a chalet chef. At the time I called it a career break, but it turned out to be the start of something much more. I’d wanted to shake off some responsibility and go snowboarding, but I also had the ambition to try to write a book. I had a few abandoned paragraphs on a floppy disk (this was 2005) but I’d got no further with it. Perhaps if I’d found the right inspiration or intervention, I might very well have applied myself to writing in London but, as it was, the move gave me the freedom and confidence to make a proper start. I was simultaneously finding my feet and stretching my wings.

I spent two winters playing in the snow – living in chalet staff digs, living on tips – my soul soaring amidst all that beauty. I was surrounded by people who, while not writers, had taken leaps to do the thing they love, and I was undoubtedly influenced by this spirit. Over the course of two seasons, and a freewheeling summer in between, I wrote the first draft of a novel. I sent it out to agents without delay – and with very little in the way of rewriting. (Looking back, I had a lot to learn). I received a hatful of knock-backs, but a couple of agents were encouraging enough in their response to keep me keeping on. Moving to Bristol that summer I became committed to my quest. I now understood that I had to believe heart and soul in the story I was telling if I was going to embrace the substantial work (hello rewriting!) that is all part of producing a novel. So, I decided to start on something new, something that was a closer reflection of the things that really mattered to me: a coming-of-age story inspired by childhood holidays in Hungary.

In 2008 I went on an Arvon course, with 40,000 words of what would eventually become The Book of Summers in my bag. This was when I met Louise Dean for the first time – I was lucky enough to have her as a tutor. That week of writing and learning intensified my commitment, and I came home aglow.