Louise Dean's Blog, page 13

January 9, 2021

The Nervous Novelist

'Every writer I know has trouble writing.'

Joseph Heller.

Almost 99% of writers exist in a state of some doubt that they're any good at this writing business. The other 1% aren't very good at it.

Only a fool thinks their writing is much good while they're mid-novel. Sure, you get flashes, moments, in which a line soars, an insight cuts, or a mysterious space opens up and you think - yup, that's why I do this. And even, damn that's good. But mostly one goes to the manuscript word document in a state best described as faintly appalled.

You're not alone. Confidence is quite properly an elusive quality for this craft. You'd be useless with too much of it. Confidence and doubt keep the work human and humane, and above all else tender. After all, the novel is the art form singularly concerned with the frailty of the creature that knows God but is no god, that has the appetite of an animal, but is not quite as reliable.

We seem to see our novel as the antagonist, there to be the unfair fairy-tale mirror which when we approach it with our tremulous question has a stern riposte. Who is the fairest of them all? Not you, sucker.

But the novel we are writing is not a Frankenstein, grown beyond our control, and we should see it not as a monster but a charmer. It's ours. We can make it lovely and loving. We should see it less as a sardonic schoolmaster and more as dance partner.

Here are some quick fixes to find yourself in its warm embrace.

1. Questions.

"The stupidity of people comes from having an answer for everything. The wisdom of the novel comes from having a question for everything....The novelist teaches the reader to comprehend the world as a question. There is wisdom and tolerance in that attitude." Milan Kundera.

Ask questions. Insert questions into your chapters and scenes. Think of you, the author, dancing backwards in high heels with your reader. Invite the reader in with questions. This is a canny way of upping the ante on your plot. Can she be sure of him, she wonders. For example. But, is this the right way home?

Bring your doubts to your novel and ask the reader to share the journey. Include questions from your very chapter, and use them to signpost or breadcrumb the route through the novel. At first draft, you're asking yourself these questions too. From second draft on, they're there to keep the reader turning the pages.

Some of you will have enjoyed The Black Narcissus adaptation by the BBC of Rumer Godden's novel. The character's flaw is fixed fast. (When scoping out your story, for those of you who are averse to plotting, consider this - a main character unsuited to the circumstances in which they find themselves.)

A nun, who is proud, is tested in mystifying circumstances which ask her (and the reader) to reconsider her understanding of religion and spirituality. This is the theme.

The inciting incident - the move of the group of nuns to establish a mission at Mopu is highlighted by the question raised at outset in the first chapter:

‘But I should like to know,’ said Sister Ruth, ‘why the Brothers went away so soon.’

Now, don't be afraid to ask it more than once...

She did not want to answer that question and now Sister Ruth had asked: ‘Why did the Brothers leave so soon?’

And don't be afraid to let the reader know that neither you the author nor the main character as yet have the answer. The first chapter ends humbly thus:

'Sister Philippa’s voice seemed to ring on the air, and the clatter of the ponies’ hooves and the creaking of their saddles. They felt curiously abashed and silently followed one another down the path.'

You see, in a tender honest relationship, one can be oneself and be vulnerable. This could be your relationship with your novel. You don't have to be confident and ball-busting in this charming space. You can - and perhaps you should - be exposed. Rumer Godden's chosen setting of the exposed Himalayan mountainside is perfect for her theme.

2. Confessions

You can admit your doubts and uncertainties as to how to tell the story and create an immersive mutual enterprise between you and the reader. This works particularly well if you're using an authorial voice either in first person or third and creates complicity.

Kurt Vonnegut does this to great effect in Slaughterhouse-Five when he admits it has taken him 30 years to work out how to tell this story. The upside of being 'open books' with your reader is trust, and you can take them into curious and surreal places if you're this candid with them. This is, perhaps, the 'reliable' narrator trope. I'm being honest with you that I'm a little lost here.

I would hate to tell you what this lousy little book cost me in money and anxiety and time. When I got home from the Second World War twenty-three years ago, I thought it would be easy for me to write about the destruction of Dresden, since all I would have to do would be to report what I had seen. And I thought, too, that it would be a masterpiece or at least make me a lot of money, since the subject was so big.

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse 5.

You can revel in your lack of confidence and use plenty of self-deprecation when you insert yourself as the story-teller in this way. We see the same approach in Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye.

I’m not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I’ll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy.

J. D. Salinger The Catcher in the Rye.

We see a similar abashed candour of approach with the storytelling of David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, "I was destined to be unlucky in life" and perhaps this is what made it, as Dickens attested, the favourite of his novels.

The best treatment you can apply for the condition of lack of confidence is humility. Confess it. Because you are taking the reader deep within yourself, and are at risk of assuming their close knowledge of your life and times, signposting is important. The unfolding of personal biography, dealt with summarily and humbly, is closely followed by Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse-5. Vonnegut takes pains to tell us where we are and flags and explains leaps of time and place. Dickens does the same. Don't be afraid to NOT be clever, and tell your reader where you are and they are in quite a plain and simple way.

Looking back, as I was saying, into the blank of my infancy, the first objects I can remember as standing out by themselves from a confusion of things, are my mother and Peggotty. What else do I remember? Let me see.

See how straightforward this is? More a ponderous conversation than any vaulting or leaping between metaphors or attempts at genius. Indeed, most best-loved writing is straightforward more than it is obscure.

When we confess and reveal ourselves through the guise of our characters, we find a safe place where both the reader - who like you lacks confidence - and the author is at home with someone who knows how they feel.

It would concern the reader little, perhaps, to know, how sorrowfully the pen is laid down at the close of a two-years' imaginative task; or how an Author feels as if he were dismissing some portion of himself into the shadowy world, when a crowd of the creatures of his brain are going from him for ever. Yet, I have nothing else to tell; unless, indeed, I were to confess (which might be of less moment still) that no one can ever believe this Narrative, in the reading, more than I have believed it in the writing.

Dickens is saying that in no other novel has he been so exposed or at home.

What I am saying to you is it's okay to be scared. You're not alone. It's why we read - and write. 'Only connect' as E.M Forster put it.

3. Injustice

It seems to me that the novels which affect us most profoundly have at the heart of the story an injustice visited upon a certain person representative of a segment of society. The classics which we visit on the classic course are the best-loved stories appealing to both adults and children and often the main character is being hard done by, through no fault of their own. This is a little more than a question of being the 'outsider', it's not a matter of choice but of being marginalised by a society which offers no place. The story makes a space in the universe for this person. And these stories say to us - when we reach the end of this story and make space for this person, the world gets a little better. Thus the reader and author embark on a charitable expedition to do the right thing and turning the pages, each opens their hearts and creates room there.

I would ask yourself as a writer - who is being hard done by in this story-world?

When you locate the object of your sympathy, you forge an alliance with the goodwill of the reader and make a joint enterprise based on your humanity.

You see, you are not alone in your self-doubts, but when you turn your focus and energies to somebody, a fictional person, in an unenviable situation either marginalised or abhorrent (more often in adult books) your own nervousness and sense of failure, that chill within, are swept away in a current of hope and warmth. By tending to others, you lose yourself and find what you're looking for. Love, and sympathy.

Lean in to your nerves. Any artist attempting to portray the human condition knows this is the source of our art. In your nerves and self-doubt, you will find us. All of us. Knees-knocking. Don't dodge your doubt, delve.

To boost your confidence during the writing of your novel we suggest the following little hacks at The Novelry;

small achievable word counts daily

stay in touch with your novel daily even on the days the words won't flow. Just pop in. Skipping a day makes the wobbles worse!

make contact and connect with other writers who share doubts about their writing too, and know you're not alone

confess the problems and write them down, you'll tackle them in time (there really isn't a problem that can't be fixed, I promise!)

don't share work at first draft. Give yourself time and space to develop your precious work in private before it sees the cold light of day

remember no one will see it until YOU the author are ready

don't strive to be wildly original, readers want familiarity more than they want originality - how about a new twist on an old tale?

Our Positive Teaching Method.

Before The Novelry, I had a couple of experiences of feedback which were similar - in that both saw what was wrong with my first draft, and only that. This left me - an experienced, published author who might have been more confident - panicked and defeated. I became consumed with doubt and paralysis set in. All they saw were problems; all I saw was a failing writer. The first time I experienced negative feedback, I abandoned the work. The second time I experienced it cost me six months of time and a further - ahem - few misguided drafts of a novel (like throwing darts blindfolded.

Any fool can see what's wrong with an author's first draft.

There's no merit in shaming the first draft, it's not helpful. It's stupid on the part of the giver. Wholly negative feedback on your novel at first draft is more about the giver than the work. A first draft is not a finished draft and offers many opportunities and story avenues - still open - to pursue.

I decided to put some of my work at later draft stage through The Big Edit feedback session with one of our tutors. The session went like this: that's good, that's good, I love that, and - do you need that to make the story work - or is it really about x, this story?

The positive tutoring set my mind buzzing with possibilities, thanks to an ally who could see beyond the trees. I left our session with an elegant streamlined concept, feeling excited, elated and - hell - actually liking myself.

All writers are sensitive. It can be a good thing, it can be a bad thing, but it's a thing. Naturally, we are susceptible to influence as part of that condition. I am likely to give a lot of weight and credence to what is said to me, particularly when it comes to the work. I am hungry to find my way. As Michael Ondaatje puts it - writers are always looking for the 'next step.' Just be very careful where you step.

At the heart of The Novelry is our positive teaching method. We offer a collaborative environment, not a competitive environment. We believe all of us, writers at all stages of their career, are always learning their craft. We work as comrades. No creative writing tutor should assume superiority, far better they expose their mistakes and help their fellows learn from where they've gone wrong than to dodge the difficult questions or issue divine diktats. We are all up to our necks in words in the early drafts of our novels, half-blind to the storyline. All stories are equal at this point. It takes a working writer to have the humility and sense to know that and to practise gentle, positive care.

We work with you as fellow craftspersons. We bring our experience to bear to guide you by showing you the tools (not rules) to achieve your vision. We want the best for you and your story. And you know what? The mutuality of the enterprise brings rewards to both parties. Our one-to-one sessions with our writers are lively and exciting. We love what we do. Good teachers learn while they're teaching. (Bad teachers assume a lofty position and leave you to clear up after their ego.)

If someone pours scorn on your early work, they're either not a writer writing, or it's them, not you. All early work has a little light burning, it needs life breathed into it, it needs to be coaxed into a story fire.

At The Novelry, we are writers writing. Above all else. All the tutors are writing novels and at work, too, just like you. We will never pooh-pooh your idea, we will help keep it warm and breathe life into it, cherishing the good in it. We will help you grow as a writer and build your skills and confidence so that you get stronger without losing the vulnerability that makes you unique and your work truthful and affecting.

Be who you are, maybe even more so, when you're writing fiction.

Happy writing,

Louise Dean, Founder.

January 2, 2021

A New Year's Resolution for Writers

From the Desk of Kate Riordan.

Someone once said to me, ‘It’s a shame, isn’t it, that being a writer was your dream but you don’t really like it’. I turned to him, completely taken aback. ‘But I love writing!’ I said. He laughed. ‘You’ve got a funny way of showing it.’

He had a point. I know quite a few writers but I’d never come across one more resistant to the actual writing than me. ‘Just do a little bit every day!’ well-meaning people would say, to which my answer was a bitter laugh. Every day? I’d gone weeks without even opening my work-in-progress. Obviously, the guilt was crippling.

I wasn’t unique in this, of course. A cursory trawl on Twitter revealed plenty of writers discussing their displacement activity of choice: manic decluttering, doing their tax early, watching videos of dogs launching themselves into piles of leaves. Anything, anything, not to just crack on and write the sodding book.

But while this is a common affliction, I had elevated avoidance to a terrible, toxic art form. The worst of it was that I actually did love writing, when I managed to coerce myself into starting. When the plates are spinning and the words are flowing, you can lose a whole afternoon to the muse. You look up and it’s grown dark outside and you’re dizzy with hunger because you’ve forgotten to eat. But those days were rare. In 2020 they became vanishingly few and far between, and while a global pandemic made being creative genuinely, biologically difficult (we need to feel safe to access that part of our brains, or so I read in a very long article while not writing my book), I had grown entirely fed-up with my own excuses. It’s wearing, fighting yourself every single day.

I’ve always got in the way of myself when it comes to work. ‘You’re your own worst enemy!’ my mum would exclaim in despair when I was at school and resisting my homework. When I think back to the fortnight of study leave we were granted for A-level revision, I mainly remember sunbathing in the garden with my headphones on, surrounded by folders of notes I couldn’t, wouldn’t, open. The exams themselves were great. I was forced to sit at a desk, in the quiet, and concentrate. Oh, the glorious relief of it. I recall those hours sitting in upper school hall with great affection: curtains drawn against the sun, the heady smell of just-mown grass, the soft tick of the clock. While my best friend sat in a cold sweat two rows away, I was happy as Larry.

Before I wrote novels I was a journalist and this suited me well. Most journalists are magpies. We have short attention spans and get bored quickly, beady eyes scanning for the next shiny story. We love finishing and work best under pressure. I still write the odd magazine piece, usually for book promotion reasons, and there’s great satisfaction in completing a task in a few hours. My mind clears and my focus sharpens. I get the thing done and happily cross it off my to-do list. I never have to think about it again.

Writing a novel is not like that. No one can write a 90,000 word novel at the last minute, buzzing off caffeine and adrenalin. It’s not just the sheer number of sentences that need to be wrangled on to the page with some semblance of fluency; there are the plot and subplots, the delicate interplay of characters, the variations in pace, the whole pretend world you’re trying to spark into life. You can’t blag that on the day, not even in the tranquil surrounds of upper school hall.

Happily, just as I was getting thoroughly hacked off with myself, I became a tutor at The Novelry. As part of my preparation for the role, I dived into the course material and discovered The Golden Hour: sixty minutes of writing on waking, when you’re still half in dreams, and not yet sucked into the minutiae of the day. I know I will never rise at 5.30 unless I’ve got a flight to catch or the house is on fire, but my whole ‘I’m an owl!’ schtick was convincing no one. I hadn’t written into the night for years.

Fired up by the notion of The Golden Hour, I began the usual bargaining with myself - my own, well-worn version of good cop/bad cop. It went something like:

Why don’t you get up early tomorrow, just to see?

But then the dogs will wake up and I’ll have to let them out and feed them and all that shit.

Just creep into the study and start.

I’ll be cold. The heating doesn’t come on till seven.

Ok, do it in bed then. Put your laptop next to the bed, wake up and just start typing.

I dunno, I probably won’t sleep well tonight and I’ll be too tired.

YOU DON’T KNOW THAT YET.

You see what I’ve been up against. The thing that eventually persuaded me to give it a whirl was the under-the-radar quality of it. If I could do an hour of work before I normally even woke, it would be like the most amazing sneaky freebie.

So I tried it. I woke in the dark, reached for my Mac and wrote 1,200 words by 8 am. When I skipped guilt-free down to breakfast, bad-cop me had only just come to. Like a Stealth bomber, I had flown fast and low over the ground, completing the mission before I even noticed.

Elated, I did it again the next day, and the next. Then it was the weekend and I rebelled and felt bad after. BUT I managed to get into the rhythm of it again on Monday. My word count on Scrivener crept up. I did more in two weeks than in the previous two months. Crucially, I didn’t try to do any more during the rest of the day. I felt like I ought to do at least one more hour in the afternoon but I followed the advice not to push it. And Louise was right (again). Not only was I writing regularly, but I was actually kind of looking forward to it. I was dipping into that other world just enough to keep the lights on, but not so much that it felt like a chore.

Neil Gaiman has compared writing a story to moving through fog and it is - and should be. But where before I was crawling along the M1 trying to find the fog lamps while HGVs loomed up on the inside lane, this new fog is something more enchanted and mysterious, a Narnian kind of mist that reminds me why I wanted to write stories in the first place.

New Year’s resolutions have always felt so dutiful: eat less, exercise more, work harder (work at all). This year’s - simply to continue on the path I’ve tentatively started down - is different.

It feels like nothing less than an indulgence to gift myself this magical, liminal hour between sleeping and rising: the house still silent, the dogs quiet, and me sitting up in bed with my laptop as the sky lightens, flying under the radar.

Happy writing in 2021!

More about The Golden Hour Method at The Novelry here.

Join us and start and complete a novel to publishing standard with our Book in a Year Plan here.

December 26, 2020

The Gift of a Novel

From the Desk of Emylia Hall.

I’ve recently been dipping into The Gifts of Reading, a collection of essays and literary love letters from the likes of Robert Macfarlane, Candice Carty-Williams, and William Boyd, full of personal meditations on the power of gifting stories. For Robert Macfarlane, whose initial essay The Gifts of Reading inspired the project, the book he gives, again and again, is In a Time of Gifts by Patrick Leigh Fermor. The latter is a particularly resonant, if not bittersweet, title for these times, where we’re trying to focus our gratitude and count our blessings, and reach out to others in need; to do, simply, our best.

A recurring idea in The Gifts of Reading is that giving someone a book is a particularly intimate gesture; you profess to know their soul and are serving it accordingly – which perhaps makes it risky gifting territory for some; I’m sure we’ve all had those conversations where we can’t believe that a friend, so seemingly like us in so many ways, can’t stand the very same book that we love. But there’s nothing I’d rather receive at Christmas – although throw in a bar of chocolate too and I really am set.

I rarely regret a read: if it turns out not to be my cup of tea I usually still feel I can take something from the process, even if it’s just further affirmation of what I look for in a novel, and hope to do achieve with my own writing. That’s a benefit of reading as a writer - even a disappointing novel has value.

There’s something about the days between Christmas and New Year where I feel particularly connected with my writing – or, more precisely, the idea of it, because I won’t be giving it the same desk-time. This is rich notebook territory for me; the secret garden of my novel calls, and curled on the sofa, both within the family and just slightly aside from it – I respond with low stakes scribbles and flights of fancy; it’s play-time, away from the usual graft of the work-in-progress. I always feel especially creatively optimistic through the holidays, hence why I’m more likely to reach for my notebook rather than the TV remote (though there’s plenty of that too). Perhaps it’s the letting go of other responsibilities, so the work I love most looms largest in my imagination. Maybe it’s checking out of social media and news and all manner of other realities, so what remains is purer and solely mine. Or just the feeling of goodwill and hope – even in a year like this one, as Tracy Thorn sings in Joy (a particularly grown-up and exquisite Christmas song) ‘it's because of the dark, we see the beauty in the spark’ – and this attitude extends to my writing. At any time of year, our novels and the time to write them, are the greatest gifts we can give ourselves.

A few Christmasses ago I received Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert, and it instantly became one of my favourite books on creativity. Consider these words from Gilbert:

‘Surely something wonderful is sheltered inside you. I say this with all confidence, because I happen to believe we are all walking repositories of buried treasure. I believe this is one of the oldest and most generous tricks the universe plays on us human beings, both for its own amusement and for ours: The universe buries strange jewels deep within us all, and then stands back to see if we can find them.

The hunt to uncover those jewels — that’s creative living.

The courage to go on that hunt in the first place — that’s what separates a mundane existence from a more enchanted one.

The often surprising results of that hunt — that’s what I call Big Magic.’

How I love ‘walking repositories of buried treasure’.

I’m currently starting out on a new idea, and hunting for those jewels – the gems that will decide its colour and shine – is one of the best parts of the process for me. The fact is, a novel is pure promise up until the moment where we decide to let it go. Then… well, then it is what it is). But until that moment, it can still be anything we want it to be – if we’re brave enough to embrace those difficult questions and act on the answers. Rewriting can feel daunting – physically daunting sometimes too; I’ve had that feeling where I’m clambering into a novel, hauling sentences, and the exertion required is way more than mental – but when it comes down to it, it’s just rewriting, isn’t it? I’ve walked away from a novel before too, and that was every bit as liberating as pulling it apart and rebuilding it might have proved enlightening. Sometimes we need to remind ourselves that we’re the ones in charge – and where control in other parts of our lives might feel in short supply, this is something to cherish. With our novels, we decide. They’re worlds of our own making. And the worst that can happen? We learn. We fail better. We go on.

I keep my first Burton snowboard propped up in my writing hut (thank you Christmas 2001). The logo on the deck features an arrow and is said to represent progression – something you have to embrace if you’re hitting the mountain – and that’s why I keep it close by when I’m writing. I started on my first novel when I lived in the French Alps, so blank pages and pure white snowfields will always be linked for me, but its talismanic status goes beyond that: the sight of my board reminds me that if we love something we keep going at it, we take the knocks, we strive to get better, and occasionally we hit those moments of pure flight that make it all worthwhile. And we better make our peace with our fallibility (I’ve a chipped coccyx and a curiously numb patch on my left knee attesting to that). Through the novel-writing process, of all the things we learn about craft, we also learn about our own resilience, commitment, desire, and persistence. When we sit down to write, we come face to face with ourselves, and that can be revelatory, inconvenient, downright bruising; but it’s always a worthwhile encounter.

Here I offer you the words of another wise woman, novelist Ann Patchett. She talks of the inevitable gap between immaculate ideas as they live in our limitless minds, and how they end up on the page:

‘When I can’t think of another stall, when putting it off has actually become more painful than doing it, I reach up and pluck the butterfly from the air. I take it from the region of my head and I press it down against my desk, and there, with my own hand, I kill it. It’s not that I want to kill it, but it’s the only way I can get something that is so three-dimensional onto the flat page. Just to make sure the job is done I stick it into place with a pin. Imagine running over a butterfly with an SUV. Everything that was beautiful about this living thing — all the color, the light and movement — is gone. What I’m left with is the dry husk of my friend, the broken body chipped, dismantled, and poorly reassembled. Dead. That’s my book.’

Patchett believes that acceptance and forgiveness are what lets us get beyond the point of dismay, and carry on, writing the best books that we’re capable of. Being kind to ourselves, while also pushing for our best work, is a delicate balance. It might feel like a continual inner conversation – one made of coaxing, chastising, caressing.

Many of us have struggled this year, and when we sit down to write we have only the insides of our minds for company; when those minds are restless then focus can be hard to find.

Be gentle on yourself, and know this: your work has the potential to be that spark of which Thorn sings; see and feel its brightness, and trust in it. Writing a novel is – with its highs and lows, its questions and answers, its ebb and flow – a process through which we ultimately get to know ourselves better, and is a formative experience that transcends the manuscript itself. A novel and a more connected self, all wrapped up in one package? That’s got to be a gift that keeps on giving.

Give someone the gift of their novel in 2021 with one of our courses. More here.

Get ready to write your book in 2021. Sign up for our Book in a Year plan here.

December 19, 2020

Pantomime and Story

From the Dressing Room of a Dame.

(Philip Meeks is on enforced sabbatical from pantomime, writing his novel with The Novelry. Photo © Bob Workman.)

On the day I turned three, my life took such an irrevocably warped turn I never looked back...

I wish the opening sentence of my novel had come as easy.

I’d been a model child which is probably why I’ve been anything but as an adult. I was white-blonde haired with a deep brown-eyed searching stare. I’d have been a Midwich Cuckoo if I’d had the attention span. Elderly neighbours came to sit and stare at how I ate my meals precisely, foodstuff by foodstuff, without moaning or mess. My mother says there was silence as they tried to work out how they’d gone so wrong with their own mash-splattered sprogs. I learned to speak too soon, I was walking within months and I had the early shoots of lively curiosity and imagination clearly on display.

But I fell asleep when storytime started. I chewed rather than gaze at picture books. But then my fourth year dawned and I was taken to see Cinderella at the Theatre Royal Newcastle. And I experienced a story.

Just as the first stories had been spoken to children around firesides this story was alive and in front of my eyes. Not only that, I heard it in a way words hadn’t to that point described any other story before. As the fairy flashes set off a bonfire of atmospherics and the sugared jelly fruits warmed in the clutches of grannies around me, I smelt it. Every time the big drums played, or a character cackled or the audience yelled, I felt it resound within me. I learned story could be about sense and feeling. This instilled within me the majesty of story, turning me into the reader - and writer - I am today. The live experience changed my perceptions and my imagination was ignited. Yes.

At first, I was fascinated with the red velvet seat I was struggling to sit on that flipped up and down if I wriggled. And when the room turned dark I was possibly a bit startled even if I’d always been Wednesday Addams at heart. But the colour and eruption of sound and energy hooked me. By the time fabled British comedy actor Terry Scott (long before Morecambe and Wise had breakfast) did his celebrated pantomime strip as an Ugly Sister, I was ruined. To this day I only have to hear the brassy intro to David Rose’s The Stripper and I’m compelled to take my coat off. If you’re lucky I stop at my gloves.

Cinderella captivated all of my sensibilities and the way I remember feeling then became a lifetime affliction. Storytime was never the same, whether I was hearing, reading, or writing the story at hand.

But I’ll be honest, today I’m often cynical about pantomime.

“Because here I am now a poor widow woman….. it's sadder than that…..my husband died drinking milk….the cow fell on him.”

By which I mean to say, when I was eighteen gave up acting as a career and decided I’d return to it when I was of an age to play Pantomime Dame. I'd seen all the greats as a kid from George Lacey to John Inman and I was transfixed by the character. Through luck, fate, my knack for hustling and sheer cheek it happened ten years ago. ( I write this in the middle of what would have been my 11th season in a normal year… and my second show and thirtieth costume change).

I’ve been Twankey to a Blue Peter Presenter and the Chuckle Brothers (I don’t discuss that). Played Nurse or Dame Trott opposite Linda Lusardi, Su Pollard, Benidorm’s Janine Duvitski, and a whole advent calender’s worth of soap actors. My first season was Snow White, which I wrote and directed. It was performed in sub-zero temperatures in Arbroath. On Christmas Eve we had to dig the dwarves out of the snow before the matinee.

It was a midlife crisis I’m still yet to shrug off. Some run off with dirty blondes. I became one.

It’s been a blast, but I’m jaded and sometimes I doubt its magic. I question its commercialism and the corners producers cut in terms of storytelling as well as budget. Sometimes I doubt it should be the first introduction to the theatre kids in this country often have. But it is and probably always will be. So there’s a writerly lesson to be learned here for me ( and maybe us all, dear readers). I shouldn’t let being a Dame become a job, just as writing never will be merely ‘a job’. In my wigs, frocks and lashes I am in the role of author/ storyteller. We have to live up to our readers, to the audience's expectations. They are our future.

Any screenwriting course in the world will ask you to study Pixar movies to understand storytelling processes. But they aren't new. There’s a reason Disney started telling legendary children’s stories. As well as pantomime producers. These tales have survived for centuries and have been told in so many forms and ways. Children are the most discerning of audiences and appreciate any tricks or twists you might through their way in addition to the fixed points of the stories they know and love. But they’ll let you know if you get it wrong too. (Woe betide you if you’re a blonde who attempts to play Snow White and don’t go on with a black wig!) They learn from their first exposure to a story, the experience involves their thoughts and a range of emotions. And it is their right to experience it the way they want.

Pantomime can help the core concepts of story explode into the hearts and minds of young audiences. They follow a basic hero journey. And they all have The Novelry's Five F’s clearly on display! In fact, some seasons by the end of the run, I’ve often found a sixth F and it's very short. (We’re back to the Chuckle Brothers.)

In pantomime structure, there’s a short first act where we’re introduced to our protagonist, their antagonist, and their quest which is usually to find fame or fortune. At the start, they’ll usually be a bit big for their boots (especially Puss) but by the end, they’ll have worked out being true to themselves along with family and love means more than anything money can buy. (This is easy for them to say as they almost always end up richer than a Netflix executive after lockdown.)

Along the way, the hero’s Mum and friends supply subplots in the form of comedy sequences and familiar routines. The midway point is always signalled by something called the Transformation Scene. Cinderella becomes a Princess, Jack climbs the Beanstalk or Aladdin befriends the Genie and becomes a Sultan. This point of no returns is then hammered home by the ensuing toilet break, ice cream, and a chance to say what you loved most so far as you spend the interval wondering what’s next.

In Act Two the hero will, in the midst of increasing chaos and running gags, find glory and undergo a moral epiphany after experiencing the worst possible moment of their lives. Cinderella forgets to tell the time and misses midnight. Aladdin’s foe seizes control of the Genie. The Wicked Queen poisons Snow White with a magic apple ( I’m to be found sitting in the wings cheering at this scene) and during these crises, our hero tends to reevaluate everything, get rescued, do the rescuing. They end up triumphant and a bit better than they were before - as long as in the future they avoid thinking those two terrible words, “I wish”.

At this point, might I say these story beats can today seem a bit dated? I’m ever the first to shout them down and work out another way of telling the same story in rehearsals. We have a duty to the audience and especially the tiny girls who rock up dressed as one Princess or another. It’s bad enough their parents seemingly want them to believe the best thing that could happen to them is they meet a handsome prince. So when I write pantos as well as perform them, it's Wishee Washee who gives away the lamp and Sleeping Beauty who ends up rescuing the Prince by curtain fall. Many of my own scripts (available to license at a very reasonable rate) dilute the boy meets girl elements of the original stories completely and they still work. Kids have never liked ‘the sloppy bits' in pantomimes so why they remain bemuses me.

But back to how pantomime structure helps create story hungry citizens of tomorrow. WE’LL HAVE TO DO IT AGAIN THEN WON'T WE? is what we say in the ghost gag when someone once again has been scared offstage and we need to sing another verse to keep our peckers up.

Pay attention! The story information in panto is reiterated throughout. The moral of the tale is echoed and reinforced by whispers from grannies and parents. The values our hero should aspire to are repeated and what’s at stake is always at the forefront of the action. We are reminded constantly what is right and wrong and we know when our Protagonist has strayed from the path ( literally in the case of Red Riding Hood). Pantomimes are morality plays. These values guide the adventure.

Perhaps it’s the way it should be in our novels too. Pantomime survives because it contains the DNA of every single form of storytelling.

For The Novelry writers across the globe, if you remove this provincial panto-style and apply any type of children’s theatre, you’ll come up with the same result. I’ve watched the Grinch in New York on Christmas Eve and felt the same thrill from the kids around me.

But there’s one thing pantomime inspires that other forms of theatre and, thankfully books never will. It’s interactive nature. The audience can speak, the blighters. They can even become the story.

Once exposed to the format the young audiences learn the lines they’ll use again and again every Christmas. The “It’s Behind You’s” and all the hisses and cheers. They can’t remember learning these; they find them embedded in their souls via a sort of narrative osmosis that leaves traces of all the best storytelling within us. They are compelled to join in by and with their adult companions. And sometimes anything goes. Aside from the pint of lager thrown at me in Sunderland after I mentioned Newcastle United and the front row marriage proposal which resulted in a restraining order, I’ve been lucky in the heckling stakes. Everyone’s a bit scared of the Dame after all. At least the way I play it.

My favourite audience ad-lib tale has to be when, in her last Palladium panto, Cilla Black asked the boys and girls what she should do to punish evil Abanazer. To which a child in the stalls shouted, “Sing to him!”

Philip Meeks is an award-winning playwright, who has written for stage, radio and television. He is a much-loved member of The Novelry writing his first novel with us 'Mere Mortals', a take of horror among ordinary folk.

Wishing you all, wherever you are, a safe and peaceful Christmas - and a happy new novel. If you're thinking about joining us, this would be a very good time. Let 2021 at least bring each and every one of us a new novel.

December 12, 2020

The Novelry Writers' Annual Report 2020

Christmas comes to The Novelry in the form of completed novels, so many first drafts, awaiting their next draft in the new year. Congratulations to all of you for making sure you didn't rely on Santa for your best gift this Christmas! The year in fiction was a blessed relief versus the year in reality. We drew close at The Novelry as writers and enjoyed time together online, in our own good company and with well-known authors too.

We have learnt so much this year by pulling together. This was ever the vision enshrined in our logo - the octopus. One shared mind bulging and many tentacles writing!

With some three hundred novelists writing with us presently, we have our tentacles on many works of fiction. At The Novelry HQ, we keep our tabs on our writers novels as a team thank to a wonderful 'doctors system' updated in real-time by our writers' activities withing their online course, and at every one-to-one tutor session. We have instituted a Monday team meeting as tutors to discuss our writers and share our thoughts on their stories so that each and every writer - while working one-to-one with a tutor - gets insights and thoughts from the team. Those meetings are sprawling and gleeful. We're so proud to champion each of you!

The rear reality outside spurred us to make it warm and wonderful inside The Novelry for our writers with live online sessions every week whether team chats, the new Story Clinic, the Louise Doughty Bootcamp, or live guest sessions.

We added wonderful tutors; Katie Khan, Emylia Hall and Kate Riordan. (I'm so thankful and appreciative of how they go the extra mile for our writers.) The redoubtable Louise Doughty joined us as a guest tutor for most of the year. We hosted authors: Mark Billingham, Kate Hamer, Joanna Cannon, Clare Pooley, Harriet Tyce, Susie Nott-Bower (our homegrown talent), Ruth Ware, Paula Hawkins. We raised funds to send one of our young talents - Aprajita Agnihotri - to study for a BA in Creative Writing in the UK at UEA. We sent another writer on a full bursary plus living expenses for a year to study for an MA in creative writing. None of this could have happened without you, so thank you for your part in making dreams come true.

Here's a small list of wise saws from The Novelry to see you into the next year. Whatever it may bring, you will always have your own precious, private world to turn to on your writing, and the warm support of your community of writers writing worldwide. On a dull day or a dark day, it's bright at our new home, hub and haven - The Novelry Live.

Problems! Love them. List them. If you can see it, you can fix it. It's the fix that gives your work an extra bounce. Your ingenuity makes the novel unique.

Write into the void. Have questions, don't have answers. Creation semi-blind is somehow richer than patching old material and old ideas that belong to other years. Write a small amount daily as a daily practice

Write to your own standards and timetable, nobody else's. This is the part of your life you own, nobody else. Set your standards high by reading. Don't ask others what they think, until it is done to your standards first, and the standards set by published peers. (Published authors! Get off the treadmill and reclaim your time, your authority, your authenticity, your art form.)

Pick up your plot by the midpoint and let the events fall either side. Darker to lighter. From confusion to clarity.

Let structure serve story; settle the matter by choosing the only way to do this story full justice.

Your main character starts broken, ends whole. If temporarily. This change is the drama of story. Your main character might well be the person least suited to the situation you're putting them in, and the one who will experience most change.

Keep the stakes high, and raise them with every draft. What's at risk here? It better be an emergency either physically or morally. The reader simp,y has to find out (and take part.)

Festina Lente. Get a first draft down fast to find the story. Love it into being in successive drafts.

'You are the music, while the music lasts,' T.S. Eliot. You . Your very being here is the music and the magic. Your novel is just one vessel for some of it, but it's not a gift given by some elusive donor that can be taken away. You are the gift. This time, next time, every time. The novel is a byproduct.

It will always be new. Every novel is new, you will never stop learning your craft. No artist does. Befriend mischief, make mistakes, and hunger for a split-second of clarity more than a few months of acclaim. If you can do this, you have a purpose and a calling for life that will bring you unimaginable joy.

We have spent this year working together and drawn close. I salute you all, my writers, for your courage and wit, your kindness and generosity. We grow novels at The Novelry by loving what's good about them and tinkering merrily as elves in a workshop with what's not quite working. We've been whistling while we work, regardless of the outside world. No one can ever take from us what we have made.

This year has seen our writers placed on many of the awards lists - the Bridport Novel Prize, the Bath Short Story Award, the Mslexia Novel Prize, the Mslexia Short Story Award, the Financial Times Essay Prize, the Retreat West Short Story Prize, the Flash 500 prizes. Here's the annual report from some of our writers writing in lockdown in 2020. A round of applause for all of you and here's to more happy writing in 2021.

Anand Arungundram Mohan is working on his book Eden to Spaceship Earth, fantasy fiction for the middle graders coming soon.

I will be finishing my first draft by Dec 24

Alex Webber Smith is currently working on her first novel, a children's fantasy story about mothers and daughters and magic

I finished my first draft.

Angela Billows is working on the 3rd draft of her novel, Blue Fox, her debut novel.

Longlisted Mslexia Novel Award 2019

Anne Clermont is the author of Learning to Fall, a novel, and is finishing her first draft of That Summer at Lake Geneva, a fiction novel.

Awarded the EQUUS Film & Arts Festival Equine Fiction award

Anne Dorst is the author of If You Say So, a romance for those who don't believe in love.

Working on the last draft

Cara Bryant is the author of a crime novel The Lake.

Published short stories

Carla Jenkins wrote her first draft of Fifty Minutes during lockdown and is in the process of refining it through The Big Edit course.

Longlisted for the Bridport First Novel Award

Carol Sanders is the author of the historical fiction novel set in the 1930s, Where Daisy Belongs.

D1 on the shelf. D2 in process!

Carol Williams has completed the first draft of her historical novel The Barber's Daughter set in wartime Normandy.

Finished a first draft.

Caroline Davies is the author of her first novel in progress The Haven for Lost Souls. She hopes to have the final draft complete in the new year.

An honourable mention in The Firestarter competition. Three full manuscript requests.Two very productive sessions with my tutor Katie Khan.

Dalia Astalos is the author of YA novel Abigail’s Canyon and is at work on her 5th novel coming soon

Finished my first draft of YA novel

David Hogarth is the author of the first of three Biography/Humour Novels Rise and Shine Little Man and is currently working on the second instalment.

Completed last draft

From gothic to garden: Debbie Lily Jones is looking forward to completing her garden memoir About the Garden in 2021.

Completed my gothic novel, Windwhistle.

Eimear Lawlor is currently working on her second novel set in Ireland in 1940.

My book Dublin's Girl is going to be published in January by Aria Publishing (Head of Zeus). I have a three-book deal and am working on my second novel.

Elissa Elliott is the author of her Up Lit novel The Improbable Beauty of You.

Just finishing the millionth revision of a second novel and preparing it to send out

Elizabeth Gowland is the author of her literary romance novel No Ordinary Love.

I've finished my first draft.

Gilli Fryzer is at work on her first story collection.

Winner of Mslexia Short Story Award 2020.

Graham Roos is a writer and creative artist whose work has spanned the media of poetry, film, opera and theatre. He is the author of two books - Rave and Apocalypse Calypso. He is writing his first novel The Complicity of Eve and is working on a new play for 2021.

I have just started the second draft of my novel, completed this season's cinepoem - Lullaby to the Fall - and my new show - Cocktails with Vivien - was sold out just before lockdown.

Hannah Parry is the author of her book club novel Breathing for Both of Us. She is working on her second novel about surrogacy due in Spring 2021.

Finished the last draft in January of book club fiction about a paediatrician and big pharma. Got my first agent. Now thirty thousand words into women's commercial fiction manuscript about a woman who unintentionally becomes a surrogate.

Helen Eccles is working on her Up-Lit Novel, I and Me and We and Us coming soon March 2021

I completed my first draft in 90 days and draft 2 is underway. I had a story published in the Retreat West anthology shortlisted in the 2020 short story competition.

Hemmie Martin is the author of an Up Lit Novel, The Not So Quiet Life of Samantha Crawford and is busy plotting her next novel.

I've completed the final draft of my novel, synopsis and agent letter.

Jacquie Morrison is the servant to her magical realism story narrated by a bottle of wine; Uncorked. Her novel seems to have confused the notions of service and slavery, and has led Jacquie Morrison on a merry dance.

Finishing the 719th draft of my novel Uncorked.

Jane Mansour is editing Pockets of Air, her first novel, contemporary women's reading group fiction.

Finished my first draft. Longlisted for the Louise Walters page 100 prize. Longlisted for the Flash500 Novel Opening 2020 prize.

Joseph Greenberg is working on his 6th draft of Dreamkeeper, a medieval adult fantasy.

I have finished 5 drafts of my novel.

Juliana Adelman is the author of two books of nonfiction and is working on her first historical crime novel.

Finished first draft

Justine Gilbert is the author of two novels, The Beginner's Guide to Love & Forgery a romance e-published in 2008, and a gritty crime drama A Dividing Line Indie published in 2019. She is currently at work on her third novel, a fictional memoir of a real-life mistress of FDR.

I am editing my completed novel.

Kay Brass is the author of Borderline her first novel.

Reached the halfway point of my big edit and found a new passion in 2020 - creative writing!

Louise Tucker is the author of The Last Gift of Emmeline Davis (currently on submission) and has nearly finished the first draft of her second novel.

My novel is, after three edits, on submission to 14 publishers.

Lucy Barker is working every day on her novel, the opening 10k of which won her second prize in last year’s Curtis Brown First Novel award.

My achievement: getting words on the paper every single day since I started. From dangerous binge-writer with a history of giving up at 20k, I’m now a steady, healthy writer happily working my way through the final third of my first draft.

Madelyn Moon is the author of the best-selling women's fiction novel, The Life Coach, as well as two nonfiction books written in her early 20s.

Finished more than half of my first draft.

Maeve Henry is a freelance copywriter, currently finishing the second draft of her novel, The Absolution of Auden Carey, a work of literary fiction.

Nearing the end of my second draft

Melinda Sabo is the author of personal essays on creativity and is hard at work on a fantasy novel coming soon.

I completed my first draft in late January and I'm halfway through the second draft. Best of all? I'm loving it!

Michelle Pilkington completed her MFA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University in 2020. She then completed a final edit of her novel, A Life Half Lived, a domestic noir/family saga with the support of her new friends at The Novelry.

Completed last draft, synopsis and covering letter and an agent has requested to see the full manuscript

Mish Cromer is a person-centred therapist and author of Alabama Chrome. She is working on a collection of short stories and a novel.

I published my first novel.

Olesya Lyuzna is the author of her 1920s feminist noir novel Brickbats and Bouquets.

Finished my third draft and got accepted into the Pitch Wars mentorship program.

Philip Meeks has written for stage, radio and television. Published award-winning playwright writing his first novel.

Completed last draft of my first novel Mere Mortals - a tale of folk horror akin to Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere, had Victoria Wood been my editor.

Sophie Taylor is currently editing her debut literary fiction novel, What Will Survive of Us.

Finished my first draft!

Susie Nott-Bower writes for children. She is the author of School for Nobodies published by Pushkin in 2020.

Finished my next middle-grade novel, The Three Impossibles, which will be published by Pushkin June 2021.

Sylvia Bluck is the author of time travel novel, Hellingly and has almost finished.

Longlisting for Cinnamon and Exeter First Novel Prizes

Tracey Emerson is the author of She Chose Me and is working on her second novel, A Careless Man, with The Novelry.

Almost at the end of another draft of A Careless Man and hope to be sending off early in the New Year. A piece of non-fiction published in the Telegraph's Stella magazine and in the Sunday Life magazine in Australia.

Veronica Birch has just finished her novel Bird Island and is lying down in a darkened room...

Finished my 4th draft.

Victoria Price is an inspirational speaker, author, and most importantly, the one in all The Novelry Zoom meetings with the cute white dog named Allie on her lap.

I had a non-fiction book published in April, but that's not nearly as exciting as this non-fiction writer finishing a reader's draft of my novel!

Viv Frances is the author of her suspense novel Ma and is at work formulating her next suspense novel.

Finishing my 4th draft.

Walter Smith is the author of the political novel, The Candidate, about a man who learns the price of ambition when he seeks office to replace his political mentor.

Winning The Firestarter competition at The Novelry last year was a shock. This was the first writing award for me since I was a teenager. My one publication was a story in a regional magazine here in the American South.

December 5, 2020

Meet Kate Riordan.

We are delighted to welcome Kate Riordan to The Novelry as a tutor. She's a wonderful addition to the team and it's great to have her with us. She's off to a flying start, and available for sessions now. Find out more about Kate and her novels here. Her first historical novel published by Penguin was hailed as a must-read for fans of Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. More recently, with her fourth novel, Kate has made a move into writing psychological suspense with the thriller published this summer - Heatwave.

Come and meet Kate 'in person' at our special session on Wednesday 9th December at 6pm. Members can book in at the booking page.

From the Desk of Kate Riordan.

My favourite film growing up was Back to the Future, which came out when I was seven. I went to see it with my dad at the Odeon in Muswell Hill and, during the walk home, euphoric from the film which had held me rapt for 116 minutes, I fired questions at Dad about the space-time continuum (he did his best). But what had really stolen my heart was not the physics behind the Dolorean’s flux capacitor. It was the 1950s. I couldn’t for the life of me understand why Marty was so keen to get back to the eighties, with its litter and homelessness and dysfunctional families, when he could have stayed with Doc in ‘good ol’ 1955’.

The same year, during a holiday on the Norfolk Broads, I had a peculiar experience with my mum at the site of a Roman fort. It was one of those overcast English summer days which only clear as evening approaches. Under clouds yellow like old bruises, Mum and I were playing with a ball when something shifted and tautened in the air. I felt absolutely certain that I was about to see - almost could see - a procession of Roman soldiers. The ground seemed to vibrate from the stamp of their boots. Without a word to each other, we ran. I don’t believe in ghosts. And yet…

The Jesuits said ‘Give me a child until he is seven years old, and I will show you the man’. Well, when you boil it down, it was those two experiences that made me want to write historical fiction. There’s something deeply seductive about a place you can never visit; where - to paraphrase LP Hartley in The Go-Between - they did things so differently. It’s the ultimate form of travel. For me, the best examples of historical fiction have a seam of yearning running through them because the writer understands that, whatever she does with her characters, they are somehow already doomed. (I like sad books.)

Lately, though, I’ve felt the pull of my own times. Maybe I needed to hit forty; to accumulate enough years to be able to look back across them with some objectivity. Or maybe it’s a confidence thing, because it’s true what they say: you do give less of a toss about what people think as you get older - one of ageing’s few upsides. I realised that my historical settings had acted as a protective barrier between me and the reader - because surely no one would suspect this character of being part-me if she was wearing button-boots and a corset?

In fact, good historical fiction isn’t just escapism. It also attempts to shed light on contemporary concerns and fixations - the idea being that time travel, like any other kind, can help us see patterns and truths that might elude us when we’re too close to home and our own everyday experiences. Nevertheless, in terms of my own writing, I was beginning to feel a bit constrained. There was a limit to how much I could explore the kind of fraught family and relationship dynamics I was interested in when writing from the perspective of a hundred years ago. The female experience in particular has changed so radically, even in the last few decades.

In my first novel, The Girl in the Photograph, I wrote about a depressed woman in an unhappy marriage who is fearful of being sent to an asylum. All it required in the late 1800s was a husband’s signature. As a premise, this is as richly interesting as it is terrifying. But having done that, I found I wanted to write about what happens when a marriage falls apart now: the quiet, heartbreaking drift from soulmates to housemates.

There were other reasons I began to be pulled more and more towards the present. For one thing, I was never one of those historical writers who secretly loved the research more than the storytelling. When I sat down to write The Heatwave, much of which takes place in 1993, it was liberating not to have to look up the historical details, to cross my fingers that I’d got it right. Also, as a reader, I really love the particular in books. If a character observes the exact weird thing I’ve noticed myself about the world, it’s such a comfort. As the kids would say, you feel seen. In the film Shadowlands, CS Lewis says, ‘We read to know we are not alone’. Lewis may not have said it in real life but it’s a lovely concept; the writer reaching out across the ether to take the reader’s hand.

With The Heatwave, I unashamedly plundered my childhood memories of holidays in the south of France in high summer. I wrote about the glass mustard jars you washed out and kept afterwards because they were covered in Disney characters, and of the pillowy sweetness of Bonne Maman strawberry jam stirred into fromage frais. I didn’t need to head to the British Library to check this stuff was right. I knew it. And those kind of specifics resonate with readers, either because they know them too, or because they’re deliciously unknown and exotic. Either way, they feel real because they are. These tiny things punch above their weight, lending conviction to the whole story.

Yet despite my brave intentions, The Heatwave is still very much a transition story. Although the ‘present’ day is 1993, the narrative also flashes back to the late sixties and seventies, which I did have to research. Apparently I find it hard not to go back at all. The book I’m working on now is another tentative step towards true contemporary fiction. It’s set in a vague, pandemic-free now and I am genuinely excited to be writing about dating apps and sexting. But there’s only so far I can fight my old passion for the past, which set hard inside me so long ago. The story’s central paradox (thank you, Louise!) is that my protagonist is trying to find love and contentment for the future with a dangerous old flame from the past. What has gone before still hangs heavily over today, informing, colouring and perhaps dooming it. I might have moved away from historical in the general sense, but my characters are still products of their past experiences, just as we writers are, whether we like it or not.

Happy writing,

Kate.

November 28, 2020

Writers Apps.

The Top Ten Apps for Writers? Who are we to say?

We are The Novelry. The writing school for novelists at all stages of their career worldwide. With hundreds of novelists - aspiring and published - writing at any one time, and thousands of members, we know a thing or two about getting novels done. These are the tools we prefer to use.

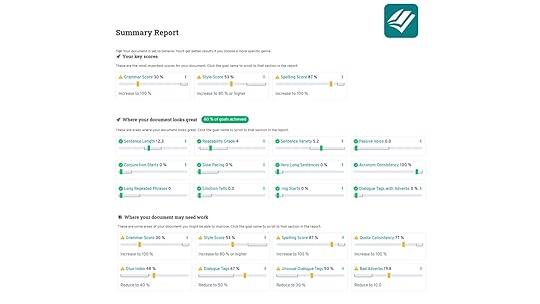

#1. ProWritingAid

It just gets better and better! We enjoyed a live session with its founder recently - available for writers of The Novelry at our Catch Up TV. The app analyzes your writing and presents its findings in over 20 different reports (more than any other editing software). You can keep track of your writing style with a neat integration of ProWritingAid and Scrivener. ProWritingAid imports your Scrivener folder into its platform and gives you a detailed analysis of how you're writing. I use ProWritingAid for that final finesse. Here's their latest news: they have launched a new Word add-in for Mac users. It was their most requested development for years! Find out more about the Mac add-on here.

Now, what else? Their sexy new summary format! That's what, and it's why ProWritingAid tops our list of apps for writers this year! Congrats to the ProWritingAid team.

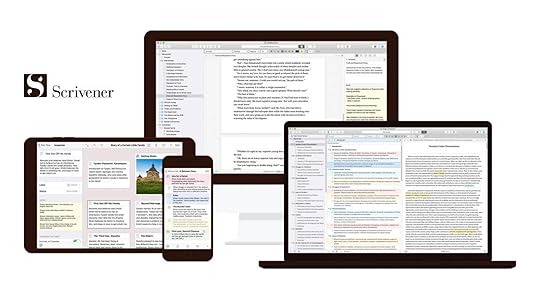

#2. Scrivener

The original big project planning writing app. Almost all novelists have come across this. Tailor-made for long writing projects, Scrivener banishes page fright by allowing you to compose your text in any order, in sections as large or small as you like. Our members at The Novelry can enjoy a 20% discount on Scrivener at our Members' Library.

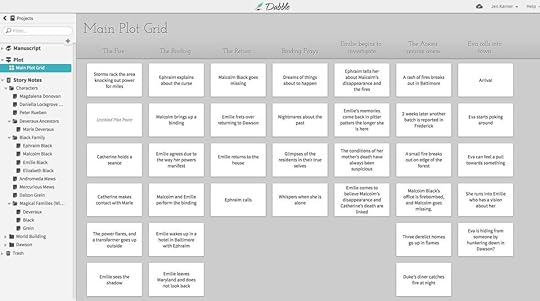

#3. Dabble

A new entry for 2021. A simpler version of Scrivener for those under time-pressure or technologically challenged! Many of our writers now enjoy using this. Dabble organizes your manuscript, story notes, and plot. Dabble simplifies story. It provides a plot grid, plot lines (subplots), and plot points. It helps you set word count goals. Write in the desktop app on your Mac or Windows computer at home. Write in the browser at work or offline over the weekend. It syncs to the cloud. Dabble keeps a full copy on each computer and one in the cloud. These copies sync with each other when they are online. Includes a dark mode. A distraction-free simple way to write. The standard plan is $10 a month. Pricing here.

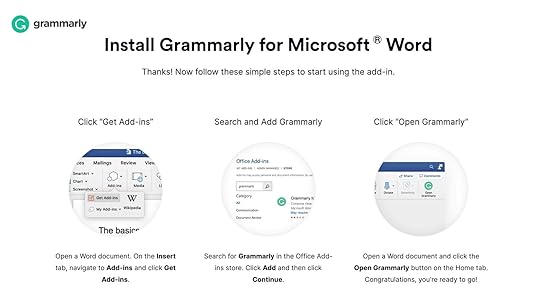

#4. Grammarly

A must-have for writers. Install the plug-in and everything, even social media, gets a clean sweep before it goes out. Go premium. It's worth it. I consider this an essential and like the way it checks everything I do as I write online. I wouldn't press 'enter' or hit 'send' without it. The latest news is that you can now use it within a Microsoft Word Document, and install it in your desktop, or use it on your browser or mobile. For sheer elegance of purpose, I prefer Grammarly to help me look smart.

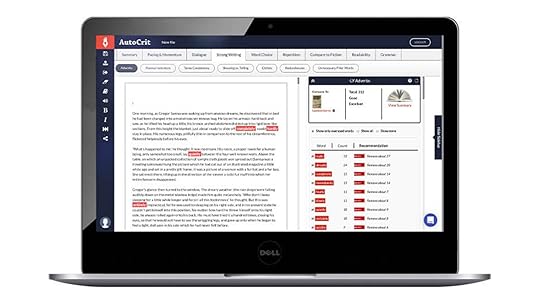

#5. AutoCrit

AutoCrit analyzes manuscripts according to six categories: dialogue, strong writing, word choice, repetition, compare to fiction, and pacing and momentum. The software dynamically adjusts your editing guidance based on data from millions of published books across many different genres.

What I love about AutoCrit is the design of the summary report which includes a word cloud and enables you to take a look at the health check for your prose at a glance. It offers a nice natural voice read-aloud feature too. You can, at the flick of a switch, pluck out them adverbs and passive phrases, should you wish. AutoCrit picked out my overused words in a way I've not seen so obviously shown before.

"With AutoCrit, you can compare your work directly to real, published fiction from some of the top publishing houses in genres such as Mystery/Suspense, Fantasy, Sci-Fi, and Romance. Want to know who uses more adverbs, you or Stephen King? Now you can find out!"

There's a free plan too. Love it. Try it.

#6. The 'Book in a Year' ® Plan

The complete program for writers old and new at The Novelry. A year of complete guidance and support to write wisely and fulfil your ambition as an author. The Novelry will lead you through the creation of a sound and appealing story idea onto writing a novel, then revising and editing your first draft. You will complete and hold in your hands a final draft ready to pitch to agents with our dedicated help and support every step of the way. Choose the safe and smart way to stay on track and achieve your ambition to get that book done. Sign up here and save 20% on the prices of courses when sold separately.

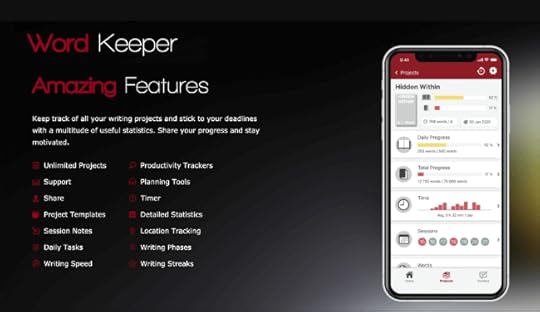

#7. Wordkeeper

A writers' statistics tool for iPhone and iPad. Keep track of all your writing projects and stick to your deadlines with a multitude of useful statistics. Share your progress and stay motivated. Available on Apple and Android here.

#8. Shortlyread.

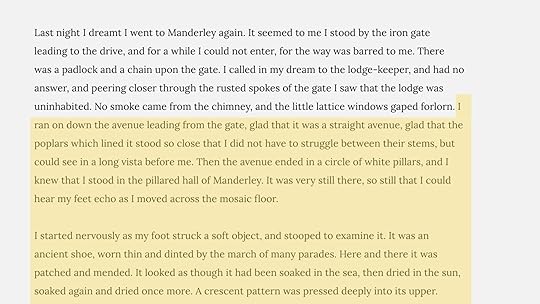

Surely not! You wouldn't use this would you? Writer's block? Not something we're familiar with at The Novelry! But if words fail you, this will fill them in. At $14.99 a month. It defies belief. Check this out. So I inputted the opening lines of Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, and asked Shortlyread to do a little more. And here's what it's AI wrote based on that small sample. I think it mimics the phrasing very well considering its machine-made:

Part of me dreads to think where this could go, but hey, you remain author and get to edit it, right? And it's all in the edit! When you want to craft a fabulous final draft, head on over to our Editing Course!

#9. PickFu

Want to get feedback on your story pitch or your novel title? You can run a poll using PickFu to a minimum of 50 respondents in the USA from $50. You can narrow your audience to heavy book readers of fiction, and other criteria to check your candidate titles against your prospective readers.

The comments give you food for thought, allowing you to see what inference each title is cueing. You can see how each title performs against age groups and genders.

You can get feedback on your book premise or description too. You could run the poll against 500 people. Given the audience targeting features, I think this would be useful right at the beginning of scoping out an idea. (Don't use it for feedback on your work! Work at first draft with a dedicated author mentor, and never expose first drafts to the foolishness of 'workshopping!')

#10. Otter Voice

Record conversations using Otter on your phone or web browser. Now integrate with Zoom! Get real-time transcripts and, within minutes, rich, searchable notes.

Otter AI faithfully transcribes voice to words. I was stunned watching it automatically finesse and correct the word before my eyes. You can import recordings too and get a notification when the transcript is ready. You can use this app for free and get 600 minutes of transcription time. For less than $10 a month you can export files as documents, skip silences and sync all your files via Dropbox. It's the ultimate tool for dictating your novel or getting reality recorded and onto the page.

Use it to collect the cadence of conversations and the sounds around you to bring 'buttoned-down detail' to your prose. Unlike Just Press Record or other recording apps, the words appear before your eyes and make sense and next to the words is a second by second timeline making it easy to locate passages. A replacement for two apps - voice recording and dictation. Get it here.

And finally, stay healthy.

Date and save your manuscript daily and keep it on the cloud, and keep your equipment clean. I dote on this baby. CleanMyMac (they also offer CleanMyPC). I'd probably have bought a new Mac had it not been for this gorgeous app which rids me of my data grime and keeps my RAM moving. I wouldn't be without it. For me this is an essential.

Free Tools for Writers

Because sometimes it eludes the best of us... Whether you're writing ads for Google, SEO titles, or working on the big novel, sometimes you forget quite how to title it. Head to Capitalize My Title. Phew. Job done.

Wordcounter. So many writers worry about what their word count should be for their 'genre'. Tell a great story regardless of how many words. If you're going commercial you're going to want to hit 70k, but literary's much broader as a range. It's surprising how many favourite novels have low word counts. Sometimes a short book can feel very long, and a long book can feel short! Check them all out for free here.

A cheap and cheerful way to check your writing is offered to you with the compliments of the charming Count Wordsworth. Check the number of times you use a certain word. You may be surprised and what seeds you're sewing in the subconscious of the reader! In the first book of The Bible “behold” occurs more commonly than “there”, “as”, “went” and “we”. For an analysis of the cunning repetitions of words to seduce the reader in The Great Gatsby, you may enjoy this blog article.

In search of an idea for that novel you're meant to write? How about writing one you never meant to write. Try the Random Logline Generator! I hit the page while writing this and found the idea for my next novel in less than 5 seconds. 'A telephone operator gives advice to the anachronistic adopted daughter of a magician in Scotland.' Why have you been fretting over your big idea for so long, you will ask yourself.

When you wake from a gripping dream, look it up and decode it. Writing is one way of finding out what's going on in your head, but dreams are the flash fiction reading of your troubled psyche and can save you some pondering in prose and provide a jumpstart to creativity. Like many writers, I started writing when I started writing down my dreams. Dreammoods App is a free app, and it's on the money more often than not.

For a thesaurus beyond compare if you're writing historical, I strongly recommend the Oxford English Dictionary which will who you what words were used when, but the bog-standard Thesaurus is great and here's another kid on the block for you - Onelook.

Check the differences between drafts very simply with Diffchecker. (Find those old darlings, and restore them to draft 58.)

Scope out the timeline planning for your novel with Mindmeister, the mind mapping tool or with Aeon Timeline. The latter syncs with Scrivener, but I find it's encroaching too much on what Scriv does best. I prefer Mindmeister for getting a good oversight of my story development and I show you how to use it for yours in our Ninety Day Novel course.

Many of us use Canva for design work and to create some of the working tools we use at The Novelry to visualize the novel. It's a must-have, really if you want to create a social media presence.

You can bring all those highlighted passages from your Kindle or iPad iBooks into one place with Readwise.

Shortcuts for keyboard symbols? Look no further than here. Boomark it.

Free ebooks for your Kindle? At Standardbooks.org here.

Get a health check on your novel chapter by chapter at a glance by looking at the verbal DNA with Wordclouds.com. If you're writing a novel you're going to want to see in that cloud our main focus of interest writ large. Remember, a novel ought to have the names of people we're following up loud and proud in your cloud.

Gifts for Writers You Love.

Thenovelry Writers Gifts GIF from Thenovelry GIFs

With courses starting at £95 or $125 - including our new Memoir Course - what better present for your loved one with a book in them? Check out our gifts - sent instantly worldwide - with a personalised gift card to one lucky writer from someone who believes in them - almost as much as we do at The Novelry!

November 21, 2020

Jessie Burton - On Endurance for Writers.

From the Desk of Jessie Burton.

I’m writing this piece less than two days after finishing my sixth book. It isn’t due for another fortnight, but I’ve been thinking about and writing this one since May 2016, and it happens like this sometimes. There you are, thinking you will never see the light at the end of the tunnel, let alone walk through it into bright sunshine. And then you take yourself by surprise. The day is a normal one, you press the last full-stop, and it is done.

A few days before that, however, when I could see I was nearing the end, I felt extremely anxious. I was overwhelmed that I had come this far – having discarded over 96,000 words to get here, changing it many times, sitting in the dark with it for so long. I was swamped by the anticipation of the final push, by the awareness that the book was going to morph from a private into a public thing, and the fact that I would have to say goodbye to it once it was. I couldn’t believe I was actually finishing it. And then, when I did finish it, I absolutely believed that I had. I felt very calm and happy, and then two hours later, I burst into laughter in my kitchen, waiting for the kettle to boil.

I had emailed my editor to say that I would be sending it to her next week and that I had just two more scenes to go. I did this, partly to give her a heads-up that a manuscript was coming, but mainly to commit myself to executing those two scenes. As it turned out, I finished both in twenty-four hours. It isn’t really an end, of course, because now my editor will see it, and my agent, and conversations will begin, and I will have to change this creature probably several times. And after all, even when it’s sitting on a shelf, it doesn’t always feel like an ending. Nevertheless, it is a milestone worth noting and celebrating – because it is one thing to say you are going to write a novel, another to say you are writing a novel, but a whole different ball game to say you have actually written one.

One of the most frequent questions I’m asked about writing is endurance and self-belief. How do you keep going with a novel when you’ve lost hope in it, when it’s swallowed up your confidence, and try as you might, you cannot find your way with it? I thoroughly understand and empathise with this state of mind. Writing a whole novel, as commonplace as it might seem to those in or adjacent to the publishing business, is actually really hard.

What you’re doing of course, when wrestling with a novel, is wrestling with yourself. I don’t really know how I write my novels, and that is because for me, the act of writing them is also the act of living my life, and so if you ask me how do you write, you are also asking me, how do you move through the days of your life? What was I doing with my life three months ago, on the first Wednesday of August? I have no idea. I was most probably at my desk, writing.

This is not to sound grandiose, or to romanticise or mystify the process, or to pass myself off as some monkish masochist. Because what I do know about the accrual of words on the page is that it is, in fact, spectacularly mundane. I plod through the days, and the novel plods too. It is repetitive, frustrating, and an exercise in tender failure. Of course there are transcendental afternoons, when the flow comes, and the novel appears to be writing itself, when the hours and hours you have spent clunking over the terrain of your own psyche have suddenly smoothed out into this unbelievable rollercoaster of perfection. Generally, writing a novel is not a particularly healthy way to live, but seeing as we do not always do the things that are healthy for us, and if you have a novel that you want to write, that you have to write, that, if you are lucky, you are contractually obliged to produce – then you are going to have to find some way to incorporate the production of it into your life, to accept its flawed processes, and yours.

I posted something I wrote to myself on my Instagram a while ago that hit a bit of a nerve, and I’ll put it here: the fact is, that very often, when you’re writing a book, you fear that you are writing it the wrong way – too fast or slapdash, too unthinkingly. That underneath this book, there is another book that as a consequence does not get written, that didn’t even stand a chance in the face of your ego or hunger and impatience. That there was a way to write the book, and you ignored it, in favour of a cheap thrill or a quick hit of feeling something had been accomplished. That you didn’t sit and breathe with it. That you missed detail after detail in your panic. And so there is always the phantom book that exists somewhere, that you will never write. Your platonic ideal of a book, that no one will ever read.