Louise Dean's Blog, page 14

November 1, 2020

Paula Hawkins - On Writing the Unputdownable Book.

From the Desk of Paula Hawkins.

I didn’t set out to write an unputdownable book, but when The Girl on the Train was published, I was told very clearly that I had, and that numerous train stops had been missed as readers were compelled to keep turning the pages.

Unputdownable hadn’t been an aim: I had wanted to write a crime novel about a young woman with a drink problem who suffers from blackouts, because I was interested in how her memory of acting a certain way related to her sense of guilt and responsibility for her actions.

You might want to write a book about the plight of women accused of witchcraft in the late sixteenth century, or about a southern African immigrant’s experience of life in London; your aim might be to write a book that makes people laugh, or reconsider their life choices, or a book that makes them too frightened to turn off the light at night.

Unputdownability is rarely a goal in and of itself. Not everyone believes unputdownability is a good thing at all. Howard Jacobson, the Booker prize-winning literary novelist, wrote a whole newspaper column about how authors ought to strive to write books which are eminently putdownable. Before the end of the very first page a reader should, he argued, be putting the book down in order to think about what the author has written.

That literature ought to be thought-provoking or challenging is hardly controversial; some might argue that it ought to be possible to write provocative and stimulating novels which are also impossible to put down, they might even argue that some writers of literary fiction would do well to pay more attention to compelling narratives and less to provoking thought.

But I do think that the art of inducing readers voraciously to turn the page, the skill of transporting them from the armchair in the living room to some other world they desperately don’t want to leave, for a page or twenty or fifty, can be valued just as much as the art of inspiring the reader to place the book back on the edge of the armchair and ponder the state of the universe.

So, what is it, then, that makes a piece of fiction irresistibly compelling? Spoiler: it’s unlikely to be the plot.

A cracking plot is important, particularly in a crime novel, but it is not what tends to make a novel addictive. For unputdownability, you’re better off considering structure and character.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but if you want your novel to be unputdownable, it helps to have an element of predictability about it. In the early chapters of TGOTT, Rachel’s morning and evening commute gave a definite rhythm to the novel which lured the reader in. They knew exactly where they were, they knew what to expect until – suddenly! – they didn’t.

SJ Watson’s Before I Go To Sleep and Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life have a similar quality (as does the film Groundhog Day!). The reader (or viewer) understands that there is going to be a certain amount of repetition, but they also know that something is going to have to be different, and the anticipation of the change is part of what keeps them turning the page.

Of course, a reader might tire of those early chapters - a woman going backwards and forwards on a train is not, in itself, a thrilling concept – unless the woman herself is very intriguing: readers will follow a compelling character to the ends of the earth. A compelling character needs to be at once psychologically convincing while also surprising the reader, someone whose actions might at first shock or even repel but which become understandable once we understand the background or that rationale behind her actions.

The immediacy of a first-person point of view can help: Rachel from TGOTT was not, on the surface of it, likeable or warm, but readers were afforded direct access to her at times discomforting and strange thought processes and they engaged with them. Readers saw a part of themselves in her, they identified with some element of her isolation or pain or anger and they gave themselves over completely to her story.

A good first-person narrative is immersive in the most compelling way: Lucy Ellmann’s 1000+ page novel Ducks, Newburyport is a singular case in point. Ellmann puts the reader inside the head of a housewife going about her daily life, exposing them to every single notion that occurs to the protagonist throughout the course of her day; the experience is both dizzying and utterly compelling. And memorable in all the right ways: while endless plot twists, cliff hangers and other page-turning ‘devices’ can feel manufactured, a good character never does.

That is not to denigrate the plot twist: a truly surprising or shocking twist is a glorious thing, but for a book to be unputdownable, the reader must on some level be waiting for the twist, they must be expecting something to happen, and still be surprised by what actually happens. My agent puts it this way: a good plot twist is not having no pieces of the puzzle, it’s being given the pieces of the puzzle, one by one, thinking you’re going to end up with a picture of a combine harvester and then suddenly realising you’re looking at a picture of a lawnmower.

The pace at which those puzzle pieces are doled out is critical. A good writer drip feeds essential pieces of information at exactly the right moments, making it impossible for the reader to resist them: they must pick up the crumbs, they must follow the trail into the woods.

Knowing not just the direction of travel but also what one might find at the destination also keeps the reader turning the pages; moreover, knowing how a novel ends can add to the suspense rather than detracting from it. Everyone knows, for example, that Thomas Cromwell will be executed at the end of The Mirror and The Light, and it is in the context of this terrible knowledge that the book becomes almost unbearably suspenseful as the climax approaches. Mantel’s work is a good example of a book that is at once cerebral and propulsive, Kate Atkinson’s stellar Jackson Brodie novels – pacy, intricately-plotted and peopled with memorable characters – also prove Jacobson wrong. You don’t need to choose between intelligence and unputdownability, it’s possible – though fiendishly difficult – to compel readers to turn the page while still leaving them thinking about the novel and its ideas for days and weeks and months to come.

With our huge thanks to Paula Hawkins. More about her work here. Paula will be joining us for a live session for members on Monday 14th November. Join us for a gripping session.

October 25, 2020

Writing Rebecca.

Page-turners don't happen by accident, they're constructed.

A handful of writers have a gift to be able draw upon story structure intuitively. (Very few.) Some writers happen upon a number of the elements of a page-turning story by accident in their first novel, almost unwittingly it seems. But it's likely they've been turning the first story around in their heads for many years.

Most writers work using multiple revisions to structure and re-structure to include make their story gripping for readers, after the first draft. We had a session at The Novelry on narrative structure with Louise Doughty recently (available in our Catch Up TV area for members). As she showed, the virtuous shape of a novel emerges in the later drafts. (We work with writers to fast-track the process, and we have a few short cuts up our sleeve to raise the work between drafts with some heavy lifting between writer and tutor.)

Writing and Re-writing Rebecca.

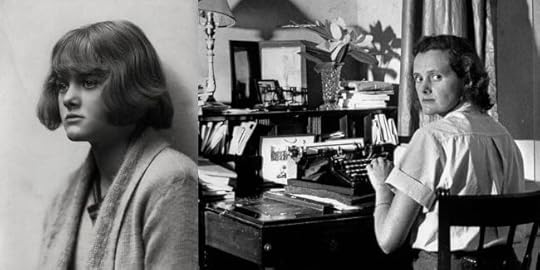

At the age of 30, Daphne du Maurier had already published four novels and two biographies. She published Jamaica Inn in 1936 so by 1937, when she signed a new three-book deal with Victor Gollancz and accepted an advance of £1,000, she had some experience and was able to fast track her process to produce Rebecca as a manuscript for publication in just two drafts. I'm going to show you what she did. It's rather similar to the method we teach graduates of our Ninety Day Novel course in our Big Edit course, prior to pitching your work to our literary agency partners.

Living in rented quarters with her husband in Egypt, du Maurier was homesick for Cornwall and determined to set her novel there. She brought to mind the houses she'd visited with her friends the Quiller-Couches:

And surely the Quiller-Couches had told me that the owner had been married first to a very beautiful wife, whom he had divorced, and had married again a much younger woman?

I wondered if she had been jealous of the first wife, as I would have been jealous if my Tommy had been married before he married me. He had been engaged once, that I knew, and the engagement had been broken off – perhaps she would have been better at dinners and cocktail parties than I could ever be. Seeds began to drop. A beautiful home … a first wife … jealousy … a wreck, perhaps at sea, near to the house, as there had been at Pridmouth once near Menabilly. But something terrible would have to happen, I did not know what … I paced up and down the living room in Alexandria, notebook in hand, nibbling first my nails and then my pencil.

As she wrote in her notebook:

A beautiful home . . . A first wife . . . A wreck, perhaps at sea . . . A terrible secret . . . Jealousy . . .

‘very roughly the book will be about the influence of a first wife on a second . . . she is dead before the book opens. Little by little I want to build up the character of the first in the mind of the second . . . until wife 2 is haunted day and night . . . a tragedy is looming very close and crash! bang! something happens . . . it’s not a ghost story.’

She started "sluggishly" and wrote a desperate apology to Gollancz: "The first 15,000 words I tore up in disgust and this literary miscarriage has cast me down rather."

Why did I never give the heroine a Christian name? The answer to the last question is simple: I could not think of one, and it became a challenge in technique, the easier because I was writing in the first person.

Gollancz expected her manuscript on their return to Britain in December but she wrote that she was "ashamed to tell you that progress is slow on the new novel...There is little likelihood of my bringing back a finished manuscript in December."

By the time she and Tommy sailed for home in mid-December, she had completed only a quarter of the novel and wrote to her mother just before leaving that ‘I haven’t been able to get going properly over here’.

On returning to Britain, du Maurier decided to spend Christmas away from her family to write the book in Cornwall. She needed to have a set routine before she could enjoy the peace of mind she needed to write.

In an interview with the Daily Express in 1938, she gave an overview of her working practice.

What does she read? Nothing very contemporary: the Brontë sisters, Anthony Trollope, and the poems of William Somerville. Her working day? From 10:00 am to 1:00 pm, then from 3:00 pm to 5:00 pm, every day except Sunday.

Tatiana de Rosnay. Manderley Forever

By the beginning of March she was writing at a tremendous pace and enjoying herself, though she was a little unsure of what she was producing. ‘It’s a bit on the gloomy side . . .’, she wrote to Victor Gollancz, ‘and the psychological side may not be understood.’

She described the plot as "a sinister tale about a woman who marries a widower... Psychological and rather macabre."

By April she had finished it and sent it to Victor – ‘here is the book . . . I’ve tried to get an atmosphere of suspense . . . the ending is a bit brief and a bit grim.’ It was, she warned, certainly too grim ‘to be a winner’.

I wondered if my publisher, Victor Gollancz, would think it stupid, overdone.

It was a great success.

Daphne never saw it as a romance, but a study of jealousy, and was irked that is was considered a love story. (Most of the critics stressed that Rebecca was ‘unashamed melodrama’ and harped on its ‘obvious popular appeal’. The Times commented that the ‘material is of the humblest . . . nothing in this is beyond the novelette’, and yet admitted there was ‘an atmosphere of terror which . . . makes it easy to overlook . . . the weaknesses’. The Sunday Times rated Rebecca ‘a grand story’ and ‘romance in the grand tradition’.)

Du Maurier gave the original notebook for writing the novel to her friends the Doubledays in New York where it was used to defend a plagiarism case, and many years later it was returned to her by their daughter, so we're able to see the plan for the first draft and compare it to the final manuscript.

Du Maurier gave herself the following creative directions in that notebook:

Atmosphere

Simplicity of style

Keep to the main theme

Characters few and well defined

Build it up little by little

She then outlined in paragraphs 26 chapters (the final novel has 27) The order of events is different, and the ending is not the same.

We can see that she imposed a structure on the contents after outlining the story.

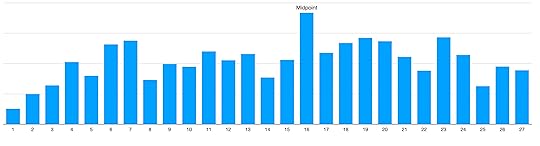

Here's how Daphne du Maurier's finished work looks in terms of chaptering of the narrative structure. Note the middle finger in terms of chapter length at the midpoint!

This virtuous story shape didn't happen by accident.

She rejigged the narrative effect for a crescendo effect towards midpoint doubling down on the falsehood that Rebecca was the 'right woman' for Maxim, ordering the events we sometimes describe at The Novelry as 'Nabokov's Rocks' to be thrown at the narrator by emotional size. The ball - which is the end of the child-woman and falls at midpoint at Chapter 16 in the finished manuscript - is at Chapter 8 in her notes, and the events leading up to it don't build tension in the same way.

By forceful reconstruction, du Maurier moved the downfall, the scene in which the child-woman mimics the 'right woman' to midpoint.

In the draft outline, there is a melancholy and depressive lull in the saggy middle of the plot where disgraced, alone, her husband (Henry in the draft outline) goes to London and the narrator finds life 'rather monotonous'. After this the truth about Rebecca's demise emerges without great incident when they are interrupted sitting quietly in the library together in Chapter 14. (The revelation doesn't emerge until past two-thirds of the storyline in the finished version.)

So a narrative structure a bit like a two-pole marquee with a flat roof is replaced with a wigwam, a single midpoint pole in the final manuscript.

Think about the midpoint as taking us from darkness or death into light or life, from confusion to comprehension towards clarity at the end of the story. That moment described as everything falling into place in a way that seems no other ending was possible.

In the notes for the first draft, Mrs Danvers barely has a mention. The last 10 chapters and the bulk of the outline are concerned with the evidence for the murder emerging and dwell at length on how unlikely it was that Rebecca would have taken her own life. The further revelation of the doctor attesting to the fact Rebecca didn't have much time to live (a contrivance to slightly excuse 'Henry's' murder of his first wife) is detailed at length. The ending is limp. After they discover she was ill anyway, they head back home to Manderley. Du Maurier makes a note:

'Perhaps Rebecca will have the last word yet.'

The ending implies they are run off the road.

By referring back to her five instructions, and revising her narrative structure, du Maurier lifted her novel from an exercise in prose to a classic story, and the rest is history.

Writers, don't be shy of reconstructing your novel, by reviewing the shape of the story. We're here to help.

In terms of the narrative prose technique, when adapting the novel for the screen, Daphne was struck by how difficult it was to keep both atmosphere and suspense without having the heroine’s interior monologues and without being able to describe the landscape. This is why first person is so commonly used in novels which rely on suspense. It's doubt which gives depth to suspense-driven fiction.

The novel is an art form which goes beyond the plot in which prose serves story as ruthlessly as Mrs Danvers served Rebecca.

Happy writing!

October 17, 2020

Rebecca - the Wrong Woman.

One of our 'Hero Books' for novelists writing their novels with The Novelry is Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, and many of us are looking forward to the new movie adaption which airs on Netflix on October 21st.

If you don't know the story, here's the premise:

Working as a lady's companion, the orphaned heroine of Rebecca learns her place. Life begins to look very bleak until, on a trip to the South of France, she meets Maxim de Winter, a handsome widower whose sudden proposal of marriage takes her by surprise. Whisked from glamorous Monte Carlo to his brooding estate, Manderley, on the Cornish Coast, the new Mrs de Winter finds Max a changed man. And the memory of his dead wife Rebecca is forever kept alive by the forbidding Mrs Danvers. Not since Jane Eyre has a heroine faced such difficulty with 'the other woman'.

Described by Sarah Waters as one of the most influential novels of all time, the famous opening line of Rebecca (1939) has wooed millions of readers. A bestseller which has never gone out of print. In 2017, W H Smith revealed Rebecca was the UK's favourite book of the past 25 years. In 2019, the BBC named it one of the most inspiring novels ever.

Here's the checklist for why this is a big story:

first-person 'avatar' for immersive experience (walk in my shoes)

life and death stakes (a murder)

magic - as in Manderly - the enchanted setting which provides another world of hallways and mirrors and super-natural beauty

a clearly drawn relentless antagonist in pursuit of our heroine (Danvers)

the ticking clock - a sense of running out of time

a love story fulfilled

draws upon a psychologically resonant archetypal story (Bluebeard)

the 'sacrifice' of the stakes (i.e Manderley)

the Five F's of story shape

a pleasing shape, a novel structure with a midpoint

the use of repetitious 'coding' per the suspense genre

(All of which we teach at The Novelry.)

Graduates of our Classic course will not be surprised to see the following:

an orphan main character (homeless and nameless)

a secondary world and a portal (the 'drive' - the word which dominates the first chapter)

a homely companion/guide (Jasper)

fairy tale comparisons (Cinderella meets Bluebeard)

The Perfect Novel?

The novel is hinged at its midpoint, folks, when our heroine enters adulthood rather unhappily and through the backdoor of embarrassment courtesy of a Mrs Danvers set up. She learns she can't mimic 'womanhood' as represented by Rebecca, and merely borrow the costume, she has to find her own way.

The novel uses the suspense method of story-telling which relies on repetition. Ad nauseam when you dissect it, but it creates a hypnotic effect on the reader. (Think how many of our first nursery rhymes require echoes and repeats.) The first half of the novel tells us over and over again - she will never be Rebecca. He loved Rebecca. The second half tells us over and over again - He did not love Rebecca.

But the repetitious first-person telling is not merely suspenseful story-telling, it mimics the negative inner voice of the young woman loaded with inadequacies and low self-esteem. It is the insecurity of a girl in a man's world; bottled.

The narrative is driven by a first-person rendition of a girl's paranoia; almost. (I'll come to Mrs Danvers!) Her paranoia, her unease and discomfort in a man-made world is understandable in the pre-WW2 era, but in our own age with online trolling and rampant insecurity especially among the young, we can hear the tiresome, inisistent and harmful voice of our own self-loathing.

Her only security as a homeless orphan, nameless to boot, is via the authority figure of landed gentry man of means, Maxim de Winter. But:

He did not belong to me at all, he belonged to Rebecca. He still thought about Rebecca. He would never love me because of Rebecca. She was in the house still, as Mrs Danvers had said; she was in that room in the west wing, she was in the library, in the morning-room, in the gallery above the hall. Even in the little flower-room, where her mackintosh still hung. And in the garden, and in the woods, and down in the stone cottage on the beach. Her footsteps sounded in the corridors, her scent lingered on the stairs. The servants obeyed her orders still, the food we ate was the food she liked. Her favourite flowers filled the rooms. Her clothes were in the wardrobes in her room, her brushes were on the table, her shoes beneath the chair, her nightdress on her bed. Rebecca was still mistress of Manderley. Rebecca was still Mrs de Winter.

Maurier, Daphne Du. Rebecca (p. 261).

The murder of another woman by such a man is presented to us as reasonable, given his standing and in the following circumstances of errant non-compliance by a woman. In his confession to his new wife, Maxim presents a portrait of 'the wrong woman', as a strong independent headstrong woman rather keen on the idea of open marriage. She is presented as unfaithful and sexually promiscuous. ‘Then she started on Frank, poor shy faithful Frank.’ She used bad language; ‘every filthy word in her particular vocabulary’. (Sounds to us in 2020 like a quiet episode for a daytime TV show.)

But Rebecca's real crime was to threaten to cuckold Maxim, and produce a 'bastard' heir, trouncing the system of inheritance (note Maxim owns Manderley not older sister Beatrice), thus cheating the patriarchy. No man could accept such a rebellion. It's treachery, civil war! Unable to face the social indignity of divorce, he killed her.

But being a good egg, he feels a little bad about it. He asks our nameless heroine if she shares his shame for his crimes.

The short answer is no.

I did not say anything. I held his hands against my heart. I did not care about his shame. None of the things that he had told me mattered to me at all. I clung to one thing only, and repeated it to myself, over and over again. Maxim did not love Rebecca. He had never loved her, never, never. They had never known one moment’s happiness together. Maxim was talking and I listened to him, but his words meant nothing to me. I did not really care.

Maurier, Daphne Du. Rebecca (p. 306).

She's bloody thrilled to bits! Hoorah! Ding dong the witch is dead! The remainder of the book further to this confession at two-thirds, repeats her gloating that Rebecca is dead. He didn't love Rebecca, he loves her!

Rebecca is such a mensch, she smiles when he shoots her. Little man Maxim disposes of her body with a lot of inconvenience to himself and it puts him out of sorts for his holiday in the South of France.

I hear you, the novel's still great.

The liberal reader can set aside the reactionary bent of the tale and enjoy it. Ouch! Why?

The writing, the setting, the suspense, yes, but above all else - DANVERS.

It's the charisma of this ghastly sentinel that gives this novel its wonderful light and shade. When she is overcome by the new alliance of Maxim and the second wife, the book's far less interesting. Even Manderley seems just a house when the spectral Mrs Danvers no longer roams its corridors, and they decide to quit it and head back to France. After all, it's by Mrs Danvers agency, her absolute, devotion to Rebecca, that Rebecca is able to haunt the place. When Danvers gives up the ghost, both she and Rebecca are gone from the story and its all far more 'ordinary'.

Every woman needs a Danvers! You see the shit that goes down when two women collude? Poor od Maxim, poor old Frank. The menfolk are quite undone by the loyalty between these two women. But don't worry, it won't happen again. Drawing on the lessons of Bluebeard, Maxim chooses for his second wife a woman who has no alliances, no female friends or female relatives. And Frank remains an inveterate bachelor.

En route to proper devotion to the patriarchy, our heroine has learnt a thing or two about what it means to be a woman and the dividing line between pretty and beautiful, useful and threatening, a border vital to the maintenance of power relations.

‘It’s very big, isn’t it?’ I said, too brightly, too forced, a school-girl still.

In the first half of the book, she is referred to as a girl, a school-girl, and a parlour-maid. Now come on ladies, that won't do! You are not to be as children!

The Woman as a Useless Child.

Maxim berates her as a mother might, instructing her daughter:

‘I wish,’ I said savagely, still mindful of his laugh and throwing discretion to the wind, ‘I wish I was a woman of about thirty-six dressed in black satin with a string of pearls.’ ‘You would not be in this car with me if you were,’ he said; ‘and stop biting those nails, they are ugly enough already.’ (...)

‘I told you not to go on those rocks, and now you are grumbling because you are tired.’ (...)

‘If you wear that grubby skirt when you call on her I don’t suppose she does,’ said Maxim. (...)

‘I can’t help being shy.’ ‘I know you can’t, sweetheart. But you don’t make an effort to conquer it.’ (...)

'I didn’t mean it. Really, Maxim, I didn’t. Please believe me.’ ‘It was not a particularly attractive thing to say, was it?’ he said. ‘No,’ I said. ‘No, it was rude, hateful.’ (...)

‘You look like a little criminal,’ he said, ‘what is it?’ ‘Nothing,’ I said quickly, ‘I wasn’t doing anything.’ (...)

'I wished he would not always treat me as a child, rather spoilt, rather irresponsible, irresponsible, someone to be petted from time to time when the mood came upon him but more often forgotten, more often patted on the shoulder and told to run away and play. I wished something would happen to make me look wiser, more mature. Was it always going to be like this? He away ahead of me, with his own moods that I did not share, his secret troubles that I did not know? Would we never be together, he a man and I a woman, standing shoulder to shoulder, hand in hand, with no gulf between us? I did not want to be a child. I wanted to be his wife, his mother. I wanted to be old.'

The Wrong Woman.

Careful, there is the wrong woman and the right woman. They can be easily confused. Here's what a woman looks like:

'Someone whose quick eyes saw to the comfort of her guests, who gave an order over her shoulder to a servant, someone who was never awkward, never without grace, who when she danced left a stab of perfume in the air like a white azalea.'

Maurier, Daphne Du. Rebecca (p. 141).

The house in dreams and in fiction is a common metaphor for the self, with unexplored rooms and light sociable spaces with hidden closed spaces. Thus we are drawn through Manderley on this bildungsroman which shows the development of a girl to adulthood, towards the dark, dark space occupied by the wrong woman. It's heady stuff!

Du Maurier, who admitted to her devoted and loyal former nanny in letters that she harboured 'Venetian' tendencies (code for lesbian), provides an almost erotic scene as Danvers shows her Rebecca's room as if it was still inhabited. (Our heroine has bitten her nails with worry about the servants laughing over her cheap undergarments.)

Down a long dark corridor she goes...to find the horror of 'the wrong woman':

I got up from the stool and went and touched the dressing-gown on the chair. I picked up the slippers and held them in my hand. I was aware of a growing sense of horror, of horror turning to despair. I touched the quilt on the bed, traced with my fingers the monogram on the nightdress case, R de W, interwoven and interlaced. (...)

‘Now you are here, let me show you everything,’ she said, her voice ingratiating and sweet as honey, horrible, false. ‘I know you want to see it all, you’ve wanted to for a long time, and you were too shy to ask. It’s a lovely room, isn’t it? The loveliest room you have ever seen.’

For Joseph Conrad, the horror in The Heart of Darkness is what white man can do in the name of territory, here the horror is what the wrong woman can do to white man. Danvers shows her the tools of 'beauty' that a minx could use to deceive a respected landowner.

Mr de Winter used to brush it for her then. I’ve come into this room time and time again and seen him, in his shirt sleeves, with the two brushes in his hand. “Harder, Max, harder,” she would say, laughing up at him, and he would do as she told him.

Danvers shows her Rebecca's furs, then her underwear.

I would always know when she had been before me in a room. There would be a little whiff of her scent in the room. These are her underclothes, in this drawer.

The scene is one of fearful eroticism, the wrong woman unfettered;

‘It’s not only this room,’ she said. ‘It’s in many rooms in the house. In the morning-room, in the hall, even in the little flower-room. I feel her everywhere. You do too, don’t you?’

Go back, dear girl, go back! Maxim - the parental figure - warns her:

'When you were a little girl, were you ever forbidden to read certain books, and did your father put those books under lock and key?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Well, then. A husband is not so very different from a father after all. There is a certain type of knowledge I prefer you not to have. It’s better kept under lock and key. So that’s that. And now eat up your peaches, and don’t ask me any more questions, or I shall put you in the corner.’

But the silly girl gets it all wrong and dolls herself up as Rebecca for the party, appearing in the costume of the last wrong woman. And little man Maxim is quite cross!

So what the devil is the right woman?

The Right Woman.

It's quite simple; she's useful. Du Maurier reduces it to one quality. A good wife takes command of the servants, the lower orders. She brokers her husband's authority. After her disgrace, once Maxim is in a tricky spot having shot the bad woman, they form a working alliance, and it's at this part of the novel our heroine at last takes the reins of the household.

The first half of the novel includes numerous hints she should do so from Maxim and his sister Beatrice. But she's too nervous. Come on, dear, Rebecca almost whipped a horse to death! Channel your inner brute.

When she breaks an ornament, she conceals it as a guest might.

‘Fancy not getting hold of her when you broke the thing and saying,“Here, Mrs Danvers, get this mended.”'

But in the second half, after she gets a clear indication of what the wrong woman looks like and is rebuked at the midpoint, she muscles up, and takes control of Mrs Danvers.

‘You’d better stop this, Mrs Danvers,’ I said; ‘you better go to your room.’ (...)

She went to the mantelpiece and took the vases. ‘Don’t let it happen again,’ I said. (...)

‘I’m afraid it does not concern me very much what Mrs de Winter used to do,’ I said. ‘I am Mrs de Winter now, you know. And if I choose to send a message by Robert I shall do so.’ (...)

'She can’t frighten me any more, I thought. She has lost her power with Rebecca. Whatever she said or did now it could not matter to me or hurt me. I knew she was my enemy and I did not mind.' (...)

Du Maurier, the Apologist?

Not so fast! Poor old Daphne was in thrall to her capricious, womanising, stage actor father and was preoccupied with negotiating the power relations of the male-female world. Her family occupied a grand London home with servants, but she preferred the more modest home of her grandparents, unstaffed, where the couple worked together.

She wrote to Tod (her dear Danny Danvers equivalent - the nanny)

‘The future’, she announced to Tod, ‘is always such a complete blank. There is nothing ahead that lures me terribly . . . If only I was a man.’

'I only hope I haven’t got Venetian tendencies.’

As Mrs Danvers puts it in Chapter 18, referring to Rebecca:

'She had all the courage and spirit of a boy, had my Mrs de Winter. She ought to have been a boy, I often told her that.'

Margeret Forster, in her biography of Daphne du Maurier, describes the years of the 1920s which du Maurier spent in France feeling insecure, trying to find herself as a writer.

'The short stories Daphne wrote in Brittany, and for the next three years, all have one striking thing in common: the male characters are thoroughly unpleasant. They are bullies, seducers and cheats. The women, in contrast, are pitifully weak creatures, who are endlessly dominated and betrayed, never capable of saving themselves and having only the energy just to survive. (...) The tone of all the stories is cynical and there is an obsession with the life of the working-class girl, often a prostitute. The thread that binds all the early stories together is one of total disillusionment with the relationship between men and women – they are bleak, bitter and sad. (...)

In all the stories, eleven of which were finished by the spring of 1928, there is no trace of the charmed life Daphne led. Her view of the world is dark and dismal, and the overriding influence is clearly that of her father’s amorous relationships. None of the men in these stories is even remotely like Gerald du Maurier – none has any charm, none is witty, none talented or attractive – but in all of them is the unmistakable flavour of what Daphne found it so hard to accept: all men were like her beloved father, unfaithful and not what they seemed. No other topic interested her so much as the relationship between men and women. What she was doing was emphasizing over and over again her own pessimism as she surveyed what she believed to be the truth about these relationships. She concentrated on the interchanges between couples, often not bothering to give either man or woman a name...'

Margaret Forster: Du Maurier.

In Britanny, she learnt to sail, enjoying the command of small boats out at sea, and carried on an affair with cousin Geoffrey. Then, her family bought a second home in Cornwall, and Du Maurier found it easier to write at Ferryside near Fowey. It was there she became fascinated with the house Menabilly which was to become Manderley.

'Literature needed practice, and she was not practising. She wished she could stay by herself at Ferryside and work all winter – which she swore she would do – but she was obliged to return to London. There was, however, a chink of light: her parents said that if she could sell her stories and earn enough to keep herself, then she would be allowed to stay at Ferryside. Never having earned a penny in her life, nor having been required to, it was a rather unreal condition, but one Daphne accepted at once. She did not want to be dependent financially or in any other way on her parents – it would fill her with joy to have her own money and this was the incentive she needed.

Margaret Forster: Du Maurier.

Her relationship with her mother - Muriel - was poor, until her father Gerald died. (My writers will have come across Maureen Murdock's work The Heroine's Journey - which explains why women writers kill their mothers in order for the story to start!) Gerald died in 1934.

She felt close to her (mother) for the first time, even physically close, able to embrace her as she never had done before, and she felt instantly protective. There had never, or so she had thought, been any role for her in her mother’s life, but now that she could see how much support was going to be needed she was eager to acknowledge her new responsibilities. A kind of love for her mother touched her for the first time.

Margaret Forster: Daphne Du Maurier

After his death, du Maurier came into her own penning notable successes - a biography of her father Gerald: A Portrait (1934), Jamaica Inn (1936), The du Mauriers (1937).

Many of the elements for Rebecca were in place before she began writing the novel in 1937. The absence of place in her short stories was remedied, and she had the confidence - and perspective - to draw on the nail-biting preoccupations of her youth to drive the tension of the fearful narrative.

The wrong woman, the strong woman, Rebecca, the inner self, the spirit of defiance and independence was linked to the act of writing itself. Writing was a 'way out' of dependence or institutionalised inferiority. No wonder then, that when we first meet Rebecca in the novel, in the early chapters, the letters of the name of this woman (in contrast to the nameless girl narrator) are spelt out to us in the act of writing.

I picked up the book again, and this time it opened at the title-page, and I read the dedication. ‘Max – from Rebecca. 17 May’, written in a curious slanting hand. A little blob of ink marred the white page opposite, as though the writer, in impatience, had shaken her pen to make the ink flow freely. And then as it bubbled through the nib, it came a little thick, so that the name Rebecca stood out black and strong, the tall and sloping R dwarfing the other letters. (...)

I had a book that she had taken in her hands, and I could see her turning to that first white page, smiling as she wrote, and shaking the bent nib. (...)

When Max proposes, she removes the title-page furtively in another room and burns it.

On her first day at the marital home of Manderley, she sits at Rebecca's writing desk and marvels at its 'lovely' 'rich' colours. It is beautiful and yet also 'business-like'.

I noticed for the first time how cramped and unformed was my own handwriting; without individuality, without style, uneducated even, the writing of an indifferent pupil taught in a second-rate school.

Rebecca's act of writing in her own hand, her own words, and using her name, occupies our narrator as she explores the halls and corridors of her developing psyche.

Her voice, echoing through the house, and down the garden, careless and familiar like the writing in the book.

Here in the act of writing, du Maurier, seems to sigh in her novel, is a way to be all sorts of women, and also un-gendered, un-bodied and free.

That bold, slanting hand, stabbing the white paper, the symbol of herself, so certain, so assured.

The novel provides no lessons on the possibility of rebellion for women who form alliances with each other, the male order is too well-entrenched for that. The way out of it is lonely and secretive, found behind the veil of fiction.

Don't mistake performance for promulgation.

Because du Maurier is showing us the status quo does not mean she's an advocate or champion for it. She is depicting it, with heavy strokes; light and shade. Beyond the novel as entertainment, as Graham Greene put it, there is also the novel as performance.

By performing the conventions we don't endorse them, often quite the reverse, sometimes we lampoon them. The airing of dirty laundry is worthy in its own right.

You don’t have a debt to politics you have a debt to the truth.

The stage in this novel is the 'stakes' itself. The stakes character in Rebecca is Manderley. It's the return there that provides the story. Finally, they must choose between the house, the estate, the inheritance and the possibility of love or a romantic union. They choose the latter.

The prize or lure for the homeless, nameless girl was the house of Manderley - as firmly articulated by Mrs Van Hopper. It is also the site of what she fears, the place that still houses the wrong woman, who risked it. If we flip the stakes, or the prize, we find fear wriggling underneath. Nothing valued, in any era, against any socio-political backdrop, is without its cost.

Against the ancient and enduring backdrop of women who stand by their men and protect the bricks and mortar, no wonder Daphne picked up her pen. Something has to be sacrificed in a story, and Daphne discarded Manderley for the idyll of romantic love.

In next week's blog, we'll be looking at how Daphne du Maurier restructured the work to create a Classic.

Happy writing,

October 10, 2020

Meet The Agent.

We are delighted to announce the addition of The Soho Agency to our roster of literary agencies to whom we pitch our authors' finished novels. (Read more about The Soho Agency and see our full list here.)

From the Desk of Marina de Pass, Literary Agent.

My Career in Books...

I remember vividly the two experiences I had with career advisors in my life – one just before I left school, the other at university. Both involved a lot of leaflets, an advisor who had no idea who I was as a person, but who was sure that I should trust the dreaded aptitude test that would absolutely tell me what I should do with my life. Both times the test revealed I was most suited to a career as one of the following: lawyer, accountant or investment manager. Three very respectable and accomplished careers – and yet I was horrified. I worked for a couple of weeks doing research for an investment management firm – the people were lovely, the work actually quite interesting for an internship, yet it left me cold. How could I commit my life to a career when I spent all my free time stitching and unpicking stories in my mind? There were the far-fetched scenarios that would play out in my imagination – what if I were to get stuck in the lift with the CEO, he has an asthma attack and I save his life? There were the days I couldn’t focus on my work because the book or film I was currently engrossed in had taken a turn the night before and I was furious – how dare the writer kill off that character who I loved so much? The two detectives were meant to be together – why are they not together? You get the picture. I haven’t changed much; I spend my life unpicking the TV series I’m watching or imagining sequels for my favourite novels. I’m always asking questions about why something works, whether it be books, film, TV, theatre. Do I love this really mediocre programme because the two characters on screen have great chemistry? Is it because, despite the miserable setting, the dialogue feels really authentic?

A client of mine recently made the excellent point that when you are young no one properly explains to you that there are jobs for everything – it is perfectly possible to make the thing you love part of your every day. Just at the point where I thought a miserable life of spreadsheets lay ahead of me, a chance work experience placement in children’s publishing opened my eyes to what a career working with books could look like. Then I was lucky enough to find what was, at the time, the Holy Grail: a paid internship in publishing. For six months I worked with the team at Avon, a commercial fiction imprint at HarperCollins. It was invaluable schooling – the team at Avon taught me about books as a business; they taught me about commercial potential, the importance of plot and the power of story, and what that looks like broken down. It was a small, deeply dynamic team, who took me under their wing and I owe them a great deal. They were instrumental in helping me secure my next job in the editorial team at Sphere (Little, Brown UK), which taught me a whole host of other things. I went on intense copyediting and proofreading courses, and had an amazing mentor from whom I learned all about the editorial process. I went to acquisition and cover meetings; I learned about what editors have to consider when acquiring books. I met and collaborated with all the different teams and departments that make up a publishing house, all of whom have a part to play in the publication of a book. And in the process of all of this, I discovered that – most of all – I didn’t want to work on the publisher’s side. My interest was always instinctively in line with the author’s; I wanted to work close-up with these brilliant, interesting storytellers, and help them build the kind of writing careers that they wanted to have.

My heart is in fiction. I love that ah-ha moment you get when reading novels, when an author manages to articulate something you’ve been feeling, but don’t know how to express. I love unforgettable characters, the chemistry that sizzles on the page – that twist you don’t see coming. I think there is a story for everyone – stories that depict real life experience, stories as an escape, stories that teach you something about the world (often something you didn’t know you needed to learn), and stories that transport you somewhere you haven’t been yet (and wow, haven’t we needed these this year). I believe deeply that words have power – we need them right now and we are going to need them in the times ahead.

I have worked at The Soho Agency, a literary and talent agency based in central London, for four years now. Every day is a little different and it is blissful. It is a huge privilege to work with so many talented clients and colleagues – their imagination and creativity surprise and inspire me every day. It’s great fun, too, because of the sheer variety of projects going on at the agency. We have agents working in all areas – from serious non-fiction, business books and memoir to crime, thrillers, historical fiction, rom-coms and more. We work with our authors globally, in North America, in translation, in film and television – I can honestly say there is never a dull day.

As with other industries, the last couple of months have been complicated and it has been an unsettling time for everyone in the business – authors, agents, publishers, booksellers, readers. But we have proved that we are adaptable – publishers quickly shifted their marketing focus to digital and there have been some amazing campaigns. People are still reading; bookshops have found new and enticing ways to sell books. It’s certainly not all doom and gloom – we continue to take on new clients; deals are being done; publishers are buying books; bookshops are open again . . . Yes, I look forward to the day that we can walk away from our webcams and welcome clients back into the office for real-life meetings, which does sometimes feel like a very exotic, faraway thought. But we are getting there; every day looks a little brighter.

We are very much open for business and are on the lookout for new writers to champion. Personally, I am building a list of authors who are writing upmarket commercial and book-club fiction and am actively looking for new writers to work with. There are lots of things on my wish-list at the moment: I’m always after love stories; I have been thinking recently that I’d love to read a smart, witty rom-com set in the UK; I’d also love to see more female-lead historical fiction, with a mythical or magical edge (although no straight fantasy or sci-fi for me please – as these are not my area of expertise). I am also always after upmarket thrillers and crime. Ultimately, I am looking for great writing, interesting settings and set-ups, great characters and hooks and if a book takes a turn I don’t see coming, even better!

I think trends in publishing can be misleading and sometimes feel limiting to writers. Earlier this year, there were lots of whispers about how no one wanted to read dystopian fiction, because we were living in times that felt dystopian enough already. Then everyone said, feel-good fiction was the thing (I should say that I always think feel-good fiction is the thing!) Everything changes so quickly, and regardless of what is ‘hot’ now, I would never advise aspiring writers to be held captive by trends. I work closely with Sophie Kinsella, who is often asked in interviews what advice she would give to aspiring writers. She says that you should write the book you’d like to read. I love this advice, because sometimes that book is a variation of something that’s already on the shelves, just told in a new way, and sometimes it’s something completely new. Every writer has a different, distinct voice and way of telling a story – your novel comes from you and how you see the world. Isn’t that interesting, rare and exciting in itself? If we’ve learned anything this year, it’s that life as we know it can change in an instant. Most editors I know would admit that the books that they fall hard for are books they didn’t know they were looking for. That’s the same with us agents, too.

Regardless of genre, if your novel comes from the heart, if it’s a story that you think needs to be told – that will shine through on the page.

There isn’t a formula that will ensure you get published – if there was, everyone would do it. As you are already a member of The Novelry, you have certainly decided you are serious about this writing business – good for you.

Along with their talent and imagination, the writers we work with are some of the hardest workers out there – committed and disciplined. The hours are long, the work is solitary and you might not become a millionaire at the end of it all. However, I believe that when you find an agent who will champion you and your writing, and be on your team, it lightens the load. They can help turn your manuscript into a career in books. Above all, it can be great, great fun.

All of us at The Soho Agency are absolutely thrilled to be linking up with The Novelry and we hope you’ll think of us when your novel is ready to submit.

Happy writing!

October 3, 2020

Ruth Ware - Writing Fiction in Lockdown.

With our thanks to Ruth who will be joining us for a Guest Author Session this month.

Ruth Ware is the author of The Woman in Cabin 10 and The Turn of the Key. Her new novel, One by One, is out this autumn from Harvill Secker.

From the Desk of Ruth Ware.

It's a lock-in.

I've always loved locked room mysteries. I love reading them – I find a really clever puzzle with finite possible solutions is somehow that bit more satisfying to solve than a novel where anyone could have wandered in off the street and stabbed their victim.

I also love writing them, as the fact that I keep returning to the locked room structure attests. There's something about setting yourself a challenge – a small cast of characters, a confined setting, a strictly limited set of options in terms of suspects, victims and murder weapons – and trying to be as creative as possible within those parameters that really sets my imagination sparking.

And in fact the first grown-up crime story I can ever remember encountering was a locked room mystery – Arthur Conan Doyle's The Speckled Band, in which Holmes is confronted with the seemingly intractable problem of a healthy young woman who dies in her own locked bedroom, the only clue her strangled last words, “it was the speckled band!” So maybe in some ways, the locked room imprinted itself on me as the quintessential form of the detective story.

Regardless, it was a format I returned to again in my new novel One by One, which takes place in an isolated ski chalet in the aftermath of an avalanche. Guests and staff are confined to what was once an enviable location but is now a slowly cooling deathtrap – and one by one, people begin to die.

This time however, there was a difference. I wrote the novel in 2019, but I edited it in early 2020 – just as we were entering lockdown.

Like many others, I found I could not write during lockdown. There was something about the enforced loneliness but also the enforced company – the house was full of my family, but at the same time I was deprived of many of my usual sources of inspiration: overheard conversations, people-watching, strange encounters. There was no room for human interest stories in the news or on twitter, only the hypnotically awful unfurling of pages of graphs and stats and figures.

Writing, for me anyway, requires a strange dance between the two halves of my brain. When I'm actually putting words on the page, it's my conscious mind that's in charge, very deliberately picking and choosing from options and thinking through different solutions. However, in between times, it's my subconscious that takes over, solving plot problems while I'm out walking, coming up with characters while I'm asleep. Often my most productive sessions are after a long period of enforced non-writing, I think because all that time my subconscious brain has been at work, figuring stuff out, coming up with twists, and when I sit down at the desk it's all there ready and waiting.

Now, in lockdown, something seemed to be broken. I don't know which half was at fault – whether it was my subconscious brain which was now awash with alarm and dread, or my conscious mind that was too distracted with homeschooling and the lack of loo roll on the shelves. Either way, some vital link in the chain of back-and-forth seemed to be broken, and when I sat down to work, I found the words weren't there.

Editing, however, was luckily a different story, and in between Zoom meetings, BBC Bitesize and doom-scrolling on Twitter, I found I was able to edit. In fact having something to wrestle with – a dodgy sentence structure, a plot issue, a word that didn't mean the same in British English as in US – all of that was a welcome distraction that, somehow, my mind was able to cope with.

As the edits wore on, into copy edits, and proof, I re-read the book again and again and somewhat to my surprise, I found that I loved escaping reality into my characters' snow-bound world. It seems the perverse, to want to escape one kind of lockdown by immersing yourself in another, but for some reason, it was an escape, and I found myself sympathising with my characters' predicament in a new and personal way. Like the rest of us, they were confined to a single residence, rubbing their companions up the wrong way, reacting to stressful situations with irritability and short tempers. Fortunately, however, I did not have to contend with a murderer and an avalanche.

It may seem strangely contradictory to respond to a stressful situation by escaping into a fictional world where the stakes are even higher – but in adversity, my characters generally find themselves to be smarter, more resourceful and more courageous than they knew – and maybe that was what I needed to hear. I found myself reflecting on how Agatha Christie remained one of the most popular novelists throughout World War 2. People read her murder mysteries to escape the daily reality of death and war – perhaps reassured by how much worse things really could be, and how Poirot seemed to set things to rights nonetheless.

I don't have a detective in my novel to wave a magic wand and produce justice from a hat. And likewise, back in the real world, there don't seem to be any easy solutions either. But somehow, my imagination has started ticking again. And as we head into what's likely to be a difficult winter one way or another, I'm confident that even if I can't leave the house, I will at least be able to escape.

September 26, 2020

Poetry for Novelists.

Sometimes I wonder, do you, what people who don't write do with their thoughts? And what they plan to leave behind them too.

'Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?' Mary Oliver.

I started writing by putting down thoughts in poem form, and I think many writers start that way. We forget over time that here was the spark, and as our novels develop, it's good to be reminded of the ache of the thing, or the mischief of it; the pilot light. In this week's blog, our tutor Emylia Hall serves up some light for your darker days.

From the desk of Emylia Hall.

When I’m in the middle of a sprawling novel draft, I turn to poetry. You’ll find me with my head bent over my collections just like a beachcomber looks for treasure, hoping for a secret from the deep. Maybe it’s because there’s something particularly possessable about a poem: a few spare stanzas glint with the kind of truth that you can hold in the palm of your hand; a feeling of verisimilitude hat’s more certain than the infinitesimal, disquieting sprawl of a partially written novel.

The brevity of poetry appeals to me too. The more we write, the more we try to fail better, the more familiar we become with our own foibles (and yes, perhaps that is a generous way of putting it, but we’ve got to be kind to ourselves: tough, but kind). My own foibles? Rambling. Reams of description. If I can say it in three sentences, why say it in just the one? I know this now and I catch it where I can. But my first drafts? Oh, they’re flabby. Very flabby. So, in the way that opposites attract, I admire the compactness of verse.

In fact, I think there’s much that novelists can learn from the form, and not just in the ‘make every word count’ stakes. Most of my favourite poems have a lesson in them that I can apply to my fiction writing, some element that reinforces an aspect of process and craft. Let me share some poetical gems with you – and the writerly wisdom they contain; I recommend hitting all the links and reading the works in full.

For attitude and motivation:

There’s no better poem with which to start my writing day than Michèle Roberts’ sumptuous Christina Rossetti Scribbles A Memo To A Young Friend: it’s all about writing as an act of pleasure, something to revel in – and amen to that.

‘Leap out of bed, let greed for words begin

breakfast on bread and honey, butter spread thick as sin

let pleasure on the tongue release the angel within.’

We know we’ve got to embrace our inner darkness when we write, and in Roberts’ poem the co-existence of tenderness and severity is perfectly articulated:

‘drape your cat around your shoulders and stroke her till she’s purred

the part of yourself that is brindled and furred

and can hiss, and pounce, and disembowel a bird.’

And the last stanza? Well, it gives me goosebumps:

‘Let your skirts flare out, gold petticoats bright

As a rage of seraphs, jostling tight

As a rustle of sunflowers that burn with light

Be brave as these – sit down and write.’

Because bravery is required. Writing a novel can feel like screaming into the void a lot of the time (though of course members of The Noverly have a rather different experience from many here: the embrace is real). It’s making something out of nothing, and that always takes guts.

For the joy of language:

According to dictionary.com, an average 20-year-old native English speaker typically knows 42,000 words – though probably only uses 20,000 of them actively. As a word geek, flicking through a thesaurus is right up there for me in the thrill stakes. Language is ours to make of what we will, and that should be fun. In Fern Hill, Dylan Thomas takes delicious liberties and the effect feels free, and yet precise.

‘And nightly under the simple stars

As I rode to sleep the owls were bearing the farm away

All the moon long I heard, blessed among stables, the nightjars

Flying with the ricks, and the horses

Flashing into the dark.’

The extent to which we take liberties as a novelist will always depend on our ambitions for the work, the genre that we’re writing in, and our intended audience. But I’d argue that an energetic and joyful approach to language should always fuel our writing, whether we’re about commercial women’s romance or experimental literary dystopias.

For the role of descriptive narration alongside dialogue:

Tess Gallagher’s The Hug is a wonderful testament to the potency of nonverbal communication and a reminder that interpersonal exchanges are not all about dialogue. Descriptive narration has an important role to play, but sometimes we can be guilty of just dropping in mention of gestures, postures, and body language, in order to break things up. If a moment really matters, don’t be afraid to go deep with it. Consider this:

‘I put my head into his chest and snuggle

I lean into him. I lean my blood and my wishes

into him. He stands for it. This is his

and he’s starting to give it back so well that I know he’s

getting it. This hug. So truly, so tenderly

we stop having arms and I don’t know if

my lover has walked away or what, or

if the woman is still reading the poem, or the houses –

what about them? – the houses.’

Such devotion to describing the intricacy of a moment could be tedious if we were at it all the time, but when we really want the reader to feel that hug? Go for it, Gallagher style.

On a side-note, The Hug contains the line ‘when you hug someone you want it/ to be a masterpiece of connection’ and that’s not a bad mantra for any writer’s endeavour; we’re not all going to be writing veritable masterpieces, but masterpieces of connection? That’s a goal for everyone.

For character:

Phenomenal Woman by Maya Angelou has much to teach fiction writers on the subject of character. Who doesn’t want to know more about the titular phenomenal woman after reading lines such as these?

‘I walk into a room

just as cool as you please,

and to a man,

the fellows stand or

fall down on their knees.

Then they swarm around me,

a hive of honey bees.

I say,

it’s the fire in my eyes,

and the flash of my teeth,

the swing in my waist,

and the joy in my feet.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.’

It’s an ‘I want what she’s having’ moment: our characters should leap from the page – fire in their eyes and joy in their feet. Even if they’re primarily being let loose to skulk and moan, make sure they do it with feeling.

Phenomenal Woman also teaches us to give our characters a distinctive voice. A useful exercise to do away from the page is to spend some time writing as each member of your cast – diary entries or letters are particularly good here – allowing them free rein to express themselves before you start manipulating them for your own ends. I find this particularly productive when I need to cement a character’s emotional state. It’s all too easy to let scenes run on, without remembering that every character is moving sequentially, and is affected by the events of the last scene, and the last, and the last. How do they feel? What’s on their mind? Stepping away from your novel and hanging out with your characters on a one-on-one basis is as valuable as you’re willing to make it.

For ambition and desire:

I think it’s important for us to understand why we’re writing, and what we want our words to be for: there’s no right answer to this – it only has to be honest. Understanding why you’re in this game will help you manage your relationship with your work, refine your ambition, and decide what time and sacrifice you need to apply to the pursuit of it. Here, I turn to the marvellous Blk Girl Art by Jamila Woods.

‘I won’t write poems unless they are an instruction manual, a bus

card, warm shea butter on elbows, water, a finger massage to the scalp,

a broomstick sometimes used for cleaning and sometimes

to soar.’

Hearing Woods’ reasons for her writing, helps me know my own.

In a lot of poetry there’s a line that remains a bit of a mystery, and the accompanying sense that the poem belongs, above all, to the poet. I think there’s a lesson in this too, that you have to write first and foremost for yourself. I’m undoubtedly romanticising the field, but I reckon there aren’t many poets who eye the market, jump aboard bandwagons, and train a hungry eye on the bestseller list. Not that there’s anything wrong with such things, but if you’re in it for authentic reasons, then you’ll be enriched by your writing, whatever your concept of success.

For inspiration:

Where do ideas come from? So many of us are fascinated in this question because for all that our thoughts can be rationally routed, mapped, tracked back, there’s still an ethereal aspect to the process. Sure, you might have seen a news item in a newspaper and taken it wholesale as your set-up, but you’ve still got your work cut out to make a novel out of it; you’re still going to have to commune with the great wide open at some point. Here, Seamus Heaney’s Postscript says it for me:

‘You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’

Doesn’t this speak to writer and reader alike? It’s how we might experience the coming of ideas but, also, it’s the effect that we hope our writing might have on ourselves and others.

‘Catch the heart off guard and blow it open’? Yes, please.

Oh, and another thing about poetry for novel writers? Verse defies direct comparison with prose, therefore we’re unlikely to be so completely intimidated by a poem’s brilliance that we end up feeling glum about our own work-in-progress. Reading poetry is always safe ground; a pure experience, untainted by ego. And therefore, the perfect springboard for our own creativity.

Coming soon at The Novelry, a suspense class on Tuesday at The Story Clinic for members.

The formula.

And a special online Home Retreat Week with evening readings from members.

Enjoy on our Catch Up TV recent sessions with fabulous bestselling authors sharing the tricks of the trade.

Join us! @thenovelry.com.

September 19, 2020

Close Encounters - The Narrative Point of View.

From the Desk of Katie Khan.

There are many choices to make when you begin writing a novel. Some you can choose from a starter menu - present or past tense, first person or third? - while others you will discover off-menu along the way, making what may feel at the time like a mistake. Personally, I’m fearful of going off-menu after learning, at the tender age of nine, that frogs taste like chicken, but with a lot more tiny bones.

Fiction is more forgiving. The brilliant thing about making mistakes in novel writing is you can fix many of them in a later draft. If you read your novel like a critical reader, rather than as the writer, and you’re willing to do the work, you can absolutely salvage and sharply improve the book.

Writing is rewriting.

But let’s talk about the menu because choosing wisely at the outset can save pain later. The first thing I like to do, when I have a plot and story in mind and ready to be written, is to audition the voice.

First, I pick my narrator. Who is the most interesting person to tell this story? Who is seemingly the worst-placed person to be the hero of this story? The police chief who’s terrified of water must catch a shark terrorising his town. (Jaws.) A tiny hobbit who has never left the Shire must travel across the world to save it. (The Lord of the Rings.) The ‘unlikely heroes’ often make for the most exciting protagonists, because they have the most potential for change. They have a major flaw to overcome; they start the novel on the back foot. If you are very lucky, you will select the right lead character in your first draft. But sometimes you won’t, and that’s okay. Sometimes you’ll only learn by writing out the entire thing that a character hiding in the wings was the most interesting person all along. This has happened to me recently. It’s fine; these things happen. Don’t beat yourself up – instead, embrace the fact you found the exciting character, and your next draft will set this story world alight. We’re looking for chicken, not frogs.

The next thing I like to do is to play around with style, writing a section in first-person (‘I walk into a bar’), then a section in third-person (‘Katie walks into a bar, then remembers we’re in a pandemic, so she leaves again’). Which do I prefer? Which feels inherently closer to what I’m trying to pull off? (Which is more popular for the genre I’m writing in?) Which gives the voice some breath and air, and lifts the prose into sounding like – well, a published book? This decision will have a huge effect on the overall feel of the project. It’s likely the biggest choice on the menu.

First or Third?

If you’re writing in first person you’ve probably chosen it because it’s intimate. It’s also familiar. It’s how we move through the world: we write text messages, emails and letters in first. ‘Hi mum, I love you.’ Blogs, newspaper columns and opinion journalism are presented in first person, too. It’s comfortable, personal, and easy. Technically, debut authors are less likely to veer towards ‘head-hopping’ and accidental PoV switches when the perspective is fixed inside one character, which makes it a straightforward single line through a story. Clean and precise.

In recent years, first-person fiction has become increasingly prevalent and successful. It dominates the commercial fiction market. I’m struggling to think of a single novel I’ve read that will be published next year, which was sold to publishers with enormous fanfare and optioned for film in spectacular deals, that isn’t written in first person. Yikes! (I’ve recently read The End of Men by Christina Sweeney-Baird and Mirrorland by Carole Johnstone, both publishing in April 2021, both in first person, as are many others.)

Young adult fiction and psychological suspense novels, in particular, are often written in first – I believe for one significant reason: the reader can step directly into the character’s shoes, and the story unravels as though it’s happening to them. First-person characters rarely describe their appearance – why would they? They can’t see themselves – and so, other than perhaps a passing mention of hair colour, they act as a blank avatar for the reader to populate with their own traits. This ups the ante for tension and conflict in suspense thrillers (‘don’t go in that room!’ then: ‘I’m going in that room!’), and adds to the 'swoon' of teenage love, because the reader feels like it’s happening to them. That awesome guy is looking at us across the cafeteria. Remember what that feels like?

So why would you choose to write in third person, when first is so intimate, commercial and clean? Especially when you’ll often hear the criticism that third person can be ‘distant’?

I think of it like a fist held in the air in front of your right eye. (Bear with me.) In first person, the fist was inside the character’s brain, privy to all their thoughts, looking out through their eyes. But in close third person, the fist is just in front of the character’s right eye, able to look at the world surrounding them, but also able to look back at the character themselves. If you’re writing fiction where the character experiences external change, as well as an internal shift, you may want the 360º perspective that third person provides. We want to see it happening to that character, and project our thoughts onto them, rather than walking completely in their shoes.

Third person is classic.

First person voice, done badly, can be pretty exhausting. Have you ever read a novel where you long to get out of a character’s head and see the world, and whooped with delight (or relief) when the perspective has switched to another character? I have. I would go as far as to say I’ve abandoned more first-person novels than third, because if you don’t like the voice in first, the voice is everything.

Each story has its own needs. One of your novels might work brilliantly in third; the next, in first. I don’t believe in blanket rules or house style for authors, but I do think auditioning the narrative and extensively playing with the execution of voice will help you uncover what this particular novel demands.

Confession time. I wrote the first draft of my third novel-in-progress in first person. But in later drafts, I’ve realised I need a gap between the narrative and the character. I need room for objectivity and to judge them, a little bit, and I certainly need to see them. And as a dual narrative, I need more space to show the world around them than being trapped inside the two alternating voices could ever provide.

The amount of work involved in reworking an entire dual narrative novel written in (2 x) first person, present tense, into (1x) close third, past tense, gives me the palps and, like a solar eclipse, I can’t quite look at the problem directly or else I’ll go blind… But it’s work to be done, so I’m rolling up my sleeves because I can see that the novel is already much better for it. Chicken, not frogs, that’s what I keep telling myself. No tiny bones caught between the teeth today, thank you.

But what about the ‘distance’ of third?

It really depends how far away you want that fist to be from your character’s eye. If you’re writing an omniscient third-person narrator, that fist is probably way up there in the sky, looking down on the landscape. In close third, the fist is just in front of their face. And I can assure you it is possible to write in close third and have it feel just as intimate and distinct as first, while also maintaining that nice, refreshing gap to breathe. This is the technique I’m using in my latest, and it’s one I absolutely adore.

Free indirect speech

Often known as free indirect style, speech or discourse, this is a method for expressing the character’s inner thoughts by placing them directly in the narration, rather than having a character express them directly.

For example, direct/reported speech is when a character’s own words are quoted (with speech marks):

‘The bar’s heaving, isn’t it?’ said Katie. ‘I thought people would have more sense during a pandemic.’

Indirect speech tags the character’s thoughts or words with a clear attribution such as ‘she said’ or ‘she thought’:

Katie thought the bar was busy for a Wednesday morning in the middle of a pandemic, and resolved to go home immediately.

You see how this feels slightly distant, still? A clear delineation in the narrative (‘Katie thought’) gives the feeling that what the character is thinking is *somewhere over there*.

Free indirect speech, by contrast, dispenses with ‘she said’, ‘she thought’, and often with speech marks or italics entirely. It places the character’s thoughts, with no attribution, directly in the prose.

Katie walked into the bar. Jesus, it was rammo in here. Time for a nice walk in the sun followed by an ice cream in the shade.

Whose thoughts are we hearing about the bar being rammed, and who wants the ice cream? The colloquial choice of the word ‘rammo’ as well as the light blasphemy indicates it’s the character, rather than the narrator’s voice, doesn’t it? Free indirect speech retains the idiomatic qualities of the character’s words. The gap is closed.

This isn’t anything new: Jane Austen was a master of free indirect speech, using it extensively in Emma and Sense & Sensibility. D.H. Lawrence liked it, too. Consider James Joyce in Ulysses:

He kicked open the crazy door for the jakes. Better be careful not to get these trousers dirty for a funeral. He went in, bowing his head under the low lintel. Leaving the door ajar, amid the stench of moldy limewash and stale cobwebs he undid his braces. Before sitting down he peered through a chink up at the nextdoor window. The king was in his courthouse.

And we can’t talk about this technique without mentioning Virginia Woolf, probably the MVP of free indirect speech. As well as To the Lighthouse, Mrs Dalloway is considered a masterclass of the style:

And as she began to go with Miss Pym from jar to jar, choosing, nonsense, nonsense, she said to herself, more and more gently, as if this beauty, this scent, this colour, and Miss Pym liking her, trusting her, were a wave which she let flow over her and surmount that hatred, that monster, surmount it all; and it lifted her up and up when – oh! A pistol shot in the street outside!

Oh, the voice! Right there in third person! It makes me happy.

If you look, you’ll find this style in modern fiction, too. It won’t have thoughts reported in italics, and it will move quite freely between indirect speech and free indirect speech. If the novel is written in the third-person point of view, and the narrative is peppered with the voice and thoughts of a character that feel idiomatic of that particular person, there’s a good chance this is free indirect speech.

Can you find an example in a book you’ve read recently? And will you try it in your next novel?

Happy writing,

Katie

Sign up to one of our writing courses and you can choose Katie Khan as your tutor and start writing with the guidance and support of a 'writing' mate today. Write with confidence.

September 12, 2020

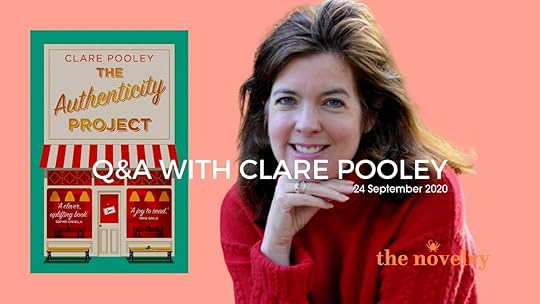

Clare Pooley - Finding Your Voice.

From the Desk of Clare Pooley:

Let me share a secret with you: The Authenticity Project is not actually my first novel. Lurking in the very bottom of a bottom drawer, is a bound, annotated and rather dusty manuscript of another book called Can’t Get You Out of my Head.

That story did the rounds of most of the literary agencies in town, and out of town, and gathered a full gamut of form rejections. I read and reread all the usual platitudes; we receive thousands of submissions, the market is extremely competitive, we hope you find the right home for your novel. I even had a couple of requests for the full manuscript, leading to weeks of refreshing my email inbox in feverish anticipation, composing the victory speech for my book launch in my head, before receiving a whilst there was much to admire, we just didn’t love it enough. Looking back at it now, I see that my first book had a pretty good premise, some interesting characters and a rollicking plot. What it didn’t have was a voice.

I’d heard publishers and agents talk about their search for a ‘unique voice’, but I wasn’t at all sure what that meant, if I had one and – if not – where I could find one.

An author’s voice, I learned, doesn’t come from their characters. Each character has their own individual way of talking, but lurking in the background, always, is the voice of the author, the storyteller. It’s their unique way of speaking to the reader that means that you can read just a few pages of a book, with no cover or blurb, and be able to tell it’s a Sophie Kinsella, a Lee Child, or a Maggie O’Farrell.