Louise Dean's Blog, page 18

February 22, 2020

Podcasts for Writers.

Convert that commute to a crammer session with inspiring content from fine minds in literature and publishing. You'll find here the best podcasts for writers according to the novelists of The Novelry.

These podcasts with writers and editors will prove consoling and cheering, and see you through not just the first draft, but the long haul. Ten great podcasts to keep writers smiling.

How To Get Podcasts.

All podcasts are free, and most are available via many different apps.

On a website:

You can do this from a computer or from the web browser on your phone.

Find a website that has podcasts you like.

Find the player on the page, check your device’s sound is switched on and click play to listen to the podcast.

On your iPhone or iPad.

If you have an iPhone you can use the Apple podcasts app to listen to podcasts.

The Podcasts app should already be downloaded on your phone so search your apps for ‘Podcasts’. If it’s not, go to the app store and download it.

Open the Podcast app and go to the search page (click on the magnifying glass button in the navigation at the bottom).

A search box should appear at the top, next to another magnifying glass icon. Tap on this and type in the name of the podcast you want to find. Hit “enter” on your keyboard.

Choose the podcast you want from the search results and tap on it. This should take you to the podcast’s homepage.

Once you’re on the podcast homepage you’ll see a list of recent episodes. Tap on one to play it.

If you like what you hear, a subscribe button at the top of the page lets you subscribe for free. This means the app will automatically download the latest episodes to your library.

On your Android phone.

If you have an Android phone you can use the Google podcasts app.

Install the app.

Once you open the app, use the search box (look out for the magnifying glass icon) and type in the name of the podcast you want to find.

Choose the podcast you want from the search results and tap on it again. This should take you to the podcast’s homepage.

Once on the podcast homepage you should see a list of most recent episodes. Tap on one to play it.

If you like it, tap the subscribe button at the top of the page. When you subscribe to a podcast, it’ll appear at the top of the Google podcasts app, and a new section in the app will let you know about new episodes from podcasts you’ve subscribed to.

The Novelry's Top Ten Podcasts for Writers.

Lessons in creative writing from great novelists, poets and playwrights such as Ted Hughes, W.B. Yeats and Allen Ginsberg. Find Your Story. Place. In Search of Character with Graham Greene. Find Your Voice. Routines and Rituals.... Presented and produced by Cathy FitzGerald. Updated weekly. Enjoy.

2. Backlisted

Backlisted is one of the most popular book podcasts. Each episode features a guest (usually a writer) who has chosen a book they love and which they think deserves a wider audience. Over 100 books are discussed. Enjoy.

3. Close Reads

A book club type podcast in which the great works are discussed in close details for you to explore how they work featuring the novels of Hemingway, Jane Austen, Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby and many more. You'll find your 'hero' book here! Enjoy.

4. The Bestseller Experiment

"Meet the writer's who sell millions of books," Washington Post. Listen to leading lights from the publishing industry, million-selling, chart-topping authors who collectively have sold over half a billion books. Binge on over 250 interviews with authors including Michael Connelly, Joanne Harris, Ian Rankin, plus agents, editors, and more. Enjoy.

5. What Editors Want

An interview with a different editor each week from the world of publishing. It’s aimed at readers who want to hear the behind the scenes story of how their favourite books get made, and aspiring authors who want to know how to get published. Featuring advice from editors behind Nobel and Booker Prize-winning authors (and practically every other literary prize.) Truly heartening. I recommend the enjoyable episode with Louisa Joyner from Faber. Enjoy.

With Robert Harrison. Interviews with opinion leaders from the Arts such as Marilynne Robinson, Sarah Churchwell on The Great Gatsby, Grisha Freiden on Leo Tolstoy. ("For civilised man, death has no meaning...") and Tobias Wolff on American Fiction. Enjoy.

Dan Simpson looks inside the daily diary of writers; tips, tricks and inspiration. Episodes with B.A Paris. Anne Cleeves ('learning by living and never plotting'), and Jeffrey Deaver, the bestselling thriller writer on research, writing and puzzles. "As much as I enjoy literary fiction, that's not what I do. I create puzzles and games." Enjoy.

A weekly look at the world of books, presented by Claire Armitstead, Richard Lea and Sian Cain. In-depth interviews with authors from all over the world including Sophie Hannah on the perfect recipe for a crime novel, Elizabeth Strout on the return of Olive Kitteridge, Madeleine Miller on why Circe is the perfect protagonist to upend the traditional hierarchies of myth, Ann Patchett, Lucy Ellman, and many intriguing subjects including Feminist Fairytales. Enjoy.

10. How To Fail

Ultimate comfort listening! Novelist Elizabeth Day shares lessons from the challenges in her own life and those of famous interviewees including Marian Keyes, Sebastian Faulks, David Nicholls. ('Despite all his achievements, Nicholls admits he still feels ‘very thin-skinned’ which is partly why he left Twitter after accidentally getting into a row with Stephen Fry and why, when a critic once said ‘No-one turns to David Nicholls for great sex scenes’ he felt he had to defend himself.') And Phoebe Waller-Bridge. ("I've always got a kick out of saying something which feels truthful but is taboo.") Enjoy.

If you're looking for something more than a podcast - why not try our online creative writing courses? We're ready and waiting to welcome you home.

February 15, 2020

Get Published. ( Know The Market.)

All change.

Last week, on our intensive writers' residential course, we heard from bestselling authors Sophie Hannah and Louise Doughty and from literary agent Tim Bates at Peters, Fraser + Dunlop.

The three agreed on one thing. Since 2000 the market for fiction has changed dramatically, and these three long-haul survivors have learnt one lesson very well. The rise and rise of psychological fiction, and the thriller form, has changed the way we want to read books now. The rise of this fast-moving genre coincides with the Age of Impatience and the new media of Netflix & Co. 'What's going to happen, next?' We expect twists and pace.

The thrills and spills of mainstream fiction via this dark, internalized cloak and dagger genre and it's partners in crime and mystery, has snuffed the life out of the Literary Fiction genre, irreparably it seems. if you want Literary Fiction, see Trollope. Tim Bates made the comment that literary fiction can only make it if there's a death thrown in.

Take note. For me, the most stunning book of the last year is Oyinkan Braithwaite's 'My Sister the Serial Killer'. It is virtuouso plotting. Once she had the concept, and the title, the job well begun was more than half done. The book is described as a 'literary thriller'. Why? There is no purple prose, no long descriptive passages of setting or mood, no reveries included. We might wonder what Lagos looks like. Ms Braithwaite declines to tell us, after all she has a plot to unpack. Backstory, as I showed my writers, is handled where it appears in a single sentence in brackets. (I've put it in bold below so you can spot the backstory!) With breathtaking economy she nails the relationship with her sister in the early pages thus:

The knife was for her protection. You never knew with men, they wanted what they wanted when they wanted it. She didn’t mean to kill him; she wanted to warn him off, but he wasn’t scared of her weapon. He was over six feet tall and she must have looked like a doll to him, with her small frame, long eyelashes and rosy, full lips.

(Her description, not mine.)

My Sister, the Serial Killer is as literary as you're going to get published in today's market, that's my point. And it's stupendously good, because it's so well considered.

What's the definition of a good writer in 2020? Someone who does not waste their reader's time.

We know what land, buildings, sea and sky look like, thank you. We have a history of fiction now weighty and redoubtable which has persuaded the common reader of their understanding of such things. If you're not sure what those things are like, please see Mr EM Forster et al.

Ms Braithwaite's novel is 46,656 words. (The Great Gatsby is 48,985). It is not called a novella. A novel, it seems, is defined by the ambition of its story and its ability to create a self-sufficient world for the reader, rather than a cut-through or passing glimpse.

She offers 75 chapters, at a median of 622 words each. As I explain to my writers, punctuation and layout, i.e the space between the words plays a vital role for the reader. It tells the reader to go figure. Every full stop or period, every new sentence, new paragraph and new chapter causes a pause for thought. Oyinkan Braithwaite lets the reader do some work. She doesn't spoonfeed them. She raises the game posited in her singular prologue with every new chapter.

This is her prologue with its title:

WORDS

Ayoola summons me with these words—Korede, I killed him. I had hoped I would never hear those words again.

That's the lot. Got it? Let's go!

Both Sophie Hannah and Louise Doughty began their careers with more literary domestic tales. The market began to shift in the early 2000's. Authors who survived - shapeshifted.

Mid-career literary fiction writers have been cut off at the knees for 30 years now, as Maggie Gee describes in her book 'My Animal Life, detailing her depression that after six well-reviewed books she could not find a publisher for her new book.

The ‘Disaster’ years came more or less exactly in the middle of my career to date, with my sixth, out of twelve, books (this is my thirteenth). It turned out to be the middle, but it could have been the end.

(...)

I still felt terrible shame and unease when other people asked about my writing. I was unable to admit I had been rejected. Yet my internal landscape was slowly shifting. I had been rejected. So what would I do now?

Maggie Gee. My Animal Life: A Memoir

The era of supporting authors through a career and a body of work was gone with the new Big Five publishers compelled to return profits. And then came the publishing bloc, the powerhouse of The Psychological Thriller...

Failing to 'earn out' their advances, authors had difficulty securing book deals, and if they did, as some have confided in me, they saw their advances cut to a tenth of what they once were as publishing changed with houses becoming subsumed by the five conglomerates, and readers tastes changed.

'Bad track' is an ailment writers suffer, which is invisible to them, and can only be seen by literary agent and publisher. If you're a previously published writer, failing to get picked up, no doubt you've got it. It means your sales figures were low and you failed to sell books sufficient to your advance. Since 2001, Nielsen Bookscan has been keeping count. Agents and publishers access Nielsen Bookscan, and so can you, at a price! Starting from £90 for just one ISBN! Find your 13-digit ISBN and email isbnsalesreport.uk@nielsen.com to get your figures if you dare. But the diagnosis is one thing, treatment is another. I'd focus on the treatment and as I say to many of my writers - forget about that last book. It's history. Get with the new story!

Writers have to cut and cut again their cloth to fit the new era, or give up writing. Readers want stories. This is where we start work at The Novelry.

We focus on what's in it for the reader before you the writer put pen to paper.

Maggie Gee describes her awakening;

...too many twentieth-century novels are weak on story. Yet story is what readers like, and they’re right, it’s what we need from art: stories to help us navigate the confusion of our own life-stories.) ... Yes, three acts, like every good drama. With plot points and a mid-point, a swoop up to the climax, a dip to the end.... I sat on the train and redrafted this structure in terms of a 250-page novel. On which page should the plot points come? And the climax? ...On the three-hour journey home, things crystallised. I was a writer, but what was I writing? It was time to write myself out of trouble. The only thing I could do was write, and no one, no one could stop me writing.

Maggie Gee.

Louise Doughty grasped her writing by the scruff of the neck, and redrafted her book 'What you Love' to offer a more thrilling narrative pathway with a few revisions of structure. She describes a moment when looking at the baggy manuscript, she recited to herself a line from Michael Caine in Get Carter:

'You’re a big man but you’re out of shape, with me it’s a full time job.'

Her career since that novel has been stellar with Apple Tree Yard a Sunday Times bestseller.

If you're a debut author, you can get away with some literary style; descriptive passages and so on, but if you're a published author, you're going to struggle to get a deal of any shape or size if you don't write keen and lean.

The best approach for all writers of any genre at any stage is to put story first. Keep your sights on what readers want. Give yourself the slip. Get a move on. Know what question your reader's reading to find out and keep that ball in play.

This approach is the foundation of our method to guide writers, aspiring and published, to commercial success - a career in writing. We mean business. If you'd like writing novels to be 'a full time job' for you too, join the worldwide fellowship at The Novelry. Stay focussed.

February 8, 2020

Edit My Novel: The Final Polishing of Your Manuscript

How to get your entire novel manuscript that final professional polish submission?

It's a two-stage process.

First, DIY. You grow as an author by being able to edit your own novel through numerous passes, and our Editing courses will help you eliminate a few drafts. We'll show you how to do it, giving you a method to last you a lifetime. (Our 'reversible' course is quite a cool way to plan a novel too!)

Second, Professional Help. When you've done multiple successive drafts and cracked story and character development to the satisfaction of any reader, you'll want to dot some i's and cross some t's and you may wisely feel you need another pair of eyes on your full manuscript and some final proofreading beyond the tools we recommend at The Novelry, you'll need some human help which can take into account your creative treatment's quirks and ploys.

1. DIY.

You need to be very hard on your work, and push it through as many drafts as required. As writers, we are always changing. Writing a novel over many years proves problematic to the integrity of the story, and when we outgrow the original idea, we layer up with themes and contrivances to cover up the fact that the original circus has left town. It makes for a baggy old bastard of a manuscript this is a long way from a publishable novel. Get a grip! Get back to the story and what readers want and get a single-minded focus. what's the imperative driving force? Everything else is subsidiary so relegate it.

You see, we are always finding ourselves, how we write and what we want to write about and how we want to write it. TS Eliot complimented Virginia Woolf's third novel - Jacob's Room - which was published the year he published The Waste Land, saying that he had found herself as a writer, found her voice.

Who you are as a writer is much about what you won't do and what you leave out, I have found. If you want to know who you are, as a writer, if you want to find yourself, the best way to do that is to disappear from your work. Eschew the interpretation and commentary, and simply say what you see. Proceed visually as if it's a movie, only show us beguiling dissonant bizarre things and thus we will know you and the characters of concern to us, but what they look at, by what stops them in their tracks.

What you show us, as with a visual artist, tells us what we need to know. You can tell a story, you know, by proceeding from one visual to another and I urge you to try it, even if only at the opening of your book.

I see a lot of novels-in-waiting, and while I am encouraging and constructive at first draft, I am rather fierce when we get to the edit. We must have standards. Our standards define us as professionals. Never let work go out half-cock.

The problem I see far too frequently is the overwrought opening with 'gut-wrenching', 'heartbreaking' descriptors in your opening paragraph. It's lacking in creative decorum. We do not open correspondence or communication in our lives this way. You're imposing on the reader, presuming on their interest before you have established a pleasing credibility.

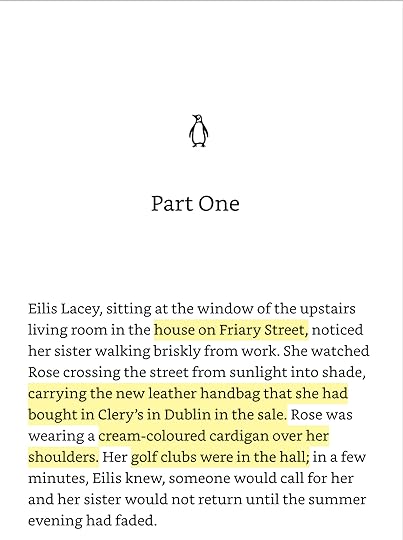

I show my writers the opening to Colm Toibin's novel Brooklyn to give them the drift, fast.

Have some decorum. Show us what you the author, or your main character sees. Seeing is empathy; the doorway to sympathy.

I suggest writers delete purple passages, overwrought and dripping with mawkish emotion in those opening scenes. Often they've been supersized with an extra-large side of clichés or conventions. These things hang together like knock-kneed kids in the playground. We can't all be poetic and original all the time; happily we don't have to be. If you can't find a witty way of putting it, then delete it, or pare it back to a passing sight, a glimpse.

Why do we do this writing? Not because we're stupid. We do it because we're overindulgent parents to our prose. Make sure you give yourself the four weeks mandatory reading period we impose at The Novelry between finishing that first draft, and going back to the work as a reader. You need to regroup and cut to the chase of story, then apply the dose of salts we call the Editing Course after which you float that first chapter past your fellow writers and hope they'll be kind enough to kick it ever-so-gently.

Don't share your work with anyone at first draft. Learn to develop and edit your work. These are vital skills for an author. Become your own editor, know what's good the old-fashioned way - by comparison.

Well, comparison might be 'the thief of joy', but I'd suggest you reserve the joy to the creative phase of the indulgent first draft and get dour for draft two. The technique I used with my first novel was to compare each page, randomly-chosen, with a page from a favourite novel, randomly-chosen and to see where and how and why I fell short. Our Editing course trains you to be tough, save money and save face.

But after many drafts, you may want to structured feedback, a human response and a machine-like clean.

2. A Professional Polish.

One of Oscar Wilde's stories was that his hostess in a country house having asked him at dinner how he had spent the day he had answered: “I have been correcting the proofs of my poems. In the morning, after hard work, I took a comma out of one sentence.” “And in the afternoon?” “In the afternoon, I put it back again.” (Robert Sherard - Life of Oscar Wilde.)

When you've exhausted yourself - using all the tools we recommend at The Novelry - you may consider professional editorial services on your entire manuscript. Do not do this too soon. Apply the Oscar Test!

Be careful.

Look at the business models of the different providers, they speak volumes. Pricing is all much the same from £750 to £1250 for a full novel manuscript, but these animals are not equal.

Some consultancies require a commission on your work if it's good and they'll even offer to find you an agent. Ouch. Their commission plus the literary agency commission could cost you a full quarter of your advance. Check the small print.

There are sites which act as hubs for freelance editors. Think of these as a street market, in which many independent traders offer their services through the site. You can shop for the prettiest colours and buy from the better trader, but never forget it's that traders wares you're buying - which is to say that the website has offered them a market pitch but isn't too fussed if the product is substandard. After all, the merchant goes out of business, or desists or disappears and others replace them.

There are providers which offer branded services and preserve the anonymity of their editors. This is a good thing.

Take for example a service like Scribendi, in which you don't know the name of the trader, but are provided with their branded product which meets their product standards. This is what John Lewis is to the street market. The service has to meet the brand's standards for the business to survive. Reviews will be public and in the brand's names whereas, with the street market model, the reviews are given to individuals and not public. In almost any service you purchase, look for a brand that stands as a seal of standards. Human beings are highly variable and if you go free-range, the reviews shown at their site are naturally hand-picked. You might not get on with that person, or your work might not suit them.

Look for companies with public reviews on trusted platforms like Trustpilot. Scribendi is rated 'excellent' on 84 public reviews. If you look at the street market as a platform you'll find very few reviews and those will be poor.

So, which branded provider to choose? You can get free samples of the type of editorial development comments you'll get at their websites. A road test of Papertrue eliminated the service quickly in our single sample run as the editor's comments were misspelt. However, Papertrue gets great reviews on Trustpilot and might be better suited to other genres, and non-fiction. Let us know what you think!

Scribendi. A read of a 70k manuscript at Scribendi cost just over £1000, and was well worth every penny. I ran my novel through their service.

First, there was a highly sophisticated and detailed report on the storyline itself, and this was accompanied by forensic comments on the text. The editor read the manuscript twice; 'once for an overall understanding of the story, and again as a close reading, wherein I made revisions when necessary.' The story overview gave a fascinating analysis of my writing habits and tendencies. The editor examined the development of the main characters and spotted a hole. (One key character disappears and she pointed out it would be satisfying for readers to have him referenced again and to know what happened to him.)

The attention to detail was highly professional with very careful grammar and punctuation work. It was obvious from the notes the editor took pride in her work and went well above-and-beyond. She'd researched place names and people and checked the references were accurate in terms of locations and distances and timing. Wow.

Give the editor a good brief and explain your intentions and treatment. My editor understood the notes I gave her and made erudite and useful suggestions to improve readability that fit with the tone of voice and dialects used and the style I use.

But most important to me, at this point of a novel's journey when the writer is flagging, my editor gave her human response to the story too, with notes where she'd laughed and cried, and - ahem - to paraphrase Eric Morecambe - all the right notes in all the right places. Though I don't know her, I felt we became friends and in the notes, she let me know which parts had struck her according to her own life experience. I paid for this service, but I feel indebted to the invisible editor for seeing my novel as a living thing.

My road test proved Scribendi to be a five-star service. Highly recommended at draft ten and beyond ;-) By the way, the editor's code for the fabulous editor I used is EM1606. You can get 5% off your order with this discount code for Scribendi at checkout PROOFREAD2020.

Now, one last word of advice. Don't use a service for your Query Package, neither Scribendi nor any other. It's important to convey your personality, a flavour of the novel, and your intentions as an author and no one can put this better than you. Keep it modest and light and brief. We show you how in the Editing course and give you a winning sample (based on one of our member's success stories.) The Novelry's members are very good at sharing. Our logo is the octopus, one collective bulging brain and many tentacles writing. Experience, and joy.

February 1, 2020

Writing Competitions.

As we enter the exciting season of our annual Firestarter Competition at The Novelry for the best opening to a novel in progress, it's worth thinking what entering competitions can do for you and your career as an author.

Some points of view from our writers.

From Longlist to Literary Agent: My Year of Writing Competitions.

By Louise Tucker, member of The Novelry.

This time last year I started entering my unpublished novel into writing competitions. I had drafted and redrafted it, had good feedback from agents but no takers, and wasn’t quite sure whether to give it up and start something else. Then someone at The Novelry shared a link about the Stockholm Writers’ Festival First Pages Prize and, thinking I had nothing to lose but money, I entered.

The same week another friend at The Novelry put up a reminder about the Lucy Cavendish Prize and I decided to enter that too. What harm? I thought, as I pressed the ‘submit’ button and paid out some more cash; at least I was constantly revising and revisiting the crucial first pages and chapters.

A month later I received notification that I had been longlisted for the Stockholm First Pages Prize.

Was I ecstatic? For three days, yes. On the fourth, I found out I wasn’t on the shortlist.

But that small success encouraged me and in May I entered three more: the Bridport Prize Novel Award, the Bath Novel Award and the Blue Pencil Agency First Novel Award.

Part of me thought it was like buying tickets in a rather expensive lottery (they all cost something to enter) but at the same time, another part of me thought this is really good training for submitting to agents. I kept a note of the longlist dates then forgot about them.

Six weeks later, a friend at The Novelry direct-messaged me: ‘I think I’ve spotted your MS about 4 times so far in the Bath tweets!!!’

Bath tweets? I headed over to Twitter, a place I spend very little time and energy, and found a whole series of comments about various manuscripts, many of which sounded very much like mine:

‘Widower must cross the world with his late wife’s ashes. Clear and moving, an emotional YES’.

Those tweets are short hints, but there were five that sounded familiar. The Stockholm First Pages Prize had given me confidence but these tweets gave me something else entirely: an audience. It was thrilling.

Soon afterwards, I found out I was on the Bath Novel Award longlist. At that stage, the stakes got higher. Longlistees must submit the whole manuscript within nine days of the announcement. In a rush, I finished some rewrites, proofread the whole thing two or three times then sent it in. I tried not to hope for anything more. This was, after all, my first attempt at fiction. Two long-listings was already a great start.

One thing I hadn’t expected was that a hint of success would help me with all my submissions. Although I still agonised over every line before entering competitions, now it took hours not days. I was tougher, quicker, more confident. And, more importantly, my agent letters now included the word ‘longlisted’ which made me feel I had raised my game or at least raised my head above the ‘enthusiast’ parapet to gaze upon the walls of the previously unassailable ‘professional’ castle.

In July I entered a new competition, The Agora Lost the Plot Work in Progress Prize, and the Bath shortlist was announced. My partner kept reminding me that a longlisting was already a fantastic achievement and, on the day it was announced, I kept repeating ‘you’ve already done well’ so that I didn’t feel too disappointed. I was getting dressed after a shower when the shortlist tweet went up; seconds after I saw my name I was downstairs again, half-naked, waving my mobile phone under my partner’s nose. ‘LOOK!’ I shouted. ‘LOOK!’

In August, I was longlisted for the Agora prize; two weeks after that I found out that I had won it.

The ‘writers’ survival kit’ that came in the post was welcome, but I was more interested in the promised chat with a PFD agent. I had a surreal email exchange with them, asking them not to link their prize with my Bath shortlisting, since the latter was anonymous. In eight months I had gone from being the writer of an unread book to balancing prize announcements.

Finally, in September, the Bath Novel Award ceremony took place. I didn’t win but, finally, I understood the cliché: it really is a prize to be shortlisted.

Not only did I get to talk to readers of my work, people who had loved and chosen the book for the list, but I got to read some of it out loud. I had an audience, in front of me. An audience who listened and clapped. It was only at this moment that I realised that what I had started back in January had changed the future of my writing. I had stepped through what Stephen King calls the open door, begun sharing my work and was reaching people.

That would have been enough. But the Bath Novel Award is proactive in its support. Caroline Ambrose, the organiser, wrote to me and asked if I wanted her to recommend my book to literary agents. At the same time, having read my extract on the Bath website, an agent got in touch with her to find out whether I had representation. I was driving around Europe by this time and relatively unreachable. Even so, I found myself in a hotel in Warsaw having an hour-long conversation about the plot and what needed to change. By the end of the call, I had an offer.

Home again, I met that agent and several others. Whereas in the past I had grasped at the first offer of representation which didn’t end well, this time I made sure I considered them all. In some ways, it’s a high-wire game. Some agents won’t wait for you to meet everyone interested (one of mine stepped down); others write to you in a flurry of excitement after reading the first few chapters, then go completely quiet once they read the rest; others get back to you long after you’ve given up on them and chosen someone else.

But, whereas a year earlier, I had submitted my book almost like a novice boxer going into the ring, anxious and full of trepidation, now, with all of those tiny gongs under my belt, a new-found confidence underpinned all my negotiations. The book had been longlisted, shortlisted and won. So even if it didn’t find a champion this time around, it would at some point. It did, though, in the form of Julia Silk at Kingsford-Campbell. Now I’m entering another ring, that of editing.

So, if you have just missed the Lucy Cavendish, don’t despair. There are several more, starting with the Stockholm Writers’ Prize (the name has changed) as well as a new, different First Pages Prize this month. Research all those you are eligible for, find out the submission guidelines, put them in your diary, get your pages ready and enter as many as you can. You might not place in any, you might not hear from any, but if you do, it could lift your book and your writing from hopeful to happening. Competitions will give you confidence, help you hone your submission, which is good practice for querying agents and publishers, and, if you’re lucky, get your work read and recognised.

One thing to remember: not all competitions are created equal. You might get feedback. You might get updates. You might get neither. The Stockholm First Pages sent really detailed general feedback to longlistees, the Cavendish and Blue Pencil updated entrants on the competition process via email, whether they had placed or not, but the Bridport sent nothing.

The prizes are also different. I won one prize; my winnings were chocolate and a chat. I was shortlisted for another; they helped me get an agent. Try them all. And see where a year might take you.

Sam Hudson: Finish the Bloody Thing!

Last year I entered a handful of competitions and, for most of them I almost forgot I had entered until the results email arrived. I think for me the only negative side of the experience came when there is additional marketing by the competition such as Twitter feeds. I got really sucked into Bath and it meant that I was occupied with idle, and frankly boring, fantasies (I do have a vivid imagination after all) when I could have been thinking about my book.

But, there is something wonderfully freeing about all this. A moment of maturity. The competition fairy godmother isn’t going to spot my chapters sparkling in amongst the ashes. I just have to do the work and get support and advice from trusted and real sources.

Here’s what I wrote the day of the Bath shortlisting:

I have decided to take the matter into my own hands and I don't mean storming down to Bath and demanding a recount. I am going to finish this bloody (but beautiful) thing. No more relying on fate, or some chevalière in shiny armour to spot my hidden potential No more relying on fate, or some chevalière in shiny armour to spot my hidden potential.

Kate Tregaskis: Being Listed is a 'Win'.

I've been entering competitions regularly for the past few years since an agent told me to as a way of building my writing credibility and writer’s CV. Most are annual, so it’s possible to watch them approach, to engage with them and then wait for them to come around again.

The entry fees can add up, though more and more competitions are offering cheaper or no-cost submissions for people on a low income.

One thing I am quite wary of are competitions where the prize is publication by a particular publisher often with a relatively low fee in lieu of an advance - in this case, the prize is often a small amount of money and an agreement to be locked into a relationship with a publisher that I wouldn’t, given the choice, necessarily choose to be with.

I have a writer friend who is very systematic about short story competition submissions in that she will submit a story, it will be rejected, she will polish it and then submit again to another competition, over and over - until she is successful. And she is very successful.

Competitions I’ve entered regularly include Mslexia, Bath, Bridport, Lucy Cavendish, Fish Publishing Prizes, Exeter Fiction Prizes and Grindstone Literary Prizes.

The reason I enter is not so much because I have an expectation of winning (the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize last year received 600 entries) but because it is an opportunity to hone what I am doing, to imagine it through the eyes of someone reading it for the first time, and perhaps get it read - if it rises high enough - by the agent or author who is judging.

Applying to many, often, does increase the probability of getting somewhere with them. In 2016 my first novel got as far as being shortlisted for the Caledonia Novel Award. The same novel was long-listed for the Spotlight First Novel Competition and Highly Commended for the Yeovil Literary Prize. I have had a short story shortlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize and in 2017 three of my short stories were shortlisted for the Bridport Short Story Prize.

These ‘wins’ that aren’t actual wins are still 'wins' because they give me something to put on my writer’s cv. It means that when I have had stories published or when I have applied for grants, bursaries or other opportunities - or indeed when I have approached agents - and I’m asked for biographical details, they stand as credentials I can put on my writer’s cv.

Thank you to our canny, bonny writers for sharing their experiences. Our members can find a list of writing competitions at our Members Library and we keep you up to date with deadlines at our Community.

Now, scrub up that first chapter for entry to our annual Firestarter competition! First prize £150 and submission of your work to our literary agents Peters, Fraser + Dunlop and others.

January 25, 2020

The 21st Century Title.

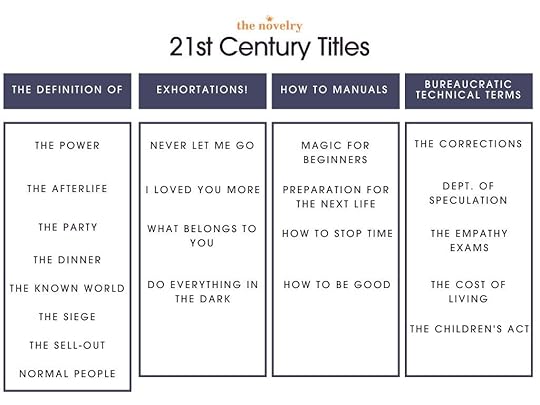

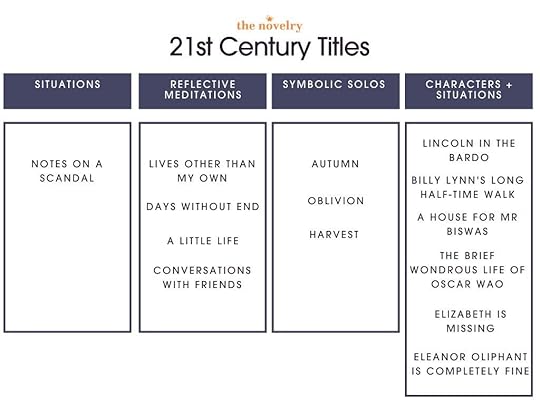

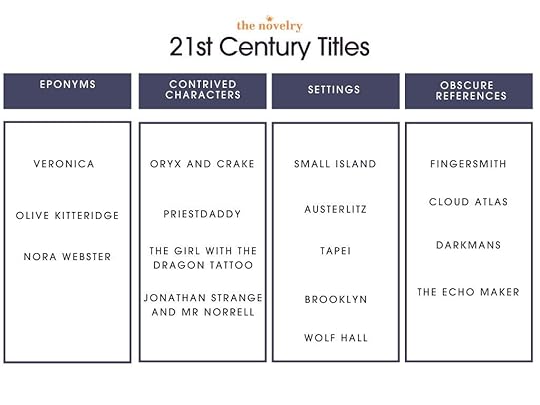

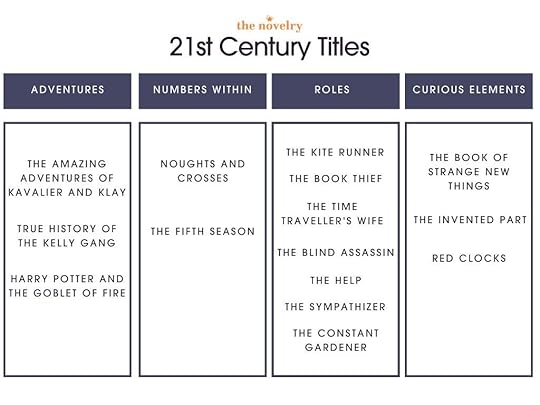

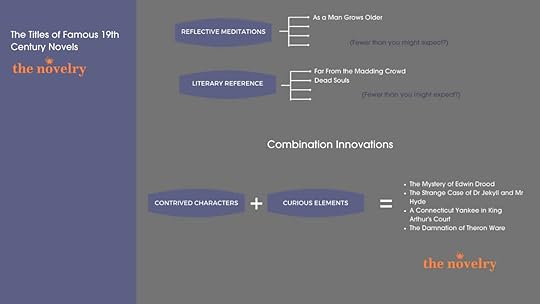

In the first blog of the series, we took a look at why you should start your novel writing plan with your title rather than pick and mix as you go or pin a tail on the donkey at the end. In the second blog we saw the dominant form for the novel title prior to the Twentieth Century was the eponym - or the name of the main character of the story. In the third blog of this series, we saw how the dominant form for the novel title in the Twentieth Century became the Reference; poetic or biblical. In the fourth blog, we saw the emergence of low-brow references and the rise and rise of the Supermodel Solo title at the end of the century.

Welcome to the 21st Century, which we might describe as the Age of Obscurantism, with strained efforts on the part of authors to reach for titles which challenge the reader.

References become more scientific, technical, ever-so academic, arcane, abstruse and sometimes unwelcoming of the less advanced reader in the post-religious era of the ivory tower author, far from the madding crowd. Populism was positively discouraged and our Supermodel Solo (one-word titles) became lofty, packing ivory tower heels.

Now, we see a major rift opening up; a chasm between high brow literary canon and the common reader.

This research is drawn from 'literary lists' recognizing the 'great novels' according to the reviewers of The Guardian, BBC Culture, Powell's Books and Vulture. In the first part of this blog we're dealing with the 'deified' works. And this in itself speaks volumes. We are witnessing the rise and fall of literary fiction. Perhaps, part of its demise can be attributed to the cryptic suicide notes of its authors' titles. Remember, the title is a statement of literary intent, and these titles scream - cleverer than thou!

Some authors - like Colm Tóibín, Philip Roth, and Elizabeth Strout - bridge the gap by offering broad-based titles with traditional phrasing - location, character names or situational settings.

Some temper the fine fare of their novel with the salt of a wise addition of 'The Adventures of...' (See Michael Chabon: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay).

But too often, the literary gentry took the elevator to the penthouse. Novelists in search of esteem became the political party that disdains its voter base. (See: Margaret Atwood's title Oryx and Crake. Fair do's these are characters within the novel, but the statement of literary intention this is forbidding. Better The Edible Woman than the indigestible luvvie.)

We can imagine our authors kicking the backsides of their Bibles and poetry anthologies out the door in favour of academic textbooks, science reference and technical manuals.

The Sense of an Ending (Julian Barnes) title comes from a book of literary criticism by Frank Kermode first published in 1967, subtitled Studies in the Theory of Fiction, the stated aim of which is "making sense of the ways we try to make sense of our lives". The critic Boyd Tonkin noted that Barnes's "show-off" characters could be typical readers of Kermode's work.

I feel I owe it to you to explain, though possibly you were completely au fait, that the word "darkmans" is old thief cant for nighttime, Fingersmith is a thief and The Echo Maker comes from the Cherokee name for the birds, echo makers, calling to each other across the millennia. All of which makes The Echo Maker sound heavy-going - and occasionally it is but I'm afraid there's little excuse for the awfully forbidding title A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra. (Now with Extra Libris material, including a reader’s guide and bonus content from the author.) Apparently, it's far better than the title. I haven't read it, feeling cowed entirely by the intention stated in its title which is grander than Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time. (Did neither Marr's agent or editor not say to Anthony - mate, you might want to rethink the title?)

Gone are the 'Composed Atmospheric' titles, few are the Eponyms, au revoir to the Occupations, scarce are the Curious Elements from the book or Quotes from within.

Arise the Supermodel Solos, the Pseudo-Scientists, and the historical and cultural references which dunces like you won't know from your elbow. We have exhortations and instructional manuals to show you how to be good, or better, better. We have the definitive statement on common events or concepts. Clue - two words, begins with THE.

The Possessed, The Party, The Wake, The Sluts, The Afterlife, The Road, The Master, The Dinner, The Power.

Titles like Normal People or Ordinary People can be seen as versions of the author giving the 'definitive' statement on the matter.

In the literary set, we see the move from Eponyms, the name of the main character towards the addition of emphasis which during an era of population explosion underscores the fact that we are dealing with a particular person and not Everyman, (jack, woman or child.)

This trend is taken up with gusto a floor down from the penthouse in the thronging halls of the book store.

Names are not enough on their own, but must be given context or purpose - Life of Pi, The One and Only Ivan, The Story of Lucy Gault, A Man Called Ove, The Book of Polly, The Papers of Tony Veitch, We Need to Talk About Kevin, Lucy Sullivan Is Getting Married, Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks, Carry On Mr. Bowditch, The Lonely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, The Strange and Beautiful Sorrows of Ava Lavender ...

Let us go then, you and I, to the book store.

The Bestsellers of the Twenty-First Century.

“Harry Potter” by J. K. Rowling - Copies Sold: over 225M

“Robert Langdon” by D. Brown - Copies Sold: over 150M

“Fifty Shades of Grey (trilogy)” by E.L. James - Copies Sold: 125M

“Twilight (trilogy)” by S. Meyer - Copies Sold: 120M

“The Hunger Games” by S. Collins - Copies Sold: 65M

“A Song of Ice and Fire” by G. Martin - Copies Sold: 60M

“Divergent (trilogy)” by V. Roth - Copies Sold: 35M

“The Kite Runner” by K. Hosseini - Copies Sold: 31.5M

“The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” by S. Larsson - Copies Sold: 30M

“The Shack” by W.P. Young - Copies Sold: 22M

“Wolf Totem” by J. Rong - Copies Sold: 20M

“The Fault in Our Stars” by J. Green - Copies Sold: 18.5M

“The Shadow of the Wind” by C. F. Zafon - Copies Sold: 15M

“The Girl on the Train” by P. Hawkins - Copies Sold: 15M

“Interpreter of Maladies” by J. Lahiri - Copies Sold: 15M

“The Lovely Bones” by A. Sebold - Copies Sold: 10M

“The Book Thief” by M. Zusak - Copies Sold: 10M

“Life of Pi” by Y. Martel - Copies Sold: 10M

“Eat, Pray, Love” by E. Gilbert - Copies Sold: 9M

Notice that these combine accessible appealing elements and are not terribly complex or arcane for the most part. They span the clusters of the previous centuries - name, role, setting, a curious element within the book, and only the last is an exhortation.

We have seen that The Lovely Bones is a literary reference. Jon Green's bestseller's title comes from Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare, "The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, for we are underlings."

As for the Ten Bestselling Book Titles?

Don Quixote (Don Quijote) 500 million (Name)

A Tale of Two Cities 200 million (Social Commentary - see 19C here.)

The Little Prince 200 million (Contrived character - see 19C here.)

The Lord of the Rings 150 million (Contrived character - see 19C here.)

The Alchemist 65-150 million (Occupation - see 19C here.)

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone 120 million (Adventure - see 19C here.)

The Master and Margarita 100 million (Group adventure- see 19C here.)

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland 100 million (Adventure - see 19C here.)

The Hobbit 100 million (Contrived character - see 19C here.)

And Then There Were None 100 million (Previously published as a group adventure title.)

What Does This Mean for You and Your Title?

Start by owning your intention.

I'm going to say something about -

Someone who is rather loveable despite not being so at first glance (Name - natural or contrived and descriptor combination)

A romp or tale over many years with one main character - (The Adventures of Chronicles of, Mystery, Life and Times etc)

A time or place to which we can all relate (Reflective Meditation or Setting - the season or time or setting or place name - A Month in Summer or Brooklyn for example)

A change in perception and sense of belonging (psychological state - The Awakening.)

These formats are both large enough in scale and yet simple enough to have a broad-based appeal. Revise the options from the 19th Century, the first half of the 20th Century and the latter part of the 20th Century too.

Make sure you're in the right genre.

Reassure the reader that your intention (per your title) matches their interests, taking into account the genre you're writing. If it's a thriller, you'll be looking at the Situational titles for example. As we saw with Mr Prus, over 100 years ago, in the Nineteenth Century Titles blog, his success with The Doll was much diminished by a good but inappropriate title. Pore through these blogs for inspiration. You can find them side by side here.

The Sweet Spot.

We're here to help you hit the sweet spot from title to THE END with a novel that achieves commercial sales with literary credentials. In other words good stories, well-told.

At The Novelry, we focus on that sweet spot singlemindedly from the moment you join us and aim to deliver you to your promised land of a manuscript and a literary agent within a year. Ready for the year in which you change your routine from Eat, Pray, Love to The Golden Notebook? Join us.

January 18, 2020

Book Titles of the Later Twentieth Century.

In the first blog of the series, we saw the dominant form for the novel title prior to the Twentieth Century was the eponym - or the name of the main character of the story. In the last blog this series, we saw how the dominant form for the novel title in the Twentieth Century became the Reference; poetic or biblical. Perhaps they've given you inspiration for writing your own novel title as a statement of your literary purpose to guide writing our novel from the start?

Now we are going to look at the rise of other forms, one a cunningly disguised variant of the Reference, and the other the late Twentieth Century 'supermodel' of titles.

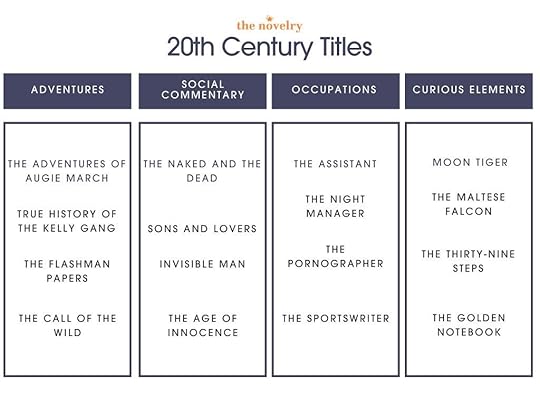

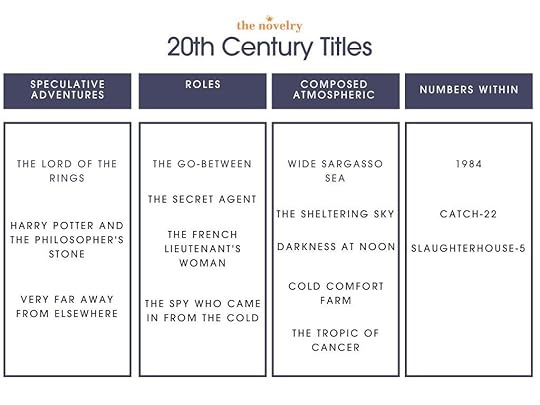

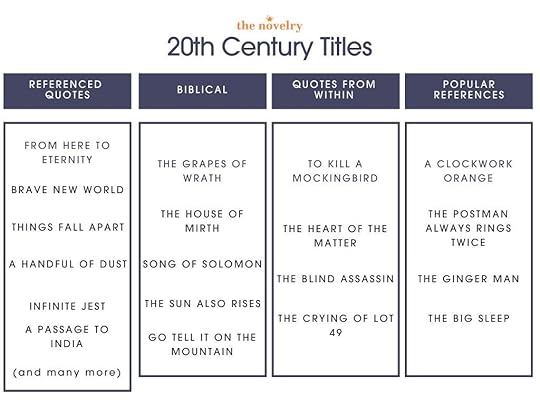

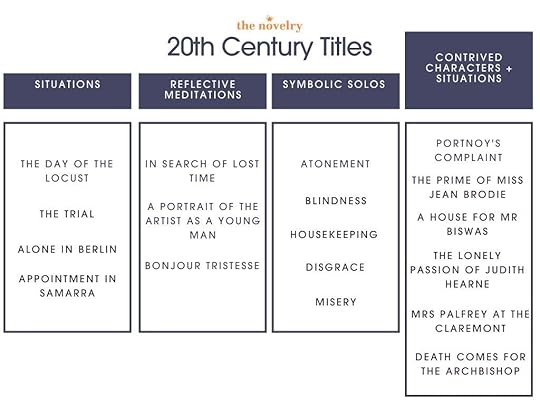

Here's a recap on how the widely acclaimed best novels of the Twentieth Century are titled - in clusters.

The Subversive Reference.

Robert Penn Warren's novel All the King's Men was published in 1946, and as we saw in the last blog, the title is derived from a low-brow source - Humpty Dumpty.

First titled "Sebastian Dangerfield," J.P Donleavy's book of 1955 was retitled "The Ginger Man". There are scores of guesses and is much speculation about the title, would-be meanings ranging from slang for male genitalia to the most commonly believed theory: a connection to the childhood tale of The Gingerbread Man, whose song, "Run, run, as fast as you can; you can't catch me I'm the gingerbread man" does seem to fit Dangerfield's journey in the novel.

One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest by Ken Kesey comes from a child's rhyme, which also serves as the epigraph. The epigraph reads "One flew east, one flew west, / One flew over the cuckoo's nest.

The low-brow or LO-FI reference is a rising trend in the Twentieth Century and will explain some of the titles you may have considered terribly creative.

The Big Sleep (1939) by Raymond Chandler is a gangster euphemism for death; the final pages of the book refer to a rumination about "sleeping the big sleep”.

One of my favourite titles, The Postman Always Rings Twice is from a 1934 novel by James M. Cain. The title is a red herring in that no postman appears or is even alluded to. The meaning of the title has often been the subject of speculation. William Marling suggested that Cain may have taken the title from the sensational 1927 case of Ruth Snyder, who, like Cora in Postman, had conspired with her lover to murder her husband. Cain used the Snyder case as an inspiration for his 1943 novel Double Indemnity; Marling believed it was also a model for the plot and the title of Postman. In the real-life case, Snyder said she had prevented her husband from discovering the changes she had made to his life insurance policy by telling the postman to deliver the policy's payment notices only to her and instructing him to ring the doorbell twice as a signal indicating he had such a delivery for her. The historian Judith Flanders, however, has interpreted the title as a reference to postal customs in the Victorian era. When the post was delivered, the postman knocked once to let the household know it was there: no reply was needed. When there was a telegram, however, which had to be handed over personally, he knocked twice so that the household would know to answer the door. Telegrams were expensive and usually the bringers of bad news: so a postman knocking twice signalled trouble was on the way. In the preface to Double Indemnity, Cain wrote that the title of The Postman Always Rings Twice came from a discussion he had with the screenwriter Vincent Lawrence. According to Cain, Lawrence spoke of the anxiety he felt when waiting for the postman to bring him news on a submitted manuscript, noting that he would know when the postman had finally arrived because he always rang twice. In his biography of Cain, Roy Hoopes recounted the conversation between Cain and Lawrence, noting that Lawrence did not say merely that the postman always rang twice but also that he was sometimes so anxious waiting for the postman that he would go into his backyard to avoid hearing his ring. The tactic inevitably failed, Lawrence continued, because if the postman's first ring was not noticed, his second one, even from the backyard, would be. As a result of the conversation, Cain decided upon that phrase as a title for his novel. Upon discussing it further, the two men agreed such a phrase was metaphorically suited to Frank's situation at the end of the novel. With the "postman" being God or fate, the "delivery" meant for Frank was his own death as just retribution for murdering Nick. Frank had missed the first "ring" when he initially got away with that killing. However, the postman rang again and this time the ring was heard; Frank is wrongly convicted of having murdered Cora and then sentenced to die.

Anthony Burgess explained thus the meaning and origin of the title for A Clockwork Orange (1962). He had overheard the phrase "as queer as a clockwork orange" in a London pub in 1945 and assumed it was a Cockney expression. In Clockwork Marmalade, an essay published in The Listener in 1972, he said that he had heard the phrase several times since that occasion. He also explained the title in response to a question from William Everson on the television programme Camera Three in 1972, "Well, the title has a very different meaning but only to a particular generation of London Cockneys. It's a phrase which I heard many years ago and so fell in love with, I wanted to use it, the title of the book. But the phrase itself I did not make up. The phrase "as queer as a clockwork orange" is good old East London slang and it didn't seem to me necessary to explain it. Now, obviously, I have to give it an extra meaning. I've implied an extra dimension. I've implied the junction of the organic, the lively, the sweet – in other words, life, the orange – and the mechanical, the cold, the disciplined. I've brought them together in this kind of oxymoron, this sour-sweet word." While addressing the reader in a letter before some editions of the book, the author says that when a man ceases to have free will, they are no longer a man. "Just a clockwork orange," a shiny, appealing object, but "just a toy to be wound-up by either God or the Devil, or (what is increasingly replacing both) the State.

The Supermodel Title: The Solo

Blindness was first used as a title by Henry Green for his first novel in 1926. Subsequently, he used the solo words to indicate a state of being in the world, reflecting the existential theories of the times and a solipsistic sense of man against machine perhaps.

Living (1929) Party, Caught (1943) Loving (1945) Back (1946) Concluding (1948) Nothing (1950) Doting (1952).

(The existentialists Sarte and Camus used single notion titles - Nausea, The Stranger, The Fall, The Plague.)

Doffing their hats to these perhaps, later more popular writers drew upon pre-Second World War philosophers when they used single (grand) concept titles.

In a way, one might see this a new version of leaning on literary references.

Deliverance (1970) James Dickey

Bliss (1981) Amnesia (2014) Peter Carey

Beloved (1987) Toni Morrison

Possession (1990) AS Byatt

Immortality (1990), Slowness (1995), Identity (1998), Ignorance (2000)- Milan Kundera

Everyman (2006), Indignation (2008) Philip Roth

Damage (1991), Sin (1992), Oblivion (1995) Josephine Hart

Disgrace (1999) JM Coetzee.

Atonement (2001) Ian McEwan

I dub this novel title form the Supermodel Solo as it's the author's grandstanding, it denotes the intention to give us a big work of philosophical importance and exactitude. It stands head and shoulders above other titles on the bookshop runway!

As the fortunes of literary fiction diminished in the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, so this form all but disappeared in favour of a more commercial form, implying a character-driven story given more page-turning appeal by the addition of an appealing or intriguing setting or the urgency of a problem of a tight spot - as we will see in the next blog. But here already are its origins: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Portnoy's Complaint, A House for Mr Biswas, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, Death Comes for the Archbishop.

I hope this is giving you plenty of thought for your own title but more importantly, that it's giving you the chance to consider your intentions for your novel-in-waiting.

The sooner you nail it, confess it, own it and write towards it the smoother your progress will be.

January 11, 2020

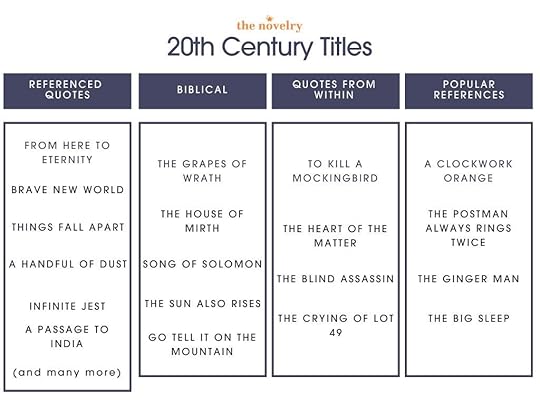

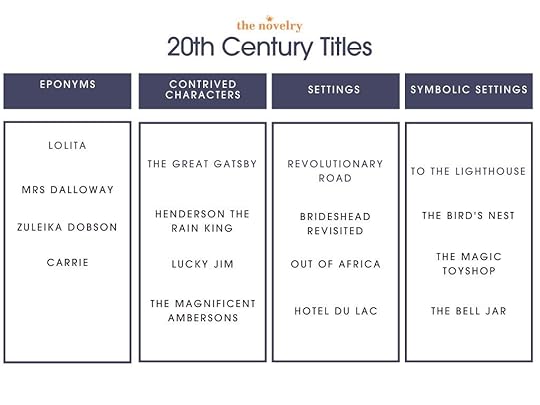

Book Titles of the Twentieth Century. How They Work.

In the last blog, we saw the dominant form for the novel title prior to the Twentieth Century was the eponym - or the name of the main character of the story. To an extent, this is reflective of the tacit understanding of the novel's purpose as form versus a play or a short story or a poem - as one person's moral or literal journey.

It's all change in the Twentieth Century!

In this first of two, we're going to look at the first half of the century, and in the next the end of the Twentieth Century as there's a sea change from the 1980's.

In the Twentieth Century the eponym is old news and almost gone.

Yes, there's a slightly broader range of 'statements of literary intention' but not so much as you might think.

In fact, the title form from 1900-2000 is dominated by one form.

The Reference. (The Deferential Doffing of the Author's Cap.)

The citation or quotation. A referential, deferential, preferential doffing of the hat either to the Bard, the poets, or to the Bible. (Plus one or two apparently surreal titles which hail from common parlance or slang.)

Among the commonly recognized top 100 novels of the century (I used a variety of sources - Time Magazine, The Guardian, The Modern Library and Goodreads) this is by far the most favoured form.

It is all far less inventive than we might expect of the Century in which the world shrank thanks to air travel and man walked on the moon, and titles of apparently surreal invention are in fact also hidden references as I will show.

So why all this dissembling and forelock-tugging in titles which suggests that a novel's purpose is to afford the author an entrée into the literary set. Why?

A grand canvas - the reference makes a universal timeless statement on the condition of the human spirit

Living room - the author confers upon herself or himself the space to explore a changing theme or multiple themes beyond one character's journey and suggests the intention to do so with the title

The title was given either post-operatively, and not always by the author but by the editor, a friend or spouse

The desire to belong to the literary set in shifting social classes, mass migrations and uncertain times

As my writers know, we begin our work together by examining your intentions. I remind my writers that a novel is a moral journey, and I make it super-simple by asking you to imagine - not to fix - the ending. The ending I propose to you is a temporary sense of belonging in the world for your main character.

So it is that in the Twentieth Century, we have evidence that many great authors saw the purpose of the novel as conferring upon author and subject 'a sense of belonging'. (There is of course, a costuming about it, a necessary fictional overcoating, a protective and defensive self-concealment.)

When we look at the range of novel title forms for the Twentieth Century, we will see that the 'morality' set-piece has gone. Gone is Crime and Punishment, Pride and Prejudice and Vanity Fair and instead we see the rise of 'psychological states' of awareness first seen with Kate Chopin's 'The Awakening' in the late 1890's, whereby the novel's purpose is a moral journey in the sense not so much of the reform of outer deeds (think Scrooge) as the awakening of new spiritual awareness, the place of the individual within the new societies and nature.

Gone are the 'Group Adventures' and many of the titles are haunted by a sense of lovely individuals in estranged psychological settings, states and situations.

In addition to the place settings of the novel present as a form previously, we see a growth in the number of titles which posit a situation that places the main character in a tight spot. From a broad regional canvas such as American Pastoral or American Tragedy the titles become more specific in terms of location - A High Wind in Jamaica, Tobacco Road, Revolutionary Road, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, A Bend in the River, Hotel du Lac... A Room with a View.

There are more 'curiosities from the novel' afoot in novel titling. To Kill a Mockingbird was the second choice title after Go Set a Watchman (which is a Biblical reference from Isaiah 21:6) and is a reference to the loss of innocence in the novel. In fact my cluster dubbed 'Numbers' are curiosities from within those novels, but I clustered them apart as I find titles with numbers in them have an interesting an eye-catching authority and appeal.

The social commentary form I described in last week's blog, with its purpose to show the range between two elements in conflict is still here, but harder to find.

More apparently creative than many, Norman Mailer's title for the war story he wrote aged 25 'The Naked and the Dead' shows a small range of exquisite suffering. "The natural role of the twentieth-century man is anxiety," as he put it. Mailer described how his writing inspiration came from the great Russian novelists like Leo Tolstoy. He said he'd "write twenty-five pages of first draft a week." He felt that this novel was the easiest for him to write, as he finished it quickly and passionately. “Part of me thought it was possibly the greatest book written since War and Peace.” While writing, Mailer read from Anna Karenina most mornings before he commenced work. (This is a technique I formalise with my writers via the Hero Book element of the Ninety Day Novel course.) Yet in Job 1: 21 the idea of entering the world naked and leaving it so is given.

For three-quarters of the Twentieth Century the reference has hegemony. The Great Gatsby, as we have seen in an earlier blog, had a precursor title which referenced a poem by Thomas Parke D'Invilliers.

Broadly the referential novel title form falls into two categories - Biblical or Poetic (But there's a surprise third - and as you will see this explains many of the titles apparently belonging to other categories.)

Biblical.

So many! The Sun Also Rises, The Song of Solomon, The Power and the Glory... Lord of the Flies (William Golding) is a literal translation of Beelzebub, from 2 Kings 1:2–3, 6, 16. The Way of All Flesh by Samuel Butler The title is a common misquotation of a Biblical Hebrew expression, to "go the way of all the earth", meaning "to die" (1 Kings 2:2.)

The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck's wife, Carol Henning, suggested the title to Steinbeck. The phrase ''grapes of wrath'' is from the Book of Revelation, passage 14:19-20, which reads, ''So the angel swung his sickle to the earth and gathered the clusters from the vine of the earth, and threw them into the great wine press of the wrath of God.'' But here is a second source that the title is a reference to, and this one is the famous song ''The Battle Hymn of the Republic'' (1861). Because the song was written in the context of American history and politics, it connects to The Grapes of Wrathpredicting the end of evil and coming of justice. The opening stanza references the biblical passage, but this time it uses the actual phrase ''the grapes of wrath,'' which gives it a more obvious connection to the novel's title. It reads:

''Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on.''

House of Mirth. Edith Wharton considered several titles for the novel about Lily Bart; two were germane to her purpose. A Moment's Ornament appears in the first stanza of William Wordsworth's (1770–1850) poem, "She was a Phantom of Delight" (1804) that describes an ideal of feminine beauty. But the title Edith Wharton chose for the novel was The House of Mirth (1905), taken from the Old Testament:

The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning; but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth.

— Ecclesiastes 7:4

"Mirth" contrasted with "mourning" also bespeaks a moral purpose as it underscores the frivolity of a social set that not only worships money, but also uses it ostentatiously solely for its own amusement and aggrandizement. Wharton revealed in her introduction to the 1936 reprint of The House of Mirth her choice of subject and her major theme:

"When I wrote House of Mirth I held, without knowing it, two trumps in my hand. One was the fact that New York society in the nineties was a field as yet unexploited by a novelist who had grown up in that little hot-house of tradition and conventions; and the other, that as yet these traditions and conventions were unassailed, and tacitly regarded as unassailable."

The Day of the Locust by Nathaneal West. The original title of the novel was The Cheated. Susan Sanderson writes "The most famous literary or historical reference to locusts is in the Book of Exodus in the Bible, in which God sends a plague of locusts to the pharaoh of Egypt as retribution for refusing to free the enslaved Jews. Millions of locusts swarm over the lush fields of Egypt, destroying its food supplies. Destructive locusts appear in the New Testament in the symbolic and apocalyptic book of Revelation." West's use of "locust" in his title evokes images of destruction and a land stripped bare of anything green and living. The novel is filled with images of destruction.

Go Tell It On the Mountain, the title of James Baldwin’s book, is a reference to the gospel song a popular Christmas carol because its lyrics refer to Jesus Christ's birth.

Poems. From the Sublime to the Ridiculous.

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh comes from "The Waste Land" by T.S. Eliot:

I will show you something different from either Your shadow at morning striding behind you Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe is from "The Second Coming" by William Butler Yeats.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre, The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald comes from "Ode to a Nightingale" by John Keats.

Already with thee! tender is the night, And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne, Cluster'd around by all her starry Fays But here there is no light, Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

A Passage to India by E.M. Forster is not so much a location-based title after all! It comes from Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

Passage to India! Struggles of many a captain-tales of many a sailor dead! Over my mood, stealing and spreading they come, Like clouds and cloudlets in the unreach'd sky.

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner comes from Homer’s Odyssey, Book XI. Odysseus has travelled to the Underworld, essentially to get directions. Once there, however, he’s bombarded by the ghosts of all his dead comrades, Agamemnon tells the story of his own death.

"As I lay dying, the woman with the dog's eyes would not close my eyes as I descended into Hades."

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck comes from Robert Burns "To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest with the Plough".

But little Mouse, you are not alone, In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes of mice and men

Go often askew, And leave us nothing but grief and pain, For promised joy

Remembrance of Things Past by Marcel Proust comes from "Sonnet 30″ by William Shakespeare.

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste

Endless Night by Agatha Christie is from "Auguries of Innocence" by William Blake.

Every night and every morn, Some to misery are born, Every morn and every night, Some are born to sweet delight. Some are born to sweet delight, Some are born to endless night.

From Here to Eternity by James Jones. The title was inspired by a line from Rudyard Kipling's poem "Gentleman Rankers"

Gentlemen-rankers out on a spree,

Damned from here to Eternity,

God ha' mercy on such as we,

Baa! Yah! Bah!

For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway is from "Meditation XVII" by John Donne.

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers is from "The Lonely Hunter" by William Sharp.

O never a green leaf whispers, where the green-gold branches swing: O never a song I hear now, where one was wont to sing. Here in the heart of Summer, sweet is life to me still, But my heart is a lonely hunter that hunts on a lonely hill.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou comes from "Sympathy" by Paul Laurence Dunbar.

It is not a carol of joy or glee, But a prayer that he sends from his heart's deep core, But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings -- I know why the caged bird sings!

The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold comes from "I Knew a Woman" by Theodore Roethke.

I knew a woman, lovely in her bones, When small birds sighed, she would sigh back at them; Ah, when she moved, she moved more ways than one: The shapes a bright container can contain!

Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace derives its name from a line in Hamlet, in which Hamlet refers to the skull of Yorick, the court jester. (Wallace's working title for Infinite Jest had been A Failed Entertainment.)

"Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how abhorred in my imagination it is!"

Do you see how much loftier his title sounds once it's garbed in the cloak of the Bard? Somerset Maugham borrowed the philosopher's gown...

Of Human Bondage was initially called The Artistic Temperament of Stephen Carey, then Beauty from the Ashes, a quotation from Isaiah. When Maugham discovered that this title had been used already, he borrowed his final title from one of the books in Spinoza's Ethics "Of Human Bondage, or the Strength of the Emotions".

More ridiculous perhaps than sublime, Robert Penn Warren took the title, All the King's Men from the famous nursery rhyme Humpty Dumpty and this is the clue I will leave you with that will go some way to unlocking the more deceptively 'creative' innovative and surreal titles of the era and in the next blog, I will show you the rise of the supermodel of novel titles in the last quarter of the Twentieth century.

Most of the novel titles of the Twentieth Century thus far are out of the dressing up box; a way of belonging, and their purpose - explicit or implicit - to tell a story about how on earth we as individuals finds our sense of belonging in this changing world.

Confession.

I will confess I have spent many happy hours browsing Hamlet, Keats' poems. Yeats and more in search of candidate titles for my current novel whose title changes daily, since it is hard for me to admit the theme as it would be rather offputting I think served on a plate without sauce. Presently I'm using a quote which doesn't sound like a quote!

As for my other novels:

Becoming Strangers - the two axes used in the social commentary form and a paradox. The title came after the writing of the novel. One reviewer for The Independent hated it. It's since been nabbed by another writer, I hope as a literary reference ;-)

This Human Season - I had the title early on. The only novel of mine where this was an early factor and by far the most agreeable and certain writing process. No coincidence. It's about the inclination of young men, in the springtime of their lives, to want to fight (infantry.) I use it in the book.

(Graham Greene uses 'The Heart of the Matter' in his novel. "If one knew, he wondered, the facts, would one have to feel pity even for the planets? If one reached what they called the heart of the matter?” DH Lawrence refers to The Rainbow at the end of the book, whenhaving failed to find her fulfilment in Skrebensky, Anna has a vision of a rainbow towering over the Earth, promising a new dawn for humanity; "She saw in the rainbow the earth's new architecture, the old, brittle corruption of houses and factories swept away, the world built up in a living fabric of Truth, fitting to the over-arching heaven.”)

The Italian edition of This Human Season is La Primavera Dell'Odio which sounds like a nice pizza.

The Idea of Love. That the idea is not the reality.

The Old Romantic. The title came after the writing. It's a nod to the sentimental old fool who is the focal point of the story and thus the title probably fits into the 'role' category.

January 4, 2020

Book Titles. How They Work.

Welcome to Titology, or the study of titles.

In this short series of blogs on the origins of novel titles, I will perform a rude taxonomy to classify the species. For my roll call I'm using a combination of the bestselling, best-regarded 'Top 100 Novels' lists from the UK and the USA.

A title is a statement of literary intention.

As a form in itself it has become increasingly nuanced over time, but it's still possible to decipher the motives and meanings behind titles, and quite fascinating. Once armed you can title your book with confidence and sharpen your creative intentions. When we know what we're doing, as authors, we tend to do it rather well. When we don't we tend to do it rather badly. Post-rationalising your intentions in multiple drafts of a novel is a bore, as I described in the last blog.

Now, the modern novel is considered to have started in 1605 with The Ingenious Nobleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes better known as Don Quixote.

"If there is one novel you should read before you die, it is Don Quixote," Ben Okri said at the Nobel Institute as he announced the results of their 2002 authors' poll of best novels of all-time "Don Quixote has the most wonderful and elaborated story, yet it is simple." Don Quixote came top of the list among voters including Doris Lessing, Salman Rushdie, Nadine Gordimer, Wole Soyinka, Seamus Heaney, Carlos Fuentes and Norman Mailer.

"In the whole world there is no deeper, no mightier literary work. This is, so far, the last and greatest expression of human thought; this is the bitterest irony which man was capable of conceiving. And if the world were to come to an end, and people were asked there somewhere: "Did you understand your life on earth, and what conclusions have you drawn from it?" man could silently hand over Don Quixote." Dostoyevsky.

Thus the long-form story of the novel began with the name of its main character. As many of my writers on our novel-writing course know, a novel is essentially a moral journey.

The Eponyms. The use of the main character's name as the preference for the titling of a novel continued throughout the 17th and 18th Centuries through Barry Lyndon, Gulliver's Travels, Candide, The History of Tom Jones, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Moll Flanders, Fanny Hill, Amelia, Camilla, Cecilia, Clarissa, Justine, Pamela, to Robinson Crusoe. During this period, the name was chosen to be realistic.

It was still the preferred mode for titling a book in the Nineteenth Century until we get to Dickens where the names infer character and are sometimes chosen for alliterative play - from Oliver Twist to Nicholas Nickleby. Dickens took the same approach to place names with invented locales to infer his theme as with Bleak House.

We begin to see the increasing humour and whimsy of description of the main character as an addition to the name - harking back to the sometimes omitted The Ingenious Nobleman Don Quixote - which give notice to the reader of the narrative style they might expect inside with additional descriptors of 'adventures' or 'history' 'portrait' or 'mystery.' We can see the 'mood' in the contrivance beginning perhaps with Wuthering Heights.

The use of a name infers that this particular person is somehow distinct or worthy of note. This is particularly pertinent pre-Twenty-first century where the name is female. This, says the author, is a woman unlike others; Anna Karenina, Mary Barton, Emma and so on. She is of note, unlike others.

In modern times, being a woman worthy of a novel does not require such distinction and eponymously titled female novels (without descriptors) tend to be quieter and less of an adventure or pageant wrought on a smaller canvas.

The addition of the descriptor - like the Ingenious Nobleman - was taken up again in the Twentieth Century, when after a proliferation of eponymously titled novels a person worthy of a novel did not make that person distinctive per se perhaps but with the rise of consumerism the additional descriptor supplied commercial 'audience' intent - well, look at this chap! (The Great Gatsby.)

The recent taste for the novel titles of the popular Up Lit genre (A Man Called Ove, Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry) returns to the convention that the story is the main character's moral journey.

We will come onto the twentieth century in the next blog, but for now, note how contrary to expectations, the other novel titles were not referential (poems, Biblical quotes) but worlds in themselves. They are statements on the business of moral improvement or the conditions of the world, and faithful to the author's intentions and to the readers' predilections or interests. The Victorian ambition is bold.

We are able to get a glimpse of the author's intention by looking at these title clusters. The reader would have had a clear steer too. (By the way, I start work with my writers by asking them to declare their intentions so that we have a stable base for the instable business of writing. We fix our destination from the off.)

Working on a larger social canvas, some writers deploy a witty 'connective' between two apparently opposing forces to show the range they intend to cover. From Stendhal's The Red and the Black, through to Tolstoy's War and Peace, Gaskell's North and South, Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment and onwards to DH Lawrence's Sons and Lovers later. (In contrast, a title like Tony Parson's 'Man and Boy' (2001) does not offer such a broad scale juxtaposition thus its worldly range is more narrow; a smaller book, a product of individualist times.)

Thomas Hardy was quite an innovator and the title of his first published novel is quite striking for the times - Desperate Remedies (1871). Its intention seems to fit within the 'morality' cluster above. His second novel Under the Greenwood Tree (1872) is location-driven. Thomas Hardy's third novel (1874) Far From the Madding Crowd is an exception to the rule; it references a poem. It comes from "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" by Thomas Gray:

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife.

Their sober wishes never learn'd to stray;

Along the cool sequester'd vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.