Louise Dean's Blog, page 22

September 10, 2017

Painting by Punching. (The Knockout Novel.)

Perhaps you're working too finely, that's all well and good when you're laying down a first draft with uncertainty but when you've got wind of your story you need to land a few blows on the 'characters' in your work in progress.

Let insults pelt the page, and injuries accrue upon the person leaving behind a dense impression of a life being lived the way we live them - in suffering - punctuated with occasional rare joys.

Look at your 'main character' the person pushing your novel and see a slow-moving morass of personable misery. Suited. Booted. Custom made, their plight tailored to them by your prose. We want to see the lumpen shape of slow-moving misfortune. Your job is to wound him or her, in order to get them to wake up and live the life they've been given against their wishes.

Annie Proulx's Pulitzer Prize winning 'The Shipping News' delivers a masterclass in 'character' creation via the hapless, gormless, Quoyle. By the second page, we have this monstrosity still-born and walking:

'Quoyle shambled, a head taller than any child around him, was soft. He knew it. "Ah, you lout," said the father. But no pygmy himself. And brother Dick, the father's favorite, pretended to throw up when Quoyle came into a room, hissed "Lardass, Snotface, Ugly Pig, Warthog, Stupid, Stinkbomb, Fart-tub, Greasebag," pummeled and kicked until Quoyle curled, hands over head, sniveling, on the linoleum. All stemmed from Quoyle's chief failure, a failure of normal appearance.

A great damp loaf of a body. At six he weighed eighty pounds. At sixteen he was buried under a casement of flesh. Head shaped like a crenshaw, no neck, reddish hair ruched back. Features as bunched as kissed fingertips. Eyes the color of plastic. The monstrous chin, a freakish shelf jutting from the lower face.'

If you've been patient with your 'character' thus far, it's maybe time for your patience to run out.

If your book's carrying deadweight, if it's flat and listless, it's his or her fault.

Use your prose to pummel, insult, perturb, embarrass, deny, abuse and kick your character from page to page. Put your petty and painstaking brush away and use your fists. Get rough with your subject, bully, cajole, push, surprise them but have them live the goddam life you've given them. Please be rude. Your book will be the better for it.

By the second chapter of The Shipping News, Quoyle has found love and been disabused of it's majesty too.

“It was not Quoyle’s chin she hated, but his cringing hesitancy, as though he waited for her anger, expected her to make him suffer. She could not bear his hot back, the bulk of him in the bed. The part of Quoyle that was wonderful was, unfortunately, attached to the rest of him. A walrus panting on the near pillow. While she remained a curious question that attracted many mathematicians.

‘Sorry,’ he mumbled, his hairy leg grazing her thigh. In the darkness his pleading fingers crept up her arm. She shuddered, shook his hand away.

‘Don’t do that!’

She did not say ‘Lardass,’ but he heard it. There was nothing about him she could stand. She wished him in the pit. Could not help it any more than he could help his witless love.

Quoyle stiff-mouthed, feeling cables tighten around him as though drawn up by a ratchet. What had he expected when he married? Not his parents’ discount-store life, but something like Partridge’s backyard – friends, grill, smoke, affection and its unspoken language. But this didn’t happen. It was as though he were a tree and she a thorny branch grafted onto his side that flexed in every wind, flailing the wounded bark.

What he had was what he pretended.”

By the second chapter, a lifetime subscription to misery has been granted him, unless the author and the reader working together can do something about it. Here is your reason to read on - using the full force of your compassion alongside the author's you can change this world of pages and maybe more.

Don't ask why you're writing a novel any further; this is why - humanity's sake. Because you're here.

Be cruel to be kind. After all it is only in real life that people get let alone to lead easy lives, in novels they get picked on, sullied, harried, battered, degraded, ruined and saved.

'What he had was what he pretended.'

You can write like Annie Proulx. You just need to work harder. Here's how:

Since 1975, when Annie Proulx left a Ph.D. program in history at Concordia University, she has been writing full time; she rarely lives in the same place for more than a few years. She has been married, she says, “too many times,” and has four grown children. Proulx was in her fifties when she published her first short-story collection, Heart Songs(1988), but since then she has worked steadily, publishing four novels and three more story collections. Proulx tackles bleak themes with a sharp sense of humour and a master stylist’s sense of language— ‘the pill is never wholly bitter’ (Paris Review 2009).

Her first novel, Postcards (1992), begins in Vermont, but it eventually comes to cover the entire country, following its central character, Loyal Blood, through a lifetime of odd jobs after he flees his family’s dairy farm. The novel won the PEN/Faulkner award. She won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for her next novel, The Shipping News (1993), a look at Newfoundland and the men and women cast adrift by the collapse of the fishing industry there.

Proulx considers her short stories to be a greater accomplishment than her novels. Her sentences are built by precision engineering. There is the same ‘flashlight’ approach to her depictions as we have seen in Kerouac, but the story is more solid, and driven by the plight of the persons in it (‘the main character’.)

On character names:

‘Sometimes they come halfway along, sometimes names get changed six or seven times. I keep a book full of names and keep adding to it… the reason I put out-of-the-ordinary names on characters is because the John Smiths of the literary world make me sick—Bob and Bill and Joe and Nancy and Sandy and Fanny and so forth. I started using distinctive names as a mnemonic device for readers.’

Storytelling and Social Issues:

‘Storytelling trumps social issues. As I said, I’m primarily a reader, so of course I try to make the stories I write interesting and entertaining. I don’t write to inspire social change, but I do like situations of massive economic or cultural change as a background. We think of change as benign, but it chews some people up and spits them out. And fiction can bring about change.’

Process:

‘It starts with a lot of research, and an ending, which I write first. I write to the end.’

Do you write longhand?

‘Yes. Then after a certain amount is done, I put it on the computer because it’s so easy to switch things around. And then I start printing out drafts and adding in emendations and constructions and marginal notations and drawings and arrows and x’s and scribbles and that sort of thing.’

How do you know when a story is finished?

‘It is impossible to answer. You just know. I suppose it’s the thing Hemingway referred to as the built-in shit detector. I think one develops a built-in shit detector through wide reading of other people’s work. And if you can’t see the ghastly bits in your own writing you shouldn’t be a writer.’

About being a writer:

‘I never thought of myself as a writer. I only backed into it through having to make a living. And then I discovered that I could actually do it. I thought there was some arcane fellowship that you knew at birth that you had to belong to in order to be a writer.’

Do you think you had a late start when it comes to writing fiction?

‘Well, I did, yeah. But so what? Why should it bother anybody when somebody starts to write? …The world is spared lots of crap.’

On the work Itself:

‘There is difficulty involved in going from the basic sentence that’s headed in the right direction to making a fine sentence. But it’s a joyous task. It’s hard, but it’s joyous. Being raised rural, I think work is its own satisfaction. It’s not seen as onerous, or a dreadful fate. It’s like building a mill or a bridge or sewing a fine garment or chopping wood—there’s a pleasure in constructing something that really works.’

You know it's hard work, you're not surprised by that because you're working alongside 60 other novelists at Kritikme so you're sharing the experience, it's ups and downs, but make it harder, make it harder for your character and give us all a way through what we all know is going to get harder yet: this life.

September 4, 2017

Tense? Point of View?

My writers often ask about first or third person, past or present tense and all the wonderful variations of those.

One of my favourite books of all time, and Mr Graham Greene's too, is Ford Madox Ford's 'The Good Soldier.'

The clue is most certainly in the title. 'The Good Soldier' is meant as in 'the good sort' or 'the good egg'. It's sly.

Ford Madox Ford writes as 'I' with what turns out to be knowing 'melancholy' about an event in the recent past, and the self-pity is pure cyanide.... it could not have been written in present tense, because he is an unreliable narrator.

He begins the book with formidable élan, unreliably, apparently with heartfelt poignancy. "This is the saddest story I have ever heard."

As Julian Barnes put it 'What could be more simple and declaratory, a statement of such high plangency and enormous claim that the reader assumes it must be not just an impression, or even a powerful opinion, but a "fact"? Yet it is one of the most misleading first sentences in all fiction. This isn't - it cannot be - apparent at first reading, though if you were to go back and reread that line after finishing the first chapter, you would instantly see the falsity, instantly feel the floorboard creak beneath your foot on that "heard". The narrator, an American called Dowell (he forgets to tell us his Christian name until nearly the end of the novel) has not "heard" the story at all. It's a story in which he has actively - and passively - participated, been in up to his ears, eyes, neck, heart and guts. We're the ones "hearing" it; he's the one telling it, despite this initial, hopeless attempt to deflect attention from his own presence and complicity. And if the second verb of the first sentence cannot be trusted, we must be prepared to treat every sentence with the same care and suspicion. We must prowl soft-footed through this text, alive for every board's moan and plaint.'

In the Novel in 90 Plan, I ask my writers from the outset of planning their novel to begin by considering the magic trick they are about to perform, to make a pledge to the reader from the opening gambit and to be seen to 'deliver' upon it. But magic is sleight of hand. It's sly, and it beggars belief, because we are being made to look in the wrong place.

'My wife and I knew Captain and Mrs. Ashburnham as well as it was possible to know anybody, and yet, in another sense, we knew nothing at all about them.'

The reasoned tone of voice gains our trust within the first paragraph of the novel, but it turns out they knew a lot about Captain and Mrs Ashburnham and more than was fair.

If your narrator is unreliable in the telling of his or her tale, past tense is right.

If he or she is leading us 'live' down a garden path, possibly unwittingly as a bit of a dope, proceeding one might hope for a novel is a moral journey if not a literal one towards an awakening, then present is right.

In my work in progress, the narrator goes between present and past, in the former where she is becoming aware of herself and is a bit of a dope (!) and in the second, where she is telling a yarn to someone else which may or may not have happened as she describes it.

Enjoy not only the magic of your novel, but the music.

"Music heard so deeply

That is not heard at all,

but you are

The music

While the music lasts."

T.S Eliot.

August 24, 2017

The Big Easy. (That folksy first line, thanks to the Yanks.)

Relax. Take the pressure off yourself as a writer, and relax the reader too. Invite'em in. Go on. Make them at home. Give them the easy chair, the one with the stained cushion and the crumbs in the corner.

Why don't you kick off that novel by kicking back?

The American tradition is especially good at this from Mark Twain to last year's Man Booker Prize Winner Paul Beatty.

Let me take you, as we like to do at Kritikme, to a warm, safe place where you can feel at home, and invite the reader in. If some of these opening sentences from novels of the American cannon feel like easy-listening to you, then that's just the point.

'You don’t know about me, without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by a Mr Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly.' Mark Twain. (1884)

'In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I've been turning over in my mind ever since.' F. Scott Fitzgerald. (1925)

'Elmer Gantry was drunk.' Sinclair Lewis. (1926)

'In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains.' Ernest Hemingway. (1929)

'If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.' JD Salinger. (1951)

'I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up.' Jack Kerouac. (1957)

'It was love at first sight.' Joseph Heller. (1961)

'If I am out of my mind, it's all right with me, thought Moses Herzog.' Saul Bellow (1964)

'All this happened, more or less.' Kurt Vonnegut. (1969)

'You better not never tell nobody but God.' Alice Walker. (1982)

'The first thing I remember is being under something.' Charles Bukowski. (1982)

'It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.' Paul Auster. (1985)

'Some real things have happened lately.' Joan Didion. (1996)

'He speaks in your voice, American, and there’s a shine in his eyes that’s halfway hopeful.' Don DeLillo. (1997)

'It began the usual way, in the bathroom of the Lassimo Hotel.' Jennifer Egan. (2011)

'I suppose that's exactly the problem - I wasn't raised to know any better.' Paul Beatty. (2015)

And if it looks to you like yet again this list is mostly men, then that's because hitherto men had time to write where women didn't. Kritikme is changing that. Most of the Kritikme novelists at work are women. Probably because Kritikme teaches you how to write a novel now, not one day when everything's perfect. Because that day won't come. So the method is how to make your busy life work for your writing. You'll need an hour a day and a hell of a busy life, because as many full time writers know, the pressure and lack of time helps. Not to mention a great emotional attachment to your novel, which is something I get you to find and tune into daily with Kritikme. That's why it's so popular with women writers. It's disruption if you like, a big push back against the old days and the old ways, and an effective/kickass way of getting our stories down.

And my own first novel's opening sentence? (From 'Becoming Strangers' written in 2001 in America...)

'Before he'd had cancer he'd been bored with life.'

My own favourite first lines?

'I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I think my liver is diseased.' Dostoyevsky. Notes From Underground. (1864)

'Of course I have not always been a drunkard.' Hans Fallada. The Drinker. (1950)

And, above all else, a line that can never be repeated sadly, because he owns it; Ford Madox Ford 'The Good Soldier' (1915) :

'This is the saddest story I have ever heard.'

So come on, what's your own opening line or your best beloved line of all time? Share below!

August 21, 2017

August 20, 2017

Home Retreat Week

ANNOUNCING a new feature of the Kritikme Autumn Plan for members of Kritikme:

HOME RETREAT WEEK.

Here's how it works:

1. Book a week off work October 1-7

2. Put in a good four hours daily Monday - Friday that week (no need to rise at dawn on this week!)

3. There will be a Kritikme embargo on social media before 5pm so no need to check Facebook etc before then surely? ;-)

4. Personal Tutoring Plan members can book in an hour with me between 5-8pm daily

5. Evensong at Eight. There will be an evening Team Chat every day to focus the mind, share the ups and downs and get fast acting relief! (Mon, Tues, Weds, Thurs, Fri.)

Evensong is open on a first to reserve basis to all Novel in 90 and Personal Tutoring plan members with a live and current subscription and those with a membership for the Members Lodge at Kritikme.

The week will conclude with cocktails in London on Saturday 7th at Waterstones Piccadilly.

You should be able to tuck in upwards of 10,000 with a week like that for a first draft and get along way with your second draft sort out too.

Remember to warn friends and family that you're home alone writing, use your Kritikme 'non-greetings cards' if necessary and issue 'do not resuscitate' orders to your nearest and dearest.

How I wrote my novel with Kritikme - by Cate.

I've started many books over the years but, until today, I'd only finished one. That one came from an MA in Creative Writing and took nearly two years to write. After I'd finished I sent it off to agents and publishers and got some nice comments on my writing, but no enthusiasm at all for the book. I knew it was flawed but didn't know how to fix it.

A little while later I started another. This one was going to be the one. It had a cracking premise and a protagonist I really cared about. I took a synopsis and three chapters to a Writers' Workshop conference in York and got really positive feedback from three agents. One wanted to see it as soon as I had finished. But I couldn't finish it. I got stuck somewhere around the middle and stayed stuck for a year. Then I read a review in the Sunday Times of my book. Same premise, same setting, same main character name for God's sake!

I wallowed for another year, flip-flopping between writing mine anyway and throwing it away. My son was doing his A-levels so I announced that I wasn't writing for a year, sick of the guilt that not writing brings.

Finally I started another book, joined a course at City Lit to make me write it, and got stuck again. Broke all the promises I'd made about writing it quickly this time. I sat becalmed for long enough to convince myself I didn't know what I was doing. If I couldn't even decide if my protagonist was 25 or 55, how could I put her in a book? Maybe that thing I'd wanted to be all my life - literally since I was old enough to know there were writers I'd wanted to be one - was not for me?

But I had another idea - another one that in theory should practically write itself. Did I mention I'm an optimist? I bought a notebook - it always starts with a new notebook - and noodled about in it.

Mslexia plopped onto my doormat, and I stopped to read it. Right at the end was a tiny article about Louise Dean and Kritikme. I went straight to the website, read about the Novel in Ninety course and signed up on the spot.

I cleared off my desk to make a space for me alone, surrounded by things I like to look at. On the shelf above it I lined up the books Louise mentioned in her reading lists, plus a few hero books of my own.

I was itching to start in earnest, and held off as long as I could. I bought a Moleskine notebook, unlined per Louise's advice, and opened my mind to the wonders of a truly blank page.

Getting up was easy - though I confess I set my alarm for 6, not 5. I started on 4 June and needed only to raise the blind to light my page.

I opened each morning post like a Christmas present, thrilled by how often Louise's notes would answer a something I'd thought of a day or two before. I used the posts to wake me up, reading them at my desk with a mug of tea.

Then I'd close my iPad, pick up my pen (black uni-ball eye needle micro, since you ask) and write. It was episodic to begin with - any scene I could imagine. After the first month it became more linear, with one chapter following on from the day before. I wrote each day for an hour or 90 minutes - averaging six pages of double spaced handwriting - around 900 words. I'd be done by 7.30 most mornings. Then I'd go on with my day, doing other things but carrying my book in my head. Best of all I wasn't feeling guilty about not writing, because I was! I never got stuck. There was only one day I didn't write at all, but that was very near the end and I was making notes instead.

Morning is a magic time, and I felt the process was almost mystical. I had a panic just over a week ago about the end, but a call with Louise soon set me straight.

And now I'm done. There's a lot of "finishing" to do, but I've laid down a first draft within the promised time. I know it benefits from having been written in one go - my characters are more consistent for a start. The funny thing is I don't particularly care what happens to it. I'll keep working on it and make it as close to a "real" book as I can, but if nobody wants to take it up that's okay. Because I know I can always write another one. All I need is a new Moleskine, and 90 days.

And Louise and Kritikme at my back.

August 19, 2017

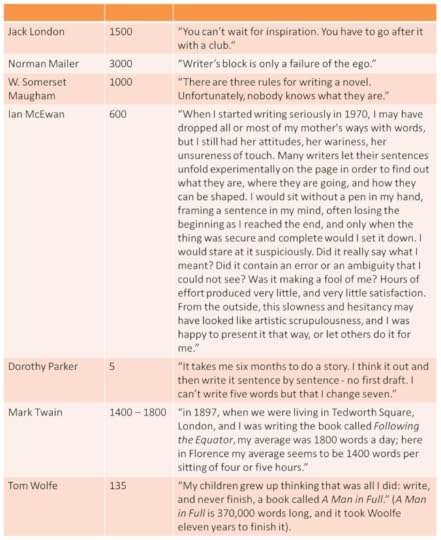

Everything you wanted to know about your plot but were afraid to ask (yourself.)

Whether you're starting to consider your story, or reconsidering it's merits for a second draft, you'll want to check a few things are in place.

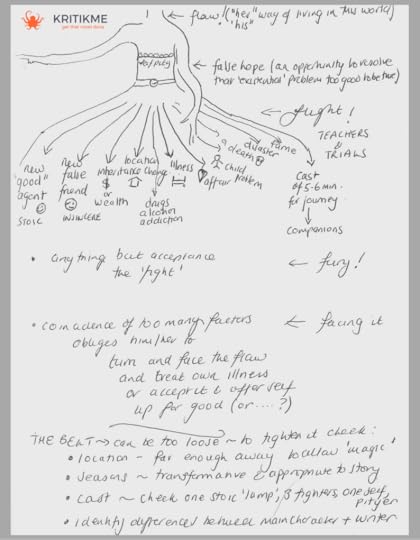

Some of you will be familiar with the Five F's Kritikme Structure for a novel which is a re-working of Aristotle's Poetics and seen again and again in most great novels. If not, it is summarised here as Flaw, False Hope, Flight, Fury and Facing it.

Your novel will begin by establishing the common understanding between the writer and reader that the the main character's Flaw - their way of coping with the burden of their particular life - is a problem to be resolved, as yet unresolved ("For a man of his age, 52, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well" - the opening sentence of Coetzee's Disgrace is perfect in this regard opening up the opportunity of the novel, to show that his solution is imperfect.)

You will proceed to mire the character in the problem offering False Hope, a false solution, but then, dear writers either in first draft or second, you may encounter a big gulp of a problem. A bottle neck or as I call it the belt that's too slack or too tight.

You have multiple options next to offer your character per most mythological tales and fairy tales - teachers and trials - to drive your character deeper into the woods of their existential woes, until they have no option but to turn and face themselves.

Now, at 'the belt' you need to double check these elements of your story so that you can write it with passion:

the location - is it far enough away from you to see it with electric 'holiday' eyes and partially create it to be true to your vision for the novel

the season - are you telling the parts of the novel or the whole of it in a season that works with your story to enhance it's magic for you and the reader

the cast - have you got the right people in place now you're at the 'belt' to accompany your hero or heroine through trials, perhaps one or two of them will be a teacher (remembering that 'my enemy' is also 'my teacher.) Have you got a stoic, lamp-like, warm presence perhaps? A few 'fighters'. A comedic clown element perhaps. And of course your antagonist, though he or she may come and go.

the identity of your main character - we do a lot of work on this element - but have you noted and written down in what ways your main character is different from you?

If you're stuck, double check these elements, remember per our old friend Nabokov to keep throwing rocks at the main character such that the options for 'what happens next' at the belt (some of which I have shown in the drawing above) can coincide to become so overwhelming that after 'Flight' and 'Fury' your hero or heroine has to turn and Face things, and encounter the particular and universal self.

All of this is patiently paced throughout the Novel in 90 plan but I thought it might help you to have a handy quick summary for checking against.

I'd love to know your thoughts, so please do comment below and of course share this post. When we collaborate as writers, we get stronger, better, harder, faster. Thank you.

August 15, 2017

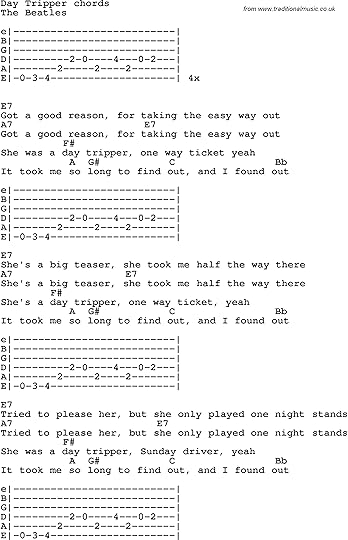

The Beatles 'Daytripper' - a lesson in how to write a novel in 2 minutes 47 seconds.

'It took me so long to find out, but I found out.'

A big novel is deft and assured from the get-go.

A big novel has a strident motif; it's bold enough to repeat it like a chorus or to repeat and remind it in a good line which speaks for the theme.

Think about Kurt Vonnegut's 'Slaughterhouse-5' 'So it goes.'

He wasn't alone. In fact a novel with a slogan (and a number in the title ;-) is a big hit formula.

The Beatles had cracked a formula.

'Daytripper' cashed in those chips during a prolific few days in October search of a 1965 Christmas hit. It's just 2 minutes 49 seconds of story-telling.

The composition of the song has the kind of recipe or confidence we can borrow, beg from and steal for novels.

There's the underlying easy-going electric guitar riff that's as certain and strong as a 'voice' from the opening. It's plain-speaking but good-humoured. A great way to kick any story off.

The song progresses through the elements of the five fold structure I give you at the Kritikme Novel in 90 Plan which is based on Aristotles's Poetics for 'Tragedy.' I double checked this structure against other major novels and in the course I show it's virtue as the structure behind J.M Coetzee's big novel 'Disgrace'

A novel begins with a dilemma, drawn from the main character's flaw, to which they're possibly blind at the kick off. They run from it. (Per Nabokov's prescription, in a novel you get your main character up a tree and throw rocks at him or her.) Per my prescription your hero or heroine goes from Flaw to False Hope to Flight to Fury to FACING IT. They run, run, run then they have to turn and FACE IT. There are only three ways to face anything. (Old Testament - with equal force, New Testament - turn the cheek, Crucifixion - self-sacrifice) in case you were wondering.

Listen to Daytripper and I think you can hear the five stages of a novel from not facing it, to facing it...with a nicely time crescendo for 'Fury.'

Get some new dance moves from the video too... on the house. (You're most welcome.)

August 14, 2017

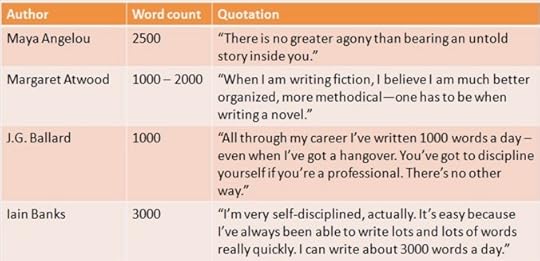

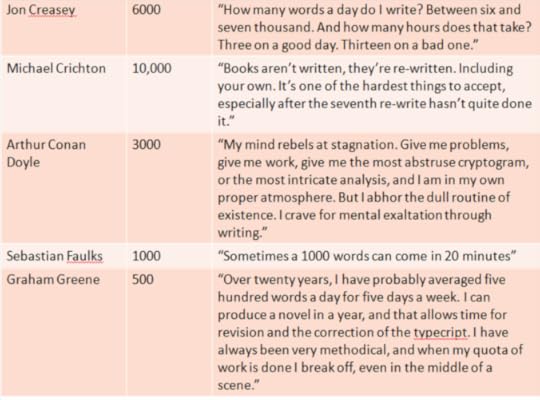

Word Counts. (Are You Normal?)

As part of our peering over writers' shoulders to see whether we are in any way 'normal' please find here the calibrations.

It's a little like the old shoe-sizer which we put our tootsies onto at 'back to school' time. I don't know about you but it gave me a funny little thrill. I hope this gives you a funny little thrill...

As for me? I'm deviant as often as I can be. Last Saturday it was 7,500 but when I'm on the first draft, I'll write about 1000 (rather poor words.) Some days it will be a cryptic misspelt-by-Siri note in my iphone notes programme, supposedly revelatory of a major insight (see last blog.)

I wwrite hundreds of thousands of words to reduce down to the 80k or so for a novel. This is a fool's economy of course, but then as Dolly might have said 'it takes a lot of money to look this cheap'.

During the first draft, please don't worry about word count, you will find your way, just be regular.

If you need to get your novel done in 90 days, then aim for 1000 when I tell you 'GO!" which is after we have got your concept nice and tight and made sure you're well prepared. Otherwise Graham Greene found he could knock out a novel every 9 months this way. Aim for 1000, but if things go stale, counter-intuitively reduce your target to release pressure and it will get you straight again.

For the second draft, you can go hell for leather because you'll be ending the Novel in 90 Plan with all the material you need and a one page (yummy) simple entirely virtuous structure for your novel which will make perfect sense and guide you through to sure-footed victory. (Sorry.)

August 13, 2017

#AMWRITING

From our collaboration as novelists working side by side - shush - beyond the Kritikme prescription of discipline and routine- have popped three things in the last few weeks:

the worth of moving between longhand writing to the keyboard and back, when and why

journalling the big write and to keep the first draft productive ‘deep’ play

and we have have been fairly gobsmacked that the process and it’s blues - or ‘motion sickness’ as we call it at Kritikme is so damned commonplace

We're hunkering down for another season’s write, beginning September, driving forward first or second drafts, propelled by the knowledge that writers from Steinbeck to Stephen King came to know the virtue of the 90 day write.

We know now that a draft of a novel is not only possible but more possible than not, in ninety days.

I knew my next novel had to be as good as I could make it having been so long in the making, and having gone wrong so many times. I had to get things right this time so I punished myself, and as Hemingway says a writer’s got to take a lot of punishment to write a truly funny book.

This was my thinking process:

I had to write a book that no one else could write, or would write

I had to get strong to do this, preparing a foundation for mind and body with sacrifice

I had to get smarter and study hard reading widely and keenly

I had to borrow a sense of humour if I couldn’t scrape one together myself

I had to lose my old self

The writing part is coming relatively easily after that.I gave up drinking, I started planning the next novel and instead began planning to bring other writers along for the write, to find some good-humoured writer comrades - and I started Kritikme which launched 2nd April (a canny day behind the fools’ day).

For 90 days I rose at 5am, and wrote my novel for an hour and a half, I worked one of my two day jobs recording my tutorial for the day as video film in the car on the way to work, I came home and spent a couple of hours writing the text of the next day’s lesson, I read all the major texts on the course, I read some of them in a week at the same time, I went to sleep after my reading at midnight, rose again at 5am.

I had no social life. I kept in touch with my writers throughout the day. I did a lot of wondering. I drove rather badly, shouting ‘Siri take a note!’. Those notes are bizarre as Siri is a faithless swine of a servant ‘Happy birthday pineapple’ was not enlightening to me at all. I ended up in a ‘speed awareness’ course ironically. (It was useful material.)

My writers and I began sharing our working days and practices quite naturally.

I finished the first draft of my novel in six weeks, a lady called Louise was my first Kritikme member to finish hers also in six weeks, and she told me how she wrote hers long hand. It reminded me....

Longhand is deep play, with a childish innocence and an artistic, entirely constructive quality to it, when typed up you automatically edit it and view it as a reader. The trouble with writing first drafts at a keyboard is that you stray and do other things or you over-fuss and edit with deletions and you can dick around with apostrophes and so on for hours, or do ‘research’ via Google you don’t need to do. Going between longhand and the keyboard thrashes out a lot of ailments. I write longhand in my notebook for beauty, I type up for story. The writing in the notebook is fresh-picked, when it goes into the computer it's canned and preserved.

Janice has a way with working with Scrivener app which was fast and furious and this is a boon to second drafters. So she shared it with a webinar. Sally had something to add to the Joseph Campbell Hero’s Journey structure and directed us to Maureen Murdock’s book The Heroine’s Journey. That book knocked me for six.

The women amongst us have been ashamed and baffled by how hard we find it to write women. That shame and bafflement has meant that I have never written a novel from a woman’s voice. Once I did and my then agent described it as ‘hysterical’. The slight loathing of the literary classes for books from the female voice is disturbing, and disturbing that we too as writers are guilty of it. The women we write are never bad enough, they do nothing, they can’t make stories happen. Jospeh Campbell told Maureen Murdock there would be no female equivalent of The Hero’s Journey. “Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological journey, the woman is there. All she has to do is realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

'Nice' but entirely unsatisfactory.

A novel is about running, running, running, then turning to face your fears. That is how people come alive, even in death, a novel teaches us.

We’ve seen ‘the problem of the bland woman’ is not a singular individual issue, it is a shared problem and now we can start to tackle it. Working one on one with my female writers we look at the possibilities of agency and ‘being bad’ for women narrators without necessarily being victims.

I took time off from my writing in July for important refresher reading. I read ten books in nine days to turbo-boost the self-criticism of the work I’d produced. I read Kurt Vonnegut Slaughterhouse-5, Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, Orwell’s 1984, Salinger's Catcher in the Rye, Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women, Herman Hesse’s Siddartha, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Maureen Murdocks’s Heroione’s Journey, JM Coetzee’s Slow Man, and one of my Kritikme writer’s Sunday Times bestseller.

I'd looked during the writing of the course at how Coetzee wrote Disgrace looking at the changes between his 19 drafts as part of the work for the 90 day course, and now I’m reading ‘Working Days’ an account of Steinbeck’s own write in 100 days of The Grapes of Wrath and it’s a singular exposition of the doubt and will and the interplay (or motion sickness) between creativity and self-criticism. Both are necessary, but when you work along you just feel sick, when you write alongside others in a safe warm place like Kritikme you begin to see the purpose of both and how they dovetail and you start to accept them.

I could see by August how for a novel to be great, there must be an alignment of these stars:

a big theme operating on many levels (personal, local, national, spiritual)

a stable sturdy well-read writer

a wounded hurt self-critical writer

a patient ascetic writer making a provisional sacrifice

a courageous first ‘gateway’ reader (agent or publisher)

The first emerges at the end of the first draft, don’t go looking behind your sofa cushions for it if you’re starting to write, just start to write. The course gets you sturdy, stable and well read. You’re hurt, we’re all hurt, but you’ll come to see why you need that and how to handle yourself with the deep play encouraged in the first draft Novel in 90 and how to keep an eye on it with journalling and be tender to yourself for a change. As for the fifth element, well we are working on that at the membership side of the site by encouraging big-hearted professionals on board to work alongside us in the same collaborative way we work at Kritikme and this week a literary agent, a Costa awards judge and a Whitbread prize winning novelist joined the team.

If you have self-doubt when you write, then know that it’s a natural part of writing, you need it, it’s what will make your writing better.

This is John Steinbeck writing in his journal at more than half way through (#entry 52) his 100 day write of The Grapes of Wrath

‘My many weaknesses are beginning to show their heads. I simply must get this thing out of my system. I’m not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people. I wish I were. The success will ruin me as sure as hell. It probably won’t last and that will be all right. I’ll try to go on with work now. Just a stint every day does it. I keep forgetting.’ (‘Working Days' John Steinbeck.)

What you’re doing is unique and important and difficult and possible, but you are not alone. Drop in and see us at kritikme.com.