Louise Dean's Blog, page 19

December 14, 2019

Retreat!

Taking time out of 'normal' life to immerse yourself in your other world is important for a writer. It's not so much about word count that comes with the daily practice, it's about leaps of insight in terms of the story and theme. Step changes.

These happen at a remove from the habits, routines and chores which obscure the bigger picture. If you want to take your novel to the next level, you need to get away. Not for sightseeing, though walks are helpful to refresh tired eyes, for a relief from the interruptions and duties that keep your mired, pedalling to stand still.

Our writers' retreats are carefully constructed to ensure complete full-body immersion in the world of your novel. No road noise. No deliveries. No cooking. Comfort. We believe in pillows; wonderful pillows for heads to dream new dreams.

Whenever I return to our retreat at Marshwood Manor in rural Dorset, that first night I have the sense of tipping backwards in the bed, as if my head is emptying itself. It's a curious feeling, an unburdening. If you wake in the night and step outside, you will hear the hooting of owls, like a spooky call from beyond. Underneath those black and starry skies, you wonder about being here, alive at this time, in this place.

An annual retreat is a necessary indulgence. Put it on your list of essentials. Off you go with a workmanlike manuscript. You dream of castles and statues and sea-wracked shingle beaches. You bend your head to the work, you bow to it. You leave not only with work which is better than that with which you arrived, you leave with something better than you.

That for me has always been the point of writing, to locate and preserve the best of me, the part of me that barely surfaces in normal life, the common good perhaps.

You return with a renewed sense of urgency and commitment. This is the boost you need to return again to that desk, throw everything off it, and resume the daily work.

The company you keep on one of our retreats is that of other serious writers hell-bent on their work, and when they put their heads up, they're keen to share their passion; it's infectious.

The photographs in this blog were taken by the photographer Kat Hill who joined us on our Bridport Retreat this year to work on her lovely novel. Upon her return home she said, "The biggest compliment I can give about the retreat is since I left I just want to be writing ALL THE TIME."

Our after-dinner readings offered writers the chance to come together both to read and listen, an audible proof of what's working. All the retreating writers made significant leaps during the week and read from the first chapter of their work in progress. We work forensically on those first chapters as they are proofs of concept. Notoriously difficult, they set the theme and treatment in play and require a moment of change. As one of our writers put it, the 'gear change'.

We were able to hear this in the readings as the author went from one extant situation to a new state in the narrative.

At the end of the week, we had a chat about what we'd learnt together from working sessions with me and as a team, chatting over tea and cake and dinner, and after the evening readings. Writers agreed that hearing work from other genres was enlightening, that writing a novel is far more 'collaborative' than they'd ever anticipated, and that buttoning down detail in the prose has an impact on the bottom line of story, both deepening it, intensifying and allowing for new possibilities. (Go back and button-down that detail again and again - be precise and visual!) The week raised ambition all round. Getting live warm feedback was such a boost. As one writer put it, and many agreed - "it gives one a new sense of confidence in the story, that it's unique and you're entitled to write it."

A retreat is a health-giving tonic without which your novel may ail and come to a standstill. Take time out to see what and why and how, and receive the encouragement you need. It's heartening to spend time with others like you, on the same journey, with this secret fire in the belly and the will to do it.

It's a lovely thing to see your writer pals, heads bent to laptops, raising a wave to someone out walking mulling things over, then to sit close with each other a drink in hand at the end of the day and share the story so far, and life and all that.

A retreat, a residential creative writing course, is the very best thing you can do for your novel and should have a place on your writer's calendar for 2020. Your writing deserves one fine week of thinking time.

"If you get the chance to go on The Novelry retreat, grab it with both hands. You will be well taken care of and your work will take off in ways you never expected. It was perfect." Sara Bailey.

"A wonderful venue in the peaceful, beautiful Dorset countryside. Fantastic accommodation, superb food, peace and quiet to write, and the opportunity for constructive and invaluable input from Louise. A great bunch of talented people, all committed to their writing. I felt I made real progress." Alison Fisher.

"The Bridport Retreat exceeded my expectations. I came away restored, with a renewed commitment to my writing practice and a much stronger novel. The tranquil Marshwood Vale, exceptional food and late-night storytelling fuelled productive writing days. The Novelry has created something truly special. I’d go back in a heartbeat." Shelley Motz.

Our retreats sell out very quickly. If you'd like to reserve a place on November 2020 retreat, do book in very soon as only a few places now remain.

The Full English (reserve your space for 2021 - 2020 sold out!)

Tracey Emerson's Full English Writing Week 2019.

The Full English Experience: What can I say? I arrived depleted and a little defeated after several months of winter, an unexpected illness that wiped out my writing schedule at the end of last year and a loss of confidence in my novel idea and my writing. I left with renewed confidence, energy and enthusiasm and with a firm direction for my novel.

This is a unique writing retreat. Firstly, the setting of Marshwood Manor and the welcome you get from owner Romla Ryan are superb. The accommodation is gorgeous and to have your dinner cooked every night is a treat in itself! You really can switch off from daily life there and shed your responsibilities. Secondly, the intense attention to the writing process brought breakthroughs for everyone. We were lucky to have Time Lott as our guest tutor, and his sessions on storytelling and story structure were so insightful that he made principles I had been reading about for years come alive. He promised he would drill story structure into us by the end of his four sessions and he did! His approach to teaching character was profound and thought-provoking. Also, my one-to-one session with Louise Dean, who has seen my story develop over the past year, was so personal and focused that I was able to make the choices I needed to make to move the story forward. Louise was also available any time for follow-up chats, and I think this generous, creative midwifery was a real feature of the week. As was the support of the other writers. Everyone there had come ready to work and explore and share, and I am beyond grateful for the encouragement and feedback I received. Oh, and we laughed. A lot. Oh, and we happened to have a mind-blowing two-hour session with world-renowned dream expert Ian Wallace thrown in as well. I would say we more than got our money’s worth!

One unexpected discovery I made during the week was that I could be more flexible in my writing routine. As a morning person, I prefer to get my words down in the morning, and I’ve always told myself that I couldn’t write in the afternoon, that my brain doesn’t function well then. Yet on the fourth day, after a three-hour session with Tim in the morning, I found myself cosied up on the sofa in a blanket, typing away with drooping eyes and having a huge writing breakthrough. I think I’d reached a sweet spot of mental exhaustion that forced my ego and all my doubts and niggles to leave the building. I managed to nail a first chapter that captured a voice I can work with.

That was the thread I was looking for when I came on The Full English, and the experience totally delivered.

The Novelry Report: Tracey is published author of the intelligent psychological thriller She Chose Me with a stack of five-star reviews on Amazon. She is writing her second novel with The Novelry. She is planning the storyline beautifully and showing flashes of brilliance in her understanding of the shadowy line of unreliability. Some of her turns of phrase make you tingle with their promise and foreboding. In the vein of Patricia Highsmith, this novel will be a great ride for the reader.

Ngozi Amadi Silver's Writing Week...

I almost didn't make it to The English Writer’s Retreat this February. When I finally arrived at my cosy cottage in the Marshwood Manor, I was two days behind, worried and agitated, and trying very hard not to show it.

That evening I sat with my fellow retreaters round a blazing log fire and listened to a very talented writer read her first few chapters. I knew from that day I will never be able to write anything remotely close to what I had heard. Every evening the bar went higher; the level of talent displayed at the evening readings was extraordinary. Every day the writers at the retreat, including The Novelry’s lovely and super talented founder Louise Dean, encouraged me to share my work, and I smiled and said I’ll try, but I knew I could never do it. I had taken The Novelry’s Ninety Day Novel course, had written fifty thousand odd words of a first draft, but still, I wasn’t convinced I had the talent to write or that my story was even worth sharing. As I often say to my friends: never underestimate the crippling power of the imposter syndrome.

I attended every remaining session with the award-winning guest author Tim Lott. I talked about my story and listened to others talk about theirs. There is nothing more refreshing than being able to talk about your work among like minds. I always felt like everyone in the room wanted the best for each other. Gradually I started seeing ‘the forest for the trees’, and my story started to evolve into something I felt wasn't half bad.

By the second to last evening, I knew I had to share something. Even if the words were total rubbish, it would be better rubbish than what I’d written in the two years since I’d started writing. I spent all of that night and the morning after writing my opening page. That afternoon I shared it with Louise and her warm and enthusiastic response gave me the confidence I needed to share with the rest of the group.

I will never forget that last evening. I kept forcing myself to smile and laugh with everyone, but all I could feel was my heart thumping in my chest. My whole body was shaking and only I knew it wasn’t from the cold. Suddenly it was time for me to read. The silence that fell on the room was unnerving and I didn't dare look up.

At the room erupted in applause. I looked up then and all I saw were beautiful smiles. I was almost giddy with relief. I kept bobbing my head like a bouncy toy as each writer said what she loved about what I’d read. They were so excited for me, it was contagious and I started feeling excited too. The euphoria stayed with me all night and lingered through the next day. On the last day of the retreat, one of the ladies held me close and said, ‘you’re a writer, never forget that.’ I mumbled something back, I don't even remember what, it was all I could do not to burst into tears.

Now I have an opening page, a clearly mapped out structure, and the confidence to write to the end, and this is all thanks to The Novelry and its amazing founder Louise. I would recommend anyone writing a novel, at whatever stage you are in the process to be part of The Novelry family and attend one of these retreats. Believe me when I say you would never regret it.

The Novelry Report: Nogzi's touching writing and unpretentious knack of nuance and setting give the reader a truly immersive reading experience. The dissonance she introduces with a culture clash piques interest and she has a firm grip on the story from the outset. She makes it plain to the reader that the quite loveable narrator has a flaw which could prove her undoing. This is a writer to watch. I'm very excited about her potential. If she can continue the book in the same voice and style, work with patience to unravel a story that's got such a universal appeal and such an interesting setup, she'll be courted by literary agents and soon.

Cate Guthleben's Writing Week...

Last night I dreamed I went to Marshwood Manor again… Actually, it has been my waking dream every day since I left last Sunday. All I want to do is go back – to Romla’s cakes, the peace and quiet, the dark starry nights, the readings around the fire, the cakes…

The week of the Full English Retreat was what dreams are made of – days spent talking about our books and how to make them better and nights spent sharing them. Each day began with a tutored session. On the first day, we had Louise on ‘Glamour’, and a brand new octopus Moleskine to write all our thoughts in. For the next four mornings, we had Tim Lott, who began with the psychology of writing, and how to be true to ourselves. He then took us through the basics of storytelling, and structure and plot and character. All things I’ve heard before, all things we all know, but how different it is to think about these things with your own story in your head, and with the time and the space to apply them to it.

The afternoons were our own – to write or read or walk or sleep. Or to drive to the coast and let the wind clear your head. I had to prepare a submission for a competition – 50 pages to edit and a 5-page synopsis to write. Having Louise on site was invaluable. Apart from our scheduled one-to-one, we talked my plot over on a dog walk and met again to settle my synopsis.

The evenings began with a G&T in Louise’s cottage, followed by one of Romla’s delicious meals. Then we gathered around the fire to read our stories aloud. It’s such a human trait, to tell a story around the fire. I could have happily listened for longer to every one of them. It was so satisfying to meet the books that people had talked about in our morning sessions, and to hear how they had chosen to tell their tale. I can’t wait to read them when they are published. Yes, they were that good. Everyone who came on this retreat was absolutely committed to the craft of writing. The standard was exceptional.

And then there was a final treat – Ian Wallace, our actual Dream Man. It was a perfect way to end a dream-like week.

I left with my Moleskine already half-filled. I made notes of what Louise and Tim said on the right-hand page, and put my thoughts on how to apply them to my book on the left. So much to think about. So much work to do to make it the best book I can write.

I got lost on the way home. It was deliberate – I didn’t want the week to end.

The Novelry Report: Cate's novel 'Mother Country' is close to finished and what a work it is. Breathtaking in its canvas - Australia in the early 1900's - and far-reaching in its stakes and moral reach. One of the most evocative and sweet opening's imaginable, this is what big novels are made of. The Novelry pitched Cate's novel to our agents and she's now happily at home with United Agents. Keep an eye out for this novel in 2020.

Viv Rich's Writing Week...

A treat of a retreat! With our first lesson from 'Miss' (Louise Dean) about ‘Glamour’, the tone of the week was set. Our novels grew with the inspiration we gained from each other and our daily lessons. Each evening readings sparkled with fascination, love, intelligence and wit. Our conversations helped us to consider our own novels, inspired us to achieve and learn more. Our one to one’s with Miss channelled those thoughts into productive review, structuring and editing.

The week was wrapped up in style with the exceptional Ian Wallace, fabulous cocktails, a wonderful last supper and a few glamourous shampoo-and-sets courtesy of Chantelle’s in Bridport.

The Novelry Report: Viv brings a gifted musician's ear to prose, seeking to create imagery that works like music She's got her eye on storyline now and that's the vital element to pursue now in second draft. This week, she and I enjoyed a mutual breakthrough as we laughed together about our common need to pare back our prose to get to the heart of the matter. Viv's determination, appetite and flair will deliver a novel in 2019 which I will be proud to recommend to our literary agency partners.

The Full English Writer's Retreat is available to writers for February 2021. We have sold places and just a few remain. Book your place now as it sells out quickly and early instalment payment plans are available.

We have some well-known, best-loved authors joining us as guest tutors - Sophie Hannah and Louise Doughty. Head of Fiction at Peters, Fraser + Dunlop, Tim Bates will be joining us for a session too.

December 7, 2019

How To Write A Children's Book and Get It Published.

SLAYING DRAGONS or how The Novelry saved a writing life.

"Kill the dragon," said Louise.

I was enmeshed in one of my all-too-frequent cycles of Writer’s Doooooom. My antagonist – a shapeshifter – had four alter egos: an evil taxi driver, a threatening bird, a magical girl and a dragon.

And my novel wasn’t working.

Rewind a year. A previous novel – contemporary women’s fiction – had been published six years earlier by a small press, and I’d struggled to write another. Writing against a backdrop of some extremely challenging life events hadn’t helped. 30,000 words were abandoned. 48,000 words: ditto.

I came across The Novelry when Louise offered one of her courses for auction for the Grenfell Tower fund, something made me follow this one up.

I told Louise Dean the sorry tale of how my writing demons had got the better of me. I just want to finish something, I wailed. And I don’t have a single idea. Louise was reassuring.

"I guarantee you’ll have ideas by the end of the first week."

I held on tight to her optimism.

As I clicked on the opening video for the Classic Course, it felt like I’d come home. Or, more accurately, I became Lucy Pevensie, pushing aside stifling layers of musty coats to reveal clear, moonlit air and a magical, expansive world.

I know why the Classic course worked. It gave me permission to receive. Writing had become a terrible treadmill of effort, or, to mix metaphors, I had my foot pressed to the gas but was grinding to a halt. The Classic course seemed to say: Come on in. Be curious. Play.

So I played. And received. And doodled with ideas. By the end of the first week, just as Louise promised, I had an idea, and by the time I’d completed the Ninety Day Novel course, there was a first draft, quickly followed by a second (dragon-less) one; then came the Editing course and we all lived happily ever after…

Not quite.

I knew that this final draft was flawed but had neither the knowledge or the confidence to change it for the better. The opening chapters were longlisted for the Bath Children’s Novel Award, which thrilled me, but didn’t make it to the shortlist. Meanwhile, I’d begun researching and submitting to agents. And this is where a series of synchronicities came into play.

During another of my cycles of Writer’s Doooooooom, I’d immersed myself in reading contemporary children’s literature and was convinced that my writing would never make it: the dragons of doubt were well ensconced. My writing was too quiet; there wasn’t enough action; and the weightiest and most obstinate dragon of all: it was all too late and I was far too old to get an agent, let alone to be a ‘debut’ author.

Then I happened to read Onjali Q. Rauf’s best-selling book about immigration, The Boy at the Back of the Class. It gave me hope. Here was someone who wrote in a similar tone to me. I looked up her literary agent and put Silvia Molteni at the top of my list.

I was lucky enough to ‘finish’ School for Nobodies just as Louise began getting requests from literary agencies to set up partnerships. She agreed to submit it on my behalf to Peters, Fraser and Dunlop. My first chapters and synopsis landed straight on the desk of Silvia Molteni who came back fast and requested the full manuscript. She read it in a couple of days and asked to speak to me. Louise called from the Bridport Retreat to let me know: in the background, the lovely writers of The Novelry cheered.

For me, The Call was the most terrifying part of all. Here was a most fearsome dragon guarding the gate to my hopes. I’d never spoken like this to a real, live agent and was convinced she would immediately realise I was completely unsuitable as a client. But Silvia told me she’d been looking for a Middle-Grade novel for a long time and was excited about School for Nobodies. She asked if I’d be prepared to do some work on it? Would I! What I loved about that phone call was that Silvia then offered to sign me immediately. She believed in my book and was willing to trust that I could do whatever it took to make it better.

Then the real work began.

Not all agents work on manuscripts with writers, and I’m eternally grateful that Silvia does. A few weeks later, four tightly-written pages of notes, questions and comments arrived, together with a heavily marked-up manuscript – and a deadline of 2-3 weeks to revise the novel, as she wanted to pitch it at the London Book Fair! I cancelled everything, put my head down and worked…

The publishing world operates in a strange, polarised manner: bursts of frenzied activity, where emails hailstorm into inboxes and deadlines rise up like giant waves, interspersed with long periods of glacial inactivity. I waited, breathlessly, for Silvia’s response. Then, after a couple of weeks, she wrote back, saying she loved what I’d done.

And then it all went very quiet as Silvia picked her time to submit School for Nobodies to publishers. She decided to submit to 17 publishers at once – hoping, no doubt, for an auction situation.

And the waiting began.

Two weeks later, I was on holiday in Cornwall, with a very dodgy mobile signal. Silvia rang to say that an editor, Sarah Odedina at Pushkin Press, would like to speak to me. Terrified again (I hate phones), I took my mobile up to the highest point I could find and croaked hello…

Sarah was lovely. She was really complimentary about School for Nobodies and asked what else I was working on. She said the manuscript was in good shape, but would I be willing to do more work on it? Would I! (is this sounding familiar?) But she didn’t actually say she wanted to publish it.

Weeks passed.

The other publishers responded. Their reactions were conflicting – from I don’t love it enough, through a really close call…this was by no means an easy rejection, devoured the manuscript in one sitting but felt some of the plot issues weren’t easily fixed…I just didn’t get on with the voice, a bit whimsical for my tastes…absolutely loved the voice but worried it felt quite similar in tone to a few projects we have on the list…it wasn’t quite there for us in terms of world-building and some of the characters…loved the vivid and fantastical characters…it felt slightly meandering…Susie has a unique ability to build pace in an effortlessly page-turning way…

And then, Pushkin made an offer. There are no words for the emotions pinballing around inside. I signed my second contract in just a few months.

More weeks passed. Then Sarah sent several pages of notes and a marked-up manuscript. This time I had longer to do the revisions – around six weeks. Sarah’s mantra was keep it simple. Louise had killed off my dragon. Now Sarah killed off my taxi-driver. My ‘darlings’ were being decimated one by one – but each grisly assassination improved the book. And at last I had the confidence to add a crucial new element which I hoped would solve the plot problems. Eventually, I sent off the re-re-re-re-revised manuscript.

And… waited.

Several weeks later, Sarah got back to me. She loved the revisions! I could breathe.

Next, the cover design. I was asked to write brief descriptions for each of my characters to send to the designer, Thy Bui. I was fully prepared to hate her interpretation of them, having seen middle-grade covers by other illustrators which I heartily disliked – so was completely taken by surprise by the beauty she created. I cried (in a good way).

Meanwhile, Silvia, my agent, sold the audio rights to a British company, which felt equally exciting. I would even have a say in choosing the narrator!

Then came the copy-editing. An editor went through the novel standardising the spellings and punctuation and house-style, picking up formatting problems, asking for more character description, querying inconsistencies (was it really two days since character X had done this, because it looked more like three?) (would that character say this at this point?) (hadn’t that character sat down a couple of pages back, so why were they standing now?), picking up repetitions (why were there two chapters called ‘Rescue’ and why had I used ‘eyes like saucers’ (argh, cliché alert) no fewer than four times in a few pages). I went through the whole novel around three more times, using Track Changes. I’ve just sent these off, and there will doubtless be more discussion before it’s finally ready to go off for type-setting. In January, the first page proofs will arrive, and at that point it will become expensive to make any further changes. I’ll then have three days to approve the final front and back covers and School for Nobodies will be sent for printing and published in May next year.

So that’s my publication story, dragons and all.

Oh, and one more thing. Remember how I almost gave up, believing it was too late and I was too old? Well, please don’t ever let that particular dragon scare you away from writing.

Because it took me 66 years to get an agent. And it’s been worth the wait.

November 30, 2019

The Best Writers Software and Writing Apps for 2020

Get Tooled Up for 2020, Writers.

The list of presents that every good writer boy and girl deserves to gift themselves this Christmas. Here's your round-up of the writing apps upon which writers really rely. They've been hand-picked to cheer you right up! I love these gadgets.

You'll find some old faithfuls and some new entries to our list - the tools I use when I'm writing and those most loved by our writers at The Novelry.

It's a better time to be a writer than ever before thanks to technology. (I know, I know, proper writers are supposed to be Luddites, but why? Make your life easier. Writing a novel's tough enough.)

#1. Scrivener

If you're tackling a big project like a novel, the organizational engine of Scrivener will ensure everything goes off to plan. Our members can enjoy a 20% discount on Scrivener at our Members' Library.

#2. ProWritingAid

The app analyzes your writing and presents its findings in over 20 different reports (more than any other editing software). You can keep track of your writing style with a neat integration of ProWritingAid and Scrivener. ProWritingAid imports your Scrivener folder into its platform and gives you a detailed analysis of how you're writing. I use ProWritingAid for that final finesse. For nuts and bolts, the dotting of i's and crossing of t's, ProWritingAid will cover that too, but you may also find Grammarly useful.

#3. Grammarly

The kindly grandma of all writing apps, this is a must-have for writers. You can install the plug-in and everything, even social media, gets a clean sweep before it goes out. Go premium. It's worth it. I consider this an essential and like the way it checks everything I do as I write online. I wouldn't press 'enter' or hit 'send' without it. For Mac users, you have to upload your text into the site browser but it's not a big deal and you get a second back up of those important chapters! I find it helpful for silly mistakes, tiresome little niggles, too many spaces and so on. Think of Grammarly as your copy cleaning service.

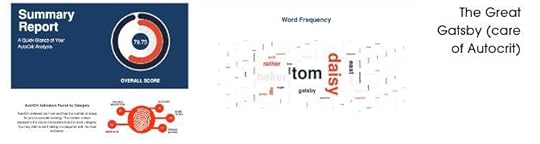

#4. NEW: AutoCrit

Swoon. I've had my head turned by this piece of kit which does everything almost every other app on this page does all in one and presents it beautifully too. Members can find a discount code and download the sample report I ran on The Great Gatsby's first chapter at our Members Library.

Unlike the other tools above, AutoCrit is 100% focused on the needs of fiction writers and authors. They say -"AutoCrit helps fiction writers quickly and easily refine their work by providing the most relevant, impactful feedback. The software dynamically adjusts your editing guidance based on data from millions of published books across many different genres and even lets you compare your work to published fiction by bestselling authors."

What I love about AutoCrit is the design of the summary report which includes a word cloud and enables you to take a look at the health check for your prose at a glance. I'm going to use it on my writers' work for sure. It offers a nice natural voice read-aloud feature too. You can at the flick of a switch pluck out them adverbs and passive phrases, should you wish. The show vs tell indicator is a great idea but it's set up is a little clunky, hey it's a start. It's weak on grammar, fine on spelling, so I'd still use Grammarly in combination with this. AutoCrit picked out my overused words in a way I've not seen so obviously shown before. Quite a surprise. ( So many 'thens', so little time.)

Authors can compare their manuscript to mainstream published fiction works and see how they stack up against them. "With AutoCrit, you can compare your work directly to real, published fiction from some of the top publishing houses in genres such as Mystery/Suspense, Fantasy, Sci-Fi, and Romance. A couple clicks are all it takes to see whether your manuscript matches publishing standards. You can even compare your writing to that of your favourite author to see how you stand up. Want to know who uses more adverbs, you or Stephen King? Now you can find out!"

The whole thing is put together in a less critical, more positive experience than its name suggests. I love the way it highlights your uncommon words and any writer's got to look at that and smile a little smugly, a roll call of your darlings. It's not often a writer feels flattered, so that might explain my heady feelings for AutoCrit, scoring my chapter at 87% vs Gatsby at 79% may have been the clincher. Maybe it's more of a Christmas toy maybe than a daily tool, but it made me happy. Love it. Try it.

#5. NEW: The Novelry's 'Book in a Year' Package

A new complete programme for writers old and new. A year of complete guidance and support to write wisely and fulfil your ambition as an author. The Novelry will lead you through the creation of a sound and appealing story idea onto writing a novel, then revising and editing your first draft. You will complete and hold in your hands a final draft ready to pitch to agents with our dedicated help and support every step of the way. Choose the safe and smart way to stay on track and achieve your ambition get that book done. Sign up here and save 20% on the prices of courses when sold separately.

(Don't forget you can gift a writer friend the novel course here.)

#6. NEW: Kindle App 2019 Version

Listen up. You can use all the tools in the world, but nothing compares to the earnest practise of comparing your writing to great work and asking yourself insistently - why isn't mine as good as this? Be fanatical about your craft. Read wisely. Take notes, make notes at bedtime to steer your morning's writing.

A lot's happened with Kindle app and now compatible with iOS and Android reading platforms; it's the ultimate reading tool for writers. No matter which platform you use, you will find in the Kindle app a more intuitive search, Goodreads integration, and support for Audible audiobook playback. I rarely buy physical books anymore because it's important to me as an author to be able to highlight passages of fiction and non-fiction and keep them as sources of inspiration and reference. I use the Kindle App on my iPad. It's a great combo with the perfect reading experience thanks to the background light enabling you to read with the light turned off, and magnification for the older reader.

There are so many options now for the text you highlight. You can keep it as Instagram ready 'art', send it to your Notes programme (now my mainstay for keeping random inspirations for my novel) and you can also search in Wikipedia, the dictionary and translate a word or passage to any language. It's amazing.

If you're planning to write a novel, spend a couple of months working on the idea with our Classic course, after which you'll sign up for the novel course to write it which asks you to run it past me at The Novelry to make sure it's a go-er and in the best possible shape for you to invest your writing time. When you're confident you've got all you need to start writing, choose a 'hero' book to lean on during your writing period. By that I mean an exemplary text, commonly recognized to be great, which works according to the great novel story format, our very own Five F's ®, which we teach at The Novelry. You can find a list of hero books at writershop.co.uk also thenovelryshop.com

#7. NEW: Google Street View

Don't leave home with it! (Apologies for the pun.)

It's now possible to get interactive panoramas for almost any location in the world using VR photography. Think about that. In my new novel I needed to check how customs point between Albania and Montenegro. Within seconds I was there, taking a good look around. Google Japan now offers the street view from a dog's perspective, and Google Street View covers two offshore gas-extraction platforms in the North Sea... great setting right for those writing Sci-Fi/Dystopian? The drag-and-drop Pegman icon is the primary user interface element used by Google to connect Maps to Street View. Occasionally Pegman "dresses up" for special events or is joined by peg friends in Google Maps. When dragged into Street View near Area 51, he becomes a flying saucer. The six main paths up Snowdon were mapped in 2015. A Google tricycle was developed to record pedestrian routes including Stonehenge, and other UNESCO World Heritage sites. Trolleys were used to shoot the insides of museums, and in Venice the narrow roads were photographed with backpack-mounted cameras, and canals were photographed from boats. Check out your location and get the detail just right. Instantstreetview.com is a nice easy interface using the tech.

#8. NEW: Wordcounter

So many writers worry about what their word count should be for their 'genre'. Tell a great story regardless of how many words. If you're going commercial you're going to want to hit 70k, but literary's much broader as a range. It's surprising how many favourite novels have low word counts. Sometimes a short book can feel very long, and a long book can feel short! Check them all out for free here. I've given this a high ranking for saving me so much time hunting the internet to check out how long that novel is!

#9. NEW: PickFu

Want to get feedback on your novel title? Well, many of us know Lulu title scorer with its bizarre algorithms for picking a winner but now you can get a poll done to pick your title between two candidates using PickFu which poses your question to a minimum of 50 respondents in the USA. 15 minutes to see results from $50. You can narrow your audience to heavy book readers, fiction, and a whole host of other criteria to check your candidate titles against your prospective readers. This can make a slow writing day a whole lot of fun!

The feedback you get is detailed too, and explains what's alluring in the title. The intelligent comments really give you food for thought, allowing you to see what inference each title is cueing at a glance. You can see how each title performs against age groups and genders. The results come in fast. My poll was neck and neck all the way until the final stages. I made my choice based on the cues mentioned by respondents. In my title poll Option A was 'classic' and 'timeless' and Option B seen as more 'intimate' and 'personal.' Option A appealed more to under 35's and men, and B to over 35's and women.

Oh, I love this! I could spend all day playing this game! What's more you can get feedback on your book premise or description too. You could run the poll against up to 500 people. Given the audience targeting features, I think this would be useful right at the beginning of scoping out an idea, and even more useful before revising your story to go to second draft, so you can proceed with what's appealing to readers. I find PickFu wildly exciting, but then I don't get out much.

#10. NEW: Otter Voice

Wow. Just wow. This one really works! It faithfully transcribes your voice to words before your very eyes on your desktop. I was quite stunned watching it automatically finesse and correct the word before my eyes. You can import recordings too and you'll get a notification when the transcript is ready. You can use this app for free and get 600 minutes of transcription time. For less than $10 a month you can export files as documents, skip silences and sync all your files via Dropbox. It's the ultimate tool for first, dictating your novel or second, getting reality recorded and onto the page.

Use it to collect the cadence of conversations and the sounds around you to bring 'buttoned-down detail' to your prose to make it more immersive. See our recent blogs on why such detail is vital for a novel. Unlike Just Press Record or other recording apps, the words appear before your eyes and make sense and next to the words is a second by second timeline making it easy to locate passages. I think this could be a winner as a replacement for two apps - voice recording and dictation - so it's gone straight into my must-haves for 2020. Get it, use it, love it - here.

Folks, it's time to tidy up the apps on your phone or iPad and the bookmarks on your desktop or laptop, for a fresh start in January. Bookmark these babies!

You may want to add this book to your bookshelves, particularly if you're not a member of The Novelry and will have to do the hard work of finding yourself a literary agent and publisher.

Writers & Artists' Yearbook 2020

Buy it now on sale with a 45% discount at just £13.75 until 15th December here.

Children's Writers' & Artists' Yearbook 2020 with a 45% discount at just £13.75 until 15th December here.

And finally, stay healthy.

Date and save your manuscript daily and keep it on the cloud, and keep your equipment clean. I dote on this baby. CleanMyMac (they also offer CleanMyPC). I'd probably have bought a new Mac had it not been for this gorgeous app which rids me of my data grime and keeps my RAM moving. I wouldn't be without it. For me this is an essential.

Stocking Fillers.

Sometimes you forget quite how the title works for little words. Head to Capitalize My Title. Phew. Job done.

Want to convert a PDF document to Word, edit or compress a PDF? It's free and functional with SmallPDF.

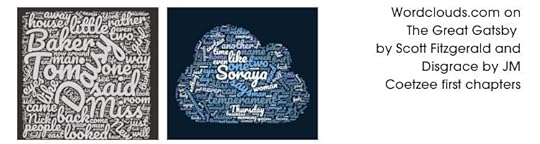

A cheap and cheerful way to check your writing is offered to you with the compliments of the charming Count Wordsworth. Check the number of times you use a certain word. You may be surprised and what seeds you're sewing in the subconscious of the reader! In the first book of The Bible “behold” occurs more commonly than “there”, “as”, “went” and “we”. For an analysis of the cunning repetitions of words to seduce the reader in The Great Gatsby, you may enjoy this blog article.

In search of an idea for that novel you're meant to write? How about writing one you never meant to write. Try the Random Logline Generator! I hit the page while writing this and found the idea for my next novel in less than 5 seconds. 'A telephone operator gives advice to the anachronistic adopted daughter of a magician in Scotland.' Why have you been fretting over your big idea for so long, you will ask yourself.

When you wake from a gripping dream, look it up and decode it. Writing is one way of finding out what's going on in your head, but dreams are the flash fiction reading of your troubled psyche and can save you some pondering in prose and provide a jumpstart to creativity. Like many writers, I started writing when I started writing down my dreams. Dreammoods App is a free app, and it's on the money more often than not.

For a thesaurus beyond compare if you're writing historical, I strongly recommend the Oxford English Dictionary which will who you what words were used when, but the bog-standard Thesaurus is great and here's another kid on the block for you - Onelook.

Check the differences between drafts very simply with Diffchecker. (Find those old darlings, and restore them to draft 58.)

Scope out the timeline planning for your novel with Mindmeister the mind mapping tool or with Aeon Timeline. The latter syncs with Scrivener, but I find it's encroaching too much on what Scriv does best. I prefer Mindmeister for getting a good oversight of my story development and I show you how to use it for yours in our Ninety Day Novel course.

Many of us use Canva for design work and to create some of the working tools we use at The Novelry to visualize the novel. It's a must-have, really if you want to create a social media presence.

You can bring all those highlighted passages from your Kindle or iPad iBooks into one place with Readwise.

Get a health check on your novel chapter by chapter at a glance by looking at the verbal DNA with Wordclouds.com. If you're writing a novel you're going to want to see in that cloud our hero or heroine's main focus of interest writ large. See this name loud and proud in your cloud for the first chapter, this is the name of the person who represents the embodiment of your main character's 'problem', weakness or flaw. So telling. More on the way novels work and how to build them with the author-created practical courses at The Novelry! Sign up and make sure you get your very best novel done in 2020.

Gifts for Writers You Love.

For more inspiration for writers' gifts do check out our shop for writing accessories, and don't forget you can give someone special the gift of a novel here.

Now, please share this article with your writer pals and via social media. Lots of goodies here to make life sweeter.

Wishing you much happy writing in 2020.

The Novelry.

November 23, 2019

Artifice - How to Write a Damn Good Novel.

One of the sweetest old chestnuts beloved of writers is the notion that a story is driven by what a character wants. Quite so.

It's a convention, it's a construction and it's a fakery of the highest order, yet we must have it so.

In real life, people are not propelled by singular obsessions, they are in fact a mess of conflicting wants, warring desires and to-do lists. This does not make for a great story. The ruse of a story is that the heroine or hero has a one-track mind. Those of you enjoying the BBC TV series 'Gold Digger' may not have stopped to consider how likely it is that a professional man in his late thirties with a family is obsessed with his mother's new boyfriend being a tad on the young side? Sure, in real life, he'd raise an eyebrow then get back to his in-box. But then there would be no story.

An entertainment requires some stage machinery that's about as sophisticated as a canon that fires one canon ball. We entertainers pull a fast one on the audience in a similar way to the stage magician.

We construct an artifice when we tell a story in the long form and the principle device of illusion is realism.

This is why much of the work I do with my writers in their final drafts I describe as 'buttoning down the detail."

We use lifelike facts to create a diversion. We use verisimilitude as a distraction to turn their gaze from the canon that's lumbering across the stage being pulled by elephants nowhere near ready to fire it's one cannonball - THE END.

We say - look here, this is all seems terribly real and ordinary doesn't it? We say - don't look there! Don't look at the thin plausibility of this chump's single obsession with his mother's boyfriend. Look at the buttons on that coat! Are they like yours? Look at the house, look at the recycling bins! It's all so real, and credibly presented.

When a reader, or the audience, is persuaded that the secondary or subsidiary matter is realistic, they believe the whole. You can get away with anything so long as you've got the number of the bus right, the name of the street, the sound of the rain on the cobbles, and the right flowers in bloom.

To create suspense and surprise in fiction, we draw the reader's attention away from the lack of evidence to support our singular premise and present events and situations and details of low significance and grant them space and status. Using realism as our prose method dignifies the whole so that the reader doesn't look at truth, the reader looks at reality.

Truth and reality are not the same. Reality lies, beautifully. Reality tells tales. Truth - less so, therefore fiction.

We keep the reader busy while we con them, and you can be purposeful about where and when you divert them, you can double bluff them with cliffhangers on matters extraneous while the murderer prowls about the book, smiling sheepishly.

Derren Brown performs an illusion of passing a knife through a twenty-pound note by using an ordinary note, and a special knife which he has custom-built, a knife without a blade. First, he casts suspicion on the honest note by making a fuss about taking it from a special compartment of his own wallet. Doubt falls upon it in the mind of the clever audience member. He places it flat on a table ensuring there is clear space around it to show its importance. Meanwhile, he's got a whole jumble of crockery going on and he's slipped the bogus knife in amongst the pile, a mess of objects not granted space. He keeps his eyes fixed on the note, fumbles for a knife, and stabs the note. He shows the audience the unscathed note and puts it down again in the sacred space. With sleight of hand he picks up a working knife and places it in the same sacred space for the member of the audience to verify.

The mystery is created by the magician's use of space "to focus attention and manipulate status". (Derren Brown.)

The item which deceives, the conceit, is hidden in what seems most real, and that which is truly innocent is given space.

In prose-practical terms, remember my blog advice a few weeks back to use that space return key to create space around what's important, or where you want to leave the reader looking or thinking. In story terms, it's done all the time. On a soap like Eastenders, the lie that's not yet revealed is dropped, and the scene changes. The change of scene in a TV soap or serial is the space return.

So while I am showing you the way my character prepares her roast chicken, you're not noticing that the son's absorption with an age gap and an eviction letter is thin in terms of evidence for the mother's lover being a dastardly con man.

Yes, have a premise for your novel story, but it doesn't need to be credible or complex. Keep it simple and bold. Because the artistry is in the artifice. Fiction is artificial! (Applause.) It's not real life. (Applause.) It's better.

Artifice in fiction is an illusion created and sustained by realism.

If you keep your reader convinced by the detail, they won't be examining the evidence, so you can relax and keep moving the canon across the stage, light a match to its backside and fire.

'The magician knows that all magic happens in the perception of the audience member; there is no necessary connection between the greatness of a magical piece and either the technical demands or the cleverness of the method behind it. A successful magical career will begin with learning sleights and buying endless tricks, but as he matures, having absorbed many years’ worth of technical knowledge in order to establish a mental encyclopedia of possible means to achieve impossible ends, the performer is likely to eschew tricky and pedantic methods in favour of more gleefully audacious modi operandi. To create a powerful piece of magic through the simplest, boldest method is one of the sweetest pleasures of the craft.'

Brown, Derren. Confessions of a Conjuror .

Authors differ in their uses of artifice. Showmanship, whistles, bells, fireworks that daze the reader are used in extraordinary ways in work of writers like Nabokov for whom a 'flaunting of artifice' is 'not merely ... a technique but also as a theme...'

"Vladimir Nabokov never lets his readers forget that he is the conjuror, the illusionist, the stage-manager, to whom his characters owe their existence." Patricia Merrivale.

You will have your own way with it. Personally I like the double bluff of dry, subtle, particular depiction that allows me to get away with people behaving badly. But you will have your own uses. The point is, au fond, that if you have no artifice, you have no semblance of reality, and the whole is reduced to the thinnest of fabrics.

This is what Salman Rushdie has described as the hardest part of writing a novel: "The art that conceals art."

So, writers, button down that detail! Do it now, and you'll find possibilities for the storyline which excite you in first draft, do it later and your book will stand firm against the chill wind of the reader's disinterest, but do it you must.

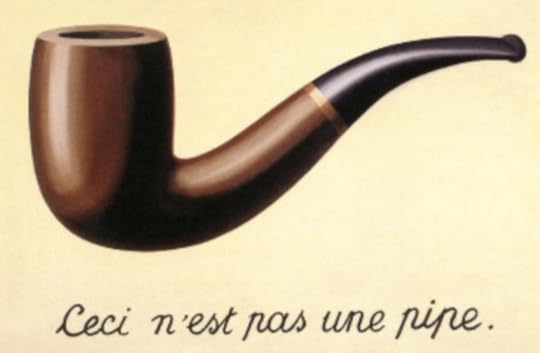

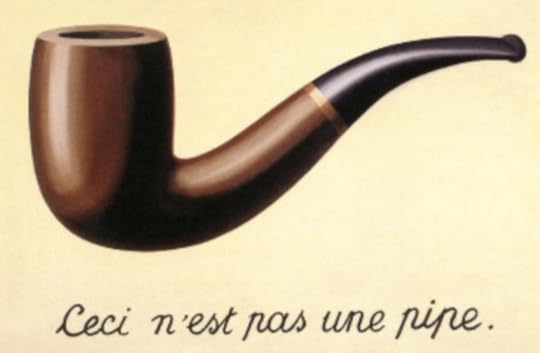

'The Treachery of Images' was painted when Magritte was thirty years old. The picture shows a pipe. Below it, Magritte painted, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" French for "This is not a pipe." The painting is not a pipe, but rather an image of a pipe. According to Matthew Rose, both the great art critic John Berger and Réné Magritte charged the viewer with the responsibility of working out the real, and ultimately "that which is critical and consequential". How to do that, how to decode reality? "Perhaps only with our greatest tool and its full arsenal of flavours: language."

Artifice

One of the sweetest old chestnuts beloved of writers is the notion that a story is driven by what a character wants. Quite so.

It's a convention, it's a construction and it's a fakery of the highest order, yet we must have it so.

In real life, people are not propelled by singular obsessions, they are in fact a mess of conflicting wants, warring desires and to-do lists. This does not make for a great story. The ruse of a story is that the heroine or hero has a one-track mind. Those of you enjoying the BBC TV series 'Gold Digger' may not have stopped to consider how likely it is that a professional man in his late thirties with a family is obsessed with his mother's new boyfriend being a tad on the young side? Sure, in real life, he'd raise an eyebrow then get back to his in-box. But then there would be no story.

An entertainment requires some stage machinery that's about as sophisticated as a canon that fires one canon ball. We entertainers pull a fast one on the audience in a similar way to the stage magician.

We construct an artifice when we tell a story in the long form and the principle device of illusion is realism.

This is why much of the work I do with my writers in their final drafts I describe as 'buttoning down the detail."

We use lifelike facts to create a diversion. We use verisimilitude as a distraction to turn their gaze from the canon that's lumbering across the stage being pulled by elephants nowhere near ready to fire it's one cannonball - THE END.

We say - look here, this is all seems terribly real and ordinary doesn't it? We say - don't look there! Don't look at the thin plausibility of this chump's single obsession with his mother's boyfriend. Look at the buttons on that coat! Are they like yours? Look at the house, look at the recycling bins! It's all so real, and credibly presented.

When a reader, or the audience, is persuaded that the secondary or subsidiary matter is realistic, they believe the whole. You can get away with anything so long as you've got the number of the bus right, the name of the street, the sound of the rain on the cobbles, and the right flowers in bloom.

To create suspense and surprise in fiction, we draw the reader's attention away from the lack of evidence to support our singular premise and present events and situations and details of low significance and grant them space and status. Using realism as our prose method dignifies the whole so that the reader doesn't look at truth, the reader looks at reality.

Truth and reality are not the same. Reality lies, beautifully. Reality tells tales. Truth - less so, therefore fiction.

We keep the reader busy while we con them, and you can be purposeful about where and when you divert them, you can double bluff them with cliffhangers on matters extraneous while the murderer prowls about the book, smiling sheepishly.

Derren Brown performs an illusion of passing a knife through a twenty-pound note by using an ordinary note, and a special knife which he has custom-built, a knife without a blade. First, he casts suspicion on the honest note by making a fuss about taking it from a special compartment of his own wallet. Doubt falls upon it in the mind of the clever audience member. He places it flat on a table ensuring there is clear space around it to show its importance. Meanwhile, he's got a whole jumble of crockery going on and he's slipped the bogus knife in amongst the pile, a mess of objects not granted space. He keeps his eyes fixed on the note, fumbles for a knife, and stabs the note. He shows the audience the unscathed note and puts it down again in the sacred space. With sleight of hand he picks up a working knife and places it in the same sacred space for the member of the audience to verify.

The mystery is created by the magician's use of space "to focus attention and manipulate status". (Derren Brown.)

The item which deceives, the conceit, is hidden in what seems most real, and that which is truly innocent is given space.

In prose-practical terms, remember my blog advice a few weeks back to use that space return key to create space around what's important, or where you want to leave the reader looking or thinking. In story terms, it's done all the time. On a soap like Eastenders, the lie that's not yet revealed is dropped, and the scene changes. The change of scene in a TV soap or serial is the space return.

So while I am showing you the way my character prepares her roast chicken, you're not noticing that the son's absorption with an age gap and an eviction letter is thin in terms of evidence for the mother's lover being a dastardly con man.

Yes, have a premise for your novel story, but it doesn't need to be credible or complex. Keep it simple and bold. Because the artistry is in the artifice. Fiction is artificial! (Applause.) It's not real life. (Applause.) It's better.

Artifice in fiction is an illusion created and sustained by realism.

If you keep your reader convinced by the detail, they won't be examining the evidence, so you can relax and keep moving the canon across the stage, light a match to its backside and fire.

'The magician knows that all magic happens in the perception of the audience member; there is no necessary connection between the greatness of a magical piece and either the technical demands or the cleverness of the method behind it. A successful magical career will begin with learning sleights and buying endless tricks, but as he matures, having absorbed many years’ worth of technical knowledge in order to establish a mental encyclopedia of possible means to achieve impossible ends, the performer is likely to eschew tricky and pedantic methods in favour of more gleefully audacious modi operandi. To create a powerful piece of magic through the simplest, boldest method is one of the sweetest pleasures of the craft.'

Brown, Derren. Confessions of a Conjuror .

Authors differ in their uses of artifice. Showmanship, whistles, bells, fireworks that daze the reader are used in extraordinary ways in work of writers like Nabokov for whom a 'flaunting of artifice' is 'not merely ... a technique but also as a theme...'

"Vladimir Nabokov never lets his readers forget that he is the conjuror, the illusionist, the stage-manager, to whom his characters owe their existence." Patricia Merrivale.

You will have your own way with it. Personally I like the double bluff of dry, subtle, particular depiction that allows me to get away with people behaving badly. But you will have your own uses. The point is, au fond, that if you have no artifice, you have no semblance of reality, and the whole is reduced to the thinnest of fabrics.

This is what Salman Rushdie has described as the hardest part of writing a novel: "The art that conceals art."

So, writers, button down that detail! Do it now, and you'll find possibilities for the storyline which excite you in first draft, do it later and your book will stand firm against the chill wind of the reader's disinterest, but do it you must.

'The Treachery of Images' was painted when Magritte was thirty years old. The picture shows a pipe. Below it, Magritte painted, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" French for "This is not a pipe." The painting is not a pipe, but rather an image of a pipe. According to Matthew Rose, both the great art critic John Berger and Réné Magritte charged the viewer with the responsibility of working out the real, and ultimately "that which is critical and consequential". How to do that, how to decode reality? "Perhaps only with our greatest tool and its full arsenal of flavours: language."

November 16, 2019

Orwell's Writing Style - Part Two.

The second of a two-part special blog on Orwell's own development as a writer to greatness. (Continued from last week's blog.)

I believe that novels happen in major leaps, via fits of destructiveness as much as creativity. What's more, an author's creative output is not a steady and static production line. Many writers find their voice, nail their theme, hit the sweet spot of storytelling art, inventiveness and lucidity in their later years.

So, how did Orwell make the leap from The Clergyman's Daughter to works like Animal Farm and 1984, from more conventional middle-of-the-road writing, small themes and safe prose to the stark, and bolder books of his last years? To 'prose like a windowpane'?

‘What I have most wanted to do… is to make political writing into an art’ George Orwell.

He wasn't quite there in 1939 after Coming Up For Air. So what happened to Orwell's writing in the years before Animal Farm written at the end of the war?

"If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them." Orwell 1946.

His keener influences came to the fore, as he owned his yearnings not just for the environment as we would call it now, but also for satire and speculative fiction, as we would say now. He married his yearning for an innocent past to an idealism which placed such possibilities as rebellion-centres against a bleak machinist future. He placed yearning in conflict with fear. This seems to me to be a good place to dig, and if you read again the opening quotation of his childhood yen - might we all not find solace as writers in putting the possibility of complete (disembodied, ungendered, unclassed, unmonied) freedom into the ring to defy duty and convention in our themes. I believe this is why commonly at the root of my writing is the Augustinian notion of the sinners who are saints and the saints who are sinners, an uprooting of order in favour of the wit of human disobedience.

At the outbreak of war, Orwell's wife Eileen started working in the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information. Orwell also submitted his name to the Central Register for war work, but nothing transpired. In May 1940 the Orwells took lease of a flat in London at Dorset Chambers, Marylebone. Orwell was declared "unfit for any kind of military service" by the Medical Board in June, but found an opportunity to become involved in war activities by joining the Home Guard. He saw the possibility for the Home Guard as a revolutionary People's Militia. His lecture notes for instructing platoon members include advice on street fighting, field fortifications, and the use of mortars.

In 1941 he began to write for the American Partisan Review which was anti-Stalinist and contributed to Gollancz anthology The Betrayal of the Left, written in the light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

"One could not have a better example of the moral and emotional shallowness of our time, than the fact that we are now all more or less pro Stalin. This disgusting murderer is temporarily on our side, and so the purges, etc., are suddenly forgotten." George Orwell, in his war-time diary, 3 July 1941.

In August 1941, Orwell finally obtained "war work" when he was taken on full-time by the BBC's Eastern Service. He supervised cultural broadcasts to India to counter propaganda from Nazi Germany designed to undermine Imperial links. This was Orwell's first experience of the rigid conformity of life in an office, and it gave him an opportunity to create cultural programmes. At the BBC, Orwell introduced Voice, a literary programme for his Indian broadcasts, and by now was leading an active social life with literary friends, particularly on the political left. Late in 1942, he started writing regularly for the left-wing weekly Tribune directed by Labour MPs Aneurin Bevan and George Strauss. In March 1943 Orwell's mother died and around the same time he told Moore he was starting work on a new book; Animal Farm. In September 1943 he resigned from the BBC keen to focus on Animal Farm.

Just six days before his last day of service, on 24 November 1943, his adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Emperor's New Clothes was broadcast.

Students of the Classic course at The Novelry may gasp here since we see in that course how much Hans Christian Andersen's work informed (and informs) the writing of many novelists. His process then is the image of what we teach on the Classic course, to help writers in search of a story.

By mining childhood vulnerabilities and those first vivid feelings and memories and putting them at the service of his fears, Orwell was able to produce a work of great originality, and this proved a step change for him in allowing him to write freely and truly with prose like a windowpane.

"I can't stop thinking about the young days," Orwell wrote to a childhood friend who contacted him after reading Animal Farm.

Good writing has much to do with renunciation, it's about giving things up, giving up our worldly concerns, the squalor of wishing to be considered this or that by others, in favour of finding a theme which has a sense of personal emergency to it. It's about finding the old wound and giving it space and air to heal, in a good, well-lit place.

The writer allows the sunlight of childhood to dry the damp patches of adulthood. Find the theme and the prose will follow, it has to, of necessity, we simply don't have time to obfuscate or prevaricate in tarted-up longwindedness. That story writes itself, and that is your rewards and the treasure ahead of you. (You will know the story's not right when you are loath to write it! When it's right, it's a mystical experience which unfolds daily.)

"Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally." Orwell 1946.

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story was published by Secker & Warburg in Britain on 17 August 1945.

The worldwide success of Animal Farm made Orwell a sought-after figure and freed him at last from the bonds of working for money. The fairy tale worked its magic. For the next four years, Orwell mixed journalistic work with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949.

Postscript:

In May 1944 the Orwells had the opportunity to adopt a child. In June a V-1 flying bomb struck their home in Mortimer Crescent and the Orwells had to find somewhere else to live. Orwell had to scrabble around in the rubble for his collection of books, which he had finally managed to transfer from Wallington, carting them away in a wheelbarrow.

The Orwells spent some time in the North East, near Carlton, County Durham, dealing with matters in the adoption of a boy whom they named Richard Horatio Blair. By September 1944 they had set up home in Islington, at 27b Canonbury Square. Baby Richard joined them there, and Eileen gave up her work at the Ministry of Food to look after her family.

While Orwell was in Paris in spring 1945, Eileen went into hospital for a hysterectomy and died under anaesthetic on 29 March 1945. She had not given Orwell much notice about this operation because of worries about the cost and because she expected to make a speedy recovery. Orwell went on to write his last great work in what were to be his final years.

"Prose Like a Windowpane." George Orwell (Part 2)

The second of a two-part special blog on Orwell's own development as a writer to greatness. (Continued from last week's blog.)

I believe that novels happen in major leaps, via fits of destructiveness as much as creativity. What's more, an author's creative output is not a steady and static production line. Many writers find their voice, nail their theme, hit the sweet spot of storytelling art, inventiveness and lucidity in their later years.

So, how did Orwell make the leap from The Clergyman's Daughter to works like Animal Farm and 1984, from more conventional middle-of-the-road writing, small themes and safe prose to the stark, and bolder books of his last years? To 'prose like a windowpane'?

‘What I have most wanted to do… is to make political writing into an art’ George Orwell.

He wasn't quite there in 1939 after Coming Up For Air. So what happened to Orwell's writing in the years before Animal Farm written at the end of the war?

"If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them." Orwell 1946.

His keener influences came to the fore, as he owned his yearnings not just for the environment as we would call it now, but also for satire and speculative fiction, as we would say now. He married his yearning for an innocent past to an idealism which placed such possibilities as rebellion-centres against a bleak machinist future. He placed yearning in conflict with fear. This seems to me to be a good place to dig, and if you read again the opening quotation of his childhood yen - might we all not find solace as writers in putting the possibility of complete (disembodied, ungendered, unclassed, unmonied) freedom into the ring to defy duty and convention in our themes. I believe this is why commonly at the root of my writing is the Augustinian notion of the sinners who are saints and the saints who are sinners, an uprooting of order in favour of the wit of human disobedience.

At the outbreak of war, Orwell's wife Eileen started working in the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information. Orwell also submitted his name to the Central Register for war work, but nothing transpired. In May 1940 the Orwells took lease of a flat in London at Dorset Chambers, Marylebone. Orwell was declared "unfit for any kind of military service" by the Medical Board in June, but found an opportunity to become involved in war activities by joining the Home Guard. He saw the possibility for the Home Guard as a revolutionary People's Militia. His lecture notes for instructing platoon members include advice on street fighting, field fortifications, and the use of mortars.

In 1941 he began to write for the American Partisan Review which was anti-Stalinist and contributed to Gollancz anthology The Betrayal of the Left, written in the light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

"One could not have a better example of the moral and emotional shallowness of our time, than the fact that we are now all more or less pro Stalin. This disgusting murderer is temporarily on our side, and so the purges, etc., are suddenly forgotten." George Orwell, in his war-time diary, 3 July 1941.

In August 1941, Orwell finally obtained "war work" when he was taken on full-time by the BBC's Eastern Service. He supervised cultural broadcasts to India to counter propaganda from Nazi Germany designed to undermine Imperial links. This was Orwell's first experience of the rigid conformity of life in an office, and it gave him an opportunity to create cultural programmes. At the BBC, Orwell introduced Voice, a literary programme for his Indian broadcasts, and by now was leading an active social life with literary friends, particularly on the political left. Late in 1942, he started writing regularly for the left-wing weekly Tribune directed by Labour MPs Aneurin Bevan and George Strauss. In March 1943 Orwell's mother died and around the same time he told Moore he was starting work on a new book; Animal Farm. In September 1943 he resigned from the BBC keen to focus on Animal Farm.

Just six days before his last day of service, on 24 November 1943, his adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Emperor's New Clothes was broadcast.

Students of the Classic course at The Novelry may gasp here since we see in that course how much Hans Christian Andersen's work informed (and informs) the writing of many novelists. His process then is the image of what we teach on the Classic course, to help writers in search of a story.

By mining childhood vulnerabilities and those first vivid feelings and memories and putting them at the service of his fears, Orwell was able to produce a work of great originality, and this proved a step change for him in allowing him to write freely and truly with prose like a windowpane.

"I can't stop thinking about the young days," Orwell wrote to a childhood friend who contacted him after reading Animal Farm.

Good writing has much to do with renunciation, it's about giving things up, giving up our worldly concerns, the squalor of wishing to be considered this or that by others, in favour of finding a theme which has a sense of personal emergency to it. It's about finding the old wound and giving it space and air to heal, in a good, well-lit place.

The writer allows the sunlight of childhood to dry the damp patches of adulthood. Find the theme and the prose will follow, it has to, of necessity, we simply don't have time to obfuscate or prevaricate in tarted-up longwindedness. That story writes itself, and that is your rewards and the treasure ahead of you. (You will know the story's not right when you are loath to write it! When it's right, it's a mystical experience which unfolds daily.)

"Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally." Orwell 1946.

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story was published by Secker & Warburg in Britain on 17 August 1945.

The worldwide success of Animal Farm made Orwell a sought-after figure and freed him at last from the bonds of working for money. The fairy tale worked its magic. For the next four years, Orwell mixed journalistic work with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949.

Postscript:

In May 1944 the Orwells had the opportunity to adopt a child. In June a V-1 flying bomb struck their home in Mortimer Crescent and the Orwells had to find somewhere else to live. Orwell had to scrabble around in the rubble for his collection of books, which he had finally managed to transfer from Wallington, carting them away in a wheelbarrow.

The Orwells spent some time in the North East, near Carlton, County Durham, dealing with matters in the adoption of a boy whom they named Richard Horatio Blair. By September 1944 they had set up home in Islington, at 27b Canonbury Square. Baby Richard joined them there, and Eileen gave up her work at the Ministry of Food to look after her family.

While Orwell was in Paris in spring 1945, Eileen went into hospital for a hysterectomy and died under anaesthetic on 29 March 1945. She had not given Orwell much notice about this operation because of worries about the cost and because she expected to make a speedy recovery. Orwell went on to write his last great work in what were to be his final years.

November 9, 2019

Orwell Writing Style - Part One

The first of a two-part special on Orwell's own development as a writer to greatness.

How did Orwell make the leap from The Clergyman's Daughter to works like Animal Farm and 1984, from more conventional middle-of-the-road writing, small themes and safe prose to the stark, and bolder books of his last years? To 'prose like a windowpane'?

Write the book only you can write, the book you're meant to write, I counsel writers in the Classic course, but how do you locate the book you can write freely and truly and honestly with cleanliness? Let me show you how Orwell, the author of that phrase, found his way.

Eric Arthur Blair was born 25 June 1903 (and died at just 47 21 January 1950 - which gives this ageing writer pause for thought.)

“I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life.” George Orwell, Why I Write. 1946.

Before being sent away to school at 8, Eric Blair had a very happy childhood in Henley.

His works included non-fiction and many great essays and short stories and the following novels:

1934 – Burmese Days

1935 – A Clergyman's Daughter

1936 – Keep the Aspidistra Flying

1939 – Coming Up for Air

1945 – Animal Farm

1949 – Nineteen Eighty-Four

Burmese Days was a scathing account of his time as a police officer in Burma (now Myanmar) 1922-27 and is the work of a young man and splenetic and drawn from his experiences. In a letter from 1946, Orwell said "I dare say it's unfair in some ways and inaccurate in some details, but much of it is simply reporting what I have seen".

A Clergyman's Daughter tells the story of Dorothy Hare, the clergyman's daughter of the title, whose life is turned upside down when she suffers an attack of amnesia. Orwell was never satisfied with it and he left instructions that after his death it was not to be reprinted. In August and September 1931 Orwell spent two months in casual work picking hops in Kent. During this time he lived in a hopper hut like the other pickers, and kept a journal in which "Ginger" and "Deafie" are described. Much of this journal found its way into A Clergyman's Daughter. He started writing A Clergyman's Daughter in mid-January 1934 at his parents house in Southwold and finished it by 3 October 1934. In the case of the private-school system in the England of Orwell's era, he delivers a two-page critique of how capitalism has rendered the school system useless and absurd. Mrs Creevy's primary focus is given rather baldy "It's the fees I'm after," she says, "not developing the children's minds". This is manifested in her overt favouritism towards the "good payers'" children, and in her complete disrespect for the "bad payers'" children. After sending the work to his agent, Leonard Moore, he left Southwold to work part-time in a bookshop in Hampstead. Gollancz published A Clergyman's Daughter on 11 March 1935.

Keep the Aspidistra Flying is set in 1930s London. The main theme is Gordon Comstock's romantic ambition to defy worship of the money-god and the dismal life that results. Orwell wrote the book in 1934 and 1935, when he was living around Hampstead. In August 1935 Orwell moved into a flat in Kentish Town, which he shared with Michael Sayers and Rayner Heppenstall. Over this period he was working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and had the two novels, Burmese Days and A Clergyman's Daughter, published. He was 32.

I like Keep the Aspidistra Flying and here we see Orwell more innovatively satirical with his reworking of the famous passage on love in Corinthians replacing love with 'money'. The book expresses his deep desire for freedom from the drudgery of both working for money and to support a wife and family.

“Before, he had fought against the money code, and yet he had clung to his wretched remnant of decency. But now it was precisely from decency that he wanted to escape. He wanted to go down, deep down, into some world where decency no longer mattered; to cut the strings of his self-respect, to submerge himself—to sink, as Rosemary had said. It was all bound up in his mind with the thought of being under ground. He liked to think of the lost people, the under-ground people: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes... He liked to think that beneath the world of money there is that great sluttish underworld where failure and success have no meaning; a sort of kingdom of ghosts where all are equal ... It comforted him somehow to think of the smoke-dim slums of South London sprawling on and on, a huge graceless wilderness where you could lose yourself forever.”