Louise Dean's Blog, page 12

March 21, 2021

High-Concept Fiction

From the Desk of our Tutor Katie Khan.

The publishing industry – and Hollywood (especially Hollywood) – has come to idolize high-concept fiction in recent years. A high concept can be summed up in one line, with a clearly communicable premise. This makes it very commercial because a strong hook, ‘elevator pitch', or a one-line premise is invaluable for an agent pitching your novel to a publisher. It’s also invaluable for your publisher’s sales team to pitch your novel to retailers. And it’s invaluable for the press to describe your novel to readers… And for readers to recommend your book to other readers… Have you seen the film about a shark terrorising a small town? Have you read the love story where we meet a couple on the same day each year? What about the book and film where a billionaire brings dinosaurs back from extinction to create an amusement park?

High-concept fiction is all about premise. If you’re writing high concept, you are writing a story absolutely driven by plot.

Sometimes a film or book is so high concept, the title alone is the premise. Jaws springs to mind again. Alien was famously pitched as Jaws in space. The Power: women develop the power to electrocute men. Sliding Doors. The Girl on the Train. Snakes on a Plane. Sharknado. Jurassic Park. And, if you didn’t guess it above, One Day.

Being a writer who suffers from a smidgen of imposter syndrome, it sounds like I’m praising myself when I declare myself to be a ‘high-concept writer’. But I am; this is how stories come to me. I have notebooks filled with the first inklings of high-concept premises; topline ideas and fractal elements of a situation or world. Many of those initial thoughts start life in my brain as questions: In a world where [x] happens… what if [y] were possible? If your idea comes to you with the words ‘What if…’ I think you’re onto the coattails of something high concept. The One: what if your DNA could match you with your one true love? The Last: what if you were the last survivors of the apocalypse – but discovered a murderer in your midst? I don’t think it’s a coincidence that both of those novels have been optioned by Netflix. In fact, I believe almost every book I’ve mentioned so far has been adapted, or is currently in production, as a film or television series. That’s the strength of a high-concept idea.

The downside of being a high-concept writer is what me and my agent together call the ‘and then what’. Sometimes I will message her and say, holy hell, I’ve just had a great idea… what if dogs could talk? (I have never messaged her this, it’s an illustrative example, but I don’t think she’d be wholly surprised if I did.) Juliet will then sometimes push back at me by saying, ‘okay, and then what?’ It’s amazing how often I only have the first half. In a world where… giant squid rain down from the sky… and then what?

If the first part of a high concept is the cool twist on the premise, I believe the most satisfying ‘and then what’ in high-concept fiction is the part of the story which is character-led. Who will you put into this exciting world? Who will we follow, who will we root for? In a world where dogs can talk… a cat learns to communicate via semaphore. A Spaniel uncovers an unspoken threat to the canine world. A human learns their dog didn’t love them as much as they thought. (Welp!)

To my mind, the character makes up the second half of a high-concept story. In a world where [premise], [person] [does an antithetical thing].

Unlike many authors, I have not yet met a character before a premise. When I hear other much more literary writers say, oh, this character walked into my head fully formed, I tend to scratch my head in bafflement. Meeting a character first? Unheard of. I’m more likely to drop myself into a world and then consider: who would be the most interesting character to put in this place?

There’s no wrong way to write. But with high concept, let me show you what I mean. What do you think came to the writer(s) first: Neo, or the Matrix? Offred, or Gilead? Ian Malcolm (or any of the characters), or Jurassic Park? In a world where women are forced into sexual slavery, a handmaid in the house of a powerful Commander must fight to survive. They may have tweaked her character in the television series to make Offred an active hero, but in the novel, the character of Offred is passive and almost certainly second to the premise. The real meat of Margaret Atwood’s masterpiece is the high concept: what would happen if a regressive, religious movement overthrew the government and forced the United States to become an oppressive state that enslaved women? The story is Gilead; the character is our empathetic viewpoint through which we experience it. We root for her, of course we do. But her character is married to the premise.

Allow me to reiterate something here. Who would be the most interesting character to put in this place? I cannot stress how important this is. Who you choose to marry to the premise is the execution of the book. The novel lives and dies by who you choose. Being frank, I’ve got this wrong before. I wrote a novel I have not yet shown to my publisher because, in the few drafts I wrote, I chose the wrong characters. I could never marry the premise to the character – the plot always felt like a stretch. It came across as a cool idea that drifted away in the telling.

The same question can also be framed like this: in this time, in this place, which character has the most to lose? And who is most at odds with this world?

Think of John McClane in Die Hard: “You're the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time,” to which McClane replies, “Story of my life.” The entire film – and subsequent franchise – would be different if we’d followed an invited guest at the party. Or a terrorist. Or his wife.

The other question I think lies at the root of a successful high-concept ‘and then what’ is something like this. What scenario generates the most naturally occurring tension and conflict between characters?

My advice here would be to look at existing social groups. Imagine if the apocalypse broke out while you were on a corporate retreat with your colleagues. My goodness, the fun you could have writing the office politics and workplace in-speak as the group battle to survive – plus you’d get to kill off the people who never washed up their cups in the office sink!

If you choose to write about characters who have no naturally occurring conflict between them, you will have to engineer it – and I speak from experience when I say it might never marry. The novel will fall flat. The premise will always be better than the book, and no writer wants that.

Romantic couples are a tried-and-tested high concept winner, because there’s either a spark of chemistry between them – or a wealth of emotional history to mine. Good tension! There’s a breadth of high-concept women’s fiction at the moment: take Beach Read (two authors struggling to write their own novels swap and write each other’s for the summer, while also falling in love), or In Five Years (a woman is asked in a job interview where she sees herself in five years, then flashes forward in time to see her life completely transformed with a different romantic partner, and must figure out why).

My first novel, Hold Back the Stars, is high concept: a couple are falling through space with only 90 minutes of air remaining, intercut with their love story on a utopian Earth. Okay, it’s not as neat as ‘a man must stop a bomb going off on a bus’ (Speed), but it’s definitely pitchable in one line. And by putting Carys and Max in a romantic relationship, every single thing they did to try and save themselves in space was informed by the love story the reader saw unfurl on Earth. The relationship between them became the ‘and then what’ of the ‘two people are falling through space’ premise. Will they live? Will they sacrifice themselves for the other? And why are they in space together in the first place?

There’s a shorthand that’s popular with high-concept fiction: X meets Y. It was when I described my debut novel as ‘Gravity meets One Day’ that it hammered home the high concept, and it sold as such. X meets Y is a very, very popular device in this genre. But be careful what you choose; it needs to be illuminating. And it can’t be a straight match: the two properties have to collide. (Remember ‘Jaws in space’. Or George R.R. Martin’s pitch for Game of Thrones: Lord of the Rings meets the War of the Roses.) ‘The Girl on the Train meets Gone Girl’ does nothing. How does your collision form something new, what spin or twist are you putting on an existing property or genre?

A recent book acquisition making waves on both sides of the Atlantic is Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé’s debut novel Ace of Spades, publishing this summer with Feiwel & Friends in the United States and Usborne in the UK. It was snapped up by an agent and sold for more than a million dollars. The pitch? Gossip Girl meets Get Out. ‘How can you play the game when the cards are stacked against you?’ It tells us everything we need to know: the setting and characters (an elite school) and the theme (race and privilege). I cannot wait to read it.

The final thing I’d note about high-concept fiction is its singularity. I didn’t Google any of the one-line premises or loglines I’ve included here; I wrote them from memory. A decent high-concept story can usually be described in a similar way by many readers, because it is so singular in its vision. It’s rare that the plot of a famous 1980s high-concept movie (‘a robot is sent back in time to kill the leader of the Resistance before he is born’) would be described as ‘a love story about a man sending his father back in time to impregnate his mother, while they’re hunted by a robot’. Both of those are about Terminator, of course. But you’d have to be very contrary to try and pitch the second!

In summary:

Premise first, plot first. Your hook will likely start with a question or setting: ‘In a world where…’ or ‘what if…’

Character second – the ‘and then what’ of the pitch.

What the characters have to lose, and the natural conflict between them, will define the success of the story.

If you’re combining two existing genres or story archetypes, the combination needs to feel fresh.

Happy writing!

Katie

March 13, 2021

Val McDermid On Writing.

From the Desk of Val McDermid.

One of the reasons for the popularity of crime fiction is its faithfulness to the idea of narrative. Crime novels provide their readers with stories that engage with their hearts and minds, but most of all, stories that make sense.

I’m often asked where my ideas come from, and my answer is that stories are everywhere. Once you train your antennae to hear them and see them, you can’t avoid them. But a story is only the beginning of the process of producing a novel.

What’s just as important as story is structure – how we tell that story. The stories that satisfy us have a beginning, a middle and an end. But they don’t necessarily come in that order. Think of how you tell an anecdote in the pub or at work. Sometimes you begin at the beginning. ‘John picked me up to go fishing this morning.’

Sometimes you begin in the middle. ‘So there we were, out in the middle of the loch, when John suddenly realized he’d left the back door open.’

And sometimes you begin at the end. ‘You’re probably wondering why I’m sitting here in the pub all wet and covered in fish scales.’

One of the questions that come up again and again when I’m working with aspiring writers is, ‘How do I know where to start?’ The answer I usually give is simple. Imagine you’re having a drink with your best friend. Where would you start telling them your story in a way that makes sense?

Over the years, the crime novel has proved itself to be extremely nimble when it comes to storytelling. Of course, there’s a place for the linear narrative that begins at the start of events and continues in a straight line to the end. But not all stories lend themselves to that sort of shape. And one of the toughest struggles we often face is trying to find the structure that allows us to tell the brilliant story niggling away at us.

I know from bitter experience that it can take years. Probably the longest I’ve struggled with a book before finally cracking it was the twelve years – yes, really, twelve years – it took me to figure out the structure of what became Trick of the Dark. The story sprang from a chance encounter in Oxford one sunny Saturday afternoon in August. By the end of the weekend, I knew who was dead, who had killed them and why. But I couldn’t figure out a way to tell the story that preserved suspense and would induce a reader to persevere.

I wrote the first 10,000 words of that book and tore them up five times before I figured it out. The answer, when it finally came, arose from a change in circumstances in the world around me, not from anything smart that I came up with. It was an object lesson in patience.

Most structural problems are far less intransigent than that. And although the novel that emerges can seem complex, the route to reach that complexity is often as simple as working out how you’d summarise that story to someone else. For example, if you get a little way into it, then go, ‘Oh. Wait a minute. Before this next bit makes sense, you have to know this,’ then it’s probably an indication that you need a prologue or a split time frame. The key thing is that the structure is ultimately organic; the shape is dictated by the story, not by a single moment where the world of the protagonist is turned upside down.

When I was working out the mechanics of The Mermaids Singing, I struggled with how to convey to the reader the events that had happened before my main multiple third-person narrative began. I could have had my police officers briefing Tony Hill, the psychological profiler. But I thought that lacked immediacy. It told the reader nothing about the impetus behind the killings and it felt very one-dimensional.

Then I hit on the idea of writing the killer’s story from their point of view in the form of a personal record that would be their own way of reliving what they’d done. It never occurred to me that it might be problematic to have two distinct time frames in the finished novel because it made perfect sense to me. The killer’s first-person narrative begins some considerable time before the third-person narrative but they eventually converge. Many readers have spoken to me about The Mermaids Singing, but not one person has ever indicated they were confused by the timeline. I learned from that experience to trust that when a story made sense in summary, it would make sense when I’d written it.

The Mermaids Singing was the first time I struggled with finding a structure that bucked the traditional shape of the detective novel but it was far from the last. One reviewer of its sequel, The Wire in the Blood, began by complaining it broke all the rules of the crime thriller – by page three, we know who the killer is; we know his target group and his motivations, and not all of the characters we’re invested make it out the other end. By the end of the review, the critic conceded he’d been completely won over.

Since then, I’ve played fast and loose with the narrative conventions in books such as A Place of Execution, A Darker Domain and The Vanishing Point. But because it was the only way I could imagine to tell the story, not because my goal was to reach a moment that made the reader gasp.

I’d learned a valuable lesson – let the story be the driver.

Focusing on the shocking moment of the twist so often distorts a novel, bending it out of shape in a way that either frustrates or disappoints the reader. Of course, there’s a place on our shelves for the novel that relies on a sudden reversal of fortune. But it’s a tough trick to pull off; it should be only one tool in the storyteller’s kit. It’s much more fun to play with the whole box of tricks!

The Queen of Crime, Val McDermid, will be live at The Novelry answering our writers' questions on the craftiest of craft skills on Monday March 29th at 6pm UK time. See you there!

Happy writing.

March 6, 2021

The Firestarter 2021

The video above will reveal to you the name of the winner of this year's Firestarter at The Novelry. (You may wish to hold off until you've read the following.)

This the fourth year of our annual competition for the best opening to a novel, and previous winners are Kathy Brewis-Dunn (2018), Cate Guthleben (2019), Walter Smith (2020).

Entry is open to all but strongly recommended for those on the second draft and beyond and as ever, the results bear out the importance of editing, editing, editing. We never envy one another at The Novelry, where we work together because we darn well know how hard each and every writer has worked to get that novel over the line. All the art's in the redraft, and that's a comforting thought. It allows for time and space to make mistakes and play in the first draft. There's nothing to fear, no need to be nervous when you're writing a novel, folks. You get to choose when you hit send, and no one needs to see your workings! So play! Be wicked. (Oh, go on, a bit more wicked than that.) It's fiction. It's an entertainment. Sure there's art to it, but the art's in the sleight of hand, the mischief, the smoke and mirrors and even more so in these testing times than in the winsome quality of your prose. So consider this an invitation to join the merriest of playgrounds and never look back.

This year, the commentary at our members' site during the month of February as our writers began to post their entries has been universally one of praise and encouragement. I'd like to thank all of you for being the gorgeously good eggs you are. For reading the work, and giving it a big cheer. It matters. Those who entered have been posting fulsomely about the wonderful experience of getting feedback on their work. And that's how The Novelry began, four years ago, as a boon to the writer toiling over their novel with no idea if it was good, bad or - worse - middling. It's so good to know what's working - and what maybe not so much.

As you all know, I like a problem in the writing. Because once we see it, we can fix it. And solving problems as we go is what makes a good novel thoroughly ingenious. So embrace the problems. It's the 'not seeing' them that's the issue. The only problem a writer can have is no problems. The work just flat-lines.

You have said too how hard it was to choose a single winner from the entries. The standard this year was exceptionally high. I'd say our highest yet. (Rubs fingernails on lapel and sucks in cheeks Miss Brodie style - you are my beloved writers, truly, 'la crème de la crème.')

So I told you to bloody well get on with it! And plump for the one you simply HAD to read more of first. And you did.

Thank you not only to our entrants, but to those who voted. You read through so much work this week, with such generosity. A writer who takes time away from their own writing to help others will surely find a seat reserved for them in the literary heavens. You are all blessed according to the Gospel of Ernest (Hemingway) who rarely conferred such beatitudes.

And now, the winner.

This year's winner is Anna Verena Brandt with the opening to her novel - 'And I Saw The Beast.'

Nordic Gothic, a chilling erotic thriller-cum-fairytale most noir, this is the story of a woman's visit to her sister during a blizzard, where she becomes trapped in a Norwegian cabin with the sister and her 'bestial' husband.

There is snow, and there will be blood.

Written with tense, 'to the bone' prose, this is a novel as unflinching as Oyinkan Braithwaite's My Sister, the Serial Killer. You just can't look away. It's brutally honest, riven with danger, unsettling and affecting.

Anna is on the third draft of her novel, and it's impossible to think of anyone who better deserves this accolade. Anna, well done to you. There's a cash prize of £150, and this year's literary agency partner for The Firestarter - The Soho Agency - will be pleased to see your first three chapters. Huge congratulations.

In second place is Juliana Adelman with 'The Grateful Water', a historical murder mystery, set in mid-Nineteenth-Century Dublin. When butcher, Denis Doyle, finds the body of a newborn infant in the River Liffey he becomes fixated on finding the killer, unaware of how close to home his search for the culprit will bring him.

In third place is Caroline Longman with 'The Remarkable Adventures of M.A.D Brown' a comic adventure tale, and a witty romp. Millicent Brown is determined to leave her dead-end job in dull 1959 England and go to the glamorous French Riviera, so when she inherits £50 after accidentally killing a man, she buys her ticket to freedom. Complications ensue.

Honourable mentions must go to these entries which scored well too:

Lucy Barker with 'The Wickedry of Mrs Wood'. Historical Fiction. 1873, Notting Hill. When London society's favourite medium, Mrs Wood, is upstaged by a newcomer, how far will she go to stay on top?

Alison Bloomer with 'Wannabe'. A romance. An ambitious young singer hits the charts and starts to fall apart as she begins to wonder about the child she left behind her in Ireland, and turns reluctantly to the child's father for help.

Amy Sandiford with 'Memories of Rook House'. A Gothic novel. A sad and lonely man, damaged by his unhappy childhood, tries to fix himself by stealing other people's memories.

Jill Whitehouse with 'Push Me, Pull You'. A psychological suspense novel. Anne’s job bores her, her marriage has become a disappointment, her back hurts and her reliance on painkillers is growing, but when her husband runs a woman over and brings his victim home, what she finds in the woman’s bags alters everything. How far will Anne go to change her life?

Once again, love and thanks to all of you for taking part in our big adventure, writing our novels side-by-side and know that all of this work, all of it, every jot, every whit, every whimsy has been hard-won. If your name's not mentioned here, take heart. The names above are almost all beyond the second draft. You can lift the work, and lift it, again and again and we're here to support you all the way.

All that separates you from being published is determination and a sense of humour.

Happy writing!

February 27, 2021

Can Creative Writing Be Taught?

Our new tutor at The Novelry, the bestselling author, Harriet Tyce, weighs in on the big question with her own experience as a student.

From the Desk of Harriet Tyce.

We all remember the good teachers that we’ve had. We also remember the bad. I’ll never forget Mrs Podd, who told my parents I’d never be any good at English (never let it be said that I hold a grudge). Or Mr Marsh, who first introduced me to TS Eliot, and the idea that I might study English at university. He also told me that my poetry was too self-indulgent. (I found some recently – all I can say is that he wasn’t wrong.)

I’ve had a lot of teachers over the years. I’ve done a lot of courses. After school, I’ve been taught English Literature, Law, Cookery, Gardening, Piano.... and Creative Writing. Lots of Creative Writing.

A course was my first introduction to writing; a course led me to being signed by an agent, and ultimately being published.

There’s some debate about whether creative writing can, or even should, be taught. I see the force in the argument. Anyone can pick up a book and read it, analyse how it’s been put together. Anyone can pick up a pen and a piece of paper and start to write. If this is something that you’re able to do, I think that’s brilliant. But I know that I had no idea what to do when I was at the beginning. I needed a teacher. I said this in an earlier blog I wrote for The Novelry, but I had no idea even how to present dialogue on a page. I was completely intimidated by speech marks, so much so that it took me at least five years between realising that I wanted to write, and actually daring to give it a go.

One of the traits for which my daughter mocks me is that for every problem or question that arises, I’ll buy five books that address the solution. She has a row with a friend, suddenly she’s hit with a pile of tomes about rebel girls and self-empowerment. Learning to write has been no different. As I sit at my desk I can see at least twenty books about writing on the shelves next to me. Here is a selection:

The Thirty Six Dramatic Situations – Mike Figgis

Character, Scene, and Story – Will Dunne

The Art of the Novel – Nicholas Royle

Release The Bats – DBC Pierre

Bird By Bird – Anne Lamont

The Art of the Novel – David Lodge

Aspects of the Novel – EM Forster

How Novels Work – John Mullan

The Art of Creative Writing – Lajos Egri *

How Fiction Works – James Wood

On Becoming A Novelist – John Gardner

Consciousness And The Novel – Lodge again

First You Write A Sentence – Joe Moran

Steering The Craft – Ursula Le Guin

On Writing Fiction – David Jauss

Crime Fiction – John Scragg

The Noir Thriller – Lee Horsley

The Science of Storytelling – Will Storr *

Storytelling – Paul McDonald

The Art of Writing Fiction – Andrew Cowan *

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain – George Saunders *

That’s just the shelf to my left. I mean, where do you start? (The ones I’ve marked with an asterisk are the ones that have stayed most with me.) I’ve read them all, once upon a time, and the wisdom contained in their pages has, in my more hopeful dreams, percolated into me so that these aspects of the craft are intrinsic to me, written down in my bones (another great book, Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg). I’m not so sure it has, though.

Every time I come to start a new novel. I look at the blank page and I panic, my mind blank too. As Eliot puts it in East Coker,

‘each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion.’

Then I google, ‘How to write a novel’. Beginnings are the hardest thing. Other than endings. Or getting through the middle. There’s a forest of words out there offering help, but which the best, which the clearest guidance? You can read all the books there are out there on writing, but sometimes, the more you read, the less you understand. That was certainly my experience.

At the beginning, when I understood how little I knew about how to write, despite all the books I’d read, I sought out a guide. I signed up to a writing course in the hope that I would find a teacher who would lead me through the forest to a place of clarity, or at least show me how to use inverted commas properly. I might not have learnt about inverted commas, but I read the short stories of Hemingway and Chekhov. I learnt about Raymond Carver and the power of a good editor, how Gordon Lish transformed his work from the slightly mawkish to the sublime.

I wrote a short story. I talked about this short story in my previous blog post for The Novelry. It was good, in that it had a beginning, a middle and an end, but it was very limited. The course had done what it set out to do, though. I had begun writing.

I kept on writing. (In that last blog post, I listed the courses I did. The evening course at City University, the MA at UEA. One that wasn’t so great.)

I’ve had a lot of writing teachers, good and bad, and I’ve learnt a lot from all of them, even when the experience has been negative in parts.

We are all be familiar with E.L. Doctorow’s comment, that “Writing is like driving at night in the fog You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” It’s very true that you can make the whole trip this way – it pretty much encompasses my approach to writing, especially when I throw away my carefully developed plan and wait to see where the characters lead me – but it’s so much easier if there is someone kind and encouraging in the seat beside you, holding onto the map, pointing out the obstacles in the road ahead.

Starting to write is a strange and nervy time. I’ve never felt more vulnerable than in the early stages when I exposed my overwrought sentences to the glare of full daylight, reading a paragraph aloud in front of a group of people. I think if I’d met with discouragement at that stage, sneers or laughter, I would have given up on the spot. I was lucky that what resistance I did meet came much later down the line, a comment of very ‘professional’, a putdown so subtle it took me a while to realise quite how damning a comment it was.

Writing itself is strange and nervy, let alone being published. When I’m at my worst, my most anxious, I spend a lot of time looping between Amazon and Goodreads, checking out whether books by authors in the same genre as mine have more or less one-star reviews. In those moments, the idea of competition is terrifying. I can quite see why some writers who also teach might find it hard when they’re confronted by someone who could be a thrusting new talent. I can understand why the temptation to be crushing is almost irresistible. After all, they can justify their meanness to themselves, if someone can’t take criticism from a teacher, how will they ever be able to negotiate the horrors of rejection by a myriad of agents and publishers?

It’s not helpful, though, to be on the receiving end of this. Many of us have experienced it, and to the emerging writer, green and fragile, it’s worse than a hard frost in March.

Much more helpful are those writers who see teaching as a collaboration, who have the confidence to admit how much they themselves still have to learn. I know from the work I’ve done with other writers how much there is to be gained from working on a problem together. In analysing someone else’s narrative, I crack issues with my own. To borrow a quotation from the world of medicine, by which I was really struck when I read it:

“The safest thing for a patient is to be in the hands of a man involved in teaching medicine. In order to be a teacher of medicine the doctor must always be a student”.

The craft of writing is something you can teach yourself, but it’s a hard and lonely lesson if you’re on your own. I’m very grateful that I had the opportunity to learn from so many great authors, so many great teachers. From so many fellow writers, too.

I’m very excited to be starting as a tutor at The Novelry. I know that with every writer to whom I may be able to impart some knowledge, I will learn from them too. And I really hope I’m there to discover the next Highsmith, Gillian Flynn or Pelecanos. Who wouldn’t want to be thanked in those acknowledgements?

Happy writing!

A very warm welcome to Harriet Tyce. We're so excited to have her joining our team to work with our wonderful writers. Join us and enjoy inspired advice from Ms Tyce!

To find out more about our Positive Teaching Method and collaborative approach to helping writers 'turn pro' see our guidance 'How It Works' when you scroll down this page here.

(A pro tip - fast track your writing with a working 'apprenticeship' style with a published author whose work you respect.)

February 20, 2021

Nikesh Shukla - Blood On The Page.

From the Desk of Nikesh Shukla.

A lot of writers talk about the importance of voice, so I’m going to talk to you about the importance of soul. Because the best writing, the writing that moves, excites, commiserates, calms, saddens or breaks the heart of the reader, the writing that makes them laugh and cry and gasp and sigh and pump a subtle fist at their waist in celebration is the writing that bleeds on the page.

It’s the only way I know how to write and the only thing I like to read. I’m not interested, as a writer, in intellectual gymnastics. I am not bothered by experimentation for its own sake. I cannot spend time with characters who are cyphers for an author’s grandstanding political point. I want your blood on the page.

Because otherwise, what is the point of this big undertaking? Why write a novel? A novel is as the old saying goes, a sculpture you’ve made after many attempts to shovel sand into a box. A novel is a moment in time, a mirror, a window, a powerful way of understanding the world and the people in it. But also, a novel is a piece of your soul, on the page, for everyone to hold within themselves. It is the way you see the world and the way you see yourself and the way you see us. It’s your interrogation of the universe.

I first started writing my third novel, The One Who Wrote Destiny in 1999. I was hung up on a story I’d heard about my family. My uncle had fought a landmark legal case in the late 60s and had in the process done something to make lives better for non-white people in this country. He stood up against a piece of every day racial discrimination and condemned it. It went to court and while the decision didn’t go his way, the entity in question change a company policy they held. As one man, he made a difference and made my life easier. What a hero. I wanted to write a book about him. All I had to go on were summarised snapshots of conversation about what had gone on. It wasn’t a stoy because I was telling someone’s story, not my own, and I was telling it as factually as I could. I wrote 10,000 turgid words and gave up because it was such a disservice to my uncle.

Years later, I realised that what I was lacking was characters, so I tried again. This time, I made the characters big, larger than life, filled with foibles and slapstick reactions. I made the action farcical and I wrote with whimsy. Again, it wasn’t working. I showed it to my then agent and her assistant gave it the death knell. Her reply was akin to a cut and paste rejection for an unsolicited manuscript rather than a thoughtful response to a book by a client her boss represented. Humiliated, I parted ways with the agent and parked the book.

Years after that, I found myself on a lot of trains, to and from venues where I’d rock up, talk about The Good Immigrant and come home. Something happened on those train journeys home. Having spent an entire evening talking about racism, and feeling on edge because it’s hard to talk about the trauma of such things night after night, I found myself always heading home to my children, on a late train, two hours or so to myself, and I would feel vulnerable and stressed and I would comfort eat and write my novel. The vulnerability and depression I was feeling at the time unlocked something in me. I knew what I needed to do to make the book good. Now it was called A Man Without A Donkey.

I realised what these characters needed. They needed me to bleed on the page. Often we think about giving our characters wants and desires, and stakes. What will it mean for them if they don’t get what they want or need?

What about the author? What are my stakes? If I didn’t write this book, what would it mean for me? A friend once told me that the way he considers a new project is to ask himself three questions: does this stretch me? Does this stretch culture? Is me, doing this, the difference between it happening and not?

Answering the last question shook me. If I didn’t write this story about my uncle, and about the intergenerational conversation I wanted to have about immigration, then who would write it? And would they write it with my unique take and worldview?

If I didn’t write it, it wouldn’t exist. Those were the stakes for me. It became life or death and I wrote the book, on those trains, putting twenty years of expectation about what it could be into the book. And I ended up with my third novel. One where I said everything I needed to about immigration.

I always say - I gave it my all - about all my books. And it’s true. It was true of my third novel and every one I’ve written. It’s especially true of the memoir because on the memoir, I cannot hide the emotional truth behind fiction, behind made-up people occupying made-up spaces. I have to put the emotional truth front and centre and curate the events from my own life in order to show it. That’s what Brown Baby is. My blood on the page. It means that whatever anyone says about it, I know that I put everything into it. And it was life or death stakes writing it. It stretched me to write it, and it’ll stretch culture by widening the conversation on some of the themes discussed and if I hadn’t written it, then who would have done?

So, my challenge to you is to bleed on the page.

Write each thing you work on like it’s life or death. Because these works will exist forever, and if they contain small chips of our soul within them, then we will make our mark on the world. Don’t write to play intellectual gymnastics. Write like you are communicating with the world, all your joy and pain and it was the only book you could have written in that instance.

Nikesh Shukla will be with us for a live session at The Novelry on Monday 1st March.

He is the author of Coconut Unlimited (shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award), Meatspace and the critically acclaimed The One Who Wrote Destiny. He is the editor of the bestselling essay collection, The Good Immigrant, which won the reader's choice at the Books Are My Bag Awards. He is the author of two YA novels, Run, Riot and The Boxer. Nikesh was one of Time Magazine’s cultural leaders, Foreign Policy magazine's 100 Global Thinkers and The Bookseller's 100 most influential people in publishing in 2016 and in 2017. His memoir Brown Baby: A Memoir of Race, Family and Home was published this month, February 2021.

'Brown Baby is a beautifully intimate and soul-searching memoir. It speaks to the heart and the mind and bears witness to our turbulent times.' - Bernardine Evaristo, author of Girl, Woman, Other

February 13, 2021

It's a Love Story.

'Marry me, Juliet. You'll never have to be alone.'

Taylor Swift.

The end of solitude? Or a value choice? What's behind a love story? In a time in which we are all ragged, estranged, and feeling peculiarly close-to-the-edge sentimental, our blog this week explores a different kind of love story. One in which you can make peace with yourself. So if the events of the last year have left you in a bruised and battered relationship with yourself, a 'golem' as one writer recently described it, then here's hope. Happy Valentines, writers.

From the Desk of Emylia Hall.

There’s a passage in the brilliant closing chapter of Jess Walter’s Beautiful Ruins which goes:

‘This is a love story, Michael Deane says. But, really, what isn’t? Doesn’t the detective love the mystery, or the chase, or the nosy female reporter, who is even now being held against her wishes at an empty warehouse on the waterfront? Surely the serial murderer loves his victims, and the spy loves his gadgets or his country or his exotic counterspy.’ And on it runs …. ‘… and the zombie – don’t even start with the zombie, sentimental fool; has anyone ever been more lovesick than a zombie, that pale, dull, metaphor for love, all animal craving and lurching, outstretched arms, his very existence a sonnet about how much he wants those brains?’

By Jess Walter’s reckoning, all of my novels are love stories – and I’m on board with that. However, there are two that squarely occupy that space: A Heart Bent Out of Shape and The Sea Between Us. In both cases the story was informed by my relationship with the subject matter: simply, I had an abundance of feeling, and I wanted somewhere to put it. My writing was driven by wish fulfilment, not so much for the trials and tribulations of my characters but for the worlds they moved in. And both stories started with place.

When I was a university student, I spent a year in Lausanne. I first fell in love with the place from a description in a guidebook – ‘the Swiss Riviera’ – and a picture of crystalline peaks and blue water and rising spires. I partly chose to study at York because of the connection between the two universities, and from the moment that I arrived on campus as a first year, I was fixed in my ambition to get away from the place and spend my second year in Switzerland. On the English Literature course there were only a handful of ‘study abroad’ places available, but by sheer persistence I managed to bypass the selection process; I think the Flaubert-obsessed scholar in charge of the programme just wanted to get on with his own writing instead of repeatedly answering his study door to me and my questions. The year in Switzerland turned out to be – perhaps un-novelistically – everything I’d dreamt of.

Lausanne was my first true taste of freedom; I had a shoe-box room with an exquisite view of lake and mountains, and a whole city at my feet. Writing this now, in lockdown, I feel almost breathless remembering the discovery and adventure and shimmer of it all. The cold concrete smell of the metro station, the superlative almond croissants bought from an outwardly-unpromising kiosk, the sophistication of the campus cafeteria where a chocolate was served alongside your coffee. Standing at the bus-stop with my snowboard, weekends spent falling down slopes with bluebird skies above and waking up the next day, every ache and pain a badge of honour. The lakeside at night, the lights of Evian twinkling on the other side. The grand old hotels where I used to go for coffee and read and eavesdrop. The clubs where we danced to French hip-hop, and Swiss boys shouldering in with their snowboard jackets and goggle marks, charming without even trying. I could go on and on, but I won’t – after all, hah, I had my novel for that. When my year was finally up, the date stamp in my residence permit unequivocal, I went to collect an essay from one of my tutors. She was a rather stern Swiss-German woman with a tightly-woven bun. I said how sorry I was to leave, and I must have gushed, because her whole face softened, and she asked me if I’d fallen in love. I replied, with all the earnestness of 20-year-old-me, that yes, I had indeed. I’d fallen in love with Lausanne.

A Heart Bent Out of Shape is my love letter to that year abroad. Yes, it has a boy meets girl storyline (actually, girl meets significantly older and undoubtedly problematic university lecturer) but, really, it’s all about finding your wings and tasting possibility. And the relationship that endures is with a place, not a person.

The Sea Between Us is perhaps a cleaner-cut romance, but one, again, born of my connection to place. It’s set in the wild and wind-blown reaches of Cornwall’s far west.

The idea for The Sea Between Us began with an image of two people: a girl and a boy sitting atop a granite rock, the Atlantic crashing and rolling before them; I knew it was their story that I wanted to tell. I’d described it to my agent as ‘Wuthering Heights meets One Day,’ wanting to blend an elemental landscape with a contemporary love story – but I didn’t exactly stick to that pitch. It ended up as a softer, sweeter tale, about the ebb and flow of relationships, motherhood, and creative discovery. While what happens between Robyn and Jago is the main route of the novel, the scenic diversions are what give it its flavour: the pull of the sea that Robyn feels when she moves to London and how she seeks to capture it on canvas, how the claustrophobia of early motherhood makes her long for salted air and the inside of a wave. I took all the things I love about Cornwall – the sea, the surf, the art – and I filled my novel with them. My writing desk was scattered with seashells, Kurt Jackson art books, and a block of coconut surf wax that I sniffed ritualistically. And I headed west whenever I could.

Partway through the first draft of The Sea Between Us I became pregnant, and it felt serendipitous that I could now write my experience into the book; even in the earliest jottings for the novel, Robyn was (spoiler!) always going to have a baby. I was meeting with my agent and editor in London, a week away from finishing the first draft, when my waters broke: I was four and a half weeks off my due date, and it happened on the train back to Bristol (a journey I mostly spent hiding in the toilet, talking through the door to a kindly train steward). My son was born the next morning and I remember being in the middle of labour and thinking, ‘yeah, I’m going to have to rewrite that birth scene – it doesn’t touch the sides.’ During interminable night-feeds, I’d transport myself to the cove I’d created, a place Robyn calls Rockabilly. I’d close my eyes, against the ache of mastitis, my son’s uncertain latch, and hear lapping waves and feel comforted. Writing has always been a secret garden for me, but as a new mother I cherished it more than ever: it was freedom and control, escapism and discovery. Every day I took my babe out in the buggy for long looping walks across the city, seeking out water, down to the harbourside and through the boatyards, along the river path beneath the suspension bridge and out to where the city gives way to fields and forest; all the time I was writing in my head, inhabiting my characters, stopping to tap notes into my phone or scribble in a notebook. I felt elevated, when I might have been dragged down. And that sense of being rooted and empowered through a creative pursuit is the most important love story in The Sea Between Us; I took how I felt about writing and made it into painting for Robyn.

I’ve never thought about it this way before, but my love stories are really about women becoming truer, more fully-realised versions of themselves. Yes, they meet men that beguile them; there’s the push and pull of all romance novels, the misunderstandings and the words not spoken. But my heroines’ most potent desires are for a different kind of life – a more sparkling, adventurous life, a more creative and authentic life – and in the end that life is one they find for themselves. Albeit with a kiss or two along the way.

If you're writing a story with a big heart, our tutor Emylia Hall might be the safe place, and wise and encouraging partner-in-art, you're looking for. More about our author tutors here.

February 6, 2021

Writing Dystopian Novels

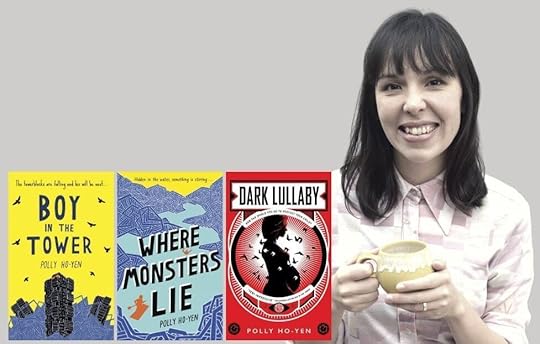

From the Desk of Polly Ho-Yen

I’ve written a dystopia.

It feels like a confession I have to make. I see their eyes glaze over a little when I tell people because really, right here, right now, why would we want to sink ourselves into a world with an inescapable, nightmarish quality built into its core?

I didn’t mean to do it, I sometimes say, remembering how it began.

It started with a sentence: ‘Mimi was three the last time that I saw her’. I only knew two things as I blindly wrote these words: this story was set in a world where parenting was being monitored to an excessive degree and the mother, my protagonist, would be separated from her young daughter.

I shudder now to remember how little I knew going in.

I’d had the idea about parenting being monitored after experiencing school inspections as a teacher. They’d filled me, and my colleagues, with such dread, cloying paranoia and a constant sense of failure that placing a kernel of this into the heart of a story emotionally magnetized me towards it, even though at this point I was not entirely sure what I was writing.

The opening chapter came easily: a birthday scene, but with none of the usual jollity as the mother knew that this would be the last time she would see her girl. The scene closes as her daughter blows out the candle on her cake to the sound of someone rapping hard on their front door. (I didn’t know for quite some time the mechanics behind exactly why they were being separated.)

I was working on some other books at the time – middle-grade novels and some projects for younger readers – and in that period I started a new job which meant my husband and I moved from London to Bristol and we started renovating a house in the south of the city. We also began talking more seriously about starting a family together as we’d been trying for a while with no luck. But I kept circling back to that tentative beginning - a mother and daughter, a birthday that was a goodbye, a stranger at the door - and I grew it whenever I could.

I knew that in the writing of that first chapter and from my vague, unplanned thoughts for a premise, I had created a huge number of questions for myself. As I started down the long road of plotting and finding solutions, I kept getting stuck on one question in particular: I needed a good reason why parenting was now under this intense scrutiny. As I do whenever I’m stuck with a plot problem I wrote down every reason I could think of – however bad, ludicrous or unbelievable it might seem – but I couldn’t find one that felt right.

At the same time as I was attempting to untangle these thoughts, my husband and I watched by as our friends became parents. Twos became threes, all around us. It seemed to happen gradually and then all at once; a flood of babies. We attended a friend’s birthday party and realised afterwards that we were the only ones there without a child. I learned not to let my face fall, to reply with a steady voice when yet another person would ask me if I had children. I felt each month land as my body would turn with period cramps and I felt a heaviness and a release twist inside me.

My husband and I went to the GP who looked shocked when we told her how long we had been trying for a baby. She went through our health histories and we were referred with a startling efficiency to a specialist. After that, we went through a number of tests and though we braced ourselves for bad news, each time the results came back clear. There was no reason why I wasn’t falling pregnant. It should have happened by now, our doctor said, there’s something else happening here, something that we don’t understand. We were told that out of everyone who experiences subfertility, two-thirds of this group learn the reason why it’s happening. And there’s the other third who, like us, never know the reason why. ‘Unexplained subfertility’ is the term our doctor used.

The answer for my novel was something that I was facing day after day: what if the number of cases of ‘unexplained subfertility’ increased? No one understood why people were experiencing it now and so if that number grew, I fathomed, it might still remain a mystery. And if the children that were born were so few and so precious then wouldn’t it naturally follow that parenting would become more strictly monitored? I’d finally arrived at the crux of my dystopia: the world in my novel would be afflicted with unexplained subfertility and so the women in it would have to go through aggressive fertility treatments in order to become pregnant; families, here, would be rigorously monitored.

I had many more hurdles to clear before this book would emerge into the light (which if I tried to cover in any detail would make this blog piece about as long as the finished book.) I built the story persistently over many drafts with a lot of help from a very committed agent and an incredible, guardian angel editor. I can’t help thinking now that if I’d followed more of the guidance around planning that The Novelry teaches then I wouldn’t have had to unknot and rewrite my story as many times as I did. But the first chapter remains the same – it’s still the birthday scene I imagined, only Mimi’s ended up much younger in the final version. She’s the same age in fact as my daughter whose birthday is next week. Our girl arrived last year after fertility treatments we received at the Bristol Centre for Reproductive Medicine. She also came after a lot of persistence and help.

I’ve just had an email from my editor telling me that finished copies are on their way. She was the one who found its title of ‘Dark Lullaby.’ I can’t wait to hold a copy in my hands, to have actual physical proof that it’s finished. Every book I write teaches me something and this one felt like a lesson in endurance and belief. And I can’t help thinking that I will return to dystopia for my next novel.

Here are five reasons why I feel I don’t want to leave this genre just yet and why you should consider writing your own:

(Warning: Spoilers for ‘We’ by Yevgeny Zamyatin, ‘1984’ by George Orwell, ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’ by Margaret Atwood and ‘The Children of Men’ by PD James appear below.)

Utopia and Dystopia are a hair's breadth apart

Utopia in fact came first. Written in Latin and published in 1516, Thomas More first coined the phrase as the title for his work of fiction and socio-political satire – ‘a little, true book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, about how things should be in a state and about the new island Utopia’. More portrays a socialist idyll of hospitals and shared food. (Not all the details are so homogenously equal but considering the time it was written, there’s a lot that seems remarkable.) But utopia literally means ‘nowhere’, from Greek ou ‘not’ and topos ‘place’; this was somewhere that could not be found.

Moving on to what’s considered the first dystopian novel, ‘We’ (1921) by Yevgeny Zamyatin, one emerges in One State, a world of glass boxes for homes, where life is managed and contained by The Benefactor. Perhaps it looks like a utopia – unless you happen to be unlucky enough to be living within it. The protagonist D-503 only has to dream to be considered mentally deficient. But by the end of the novel, he’s submitted to an operation to remove his imagination and seemingly believes himself to be in a utopian state of mind:

‘No more delirium, no absurd metaphors, no feelings,—only facts. For I am healthy, perfectly, absolutely healthy.... I am smiling; I cannot help smiling; a splinter has been taken out of my head and I feel so light, so empty! To be more exact, not empty, but there is nothing foreign, nothing that prevents me from smiling. (Smiling is the normal state for a normal human being).’

As Naomi Alderman, author of ‘The Power’ puts it: ‘Utopias and dystopias can exist side by side, even in the same moment. Which one you're in depends entirely on your point of view.’

I find considering utopia and dystopia in this way, in relation and conversation with each other, a rich thinking point. It’s an incredibly useful approach to thinking of how a character’s internal journey will develop throughout a story. How might their point of view alter so much that what at first would appear as a dystopia to them may at the end feel utopic? What would have happened to them for such a change to occur? Would it be something as drastic as the operation from ‘We’ or the imprisonment and torture of Winston in Orwell’s ‘1984’? Or perhaps a changed point of view could come from something learned.

The Channel 4 series ‘Utopia’, a show about an engineered virus that would sterilize 95% of the human race to avert overpopulation, illustrates this journey masterfully. From the beginning, you are wholly on the side of the small group who are slowly uncovering (and who are against) the plot of the virus. But as the series develops, you come to consider the antiheroes’ point of view and understand their motivations. Their villainous masks drop as they become so wonderfully human: earnestly trying to do what they think is the right thing, in the right way. A character switches sides, joining the team who want to spread the virus. It’s a momentous yet wholly believable scene.

Another way to look at how a character views the world as a utopia or a dystopia is through the placement of power. Dystopias often follow a totalitarian society where the power lies in the hands of those in charge – the Big Brother of ‘1984’, the Benefactor of ‘We’, the Commanders in ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’. Or, as Naomi Alderman shows us in ‘The Power’, a dystopia might explore society during a period of change. In ‘The Power’, which side of the utopia/dystopia coin you land on is dictated by the biology of your sex – the ability to release electrical jolts from their fingers emerges for women only as they become the dominant gender.

Where the power (with a small ‘p’) lies and, importantly, what you imagine power looks like in your story, is key to whether your character’s world is either experienced as a utopia or a dystopia. In my novel, I knew my protagonist would choose to have a child in spite of the overwhelming pressures that the parents in her world encountered. I felt her powerlessness from the beginning. But as I wrote, I found her fighting back with every word.

Writing a Dystopia can help process your anxieties

When I was in the middle of ‘Dark Lullaby,’ I’d be waiting in the fertility clinic for growth scans of the follicles in my ovaries and then going home to write about a woman who gets pregnant despite all the odds. Though it seems almost ridiculous to admit here, I still felt a distance between what was happening and what I was writing. My dystopia felt like it was actually serving as an escape from the growing, gnawing worry that perhaps despite everything we tried, we would still not conceive.

In fact, it was much more than an escape, although I couldn’t quite see that at the time. Ray Bradbury said of science fiction that the genre ‘pretends to look into the future but it’s really looking at a reflection of what is already in front of us.’ I feel the same could be said of dystopia. Though this writing was for me a waking workout of a brutal ‘what if’ ahead of me, it was also a facing up to my present. It pushed me further than I could bear to go than in conversations with my husband, loved ones and even myself. But I was able to contain it: in a turn of phrase, a sentence, a chapter. I could do all the work of processing it through the safe lens of a story and a character who was not myself.

As things increasingly started to feel further and further from my control as we progressed with fertility treatments, writing a protagonist who was taking action was a tonic like no other. At this point, I was writing how the mother was fighting to get her daughter back. She was finding inner strength, and so was I. I was writing a made-up story but I was also telling myself a message: you can do this.

Burn your anxiety out by writing a dystopia, the tagline could read. Of course, I’m not holding up scientific evidence here and this is very much born from personal experience but the more I write, the more I’m struck by how, without any design, the story I’m writing forces me to examine unresolved feelings and push them into the light. In a dystopia, you can end up exploring your very worst fears but by writing through them, they can become manageable.

You’ll never know your characters better than by writing them into a dystopia

If you truly want to know who your characters are then write them into a dystopia. If you want to know how weak they are, how strong they can be, what truly drives them forwards then this is the genre for you. The intrinsic nature of dystopia means that characters are pushed to their very edges and forced to confront what really matters to them.

As ‘1984’ shows us, this can lead to unpleasant awakenings. Orwell demonstrates this through his protagonist Winston to devastating effect. As Winston is interrogated and imprisoned by the Thought Police, the conflict within him to submit or to fight he holds alongside his feelings for Julia, whom he is trying not to betray. Reading Winston’s internal struggle during his imprisonment lies in sharp contrast to the following interaction between Winston and Julia when they both meet again:

'I betrayed you,' she said baldly.

'I betrayed you,' he said.

She gave him another quick look of dislike.

'Sometimes,' she said, 'they threaten you with something you can't stand up to, can't even think about. And then you say, "Don't do it to me, do it to somebody else, do it to so-and-so." And perhaps you might pretend, afterwards, that it was only a trick and that you just said it to make them stop and didn't really mean it. But that isn't true. At the time when it happens you do mean it. You think there's no other way of saving yourself, and you're quite ready to save yourself that way. You WANT it to happen to the other person. You don't give a damn what they suffer. All you care about is yourself.'

'All you care about is yourself,' he echoed.

- ‘1984’

Orwell forces Winston (and Julia) to confront their own limitations and in doing so, these characters become completely vulnerable, utterly knowable.

Or consider a different approach seen in Offred in Atwood’s ‘A Handmaid’s Tale.’ If the military coup had not happened and we instead saw her as a mother of a young family, what would mark her out? Yet in Atwood’s telling of her enslavement, her ordinary becomes extraordinary. The opening chapters take us through Offred’s everyday; her waking in a bare bedroom, a shopping trip. The reader finds Offred in an altered world and begins to grasp that beneath her quiet demeanour, she is forced to walk a tightrope.

For protagonists in a dystopia will often feel themselves being watched. ‘We’ imagines a society watched over by The Guardians. In ‘1984’, it’s The Thought Police. In ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’, it’s The Eyes. The writer of dystopia can be privy to not only their characters’ selves being stripped away but scrutiny of their outward projections too. It’s a harsh examination of a private and public life like no other. The surveillance of the protagonist and their allies as they try to resist the tyranny within a dystopia looms large in these books; it becomes a many-faced yet faceless character all of its own.

As in the ‘Utopia’ television series, dystopia also pushes you to consider the antagonist closely. In my novel, I created Enforcers who worked for an organization named ‘The Office for Standards in Parenting’ or OSIP – a team mobilised to monitor parenting standards judiciously - and I felt myself irresistibly drawn to exploring who might become part of this observing army. I pondered on how their motivations to become an Enforcer would feel believable, inevitable to the reader. How could it be a person just like you or me, or your neighbour? How could I know them so well to make this decision feel realistic and plausible?

Whichever way you tackle the protagonist’s journey, the stakes naturally fall high and jagged in a dystopia; you will not fail to find that story, story, story that will keep your characters turning, and your reader with you.

Dystopias are all around us

In ‘Dark Lullaby’, it is impossible for families not to come under the scrutiny of the organization that monitors parenting, OSIP. The parents that I imagined suffering in my story were trying their best, they were doing a good job, but in the eyes of this organization, it was not enough.

When I tell a parent about this premise, they blanch. Imagining parenting where you’re being watched, scrutinized and openly judged sometimes doesn’t feel so far away from the present, unfortunately. It can be felt in the smallest of expressions, in the silence of a response or in an irate social media post, after you’ve shared a parenting decision you’ve made: that you’ve sleep-trained, that your child plays with your phone, that you cut their finger when trimming their nails using the wrong sized clippers … the list is endless. In ‘Dark Lullaby’ pressing into that judgmental mindset, formalizing it and dressing it up into a government organisation that existed for the good of children transformed this experience from the everyday to the terrifying.

I like that one of Atwood’s rules for writing for ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’ was not to include any events that had not happened somewhere, at some time, in her plot.

'If I was to create an imaginary garden, I wanted the toads in it to be real … No imaginary gizmos, no imaginary laws, no imaginary atrocities. God is in the details, they say. So is the devil.’ – Margaret Atwood

Placing your story in reality and then giving it a hard (or gentle) push over the edge into fiction is an incredibly useful tool. It floods your prose with plausibility but gives you, as I’ve touched on earlier, a safe distance to explore what’s happening or happened, too.

And should the circumstances that surround us become overwhelming, if our here and now feels closer to a real-life dystopia than feels comfortable, dystopian fiction can also provide us with a route forward. There’s the possibility, in such a moment, of allowing a sense of powerlessness to overcome us. Writing it into a dystopia challenges this. Imagining what your characters would do in an impossible situation forces you to ask what you would do, how far you would go and ultimately, who might you need to become? Dystopias offer us this agency.

Happy Endings aren’t the be-all and end-all

Winston emerges from Room 101, a broken man. Offred the handmaid is bundled into a car, perhaps by The Eye. D-503’s imagination is removed.

We don’t find happy endings in dystopias. But I am drawn to thinking about the ways that these dystopian endings are evolving.

In ‘We’, D-503’s submission to The Benefactor feels absolute:

‘But on the transverse avenue Forty, we succeeded in establishing a temporary Wall of high voltage waves. And I hope we win. More than that; I am certain we shall win. For Reason must win.’

- ‘We’

This erosion of self is taken even further by Orwell:

‘But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.’

- ‘1984’

This contrasts with the ambivalence in the ending in ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’, as Offred is taken either by members of the secret police or of the resistance:

‘And so I step up, into the darkness within; or else the light.’

- ‘A Handmaid’s Tale’

In ‘The Children of Men’ by PD James, as Julian notices that Theo has taken the ring to become the Warden of England, we see their internal struggle:

‘Julian looked up at him. For the first time she noticed the ring. She said: “That wasn’t made for your finger.” For a second, no more, he felt something close to irritation. It must be for him to decide when he would take it off. He said: “It’s useful for the present. I shall take it off in time.” She seemed for the moment content, and it might have been his imagination that there was a shadow in her eyes.’

- ‘The Children of Men’

PD James has said of this ending that ‘the detective novel affirms our belief in a rational universe because, at the end, the mystery is solved. In ‘The Children of Men’ there is no such comforting resolution.’

This was something that I wanted to carry into my final scene in ‘Dark Lullaby’. Though what I wrote may be viewed as bleak, it felt to me more like a safeguarding – the ability to be with things that should not be, and yet to survive and seek a way forward.

Perhaps in the way that our dreams and nightmares show us that we can survive the worst of things, writing dystopia can do the same.

Polly Ho-Yen is a tutor at The Novelry. If you'd like to explore your idea, and get a writing comrade like no other, sign up for one of our online writing courses and choose Polly as your guide.

The Novelry Team - now a 'super' squad.

More about us all here.

January 30, 2021

Meet the Agent - Silvia Molteni.

Silvia Molteni is a literary agent at PFD. Peters Fraser + Dunlop (PFD) is one of our twelve partner literary agencies. We submit our writers work in preference to these warm-hearted, reputable, leading agencies who act on behalf of authors globally to secure enviable publishing contracts with The Big 5 publishers worldwide. It's a mutually rewarding arrangement. Our partner agencies look forward to seeing our work, as it's of a reliably high standard, and in return they come back to us like lightning with their thoughts. No slush pile for our writers.

Our agents pop into The Novelry from time to time to give our writers a heads up on what's hot in the publishing world and how to ensure your novel is firing on all cylinders, and the wonderful Silvia Molteni will be joining us Monday 1st February at 6pm for a live Q&A session. A chance for our writers to get their questions answered and meet the agent in person. Putting faces to names is a huge pleasure for writers and agents and it's all part of our careful process of 'turning professional' at The Novelry.

From the Desk of Silvia Molteni.

I am Head of Children’s Books at PFD. I started my career in publishing at PFD ten years ago and founded the children’s books department in 2015. I call myself very lucky to be able to do something I love for a living and to work for an agency that wholeheartedly supports the growth of the children’s books department.

Like everyone else who works in publishing, I can of course tell you that I love books and stories; nonetheless, my heart lies with children’s and young adult titles. Working specifically with children’s books has been a dream of mine since I can remember and it is something I treasure and never take for granted.

Children are smart, brilliant, inquisitive, funny, amongst so many other things; their minds are open to what’s different, they rarely judge and they are sponges. And at the end of the day, they are the future. What could be more important than writing for them or, in my case, helping the right stories finding the right home to then go on and reach the hands of children and teenagers?

My mission as an agent is championing strong, brave, smart and exciting stories, as well as providing children and young adults with books that offer not only escapism, adventures, entertainment and tons of imagination, but also representation and information. I strongly believe that with this job comes responsibility; equally, I feel that children’s books writers should always keep their audience in mind and never let them out of their sight as they’re crafting their novel.

As an agent, I am actively looking for Middle-Grade novels, strong and diverse voices with brave narratives and contemporary and realistic settings; edgy, funny and moving Middle-Grade fiction. I am also looking for YA fiction across all genres, but on my wish list at the moment is finding a great psychological thriller. I am also on the hunt for non-fiction books aimed at children and YA – from memoirs to manuals, popular science and humorous books.

Generally speaking, across MG and YA fiction, I am drawn to voice-driven and character-driven narratives, LGBTQI story-lines and characters, endearing narrators, magical realism and upmarket literary fiction. What I truly love is gorgeous writing and voice, voice, voice! I never get tired of saying this. (I’m much less drawn towards plot-driven and ambitious world-building narratives.)

Regardless of my personal wish-list, through the years working across children’s and YA books, I’ve seen a number of trends crop up in my submission pile. I find that these are normally dictated by what is successful during that specific timeframe in the children’s and YA books market.

We went from YA love-triangles, around the same time that vampires and werewolves started to populate all of the teen fantasy submissions; following that, the Hunger Games propelled a series of dystopian settings (a concept too close to the bone these days, sadly!), as well as feminist, empowering protagonists (those are always welcome by the way, regardless of trends).

At one point, submissions shifted towards contemporary realistic settings and coming-of-age stories, often featuring terminally ill protagonists, à la John Green. The rom-com phase followed, thanks to To All the Boys I Loved Before finally landing on Netflix.

We’re now seeing an increasing number of psychological thrillers and horror books written for teenagers, on the back of the success of titles along the lines of Good Girls Die First, A Good Girl’s Guide To Murder and Harrow Lake. There have been countless of trends throughout the years, not necessarily in this order, but nothing prepared us for the submission-inbox chaos of 2020 – which I’ll address further below.

The issue with trying to follow these trends as a writer is that they don’t often last long and market saturation occurs quickly; around the time the “new trend of the moment” starts to take the YA world by storm, the previous one becomes obsolete and overdone. For this reason, writing from the heart and telling the story that you are most passionate about, regardless of market demands, is always valid advice. A good story remains a good story, regardless of whether it’s set in a faraway land, a dystopian reality, or in our own contemporary world.

Having said that, there is no escaping that YA remains the literary genre that is most dictated by current bestsellers and movie adaptations, which is something that automatically turns it into a niche segment of the market, when in reality it should be one of the most widely read, by teenagers and adults alike. The potential and the variety of stories that you can tell aimed at a YA audience are endless, so if you feel the urge to tell a particular story, I’d say go ahead and do it.

Middle-grade is, to some extent, a breath of fresh air compared to YA, mainly because it is the healthiest sector of the children’s books market – even through 2020; in fact, children’s books sales have shown resilience during the coronavirus pandemic due to the increasing demand from parents for more content, both within the trade and educational space. And this is also true across foreign markets. Publishers are constantly on the hunt for a good middle-grade stand-alone or series, so I’ve always felt that there’s more space for freedom when it comes to exploring different genres, concepts and settings for this younger audience. Nevertheless, the number of middle-grade books that hit my submission inbox is fairly small, compared to YA.

If I had to come up with a theory to explain such discrepancy, I would point the finger at the general misconception that YA is the best and easiest genre to write for, if you have it in your mind that you want to write for a younger audience and you want a good chance at becoming a published (and successful) author. This is due to the fact that YA naturally has the potential to cross into and blend with adult fiction most of the time. It may feel a million times harder to try and capture the voice of a ten-year-old in an authentic way; not to mention the gap between the personal experiences of the writer compared to those of their audience.

If I were to analyse my submission pile right now, first I'd have to admit that it is slightly out of control! (Please bear with us agents when it comes to reading and replying to your submissions! Please don't chase us, unless it’s to simply flag that you have interest elsewhere!) Second, I’d have to say that the majority is YA, a smaller portion is MG and the remaining ones are Picture Books. I don’t make a habit of signing picture books, so I’ll leave them out of this blog (they would take up a whole separate discussion anyway); while I would actually welcome more chapter books and middle-grade novels on the younger end of the age spectrum.

As for genres, we have indeed seen a surge of fantasy submissions across both YA and middle-grade. The reason for this requires some reflection. In the first instance, I believe it is due to the fact that most of the biggest MG successes in the past year or two have been fantasy stories (think of Starfell or Nevermoor for example) and fantasy YA is always in fashion (the endless string of titles similar to The Mortal Instrument series are living proof). On top of that, I think we can safely assume that to a certain extent this is also due to an intrinsic need for escapism that comes from having lived almost a full year in the midst of a global pandemic, one lockdown after the other.

Publishers are always looking for that special book, regardless of genres and trends. More specifically, currently, there’s certainly a bigger demand for funny stories, novels with an immediate hook and a unique selling point, underrepresented voices, #ownvoices; with MG being the biggest growth area. Plus, feel-good romance, on the YA side of things.

There will come the need to capture the experiences that the pandemic brought upon children; nevertheless, at the moment, it’s a fair assumption that there’s a bigger need for hopeful and uplifting books, and especially witty stories. Humour is something that I rarely see in submissions – primarily because it’s incredibly difficult to achieve – and I would love to see more of it.

Lastly, a few tips on how to successfully query agents:

Keep your email short and straight to the point; start with introducing yourself and why you’ve selected to submit to said agent; follow with a short elevator pitch and a couple of similar books to give us a taste of genre and tone.

One short paragraph with an enticing blurb and a short writing biography should come next. Don’t forget the attachments (three sample chapters and an outline of the full book), preferably in a word document, as most kindles or E-readers don’t read pdf well – and I must say that I much prefer a separate document than having to read the sample in the body of the email. I am not a fan of spelling mistakes (then again, who is?), but I won’t be necessarily put off by a typo in my name, as much as I would be by books that are too long (for example, over 80,000 words for MG or over 100,000 words for YA) or by a query that lacks respect or humility.

I hope you’ll find this blog helpful. I’m so grateful for the opportunity The Novelry has given me to offer some thoughts to you, and I hope you will think of me when your manuscript will be ready for submission.

Happy writing!

Silvia will be joining us for a live Q&A session with our writers tomorrow, on Monday 1st February, at 6pm UK time. See you there!

The Firestarter 2021.

A competition for the best opening of a novel open to all members of The Novelry in February, annually. You need only submit your wonderful opening to your novel - to 1500 words - at our Firestarter Room at our membership site to enter, before midnight 1st March.

Our literary agents look forward to seeing our blog featuring the pitches for the novels of our top-scoring entries. It's a chance for everyone who enters to get some visibility with agents.