Louise Dean's Blog, page 9

October 2, 2021

Katherine Rundell On Writing For Children

From the Desk of Katherine Rundell

(Our guest for Monday's Live Author Session. See our forthcoming events for October here.)

Children’s fiction has a long and noble history of being dismissed. Martin Amis once said in an interview: ‘People ask me if I ever thought of writing a children's book. I say, “If I had a serious brain injury I might well write a children's book”.’

There is a particular smile that some people give when I tell them what I do – roughly the same smile I’d expect had I told them I spend my time knitting outfits for the elves out of cat hair. Particularly in the UK, even when we praise, we praise with faint damns: a quotation from the Guardian on the back of Alan Garner’s memoir Where Shall We Run To read: ‘He has never been just a children’s writer: he’s far richer, odder and deeper than that.’ So that’s what children’s fiction is not: not rich or odd or deep.

I’ve been writing children’s fiction for more than ten years now, and still I would hesitate to define it. But I do know, with more certainty than I usually feel about anything, what it is not: it’s not exclusively for children. When I write, I write for two people, myself, age twelve, and myself, now, and the book has to satisfy two distinct but connected appetites.

My twelve-year-old self wanted autonomy, peril, justice, food, and above all a kind of density of atmosphere into which I could step and be engulfed. My adult self wants all those things, and also: acknowledgements of fear, love, failure; of the rat that lives within the human heart. So what I try for when I write - failing often, but trying - is to put down in as few words as I can the things that I most urgently and desperately want children to know and adults to remember. Those who write for children are trying to arm them for the life ahead with everything we can find that is true. And perhaps, also, secretly, to arm adults against those necessary compromises and necessary heartbreaks that life involves: to remind them that there are and always will be great, sustaining truths to which we can return.

There is, though, a sense among most adults that we should only read in one direction, because to do otherwise would be to regress or retreat: to de-mature. You pass Spot the Dog, battle past that bicephalic monster Peter-and-Jane; through Narnia, on to Catcher in the Rye or Patrick Ness, and from there to adult fiction, where you remain, triumphant, never glancing back, because to glance back would be to lose ground.

But the human heart is not a linear train ride. That isn’t how people actually read; at least, it’s not how I’ve ever read. I learned to read fairly late, with much strain and agonising until, at last and quite suddenly, the hieroglyphs took shape and meaning: and then I read with the same omnivorous unscrupulousness I showed at mealtimes. I read Matilda alongside Jane Austen, Narnia and Agatha Christie. I still read Paddington when I need to believe, as Michael Bond does, that the world’s miracles are more powerful than its chaos. For reading not to become something that we do for anxious self-optimisation – for it not to be akin to buying high-spec trainers and a gym membership each January - all texts must be open, to all people.

The difficulties with the rule of readerly progression are many: one is that, if one followed the same pattern into adulthood, turning always to books of obvious increasing complexity, you’d be left ultimately with nothing but Finnegans Wake and the complete works of the French deconstructionist theorist Jacques Derrida to cheer your deathbed.

The other difficulty with the rule is that it supposes that children’s fiction can safely be discarded. I would say, we do so at our peril, for we discard in adulthood a casket of wonders which, read with an adult eye, have a different kind of alchemy in them.

Because children’s fiction offers to help us re-find things we may not even know we have lost. Adult life is full of forgetting; I have forgotten most of the people I have ever met; I’ve forgotten most of the books I’ve read, even the ones that changed me forever; I’ve forgotten most of my epiphanies. And I’ve forgotten, at various times in my life, how to read: how to lay aside scepticism and fashion and trust myself to a book. At the risk of sounding like a mad optimist: children’s fiction can re-teach you how to read with an open heart.

When you read children’s books, you are given the space to read again as a child: to find your way back, back to the time when new discoveries came daily and when the world was colossal, before your imagination was trimmed and neatened, as if it were an optional extra.

But imagination is not and never has been optional: it is at the heart of everything, the thing that allows us to experience the world from the perspectives of others: the condition precedent of love itself. It was Edmund Burke who first used the term ‘moral imagination’: the ability of ethical perception to step beyond the limits of the fleeting events of each moment and beyond the limits of private experience. For that we need books that are specifically written to feed the imagination, which give the heart and mind a galvanizing kick: children’s books.

Children’s books can teach us not just what we have forgotten but what we have forgotten we have forgotten.

Aristotle would agree (probably). In 350BC he defended the importance of phantasia; he argued that to lead a truly good life it was necessary to be able to wield fictions - to imagine what might be or should be or even could never be. Plato, who mistrusted poets and would have mistrusted children’s novelists even more, would like nothing about this essay. But defy Plato: and defy all those who would tell you to be serious, to calculate the profit of your imagination; those who would limit joy in the name of propriety. Cut shame off at the knees. Ignore those who would call it mindless escapism: it’s not escapism: it is findism.

If you enjoyed this, you can read more here with Katherine's brilliant book: Why You Should Read Children’s Books, Even Though You Are So Old and Wise, published by Bloomsbury.

Our Children's Writing Course at The Novelry was recently voted No.1 worldwide by Intelligent. Find out more about writing your children's novel with The Novelry from just £99 or $149 a month here.

October 1, 2021

How to Write a Prologue

If you're wondering how to write a prologue for your book, then whether you publish your book with one or not, the one-page attention-grabber is a great way to test your story's success and prepare your plan to rewrite it for a new fresh, bold draft, as the key ingredients will be laid out for readers from the first page.

This post will break up the steps of writing a prologue into five easy steps. Those steps are as follows:

How to Write a Prologue:

What is the question you're asking your readers?

What's at stake?

Who are we?

Where are we?

An ominous or dramatic change

What is the purpose of a prologue?

Prologues are only ever looked down upon where they're throat clearing, or a preamble that does not serve to engage the reader in the story. A good writer never wastes a reader's time. Consider the fact that with the Look Inside feature on Amazon, or whether your reader is passing by the books on a table in a bookshop, they and potential literary agents and publishers are going to start at the very beginning, with the first page. A prologue is a great way to sell prospective readers in on your novel. It's different to the opening of a novel or story, because it's got all the juicy good stuff right there, on one page ideally. The reader simply has to find out more.

Setting aside whether a prologue is fashionable or not, it makes great sense for all novels, especially those where suspense is part of your pitch. If you're writing crime, thriller, mystery or suspense you should be packing a prologue. Reel them in real fast.

// <![CDATA[

// ]]>

1. What's the question you're asking your reader?

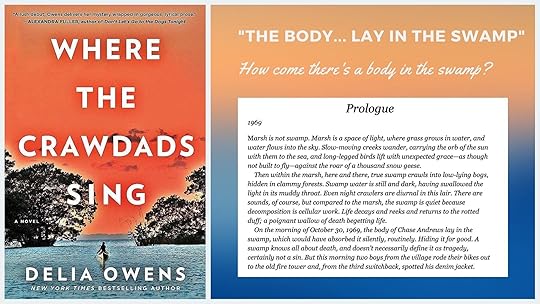

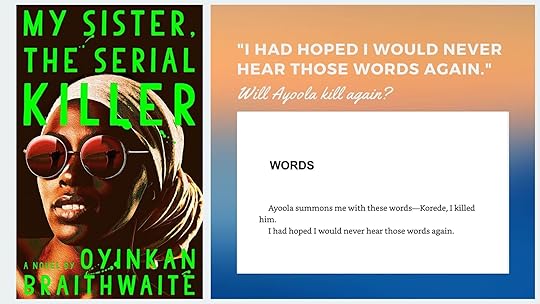

Establish this first. It's the heart of the matter of your story. It seems so simple. It should be simple. Remember the word quest is contained in question. We turn the pages on our own quest to follow our hero's quest whether it's to find out whodunnit or whether their romantic interest is worth the trouble. So write down on a small card or post-it note why your reader is bothering to read your story. Simply put. Don't make it philosophical or academic. If they want to find out how to live in peace and harmony with others, or how cryogenics works they will be reading self-help or non-fiction. But these special readers are fiction readers. They read novels. They want to be teased all the way to 'THE END'. That's your job. That's storytelling. Remember when your parent closed the book at bedtime and said you'd find out more tomorrow? Storytelling. So whether the question is 'who is Gatsby?' (The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald) or 'will Ayoola kill again?' (My Sister the Serial Killer by Oynikan Braithwaite) or 'whose body is in the swamp?' (Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens) – know what it is and keep it simple.

A good writer will keep that ball in the air, before the readers' eyes, to keep them turning the pages.

When you join us for our novel-writing course, this is one of the first questions we ask you when you join us and we guide you how to prepare your one-page story outline before you meet your author tutor, and start writing. As a team, we look at each and every plan to see what the question is to make sure you've got the essential ingredients for a great story. We don't leave stories to chance, neither should you!

2. What's at stake?

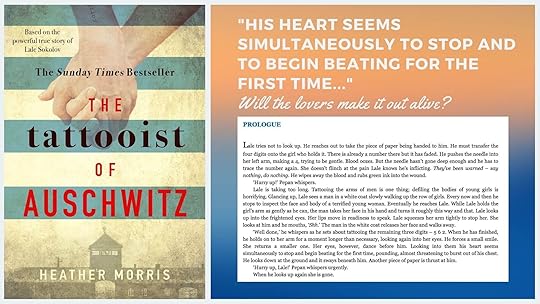

Life and death stakes make a big difference to your fortunes as an author. Bestselling novels pack serious stakes. A bestseller presents its reader with an emergency. Someone is dead, or about to die. So ensure you present clear and present danger in your prologue. If you're a smart cookie, you could pack that into your title. It's no surprise some of the bestsellers and all-time classics include the word Death or Dead! (Death in Venice, Death of the Nile, Death in Holy Orders, and the Peter James entire series of bestselling crime novels.) With the word 'Auschwitz' in the title of her global bestselling novel, Heather Morris made very clear the presence of high stakes in The Tattooist of Auschwitz.

The question we are asked in the prologue is whether these two lovers will make it out alive, and the life and death stakes are conveyed by astute and economical emphasis on the functions of the heart both as a metaphor for romance and as the organ of life. Notice too, how in the sample prologue above for Delia Owen's bestselling novel, the word death is used to make the stakes plain.

3. Who are we?

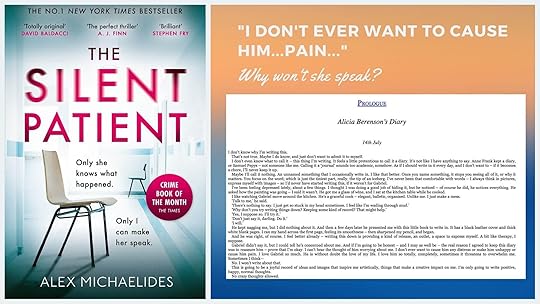

While novels can be considered individual moral journeys – our hero goes on a journey of discovery and changes throughout the course of the story via a combination of place, people and events – they are usually driven by a singular and vital relationship at the core of the book. Introduce into your prologue people we are likely to care about. Not necessarily likeable, but if not likeable frail and vulnerable. Think of the reader's emotions being aroused by being asked to care as if you were handing them a small baby or a puppy. Introduce a note of tenderness. Both the books above do this very well. Introduce the key players who occupy the sweet spot of your story. No need to give us detail, a prologue is not a first chapter. It drops us into a story that's started, and creates an impression of real people (in trouble). In the prologue to the New York Times No1 Bestseller The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides we are being asked why Alicia won't speak and the clue is given as being contained within the relationship with her husband. The word darling is used to convey care and affection and the word love is repeated a number of times. So within one single page we are introduced to the problem – an extended version of the question – given these two people have a loving relationship, why won't Alicia speak?

4. Where are we?

The setting of your novel serves the story's purpose. Many writers begin with the setting. Three of our author tutors at The Novelry say that's where they begin. A place can throw up problems. Either because it puts pressure on people to be better or worse, either they can't leave or can't bear to leave. It raises the stakes of the novel. When readers start reading they vacate the place they're in and travel elsewhere in their minds. For many readers this is one of the great (and therapeutic) pleasures of reading. Whether you're world-building – writing a fantasy, speculative, science-fiction or historical novel – or not, you should aim to drop your reader into that fully formed world with immediacy. So though you can leave the detail out of the prologue, a sense of how the setting serves the story is helpful, where the setting is especially crucial to the story.

5. An Ominous or Dramatic Change

Stories are driven by change. From the inciting incident that starts the story all the way to the surprise ending with or without a twist whereby our hero's not in Kansas anymore! Whether it's one of the two story types described by Leo Tolstoy, 'All great literature is one of two stories; a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town', a story is all about the way a little change creates big change. In our creative writing course for beginners, the Big Idea, we show you how to get your story started. When you write a book with us, we will help you develop your plot to ensure the events at least to the midpoint of the book make things harder for our hero.

Of all the five ingredients for a prologue, none is more important than the inclusion of a humdinger of OMG! What happens next? And this element of foreboding and mystery contains the first part of the prologue, the question your reader is reading to find out too. That's what makes it a prologue, not a first chapter.

If you know the question, if it's high stakes, you can give it to your reader right between the eyes and deliver it in a small but deadly prologue like this:

Writing a prologue is a great way to keep your eyes on the prize, and you could print yours out and put it above your desk while you write your novel to remind yourself of what it is about your story that means readers simply can't put it down.

Get great writing advice and stay on track to write your book with our novel-writing courses at The Novelry. We'll be there to help you plot and plan and see you through from writing the prologue to the end.

September 25, 2021

Tasha Suri – Finding Wonder In Your Writing

From the Desk of Tasha Suri

When I was still very small, every weekend I would grab my bike and meet my friend, and head to the local park. At that age, the park seemed humongous to me: vast, endless fields of green with steep hills that we’d ride up then race down, cycling faster and faster so that we’d hurtle forward at lightspeed. And at the far end of the park, beyond a wall of lacy, drooping willows, stood an emerald bridge. The bridge led, we both agreed, to a road that went to another world. I was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz then, and though the path wasn’t a yellow brick road, I was pretty sure I knew a magical road when I saw one.

I remember walking along that path once, holding my breath as I did it, the wheels of my bike clicking. I remember the serious, almost ritualistic way we had crossed the bridge, and the hush of the tree-lined path around us. It felt exactly how entering another world should have felt, strange and new and wondrous.

I went back to that park recently. Now I’m an adult, the hills don’t look so very steep at all. And the emerald bridge is just a green, graffitied bridge over railway tracks, leading to an alley between typical terraced houses. Nothing special, in truth.

It was easy to feel wonder as a child. It’s harder as an adult, when you know what things are, and the world is somehow bigger and yet smaller all at once. What was new and strange and full of possibility becomes familiar and, perhaps, dull. You’ve seen this all before.

But as writers, it is that wonder – that ability to see something else in the mundane – that drive us. When you’re a writer, you don’t just exist in the world. You want to say something about it. You want to lift up its dark underbelly, or draw back a curtain so your reader can walk with you to somewhere else, or simply crack the surface of a normal life and show all the strange and beautiful things that drive it.

As a writer of fantasy, wonder and the fantastical are my bread and butter. I like to lean in to wonder – to seek it out and articulate it and make worlds that are big and vibrant. I like to read about epic historical battles and political sea changes; to walk around museums and gaze at swords under pale spotlights, or peer at carefully preserved costumes from days long gone. I like to think about what it must have been like to raise that sword, or wear that costume. How it would feel, perhaps, to sweep down a corridor in heavy velvet under torchlight. I think about what it might feel like to have magic, or do the impossible: how it feels to dream something and make it real. All of that is wonder, pure and distilled, then splashed across the page.

But wonder can be found closer to home and be no less powerful. Think of the way it feels to fall in love, or slide excruciatingly out of it. Even a description of a piece of bread can be so real and new that it makes the reader feel as if they can taste it. A writer can make the familiar seem luminous and strange.

But how can you seek out wonder? How can you bring that childlike something into your work when you’re an adult, jaded to the way the world works? Sometimes the trick is to seek out new knowledge and experiences. Sometimes, it’s as simple as opening your eyes to wonder on purpose: to choose to see it around you in your day-to-day life. And when all else fails, the real magic of reading a good book is that it has the power to fire up your imagination and open up a different world for you. When you lift your head from the page, it’s like putting on new lenses. For a little while, everything is new and fresh, full of possibility.

When I visited the park as an adult, I did cross the emerald bridge. I went into the alley and walked through it. Instead of being disappointed that I didn’t have a child’s easy awe anymore, I looked at the trees lining the alley, bending inward like an arch, and the way the light broke through their leaves. And I listened to the hush around me, and after a moment I felt a little of that old magic creep back.

This could be a portal to another world, I thought. I wonder what kind of story could begin on a road like this one?

Our new author tutor, Tasha Suri is the award-winning author of The Books of Ambha duology (Empire of Sand and Realm of Ash) and the epic fantasy The Jasmine Throne. She has won the Best Newcomer Award from the British Fantasy Society (2019) and has been nominated for the Astounding Award and Locus Award for Best First Novel.

When TIME asked leading fantasy authors—George RR Martin, Neil Gaiman, Tomi Adeyemi, NK Jemisin and Sabaa Tahir to compile a list of the 100 most fascinating fantasy books of all time, dating back to the 9th century, they chose Tasha Suri's Empire of Sand to be on their list.

Our Classic Course at The Novelry is your portal to wonderment. Take the time to go through the rabbit hole to find the garden of creation, with 45 'mind-blowing' lessons to develop your big story idea in 2021. From £129 or £165 for 2 months. Start today!

The Novelry is celebrating a new website, new author tutors, editors and a new course! Explore the website to find out more. Subscribers to our blog will receive a special gift, vouchers worth £150, for use at our site today only! Let your friends know by sharing our Tweet.

You must be subscribed by noon GMT today 26th September 2021 to receive the vouchers.

September 18, 2021

How to Grip Your Readers

From the Desk of our Author Tutor Jack Jordan.

I can still vividly remember the day a single book changed my life.

I was shut away in the family living room, aged twelve, ripping through the pages of Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses with such vigour that I’m surprised I didn’t tear them from the binding. I should have seen the impending tragedy coming, what with it being a modern take on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, but every book I had read before had tied up the endings so neatly and conveniently that I expected the story to swivel at the last minute, and end in the only way I knew: tied up in a perfect bow, with the villain getting their just deserts, and the protagonist getting their Happy Ever After. But the ending Blackman delivered changed my view of storytelling forever. I stared, slack-jawed, as I re-read the last page, with my heart racing and my young mind reeling with emotions and questions. Blackman doesn’t tie up the end of Noughts and Crosses in a pretty, neat bow – she gives the reader the ultimate gift. She makes us feel.

As I sat staring at that infamous last page, a fervent need ignited me. As a reader, I no longer wanted the cookie-cutter ending, or the perfectly likeable characters. I wanted flaws. I wanted pain and tragedy. I wanted to feel every emotion I possibly could. Even now, all these years later, I long for that same sucker-punch of emotion, and feel disheartened when I sense the pretty pink ribbon slithering through the last chapter of a book, ready to be bowed. As a writer, my mind opened to a whole new way of storytelling. My mind was practically exploding with new possibilities. There wasn’t a rule to deliver a Happy Ever After like I had been told or assumed. I could carve my own way, deliver impacts of emotion like Blackman had me. Over the years, I have come to realise that it is the books that divert from the Happy Ever After, either partially or totally, that have stayed with me the most: Noughts and Crosses, Gone with the Wind, The Lottery, Gone Girl. That harsh slap of macabre that leaves its sting long after I close the book.

That is not to say every book needs to end in tragedy. If that were the case, we would all be weeping in the streets. The integral part of this approach is to ensure that there are enough trials and tribulations for the characters along the way for the readers’ emotions to linger beyond the last page. So the key to making a story stay with readers is simple: first you have to make them fall in love – then you must break their hearts. Successful happy endings work because the reader has fallen for the characters and had their heart broken along the way, delivering the same emotional impact, even if the characters get their deserved closure at the end of the book. Just like real life, the characters will have faced life-changing circumstances that have forced them to grow; broken them, before fixing them again, but forever changed from who they were at the start of their journey. It’s that pain that makes the reader empathise, and most importantly, creates that special lasting impression, and has them recommending the book to everyone they know. But sometimes, like with my personal Hero book, Noughts and Crosses, it pays to skip the Happy Ever After entirely… You make the rules.

When I think of readers reacting to books in this way, I often think of my former spouse’s mother, who would launch a book across the room with a scream every time she reached a pivotal, emotional twist in a tale. When a book ended with the aforementioned pretty pink bow, she could remember liking the story, but didn’t remember what it was actually about. When she was shocked, heartbroken, angry, or relieved to reach a happy ending after a character’s many trials and tribulations, she could tell me everything that happened, because her memory of it was attached to the emotion she felt along the way. She didn’t just recollect the book as she spoke to me – she was experiencing the emotions all over again.

Every time I write a new book, I write with this emotional impact in mind, constantly thinking of how it will make my readers feel, deep in their bones. How I can deliver that slap of emotion? The lingering sting? How can I make the reader feel just like I did aged twelve, left reeling as I reached the last page of Noughts and Crosses?

If your characters are going to have a Happy Ever After, make them work for it, or dare to go further, and leave it in tragedy (it worked for Shakespeare).

Your readers won’t just thank you, they will never forget your book, or how you made them feel.

Our author tutor Jack Jordan is the global number one bestselling author of Anything for Her (2015), My Girl (2016), A Woman Scorned (2018), Before Her Eyes (2018) and Night by Night an Amazon No.1 bestseller in the UK, Canada, and Australia. His eagerly awaited fifth novel Do No Harm was sold as a six-figure deal in a three-way auction to Simon & Schuster and is set to be the thriller of the summer in 2022 with enthusiastic advance reviews from well-known crime and thriller writers. The idea for Do No Harm came to Jack after undergoing a minor medical procedure where he had to be sedated and trust strangers with his welfare. After the anaesthesia wore off, Jack began scribbling his notes, wondering to himself just how iron-clad a surgeon’s oath is, and what it would take to break it...

Find out more about writing with Jack here and sign up to one of our Book in a Year plans to write your thrilling suspense novel with him. Start today!

September 11, 2021

Fair Play in Fiction.

From the desk of Tash Barsby.

I’m a month into my new role at The Novelry, and what a whirlwind it has been. I’ve been lucky enough to talk with some fantastic writers and read some incredibly promising work, which is what I have always loved the most about my job – that close relationship between author and editor is truly such a special one, and having the chance to help shape ideas and drafts when they are so fresh is unbelievably exciting. But something I’m also really keen to bring to the writers at The Novelry is the opportunity to demystify the publishing process – particularly the parts that may be less obvious or that wouldn’t even have crossed your mind to consider (because they certainly hadn’t to me until I started working in the industry!)

So, in this, my first blog for The Novelry, I'm going to tackle the harder questions which often concern writers the most – what's fair in fiction?

There’s a disclaimer on the copyright page of every work of fiction that will say something along the lines of:

‘This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.’

So does this mean you aren’t legally covered if you purposefully write a real-life character into your story?

Depending on your genre and setting, including factual elements and real-life references can help to bring a valuable sense of authenticity and background colour to your novel. A teenage character in a novel set in the years between 2010 and 2020 would, undoubtedly, be a hardcore One Direction fan; references to Fred and Rose West wouldn’t be out of place in a crime novel about serial killing duos; it would probably feel as if something was missing if the Eiffel Tower was never mentioned in a novel set in Paris. Your characters are allowed to have opinions on politics, on religion, on the latest celebrity drama – these are useful factors when it comes to creating and contextualising memorable, relatable, three-dimensional characters. However, if your story turns on references to real-life news stories or includes material that may have a genuine impact on someone or something’s reputation, then you need to be wary of saying anything that could be considered damaging.

For example: if you were writing a novel about sex abuse in the Catholic church and centred it around a real church, with a real priest committing abuse, that would most likely raise some eyebrows. In that case, I would highly recommend creating a fake church or fake priest through which to explore the real-world issue. If you have a scene where your character finds themselves sat next to Russell Crowe on a plane and gets snapped at for asking for an autograph, his lawyers are highly unlikely to come after you; if the crux of your story is that Russell Crowe is running a worldwide drug smuggling ring, they might have something to say about that.

The same thinking applies if you are basing a character on a real-life person – if they are easily identifiable regardless of any changes you have made to ‘hide’ them, and their portrayal in your novel could be argued to cause them reputational harm, then this is also something to consider. Let’s say your novel is set in the 90s and the main characters are a pop band of five female singers, one of whom wears a Union Jack dress, who are called the Herb Girls and have a hit song called ‘Herb Up Your Life’. It would be very obvious to anyone reading that these characters were actually the Spice Girls, and so any scandalous material written about your ‘characters’ could be considered damaging. Even if it were something that had been previously reported in the tabloids (e.g. an affair, allegations of alcoholism), this doesn’t mean you can take it as fact when representing them in fiction.

If you’re ever unsure, play it safe.

Flag any queries or concerns you have to us at The Novelry, or later as you approach publication, your agent or editor, who will escalate it to their legal team, or seek legal advice before publishing. The final decision is yours, but please listen to the advice you’re given: if a change is suggested, I would strongly recommend you make it – unless you have a very, very good reason not to and are prepared to defend your case (more likely in the court of social media than in a court of law, if we’re honest, but never say never).

So when else might you need a more experienced pair of eyes to look over your manuscript? Authors love to put quotations in their work, whether it’s within the text itself or as part of an epigraph – for example, song lyrics, poem verses, film quotes, newspaper articles.

If a quotation fits the themes of your novel, or would enhance a particular scene, and it feels important to you to include it then by all means do – but just be aware that, depending on the length and content of the quote, you may need to seek official permission (and sometimes pay) for the pleasure of doing so. As a general rule, all quotes should be attributed somewhere in the text, whether that’s on the copyright page, in the acknowledgements or in a sources section. If a quotation is under a certain length (roughly under two lines) then it will usually be considered ‘fair dealing’ – unless it’s part of a particularly famous line or the quote you’re using makes up a substantial part of the original, in which case you would likely need to clear official permission from the copyright holder. Always make a note of where you have sourced a quotation from – it will save a lot of time and effort in the long run. Seeking permissions for publication can be a long process, so the earlier it’s started the better. Generally, text permissions are considered the writer’s responsibility, as it’s your choice to include the quotation, so it is down to you to seek and where necessary pay for permission – and you’d be surprised at how pricey they can be.

Those are some examples of how to deal with the real world within your fictional world from a legal perspective (with the caveat that I am not and never have been a lawyer, so this is purely based on my understanding from past experience). But what about from a moral perspective?

A topic that has become increasingly prevalent in the publishing world recently – and for very good reason – is that of own voices, and who has the right to tell a particular story. Cultural appropriation has become a very important matter.

We’re all familiar with the advice to ‘write what you know’ – but is that always feasible? Fiction, by its very definition, is not real – to some extent, all fiction writers need to draw on experiences outside of their own lives for their stories. But when that experience is too far removed from a writer’s own experience, that’s when a sensitivity reader is called for.

A sensitivity reader is someone with direct lived experience who is hired (always, always, always pay your sensitivity reader. Always.) to assess a manuscript with a particular issue of representation in mind.

Whilst of course no one can claim to speak for an entire demographic, the likelihood is that no matter how much research you have done, inaccuracies or stereotypes will undoubtedly creep through the gaps through unconscious bias, and so having that outside perspective is vital to ensure fair and accurate representation.

Undoubtedly, we need more diversity in fiction, both in terms of the voices being heard and given a platform and in terms of representation on the page, and sensitivity readers do hugely important work in bridging that gap and opening up a vital conversation between members of a marginalized community and those outside it.

A sensitivity reader will offer thoughts and advice, guidance on language and terminology, to enable you to improve how a character is representing a particular experience and help you to avoid perpetuating stereotypes – they are not there to do all the research and emotional labour for you. The initial work must come from you – if you haven’t done the necessary research into the realities of someone’s lived experience, you shouldn’t be writing about it.

Perhaps because sensitivity reads are still a fairly new undertaking for many publishers, there isn’t a ‘set’ process – but generally, it would seem to make sense for you to work with your editor on the story, and then have a sensitivity read done before it goes to copy-edit. If you believe something you’re writing would benefit from a sensitivity read, flag it to your editor early or secure a read before submitting it to an agent or editor. The pool of sensitivity readers is, thankfully, growing and it’s hugely important to find the right reader to assess your work.

As with a lawyer’s advice on the portrayal of real-life people or places, the decision whether to take in the sensitivity reader’s changes is ultimately the author’s call – but please consider their advice carefully and really try to understand where they are coming from with their comments. Sensitivity readers aren’t there to rip your characterisation or entire novel to shreds – they are on your side, and their aim is to help your manuscript be the very best it can be. What may seem like an unnecessary change to you could be extremely important and meaningful to someone else, and make all the difference to how they respond to your story – and isn’t having your novel speak to a reader what it’s all about?

Happy writing,

Tash

Further reading for taking care when representing the lived experiences of others can be found here as a starting point. (To compile this list, we have asked The Novelry team and guest authors to make their suggestions. With special thanks to Rachel Edwards and Louise Hare.)

Writing the Other. (A website of resources.)

Don't Dip Your Pen Into Someone Else's Blood by Kit de Waal.

Superior: The Return of Race Science by Angela Saini.

Me & White Supremacy by Layla F Saad.

The Good Immigrant by Nikesh Shukla.

What White People Can Do Next by Emma Dabiri

How to Unlearn Everything. When it comes to writing the “other,” what questions are we not asking? Alexander Chee. (Asks Why do you want to write from this character’s point of view? Do you read writers from this community currently? Why do you want to tell this story?

So when I meet with those beginner students to discuss their first stories, I ask them to think of stories only they can write. Stories they know but have never read anywhere. Stories they always tell but never write down. That’s what this question is really about. Or could be. If the questioner asked it of themselves more often than they asked other people. Alexander Chee.

Cultural Appropriation for the Worried Writer: some practical advice by Jeannette Ng.

But if you’re looking to play saviour with your words, it is unlikely that you will do the marginalised people you are trying to save justice. Jeanette Ng.

Writing the Other: A Practical Approach by Nisi Shawl, and Cynthia Ward.

5 Common Black Stereotypes in Film and TV.

And a brilliant Instagram post:

10 Steps to Non-Optical Allyship by Mireille Harper. ("Avoid sharing content which is traumatic to black people.")

September 4, 2021

Phoebe Morgan

From the Desk of Phoebe Morgan.

As I write this, I’m surrounded by boxes of books. I have FAR too many books – they are not easy to move, they are cumbersome to carry, they split the cardboard at the seams and they conjure up a wince on the face of my partner as he carries them diligently into our new house. But they are the most precious thing to me in the world, and as I sit and write, I can almost feel them scattered around me, alive and kicking, nestling into their new home.

Where would we be without stories? I have often asked myself this, and perhaps never more so than in times of distress. Visiting my grandmother in hospital this week, I brought her a notepad and pen so that she could attempt to make sense of the changing ward around her. Her eyesight is no longer very good so the writing was hard to make out, but that didn’t matter – what mattered was that she was able to escape into her imagination, as so many of us have done during this long, hard eighteen months of the COVID pandemic. Without stories, that would not be possible. Stories give us freedom. They give us respite. They are, without doubt, extremely important.

As a writer and an editor, I am privileged enough to spend my life surrounded by stories. My head is consumed by the narratives of others, so much so that I sometimes wonder how present I ever really am in the real world, with all these alternative realities jostling for space in my brain. I began writing myself back in 2014 aged twenty-four, whilst working several other jobs – I was a journalist on a local newspaper, I was a babysitter, I was a barmaid. And then secretly, in the evenings, I was a writer of fiction.

Writing for me was a secret for quite a long time. I remember a friend asking me about my having a literary agent (she had seen it online somewhere) and feeling so incredibly embarrassed and exposed – my secret was out! It could come back to bite me.

It didn’t – I was lucky. Seven years later, I am the author of four novels, and am currently wrangling with the edits for a fifth, and my writing is very much a public part of who I am in a professional sense. Yet still, on a personal level, I struggle with the idea of myself as a writer. Perhaps we all do – imposter syndrome is real, and it can be hard. I never introduce myself as a writer at parties, I never bring it up unless someone asks. Why is that, I wonder? I know stories are important, I know how much they mean to me and so many others, and so why do I feel afraid to acknowledge my own?

I know I’m not alone in feeling like this, many others feel similar. Why is that? Is it because we worry about bad reviews or ridicule? For me, I don’t think it’s necessarily that, being quite hardened to negative reviews due to my day job (I know everybody gets them sometimes!) Is it because we want writing to be a private space – is something lost in the telling? For me, even after four books, I don’t identify as a writer, perhaps because I have another job too, but I know there was a certain legitimacy that came once my books were actually published. I felt as though a goal had been achieved, and I don’t think I will ever feel the same desperation I felt at the very start of my writing career before I had a deal on the table. Through my writing, I have formed a supportive group of writerly friends, and while they sometimes discuss craft, I rarely join in – for me the craft is something I have to do alone. I think this is because with a full-time job my time is quite limited in terms of writing, so I worry that if I spend too much time second-guessing, the words will never come.

For me, writing is something I always do alone, without fanfare, sat at a desk or a table or in bed. Writing during the pandemic was one of the only things that got me through the winter lockdown – whole weekends were lost to book 5, and it gave my days a wonderful sense of structure and of purpose. Writing is the only time where hours seem to fly by on their own – I don’t even notice the time passing, which I don’t think happens at any other point of my day to day life. Writing lets us time travel, then. It swallows up time, it creates time if we need. It is, truly, a thing of pure magic.

In my day job, I’m often asked about how to write novels. There is no perfect way, of course, but my own strategy is to let the words take me where they will – not to worry too much about where they are headed (that, of course, comes later), but to trust in the tap, tap, tap of my fingers on the keyboard and allow the story to unfold as it wants to in my head. I have never plotted one of my novels out in its entirety – my mind just doesn’t work that way. Often, I will begin with a setting – in The Babysitter, my third book, we open in a villa in France, and in my latest, The Wild Girls, we’re in a luxury lodge in Botswana. Book two, The Girl Next Door, places the reader in a conservative little house with bay windows in Essex, and book one, The Doll House, starts with a small London flat in the tangle of streets between Finsbury Park and Crouch End. For me, places are the starting point, and the characters begin to populate them all on their own.

As an editor, too, I know that all authors have different approaches to the writing process, and this is mine alone. I find it fascinating how differently we all work, and really, it doesn’t matter how we get to the end of our stories – what matters is that we do work, we do write, we craft those stories that are bound into novels that then fill the boxes and the bookshelves in home after home after home, up and down the country, all across the globe.

Books are always worth the heavy lifting.

Back to school at The Novelry with our two new author tutors, Jack Jordan and Tasha Suri. Ready to help you write your novel this autumn. Get a first draft done by Christmas.

Sign up and start today with one of our wonderful creative writing courses from just £99 or $149. Treat yourself to some quiet time for you!

August 28, 2021

What Do Editors Really Do?

When I tell someone I’m a book editor, I can sometimes see their imagination bubble pop up: me, sitting alone in a dusty reading nook, wearing thick spectacles and a black polo neck, using angry, blood-red ink to scratch out split infinitives and misplaced semicolons.

Unfortunately, this is not quite true – not least because I don’t wear glasses.

Writers (understandably) spend a lot of time worrying about whether an editor will publish their book – but they don’t always know what that will entail at the other end. Like many creative industries, publishing can be impenetrable and opaque from the outside (and often from the inside, to be honest). I hope that giving you more information about what editors do will enlighten and empower you in the process of getting your book published – as well as humanise us editors a bit!

So what does an editor do?

One of the most common things for editors to say when asked is that it’s an incredibly varied job. ‘Every day is different.’ And, as with most careers, there is a huge amount of variety in what the title ‘editor’ means, influenced by job title and experience, the attitude of different companies and teams, the specific requirements of fiction, non-fiction, genres and formats, and of course, the individual editor’s skills.

But broadly, we can divide the role into ‘acquiring’ a book, ‘editing’ a book and ‘publishing’ a book.

Acquiring

To ‘acquire’ a book simply means to buy the rights to publish it. What this means for you, the writer, is that you have just been offered a book deal. (Hooray!) But what this means for the editor is that they will begin the whole process of project managing your book, all the way through from the legal contract to beyond its publication.

Most editors don’t accept unsolicited manuscripts. This means they are only able to read books sent to them through literary agents. Some publishers will have a folder for unsolicited manuscripts (infamously nicknamed the ‘slush pile’) but due to demands on their time and the prioritising of manuscripts from relationships with agencies, they cannot guarantee reading these. This is why an agent is so vital for getting your manuscript into the right editors’ hands. A good agent will have close working relationships across publishing houses, and will know individual editors’ tastes. They might even have teased the editor with news of an upcoming submission they should be excited about…

Let’s play it out. Your agent sends an editor your manuscript, knowing that she’s interested in books like yours. The editor reads it, falls in love with it, and wants to publish it. But she can’t just decide that alone or pluck numbers out of thin air. She will have to go through a gruelling internal process: getting reader reports from other members of staff (both editorial and from across the other teams, like publicity, marketing, and sales); pitching the book in an acquisition meeting; making a case for how it's financially viable for the company; compiling comparison sales figures to estimate a competitive offer, and then making that offer to your agent.

Acquiring great books is how editors build their experience, expertise, relationships, and reputation. An editor knows that when she’s making an offer on your book, she’s committing to champion your book through thick and thin, and to work together closely for a very long time (sometimes for your whole career). It’s a collaborative and all-consuming process and will be made because someone really, really believes in your potential. Editors will often have a strict maximum of books that they are allowed to publish on a list per year and will be thinking about many factors including market forces, their other workloads, and target budgets. She may well be bidding on your book against colleagues and friends, and staking her reputation on the reception of your novel. Offers are not made lightly.

The takeaway? The submission process is a huge moment for the aspiring authors, but it’s an emotional rollercoaster for the editor too.

Editing

Hooray! You’ve accepted a book deal, you’ve signed the contract and your book is going to be published.

Your editor clearly thinks you’ve written a brilliant novel – but it could be even better.

This is where the red pen comes in.

At most trade publishers, your Editor will work with you on structural edits and line edits, but they will not be your copy editor or proofreader. But Lily, I hear you cry, what on earth is the difference between these seemingly synonymous terms?

Well.

Structural edits = how to improve the big picture of your story. This will be a collaborative process with your editor, discussing any major or foundational changes to be made. They will be different for every book, obviously, but will often be questions of whether they fulfil its promise for readers of the genre. Is the opening the most intriguing it can be? Is the ending satisfying? Are there any missing or extraneous scenes? Are there plot holes to fix? Are we interested in each of the characters? And so on.

Line edits = sentence-by-sentence improvements. Once the structure is all in place, the editor will zoom in. Are there words you use too much? Are there metaphors that don’t quite work? Jokes that don’t land? Your editor will make expert suggestions to polish every page until you’re both happy it’s the best it can be.

Copy-edits = fact-checking and sense checking. Now we’re at the nitty-gritty. And by the way, fact-checking is not just for non-fiction: your copy editor should ensure that real things you’ve referenced are accurate (e.g. if you have said your characters fly from the UK to the US in twenty minutes, they’ll flag that humans haven’t invented commercial flights that fast yet). They will also check for internal consistency (e.g. have you accidentally spelled the name of a magic spell differently). Copy editors will also be formatting your typed manuscript with instructions for the typesetter.

Proofreading = correcting typos. Checking the typeset manuscript against the copy-editor’s markings, to ensure that in the final printed text, there aren’t any ugly line breaks or errors. Proofreaders make sure that all of your is are dotted and ts are crossed, and that there aren’t any accidentally the other way round.

Copy-editing and proofreading are highly specialised and time-consuming processes that are usually performed by freelance experts or separate in-house teams. Any suggestions will then go back to the editor, who will share them with you, the author, to approve.

Now your book is ready to be read!

Publishing

This is the part of the role which people tend to know the least about, but which actually takes up the majority of the editor’s time.

In trade publishers, editors are essentially project managers. They are the first point of contact for your book, fielding internal and external questions. They must be aware of all the comings and goings, give the relevant information to other teams, facilitate meetings, ensure that deadlines are met, and problem solve if things go awry. Editors must therefore not only be fantastic story-tweakers, but also excellent communicators.

As the expert and head cheerleader for your book, the editor is present at all the major meetings involving your book. They are there not only as a fact source but also a creative collaborator: briefing designers on directions for your book’s cover design; hearing campaign plans from the publicity and marketing teams; liaising with sales teams to ensure that your book is available with retailers; all the way to discussing the production of your book – would it be better blue endpapers or purple, embossing or sparkly foils? Your editor is there to weave all these strands together towards the deadline of your publication day when your book is officially launched into the world. And beyond!

Being an editor at The Novelry

The Novelry’s editorial team is made up of people with years of experience acquiring, editing, and publishing books at ‘Big Five’ Publishers. At The Novelry, our responsibilities focus on the ‘editing’ part – the hands-on creative feedback, where we collaborate with you to help make your manuscript the best version of itself. This is many editors’ favourite part of the job (including mine!) and it’s an honour to be an early reader of your work. The feeling of discovering a shiny new story never gets old.

But we editors also bring our experience of the ‘acquiring’ and ‘publishing’ processes to help you with pitching your book. Agents used to submit novels to us: now we’re helping to submit your novels to agents! And because we’ve been on the other side, we know exactly what editors are looking for.

When you sign up for one of our Book in a Year plans at The Novelry you'll enjoy our combined author and editor expertise to take your twinkling of an idea all the way through to the real deal.

I hope you’ve found this useful. If you have more questions, you might like to come along to our live Q&A with the editorial team (featuring Lizzy Goudsmit Kay, Tash Barsby and me) on Tuesday 31st August at 6 pm. All members are welcome. We look forward to seeing you there! I’ll have to dust off my black polo neck…

If you'd like to find out more about how we can help you with your novel, take a look at our editorial services page here.

Back to School at The Novelry!

There's still time to get a first draft done this year with our Ninety-Day novel course! Hoorah! After a year of home-schooling, seeing our beloved darlings off to school will come as a relief to many. Take an hour a day for yourself and start a meaningful relationship with your writing.

Join us! Simple, honest, affordable and fun.

Have you seen our new tutors at The Novelry? The energetic Jack Jordan and the inspiring Tasha Suri! When you join us at the Novelry you get to choose just the right author mentor for you and your writing.

Happy writing!

August 21, 2021

Louise Hare

From the Desk of Louise Hare.

Last week I did my first in-person event of the year. It was a low-key affair, part of the brilliant Essex Book Festival, held at Grays Library. As is usual, towards the end of the event there were audience questions. There was one that resonated with me more than any other. A question that I’ve been asked before, and that I think is an interesting one to answer:

Will you always want to write Black characters?

The simple answer is yes. Why wouldn’t I? After all, would a white writer ever be asked why they always wrote white characters? Unlikely. The reason for that is we are conditioned to expect white characters as default. If you pick up a book and begin to read about a middle-class woman, married with two children, working as a solicitor, how do you first picture her before you’ve been given any details about what she looks like? When I’ve been along to book clubs this year it’s often come up: I wasn’t sure at first which of your characters were Black and which were white. Other Black authors I’ve spoken to have experienced the same. We’re not used to reading about Black characters outside of stereotypical scenarios.

Five or six years ago I came back to writing for the first time since I left school. After stewing in research for the better part of a year (a rookie error in writing historical fiction) I decided that a writing course would give me the discipline to get my first draft done. Another Black writer in the group expressed admiration for my bravery in writing a Black middle-class family in Victorian London. She had decided to make her protagonist a white woman. Do books with Black main characters get published? A genuine concern at the time, one I also shared. So why did I feel so strongly that I wanted to persevere, even as my fellow students were sharing their doubts that a family like the one in my novel could have existed in nineteenth-century England, despite the fact that I had based them on a real family?

I finished writing that novel but it still sits in a drawer somewhere. I could never get the plot quite right, though I fell in love with the cast of characters. A couple of years later, I enrolled on a Creative Writing Masters at Birkbeck, University of London. In the first term, my diverse classmates read my short story about a young Jamaican man fresh off the Empire Windrush and already having second thoughts about leaving home and urged me to continue Lawrie’s story. They wanted to know what happened next and, crucially, so did I.

This Lovely City has a wide cast of characters, both Black and white, but its heart is the love story between Lawrie and Evie, both Black. In Lawrie I wanted to explore how it was to arrive in London and suddenly feel out of place, not just because he’s never been in such a big city before, but because he sticks out for the first time in his life. In Evie I was able to share my own experiences of having been a minority since birth. At times the writing felt cathartic, though some scenes were difficult, particularly those featuring DS Rathbone, the policeman who plagues both Lawrie and Evie throughout the book. I felt a connection to my characters that I don’t think I would have had if I hadn’t shared a lot of their experiences. I don’t think that a white author would have been able to write This Lovely City. Which isn’t to say that I am against writers exploring outside of what they know, I just ask that they do so with care and attention, avoiding stereotypes.

When This Lovely City was published last year I wrote an article for i, specifically focused on why we should celebrate Black British writing more. The UK publishing industry is risk-averse. Understandable, to an extent. Publishing is a business like any other, we just kid ourselves that because we hold literature in such high regard that it is less prone to the pitfalls of other creative industries. But just the film industry turns to safe content such as sequels, book adaptations and superheroes, preferring to push money into known quantities, there has long been held the mistaken notion that books with Black protagonists don’t sell.

As a British author, when your manuscript lands in an editor’s email inbox they have to calculate how many copies of your book might be sold. As a debut author with no track record, with a book written from a perspective that is very likely different to that editor (remembering how few people of colour work in publishing), how much of a risk are they willing to take? On the other hand, a US-based author of colour, riding high in the NYT Bestseller lists is far more attractive.

Things are changing in the industry. Two new imprints have come along to shake things up: Dialogue Books (Hachette) in 2017 and #Merky Books (PRH), a collaboration with Stormzy, in 2019, both aiming to offer homes to voices and stories that are currently underrepresented in literature.

In 2020 Candice Carty-Williams (book of the year) and Bernardine Evaristo (author of the year) became the first Black authors to win the top awards at the British Book awards. Queenie has been a huge bestseller selling over 150,000 copies as well as being critically acclaimed. Girl, Woman, Other became a hit after jointly winning the 2019 Booker Prize. Evaristo is now a global literary star, a mere twenty-five years after her debut novel was published. And yet even Girl, Woman, Other was largely ignored, stocked in minimal numbers in bookshops until it won the Booker.

So far this year we’ve seen high profile publications for Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water and Natasha Brown’s Assembly. As a huge fan of crime fiction, I’m glad to see that genre opening up more to Black writers. Nadine Matheson’s The Jigsaw Man is the first in a new series set in Deptford, southeast London, featuring Inspector Anjelica Henley. It’s a pleasant novelty to sit down with a book and spend some quality time with characters who look like me, go through similar trials and tribulations, and then go out and solve murders!

There is a wave of change within the industry currently that I have been lucky to catch hold of. My debut was pre-empted after being on submission for less than a week. The dream scenario in other words. Would that have happened if not for the Windrush scandal raising awareness of the racism that still exists in UK society? Would editors have been clamouring to publish Lawrie’s story if they hadn’t been reading about men and women who were descended from people just like him and Evie? Probably not. Just as Lawrie is in the wrong place at the wrong time, I was in the right place with the right book at the right time. You can only write the book that you want to write (trust me, I’ve tried to write cynically and for market, and it just doesn’t work out) and I’m grateful that people want to read my work.

My new challenge is to find success with my next book, Miss Aldridge Regrets, a more straightforward historical murder mystery set on-board the Queen Mary in 1936 as she sails towards New York. It’s a different style of novel, a more traditional style crime story (I was aiming for Agatha Christie meets Patricia Highsmith), though I again have a woman of colour as my protagonist. Lena Aldridge is a mixed-race woman who sometimes passes as white. Her character is absolutely inspired by the racism aimed at Meghan Markle and its denial, the idea being that if she sort of looks white then how can it be racist. It was a topic that interested me at the time, and I wanted to explore it through fiction. I also found it incredibly fun to create some horrid characters and bide my time before killing them off!

I quote Toni Morrison often: If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.

This is at the heart of why I write Black characters. Because for so long I struggled to find books with characters who looked like me. I love historical fiction but I don’t just want to read about Black servants, slaves and whores, standing on the sidelines as they suffer through terrible, dreary, often short lives at the expense of a white protagonist who gets to be the hero or the villain. I will always write about racism because it’s part of my daily life, but my characters will have friends and go to parties and have fun and fall in love, the same as anyone else. Just like the white protagonists I’ve been reading for forty years. I want to fill in the gap in the bookshelf that has been there for too long. There are so many stories that I want to read, that haven’t been written, that I’m going to be busy for quite a while!

Louise Hare has an MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London. OThe capital is the inspiration for This Lovely City, which began life after a trip into the deep level shelter below Clapham Common.

Louise will be our guest at The Novelry for a live Q&A session with members on September 20th.

This Lovely City

The drinks are flowing. The jazz is swinging.

But for the city’s newest arrivals, the party can’t last.

With the Blitz over and London reeling from war, jazz musician Lawrie Matthews has answered England’s call for help. Fresh off the Empire Windrush, he’s taken a tiny room in south London lodgings, and has fallen in love with the girl next door. Touring Soho’s music halls by night, pacing the streets as a postman by day, Lawrie has poured his heart into his new home – and it’s alive with possibility.

Until, one morning, he makes a terrible discovery.

As the local community rallies, fingers of blame are pointed at those who had recently been welcomed with open arms. And, before long, the newest arrivals becomes the prime suspects in a tragedy which threatens to tear the city apart.

August 14, 2021

Motivation!

From the Desk of Emylia Hall.

The writer Thomas Mann said, ‘A writer is somebody for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’

I love the recognition of process and perfectionism in Mann’s words – not the crippling kind of perfectionism, mind, but the sort that makes us strive to be better. He’s unapologetically playing to the insider – in the style of Louis Armstrong’s line ‘If you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know’. Each and every writer at work knows how increasingly difficult it seems to get.

So, what do we do then, when we hit the hard bits? Well, understanding that it’s tough for everyone – whether you’re writing for the first time, or you’re a seasoned novelist – certainly helps. And, so too, does giving thought to the psychology behind some of our personal approaches to the process; while we might not be able to control the publishing destiny of our work, we can be in command of our own mindset as we go about it. We can give ourselves the best chance of writing the best book. A few weeks ago Polly Ho-Yen wrote brilliantly on the topic of Imposter Syndrome, and how important it is to be kind to one’s self through the process. Here I’m looking at self-motivation, and how honesty and self-knowledge can help you bring your A-game to the page.

To write a novel, to see it all the way through, is to inhabit multiple selves – and to be true to each one. We are at once the wild and free author of the first draft, permitting ourselves to dream, to make a righteous mess and enjoy the process of creation. We’re the ‘blue-collar worker’ getting the job done, ‘laying pipe,’ as Stephen King put it. We’re the desk jockey, planning our time and executing our plans with strategic control. We’re zealous enough to believe in our own fabrications, but we’re humble enough to see where we might be getting it wrong. We know that writing is an act of faith – we’ve got to believe, to dream – but we also know that if we have publishing ambitions for our work, there are aspects of reality that bear consideration.

Writing, like most halfway interesting things, is full of contradiction. Our individuality is our superpower – our ‘voice’ reflects our sensibility and our unique experience – but one of the most valuable skills we can learn as writers is the ability to appraise our work with cool detachment: to forget that we wrote it. And while objectivity is a virtue in editing, it is subjectivity that will keep us sufficiently in love with an idea that we’ll pursue it through thick and thin. So how do we make ourselves flexible yet robust? Sensitive but steely? Subjective but objective? Humble but bold? Precise yet wild?

I think we realise, from the off, that our approach to writing is, perhaps, as important as the writing itself. I’ve mentioned Zadie Smith’s brilliant essay Literature’s Legacy of Honourable Failure here before, and specifically the lines:

‘Writers know that between the platonic ideal of the novel and the actual novel there is always the pesky self - vain, deluded, myopic, cowardly, compromised. That's why writing is the craft that defies craftsmanship: craftsmanship alone will not make a novel great.’

It is the ‘pesky self’ that can get in the way of us writing even a rotten first draft – let alone a ‘great novel.’ So, it’s self-awareness that is key: being honest with our own pesky selves. Here, it’s important that we don’t write ourselves off before we get started: we all know the power that that self-sabotaging inner voice can wield; how it can assume a persuasive, convincing tone and, as Elizabeth Gilbert puts it in Big Magic, ‘induce complete panic whenever I’m about to do anything interesting.’

For instance, if you think you’ve had trouble finding motivation for writing in the past, ask yourself what that belief is based on – and consider the factors. Know that none of us is defined by the commitment we’ve brought to projects previously. For just as all stories are fundamentally about change, so too are our writing journeys.

In psychologist Tasha Eurich’s TED talk on self-awareness she tells us that introspection can be productive, but only if we go about it in the right way. In Eurich’s study, composed of thousands of qualitative and quantitative interviews, she asserts that 95% of people claim to be self-aware – but that only 10-15% actually are. In her words, ‘on a good day, 80% of people are lying to themselves about lying to themselves.’ Her study discovered only a small quantity of truly self-aware people (fifty self-aware ‘unicorns’). From looking at the behaviour of these ‘unicorns’ Eurich concludes that the key to healthy and happiness-inducing introspection is not to ask ‘why’ but to ask ‘what.’ ‘Why’ is retrospective and can lead to false narratives, whereas ‘what’ is forward-looking, and it’s proactive.

So, let’s not ask ‘why am I not a better writer?’ or ‘why am I struggling to find time to work on my book?’ or ‘why has my manuscript been rejected?’

Instead, ask ‘what can I do to become a better writer?’ ‘What can I do to make sure I get some words down on paper every day?’ ‘What’s the story I really really want to tell?’

It’s about taking responsibility for every part of the process of creation. My writing diary is invaluable to me here. I turn to it whenever I feel the need, and as a result, the entries aren’t all that regular; sometimes I’ll go months without noting anything in it, followed by a fast and soul-searching flurry; I only ever write about my writing in it (though occasionally, if life events affect the writing space, then I explore them too). It’s a space for reflection and processing and stating intent. I keep a writing diary in order to hold myself to account – and, sometimes, just as a place to feel held. I wouldn’t be without it.

A consistent theme in my writing diary is the value of momentum. At The Novelry, our novel course is based around the idea of writing for one hour a day during the first draft stage – no more, no less. Setting the limit of that one little hour – that infinite hour, where you can travel continents and hurtle through time – sure concentrates the mind.

But what if it doesn’t? What if you use our tools and you still can’t settle into your writing for that hour?

Well, first look at when you’re writing. Are you giving yourself the best chance to focus? If it works for you, we advocate setting your alarm and getting up with the larks – even if, ordinarily, you’re no kind of an early bird. The joy of this is that first thing in the morning can be, for many of us, a quiet, private space. The phone isn’t pinging. The day, with whatever it decides to bring, has yet to get its clutches into us. I’ve never consistently written in the early mornings before, but I did this last winter. At 6.10 am I’d creep downstairs (the slightest creak of a board will wake my seven-year-old) and make coffee and get myself two chocolate biscuits. I’d pull up a webcam of a beach in Cornwall (the setting for my new book) and allow myself a look at the still-dark water – then I’d write my way towards sunrise. I’d allow myself the occasional glance at the webcam, watching the dawn ebb in, and I’d have some non-invasive but atmospheric music playing on my headphones, Alt-J or Portishead – but these weren’t distractions, they helped set the mood. And honestly? It was the smoothest first draft process I’ve ever had. A big part of this was that I always knew, more or less, what I was going to work on in these morning sessions. I made sure I had it figured, or loosely figured at least before I went to sleep the night before. On the few occasions that I hadn’t worked it out, I’d sit staring at my laptop, joylessly crunching biscuits and feeling the already-fragile energy drain out of me – and that wasn’t a feeling I cared to make a habit of; what a waste it was, to show up in body but not in mind. And don’t get me wrong, I didn’t bounce out of bed on any of these mornings, but I did come to be obedient to the routine that I’d made for myself. Muscle memory did its thing. Because of my young son, and the ‘alternate ‘lie-ins’ deal I have with my husband, I only got to write in the early mornings every other day. So, on the intervening days, I wrote at 9 pm instead. But I could never quite replicate the purity of the dawn call feeling; I was too tired by that point, and I wanted to be curled up in bed reading someone else’s book, not trying to write my own. Maybe you’re reading this thinking, ‘well, I’m a night owl.’ Or perhaps your home/work set-up doesn’t permit early starts with any kind of regularity. It’s about finding the time of day that works for you. The most important thing is that you’re able to shake off distractions and gift yourself that golden hour. Finding a cocoon-like space that feels private and quiet and uninterruptable gives most of us the best chance to focus.

Ah, focus. I went to TED again, this time to a neuroscientist called Mark Tigchekaar, talking on the subject. Tigchekaar reckons that when we're speaking, reading or writing, we're typically only using one-fifth of our brain capacity. As human beings, we crave interruption – and that craving disrupts our attention, and stops us from really diving deep. Every minor interruption – be it the ping of an email or the quick check of a website – sucks energy from our brain and diminishes the attention that we have for the task at hand. The average person loses, apparently, two hours every day in this way. Two hours! But... what if we know this already? And what if we still allow ourselves to get distracted? Well, writing is hard and can feel static, and we're pulling words from nothing, and amidst all that nothing there are a lot of somethings looking to trip us up, or snare us, or lead us down another path altogether ...

Maybe it's a case of taming our wandering minds – and turning them into wondering minds instead. Getting in the right headspace for writing is one of the most beneficial things we can do, to sit down at the page feeling calm, confident, and focused. Neuroscientist Amishi Jha reckons 50% of our waking thoughts are wandering. Which, again, takes from our attention big time. And while some of these thoughts might be a pleasant kind of daydreaming – a useful, productive, enriching type of pondering – a quantity of these will almost certainly be stressing, catastrophizing, regretting (you know, all the good stuff …). Jha is a mindfulness practitioner, who believes that we’re all capable of improving our attention and curtailing these wandering thoughts. Some of you may already have your daily practices, but perhaps you haven’t yet connected them to your writing process. Jha advocates a daily work-out, where we simply pay attention to the bodily sensation of breathing. Sit with eyes lowered or closed. Breathe in, breathe out. When a thought comes to mind, note the occurrence of it, then redirect attention back to breathing. Do it for five mins, 10, 15 - whatever we can manage. But do it regularly.

In a similar vein, there’s a wonderful lesson in the novel course at The Novelry called Moods, where founder Louise Dean offers advice on bringing compassion to the page: not just for the characters in our novels, but for ourselves too. From the lesson:

‘Ronnie Laing, the great psychotherapist, took an unusual approach to people with mental health problems in the late 1960s. He simply sat down with them. If they were sitting on a floor of a clinic with their head in their hands, he sat next to them. He believed fellowship did a power of good.’ Louise goes on to say, ‘You’re not writing any old book, you’re writing your book so you need all of you. The original true you. So just abide with yourself kindly, as Ronnie Laing would want you to.’

For me, any questions of self-motivation, application, and accountability, all come back to what we're writing - and why we're writing it; how deeply invested we are in our story, and how much we care about our characters. A strong connection to a writing project is, I think, what best focuses the wandering mind. And, really, there’s no excuse for a weak link when it comes to this connection because what we write is an active choice. No one’s making us do this, are they? Of the hundreds or thousands of story avenues out there, we’ve each chosen to head down a specific one. Why? Has a particular set of life experiences led us to this point? Or did the idea just come, and there’s something about it that won’t let us go? Does the market seem especially buoyant for a certain sort of genre and we want to take our best shot at commerciality? If you believe in your reasons, then whatever they are, they’re valid. But pausing, taking stock, and interrogating your choices – with as much honesty as possible – will help with your motivation and commitment along the way.

Okay, so ... you're loving your idea, you're focused, you're self-aware ... but sometimes it's still hard going? Well, welcome to writing! Shout out to Thomas Mann. Seeing the novel-writing process as an opportunity to get to know yourself better is, I think, key to embracing its challenges. Keep up the dialogue with yourself as you write. Surround yourself with people who are supportive of your endeavours (The Novelry community ahoy!) – but make yourself your own best cheerleader. And rest assured that, as writers, we’re all in it together.

A few tips, from one work-in-progress self-motivator to another:

Be honest with yourself and your motivations for writing – and manage yourself accordingly.

Write what you want. Write what you find rewarding. Emotional authenticity is everything.

The right idea will drive you. You will feel its energy and momentum.

Care about your work and have confidence and conviction.

Don't let self-doubt screw with you. Hear it, know it for what it is, and carry on regardless. But be self-aware enough to know the difference between self-sabotage and genuine instinct.

Know that writing is a lifelong apprenticeship. The hard yards are rarely easy.

Be humble. Know that sometimes you have to get it wrong to get it right.

Happy writing!

Emylia.

August 7, 2021

Writing a Series

From the Desk of Kate Riordan:

For some of you, the notion of writing a series is enough to bring you out in a cold sweat (I don’t know if I can finish ONE yet!). For others, especially those writing in certain genres, a series might well be a better bet than a stand-alone. Readers of fantasy, as well as children’s and detective fiction, among others, are totally accustomed to investing their time (and money) in a series. And, as a writer, if you can get them hooked on book one, you’ve got an almost guaranteed sale for book two, and so on. In a career with very little security or certainty, the possibility of signing a three or four book deal is pretty alluring. But before you jump in, there is much to consider.

As I see it, there are roughly two different types of series: the sort of epic story which is so complex and sprawling that it requires telling across multiple volumes (think George R. R. Martin’s fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire), and the episodic kind we see more often in detective series, with a more self-contained story in each book featuring and (mainly) told from the perspective of a familiar, returning protagonist (think Lee Child’s Jack Reacher books or Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels). I’m simplifying for now, but bear with me, and I will return to the multiple arcs and complex world-building of the these series which don’t necessarily need to be read in order.