Louise Dean's Blog, page 7

February 5, 2022

Literary Agent Marilia Savvides on Writing a Great First Chapter

Marilia Savvides is a literary agent in the Books Division at 42, one of our partner literary agencies at The Novelry. A graduate of UCL and the Columbia Publishing Course in New York, and a returning member of the faculty at the Columbia Publishing Course at Oxford University, Marilia spent seven years working at Peters Fraser + Dunlop and joined 42 in early 2020. She was a Bookseller Rising Star in 2018.

Here, Marilia shares her thoughts on perfect first lines and how to write a great first chapter of a novel.

From the desk of Marilia Savvides.

“There are all sorts of theories and ideas about what constitutes a good opening line,” he said. “It’s tricky thing, and tough to talk about…To get scientific about it is a little like trying to catch moonbeams in a jar… There’s one thing I’m sure about. An opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know about this.”

Stephen King

As an agent, first and foremost, I’m a reader. Sure, we read more than most, but when you boil it down, the truth is agents and editors are just readers at heart. We love books. And like everyone else, we want to be gripped, engaged, invested, obsessed, scared, puzzled and intrigued by the novels we read. We want to be plucked from our lives and transported someplace new. There is no greater joy than the moment you realise you’ve just picked up a book you’re going to fall in love with. The sheer magic of that connection, the growing of the heart, because you’re so excited about the story you’re about to be told; the sadness you already feel because at some point, it’s going to be over. What a gift.

It’s a cliché but that’s because it’s true.

Human beings are built to tell stories. That’s how we all make sense of the world. We add narrative to our own lives and pull a thread from A to B to C, to stitch a linear story where we are the main character. We read books and watch movies and documentaries and listen to podcasts, because we want to be told stories. Good stories. We want to make sense of the world, we want to be seen, and we want to be entertained.

Your job, as the writer, is to cast a spell on us in that first opening chapter. No matter the genre, no matter whether your novel falls into the publishing buzzword categories of commercial or literary or upmarket or some combination of these, the truth remains the same. First chapters need to grab us by the throat or the heart. What they absolutely shouldn’t do is leave us cold, unless it’s with goosebumps and a chill running up our spine.

First lines

I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.

You’ve been here before.

First lines are certainly not everything. I’ve read hundreds of novels I’ve adored which began in very simple, straightforward ways. Even unmemorable beginnings can work well, and often they can be preferable to overly written beginnings that are trying too hard to showcase someone’s “writing skills” (more on this later). But we would all be lying if we didn’t admit that, once in a while, an author writes an opening line that is so simple and atmospheric and shocking (1984, The Bell Jar, The Secret History) or so concise and perfectly confident in its voice (I Capture the Castle, Moby Dick) that we immediately want to know more about the story, the narrator, the world we’ve just entered. And that’s when you’ve captured your reader from the very start.

Less is more

One of the most common mistakes I come across when reading submissions is stuffing that first chapter with too much information. Over-exposition. Some authors feel the need to showcase as much detail as possible about the characters or the world we’re in, or the plot of the book, in that very first chapter. I get it. There’s a natural instinct to pack in as much as possible, the worry being that agents are reading those first chapters, and you want them to get a sense of where the story is going to go. You want to show them your work. But this isn’t maths, remember. This is magic.

Hold back that panicked voice in your head and allow yourself the freedom to set the scene, the mood, the voice. Reel us in. Too much exposition can kill the drama. Backstory will come later. This is your moment to hook us. We can figure out the other bits later. Trusting your reader to follow you is crucial, but you have to give them a good reason to stick around. Because the worst thing you can do is be boring.

Less really is more

The second most common mistake I see when I’m reading submissions is over writing. Again, authors I think are worried that an agent won’t get to see their beautiful turns of phrase or literary skills in just a handful of pages. They fixate on some of their favourite sentences, the ones they might consider to be profound or especially well-written. The problem is that, often, those beautiful moments have to be sprinkled throughout the book, because that’s where they have the most impact, and because the story must take centre stage. It has to.

And so, if you’re writing from a place of panic, trying to showcase your talent in those first opening scenes with an excessive focus on highlighting your “writing skills” and making that more important than the character or the story, you’re going to lose us. No series of words strung together, however beautiful they might be, will ever be enough to trump or replace the time you are given to grab and hold on to the reader.

Why should we stick around? What story are you going to tell me? Who are we meeting? What’s happening in their lives?

What are the stakes?

Is someone on a flight that’s about to crash? Has a character’s sister just been selected to fight other children to the death in a televised event? Is a woman running away from something or someone we can’t see, deep in the woods? Has someone just been left at the altar? Story begins because something has or is about to change for your main character. It’s often a life interrupted, nudged on to a different path or direction.

Story can only live where a spanner is thrown into whatever that character’s daily life looks like. Always consider what the stakes are.

Can a prologue work?

I personally love a good prologue, especially if it’s a glimpse of what is to come. There’s something about an author dropping us into the middle of the bad thing or the difficult thing, the thing that will come much later, showing you just enough of a peek to grip you, before yanking you away. When done well, and if it’s right for your book, a good prologue can be the answer you’re looking for.

Things to remember:

Don't worry so much

The truth is that first chapters are difficult to write. They feel like they’re extremely important (and they are), but they will often change and morph as you write the book. The more you get to know your novel, your characters, where the tension lies, as you unravel those knots, the more secure you’ll feel about where the story actually begins. Often, what ends up being the first chapter in the published novel was not the first chapter originally.

Go back to basics

When in doubt, go back to the basics, by which I mean pick up a bunch of your favourite books and read their opening chapters. Dissect them, analyse them, look at why they felt so real and believable to you. Ideally, focus on opening chapters in the genre you’re writing in and pick your absolute favourites. Why does that opening work so well? When something does work, it’s more of a feeling than anything we can put into a list or a blog post. So when my authors are stuck, I always tell them to go read something stunning (and I do the same if I’m stuck on a particularly tricky edit). Because the most important piece of advice anyone can give you as a writer is that to be a good writer you have to first and foremost be an excellent reader.

I’ll leave you with this brilliant quote:

“A fine balance between confusion, mystery and illumination… It’s a tightrope walk, that first chapter. You want the reader drawn in by mystery but not eaten by the grue of confusion, and so you illuminate a little bit as you go – a flashlight beam on the wall or along the ground, just enough to keep them walking forward and not impaling themselves on a stalagmite.”

Chuck Wendig

Members of The Novelry can enjoy a live Q&A with Marilia Savvides on Monday, 14th March at 6 pm GMT. Sign up for one of our famous online writing courses which offer personal writer coaching to finish the book you've always wanted to write.

Explore the website to choose the course and payment plan that works for you, or book a free call to meet one of our award-winning author tutors.

January 29, 2022

Katherine Arden on Resilience for Writers

Katherine Arden is the author of the Winternight trilogy that begins with The Bear and the Nightingale, "a wonderfully layered novel of family and the harsh wonders of deep winter magic" (Robin Hobb). Katherine joins us at The Novelry for a special live Q&A with our members on February 21st.

Here, Katherine tells us about the resilience needed to become an author, how she wrote her debut novel in a tent, and how you can surprise yourself with your writing.

From the desk of Katherine Arden.

When I was sixteen, I tried to write a novel. The main character was named Anred. Anred is an anagram of my last name – you do that kind of thing at sixteen. Anred lived underground on a planet that was half ice. To keep warm, her town was built into the base of an active volcano. Unfortunately the volcano was actually a sleeping dragon, and one day it woke up.

It was about as good as you’d expect for sixteen, which is to say that Anred was me, except cooler, and the dragon, shockingly, could shapeshift into a cute boy. Anred fell in love with dragon-volcano-boy, but he had to stay a dragon-volcano to save her village from freezing. Cue angst.

Anyway. I wrote fifty thousand words of this thing, put it away, and went off to college, where I wrote no fiction – didn’t think of writing fiction – for six years. I didn’t think I was going to be a novelist. I didn’t think I could make a living at it, frankly. There were plenty of other things I knew I could do. Writing books is hard.

People often come up and ask, did you know? Have you always known you were a writer? Were your childhood essays pieces of brilliance? Is it your calling?

No, of course not. It’s my job, and I love it. It’s not a mythical process. I also wanted to be an interpreter, a linguist, or a landscape gardener.

I’ve seen people advise aspiring writers that unless your writing is a desperate compulsion, unless your book is a wild thing trying to break free, you shouldn’t be writing. That’s silly. There are as many kinds of writers as there are books. Ninety percent of writing is work. Extremely hard work. Not inspiration, not compulsion, not the power of the soul, or whatever. It’s work.

For a long time, I didn’t think that work was for me, and I was okay with that.

Ninety percent of writing is work. Extremely hard work. Not inspiration, not compulsion, not the power of the soul, or whatever. It’s work.

Katherine Arden

In college, I majored in foreign languages – French and Russian. I formed an ambition to be an interpreter. Or a linguist. I loved languages.

But life surprises you, and I think a well-lived life is one where you allow your life to surprise you. I had gone to college in Vermont, with long stretches abroad in Moscow. After five years, I was tired of freezing. So I decided to take six months off before applying to grad schools and live somewhere that wasn’t cold. I decided to go to Maui, Hawaii, where I lived in a tent and picked coffee on a farm.

Picking coffee is a boring and overcaffeinated sort of job and so I, bored for the first time in forever, started making up stories in my head.

I would like to pause here and defend boredom. There is nothing better for a creative person. I know that boredom doesn’t just happen to you in 2022. It must be sought, cherished. But try. Because when the outside stimuli stop, your mind – that springtide of everything you’ve read, and everyone you’ve met, all your thoughts, hopes, dreams, ambitions, the endless ocean of yourself – rushes in to fill the gap. That is where your stories are.

I was in Maui in the summer of 2011, and boredom was a little easier to come by back then. I didn’t have a smartphone. I didn’t have a laptop. I had a pen, a notebook, and the Pacific Ocean on the horizon. Absent much else to do, I started writing one of my stories down.

Boredom must be sought, cherished. Because when the outside stimuli stop, your mind rushes in to fill the gap.

Katherine Arden

People ask me all the time, how do you do it? How do you write a book? And the only answer I have is I don’t really know. It’s different for everyone. You may surprise yourself. Just don’t give up. It’s work. It’s so much work.

When I started writing the book that became my debut, The Bear and the Nightingale, I had very little idea of what I was doing. The unfinished woes of Anred nearly seven years prior weren’t really a guide. Fortunately, I had no expectations of myself. That is a good thing.

In fact, that is an important thing, and a feeling I have struggled to recapture ever since. The part of me – and I suspect, the part of you – that writes novels is like a child. Bright, eager, sensitive, a little random. Expectations, pressure, deadlines – all those grown-up, professional things – frighten the child. They make us awkward and tentative.

But in 2011, there were no expectations, and so I wrote. I wrote good paragraphs and awful paragraphs, blithely. The story brought me joy. It carried me with unexpected power. I wanted to know how the story ended. After three months scribbling in my sandy notebook, I knew I didn’t want to abandon it, like Anred, mid-angst.

So I made a decision. One of the hardest of my life. I delayed everything. Grad school, the real job, the real life. I decided to finish my book.

Don’t give up.

I was twenty-four and I don’t think there’s a parent in the world who wants to hear that their child has chosen to delay their career to live in a tent on a tropical island, taking odd jobs and writing fiction. I had not gone to school for writing. I had not, frankly, shown a particular aptitude for writing.

This is why I say don’t give up. Because people will ask, why you? Why this story? Are you qualified? Nearly everyone fails. What happens when you fail? You will ask yourself these questions. And the thing is, there isn’t an answer, besides, why not me. Why not this story. No, I’m not qualified. What does it mean to be qualified? I am a human, aren’t I? We are made of stories. I am enough. I have to be enough. Because I am all there is.

You can tell yourself that, but there will be days when you don’t believe it. Days when you think, I am wasting my time. Days when you think that the idea isn’t big enough, the story isn’t interesting enough.

This is where I am wary of all the people who ask is writing your calling? Because if you start thinking writing is your ultimate gift, your fate, or whatever, then you won’t have recourse against the days when that feels like the furthest thing from the truth. When you can hardly form a sentence, when your novel is plodding and incoherent. This day will happen to you. It happens to everyone.

You must simply keep going. It’s not about the muse. It’s about the work. You don’t need to believe in yourself all the time. Just go. Just write. Move your fingers. You are enough.

You must simply keep going. It’s not about the muse. It’s about the work. You don’t need to believe in yourself all the time. Just go. Just write. Move your fingers. You are enough.

Katherine Arden

So I stayed on Maui. I kept writing my novel.

I moved out of my tent on the coffee farm, into a yurt on the North Shore. I shared it with another girl. It was the best deal on the island. The bathroom was built on a platform in the woods. It had plumbing – sink, toilet, shower – but no walls or roof. I remember going out at night to pee, getting rained on – it is always raining on the north shore of Maui. I remember the grass sticking to my bare feet, the banana trees rippling as the rain fell. I remember wondering what on earth I was doing.

I kept writing.

You don’t always have to know what you are doing. A part of you knows. It does.

I finished my book.

Nothing happened. I couldn’t get an agent interested. I had ideas for a trilogy, but – well, no one was interested. It was crushing. I knew I had to stop. To get on with my life. Can’t live in a yurt forever. I could be a lot of things, I knew. An interpreter, like I’d meant to be.

It hurt, though. Because I spent three years writing my first book, and waiting for someone to notice it, and in those three years, I’d realized I really enjoyed writing fiction. I’d nurtured this tiny dream of being a writer.

But I was realistic. I got a better job, doing marketing for a real-estate office. I planned to get a realtor’s license. I would work for a bit, save money. And then go to grad school.

And I guess that’s the final lesson. When you are truly at the end, when you’ve tried your best, and done what you could, sometimes the world steps in and surprises you. And it did. Two weeks into my job at the real-estate office, I got the first offer from a publisher for my trilogy. One book became two, two became three. Last month, I turned in number seven. Grad school never happened.

I didn’t expect the way things turned out. But life wanted to surprise me and I let it. I’m happy it did. I said writing is ninety percent work, and it is. But the rest of it is the idea, the passion, the hope, the dream. It’s important to nurture it. And if you do, life just might surprise you.

Good luck, everyone, on your writing journey.

Write your novel with one-to-one personal author coaching on our acclaimed online writing courses. Sign up now to finish the book you've always wanted to write.

January 22, 2022

How to Write a Fantasy Series

Our author tutor Tasha Suri is the award-winning author of The Books of Ambha duology (Empire of Sand and Realm of Ash) and the epic fantasy trilogy The Burning Kingdoms which starts with The Jasmine Throne. She won the Best Newcomer Award from the British Fantasy Society in 2019 and was nominated for the Locus Award for Best First Novel.

When TIME asked leading fantasy authors – George RR Martin, Neil Gaiman, Tomi Adeyemi, N.K. Jemisin and Sabaa Tahir – to compile a list of the 100 most fascinating fantasy books of all time, dating back to the 9th century, they included Tasha Suri's Empire of Sand. Suffice to say, Tasha Suri knows how to write a fantasy series! Over to Tasha...

From the desk of Tasha Suri.

From experience, I know the thought of writing an epic fantasy series or saga can feel overwhelming. Writing one book is hard enough, you may think. No need to complicate things further. I certainly felt that way, before I tackled my first duology! How can you wrap your brain around the concept of writing two, or three, or even more books in the same world?

No one size fits all, and no rules are absolute, but I want to give you some guidance to set you on your way. Follow these five suggestions, and I have confidence that you’ll be able to begin building your own fantasy series – as small or as grand a series as your heart desires.

1. Read a fantasy series

Ideally, read a lot of different fantasy series. Get your hands – and your eyes – on duologies and trilogies and series that span many books. Read books that bring you joy! The more you read, the more you will gain an instinctual understanding of what it takes to write a series. Steep yourself in what you love, and you’ll begin to understand how to write the kind of series you love, too. There’s no shortcut to this. Just read, and read, and read some more, and your knowledge and your imagination will grow in turn.

2. Plan your series

Some writers love to plot and some loathe it, but no matter what camp you fall into, you’re going to need to plan where your series is going. The plan doesn’t need to be perfect, but you do need to broadly sketch out the journey your series is going to take. Ask yourself how many books you’re likely to need. Are you writing a duology, divided perfectly into two halves? Is your series a trilogy, with a firm beginning, middle and end?

Some writers know every twist and turn on the path from one end of a series to another; some only know the vague direction they’re going. If you’re firmly not a plotter, then I encourage you to think of your series plan as a lamp illuminating the way ahead, so that you can keep putting one foot in front of the other – or one word after the next – until you find your inevitable way to the end of the path. Your plan can be vague, but it does need to be complete enough to guide you.

3. Give your series an overarching plot

You’re writing a series because you have a story idea that can’t be contained in a single book. What larger, book-spanning plot ties your series together? Who – or what – is the great enemy your protagonists are going to have to face at the end of your series? What great peril threatens your fantasy world and its people? Your overarching plot doesn’t have to centre on a great enemy or threat, of course – but conflict is often a great driver for story.

You’re writing a series because you have a story idea that can’t be contained in a single book.

Tasha Suri

4. Make your first book a satisfying standalone

The first book in your series should still be an enjoyable read on its own. On a mercenary level, a book that could stand on its own or have sequels is far easier to sell to a publisher than a book that must absolutely be part of a series. But it’s also true that many readers will pick up your first book, and love it, and… read no further. Think of the piles of books by your bedside or on your e-reader that you haven’t touched yet; can you blame them?

Even a dedicated series reader will certainly never pick up your second or third book if the first doesn’t speak to them, so it’s in your best interests to make your first book a satisfying read on its own merit.

How do you do that?

Write the best possible story you can. Pour everything you love into that first book. Don’t reserve your best work for future instalments. By writing the best work you’re capable of now, you’re building your craft muscles and ensuring you’ll be an even better writer – with even better ideas – when you approach your sequels.

5. Don’t stray from the path

This final point is a message for the writer you’ll be one or two books into your series. Tuck this advice away for when you’ll need it most:

Remember the overarching plot you sketched out? The path you laid out, spanning a specific number of books, exploring the lives of a particular set of protagonists?

Don’t stray too far from that vision.

Part of the magic of writing is discovery. As you write your series, you’ll learn things about your story you never expected, and that isn’t anything to fear. But it’s also very easy to accumulate subplots and side characters as you go, and one day you’ll find yourself juggling a dozen plots and hundreds of characters, trying to find satisfying conclusions to all their journeys, with no idea what happened to the path you began on. Keep your eyes on the road ahead. Remember what the heart of your series is, and hold true to that right until the very end.

Now you have five broad rules to guide you, and all your ideas buzzing brightly in your head, go out there and write! Think of creating your own series as your very own epic quest. Good luck on your journey. I’m sure you’ll write a series to be proud of.

Write your novel with one-to-one personal author coaching from Tasha Suri on our famous online writing courses. Sign up now to finish the book you've always wanted to write.

January 15, 2022

Books for Writers

From the desk of Emylia Hall.

What exactly is a book for a writer? Any work that inspires, motivates and educates can be classed as such.

As a fiction writer, I learn a great deal about writing from reading novels; beloved works of fiction have been – and continue to be – as instructive as any ‘craft’ book for me. We take that tack at The Novelry with our brilliant collection of Hero Books. But I love a book that’s specifically about the writing process, whether focused on practical matters, or with a more spiritual vibe.

The kind of craft books we connect with are deeply personal – perhaps more so than with fiction. (Discuss.) Sometimes it’s a question of timing: the right book at the right moment, chiming with a particular problem we’re encountering in our writing, or an area where we’re feeling ripe for enlightenment. As any list of writing craft books will be hotly debated, I’ll be leaning into subjectivity and first offering up my own Top Ten (plus a few extra), before sharing the favourites of some of our team here at The Novelry.

I’ve included books on my list that cross over into memoir or essay collections, works by writers that instruct and inspire, even if they’re not strictly categorised as craft books. Having a solid grasp of technique is one thing; feeling motivated and resilient enough to show up and write through thick and thin is quite another. Therefore, books that feed my soul – and my appetite for being creative – are as useful to me as those of a more intellectual inclination. I think of such books as being something like treasure maps. I’ll pore over them in anticipation of the riches I might glean, hoping that around the next bend I’ll hit the jackpot and make that life-altering discovery. The hunt is always on. And that’s just the way I like it.

I think of such books as being something like treasure maps.

Emylia Hall

1. On Writing by Stephen King

The first book on writing craft I ever read. It was 2008 and I was working on what would eventually be my debut novel. We hadn’t been living in Bristol long and when I think of those early months in the city it was all about prioritising a more creative life. One afternoon I took a long bath in our tiny flat and started reading On Writing. I emerged hours later – water cold, skin pruned, head buzzing with inspiration.

I responded to King’s informality, his forthrightness, and the kind of rad image of him pounding out 2,000 words a day with hard-rock blaring.

This isn’t the Ouija board or the spirit-world we’re talking about here, but just another job like laying pipe or driving long-haul trucks.

Stephen King

The fact that the book is also part memoir made it even more immersive to me; in my quest to be a novelist, I was every bit as interested in how writers lived as I was in any toolbox they might keep stashed within their desks.

2. Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder

A screenwriter friend recommended Save the Cat! as being useful for novelists too – and he was right. Funny, perky, smart and simply expressed, it’s easily the most well-thumbed book on my ‘craft’ shelf. I love the directness and simplicity of the Beat Sheet (who else has started yelling out ‘page 12 catalyst!’ when they’re watching films? Just me?) As I started out writing my last two novels, I copied those 15 beats down in the front of my notebook and would repeatedly refer to them through the process; even if my plots don’t end up exactly matching, nevertheless I feel reassured just having them close.

I also suspect that there’s some sneaky psychology going on. I approach the book in a lighter frame of mind because it’s squarely aimed at screenwriters not novelists; I feel like I can take from it what I like, on my terms, and give myself a little pat on the back in the process – a bit like turning up to an optional class at college. More than a decade after the publication of Save the Cat! Jessica Brody published Save the Cat! Writes a Novel. Any fans here? It’s on my TBR pile, but I haven’t got to it yet; while I’m interested to see how it expands and refocuses Snyder’s book, I suspect the original will always have my heart.

3. Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

I have a proper crush on Bird by Bird. It’s the writing book that, with its witty, warm company, has tickled me more than any other. And it’s moved me more than any other too – from the story of the origin of its title (a touching piece of advice from Lamott’s father to her brother when faced with a daunting homework assignment) to the book’s final paragraph, which I can't read without crying:

[Through writing] we are given a shot at dancing with, or at least clapping along with, the absurdity of life, instead of being squashed by it again and again. It’s like singing on a boat during a terrible storm at sea. You can’t stop the raging storm, but singing can change the hearts and spirits of the people who are together on that ship.

Anne Lamott

I mean! Lamott is brilliant at reassuring her readers as much as challenging them, acknowledging our frailties and vanities. Bird by Bird feels like the best kind of creative therapy: it makes me want to go and write.

4. Crash Course by Robin Black

This collection of essays by Robin Black, author of the brilliant novel Life Drawing, is sub-headed ‘Essays from where writing and life collide.’ It’s honest, wry and spirited. In particular, I’ve gone back to A Life of Profound Uncertainty and The Success Gap again and again, where Black articulates the many uncertainties of the writing life – whether a writer is published or unpublished – and the ‘chaotic fuckedupedness of the profession.’ She’s simultaneously philosophical and no-nonsense – and quick to muster a smile.

Aspects of craft are woven through more memoir-driven pieces, and it’s all fuel to the fire. Give it Up, another stand-out essay, is an encouragement to resist the temptation to withhold a secret until the story’s end. Black cautions:

Using an absence of information to generate the majority of a story’s narrative momentum can allow a writer to slack off on every other element.

Robin Black

And how much more immersive, and textured, it can be to come up with something else to ‘replace the taunting of secrecy’, essentially to engage on a more emotional level rather than structure a story so that a reader only wants to rush to the reveal. And that’s food for thought for every kind of writer – even the whodunnits!

5. Into the Woods by John Yorke

This could have been the one that got away. One wet day in 2016 I took my toddler son to a play-café and settled into an armchair in a far-flung corner. I left him to play happily with the (actually pretty grimy) toys, while I pulled Into the Woods out of my bag and started reading. I felt, deliciously, like I was stealing time, and I really did want to learn more about story structure – not just the ‘what’ of it, but the ‘why’ too, which is where Yorke’s seminal book digs deeper than so many others. That day, my tired and distracted brain couldn’t cope with its depth. I stuffed it back in the nappy bag and I didn’t revisit it again until joining The Novelry in 2020. I’m so glad I got there eventually.

Ceaselessly erudite, illuminating and rousing, Into the Woods is now a firm favourite, exploring every aspect of storytelling, and drawing upon references from Elizabethan playwrights to Jaws and Only Fools and Horses. It’s often beautifully expressed, too:

Once upon a time God was the story we told to make sense of our terror in the light of existence. Storytelling has that same fundamentally religious function – it fuses the disparate, gives us shape, and in doing so instils in us quiet.

John Yorke

6. Changing my Mind by Zadie Smith

It’s such a confidence trick, writing a novel. The main person you have to trick into confidence is yourself.

Zadie Smith

While only one of the essays within this collection directly addresses the writing process, it’s a rich and inspiring read for anyone interested in what it means to write. Smith takes us inside her mind with essays arranged under the following categories: Reading; Being; Seeing; Feeling; Remembering. It is within Being that she directly addresses her process, in a version of a lecture first given to Colombia’s Writing Program students.

Smith covers Macro Planners and Micro Managers (her slightly classier form of ‘plotter and pantser’); as a Micro Manager herself, Smith says, ‘When I begin a novel, I feel there is nothing of that novel outside of the sentences I am setting down. I have to be very careful: the whole nature of the thing changes by the choice of a few words.’ Since first reading this collection in 2010, every time I’ve finished a novel since I’ve thought of the following words and the image they conjure – and they’ve made me smile and smile:

I think sometimes the best reason for writing novels is to experience those four and a half hours after you write the final word. The last time it happened to me, I uncorked a good Sancerre I’d been keeping and drank it standing up with the bottle in my hand, and then I lay down in my backyard on the paving stones and stayed there for a long time, crying. It was sunny, late autumn, and there were apples everywhere, overripe and stinky.

Zadie Smith

Other essays, covering such subjects as Smith’s first reading experience of Zora Neale Hurston, her father, movies and a week spent in Liberia are no less inspiring for writers: they show us who this remarkable author and thinker is, what she loves and what matters.

7. Writing the Other by Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward

I first discovered this How-To (and How-Not-To) book through the website of the same name. Speculative fiction writers Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward have been running courses called Writing the Other for twenty years, addressing writing about characters whose race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age and so on differ significantly from an author's own.

They use examples from their own experience throughout, for instance how they each ‘depart from the dominant paradigm,’ the importance of acknowledging privileges, and the danger of generalisations – and how that’s applied to the writing process. Practical exercises challenge the reader to step outside their comfort zone and the limits of their own experience, while examples of character creations that get it wrong – ‘Patronizing Romanticizations’, ‘Sidekicks-R-Us’, ‘The Saintly Victim’ to name a few – are discussed.

Throughout, the authors emphasize the importance of openness and willing while doing the work:

Learning boils down to making mistakes, seeing what you’ve done wrong, and making corrections. If you’re going to be a writer, if you’re going to improve, you mustn’t flinch from this process. Do your best. Eventually, you’ll figure out how to make your best better.

Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward

That’s a sentiment applicable to every aspect of the process. Accessibly written, smart, and challenging, Writing the Other continues to give me much to think about – and want to do better.

8. Howdunit, a Masterclass in Crime Writing by Members of the Detection Club, edited by Martin Edwards

Published in 2020, in celebration of the Detection Club’s 90th birthday, Howdunit is a mighty tome featuring nearly 100 essays from classic and contemporary authors on the art and craft of crime writing. The result is a total treasure trove.

We have Ian Rankin on Why Crime Fiction is Good for You (‘If an author makes us curious, we will keep turning the pages. In a sense therefore all readers are detectives, and the crime novel merely codifies this essential aspect of the pleasure of reading.’) and Sophie Hannah with Optimal Subterfuge, where she dissects the anatomy of a twist (‘any kind of reversal of what we thought we knew’) and suggests how to skilfully manipulate readers into misleading themselves. There’s also P.D. James writing on place, and how settling on a particular landscape, imagining ‘all the lives that have been lived on this shore’, helps give a novel ‘a life’ while still only in idea form.

With insight and advice from so many greats, including Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Ann Cleeves, Val McDermid, Mark Billingham, John Le Carré and more, I’d recommend this book to anyone writing crime. Or, in fact, anyone writing full stop.

9. The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

A slim little volume that’s a delight to read. Described by the Boston Globe as ‘a kind of spiritual Strunk & White’, it’s as if Dillard has invited us into her cabin on Cape Cod, set the coffee going, then tells us how it is for her. The effect is captivating. The first chapter begins with a quote from Goethe: ‘Do not hurry; do not rest,’ which establishes the tone for a book that brilliantly articulates the life-long, but elected, struggle that is writing.

In vivid prose, and much enjoyment of imaginative analogies, metaphors, and anecdotes, Dillard talks about process. Consider this:

I do not so much write a book as sit up with it, as with a dying friend. During visiting hours, I enter its room with dread and sympathy for its many disorders. I hold its hand and hope it will get better.

Annie Dillard

And this:

At its best, the sensation of writing is that of any unmerited grace. It is handed to you. You search, you break your heart, your back, your brain, and then – and only then – it is handed to you. From the corner of your eye you see motion. Something is moving through the air and headed your way. It is a parcel bound in ribbons and bows; it has two white wings. It flies directly at you; you can read your name on it. If it were a baseball, you would hit it out of the park. It is that one pitch in a thousand you see in slow motion; its wings beat slowly as a hawk.

Annie Dillard

10. A Swim in the Pond in the Rain by George Saunders

This was a recommendation by a member during one of our Story Clinic sessions here at The Novelry – and I’m so glad I was on hosting duties that day. What a book! I already knew I loved how Saunders writes about teaching writing (his long-form essay in The New Yorker in 2015, My Writing Education: A Timeline, is a favourite of mine) so admittedly I came to A Swim in a Pond in the Rain ready to be enchanted.

The book is structured around seven classic Russian short stories which Saunders has been teaching for twenty years. The reader is guided through each story, page by page, with Saunders examining how narrative works, authorial choice, and the line by line effect on the reader. It’s seductively done, and Saunders’ ceaseless humour, and his immense but easy intelligence, make for the best company. This book has made me think about an author’s decisions – and control – in a deeper way than ever before. And Saunders’ summary of his own book’s impact is illustrative of his manner throughout:

If something in this book lit you up, that wasn’t me ‘teaching you something,’ that was you remembering or recognizing something that I was, let’s say, ‘validating.’ If something, uh, anti-lit you up? That feeling of disagreeing with me was your artistic will asserting itself (…). That resistance is something to note and be glad of and honour.

George Saunders

Generous in every way, it’s a book to love.

So that’s my top ten. I’m revved up now, having been happily lost in my ‘craft shelf’, and I‘d like to also mention Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert, which does so much for my creative soul; the chapter in which Gilbert gives an account of meeting Ann Patchett – and something magical happening – is deliciously wacky and, well, why not true?

Speaking of Ann Patchett, I highly recommend This is the Story of a Happy Marriage, a memoir that has many nuggets of writing process gold within it. And, since we’re on the subject of marriage, it would be remiss of me not to mention my husband Robin Etherington’s How to Think When You Write books, graphically-designed compendiums of tips based on his love of comics, video games, movies and novels, which I’ve had the pleasure of copyediting, as well as reading, ahead of his Kickstarter campaigns. I could go on and on (E.M. Forster? Eudora Welty? Ursula K. Le Guin? And publishing this spring, Nikesh Shukla’s Your Story Matters) but now it’s time to hand over to the team at The Novelry, and hear some of their favourites too...

Tasha Suri: Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing andWorkshopping by Matthew Salesses is a very new book, published in 2021, but it’s already become a firm favourite of mine. I dip into it whenever I need a little courage. Salesses challenges our preconceived notions of what makes good craft, and asks us to question all the writing rules we’re internalised and built around ourselves and our stories like walls. I always find writing advice that makes me think and challenges me really sparks my creativity, and Craft in the Real World does that beautifully. It’s smart and brave and difficult, which makes me want to be a braver writer in turn.

Jack Jordan: Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder is a book I find myself continuously revisiting, usually when I'm in the throes of writing a first draft. It is the sort of book that you don't necessarily need to re-read again, but flick through in times of need (or crisis!) and the answer will be there on the page waiting for you. When finishing a novel seems like an unattainable task, Save the Cat! lays out the rules so clearly, gifting all writers the behind-the-scenes formula to writing. It always helps me get back on track.

Mahsuda Snaith: John Yorke's Into the Woods is great for plot structure; Wired for Story by Lisa Cron is great for knowing how story works, and Elizabeth Gilbert's Big Magic and Ray Bradbury's Zen in the Art of Writing are both joyous and fun reads about writing. How to be a Writer by Sally O'Reilly is the only book I've read that solely focuses on the practicalities of being a writer i.e. networking, contracts, day jobs.

Kate Riordan: Applying cutting-edge neuroscience and psychological research to our human need to tell stories, Will Storr's The Science of Storytelling is fascinating and mind-bending. Arguing that our whole lives are one huge act of storytelling – making us naturals at it – I loved the scientific approach to a craft that often feels so chaotic and ungraspable.

Katie Khan: The Anatomy of Story by John Truby contains 22 steps I find a good way to ensure your novel is developed with key elements from the inside, rather than imposing an external plot structure upon it from the outside. I also find Truby's character explanations really helpful, including characters who are ally-opponents and opponent-allies, which is so neatly explained. I often use Truby’s 22 steps in tandem with Blake Snyder’s 15 beats from Save the Cat! to make sure I have all the ingredients a story might need. My Post-It note wall ends up looking like a board from a crime scene!

Polly Ho-Yen: The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human, and How to Tell Them Better by Will Storr does exactly what its title promises. Its in-depth scientific approach gives clear guidance on how to become a better storyteller. It's a fascinating read!

Lily Lindon: I found Stephen King's On Writing and John Yorke's Into the Woods very interesting and helpful: King's for no-bullshit tips and easy readability, Yorke's for deep-dive nerding into analysis of storytelling structure. Also, some rogue recommendations: the diaries and letters of Virginia Woolf, for insight into a working writer's mindset with all the highs and lows of creation, and finding time to be alone in a room of one's own. The other is a very short book called Ongoingness: the End of a Diary by Sarah Manguso, which is an unconventional memoir about her obsessive diary-keeping. As many writers keep journals as well as their fiction, I think it's interesting to think about what is worth recording, and why we feel this need to write, how we accept the balance of living and memorialising that living.

Craig Leyenaar: I recommend Wonderbook by Jeff Vandermeer in my SFF workshop – it’s fantastic. Seemingly focused on the speculative, it’s a great guide to storytelling for everyone.

Louise Dean: Most writers are familiar with The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell, but the female journey has been often overlooked. In The Heroine’s Journey, Maureen Murdock kicks us off on a scintillating ride, beginning with why so often in books by women, the mother gets killed to get the story started! Insights into the magic of womanhood. A must-read. (Gail Carriger's book of the same title, published 2020 is also brilliant.)

Emylia Hall is an author tutor on our famous online writing courses which offer personal writer coaching. Sign up now to finish the book you've always wanted to write.

Explore the website to choose the course and payment plan that works for you, or book a free call to meet one of our award-winning author tutors.

January 8, 2022

The Moral Dilemma

From the desk of Jack Jordan.

As human beings, morals are at the heart of who we are. On a personal level, morality is the compass that helps us navigate life, and on a broader scale, morals are the laws of the land, the intricate maze of unspoken rules we all live by. Our personal morals are so intertwined with our society that we may not even recognise the number of choices we have to make every day – nor the opportunities we have to stray.

Every minute, we choose to do the right thing. We choose to wake up to go to work. We choose to pay our taxes. We choose to sit in traffic rather than mount the pavement in a wild free-ride to get to where we need to go. We choose to do the right thing, not just because of the beliefs that have been instilled in us, but because we know of the consequences that await us if we do wrong. These morals – and the choices that accompany them – live within all of us, whether we recognise these as right and wrong, good or bad, or good vs evil.

"Good and evil are so close as to be chained together in the soul."

Robert Louis Stevenson

It is these fibres of humanity we all live by, for fear of being a bad person, but also for fear of paying the price of making the wrong decision. They are so deeply ingrained in us that being forced to go against one’s morals can tear a person apart.

And as writers, we get to have a lot of fun with that.

This is ‘the moral dilemma’.

A moral dilemma is a situation in which a person must make a difficult choice between two courses of action, either of which force them to betray a moral principle. It is the reason why Romeo and Juliet has stood the test of time; why Sophie’s Choice has become so prominent in popular culture. Moral dilemmas are experiences that both intrigue and terrify us.

In fiction, the moral dilemma is an invaluable tool. When it comes to plot and structure, a dilemma drives the story forward with tension and foreboding. On a deeper level, it shows the protagonist's humanity (or lack thereof), allowing the reader to relate and bond with them emotionally. Because what the moral dilemma ultimately does is to put the reader into the protagonist’s shoes and prompt them to ask themselves: what would I do in this situation?

In Adrian McKinty’s The Chain, a mother is targeted by dangerous masterminds and must abduct another person’s child or risk losing hers forever, joining a chain of parents just like her – kidnapping another child to save their own. In Sophie’s Choice, perhaps one of the most infamous moral dilemmas, Sophie reveals a long-held secret to the narrator: when taken to a Nazi concentration camp with her two young children, she was forced to make a split-second decision and choose which one of her children would live, and which would die.

On the surface, these decisions seem impossible to make. Yet, they are equally impossible to ignore because the consequences of not doing so are too great – the repercussions of inaction anchor the moral dilemma. The key to a stellar dilemma is not just the choice your protagonist must make but the ramifications of them making the wrong decision.

How to craft a moral dilemma

As a writer, I am consistently cruel to my characters because I know that by dropping my protagonist into the pot and whacking up the heat, the readers will connect with them on a much deeper emotional level. In my upcoming thriller, Do No Harm, the moral dilemma was the first thing that came to me. I was undergoing a minor procedure for which I needed to be put under general anaesthesia. Just before the needle was about to be inserted, I was hit by a sudden fear: I didn't know anyone in the room. I was trusting strangers with my life, my body, my dignity. Luckily, the team were nothing but kind and professional. When I woke up in my recovery room (and the anaesthetic had worn off), I immediately began to wonder what it might have been like if the medical team had had an ulterior motive. What would make a medical professional do such a thing? What might the stakes be?

And thus, Do No Harm and the moral dilemma at the heart of the novel was born:

A notorious crime ring abducts the child of leading heart surgeon Dr Anna Jones and gives her an ultimatum: kill a patient on the operating table or never see her son again.

In this moral dilemma, Dr Jones must make a choice: betray her oath to do no harm, or lose her son forever.

Ask yourself the following questions:

What matters most in the world to you? And how far would you go to protect it?

What is something you could never bring yourself to do? And what desperate situation would you have to be faced with to go through with it?

Once you have come up with your dilemma, the next step is to dig deeper into the consequences of each decision the protagonist could make.

You could create an outcome that is morally corrupt but recoverable, like The Chain, in which the child the protagonist abducts will survive if their parent follows through with the same demands. Or you could take the darker route, delving into the character’s soul like Sophie’s Choice: in choosing one of her children to live over the other, Sophie must live with the consequences of her actions.

To conjure up the consequences of your moral dilemma, ask yourself these questions:

Who is your protagonist? What matters most to them?

How can you put that in jeopardy? What ultimatum can you give them to up the stakes?

What are the consequences of the decision they have to make? What will happen if they do, or don’t, go through with it?

Whether it’s child abduction, heart surgery or life-and-death decisions, it is these grandiose levels we can go to as writers, thrusting our characters to the edge of their morality, because as well as giving them a good adrenaline rush, this also allows our readers to test their own moral compass and reconfirm who they are. According to Psychology Today, we are wired to enjoy it.

"Evolution has sharpened humans’ survival instincts to the point where it feels natural and sometimes enjoyable to, well, survive. Even from a young age, we enjoy exercising our survival instincts and homing in on fear in a safe environment."

Psychology Today

From childhood games of hide and seek, binging true-crime documentaries, or rubberneckers passing a pile-up and unable to look away, we as humans are fascinated by our own survival, and dabbling in the darker side of our human nature. The moral dilemma is the ultimate gift to explore who we are.

Examples of great moral dilemmas in fiction

Sophie’s Choice by William Styron

Sophie reveals she was forced to choose between which of her children should live, and which should die.

Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman

Sephy, a Cross, and Callum, a Nought, who should be bitter enemies due to their statuses in society, embark on a forbidden love affair that risks the very foundation of their lives.

The Chain by Adrian McKinty

A mother is targeted by dangerous masterminds and must abduct another person's child or risk losing hers forever, joining a chain of parents just like her: kidnapping another child to save their own.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

When Jane discovers Rochester is already married to the woman in the attic, she must choose between love and honour: either she can break her own heart and happiness, or surrender her reputation in an unforgiving time period.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Anna has beauty, wealth, popularity and an adored son. But when officer Count Vronsky enters her life, she is forced to either remain in her marriage and stay at the top of society or succumb to her desires and sacrifice her status and everything she holds dear.

Hostage by Clare Mackintosh

A flight attendant must choose between saving her child or the passengers onboard a non-stop flight from the UK to Australia. ‘You can save hundreds of lives… or the one that matters most…’

Twilight by Stephanie Meyer

Bella must choose between Edward the vampire, or Jacob the werewolf – either she can die and live with Edward for eternity, leaving her friends and family behind, or fall in love with the werewolf next door, and keep her soul.

Do No Harm by Jack Jordan

A notorious crime ring abducts the child of leading heart surgeon Dr Anna Jones and gives her an ultimatum: kill a patient on the operating table or never see her son again.

“The more imminent you make the choice and the higher the stakes that decision carries, the sharper the dramatic tension and the greater your readers’ emotional engagement.”

Writer's Digest

Give your protagonist an impossible choice, and force them to take a path; if you’ve got yourself a high-stakes moral dilemma, tension and mayhem ensue, regardless of the direction your protagonist decides to take.

Jack Jordan is an author tutor on our famous online writing courses which offer personal writer coaching. Jack's new novel Do No Harm is published by Simon and Schuster on 26th May.

New Year, New Novel? Sign up now to finish the book you've always wanted to write.

Explore the website to choose the course and payment plan that works for you, or book a free call to meet one of our award-winning author tutors.

January 1, 2022

Writing a Novel in 2022

The last lines of the poem Lockdown by the Poet Laureate Simon Armitage were inspired by the mythology of the village of Eyam in Derbyshire.

the journey a ponderous one at times, long and slow by necessarily so.

They may console writers who have not made the progress hoped for in 2021, and I'm here to bring you words of cheer and a plan for the new year... Read on, dear writer.

The story goes that the plague came to the village of Eyam in 1665 when a flea-infested bundle of cloth arrived from London for the local tailor. Within a week his assistant George Viccars, noticing the bundle was damp, had opened it up. Before long he was dead and more began dying soon after. As the disease spread, the villagers turned for leadership to their Rev. William Mompesson and the Rev. Thomas Stanley. (Next slide, please, Reverend…)

The villagers agreed to accept strict quarantine to prevent the spread of the disease beyond the village boundary. They were supported by the Earl of Devonshire, and by other charitable but less wealthy neighbours, who provided the necessities of life during their period of isolation. The plague ran its course over 14 months and according to accounts, it killed at least 260 villagers, with only 83 surviving out of a population of 350.

Lockdown, the poem by Simon Armitage, references the star-crossed lovers of Eyam. Emmott and her suitor Rowland, from neighbouring Middleton Dale, came to see each other each day across the quarantine boundary, until one day Emmott failed to appear…Still Rowland came, day after day, for months.

If the stories of Eyam sound like the stuff of fiction, that’s because they were invented. A description of the plague at Eyam was first penned by Anna Seward, the 18th-century poet, and appeared in an edition of her letters edited by Walter Scott. More details appeared in writing two centuries after the event when William Wood published, “The History and Antiquities of Eyam” (1842). Later editions bore the title “Legends of the Plague”. Eyam has continued to capture the creative imagination of writers. In October 2018, “Eyam”, a play based on the plague, was performed at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London.

Eyam is sometimes held up as an example to the world of how we can tackle the coronavirus pandemic. The voluntary quarantine cost the lives of many but it stopped the plague spreading. So we’re told. In fact, there is evidence of many, especially the wealthy, making a run for it...

Surprise, surprise!

It wasn’t physical contact that kept Emmott and Rowland faithful to their arrangement, but the mere sight and sound of each other. To be seen, to be heard, is that not what we deeply crave? If you’ve had a miserable time of it lately, despite being lucky enough not to get seriously ill, the chances are you’re missing the spontaneity of human interaction and conversation, unscripted and unpredictable.

Conversation can fly in any direction, and brings with it surprise after surprise. This is the raw material of the writer; the mistakes we make when our thoughts slip the shackles of probity and become spoken words. The things we do, the thing we never meant to do, or would never have done were we not together. We surprise ourselves.

What does a writer do with these human errors? We write them down. We preserve them. A writer reaps and keeps what was not meant to be said or what should not have been done.

So, what stories shall we tell, about this time we're living in?

Many are reluctant to tackle a story we find demoralising, yet in time, we will find stories of heroism, even if we have to invent them. That is what we do, don’t we? We create heroes. Our best memories, the things we cherish have at their centre some sort of heroism.

My wish for you in 2022 is that your writing honours the infinite capacity of human beings to surprise us all.

A happy new novel!

If you’re about to start writing a novel, it’s likely your fears are:

Motivation – seriously, am I going to do this? Because if I don’t I’ll feel bad.

Structure and Plot – how the hell do I approach the storytelling and what happens when? Will I run out of material? What happens next? (And repeat.)

We know how it is, and we created our programme of coaching, courses and community as a corset for writers with outsized creative tendencies. We'll keep you safe.

Motivation

Let's cut to the chase. Motivation? Don’t be too hard on yourself. See it as an indulgence, not a chore. Stop making an examination of this. It's not, nobody cares! Do it for you. Take time for yourself. Be a time thief. Steal what’s not yours! (I think we’ve all learned it’s time, more than money we really want, in these last two years.) Get up early, go to bed late, skip lunch. Close the door. Use our Golden Hour method as described in our courses. Remember, writing is your gift to you. Potter and play.

Structure

I suppose we’re all sick and tired of the old chestnut ‘planner or pantser’. It’s not an 'either/or' answer, it's 'both', and fast. At The Novelry we recommend a nimble hybrid method. A one-page plan – so you don’t get overwhelmed and heartily sick of the novel before you put pen to paper – and the glory of the wide-open acreage of the white pages with all their possibilities.

These two chums – the plan and the page – talk to each other. Every week, you correct the plan based on what’s happened on the page (think of it as the laboratory where you’ve tested your theory), then you move into the mystery again with a newly tidy plan. Over-rule a dead plan with lively mayhem. It keeps the book alive for you, the writer, and at first draft it’s all about you turning the pages. The reader comes later.

To get cracking, you need two things and everything comes from these.

Character

Character and setting will probably come to you hand in hand. You need to know your main character (MC) – and the pickle they’re in – very well indeed. You’ll want to know everything you can about them. You need to love your MC and take pity on them.

With the setting, whether that's place or time, know it so you can use it, and love it so you want to spend time there. It’s the stage. Once you know its corners, you can get to work.

Armed with these you can allow the story to unfold in your mind. Think of this duo as a little tealight, modest enough to provide enough of a glow to bring you back to the desk. We’ll show you how to scope out the idea, build the world of your story, and ensure you’ve got to grips with your main character’s problem or dilemma before you put pen to paper. Having these things in place makes for a smooth write.

The Arc

Consider the drama of the arc of change for our MC. How the story unsettles and unseats our hero for better or for worse. In life, a person may not change. In fiction, your main character must.

Some like to do a zero draft and race through the idea from A to Z to find the arc. Not me, but I can see how that might work for writing crime in particular. We’re all different. For my next novel, I quite fancy a midpoint (where everything changes), a divine moment of understanding at about two-thirds, and I prefer not to know the ending to keep me writing.

Setting

I don't always start planning a novel with a setting, but it's a good place to begin and many authors do.

The setting for my novels is sometimes borne of a place to which I've been a lovestruck visitor. A temporary locus. I call it 'vacation eyes' – when you're alert and alive to what you're seeing. Sometimes our sight dims when we inhabit a place too long. Give that setting a little bit of rose-tinted vision! You may be creating a place with world-building, going back to a place you knew in the past, or doing location visits for your novel. The main thing is you want to spend time there in spirit, you want to haunt it. You'll need to bring it to life with art for its charisma to shimmer. Here's how...

Charismatic Description

The artist JMW Turner lived in a small house riverside on Cheyne Walk in London in the mid-19th century. Known as 'the painter of light', Turner put things simply as artists do (and intellectuals don't as Charles Bukowski noted).

My business is to paint what I see.

JMW Turner

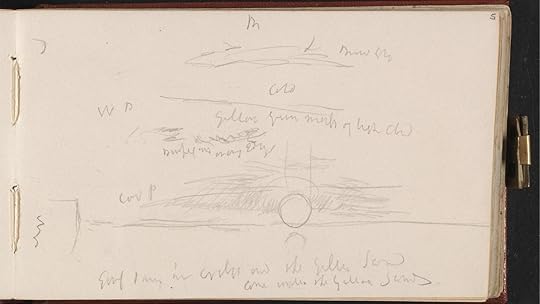

Turner’s sketchbooks show rudimentary depictions upon which he made simple notes of mood and colour and the direction of sunlight to inform his later paintings.

Be like Turner.

Swerve grandiloquence in your prose, dodge embellishment and metaphor, in favour of simply saying what you see.

This is the method of many modern writers from Ernest Hemingway to Sally Rooney. The job is to put the reader firmly in situ and at ease and move on smartly. Remember, modern readers don't need long descriptions and spoon-feeding. They've got Google if they’re really interested. Simply say what you see.

After Turner died, another painter took up residence in Cheyne Walk: James Abbott McNeill Whistler lived at 2 Lindsey Row from 1866 to 1878. Here's how he went about note-taking for a work of art.

Whistler would suddenly see the view he sought, stop and stare. He would then turn his back on the river and chant to his companion, “The sky is lighter than the water, the houses darkest. There are eight houses, the second is the lowest, the fifth the highest; the tone of all is the same. The first has two lighted windows, one above the other; the second has four.” If his companion corrected him on the smallest detail, he would stop, turn and stare again at the view he was memorising and repeat the performance – sometimes a dozen times before it was perfectly imprinted on his memory. Then with a brisk “Good night” he would be off to bed, the scene to be painted next morning gathering shape and tone in his mind’s eye....

... after a long pause he turned and walked back a few yards; then with his back to the scene at which I was looking, he said, ‘Now, see if I have learned it,’ and repeated a full description of the scene, even as one might repeat a poem one had learned by heart. (...) In a few days I was at the studio again, and there on the easel was the realisation of the picture.

Tom Pocock, Chelsea Reach

Record everything on a few visits. Make sure you record the sounds of the place – memory can be fickle. You'll want to look at nature too, and name the trees and birds to bring the place to life.

Now, to the business of adding charisma. Here's how.

What you're looking for are the inconsistencies, what we might not expect to be present so we can see a familiar place anew. For example, you can add depth and drama by paying attention to the light. To get the detail right, make notes, take photographs or record live onto your iPhone and give it some narrative to get the direction of the light and shadows at different times of the day. Light shows certain things at certain times, and the dark hides them so you’ll find you have a moving canvas for your story setting.

If you're writing historical fiction or world-building for a speculative setting, you'll want to create your own mental map. Again, try to go for depth of local detail rather than breadth, it's a shortcut to creating the illusion of a wider reality.

And relax! To get the balloon up of your illusion of place, you need to bring this luminosity of detail to the opening of your novel, to when we first enter the place, and thereafter mere notes will do (as we describe in our Lucid Compression prose method in the courses.)

If I’m writing historical, I’ll put together a reference reading list using fiction and non-fiction written about the place at the time. I won't use contemporary historical novels. (There's many a slip between cup and lip.) I want faithful true detail and I don't want it pre-filtered. Who knows what might yet inspire me?

Perspective

Once I have a place, and a character, I’ll start thinking about who is telling the story, from what perspective, and to what purpose. I may rule out a narrative voice, especially if I am concerned the story might come too close to home and if it deals with issues very close to my heart. Know yourself as a writer! Some writers work like movie directors and prefer to disappear from the story and simply use the camera of their prose to record events unfolding. Make your choice based on your own comfort. Start as the director to get going, if uncertain. You may find your way into 'voice' when you get your cast speaking.

Voice

Knowing who you are, as a person and a writer, is the first step to having a voice. If you do one thing with your New Year's resolutions, make peace with yourself. Maybe write a list of what’s bad about you, and what’s good about you and see how they’re linked. Bingo. That’s you, bang to rights.

Novels don't care if you're good or bad. You're never ugly to your novel. You’re either there – the creator, the parent – or you’re absent.

At The Novelry, we're all working writers, who have a good few years of writing between us. We'll work with you to find an approach to creative writing that helps you produce. It's all about the material at the end of the day. We're a broad church. Nerds, too. We love the technical stuff. Our only mantra is 'tools, not rules.' The lovely thing about being open to all approaches is that one will work for you and unlock your creativity for sure. You’ve got a block? We’ve got the key.

Writing a Novel - A Six Week Mini-Course

On March 6, I'm launching a 6-week mini-course sharing my live writing process as I scope out a novel and get writing!

The module will be available to members enrolled on our courses. (Psst! You've just got time to pack in The Big Idea Course and The Classic Course to come up with your idea and start building the world of your story if you sign up in January, before we start writing together in March.)

Each week, we'll prepare for the writing week ahead and you'll be given direction for your week that will coincide with and enhance our novel-writing course. In hour-long live sessions on Sunday evenings for six weeks we will cover:

1. Character and Place

The kind of book you want to write. Your intentions, please. The books you admire. The questions for which you have no answer. Why and how you should lovebomb your main character to get your novel going. Thoughts on the dramatic irony that will power the story and the midpoint. Settling upon the setting for the story.

(Homework: sketching out the opening as a test run to 500 words: test and rest!)

2. Casting Out

Building the cast of players. The four types, and the character who causes conflict. Tackling the matter of backstory. Using old material. Creating Hemingway's 'iceberg' to keep the story afloat.

(Homework: deepening characterisation details for the inner circle.)

3. Choosing and Working with a Hero Book

Taking one small powerful tale as a depth charger for theme. Looking at the characterisation arcs, themes and structures of novels we love as 'Hero Books'. You'll be guided to choose yours to help you stay on track and focused during your writing. In the mini-course we'll be looking at the following novels from our recommended 'Hero Book' list at The Novelry:

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

Less by Andrew Sean Greer

My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

Normal People by Sally Rooney

(Homework: the arc of your hero book.)

4. Your Theme

Nailing your intentions for the book and understanding the positive and negative aspects of the central theme and organising events and the cast to pull in either direction to create plot.

(Homework: the motivational factors of a title, an epigram and a song.)

5. Structure

Sketching out the key scenes of the story according to The Five Fs of storytelling. Fixing the matter of the midpoint. Steps up, steps down. What's the reader reading to find out? Motifs, recurrences, the pay off for the reader.

(Homework: a one-pager story plan).

6. A Strong Base

We'll look at the one-pager and redraft the opening chapter to include elements important to the theme, being sure to light the fuse for the explosion of meaning. This will make a nice solid base for us to move forward in writing our novels with confidence. In the last live working session, we'll review some pitches to ensure we have the stuff great books are made of.

Each week, we'll be working side-by-side to create material at a modest 250-500 words a day during the week and test our story from all directions as we deepen the interaction and engagement between members of the cast and allow unforeseen events to take us by surprise.

Let this year be the year you surprise yourself.

Don't leave it to someone else to change your life; take the matter into your own hands. Create with mischief, be wilful. Enjoy your writing. Let's make this our year, let's steal time and seize life and make of it what we want. Twenty-five years ago, a friend told me 'write what you need.' That advice has never got old, but this year it might turn gold.

Happy writing!

December 25, 2021

How to Write a Children's Book

From the desk of Polly Ho-Yen.

‘Twas the day after Christmas when all through the house, old memories are stirring we simply can’t douse…

Over the festive period, it’s near impossible not to think back to our childhood Christmases. Those memories are so much closer to the surface. I was plain ridiculous as a kid at Christmastime; I remember desperately wishing for snow, really feeling the wonder of it all by looking long and hard at the Christmas tree, totally giddy at the prospect of visiting the local shopping centre’s Christmas display. Our family tradition was to drive to a local deer park and see if we could spot the reindeer on Christmas Eve. If we caught a glimpse of their antlers, I felt buzzed with nothing less than pure joy. But if we didn’t spot them, my parents would tell my sister and I that the reindeer were simply getting ready for their upcoming sleigh ride; I was never able to hide my disappointment.

At Christmas, we are, I feel, particularly close to our past selves – especially that child who hung up a stocking and felt they really were close to magic as they looked at a grotto covered in fake snow next to an animatronic elf at a garden centre. As a writer for children, I often get asked: how do you convincingly write a child character?

As a writer for children, I often get asked: how do you convincingly write a child character?

As you might have guessed from my memories of Christmas, I have to confess I don’t feel oh so far away from my inner child, it’s alive and kicking inside me, probably a little too much. ‘Because I still feel like I’m five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve…’ is the answer. These past selves are still so close to me that it doesn’t feel difficult to tap into. Should I admit this in adult company? Well, what the hell, I’ve built my writing career out of it and in fact, I value it. If you are looking to write convincing child characters, connecting with your inner child is, I believe, vital.

If you are looking to write convincing child characters, connecting with your inner child is, I believe, vital.

How to connect with your younger self to write a child character

Here are some practical suggestions that may help you get back in touch with the magic:

Reminisce with people who knew you way back when

Deep dive into childhood photos

Read your own writing

Visit places you knew when you were a kid

Start a Memory Journal

Reminisce with people who knew you way back when

The stories we tell ourselves about our lives make us who we are and there’s no better way to take a trip down memory lane than to do it in the company of someone who was also there at the time. If possible, a good natter with a sibling or friend about time spent together when you were younger will tell you a lot. Perhaps it will turn to hysterics as you remember together the odd rituals you once gave so much importance. Maybe you’ll be bowled over remembering a place that’s been long forgotten, or an uncomplicated feeling of safety and warmth. The memories might not always be rosy, of course – in fact they can painful and may bring up other points of view that are not part of your personal narrative. Whatever comes up, accepting where these conversations lead you and being curious in the emotions they stir within is, I feel, the key to starting to step into the shoes of a child character and embracing the full range of feelings they are living through in your own fiction.

Deep dive into childhood photos

For more inspiration, dig out those dusty albums, if you can. Which photo appeal to you and stand out? Do you have favourites – and why do you think you’ve chosen those particular images? Can you recollect where it was, how you were feeling and the energy of that day? Do you feel connected or disconnected to your own small face in the photo? If you don’t feel that it matches your memory of that moment, why is that?

Read your own writing

Some people have a wealth of material they wrote as a child (to which I was always a little jealous), but of course we’re not all in that position. If you can lay your hands on anything you wrote when you were younger, I’d urge you to take a little look.

In the last few years, two things I wrote (for pleasure) as a kid have been found during clear-outs which left me with both mixed feelings and a sense of acceptance.

The first was a holiday journal in which I’d taken score of every table tennis game I played against my sister, documenting my growing feelings of resentment towards her as I lost each and every game. On one page I tried to ‘fix’ the score before scribbling it out, then added a postscript that my sister had seen the made-up score and we’d fallen out about it. My handwriting is cramped and close together, my frustration, sense of injustice and boiling rage skips off the page.

The other is a LETTER TO THE FAIRIES inviting them to visit me with the promise that I wouldn’t hurt them. It might sound sweet if I’d been younger but, unfortunately, I dated it. I was twelve years old! Surely I couldn’t have believed in fairies when I was twelve years old! But the proof is pretty damning. Mixed feelings, you see! But reading my own words takes me fully back to that gawky, emotional kid I know I still completely am.

Visit places you knew when you were a kid

Walking into any primary school transports me so quickly to my own primary school days that it’s astonishing. I think it’s because it’s an assault on the senses; the school dinners, the paint and pencils, the beanbags … I could go on. Visiting any place from your childhood will tap you into your younger days. School’s a good one because we all spent so much of our young lives there, but we each carry our own special places that are rooted to our childhoods.

Some of those places you might have only been to once – an unforgettable holiday or a trip – but I think it’s important to tap into the ordinary everyday of your childhood too, the truthful and unglamorous side. Perhaps it’s impossible for you to go back to those places, so you might need to find counterpart places that still jolt those memories.

Start a Memory Journal

Lastly, don’t depend on any other stimulus but simply free-write your way into your memories.

Use prompts to think back on any childhood memory and set yourself a challenge of writing non-stop about it for ten minutes. If you feel stuck then just write ‘I am ten years old, I am ten years old’ (or however old you were) on repeat until the memory takes over.

Here are some things to think about:

How did you mostly travel to school?

What was your bedroom like, growing up?