Louise Dean's Blog, page 5

June 11, 2022

Writing a Murder Mystery? Here are 5 Top Tips

From the desk of Emylia Hall.

Writing a murder mystery can be baffling and thrilling in equal measure. There was a moment while writing my second crime novel when I looked down at my notebook – with its lists of questions, criss-crossing lines and character names staring blankly back at me – and felt well and truly stumped.

You see, I knew whodunit, but I didn’t know how on earth my sleuths were going to figure it out. At that moment I felt like a wearied cop, working late, staring at the board in the Incident Room, knowing that the answer was there somewhere – but agonisingly out of reach.

Of course, the job of an author is a whole lot easier than that of an actual detective – amateur or otherwise. As writers, we can cook up means, motive and opportunity any way we like. We have limitless resources to throw at a case (though it might not feel like it, as the laundry piles grow and the children whine and the day jobs clamour and the writing time shrinks…). We can conjure new prime suspects out of thin air.

All things considered, solving a fictional crime should be a doddle. But, of course, it isn’t.

My induction into writing a murder mystery

I consider myself a rookie when it comes to writing murder mysteries. My debut crime series is set to be published in May 2023 by Thomas & Mercer, and while readers of my previous novels will probably recognise plenty of crossover – there’s mystery and secrets in those other books too – it’s my first foray into detective fiction.

The Shell House Detectives, the opening book in this Cornish coast-set series, flowed pretty easily. I know, that’s an annoying thing to say, I’m sorry. But while there were undoubtedly other parts of the novel that required more work, the plotting was quite straightforward.

Perhaps that was because I spent about two months planning it before getting into the writing. The overall shape of the story was there from the beginning, and largely – give or take the addition of a character or sub-plot or two – it stayed that way.

Embracing the process

The next novel, however, the second in the series – The Harbour Lights Mystery – has proved altogether harder to get to the bottom of. My editor gave it the initial thumbs up based on a couple of paragraphs which effectively set things up by offering an intriguing case for our sleuths, plenty of atmosphere and characters that sounded like they’d be fun to follow. I followed up with a two-pager, which offered more in the way of plot beats, but still didn’t show how it all came together.

You see, at that point, I had no clue; not on the detail anyway. And when it comes to writing a murder mystery, that’s where the best kind of devils reside.

As I write this, I’m working on my second draft of The Harbour Lights Mystery. I can now look back on the first draft with a combination of fondness and relief. I spent about five months on it, hitting plenty of dead ends along the way.

But the eternal student in me was nevertheless fascinated by the process – I don’t think I’d ever heard the cogs whirring in my writing brain quite so loudly. I enjoyed the feeling of industry; the puzzle of it all.

As soon as I’d made the ‘crack the case’ analogy (and fancied myself in a riverside beer garden with Inspector Morse – the TV version, mind, because John Thaw played him as a greater charmer than Dexter’s original) – I leaned into the bafflement of the whole thing. I welcomed the head-scratching, the marker pen scrawls, the wild theories proffered then dismissed.

After all, where’s the story – or indeed the satisfaction – if it all comes too easily for our sleuths? Or indeed us writers.

5 tips to remember when writing a murder mystery

While there’s doubtless joy in the befuddlement, it can always be helpful to have some mantras to guide you. So here are 5 tips for writing a murder mystery:

A murder mystery’s answer (always) lies in character

It’s okay not to know everything when you start writing a murder mystery

Beware the line between duping and misdirecting

Don’t withhold for withholding’s sake

Keep asking questions of your plot – even when you think you’ve nailed it

1. A murder mystery’s answer (always) lies in character

In Louise Penny’s first Chief Inspector Gamache novel, Still Life, she writes:

Crime was deeply human, Gamache knew. The cause and the effect. And the only way he knew to catch a criminal was to connect with the human beings involved.

—Louise Penny, Still Life

It’s very possible to write a first draft of your murder mystery without fully connecting with the human beings in the novel, but it’s hard and unsatisfying work on a lot of different levels.

Let’s talk about one particular aspect of writing a murder mystery: plot. Simply put, plot arises out of characters doing things – and unless you really know those characters, how will you know what they’re likely to do? The deeper you know the people in your novel, the more alive they will feel, the more nuanced they will seem, the more their motivations will be apparent. Plus, the opportunities for them to DO STUFF – good stuff, bad stuff, everything in between – will be just as plentiful as in real life. You’ll also be less likely to find yourself staring at the flashing cursor, thinking ‘what now?’.

While I knew who The Harbour Lights Mystery murderer was from day one, I’m only really getting to ‘know them’ as I work on the second draft.

Several pages of first-person freewriting in my notebook has helped me get to this point: I now know I can return to, and animate, their segments, with better ideas for their behaviour. The same goes for other characters – one of which, my delightfully (ahem) straight-talking husband told me ‘smelt like a red herring from the off’. I couldn’t argue, as they drop away in the first draft, simply because there’s nothing much for them to do.

This time round, I’m working harder – as Inspector Gamache would have it – to connect with my characters as human beings. And more and more possibilities are opening up as a result.

When you’re writing a murder mystery, deepening your characters always pays off. As guest writing coach Mark Billingham wrote in his blog for us:

Give your readers characters they genuinely care about, that have the power to move them, and you will have suspense from page one.

—Mark Billingham

2. It’s okay not to know everything when you start writing a murder mystery

I don’t know about other murder mystery writers, but I felt a pressure to really nail the plotting in advance – even though that’s not how I’ve approached any of my previous novels. I’ve always equated detective fiction with plot (with a capital P), and therefore my reasoning was that plot should lead the process. I’m only realising now the fault in that logic.

In the excellent Howdunit: A Masterclass in Crime Writing by Members of the Detection Club, Golden Age writer J.J. Connington likens the whodunit plotting process to the composition of a chess problem.

In both cases the constructor begins at the end and works backward. The chess expert, having hit upon his checkmate position, has then to devise moves leading up to it, and has to place on the board a pawn here or a piece on some other square, in order to block certain moves which might otherwise be made.

—J.J. Connington

It sounds like an incredibly orderly and considered process, put this way. Perhaps too much so?

Elsewhere in Howdunit, editor Martin Edwards writes:

Anthony Trollope famously damned Wilkie Collins’ fiction with faint praise, saying “The construction is most minute and wonderful. But I can never lose the taste of the construction.”

—Martin Edwards

It’s worth remembering that it all depends on the finished result. That’s why identifying as a ‘plotter’ or a ‘pantser’ is in many ways only helpful if it helps us hold our nerve through the process. As Zadie Smith says in her 10 tips of writing, ‘All that matters is what you leave on the page.’

In my current work-in-progress I knew the beginning, I knew the midpoint, and I knew the ending – more or less. But there were whole swathes of that first draft where I was doing an E.L Doctorow: ‘Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.’ I felt like I was getting it wrong, because I could only ever see perhaps two or three chapters ahead.

But while the fog was unnerving, I did keep my eyes on the road and my hands gripped tight to the wheel. Crucially, I made sure my attention didn’t waver; when I wasn’t writing, I was freewriting in my notebook (headings like ‘What’s going on with Phil?’), flattening out double-page spreads and doing more of those Incident Room boards that probably don’t exist in real life but help show all the elements of the case, and certainly helped a great deal while I was writing this murder mystery.

Looking back, it wasn’t wrong. There is no wrong way to approach the page. Of course, I could now outline my plot as if it were a series of smart chess moves. Only I would know that it wasn’t conceived that way – that there was a little bit of mayhem to go with the murder.

3. Beware the line between duping and misdirecting

Perhaps more so than with any other genre, readers of mystery novels often approach them with their sleeves rolled up, ready to get to work.

It’s not just about crediting the reader’s involvement in the story, and making space for their interpretation, but actively entering into the game together: a game that is, crucially, deemed fair.

In my first draft, my editor suggested that I’d crossed that often fine line between misdirecting the reader and duping them – and she had me bang to rights. I felt instant shame, because this is something I dislike intensely as both a reader and viewer of crime fiction. I’m now busy correcting it in my second draft.

Perhaps being hyper-aware of the reader’s extreme scrutiny creates insecurity when writing a murder mystery – and that ultimately leads to error. In desperately attempting to hold their ‘a-ha!’ moment off until the very last minute, we can cover up too much.

This is where a fresh pair of eyes is most useful, and your trusted early readers come into their own – and why being edited (and open to it!) is so vital. Playing fair with the reader only drives us to raise our game: we need to be clever for the novel to stand up to scrutiny, and for its end to be surprising as well as inevitable.

And that doesn’t happen by accident. Agatha Christie’s artful misdirection was legendary. In an examination of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in the Guardian, Sam Jordison notes the difference between lying and hiding the truth. He offers the example of a particularly effective one-sided telephone call, and how ‘Many similarly elegant sleights of hand allow Christie to prevent us from feeling cheated…’ And that’s the key: no cheating!

4. Don’t withhold for withholding’s sake

In my work-in-progress, I realised I’d been hanging on to a piece of information – something experienced by one of the characters – as I thought it made their upset and unrest mysterious. It might even have suggested they were capable of murder!

Clever me? No, not clever me. But I persisted with this plan while writing most of the first draft of my murder mystery. I ignored the little voice that was saying ‘Not cool, Emylia’, and continued to tip-toe around the fact of that matter. I was writing paragraphs full of vague unease and unplaced frustration, hoping the reader might be suitably intrigued.

Peter Selgin, in the wonderful 179 Ways to Save a Novel, has no time for such antics, terming their effect ‘false suspense’. He writes:

We do not read in order to learn information already known to the characters, but to share in their experiences and to learn, with them, the answers to more interesting questions like: “What will happen next? How will X respond? And what effect(s) will X’s response have on Y?”

—Peter Selgin

Writers who capriciously withhold information are teasing. They do so for the same reason they abuse flashbacks: because they don’t trust their story, or they have no story to tell... Poor writers assume that by being stingy with information they can entice readers to beg for more. Good writers know that the opposite is true: that the more generous they are with information, the more the reader will want to know.

Duly scolded, I’m fixing these mistakes in my next draft. I know full well that it’s far more interesting for readers to engage emotionally with characters and be deeply immersed in their lives, and that there are much more effective ways to create suspense in fiction.

Withholding only results in a feeling of distance, and a distance from feelings. It also puts enormous pressure on those eventual reveals to be really worth the trouble.

I fell into this trap because I was getting the ‘mystery’ aspect of a mystery novel wrong. What’s really mysterious is how people behave in response to a situation. That’s what we’re endlessly fascinated by: how other people live their lives. There’s no intrigue in simply watching the shadowy movements of a restless, tight-lipped cast.

What’s really mysterious is how people behave in response to a situation. That’s what we’re endlessly fascinated by: how other people live their lives. There’s no intrigue in simply watching the shadowy movements of a restless, tight-lipped cast.

—Emylia Hall

Personally, I see these realisations as part of the magic of writing a murder mystery. It’s a process in which we never stop learning and self-interrogating – not in a dispirited, self-flagellating way, but with cheerful ferocity. Because every single novel – no matter how many we’ve written or not written before – is new.

5. Keep asking questions of your plot – even when you think you’ve nailed it

As I said, intricate plots do not happen by accident. In her brilliant Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, Patricia Highsmith wrote:

If the writer can thicken the plot and surprise the reader, the plot is logically improved.

—Patricia Highsmith

Here ‘thickening the plot’ may mean all manner of things, such as:

Extending your cast so you have sufficient suspects

Working on the motivations of said cast

Introducing more complications (those good old Nabokov rocks)

Switching up the murderer

Late in the writing of the first draft of The Shell House Detectives, I realised I was a little short on suspects. I was in the kitchen at the time – Agatha Christie did say ‘The best time for planning a book is while you’re doing the dishes’ – and it was suddenly stunningly obvious that I needed another name up on the board in the Incident Room.

Now I can’t imagine the book without this addition to the cast. They’ve allowed me to bring greater texture to the novel, spin a new sub-plot, and shed light on aspects of another character’s personality.

Clare Mackintosh, in her recent Q&A with us here at The Novelry, described how she documents reader response on a chapter-by-chapter basis from the very beginning – something I intend to do from now on. If I hadn’t added this other player, I think I’d have been underserving the sleuthing reader, not quite giving them enough on which to train their magnifying glass.

As I mentioned in my first tip, I’ve recently thought of a development for one of my The Harbour Lights Mystery characters. It’s not intrinsic to the main plot, but it is, I think interesting – ‘thickening,’ if you will. It makes me more excited about this person, and what they’re bringing to the novel: their insecurities, needs and morality have made them that little bit more real. I’m planting myself in their shoes, wondering what I would do in their situation, and hoping that the reader does just that too.

Everything always comes back to character. Here I’ll quote Peter Selgin again: ‘The first thing to realize when choosing a subject for fiction is this: that, really, you have no choice. You have to write about people.’

And that’s true no matter what genre you’re writing in.

If you’re writing a murder mystery novel and finding it hard, take heart in the fact that – far more often than not – it should be. Keep connecting with the humanity of your characters, keep asking questions of your plot. Stare the hell out of that Incident Room board – and keep the coffees coming. It will all pay off. When you finally get your breakthrough, it’ll end up every bit as satisfying for the reader as it is for you, the writer.

Emylia Hall

Writing Coach at The Novelry

Emylia Hall is the author of four novels. The Book of Summers, a coming-of-age story inspired by childhood holidays, was published by Headline in 2012 and was one of the bestselling debuts of the year. It was a Richard and Judy Book Club pick, and went on to be voted the favourite read of the summer by readers. The first in her new Cornish coast set crime series, The Shell House Detectives, will be published in 2023. Write your novel with writer coaching from Emylia.

June 4, 2022

The Stages of Publishing: After the Book Deal

As a writer, it can be easy to amalgamate all the stages of publishing a novel into one (sometimes distant!) process. But it’s actually much more complex than that. There are lots of steps between a book being bought by an editor and it reaching a reader.

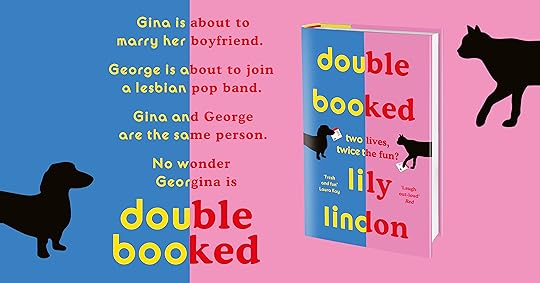

Lily Lindon, Editor at The Novelry, has experienced the publication process from both sides: as a publisher at Penguin Random House and now as a debut author herself (Double Booked is publishing on 9th June). She writes about how to stay sane – and celebratory – during the long road to publication.

The Stages of Publishing: What Writers Don’t Know

Understandably, writers spend so long worrying about getting a book deal but don’t know about all the stages of publishing that come after selling their book.

I want to demystify the process, both as an editor who knows how opaque the publishing world is, but also because I’m experiencing it as a debut author right now. My book is coming out very soon, and I am… all over the place. Frankly, I also need to give myself some advice.

So here’s what I’ve learnt from seeing the stages of publishing a novel from both sides – plus some wisdom from other experienced authors at The Novelry. (Please note that this article is based around traditional trade publishing processes, not self-publishing.)

After the Book Deal Comes a Year of Preparation

Congratulations! You’ve got your book deal! You’ve worked so hard for this. You’ve jumped over an astonishingly competitive amount of hurdles, and finally a whole team of professionals wants to help bring your story to the world in print.

…What on earth happens now?

The First Stages of Publishing Bring More Edits!

You’ve doubtless been through lots of editing and rewriting already. And if you thought your book was finished when your agent sent it to editors… Good one! Now you have a professional editor, you get to edit all over again – with bells on.

Generally, your book will be scheduled to publish around one year after it is acquired. This seems like ages, but trust me, you and your editor will be busy that whole time.

So what can you expect from the professional editorial process? It breaks down into four stages, which will take place over roughly six months. (Though, of course, every book is different.)

The first stage of publishing: developmental edits

The very first step in all the stages of publishing focuses on improving the big picture of your story.

Also referred to as structural edits, this part is generally very collaborative. It’s when you and your editor can talk about any major or foundational changes that could improve your book.

Proposed changes will naturally be different for every book. There are, though, broad questions that most writers tackle at this stage of publishing. Generally, they all aim to determine whether your book fulfils its promise for readers of the genre.

Is the opening the most intriguing it can be?

Is the ending satisfying?

Are there any missing or extraneous scenes?

Are there plot holes to fix?

Are we interested in each of the characters?

And so on.

You can expect two or three ‘rounds’ of structural edits during this stage of publishing. In other words, your editor will give you three rounds of notes, and you’ll send back three updated manuscripts.

This stage of publishing can take anywhere from one to four months.

The second stage of publishing: line edits

Once the bigger picture is all in place, the editor will zoom in for sentence-by-sentence improvements.

Are there words you use too much? Are there metaphors that don’t quite work? Jokes that don’t land? Your editor will make expert suggestions to polish every page until you’re both happy it’s the best it can be.

Structural edits and line edits are not binary. Often you and your editor will naturally look at some sentence-level details while you’re still at the structural stage.

Depending on how detailed you were in your structural edits, you can expect one or two rounds of line edits. Usually, your editor will expect your revisions back in around a month.

The third stage of publishing: copy edits

This third stage of publishing really drills down into the nitty-gritty. It largely revolves around fact-checking and sense-checking your writing.

Remember that fact-checking is not just for non-fiction. Your copy editor should ensure that real things you’ve referenced are accurate – for example, if you have said your characters fly from the UK to the US in twenty minutes, they’ll (hopefully) flag that humans haven’t invented commercial flights that fast yet.

This stage of publishing also involves checking for internal consistency – like whether you have accidentally spelled the name of a magic spell differently. Copy editors will also be formatting your typed manuscript with instructions for the typesetter.

The fourth stage of publishing: proofreading

Proofreaders make sure that all of your is are dotted and ts are crossed, and that there aren’t any accidentally the other way round.

They are reading the typeset manuscript to ensure that in the final printed text, there aren’t any ugly line breaks or errors.

Copy editing and proofreading are specialised and time-consuming stages of publishing that are usually performed by freelancers or separate in-house teams rather than your publishing editor.

Any questions or suggestions they have will be shared with you to approve. You will be expected to read through their notes (typically clicking ‘yes’ to their suggestions on Microsoft Word’s tracked changes) within two or three weeks.

Now (around 3–10 drafts later) your manuscript is finally ready to be printed!

When Will You Get to Hold Your Book?

If you’re on book social media, you will likely see bloggers waving around printed copies months before they’re published, often with a quirky eye-catching cover or some book-related swag.

In the UK these are called ‘proofs’, and in the US they’re known as ARCs (advanced reader copies) or galleys. These are typically printed between the copy-edit and proofreading stages of publishing, so not quite the final text. They are not for resale but are there to get reviews and early interest in the book.

Your book will be finalised and officially printed around 1–2 months prior to publication to allow it to get to bookshops and any early events.

5 Tips for the Editorial Stages of Publishing:

Don’t panic if there are a lot of changes! Remember that the editor bought your book because it’s already great and they saw its potential to be even better.

This can be a moment of real doubt in a lot of writers, because you’re making developments to a manuscript you have already worked on for a long time and it can feel stuck. Remember that your story has to go through lots of skin shedding and metamorphosis to become its best self.

Try not to be overwhelmed if you feel you’re back asking yourself ‘basic’ questions about story. It’s completely natural to go back and forth from bigger picture to more detail. If you can’t see the way out of a story problem, remember that you have an agent and editor to help you now!

Enjoy the creative collaboration. It’s likely your editor will be the only person other than you who reads your book in-depth, multiple times. Revel in their brain. I was so lucky to have brilliant editors to work with on Double Booked, whose thoughtful feedback made it a much, much better story. You get to talk to other people about the actions of characters who you invented! Surreal!

You can read more about the editing process in other blog posts: from the editor’s perspective here and from the writer’s perspective here.

The Visual Stage of Publishing: Your Book Cover

The most exciting – and terrifying – part for a lot of authors is getting to see their book’s cover art for the first time.

Your editor will have briefed your designer – who is sometimes an internal designer, sometimes a freelancer. They will usually give the brief by giving some ‘comparison titles’. That just means books that are aiming for a similar readership to yours. If you’re writing a thriller similar to Lee Child for example, you’d better believe that your cover will be briefed to look ‘like Lee Child in [X] way, but different in [Y] way’.

My book cover, for example, went through about three rounds of concept drafts from the very talented designer until we ended up at what would become the final version.

The process is very variable, but you can expect to have seen the first draft of your cover a couple of months after your deal is made, and the final by six months before publication (so that it can be revealed online and to bookshops etc). As one example: Double Booked’s official ‘cover reveal’ happened in September 2021 for a book publishing in June 2022 (9 months prior).

Remember: you are part of this process too! At any publisher worth their salt, the author must give their approval before the cover is signed off. It’s a conversation, not a conscription. If you have any feedback or ideas, talk to your agent first – they can advise you.

At the same time, remember that you are working with a team of professionals, and that your publisher’s sales and marketing teams will have given their experienced input into the final design. It’s likely they have good reason for advising it looks this way. Everyone has your book’s best interests at heart.

The Final Stage of Publishing: Selling Your Book

The good news if you’re being traditionally published is you have a whole team of professionals working on getting your book to the readers who will love it.

Your sales, publicity, marketing and rights teams will be working behind the scenes throughout all the stages of publishing. It’s only a few months prior to publication that you’ll start to get involved…

Publicity and marketing

Most books do not have a large campaign budget (a lot of books do not have any campaign budget at all). The publishing industry is increasingly weighted towards heavy-hitters of celebrity or brand-name authors. But again, remember that the publisher believes in your book or they wouldn’t have given you a book deal!

Publicity is free promotion: interviews, reviews or articles published through media outlets. Your publicist will collaborate with you on pitch ideas, and on your availability for suitable events.

Events are incredibly oversubscribed, so as ever, don’t feel it’s an indication of your book’s worth if you don’t have an international tour or a launch at Wembley.

The Society of Authors has been campaigning for authors to be paid an attendance fee when they talk at events but note that many events don’t offer a participation fee (though if it’s a significant event or organised by your publisher, then you can expect them to at least cover your travel costs).

Marketing is paid promotion: for example, ads on social media or even billboards.

You’ll hear a lot of talk about ‘audiences’. This just refers to the kind of person who’s likely to be really excited to buy your book.

If you’re writing weighty non-fiction, it’s probably not important for you to make TikToks. If you’re writing a young adult romance novel, you’re unlikely to gain much from a review in the LRB. It would be a waste of everyone’s time, money and energy to try to promote the book to the wrong media.

If a book is going to be any kind of ‘bestseller’ it’s likely to happen in its first few weeks of publication. Typically any publicity and marketing will therefore cluster around publication week/month. That gives the book the best chance of cut-through in the oversaturated market.

Whether your book has a glitzy campaign budget or not, it’s likely that a significant amount of the promotion will come from you as an individual. It’s up to you to decide how much time and money you want to dedicate to promoting your book. Of course, it also depends on your circumstances and skills. Communicate with your agent so that they can help you to create a plan for your independent promotion and/or keep your boundaries.

Want to learn more about publishing?

Our partners at the Madeleine Milburn Literary Agency are running a six-month Mentorship Program, offering six spaces to writers from underrepresented backgrounds. The program features a series of online insight sessions given by editors, agents, international rights, film & TV, as well as bestselling authors. Each mentee will be partnered with an MMLA literary agent mentor and will receive personalised editorial feedback on their manuscript. Each mentee will also receive guaranteed representation. Open internationally, applications close on July 31st – find out more.

7 tips to stay sane through all the stages of publication:

It’s an emotional marathon

Avoid shifting your goalposts

At the end of the day, it’s just a book!

Keep to your own values and priorities

Decide your relationship with reviews

Look after yourself

Use your community

1. It’s an emotional marathon

Understand that life doesn’t just flick a switch to being perfect after you get a book deal. Everyone will go through different highs and lows, about both their own relationship with their writing and tokens of public success. There are many phases.

It’s normal for it to feel very different from one minute to the next. You might have a day where you swing from crying at a mediocre review on Goodreads to someone emailing you to offer television rights. That’s why resilience really is crucial for writers.

2. Avoid shifting your goalposts

It’s simply unfair to expect your story to become Hollywood’s next blockbuster or sell a billion copies in a thousand countries. It’s natural to get caught up in the chain of ambition, to compare yourself to other authors (or, at least, to their curated public façade). It doesn’t make you a bad person if you’re disappointed that something you envisaged for the book’s campaign didn’t happen, but learning to cope with failure is vital.

And remember, it’s no indication of you or your book’s value. Lovely things will happen as a result of your book being out in the world that you cannot predict or expect – don’t do them a disservice by longing for things you can’t control. (And if fame is what you’re after, maybe a career path as an author isn’t the savviest choice…) What would it be like if you felt whatever happens is enough (so Zen)?

3. At the end of the day, it’s just a book!

Yes, it’s also your precious baby, and yes, of course we’re all people who think books are incredibly important. But remember that literally hundreds of books are published every week – and that’s not to mention the millions that already exist.

And, you know, apparently there are also other ways people can spend their time apart from reading (who knew?). It can’t be all about you. And you know what? That’s actually great news. You can chill out, knowing no one else cares as much as you do. Ah, it’s almost as good as the relief of knowing your own cosmic insignificance!

4. Keep to your own values and priorities

The best way to stay in control is to stay true to what’s important to you.

Why is it you want(ed) to be published in the first place? Is it to see your name on the shelves of a bookshop? To have a reader contact you saying they connected with your writing?

It can be powerful to write a note to yourself about what your real ambition is as a writer. Do it now! Then you can return, always, to how you felt before your book deal. Remember how much past-you wanted to be present-you.

5. Decide your relationship with reviews

This is both practical and emotional. You might be someone who wants to know everything – in which case, you can set up Google alerts, ask your team to forward you any updates, and make yourself available to be tagged in reviews on social media.

However, know that no matter how brilliant your book is, you will get bad reviews. You will also, perhaps more offensively, get mediocre or downright incomprehensible ones.

Personally, my skin is way too thin, and my overthinking means that just seeing one randomer’s opinion can send me into a spiral for days – so I try to avoid all reviews unless they come via my editor or a close friend. You can’t please everyone, so my aim is to only know about those I did please.

Ahead of my debut coming out, a novelist friend of mine advised me to adopt a sanguine attitude towards reviews... but for all my best intentions, there were a few Goodreads reviews that really bothered me (The Book of Summers being suggested as a cure for insomnia sticks in the mind, while another reader wanted to, er, punch my hero in the face...!). I remember, at the time, sitting at my laptop feeling properly crushed. Now, several novels and a decade on, I can read back over such things with good humour and pretty much a rhino-hide skin; I’d say that attitude has developed gradually, becoming a little more robust with every novel I’ve published. I’d love to have got there sooner. I now know that you simply can’t please everyone – and why would you wish to anyway? It’s a reader’s prerogative to hold any opinion they want about a book; if they wish to express that opinion in fairly brutal terms, well, that’s their call. The fact is, once you publish a novel, it stops being yours in a lot of ways. That’s all part of the deal. Just don’t let anyone, for even a second, steal your joy or dent your pride in having written the book you wanted to write. However if you’ve the nerve for it, I do recommend checking back in on critical reviews, once you’ve got a bit of emotional distance (weeks, months, years, whatever!), as there might well be food for thought in there. I think the happiest writers are those who cultivate resilience and maintain an open attitude to learning. But in that regard, we’re probably all a work-in-progress, right?

—Emylia Hall

6. Look after yourself

This is making it sound as if publication is one of the worst things that can happen to you, isn’t it? It isn’t! Reach out to other writers, talk to friends, and remember to do non-book-related things too! Like, you know, sleeping.

7. Use your community

You’re part of a community now, not a competition. Lift other writers up. Say hello at events, message when you loved their book, give blurbs generously. Karma is a lovely thing.

If you are excited about reading someone else’s book, you know that pre-ordering is the best gift you can give them (and yourself!).

If you’re looking for somewhere to get a head start… You can order your copy of Double Booked here.

Described by Laura Kay as ‘the queer romcom I’ve been waiting for – a fresh and fun take on finding yourself stuck between two worlds,’ Lily Lindon’s debut novel Double Booked is published by Head of Zeus on June 9th, 2022. Pre-order your copy now.

Lily Lindon

Editor at The Novelry

Before joining The Novelry, Lily Lindon was an editor at Vintage, a division of Penguin Random House, home to authors including Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Ian McEwan, Jeanette Winterson, Haruki Murakami, and Salman Rushdie. Lily is also the author of debut novel Double Booked. Edit your novel with Lily at The Novelry.

May 28, 2022

How to Write a Hook for Your Novel

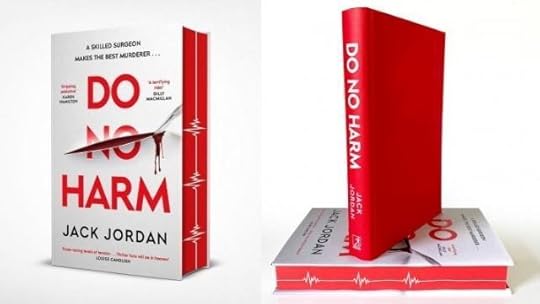

From the desk of Jack Jordan.

If there’s one thing any writer has to nail to ensure success for their novel, it’s writing a hook.

During my years of writing and publishing books, I have learnt that this is the most indispensable component. Characters, setting, book cover... These all play their part. But the one key trait the majority of successful novels have – the thing that helps them stand out – comes at the start of the writing process: it’s writing a great hook.

Great novel hooks explained

You’re probably familiar with the idea of writing a hook. You might have heard the concept referred to as the hook, the pitch or the elevator pitch.

Whatever you call it, the role remains the same: a sentence that sums up the premise of your book in one or two lines and makes the reader want to find out more.

It’s the line you recite when someone asks you what your book is about (and saves you going off on a panicked tangent); it’s the pitch you give to reel in an agent and a publisher, and the line that your publisher’s sales team will use to entice the book buyers for retailers. It’s the line booksellers will use to hand-sell your book to potential readers.

Crucially, it also helps you, the author, to know if you have a strong idea on your hands.

Some people call this the ‘Elevator Pitch’. This imagined scenario is the perfect way to describe the hook: a short yet effective description of your book to pitch to someone during a short elevator ride, to reel them in before they reach their designated floor.

Imagine it: you’ve found yourself in a lift with your dream agent, and you have five floors to pitch your novel to them. It’s just you and her, and she has asked about your book. Having a hook to hand gives you and your book the best chance to shine. It sounds scary, but having your hook tucked away in the back of your mind, one that is short yet powerful in delivery, immediately sets the tone for the conversation – or submission – that follows.

If you say the hook enough times, it’ll become second nature, and you won’t have to think of it much at all. The hook for Do No Harm is ingrained in my mind and can be recited in under ten seconds!

How to write a hook for your novel

‘But how can I possibly sum up my book in a single line or two?’ I hear you ask. To show how I write a hook, I’ll share how I came up with my latest novel, Do No Harm.

The first step to write a hook is finding your idea

The first step is the idea itself. People get book ideas in different ways. Some think of a plot first, while others discover their characters and then create a plot to place them in.

For me, it was the moral dilemma at the heart of Do No Harm that presented itself first. I was fascinated by the thought of a surgeon – whose job is to save lives – being pressured into taking one away. These sorts of high stakes in fiction grab the reader’s interest and stand out a mile in an elevator pitch.

So, I had the plot idea. Now I had to make it real, believable; I needed to discover the main character’s motivation to consider betraying her Hippocratic oath. For something as drastic as killing a patient on the operating table, the motivation must match it in intensity. What could motivate someone to consider something so awful? And better yet, how could I attract readers to not only believe the situation but want the surgeon to get away with it if she chose to go down that path?

I often write about mothers who do anything for their children, and the motivation for my protagonist in Do No Harm quickly became that her child had been abducted. She would only get her son back if she went through with the horrendous deed.

Now I not only had a plan to grip the reader’s attention with the moral dilemma, but I also had the character’s motivation, the reader’s sympathy, and the very question at the heart of the book: which is stronger, a doctor’s oath? Or a mother’s love?

Now I not only had a plan to grip the reader’s attention with the moral dilemma, but I also had the character’s motivation, the reader’s sympathy, and the very question at the heart of the book: which is stronger, a doctor’s oath? Or a mother’s love?

—Jack Jordan

I then had to plan who the patient and antagonist would be – the final pieces in the puzzle. With the high-concept moral dilemma, and the high stakes of the character’s motivation, these two aspects had to match the same intensity. Once I had those, I would be so much closer to writing my hook.

The second step to writing a hook is dissecting your idea

As you can see, writing a hook is astoundingly simple once you’re fleshing out the premise of your novel. You’ve already done the work! All you need to do is break down the key parts of the novel’s concept and feature them in your killer hook:

What the book is about

Who the book is about

And finally:

What is at stake

Example of how to write a hook

Using this formula, the hook for Do No Harm became:

An organised crime ring abducts the child of a leading heart surgeon and gives her an ultimatum: kill a patient on the operating table or never see her son again.

Which is stronger: a doctor’s oath? Or a mother’s vow to protect her child?

—Jack Jordan, Do No Harm

Let’s break this down even further. When writing this hook, I included multiple key bits of information:

the protagonist, her job, and the novel’s setting: leading heart surgeon

the antagonist: organised crime ring

the life-changing event: give[n] an ultimatum

what’s at stake: never see her son again

what must be done to resolve the issue: kill a patient on the operating table

And finally, a question tied to the very premise of the novel – the moral dilemma – to leave the reader thinking: Which is stronger: a doctor’s oath? Or a mother’s vow to protect her child?

In one line, this hook explains who the protagonist is, what they’re up against, and what they must do to survive, followed by a question that the listener is left to answer. Once you think of your hook in this way, you’ll be able to write hooks in your sleep!

Now it’s time for you to write your hook. If you already have one, put it aside for now and see if you can come up with another using this format.

How to write a hook in 5 steps

Just answer these 5 key questions to write a killer hook:

Who is the novel about? What keywords can you use to describe your protagonist? Is she a surgeon? Is he a father? Are they an addict struggling to get clean? What is their primary role or trait in your story?

What is at stake? What will your protagonist lose if they don’t achieve their goal? How can you describe your plot scenario in a way that has the recipient widening their eyes?

What must the protagonist do to achieve their goal?

Who or what is standing in their way?

And finally, what is the reader reading to find out? What lingering question (whether asked directly in the hook or whispering in the background) are you leaving the agent in the elevator with?

Have a play with this – not just with your novel, but with some of your favourite films or books. Practice really does make perfect. Can you write a great hook for your favourite book or film using this format?

Examples of novel hooks

Below, I’ve laid out examples of great novel hooks describing recently published and upcoming books from our lovely tutors (and editors) here at The Novelry:

Summer Fever by Kate Riordan: Married couple Laura and Nick move to Italy to save their marriage, purchasing a villa to host paying guests – but when their first couple arrives from America, it’s clear neither Madison nor Bastian are who they claim to be, and their quickly forged close relationships threaten to unravel the couples at the seams. One villa, two couples, but will either survive the summer?

The Boy Who Grew a Tree by Polly Ho-Yen: Nature-loving Timi, unsettled by the arrival of a new sibling, turns to tending a tree growing in his local library which is set to close. But there is something magical about the tree, and it’s growing fast... Can Timi save the library and his tree, and maybe bring his community closer together along the way?

Double Booked by Lily Lindon: Gina is about to marry her boyfriend. George is about to join a cult lesbian pop band. Gina and George are the same person. No wonder Georgina is Double Booked…

The Oleander Sword by Tasha Suri: A magically gifted priestess and a prophesied empress must work together to destroy a tyrant emperor, for joining forces is the only way to save their kingdom from those who would rather see it burn – even if it threatens to cost them everything they hold dear…

The thought of writing your hook might be slightly daunting, but having it tucked in your back pocket ready to whip out at a second’s notice will make your life so much easier in the long run!

No more scrambling to describe your book. A clear, concise description will reel in agents on submission and make a publisher desperate to read on. Follow these five steps, and you’ll have yourself a killer hook and an audience desperate to find out more.

Do No Harm by Jack Jordan is available in hardback, ebook and audio now. You can get the Waterstones exclusive edition with sprayed edges here.

Jack Jordan

Author Tutor at The Novelry

Jack Jordan is the global number one bestselling author of six thrillers including Do No Harm, Anything for Her and Night by Night – an Amazon No.1 bestseller in the UK, Canada, and Australia. Jack tutors writers tackling crime, psychological thrillers and suspense fiction at The Novelry. Write your novel with Jack at The Novelry.

May 22, 2022

Sophie Kinsella on Motivation and Where to Find It

Writing a book is like having a baby. This is a comparison that’s often made – and having written over thirty books and had five babies, I concur. There’s the same giddy journey of conception, hope, excitement, development, bloody hard work, even harder work, optional cursing… and then delivery! You did it! You’ve forgotten all that hard work as you cradle your manuscript/mental image of The End on your computer screen.

It is at the bloody hard work stage that motivation is required. Every woman in labour has thought, Why am I doing this? This was a huge mistake. Never again. (Or maybe that was just me.) Every writer has reached a stage in the draft where they feel exactly the same way. You’ve forgotten why your plot made sense. Your characters aren’t doing what they’re supposed to. Maybe you have come to despise your main character. Or your idea. Or the whole notion of writing.

So here are a few tips that I have learned over the years, for finding motivation at all the stages of your novel-writing journey.

Conception is the twinkle in an author’s eye. A precious fusion of ideas in your brain that sparks what I always think of as a what if?

This might be a single plot point, a character trait, a setting, or the idea for a new, ground-breaking genre. For me, the buzz of a new idea is the highlight of the process. Ideas are rare. Treasure them. Hopefully, right now, you’re energised by the thought of your brilliant idea and full of motivation. But if at this stage you lose it, maybe it’s because you’re rushing. Maybe you write a page or a chapter, it’s not quite working and you get dispirited. (Been there.)

Step back. Don’t try to force a new idea into anything as substantial as a ‘story’ until you know what you’ve got. Quite often, I sit on an idea for a while, wondering what else it needs before it can be a book. Although it seems counter-intuitive, being patient can be the best way to motivate yourself. Don’t think ‘I need to write this idea’. Instead think ‘I need to mull on this idea’. Check in on it every day and see if you have any new thoughts or perspective. Make notes. They can be totally random. They’re all useful even if it’s just to rule them out.

Don’t think ‘I need to write this idea’. Instead think ‘I need to mull on this idea’.

—Sophie Kinsella

You have an idea but you’re not sure what to do with it? Try going to a bookshop. Wander around, think about the book you would buy as a customer, and try to relate your idea to that.

At this stage, I start planning. Some plan, some don’t. If you’re a natural planner, then don’t be fazed at spending a long time on this stage. Every bit of work you do now may well save you time down the line.

Of course, finding time is the biggest killer. For me, it’s vital to keep the end goal in sight, otherwise it’s just too hard to keep on at it, every single day. When I was writing my first novel, I was a financial journalist. I wrote in the evenings and at weekends, but I also wandered around bookshops practically every lunchtime and stared at book covers, just to remind myself: This is what I’m doing. I want to make one of these. Imagine if I ended up with a book in a shop!

Use your friends and family to motivate you. Chances are, you will have to rearrange your schedule if you want to devote serious time to writing. If you have supportive friends, they won’t mind your absence at the pub/Zumba class and their cheerleading might spur you on. If you have a confidante or sounding board for your ideas, then even better. If you are in a writing group and sharing your work-in-progress with people you trust, then this is going to be huge motivation itself. But this won’t suit everyone. In my experience, the minute you tell anyone a book concept, they instantly have a load of ‘good’ ideas which they will eagerly share with you. This might be helpful or might leave your brain spinning. Ideas are fragile and sometimes they need to grow without scrutiny. Again, this is personal choice.

If you’ve already started and are on chapter 7, hurrah! But…. oh no, here it comes. The wall. The sludge. Whatever you want to call it. It’s the middle of the book, all your initial impetus has gone and you can’t remember how it was going to get from here to the fantastic finale, which you can’t wait to write. It’s easy at this stage to give up. To think that other idea you had was much better. (Hmm. Possibly. Or possibly not.)

For me, the best thing to do at this stage is step away. Try to remember the initial idea, the initial excitement, try to feel the exhilaration, walk around book shops again, and talk to your confidante if you have one. Remember the big arc of your story. Maybe you’ve got bogged down in the detail. Imagine pitching it to someone. What’s it about? Has this changed while you’ve been writing?

Remember the big arc of your story. Maybe you’ve got bogged down in the detail. Imagine pitching it to someone. What’s it about? Has this changed while you’ve been writing?

—Sophie Kinsella

Maybe you have gone wrong and need to retrace your steps back a little. That’s fine. You might need to dump some words and that’s a painful realisation for every author. Just know: we’ve all dumped words and lived to tell the tale. (But save them in a file for repurposing.)

Maybe you need to write your fantastic finale right now. It’s bursting out of you. So do it! Enjoy it! And when you’ve done that, you’ll have a clearer idea where you’re heading. You’re allowed to write this book in any order. And if you don’t know what a character is called, xxx will do for now.

All this time, I hope you’re rewarding yourself along the way. Come on. You’re only human. I can’t even contemplate sitting down to write without the ‘bribe’ of a cup of coffee. Other helpful little treats are chocolate, glass of wine, crisps… and little trades in my mind. I can have this bar of chocolate if I do not log on to the Internet for the next two hours.

The Internet… What do I say? You know. We all know. A quick peek at a useful research site: yes. Twitter… at your own peril.

And then, as you’re getting towards the end, hopefully everything is coming together. Knowing the end is in sight is the most fantastic, motivating feeling – I always end up typing screeds of words per day. Typing The End is even better.

Yes, there will be edits, changes, and the small matter of guiding your precious book through the tricky world of publishing, but that’s for another day. You’ve delivered a draft. Bravo.

Sophie Kinsella

Sponsor of The Sophie Kinsella Scholarship at The Novelry

Sophie Kinsella has sold over 45 million copies of her books in more than 60 countries and been translated into over 40 languages. The author of the bestselling Shopaholic series as well as ten standalone novels, a YA book, and novels written under the name Madeleine Wickham, we are delighted Sophie Kinsella will be joining us for a Live Q&A with our members on June 13th at 6pm UTC to share her experience and talk about her writing craft. Sophie is also the kind sponsor of a fully-funded place on The Octopus Scheme, our scholarship program at The Novelry, with huge thanks.

May 14, 2022

Suspense Writing: 5 Top Tips

Suspense writing is an amorphous and multifacted concept, but Kate Riordan wants to make it straightforward.

Having written five novels – including the Richard and Judy book club pick The Heatwave – Kate is a master of mystery and suspense writing, and she’s sharing her wisdom with us.

Here are Kate’s 5 top tips to create suspense in fiction.

What is suspense writing?

While ‘suspense’ as a genre might mean slightly different things to publishers and readers, for writers hoping to position themselves in this part of the market, it’s worth going back to basics.

Suspense is a state of excitement or anxiety about something that is going to happen very soon, for example about some news that you are waiting to hear.

—Collins Dictionary

The dictionary definition of the word itself is the key to why readers love suspense writing. It’s the uncertainty. God knows why we like it, but we do, at least within the confines of a book – when it’s a safe thrill we can literally hold at arm’s length. But that's if you’re reading it. What if you’re writing suspense?

5 tips for suspense writing

Here are five top tips that have sharpened my suspense writing:

Don't build suspense in a rush

Tell secrets and lies

Suspense writing hinges on setting

Use dramatic irony

End chapters powerfully for maximum suspense

1. Don't build suspense in a rush

This might sound counterintuitive for really impactful suspense writing. But think of a rollercoaster ride: the scariest part is that moment at the top, before they let the brakes off. If you hurtle past this to get to the action, you risk squandering the best bit – the bit when you’ve got them, heart in mouth and full of dread.

As a reader, I love the jangling unease of these moments. You know something bad is coming, but you’re not sure exactly when, or what it will look like – and therein lies suspense writing’s peculiar and tenacious appeal.

Scene after scene of high-octane action is exhausting and ultimately numbing for a reader. But suspense, with its agonisingly drawn-out tension – the literary equivalent of creeping through a pitch-dark house at night, nerves flaring and skin prickling – will always keep ’em coming back for more.

In craft terms, to write suspense you can layer up at chapter level, whole-book level and even in a single image. Rosamund Lupton demonstrates the latter beautifully in her opening to the genuinely un-putdownable Three Hours, about a school siege:

A moment of stillness; as if time itself is waiting, can no longer be measured. Then the subtle press of a fingertip, whorled skin against cool metal, starts it beating again and the bullet moves faster than sound.

—Rosamund Lupton, Three Hours

2. Tell secrets and lies

Suspense fiction is the natural home of unreliable narrators and mic-drop reveals. As Louise Dean points out in The Novelry’s fantastic new Advanced Course, the golden rule of suspense writing is that no one and nothing is quite as it seems. This adds another layer of discomfiture for the reader (it really is a deliciously sadistic business, writing this stuff).

Gone Girl does this with aplomb when (spoiler alert!) Gillian Flynn allows the reader and everyone else in her cast to believe that protagonist Amy Dunne is dead until – ta-da! – we realise Amy has faked it.

My own narrator in The Heatwave, Sylvie, lies by omission to both the reader and her own daughter, with the truth only coming out at the midpoint. Until then, the seasoned reader of suspense writing will know that a secret or three will be lurking, but is compelled to read on in order to discover the truth.

Avoid being too secretive or misleading

A word of warning. If your big reveal or solution to a complex plot comes out of nowhere and is too convenient, it will fall flat on its face.

This is the Deus ex machina problem and sometimes happens when an author has written themselves into a corner. ‘And it was all a terrible dream!’ really won’t wash. Nor will throwing in a random character the reader has no investment in, just to tie up loose ends. A really satisfying reveal will simultaneously surprise and make sense to the reader because the writer has seeded its possibility from the start.

3. Suspense writing hinges on setting

A well-drawn setting can underpin the tense atmosphere a suspense writer is trying to create. I’m always saying in my coaching sessions that setting can do a lot of heavy lifting: why not make the most of it?

Authors of gothic fiction know this only too well, and have been employing a sympathetic backdrop or pathetic fallacy for centuries. Of course you need to be a little bit wary of tropes here, but an isolated place, extremes of temperature and weather in general, plus plenty of darkness and shadows, all have the power to unnerve readers.

An example of successful suspense writing

It’s high time I mentioned Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s suspense classic and a masterwork of atmospheric setting. It opens with the second Mrs de Winter dreaming of Manderley, establishing immediately how integral setting will be to the entire book, and how like a strange and discordant dream the setting actually is.

With the book’s explicit echoes of Jane Eyre, the fire that consumes Manderley by the end feels almost inevitable, the reader carrying the potent dread of it all the way through thanks to Du Maurier’s masterly suspense writing.

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and a chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited. No smoke came from the chimney, and the little lattice windows gaped forlorn.

—Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

4. Use dramatic irony

Dramatic irony is a great tool for suspense writing; the literary equivalent of a panto audience shouting ‘he’s behind you!’ to no avail.

It has been used to great effect in tragedy forever – think of Othello, when the audience is party to Iago’s Machiavellian asides while Othello himself continues to blindly trust.

If you're writing in third person, this is a really handy device to use when your main character is in danger.

Alternatively, a first-person narrator who is themselves a danger (like Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s series) can tease and titillate the reader about what he or she might do next.

He remembered that right after that, he had stolen a loaf of bread from a delicatessen counter and had taken it home and devoured it, feeling that the world owed a loaf of bread to him, and more.

—Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr Ripley

5. End chapters powerfully for maximum suspense

A writer can keep the suspense simmering away by manipulating their chapter endings.

A proper cliffhanger is great, of course, ending as it does in the middle of something dramatic, practically forcing the reader to read on. But it doesn’t have to be as explicit as someone’s fingers being peeled off a cliff-edge, one by one.

In psychological suspense writing, it can be something much more subtle and insidious. A small but crucial detail revealing a new facet to a character the reader thought they knew, for example. This, too, can have your reader thinking, ‘just one more chapter…’

And while we’re on chapters, the way they’re structured and labelled can also ramp up suspense writing. In my latest book, Summer Fever, I begin at the end, in the aftermath of an earthquake which has killed one of the principal characters (of course I don’t reveal who). I titled this prologue ‘Day 14’, and then flashback to ‘Day 1’. This way, the reader is set up to ask the question ‘what the hell happened here?’ from the outset. The idea is that they’ll then tear through the rest of the book to find out…

Kate Riordan

Writing Coach at The Novelry

Kate Riordan is the author of six books; five novels and short stories, including The Sunday Times bestseller The Girl in the Photograph, Top Ten Red Magazine choice of the year The Stranger, and The Heatwave, a must-read Richard and Judy Book Club Thriller pick.

5 Ways to Create Suspense in Fiction

From the desk of Kate Riordan.

While ‘suspense’ as a genre might mean slightly different things to publishers and readers, for writers hoping to position themselves in this part of the market, it’s worth going back to basics.

Suspense is a state of excitement or anxiety about something that is going to happen very soon, for example about some news that you are waiting to hear.

—Collins Dictionary

The dictionary definition of the word itself is the key to why readers love suspense. It’s the uncertainty. God knows why we like it, but we do, at least within the confines of a book – when it’s a safe thrill we can literally hold at arm’s length. But that's if you’re reading it. What if you’re writing it?

Here are five ways to inject a shot of suspense into your novel:

Don't rush it.

Tell secrets and lies.

Create atmosphere through setting.

Use dramatic irony.

Think about your chapter endings.

1. Don’t rush it.

This might sound counterintuitive but think of a rollercoaster ride: the scariest part is that suspended moment at the top, before they let the brakes off. If you hurtle past this to get to the action, you risk squandering the best bit – the bit when you’ve got them, heart in mouth and full of dread.

As a reader, I love the jangling unease of these moments. You know something bad is coming, but you’re not sure exactly when, or what it will look like – and therein lies the suspense novel’s peculiar and tenacious appeal. While scene after scene of high-octane action is exhausting and ultimately numbing for a reader, suspense, with its agonisingly drawn-out tension – the literary equivalent of creeping through a pitch-dark house at night, nerves flaring and skin prickling – will always keep ’em coming back for more.

In craft terms, you can layer up the suspense at chapter level, whole-book level and even in a single image. Rosamund Lupton demonstrates the latter beautifully in her opening to the genuinely un-putdownable Three Hours, about a school siege:

A moment of stillness; as if time itself is waiting, can no longer be measured. Then the subtle press of a fingertip, whorled skin against cool metal, starts it beating again and the bullet moves faster than sound.

—Rosamund Lupton, Three Hours

2. Tell secrets and lies.

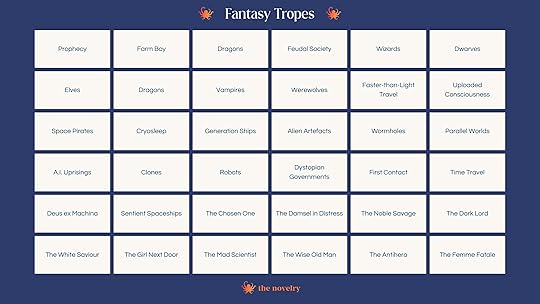

Suspense fiction is the natural home of unreliable narrators and mic-drop reveals. As Louise Dean points out in The Novelry’s fantastic new The Second Novel Course, the golden rule of writing in this genre is that no one and nothing is quite as it seems. This adds another layer of discomfiture for the reader (it really is a deliciously sadistic business, writing this stuff).

Gone Girl does this with aplomb when (spoiler alert!) Gillian Flynn allows the reader and everyone else in her cast to believe that protagonist Amy Dunne is dead until – ta-da! – we realise Amy has faked it.

My own narrator in The Heatwave, Sylvie, lies by omission to both the reader and her own daughter, with the truth only coming out at the midpoint. Until then, the seasoned reader of the genre will know that a secret or three will be lurking, but is compelled to read on in order to discover the truth.

A word of warning, though. If your big reveal or solution to a complex plot comes out of nowhere and is too convenient, it will fall flat on its face. This is the Deus ex machina problem and sometimes happens when an author has written themselves into a corner. ‘And it was all a terrible dream!’ really won’t wash. Nor will throwing in a random character the reader has no investment in, just to tie up loose ends. A really satisfying reveal will simultaneously surprise and make complete sense to the reader because the writer has seeded in its possibility from the start.

3. Create atmosphere through setting.

A well-drawn setting can underpin the tense atmosphere a suspense writer is trying to create. As I’m always saying in my tutor sessions, setting can do so much heavy lifting for the writer, so why not make the most of it?

Authors of gothic fiction know this only too well, and have been employing a sympathetic backdrop or pathetic fallacy (giving human characteristics to inanimate things) for centuries. Of course you need to be a little bit wary of tropes here (see Craig Leyenaar's excellent blog on this), but there’s no doubt that an isolated place, extremes of temperature and weather in general, plus plenty of darkness and shadows all still have the power to unnerve readers.

It’s high time I mentioned Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s suspense classic and a masterwork of atmospheric setting. It opens with the second Mrs de Winter dreaming of Manderley, establishing immediately how integral setting will be to the entire book, and how like a strange and discordant dream the setting actually is. With the book’s explicit echoes of Jane Eyre, the fire that consumes Manderley by the end feels almost inevitable, the reader carrying the potent dread of it all the way through.

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and a chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited. No smoke came from the chimney, and the little lattice windows gaped forlorn.

—Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

4. Use dramatic irony.

This is when the writer allows the reader to know more than the main character does; the literary equivalent of a panto audience shouting ‘he’s behind you!’ to no avail. It has been used to great effect in tragedy forever – think of Othello, when the audience is party to Iago’s Machiavellian asides while Othello himself continues to blindly trust.

If you're writing in third person, this is a really handy device to use when your main character is in danger.

Alternatively, a first-person narrator who is themselves a danger (like Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s series) can tease and titillate the reader about what he or she might do next.

He remembered that right after that, he had stolen a loaf of bread from a delicatessen counter and had taken it home and devoured it, feeling that the world owed a loaf of bread to him, and more.

—Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr Ripley

5. Think about your chapter endings.

A writer can keep the suspense simmering away nicely by manipulating their chapter endings.

A proper cliffhanger is great, of course, ending as it does in the middle of something dramatic, practically forcing the reader to read on. But it doesn’t have to be as explicit as someone’s fingers being peeled off a cliff-edge, one by one.

In psychological suspense it can be something much more subtle and insidious. A small but crucial detail revealing a new facet to a character the reader thought they knew will also have them thinking, ‘just one more chapter…’

And while we’re on chapters, the way they’re structured and labelled can also take up the suspense a few notches. In my latest book, Summer Fever, I begin at the end, in the aftermath of an earthquake which has killed one of the principal characters (of course I don’t reveal who). I titled this prologue ‘Day 14’, and then flashback to ‘Day 1’. This way, the reader is set up to ask the question ‘what the hell happened here?’ from the outset. The idea is that they’ll then tear through the rest of the book to find out…

Kate Riordan’s new suspense novel Summer Fever is out now from Penguin Michael Joseph. Described as ‘a sexy, sultry, immersive read’ by bestselling author Harriet Tyce and ‘intimate, intense and utterly addictive’ by Sunday Times bestseller Emma Stonex, this is the perfect book to read on holiday.

Kate Riordan

Author Tutor at The Novelry

Kate Riordan is the author of five books, including the Sunday Times bestseller The Girl in the Photograph, The Shadow, and Richard and Judy Book Club pick The Heatwave. Kate tutors writers tackling mystery, suspense and historical fiction at The Novelry.

May 7, 2022

Writing Your Next Novel

Today we're delighted to launch a new course at The Novelry: The Second Novel Course. Our Founder Louise Dean looks back on how she wrote her second novel and beyond; how ideas sometimes come fully formed, but only rarely – and explains how to write your best novel yet.

From the desk of Louise Dean.

How do our novels happen?

By miracle?

Sometimes our best-laid writing plans are tossed aside in favour of a sudden insight and burst of feeling. We stumble across the new green leaves of a story, and all that remains – as with turnips – is to pull, pull, very hard to unearth it whole. (Others come and pull too: literary agents, publishers and sundry creative writing course tutors!)

But in truth, novels come to me this way quite rarely.

By force?

My normal effort is to configure a character, contrive a concept, then shove it this way and that to make it more ‘viable’ or appealing – and in so doing, I fall out of love with it. It’s as if, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, I refuse to write any story that would have me.

I have spent years forcing my writing trotters into Cinderella-style slippers. It hasn’t worked. So, here’s a fool-proof test to establish whether a story that looks good on paper is a go-er. Question: have you written it yet? If the answer is no, it’s not.

So back to the miraculous…

It’s as if, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, I refuse to write any story that would have me.

— Louise Dean

The divine write.

Behind every miracle is a long road. It takes one hell of a trek to meet God on the mountaintop. Behind every mystical experience is a coalition of circumstances, a conspiracy of coincidences and a craven longing.

Here is a timeline of one immaculate story conception.

Friday morning: I confessed to my friends at The Novelry that I was yearning to write but was revolted by the vast amount of material I had produced in the last years, so much of it and yet nothing was ‘sticking’. No magic.

Saturday morning: with begrudging generosity (surely there’s a German word for that?) I set off to do my duty to visit a relative. And when I got there? Well, I enjoyed myself so much. My aunt’s home is a time capsule, a museum of our past. I felt warm and at ease, and scanned the many versions of me coming together in the photos around the room, on dressers and mantelpieces, even a hostess trolley: as a child, with a fierce and confrontational glare, and in later photos, I saw how that bold look had morphed into a sickly bland amenable smile. Our hug goodbye was a moment of love and truth that moved me. I was, literally, touched. (Nice, huh?)

On the drive home, I looked at people differently. I peered at their passing faces. My phone rang and it was the son of a former writer of ours, who sadly passed away earlier this year. He was calling to say how much The Novelry had meant to his father in his last months, and we shared some memories and laughed about a ‘ballad’ they had found in his belongings that his dad has penned in honour of The Novelry team. I told him his father was a talented writer and we thought it more than likely he would have been published. We closed the conversation by speaking about the son’s own writing, and how he had determined to get on with it. Any which way, published or not, his father had left behind much more than a sea shanty and the family were marvelling at his writing – and how much of himself he had left behind.

Then a car passed me with a man and a woman in the front seat and something in the turn of her face, how close she was to the driver – too close – took me hurtling back through time, more than 35 years to a moment long-forgotten in which I admired someone that way and seemed – corny, I know – to bloom in his presence. He was a wonderful person, and though this may seem contrary in these more circumspect times, we were friends, no more than that. But we were. It all came back to me, everything. I thought: I am coming back to get you. I thought of him saying: get me out of here. As I neared home, I began to think – what if. And I began to imagine the two people in other circumstances and saw anew what they might have to offer each other. As the car pulled on to the driveway, I had a story.

The story came to me in minutes, it seemed. But it didn’t, did it? It was the coalition of circumstances, coincidences and craven longing.

My second novel came to me mystically, too. I was dawdling around London and decided to pay homage to Grahame Greene by going to find his former home on Clapham Common. I stood outside to pay my respects (I have also left a business card at Dostoyevsky’s grave in St Petersburg, so I’m not afraid of a touch of whimsy). I waited there a while and departed without inspiration to the Underground. On the platform for the Northern Line, I watched the trains arrive and depart, over and over, as I sat on a bench to write down the idea for what would become my second novel, This Human Season.

In my fifty-two years of life and twenty-five years of writing, these moments have happened to me too rarely. Today in 2022 on the Cranbrook town bypass, and at Clapham North Station in 2003. Perhaps a sundry few times in-between.

If novels were Tube trains, I’d be waiting 20 years for the next.

The machine and the magic.

I think you have to be humbled and softened, and have done some spadework, to come up with a story you’re going to write to the end. The writer’s mind has to be the most fertile of grounds, turned over a few times.

The tilling of the ground for This Human Season happened by writing hard and professionally (at last) with my debut novel Becoming Strangers which I drafted and re-drafted, experiencing for the first time the revision process to meet publishing standards.

I think you have to be humbled and softened and have done some spadework to come up with a story you’re going to write to the end. The writer’s mind has to be the most fertile of grounds, turned over a few times.

— Louise Dean

The personal factor.

The creation of human life doesn’t happen with a single flick of a switch. There are hundreds of decisions, actions and reactions – some in our hands, some out of our hands – that appear as stop/go tickets in the process of creation.

But at some point, as the mother or host, you commit to the process, even if it’s in the moment of the push. When you write, you push daily, right? Why? What’s the difference between a second of insight in your driveway and a finished draft?

I have plenty of ideas for novels, all stashed as duds in folders. But it takes something special for me to see the damn thing through. After you’ve had one child you know what’s in store, so you’ve only yourself to blame!

With This Human Season, it could be summed up simply. For me, it was all about a scene in a prison yard in which a prison officer says to a young man who is the same age as his son that it’s not personal. The young man replies that everything is personal. Indeed, in Northern Ireland, the political is the personal and vice versa. But it was that moment that I was writing for and towards. It meant something to me. Everything is personal.

Yes, one can have a terrific main character in mind for a novel. But for me, it’s not enough. Yes, one can give them a terrible problem or a clever concept. But for me, it’s not enough. Yes, one can long to be in the place of the setting. But for me, it’s not enough. Yes, you can have a point of view or a theme on what’s wrong in the world. But for me, it’s not enough.

Know yourself.

You need to know yourself and know what that personal factor is for you.

For me, it will be an exchange of love, not the romantic kind, a moment in which human beings see themselves as alike, in which there is both euphoria and sorrow. Time, for authors, is the evil; time robs us of what we love more surely than any enemy. So every joy comes with its attendant loss. The matter of this greater love, this wider love, the possibilities of finding likeness is probably the personal factor for me that drives my writing, and it will be that and that alone that makes me see a novel through. Nothing else.

But we are all different, and we write for different reasons.