Amy Rae Durreson's Blog, page 7

December 23, 2015

The Ghosts of Old Roads

So, for a change of pace, let me take a break from talking about Resistance (which is out next Tuesday–did I mention that? Did I mention it enough? Tuesday! Meep) and instead tell you of murder most foul, of vanishing roads and bizarre Edwardian spectacle.

Because today, for the first time in weeks, the sun shone and I went a-rambling, out of Haslemere and up to Hindhead Common and the Devil’s Punchbowl.

And a very nice day for walking it was too.

I had no set route in mind, so once I reached the edge of Polecat Valley, I idly picked up one of the trails recommended on the board in the little National Trust car park. It turned out to be a good choice as it led me along the ridge towards the Punchbowl.

This may not look like much, but the first time I walked around the top of the Punchbowl, it would have been impossible to take this picture. This used to be the A3, the main trunk road from London to Portsmouth. Always busy and over-capacity, it was most narrow and dangerous stretch of the road. In 2011, a tunnel was opened under these hills and the road given to the National Trust, who have been managing its return to nature ever since.

You can see a little more of the scar of the old road from here.

And here is the bottom of the Punchbowl. I was conscious of the time and the light today, so I didn’t climb down into it (there’s a youth hostel down there somewhere and a maze of footpaths). The Punchbowl is a deep natural depression, probably formed by springs under the local sandstone weakening it until it collapsed. Or, if you prefer local legends, the Devil was so enraged by the number of churches being built in Sussex, to the south of here, that he started digging a channel to the sea in order to flood the Weald. He was making good progress, until a cock crowed and he leapt into Surrey, clearly his true home, creating this dent with the force of his landing. Other stories involve Thor and the Devil having a mudslinging fight, or giants. There’s even one that claims the scooped up earth landed in the channel and formed the Isle of Wight, although this one was clearly concocted by someone who has no idea how large the Isle of Wight actually is.

The A3 wasn’t the first road to run around the top of the Punchbowl. This trail follows the route of the old Portsmouth road, which was relocated further down the slope in the 1830s to become the A3. Now neither are roads at all. This particular stretch of the old turnpike road was the scene of a brutal murder in September 1786. A sailor, on his way from London to Portsmouth, had been drinking in the inn in Thursley, a few miles to the north. He fell into company with some fellow travellers, brought them drinks and paid for their meal, and then they all set off together to brave this stretch of road. This stretch was notorious for highwaymen, and it was a foolish man who travelled it alone, but the unknown sailor had made a poor choice of companions. Near to the highest point of the road, they murdered him: the local newspaper of the time tells us they ‘nearly severed his head from his body, stripped him quite naked, and threw him into a valley.’

A memorial stone still stands by the road, marking the death. On its back, a warning reads ‘curseth be the Man who injureth or removeth this Stone.’

The front reads:

ERECTED

In detestation of a barbarous Murder

Committed here on an unknown Sailor

On Sep, 24th 1786

By Edwd. Lonegon, Mich. Casey & Jas. Marshall

Who were all taken the same day

And hung in Chains near this place

Whoso sheddeth Man’s Blood by Man shall his

Blood be shed. Gen Chap 9 Ver 6

But the story’s connection to the Punchbowl doesn’t end there. This is the rather idyllic view from Gibbet Hill, the actual highest point. At 272m above sea level, it is the second highest hill in Surrey. I could see Guildford, 10 miles away, today and on a clear day you can supposedly see the top of the London skyline. Unfortunately, as the name suggests, it isn’t the views that made it famous. The three murderers were swiftly caught and sentenced to death. They were hung in chains from a 9m (30ft) gibbet on the hilltop very near the place their victim had died. In 1790, Gilbert White mentions that a terrible storm had knocked one of the bodies down–they were still there. Turner created a very Gothic mezzotint of Hind Head in 1808, complete with gallows. In those days, the land would have been primarily heath, not wooded, and gallows would have been visible from the valleys on every side.

The gibbet is long gone, but by the mid-nineteenth century, the hill top had a reputation for being haunted. In 1851, a local landowner addressed this superstition by erecting this granite cross on the site of the gallows. I don’t know how successful his ploy was at the time, but these days the cross and viewpoint are mostly visited by people walking along from the National Trust cafe half a mile away.

I then headed downhill again, in search of the next historical highlight. The way was somewhat tricky in places. The local rock, Greensand, drains excess water away pretty fast (which is why I was here today and not tackling a walk on chalk) but mulch is mulch, and it’s rained a lot over the last few weeks. I did my fair share of squelching along paths today.

This is, or once was, the Temple of the Four Winds (not to be confused with the Temple of the Winds, which is on the next ridge south). It was once a rather elaborate hunting lodge, built in 1910 by the landowner, Viscount Pirrie, the shipbuilder most famous today for applying the word ‘unsinkable’ to the Titanic. Pirrie bought the land in 1909 when it became available due to the death of its previous owner, Whitaker Wright, in 1904. Wright was an interesting character, one who I can’t describe properly in an already lengthy post, but suffice to say he was so successful a swindler that he could afford to build a smoking room under a lake in his Surrey estate and race his yacht against the Kaiser (and win). He was eventually caught out and brought to trial, but committed suicide immediately after his conviction. The break up of his Surrey estate after Wright’s death enabled local people to buy much of Hindhead Common and donate it to the then nascent National Trust, who still manage the land today.

These sweet chestnuts on the right have been coppiced in the last few years and are now springing back. Their wood is sold locally to be used for fence posts and in other rural industries, including repairs to listed buildings where imported materials are vetoed.

I have no idea if this lake has a name, but it was pretty, so I stood in the mud and took a picture of it ;)

Walking through the holly woods in the final stretch of the walk. At the end of this path, I turned back uphill to the ridge and from there made my way back to the station.

This little chap was just opposite the end of the trail, completely unperturbed by the various hikers passing him by.

And that was my Christmas Eve Eve. I hope you all enjoyed yours as much as I did :)

December 22, 2015

Meet the resistance: Raif

Those of you who have read Reawakening will have met this family before. By the start of that book, young Raif is a fully fledged freedom fighter, but I wanted to show how he reached that point and how his family ended up living in exile. So here is a very young Raif, learning about courage.

Midwinter, Taila, 1012 (eleven years before Tarnamell’s rising)

Raif missed his mother.

He knew there was nothing he could do to get her back. He was eight, not a baby like Zeki, and he understood that she was dead. He wasn’t going to lie there and cry because she wasn’t coming back, not least because his father had told him that the Bright Lord smiled on brave boys.

But he still missed her. It hurt, right under his heart, and lying here in the dark, he could feel his eyes growing hot, despite his best efforts. He wanted her to walk into his room from the dimly lit hall, to lean over him with her uncovered hair falling to brush his pillows, and to tell him she was still there. He wanted her to know that he was being brave. It wasn’t enough to prove his courage to his father, who couldn’t say anything more than that tears could not help and Raif must stop talking about her. His father couldn’t even talk about her at all, not without his voice cracking, and Raif didn’t think that was fair to anyone, especially not him.

Raif clenched his fists into his pillow and closed his eyes, but it was no use. His face was wet, and he couldn’t sleep.

Quietly, moving carefully so he didn’t wake Zeki in his cot, he climbed out of bed and tiptoed across the room, past his parents’ bed—his father’s bed now—to the big wardrobe. He eased the door open, hoping his father would not come upstairs to catch him (because he had, just last week, and he had looked like someone had struck him and then he had clutched Raif tightly, his breathing rough and hoarse).

Inside the wardrobe, his mother’s clothes still hung quietly, rustling silk dresses and trousers, tunics gleaming with embroidery, thin veils and head scarves made from gleaming strips of colour.

His mother had been the most beautiful woman in the world. Even the shah had said so, and all the poets of the court, but it had been Raif’s father who wrote the loveliest words about her and so won her heart. She had told Raif the story of it once, cradling him in her arms and laughing about the foolishness of poets, who had competed for her favour with elaborate verses.

“And Father’s were best?” Raif had asked, a little skeptical. He knew his father wrote, but he had rarely heard the words. In his home, his father was a quiet man, one who bowed contentedly to his wife’s will.

“He did,” Mother had confirmed, before she smiled softly. “But that wasn’t why I loved him best.”

She had been wearing pink that day, and Raif could just see a glimmer of the same colour now in the dim light. He reached up carefully, unhooking the long folds of the scarf and brought it close to his face.

The silk still smelled of roses, the perfume his mother had always worn. Raif buried his face in it, clutching it closely.

Then, above him, the roof creaked heavily.

Raif froze. Someone was up there.

The Savattin didn’t come over the roofs, he thought, his heart beating faster. They came by road, openly. When Ganime and Tamay had not come to school, Raif had walked past their house on the way home and seen how the gates were wrenched from their hinges. His teacher had been taken from the front of the classroom by men in red head scarves (and then the girls had been sent home and there had been a new teacher. When Raif had told his father what the new man taught, his father had refused to let him go back to school, and now Raif didn’t know who else had vanished from his classroom).

Another creak, and Raif knew he had to act. He must be brave. The Dual God never sent anyone a test they couldn’t meet, so Raif would have to be strong enough for this one, whatever was happening.

He stole carefully downstairs to his father’s study, and only realised halfway down that he was still clutching his mother’s scarf. He tucked it inside his kameez and hurried to the study door. His father was bowed over the desk, not writing but merely staring at his page, his hands over his eyes.

“There’s someone on the roof,” Raif said.

His father jumped and then leapt to his feet. “Are you sure?”

“I heard them.”

His father went a little grey, but his hand was steady on Raif’s shoulder as he propelled him upstairs. Raif had to scramble to keep up and was surprised when his father went into the bedroom rather than straight to the roof door. Father leaned over the cot and picked Zeki up, tucking the blankets around him before he handed him to Raif. “Can you carry him?”

“Yes,” Raif said, with more certainty than he felt. Zeki was two now, and heavy, but Raif thought he could manage.

“Go downstairs. Wait by the door. If you hear me call out, take your brother and run.”

Raif looked up at his father, startled. Then, feeling worse than he had when he had just been longing for his mother, he did as he was told.

He stood by the door, clutching Zeki tight. His brother was fast asleep, snuffling into his blanket, and Raif willed him to stay that way. When he was awake, Zeki liked to kick and throw tantrums, and Raif needed to listen.

He heard the roof door open, his father’s low exclamation of surprise, and then a soft murmur of conversation.

His father did not shout anything, though. Raif stared at the stairs, so tense his toes hurt, and waited.

Then his father came back downstairs, escorting a strange man. He looked like one of the homeless and hungry that filled the streets of Taila these days, but he walked tall.

“My sons,” his father said, squeezing Raif’s shoulder in reassurance. “Raif, this is Iskandir. He’s a friend, of sorts.”

Iskandir laughed, though that had sounded rude to Raif, and reached down to take Zeki. His father didn’t say anything, so Raif allowed that, though he was still suspicious. What kind of man came creeping over the roof in the night?

His father turned back to Iskandir. “Whatever you want, I can’t help you. I admire what you’re doing, but my children have already lost their mother. I can’t risk writing anything that might—”

“I’m not here to ask for anything,” Iskandir said. “Namik, I’m sorry. They’re coming for you. Tonight.”

Father’s hand tightened on Raif’s shoulder, enough that it hurt, and he reached for the wall with his other hand. “You’re sure?”

“Certain. I had firm confirmation half an hour ago. They usually wait until a couple of hours after curfew—they don’t care for witnesses—but they may be here sooner. We need to go.”

“Where?” Father whispered. Raif looked up at him, worried. “This is my home. This is Suheyla’s home.”

Iskandir’s voice was gentle. “Is it worth dying for? Risking your sons? You may stay if you wish, Namik, but we can get you over the border, even in this season. Taila has already lost her nightingale. Do not let her poet die too.”

“I…” Father looked around, but then stood up, swallowing hard. “They say God never sends us a test we cannot meet. Will it be hard, crossing the border?”

“Yes,” Iskandir said, his tone still soft, “but I will be with you.”

“Then it must be done,” Father said and looked around him again. “I don’t know what to take, what to…I should put the fire out.”

“Leave it. Take as little as you can. If it isn’t obvious you’ve run, it may buy us an hour or two.”

“They’ll destroy everything, won’t they? My books. Her books, her surgery, her tools…”

“Books and tools can be replaced,” Iskandir said. “Your sons cannot.”

“Yes,” Father said. “Yes, of course. Have we time to pack some clothes for them? Food?”

“As long as we’re quick.” Iskandir looked down at Raif. “You can help, can’t you?”

Raif swallowed hard. He was still scared, and he didn’t want to run away, but he didn’t want to vanish in the night either, like Ganime and Tamay. “Tell me what to do, sir. I can be brave.”

“Ah,” Iskandir said and his smile was surprisingly cheerful. “The Bright Lord loves this one. Show me where you and your brother keep your clothes, young Raif, and we’ll leave your father to fill his bag. Just one, Namik. We’ll have to travel light.”

It wasn’t until much later, after they’d left not just his house but his city, that Raif realised he still had hid mother’s scarf tucked inside his kameez. He buried his face in it, breathing in the scent of home, and promised himself that one day, when he was old and strong enough to fight the Savattin, he would return.

And he would show them what it meant to be brave.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 20, 2015

Meet the resistance: Akel and Ela

As Resistance creeps nearer and nearer to its release, I thought it would be a good time to introduce some members of the Tiallatai resistance, the Dark God’s Children, who fought against the Shadow and its followers. Here, to begin, is Akel and his wife Ela, and the story of how they joined the resistance…

© Mathes | Dreamstime.com – Courtyard Of A Traditional House In Yazd Photo

Spring, 1013, Taila (eleven years before Tarnamell’s rising)

Ela met him at the door, pushing past him to press her back against its polished wood. She looked like he felt, her face hollow and her eyes blank with grief, but she put out her hands, holding him away.

“Let me go,” Akel said, and was amazed at how steady his voice sounded.

“Where?” Ela gasped. Her voice was husky, thick with unshed tears.

“I’m going to join the Savattin army,” Akel said and saw her recoil. He couldn’t bring himself to care, not about her pain, or the consequences, or anything except the cold, numb need for vengeance. “And once I’m there, and they’re off guard, I’ll find my way to the highest ranked general I can reach and I’ll cut his throat.” A dim thought occurred to him, reminding him that there were no simple endings in this life, no clean deaths. “They’ll kill me, of course, but they may come here afterwards. You should go to your brother and then get out of the country. I hear the Alagard Desert is welcoming refugees.”

“No,” she said, her lips barely moving.

“It’s for the best,” Akel said gently and grasped her elbows to move her out of the way.

“No,” she said again, and suddenly there was fire in her eyes again. She jammed her thin shoulders against the door, refusing to be moved. “I won’t lose you too.”

She was too thin, wrecked by grief, her hair and face uncovered in the privacy of their home, but he had never seen anyone so strong. “Ela, please.”

She squared her shoulders and looked up, suddenly resolute. “I won’t allow you to kill yourself.”

“Well, I must do something,” he explained, trying to be reasonable. “I won’t fail this test.”

She was as irreligious as he was, or had been, until the Savattin came rising to tear their world apart. Ela had attended temple because it was proper, eschewed her veil in all but the most conservative company, and laughed with him when priests and peasants claimed to have come face-to-face with the Dual God. Her faith had changed, in the last year, turning bitter, and he had heard her whisper to the Dark God at nights, praying for mercy or revenge, or some measure of both. Still, it surprised him when she said,

“This isn’t your test, Akel. Even the Dark God wouldn’t send this.”

“I have to—”

She knotted her hands in his long sleeves, her knuckles pressing into his forearms, and took a shuddering breath. “No. This isn’t your path to God. There is something else—something I… I have a better idea. One which will hurt them more.”

Akel looked at her, his fierce, brilliant wife, and then took a slow step back. “I’m listening.”

And Ela explained, in a rush of furious whispers.

Two days later, Akel went out into the city of Taila. The capital had changed much in the last year. It was no longer the elegant city he had loved, full of poets and philosophers. The philosophers were dead, fled to other lands, or vanished with nothing but rumours to explain where they gone: there was a resistance, men murmured softly in the teashops, the Dark God’s children fighting against the cruelty of the Savattin.

As for the poets, they too had vanished as if no one had ever sung of god and sunlight on the steps of the temples. Even Namik Shan had gone, Akel had heard, fleeing with his children in the night, the nightingale’s own poet silenced by oppression.

Akel wished he had done the same while it was still possible, but here he was, and it was still his city. He would fight for it. What else did he have to lose?

The streets seemed oddly empty. It was not just the scars of fighting left in the plastered walls, or the boarded up fronts of the temples, painted with the clenched scarlet fist of the Savattin’s symbol. No, Akel realised with a slow sick fury, it was the women.

Or rather the lack of them. No women walked the streets of Taila, not even in the sweeping, overwhelming scarf and veil the Savattin had decreed. Ela had laughed herself giddy the first time she saw a woman wearing it, proceeding slowly down the street like a mobile tent. Now a woman could not leave her house without it.

Or at all, it seemed today. How much worse had it got since Akel last ventured into the city? What new madness was this? Did this filthy barbarians have no sense at all? How could they think it was reasonable to confine half the world behind walls? True enough, men and women followed different roads to God, but they were roads all the same, and meant to be followed.

Akel hesitated on the corner, and put God out of his mind. He had to learn to think like one of them, to ignore his own instincts to follow their savagery instead.

God help him.

The recruiting station was in the old city square, and there was a queue. Akel couldn’t imagine why, not until he looked at the boys lined up (for boys they were, for the most part), and realised that they looked hungry.

Rage washed over him again, and he fought it down, fixing a sneer on his face, endeavouring to look bored by the whole process. He was a Yalman, after all, descendent of generations of ministers and generals. They would expect him to consider himself better than this riff-raff. In another time, he probably would have sneered at them, but all he could see now was what these Savattin bastards had brought his people to.

Once he was inside, things suddenly moved more swiftly. His name, his history, his experience—they all still meant something. He lied, fluently and intently, creating a version of his own life that was skewed to suit his purpose. He was no longer a loyal minister of the shah, a man of culture and learning, but one dissatisfied with the inefficacy of the last government, scornful of the shah’s incompetence (that one was no effort, though the man had not deserved to have his head mounted on his own gates, useless as he was), eager to reform the lax morals of the city. It was a risk, presenting himself half as sympathiser and half as opportune cynic, but he gambled on the fact that they likely had few good administrators.

When he did come face to face with the bastard who had led the siege on Taila, he nearly forgot Ela’s plan and stabbed the general anyway.

But no. He wanted to bring them all down for good, not just rid the world of one ignorant killer.

He left the recruiting station with a commission, suddenly an officer in an army he hated, and walked home with his gut knotted around shame and triumph.

When he got home, Ela was entertaining a guest in the garden. She was the picture of a proper Taila hostess, robed in silks, her hair covered and the finest of gossamer veils floating over her lower face, but her eyes were bright with the need for vengeance.

Her guest was the kind of man Akel would normally have passed on the street without noticing him—a simple, rustic looking fellow, with a faded headscarf and scuffed boots.

“My dear,” Ela said, rising to greet him with the faintest touch of her fingers to his covered arm, “may I present the priest Iskandir of Rulat.”

She sank back into her seat, leaning forward to pour him a cup of tea.

Akel bowed his head to the stranger. “God smile upon you, sir.”

“God’s greeting to you, Akel Yalman.” The stranger had a rough accent—Rulati, so thick he must have come down from the plateau for the first time this year. “Your wife tells me you are willing to face God’s test.”

“Yes.” Akel sat, accepting his tea and studying the stranger—Iskandir. The man had green eyes, he noticed, in two different shades. It was a rare, but not unheard of, quirk of inheritance, believed to be a sign of God’s favour. Akel had once had a classmate with god’s eyes, and he didn’t recall that Erbek had ever come to much. He wondered if it explained why this man had joined the priesthood. A sense of destiny was a dangerous thing.

“You have been accepted into their army?”

“You see before you Captain Yalman, who must march out in two days.”

Iskandir let out a slow, almost wistful, sigh. “Well done. Listen, I have great need for a man hidden in the Savattin army, but it will be no swift task.”

“And who are you, to have such a need?”

Iskandir smiled, his mouth twisting up bitterly. “Haven’t you heard? The Dark God’s Children move through Tiallat still. I lead them.”

Akel drew in a slow breath. If this man was telling the truth, he must be the most wanted man in Tiallat, the leader of the resistance. Yet he sat in Akel’s garden, in a Savattin city, as calmly as if they really were just here for a tea party.

“What can I do?” he asked. “Tell me how to bring them down.”

“For now, nothing. Earn their trust. Listen. Watch. Remember. Once you are established in their eyes, design a code which only your wife can understand—tea orders for companies of soldiers, reminders of family birthdays to conceal dates, whatever works. She will pass the information to us.”

Akel looked at his wife. Ela nodded slightly, and he did not argue, not least because she looked alive again, for the first time in months.

Iskandir was looking at him, compassion in his eyes. “It may take years to stop them. The Fist of God—it is far more than human, something ancient and terrible beyond all of our comprehension. It may be that you never see the end of it.”

Akel nodded. He had been ready to die. This was, in a way, harder, but he understood the price. “I serve my country. I have always served my country.”

“Your family are known for it,” Iskandir said and turned to Ela. “This will be a hard test for you too. Are you ready?”

“Yes,” she said simply.

“If he is to succeed in his deception, you must embrace it too. You must become the perfect Savattin wife, beyond all reproach.”

She swallowed hard and Akel wanted to retch, imagining her wrapped in that prison of cloth, mouthing Savattin words, feigning subservience and concealing all her light and laughter behind high walls.

“I can do it,” she said, and Akel did not doubt her.

Nor it seemed, did Iskandir. With a sigh, he rose. “Thank you, both of you. Akel, go and be a captain. Ela, await my contact. May the Dark God watch over you both.”

“Not the Bright Lord?” Ela asked, with a faltering hint at a smile.

“It is not his season,” Iskandir said, before he bowed to them both and was gone.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 19, 2015

Rainbow snippets (19th December)

It’s time for Rainbow Snippets again, so here are six sentences from Resistance, which is out on December 29–ten days from now! This is from early in the book, and is a hint of what is about to come…

Loo

king down, Iskandir grimaced. He had stepped on a dead rat.

He kicked it into the gutter and then frowned, taking a closer look. There were four more lying there, their greasy fur matted and a pink froth drying around their mouths. He didn’t like the creatures, which had come creeping into the city in ever greater numbers as it declined under the Shadow’s rule. He wasn’t going to weep for their demise, but something about that little heap made him shudder.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

December 12, 2015

Rainbow Snippets 12-13 December: The Sea Has Many Voices

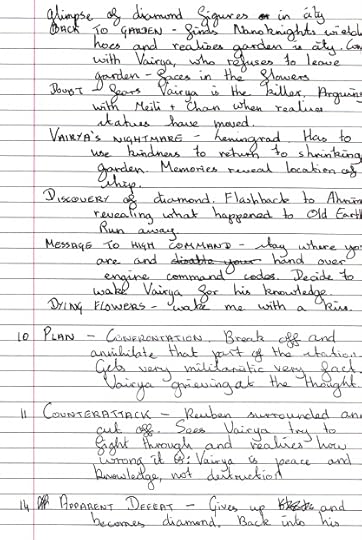

A little glimpse at my now finished Nanowrimo 2015 novel this week. In accordance with the rules of Rainbow Snippets, here are six sentences (if news of this Facebook group hasn’t reached you yet, do follow the link, because it’s a neat thing with many awesome authors involved). Whilst trying to find out more about the ghost who appears in his holiday cottage every morning, my hero has discovered a diary kept by Edwardian artist Joshua Haymer, a contemporary of the dead man. Here Haymer describes a shipwreck:

I heard her hull tear open, even up here, even over the rain and thunder—God help me, I hope I never hear another sound like that again.

The streets were full of people running down to the shore. I went with them—I’m still not sure why. It drew me, this terrible thing I thought we were about to witness. I have heard people sneer at common folk for running to gawk at accidents, but after today, I think that is unfair. Even when we are powerless to help, there is something in us that urges us to bear witness, to somehow reach out to the dying and tell them they are not alone in their last moments.

© Amy Rae Durreson 2015

November 29, 2015

Why, yes, I am still alive…

Apologies for the long silence. November is my second busiest work month, and adding all the catch-up after my week off and trying to do Nanowrimo has kept me buried. Huge apologies to anyone waiting for the newsletter–it will be out tomorrow, now I’ve hit fifty thousand words on my Nanowrimo project.

Heh. Fifty thousand words. A whole day early and without any all-nighters. It’s not the first time I’ve won, but this feels like a victory, not least because I struggled so much with it last year. I’ve written almost all of a standalone ghost story set on the Yorkshire coast. I’m not quite there yet (I reckon the final draft will come in at just under 60k), but I well into the final sequence.

If you fancy a peep at The Sea Has Many Voices, there’s a little bit from early in the story under the cut. It’s a bit rough and unpolished, but it will give you a glimpse of the guys I’ve spent the last month with. I’ve become quite fond of them. Here they’re waiting in Siôn’s holiday cottage to see the ghost that keeps appearing at sunrise (parts of this may only make sense if you’re a Brit).

Siôn’s breath caught as he realized what Mattie was looking at. Siôn had made full use of the shelving and space in the studio to store paper, paints and framing supplies. He had one piece from the previous day still drying, although it only needed half an hour more, and another awaiting a second layer of sealing spray. Framed and finished pieces were stacked along every free bit of wall.

“This is…” Mattie said, his voice slow as he moved around, looking at everything with fascination. “I thought you were just a holidaymaker, but this is professional. Is this your job?”

“No,” Siôn said reluctantly. “Just a hobby. One I’ve invested in, obviously.”

“It should be more,” Mattie said, drawing to a halt before the drying piece. Siôn had been pleased with this one—had felt for once that he had caught some of that quality of early light and morning mist, of the contrast between the gleaming waters of the still bay and the rough, exposed shore at low tide. “This is… wow.”

Siôn knew he was blushing, tried to scold himself for being so vain, but Mattie’s open wide-eyed admiration of his work was warming him from the toes up. “I’ve, er, exhibited,” he said awkwardly. “Just locally, of course, and I sell a few pieces.”

“So you’re a real artist?”

“Everyone who creates is a real—”

Mattie snorted. “Yeah, yeah, and everyone with a youtube channel actually deserves to be famous. Lol.”

“People say that out loud?” Siôn asked, bewildered and horrified, and then realised he’d been rude. “Oh, I’m sorry—”

Mattie laughed, his eyes bright. “I thought you were from London, mate, not the 1950s.”

Siôn’s lip twitched despite himself. That easy laughter was infectious. “I wish I could claim that I’m a deliberate anachronism, but I’m afraid I’m just terribly unfashionable.”

Mattie narrowed his eyes at him, but he was still grinning. “No worries. I won’t judge you if you want to sit up in your carpet slippers and listen to Radio 4 all night.”

“What’s wrong with Radio 4?” Siôn protested. “Everybody likes Radio 4—the Archers, Mattie! Desert Island Discs. The Shipping Forecast! How could anybody hate the Shipping Forecast?”

Mattie was laughing so hard he was hugging himself.

“And for the record,” Siôn said, feeling his own laughter come bubbling up, “I wouldn’t recognise a pair of carpet slippers if they jumped up and bit me.”

Mattie whooped, and Siôn’s own laughter broke out of him, a little hoarse and rusty, because he couldn’t remember the last time he’d done more than smile politely at a joke. Mattie, though, dancing on the spot as laughter exploded out of him, was so compelling that Siôn couldn’t help himself.

“Oh, god,” Mattie hiccoughed. “Sorry—just, your face. The Archers!” And he was gone again, stumbling over to the sofa to crash down on it and writhe with laughter. His t-shirt rode up, revealing a flash of flat, pale belly. Siôn, already flushed and alive with laughter, suddenly wondered how else he could get Mattie writhing with delight on his sofa.

But he was too old for someone as alive and joyous as Mattie—too old, too damaged, too plain. The thought sobered him and he held out a hand to Mattie. “Come on. I may be old and boring, but I can at least offer you a beer since you’ve come to stay in my haunted house.”

Mattie managed to swallow the last of his laughter and accepted Siôn’s hand up. “Coffee might be better, if you’ve got some. If I sleep now, I’ll be out until breakfast, so I might as well make an all nighter of it. Want to join me?”

“No,” Siôn said dryly. “I thought I’d go and sleep comfortably in my bed while you sat around down here by yourself and played solitaire.”

“Don’t let me keep you up, seriously. I’m just no good at mornings.”

“It won’t be the first sleepless night I’ve had,” Siôn said, quite honestly. “There isn’t a telly, but I’ve got some films on my laptop. If that doesn’t appeal, I’m sure we could find some interesting way to pass the time.”

“I’m sure we could,” Mattie said with a cheerful leer and a waggle of his eyebrows.

Siôn blushed again, to his dismay, because he knew his whole face would be turning scarlet, right up to the tips of his ears. “Cards!” he yelped. “I have a pack of cards, and there are board games, I think.”

“Shame,” Mattie said and winked at him. “Let me know if you change your mind.” And he vanished down the stairs as Siôn was still trying to work out how to respond to that.

© Amy Rae Durreson 2015

October 31, 2015

The Week That Got Away (surgery and second editions)

I’m currently feeling very, very lucky. This week could have been the week from hell, and instead, everything is okay (better than okay in some areas). So, let me catch you up.

First, I’m delighted that Reawakening is available again! The second edition was released from DSP Publications on Tuesday. The relaunch seemed to go very smoothly, and needed very little input from me, thankfully, as I had other things on my mind. I’m happy to see it back in circulation. The new edition only differs from the first in one area: it has an extra bonus story at the end. “Reemergence” is a tiny sequel about what Tarn’s hoard did next, and it introduces one of the main characters of Resistance.

On a less positive note, the reason I wasn’t shouting to the rooftops about the release was because on Monday afternoon I went under general anaesthetic to have surgery on my right retina. I lost most of the sight in that eye at the start of the month, due to a complication of diabetes, and got caught up in the NHS at its most brilliantly and bullishly efficient. The whole process was weirdly fascinating, especially as I’ve been in no pain at any stage of it, and I took a lot of notes. I also got to visit a new and interesting hospital, and somehow managed to fit in a museum visit and a fair bit of sightseeing around the medical stuff (I blame my mum for this, partly because I got the ‘while we’re here we should really go and see…’ genes from her, and partly because she was the responsible adult leading me around London this week (literally, at some points, as I couldn’t get my glasses on, which effectively made my good eye useless too).

So, here are some photos of a neat bit of London and lots of waffling about medical history which I think is a very cool subject, having written both fantasy and science fiction doctors in the last eighteen months (and there have been a couple of times in the last few weeks where I’ve imagined Hal and Reuben standing behind my shoulders). Any gruesome medical details are historical, not from my own experience (although I’ve been hanging around hospitals since I was a baby, so my ‘gruesome’ may not be the same as yours)

This one was taken almost two weeks ago, when I first went up to London to see the specialist (I’d been sent on from my local hospital by then). This is the avenue of trees leading to the London Eye and those are fake bats. When I spotted the first one, I actually thought it was a dead pigeon, until I realised how many of them were there. One of the more effective bits of Halloween decoration I’ve seen this year.

Westminster bridge on the same day. Given this is the iconic London shot, I was taken aback by how long I had to stand there before a red bus went across it.

St Thomas’ Hospital is just beyond Westminster bridge, about five minutes walk from Waterloo, the station where I come into London, which was handy (both my dad and brother have ended up being referred to London hospitals in the suburbs in recent years and they’re a pain to get to). It has a fascinating history. As an organisation, it has existed for centuries–it is thought to have been named after St Thomas Becket and was already being referred to as ancient in 1215. Originally, it was a hospice for the poor and sick, run by Augustinians. In the early 15th century, the Lord Mayor, Richard Whittington (yes, that Whittington) endowed a lying-in ward for unmarried mothers, and it gradually grew and grew, spawning a sister hospital, Guy’s, and eventually being forced to move to its current site in the 1870s. It now stands on the bank of the Thames right opposite parliament and is a major research and teaching hospital. It’s huge, and must have one of the best views of any hospital in the world. I am very glad I ended up there, because they were superb.

On the day itself, we ended up in London with about an hour and a half to spare, and since it was such a lovely day, walked a slightly longer route, over the Jubilee Bridge, along the embankment and then back over Westminster bridge. It’s probably about a mile’s walk but you could spend all day taking in the history and views. Here’s a few highlights.

Looking over the Thames from beside the London Eye. Since taking this picture, I’ve been reading about the amazing Tower Lifeboat that covers the Thames through central London (it was a tangent from a tangent from my main research) and now know that this is one of the dangerous points on the Thames, because if a swimmer gets trapped behind that barrage, the lifeboat can’t get in close to help them.

This is the Hungerford railway bridge, flanked by the two Golden Jubilee footbridges. We decided to cross on the other side of the railway, so we could enjoy the view of the City of London.

Before we got there, though, we passed this busy carousel. You can see just how crowded the South Bank gets in half term!

Looking downriver, with Waterloo Bridge in the foreground, St Paul’s to the right, and the London skyline.

Looking back at the Eye from the other bank. The square modern building above the boat on the right is the hospital. The eye ward is up on the 8th floor, with views down over Westminster Bridge (and, yes, we were fully aware of the irony of putting patients who can’t see into a room with one of the best views in London).

The Battle of Britain memorial. This week was the 75th anniversary of the end of the Battle of Britain. We watched the memorial flight go over us from school a few weeks ago, and it’s something everyone in the UK knows about. Many of the buildings in my earlier pictures were severely damaged in that dreadful summer and autumn, and many of the more modern buildings stand in the places where older ones were destroyed. Even St Thomas’ hospital was heavily bombed (you can read a firsthand account of one of the bombings here), and a core group of surgeons kept going with life-saving operations in the basement even when the hospital was left with no electricity, water or lights (they sterilised their instruments in the flames of camping stoves).

Crossing back over the river, having fought our way through the horde of tourists trying to take pictures of Big Ben striking noon. I’m glad to report that its hands didn’t fall off and we were far enough away that it didn’t leave our ears ringing (it’s really, really loud when you’re this close).

We had half an hour to get to the hospital and up to the eighth floor and I was wheeled off just before two. All went as smoothly as it possibly could (I assume from the aftermath, since I was out cold). I got back to the recovery ward just as it was getting dark and lay there for a while listening to Mum rhapsodize about the night view I couldn’t see, and pop in and out to catch up with all the cataract patients she’d befriended in the waiting room. I was on my feet by eight and we walked back to the station. The only difficulty was that the dressing they’d put on me was so big I couldn’t get my glasses over it and I’m incredibly short-sighted. Anything more than a metre away was either a blur or an enormous sparkly blur in the case of lights. It made getting back to the station interesting, but I can report that the London Eye looks fucking awesome when all you can see of it is a ring of vast multi-coloured sparkles (this may be the general anaesthetic talking).

We went back the next day to have the dressing removed and my sight was almost completely clear (I have some very slight blurring around the edge still, but that should heal). So we went sightseeing, since I finally could see. I dragged Mum around the exhibit on the history of the hospital (in the 17th century, I discovered, a pioneering surgeon who wore a turban was able to prove his headgear saved lives, mostly because his colleagues just kept on wearing their usual filthy wigs as they operated). She then dragged me away for coffee and then we went around the Florence Nightingale museum which is also on the site. We also got to appreciate some of the beautiful tiled pictures which are mounted along the main corridor and gladly spent some money in the little shop which raises funds for the hospital. We’ve both seen a lot of hospitals in our lives, and were impressed beyond words with how calm, capable and caring all the staff at St Thomas’ were.

You can buy a set of postcards of the tile paintings which hang around the hospital. These were originally commissioned from the Doulton China company to decorate the children’s wards which opened in 1901 and 1903. They show scenes from fairytales and nursery rhymes and could be easily cleaned, being made of tile. The wards were damaged in the bombing in WW2, but the tile paintings were rescued and rehung in the modern hospital when it was rebuilt. I’d seen several walking around the hospital and had been charmed by them, so was delighted to get the full set. From the top: Red Riding Hood x2 2nd row: Sleeping Beauty x 2; Rock a Bye Baby; Bo Peep x 3 3rd row: Cinderella x 3; Jack and Jill x 2 (both on their way up and rolling back down the hill); Little Jack Horner 4th row: Puss in Boots x 2; Miss Muffet; Dick Whittington x 3 (yup, him again) Bottom: Babes in the Wood; Billy Boy Blue; Old King Cole; Jack and the Beanstalk

We then toddled back over Westminster Bridge and along Whitehall to have lunch in Trafalgar Square (soup in the Cafe in the Crypt was exactly what I needed). I spent the next few days at my parents, where the highlight was the homemade get well cards from my nephews which appeared in the post. I’m now home and, apart from having the energy levels of a twice-brewed teabag, feel perfectly fine.

I’m well aware that I got off incredibly lightly, and am very grateful to everyone who has helped me out, from my colleagues at work who have cheerfully merged and reorganised classes to allow for my absence (and who will continue to do so next week) to everyone at Dreamspinner who shifted deadlines and fixed problems for me (my editor is amazing). I’m hoping I’ll be back at full strength soon.

And, here, to finish are my get well cards XD

From my nephews, aged 2 and 4.

There was a rainbow on the front XD

August 29, 2015

A Walk Through the Woods

So, yesterday morning I headed out to take advantage of what the weather forecast assured me would be the only completely sunny day for some time. I’d decided the night before that I wanted to go walking, but it wasn’t until I’d finished my breakfast that I decided where to go. I decided to pick up the Serpent Trail from where I’d stopped after climbing up to the Temple of the Winds in January. The path up onto Marley Common is about half an hour’s walk from Haslemere station, and I started in good cheer.

Until it started to rain. By the time I got to the bottom of the path, the initial drizzle had turned into torrential rain and I beat a hasty retreat downhill to cower in a bus shelter.

For a while I thought my day out would end with posting this picture, taken from under the bus shelter, on my way home. Luckily, the buses back to the station only run hourly and I’d just missed one. I sat here for half an hour, reading Level Hands (which is excellent) and then, to my delight, the clouds passed over and the sun came out again.

The path up from the main road is up a sequence of steps and steep paths, all of which were deep in leaf mulch that had washed downhill under the force of the rain. The trees were still dripping as I made my way up here and through the woods at the top.

Then the woods opened out into a flowering heath. This picture doesn’t do justice to just how bright the gorse and heather were, under sunshine, just after rain. This is my favourite type of local walking, where long shady paths through the woods give way to little patches of heathland or sudden views over the hills.

And back into the sunlit woods.

These trees looked like they were dancing (entwoods!)

This sign made me smile. Too bloody right.

I’m not usually a sun worshipper, but I sat beside this pond for twenty minutes and basked while watching the dragonflies.

From the pond the path rose up through the woods again.

The signposting was superb all the way along, but I had my head down at one point and must have missed a sign because I ended up following this path across the back of Chapel Common rather than going round the edge of it. I think I missed a bit of Roman Road, but it was such a lovely bit of woodland I couldn’t care too much.

By this point it was early evening and the sun was just beginning to slant down through the trees.

I eventually came out on the corner of the common, where I found these ladies in residence. The National Trust manages many of the local commons, and grazing cattle have been reintroduced to them as a way of managing the land. As the names suggest, many of the local heaths were originally common grazing land and only became tree-covered during the twentieth century. There’s a lot of work going on to gradually and sensitively return them to their earlier state, not least because true heaths are habitats for many rare species. This one was agricultural land and has been allowed to become grassy again.

Summer is now coming to an end here again. I’m back in school at the end of this week, and I know all the demands of the autumn term are about to hit me. I’ll probably go quiet again for much of the next few months, but the newsletter will keep going out, and I’ll definitely be around for the Reawakening relaunch at the end of October. Enjoy the autumn, everyone :)

August 18, 2015

Newsletter launch and the loneliest stretch of the Thames

A double-headed post this time, as I have an announcement and then I’ll be sharing some of this summer’s walking with you. I’ve decided to start sending out a regular newsletter (some of you have already spotted it, as I added the links to my site earlier in the week–you guys are amazing!). I’ve got a few new releases coming up over the next six months, so expect news, missing scenes (I’m currently writing a little Reawakening extra from Gard’s point of view), and contests. I’m aiming to get this month’s out on the 20th, but after that it will be closer to the 15th of every month.

In less promotional news, my summer is slowly fading to an end. I’ve spent a lot of it editing and writing, but I have had time to fit in a few walks and outings. In particular, Mum and I have been continuing our walk along the Kent coast. We’ve done three walks this summer and managed to cross the Hoo Penisula, which must be one of the most remote places within 40 miles of London. It’s a great bulge of marshland between the River Medway and the Thames but on its far side was our target for the summer: the town of Gravesend and the first possible crossing of the River Thames. In all our coastal walking, our rule has been to cross any river at the first crossing inland, whether that is a ferry or a bridge. We’ve had to walk a long way to reach this one, picking our way around the various inlets and minor rivers of north Kent. The Hoo was the last obstacle, and we were a little nervous about it. Parts of its coast are inaccessible, and the only long distance path that crosses it takes a much more inland route than we wanted. We came up with a compromise, cutting off the tricky corner so we only walked twelve miles of lonely sea wall rather than the twenty-odd we would have needed to do it one day to cover the whole thing.

We began at Rochester, on a grey, muggy, horribly warm day in July.

Looking back across the water towards Rochester, the castle and the cathedral stand out against the skyline. The sub is the U-475 Black Widow, originally Soviet, now in private hands and awaiting restoration. The concrete structure in the foreground is more interesting than it looks. It’s the remains of the lock where a long-vanished canal met the Medway. The Thames and Medway Canal once cut through the back of the Hoo Peninsula, connecting the Medway to the Thames at Gravesend, passing through a 2.2 mile long and 35ft high tunnel at the Medway end. The tunnel took so long to build that the canal didn’t open until 1824, by which time the military need for the connection had vanished with the end of the Napoleonic wars. By 1840, the new railway line to Strood had been laid through the tunnel alongside the canal, and the railway still passes through the tunnel today, although the canal is long gone.

As we walked along the water’s edge, we glimpsed the towers of Upnor Castle ahead of us. The castle is a small fort which was originally built to defend approaches to Chatham Dockyard on the opposite bank. Later, it was used as an ammunition depot. The village grew up around the fort, supporting the navy families living inside the fort.

The gunpowder arrived by boat to the base of the fort, which was roofed in at the time. There are tunnels in the base of the fort but much of it was stored in the main fort. It was lifted by a pulley to a bay several stories up. The pulley was originally operated by men who seized the other end of the rope and jumped from the upper story windows, but that was eventually deemed too risky. Inside the fort, the rooms are designed so that no sparks could be struck by accident: the doors and windows are copper=sheathed, the handrail on the stairs is covered in lead, and the wooden floors were constructed without the use of nails.

You can even get married there, with your guests perched on padded gunpowder barrels.

Upnor High Street is a lshort cobbled street which stretches from here to the edge of the cliff, where the side door to the castle opens straight onto the road.

After leaving Upnor, we walked along the edge of the water, along a path which can only be followed at low tide. We stumbled across this crumbling brick structure, which we guessed might a lime kiln or another military relic.

Offshore were more abandoned wrecks.

Soon though, we left the banks of the River Medway and headed across the farmland that covers the centre of the peninsula. It was very hot once we left the water. We finished our walk at the tiny village of St Mary Hoo, where we had to call a taxi to get back to the nearest station.

We returned to St Mary Hoo three weeks later. The church here is now part of a nursing home. A few years ago, there was a proposal to build a new airport on the Hoo. If it had gone ahead, the church, the village and all the outlying farms and cottages would have been demolished to make way for it. A past rector of the church was the one who performed the illegal marriage between the future King George IV and his mistress Mrs Fitzherbert in 1785.

Following the footpath north, we caught our first glimpse of the Thames. In theory, our path continued onwards to the sea wall, where we would simply follow a path all the way round the edge of the peninsula until we reached Cliffe Creek on the western side.

Numerous climbed gates, paths so overgrown they were invisible, and fences across the path later, we finally made it to the water’s edge, only to find the seawall was only a few inches wide and the path which supposedly ran beside it was impassable. We walked on a track behind the embankment, but soon found that the land was being worked on. Much of it was blocked off with plastic fencing with only small stiles cut out to make it passable. It was several miles until the narrow wall vanished and we could walk along the embankment, but the path was still very overgrown. We knew these paths probably weren’t used much, but we were still taken aback by how tricky they were to follow, given they were supposed to be public rights of way. When we got home, we investigated and couldn’t find anything other than rumours about what was happening. It’s either a huge housing development or a scheme to alter the seawalls to create a water capture area to help manage flooding upstream. Whatever is happening, it seems likely that the paths are doomed.

At the end of the peninsula, tucked into the corner, these huts are part of an old military training area. Although you can’t see them from the path, there are many tiny ponds here which are the flooded remained of WW1 trenches. This was one of the sites where they trained soldiers in trench digging. The nearest road is a couple of miles across the marshes, and there aren’t even official tracks linking the riverbank to the lane. On the water, however, cargo ships go heading into the port at Tilbury on the north bank of the Thames. At this point, we hadn’t seen another soul since leaving the taxi at St Mary Hoo. As we drew closer to Cliffe Creek, however, we began to meet other walkers. We swung inland between defunct and flooded gravel pits, now a nature reserve, until we reached the village of Cliffe. It’s a strange little place. It was founded by the Romans, once supported several industries, has one of the the biggest local churches in Kent, was a medieval port, and once had a branch line and a canal. Dickens set the start of Great Expectations here. Today, it’s very quiet. There’s one local shop on the outskirts, a single pub, and a bus three times a day. Even the lights in the public loos at the bus stop don’t work. We were in time for the last bus back to Gravesend, which wound its way in loops all over the Hoo.

We returned to Cliffe a week later to walk the last few miles from the edge of the Hoo to the ferry at Gravesend. This is Cliffe Creek at low tide, with a slightly wreck from some of the others we’ve seen, and Mum and I spent some time speculating about this one.

Unfortunately our easy walk then got tricky as we discovered the path was closed because it had subsided and we had to take a very long detour away from the water, through a farm and along a very long path which went right through the middle of a huge gravel works before we finally got onto the embankment.

We didn’t see many people, but we did have some company on our path.

Very suddenly the wilderness gave way to the industrial outskirts of Gravesend. Within a few hundred metres of this area, we crossed the opposite end of the old Thames and Medway canal and found ourselves in a park in the centre of town.

By now the tide was high and we had to wait for this ship to pass before our boat could cross the river. This one is on its way to Zeebrugge. It was being followed out by a pilot ship waiting to take their pilot offboard once the ship reached the sea.

This, however, was our ferry. It chugs back and forth between Gravesend and Tilbury on the north bank. We went across, because it was there, and then came straight back again.

We then headed back into Gravesend. We were impressed by the extensive yarnbombing (the knitted seagulls on the pier were great too).

Gravesend is also the burial place of Pocohontas. She was taken ill on ship on her way back to the New World and brought ashore at Gravesend for medical attention (a grim prospect in 1617). Sadly, she died here, aged no more than 22. The exact location of her grave is unknown, but this memorial stands in the churchyard.

July 13, 2015

In Heaven and Earth: Under the Dashboard (Massive spoilers under the cut too)

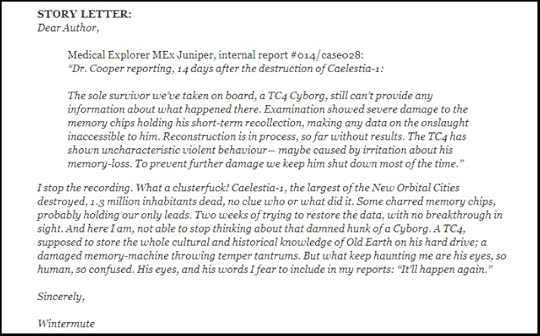

Yesterday my free story In Heaven and Earth was posted as part of the Goodreads M/M Romance group’s Love is an Open Road Event. It’s my third year doing this event, and I always enjoy it (my previous contributions were The Lodestar of Ys and The Court of Lightning. This year, however, I was faced with a new challenge. This year, I was writing Science Fiction. This is the prompt I claimed and you can see the picture that inspired it, and the story I wrote by going here..

I’ve written science fiction before, but not to this length and not with a romantic focus. I absolutely loved playing with a different palette, and finding ways to work in a few of the skills I’ve learned writing fantasy. This time I thought it might be interesting to talk through how I went from the initial prompt to the final outline I worked from to write the story. Although I write straight onto the computer, I tend to do most of my planning by hand, so I can scribble around the edges and over the top. Under the cut, you will find eleven pages from my planning notebook which I’ve scanned in (nothing fancy here, just an A4 exercise book and a pen). I always have a scribble book or two on the go, although for longer stories the planning tends to be muddled with other things I’ve jotted down in the process (to-do lists, shopping lists, reminders to take the bins out, doodles of dragons chasing stick-Gards, etc).

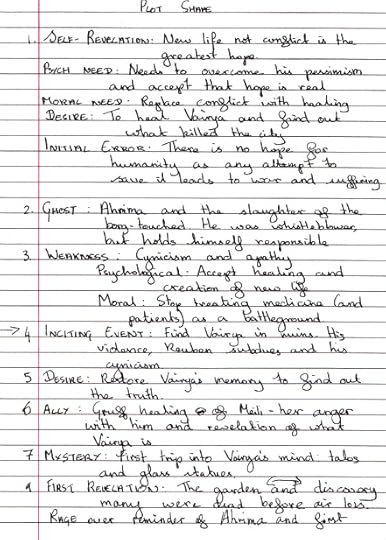

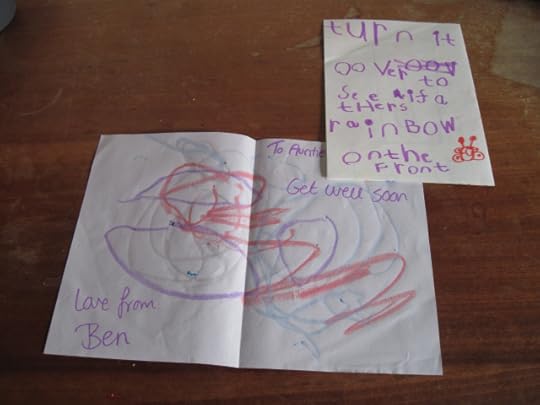

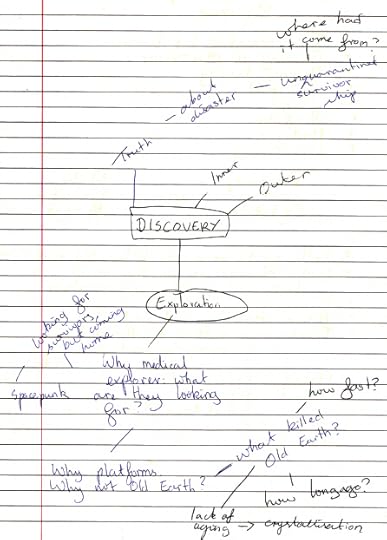

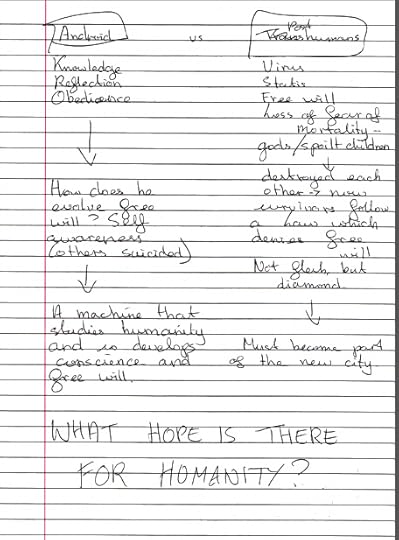

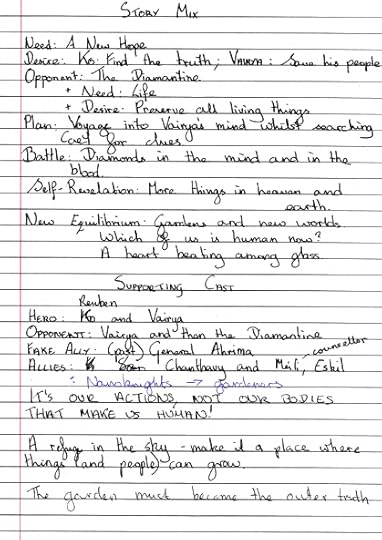

1. Okay, so this is the starting point. From the prompt or initial idea, I mindmap trying to find big themes and/or questions which might break open the story. At this stage, I’m just jotting down initial thoughts. This is a fairly small one, because I got a sense of direction very fast, but I’ve done ones of these which fill a whole page.

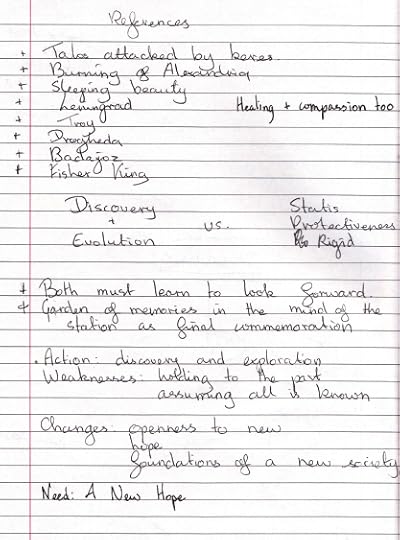

2. The next stage is to hone in on some of those big ideas. I’m doing that on the bottom half of this page. The top half was an idea that never made it into the final version: that Vairya’s memories of human history would include lots of sieges, and therefore each trip into his mind would take place in a different locale. You can see the first hints of the central conflict here (and that I can’t spell ‘stasis.’

3. Here I started honing in on those conflicts, especially the contrast between Vairya and what I eventually called trolls. At this stage, I was still playing with ideas and looking for connections and conflicts, hence the mixture of ideas and questions.

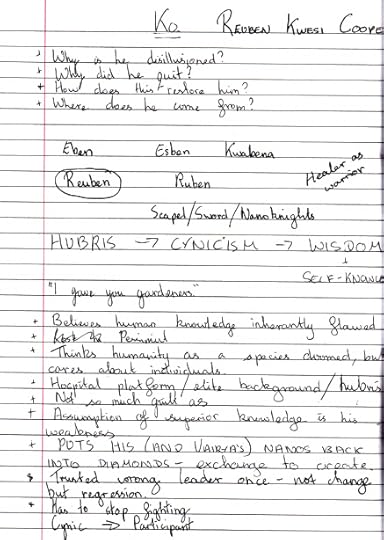

4. I then left the philosophical debate to mature in the back of my mind while I considered my protagonist. He didn’t become Reuben until very late in the planning process, and you can see some of the alternative names jotted down here (he’s referred to as Ko in some of these pages, but it just wouldn’t stick).

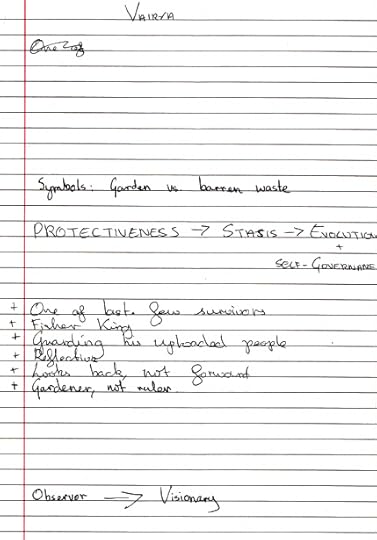

5. I did a similar sheet for Vairya. His is less detailed because I didn’t need to be inside his head. I didn’t actually get a clear sense of him until he started to banter with Reuben in the writing of the thing. I thought he was going to be distant and spiritual, not a snarky little git (I really should know better by now). His name was easier to pick. All the TC4s are named after angels or intermediary gods. Xšaθra Vairya is one of the divine sparks of Zoroastrianism (his name means ‘Desirable Dominion’ and he was later identified as the spirit associated with metal from the sky). Also the page on which I finally remembered how to spell ‘stasis.’

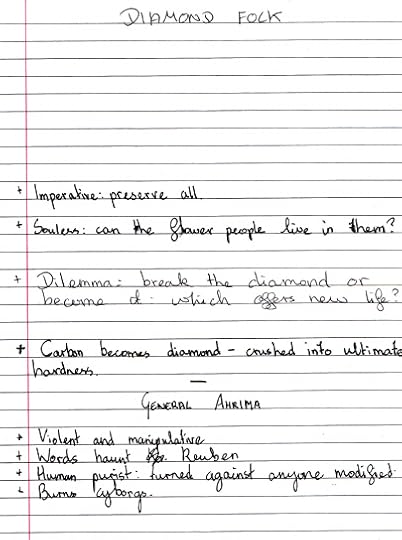

6. And then came the villains. The diamond trolls are the main antagonists, but Ahrima is the one who haunts Reuben, and I needed a clear sense of her as well (he name also derives from Zoroastrian traditions).

7. With the characters and themes established, I then started thinking about story structure. Those who are familiar with it may notice I’m drawing on John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story here. I worked through it last Christmas in an attempt to tighten up the saggy pacing in the middles of my stories. I have some issues with it, but as a planning tool it really makes you focus on character change as the central driver of plot. I also like the way it makes you start by identifying the different types of need and desire that are driving your protagonist.

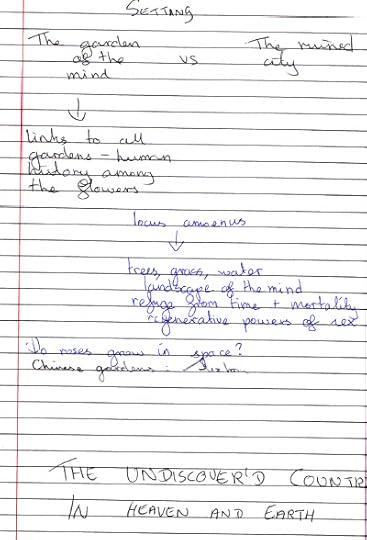

8. And setting, my favourite bit. Not many notes here, because I could see Vairya’s garden in my head by then, but I did jot down some terms and ideas from my research. By this point I’d realised it was going to be literature, not history, that informed Vairya’s imagination, though the whole quotation thing took me by surprise as I wrote. At the bottom here I started jotting down possible titles, both from Hamlet.

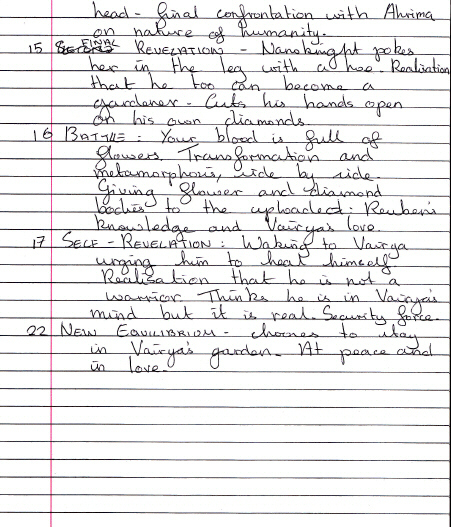

9-11. And the full plot outline (again you can see Truby’s usefulness as a planning tool here, though I never use all of his steps). I didn’t stick to this exactly, but it gave me what I needed: a sense of direction, an awareness of where the characters needed to be when the story ended, and some idea of how the journey to that destination was going to change them and the world they lived in.

So there you go. That’s how I plan a story.