Amy Rae Durreson's Blog, page 6

January 21, 2016

The fruit is dead, and yet the leaves are green (Aldershot in Winter)

So, my hometown’s a shithole. Nobody disputes this. Even the locals call Aldershot “All-the-shit”. It’s sprawling, ugly, poor, the only local crime hotspot, the only place for miles where the houseprices won’t quite bankrupt you, it’s dirty, it’s lairy, it’s drunk in the gutter when all the other local towns are sipping tea at a garden party and sneering in our general direction.

It’s an army town where, when I lived in the town centre, I was regularly roused from my bed of a Sunday by the sound of drums and I’d lean from the window to watch the parade go marching by, first the serving soldiers and then the stiff-backed veterans with their medals gleaming. It’s the first army town, the self-proclaimed ‘Home of the British Army’. The first thing you see when you walk away from the station is a fucking great gun on the roundabout. Besides the new shopping arcade stands a memorial to the soldiers once barracked on the site. Scratch any surface in town and the military are there.

It has the UK’s biggest Buddhist population and its first Buddhist community centre. The Dalai Lama has visited more than once. Sherlock Holmes investigated a strange death here. John Betjeman mocked us fondly. The IRA tried to blow us up (and we still raise a finger in their direction now and then, the fuckers). Everyone who lives here moans about how shit it is, but Aldershot people rarely leave. My landlady grew up twenty doors further up the road (I live in what was her grandfather’s house). Her husband came from foreign parts–he lived on the other side of the road. Now in their seventies, they live two roads away and she still lingers to reminisce over her childhood every time she sees the views from my window.

Like everyone else who lives here, I hold the town in a terribly fond contempt. I certainly never meant to set a book here.

But I did. A Frost of Cares is a ghost story set in the (imaginary) mansion of Eelmoor Hall, in the countryside just outside Aldershot. Luke wanders across my heaths, digs into the history of my town. Hell, he even shops in my favourite supermarket.

This was kind of weird for me. I usually write fantasy and there was something oddly compelling about sharing the land on my very doorstep (also, as those of you who have read the first paragraph will know, Aldershot makes me really fucking sweary).

So I thought I might head out last weekend and get some pictures of the scenes Luke sees at exactly the right time of year (A Frost of Cares takes place between Boxing Day and late January). So here’s a rough history of my rough town, complete with pictures which make it look a hell of a lot prettier than it actually is.

Until 1854, there wasn’t much here. Depending on the century, the population varied between 100 and 150 residents. They lived on the hillside and this was their church, St Michael the Archangel. Below them in the valley were the upper reaches of the boggy River Blackwater which rises to the southwest of the modern town. On the next hill there was a windmill and around them rose the bleak and lonely heaths. It was a hunt of highwaymen, almost as notorious as Hounslow Heath.

The history of Aldershot after the army arrived is pretty well-documented, but digging past that to find out about the earlier history is quite tricky. I found the house I wanted to adapt into Eelmoor Hall, my haunted mansion, long before I worked out what era my ghost came from (Eelmoor Hall is loosely based on Bramshill House, ten miles away). This house, on the other hand, is Aldershot Manot, dating from either 1670 or 1630, depending on what source you trust (which date is correct makes one hell of a difference, considering there was a war between the two). It was the missing piece of my jigsaw, because the family who built it were Tichbournes. They were a branch of a very powerful and wealthy family from Winchester way and, all importantly, they were staunchly Catholic in an era where that could be a death sentence. A very distant cousin schemed to depose Elizabeth I and it’s from the poem he wrote the night before his death that I took the title of the book. For my purposes, I was intrigued by the mid-seventeenth century Aldershot Tichbournes. What if, I thought, Sir Walter hadn’t built this modest house in what is now the town’s park? What if he’d built a bloody great mansion on the heath on the other side of town? What if my ghost came from that tumultuous century, when the English Civil War tore apart this part of the country?

In the 1790s, Aldershot found itself with a canal. The Basingstoke Canal runs about a mile north of the old village. I’ve blogged about it many a time, but last weekend I set out along the towpath to find the precise setting of A Frost of Cares. I began here at Ash Lock, half an hour’s walk from the centre of Aldershot, where the canal was iced over.

A little further along I came across this new sculpture celebrating the canal. From this angle it is obviously a hand holding a tree. Approaching it upon the towpath, however, it was rather more baffling and a little too phallic for such a public setting.

This is all that remains of Farnham Wharf. When the army first came to Aldershot, they established two camps on the heath, one on each side of the canal. The South Camp became modern Aldershot Garrison and the other still gives its name to the suburb of North Camp. Army supplies were once unloaded here. There was even a popular inn, until the powers-that-be took objection to its cheap ale and loose women and evicted the landlord (he didn’t leave the premises until Army sappers started demolishing it around him).

The canal is pretty. Many of the bridges across it are of military construction or have been recycled from military purposes. They aren’t so pretty.

This is Eelmoor Bridge. When I decided to set A Frost of Cares in an old military college, I needed a location that was a fair way from any other settlement. Looking at the map of North Hampshire (army country), one location leapt out–the triangle of land between Farnborough, Fleet and Aldershot. I was drawn to this part of the open land, just on the edge of the military training area. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve walked here in the last decade. It’s always eerie.

This is Eelmoor Flash, once a turning point for boats. In all the years I have been walking the towpath, I have only seen clear skies here once, even on days when the rest of the walk was sunlit. How could I resist such a setting for a ghost story?

Here’s the Flash and surrounding heathland from the bridge.

Leaving the canal, I headed up onto the army land, in search of the precise location of Eelmoor Hall. This is the track up the real Eelmoor Hill–a possible driveway leading to the Hall?

Was this pile of rubble the closest I would get?

Or was the Hall here, behind this barred gate festooned with No Entry signs?

This was exactly the landscape I imagined looming around the Hall. All of this land is used for training infantry. it’s also open to the public although you are warned that you may be startled by loud bangs. More often you find yourself suddenly stalked by twenty lads in camo trying to learn how to do that stealth thing.

In the book, Luke and Jay visit the observatory behind the Hall. There was a hillock in the perfect place–shave it of its gorse and it would present stunning skies. Even in its raw state, the view was compelling.

The army came to Aldershot in 1854 and never left. In 1851 875 people lived in the village. By 1861 the population was over 16000 of whom around 9000 were military personnel. it was a rough and rowdy boom town, in its way, swelling out to fill every hillside with terraced houses and the paraphernalia of Victorian life (my own road, half a mile from the old church, was built house by house between 1905 and 1920). Aldershot became defined by the army and by its life. Local roads and pubs are named after obscure battles (although I hear that even the fabulously titled Heroes of Lucknow pub is now a Co-Op, like so many others. Alas). Memorials are scattered all over town. Here in the park is our war memorial. This little garden commemorates the second world war. It doesn’t name individuals–they are gloried elsewhere–but the stones around the edges of the grass are all from bombed towns across the UK. Even today, men and women from across the country come to serve in Aldershot and the town’s memorial remembers them all.

This is the military town’s very own little observatory. Soon houses will surround it. Many of the old garrison buildings are being demolished to make way for a new housing estate, already named Wellesley, although no houses have yet been built. It will nudge up against the woods that reach out towards Eelmoor Flash, bringing Luke’s lonely, haunted mansion suddenly onto the outskirts of suburbia.

This is our high street, a little grim now, but once the heart of a thriving little town. The town lived off the army, and a peek at the town’s directory in 1905 reveals everything from tailors providing uniforms to undertakers to stables to tiny private schools run by gentlewomen for the daughters of officers. Much of that vibrant life has gone now. The garrison here is much smaller than it was in its heyday, and Aldershot is now mostly just the cheapest place in miles (although if you compare average income to average house prices, we’re one of the ten most expensive towns in the UK).

The view from my bus stop in town, looking down Victoria Road, named for the Queen who sent the army here in the first place. On the hill in the distance once stood the village’s windmill.

Back in the park, I snapped a picture of the tennis courts to recall John Betjeman’s tennis playing ‘Miss J. Hunter Dunn, Miss J. Hunter Dunn, / Furnish’d and burnish’d by Aldershot sun.’

This is the most modern part of modern Aldershot–our new supermarket, restaurant and cinema complex. It was built on the site of the old car park, which itself was built on the site of an old barracks. In the book, Luke doesn’t like it much.

It’s even got an underground car park, which surprised me by being one of those details that caused lengthy editorial discussions on the definition of different names for places you might park XD

And that’s my town :) It’s a funny old place, but I’m actually kind of glad I set a book here. It’s not a bad place, in its own way, and it has all sorts of hidden beauties.

![FrostofCares[A]_headerbanner](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452427539i/17692274.jpg)

Pre order on Amazon.com Amazon.co.uk Barnes and Noble All Romance Apple Kobo

January 16, 2016

Rainbow Snippets (16th-17th January)

Another week, another six sentences for the amazing Rainbow snippets group on Facebook. If you’re not following this, do go and have a look, because loads of authors from eveyr corner of our genre are joining in to share six sentences a week

Mine this week is again from A Frost of Cares, my ghost story which comes out on the 27th. Here’s Luke on the subject of ghosts…

The question was whether the enemy was the Ghost of Eelmoor Hall (unlikely) or whether it was my own subconscious finally falling over that last edge (probable). It didn’t help that I kept hearing that slow creak-creak of steps outside the door, or that it stopped dead every time I noticed and tried to focus on it. I knew it was just the natural noises of an old house on a cold, damp day, and that all ghost stories rose out of the power of the human imagination and our minds’ inclination to create a story out of random incidents.

Every time I got lost in my own thoughts, however, the automatic lights eventually clicked off, and I knew that I was not alone.

Why was I so certain?

I could hear her breathing.

![FrostofCares[A]_headerbanner](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452427539i/17692274.jpg)

Pre order on Amazon.com Amazon.co.uk Barnes and Noble All Romance Apple Kobo

January 14, 2016

From Jane Austen to bloody war: A Visit to Alton

Just before Christmas, Mum and I spent a day in the local market town of Alton. I’d given it a passing mention in A Frost of Cares and was curious to track down the real life evidence of the battle I’d alluded to. She had never been to Jane Austen’s house at Chawton, and neither of us had ever been to the town museum. The town is only an hour or so away by bus, and we had both finished our Christmas preparations and were twiddling our thumbs. A day out seemed like a good idea.

We headed for Chawton first. These days the outskirts of Alton press up against the village, but in the early nineteenth century it was a pleasant little place of its own, about half an hour’s walk from the old market town. After the death of Jane Austen’s father, her wealthy brother offered his mother and unmarried sisters the choice of a number of cottages on his estates. They chose a handsome house in Chawton, and Jane lived there until the final weeks of her life, when she moved to Winchester, some 15 miles away, to be closer to her doctor (she died there, in a little yellow house behind the close, and is buried in the cathedral). Most of her books were either written or redrafted there, on a low round table that still sits beside the front window of the cottage, where she could see the other residents of the village passing by.

This is Chawton. In the summer, all these cottages have wonderful gardens bursting with flowers. Even in a damp midwinter, it’s a pretty place.

This is the back of the Austens’ house. It has been mostly restored to Regency furnishings and operates as a small museum. Some family trinkets are on display, and the rooms have been set out as they would have been in Jane’s day. The first floor window on the left is the room she shared with her sister Cassandra. I haven’t taken any pictures of the interior, because they do ask you not to, of course.

We were almost the only ones there (though in summer they get coach parties cramming in). The whole house was decorated in appropriate style–no tree, but fresh greenery lining the windowsills and fireplaces and in pots and vases. The wreath caught my eye.

After a pleasant hour, we decided to move on. We had an excellent lunch in the village pub and then headed back into Alton itself. I wanted to find St Lawrence’s church in the town centre, which looks very peaceful in the pictures below. In December 1643, however, it was the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the English Civil War.

Here is the south door of the church. The flowers are roses, blooming in the mildest December on record! It was a much colder day on December 13th 1643, when the Earl of Crawford was stationed here with two regiments of the Royalists army, one of cavalry and one of infantry. They had set sentries on the roads, but hadn’t taken into account the hard frost which froze the ground and the Parliamentarians’ newfangled leather guns, light enough to be led by a single horse. At dawn, the sentries on the west of the town saw five thousand Parliamentary troops emerge from the woods. Six of the sentries were captured, but one managed to raise the alarm. Crawford and the cavalry broke out towards Winchester at a gallop, promising they would bring reinforcements. About six hundred foot soldiers were left in Alton to face an army of five thousand. They were driven back through the streets of the town until they were forced to take shelter within the church grounds.

For two hours, the Royalists held off their attackers, even as the Parliamentarians hurled grenades through the windows and fired rounds at the church (the picture above shows just some of the musket holes in the south door). The Royalists were forced into the church, without even enough time to barricade the doors behind them. At the last, they retreated behind a bulwark of dead horses, as their commander, Richard Boles threatened to “run his sword through him which first called for quarter.” It wasn’t until Boles himself was killed that the survivors surrendered. Over 100 Royalists were killed and about 500 taken prisoner. The Parliamentarians lost ten men.

There is still a plaque commemorating the battle and Boles’ actions inside the church. When Luke and Jay start investigating the ghost of Eelmoor Hall in A Frost of Cares, they find a connection between their ghost and one of the Royalist officers killed in this battle.

From the church, we wandered back into the town to visit the museum, where Mum indulged me while I cooed over the Alton Buckle, their gorgeous Anglo-Saxon treasure (it’s actually very small indeed. Somehow I imagined it would be the same size as the illustration of it on the front of my old Old English textbook XD). On the way back to the bus stop, the colourful display outside this shop caught our eye (“Brussel sprouts for Christmas lunch!” said Mum. “Oooh, hyacinths!” said I, and we were both drawn in. Two of those pots of hyacinths on the bottom row have been flowering madly on my kitchen windowsill for the last two weeks).

![FrostofCares[A]_headerbanner](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452427539i/17692274.jpg)

Pre order on Amazon.com Amazon.co.uk Barnes and Noble All Romance Apple Kobo

January 9, 2016

Rainbow Snippets (9th January 2016)

Another week, another six sentences for the wonderful Rainbow Snippets group on Facebook. This week, a different book. Here are the first, er, seven sentences of my upcoming supernatural romance, A Frost of Cares, a winter ghost story. Luke isn’t having the best day…

In a way this story begins with me standing by the window of my London flat on Boxing Day with a cricket bat in my hands, seriously considering smashing every bloody fucking pane of glass in the bloody fucking flat into bloody fucking shards. The thing that stopped me, in the end, was the handle of the bloody bat, wrapped in a fraying green grip. The end of the grip was peeling up, and that tiny imperfection, that little spike of lighter green, by being out of place, threatened to tear open the whole grip. Staring at it, I realized that I didn’t know whether the bat was mine or Danny’s.

Well, fuck, I thought. You’ll have to excuse the paucity of my vocabulary at this point in the story. Obviously I was drunk as the proverbial skunk, and several of its cousins as well, and I never was much good at talking about my (bloody fucking) feelings.

![FrostofCares[A]_headerbanner](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452427539i/17692274.jpg)

January 2, 2016

Rainbow Snippets 2nd January 2015

Happy New Year and welcome to a new Rainbow Snippets post. If you’ve missed it, this is a lovely Facebook group which encourages writers to post six sentences from a current or past work every weekend.

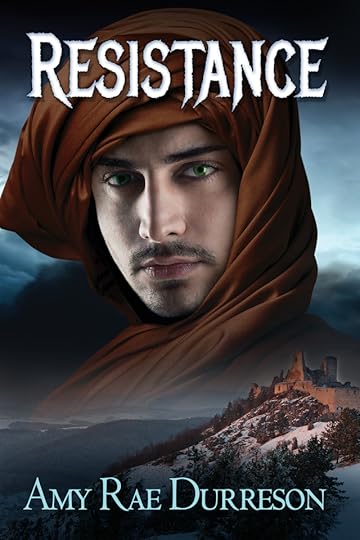

This week will be my last snippet from my new release, Resistance. Here is Iskandir’s first reunion with the lover he hasn’t seen for a thousand years…

All the hair on the back of his neck lifted at once, and his heart trembled. He wasn’t alone.

Every candle in the room suddenly blazed into light, flames flaring up in bright pillars.

“Iskandir,” Hal said, his voice taut with irritation, and held out his hand.

He could not resist. Shaking, Iskandir took two steps forward and fell into the dragon’s embrace.

DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 31, 2015

A Real Pest House, a Castle and the Canal in Winter

First a little reminder that I have a newsletter, and it’s going out later today! In case you missed it, I’ve also been talking about fantasy and sequels over at The Novel Approach. I’ve also been hard at work revising my Nanowrimo novel, current working title The Unslumbering Sea, though it may go back to Drowned Ghost Thingy again soon, because I’m not sure I like that. I am looking for a beta reader for that one, with one particular requirement: I need someone with a good ear for a Yorkshire accent who can tell me if my characters sound too home counties. If anyone can help, I would be very grateful. Lastly, here’s the actual subject of this post: another of my rambles, this one through the heart of Austen country.

On Tuesday, to distract myself from Resistance‘s release day, I went for a long wander through the Hampshire countryside. It was a beautiful day, more like April than December, and I was heading for Odiham, a large village by the canal a few miles north of Alton and Chawton, where Austen lived (there will a proper post about Alton in a few days, because I’ve been there recently too). Odiham is a charming place, pretty and quiet, and best known for its RAF base, which is the home of the UK’s Chinooks (we often see them in the skies around here). It’s about 15 miles further up the Basingstoke Canal than my home town of Aldershot, and a huge contrast from Aldershot’s rowdy urban setting. It also has something very unusual in its churchyard.

Here is All Saints Church. Yes, folks, this is December. If you look closely, you may even be able to see the Christmas tree on top of the tower which proves the date (it’s tethered to the flagpole).

And this is the Odiham Pest House. The pest houses in Resistance are of the urban, late medieval variety–large centres for the isolation and treatment of plague victims. The Odiham one doesn’t really fit that description. Built in 1622, it was originally intended as a poor house, for housing the most poverty stricken family in the parish. It was probably used for that purpose for most of its life, but from time to time it was also used as a pest house–an isolation hospital for any villagers or travellers with dangerous infectious diseases. Unusually, this one is in the centre of the village. Most were built on the outskirts and have since been demolished, often to have later cottage hospitals built over them. Odiham’s has survived, and is now a little heritage centre. It probably saw more cases of smallpox than plague. Its unusual location is thought to be partly because it was already conveniently located in the graveyard. (I was standing with my back to it in the previous photo)

Here is Odiham High Street, looking very bright and springlike. I’d been intending to walk back along the canal as far as I could before the light went, hopefully to Fleet and maybe all the way home, but I suddenly changed my mind. I’d never walked the last few miles of the canal, which ends just west of Odiham. Why not today?

And it was a good choice, because it was lovely, although muddy on the towpath.

These swans were gathering a feast from the bottom. This is a very quiet stretch of the canal, which starts off winding through the outskirts of large towns but slowly rises into the countryside between Fleet and Basingstoke. It no longer reaches Basingstoke and even the keenest boaters don’t come this way often.

This is Odiham Castle, built by King John between 1207 and 1214. It was from Odiham that he rode to Runnymede to sign the Magna Carta and he was besieged there for a few weeks in 1216. It later became the family home of Simon de Montfort, leader of the rebel barons in the Second Barons War. For a year, de Montfort ran England, summoning parliaments (he introduced a very rudimentary form of elected parliaments) until he was defeated at the Battle of Kenilworth. His wife was sent into exile and the castle became a summer retreat for later royals. King David II of Scotland was held under house arrest here for eleven years in the fourteenth century. Later it became a hunting lodge and eventually fell into ruin. The picture above shows all that remains. The canal cuts through what was once its outer bailey.

And here it ends. This is the mouth of the Greywall tunnel. Once this ran for almost a mile before the canal continued on to the large town of Basingstoke. It was so narrow that bargemen had to walk their boats through by lying down and pushing their feet against the wall. In the 1930s, the tunnel collapsed. The canal was no longer commercially viable, so no repairs were made and the last few miles on the other side were silted up and eventually built over. The old canal basin now sits below the bus station in Basingstoke. Today the tunnel houses several colonies of rare bats.

The last few metres, from above the tunnel entrance.

These cottages are in the village of Greywall. Never a huge place, Greywell has had a population of between 220-300 for the last two centuries. It’s an old place–in researching it last night I even discovered that the church here lost three of its vicars to the Black Death in 1349. Priests, like doctors, were especially vulnerable to plague, as they had contact with so many of the sick.

Here is the war memorial. The Kellys Directory of 1911 states there were 272 people in the village in 1901, and it would have been a similar number at the outbreak of the war. My attention was drawn by the unusual design of the memorial. A bit of googling explained: it is only a few months old. Greywell never had a memorial, but recently applied for a grant to fund this one. It was dedicated on 11th November 2015.

The village website has a whole page about it, with information about the men named and others who fought in both wars. The men’s biographies are under the documents tab.

Here is the churchyard of St Mary’s, the little village church. I had veered from my planned path at this point and had no idea what to expect around the next corner (the maps said “springs.”)

I found the upper reaches of the River Whitewater. Although it was midday, the winter sun was low enough that I could barely see as I made my way along this walkway.

Looking back from a little further along the river. At this point I was so far from my planned route I had to backtrack, once I’d finally located a bit of ground where the mud wasn’t too deep to sit on my coat and wolf down some lunch.

So up the byway I went, and the weather turned as I did. This is what I think of as proper Austen country–low hills, walking despite the weather, and green everywhere.

That byway took me to a hilltop and then I came down the lane on the other side. As you can see by the shiny road, it was raining on me. I kept walking out of the edge of the cloud and never faced worse than a shower, which just added to my secret conviction that there had been a time machine slip-up and I was really in April.

The lanes eventually led me to the outskirts of Basingstoke. This is the tithe barn in Old Basing, which was closed to visitors (perils of impulsive route changes). It’s part of a large complex including the ruins of Basing House which Parliament spent 24 weeks besieging into a heap of rubble in 1645, during the English Civil War.

All that was left was the footpath into the town centre, which branched off this marvellously named road, which beat out the hamlets of Blounce and Golden Pot, both on the Alton to Odiham road, for my favourite place name of the day.

By this point, the sun was so low these teasels seemed to be glowing. Within twenty minutes, I was at Basingstoke station and by the time my train came it was dark. It was a very pleasant day’s walking. I do love the ones that have some history mixed in.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 28, 2015

Meet the Resistance: Nuray

And here is the last of my introductions to the cast of Resistance. After the more intense introductions, this one is all about booze and fire :) The book is out tomorrow, and I’ve got a busy day. I’ll be over at The Novel Approach taking part in Carole Cummings’ regular Genre Talk column, and I’ll be taking over the DSP Publications twitter feed for a live chat between 6pm and 7pm EST (11pm-Midnight GMT).

With no further ado, here’s Nuray…

Summer 1022, the Gansa Pass, southern Tiallat (two years before Tarnamell’s rising)

“What’s the strangest thing you’ve ever set on fire?” Raif asked dreamily. He was sprawled above Nuray on the hillside, the wine bottle hanging from his hand. He looked as if he was about to melt into dry ground, and she sympathised. Even up here, under the vast wheel of the sky, the rocks were still carrying the heat of the sun. The air was warm against her cheeks, and would be until summer broke apart at the solstice. Despite the heat, though, it felt good to bare her face under the stars.

Raif hiccuped.

Nuray took the wine from him before he spilled it, took a swig herself, grimacing at the bitter tang of it, and passed it on. “I’m sure the Dual God doesn’t approve of boys who chase compliments, Raif. We all know you like burning things.”

“The Bright Lord loves fire,” Raif argued, propping himself up on his elbows to squint at her. “And I meant it. I want to know.”

Iskandir, perched cross-legged on a rock and gazing over the moonlit valley, heaved a sigh. “The Bright Lord loves sunshine.”

“The sun burns,” Raif argued.

“I burned my balls once,” Lev said, with a long sigh. “Hurt like fuck.”

There was a short silence as they all absorbed that, and Nuray thought dimly that it was a good thing the Savattin weren’t due through until noon tomorrow because right now they were all too blazing drunk to even stumble towards the fight, let alone pull off a successful ambush.

Raif, who she hadn’t bullied out of primness yet, shot her an agonised glance. Honestly, some men took their time learning to look past the fact she had breasts and treat her as what she was.

Stretching out her leg, she kicked Raif in the side, and said, “How the fuck did you do that, Lev?”

“Had to run out the back of that safehouse in Tirden—the one under the bathhouse, remember?”

Nuray nodded, and Iskandir said, “Hot stones in the basement, and a tight squeeze to get into the escape tunnel. You wouldn’t get through it, Raif. You’re too tall.”

Raif was still looking embarrassed, and Nuray took back her earlier assumption. Maybe it wasn’t just her part in the conversation. Boy might set a pretty fire, but he was a prude. All the same, he cleared his throat and asked hesitantly, “But why were you naked enough for, er, skin contact.”

“Well,” Lev said, his tone making it sound like they were all idiots, “it was a bathhouse.”

They contemplated that for a while and then Nuray said, quite honestly, “I can’t believe you’re not dead yet.”

“I’m lucky,” Lev said, clapping his hand to his chest.

Raif said, grabbing the bottle from him and passing it up to Iskandir, “No, but I hear the Dark God loves a fool.”

“Which is lucky for me,” Lev said comfortably.

Iskandir laughed. “And we are all the Dark God’s children, are we not?”

“God loves us,” Nuray said and leaned back against the rock behind her, crossing her legs. “Pass that bottle back, priest, before you finish it.”

“It’s his holy duty,” Lev said. “Drunkenness is only a breath from holy rapture, you know. And, whatever-whatever, the grape and the silver vine.”

Iskandir winced. “If you’re going to butcher poetry, I’d rather go back to Raif and his fire-starting tendencies.”

“It was beautiful,” Raif said, with a happy sigh. “All those poppies turning into flames. You should ask me to burn more things.”

Nuray laughed as Iskandir turned a dismayed face to them. She said, “If he turns the whole south to ashes, I shall blame you.”

“Like you’ve never burned anything?” Raif said, pouting slightly. They should get him drunk more often, though maybe not when there were any open flames around.

Nuray thought about it and grinned. “Of course I have. We all have.”

“So,” Raif persisted, “what about my question? The strangest thing you’ve ever set on fire. Not a body part, Lev.”

Lev snorted and took the bottle from Iskandir firmly. “A flour store. You wouldn’t believe how they go up. I worried it would just fizzle out, but it took out half the camp. Even set the air on fire, it looked like. Scared the piss out of me.”

Nuray, who had grown up in a small farming village, groaned. City boys, the lot of them. “If you’d known what you were doing, I’d be impressed.”

Lev shrugged and took another swig, grimacing. “This stuff is rough. You sure it’s wine?”

“Black wine,” Nuray said. “It’s a local delicacy. Reckon they usually cellar it longer, though. Hard to keep it long when your cellars might be searched.”

“They’re lucky the Savattin haven’t burned the vines,” Iskandir said grimly.

Raif cut over him. “How do you know that?”

Nuray shrugged. “People talk to me.” She didn’t add the rest of the story, the reason why so many of the resistance’s helpers looked at her and confided their secrets. It was a rare place where she didn’t hear, my sister walked your road, before the Savattin took her, or, I had a cousin once, but he is dead now. They strangled him with his own veil. Even, sometimes, I would have taken your road, in another time.

Dead, vanished, whipped, raped: the women who walked the Man’s Path were no longer safe in Tiallat. Their brothers on the Woman’s Path died too or were forced into an army they hated, to handle weapons that repelled them.

In another time, she would still be in her village. The baker’s daughter would simply have become the baker’s son, and only those who had known her since childhood would have known she was born to another path. Now, though, she wore her difference as proudly as she wore the man’s cap over her shorn hair, and her man’s shirt over her breasts—in another age, she would have bound them, becoming what her heart knew was true, but not now, not in this age where showing your difference to the world was as pure an act of defiance as setting alight a poisonous crop. She wanted them all to see her, and know that the Savattin way was not the only way.

One day, when her country was free, she could rest and simply be the man she carried in her heart, her true face. Not yet, though, not when she could still only bare her face amongst the company of these men, only under the gaze of the moon.

“I burned a bridge once,” Iskandir said, and she shook herself and pulled her attention back to the conversation. Brooding would make no difference, and she could at least enjoy good company tonight, in the company of her sworn brothers.

“Nuray?” Raif asked. “What did you burn?”

“My veil,” she said, smiling at the stars. It was a good memory.

“That’s it?” Lev asked, sounding disappointed.

“Ask her where she burned it,” Iskandir said and she grinned up at him. Of course he knew this story. He had a knack for knowing everything, that one.

“In the village square,” she said, remembering the gleeful crackle of that flame. “Well, on the steps of the Savattin temple, to be precise. On the anniversary of the Fall of Taila, during the Savattin’s festival.”

There was another of those startled silences and she laughed into it, relishing the memory. That had been a good day.

“And you say I’m lucky to be alive,” Lev grumbled.

Nuray shrugged and took the wine again, drinking to the memory of a very good day. “I think we should answer a new question.”

“Oh?” Iskandir sounded amused.

She sat up, grinning at them all. “I ask you this. Forget what we’ve already done. Those are old stories. Tell me instead—what shall we burn next?”

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 27, 2015

Meet the Resistance: Durul

And here is another of the main cast of Resistance. Keen-eyed readers of Reawakening will have met him very briefly before. He’s just a simple army surgeon (or so he keeps failing to convince people)…

Summer 1021, Esra Valley, Western Tiallat (three years before Tarnamell’s rising)

The crates of medicine were sealed with red wax, the symbol of the Fist of God stamped into them. They had arrived at the army camp in the back of a wagon driven by a surly fellow with mismatched green eyes below his red headscarf. He sighed impatiently when Durul insisted on breaking the seal and checking the cargo before signing off on the delivery.

Durul said crossly, “Stop delaying, man. I have far more important things to be doing. Some of us have patients to care for and—”

“Yes, we all know you’re a very important man,” the driver said, the sarcasm audible even through his heavy Rulati accent. “The seals aren’t broken. The cargo is fine.”

“Medicines are extremely delicate,” Durul proclaimed, aware of the crowd starting to gather to watch the show. He had established quite a reputation in this little encampment in the three months he’d been assigned here. “Not that a yokel like you would understand. You can’t just heave them around like the sheep you usually herd.”

“Haven’t touched them since they were loaded,” the driver said and offered Durul his knife. “Go ahead and check them, though, if you’re so worried.”

Durul cut the strings on the first crate and snapped the circle of wax. He pried at the lid of the crate, making sure to be clumsy with an actual weapon. That got him some derisive laughter (idiots, clearly, the lot of them , because what made them think a surgeon couldn’t turn a knife to his advantage), and the driver came to aid him with exaggerated helpfulness.

Inside the crate, bottles were racked up neatly, with rolled bandages and parcels of dried herbs stuffed between them for protection. It looked like every delivery of medicines Durul had ever received. He reached out to grab at one of the bottles—seven up, six down, he reminded himself—and pulled it out to hold up to the sunlight. The light shone through it, making the glass shine green as the spring. Durul nodded to himself, wondering if it would be too much to click like a fussy hen, or the elderly, long dead professor he was borrowing these mannerisms from.

He uncorked the bottle and sniffed it carefully, before freezing and then repeating the action. The next step was to taste the stuff, and he poured a little into the palm of his hand and sipped it up.

Cold, stale tea.

He did not have to feign disgust as he flicked the last of it off his hand. “What is this?”

“Medicine,” the driver drawled, rolling his eyes. “Thought you were a mighty clever surgeon, but if you can’t recognise a simple—”

“This,” Durul said precisely, “is not medicine.” He swung on the crowd. “You! Get the commander immediately!”

The driver had gone still, all the laughter vanishing from his eyes. “It’s medicine! They told me in the capital what it was. If this is meant to be funny—”

“Be silent,” Durul snapped and thrust the bottle into his hands. He pushed past the suddenly frightened looking driver to grab one of the packs of herbs—immediately left of the bottle he had already taken—and ripped the cloth bag open to sniff it. “Dry grass! Where are my medicines, man?”

The driver started to argue, but Durul was too overwrought to listen (or, at least, he tried his best to seem so). The camp commander arrived into the midst of the argument and Durul thrust the bottle and bag of leaves into his hand as proof that his medicines had been stolen.

That provoked even more of an outcry, and the driver came within a hair’s breadth of being arrested before he managed to convince the commander that all he had done was collect the parcels—he’d never opened them, look at the seals, sir, and if any change had been made it had been in the capital, before he took charge of them.

Everyone agreed that the capital was full of thieving bastards, but the commander still eyed the driver suspiciously. “You could be one of these traitors to the Fist?”

“Them!” the driver said vehemantly. “They got my brother killed, fighting against the Fist. I wouldn’t even spit on their graves, sir. I’m a loyal servant of the true god, I am. I would never trust one of those traitors who try to overthrow the rightful—”

“Fine, fine,” the commander said, as Durul caught his breath in irritation at that needless twisting of the truth. “Oh, do shut up, now.”

“I’m an honest man. I deserve to defend myself. I never—”

“You’re a lying thief!” Durul interjected, reaching forward to seize the driver’s shirt in his fists. “I ought to—”

“Both of you, silent!”

They both shut up, turning to look at the commander. He scowled at them both. “Surgeon, you are sure there is nothing useful here?”

“Even the bandages are motheaten,” Durul said, keeping his tone acid. “There is nothing here but rubbish. You may as well burn it, but it’ll cast up a stink.” He glared at the driver again. “Which might be somebody’s idea of a joke.”

“I never touched your fucking medicines.”

“All right,” the commander snapped. “We believe you.”

Durul muttered, but didn’t argue any further. The commander drew him aside. “Have you checked all the crates?”

“Not yet, but I will. I doubt they’ve left us anything of use.”

“How does this effect us?”

“Nothing to treat dysentery,” Durul said. They’d already had one outbreak this summer and were all braced for another. “Nothing to reduce a fever or put a man out of his pain.”

The commander groaned. “The strategic implications, alone… Oh, never mind that, surgeon. We all know that you only care what happens in your infirmary.”

“That’s what I’m paid for,” Durul said.

“Yes, it is.” The commander swore again. “Check the other crates. Keep anything which can be used and send the rest back to Taila with that idiot. Perhaps they can make sense of it.”

Durul did as he was told, loudly and publicly declaring the entire load unusable. He could hear the murmur of voices behind him and knew the rumours would already be spreading through the Savattin camp, lowering morale.

Good.

At last he declared the whole lot useless and sent the driver off with a further exchange of insults. Then, his hands shaking, he retreated to his infirmary and sat on one of the low beds, covering his face with his hands.

Dark God help him, he was not made for lying.

Much later, after the noises of the camp had settled to a low, disconsolate murmur and the light started to fade through the long summer evening, he made his way out of the back of the camp, carrying a bottle of cheap wine as an excuse. The Savattin didn’t approve of such indulgences, but no one was going to begrudge him a drink after this loss.

He found a place to sit on the mountainside well above the camp, beside a tumble of jagged boulders. He wrenched the cork out of the wine with his dagger and took a hearty swig, making sure to spill some on his clothes. It tasted like warm vinegar, but there was a pleasant rush to it. For a moment, he was tempted, but then he shrugged and poured the rest of it out in the shadow of the rocks.

From behind the boulder, the man who had driven the cart said, voice soft with laughter, “Not saving any for me?”

“Goat piss,” Durul said. “You’d never let me forget it, and then it’ll be ‘that time Durul gave Iskandir bad wine’ from everyone for the next five years.’”

Iskandir laughed, low and soft, and then said, “The cargo is away and clear. Did any of them suspect?”

“No,” Durul said, staring out across the bone dry valley to the bright sky. “I don’t think I can do it again.”

“I won’t ask it of you. We needed to divert attention from the previous route, and the clerk who handled the order back in Taila really is a Savattin loyalist. I hope he appreciates being interrogated by them as much as he liked the advantages they gave him.”

Durul shrugged. It had been necessary. The resistance struggled desperately for supplies and medicines were tightly controlled by the Savattin. Theft was the only way to get them, and now a whole wagon full of excellent medicines, ones that he himself had just declared fake, would make their way into hands that needed them.

It still didn’t sit easy on his conscience.

“There are patients in my infirmary who will die for the lack of those medicines,” he said.

“Savattin supporters,” Iskandir said, his voice carefully devoid of judgement. That was a test of Durul, he knew. Iskandir understood compassion, although he never let it sway him from his purpose.

“Men, still. Some of them were frightened into this army.”

“You are not to blame for this. The Savattin rationed medicines first. We are just restoring some balance, making things a little less unfair.”

“Much comfort that will be to the next boy who lies screaming because I have no poppy juice.”

Iskandir sighed and said, his voice soft and comforting, “You may lay it on my conscience. It was my plan, my order, God’s test for me.”

“Tests come in many forms,” Durul said, pondering it. “My teachers said that in medicine there is nothing but the patient in front of you. You must simply preserve that one life, one life at a time.”

Iskandir shrugged. “I am a man of God, Durul. My patient is the whole nation, and without your medicines, that patient will suffer longer.”

“Priestly sophistry,” Durul said with a snort. “Me, I’m just a simple man—”

Iskandir laughed.

Durul accepted the mockery with a shrug, and breathed a little more freely. “I am committed to the cause,” he said quietly. “It is just that my conscience troubles me, from time to time.”

“It is not a season for conscience. We have to be free first.”

Durul shook his head. “Rather the opposite, I would think. The measure of us is the choices we make in desperate times.”

“Maybe you should be the priest.”

It was Durul’s turn to laugh. “I’m just an old army doctor. What next?”

“We leave you alone for a while. This was a risk and we’ll not compromise you again too soon. How much longer do you think you’ll be here?”

“Another month or two, at most. The commander dislikes me.”

“When he sends you back to Taila, look for the carter at the crossroads in Silran. He’ll have forget-me-nots pinned to his headscarf and will take you where you’re needed.”

“Is there a story prepared for me?”

“Bad meat at the inn. You will be bedbound for four days.”

Durul nodded. These transits from unit to unit were the only chances he got to treat any of the resistance, who needed his skill so much. “I’ll be ready.”

“God loves you, Durul,” Iskandir said and then, without further ado, he was gone, fading back into the mountains and the dry, bright light of summer.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 26, 2015

Rainbow Snippets (26th December)

Happy Boxing Day, everyone. I’m between Christmasses two and three (Christmas Day with my parents and brother, today visiting all the grandparents, and my sister and small nephews on Monday). Handily enough, my quiet day coincides with a Rainbow Snippets Day, so have another little bit of Resistance (due out on Tuesday, eep!). This is about six weeks after the rats start dying and from one of my favourite chapters, as the plague grips the city of Taila.

Taila was turning white, the snow falling in a lazy, threatening dance. The air was hushed, as if even the tears of the dying had frozen.

In the street below, he heard the creak of wheels, the thin snow groaning beneath the weight of a cart. At the horse’s head, its driver rang a slow bell, his voice drifting up through the quiet.

“Bring out your dead!”

Hearing it, Iskandir realized that he could no longer hear rasping breaths from the bed behind him.

A bleak midwinter, indeed.

Pre-order from DSPP Amazon.com Barnes and Noble OmniLit Google Play

©Amy Rae Durreson 2015

December 24, 2015

All the joys of the season to you all :)

Merry Christmas to all of you who celebrate and happy holidays to everyone, however you are marking the turning of the year.

Here is my favourite Christmas poem. I’m not religious, but this one resonates for me, because it’s about the way stories linger and resonate with us throughout our lives. The poem was first published exactly a century ago, in The Times on Christmas Eve 1915. It must have been a terrible Christmas for many who read it then, but there’s a kind of quiet solace in the way it looks back to simpler times.

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

Thomas Hardy