Amy Rae Durreson's Blog, page 10

May 3, 2014

West by Rail (The Road Westwards, Part One)

It’s a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds’ cries;

I never hear the west wind but tears are in my eyes.

For it comes from the west lands, the old brown hills.

And April’s in the west wind, and daffodils.

‘The West Wind’, John Masefield

At the end of March, at the end of a long, long term, I closed my laptop, swung on my backpack, and went west. It had been a really challenging term’s teaching and I had been pushing myself hard to finish Resistance before I went away (something I failed at, as it took another fourteen thousand words, scribbled into the back half of my faithful travel journal, to see it through). I was exhausted, and somewhat reluctant to leave so much work behind me untouched, but my tickets were booked and I knew there were new places ahead of me.

My journey began properly at Bishops Lydeard, just outside Taunton in Somerset, and ended two weeks later as I boarded the train home from St Austell in Cornwall, about 100 miles to the southwest (my particular route was about twice that length). I was in Bishops Lydeard, a rather nondescript village outside Taunton, for one reason only.

I had a train to catch.

Bishops Lydeard is the eastern terminus of the West Somerset steam railway, which stretches across 20 miles to Minehead on the Somerset Coast. The railway dates from the 1860s and 1870s and was closed in 1971. It reopened as a heritage railway five years later. In the days when most people went on holiday within the UK and travelled by train, it was a busy and bustling line. It still is, of course, but these days people come for the trains themselves rather the destinations. Every year they hold a Spring Steam Gala at the end of March, where they bring in extra trains from across the country. I’d originally been intending to start my trip from Minehead and skim through Somerset quickly, but I can’t resist steam trains.

I didn’t reach the line until Saturday afternoon, so once I was there, I only had time to visit the museum at Bishops Lydeard, where they are busy restoring an old Victorian sleeper carriage which had my muses stirring speculatively. I chatted to a chap who was trying to sell copies of his memoir of behaving badly as a railwayman in the 60s, and then boarded the last train to Minehead. The line’s a long, lovely roll between hills and along the coast, and I began to drift off. This was a problem because not only was I not staying in Minehead, where the train terminated, but for the weekend they had renamed all the stations after a different closed railway further west and I couldn’t remember what they were calling Dunster or exactly how far along the line it was (seriously, don’t do this if you own a heritage railway). Luckily, the guards, with one very young and keen exception, stuck to the original station names (or, as I overheard, “If I’m on a train to Minehead, I’m on a train to blooming Minehead.”)

I found myself in Dunster just as the day began to fade and made my way up the lane from the station in search of my hotel. The next day I had nothing to do but ride on steam trains. I was looking forward to it.

All along the line, the stations host little heritage museums, full of old pictures and railway posters, engine parts and signs, old signals and replica luggage from the tourists of another era. The quirkiest one I found was at Washford, the first I visited. It’s a very quiet little station, surrounded by green hills, which has somehow accumulated the remnants of more than one vanished railway. I bought my ticket, inspected the room full of signal equipment and chuckled over the disciplinary records of a couple of Victorian railwaymen that were on show, and then wandered across the line to explore the carriages in the sidings. They contained the museum of the Somerset and Dorset Railway, a line which ran nowhere near Washford, but had ended up here by some strange quirk of the preservation and heritage world. I had the place almost to myself, except for a beautiful peacock butterfly fluttering around the coal bunker inside one of the carriages. Among the miscellany, I found the place where old railway signs go to die.

A visit to the preserved signalbox from Burnham-on-Sea, and the tiny preserved locos of an old peat railway, now tucked away under a shelter on mossy tracks , finished my visit to Washford. I caught the next train back in the other direction and continued my scheme to visit as many stations and museums as I could.

At Blue Anchor, I had time to wander down to the beach and gaze down the coast at the misty cliffs. I knew there would be cliffs later in my trip, though, and not many more steam trains, so I went back and waited for the fast train out of Minehead. I knew that there was a museum at Williton and it was next on my list. I was even more delighted when the train drew in, because I found myself meeting an old friend.

Not a human friend in this case, but a mechanical one: the train was pulled by Wadebridge, who normally resides at my local heritage railway, the Watercress Line. She was originally used on railways in the west country, but now lives in the quiet Hampshire countryside. Whenever I’m hiking around the Watercress Line, it seems to be Wadebridge I catch sight of at the beginning or end of my walk and I have a soft spot for her. It was nice to see I wasn’t the only one enjoying a few days out at the seaside.

At Williton, I got chatting to a engineer, who was sitting outside his engine shed waiting for a willing audience. I’m not as fond of diesels, being more of a fan of the romance of steam, but he argued passionately that the earliest diesel trains were antiques that deserved to be valued as a vital part of our industrial heritage. I spent a little more time in the two tiny rooms of the heritage centre as a result and had to admire this lady, who was clearly one of his pride and joys (I also was quite gleeful to be able to climb into her cabin and indulge the childhood dream of being a train driver for a moment or two).

Back on the train, I finally made it to the end of the line. I had a bit of shopping to do in Minehead, and wanted to hunt down the bus stops for the next day, but I also got to coo at a few more trains (hush, you mocking fools, my grandad was a railwaymen, my dad took me trainspotting when I was three, and I have two tiny nephews who are carrying on the tradition with wide-eyed joy. It’s in my blood).

And here below is Wadebridge, on the turntable at Minehead. She’s a West Country class, built during the war and nicknamed ‘Spam Cans’ for their shape (I’ve heard various explanations for the boxy profile: possibly rationing of materials, managing exhaust fumes, or being cheaper to clean). As steam trains go, she’s a powerhouse, though. At the time she was built, everyone knew electrification was coming, but they needed cheap, tough efficient steam trains to fill in until it happened. She was hauling the express trains all day Sunday for good reason.

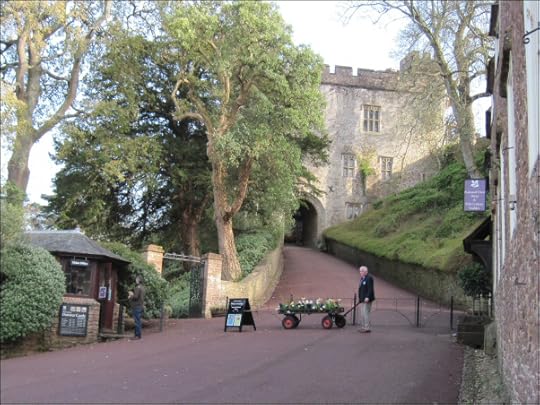

I hopped on a train back to Dunster and lingered on the station once I got there to see one more go through. Then I reluctantly turned my back on the line and went to explore the place where I was staying. Dunster is a very old little town, that once prospered from the wool trade. It’s just on the edge of Exmoor, at the point where the land begins to rise away from the coast, and has a castle. I didn’t go in, because they were just closing up as I got there, but I did spend a while wandering the medieval streets quite happily.

The sun had been out all day, but now things began to turn a little dull. I went to find the old bridge, which I’d read was of historic significance. I admired it dutifully, tried to climb the hill beyond to find a view, but got tired so trotted back to explore the rest of the town and then have an early night.

The next day I caught the bus into Minehead, where I had breakfast by the sea, and then I headed west again on a very small, very rattly bus which went up some very, very steep hills. Porlock Hill, the steepest of them, is set with exit roads for motorists to aim for if they lose control of their cars. We went up it, but I was very conscious of just how much my elderly driver’s hands had been shaking as he took my fare (Wikipedia informs me the road climbs 1300 feet in 2 miles. It also has hairpin bends). My mother tells me that she and my dad once came down it on an open top bus, so she wins this one, but it was still quite a bus journey.

I was aiming for Lynmouth, a little village just over the Devon border. It’s a quiet, pretty little place, with a harbour and two rivers which tumble down steep gorges. In the picture, and on the day I was there, the rivers looked benign, but in August 1952 a freak storm triggered a flood down the river which destroyed over 100 buildings. 34 people died and over 400 were left homeless. It wasn’t the last flood story I would meet on my travels, but it was the grimmest. There are many reminders of it in the village, but they also celebrate a much more inspiring story.

On January 12th 1899, the ship Forrest Hall, carrying thirteen crew and five apprentices got into trouble off Porlock Weir. A gale was blowing, her tow rope was broken, she was dragging her anchor, and her steering gear was broken. The signal went up for the Lynmouth Lifeboat, but the gale was so strong she couldn’t launch.

Instead, the coxswain of the boat proposed that she should go overland and be launched from Porlock’s more sheltered harbor. To do this, they would have to drag her up the hill out of Lynmouth (a mere 1 in 4 gradient), across 13 miles of clifftop and then down Porlock Hill. To make things worse, the roads were too narrow for the boat, so six men went ahead with pickaxes to widen them and then they went straight across the moor. It took 100 men and 20 horses (four of whom died of exhaustion). To get down Porlock Hill the men had to steady the boat with ropes as the horses pulled it. They also had to demolish a garden wall and cut down a tree on the way down. It took almost twelve hours, in a roaring gale, and the crew then had to row for an hour to reach the ship.

They took the entire crew off alive.

In the shelter under the Flood Memorial Hall, there were numerous newspaper accounts of a reenactment which took place on the centenary, where everyone involved mentioned how challenging it had been to do on a nice summer’s day on good modern roads. Every time I visit the coast, I hear stories which leave me humbled by our lifeboat crews, both past and present.

I left Lynmouth by another type of railway. 700 feet above the village, on top of the cliffs, stands its larger sister village of Lynton. To reach it, you can climb a steep path, go round a very long way by road, or simply take the cliff railway.

It was opened in 1890 and has been running ever since, and is water-powered. As you rise up, you can see back along the green and towering cliffs. On the day I was there, the air was dull and mist still clung closely to the horizon.

At the top, I paused for a quick lunch and then turned my back on railways. I would now be travelling by bus and boat (and one car, but that’s another story) all the way to Newquay. The next bus took me to Barnstaple, where the grey day darkened further and distant rolls of thunder suddenly turned into torrential rain. I caught a packed bus through the rain to the port of Bideford on the Torridge Estuary, where I got hopelessly lost trying to find my hotel. Once I was in, though, the weather began to clear, and I looked out over the estuary with growing excitement.

The next day it would be April, and I was going to Lundy.

(To be continued, obviously…)

March 16, 2014

Plague pits and haunted woods (photos)

*waves quickly* I’m still alive here. I’m pushing hard to finish Resistance before I go away at the end of March, which is looking increasingly like an impossible task (I’m less than 70% done). That said, I’ve made good progress over the last few weeks. I’ve rewritten all of the chapters I chopped out a month ago and more. I’m deep into the bleakest stretches of the book which I’m increasingly realising isn’t really a romance. It’s about redemption, as much as anything and the love story is just part of that. It’s an essential part, because Iskandir has to struggle to realise that he is worthy of love again, but it’s not the main story.

Here, just as a quick little Sunday snippet, is where he and I are right now:

The meadows where midsummer fairs had stretched out in rows of bright pavilions were gone, as was the quiet place by the river where Cezmi of Salma had met his end only a month ago, his hands cradled in his god’s. Now the ground was torn and pitted, the dark earth showing through the thin snow. The pits stretched out like the marks of vast claws, long, thin and deep. The Dual God rode with the cart to the side of one of them and watched as the dead went tumbling down into the wet depths of the earth. As soon as the last of them had fallen, another man came up, hefting a shovel and began to scatter some of the heaped soil over their tumbled bodies, sealing them below the earth.

“Are you coming back into the city, Lord?”

“Not tonight,” the Dual God said. The digger beside him was not the only one working amongst the graves. He hadn’t thought that there was a worse job than transporting the dead, but here it was. He would stay here until he had put his strength and resistance to good use.

He walked through the burial ground, picking his way between the crumbling edges of the pits and fires built between them, which offered the only dim and flickering light to move by. The air was full of ash and shadows, and the distant voices of the drivers and diggers exchanging comments seemed as thin and faraway as ghosts.

He came around the corner of a mound of excavated soil to find a lone man digging out the end of a pit, extending it further from the city. No one else was in sight, and the Dual God paused for a moment to watch him. He was moving slowly, with the loose heaviness of exhaustion, but he did not hesitate. One spadeful at a time, he dug out the heavy soil, heaving it out to add to the dark pile behind him. Only when the pit got deep enough that he needed to stoop right over did he hesitate, clutching his back as he straightened with a groan.

“Give me your spade,” the Dual God said, stepping forward.

I’m rather enjoying it, in a slightly grim way. Of course, it also has its disadvantages. I decided to walk home from work along the bridleways on Friday, which in retrospect was a bad idea, as I ran out of daylight miles from town. Luckily there was a beautiful bright full moon to guide me through the last stretch until I finally came out on the main road and all the subtlety of the night was lost to the glare of sodium and headlights.

There’s one short stretch of that route which is the only footpath in ten miles which ever unnerves me. It’s one of the very, very old paths we have around here, that runs along a sunken track through the pine woods above the ruined abbey. Even in the height of summer, the wind sighs through those woods. I got there later than I wanted on Friday and was just into the really creepy stretch when I blithely thought to myself, “Hey, should you really be thinking about the plague dead as you walk through the ghost woods at dusk?”

I have never walked that stretch of path so fast in my life XD By the time I got out onto the lane at the end, the hairs on the back of my neck were on end and I didn’t have the nerve to look behind me. Even worse, the moment I stepped out onto the verge of the lane, most of the fear just seeped away. I didn’t shake off the last of the creeps until I was half a mile down the next path, up between the witch’s cave and the moonlit swamp (which was also the point when I decided to distract myself by imagining Emyr and Heilyn’s wedding instead of plague pits). I really need to write a happy story soon.

Despite that, it was a pretty walk. I put some of the earlier photos up on Facebook, but here’s a few here as well. This route home takes me 2-3 hours so it’s a Friday treat in summer, but I love it, creepiness and all.

March 3, 2014

I must go down the sea again (Image heavy)

Last week, I risked the weather and went away from a day. After a stinker of a term, and mid-battle with a book that just wouldn’t cooperate, I needed a break, so I took the risk of booking two nights in a hostel down in Swanage on the Dorset coast and crossed my fingers and hoped neither the town or the route there would vanish under the rising floodwaters.

Miraculously, the heavy rain forecast never fell and I arrived in Swanage just before dusk. It’s a little old Victorian seaside town built along the back of a deep bay in the chalk cliffs at the eastern end of the Jurassic coast. Its main industry is still tourism and the beach is busy in the summer. In February, it’s a much sleepier place.

The next morning I woke up early and took my breakfast with me as I wandered along to the end of the bay. Here’s the view from the bench where I had my breakfast. Many a ship has met an untimely end on the reef below.

Wandering back down towards the beach, I found this old cafe which is being renovated.

The high street gives a hint of the town’s Victorian heyday. This is the town hall and the Grand Hotel, if I remember correctly.

Swanage does have one tourist attraction which does open in February, and by mid-morning I was aboard a steam train, heading inland for the village of Corfe Castle. The castle itself was the stronghold of bad King John in the middle ages. By the English Civil War, it had passed out of royal hands, but still belonged to royalists. It was the last stronghold of the Royalists in the southwest and Parliament’s siege only ended when an insider was bribed to open the gate. The lead defender was the redoubtable Lady Mary Bankes, wife of the owner, who had been sent away to serve the king in the north. She stayed in the castle with her daughters and five men (although they were later sent another 80 to help garrison the castle). They held off two sieges and when Lady Mary was finally ousted she was allowed to take the castle keys away with her to her new home.

The castle itself wasn’t so lucky. Parliament ordered its demolition. Charges were planted below the walls, rendering the place indefensible. It’s now an absurdly picturesque ruin, with its walls slanting out in all directions and its crumbling towers visible for miles.

The steam trains run right below the castle walls and the station is the epitome of an old-fashioned English country station.

Back in Swanage, the sun had come out enough to sit by the beach with my book and read the rest of the day away to the sound of the sea, watching small children run along the sand clutching ice-cream cones in their gloved hands (it is England after all).

February 24, 2014

The Author Died in 1967

Which author, you may ask. The Author, I’ll reply, because 1967 marked the publication of Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author. It’s one of those essays that everyone who studies literature beyond a certain level has to read, and I’m sure some of you are already edging for the door, because it’s a mean bastard of a thing. It’s also one of the most important things written about literature and the processes of reading and writing in the last 100 years. It’s important, especially for those of us who are actively engaged in the processes of reading and writing, not just because of the way it challenges assumptions about writing which still persist today, but because it offers some valuable insight into the nature of authorship, which is an increasingly complex identity in itself. It also explains why being an arsehole to reviewers is philosophically unsound (yes, I have been watching the latest Goodreads shitstorms, hence this post).

Have I scared you all off yet? No? Good. I’m going to keep it fairly simple, at the level I’d use to introduce these concepts to my classes. If you do know anything about literary theory, you probably should leave now, because this is going to be reduced down to its barest bones (sorry). Barthes’ essay challenges the concept of the individual controlling author as the sole figure shaping and forming a piece of writing (a text). He challenges the idea that the most important factor in understanding a text is the personality and biography of the author.

The image of literature to be found in ordinary culture is tyrannically centred on the author, his person, his life, his tastes, his passions, while criticism still consists for the most part in saying that Baudelaire’s work is the failure of Baudelaire the man, Van Gogh’s his madness, Tchaikovsky’s his vice. The explanation of a work is always sought in the man or woman who produced it, as if it were always in the end, through the more or less transparent allegory of the fiction, the voice of a single person, the author ‘confiding’ in us.

This is a very narrow interpretation of any text, which views a piece of writing as a puzzle to be solved, with the author’s life and views providing the clues, like a traditional whodunnit. If we detach this idea of the author from the text, however, we’re left with something more interesting. Think instead of the writer as simply the conduit for the words, which are themselves woven together from the ideas and words that have come before them.

At first glance that seems mad. Think, though, of every time you’ve looked back over something you have created and seen something you didn’t put in intentionally, something which reflects the context you were writing in or makes an allusion to something you’ve read or seen or heard. The writer exists only in the moment of writing, weaving together a tissue of allusion and ideas and reactions into a new form. Once that writing process is over, the writer ceases to exist.

Somebody’s got to make sense of the product of this process, though, and that’s where the reader comes in. Instead of assuming that there is one authority on the text, the author who deliberately controls every detail of their creation, Barthes sees the reader as the one who creates meaning out of this mass of words and phrases. The author themselves will only have a limited perception of the text they have shaped, so to accept their interpretation of it as more valid than the reader’s massively limits the potential meaning of the text.

Thus is revealed the total existence of writing: a text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author. The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.

The reader, not the writer, is the end point of this process. Now, inevitably, this complicates things because every individual reader creates their own version of the text that they have read. The idea of the one central authority is undermined, because it isn’t the creator who is in charge of the text. It’s the audience. We can all present our own experiences as readers, but in doing so we are creating new texts of our own, which some other reader must make sense of it.

Okay, it was the sixties.  Mindfucks are obligatory.

Mindfucks are obligatory.

It may all seem very abstract, but the central point here is that the key figure in the process of literature is not the author. It’s the reader. Without a reader to create meaning from what we have put upon the page, we’re just empty noise. Shakespeare knew this (Shakespeare knew everything) when he described life as ‘a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury / Signifying nothing.’ The performance alone is meaningless. We need an audience (part of me always feel that this should be most obvious to romance writers, because we’re all about how having somebody to see you truly gives your life meaning).

When I first came across all this as an undergrad in 2000, I hated it and I didn’t understand it. Every authorly instinct in me rebelled against it. Of course I control my stories, I thought. Of course I’m in charge. I was eighteen. You’re allowed to be that thick when you’re eighteen. Since then, I’ve read a lot of medieval literature, which makes you question the whole modern notion of authorship and originality. I’ve read and written a hell of a lot. Most importantly, I’ve taught. There’s nothing like teaching to prove beyond a doubt that all readers have their own unique and valid responses to a text.

So, let me take you into my classroom (deep breath, please, it’s been a warm day and there’s a great heap of stinky PE bags in the corner). Let’s have a look at a poem by Grace Nichols. This is Island Man, which was a fixed point on the GCSE syllabuses until a few years ago.

Morning

and island man wakes up

to the sound of blue surf

in his head

the steady breaking and wombing

wild seabirds

and fishermen pushing out to sea

the sun surfacing defiantly

from the east

of his small emerald island

he always comes back groggily groggily

Comes back to sands

of a grey metallic soar

to surge of wheels

to dull north circular roar

muffling muffling

his crumpled pillow waves

island man heaves himself

Another London day

I always started the poetry section of the GCSE course with this poem. It’s straightforward in meaning but there’s lots of lovely stuff going on with the language and structure, so it’s a good opening lesson. One thing I did was to chop it up and give groups individual quotations to discuss and then present back to the class. One year, I taught two Year 10 (9th Grade) classes. There was a similar mix of boys in each class: middle of the ability range, some really difficult kids and a lot of steady plodders. When it came to the phrase ‘breaking and wombing’ the first class went in a predictable way: they told me that it suggested he felt safe in the island, that is was comforting and nurturing like a mother, that he maybe felt that he had to grow up and leave. All good ideas. Then came the second class, two days later.

“Miss, I think there was a civil war on his island and he’s a refugee.”

Okay. Then I got, “I think he hated it and wanted to get away. He had a really violent life there.”

O-kay. “And he felt really trapped inside there like you get trapped in the womb, and he wanted to escape like babies want to be born.” By now the whole class were joining in.

It was all interesting stuff, but somewhat unexpected. I’d been teaching the poem for years and never heard this sort of thing before.A few questions led me to an explanation.

In the intervening two days, my colleagues up in the Science department had shown them all a rather graphic video of childbirth. They’d found it rather distressing (all boys Catholic school). That experience had a huge influence on the way they interpreted the word ‘wombing.’

Their interpretations weren’t wrong. They could explain them with reference to the text and their own experiences. They knew why they felt the way they did and the poem had a greater emotional impact on them because of that different experience they had been through.

Was it what the poet had intended? Almost certainly not, but that didn’t matter. The impact that poem had on those boys was different and greater than the impact it had on their peers two days before. They constructed their own meaning from the interaction of the words and their experiences, and it was amazing.

That’s what we all do as readers. It’s pretty fucking cool.

To go back to Barthes, consider this: if the writer is only involved in the moment of writing, what are they before or after that moment? When they bring their own interpretations of the text in, they are no longer an author. The moment the author engages in interpretation, in the act of creating meaning out of what they have stitched together, they become a reader instead. Whether or not their reading of the text is any more valid than that of any other reader is a matter for debate. The author essentially dies the moment the writing process ends. After that, the text is in the hands of the reader. How many of us got frustrated when JK Rowling started revealing extra material in those post-book interviews? Many of us had an instinctive feeling that she was cheating somehow, that this wasn’t playing the game right. That instinctive reaction goes straight back to the relationship between the writer and the reader. In my opinion, once the writer has presented the text to us, their time is up. Piss off. Butt out. It’s the reader’s job to make sense of this thing. The author’s done their bit. You’re not the author of this book anymore. You’re the author of whatever you’re writing right now. The things you wrote once are like a snake’s discarded skins: lovely, but no longer part of you. You can only look in at them from the outside.

Oh, and since the Author died almost fifty years ago, staggering around the reviews of a past book trying to impose your reading onto its reviewers makes you an extremely manky zombie. Just sayin’

(Oooh, I think I needed to get that off my chest).

February 14, 2014

Happy Valentine’s Day (from me and John Gower)

Happy Valentine’s Day! I hope those of you who have loved ones are snuggled up warmly and safely out of the vile weather and those who don’t are spending a cozy evening with a good book, good booze, or another entertainment of your choice

Happy Valentine’s Day! I hope those of you who have loved ones are snuggled up warmly and safely out of the vile weather and those who don’t are spending a cozy evening with a good book, good booze, or another entertainment of your choice  I’ve been having a bit of fun reading this article about the medieval origins of Valentine’s Day: A Theft of Love: How Geoffrey Chaucer Stole Valentine’s Day From John Gower. As a loyal Gowerite, I was amused and gratified

I’ve been having a bit of fun reading this article about the medieval origins of Valentine’s Day: A Theft of Love: How Geoffrey Chaucer Stole Valentine’s Day From John Gower. As a loyal Gowerite, I was amused and gratified  Our boy doesn’t get much credit (even though he introduced the word ‘histoyr’ into the English language. That itself should qualify him for awesomeness).

Our boy doesn’t get much credit (even though he introduced the word ‘histoyr’ into the English language. That itself should qualify him for awesomeness).

For those who have no idea who I’m talking about, John Gower was a contemporary of Chaucer’s. There’s enough evidence left to suggest the two men were friends, including some decidedly snarky dedications of poems to one another. They were both at the centre of the late fourteenth-century revival of English verse which is the foundation of the modern English literary tradition. From this distance, it seems hard to understand that simply using English as a literary language was cutting-edge, but these two were engaged in a consciously European literary tradition that established English as a suitable language for sophisticated writing. They were courtiers, who relied on other income to support their writing (Chaucer was a customs official, among other jobs, and Gower was a lawyer). Both were well-known to royalty– Gower recounts how a chance meeting with Richard II by the Thames inspired his book, while Chaucer wrote a lament to his empty purse and then dedicated it to his neglectful patron, Henry IV. In the throes of the Hundred Years War, there was a politically-motivated demand for English vernacular literature which hadn’t really been seen since Alfred the Great started recruiting scholars to write in Winchester in the 880s. Gower himself wrote in the Preface of the Confessio Amantis:

And for that fewe men endite

In oure Englissh, I thenke make

A bok for Engelondes sake.

Gower, of course, wrote in more than just one language: he composed three epics in his lifetime, one in Latin, one in Anglo-Norman, and one in English. He also wrote ballads in Anglo-Norman. His English epic, Confessio Amantis, is his third work. Unlike his first two poems, which were moral polemics, this one is all about love. It’s a gleefully massive compendium of contradictory stories about love, organised around the seven deadly sins. Gower’s a less flashy writer than Chaucer, but his pared-down style contains a sly irony. He’s a supple and a subtle writer, who tends to be scorned as dull and worthy by Chaucer purists. It’s easy to miss just how lucid his style is until you try to break it down or reword it.

Hmm, I’ve slipped into teacher mode, haven’t I? This preamble started because I thought it might be fun to offer you a little taster of Gower’s poetry. Below I’ve translated the first sixty lines of Book 1 of the Confessio Amantis. I’m rather fond of this passage, and modernising it was a fun puzzle. I’ve stuck to Gower’s octosyllabic couplets, and have included the original and much better version afterwards. Do read it– it’s much lovelier than my version. As a romance writer, this is a passage I return to frequently.

Confessio Amantis, Book One, 1-60

I may not stretch up to the sky

My hand, nor make the whole world lie

Flat, that’s always held in balance:

I just don’t have the influence

To have such very great effects

So I will let it go, and next

On other matters, I’ll converse.

I’ll change the style of my verse:

From this day forth, I’ll start to write

Of things which aren’t so far from sight,

Which all living things have to hand,

Which whereupon the world must stand,

And has done since it first began

And will while there is any man,

And that’s love, about which I mean

To explain, as soon shall be seen.

In love, man may not rule himself—

Love’s law is unruly itself!

Blame, well, every man for giving

Too much (or too little) loving.

But nonetheless, there’s not one man

In all this world so wise he can

Pour perfect measures of passion:

Chance can add an extra splash on.

Wit and strength make no difference.

Claiming otherwise is nonsense—

You’ll end up falling on your face

And you’ll get no help back to grace.

No one’s bright enough, I’m sure,

To make a universal cure

For what God’s set as natural law.

Trust no man who dares to assure

He’s found the salve for such a sore.

It was, and shall be evermore,

That love masters what he chooses

And no living thing refuses.

For wherever love likes to pause,

No power can bind him with laws.

So, what shall happen at the last

But this truth, that no sage forecast,

That love falls upon us by chance.

If there ever was a balance

By which shares of luck were controlled,

I’ll just believe what I was told:

That balance is held in love’s hand,

Which reason will not understand.

For love is blind and will not see

And therefore may no certainty

Now be placed in his reasoning.

But, as the wheel starts to spin,

He rewards the undeserving

With prizes from the long-serving:

Love’s loyal servants lose the bet

Like a man playing at roulette;

Therefore, the lover does not know

Until the wheel lets it show,

Whether he shall lose or shall win.

And thus quite often men begin

Who, if they knew what true love meant,

Would change their entire intent.

John Gower’s original Confessio Amantis, Liber Primus

I may noght strecche up to the hevene

Min hand, ne setten al in evene

This world, which evere is in balance:

It stant noght in my sufficance

So grete thinges to compasse,

Bot I mot lete it overpasse

And treten upon othre thinges.

Forthi the stile of my writinges

Fro this day forth I thenke change

And speke of thing is noght so strange,

Which every kinde hath upon honde,

And wherupon the world mot stonde,

And hath don sithen it began,

And schal whil ther is any man;

And that is love, of which I mene

To trete, as after schal be sene.

In which ther can no man him reule,

For loves lawe is out of reule,

That of to moche or of to lite

Wel nyh is every man to wyte,

And natheles ther is no man

In al this world so wys, that can

Of love tempre the mesure,

Bot as it falth in aventure.

For wit ne strengthe may noght helpe,

And he which elles wolde him yelpe

Is rathest throwen under fote,

Ther can no wiht therof do bote.

For yet was nevere such covine,

That couthe ordeine a medicine

To thing which God in lawe of kinde

Hath set, for ther may no man finde

The rihte salve of such a sor.

It hath and schal ben everemor

That love is maister wher he wile,

Ther can no lif make other skile;

For wher as evere him lest to sette,

Ther is no myht which him may lette.

Bot what schal fallen ate laste,

The sothe can no wisdom caste,

Bot as it falleth upon chance.

For if ther evere was balance

Which of fortune stant governed,

I may wel lieve as I am lerned

That love hath that balance on honde,

Which wol no reson understonde.

For love is blind and may noght se,

Forthi may no certeineté

Be set upon his jugement,

Bot as the whiel aboute went

He gifth his graces undeserved,

And fro that man which hath him served

Ful ofte he takth aweye his fees,

As he that pleieth ate dees;

And therupon what schal befalle

He not, til that the chance falle,

Wher he schal lese or he schal winne.

And thus ful ofte men beginne,

That if thei wisten what it mente,

Thei wolde change al here entente.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Aunt Adeline’s Bequest is out now

February 9, 2014

Scything my way to happiness

(Warning: much blithering about my writing process below)

So, I finally broke past 60k on Resistance, finishing a scene I’d been stuck on for weeks. I also cleared the last of the crazy workload from my day job and relaxed enough to take a deep breath. I wrote all day yesterday, suddenly getting to grips with the main plot again.

And then this morning, all my concerns about this book reemerged. I’ve been feeling for a while that it’s just stretched too thin. The pacing is so slow it’s almost going backwards (pacing is always my issue), but at the same time the supporting characters felt undeveloped and the worldbuilding flimsy. Every time I glanced back, I realised I’d missed out a sentence with some key information that was needed to understand the plot. Instead of a carefully interwoven plot, I had macrame done blindfold in rubber gloves. Some of this was pure midnovel slough of despond stuff, but usually when I find myself writing more and more slowly it’s a sign that I’ve subconsciously recognized a major problem and I won’t be able to make progress until I fix it. Sometimes that issue is to do with whether a scene is necessary for the plot, sometimes it’s character or theme related. Often it’s structural, because I really like strong structures in everything I write.

Until now, I’ve been writing in alternating point-of-view, between Iskandir, the Dual God of Tiallat, and his lover the dragon Halsarr. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been idly thinking that the balance between the two characters is wrong. Iskandir has the stronger character arc. He has all the emotionally punchy scenes. It’s set in his country and it’s his people who are suffering. All Hal’s plots were in support of what was happening to Iskandir (who is the most infuriatingly twisty character I’ve ever written, even before everything goes to shit). I’ve been too buried in everyday stuff to think about that properly until today. But this morning, I asked myself, If I switched to only Iskandir’s pov and cut Hal’s completely, would the book still work?

There were a handful of potential plot issues, where the leads where parted. Apart from those, the answer was, it would be a better book.

So I’ve just removed ten chapters. Seven of the ten can be adjusted and rewritten in Iskandir’s pov, although that will involve massive cuts. That process, though, should let me deeper into Iskandir’s messed up head. It should give me opportunities to spend more time with the supporting cast, who are his friends, which means I might be able to make their choices look less moronic than they do right now (this was already top of my second draft to-do list). It will let me tighten the focus on Iskandir’s history and relationships to the people around him, which should enrich the book.

On the other hand, I shall regret losing Hal’s perspective, because he’s delightfully dry and snide, but has a lovely long perspective and real compassion. I was having fun writing a pacifist dragon, but his perspective became less and less central the further I got into the book. A character arc of endure your lover’s pain might be true to life (been there, lived that), but it doesn’t drive a plot particularly well. On the plus side, I’ll have a wealth of missing scenes to post at a later date. The bit I shall regret the most is his first three chapters, which can’t be rewritten, because he and Iskandir are a thousand miles apart in this section. It’s full of pretty bits, though, and although I know you have to kill your darlings, it stings when it’s for a structural issue rather than because they’re just extra frills.

However, I now feel so much happier about this book. For the first time in months, I’m excited rather than panicky, so I know this was the right call. It’s going to have a knock-on effect on when I finish, but I’m confident it will be a better book for the change.

I’ve been going through those three lost chapters of Hals’ perspective, trying to work out what missing information I will need to compensate for elsewhere, and I found this description of the last battle at Eyr, which I thought some Reawakening readers might appreciate before it disappears into my archives.

Hal watched the sunset from his tower, with a glass of wine in his hand. It was rich stuff, and usually he lingered over it, enjoying all the sensation and pleasure that even a small indulgence would grant this body. Today it tasted like ashes, and the darkening skies over the mountain brought no comfort. It was hard to be comforted by nature when his heart was cold.

This was not new. There were nights, although less now than when he had first woken, when the memories surged over him. He knew they had him tightly in their hold now, and he could not stop the grief. He would live through it, as he did on all these dark nights, enduring it until the wave passed over him and he could breathe freely again.

There were tears on his cheeks, like the brush of falling water, and he breathed slowly and stared at the sunset. A thousand years ago, he had looked down on the field of Astalor like this, from outside tents already overflowing with the wounded and dying, and seen the Shadow come out of the towers of Eyr, darkness folding across the sky until the only light of the field was the eerie glow of magelight and the flames that dragons raised. It had been just light enough to see his horsemen rushing towards the darkness though, the dun flanks of their horses gleaming golden under the flames in the sky, the riders crouched in their saddles, sabers raised. He had seen the way the Shadow suddenly took form in the darkness, a clawed and spiny horror as vast as a dragon, right in the path of the charging horsemen.

They had ridden right into the Shadow’s wrath, his brave riders, and Hal had felt his heart tear as the Shadow ripped the lead rider from his saddle and shredded him as the horses screamed with fear.

He had students now who had been to what remained of Astalor and seen the flowers growing on the battlefield, roses blooming out of old bones. Hal would never make that journey, not until time ground the mountains low and made the rivers run along new paths. He could not look on Astalor again.

February 1, 2014

Dragons and chocolate (do not normally mix)…

So, Reawakening has been out for over a fortnight now, which is wonderful (I’m still struggling to believe I’m a “proper” author now). And suddenly I have another release to write about. I have a Valentine’s story, Aunt Adeline’s Bequest, coming out next week as part of Dreamspinner’s Valentine’s Rainbow Collection. There are fourteen stories in the collection in total, all from established DSP authors. They’re being released one a day from today until the 14th, or you can buy the whole set to read now. It looks like a lovely mixture of genres and styles. Mine is my first historical, a little story set in 1920 between the young owner of a chocolate shop in Chester and the WW1 veteran who wanders in looking for help to solve a family mystery.

Click image to preorder!

Click image to buy!

Here, in order, are all fourteen. Click on a cover to find out more about each title!With that release comes only the second time in two and a half years when I won’t have a story either under consideration or somewhere in the production process. In some ways it’s a breather in what’s turned out to be a stinker of a month in my day job (I’m seriously beginning to suspect that our management team were just having a competition to see who could come up with the most deadlines to squish into a single fortnight). Mostly though, it makes me want to write something very fast. As I’m at the usual mid-book nadir with Resistance, however, I’ve banned myself from tempting little plot bunnies until the first draft of that is done. I’m seriously beginning to wonder if I’ve bitten off more than I can chew with this one. I don’t like killing characters off. Why the fuck am I writing a plague book?

One bright moment in amongst the deadline frenzy and the flu was the arrival of my author copies of Reawakening. Here’s Mini-Tarn showing off the loot:

And finally, since I haven’t done one in a while, have a nearly-Sunday Snippet. This is from the scene of Resistance I’m currently battling with. Iskandir has snuck out of the palace to help tend to plague victims. Halsarr, Tarn’s snippier younger brother, really doesn’t appreciate that…

By the time he returned to the palace, long after dark, Iskandir felt like a hollow man. He had eased the pain of so many of the dying that it had scoured out a bleak and empty place in his heart, a cavern that echoed with the names of the sick, the grieving, and the dead.

He slipped through the side door with a slow sigh of relief, bolting it behind him. The little room was dark, even with the snow gleaming outside, and it took a moment for him to realize that he was not alone.

Then Hal growled, “Strip.”

“What?” Iskandir said, startled out of his despair.

“Take your clothes off.”

“Why? It’s snowing, Hal. Be reasonable.”

“In the last hour I have welded every other door in this palace to its frame and sealed every air vent from the clinic. The only reason this one remains is because I discovered you had left the palace to go and face death!”

It had been some time since Iskandir had last experienced this, but he recognised a furious and overprotective dragon when he heard one. Gentling his voice, he said, “You know I can’t catch it, lover. I have resistance. It won’t even touch me.”

“And what if you’ve carried it home? What if it’s crawling in your clothes or across your skin?”

“What?”

“It’s the fleas,” Hal snapped, his voice taut. “It’s carried by fleas. So take your damn clothes off.”

“That’s why the rats died,” Iskandir said slowly, thinking through the implications. “And why the dogs got sick last time. How can we possibly stop something that small from—”

Hal obviously ran out of patience, for suddenly Iskandir’s clothes caught fire. The flames roared across him, making the air crackle and taste acrid, but they did not burn him. Instead they sent his clothes crumbling into flaking ash and then raced across his skin in a wash of glorious, startling heat. Every hair on his skin stood on end and then crisped under the racing flames. By their light, he could see Hal’s face, tight, furious and frightened.

Iskandir took a shallow breath, suddenly aware that all that kept him from being burnt himself was the intensity of Hal’s concentration. After a day surrounded by death, it made his pulse dance and his breath come hard and fast. He flushed, the blood rising under his skin and making his head swim as the air crackled around him with the faintly acrid scent of burning hair. Around his feet, the ruins of his clothes crumbled into gray dust, warm around his bared soles.

“I’ve had it before,” he managed, his voice breathless and husky. “You can’t catch the same disease twice.”

“When it comes to you,” Hal snapped, “anything is possible.”

And with that, I shall finish off with a final invitation. I did an author chat over on the DSP Goodreads page a couple of weeks ago, but it was quite quiet. If anyone still has any questions about Reawakening, ask away!

January 15, 2014

Reawakening: Meet the Characters (Raif)

With two days to go, here’s the last of the introductions to the cast of Reawakening. I saved my own favourite until last, naturally, so I’m delighted to introduce Raif, an exiled son of Tiallat, the nation the Shadow has turned to its own purposes. I’m still hoping that I’ll have a chance to write Raif’s book one day, but there’s a lot which needs to happen before then. For now, come with me to the Alagard Desert, where he lies dreaming in the tent of his father, far from the hill roads of Tiallat…

Raif

Raif dreamed he was above the Rulat Pass, crouching in the narrow shade of a fractured rock. The sun poured over him with the full force of summer. The light in the high mountains, where the air was thin, made every day feel like a dream, but this time Raif knew it was not real. All the same, he breathed in the hot dry air and lifted his head to gaze down the pass, over folded mountains the color of dry rose leaves. The sky was as blue as azure, with only the faintest haze over the horizon.

His shadow stretched out behind him, across the rocks, and he moved instinctively to conceal it within other shadows so that the landscape itself, Tiallat his own country, would hide him when the army of the Fist came marching through. For he had been here before, three years ago, waiting to ambush the Savattin guard as they marched behind the banner of the scarlet fist. He had not been alone then, and so he looked up the slope to where his friend had waited beside him.

There was someone there, although he knew at once that this was not Iskandir (and how could it be, when he had left Iskandir behind in Tiallat, holding the resistance together with nothing more then the strength of his hands). Like his friend, though, this stranger had the sturdy build of a Rulatai tribesman, from the remote central plateau. When he turned to look at Raif, he could see that the man had eyes that were two shades of green, in the quirk the Rulatai called God’s tears and took as a sign of greatness. Raif could see nothing more of the stranger’s face, hidden as it was beneath the scarf that covered his head and neck and protected his mouth from the blowing dust. One look at the stranger’s eyes, however, told him all he needed to know. His left eye was as bright as malachite, whereas the right was as dark as shadowed moss, but both gleamed with their own light, as no mortal man’s could.

“Raif,” he said, and his voice was as low as the wind over the mountains. “Beware the Shadow.”

“Lord,” Raif said to the Dual God of Tiallat, dropping to one knee. “Please. Your country needs you.”

But below them in the pass, the sound of marching feet was growing louder, as steady as drums, and the Dual God was walking away from Raif, vanishing again, as he had vanished when the Savattin came riding across the border to turn god’s own country into a land of grief and shadows. As Raif reached out for him, crying, “Lord!” he faded into the heat-hazed air, becoming as distant as the blue line of the faraway mountains.

And Raif woke, sitting upright, with his hands stretched out and his heart pounding in his chest.

It took him a moment to remember where he was. The light was golden and rippling with the soft sigh of the wind against the tent walls, and in the next bed his brother was snuffling into his pillow, his shoulders lax in sleep.

He was in the Alagard again, safe in the desert, beyond the reach of the Fist, beyond the sight of the Dual God. The air was dry here, and he had to breathe slowly until his body remembered that he was not in the highlands of Tiallat. Then he rose from his bed, feeling the sand sink beneath his bare feet and dressed quickly before padding outside.

His father sat by the fire, a pen idle in his hand as he contemplated the sunrise over the desert. It was a bright sky this morning, pink and gold and silver, and Raif paused to appreciate it. Tiallat had its own loveliness, dearer to him than this, but it had been too long since he saw a desert sunrise.

“Bad dream?” his father asked.

“I almost saw god,” Raif said, grimacing as he approached the fire.

“Religion,” Namik Shan said. “It’s bad for you, in excess.”

“As are all things,” Raif agreed, because he was still sleep-mazed to argue. “Is the tea brewed?”

“Should be.”

Even after thirteen years in exile, his father still brewed tea the Tiallatai way, in the enamelled samovar he had brought with him when he fled before the wrath of the Savattin. Raif could vaguely remember that desperate flight over the mountains, with the snow crunching below his feet as he clung to his father’s side and whispered lullabies to baby Zeki to keep him quiet. He could remember how the desert had welcomed them with light and heat as they came down out of the mountains. He had thought it the most beautiful place in the world then.

But Tiallat’s need had called him home in the end. Fanaticism might have chased away the poets and dreamers, but a poet’s son could wield a bloodier weapon than a pen.

Of course, he could also end up with such a price upon his head that he had been sent back into exile to wait until the Savattin stopped scouring the villages for him. He hoped Iskandir would send for him soon. A man should not have to linger too long at his father’s hearth, not once he had gone into the world to face his own test.

The tea was sweet with cinnamon and cardamom and tasted like home.

“Do they still serve it with ground almonds, up on the plateau?” his father asked, his eyes sad with memory.

“And rose petals, for a guest,” Raif said and lifted the shallow cup so the morning sun struck the golden liquid. “Bright Lord smile upon us.”

“Oh, shame on you, Raif,” a light, amused voice commented behind him. “Evoking your god in my desert. How rude.”

Raif choked on his tea and turned around to see Alagard, the spirit of the desert, saunter towards him. Alagard was as bright and pretty as his desert, and he was smirking widely. As Raif spluttered, Alagard clapped a hand to his heart and pouted at him, his silver eyes bright with mischief. “Oh, Raif. I thought you loved me best.”

“Yet again, Great Desert, you are mistaken in your assumptions,” Raif said, trying to stop his own smile from twitching out. “It is your advanced age, I am sure. You have my sympathy. Ow!”

Alagard tugged on Raif’s earlobe again. “Oh, what was that? Did you say, “Oh, Great Desert, let me prostrate myself before you and lick the sand from between your divine and lovely toes?” I’m sure that was what you meant to say.”

Raif chuckled and looked down to study Alagard’s feet. “I will admit that they are the most divine toes I have ever seen, although, alas, I have not had to opportunity to make a thorough study of the feet of gods. Does that satisfy you?”

“Your son is pert, Namik,” Alagard complained, but released Raif’s ear and dropped a kiss on his cheek anyway. “Welcome home, Raif. Where’s your brother?”

“Sleeping.”

“Ah, a stayabed. Shame on him, when the morning is so lovely.”

“He is fifteen,” Raif pointed out.

“Boys,” his father said with a shrug.

“Oh, you’re all boys to me,” Alagard said, throwing himself down to sit by the fire. He looked no older than Raif, lounging there, but he had looked just as young when Raif was six, and the oldest of the Selar riders remembered him from their own boyhood, his face unchanged by the years.

“Why are you here?” Raif asked. It was not unusual for Alagard to wander into a Selar camp. He went where the wind carried him. He rarely came at dawn, though, and there was a tension in his shoulders and a ferocity in his laughter which worried Raif.

“Did you not hear the drums?” his father asked. “The Selar called him.”

Raif remembered the thunder of marching feet in his dreams. “A prayer dance? At this hour?”

Alagard gestured towards Namik, his fingers stretched out tightly. “Tell him.”

“The outriders came in just before dawn,” Namik said. “They’ve been up to the pass. The army of the Fist have marched their banners down to the foot of the pass, and there’s more than a border garrison behind them.”

So, even the desert was not safe. Raif looked up, towards the foothills of the Illiats where they rose from the desert a few miles away. They looked quiet, in the morning light, but he had heard his father talk of the morning before the revolution. That had been a bright spring too, before the clouds began to gather over Tiallat.

“They’re coming,” he said softly.

“I think our time of quiet is over,” Alagard agreed, unusually sober. “Too many great powers are taking an interest in us, both from the north and the east. I’ve advised the tribe mothers to swing back towards the Riada. Once you’re clear I’ll turn the wind towards the pass. They won’t find it easy to cross the desert. That much I can promise.”

For a moment, Raif imagined watching Alagard fade away from his people, as the Dual God had vanished from the people of Tiallat. It was a dark thought and he put it aside carefully before turning back to Alagard to say, “We will do whatever you need. Your enemy is our enemy.”

“Thank you,” Alagard said, looking towards the hills. He looked distant and worried, as he rarely did, and Raif felt a shiver of anticipation run through him, as it did just before the horns signalled them into an ambush. “But I want you to be safe. That is all.”

Strange to think that in some ways Raif knew more of the world than this ancient spirit. There was nowhere safe under the sun, not in this age, and Raif found himself hoping bleakly that Alagard never came to learn that hard truth.

January 13, 2014

Reawakening: Meet the characters...

A quick head's up for the goodreads folks. I have been continuing to post missing scenes about the supporting cast of Reawakening over at my blog. Unfortunately, Goodreads seems to have some troubles with rss feeds at the moment, so they haven't been updating here!

If you enjoyed the first one, you can also meet guard captain Ia, caravan guards Dit, Jancis and Ellia, and young priestess Esen by following these links. Hopefully Goodreads will have it's act together again within a day or two, as I've got one more installment to come!

January 12, 2014

Reawakening: Meet the characters (Esen and Alagard)

Just a little one today, to take you to the oasis town of Istel in the Alagard Desert, where Alagard’s priest is spending a quiet evening at home with his daughter (and his god, of course, who always makes things noisier…)

Esen

Her father was singing as he cooked dinner, his voice cheerful and tuneless. If Esen listened closely, she could pick out words over the clatter of pans and hiss of sizzling oil, even from where she stood in the great hall of the temple below.

He was serenading the lentils again.

Rolling her eyes, Esen quickened her pace nonetheless, sweeping her way across the temple floor in a whirl of dust and sand which Alagard himself wouldn’t have scorned. She was hungry, and chores must be done before food.

“You’ll just make a bigger mess if you rush.”

She dropped the broom, whirling round to see her god leaning in the doorway and grinning at her. With a shriek, she hurled herself at him. “You’re back!”

Alagard caught her and whirled her round, as fast as if she was dancing. “How’s my girl?”

“Fourteen,” Esen reminded him, with a sigh. No one seemed to realize that she was almost an adult.

“So old,” Alagard said dolefully and tweaked her nose. He might look only a few years older than her, but he had bounced her on his knee as a baby and never let her forget it. “Too old to accept my help finishing your chores?”

“Really?”

He drew her close, grinning. “Sweeping up the dust, right? Ready?” He spread out his hands and the sand that a day’s worth of worshippers had brought in began to shift and stir. A wind rippled across the temple, making the hangings on the wall quiver and the brass windspinners hanging from the ceiling began to turn. Alagard snapped his fingers and suddenly the wind rose into two whirls, which went spinning across the great hall, picking up the dirt and bouncing off each other gleefully. They looked like a pair of drunks or children giddy from spinning around too much, and Esen burst into laughter.

“Open the back door!” Alagard shouted, laughing with her. “Dust belongs outside!”

She ran for the door, laughing so hard she staggered. Alagard brought his hands close together, grinning, and the whirlwinds suddenly converged to chase her. She managed to fling the back door open and hung to it as two streams of whirling dust shot past her and suddenly folded up into neat little piles of sand and dust.

“There!” Alagard said by her shoulder. “I don’t know why anyone wastes time sweeping.”

“Alagard!” her father’s voice boomed down from the upper gallery, where the door to their living quarters was propped open. “Are you helping my daughter cheat on her chores?”

“Oops,” Alagard said. “Caught.” He threw his arm around Esen’s shoulder and pulled her back inside. “It was all her idea.”

Her father chuckled. “I’ve known you too long, Great Desert. Get up here. Food’s ready. Esen, close that door on your way up.”

She hesitated for a moment, caught by the brightness of the moon. It was full and the light spilled down across the quiet waters of the oasis and the gleaming white roofs of the town. The stars were bright over the desert tonight, with nothing more than a soft wind making the bells sing out from the streets below. Well, of course Istel looked lovely. Alagard was here to visit, and so the desert showed her best face.

“Esen, your dinner is getting cold!”

“No, it’s not,” Alagard called over him. “I’m eating it.”

Laughing, Esen closed the door and ran upstairs to join them.

It’s not going to stay so calm for long. There’s a dragon on his way…

![ValentineRainbow[A]LG](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1391438536i/8388134.jpg)