C.P.D. Harris's Blog, page 77

April 23, 2013

Teaser Tuesday

“Red Scorpion, I presume?”

Sadira turned to find herself face to face with a tall, white-haired man with bright eyes and a broad smile that showed perfect, glittering teeth. Despite his hair and patronly features he seemed to be one of the Gifted. A stunning woman dressed in butterfly wings and a matching mask and little else hung off his arm. He looked familiar.

“I am. My friends call me Sadira,” she said, smiling. She noticed several passersby turning to watch the exchange. “Have we met before?”

“I am Gaius Gerald White,” he said. His voice got louder as he announced his name. “My reputation precedes me, no doubt.”

“It does,” said Sadira, stiffening in anger. Gaius Gerald White was a commentator and publisher who owned the famed Arena Post; his paper frequently and gleefully reported baseless rumours of Sadira having affairs with other Gladiators; debasing herself at orgies in Chosen Giselle’s palace. It was not the nature of the accusations that angered Sadira, she wasn’t embarrassed about sex, it was that they were lies. She was proud of her love for Gavin, and proud of her self-control in staying true to him. “Are you here to apologize?”

“Oh, meow,” said White, laughing as Sadira’s eyes raked him. The woman on his arm however, sensed the anger of the Gladiatrix and paled. “If you wanted to stay out of the public eye you should have become a vassal.”

“Really?” said Sadira. “If vassals were exempt from your drivel, then why did you publish that crap about Lina? You should be ashamed of yourself.”

This is a little scene I wrote up today, filling in a problem area that originally looked something like this

Sadira confronts GGW. Highlight rumours and her frustrations with them. (Actually highlighted in yellow, but you get the idea.)

I write these when I’m stymied or want to move on to other parts of the story, then come back and fill them in. I find it is a good technique when I need to “discover” additional parts of a sub-plot before filling everything in.

The rest of the scene is fairly obscene with GGW and Sadira arguing about some very graphic accusations, until the argument gets broken up. It takes place a the Veteran’s Masquerade, a huge party where high ranking Gladiators seek patrons for the Grand Championships. It is like a high society political event crossed with a major league sports trade deadline… The backdrop is a converted Dragon’s Lair

April 21, 2013

Battle Tactics: Classical Warfare and How Magic Might Change it.

One of the great weaknesses of Fantasy novels in my mind is in their battle descriptions. While many authors research some aspects of warfare diligently and present it intelligently, I find that few take their world’s Fantastic elements into account in the fortifications, warfare, and battle tactics of their world. Consider this: If a world was conquered by men and women who rode Dragons as weapons of war, wouldn’t the fortifications their descendants build reflect this? I frequently read novels where Dragons have been used as weapons of war, but almost all of them have castles and strongholds built in the medieval fashion. What good is a high wall if your opponent’s most fearsome weapon can simply fly over it?

A Castle built to defend against Dragons needs some form of hardened roof, dome, or defence platforms to repel aerial attack. Play a game like Dwarf Fortress, where you can be attacked by Dragons and other flying monstrosities and the weaknesses of the standard medieval model of fortification become immediately apparent. You might also live long enough to realize why having easily accessible tombs, graveyards, and garbage pits might be a bad idea when enemy necromancers come around.

For this article I am going to concentrate on the classical age: mainly Greek and Roman tactics with a little bit of the Celts and Carthage on the side. I’ll describe the main tactics in very basic detail and then give examples of how magic might chanage these.

Mob Melee [Default]: In the Classical age the default style of battlefield warfare was simply to group up and rush forward. Combatants attempted to crush the enemy through superior strength and the weight of the charge mass and if they failed to do so the combat immediately dissolved into a mass melee. In the melee skilled individuals could wreak havoc. Many peoples, including the Celts appeared to use this model of warfare. It also appears that this is the style of fighting described in the Iliad. I am oversimplifying.

In tribal warfare and early militias you fought with what you could afford. It was hard to create a serious formation with mismatched arms and armour.

The Phalanx [Formation Warfare 1]: The Phalanx is the dominant formation of the Hellenic age. With warrior cultures like Sparta and the Macedonian system, we see permanent units formed and true formation tactics arrive. The Phalanx at its simplest, is a mass of men formed into several lines armed with spears or pikes and shields. The men behind the front of the line can attack over the shoulders of those in front. Mob Melee is utterly ineffective against a Phalanx; the charging warriors cannot get close to the mass of the Phalanx without being impaled on spears. This method of warfare was so dominant, that the Greeks, who seem to have mastered it first, were at a huge advantage over other forces. Greek mercenaries were highly sought after. Two Phalanxes attacking each other became locked in a contest that was won by the side that either got help first or applied the most strength or discipline (here is an interesting post about two Hoplite Phalanx’s clashing)

It required a fair bit of training to form and hold a Phalanx well. The Spartans were a martial culture, raised to warfare while the Macedonians were nearly a professional army, constantly at war under Phillip and Alexander.

If an enemy could break past the pikes the long weapons would become a liability and the formation broke.

Most Phalanxes were effective against direct cavalry charges.

A Phalanx that came under missile attack could cross its spears to gain additional protection.

With formation training, complex manoeuvres became possible. An example of this was Macedonian soldiers parting on command to avoid flaming bundles and boulders being rolled down hills into their midst and instantly reforming.

A colourful depiction of a phalanx.

The Roman Legion [Formation Warfare 2]: The Roman Battle line gradually dropped the spears in favour of Javelins that were thrown at enemies to break up mob formations and Phalanxes alike. The Larger shields provided extra protection while the swords were better once an enemy closed and easier to use when tired. The Romans practiced cycling soldiers in and out of the lines to give tired soldiers a chance to rest. They also added special formations like the famous tortoise to their list.

The Pilum were made to pierce shield and bend, getting stuck in the shield and thus weighing it down. This was apparently effective enough against a Phalanx that the Romans could then close in and break the lines while maintaining their own.

Some forms of Mob Melee presented unique problems for the Roman formations that would have failed against a Phalanx. The heavy swords of the lightly armoured Dacians (the Falx) were apparently an issued since they could cleave through shield and helmets. This was solved by reinforcing both.

Romans used a very wide variety of specialty units, the best soldiers of client states and conquered peoples.

The Romans actually mixed their legion formations quite a bit over the years. Results varied.

Doesn’t quite capture the feel of the Legion formation, but I could not find a better pic.

Mounted Warriors in Classical Battles [Auxilliaries 1]: Cavalry in the Classical age was often used to attack the Flanks of Phalanxes that were engaged. Alexander was famous for using his cavalry to sweep through enemy infantry once they were engaged with his Phalanxes. Mounted warriors would often dismount to fight if they had to engage head on.

Stirrups, and thus long lances did not really appear until later.

Archers, Slingers, and Skirmishers [Auxiliaries 2]: Skirmishers provided a screen that distracted enemy cavalry and slowed phalanxes. These lightly armoured and highly mobile infantry were never really supposed to engaged the enemy directly. Archers were common in this period as well, but did not dominate. Slingers were of great uses against slow formations, they were shorter range than archers but apparently could hit very hard. All of these saw use alongside and against the main formations.

Few archers in this time period had easy access to bows powerful enough to penetrate heavy armour/shields. The Scytheans were noted.

While legion javelins were primarily used to break enemy formations, some skirmishers were known to use them as a primary weapon. The early Thracians were noted for this, in a few sources. The Iliad has a quite a bit of spear and javelin throwing, even a dude wielding two at once (take that RPG rules!)

Sling head-shots were apparently rather lethal.

Chariots [Default Auxiliaries : Chariots show up as a form of noble warfare in the Celts and Early Greeks. They provided a mobile platform for missile attacks and a way for a heavily-armoured individual to get around the battlefield, dismount and fighting. The famous wheel scythes allowed some charioteers to really dominate mob melee and even do serious flanking damage to a formation.

Elephants [A Real Life Fantasy Unit?]: Elephants were encountered as weapons of war in this period. The sheer size and mass of a war-trained elephant allowed it to break all but the most disciplined of formations. The cost of food, training, and armour made them tough to field and maintain but they presented real problems to the Greeks and Early Romans.

Elephants and the tactics used against give a good example of how fantasy elements deform common tactics. The armies that ran up against them had to suddenly adapt to these unusual beasts.

Fantasy elements can change any of these.

Mages: Spell-casters are fairly common in fantasy tales these days. Wizards would likely have a tremendous impact on classical warfare.

Formations lasted well into the age of the cannon, but they were certainly changed by the advent of artillery. If you fantasy novel has mages involved in the conflict it changes the nature of the fight. Mages tossing exploding fireballs might spell the end of the Phalanx. Of course it could also mean that your legions use treated shields and a tortoise formation that helps reduces fire damage. Perhaps mages are attached to formations and strive to increased their soldiers strength, giving them an edge over enemy combatants (Tigana has something like this). Depending on the effective range of the magic being used this can really change the way fighting occurs.

Spells could be used to change the terrain, impeding formations and creating confusion.

Mages might just cancel each other out, waging a separate battle for dominance with spell and counter-spell until one side gains the upper hand and helps their troops.

Mages can also be used to counter fantastic creatures.

Fantastical Beasts/Races: If an Elephant is a problem, then a dragon is a real issue. Many fantasy novels feature huge and deadly creatures. Some of these are domesticated. If they end up being used in warfare, they change the nature of the field.

Unless your shields can withstand fire, then any creature that breathes fire will break formations and dominate the field. Dragons would likely be the center-pieces of whole armies in classical warfare unless some other way was found to stop them.

Flying units provide new angles of attack. Harpies can flank from the sky!

Giants, ogres, and trolls make for excellent formation breakers. They might get driven off by Phalanxes though. Well armed Giants fighting in formation would dominate the field. Of course, feeding that formation of giants might be a problem.

Elven archery and monsters with ranges attacks might also act as a substitute for magery here.

And what happens if your men are armed with enchanted weapons or elemental siege engines? Each element must be considered carefully. If you think it through, your readers will enjoy your battle-scenes more instead of questioning why your elven snipers don’t take down commanders or how on earth a motte and bailey seems useful in an age of Dragon Lords.

April 18, 2013

Mystical Hyperdrives: Technology, Magic, and Causality

Clarke’s Three Laws:

1) When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong

2) The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible

3) Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Guild Wars Techno-magic. The engineer class, a device based magic user.

Arthur C Clarke was a very wise man, a product of an age when the interplay between Science Fiction and predicting the future was such that many fervently believe that the imaginations of exceptional writers drove technology forward. The list of things that he predicted is rather impressive. This blog post is not about Arthur C Clarke directly, or even about his laws. I am using it defensively because in any discussion of magic and technology Clarke’s third law will be cited almost immediately, in or out of context.

I am interested in writing in what distinguishes magic from technology, and also discussing what constitutes a proper magical technology. I feel that modern Fantasy touches on both, as well as the combination of the two. The days when guns and starships stayed away from swords and spells are long gone, with modern audiences enjoying good crossovers as much as traditional Fantasy.

The main difference between Magic and Technology is that the later must have a much larger and more robust causal link. Take the Star Wars Hyperdrive. The Star War Hyperdrive seems magical in that is impossible in our current scientific paradigm to move 120,000 light years in a few hours. We can’t really even theorize how that would be possible, plausibly these days. You could invoke Clarke’s third law here if you wish. I would sagely nod compliment you on your sagacity and ask: well how do you know its not magic then?

And this is the crux of the matter. Star Wars has magic: The Force. The Force obeys its own set of laws that exist outside of any purely scientific paradigm we can imagine. Indeed this is noted in passing in A New Hope (The whole I find your lack of faith disturbing scene). When Lucas introduced Midi-Chlorians in an attempt to add a sense of pseudo-causality to The Force in The Phantom Menace, it offended many fans. It stripped away the sense of ancient mysticism surrounding The Force and replaced it with little organisms that reside in your blood. Neither explanation is causal, since they can’t explain why or how this lets you pick up a Tie Fighter by willing it so. The new explanation was less satisfying to people who invested in the first, since it broke rules that were already established.

Back to Hyperdrives. Because The Forces exists in Star Wars, it is reasonably important to distinguish technology from magic. This is where Hyperdrives fall flat. They don’t follow any reasonable extrapolation of scientific theory and they don’t seem to be part of The Force. They are ultimately an unsatisfying explanation of how people get from point A to Point B in a Galactic empire. Most people won’t care, but those who are inclined to question that sort of thing will be put off.

Here are a few ways that I think Technology should be distinguishable from magic.

1) Technology builds on ideas that we already know, Magic is mostly explained to the reader: If I put a gun in a book, I rarely have to explain how it works. A writer can assume his audience will know a certain amount about modern technology, often enough to extrapolate on that technology. With a minimal understanding of guns more advanced forms like Gauss Rifles, Gyrojets, and Smartguns become sound story devices with very little explanation. If I write about magic I have to explain enough of it to situate the reader. They need to know what magic can and cannot do, and how it appears in the story. If Magic is frequently wielded by the protagonist then the explanations must be more and more detailed. Because magic is not based on normal cause and effect, it usually requires a more detailed explanation from the author to maintain consistency. A few authors, such a Guy Gavriel Kay make effective use of magic as a pure mystery but magical effects must be very rare and the quality of writing must be very high for this to work.

2) Technology should obeys the laws of science, Magic should be internally consistent: A handgun that shot black holes that swallowed up enemies would be frowned on as a technological device. It simply violates the laws of physics in so many ways that not even the craziest of theories based on current science would be able to explain it well enough to satisfy an average reader. A sphere of annihilation that sucks enemies into another dimension, powered by magical incantations and force of will would work perfectly well in many magic systems, however. Technology works best when it is based on recognizable concepts and obeys what we know about science. It just seems to trivialize human progress if it doesn’t. Magic on the other hand usually resides outside the realm of science. It is a metaphor for the unknowable, the mysterious, and often the creative process itself. Magic systems must be internally consistent, often more rigidly that technology. If a magic system breaks a rule that the writer has set out for it, it loses a great deal of credibility in the reader’s eyes.

3) Technology can be reverse engineered: If aliens showed up on earth with technology that broke current laws of science, most of us would think it was magic. However there is a large group of people who would simply sit down and go “hmmm, I wonder how that works and what the implications are for science.” these people would figure out that technology, fit it in to the new scientific paradigm, and then it would gradually become available as new technology where needed. Even if unusual barriers existed in understanding that technology, such as a weapon that only works for a select genetic group, some people would wonder why and try to figure it out.

4) Technology can be used by anyone who understands how, Magic can be used by a select group: You don’t actually have to understand the science behind a gun or a computer to use it. In fact, we can train monkeys to use some fairly complex devices with interesting results. Technology can often be learned through trial and error, since it behaves consistently. The iPad might seem like a wondrous device to a person who has never encountered modern technology, but after a while he’d be playing angry birds along with everyone else, at least until the batteries run out. Magic on the other hand tends to be the realm of the select few. In most Fantasy novels only a small percentage of people can work magic. In novels were magic is more commonplace then only a few can work truly the impressive feats of magic. Part of this is to maintain the sense of mystery, but much of it has to do with the idea that the wielders of magic must be special in some way (and not always in a good way).

Here a re a few blends I’m too tired to get into right now.

Fantastical Technology: Fantastical Technology is technology that obeys Clarke’s Third Law. It often does not work very well in a Fantasy novel because it clashes with the magic system. Some settings make it work though.

Techno-magic: Techno-magic is magic that is hidden behind the trappings of technology or needs technological devices to work. I’ve generally only seen this in tabletop RPGs.

Magical Technology: A gun that has an ever-full magazine is obviously magical, after all infinite ammunition in a single clip breaks the laws of science in many ways. However if the rest of the gun behaves in a an absolutely correct manner for that piece of technology it creates and interesting hybrid item that is part magic, part technology.

As subsets of Fantasy moves into the industrial age and the modern age it is increasingly important to distinguish magic from technology, at least enough that the reader can get a sense of each. By paying attention to science and causality a clever writer can do this, and even learn to blend the two in interesting ways.

April 16, 2013

Tuesday Teaser

Tuesday teaser, a bit of architecture:

The outer walls of Dun Mordhawk keep rise out of the steep sides of the jagged rock, curving to present as little flat surface as possible to outward attack. The stones that make up these walls are closely fitted and polished slick, even after centuries they show little sign of wear and no moss grows upon them; a sure sign of magic. Intricate machicolations line the parapet, providing an easy way of attacking enemies trying to attack the base of the wall and some defence against flying foes. Strong towers, round and squat provided many angles from which defenders can safely fire against any assaulting force.

The main gate is guarded by a fortified bastion cunningly built to slow down an attacking army but provide little cover against attacks from the main walls should it be taken. A thick drawbridge runs between the bastion and the main gate, made of rune-carved iron-wood beams stout enough to withstand considerable damage. The ditch under the drawbridge is an extension of the rocky hillside; and when the bridge is closed it gives the impression that Dun Mordhawk is a rocky island amid floating amidst surrounding hills. A heavy portcullis and a long entrance-way covered with convenient murder-holes for defending archers, gunners, and spearmen await any enemy strong enough to overcome the bridge.

The newest addition to the fortress, a large short barreled elemental flame cannon, waits to greet any who penetrate the courtyard. It is the type of weapon that destroys formations, not fortifications.

This is a machicolation:

Its like a downward facing arrow slit. This is an extreme example.

Here’s part of an unusual fight scene. I have to mix it up a bit to keep the action interesting.

The rules for the match were simple. Gavin was meant to find his foes and defeat them. They would, in turn, be hunting him. The only difference between this and a regular match was the environment and the added uncertainty of not knowing what enemies he faced, how many there were, and how they were coming at him.

The trumpets sounded. Within a heartbeat the roof of the maze above him became translucent to anyone looking up from below, obscuring Gavin’s view of the audience. He could still hear muffled sounds and see vague shadows but no details beyond these. He snapped the traditional salute at the crowd nonetheless, confident that while he could not see them they could certainly see him.

As he stepped further into the maze, his footfalls cushioned by the deep moss. He noticed a mist start to form low to the ground. He doubted it would rise high enough to obscure the action but it would certainly make it hard to see footprints in the moss or a small, crouching creature. A nervous tingle caressed his spine at the thought.

April 14, 2013

Roman Gladiators and Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s Tale

For death, when it stands near us, gives even to inexperienced men the courage not to seek to avoid the inevitable. So the gladiator, no matter how faint-hearted he has been throughout the fight, offers his throat to his opponent and directs the wavering blade to the vital spot. (Seneca. Epistles, 30.8)

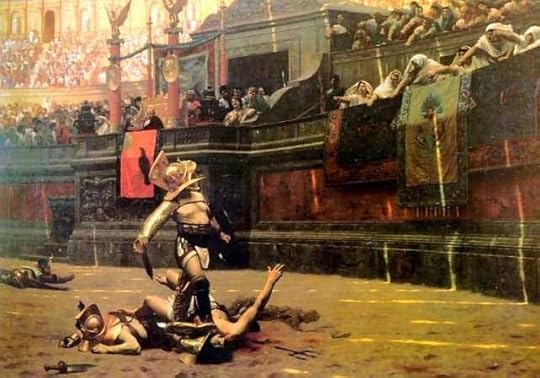

A dramatic depiction of the end of a deathmatch.

As regular readers have probably guessed by now, I am a big fan of the classical age. I love all things ancient Roman and Hellenic with a passion. As a child, before I had any understanding suffering, slavery, and death, I was really into Gladiators. The pictures of these athletic, imposing fighters with their iconic weapons and gear caught my interest long before I developed the critical faculties to question the morality of Bloodsports. Years later this interest would resurface when I was looking to create a faster, snappier alternative to GW’s Bloodbowl (a tabletop football game with fantasy elements) for my local games club, which led to a Bloodlust role-playing game (unpublished) and then finally to Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s Tale, my first novel.

Roman Gladiators are the most famous of the Bloodsport traditions. The Colosseum the archetypal arena, still stands in modern Rome evoking memories of bloodthirsty crowds and desperate battles. Livy dates the first use of Gladiators as 264 BC, a fight to the death in a forum, held as part of the funerary rites of an important personage. Livy emphasizes the theatrical tone, even then, but it is doubtful that it bore much resemblance to the decadent public spectacles of the late Republic and the Roman Empire. Likely it was closer to pit fighting at this stage. It is known that these commemorative rites with their ritual and sacrificial elements did continue and later gave rise to the greater Gladiatorial games. Famous examples of these early games include a Munus put on by Scipio Africanus during the Punic Wars to honour his family members, killed in the war against Carthage. Over twenty pairs of Gladiators fought by some accounts. It is possible that the cunning Scipio used this spectacle to raise morale. These early games were far more lethal, thought to always end in the death of one the fighters.

By the first century BCE, Rome was getting a taste of State sponsored fights, put on by the consuls for the express purpose of entertaining the public. These are the true beginning of the Gladiatorial games we see in movies and television. They were part sport and part circus, but all vicious. The political aspect of these games, which had consuls and later, Emperors, cynically using the bloody entertainments of the arena to manipulate public opinion are one of the things that I find most fascinating about the games.

Here are a few brief notes about the Roman games and how they compare to my use of Gladiators in Bloodlust.

1) Gladiators were divided into distinct types: Roman Gladiators, at least those who were trained in Ludi, each fought with distinct gear and a particular style. Some of these types began in imitation of the fighting styles of the early enemies of Rome, such as the Samnites, but in the end it seems to me that they were more about style and variety. Creation of distinct categories of fighters allows even modern fighting sports to mix it up and create a multitude of different events from wrestling to boxing to MMA. I expand upon this a little bit in Bloodlust with weight class, training types, and magic types but instead of following this rigid structure the Gladiators in Bloodlust choose new specializations becoming more an more individualized throughout their careers. At some point I will have to do up a separate post of all the Gladiator types from the Roman arenas with all of their interesting armour.

A Mosaic depicting two Gladiators fighting

2) Gladiator were a mix of free men, slaves, and prisoners of war: We all know that the Romans, like many ancient peoples, were cruel to those that they fought against. Rome just took it a step further institutionalizing their imperialistic humiliations as a sporting event. Conquered peoples who survived often ended up in the arena as fodder or if they had potential, as trained fighters. Interestingly, not all Roman Gladiators were slaves or prisoners of war. At the height of the games, there were professional, volunteer Gladiators who earned fame and fortune facing death in the arena. Some even estimate that these volunteers made up around half of the trained Gladiators. In Bloodlust the Gladiators are all magically adept people (called Gifted) who choose to fight in the games so that they can keep their magic and have a chance at becoming one of the Chosen. Magic is considered too dangerous to just let the Gifted use it freely and so they are kept under control until they earn the right to use it or give it up. That’s the surface theory, at least. The truth behind this is that it is a power play and an institution that has vastly outgrown its original purpose. This is similar to the Roman games which very quickly outgrew their origins and became very hard to control; even the reformist Christian Emperors had trouble stamping them out until Chariot Racing overtook them in popularity.

3) Women fought in the arena and Gladiatrix is not a word that I invented: No one is sure of how widespread female fighters were in the arena, but their is direct and circumstantial evidence that they did exist. There are references to women volunteering to train at the Gladiatorial schools. There are murals of bare-chested armoured Gladiatrices locked in combat and account of fights involving women. Grave markers of honoured female fighters have been found as well. In Bloodlust the women are right out there with the men, with Sadira being considered the best fighter of her “generation” of Gladiators.

4) Gladiators would not only fight each other but also animals of all sorts: It sounds like animal cruelty, but its really just cruelty in general. Roman Gladiators killed and were killed by animals in the arena. Beast fights were considered more sporting than fights against Noxii, untrained fighters, but generally far less interesting than a bout between two trained and well-promoted fighters. In Bloodlust I switch it up a little. While fights between Gladiators are still considered the most exciting form of the sport, the Gladiators are commonly pitted against monstrous foes from outside the Domains. These monster fights are a form of ritualized jingoism that allow the people of the Domains to see the horrors that exist outside their borders being dominated and destroyed by their favorite fighters. I leave it to the reader to decided if this is ugly, offensive imperialism or just good old action porn. After all, Beastmen and Wirn are evil, right?

A depiction of Gladiators fighting beasts.

5) Gladiators were taught in Schools (Ludi): As the Roman games worked up into full swing Schools were founded to train the most promising of candidates. Gladiators would train hard at these schools, honing their skills between each match. I don’t really change this much in Bloodlust, although my Gladiators can train harder since they heal faster and do not owe allegiance to their schools.

6) In the later Gladiatorial games, lethality became less important than celebrity. It seemed that a brave, well-known fighter stood a good chance of seeing mercy if defeated. Some Gladiators fought in as many as a hundred and fifty matches, which makes me think that the fights were often wildly unequal. This is similar to Bloodlust, where Deathmatches are fairly rare. However in the imperial period, the lethality of Gladiatrial contests often varied by Emperor, with guys like Caligula wanting the bloodiest matches possible. Again, I follow this idea Bloodlust, where politics can interfere with the Great Games and a few fans always want to return to the good ol’ days where every fight ended with death.

7) There were some crazy match types: Roman Gladiators would sometimes re-enact famous battles in crazy set pieces. There are even accounts of the Colosseum being flooded to enact a naval battle. I expand on this Bloodlust with many usual match types and a bewildering variety of special rules.

I could go on. Roman Gladiators still fascinate me, despite the ugly aspects of the arena. There is so much to cover here, if you can stomach it. The ancillary aspects of the Roman games like the Factions and the sportsmanship also appear in my work. The stylized, sexualized armour. The crazy gear. Interesting topic, if a little grim. Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s Tale is at least in part my attempt to face my own guilty fascination with this heady mix of celebrity, politics and brutal bloodsport.

April 12, 2013

Mjolnir, Excalibur, Stormbringer, and Sting: The Role of the Magic Weapon in Fantasy

Firstly: I had a nice interview with Dan Hitt over at Deepmagik, you can read my answers to his questions here. He has a nice collection of writing advice and interviews. Good stuff!

Now on to glory!

Magic weapons have been a part of fantasy since its earliest forms. This likely began with the association of tools as symbols with particular gods in ancient pantheons. Thor has his hammer, Zeus has his lightning bolts, Ares has his spear and so on. In fact all of these Gods have a small constellation of weapons and tools associated with them. What began with Gods quickly transferred over to epic heroes, and then to fantasy literature.

Runes. Check. Unusual look. Check. Too big for normal person. Check.

In some Fantasy works a weapon acts as a more complex metaphor. The sword of power acts as a tool to identify the chosen hero in many pastoral works, while the same sword of power acts as a metaphor for the implication of violence that underlies all power in other, darker works.

In many societies and sub-cultures weapons achieve a status beyond that of a simple tool. A weapon is a powerful scared object, used to destroy one’s enemies. A good weapon is revered because it is a tool of life and death. It is no wonder that to this day people often treat their weapons (and other familiar tools) as living things, naming them, and ascribing special qualities to them. Weapon fetishization is particularly prevalent in warrior cults and warrior nobility, where superiors weapons are a symbol of power. Blessings, runes, and personalization are all common as each warrior tries to outdo the others in quality and implied power. A superior smith whose secret knowledge is almost magical in pre-industrial societies becomes almost saintly. I explore this kind of fetishization a bit In Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s Tale, where each Gladiator chooses their weapons and continually improves them throughout, often naming them after important deeds. The weapon also serves as an indication of character. Sadira uses curved blades used of obsidian coloured metal, swift and elegant, while her harsh tempered friend Karmal prefer a massive war-cleaver, a fearsome, but unwieldy weapon.

This fetishization can lead to weapons that are works of art. The most obvious example would be the Katana, wondrous swords that can only be made properly by master craftsman, almost a lost art. Others abound, the Great Rapiers made in Italy during the renaissance, Swords of Damascus steel, The incredible horn composite bows of the Mongols, and so on. Some of these weapons transcend their use in war and become more ceremonial and decadent, almost emulating the nobility who used them.

Often magical weapons are the only thing that can harm certain creatures in Fantasy, becoming the object of a quest. This can be highly metaphorical like a sword that shows the villain his true self, or more gamist like a the only sword that can cut the head from the Jabberwocky.

Here are a few famous magic weapons from myth and Fantasy.

Mjolnir: Thor’s mighty hammer. So heavy that only he can wield it properly (this varies), Thor’s hammer is his primary symbol as a god. It is thought that the Hammer has some significance to thunder, which relates to his role as a storm god. It is also a less refined weapon than the spear or sword, which are symbols of more remote gods in the Nordic Pantheons. The Hammer is part weapon, but also part tool, which is appropriate since Thor was a popular, everyman’s god. Mjolnir is fantastically deadly, especially against giants, and was crafted by those most secret of smiths: the Dwarves. Mjolnir is a good example of a weapon that is a divine symbol. The only person who wields it with any success, or can even lift it in some cases, other than Thor is his son. Mjolnir is associated with Thor and always works for him.

Gae Bulg: Cu Chullain’s spear. Gae Bolg is a gift to the great Celtci warrior from his teacher, the mighty Scathach. After she teaches Cu Chullain, she gifts him with this crazy weapon. It is thrown with the foot and is covered with some many deadly barbs that it has to be cut out of anyone who it his before it can be used again. Gae Bulg is a good example of a weapon that is an affirmation of a warrior’s skill. It is so complex that it requires special training to master and use. Only Scathach and Cu Chullain can use it properly, and when they do it gains special powers.

Excalibur: The quintessential sword of power. Excalibur is King Arthur’s sword, his symbol of office as King, given to him by the lady of the lake (or reforged by her when it is the sword in the stone). Excalibur is the most potent weapon in the land, able to cut through armour and break other weapons. In many ways it is to Arthur as Mjolnir is to Thor, a symbol of his office. However, since Arthur’s office is partly based on moral strength, it seems that his weapons weaken when he is in the wrong. This represents a significant departure from a God’s weapon. Excalibur comes with strings attached: the sword of power might pass to another, more worthy hero should the current wielder fail.

Stormbringer: Stormbringer is the Elric’s Sword. It is a powerful weapon able to eat the souls those it strikes, provide Elric with strength and energy, and can cut through just about anything. Stormbringer is in fact, a living creature with a will and desires of its own, which has no master. Stormbringer is a good example of a magical weapon for an age where war is no longer seen as righteous or adventurous, it a metaphor for the hidden, ugly nature of power and force. It may make you strong, but it is ultimately your worst enemy.

Sting: While the ring of power serves as Tolkien’s version of Stormbringer (yeah, I went there), Frodo’s sword sting presents a simpler form of magic weapon. While powerful it is still a tool, and more interesting because it has a story. Its power’s, other than quality, seem fairly trivial but its enemies fear it nonetheless. Like most of Tolkien, Sting is more complex than first Glance. The sword lights up at the approach of orcs, which warns the wielder but also makes it hard to hide, forcing confrontation. It is a good example of a more mortal magic weapon, far less mighty than any of the others, but with a nice history and some minor powers.

Magic weapons cycle in and out of fashion in Fantasy fiction. Powerful named weapons with unique appearances are especially popular as prestige items in computer games. I suspect with the rise of geek chic and the modern tendency towards gear fetishization in some circles we will see more of them appearing in Fantasy novels as well. The role of the magic weapon can simply be window dressing, but it can also act as a unique and interesting metaphor in the hands of a clever writer.

April 9, 2013

Teaser Tuesday: Raw to First Pass

I finished the first draft of Bloodlust: Will to Power this weekend. I am now engaged in polishing it while I await beta reader reactions.

Here is an example of raw, unpolished text.

Stonebreaker tossed the metal ball with surprising alacrity. Gavin raised his shield not a moment too soon. The ball rang against the nigh-impervious metal of the shield. The impact drove the Gladiator back, numbing his arm. The crowd cheered. The troll yanked on the chain, bringing the ball sailing back towards him and began whirling it above his head like a lasso. He moved purposely towards Gavin.

Gavin was unsure how to attack. His shield provided some defence, but the ball would wrap around the edge if he was not careful. It seemed that Stonebreaker wanted to herd him back into the wall where his options would be limited. Moving forward into the arc of the whirling ball and chain presented an obvious danger, but it gave him room to manoeuvre.

Stonebreaker let a length of chain slide through his grip, increasing his reach as the lethal ball swung once more towards Gavin. It was a skillful technique and Gavin was nearly caught off guard. He leapt up, jumping over swinging chain to avoid the deadly weapon.

He hit the ground, rolling towards his opponent, lancing out with his spear as he came to his feet. His weapon bit deep into an unarmoured spot above the troll’s hip-plates. The troll grunted but showed no signs of pain, drawing his chain in so that the ball whirled towards the Gladiator. Gavin ducked, weaving a spell. The heavy ball and chain cut the air above his head. The Gladiator channelled power into the spell, twisting and pulling on his spear as he backed away from the looming form of the massive troll.

The spear head came free, ribbons of red gore caught on its vicious barbs. Gavin’s powerful mental assault hit home as well, overcoming the trolls strong resistance filling his head with pain. This time Stonebreaker staggered. Gavin followed up by lunging forward, ramming his shield into the trolls face. The already unbalanced troll fell backwards, landing hard on the bloody sand.

Here is the same text after a brief first pass.

Stonebreaker tossed the metal ball underhand. The troll moved with impressive speed. Gavin swatted at the flying projectile. The metal mass clanged against his shield. The impact drove the Gladiator back a step, sending vibrations running down his arm. It was like block a shot from a small cannon. The crowd cheered.

Stonebreaker yanked on the chain, bringing the ball sailing back. He caught it in a leather palmed gauntlet, confident and efficient. Then he tossed the ball into the air and began whirling it above his head like a lasso. He started moving towards Gavin, purposeful and confident.

Gavin wasn’t sure how to attack. The troll had reach and range and was more resistant to his magic than other creatures. His shield provided some defence, but he guessed that Stonebreaker could get around that. A skilled chain weapon user could wrap the weapon’s head around the edge of a shield with a deft motion. Care would be need if he wanted to get close. It seemed that the troll’s plan was to herd him back into the wall where his mobility would be limited. Moving forward into the arc of the whirling ball and chain presented an obvious danger, but it would Gavin room to manoeuvre.

Gavin edged forward, keeping an eye on the ball. Stonebreaker, smirking, let a length of chain slide through his grip. This increased the reach of his weapon. The metal mass whirled towards the Gladiator. It was skillfully and subtly done. Gavin was nearly caught off guard. He leapt up, leaping over swinging chain to avoid the deadly weapon. He felt it pass under him, just missing his feet.

Gavin hit the ground, tumbling towards his opponent. He began to channel power, focusing for a spell. Coming to his feet, he lanced out with his spear. The broad blade bit deep, piercing unarmoured flesh above the troll’s hip-plates. Stonebreaker grunted, but did not falter. The troll drew his chain in so that the ball whirled towards the Gladiator. Gavin ducked. The heavy mass swept the air above his head. The Gladiator twisted and pulled on his weapon as he backed away from the looming form of his enemy. The spearhead came free, ribbons of red gore caught on its vicious barbs. Gavin felt a surge of Triumph as Stonebreaker’s smirk disappeared.

The Gladiator followed up, completing his spell. This powerful mental assault hit overcame the trolls strong resistance. This time Stonebreaker staggered. His chain fell to the ground, limp. Gavin lunged forward as he reeled, ramming his shield into the troll’s face. Already unbalanced, the troll toppled backwards, crashing down to the bloody sand.

The main changes I’ve made (so far) are to make the action sentences shorter, to clarify some of what is going on, and to vary my words a bit. After this I highlight problem sentences and move on. I like to think about it before giving it another pass.

Shorter action sentences give the fight a more dynamic feel, like listening to the blow by blow from a sportscaster. It also allows the writer to use a longer sentence to add a kind of slow motion highlight to a particular action, switching from short punchy sentences more detailed prose. I’m not sure if I’m skilled enough to work that kind of juxtaposition, but its fun to try

Word variance is important, critics will often parse your book and point out that you use certain words too often. With find/replace you can analyze this minor problem and fix it quite quickly. I tend to be more concerned about using the same words to often within the same scene or paragraph. However, repetition can be a powerful tool, which is something I try out with crowd chants in this book.

Feel free to compare the two and comment.

April 7, 2013

Classic Characters: Sauron

Sauron is an oft-maligned villain these days. Tolkien’s villain is frequently held up as an example of everything that is wrong with Fantasy Villainy. He seems too distant and shiftless in the Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit, a character who barely appears and merely seems to be the personification of Evil. I feel that his is mostly put forth by people who don’t want to read between the lines. Sauron is a subtle villain, whose influence and personality can be felt throughout Tolkien’s creation. He might not get much direct main-stage time, but his influence pervades the world and all of the action within it.

The Eye of Sauron and the Ring

Here are a few things that most Sauron bashers don’t consider

1) Sauron is not the actual Dark Lord: That honour belongs to Morgoth, one of the Valar, who rebelled against the designs of Eru. In Tolkien’s mythology, even the Elves don’t really understand Morgoth’s rebellion, likening it to disharmony within the original song of creation. The obvious comparison for Morgoth would be Lucifer, however it is worth noting that there were plenty of real rebels around in Tolkien’s time who had ugly, oppressive regimes. It is hard for me not to see some of these as influences on Tolkien. Morgoth was a totalitarian villain: he simply wanted to impose his will upon the world and would let nothing stand in his way. In Elven mythology he comes off as a caricature, but this is purposeful on Tolkien’s part. This is a man who would be familiar with works like Paradise lost as well as the simple medieval caricatures of the Devil.

Interestingly, Tolkien goes out of his way to note that Sauron is truly loyal to Morgoth after the renegade Valar gains his allegiance. Their relationship seems to indicate that he is a true believer in Morgoth’s vision rather than them being two self-serving villains working together out of self interest. Sauron is noted as admiring Morgoth’s strength and sense of expediency.

2) Sauron originally served Aule, the smith: Aule represents craft and technology in middle earth. Before joining Morgoth, Sauron was one of Aule’s most skilled followers. He helped shape middle-earth and many of the great wonders within it. Craftsmen often get attached to their work, and it is worth noting that when Sauron rebelled he ran straight to Middle-Earth to try to gain control of what he’d invested in. It is a little harder to see him as entirely in the wrong when you look at his actions from this perspective.

3) Sauron loved order: His love of order becomes his downfall since he sees Morgoth as a powerful figure who can impose his will upon the world. His creation of the rings of power can also be seen through this light, he merely wants control, and uses his craft to get it. The concept of order being a monstrous force is a very modern one, and all of Sauron’s acts are consistently about gaining control. He does not do evil just for evil’s sake as it might seem. Within the Lord of the Rings and it’s history, his actions are entirely consistent on this. He seeks power for the sake of control, not self-aggrandizement.

In his notes Tolkien is more direct stating that Sauron’s “capability of corrupting other minds, and even engaging their service, was a residue from the fact that his original desire for ‘order’ had really envisaged the good estate (especially physical well-being) of his ‘subjects” (Morgoth’s Ring). Sauron’s actions all flow from this, but are marred by impatience and single-mindedness.

4) Sauron comes bearing gifts: Far from always being the war-mongering brute, Sauron is quite capable of being charismatic and manipulative when it suits him. To forge the rings of power he posed as Annatar (The Giftbringer/Lord of Gifts?) and pretended to be an emissary from Aule. He seduced the elves of Eregion into creating the very rings that would enslave them, and nearly succeeded in getting them to wear them. In the end he failed, but he was still able to use the rings later to corrupt the kings of men who became the Nazgul. His actions as Annatar, which are part and parcel of Lord of the Rings lore, demonstrate the ability to plan for the long term and to act humbly and amiably to get his goals accomplished.

Sauron as he appeared in the first age. From LOTR Wikia.

5) He tries to help reconstruct Middle-Earth: When Sauron comes out hiding after Morgoth’s fall he originally attempts to help re-construct Middle-Earth. He sees it as a land abandoned by the Valar, and wants to re-organize it. He falls into the trap of thinking that his way is the best way, and then that is the only way, falling into old habits. Tolkien discussed this in letters and his notes, and it is quite consistent with Sauron’s actions.

6) Makes the best of bad situations: In the second Age, Sauron is confronted by the Númenóreans, the descendants of men and elves. They are so militarily powerful that he realizes that he cannot withstand them. Instead, he surrenders and allows himself to be taken captive, instead of bunkering down in Mordor. Over time he gains the trust of the Númenórean kings, and gradually convinces them of their own superiority. He tells them that Eru is an invention of the Valar, used to oppress them, and that the real creator is Melkor (aka Morgoth). He then gets them to worship Melkor, and sets himself up as high priest. Basically he realizes he can’t defeat these guys, and so he gets them to take him to their impregnable island where he perverts their religion. In the end, he sets the Númenóreans against the Valar, using one enemy to destroy the other. It doesn’t work out perfectly, but he does end the Númenóreans.

Sauron always has a plan. He resorts to force only when it is easy or required. He often shows great cunning and foresight in his plans and is willing to hide for long periods or act defeated and humble. He uses his lore and gifts to make himself useful to those who defeat him and then worms his way into their plans. Not exactly the actions of a mustache twirling megalomaniac. Putting his power into the ring actually worked out very well for Sauron since it allows him to return again and again.

7) Sauron is not the eye on the Tower: While the eye represents the will and presence of Sauron, he actually has a body somewhere in the tower beneath and is merely focusing his will through the eye. The eye itself represents his desire to control, always roaming, obsessively seeking out dissent.

Despite never appearing directly in a scene or as a perspective character Sauron is still a distinct villain with understandable goals. Plenty of people in human history have taken it upon themselves to impose order through force. Many of those who succeeded were praised and admired, despite their monstrous acts. Tolkien lived in the age of Totalitarianism and would be well aware of this. Sauron is comparable in many ways to Hitler or Stalin. He is also not as one-dimensional as he originally appears, demonstrating long-term planning skills, an aptitude with craft, and the ability to switch up his game plan when force fails him. Finally his willingness to follow when it suits his goals provides a key insight into his desires for order and his admiration for strength, both characteristics of Totalitarian societies, and fascism in general.

Personally I find Sauron to be an exceptional villain, and very interesting so long as one is willing to actually apply a bit of philology in analyzing him. He is more believable and interesting than his detractors are willing to give him credit for, but none of them seem to read between the lines. I like Sauron because I can identify with his desires, and can see how they can corrupt someone. He is the benchmark for all Fantasy Villains, and one to which very few measure up to.

April 4, 2013

In the Eye of the Reader

The Grimdark debate is still with us. Bumping into this article by Daniel Abraham re-ignited my thought process.

Yup.

Firstly, I think the generation that enjoyed The Lord of The Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia did not have any interested in Grimdark fantasy settings because they did not need the grit and grim brought to them. Living through a world war or two lets you fill in the blanks on what happened to Aslan on the Rock or Golum in the Tower on your own in very vivid detail.

Secondly, the article got me thinking about John Keegan’s Masks of Command, a brilliant book about the evolution of military leadership from Alexander to Hitler. Where Keegan rolls in on the Grimdark debate is in that masks of Command is actually a deep philosophical meditation on heroism. The central discussion is that in the age of Kings and Emperors, a leader had to give commands close to the front lines of battle. Alexander fought in the same mess as his men, Julius Caesar galloped around the battlefield in his distinctive cloak, Joan od Arc climbed siege ladders and so on. These warrior-kings and queens were often expected to lead by example, acting in a heroic fashion. When it worked, it could inspire the men to insane feats of bravery, when it failed it toppled empires. Alexander sums this up best. He led his men in every battle, had a flair for the dramatic, and when he went to far it ended his expansion and his empire. Even Napoleon and Wellington were present on the field at Waterloo, surveying the movements and giving commands of battle despite the massive amount of ordinance being thrown around and the staggering number of troops involved in such a concentrated area. As ballistics improved it became extremely difficult for a general to avoid snipers and concentrated fire. Some, like Rommel for a way to stay on the front lines regardless, but most began to rely on long distance communications. Civil war generals often had to rely on field glasses and dispatches; the heroics, if any, were left to their men. Hitler embodied a general who acted like an Alexander in the parade square but led from relative safety, a sham in his heroic image as well as many other things. He fostered a culture of hero worship in his men, rewarding those who excelled, but his centralization of command was distinctly anti-heroic and eventually ridiculous.

This is why people like Space Marines, you see, they lead from the front despite being in a post-modern battlefield. Perhaps Grimdark is a natural reaction to some of the excesses of the age where generals and leaders no longer have to share the dangers of their soldiers and people.

This leads me to the Heroes, by Joe Abercrombie, a book I have never read. I picked it up at a friends house once, read the back cover and swore: writing an entire book about a single battle is a cool idea — wish I’d been the first modern author to do it. That is my only judgement of the book; I won’t discuss something I haven’t read.

However I am quite willing to discuss other people’s reactions to the book. The Heroes is apparently a Grimdark depiction of this awesome battle between two decidedly ambivalent nations. From reading Best Served Cold, I don’t think Abercrombie gets fair treatment, despite being grim what I have read of his has humour and beauty. (I’m stuck on Best Served Cold because it makes me think about Causality and perspective). I’m going to go out on a limb and say that the Heroes is likely not as grim as Timothy Findley’s The Wars, and nowhere near as soul-crushing as Shake Hands with the Devil. With a stellar 4.4 rating on Amazon and a metric tonne of glowing reviews I bet it is damned entertaining. I should buy a copy for when my dinosaur brain works it’s way through his other book…

Where was I? Oh yes, Grimdark is a matter of perspective. It is all in the eye of the reader, you see. What I find grim, you might find entertaining or possibly even uplifting. I love the Warhammer 40k universe because despite the grit and the grime and the horrible, horrible things that happen the Space Wolves grin and bear it. Its over the top fun for me. Others read the Gaunt’s Ghosts novels by Dan Abnet and see a futuristic retelling of the meat-grinder body-count trench warfare of world war one. Each reader gets something a little different from each book. Critics (and bloggers) often seem to forget this. Grimdark is in the eye of the reader.

While we are on the subject. What exactly is the problem with portraying politics and war in a dystopic fashion? I’ll be honest with you, if I read a book portraying war in a pastoral fashion at this point I would find it far more suspect than Grimdark. It has taken us many, many brutal lessons but we now view war mostly as a last resort. In ages past, this was not the case. War has often been glorified and sought after, something which could be disastrous in the modern age. While Abercrombie might be writing about guys with swords, my guess he is making points about modern wars (and politics/leadership). Quite honestly I feel that Grimdark should be the default portrayal of warfare in Fantasy as it is in pretty much every genre. For good reason. Seriously. I don’t want to go back to romanticizing warfare.

That said, I’m still down for something like Starship Troopers every now and then.

[image error]

Seriously NPH was in Starship Troopers.

April 2, 2013

Teaser Tuesday

Teaser Tuesday:

The Qualifying Tournament, put forth to all ranking Green faction members, took place in Frostbay, the largest city north of Krass. The city sat on the southern edge of Lost Kingdom Bay, a vast body of water which was once the centre of a Kingdom so thoroughly destroyed in the Reckoning that not even the Chosen could agree upon its identity. The grand docks of Frostbay were the best known architectural remnants of said Kingdom. They jutted hundreds of feet out into the bay, and could accommodate ships of almost any keel depth for their entire length. This made Frostbay the collection point for the resources of the north; anything too difficult to move by road, or air went through the City.

Rail lines had been added to the city in recent centuries, bringing elemental powered steam engines and the newer artifice engines as well. Coal, oil, iron, silver, gold, timber, ironwood, mithril, and other goods flowed into the port. Trading houses and Great factories sprung up to take advantage of the

The city was a free city, like Krass, beholden to no single Chosen. As such it attracted the support of people from all over the Domains.

A little bit about the city of Frostbay, where the greens hold a pre-qualifying tournament for a larger event. It needs a bit of expansion, especially on landscape details, and I do wonder if I like the Railroads.