C.P.D. Harris's Blog, page 79

March 10, 2013

Joan of Arc: A Fantasy Archetype

“Consider this unique and imposing distinction. Since the writing of human history began, Joan of Arc is the only person, of either sex, who has ever held supreme command of the military forces of a nation at the age of seventeen.” Louis Kossuth

To note that the late medieval period was not known for its kickass female heroines is a bit of an understatement. But fourteen years after their disastrous loss at Agincourt, France was dragged out of its torpor by a seventeen year old woman who claimed to have god on her side.

A Statue of Joan.

Joan of Arc (Jeanne D’arc, properly speaking) is a controversial figure in history. She began her life as an uneducated peasant and before she was burned at the stake at age nineteen she had earned the respect of many of the french nobility as a battlefield strategist. There are eyewitness accounts of her surviving some rather nasty injuries such as an arrow to the neck and a stone cannonball to her helm while scaling a siege ladder. What is not in doubt is her importance to the French army: she rallied the troops when no one else could, turning the defence of France into a religious crusade and taking back much of the territory held by the English. Her crusade was cut short when the English broke truce, capturing her, and condemned her as a heretic to cast suspicion on her role in Charles the VII’s coronation, and burned her at the stake. The Vatican later retried her posthumously, after the war, and found her innocent: a testament to her popularity. She was later canonized, becoming a Saint in 1920.

Some historians argue that she was simply little more than a figurehead, but this has lately come under attack since the primary sources of evidence used in many of these arguments were from the rather unfair trial that led to her death.

However, as a role-model for women in general and as an archetype for female characters in Fantasy Fiction Saint Joan’s role is unquestioned. Here are a few reasons:

1) Fighting Woman. Joan wore a man’s clothes and cut her hair short, a popular device for female characters who take to the field. Joan did this out of practicality more than anything, since fighting in women’s fashions at the time would have been out of the question, but it certainly sets the stage for Characters like Tolkien’s Eowyn and other strong willed women who join their male brethren, disguised or not. When confronted about her immodest attire at her trial she responded.

“I was admonished to adopt feminine clothes; I refused, and still refuse. As for other avocations of women, there are plenty of other women to perform them.” Joan at her trial

Many of the tales of Joan have her fighting, saving her male colleagues from death, planning and leading battles, and trying to escape captivity by jumping out of a seventy foot tower with only a dry moat to cushion her fall. This is certainly in line with some of today’s more badass female characters and not bad at all for a seventeen year old girl who did not have the same training as the Knights and soldiers of her day.

2) Destiny, Divinity and Martyrdom. Joan follows the archetype of a heroine chosen by fate. She hears God one day, out of the blue, calling on her to unite France. She never doubts this voice or her own sanity, and her conviction is so strong that it pulls in those around her, converting those who doubt and revile her, even earning sainthood after death. She leads her armies to many Victories, often against odds that daunted the best commanders of her day, and seemed so convinced of her own cause that she neither did not fear death in battle and faced her trial with a courage that resonates to this day. Although her cause came from god, it can be noted that it also spurred French nationalism.

“She turned what had been a dry dynastic squabble that left the common people unmoved except for their own suffering into a passionately popular war of national liberation.” Stephen Richey

Regardless, in death she became a powerful symbol, and continued to rally the French until the end of the hundred years war.

3) Humble Origins. Not only was Joan a woman, but she was also a peasant from a small village. The idea of a member of the lower orders making her way across France and into the army and eventually aiding in the coronation of a king is worthy of many a tale just by itself. Humble origins resonate with modern readers, who have a soft spot for characters who start low and rise to glory. Joan is one of the greatest lower class heroines, moreso because she was actually accepted by her noble peers after proving herself to them and overcoming their prejudice. It is also worth noting that despite her origins, Joan was a great supporter of the monarchy, a fact that made her a hero to monarchists as well as commoners.

4) Betrayal and Tragedy. Despite Joan’s amazing rise to glory, her story is cut short rather quickly and she meets a tragic end. Many followers of the story accuse Charles VII of being too timid in coming to her defence, and some even note that he feared her popularity. It is a compelling element, one which would be at home in many of today’s darker works. The courage with which she faced death, the horrific nature of her execution and the viciousness with which they treated her remains only adds to the tragedy. She is an excellent example for characters who rise to greatness only to be destroyed by a world that they seem too good for.

“Joan was a being so uplifted from the ordinary run of mankind that she finds no equal in a thousand years.” Winston Churchill

5) Rape. Joan did not have a special fear of rape, despite her desire for chastity. Some histories note that she avoided “molestation” by wearing men’s clothes, while others say she had to fend off the attention of at least one English nobleman while awaiting her trial. It is possible that this attack might even have been partially motivated by a desire to destroy her purity and malign her. An ugly situation, and one I am loathe to write about, but certainly a modern theme.

6) The Voices in my Head. Joan can also be used as an archetype for more complex heroines. Perhaps despite her outer confidence in a god-given destiny she is riven with doubt. Or maybe the voices are just an excuse to get her into the fight, a way of convincing others to let her do her part. These interpretations could work very well in modern tales.

In all Joan of Arc is an excellent template for a modern female hero. She breaks the gender barrier. She overcomes humble beginnings to attain nobility and Sainthood. Despite her flawless courage and sense of destiny she is selfless and dedicated to her cause, even when it leads her to death. While she might seem to lack the complexity of some modern characters, interpretation can lead to interesting takes on her legend and the way that society reacts to such a glorious abberation makes for a wonderful narrative by itself.

March 7, 2013

Fate and Causality in Fantasy, a primer.

“There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance.” – Socrates (attr)

It is hard to find a decent dictionary definition of fate. However, for the purposes of this article, which deals primarily with fiction and a little bit with politics, fate is is a deterministic outcome that defies rational cause and effect. Fate has a long and storied tradition in literature. The Greek playwrights of old preferred using fate as a device, possibly because they wanted to to focus on the reaction to an event and thus obfuscated cause. While the Greeks certainly understood cause and effect, their dramas were more about evoking an emotional reaction. It doesn’t matter how Oedipus comes to kill his father and marries his mother, is is prophesied that he will do so and that’s that. Indeed Oedipus journey seems kind of random when you read it: he keeps running into strange tests and wierd characters on his way to fulfilling the prophecy. I mean seriously, what does the Sphinx have to do with anything? you could mix up the individual scenes in the middle part of his journey and it would barely effect the story. There is no cause and effect beyond the prophecy. The idea was to invoke pathos in the audience, a sense of common human failing and helplessness against an uncaring universe. Fate is good for this, because if we could see cause and effect in Oedipus’ journey, we might feel less sympathetic. It is an interesting device.

Here are some of the more common uses of Fate in Fantasy fiction

1) Prophecy: Prophecy is the king of irrational causes and is very common in fantasy fiction. The prophecy contains information about an event that will happen in the future. It can be deterministic and unavoidable like the prophecy given to Oedipus’parents or it can be a sort of if/then statement wherein if a certain set of conditions is met at a certain time: BOOM payoff. This second form of prophecy is very popular in modern fantasy, as it sets up a sort of race to see who controls the outcome or if it can be foiled. Often much of the fun is in seeing how events line up in unexpected ways to create the effect predicted by the prophecy, no matter how much the characters try to avoid it.

The causality of prophecy is usually Prophecy –> doesn’t matter = Effect or Prophecy Conditions –> Conditions met (y/n) = Effect if yes. Some authors can be very clever with this device and part of the fun is how convoluted it can get.

2) The Gods: In the Homer’s Odyssey, the Hero Odysseus has offended several of the gods because of his role in the fall of Troy. They influence nature itself to rebel against him sending him to several seemingly unrelated places and hindering his journey. Again, the island of the cyclops or Circe’s domain could be moved in continuity without changing the story much, other than having to re-arrange the number of dead crewmen. Odysseus is gonna wander until the gods get tired of tormenting him, or a friendly god intervenes. In the end, he could have walked home in less time (Should have hitched a ride with Xenophon, I guess).

The Causality here is God Interferes = Effect, often in a series of semi-related events. The god might inflict some misfortune at point A, then another at point B, and another at point C in the narrative. Interestingly some modern authors have reversed this. I’m thinking of Victor Hugo here, where the priest saves Valjean and this little act of kindness ripples throughout the whole narrative, the idea being that God lives in that kind act.

In some cases a callous system can take the place of a cruel god. In these stories the tragedy is unavoidable and the system is beyond cause and effect, and largely ineffable.

3) Destiny: There are quite a few stories in fantasy that involve characters with destinies. They are destined to do a particular thing and are driven to fulfill that task. They rarely waver from their course, and because of this have rather fallen out of favour in the modern day. Rational causes and effect make for a vastly superior linear story because it is more relatable and engages our thought processes. Destiny can also be used as a positive form of Doom, a event favours the character without a sensible cause or effect. A boy randomly finding a magic sword that sets him on the path to greatness, for example. (Although you could follow causes for an even more interesting tale, just how did that blade get there?)

4) Doom: In normal usage, people lash out against fate when they feel that they are wronged by an event that they had no control over. If your arm gets broken by a falling tree branch on a perfectly calm day you would likely curse your luck or rail against fate. There is likely a rational explanation for the breaking of the branch, but not too many people would follow that complex layer of causes. Its just easier to blame fate, especially if that first bad event leads to a second, like losing your job because said branch breaks your arm and you are then late for work. Doom in literature posits an uncaring or downright hostile universe, where bad things happen for no particular reason, often randomly. People will always be poor. Wars cannot be avoided. Life sucks. Some authors use this device brilliantly, using savage chance to evoke the frailty of life or just write a wicked western. Other writers use it lazily and would be better off showing us why things suck so badly in their world. “It just does” only cuts it if you are really good.

In rhetoric “that’s just the way things are” is often used a smokescreen; people are often lured in by this because it is easier to follow than a complex chain of cause and effect.

Modern Fantasy also has plenty of novels that are based on rational cause and effect. Tolkien makes good use of cause and effect to tell the story of the fellowship in Lord of the Rings. The properties of the ring are well defined and the journey mostly makes sense moving from A to B to C in a rational fashion all the way to mount doom. One of the reasons that Tom Bombadil frustrates me so much is that he breaks this sense of causality, appearing out of nowhere and then disappearing entirely from the story for no discernible reason. I mean seriously Tom, we could use your help against Sauron over here bud.

More recently, the Dresden Files follow the style of detective novels where the narrative is driven by the main character following causal links from a catalyst event to the final confrontation. The main character, Harry Dresden, usually uses the event, often a murder or some weird magical happening (frogs!), to determine suspects, motive, background, and rationally predict outcomes (although he often fails at all three) in a very rational manner, despite dealing with supernatural elements. Because we can follow Harry’s line of reasoning, we are tied into to the story. This creates a very believable world despite the use of Fantastic elements.

Of course cause and effect also have their limits, especially in Fantasy. Many a great magic system has been over-explained, for example. More on this later.

March 5, 2013

Teaser Tuesday

The overview of the parade from the second to last chapter of Bloodlust: Will to Power.

The Parade of Champions is the only day that business Krass truly grinds to halt. The new years festivals each year still see trade in hospitality, transportation, and the various black markets. However even the most illicit of trades grind to halt during the Parade of Champions, a display that leaves even pickpockets and whores awestruck.

Assassinations were not unheard of during the history of the parade, but the with the Capital Legions and the Chosen themselves on hand, these were considered a rare possibility that no true player of the game would try. Behind the scenes the Blackcloaks and the Hearthbound cooperated with the city’s underworld to ensure peace in the shadows. Riots were a more common problem, but the routes had been redesigned to spread the crowds out throughout the city and minimize the chances of a stampede.

Each of the Champions make their way through the streets in a grand procession starting in the Campus Martius, and ending in the immense parade square in front of the Grand Arena. Legionnaires, Master Gladiators, Chosen, and Grey-Robes line the streets, along with large crowds. The parade touches on every part of the city, all but the very worst areas, allowing every citizen of Krass to see their Champions in all full glory with a minimum of jostling for space.

It lacks polish and even has a few errors. It is somewhat expositional. If the book were structured differently I would roll this into the active description of the parade. As it is I will beautify it, cut the fat, and move on.

March 3, 2013

Lancelot: What makes a diamond interesting?

“in all turnementes, justys, and dedys of armys, both for lyff and deth, he passed all other knyghtes – and at no tyme was he ovircom but yf hit were by treson other inchauntement” Le Morte D’Arthur (Malory)

[Translation: Lancelot was the best of the best, the greatest champion of the elite Round Table Knights. He was a badass for sure. -Chris]

Lancelot is not my favorite of King Arthur’s knights; I much prefer Sir Gawaine, truth be told. I actually named the male lead in my first book Gavin, a modern form of Gawaine. Be that as it may, in modern tales of the round table, Lancelot is always front and centre. The tragic love triangle between King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, and Lancelot has dominated most modern versions of the ancient tales of Camelot. Lancelot himself provides an interesting archetype for heroes in modern fantasy, the perfect warrior torn between duty and his own desires.

In almost any version of the story Lancelot is the most skilled of the Round Table Knights. This is quite a distinction, considering King Arthur’s court attracts the best knights in all of Christendom. He wins all of the tournaments, kills giants single handedly, beats most of the other knights in duels at least once. He storms castles single handedly, wrecks enemy formations in battle with sword and lance, and generally makes everyone else look second rate. Sure, many of the other knights have their claim to fame, but Lancelot is without question the best of them all, at least in most Arthurian tales. He even had better stats in the D&D books, although Gawaine had a cooler power.

Amazing Piece by Donato Giancola. Blows my mind. Pic links to site. (Used without permission)

In battle at least, Lancelot was the very definition of Mary Sue. It is hard for us to maintain dramatic interest in a character who always wins.

Lancelot was not just a tournament-winning, lord of war; he was also the most charming of Arthur’s knights and the king’s closest friend. Most interpretations place Lancelot’s social graces on par with his peerless fighting skills. He is polite, handsome, and skilled at all the arts of Knighthood. He is dutiful, bringing great honour to his king. He is also Chivalrous, often helping the less fortunate and showing great hospitality and respect towards the fairer sex. (T.H White does make him ape-like and ugly, even nasty, but that is not the norm.)

This is a little more interesting. The romantic potential of the great knight is certainly something that interests modern readers. It’s still not enough though. If we left it at this the character would be a perfect hero, and would only be exciting as a love interest in period romance novels or light-hearted action.

No, the real reason that Lancelot is interesting and important to modern is that despite his near perfection in every single aspect of Chivalry, Warfare, and Romance he has a fatal flaw. Lancelot and Guinevere fall in love, and their love is one of the keystones of the downfall of the perfect realm of Camelot. In Malory Lancelot and Guinevere are more or less driven together by fate. In more modern tellings it is lust and imprefection that drives them together. The best modern version, in my opinion, is T.H. White who has Lancelot as being initially jealous of Guinevere because her presence disrupts his relationship with Arthur (Yoko breaking up the band I guess). Arthur can’t have his best Knight at odds with his queen, and so forces them to spend time together (oops).

Regardless of the telling, Lancelots inhumanly perfect outer shell disguises a heart full of very human desires. His incredible skill only serves to increase the heights from which he inevitably falls when he finally gives in to his desire. When Lancelot and Guinevere commit adultery and betray Arthur, the realm Camelot is denied two of its pillar characters and tragedy is inevitable, even without Arthur’s other problems. Lancelot is the archetype of a man driven to greatness but humbled by his own inner demons. He betrays his friends, his realm, and ultimately himself. That is more interesting, and a story we can all relate to. In this case Lancelots power only serves to magnify his failings. A serf commiting adultery isn’t going to cause the realm to collapse, after all. The same is true of the Lannisters in A Song of Ice and Fire, their particular infidelity would not matter as much if they were not so elevated. A very modern archetype, indeed.

However the tale of Lancelot does not end in utter desolation and failure. The great knight wanders, mad and seeking redemption. Eventually he finds it by joining Arthur and the last of the round table knights in the great battle against Mordred. Even in the face of his own betrayal and sundered from his lord, Lancelot performs his duty one last time. In this he completes the cycle and rises from his fall, passing into legend. In some version fo the tale he falls alongside Arthur. In others he visits his queen one last time, platonically, before they both retire to contemplation. This forth part, the potential for redemtion, elevates Lancelot even further.

I am often minded of Darth Vader when I think of Lancelot. Anakin Skywalker begins as the potentially the greatest Jedi Knight the order had ever. His love leads to his downfall and a betrayal of the order. He is redeemed when he turns against the Emperor to save Luke, who is the last Jedi Knight. Perhaps if George Lucas had taken a bit more from Arthurian myth, I would have enjoyed Episodes 1,2, and 3 more.

“Guenever never cared for God. She was a good theologian, but that was all. The truth was that she was old and wise: she knew that Lancelot did care for God most passionately, that it was essential he should turn in that direction. So, for his sake, to make it easier for him, the great queen now renounced what she had fought for all her life, now set the example, and stood to her choice. She had stepped out of the picture.

Lancelot guessed a good deal of this, and, when she refused to see him, he climbed the convent wall with Gallic, ageing gallantry. He waylaid her to expostulate, but she was adamant and brave. Something about Mordred seems to have broken her lust for life. They parted, never to meet on earth.”

― T.H. White, The Book of Merlyn

Lancelot is a powerful character who is deeply flawed. His power makes him a pillar of the realm. His good qualities make him attractive and successful. His humanity makes him vulnerable. His ability to overcome his fall from grace and redeem himself makes him a hero. Modern readers love flawed, human characters and Sir Lancelot has certainly earned his place at the table in this regard.

Afterthought: is Sam Gamgee is the inverse Lancelot?

February 28, 2013

Stopping the Pendulum

This week, while I was perusing my reddits I noted an excellent bit of writing by author Joe Abercrombie, musings on the merit of grit in Fantasy. Here is a link, read it or skim it (I’ll wait). I am shamed to say that the only book of his that I’ve read is Best Served Cold. I can’t decide if I loved it, or thought it was merely well written but not to my tastes. I have no qualms about loudly proclaiming the value of his piece on grit, however, and will loudly encourage everyone to read it, possibly even abusing my linking privileges.

What caught me is the idea that Fantasy often swings between two opposing points, a pendulum of sorts. One point is represented by gritty fantasy, which many feel is more realistic and more dramatic. The other point is represented by a more romantic style, which deals with high morality and pure wonder. In truth most books fall far short of either pole, but the idea of a pendulum swinging between the two is an accurate description of the constant tug of war in Fantasy since the genre become commercially viable in paperback form.

A Pendulum. Think Poe.

Every few years it seemed while I was growing up fantasy would start to advertise how this new crop of writers was grittier and edgier, after that played out for a bit a triumphant return to good ol’ classical fantasy would be announced. This happened, in my mind at least, over and over. By the time George R.R. Martin came along I was quite tired of this dichotomy and had read enough of the genre old and new to see it as just another bit of theorycraft. As a reader I enjoyed both types of books, so long as they were well written and in-line with my current interests. I would be happy if I never had to endure another discussion about which type of fantasy was better. In fact I would like to destroy the pendulum and bury the broken remains in some remote location where only the most diligent of theorycrafters can dig it up.

You see, as mr Abercrombie notes, grit is just part of the range of modern fantasy. I agree with this wholeheartedly. The genre is big enough for any well-written book be it gritty or as bright and cheerful as it gets. The readers will decide what they want to read, and if people I know are any indication many of them will enjoy both points of the pendulum and everything in between.

Fantasy is a growing genre. It is expanding into new eras and areas. It is dealing with new ideas that older works never visitted. Industrial age fantasy explores the wonders of invention but also the grim side of urbanization and alienation. Modern and Urban fantasy, and paranormal romance explore the same issues from different angles producing wildly divergent types of fantasy that attract new readers to the genre and give old readers new playgrounds. Why would we want to hinder this?

What you like is a matter of personal taste. Any serious person comes to realize that others do not always share their tastes. Some theorycrafters try to edify their own personal tastes with grand constructs, “laws”, and long articles on how the style that they prefer is the “one true Fantasy”… As if anyone in their right mind wants to reduce the genre to the narrow paths it once trod. All these arguments can be reduced to personal preference, and all the effort wasted on them could be better spent writing more books. The readers will decide what they want to read.

The clash between gritty and classical fantasy is a false dichotomy. We can have both. Both can be good. Game of Thrones is awesome gritty fantasy. Lord of the Rings is also well regarded, I hear. Many readers enjoy both. Any arguments that say one style or another corrupts the genre are ultimately self-serving and false.

Each author and each book, and each world in Fantasy is like a lens through which the reader can peer and catch a glimpse of something new and wondrous. People will often gravitate to the lenses which work best with their own views of the world, either fortifying or challenging them in the way that they need. Since the world is full of people with different views, why would we want to limit our range of fantasy experiences? It just seems dumb to me. If I don’t like a book I don’t have to read it. Books that I don’t like won’t ruin the genre. Fantasy has outgrown this old argument. So let’s cut the pendulum down, burn it, bury the ashes and move on.

P.S: It Occurs to me what I really appreciate about the Abercrombie article is that he acknowledges that grit is an artist’s tool and that he does not even try to slam “opposing” styles of fantasy. He simply notes what grit adds to the genre without trashing anyone else. Nicely done. Proof, in my mind, that we have started to move beyond this already.

February 26, 2013

Tuesday Teaser

Gavin did not try to plant his spear to impale the charging Armodon: the larger Gladiator’s war-maul gave simply him too much reach. Instead he waited for Omodo to swing, a broad sweep low to the ground, and leapt over the weapon, jabbing the wicked point of his war-spear at Omodo’s face. Anticipating this, the heavier armoured Gladiator shifted to take Gavin’s spear thrust on his shoulder plate and then slashed with his horn.

A rough scene from Bloodlust: Will to Power. Feel free to comment.

February 24, 2013

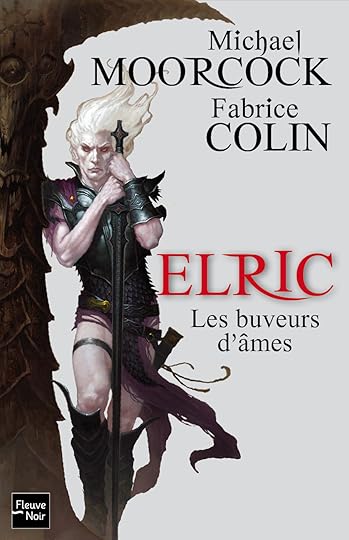

Elric of Melnibone and complexity of character.

“Bound by hell-forged chains and fate-haunted circumstance. Well, then—let it be thus so—and men will have cause to tremble and flee when they hear the names of Elric of Melinbone and Stormbringer, his sword. We are two of a kind—produced by an age which has deserted us. Let us give this age cause to hate us!”

― Michael Moorcock, Elric: The Stealer of Souls

Elric is another character I first encountered in that old D&D Deities and Demi-gods. I must admit that I am not a huge fan of Michael Moorcock, and yet his most popular creation is seared into the fabric of fantasy literature and even into my brain. Elric, the restless Emperor of a decadent, the albino swordsman and sorceror whose genetic defects leave him nearly crippled without drugs or magic. Elric wielder of the evil, soul-drinking sword Stormbringer, itself one of the most Iconic weapons in fantasy fiction. Elric, whose complexity as a character often defies categorization, perhaps even by his creator.

As an iconic character Elric’s influence can be seen in Sephiroth from Final Fantasy and Geralt from the Witcher series, as well as a host of written works.

In appearance Elric is fairly unique. He is both elfin and demonic, beautiful and broken, his exquisite pedigree and his awful weakness are immediately apparent and easy to visualize. In fantasy canon, Elric is certainly not the manliest of leading men with no hint of a broad chest, powerful physique, or square jaw. He is exotic and unusual, his appearance working to prepare the reader for his unique personality and story.

In terms of power, Elric is off the charts. He is among the most best swordsmen in the world and also among the best sorcerors. He is the ruler of a powerful empire. He consorts with Daemons, Gods, and powerful spirits, many of whom are bound to serve him through ancient pacts. His sword drinks the souls his enemies and gifts Elric with some of their strength, increasing as he kills. When he is at the top of his game, Elric seems invincible, and yet if one catches him without his herbs or sword, his is frail and as weak as a kitten. He sets the standard for many modern characters in this regard.

Elric’s intelligence and curiosity, along with his defiance of conventional morality are also traits that have been passed on to modern Fantasy.

Mentally, Elric is an extremely complex character. He battles with ennui. He feels out of place in his world, rejected in his own society because he is not their ideal Emperor and feared in the young kingdoms because of his birthright and the fact that he tends to be the harbinger of ill omen. He is curious and compassionate. He perpetrates brutal massacres. He is passionate, doomed, and more than a little unbalanced. Interestingly, if you are willing to engage in a little dirty rhetoric, you can argue that Elric belongs as a hero or an anti-hero, is tragic or triumphant, or is his own beast entirely.

Many people would scoff at the notion that Elric is a true, classical hero. He follows the standard hero of the monomyth pattern fairly closely, leaving the comforts of home, heeding the call to adventure, and ushering in a new age. He may not follow conventional morality, but he is the most compassionate and curious of his kind and acts consistently within his own understandable morality, at least until the sword drives him mad with bloodlust. In this he seems quite close to some Norse and Celtic heroes, particularly Cu Chulainn. You know, the type of heroes that you want on your side of the battle, but would avoid making eye contact with if you met them on the street.

Elric is often presented as an anti-hero by critics and readers. He certainly laughs in the face of conventional heroic qualities. He does whatever he wants most of the time, often causing great damage to the world around him. he revels in sex and drugs and strange magics. Yeah, pretty easy to see why this label is applied to him.

You could even argue that Elric is a reader identification hero. Despite his power, he is a sad and vulnerable man who often feels like he does not belong in the world around him. We see the young kingdoms through his eyes, cynical and yet not blind to the fantastical. This is an attitude that many young fantasy fans can identify with. At times he even seems caught between youthful idealism and cynical adulthood, crushed by the burdens and expectations of an uncaring world and yet defiant still. Themes of alienation resonate with a culture of outsiders.

Moorcock himself once noted that Elric was a “doomed hero”, a tragically ill-fated man who struggles against his own destiny in the vein of ancient heroes like Gilgamesh or Lancelot, whose efforts are ruined despite their power. This fits Elric well, although he does not aspire to greatness or even good, and often seems to just wander into adventure, much like Conan, but with worse luck.

In fact, an astute reader can approach Elric from almost any philosophical angle and find purchase, something to define him in the way you want to see him. Maybe it is because his creator keeps coming back to the character, adding new stories decades after killing him off. Or perhaps the character was always thus, as defiant of our desires to define him as he is of his of the mantles he was born with. Elric is an intricate character, powerful and yet frail, heroic and and yet amoral, and always without a doubt, interesting and conflicted. The most enduring legacy of Elric is his complexity, a complexity which blooms to its fullest in a unique and interesting fantasy world.

February 21, 2013

Conan: a modern archetype?

“Hither came Conan the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.” Robert E Howard.

By the time the Hobbit was first published, Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories had been circulating for several years. While Tolkien’s literary legacy is much more celebrated, it is hard to find a Fantasy fan who hasn’t heard of Howard’s greatest creation: Conan. Conan is one of my favorite characters, an uncouth savage who lives by the blade, and is only interested in women, gold, and adventure. He is unabashedly resistant to civilization and about as politically correct as the loincloth that he is usually depicted as wearing. He fits in very well with many of the modern anti-heroes, and the trend toward character driven fiction in general.

While many of Howards stories are tainted with racism and sexism, his Conan character has endured the transition to modern day, and perhaps even thrived. I first encountered the Black-maned Barbarian through D&D; he was a demi-god in the Lovecraftian pantheon in the original Dieties and Demigods. In other words the mighty Barbarian graced the same section of the book as Cthulu. This alone garnered my interest, I mean not just any old hero can hang with critters like that.

“What do I know of cultured ways, the gilt, the craft and the lie?

I, who was born in a naked land and bred in the open sky.

The subtle tongue, the sophist guile, they fail when the broadswords sing;

Rush in and die, dogs—I was a man before I was a king.” The Phoenix and the Sword

My next exposure to Conan was the wonderful comics. These were actually the first comics of any sort I got my grubby little hands on. Brutal fighting, a brooding anti-hero, blood and babes. Conan really thrived in comics, and I credit them with keeping Howards character alive and refining him for new audiences. With any other character I would say “modernized”, but no one modernizes a Barbarian! Comics created the image that most Fantasy fans associate with the Barbarian. The comics also created a great supporting cast, and went crazy on the battle scenes and wierd monsters. Many of those artists cut their teeth on Conan and then moved on to other projects, carrying their influences with them. There certainly is a lot of Conan art out there…

Of course the most famous Conan quote is probably this one.

The first Conan movie is actually quite good. A subtle meditation on the true meaning of strength holds the story together and makes it more than a simple action film. James Earl Jones makes a superb villain and Arnold does a pretty good job of bringing the Barbarian to life on the big screen. What really makes the film work is that it collects all of the elements of Conan’s backstory and weaves them into a digestible whole, in some cases re-writing them for clarity and drama. It is a decent two hour introduction to the brawny Cimmerian.

So, why write about Conan? Well it is my belief that many modern characters in Fantasy fiction are influenced by Conan. The influence of sword and sorcery style is easy to detect in many of the grittier tales of modern Fantasy where characters reject conventional morality in favour of their own personal, often amoral goals. Here are a few of the defining traits of the Barbarian, and how I think they influence modern works.

1) By Crom! Conan believes in the Gods. However, he doesn’t really like them. The god of his people/tribe is portrayed as a rather grim figure who gifts a person with certain qualities, like strength, and then sort of ignores them until they die. Throughout the books Conan encounters the gods of other tribes, often interacting with them in interesting, and violent, ways.

2) Savagery. Although Conan follows a code, he is not chivalrous, honourable, or civilized. He fights in a no holds barred fashion that is highly appropriate for the age of MMA (Ulimate Fighting). Battles in Conan are always over the top and bloody, and the body count is usually very high on all sides. The only character guaranteed to survive, though often half-dead, is Conan. Modern fantasy is often explosively violent, and I can detect a lot of influence from the comics carrying over to novels as well as video games.

3) Stealth. For such a big dude, Conan is surprisingly agile and stealthy. He can scale nearly any wall, walk a tightrope without pause, and has a knack for breaking and entering that would make a cat-burglar envious. Modern assassin characters actually bear more resemblance to Howard’s Barbarian than their suicidal, drug driven historical counter-parts. Maybe thats why they all kick so much more ass in a fight than you would expect from someone who always kills from the shadows?

4) Morality. The Barbarian abides by his own rules and desires. If Conan does anything good, it is purely coincidental or based on personal motivation. He does not follow any higher morality or philosophy. Bad guys die because they get in Conan’s way or he is paid to kill them, not because he judges them to be evil. This is fairly relevant to a large section of modern Fantasy, which is dominated by darker heroes. They tend to be more urban and urbane, with notable exception, but the pedigree is fairly obvious.

5) Sex. It just isn’t a Conan story without sex. (as well as plenty of muscled Barbarian descriptions) Even the PG comic didn’t shy away from the fact that the Barbarian was always carousing. Conan was nearly as famed for his sexual prowess as for his capacity for carnage. His endless womanizing gets him into and out of trouble. Modern Fantasy often deals with sexual themes, and Conan would fit right in with many characters.

Not bad for a Character from the early 1930s.

February 17, 2013

Horses, Hounds, Hawks, and Cats: Domestic animals in Fantasy.

Last week I ruminated on the role of transportation in world design. Naturally this got me thinking about horses, which were an integral part of the middle ages and many Fantasy narratives. Thinking about horses got me onto

another subject for fantasy narratives: Domestic animals. The most obvious of these are horses, dogs, hawks, and cats, all of which have a strong presence in history as well as Fantasy fiction. However, world-builders often like to take the roles occupied by common creatures and insert new and interesting varieties

Horses were one of the earliest forms of human transportation. They are also well represented in fantasy, from nameless horses all the way up to the near-divine Shadowfax from Lord of the Rings. In the European middle ages a personal horse or two was a sign of serious wealth, and provided a transportation advantage over the footbound that was hard to match. Horses required stabling hitching posts, and certain types of feed, all of which are well represented in fantasy novels. Horse gear is also fairly well represented with saddles, horseshoes, and barding being fairly common fantasy topics. The purpose of a horse is fairly obvious, although specially trained warhorses

that can stand the din of fighting (or even canon-fire) are less well noted. I’d say the horse is likely the most well represented of domestic animals in Fantasy. Horse even have numerous fantasy variants, from unicorns and

pegasi to skeletal steeds and nightmares.

Dogs come in a close second in most fantasy settings. Man’s best friend is truly versatile, but few authors in the genre really delve into dogs these days. Domesticated dogs are obviously useful for hunting, and frequently show up in the obligatory hunt scene where some important personage gets ambushed or lured into danger (which, despite my irreverent language, is a favoured scene type of mine). We also see hounds being used to track down criminals in a different kind of hunt. A few books have fighting dogs and named companion dogs, which make for great characters if well written, but sadly the hound has less glamour than the horse these days. I also feel that with the prevalence of stealth as a superpower assassins in modern fantasy, we are conveniently forgetting just how hard it can be to sneak past a good guard dog. I know if I lived in any of the modern urban fantasy settings I would keep some bad-ass hounds to offset the constant attacks from the shadow. Hounds can also be very villainous: the conquistadors fed certain dogs on human flesh and use them as weapons of terror. Dogs have a few fantasy variants, with infernal hounds and the hounds of the wild hunt being the most common. I think we can do better, Dog Lovers.

Hawks and other hunting birds receive more attention that Cats in Fantasy fiction, particularly in anything involving the aristocracy. Falconry was another form of hunt, and yet another chance to engage in a mad outdoor

activity with cool gear. A few fantasy ranger types have had faithful bird companions, and owls and ravens are common familiars.

Cats rule the internet in modern day, but they seem rather under-represented in modern fantasy with Domestic versions getting far less page-time than their wild counterparts. Cats, of course, play an important role in pest

control, which is not often worthy of writing about. They do show up as witches familiars now and then. Kinda sad for a creature that the ancient Egyptians considered semi-divine.

Of course, Fantasy creatures can fill any of these roles. However a society that uses giant crabs as mounts is going to be somewhat different than one that uses horses, at least if the writer cares at all for depth in world-

building. There are a few considerations when introducing new domestic animals to your world, even if it occupies a fairly common role like mount. Lets take Dragons as an example: they are a familiar staple of Fantasy fiction and occasionally show up as domestic animals.

1) What does it do? Consider what role the animal is going to fill in your society. Domestic Dragons make great mounts and war-beasts, and intelligent varieties can even act as advisors and mentors. This is usually the easiest

step. Mind you if your creature has unusual capabilities think it through… you won’t be keeping your fire breathing Dragon in a wooden rookery. The basic role the creature fills is important, especially if it fills a role unique to your world like pokemon or warbeasts from Hordes.

2) What does it eat? Fodder for your animals is tremendously important. If your dragons are large and eat prodigious quantities of meat it changes the world economy. If they require special food for their fiery breath,

that becomes a resources as well. What if they only eat people?

3) How does it breed? Domestic animals are characterized by breeds. Breeding animals allows for selection of desired traits which improve utility or appearance. Breeders of horses, hounds, and falcons were often famous and

wealthy. Breeding stock was a valuable resource. If Dragons have been domesticated their could be breeds, although if they are sentient then they might choose their own mates. Perhaps their are hunting Dragons, War Dragons, Guard Dragons, or maybe they are bred for colour or breath weapon. Those with the best breeds often have an advantage

4) Historical Factors. When did our creature become domesticated? How did it become changed from its wild counterparts? The history of popular domestic species often figures in to legends and myths. In fantasy this can be

take a step further. Perhaps your Dragons are a gift from the gods, were enslaved by powerful sorcery, or chose to live alongside humans as part of a grand bargain. This could really change your world.

5) General Characteristics. How common is the creature? How big is it? does it have an usual scent? what kind of diseases and parasites does it have? How long does it live? Does it bond to a single master? Can it be trained to

do complex tasks? Dragons as mounts offer the advantage of flight, how are your castles going to look when they take this into account from a defensive and a stabling perspective.

Details really make fantasy worlds come to life, even relatively simple changes can evoke wonder or even figure in to the plot. I am reminded of Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven where a gift of a herd of superior horses to a

relatively unimportant man upsets the delicate balance of an Empire. It is certainly worth consideration when building your world.

February 14, 2013

Bacon, Genre Mashups, and Valentine’s Day

Today the unthinkable happened: I ate something that tasted like Bacon and I hated it. I have long maintained that the kingly flavour of crispy bacon can improve any culinary creation. Maple glazed Bacon. Bacon sprinkles on ice cream. Bacon wrapped shrimp. Bacon wrapped bacon. And so on. Fortunately I am not wealthy enough to fully satisfy my appetite for the mightiest of porkmeats or I would likely have suffered some kind of bacon induced fatality (the tastiest form of death!).

But today I had my comeuppance in the form of a Bacon flavoured mint.

The bacon flavoured mint is an abomination, something dredged up from the twisted mind of a mad scientist who is overly fond of barbeque and pork based chemical engineering. Upon popping the tiny mint, I was greeted by a surprising burst of pure bacony flavour equal to a decently cooked slice of piggy’s finest. After a mere heartbeat this essence quickly changed, leaving an aftertaste that made me feel like I’d chugged a can of week-old bacon grease. Then the mint kicked in. Apparently bacon and mint are not friends. No sir, they do not mix well. It was absolutely terrible… I no longer have absolute faith in Bacon: may pork have mercy on my belly.

Now, what does this have to do with anything that isn’t silly or bacon-related?

The core lesson of my ill-fated encounter with bacon-mints is that just because I really, really like something does not mean that it has a place in everything I do. This is certainly true of writing.

Genre Mashups are big deal in gaming right now, and have started to have influence into writing as well. The basic idea of a genre mashup in gaming is to take a whole bunch of elements from different games, throw them together, shake until blended and then play. Kingdom hearts combines Disney with Final Fantasy and other Square Enix properties to create an epic adventure that is part anime and part classic Disney and somehow entirely original. The Shadowrun RPG blends a cyberpunk dystopia with the sudden return of magic including a large percentage of the world population mutating into Tolkien style fantasy races. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is a book that mixes Jane Austen’s period classic with flesh eating undead.

Of course, for every good mashup, there are many failures or flawed works. I remember my own attempt to mix cool Space Marine style power armour and a pure fantasy world. The characters were cool, but the world ultimately lacked any real details that would explain the presence of powered armour. I mean if the people of that world can create that kind of awesome technology, which is beyond our present grasp, then why wouldn’t they have cars and the flu vaccine. If the armour was a rare lost artifact of a bygone age, and thus powerful and rare, why was it in the hands of a group of people who were, at best, adventurers: that kind of power makes kingdoms, if not empires. I didn’t think it through, and the setting fell apart in a hail of rune enhanced autocannon ammunition (poor kobolds).

Yet for all the challenges, the allure remains strong. Perhaps my favourite mashup is the Dresden Files which mixes pulp detective fiction with every single cool magical fantasy trope that Jim Butcher can think of. The Genius of the Dresden files is that mr Butcher somehow manages to make room for all of these in his world without it seeming crowded or silly. That’s quite an achievement when one of the books involves four different types of werewolves (I’m not talking sub-types like clans here, but full-on origins) and another has a character riding a T-rex. Then again the author did write another series that blended Pokemen with a lost Roman legion, and somehow made that work too. I think what Mr Butcher does is integrate each element of cool carefully, and fully consider the implications to his world. In addition each element is usually directly involved in the plot, which makes it seem less like window dressing.

Steampunk is an example of a whole genre that works well with Mashups. Mad clockwork technology and ancient mysticism work very well in an early industrial age setting, partly because they had some real world believers at those times.

So let’s say I love zombies, but I also love Hellenistic epics. I can’t just throw zombies into the Trojan war and call it a setting, I have to consider how the blend of these two elements is going to work. What would the introduction of Zombies do to the Trojan war? A bad mashup would just follow the outline of the Iliad thow in some undead and call it a day. If the Zombies were infectious, they could quickly overwhelm the Greeks who have no walls to protect them. Some of the Greeks could escape to their ships. Achilles, would of course be immune to Zombie bites unless they got him on the heel. The Zombies would indiscriminately attack both sides, and the survivors would either escape across the sea or take shelter in Troy. Then there’s the divine angle. The Gods took a great interest in the Trojan war, and Zombies would definitely mean that one of them was meddling, answering that question could lead to a great plot point…

Then again, just because I think zombies are cool, doesn’t mean I should try to put them in everything.

As an aside, I was walking home from the dayjob at 11 PM this evening and noticed a whole group of people dressed up for Valentines day. I saw a guy dressed as a teddy bear escorting a pack of young ladies in full costume. Is this a thing now? If so, I approve!