C.P.D. Harris's Blog, page 78

March 31, 2013

Boudicca: An Archetype for the Ages.

“Boudicea, with her daughters before her in a chariot, went up to tribe after tribe, protesting that it was indeed usual for Britons to fight under the leadership of women. ‘But now,’ she said, ‘it is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, the outraged chastity of my daughters. Roman lust has gone so far that not our very persons, nor even age or virginity, are left unpolluted. But heaven is on the side of a righteous vengeance; a legion which dared to fight has perished; the rest are hiding themselves in their camp, or are thinking anxiously of flight. They will not sustain even the din and the shout of so many thousands, much less our charge and our blows. If you weigh well the strength of the armies, and the causes of the war, you will see that in this battle you must conquer or die. This is a woman’s resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves’ “(Tacitus, Lewis TR, 2010).

(I’ll stick to the Boudicca version of the name, though there are many other spellings. I just like Boudicca better.)

Boudicca stands out among popular images of warrior women. This is not simply because of her impressive physical appearance often portrayed as a savage celtic war-goddess with a mane of fiery hair, proud in stature, noted as having rather imposing stare and a loud, harsh voice. She seems custom made for dramatic renaissance portraits, the very archetype of the passionate, firebrand warrior-queen. More on how she breaks the stereotypes of pre-modern women warriors in a moment, first a little history.

A very nice picture from Robert Keegan.

Boudicca was the queen of the Iceni, a tribe that acted as a client state of Rome, allowed to remain relatively independent in the conquest of AD 43. Prasutagus, may have surrendered or may have been installed by the Romans, sources are unclear. It is well known that Iceni as a tribe were independent minded, having revolted once already in AD 46 when a governor tried to restrict their use of weapons.

When Prasutagus died, he left his property to his wife and daughters, not uncommon in Celtic law and certainly accepted by his tribe. The Romans saw it differently. In their practices a lesser client king would rule until his death and then his property would become part of the Empire. Roman Legions marched into Iceni lands, treating them as a subjugated people. Even worse were the Roman merchants and creditors, who greedlily called in all their debts upon the tribe seizing valuable land and anything else they could get their hands on. We all know the drill on this one. Their harshness would later draw criticism from other parts of Rome, and is certainly looked down upon in Tacitus and Dio, the main scources for this period.

Boudicca took a stand. It was not a violent one, at least initially. She showed her defiance to the Romans and so they flogged her (or beat her with Rods) and raped her daughters to add to her humiliation. Roman law was harsh, but this was noted as being excessive as well as stupid. The Romans were having trouble with subjugating the Welsh tribes and other parts of Britain, so perhaps this excess was based on that old desire to show one’s strength by humiliating others. Or maybe they just didn’t like the idea of a defiant woman, tall and proud, and most definitely foreign to their experience standing up to them.

Instead of chastising Boudicca, her vicious punishment enraged her and provided a focal point for the tribes anger. In AD 60-61 Boudicca led a revolt against the Romans. She played up her suffering and her daughter’s defilement over her noble heritage, winning the support of other tribes as well. How mighty of voice and will she must have been to challenge a power like the Romans without military schooling. It is no wonder that when tales of her deeds were uncovered during the renaissance she captured the imaginations of so many.

Boudicca quickly led her forces to sack Camulodunum (Colchester), a prominent colonial town. It is said she used the running direction of a hare as a kind of augury to choose her target, related to the British goddess of Victory, Andraste. She captured the town relatively easily, even inflicting a crushing defeat on the IX Hispania, a legion sent to stop her. Several Roman commanders fled in disgrace. It was a major blow.

Next Boudicca turned to Londoninium (London). Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, the governor, was force to give up his campaign in Wales to fight her. Paulinus was no fool, having served with great distinction in Africa and having waged many wars in Britain itself. He decided to give up Londonium to Boudicca while he retreated and gathered forces. This sort of retreat is a very successful tactic used by the Romans against Attila later on and even Sam Houston after the fall of the Alamo. After burning London to the ground, killing a staggering number of people in savage ways (although not savage for the times, I mean the Romans crucified people), Boudicca faced Paulinus on the ground of his own choosing as was unable to bring her superior numbers to bear: her army was crushed. She either poisoned herself or died from illness right after. Many rumours abound of where her body was hidden away. Despite this loss and her death, Nero considered pulling out of Britain after these events.

Initially the Romans were very harsh after their victory, but their methods drew criticism, since many felt that they would just provoke another rebellion.

Boudicca’s story is, on the surface, very similar to Joan of Arc’s. Both came out of nowhere, claiming divine inspiration, and let their people against In fact, Boudicca was often seen as the British Joan of Arc, and invoked to counter the french Saint. However, from a writer’s perspective Boudicca offers many differences.

1) Mom goes to War: Many of the classical women warriors are presented as young virgins. Boudicca was neither. The Flame-haired Warrior-queen had several daughters (who went to war with her, though we don’t know if they fought) and a deceased husband. When Sara Palin invokes the momma grizzly archetype, the avenging mother who brings fire and blood to those who harm her kids, she is calling down the spirit of Boudicca. The idea of a mature woman going to war resonates well with modern audiences. Women in modern day often juggle kids and careers, and the idea of an ass-kicking mom who leads a revolution against an impossibly powerful foe definitely appeals to some of them.

2) The Savage: Roman writers were as fascinated by Celtic women as modern movie audiences are by female action heroes. Boudicca is a prime example. She is ferocious and savage, a definite outsider praying to foreign gods and leading a massive army of painted savages to drown southern Britain in blood. Her viciousness towards the Romans is noted, although their viciousness towards her was worse and they aren’t exactly known as history’s most merciful conquerors. She represents the defiant frontiers, full of danger and strange (to Romans) customs. Her bloody destruction of Londonium is portrayed as an orgy of pagan savagery, at home in many of today’s grittier works.

3) The Woman: Despite her ferocity Boudicca maintains her feminine quality, exotic as well as deadly: unlike Joan and many subsequent heroines she never tries to conceal the fact that she is a woman, nor does she adopt male customs.

4) The Individual Defiant: When Boudicca revolted, Rome was powerful. Modern hegemony barely compares. To stand up to the Roman system of warfare and imperial colonization invokes a certain Romantic defiance that resonates to this day. One woman standing up the the cruelty of Roman soldiers and Roman merchants, becoming an example for years to come, despite her eventual doom. Fiction loves defiant heroes, and Boudicca is among the best of them. (Want Grimdark? try rebelling against the Roman empire)

5) Overcoming Suffering: Boudicca was tortured and her daughters were raped. She suffered brutal indignities but came out swinging. She converted her sorrow into power. Modern heroes are often marked by their ability to overcome suffering, and Boudicca fits right in here. In this case her family suffers along with her, adding to the indignity.

Boudicca is both an amazing historical figure and a fascinating take on the legendary warrior-queen. She opposes the patriarchal Romans wearing her womanhood as a badge of honour, crying out against injustice, facing her tragic end with head held high. She certainly sets a precedent for both Karmal and Sadira from my Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s Tale, and many other modern warrior women of fiction as well.

March 28, 2013

The Greater Divide: more fate and causality

I have written extensively (excessively?) about the Grimdark debate lately. My original thoughts of the matter still stand: Fantasy as a genre has grown large enough, with a diverse enough fanbase, that we can (and should) accommodate many styles and let the readers choose what they want to read. Puerile purists can still fight it out on their chosen corners of the internet, but they should let readers read and writers write. Gritty stories and even horrific ones, have earned their place in Fantasy, and they won’t displace pastoral and escapist fantasy any more than urban fantasy and steampunk fantasy will replace fantasy set in the medieval period. Its a big genre and I think all of these styles and sub-genres can co-exist, and, in the right conditions, thrive off each other. After all, the age of geek chic is coming, I tell ya…

That said I do feel there is a greater divide looming in fantasy, and in fiction (and politics, and life) in general. I’m thinking of fate and causality, my other go-to topic. In my mind these present a much more serious divide in fantasy than Grimdark and pastoral.

A Glacial Chasm. Art from a magic card of the same name.

While it is possible for fate and causality to co-exist in the same narrative, they are often at odds with one another. A fate based narrative posits that the story ends the way it does because it is meant to end that way. This can be prophecy or even a form of world-weary cynicism. A causal narrative follows a chain of cause and effect from beginning to end. To examine the divide between these two types of narrative I am going to use a simple and familiar version of each. For fate driven narratives I will use the prophecy story, for causal narratives I will use the detective story.

The Prophecy Story

This narrative is driven by a predestined event that will occur some time in the future. The prophecy might be the type that can be thwarted or it may simply be fully and truly pre-destined. Regardless the focus of the narrative is centered around this particular event. The characters are involved in the prophecy, often even if they are trying to avoid it. The structure of the prophecy story can be very loose, allowing a wide range of unrelated scenes that can easily be drawn together with the sense of destiny inherent in following a prophecy. The joy of a prophecy story is in seeing how the characters react to the events and in the big reveal of the event itself, a sort of predestined climax that is somehow more satisfying because we know it will come. We all know that Odysseus will come home to Ithica and give the boot to the suitors at the end of the book but that doesn’t stop us from enjoying his travels or the final showdown.

The Detective Story

The narrative is driven by an event that has happened. The characters are involved because they are investigating this occurrence for reasons of their own (Job/personal connection). The narrative follows the characters as they unravel the causes of the event, eventually leading them to uncover and confront whoever is behind the event. Usually this a human agency, but in a fantasy novel it could easily be an evil sword or a malignant deity. The satisfaction in most detective stories is in uncovering the causal chain, link by link, and having our guesses about the who and why of the original event confirmed or shattered as we read onward. The final confrontation is just the logical end of this process, the last link in the chain. The structure of this form of narrative is necessarily a little more rigid: you have to follow the chain of cause and effect.

These two narratives are fundamentally incompatible. A prophecy exists outside of causality. It is going to happen no matter what, it the conditions that bring it about are fulfilled. The characters could be, and often are, actively trying to avoid it, but will be pulled in regardless of their desires. Think of the parents of Oedipus leaving him to die as a child to avoid the prophecy: fate always has ways of defying logic in this kind of tale. This is opposed to the detective story, which is relentlessly logical, following the chain of clues, each an miniature cause and effect, gathering evidence and motive, all working towards causality. This chain, no matter how many dead ends or false branches are thrown into the story must still be followed to get to the desired end, the cause behind the original effect, effectively the answer to the question(s) first posed of the reader.

Prophecy does not ask questions, it just is. The detective story is based on a series of questions. The incompatibilities of these two forms could be overcome in an entertaining fashion by a master writer, but the combination would require more planning and skill than combining gritty elements and worldview with something more sunny.

Ultimately, it may be that the philosophy behind these two views is incompatible. Fate decrees that there are things man cannot know, cannot confront, or cannot change. Causality is all about knowing, confronting, and changing. Just look at leaders: those who invoke fate do nothing but mutter the tenets of their particular ideologies and hope for the best, while those who follow causality will at least try to gather data from past mistakes to avoid future errors, changing their view to suit the world around them.

Food for thought: Something that puts both Game of Thrones and Lord of the Rings head and shoulders above much of their competition is that they are both epic and causal (at least up until book 3  ). Tolkien and Martin manage this by creating detailed histories which become part of the causal chains of their epics.

). Tolkien and Martin manage this by creating detailed histories which become part of the causal chains of their epics.

March 26, 2013

Teaser Tuesday

I am done the first draft of Bloodlust: Will to Power (102522 words so far). Super happy about that!

This week’s teaser is a little intro I added to the first chapter. The tense might throw you, I’m just experimenting…

Sax doesn’t really sleep. He’s fairly certain that the others don’t realize this; he’s mastered the art of dulling his thoughts so even a master cogimancer has to check twice. Thus he is fully awake when they attack, aware of their approach long before they get there. And because of what he is, he is always prepared for an ambush. He becomes aware of subtle noises, a shift in the forest. The silence is inhuman, as if a dozen great cats stalked towards the fire in the distance. He springs into action. Shouting a warning as his blade meets the nearest form.

Gavin is fuming over a link he just read about Sadira’s supposed sexscapades in the debauched Brightsands social circles. He doesn’t believe the rumours of her promiscuity, but the taunting words and salacious pictures make him mad. His anger leads to jealously and heart-pangs. His distraction and anger work in his favour, however. He does not hesitate. He hears a noise. Sax’s warning shout follows. He turns. Sees the glint of firelight on steel. Knife coming for his throat. Reflex takes over. His hand darts out. He pulls. His opponent is surprisingly light. The body hits the fire with a crunch. More forms boil out of the darkness. They make no sound other than their rustling movements.

I added it partly to pad out a plot arc I added late in the book. It describes a random seeming ambush they encounter in their travels. Again, I’m not sure if I like the tense change.

March 24, 2013

Classic Characters: Space Marines (the value of big heroes in grim universes)

“Listen closely Brothers, for my life’s breath is all but spent. There shall come a time far from now when our chapter itself is dying, even as I am now dying. Then my children, I shall list’n for your call from whatever realms of death hold me, and come I shall no-matter what laws of life and death forbid. At the end I will be there. For the final battle. For the Wolftime.”

Leman Russ before his final departure into the Eye of Terror (GW Space Wolves)

All the talk about Grimdark got me thinking about Space Marines. The Space Marine is an interesting character archetype with a surprisingly long history, dating back to the early days of popular science fiction. Space Marines are more or less elite soldiers who operate from space, taking the fight to enemy planets or boarding ships. They tend to be incredibly skilled and powerful, the pinnacle of machismo

My first exposure to the character type is from Robert Heinlein’s Starship Trooper, a book I picked up on my first trans-Atlantic flight. Heinlein posits that democracy could fall apart without the concept of service in citizenship and creates a pseudo-fascist military meritocracy to explore this idea. This is interesting but it really pales in comparison to the power-armoured mobile infantry locked in combat with hideous arachnid “Bugs” who seek to end humanity. The Bugs are portrayed as an implacable foe of mankind, although the book carries the jingoistic terms that you see in any war narrative.

Heinlein’s Mobile infantry were tough, smart, and self-reliant. They were equipped with cool weapons and followed a truly professional, responsible command structure that would be the envy of every soldier I have ever chatted with. The fact that they were often allowed to make their own decisions in the field and did not get blamed is very much at odds with some modern wars. They were effective, even super-heroic, in the execution of their duties. In many ways they are akin to Knights (Mobile infantry) fighting Orcs (Arachnids) in a pastoral fantasy novel.

The Most Iconic form of Space Marine thus far is brought to us by Games Workshop. Warhammer 40k is a beloved franchise that evolved from a popular miniatures game and has spawned some notable books and computer games. In the fluff (the fiction that supports a miniatures game) the Space Marines are Heinlein’s Mobile infantary taken to extremes. They are recruited from savage planets and military cultures which revere macho qualities. They are selected by warrior-priests after a gruelling and often lethal series of initiation procedures and implanted with a gene-seed (yes, this is all said/read with a straight face) that gifts them with superhuman strength, endurance, long life, acute senses, and many other powers. Each space marine becomes a hero of legendary power and is then gifted with increasingly crazy weapons and power armour that again are extrapolated from Heinlein, but way more badass. It doesn’t hurt that GW threw realism out by the window and that 40k is more space fantasy than science fiction.

Space Marine promo art from one of the relic games. Space Marine, I think. Games Workshop/Relic stuff. Used without permission.

The leadership of the Space Marines is more overtly fascist than Heinlein. The Imperium of man hates aliens, mutants, and seeks to control everything. They come off as the “good guys” because everything else in the universe is monstrous and crazily hostile. Tyranids consume planets, stripping whole swathes of the galaxy of life to satiate their mad hunger. Dark Eldar kidnap and enslave everyone they encounter, torturing and murdering for kicks. Daemons prey on the psychically active, instigating rebellions and insurrections that can lead entire planets to become living nightmares. And those are just the regular badguys

Naturally to fight against this relentless tide of evil, you need a group of crazily over-the-top manly men (there are no mixed gender space marine units, amusingly enough) who are insanely devoted to their duty and their brothers in arms. In the fiction at least, the Space Marines deliver in spades cutting a gory path through all enemies and performing the acts of heroism and barbarism that keep the universe from ending. The tone reminds me a fair bit of the Iliad, a constant flow of mad heroism with the insane machinations of incomprehensible forces in the background. Space Marines usually die heroicly, the corpses of their enemies piled around them, the name of the Emperor of Mankind escaping from their lips. The fact that they live in such an awful, ugly, brutal Grimdark setting and yet stand up against overwhelmingly deadly and innumerable enemies is what makes them cool. They also come in several varieties, each with its own traditions and variations on the warrior cult. Here are a few of my favourites.

Ultramarines: I like to think that the colour Ultramarine is named after these guys and not the other way around. The Ultramarines are the most exemplary and dutiful of all the Space Marines chapters. They are “by the book” on everything, which makes sense since their founder wrote it, and are inspired by ancient warriors cults like the Spartans with a healthy dose or Rome tossed into the mix.

Space Wolves: Space Wolves are the rebellious chapter, a legion of headstrong space-vikings who recount their endless deeds over mead and go into battle accompanied by storms and cybernetically enhanced wolves. Space wolves are my favourite chapter, far more individualistic that most other space marines with a sense of brotherhood that can only be shared among crazy nordic space heroes. The only thing that could make this chapter any cooler would be some women thrown into the mix. Space Valkyries, yessir!

Dark Angels: The Dark Angels have a dread secret that they have been keeping for ten millenia. They almost sorta kinda betrayed the Emperor! Naturally this drives them to overcompensate for their dark past by being extra heroic and also waging a secret war tp kill anyone who knows about that thing they once did.

Blood Angels: Vampiric Space Marines. Nuff said.

Chaos Marines: Chaos Marines are the Marines who rebelled against the Emperor and took up with Daemons rather than follow his commands anymore. They are equally the over-the-top nemesis of the Space Marines, complete with their own crazy chapters and insane demonic equipment and weapons. About as evil as you can get, even in a Grimdark universe.

Aliens has a very different take on the Space Marines, called the Colonial Marines. Instead of being well supported the Colonial Marines seem to be a little weary and underfunded, often forced to make sub-optimal decisions because they are the enforcement arm of a weak government that exists only to serve its corporate masters. The marines are just as tough, and include tough (even Macho) women, but the bad decisions of others lead them into an untenable situation. The idea of doing job replaces that of duty. Their experience has led them to cynicism, and the reality of their command structure is a resounding rejection of the theorycrafted military awesomeness that any of the other Space Marines enjoy. It is an interesting deconstruction of Heinlein now that I think of it.

Regardless of the flavour the Space Marines face foes and odds that would make any rational being balk, or maybe hide in a corner. They spit in the face of death, even in some of the grimmest universed that ever held up under fan scrutiny, and go down fighting. They tickle the modern idea of gear fetishization with their cool weapons and armour (something I delve into with the Gladiators in Bloodlust: A Gladiator’s tale.) They have a clear sense of duty, something precarious in the complexities of our modern age. They fight for survival, for honour, for glory, and while the universe might be constantly dumping mad soul-destroying monstrosities that make Cthulu look soft on them, they fear nothing and trust in their brothers (and sisters in the better incarnations).

Heroes of that type often seemed fun, but a little immature in an over-the-top way, to me until I read a post about pro-wrestling in my internet travels. Pro-wrestling is notoriously macho with the same sense of mad heroism pitted against often overwhelming odds (cheating, fighting outnumbered, and so on) In good pro-wrestling story-lines the good-guys will always persevere against insane odds or go down fighting after treachery. One of the comments I read was from a dude whose brother was facing a terrible wasting disease. The young man was an avid a certain pro wrestler, and would often quote the wrestler’s tagline when facing yet another operation or a day full of the pain and struggle he required just to stay alive. The thought was that he admired an over-the-top hero, like the pro-wrestler, because that person embodied the same never-say-die attitude that he required just to function. It was a touching thought, and one that I have carried with me for a while, mulling it over. Perhaps we sometimes need something pure like the Space Marines or Hulk Hogan/Jon Cena to drag us out of our own Grimdark…

… But I also wonder if perhaps these heroes are our own way of paying tribute to the unbelievable courage of people who live and struggle in untenable situations, of mythologizing and internalizing the admirable qualities of those who suffer and endure, those who face long odds in the name of duty, ad those who just never give up. And maybe, just maybe that’s why those stories are so important…

March 21, 2013

Gritty, Grimdark, and Gratuitous

Logan Grimnar, Bloody-Handed Warrior

He piles the skulls of his enemies

He builds a mound of the fallen

His foes weep rivers of blood

Logan Grimnar, strong wolf of the pack

His Sword hungers for red flesh

His guns thirst for battle

He laughs amidst the war-din

Logan Grimnar, father of wolves

His sons haunt his enemies

Slay them where they falter

And bring their pelts to Fenris.

- from The Saga Of The Old Wolf (excerpt from the Space Wolves Codex for Warhammer 40k, the original Grimdark)

Earlier this week I was browsing r/fantasy when I came across further discussion of gritty fantasy. You might remember my article on the subject, which came about after I read Joe Abercrombie’s excellent post on the value of grit in fantasy. I personally figured this discussion had moved on, as much as it ever leaves us, but it is apparently still going strong. Perhaps I missed out because I was finishing off the first draft of Bloodlust: Will to Power, the sequel to that book in the sidebar.

Two excellent articles were posted, one by Sam Sykes, one by Elizabeth Bear.

Hilariously the label Grimdark has been stuck on to gritty fantasy. I partly blame TV tropes, a site dedicated to defining and listing tropes, but in a friendly fashion. Grimdark has been a gaming term for some time, often used to discuss the Warhammer 40k setting (which Sam Sykes notes, earning him my respect).

For those of who don’t know it, Warhammer 40k started off a minitaures game but has spawned several decent computer games a host of novels and many, many other hobby games. It is most recognizable for the iconic Space Marines, super-heroic defenders of humanity. The games setting is notoriously dark, crazily over top bleak. The Imperium is corrupt, uncaring, and undeniably fascist. All wars are like WWI, but with enemies inspired by Demons, Cthulu, Terminator, and Aliens thrown in. Betrayal, horrible death, and dark fate are staples of the setting. The best characters in this setting can usually hope for is to die a good death or maybe just survive. The few heroes shine out like flickering candles in a sea of night. GW and its fans pull this one off with a straight face, and it works. To outsiders the setting would appear so excessively bleak that they might think they have blundered onto a less cheerful version of a real-life doomsday cult. I love 40k.

Grimdark began as a proud fan-made label for 40k and it is a little annoying to see it applied pjoratively to gritty fantasy.

I have several other thoughts about the whole Grimdark discussion. Here they are in no paticular order.

Gritty versus Gratuitous

I have no problem with grit in fantasy. If I don’t like it I will simply not read the book. As readers develop their own personal tastes they will often be able to tell which works will suit those tastes and which will offend them. It reminds me a little of dating. When we are new to something let our tastes be determined by popularity. In high school most young men will fawn over a handful of women and vice versa. This changes as people get more experience with dating (or reading) and get to know what they want for themselves instead of just following the pack. It is a natural process and it is ever evolving for the true reader, often varying by mood. In following this process most of us will gain some appreciation for gritty fantasy and many will absolutely love it and delve right in. This is a good thing.

My only criticism of some so-called gritty books is when it gets gratuitous. I don’t like gritty when it serves no purpose. This a tough point to define, especially in the age of Quentin Tarantino where our culture has become so nuanced that types of violence can be used to perfectly convey differents moods in the same film. If the story seems to wallow in graphic descriptions of really nasty stuff without any purpose it is gratuitous. If the dark elements are pointlessly over-the-top without being entertaining, it is gratuitous. Honestly, I just think its bad writing more than anything. A good writer can make the darkest scene serve the needs of the narrative.

I also utopian fantasy can be gratuitous: too much sunshine and happiness can be just as sickening as too much grit and dirt. Best to be careful though, it is a fine line and not everyone likes the same things.

Shocking and Breaking Formula

Shocking a reader out of their comfort zone is a much tried technique. It is more hit than miss in my opinion. I’ve read Shake hands with the Devil and several eye-witness accounts of Death Camps and Death squads that have shaken me to the core. I don’t think any Fantasy novel has managed to shock me with excessive grit since then. It just doesn’t compare, nor should it.

However several gritty novels have managed to shock me by breaking formula. The most famous cases are The first books of the Song of Ice and fire series and the Thomas Covenant series. Both of these managed to shock me my twisting the conventions of standard storytelling on its head after a long build-up. The grit in this case is a by-product of the broken convention and more than acceptable, despite being rather grim.

Perhaps I just don’t like gratuitous shock…

Utopian, Pastoral, Heroic, or Escapist Fantasy… what is the opposite of Gritty Anyways?

Utopian Fantasy is a fantastical take on the idea of the perfect society. Utopian novels of any sort tend to demonstrate the biases of the writer more than anything.

Pastoral Fantasy is fantasy that longs for a pure, uncomplicated past where everything was brighter, more natural and more innocent. Fantasies of this type tend to take tribal or medieval life and present it in a very positive fashion.

Escapism is a term that used to be applied to all of Fantasy. Basically serious critics thought fantasy contributed very little to modern though and only appealed to readers who wanted to send their brain on a vacation. Hard to say that these days… Escapist Fantasy would be easy reading fantasy these days. The term has fallen out of use for a reason though, for some people gritty is escapist I’d wager.

My vote is for Pastoral. Utopian has very direct political connotations, and Escapist is too broad. I’d stay away from heroic fantasy as the opposite of gritty because as I noted in 40k the darker a setting is the more a hero can shine.

Don’t forget the middle ground!

The whole Grimdark discussion ignores a wide swath of books that exist in the middle ground, many of which are absolutely awesome. Guy Gavriel Kay and Michael J Sullivan leap to mind. Both deal with gritty, brutal subjects when the need arises but take a balanced approach, avoiding any movement towards the gratuitous or the overly pastoral.

In the end I think it is a healthy discussion. Most of the reasonable authors feel that grit is just another tool for a writer to use. Grimdark may very well become to fantasy as it is to gaming and help potential readers find the stuff that fits their personal taste.

March 19, 2013

Teaser Tuesday: From Bloodlust: Will to Power (The Format...

Teaser Tuesday: From Bloodlust: Will to Power (The Formatting sucks, I know)

“You’ll love this, I swear.”

“Does dodging a charging, angry bull really sound like my idea fun Ravius?,” said Gavin, fastening the leather straps on his silvery mithril greaves. “I’m a little less mobile than you and my shield is going to offer little comfort against that kind of impact.”

“Have I ever misled you, little brother?” said Ravius with a grin, continuing before Gavin could respond. “This type of match is a local favorite; you did say you wanted to win fame and recognition so you can rejoin Sadira… yes?”

“I’m not going to back out now, Ravius,” sighed Gavin. “I just wish you’d stop trying to convince me I’ll like your new `hobby’ as much as you do.”

“You’ve fought bigger creatures than these bulls,” said Ravius.

“True, but I’m not allowed to injure the these enemies; that makes a big difference, I’d say,” said Gavin.

“You’re always complaining about how the arena is too bloody…” said Ravius. “What better way to showcase your skills in their purest form?”

This scene leads to a rodeo match early in the book. Celtic culture is well known for their love of bulls, with some ancient stories even featuring mighty bulls fighting it out instead of men.

The Bull match lets me showcase a new form of fighting, it helps to vary the match type to keep it interesting. Over 60 arena fights in this series…

I will change a fair bit of this, even the formatting is off and the dialogue needs to be a little snappier. It is a very early part of the draft.

March 17, 2013

Odysseus: The man with the plan.

“A man who has been through bitter experiences and traveled far enjoys even his sufferings after a time”

― Homer, The Odyssey

“Do you think the enemy’s sailed away? Or do you think

any Greek gift’s free of treachery? Is that Ulysses’s reputation?

Either there are Greeks in hiding, concealed by the wood,

or it’s been built as a machine to use against our walls,

or spy on our homes, or fall on the city from above,

or it hides some other trick: Trojans, don’t trust this horse.

Whatever it is, I’m afraid of Greeks even those bearing gifts.’” Vigil, the Aeneid

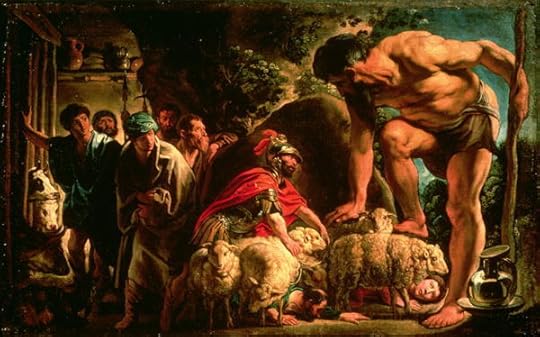

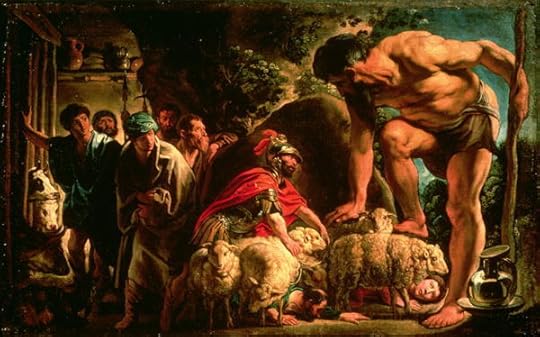

Nice art, but not really indicative of what was going on.

[Note: for those of you unfamiliar with ancient literature, Ulysses is the Roman name for the Greek Hero Odysseus.]

Odysseus is one of the greatest heroes of classical literature, and a personal favorite. The Wily King of Ithica stands out among the Greeks for his intelligence and good council. He is a secondary character in many ways in the Iliad, but he rated enough interest to get the second book in the series, the Odyssey, all to himself. Odysseus is a hero who is fated to wander. As I noted in one of my posts about Fate and Causality, you could take most of the islands he visits in the central parts of his travels and recount them on their own or even mix them up in order and the only way it would disturb the narrative is with the size of the ever shrinking crew. Odysseus is fated to wander and until he serves his time the plot is more interested in defining his character through his wandering than resolving any story.

Odysseus desperately wants to return to Ithica. The Trojan war has taken up ten years of his life. He has a son, a wife, and subjects who miss him. Sadly for him, his Trojan horse stunt has caused Poseidon to focus on him as the reason that his beloved Trojans lost (even though that was fated too). Poseidon, brother of Zeus, outranks most of the Gods, and so he calls upon her powers and his allies to drive Odysseus off course. Odysseus’ patron Goddess and her allies are able to ensure his safety and an eventual end to his exile by interceding with Zeus, but not until the Gods have toyed with the man for ten years. By this time Twenty years have passed, his wife is holding off a legion of obnoxious suitors,and his son has grown to manhood. Things are rather ripe by the time the wandering king returns.

In most cases Odysseus is depicted as the man with the plan. He overcomes obstacles not through brute strength or skill of arms, but with planning or trickery. He is certainly brave, strong, and skilled but his cunning is what sets him apart from Heroes like Ajax and Achilles. The Trojan horse is his most famous ruse. He convinces the Greeks to pull their fleet offshore and make it seem like their are leaving. Meanwhile they construct a giant hollow wooden horse and hide their elite warriors inside knowing that the Trojans would take it inside the city, which will allow them to come out at night and open the gate for the rest of the army. It is worth noting that the wooden horse is a sacrifice to Poseidon, a convincing sacrifice to give to the god of the Sea if one wishes safe passage for a large army. Thus we can add blasphemy to the reasons Poseidon takes a dislike to Odysseus. The Trojans cannot resist taking it, even when warned, partly because of fate but also because they wish to steal the God’s favour away from the Greeks. In the end the ruse works and Troy falls in a single night. It is not a pretty end at all, full of fire, bloodshed, and rape. One gets the sense that Homer feels it is right to punish Odysseus for the damage that his cunning plan wrought, although he sympathizes with the Ithican’s desire to end the war at any cost so he can return to his wife and son.

His ruthless pragmatism is a staggeringly modern trait: one that is largely absent from ancient tales of bloodthirsty killing machines like Cu Chulain or honorable, chivalrous killing machines like Roland or the Knights of the round table.

One almost feels bad for Odysseus’ enemies. The Trojans suffer, but they are fated to do so. The Cyclops Polyphemus, a foe that the entire crew could not overcome in battle, is quickly bested when Odysseus figures out how to get him drunk, blind him with a specially constructed ”spear”, and escape by clinging to the underbellies of his flock of sheep when he lets them out in the morning. The cyclops gets what he deserves to a certain extent, but in many ways he is in the right for attacking the Trojans for trespassing on his land.

The tales of Odysseus also show another very modern idea, the perils of being too inquisitive. When Odysseus defeats Circe, he is forewarned of many of the dangers that await him. Thus he knows to plug the ears of his crew so that they do not heed the music that would lead them to their doom. Interestingly Odysseus is curious to hear this sound for himself and leaves his ears uncovered, lashing himself to the mast so that he can listen, and putting himself in grave danger just to satiate his curiosity. Indeed, wanderlust seems to suit Odysseus well, despite his loyalty to his family overcoming all obstacles. (Interestingly his loyalty to Penelope does not stop him from having sex with a few nymphs and a sorceresses, but one also wonders about Penelope and the suitors, if one reads closely.)

In the end Odysseus returns home, and passes a few trials that demonstrate his identity, then he kills the suitors rather viciously before he reclaims his Kingdom and his life. This is the only time he acts where brute strength is

emphasized over guile. The tale of a returning veteran finding corruption in his homeland is also one that resonates in modern day, and I often wonder if this was the inspiration for the the return of the hobbits to the shire.

Modern renditions of Odysseus vary in quality. My favorite is Damid Gemmell’s in the Fall of Kings, a book finished by his wife after he died. Mr Gemmell paints the Ithican as a master storyteller, whose vivid tales inspire his crew and whose plans often have a dreamlike eureka quality to them. The author must have been aware of his own mortality and the ending of the tale creates a parallel between Penelope’s longing for Odysseus and the loss of the writer and his own wife. It never fails to bring a tear to my eye.

Oh Brother where art thou also deserves an honourable mention. It follows a very Odysseus like character trying to re-unite with his family after escaping from a chain gang in the depression era. The Ithican easily adapts to this modern setting while remaining easily recognizable underneath the Hollywood veneer.

Odysseus is the archetypal cunning hero. He is brilliant and ruthless. He is a trickster whose main concern is furthering his own goals, noble as they may be. His genius gets him out of trouble all the time, but the consequences of his acts are often brutal. His curiosity is also the downside of his brilliance, often leading him into further danger. A very well made character that has stood the test of time and feels fresh even alongside the cutting edge of fantasy.

Edit: see below.

“A man who has been through bitter experiences and travel...

“A man who has been through bitter experiences and traveled far enjoys even his sufferings after a time”

― Homer, The Odyssey

“Do you think the enemy’s sailed away? Or do you think

any Greek gift’s free of treachery? Is that Ulysses’s reputation?

Either there are Greeks in hiding, concealed by the wood,

or it’s been built as a machine to use against our walls,

or spy on our homes, or fall on the city from above,

or it hides some other trick: Trojans, don’t trust this horse.

Whatever it is, I’m afraid of Greeks even those bearing gifts.’” Vigil, the Aeneid

Nice art, but not really indicative of what was going on.

[Note: for those of you unfamiliar with ancient literature, Ulysses is the Roman name for the Greek Hero Odysseus.]

Odysseus is one of the greatest heroes of classical literature, and a personal favorite. The Wily King of Ithica stands out among the Greeks for his intelligence and good council. He is a secondary character in many ways in the

Iliad, but he rated enough interest to get the second book in the series, the Odyssey, all to himself. Odysseus is a hero who is fated to wander. As I noted in one of my posts about Fate and Causality, you could take most of the islands he visits in the central parts of his travels and recount them on their own or even mix them up in order and the only way it would disturb the narrative is with the size of the ever shrinking crew. Odysseus is fated to wander and until he serves his time the plot is more interested in defining his character through his wandering than resolving any story.

Odysseus desperately wants to return to Ithica. The Trojan war has taken up ten years of his life. He has a son, a wife, and subjects who miss him. Sadly for him, his Trojan horse stunt has caused Hera to focus on him as the

reason that her beloved Trojans lost (even though that was fated too). Hera outranks most of the Gods, and so she calls upon her powers and her allies to drive Odysseus off course. Athena, Odysseus’ patron Goddess is able to

ensure his safety and an eventual end to his exile by interceding with Zeus, but not until Hera has toyed with the man for ten years. By this time Twenty years have passed, his wife is holding off a legion of obnoxious suitors,

and his son has grown to manhood. Things are rather ripe by the time the wandering king returns.

In most cases Odysseus is depicted as the man with the plan. He overcomes obstacles not through brute strength or skill of arms, but with planning or trickery. He is certainly brave, strong, and skilled but his cunning is what sets him apart from Heroes like Ajax and Achilles. The Trojan horse is his most famous ruse. He convinces the Greeks to pull their fleet offshore and make it seem like their are leaving. Meanwhile they construct a giant hollow wooden horse and hide their elite warriors inside knowing that the Trojans would take it inside the city, which will allow them to come out at night and open the gate for the rest of the army. It is worth noting that the wooden horse is a sacrifice to Poseidon, a convincing sacrifice to give to the god of the Sea if one wishes safe passage for a large army. The Trojans cannot resist taking it, even when warned, partly because of fate but also because they wish to steal the God’s favour away from the Greeks. In the end the ruse works and Troy falls in a single night. It is not a pretty end at all, full of fire, bloodshed, and rape. One gets the sense that Homer feels it is right to punish Odysseus for the damage that his cunning plan wrought, although he sympathizes with the Ithican’s desire to end the war at any cost so he can return to his wife and son.

His ruthless pragmatism is a staggeringly modern trait: one that is largely absent from ancient tales of bloodthirsty killing machines like Cu Chulain or honorable, chivalrous killing machines like Roland or the Knights

of the round table.

One almost feels bad for Odysseus’ enemies. The Trojans suffer, but they are fated to do so. The Cyclops Polyphemus, a foe that the entire crew could not overcome in battle, is quickly bested when Odysseus figures out

how to get him drunk, blind him with a specially constructed ”spear”, and escape by clinging to the underbellies of his flock of sheep when he lets them out in the morning. The cyclops gets what he deserves to a certain extent, but in many ways he is in the right for attacking the Trojans for trespassing on his land.

The tales of Odysseus also show another very modern idea, the perils of being too inquisitive. When Odysseus defeats Circe, he is forewarned of many of the dangers that await him. Thus he knows to plug the ears of his crew

so that they do not heed the music that would lead them to their doom. Interestingly Odysseus is curious to hear this sound for himself and leaves his ears uncovered, lashing himself to the mast so that he can listen, and

putting himself in grave danger just to satiate his curiosity. Indeed, wanderlust seems to suit Odysseus well, despite his loyalty to his family overcoming all obstacles. (Interestingly his loyalty to Penelope does not stop

him from having sex with a few nymphs and a sorceresses, but one also wonders about Penelope and the suitors, if one reads closely.)

In the end Odysseus returns home, and passes a few trials that demonstrate his identity, then he kills the suitors rather viciously before he reclaims his Kingdom and his life. This is the only time he acts where brute strength is

emphasized over guile. The tale of a returning veteran finding corruption in his homeland is also one that resonates in modern day, and I often wonder if this was the inspiration for the the return of the hobbits to the

shire.

Modern renditions of Odysseus vary in quality. My favorite is Damid Gemmell’s in the Fall of Kings, a book finished by his wife after he died. Mr Gemmell paints the Ithican as a master storyteller, whose vivid tales inspire his

crew and whose plans often have a dreamlike eureka quality to them. The author must have been aware of his own mortality and the ending of the tale creates a parallel between Penelope’s longing for Odysseus and the loss of the writer and his own wife. It never fails to bring a tear to my eye.

Odysseus is the archetypal cunning hero. He is brilliant and ruthless. He is a trickster whose main concern is furthering his own goals, noble as they may be. His genius gets him out of trouble all the time, but the

consequences of his acts are often brutal. His curiosity is also the downside of his brilliance, often leading him into further danger. A very well made character that has stood the test of time and feels fresh even alongside the cutting edge of fantasy.

March 14, 2013

Fate and causality in fiction: Epics, Curses, God, and the good deed.

“I also will do this unto you; I will even appoint over you terror, consumption, and the burning ague, that shall consume the eyes, and cause sorrow of heart: and ye shall sow your seed in vain, for your enemies shall eat it.” Leviticus 26:16

I have been musing about fate and causality again this week. It is a fascinating topic, particularly as it relates to Fiction.

My first thought is in regard to plotting an epic novel. In many cases authors cannot relate a novel of immense scope and follow all the cause and effect than brings you to the end. Fate can be a very useful device in said cases, where the sense of logic is secondary to the panoramic scope. While fate often falls flat in the face of determined reasoning, it does serve very well to lend a consistent feel to a work of fiction whose scope is beyond the author’s ability to relate in a simple manner: in these cases fate fills in all the little holes that causality cannot be brought forth to cover. It works reasonably well, and some authors have made grand worlds in this way, often mixing a larger sense of fate with causal storylines.

The Malazan series comes to mind here. The cast of characters and the sweep of history is immense, but the hand of fate doles out each character’s ends so impassively that it lends a certain gravitas to the work. It also lends the series a mythic feel: mythology is big on fate and many of the characters, gods, and ascendants in the books of the Fallen resonate with those ancient impulses.

One of the reasons that fate is so compelling to us, is that it has been the dominant form of thought up until recently, when it was supplanted by reason in the enlightenment and even further sundered by science in the atomic age.

Fate: Disease as Punishment & the Curse

One of the more common uses of fate in fiction is the affliction of character with a disease or curse, usually as punishment from some outside agency. This has its roots in the ancient view that diseases were punishment from god/the gods/or brought on by ghosts/demons.

The idea of writing a story about a disease that afflicts people for moral reasons would be seen as rather gauche these days, and rightfully so. The idea of a curse however can still make a great fate-driven narrative. In this case all the really matters is how the character gets the curse, and that they want to get rid of it. Since the curse is a punishment from an outside entity the steps to get rid of the curse don’t have to be reasonable, they just have to satisfy the character of whoever gave the curse, and make for an interesting story.

Curses are also great as random character quirks in fate-driven worlds. Characters cursed to tell the truth for lying or families cursed with Lycanthropy, Madness, or a connection with some dangerous otherworldy power are examples that leap to mind.

Of course in real life, we did not actually start combating disease until we set aside the idea that these afflictions were punishments from the divine. This is an excellent illustration of how the fate based mindset can hinder us. After all if a disease is a just punishment from a moral authority, who are we to gainsay that? Better hope its not contagious though. The curse of the questing beast and several forms of Lycanthropy are among my favorite curses.

Fate: The System Grinds

In modern novels the System often takes the place of the divine. The system can be a state, a corporation, a society, or some other real world entity large enough that it overwhelms a normal man. A good example of this is the early industrial justice system as depicted in Dickens, Hugo, and several modern fantasy novels. A thief who steals a loaf of bread to feed his family is just as guilty as a serial burglar stealing jewelry: despite the obvious unfairness, the brutally impartial justice system punishes these dissimilar crimes with the same end. It is a very modern feeling, since nearly all of us have run into a situation at one point or another in out lives where it seems as if one of these monstrous entities has it out to get us, despite the fact that it usually just the system impartially doing what it is supposed and accidentally stepping on us in the process. Still, that parking ticket can feel like a malign act of fate, especially when you are late to work because your car gets towed and then you lose your job…

As I mentioned in a previous post, I enjoy the idea of the system as a Villain, especially when it has men like Javert doing its bidding: the perfect modern inquisitor hunting down men accused of trivial crimes all in the name of a warped Justice system.

Causality: God as the kind act

Speaking of Hugo’s Les Miserables, that book is an excellent example of a creative use of causality: the idea that god exists in the kind act that gets everything rolling.

In Les Miserables, the main character Jean Valjean, suffers after being released from prison. Despite his relatively minor crimes, committed to survive, he is treated as an outcast. The justice system cares nothing about his reasons for stealing, and neither do most of the people he meets as he tries to make his living. Most of them, like Javert, feel that once a man has shown himself to be a criminal his fate it set. Valjean struggles against this, but in the end starving a desperate he tries to steal from the one man who has a helped him, a kindly priest. When he is caught, the priest claims that he gave Valjean the stolen items and even gives him more. He tells Valjean that he must use the proceeds from selling these to make himself a better man, that they are a gift from God.

This kind act is the only active presence God has in the entire book, but it resonates throughout. Because of the priest’s kindness, Valjean grows great, using his power to help others. He pays this kindness forward when he encounters Fantine after she has been wrongfully dismissed from working in his factory , promising to care for her daughter, Cosette. When Javert tells him that “Jean Valjean” has been captured and is standing trial, he is compelled to point out that he is the real Jean Valjean, not wanting an innocent man to suffer his fate. He carries that good deed forward again and again, leading to acts of selflessness and noble courage. It is one of the most beautiful depictions of God I have ever seen, and it is purely causal, and ultimately does not rely on any outside agency. The resonance of the kind act would also work with humanity, or love.

Causality: The curse as a boon

[image error]

What used to be considered bad is now all that stands between you and tentacle based doom.

As for curses. I find it interesting that the curses of old are giving rise to modern heroes. Vampires, when viewed through the eyes of fate are horrible, doomed creatures tainted by their afflictions. But then again that is the view of any affliction or curse from a fate based viewpoint. In a more rational system the Vampires flaws can be overcome. Thirst for blood? Bloodbank or animal blood, we can deal with that craving. Burn up in the sun? don’t go outside or use an umbrella. These flaws become interesting character quirks, or vulnerabilities, while the rest of the curse such as super strength and resistance to injury become more desirable assets once the negative aspects of their curse are treated. Same thing with werewolves. In pre-modern times the idea of a werewolf or vampire protagonist would be regarded as rather odd, since these were terrible curses from god, or the results of monstrous acts of hubris.

Hellboy is an interesting example of this. He is a character who rejects his fate, and uses his devilish powers for good. There was a time when such an idea would be considered an affront to all that is good and decent, but in the age of reason, we judge people by what they do and Hellboy fights evil, so we like him. Many Fantasy authors are exploring this particular theme, taking the old monstrous races like orcs and turning them into just another member of society or a misunderstood hero.

Interestingly many of these characters have the system bearing down on them, trying to enforce control because of the old stereotypes. There is a bit of this in the Dresden files as well, where Harry is always watched by the Wardens for an act he engaged in long ago. In fact most wizards and witches in pre-modern fantasies were viewed as quite evil. You could probably write a dissertation on how old curses have become the heroes of today…

The idea of curse as a boon is indicative of another more modern idea: adaptability. That we can change to meet our circumstances and face new challenges, so long as we keep our wits about us.

Edit: Ooops I meant Fantine. Durrr.

March 13, 2013

Teaser Tuesday: Late night edition

“The fault was mine, Delph.” he said. “I didn’t finish the job last time Valaran and I met. Tell the others, give them my thanks.”

Delph nodded. He could sense the weight of Gavin’s words.The clasped hands once more and Gavin turned to Sadira, lifting his banner-spear in salute to her before they began moving forward once again.

They passed along the docks of Krass, where Gavin used to watch the tall ships come and go from his window at the orphanage before he was taken away. It seemed dirtier to him now, a little less grand, but far more lively. Sadira flirted and bantered with dockhands, sailors, and shipwrights, charming them all.

More than a few of them noted Gavin’s banner as he passed in her wake.

On the water, past the harbour forts, a mightly ironclad fired its guns in salute as Sadira paused to greet the Marines assembled in front of the Naval yards.

From there they descended into East Shallows, a crowded section of they great city, where the streets were narrow and shaded by the large tenements built therein. These tenements were a relic of the days when the great storms of the Reckoning battered Krass and space within the walls was at a premium. The city’s engineers were forced to raze the worst sections of the old city and drain unused sections of harbour, buildong tall warrens simply to house the growing population: expanding beyond the walls at that time was foolish.

The narrow streets were thick with people, the working poor who laboured in warren farms and nearby manufactories. Many of them wore red, and they cheered Sadira with wild abandon. She returned their ardour with gusto, putting on a grand display.

This is a pre-draft scene. The Characters are part of a procession of Gladiators winding through the city of Krass. I will likely expand a bit on the details of the great city, but you get the idea. The parade was written mostly for pacing purposes: to give this chapter a sense of grandeur.