Doug Wilson's Blog

November 27, 2020

Casey At the Bat: 2020 Style

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for Mudville fans that day: After five and a half hours, there was still an inning left to play. The fans realized these players weren’t the best, A third of each team was out; they had failed the Covid test. And if that wasn’t enough to ensure a stinker, Mudville’s Hall of Fame manager got another DUI--he was in the klinker. Pitchers? Thirteen men had already hurled the pill. So many changes they put a revolving door upon the hill. The score stood two to one; three solo homers had been hit. But other than those three blows, batsmen hadn’t done shit. Thirty men had taken three whiffs and retreated with egg on their face. A handful had walked and been pathetically left on base. And so when Cooney drew a nine-pitch walk and Barrow did the same, A giant prayer went up: “Please God, let someone end this game.” Some thought, “If only a miracle happened and someone could score, Why, we’d be home then by three AM, if not a little before.” An old-timer offered, “How about a bunt, steal or hit and run?” “You silly geezer,” they sneered. “You know that’s not how it’s done.” The three true outcomes, that’s where it’s at. Walk, strike out or home run, that’s all you need from an at bat. “You never risk an out on the bases. Bunt? That’s not the way And as for defense: who cares, don’t need it--the ball’s never put in play.” So when Flynn, swinging wildly, missed a third strike by a mile, And Blake, without a whimper, went down looking they could barely smile. The snooze-fest continued; silence broken only by Casey’s walkup riff. Even fans who were awake, they couldn’t clap—It was so late their hands were stiff. They yawned as he went through his at-bat routine for five minutes or more. When he finished scratching, pulling and stretching, you could even hear some fans snore. And then, when he took the first two strikes, no one gave a care. “Never swing early in the count,” he said. “Wouldn’t dare.” But now the moment of truth was finally at hand Something had to happen; fans sat up and watched all over the land. Things certainly were tense, but Casey smiled as if not a worry in his head. Because he knew a secret they didn’t, and so he was relaxed instead. Someone in the bullpen, you see, they had stolen the sign. Casey heard the clang of trash cans and thought, “This next pitch is mine.” He smiled as he thought, “I can hit this one over the wall.” “And I’m sure glad I took that Lasix, to mask the stanazol” But on the mound the pitcher only smiled; you see he had a secret as well. He applied a foreign substance; it increased his spin rate and his pitch was hard as hell. And so when Casey took a mighty swing with a massive upper cut The ball disappeared into the catcher’s mitt, Casey slipped and fell on his butt. Oh somewhere in this favored land they still play baseball that’s fun. Fans care and love it as players make contact, play defense, steal and run. Somewhere baseball stirs passion, makes men cheer and women weep. But not in Mudville anymore. You see, their fans are all asleep.

Published on November 27, 2020 05:54

April 14, 2020

A Spring Training Trip to the Ballpark, 1970 Style: Joe Pepitone and the Harmon Killebrew Home Run Ball That Wasn't

With no baseball in the foreseeable future, I have been thinking about the simple pleasures of childhood and a trip to the baseball park and what we might be missing this year. While all fans lament the cancellations, the games themselves can be replaced--there will be other games and other seasons. But a bigger loss comes for some parents and kids who are at a critical age. There is a special time in everyone's early life, a golden time to make memories; a temporary confluence of passion and wide-eyed innocence; a time of hope, when absolutely anything is possible. It is a fleeting time which, once lost, is gone forever and often is not even recognized until years later.

For the lucky, these days may be caught and will remain indelibly etched in the brain because they are so special, so memorable, so fun. The one day that remains special for me came in the spring of 1970. I've been to lots of baseball games since but none will ever compare with that one. And it had everything to do with the timing.

Baseball was not only important to me during that period, it seemed to be the most important thing I could imagine; an all-consuming passion. When not playing on my team or in pickup games or Wiffle ball games or whining my way into games with my older brother's friends, I was throwing a rubber ball against the side of the house, playing imaginary games in which I was the star of my major league team, hitting .400 while winning 30 games as a pitcher (I was nothing if not optimistic). Sometimes, I would toss the ball up, hit it and then dash around the bases of our backyard field, sliding in with triples and inside-the-parkers (always sliding--seems like the plays were invariably close) while imaginary fielders tried vainly to throw me out. The neighbors all suspected that I might be, as they used to say, a little bit touched in the head. However, nothing brought more pure joy.

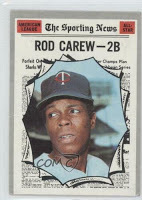

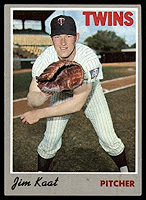

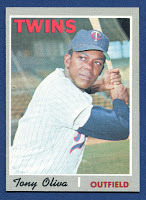

We lived on an Air Force base not far from the spring home of the Minnesota Twins, Tinker Field in Orlando. The Twins were considered our hometown team and they were great. These were the Twins of Rod Carew, Jim Kaat, Tony Oliva and Jim Perry.

But the best of the best, my hero, was slugger Harmon Killebrew. He had been named MVP for the 1969 season after hitting 49 home runs and 140 RBIs. Killebrew had the reputation as a gentle giant who was nice to everyone. I was certain, deep in my heart, that we would be great friends if we could meet.

Our family had gone to a few spring training games in previous years but, perhaps because I was younger, they didn't seem to mean as much. But this year, 1970, was different. I was practically grown up--being in third grade--and figured I had learned quite a bit about the world. I had a whole year of organized baseball under my belt and was looking forward to the new season.

So the prospect of a trip to Tinker Field in the spring of 1970 with my parents, my brother and my best friend Freddie was met with great anticipation.The game we had picked was a Saturday afternoon contest against the Houston Astros.

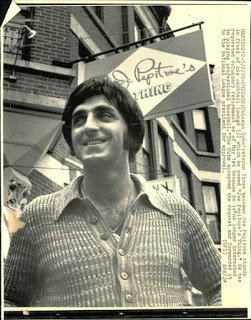

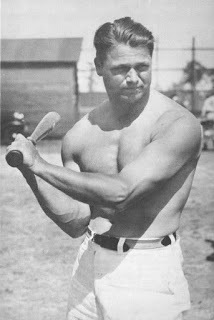

Seeing the Astros was exciting to my older brother because they had recently acquired Joe Pepitone. My brother was a budding adolescent. He still liked baseball, but for reasons neither of us quite understood his perception of the world was beginning to change--previously unimportant things like the Beatles and girls were now cluttering up his thoughts. Pepitone was the coolest guy in sports not named Joe Namath. He wore bell bottoms, wide collars with the buttons undone down to his waist and other apparel deemed mod. And then there was the hair. While most square players of the era were just starting to grow out their flattops, Pepitone was rocking a thick bushy mane scandalously over his ears. He was celebrated in the media as the first player to have a hair dryer in the clubhouse. In 1970 his on-field talent hadn't yet faded and he still had a little of the Yankee dynasty aura about him.

Freddie was one of those friends you are lucky to have once in a childhood; and only in childhood. We had everything in common: we both loved to play sports and collect sports cards. What else was there? With no knowledge of the baseball draft or the coming of agents, we had made a pact that we would both play for the Minnesota Twins when we grew up, although I secretly held out the unmistakable belief that if the Green Bay Packers asked me to play running back for them I would drop Freddie like a hot potato (I couldn't turn down my buddies Bart Starr and Donny Anderson could I?).

Freddie had a unique imagination and sense of logic. He was the first kid in the neighborhood to overcome the classic mother-vegetable conundrum. One day I knocked on his door to inform him of a game of backyard football that was about to begin. From the dining room I heard his mother's unpleasant voice, "Not until you finish all those peas!" Looking past him, I saw an enormous pile of creamed peas on his plate and quickly calculated that Freddie would not finish that imposing mess until the following June. But just as I was informing the other guys that Freddie would be a no-show for this game, I turned around and there he was, beaming a Cheshire cat grin. He slyly showed me his bluejean pocket--it was full of creamed peas. "She'll never know," he confidently boasted. However, when Freddie got dogpiled on one of the first plays, I suspected that she might find out sooner than he imagined.

When viewed through the rosy lens of 50 years, spring training games back then seem the same as everything else back then: simpler, better. The stadiums were small, quaint even, with a relaxed atmosphere and easy access to the field and players. The crowds were moderate but enthusiastic.

We parked in a grassy field behind the left-field wall, walked around to the front gate and were met by the unforgettable sights and smells of spring and baseball: sunshine, popcorn, hot dogs and cigar smoke. After purchasing our tickets, we made our way toward the field, mixing with people who were flowing excitedly in the same direction--old men, teenagers, dads with their kids--all talking with enthusiasm about the team and their expectations. To me, it was like walking through gates into the world's greatest carnival.

Then we spotted the holy grail, Xanadu and Shangri La all rolled into one: the souvenir stand. We were in a trance as we gazed upon the around-the-hornucopia of treasures we never even knew existed; scarcely believing the accessibility of such treasures to regular guys like us; scorecards, pencils bearing the team logo, t-shirts, miniature bats, caps and . . . real honest to goodness authentic, just-like-the-pros-wear plastic batting helmets. And only a buck and a quarter! We were amazed. And instantly sold. For a week in preparation we had ridden our bikes around the neighborhood collecting coke bottles to turn in for the two-cent refund and we each had a pocket full of ready cash. Me and Freddy both dumped almost our entire fortune on the helmets and then walked around the park the rest of the day feeling like the things had cost a million bucks. I'm not certain, but I seem to remember not taking mine off until I went to college. Years later I would get a lump in my throat when my son found it in the back of my old closet and wore it around all day.

I was introduced to the great people you invariably met at a ballgame in the days when a ticket set you back only a dollar or two. A guy sitting beside us had brought a seemingly endless supply of the biggest sub sandwiches I had ever seen. Two massive paws were not nearly enough to corral all the greasy contents and he continuously drooled condiments and spilled lettuce throughout the game, especially when something happened on the field. There was a loud, cigar-chomping guy sitting behind us who seemed to me to be the greatest authority on baseball I had ever heard. He knew everything and graciously dispensed this wisdom with anyone close. My mother didn't seem to appreciate the cheap cigar smoke, but to me it imprinted on my brain and to this day smells like the smell of a baseball game, even though cigars have not been allowed in a baseball park for decades. And with the guy loudly sharing his insight--on every batter, pitcher and managerial decision--I was struck with a sense of how lucky we were to sit so near an obvious expert.

The players were amazing. We were mesmerized as we watched their casual brilliance as they went about their chores--flicking magnificent throws and gracefully scooping balls out of the dirt in their perfect uniforms. There was no doubt that these were true gods descended from Olympus, yet they seemed so close, almost human. This gave us hope that it was indeed possible for mortals like us to fill their shoes one day, working at the best job in the world.

It was the first time we actually were old enough to go on safari for autographs by ourselves. Before the game we followed the big kids who had scorecards and baseball cards and tried to do what they did. These were 10- and 11-year-olds (how mature could you get?) who seemed to speak in perfect baseball language and knew all the players by sight. We could only dream of when we would be such men-about-the-world as that. One of the big kids even had a 1969 Harmon Killebrew baseball card, carefully holding it in his hands in hopes of getting it signed. Now I had several 1970 Killebrews already and had traded for a 1968--anything older was surely as rare as the Dead Sea Scrolls--but for some reason I had never been able to cop a '69. I tried to concentrate on the task at hand, all the while hating that kid and his 1969 Harmon Killebrew card.

Most of the stars were busy with their work, but that didn't matter to us. Anyone in a uniform was a prize. I'll never forget the kindness of a young Astros pitcher named Ron Cook as he patiently took time to not only sign for every kid, but to chat them up. He made a great impression on me as it had never occurred that a major league baseball player could actually speak to kids like they were real people. I had never heard of him before--he was a rookie--but he made a fan that day. I would watch for his name in the boxscores that summer, hoping for good fortune for him.

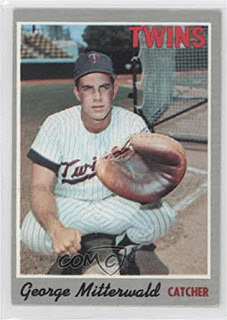

Several other players signed for us: Rick Renick, Jesus Alou, George Mitterwald, Paul Powell, Doug Radar . . . These guys would forever hold a place in my heart; the names would live on the little scraps of paper; essentially becoming the sum total of my autograph collection as the opportunity never again presented itself like that day.

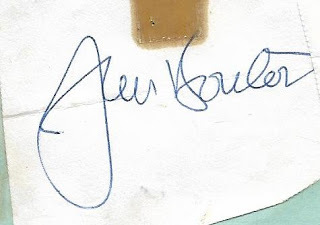

In a sweet serendipitous moment much later, I would discover the name of one other guy who signed for us kids that day. There was one name in the bunch I had never been able to discern. Fifty years later I would examine it once more and, only able to tell for certain that the last two letters of the last name were either -or or -on, survey the rosters for both teams. There was only one name that fit and comparing it to known autographs on-line, it was a perfect match. The man who had kindly given us his signature that day was unknown to us kids at the time--just another aging pitcher trying vainly to hang on. Of course in a few months every kid in the country would know his name when his diary of the preceding season was released under the title of Ball Four. It was none other than Jim Bouton.

In a sweet serendipitous moment much later, I would discover the name of one other guy who signed for us kids that day. There was one name in the bunch I had never been able to discern. Fifty years later I would examine it once more and, only able to tell for certain that the last two letters of the last name were either -or or -on, survey the rosters for both teams. There was only one name that fit and comparing it to known autographs on-line, it was a perfect match. The man who had kindly given us his signature that day was unknown to us kids at the time--just another aging pitcher trying vainly to hang on. Of course in a few months every kid in the country would know his name when his diary of the preceding season was released under the title of Ball Four. It was none other than Jim Bouton.

Of course at the time Harmon Killebrew was the great white whale for me. I was disappointed to learn that every kid in the stadium seemed to be in line trying to get to him also. He only batted once--a harmless ground out--and while we all clamored from the rail for his attention as he walked back to the dugout, he ignored us and kept walking. I heard the loud-mouth cigar chomper tell his kid that Killebrew was a bum because he wouldn't stop to sign for kids, making me think for the first time that maybe that guy didn't know everything. Even I understood that the game was in progress and the great man couldn't have been expected to stop to sign autographs. . . could he? I was pretty sure he would have stopped otherwise . . . wouldn't he?

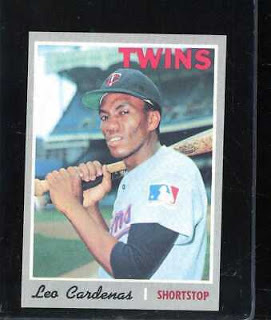

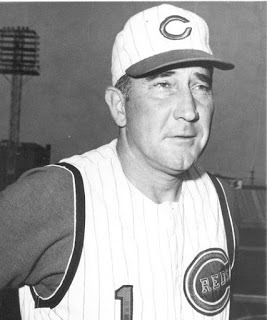

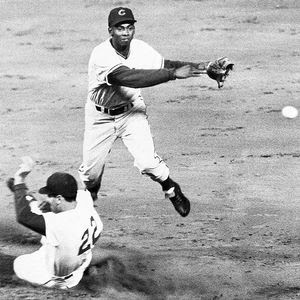

I only remember snippets of the game itself after that. I was particularly enchanted by the grace around second base of the Twins' shortstop Leo Cardenas. Since Mr. Cunningham, the coach on my farm league team, had played me almost exclusively at shortstop the previous year (and he had to know what he was doing because he carried a clipboard and wore a baseball cap) and combined with the fact that I had not yet learned of the institutional prejudice against lefthanders, I considered myself to be a future major league shortstop. I was enthralled by hearing the PA announcer drawing out his name also, "Leooo Cardennnnnnas;" a call I would repeat at the top of my lungs in the backyard as I played imaginary games against myself for the next few months.

Years later I would meet Mr. Cardenas with my son at a Reds Hall of Fame event and we would share a laugh and a memory of that day.

Years later I would meet Mr. Cardenas with my son at a Reds Hall of Fame event and we would share a laugh and a memory of that day.

The Twins rookie catcher George Mitterwald not only signed for me before the game (I didn't even realize it until I got home and deciphered some of the scribbles) but hit a monstrous home run over the left field wall--scaring my mother because it seemed to be aimed directly at the windshield of my dad's prized Oldsmobile (luckily we discovered after the game that it missed). I never imagined a ball could be hit so far; obviously we were watching a future Hall of Famer.

The home run impressed me so much that I distinctly remember having an argument in the school cafeteria the next week with a know-it-all named Callahan that Mitterwald was definitely better than Callahan's favorite catcher, a second-year man for the Reds named Bench (okay, in retrospect I'll admit I was perhaps a bit hasty and maybe just a little bit wrong--if you read this, sorry Callahan).

I have a vague memory of Twins' reliever Ron Perranoski coming in and blowing the game in the 9th and the loud-mouthed, cigar-chomping guy behind us explaining to one and all that the Twins would never be any good as long as that bum pitched for them (editor's note: the Twins would win the Western Division that year and Perranoski would lead the league in saves and have a 2.49 ERA, teaching me that sometimes you shouldn't believe everything the guy behind you in the stands says, no matter how certain he sounds--and now that I think of it, I'm pretty sure the cigars stunk too).

After the game we were allowed to wander about the place in search of more autographs, harassing the poor players who at that point just wanted to get out of the Florida heat (I remember Cesar Tovar hurriedly walking past us as we were separated from the players' trek to the clubhouse by a chainlink fence and thinking that I had never seen so much sweat dripping off a person in my life).

This is when my brother seized destiny with one hand while holding a pen in the other. While we waited outside the Twins clubhouse, he staked out the path from the Astro's clubhouse to their bus. He was not alone, however, as a hoard of other adolescents had the same idea: they were all waiting on Joe Cool. The mob allowed the other Astros to pass in peace but turned to a frenzy when they finally witnessed Pepitone stick his head out, check out the crowd, then bolt for the safety of the bus. He scribbled a quick scrawl on a few pieces of paper as he kept a quick pace wading through the kids, knowing that the only way to survive was to keep moving. Now I can't honestly say that I witnessed this, but family legend--passed down verbally many times since--holds that my brother actually followed Joe onto the bus, possibly grasping his shirt, disappeared, then reappeared at the door moments later waving his prize: a Joe Pepitone autograph.

But Freddy had even better luck than my brother. While we were waiting outside the Twins clubhouse, a ball boy stepped out with a bag of scuffed-up batting practiced balls and tossed them to the crowd. And one landed right in Freddy's eager hands.

The drive home was one of fatigue, sunburn and bliss. Me and Freddy wearing our Twins batting helmets; Freddy tossing his ball from hand to hand in the back seat all the way home; my brother rehashing his adventure with new-found buddy Joe Pepitone. There was now little doubt in my mind that baseball would be my life's work and I couldn't wait until I could be wearing the uniform with that beautiful TC on the cap, limbering up in the spring sunshine of Tinker Field and signing autographs for kids (I only hoped that Leo Cardenas would have moved on by the time I was ready as he looked to be a hard man to beat out for the shortstop job).

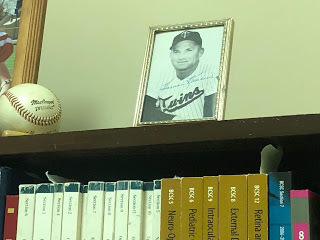

While I didn't get Harmon Killebrew's autograph that day, not long afterwards I wrote him a letter in my best penmanship and he rewarded me with an autographed picture that I still have sitting behind my desk in my office.

The next day while talking to my father, Freddy's dad mentioned how lucky Freddy had been to not only get a home run ball hit by Harmon Killebrew, but to snag the thing barehanded. As I mentioned, when Freddy went, he went big. My dad charitably kept quiet, allowing Freddy's story to go unchallenged.

All in all it was a glorious day. With time, the baseball cards would collect wrinkles and eventually be relegated to the back of our closet, the little pieces of paper with the scribbled names would be stored in a seldom-viewed scrapbook along with other childhood achievements, the photos taken on slides would fade; but the memories of the day would remain bright forever.

We swore we'd do it again, but we never did. Freddie's father was soon transferred and they moved away. A few years later Harmon Killebrew began to grew old and retired. I didn't quite make it to play shortstop for the Minnesota Twins. And Tinker Field was eventually torn down. Baseball would remain important, but somehow it never again seemed as important as it did that summer. Such are the friendships and dreams of eight-year-old kids.

Published on April 14, 2020 13:42

December 8, 2019

Dave Parker: Battling Parkinson's Disease One Day, and One Event at a Time

It's the change that strikes you first; such a drastic change from the man you remember from his playing days.

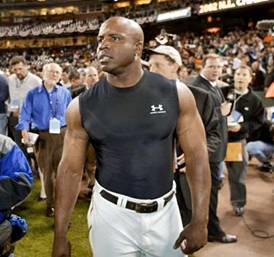

The face that used to light up clubhouses is less animated, more measured now. The arm that used to terrify opposing runners now sometimes needs special focus to move correctly and stop trembling. The booming voice, full of jive and hubris, that used to command attention is now soft and slow. The gate that made one of the most distinctive home run trots in baseball is less of a saunter and more of a cane-aided shuffle. These changes are all characteristic of the Parkinson's Disease that Dave Parker has battled for 7 years.

But don't feel sorry for Dave Parker. He won't allow it. "We're going to beat this thing," he says with assurance. And those familiar with Dave Parker back in the day know that if there's one thing he could always do, it was speak with assurance; and then back it up.

The 69-year-old Parker lives in Cincinnati, where he grew up and became one of the greatest athletes the city ever produced. A product of Cincinnati's famous Knothole youth baseball program, he spent a lot of time at Crosley Field in the summers. He opened cab doors for tips and chased down balls hit out of the park to sell, anything for a buck. As a teenager, he worked inside selling popcorn, peanuts and ice cream while watching his favorites Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson ply their trade. He admired Frank and Vada as they pulled up to the parking lot in their white T-Birds--with red interiors and round porthole windows--the sharpest cars a baseball player could own back then. Once Frank gave him a glove: "Hey kid . . .," just like Mean Joe Greene in the famous commercial.

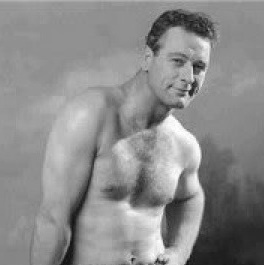

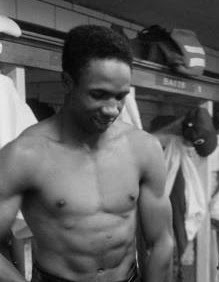

By the time Parker was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1970, he was a dominating force on the baseball field. At 6-foot-5 and well over 200 pounds, he was an uncommon combination of speed and power. Tools? He had all five in spades. He also had a brash confidence that came from never remembering any time when he wasn't the most talented, imposing physical specimen on the field in any sport he tried.

Once in the majors, Parker quickly established himself on the shortlist of the best players in the game. By the age of 28 he had hit over .300 five straight seasons and owned two batting championships, three Gold Gloves, an MVP award, an All-Star Game MVP award and a World Championship ring. He also temporarily held the title of the highest paid player in the game. He was the first major leaguer to sign a contract that averaged more than one million dollars a year.

And he was more than just a great player. He had style. The clothes, the bling, the funky music from the boombox--it was pure '70s. He was part Superman, part Superfly.

Dave Parker never held back--on the field or in the clubhouse. He played hard, hustling constantly. He never dogged it on a popup and he never tipped-toed around home plate on a close play. He dominated every room with his explosive smile and constant loud verbal assault of anyone near. Teammates loved him. He made them laugh. He made them play better.

After injuries and off-field problems soured his stay in Pittsburgh, he experienced rebirth when he signed with his hometown Reds in 1984. It was the biggest free agent contract the team had ever offered and he proved to be worth every penny. He averaged 108 RBIs over the next four seasons, including a narrow miss for his second MVP in 1985 when he hit 34 home runs, 125 RBIs and batted .312. More than great play, he brought an intangible to the clubhouse, proving to be a priceless mentor to talented young players like Eric Davis and Barry Larkin.

Baseball historian and stat guru Bill James, in a book written just after Parker's career ended, predicted that he would be selected by the Baseball Writers for the National Hall of Fame in 2003. He never came close but he's back on the ballot by the veteran's committee this year. Ask him about his prospects for the Hall and he would rather talk about his idol Vada Pinson. "I loved watching him play. He could do everything. And he did it all so smooth, so effortless. He deserves to be in the Hall of Fame."

That term "effortless" would take on new meaning for Parker, in ways he may have never realized. He enjoyed a good life after baseball, living comfortably on the profits from his numerous Popeye's Chicken franchises in the Cincinnati area, but his life changed dramatically one day in 2012 when he noticed that his hand had developed an annoying, uncontrollable tremor. A doctor told him it looked like he had "a touch" of Parkinson's and referred him to a specialist who confirmed the diagnosis. Only it was more than a touch. You don't get just a touch. It can take over your life. Armed with this new information, Parker went home and read about the disease.

Parkinson's is not a new condition. It's been known at least since the ancient Egyptians. Dr. Parkinson was the first to formally describe it in an 1817 paper, calling it "The Shaking Palsy." But the fact that it's been known for a long time doesn't mean that we know how to treat it. We don't.

Parkinson's is an equal-opportunity disease that affects the rich as often as the poor, with no known cause. It's an insidious condition that affects the part of the brain that tells the muscles what to do. It causes slowness of movement, stiffness and a loss of facial expression. Patients lose the ability to perform previously automatic actions, such as blinking or swinging the arms casually while walking. Speech can become slurred. Posture and balance are affected--steps slow and stride shortens-- eventually it leads to a stooped shuffle. The characteristic starting point, as it was with Dave Parker, is often a tremor in the hands, similar to continually rolling something sticky between the thumb and first two fingers. The tremor occurs at rest and increases with stress such as recognition in public. Handwriting gets smaller and cramped. The condition is gradually progressive. In the old days, patients often ended up bedridden.

It can be a very frustrating condition, for the patient and loved ones. Fortunately, Dave Parker had some help. He had married Kellye in 1983 and thirty-six years later, she rarely leaves his side.

Dave Parker went on to develop most of the classic symptoms. He found himself becoming depressed, but a man doesn't make it to the top of a professional sport by giving up easily. One day he made an oath to the reflection in a mirror that he would not give up. He decided to get involved rather than suffer and silently withdraw. He went public. "As long as I've got the disease, I might as well do something to help raise money for it," he reasoned. He already had a foundation that raised money for scholarships for needy inner-city youths. With the help of his wife, and later some friends, he expanded it and took up the cause. The DaveParker39Foundation, based in Cincinnati, assists in Parkinson's awareness and research.

Parker speaks at Parkinson's conferences and chairs events. He raises money for the cause. He talks to groups, large and small, of those afflicted. He gives them hope and encouragement. "Stay active, stay positive," he tells them. "Don't let the disease beat you."

Parker expresses no bitterness for his own condition, reminding others that there are lots of other people who are worse than he is. He tells everyone you must play the hand you are dealt. "Do as much good as you can while you're here," he tells reporters who ask why he spends so much time and effort helping strangers who share the disease.

It's not an easy disease to live with but the former competitiveness as an athlete serves Parker well. He stays active. He fought it with diet and exercise for two years before beginning medications. Now he maintains a vigorous workout regimen of exercise and stretching and medications, all of which are helped by Kellye. "She's my rock," he tells anyone who listens. "I don't think I can make it without her." They take it day to day. There are good days and bad ones.

There is still no cure for Parkinson's. Several medications help with the symptoms but also can bring new problems; doses need to be tightly controlled to avoid unwanted side-effects such as abnormal movements. Some patients are helped by newer brain surgery procedures, but at this time more important than any medical advice, medication or treatment, is the support of a patient partner and a good attitude. This is why awareness and support are so important for patients and their families.

Parker appreciates the outpouring of support he has received from the public and also from the former players who have readily stepped up to help with his foundation events, such as the Cobra Classic golf outing which takes place in Cincinnati each fall. He sits in the tent at the golf course and talks to everyone who comes by, famous and not-so-famous. He thanks them all with genuine sincerity. Large athletic men in their 40s, 50s and 60s make their way over to Dave and swallow him in enormous hugs. They exchange smiles and insults, then invariably turn serious: "You doing okay man?" He doesn't want their sympathy. "I'm all right. Don't worry about me. I'm taking care of it. We're going to beat this thing," he says again.

But Dave Parker knows as well as anyone that no one really beats Parkinson's. It's a patient disease. It always wins in the end. But maybe what Dave means is that you never really lose if you refuse to be defeated. Keep active, stay social, hope. That's the plan. Keeping fighting. And maybe, just maybe . . .

Published on December 08, 2019 10:34

November 10, 2019

Veteran's Day Salute: When Baseball Went to Combat

This time of the year, when there is no more real baseball, it often helps pass the time before spring to look back at some memorable baseball-related movies or television shows. And since it's Veteran's Day, I picked one with a military theme as well.

As kids in the sixties, each week we looked forward to watching the World War II television drama Combat. The show focused on a small squad of GIs fighting their way across Europe some time after D-Day. Led by tough-guy-with-a-heart-of-gold Sargent Saunders, played by Vic Morrow (who later gained baseball immortality with his chillingly realistic portrayal of the sinister Little League coach in The Bad New Bears) the men weren't classic heroes--they complained and whined about their lot in life and often even fought among themselves, but they also faithfully did their job and looked after each other while trying to stay alive. True to the times, the show often worked in easily recognizable lessons about duty, honor, courage and redemption.

And one of my favorite episodes had a baseball component:

While enjoying a few days of much needed rest off the lines, the squad is excited when they find out one of the new replacements soon to join them is none other than Del Packer, the best pitcher in baseball, known widely as the man with the million dollar arm. Billy, the youngest member of the squad and a huge baseball fan, clues the rest of the guys into Del's accomplishments: a career ERA of 2.04, five twenty-win seasons in the last six years and the major league leader in strike outs and shutouts in '38, '39, '40 and '41. Saunders, normally tight-lipped about his previous civilian life, even admits that he saw Packer throw his first no-hitter. The men are amazed to learn that Del gave up his forty thousand clams a year gig in the majors to make a lousy fifty bucks a month carrying a rifle to help the war effort.

Saunders warns the men not to treat him special, but to let him learn to take care of himself, stating, "We'll be in combat in a few days . . . I just want to keep him alive."

When Del arrives (portrayed by sixties teen-idol Tab Hunter), he seems like a regular guy who doesn't want any extra attention because of his celebrity and he quickly fits in. He pitches to the boys in a pickup baseball game, blowing the ball by most of them but, realizing what a big deal it would be to Billy to say he once got a hit off the famous Del Packer, he lets up and allows Billy to smack one to the outfield. "Gee, I must be losing my touch," he tells the widely grinning Billy. [While Del is pitching, the astute baseball watcher recognizes that he is right handed and files that info away for later].

When their field is buzzed by German bombers, Del dives awkwardly for cover and rubs his right arm when he comes up. It soon becomes apparent he is worried about the old flipper, especially when he hears the medical report on a soldier who was hit during the bombing: "He's gonna be okay--got it in the arm." [Cue the dramatic music].

The squad soon returns to the line and in their first skirmish, Del and Saunders spot some Germans flanking the men, headed for Billy's position.

Saunders orders Del to cut them off but after being shot at, Del, rubbing his right arm, freezes.

Del's hesitation leads to Billy getting shot and wounded before Saunders and the rest of the guys can save him. Del feels terrible and that night admits to Saunders that he froze, worried that he might permanently damage his pitching arm in combat.

He details the years of toil in the minors and how much he has to lose in an effort to get Saunders to understand. He apologizes repeatedly but Saunders, who can relay more in a single nod, sneer or smirk than most guys can with a long speech, refuses to commit one way or the other and merely grunts and turns away.

He details the years of toil in the minors and how much he has to lose in an effort to get Saunders to understand. He apologizes repeatedly but Saunders, who can relay more in a single nod, sneer or smirk than most guys can with a long speech, refuses to commit one way or the other and merely grunts and turns away.Del goes to see Billy in the aid station and Billy, apparently unaware of Del's combat-failure, thanks him for visiting him and asks for an autographed ball to send to his younger brother to prove that Del Packer was a war buddy. "Thanks. You're a pal. A real pal," Billy says with stars in his eyes when he agrees.

The next day, Del receives word that a general has sent a request for him to be transferred back to London for a cushy public relations job. The lieutenant bluntly relays that the decision is up to Del, but that they are going to need every man in the field they can get in the coming weeks. Del quickly picks London and later explains to Saunders that he that although he feels guilty about leaving the guys on the line, he's not a coward. It's just too good of a deal to pass up.

"What would you do?" he asks.

"Nobody asked me," Saunders snarls. "This is your own private war. Nobody can fight that but you . . . you're a lucky guy." While refusing to call him out any further, once again Saunders' face leaves the viewer with little confusion over how he really feels.

That night, Del drops by the aid tent to give Billy his autographed ball. When he walks in, however, he is stunned to find that where Billy lay recovering the day before, there is now only an empty bed and more dramatic music.

The next day as the squad is preparing to go out on a dangerous mission, Del suddenly shows up with his rifle and field pack; ready for duty with no explanation necessary, only an exchange of knowing glances with Saunders.

The men are soon in a tight fix as they are pinned down by a German machine gun nest that commands the entire open field. Saunders is hit and out of the action as he lays in clear view of the machine gun [don't worry, regular viewers understood that he got hit at least every other show--he must have come home with a suitcase full of Purple Hearts--but was always injured only enough to give him a heroic limp at the end of the episode and it always healed in time for next week's show].

The men are huddled behind the only cover--a crumbled block wall that appears to be at least a couple hundred feet from the machine gun. As they look for an answer one of them reaches for his hand grenade but his buddy tells him the obvious, "You'll never reach 'em."

In that moment, as the words are still hanging in the air, the thought is plain to everyone: if only there was someone who had a great arm--an arm strong enough to get a grenade all the way to the machine gun nest from the wall--then they'd be saved.

At the same time, the astute baseball fan realizes that the fragile wall that is giving them cover would only allow a right-hander to throw a grenade--a lefty would leave himself too exposed to enemy fire. But where to find a right-hander with a great arm on a battlefield??

Wait a minute! What if . . .

Just then Del hurls himself through a hail of machine gun fire and arrives at the wall. He pops the pin on his grenade and--without so much as stretching or tossing a few warm-ups in the bullpen--fires a perfect strike, silencing the gun.

All that remains is for one of the happy soldiers to turn to another and shout, "Is that an arm or is that an arm?" and for Saunders to pull himself upright and ask Del for a hand, giving Del one of those rare, hard-earned Saunders' approving-grins as the marching music begins and the boys head for home.

As they say, they don't make them like that anymore.

Published on November 10, 2019 16:10

October 6, 2019

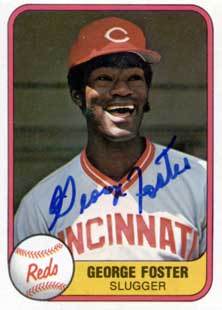

George Foster: When Hitting 50 home runs in a Season Was Hard

"It's supposed to be hard. If it wasn't hard everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great." ---Jimmy Dugan, A League of Their Own.

"It's supposed to be hard. If it wasn't hard everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great." ---Jimmy Dugan, A League of Their Own.I had a lucky meeting with former Reds great George Foster last week. And by lucky I mean that he turned just before he ran over me with a golf cart. I was attending a charity golf tournament in Cincinnati when George Foster careened up laughing and joking with everyone in attendance.

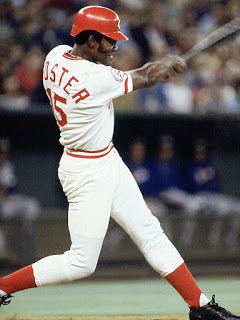

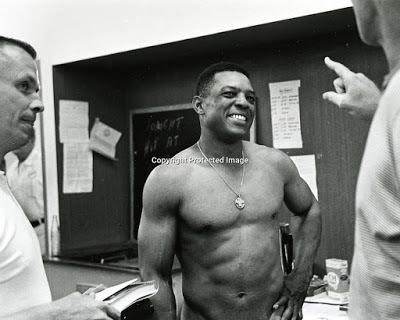

As a guy who either watched or listened to at least part of almost every game the Big Red Machine played in the mid-70s, I was thrilled to find myself suddenly standing less than ten feet away from the National League's MVP in 1977 (especially since he wasn't even on the list of expected celebrities attending--he lives in the area and enjoys meeting and greeting fans and good causes). Few things have ever been as awe-inspiring as the sight of the rail-thin Foster launching a laser beam into the red seats of the upper deck at Riverfront Stadium with his black bat and he still looks remarkably fit for a 70-year old; I wouldn't be surprised if he could still do it. Foster's 1977 season was great by any measure: he hit 52 home runs, 149 RBIs and batted .320. But it was even more impressive when viewed with the standards of the era in which it came and the numbers of his contemporaries.

Had I had time to prepare, I'm sure I could have come up with a journalistic gem such as:

Had I had time to prepare, I'm sure I could have come up with a journalistic gem such as:Me: Do you remember when you were with the Reds and you hit 52 home runs in 1977?

George: Yes

Me: That was awesome.

Unfortunately, I was caught unprepared and I turned into a 10-year old (not that that's a bad thing). I told him he was one of my favorites as a kid and politely asked if we could take a picture. Perhaps he had heard about my ineptness with selfies; he laughed and said, "Let's take a good one," and grabbed my phone, handed it to someone walking by and posed.

At the time, the Reds Eugenio Suarez had 49 home runs with several games left to play, seriously threatening Foster's team record for home runs set in 1977. I have nothing against Suarez, I think he has given the Reds two great seasons after signing a big contract, which is always nice, but George was a hero from my childhood, so no one can compare. "I hope your record is still standing next week," I told him.

Foster got a somewhat pained expression. He is a nice guy and I'm sure he tries to say the right things and doesn't want to be bitter, but he seemed very sincere when he said, "You know, when I hit 50, it was a bigger deal. No one had done it for 12 years. Now they're doing it all the time. It's not the same."

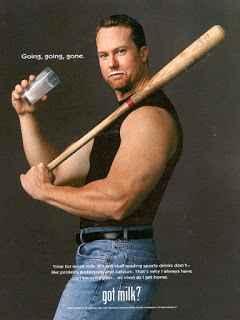

Of course George is right and you have to feel a little bit of sympathy for these former players who labored so hard, achieved something extraordinary and now are watching seemingly everyone fly right by. When George played, hitting 50 home runs was a huge deal, now it's something that is done every other year by a rookie. Fact: from the beginning of recorded time on Earth until 1977, a grand total of 9 men had hit 50 or more home runs in a Major League season (a feat performed 16 times in total, with Babe Ruth--who else?--doing it a record four times). The names on the 50-homer list read like a roll-call of the giants of the Jurassic age: Ruth, Foxx, Greenburg, Mays, Mantle. There was never a doubt that each of these guys was truly worthy of ascending the Mount Olympus of our adulation and admiration. No mere mortal was present on the entire list. And in the period of 25 years, from Willie in 1965 to 1990, George Foster was the only man to do it.

But from 1990 until now--in 29 years--the 50 home run mark has been achieved 29 times (that works out to nearly once a year for those of you without a calculator handy) by 20 different players and, what's worse, I regard at least three of those guys as definitely mortal.

When George Foster settled into the batter's box on opening day in 1977, the magic number had not been reached for a dozen years. The preceding season of 1976 saw only 2235 home runs hit in the majors, a very quaint total compared to the 6776 hit this year. The major league leader in home runs in 1976 had been Mike Schmidt with 38, a number often approached at the All-Star break now. Only three others topped 30: Dave Kingman, Graig Nettles and Rick Monday. That's it. Apparently teams scored runs in those days by running the bases and stuff like that.

The year of 1977 saw a serious uptick in homers; it was a classic hitter's year, as are all expansion years (the Mariners and Blue Jays joined the ranks that year). Home runs jumped more than a thousand--to 3644. But while a lot of hitters joined the party, not everyone put up previously absurd numbers. After Foster's 52, Jeff Burroughs of the Braves was the only guy with 40; he hit 41. While 17 other guys hit more than 30, a significant increase, it was still a rare thing. Most teams could only afford one or two big thumpers--it was big news that season when Garvey (33), Reggie Smith (32), Baker (30) and Cey (30) gave the N. L. Champion Dodgers four guys with 30.

Now compare to this season. As stated above, major leaguers hammered pitchers for 6776 taters this year. Pete Alonzo got 53 in his first look at Major League pitching and nine other guys had more than 40. And a whopping 48 had between 30 and 39, giving 58 players with 30 or more.

Does all this mean that it is easy to hit a major league home run now? Absolutely not. To quote Ron Washington in Moneyball, "It's incredibly hard." Anyone who thinks differently should grab some wood and stand 60 feet away from a guy throwing 95 miles an hour (while also unpredictably mixing in some of that ungodly breaking stuff that Crash Davis warned us about) and take their hacks.

I don't pretend to be smart enough to say if the increase is due to a rabbit ball, short fences, weight training, emphasis on launch angle over contact or any other reason. Or if it is good or bad for the game and its fans. I'll let guys like Justin Verlander and the Commish argue that. What we can say for certain, though, is that more males who currently ply their trade in the United States (and Canada) are capable of hitting home runs in bunches. Also the talent gap between the very best and the middle of the pack of major leaguers has become much more narrow.

And one other thing is true: it's not George Foster's 50 home runs any more.

Published on October 06, 2019 06:37

September 23, 2019

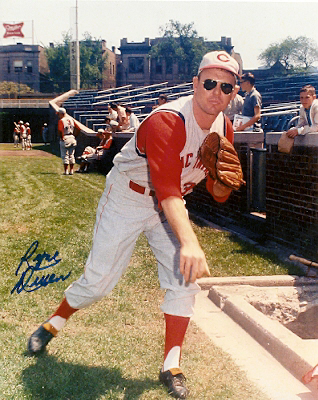

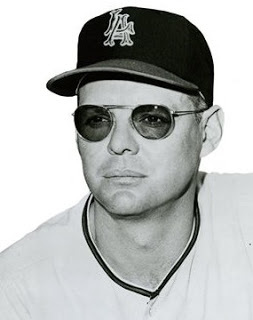

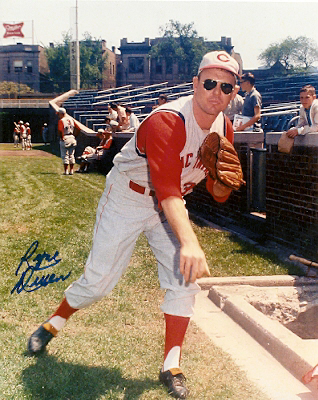

Ryne Duren and the Art of Getting Hit By a Pitch

This past weekend marks the 55th anniversary of the start of one of the Cincinnati Reds most glorious chapters--a late-season win streak that almost carried the team to a pennant. The year was 1964 and the streak was started by an unlikely hero at the plate--a famously myopic relief pitcher with a career batting average that would make a resident of the Mendoza Line look like Ted Williams.

The Reds began the game September 20, 1964 as a team that looked like it was just playing out the schedule on a disappointing season. The talented bunch had underperformed all season, as their stars slumped while sadly watching their beloved manager Fred Hutchinson wither away from the cancer that would take his life soon after the season. The Reds trailed the Phillies by six and a half games with 13 left to play as they took the field against the surging Cardinals.

Ryne Duren, a zany relief pitcher with a fabled fearsome fastball and even more fearsome lack of vision, had been picked up by the Reds early in the season. With the Reds in the middle of an uninspired game against the Cardinals, trailing 6-0 by the fourth inning, Duren had come on in relief of a battered Cincinnati starter and, since the game appeared hopeless, he was left in to bat.

When I spoke to the then-80-year old in 2009, Duren said he took exception to the fact that there seemed to be little life, or little hope, on the Reds bench. "I looked around the dugout and everyone was really down; just sitting on their dead asses like it's over," he said. "I got mad and said to everyone on the bench, 'Why don't we just go in the damn clubhouse and take off our damn uniforms and concede the damn game. If you don't want to compete, let's just go home. But if you're out here, let's have a little life.' I balled everyone out for being deadasses on the bench. So they hollered back at me, 'Well why don't you go up there and do something. You think you're so damn good, go up and get a hit.'

But going up there and getting a hit was not an easy matter for Duren, who carried a career batting average of .061 at the time and had been to the plate only three times all year. Duren could hardly be blamed for his lack of hitting prowess; he came by his futility naturally. Duren had some of the worst eyes ever to appear on a baseball field. If modern stats had been in place, he would have been credited as having the lowest VAR (Vision Above Replacement) in the majors.

He wore Coke-bottle thick glasses, usually darkly tinted and stories of his vision-challenged ways are many. Reds catcher John Edwards swears that Duren couldn't even see the signs from sixty feet away: "I finally just told him to call the pitch by moving his glove and I just got ready for anything," he told me.

When Duren pitched for the Yankees, Yogi Berra used to tell opposing batters, "I wouldn't dig in. Neither one of us knows where this pitch will go." And he wasn't joking.

So getting a hit didn't seem to be an option for Duren at this particular moment. "I made up my mind I would take one for the team, which I did," he said.

As the pitch was on it's way to the plate, Duren stepped in front and the ball hit him on the thigh. Those on the Reds bench were amazed, both that he did it, and that he got away with it.

"I'll never forget that crazy damn Ryne Duren with those thick glasses taking one off the knee just to get on base," said Sammy Ellis. "He didn't even try to get out of the way. And there's no way he would have gotten a hit. He couldn't even see."

"Duren walked right into the pitch," said batboy Mike Holzinger. "The Cardinal bench was going crazy but the umpire ignored them."

The whole atmosphere suddenly changed on the Reds bench. Inspired by Duren's actions, his teammates got to their feet; the dugout was filled with shouts and cheers and the Reds began hitting. They ended up with a 9-6 victory.

The game seemed to snap the Reds out of a slumber. The next day came the famous game against the Phillies in which Chico Ruiz stole home on his own with two outs in the sixth inning of a scoreless game. The Reds won nine in a row and cruised into the final weekend in a dead heat with the Cardinals and Phillies.

"Frank Robinson always gave me credit for waking the club up," Duren said proudly. "Coming from him that was a lot because, as you know, he was a bear-down son of a bitch."

Looking back, it's interesting that in Duren's telling of the game, the crucial at bat came against Bob Gibson. I guess old fish stories and old baseball stories are alike--the fish always get bigger with time. The box score lists the pitcher as Gordie Richardson. Just as well for Duren. With Gibson's reputation, he probably would have picked the ball up and hit him with it again--and this time he would have made sure it hurt.

Published on September 23, 2019 05:10

August 5, 2019

Fred Hutchinson: The Man and the Hospital

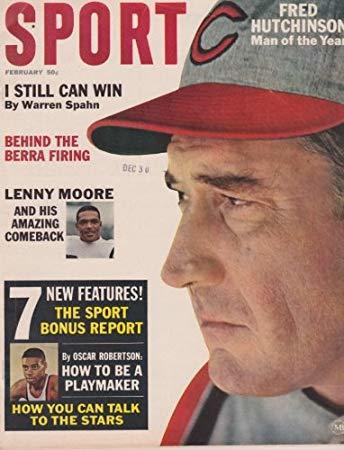

Most Cincinnati Reds fans know Fred Hutchinson as the man who led the team to the 1961 pennant and then passed away just three years later; the first man to have his number retired by the team--the number one on the façade. Many doctors know the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (above in red/orange) in Seattle as one of the world's best cancer centers. Most do not know the whole story behind both.

It's a tale of courage in the face of overwhelming odds, the bond between two brothers--one who had dedicated his life to the defeat of a disease destined to take his brother's life--and the unique legacy of hope and research that lives to this day.

Fred Hutchinson was raised in Seattle, the son of a prominent doctor. Fred's older brother Bill was a good enough baseball player to hit over .400 at the University of Washington and receive an offer from the Pittsburgh Pirates, but he felt another calling.

Accepted to medical school at the same time the offer from the big leagues came and informed by the school that he could not do both Bill, like the Field of Dream's Moonlight Graham, stepped over the baseline forever and took up his doctor's bag.

Fred became the biggest sports sensation the city of Seattle had ever seen. In a time when local school boy heroes were worshipped, Fred won 60 games and lost only 2 while leading his school to the city championship three straight years. He then signed with the hometown Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League for the 1938 season and went 25-7, winning the PCL Most Valuable Player Award and being named Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News. Fred's performance inspired such hometown sentiment that in 1999, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer named him Seattle Athlete of the 20th century. And when a new Seattle Mariners baseball park was built, Safeco Field, Fred's likeness was placed on the end of every row of seats.

Fred was then sent to the Detroit Tigers for $50,000 and four players. It was called the biggest minor league deal in a decade (just two years earlier the Yankees had acquired a pretty good centerfielder named Joe DiMaggio for $25,000 and five players).

Unfortunately for Fred's big league dreams, World War II and arm problems rendered him a junk ball pitcher who survived a decade in the majors due to savvy and an intense competitive nature.

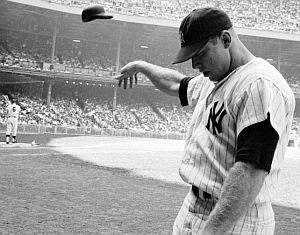

Competitive? The man absolutely hated to lose. He couldn't bear the tortured feelings of defeat. He left a string of battered clubhouses and broken runway lights around the league. Yogi Berra perhaps said it best: "When we follow the Tigers into a town, I can always tell how Hutch did. If the clubhouse is in good condition, he won. If all we find is kindling, I know he lost." One time (in a story I verified with his then 90+ year old wife) he lost a game and stormed out of Detroit's Briggs Stadium, walking the seven miles home in despair. In his anger, he forgot that he had driven to the game and his car was still in the parking lot. He also forgot that his wife had driven with him and she was still in the same lot, waiting for him.

Despite his temper, Hutch was popular with both fans and teammates. They understood that he was never mad at other players, only himself and they came to appreciate that he wore his emotions on his sleeves--there was never any attempt at deceit from the man who came to be known as Honest Hutch. He looked people right in the eye and told them what he thought.

After his playing days were over, Fred managed mediocre Tiger and Cardinals teams before arriving in Cincinnati midway through the 1959 season, brought in by Powell Crosley to rescue a talented but underperforming team.

"Hutch was just what we needed," said pitcher Jim O'Toole. "We had talent, but were rudderless. Hutch gave us direction."

"Hutch was just what we needed," said pitcher Jim O'Toole. "We had talent, but were rudderless. Hutch gave us direction."A classic player's manager, Hutch treated his players like men. There were few bed checks and he didn't obsess over physical errors. But woe to the man who made a mental error or failed to hustle.

After leading the team to the pennant in 1961, Hutch was the toast of Cincinnati. In 1963 he took a chance on a hustling second baseman named Pete Rose and inserted him in the lineup, even though most observers felt he needed more time in the minors. Hutch was looking forward to the 1964 season when in December, 1963 he admitted to his wife that he had a troublesome bump on his neck that seemed to be growing. She convinced him to call his brother Bill.

While Fred had been making a name for himself in baseball Bill, who had remained very close to Fred, had been having similar success in the field of medicine. A surgeon who specialized in cancer treatment, Bill was recognized as one of the most prominent cancer doctors in the northwest. Recognizing the need for organized research for the devastating disease, Bill had been working for years to raise money for a center dedicated to research for cancer. In December of 1963, he had his goal in sight: construction for the center was planned for the next year.

While talking to his brother Bill's trained ears picked up troubling words that he knew only too well. He convinced Fred to fly to Seattle immediately. After a battery of tests, Bill was forced to tell his brother some heartbreaking news: it was cancer of the lung. And in 1963 there was no cure. Fred had less than a year to live. There would be no sugar-coating of the news. "My father [Fred] told him, 'Give it to me straight, I want to know,'" said Fred's son Rick. "Bill laid it right on the line," said Patsy Hutcinson, Fred's wife. "He didn't hold anything back. Bill cried like a baby."But there would be no crying from Fred. He took the news, followed his brother's advice and planned to lead the Reds throughout the 1964 season. Family members, sports reporters and his team were amazed at the way Fred conducted himself throughout the season. He answered every question in his usual straight-forward manner and was never heard to utter any complaints or ask for sympathy. Team members sadly watched as the powerful man literally wasted away before their eyes throughout the summer.

Determined to finish the season, despite constant pain, Fred made it into August before he was forced to take a seat and allow coach Dick Sisler to take the reins the rest of the way. Reds players would have loved nothing more than to win one for Hutch, but sometimes real life doesn't match Hollywood. A late winning streak brought the club into the last game with a chance to force a tie for the pennant, but the Reds lost to Philadelphia and Jim Bunning. There wasn't a dry eye in the clubhouse as Fred appeared in street clothes, thanked his players for the season and promised to see them in the spring. "And you just knew to look at him that we weren't going to see him next spring," said rookie Billy McCool.

Fred passed away in early November. His stoic struggle against the fatal disease had been an inspiration to all. Sport magazine named him its Man of the Year for 1964. "Sometimes the world of games is a setting for an act of courage which glitters with meaning when measured by any yardstick," the accompanying article stated.

Bill Hutchinson stood by his brother until the end. In 1965 ground was broken for his long-awaited cancer center. There was little discussion when he decided to name it after his brother and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center was born. Today it is recognized as one of the top facilities of its kind in the world.

Friends and sports writers instituted the Hutch Award which is still given yearly in Seattle for the major league baseball player who best exemplifies the honor, courage and determination of Fred Hutchinson.

Fred Hutchinson, 1919-1964. "Hutch taught us all how to live, and when the time came, he taught us how to die." Gene Mauch.

Fred Hutchinson, 1919-1964. "Hutch taught us all how to live, and when the time came, he taught us how to die." Gene Mauch.

Published on August 05, 2019 06:58

March 7, 2019

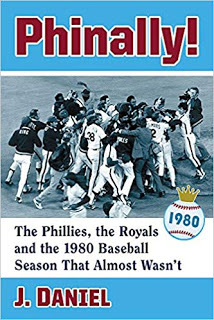

Book Review: Phinally!: The Phillies, the Royals and the 1980 Baseball Season That Almost Wasn't

There are some books that are just fun to read. They bring back memories, good and bad, of a particular moment in time. Phinally! by J. Daniel is one such book. It focuses on the events of the summer of 1980, providing a perfect time-capsule of the baseball season and popular culture. The 1980 season certainly contained it's share of memorable events and personalities and Daniel does a good job of covering them all.

The book opens with an entertaining review of the Philadelphia Phillies history of ineptitude, to prepare the reader for what the fans and players of the 1980 Phillies team were up against, battling not only other baseball teams, but the weight of ingrained institutional incompetence. Although the Phillies had experienced success in the late 1970s with several divisional titles, they had won only two pennants (none since 1950) and zero World Series championships in roughly a century of professional baseball.

In addition to baseball, Daniel also supplies an ample amount of cultural nostalgia to help set the scene. He opens spring with the "Who shot J.R.?" phenomenon and intersperses tales of the Blues Brothers, The Empire Strikes Back and Airplane!.

On the baseball field, the 1980 season was momentous for a number of reasons. Nolan Ryan became the first major leaguer to sign for the now-quaint sum of one million dollars. Billy Martin resurfaced in Oakland, took a team of underachieving no-names and drove the American League crazy for four months with Billy Ball. A curious rookie named Joe Charboneau showed up in Cleveland opening beer bottles with his eyelids, snorting jello (and other things) through his nose, all while lighting up American League pitchers and generating an excitement in Cleveland that would not be seen again for a rookie until Willie Mays Hayes and Rickie "Wild Thing" Vaughn. Despite having a player break the million dollar mark, players and agents were not happy as owners sought to re-establish control of both the game and their own checkbooks. The result was a labor unrest that hung heavy over the season and would result in the catastrophic strike that wiped out a third of the 1981 season.

George Brett mesmerized the nation throughout the summer of 1980 with one of the greatest hitting seasons of the last half-century, carrying a .400 average as late as September 20. He finished with more RBIs than games and more home runs (24) than strike outs (22). As fate would have it, Brett, sitting on more hype than any other player, developed a hemorrhoid that knocked him out of a World Series game. After emergency surgery, he quipped, "Hopefully my problems are all behind me."

Mike Schmidt shook off a sometimes testy relationship with Philadelphia fans and had a monster last month to finish with 48 home runs and 121 RBIs. He won the MVP award in the finest season of his Hall of Fame career and took the World Series MVP as well.

The NLCS between the Astros and Phillies was one of the most exciting postseason series in history. The last four games of the best-of-five series went into extra innings and the championship was not decided until the tenth inning of the final game--after the Phils, playing on the road, had dropped 5 runs on the Astros in the eighth, only to watch the Astros come back and tie it and send it into extra innings.

Daniel not only allows the reader to closely follow the pennant races, but gives ample time to the brawls, the oddities and the other aspects of the season. He presents the season in an organized, chronological style that moves quickly, preventing the reader from getting bogged down and shows a good eye for an anecdote.

Overall, this is a well-written, fun read. It's not just a book for Phillies fans, but baseball fans in general, particularly those who remember the 1980s or enjoy the history of the game.

Published on March 07, 2019 06:40

January 20, 2019

How Ernie Banks Revolutionized the Position of Shortstop*

*And where did those home runs come from?

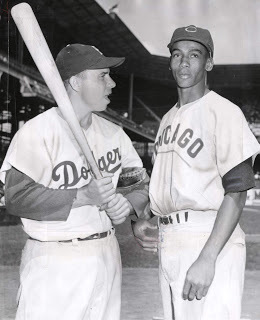

One of the unfortunate byproducts of Ernie Banks' Mr. Cub image being so great is that sometimes it obscures exactly how good of a player he was in his prime, before bad knees forced a move to first base. The present generation may not realize how he single-handedly revolutionized the position of shortstop.

Before Ernie joined the Chicago Cubs in September of 1953, shortstops were valued for their fielding and intrinsic virtues, but little was expected of them offensively. They were almost uniformly quick, feisty, pesky little guys with names like Scooter or Pee Wee (some were even named Pesky). They were respected leaders on the field and on offense might draw a walk for you, steal second base or slap a ball to right on a hit and run. Anything more was a bonus. If their team happened to win a pennant while they were hitting .267 with 6 homers and 63 RBIs (as Marty Marion did in 1944) or .324 with 7 homers and 66 RBIs (as Phil Rizzuto did in 1950), they walked away with an MVP trophy.

And then Ernie Banks started hitting. He had a solid rookie season in 1954 with 19 home runs and 79 RBIs--well above what was normally expected for a shortstop. The next year, he loosened up and the position was never viewed the same.

Ernie hit 44 home runs (including a major league record 5 grand slams) in 1955--a year in which he would not turn 24 until December. The previous National League record for home runs by a shortstop was 23--Ernie had that by the first week of July.

He proceeded to top 40 home runs in 5 of the next 6 seasons (a wrist injury in 1956 cost him 15 games and his power over the last two months).

Ernie was no slouch as a fielder. He didn't have the range of Aparicio, Reese or Wills, but he had sure hands and rarely threw a ball away. In 1959 he set a record for fewest errors in a season by a shortstop, with 12 and in 1960 he won a Gold Glove. These were nice accomplishments, but his value as a slugger in the middle of the infield would forever be unsurpassed.

Manny Machado, with his 37 home runs, generated a lot of talk last season of what an asset he was when installed into the lineup at shortstop because of his offense. Many modern writers mistakenly note that Cal Ripken is the prototype of the modern offensive-minded, slugging shortstop. While Ripken, at 6-4 and 200+ pounds, towered over Ernie's 6-1, 180 pounds (if he had 10 pounds of sweat in his flannel uniform), Ripken never hit more than 34 home runs in a season, even as he played half his career in a decade in which 66 home runs in a season wouldn't even win you a title.

In fact, until the steroid era, the top five slots for home runs by a Major League shortstop were all held by one man: Ernie Banks. And only one other player has ever topped Ernie's slugging numbers for a shortstop and that player is a documented serial steroid-abuser.

Only one other shortstop has ever hit 40 home runs in a season (Rico Petrocelli, 1969). Ernie remains as the most potent non-steroid-aided offensive force ever to take the field at shortstop in the major leagues.

But Where Did the Home Runs Come From?

Until the past few decades, amid the weight training, launch angles, walk/strike out/home run mentality and other factors, it was relatively difficult for any man to consistently hit major league pitches over the fence. While most players could hit home runs, only a few on each team did so with any regularity, say at a clip of 30 or more a year, and only a handful in each league did so for as much as a decade.

The men who were able to hit those home runs were all very impressive physical specimens. While muscles are certainly not the only requirement--extraordinary reflexes, eyesight and practice were also required--there was little doubt as to the source of the home runs of behemoths like Gehrig and Foxx.

The newer generation of power hitters in the 1950s, with Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and Frank Robinson, used overall athleticism and bat speed rather than raw brute strength.

But, again, seeing these guys up close--looking at the menacing layers of muscles, the guns, the brawny forearms, the six-packs--leaves little doubt that you would never want to throw a mediocre-fastball in the same zip code as these mashers.

In modern times, we had the confluence of talent and science to help provide even more home runs:

And then there was Ernie Banks.

Granted, Ernie towered over traditional 1950s shortstops like Pee Wee Reese by several inches. But check out this next picture:

Granted, Ernie towered over traditional 1950s shortstops like Pee Wee Reese by several inches. But check out this next picture:

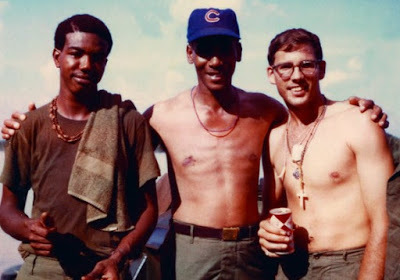

This was taken in Vietnam in 1968. Ernie, 37 years old and coming off a season in which he was third in the National League in home runs, is the one in the middle. The other two were 19-year-old GIs. Without the Cubs hat and familiar face, it would be difficult to predict from their builds which one of these guys was closing in on the top ten in all-time home runs. Look at Ernie's chest. He doesn't seem to have pectoral muscles--his chest is as flat as his stomach. Other than abnormally large hands, Ernie may have been the least imposing man to ever hit 500 home runs in a Major League career.

But consider the six years from 1955 to 1960:

Banks: 248 home runs, 693 RBIs

Mantle: 236 589

Mathews: 236 605

Mays: 214 611

Aaron: 206 674

Ernie was clearly the top slugger in the game over that period.

The source of Ernie's power, given his unimpressive physical attributes, sparked spirited debate during the last half of the 1950s. No one came up with a good answer. Ernie himself, along with most so-called experts, always gave credit to his wrists. But beyond basic anatomical facts (the wrist is composed of skin, bones and tendons--the muscles are in the forearms) that seems much too simplistic of an answer.

Most likely, the answer lies in the combination of many things--abnormally acute vision, a perfect weight shift, an abundance of fast-twitch muscle fibers and the carefully-honed ability to pull most pitches into his power field. It was a natural phenomenon like the Grand Canyon or Niagra Falls; beautiful to behold but impossible to recreate in the lab or on a field.

But few could do it better with less.

Published on January 20, 2019 11:38

September 14, 2018

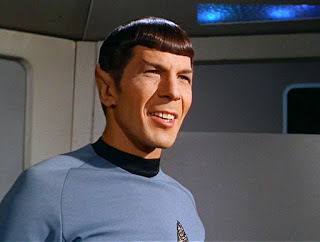

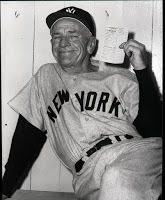

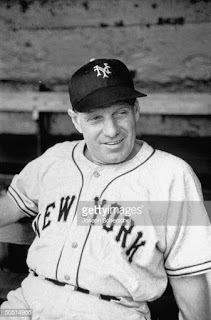

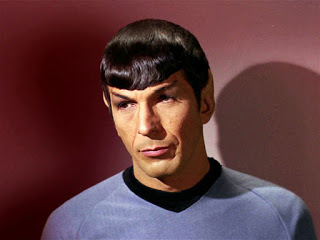

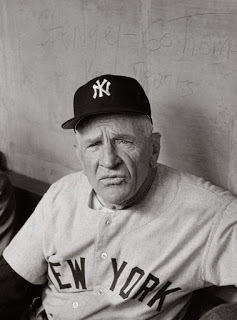

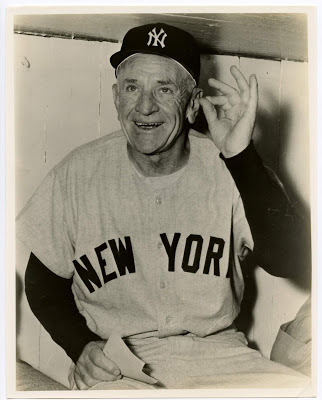

When Spock Met Casey and Leo: The Birth of Baseball Analytics

While Moneyball and the Sabermetric revolution have swept baseball in recent years, I have discovered that the origins can be traced to a unique meeting of minds that took place decades earlier. A recently released classified document, previously stored at a government facility in Roswell, New Mexico, sheds light on the subject.

It seems that the 22nd-century Starship Enterprise, in an effort to study primitive culture, used a warp-slingshot maneuver around the Sun to travel back in time and landed in mid-1950s New York City, where one member of the crew encountered and became enamored with the American game of baseball.

The scene opens as men are standing around a batting cage before an exhibition game between the Yankees and Giants:

Spock (talking to a funny-looking catcher wearing pinstripes): . . . and so, it is not logical for anything to be completed until it is, indeed, over.

Yogi: Yeah, I never thought about it like that. But that makes sense.

(Leo Durocher and Casey Stengel walk up.)

Leo: Hey, who's the elf? Get a load of those ears.

Yogi: Meet my new friend, Mr. Spock.

Spock (addressing the group): I have to say that I find myself strangely drawn to your game of baseball. It induces a curious emotion of enjoyment. We do not have anything similar on Vulcan.

Casey: Say, is that where you got those ears? I remember a feller on my team in Brooklyn back in '13 had ears like that. Couldn't hit worth a damn.

Spock: I've spent the last hour analyzing your scorebooks from the previous ten years and I believe I can help improve the efficiency of your decision making. Most importantly, I find that your reliance on human emotions, intuition and so-called tradition does not allow you to make the most logical of choices. I have compiled some facts which should help you. As you know, without facts you cannot decide with logic.

Casey: All that analysis is well and good, but what I need right now is a left-handed batter who can hit the ball over the shortstop's head.

Leo: I'm all for anything that will give me an edge. What do ya got?

Spock: First, the selection of players for your roster is most illogical. That can be improved immediately by proper statistical analysis to allow you to identify the most efficient players.

Leo: I don't need no numbers to tell me nothing like that. I know a ballplayer when I see one. And I also know the ones that ain't got the guts to play when things are tough.

Spock: Regrettably, history suggests that you do not. Not only that, but you are guilty of using a double negative. It does not make sense to play the same players in the same spots in the batting order every day, making no allowance for the pitcher or other variables.

Leo: That's a pile of crock. I know ball players. I can tell a winner from a loser just by looking at him. And I know how to make out a line up card. I play the hot hand, see. I got 30 years of experience to tell my gut what to do. Give me some scratching, diving, hungry players who come to kill ya. That's what I want.

Spock: And I can not understand your erroneous preoccupation with diminutive second basemen. Though the newspapers call them fiery sparkplugs, I fail to realize how an elevated basal temperature can help win games. You would be much better served by playing a larger man with an elevated launch angle in his swing at that position.

Leo: I don't want any of those big, slow guys--they can't help you win even if they do hit one outta the park every now and then.

Leo: I don't want any of those big, slow guys--they can't help you win even if they do hit one outta the park every now and then.Spock: Take your former man Stanky, for example. He could not hit, he could not run, he could not field . . .

Leo: Yeah, all the little sonovabitch could do was beat ya.

Spock: The little, to borrow your colorful metaphor, sonovabitch, could do one thing however: get on base. In 1950 he walked 144 times. That allowed him to reach first base in 46 % of his at bats. This, more than any nebulous intrinsic factor or annoying antics, was responsible for his value to winning games. This leads me to the next point: simply dividing the number of hits by the number of at bats is a poor evaluation of a batter's efficiency. I would submit that the percentage of times a batter reaches base, by either a hit or a walk, termed the on-base percentage, represents the highest good.

Leo: Aw, you don't know what your talking about. Give me a good pair of binoculars in the centerfield clubhouse, a bunch of scrappers and I'll win ya a damn pennant. I want guys who hustle, bunt, hit and run and steal. That's the type of club that wins.

Spock: I fail to understand your fascination with the so-called hit and run. First, it is an obvious misnomer as the runner runs, then the hitter hits. It should be called the run and hit. Second, according to my analysis, the risks far outweigh the benefits. I can find no plausible reason to employ this tactic.

As far as the bunt is concerned, I find it to be a most inefficient maneuver. While logic dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the individual, which would seem to favor the sacrifice, my research shows that a man on first with no outs has a 32.0381 % chance of scoring, whereas a man on second with one out has only a 27.57286 % chance.

Leo: But you're not taking into account who's at the plate and who's coming up behind him. Or whether the man on the hill is tired or can't field bunts. And what the crowd is doing. There's a lot more going on that your stats can't tell.

Spock: Also, it can be shown that unless you can be certain that a runner will be safe 72.95398 % of the time or more, it is illogical to attempt a steal. The advantage of gaining the extra base is simply outweighed by the risk of losing the all-important out.

Leo: But stealing unsettles the pitcher, moves the fielders and gets your team into the game. Not to mention the fans. Once they all get on their feet, everybody starts playing better. We get momentum.

Spock: I find your insistence on the archaic notion of rallies and momentum to be quaint, if not misguided. These concepts simply do not exist in nature.

Leo: You're full of it. Why, I've seen games won merely because the boys in the dugout got on the pitcher and he lost his edge. I've seen great hitters go into a slump after a pitcher sticks one in his ear. I've seen an entire Series lost by a rally that started with only a ground ball hitting a pebble. How do you and your numbers account for that?

Spock: The question is irrelevant. The facts are the truth merely because they are. No amount of arguing can change that. Once we eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, is indeed the truth.

Another erroneous assumption is that of the so-called clutch hitter. Logic dictates that a .300 hitter will be successful in 30 of 100 clutch situations, while a .250 hitter will be successful 25 times. The result is pure math. Human emotion and collective euphoria provide the impression that some men are better in tight situations than others, but in reality, they are not. Also, the RBI is perhaps the most flawed of your statistics. RBIs are merely the result of a man coming to bat with many men on base, nothing more.

Leo: Don't tell me that bull. I know in my heart that some guys are better when the chips are down. Take a nice guy. He won't win you as many games because he doesn't want it as much.

Spock: If you continue to rely on emotion, sir, you will forever be incapable of making a rational decision. You must accept the fact that many of your tactics are simply not supported by logic.

Leo: I'm getting tired of this guy. He ain't said nothing that makes any sense yet.

Spock: Sir, your disregard for simple grammatical rules is becoming alarming. As far as pitching, your insistence on keeping the statistic of Wins is not logical. A Win for a pitcher is a most ineffective measure of his success as it is dependent on far too many variables of which he can not control. Alternatively, I would suggest Walks Plus Hits Per Innings Pitched or WHIP.

Leo: I'll whip you, you pointy-eared freak. I've heard just about enough of your . . .

Spock: Also I would like to suggest a new measure of effectiveness for all players: Wins Against Replacement, or WAR. I would not expect someone with your primitive math skills to understand how it is calculated. You should just accept the efficiency of it.

Leo: Okay Tinkerbell, that's it. (Leo lunges for Spock and takes a swing. Spock side-steps the punch, places his hand on Leo's shoulder and squeezes. Leo slumps quietly to the ground).