A Spring Training Trip to the Ballpark, 1970 Style: Joe Pepitone and the Harmon Killebrew Home Run Ball That Wasn't

With no baseball in the foreseeable future, I have been thinking about the simple pleasures of childhood and a trip to the baseball park and what we might be missing this year. While all fans lament the cancellations, the games themselves can be replaced--there will be other games and other seasons. But a bigger loss comes for some parents and kids who are at a critical age. There is a special time in everyone's early life, a golden time to make memories; a temporary confluence of passion and wide-eyed innocence; a time of hope, when absolutely anything is possible. It is a fleeting time which, once lost, is gone forever and often is not even recognized until years later.

For the lucky, these days may be caught and will remain indelibly etched in the brain because they are so special, so memorable, so fun. The one day that remains special for me came in the spring of 1970. I've been to lots of baseball games since but none will ever compare with that one. And it had everything to do with the timing.

Baseball was not only important to me during that period, it seemed to be the most important thing I could imagine; an all-consuming passion. When not playing on my team or in pickup games or Wiffle ball games or whining my way into games with my older brother's friends, I was throwing a rubber ball against the side of the house, playing imaginary games in which I was the star of my major league team, hitting .400 while winning 30 games as a pitcher (I was nothing if not optimistic). Sometimes, I would toss the ball up, hit it and then dash around the bases of our backyard field, sliding in with triples and inside-the-parkers (always sliding--seems like the plays were invariably close) while imaginary fielders tried vainly to throw me out. The neighbors all suspected that I might be, as they used to say, a little bit touched in the head. However, nothing brought more pure joy.

We lived on an Air Force base not far from the spring home of the Minnesota Twins, Tinker Field in Orlando. The Twins were considered our hometown team and they were great. These were the Twins of Rod Carew, Jim Kaat, Tony Oliva and Jim Perry.

But the best of the best, my hero, was slugger Harmon Killebrew. He had been named MVP for the 1969 season after hitting 49 home runs and 140 RBIs. Killebrew had the reputation as a gentle giant who was nice to everyone. I was certain, deep in my heart, that we would be great friends if we could meet.

Our family had gone to a few spring training games in previous years but, perhaps because I was younger, they didn't seem to mean as much. But this year, 1970, was different. I was practically grown up--being in third grade--and figured I had learned quite a bit about the world. I had a whole year of organized baseball under my belt and was looking forward to the new season.

So the prospect of a trip to Tinker Field in the spring of 1970 with my parents, my brother and my best friend Freddie was met with great anticipation.The game we had picked was a Saturday afternoon contest against the Houston Astros.

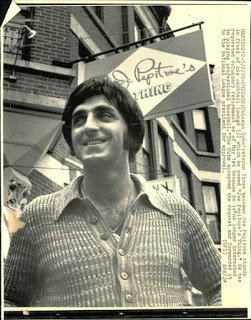

Seeing the Astros was exciting to my older brother because they had recently acquired Joe Pepitone. My brother was a budding adolescent. He still liked baseball, but for reasons neither of us quite understood his perception of the world was beginning to change--previously unimportant things like the Beatles and girls were now cluttering up his thoughts. Pepitone was the coolest guy in sports not named Joe Namath. He wore bell bottoms, wide collars with the buttons undone down to his waist and other apparel deemed mod. And then there was the hair. While most square players of the era were just starting to grow out their flattops, Pepitone was rocking a thick bushy mane scandalously over his ears. He was celebrated in the media as the first player to have a hair dryer in the clubhouse. In 1970 his on-field talent hadn't yet faded and he still had a little of the Yankee dynasty aura about him.

Freddie was one of those friends you are lucky to have once in a childhood; and only in childhood. We had everything in common: we both loved to play sports and collect sports cards. What else was there? With no knowledge of the baseball draft or the coming of agents, we had made a pact that we would both play for the Minnesota Twins when we grew up, although I secretly held out the unmistakable belief that if the Green Bay Packers asked me to play running back for them I would drop Freddie like a hot potato (I couldn't turn down my buddies Bart Starr and Donny Anderson could I?).

Freddie had a unique imagination and sense of logic. He was the first kid in the neighborhood to overcome the classic mother-vegetable conundrum. One day I knocked on his door to inform him of a game of backyard football that was about to begin. From the dining room I heard his mother's unpleasant voice, "Not until you finish all those peas!" Looking past him, I saw an enormous pile of creamed peas on his plate and quickly calculated that Freddie would not finish that imposing mess until the following June. But just as I was informing the other guys that Freddie would be a no-show for this game, I turned around and there he was, beaming a Cheshire cat grin. He slyly showed me his bluejean pocket--it was full of creamed peas. "She'll never know," he confidently boasted. However, when Freddie got dogpiled on one of the first plays, I suspected that she might find out sooner than he imagined.

When viewed through the rosy lens of 50 years, spring training games back then seem the same as everything else back then: simpler, better. The stadiums were small, quaint even, with a relaxed atmosphere and easy access to the field and players. The crowds were moderate but enthusiastic.

We parked in a grassy field behind the left-field wall, walked around to the front gate and were met by the unforgettable sights and smells of spring and baseball: sunshine, popcorn, hot dogs and cigar smoke. After purchasing our tickets, we made our way toward the field, mixing with people who were flowing excitedly in the same direction--old men, teenagers, dads with their kids--all talking with enthusiasm about the team and their expectations. To me, it was like walking through gates into the world's greatest carnival.

Then we spotted the holy grail, Xanadu and Shangri La all rolled into one: the souvenir stand. We were in a trance as we gazed upon the around-the-hornucopia of treasures we never even knew existed; scarcely believing the accessibility of such treasures to regular guys like us; scorecards, pencils bearing the team logo, t-shirts, miniature bats, caps and . . . real honest to goodness authentic, just-like-the-pros-wear plastic batting helmets. And only a buck and a quarter! We were amazed. And instantly sold. For a week in preparation we had ridden our bikes around the neighborhood collecting coke bottles to turn in for the two-cent refund and we each had a pocket full of ready cash. Me and Freddy both dumped almost our entire fortune on the helmets and then walked around the park the rest of the day feeling like the things had cost a million bucks. I'm not certain, but I seem to remember not taking mine off until I went to college. Years later I would get a lump in my throat when my son found it in the back of my old closet and wore it around all day.

I was introduced to the great people you invariably met at a ballgame in the days when a ticket set you back only a dollar or two. A guy sitting beside us had brought a seemingly endless supply of the biggest sub sandwiches I had ever seen. Two massive paws were not nearly enough to corral all the greasy contents and he continuously drooled condiments and spilled lettuce throughout the game, especially when something happened on the field. There was a loud, cigar-chomping guy sitting behind us who seemed to me to be the greatest authority on baseball I had ever heard. He knew everything and graciously dispensed this wisdom with anyone close. My mother didn't seem to appreciate the cheap cigar smoke, but to me it imprinted on my brain and to this day smells like the smell of a baseball game, even though cigars have not been allowed in a baseball park for decades. And with the guy loudly sharing his insight--on every batter, pitcher and managerial decision--I was struck with a sense of how lucky we were to sit so near an obvious expert.

The players were amazing. We were mesmerized as we watched their casual brilliance as they went about their chores--flicking magnificent throws and gracefully scooping balls out of the dirt in their perfect uniforms. There was no doubt that these were true gods descended from Olympus, yet they seemed so close, almost human. This gave us hope that it was indeed possible for mortals like us to fill their shoes one day, working at the best job in the world.

It was the first time we actually were old enough to go on safari for autographs by ourselves. Before the game we followed the big kids who had scorecards and baseball cards and tried to do what they did. These were 10- and 11-year-olds (how mature could you get?) who seemed to speak in perfect baseball language and knew all the players by sight. We could only dream of when we would be such men-about-the-world as that. One of the big kids even had a 1969 Harmon Killebrew baseball card, carefully holding it in his hands in hopes of getting it signed. Now I had several 1970 Killebrews already and had traded for a 1968--anything older was surely as rare as the Dead Sea Scrolls--but for some reason I had never been able to cop a '69. I tried to concentrate on the task at hand, all the while hating that kid and his 1969 Harmon Killebrew card.

Most of the stars were busy with their work, but that didn't matter to us. Anyone in a uniform was a prize. I'll never forget the kindness of a young Astros pitcher named Ron Cook as he patiently took time to not only sign for every kid, but to chat them up. He made a great impression on me as it had never occurred that a major league baseball player could actually speak to kids like they were real people. I had never heard of him before--he was a rookie--but he made a fan that day. I would watch for his name in the boxscores that summer, hoping for good fortune for him.

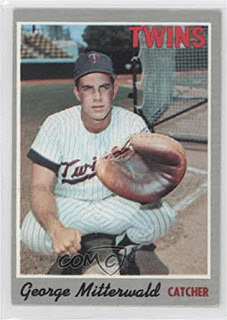

Several other players signed for us: Rick Renick, Jesus Alou, George Mitterwald, Paul Powell, Doug Radar . . . These guys would forever hold a place in my heart; the names would live on the little scraps of paper; essentially becoming the sum total of my autograph collection as the opportunity never again presented itself like that day.

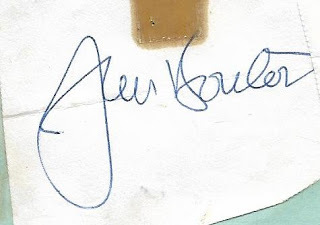

In a sweet serendipitous moment much later, I would discover the name of one other guy who signed for us kids that day. There was one name in the bunch I had never been able to discern. Fifty years later I would examine it once more and, only able to tell for certain that the last two letters of the last name were either -or or -on, survey the rosters for both teams. There was only one name that fit and comparing it to known autographs on-line, it was a perfect match. The man who had kindly given us his signature that day was unknown to us kids at the time--just another aging pitcher trying vainly to hang on. Of course in a few months every kid in the country would know his name when his diary of the preceding season was released under the title of Ball Four. It was none other than Jim Bouton.

In a sweet serendipitous moment much later, I would discover the name of one other guy who signed for us kids that day. There was one name in the bunch I had never been able to discern. Fifty years later I would examine it once more and, only able to tell for certain that the last two letters of the last name were either -or or -on, survey the rosters for both teams. There was only one name that fit and comparing it to known autographs on-line, it was a perfect match. The man who had kindly given us his signature that day was unknown to us kids at the time--just another aging pitcher trying vainly to hang on. Of course in a few months every kid in the country would know his name when his diary of the preceding season was released under the title of Ball Four. It was none other than Jim Bouton.

Of course at the time Harmon Killebrew was the great white whale for me. I was disappointed to learn that every kid in the stadium seemed to be in line trying to get to him also. He only batted once--a harmless ground out--and while we all clamored from the rail for his attention as he walked back to the dugout, he ignored us and kept walking. I heard the loud-mouth cigar chomper tell his kid that Killebrew was a bum because he wouldn't stop to sign for kids, making me think for the first time that maybe that guy didn't know everything. Even I understood that the game was in progress and the great man couldn't have been expected to stop to sign autographs. . . could he? I was pretty sure he would have stopped otherwise . . . wouldn't he?

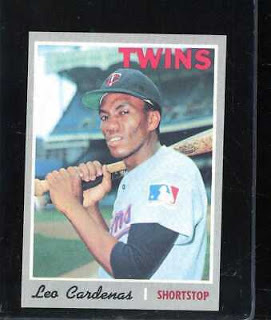

I only remember snippets of the game itself after that. I was particularly enchanted by the grace around second base of the Twins' shortstop Leo Cardenas. Since Mr. Cunningham, the coach on my farm league team, had played me almost exclusively at shortstop the previous year (and he had to know what he was doing because he carried a clipboard and wore a baseball cap) and combined with the fact that I had not yet learned of the institutional prejudice against lefthanders, I considered myself to be a future major league shortstop. I was enthralled by hearing the PA announcer drawing out his name also, "Leooo Cardennnnnnas;" a call I would repeat at the top of my lungs in the backyard as I played imaginary games against myself for the next few months.

Years later I would meet Mr. Cardenas with my son at a Reds Hall of Fame event and we would share a laugh and a memory of that day.

Years later I would meet Mr. Cardenas with my son at a Reds Hall of Fame event and we would share a laugh and a memory of that day.

The Twins rookie catcher George Mitterwald not only signed for me before the game (I didn't even realize it until I got home and deciphered some of the scribbles) but hit a monstrous home run over the left field wall--scaring my mother because it seemed to be aimed directly at the windshield of my dad's prized Oldsmobile (luckily we discovered after the game that it missed). I never imagined a ball could be hit so far; obviously we were watching a future Hall of Famer.

The home run impressed me so much that I distinctly remember having an argument in the school cafeteria the next week with a know-it-all named Callahan that Mitterwald was definitely better than Callahan's favorite catcher, a second-year man for the Reds named Bench (okay, in retrospect I'll admit I was perhaps a bit hasty and maybe just a little bit wrong--if you read this, sorry Callahan).

I have a vague memory of Twins' reliever Ron Perranoski coming in and blowing the game in the 9th and the loud-mouthed, cigar-chomping guy behind us explaining to one and all that the Twins would never be any good as long as that bum pitched for them (editor's note: the Twins would win the Western Division that year and Perranoski would lead the league in saves and have a 2.49 ERA, teaching me that sometimes you shouldn't believe everything the guy behind you in the stands says, no matter how certain he sounds--and now that I think of it, I'm pretty sure the cigars stunk too).

After the game we were allowed to wander about the place in search of more autographs, harassing the poor players who at that point just wanted to get out of the Florida heat (I remember Cesar Tovar hurriedly walking past us as we were separated from the players' trek to the clubhouse by a chainlink fence and thinking that I had never seen so much sweat dripping off a person in my life).

This is when my brother seized destiny with one hand while holding a pen in the other. While we waited outside the Twins clubhouse, he staked out the path from the Astro's clubhouse to their bus. He was not alone, however, as a hoard of other adolescents had the same idea: they were all waiting on Joe Cool. The mob allowed the other Astros to pass in peace but turned to a frenzy when they finally witnessed Pepitone stick his head out, check out the crowd, then bolt for the safety of the bus. He scribbled a quick scrawl on a few pieces of paper as he kept a quick pace wading through the kids, knowing that the only way to survive was to keep moving. Now I can't honestly say that I witnessed this, but family legend--passed down verbally many times since--holds that my brother actually followed Joe onto the bus, possibly grasping his shirt, disappeared, then reappeared at the door moments later waving his prize: a Joe Pepitone autograph.

But Freddy had even better luck than my brother. While we were waiting outside the Twins clubhouse, a ball boy stepped out with a bag of scuffed-up batting practiced balls and tossed them to the crowd. And one landed right in Freddy's eager hands.

The drive home was one of fatigue, sunburn and bliss. Me and Freddy wearing our Twins batting helmets; Freddy tossing his ball from hand to hand in the back seat all the way home; my brother rehashing his adventure with new-found buddy Joe Pepitone. There was now little doubt in my mind that baseball would be my life's work and I couldn't wait until I could be wearing the uniform with that beautiful TC on the cap, limbering up in the spring sunshine of Tinker Field and signing autographs for kids (I only hoped that Leo Cardenas would have moved on by the time I was ready as he looked to be a hard man to beat out for the shortstop job).

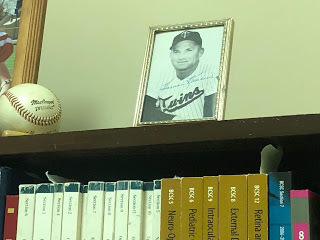

While I didn't get Harmon Killebrew's autograph that day, not long afterwards I wrote him a letter in my best penmanship and he rewarded me with an autographed picture that I still have sitting behind my desk in my office.

The next day while talking to my father, Freddy's dad mentioned how lucky Freddy had been to not only get a home run ball hit by Harmon Killebrew, but to snag the thing barehanded. As I mentioned, when Freddy went, he went big. My dad charitably kept quiet, allowing Freddy's story to go unchallenged.

All in all it was a glorious day. With time, the baseball cards would collect wrinkles and eventually be relegated to the back of our closet, the little pieces of paper with the scribbled names would be stored in a seldom-viewed scrapbook along with other childhood achievements, the photos taken on slides would fade; but the memories of the day would remain bright forever.

We swore we'd do it again, but we never did. Freddie's father was soon transferred and they moved away. A few years later Harmon Killebrew began to grew old and retired. I didn't quite make it to play shortstop for the Minnesota Twins. And Tinker Field was eventually torn down. Baseball would remain important, but somehow it never again seemed as important as it did that summer. Such are the friendships and dreams of eight-year-old kids.

Published on April 14, 2020 13:42

No comments have been added yet.

Doug Wilson's Blog

- Doug Wilson's profile

- 43 followers

Doug Wilson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.