Doug Wilson's Blog, page 7

February 26, 2016

Top Ten Lines in Baseball Movie History

Although the weather has started to warm up some places and baseball teams have gathered in camps across Florida and Arizona, we are still awaiting the start of baseball games for 2016. While we wait, baseball movies provide a reasonable alternative. With that in mind, I decided to offer my list of best lines from baseball movies.

I should apologize in advance to some excellent movies, like Rookie of the Year, Eight Men Out, Moneyball and It Happens Every Spring that didn't have any signature lines that stuck out in my mind enough to make my list. And if some movies seem over-represented here, it's just because they were that good.

Honorable Mention:

Bad News Bears (1976):

Bad News Bears (1976):

Ne'er do well Coach Buttermaker gives scrawny benchwarmer Lupus a classic bit of warm-and-fuzzy Little League coaching advice:

"Listen, Lupus, you didn't come into this life just to sit around on a dugout bench, did ya? Now get your ass out there and do the best you can."

* * *

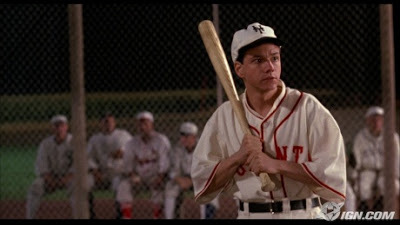

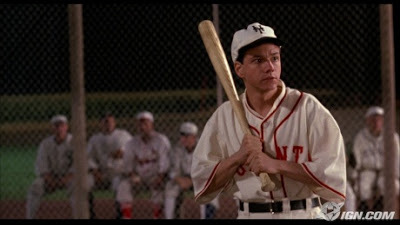

The Natural (1984)

The Natural (1984)

Good-natured manager Pops wants nothing more from life than to win a pennant before his time is finished. Roy Hobb (Robert Redford) shows up after his illness and tells Pops he's ready to take the field for the big game with the pennant on the line.

Pops: "You know, my mama wanted me to be a farmer."

Roy Hobbs: "My dad wanted me to be a baseball player."

Pops: "Well, you're better than any player I ever had. And you're the best goddamn hitter I ever saw. Suit up."

* * *

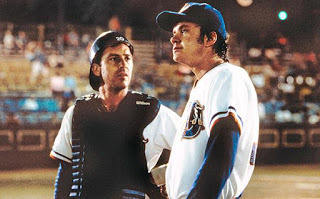

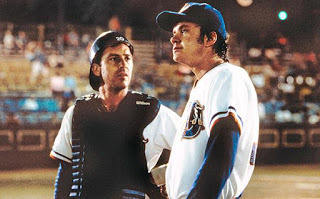

Bull Durham (1988)

Minor League lifer Crash Davis has his hands full trying to teach talented young pitching phenom Nuke Laloosh how to both play and repect the game.

"Lesson number one: don't think; it can only hurt the ball club."

* * *After Laloosh shakes off his signs and insists on throwing a fastball, Crash tells the batter what's coming, resulting in a monster home run.

Nuke: "That sucker teed off on that like he knew I was gonna throw a fastball."

Crash: "He did know."

Nuke: "How?"

Crash: "I told him."

In a later game, when Laloosh shakes off his signs, insisting on throwing a curve, Crash (to batter) "This SOB is throwing a two-hit shutout. He's shaking me off. You believe that shit? Charlie, here comes the deuce. And when you speak of me, speak well."

Crash, to Laloosh on the mound after the home run: "Man that ball got outta here in a hurry. I mean anything travels that far oughta have a damn stewardess on it."

* * *

"Relax, all right? Don't try to strike everybody out. Strike outs are boring. Besides that, they're fascist. Throw some ground balls, it's more democratic."

* * *

Bang the Drum Slowly (1973)

For guys afraid to show their sensitive side, it's time to make a run for the kitchen when the New York Mammoth's left-handed twenty-game winner and author Henry Wiggen offers this eulogy for his recently departed teammate Bruce Pearson (played by a young Robert DeNiro):

"He wasn't a bad fella, no worse than most and probably better than some. And not a bad ballplayer neither, when they gave him a chance, when they laid off him long enough. From here on in, I rag on nobody."

* * *

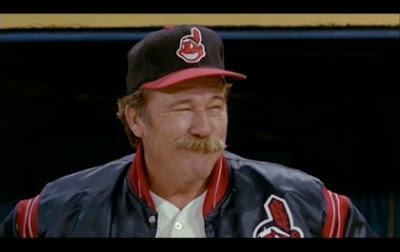

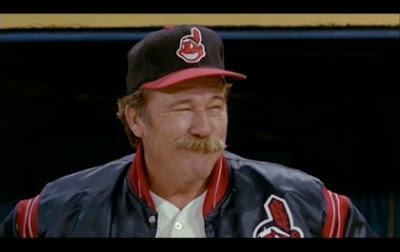

Major League (1989):

Everything Bob Uecker as announcer Harry Doyle says is a classic. It's hard to choose one.

"Juuust a bit outside. . . . . [after 12 straight balls] How can those guys lay off pitches that close?"

"Haywood leads the league in most offensive categories, including nose hair. When this guy sneezes he looks like a party favor."

"Rickie Vaughn gets the starting call today. We're told he matured a lot over the winter. Apparently he's bathing now."

"Obviously Taylor's thiniking . . . I don't know WHAT the hell he's thinking."

"One hit? That's all we got, one goddamn hit? . . . . Don't worry, nobody's listening anyway."

* * *

Bad News Bears (1976)

The irrepressible Tanner, who earlier fought the entire seventh grade after a loss, speaks for anyone who was ever sickened by hypocritical arrogant winning Little League teams when he tells them "Hey Yankees. You can take your apology and your trophy and shove 'em straight up your ass."

* * *

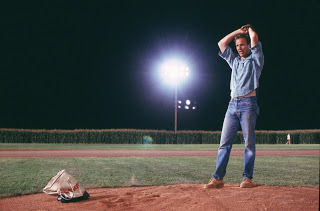

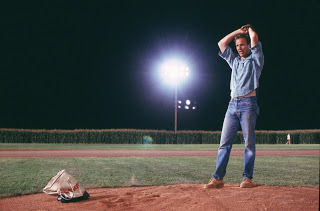

Field of Dreams (1989)

Field of Dreams (1989)

As Moonlight Graham, now a doctor for all time, walks off the baseball field, Shoeless Joe shouts, "Hey rookie, you were good."

* * *

Pride of the Yankees (1942):

Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig: "Today (ay, ay) I consider myself (elf, elf), the luckiest man on the face of the earth." What more needs to be said.

* * *

10) A League of Their Own (1992)

All the way Mae (played, appropriately, by Madonna) discussing ways to increase attendance at their games, offers: "What if at a key moment in the game, my uniform burst open and, uh, oops, my bosoms come flying out?"

To which Rosie O'Donnell's character replies: "You think there are men in this country who ain't seen your bosoms?"

* * *

9) The Sandlot (1993):

Appearing in a dream, Babe Ruth gives Bennie the Jet Rodriguez this timeless advice, "Heroes get remembered, but legends never die."

* * *

8) Field of Dreams (1989):

As he prepares to pitch to Shoeless Joe, Kevin Costner asks, "Do we need a catcher?"

Joe replies, "Not if you get it near the plate we don't."

* * *

7) Bull Durham

7) Bull Durham

The manager sends the coach out to break up a gathering on the mound that involves the entire infield. When the dutiful coach arrives, he finds out there's a long list of problems being discussed. The result is the greatest pitching mound conference in history:

"Well, Nuke's scared because his eyelids are jammed and his old man's here. We need a live rooster to take the curse off Jose's glove and nobody seems to know what to get Millie or Jimmy for their wedding present. We're dealing with a lot of shit."

The coach nods thoughtfully and then suggests, "Well, uh, candlesticks always make a nice gift, and, uh, maybe you could find out where she's registered and maybe a place-setting or a nice silverware pattern. Okay, let's get two. Go get 'em."

* * *

6) Field of Dreams (1989)

6) Field of Dreams (1989)

Young Moonlight Graham, annoyed after being brushed back by two straight pitches, turns and asks, "Hey ump, how about a warning?"

The umpire answers, "Sure kid, watch out you don't get killed."

* * *

5) Bull Durham (1988)

5) Bull Durham (1988)

The manager, after being told by Crash to try to scare the kids on the team, delivers this harangue:

"You lollygag the ball around the infield. You lollygag your way down to first. You lollygag in and out of the dugout. You know what that makes you? Larry!"

Assistant coach, Larry: "Lollygaggers!"

* * *

4) Major League (1989)

4) Major League (1989)

The uber-confident Willie Mays Hayes introduced himself as "I run like Hayes and hit like Mays."

After watching him flail helplessly in the batting cage, manager Lou Brown croaks, "You might run like Hayes, but you hit like shit."

* * *

3) The Sandlot (1993)

3) The Sandlot (1993)

Ham, exasperated by Smalls' continually nerdish ways, utters the immortal line:

"You're killing me Smalls."

* * *

2) Little Boy Boo (1954)

2) Little Boy Boo (1954)

In the less-than-politically-correct 1950s, before soccer moms were even a glint in Bill Clinton's eye, a real man's man like Foghorn Leghorn could plainly state what every male at the time knew deep in his heart:

"There's something, I say, there's something kind of eeeeyeeee about a kid that's never played baseball."

* * *

1) A League of Their Own (1992)

1) A League of Their Own (1992)

Tom Hanks is less than sympathetic when one of his players starts crying during a game.

"There's no crying in baseball. . . Rogers Hornsby was my manager and he called me a talking pile of pigshit. And that was when my parents drove all the way down from Michigan to see me play the game. And did I cry? No. And you know why? Because there's no crying in baseball."

I should apologize in advance to some excellent movies, like Rookie of the Year, Eight Men Out, Moneyball and It Happens Every Spring that didn't have any signature lines that stuck out in my mind enough to make my list. And if some movies seem over-represented here, it's just because they were that good.

Honorable Mention:

Bad News Bears (1976):

Bad News Bears (1976):Ne'er do well Coach Buttermaker gives scrawny benchwarmer Lupus a classic bit of warm-and-fuzzy Little League coaching advice:

"Listen, Lupus, you didn't come into this life just to sit around on a dugout bench, did ya? Now get your ass out there and do the best you can."

* * *

The Natural (1984)

The Natural (1984)Good-natured manager Pops wants nothing more from life than to win a pennant before his time is finished. Roy Hobb (Robert Redford) shows up after his illness and tells Pops he's ready to take the field for the big game with the pennant on the line.

Pops: "You know, my mama wanted me to be a farmer."

Roy Hobbs: "My dad wanted me to be a baseball player."

Pops: "Well, you're better than any player I ever had. And you're the best goddamn hitter I ever saw. Suit up."

* * *

Bull Durham (1988)

Minor League lifer Crash Davis has his hands full trying to teach talented young pitching phenom Nuke Laloosh how to both play and repect the game.

"Lesson number one: don't think; it can only hurt the ball club."

* * *After Laloosh shakes off his signs and insists on throwing a fastball, Crash tells the batter what's coming, resulting in a monster home run.

Nuke: "That sucker teed off on that like he knew I was gonna throw a fastball."

Crash: "He did know."

Nuke: "How?"

Crash: "I told him."

In a later game, when Laloosh shakes off his signs, insisting on throwing a curve, Crash (to batter) "This SOB is throwing a two-hit shutout. He's shaking me off. You believe that shit? Charlie, here comes the deuce. And when you speak of me, speak well."

Crash, to Laloosh on the mound after the home run: "Man that ball got outta here in a hurry. I mean anything travels that far oughta have a damn stewardess on it."

* * *

"Relax, all right? Don't try to strike everybody out. Strike outs are boring. Besides that, they're fascist. Throw some ground balls, it's more democratic."

* * *

Bang the Drum Slowly (1973)

For guys afraid to show their sensitive side, it's time to make a run for the kitchen when the New York Mammoth's left-handed twenty-game winner and author Henry Wiggen offers this eulogy for his recently departed teammate Bruce Pearson (played by a young Robert DeNiro):

"He wasn't a bad fella, no worse than most and probably better than some. And not a bad ballplayer neither, when they gave him a chance, when they laid off him long enough. From here on in, I rag on nobody."

* * *

Major League (1989):

Everything Bob Uecker as announcer Harry Doyle says is a classic. It's hard to choose one.

"Juuust a bit outside. . . . . [after 12 straight balls] How can those guys lay off pitches that close?"

"Haywood leads the league in most offensive categories, including nose hair. When this guy sneezes he looks like a party favor."

"Rickie Vaughn gets the starting call today. We're told he matured a lot over the winter. Apparently he's bathing now."

"Obviously Taylor's thiniking . . . I don't know WHAT the hell he's thinking."

"One hit? That's all we got, one goddamn hit? . . . . Don't worry, nobody's listening anyway."

* * *

Bad News Bears (1976)

The irrepressible Tanner, who earlier fought the entire seventh grade after a loss, speaks for anyone who was ever sickened by hypocritical arrogant winning Little League teams when he tells them "Hey Yankees. You can take your apology and your trophy and shove 'em straight up your ass."

* * *

Field of Dreams (1989)

Field of Dreams (1989)As Moonlight Graham, now a doctor for all time, walks off the baseball field, Shoeless Joe shouts, "Hey rookie, you were good."

* * *

Pride of the Yankees (1942):

Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig: "Today (ay, ay) I consider myself (elf, elf), the luckiest man on the face of the earth." What more needs to be said.

* * *

10) A League of Their Own (1992)

All the way Mae (played, appropriately, by Madonna) discussing ways to increase attendance at their games, offers: "What if at a key moment in the game, my uniform burst open and, uh, oops, my bosoms come flying out?"

To which Rosie O'Donnell's character replies: "You think there are men in this country who ain't seen your bosoms?"

* * *

9) The Sandlot (1993):

Appearing in a dream, Babe Ruth gives Bennie the Jet Rodriguez this timeless advice, "Heroes get remembered, but legends never die."

* * *

8) Field of Dreams (1989):

As he prepares to pitch to Shoeless Joe, Kevin Costner asks, "Do we need a catcher?"

Joe replies, "Not if you get it near the plate we don't."

* * *

7) Bull Durham

7) Bull DurhamThe manager sends the coach out to break up a gathering on the mound that involves the entire infield. When the dutiful coach arrives, he finds out there's a long list of problems being discussed. The result is the greatest pitching mound conference in history:

"Well, Nuke's scared because his eyelids are jammed and his old man's here. We need a live rooster to take the curse off Jose's glove and nobody seems to know what to get Millie or Jimmy for their wedding present. We're dealing with a lot of shit."

The coach nods thoughtfully and then suggests, "Well, uh, candlesticks always make a nice gift, and, uh, maybe you could find out where she's registered and maybe a place-setting or a nice silverware pattern. Okay, let's get two. Go get 'em."

* * *

6) Field of Dreams (1989)

6) Field of Dreams (1989)Young Moonlight Graham, annoyed after being brushed back by two straight pitches, turns and asks, "Hey ump, how about a warning?"

The umpire answers, "Sure kid, watch out you don't get killed."

* * *

5) Bull Durham (1988)

5) Bull Durham (1988)The manager, after being told by Crash to try to scare the kids on the team, delivers this harangue:

"You lollygag the ball around the infield. You lollygag your way down to first. You lollygag in and out of the dugout. You know what that makes you? Larry!"

Assistant coach, Larry: "Lollygaggers!"

* * *

4) Major League (1989)

4) Major League (1989)The uber-confident Willie Mays Hayes introduced himself as "I run like Hayes and hit like Mays."

After watching him flail helplessly in the batting cage, manager Lou Brown croaks, "You might run like Hayes, but you hit like shit."

* * *

3) The Sandlot (1993)

3) The Sandlot (1993)Ham, exasperated by Smalls' continually nerdish ways, utters the immortal line:

"You're killing me Smalls."

* * *

2) Little Boy Boo (1954)

2) Little Boy Boo (1954)In the less-than-politically-correct 1950s, before soccer moms were even a glint in Bill Clinton's eye, a real man's man like Foghorn Leghorn could plainly state what every male at the time knew deep in his heart:

"There's something, I say, there's something kind of eeeeyeeee about a kid that's never played baseball."

* * *

1) A League of Their Own (1992)

1) A League of Their Own (1992)Tom Hanks is less than sympathetic when one of his players starts crying during a game.

"There's no crying in baseball. . . Rogers Hornsby was my manager and he called me a talking pile of pigshit. And that was when my parents drove all the way down from Michigan to see me play the game. And did I cry? No. And you know why? Because there's no crying in baseball."

Published on February 26, 2016 07:01

February 20, 2016

The Bobby Tolan Basketball Injury Revisited: Literary Foreshadowing and Managers Know Best

Two innocent articles appeared on the pages of the Sporting News in November of 1970 which would be related to events that would have a profound effect on the Cincinnati Reds franchise. The articles appeared November 21 and November 28 and were both written by the Cincinnati Post's Earl Lawson, who also moonlighted as the Sporting News' columnist for the Reds. The first article was entitled "Sparky Turns Off Ignition On Big Red Cage Machine." The next weeks' headline was "Basketball Touchy Subject to N.L. Champ Reds," and is accompanied by a picture of Pete Rose in a warmup suit toweling himself off, presumably after playing basketball. At first glance, they appear to be the usual postseason space-filler--something to eat up copy between the World Series and the hot-stove league. A reader who knows the rest of the story, however, is struck by a sense of irony and foreshadowing, as well as--if the reader is a Reds fan--foreboding.

In the old days--before year-round select travel programs for kids in every sport starting at 6 years old--the best athletes played every sport. So it should not be surprising how many great baseball players were also stand-out basketball stars.

Johnny Bench was an All-State high school basketball player in Oklahoma and led his team to the state semifinals in 1965. Brooks Robinson made All-State and was mentioned in a national publication for his efforts for Little Rock Central High School in 1954 and 1955. Frank Robinson, in Oakland, led his team to the state championship, although he had a bit of help from a talented teammate named Bill Russell. Future Red Sox teammates Carl Yastrzemski (in Long Island) and Rico Petrocelli (in Brooklyn) regularly dropped 30 or more points a game on opponents.

Carlton Fisk led his high school team to an undefeated New Hampshire state championship in 1963 as a sophomore and, in his final high school game, in the semifinals in 1965 he set a still-standing state record for most field goals (18) in a state tournament game while scoring 40 points and pulling down 36 rebounds. Jim Palmer led the state of Arizona in scoring as a senior in the early 1960s and was recruited by UCLA's John Wooden. Had he not pursued baseball, he could have won three NCAA championships.

Although no high school star himself, Pete Rose regularly played basketball throughout the off-season in his early years with the Reds. Being a hometown Cincinnati guy, he stayed in the area in the winter and used his contacts to get on a bunch of teams. Some years he was on as many as four different amateur teams, regularly playing in AAU leagues and tournaments throughout the Cincinnati area.

Rose, of course, was the point guard who told everyone what to do; good at driving and dishing. He was also not above a little elbow-throwing or butt-pinching under the basket if needed. Soon after Johnny Bench joined the Reds at the end of the 1967 season, Rose recruited him for several of his teams. Bench, who had been able to palm a basketball with his massive paws since junior high and could dunk in high school, still had a deft jump shot. And if the wide-shouldered, cat-quick Bench wanted a rebound, no one else had a chance.

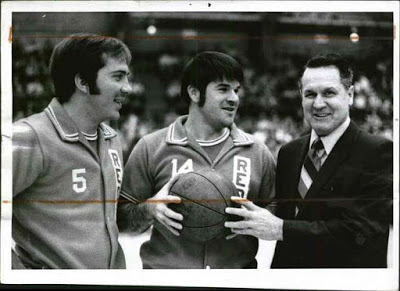

After the 1968 baseball season the Reds front office decided it would be safer for them to sponsor a basketball team and play exhibitions rather than have some of their best stars risk injury in rough and tumble amateur games. General manager Bob Howsam not only gave his approval for the official Reds basketball team, but paid for snazzy new uniforms and warmups. They played local teams for charity all around the area, as well as in Kentucky and Indiana; playing collections of teachers, firemen, policemen, local celebrities and the like. Sometimes the gate was split, allowing the players to pick up some extra cash--not an unimportant enticement in those reserve clause days.

But often these were no laid-back affairs. Once on the floor, with the natural competitive juices flowing, the games sometimes became hard fought, with neither team conceding anything. It would obviously be a great feather in the cap of any team to be able to later brag that they had once defeated the mighty Big Red Machine--even if it wasn't in their natural game of baseball.

After the 1969 season, the Reds basketball team played a schedule of more than 30 games. In addition to Bench and Rose, Lee May, Jim Maloney and infielder Jimmy Stewart were regulars, along with a couple of Rose's local friends for fillers. Jim McGlothlin and Bobby Tolan were picked up for 1970. Although his numbers were overshadowed by the teams' slugging stars, everyone in baseball recognized that centerfielder Tolan was obviously a budding star. He was coming off two terrific seasons. In 1970 he had hit .316 with 16 home runs, 80 RBIs and swiped 57 bases. At 25, he figured to only get better. More importantly, along with the slower Rose and the shortstop de jour, Tolan provided the only semblance of speed in the Reds lineup.

Manager Sparky Anderson had seen the basketball team play only once in the previous winter. "Unfortuntely, it was the roughest game we played all season," Rose told Lawson. "I even got into a brawl. We played a small school and the guys on the other team got mad."

In November of 1970, fresh off a great season in which the Reds dominated the National League but came up short in the World Series, Sparky Anderson, fearing injury to a key player, wanted to rule out the formation of a "Reds" basketball team. He had no trouble convincing his boss Bob Howsam to back the decision.

Rose was quoted as saying, "Some guys can keep in shape by exercising and running around a gym track. I have to do something that's competitive. You do that and you're always thinking about winning. And that's a spirit a guy should develop."

"We realize players must keep active during the off-season to remain in shape," Howsam's assistant Sheldon Bender countered. "But basketball presents too much of a risk." As an alternative to basketball, the Reds purchased a new universal weight machine for their clubhouse and set up an organized conditioning program for the first time. Perhaps indicative of the prevailing opinions of weight training for baseball at the time, when backup shortstop Darrell Chaney asked one of the coaches if lifting weights would improve his batting average, the coach replied, "No, but you'll look better sitting on the bench."

While the players reluctantly agreed to Anderson's edict, they did convince him to allow them to play four or five games which had already been set up with numerous advanced tickets purchased. And in general, a good time was had by all, such as the game in Connorsville, Indiana November 14, 1970 when a crowd of 3,500, paying $1.50 each, crammed into the high school gym to watch. The players signed autographs during half time and tossed 72 autographed baseballs into the crowd. Rose termed it "Great public relations for the Reds."

Another game that had been heavily pre-sold was in Frankfort, Kentucky in January. During that game, Bobby Tolan stopped suddenly to retrieve a loose ball. Although no one was within five feet of him, he collapsed and couldn't get up. The back of his foot felt as though he had been kicked by a steel-toed boot. He had completely torn his Achilles tendon. He would miss the entire 1971 season.

It was the first, and possibly most important, in a series of unfortunate events that would completely derail the early version of the Big Red Machine, leading to a disappointing 79-83 record and a fourth place finish for the young team predicted to be a dynasty.

Although Tolan made a fine comeback for the 1972 pennant-winning Reds, hitting .283 and he played in the majors through 1979, he was never again the same version of the near-dominant player of 1969 and 1970. And after the accident, Bob Howsam put his foot down--there would be no more Cincinnati Red basketball after 1971.

And so, looking at the two seemingly innocent articles from 46 years ago, one can only wonder what would have happened to the Big Red Machine, and Bobby Tolan, if the players had heeded Sparky's warning in November of 1970 to stop playing basketball. Would a healthy Bobby Tolan have been enough to offset the injuries to the pitching staff and slumps of Bench, Carbo and Perez? If not enough to win a pennant, would it have been enough to have the decent finish, say second place, that would have prevented Howsam from feeling that he needed to overhaul the team with The Deal that brought Morgan, Billingham, Geronimo et al and led to future greatness?

Questions such as these keep fans and ex-managers awake on long winter nights.

Published on February 20, 2016 16:41

January 22, 2016

And Then Pudge Said to Spaceman: Conversations From Major League Mounds

One of my favorite scenes from the movie Bull Durham occurs on the pitcher's mound. The manager sends the coach out to break up an abnormally long conference involving the entire infield. When the dutiful coach arrives, he finds out that the long list of problems being discussed includes the fact that the pitcher is "scared because his eyelids are jammed and his old man's here." Also, they need a live rooster to take the curse off Jose's glove and "nobody seems to know what to get Millie or Jimmy for their wedding present. . . .we're dealing with a lot of shit."

The coach nods thoughtfully and then suggests, "Well, uh, candlesticks always make a nice gift, and, uh, maybe you could find out where she's registered and maybe a place-setting or a nice silverware pattern.Okay, let's get two. Go get 'em."

Surprisingly, a lot of major league pitching mound conferences are not that different.

Carlton Fisk was known as a steely commander behind the plate. Part of his job description included being a psychologist to struggling pitchers as well as occasionally kicking some butt. He received a quick lesson on what veteran pitchers expected during a late-season call up in 1971. Tough lefty Gary Peters was on the mound for the Sox and appeared to be struggling. The rookie catcher thought, "Well, I'm supposed to take charge here," and walked out to talk to his pitcher.

Peters, greatly annoyed at having given up a couple of weak ground ball hits, was in no mood to be bothered. He turned his back and stood behind the mound. Fisk, not knowing what else to do in front of fans and teammates, patiently waited. Finally, Peters turned around and was not happy to find the rookie still there. "What the F*** do you want?" he snapped.

Fisk, surprised at the assault, just shrugged. "The next time you come out here, you better have a pretty good idea how we're going to get out of this situation," snarled Peters. "Get your ass back behind the plate." It was Fisk's Welcome to the Big Leagues moment. He dutifully walked back behind the plate, but it was the last time a pitcher would ever chase Carlton Fisk off a mound.

Fisk and outspoken teammate Bill Lee had some memorable confrontations on the mound. Temporary roommates in their first stop in the minors, in Waterloo, Iowa in low A ball in 1968, they were friends and each held respect for the competitiveness and ability of the other. This friendship and respect vanished completely, however, when Fisk began one of his slow, studied walks to the mound during an inning.

Lee liked to work fast and often threw pitch sequences which defied any explanation other than by his own convoluted thought process that few human beings could follow. Even though these pitches were successful more often than not, they drove the conservative catcher absolutely nuts. And Fisk drove Lee nuts by taking his time during the game. Confrontations were inevitable.

Lee later said that he immediately became irritated by the slow, deliberate way Fisk called a game. "He was . . .slow at putting down signs. I used to think, 'Jesus, what's taking him so long? I've only got two pitches.'

Lee wrote, "Fisk demanded your total concentration during a game. If you shook him off and then threw a bad pitch that got hit out, he had a very obvious way of expressing his displeasure. After receiving a new ball from the umpire, he would bring it out to you . . . There would be an expression on his face that said, 'If you throw another half-ass pitch like that, I'm going to stuff this ball down your throat.'"

By the mid-70s Lee and Fisk provided public entertainment on the mound. They were known to have shouting matches in the middle of the infield. Lee would shake him off just for the fun of it. Sometimes when Fisk would start out to the mound, Lee would turn and walk toward second base, making Fisk follow him.

One game Lee shook Fisk off six consecutive times. Fisk came out to the mound and yelled, "How the hell can you shake me off six times! I've only got five fingers!"

Lee: "My point exactly."

Lee: "Who knows better than I do what kind of stuff I have."

Fisk "Your catcher."

Lee, admittedly sometimes excitable on the mound, said Fisk would help by calming him down--"By screaming at me. 'Cut the shit, bear down, and we'll get two.'"

Bill Lee was far from the only pitcher who enjoyed Fisk's brand of motherly love. Sometimes Fisk would come out and fire, "What the hell are you doing out here?" Often, he would purposely goad the pitcher, like when he used to ask Marty Pattin, "When are you going to put the ball over the plate, Martha?" Sometimes Pattin would respond as planned, sometimes not. Once when Fisk stalked to the mound after Pattin gave up a couple of long fouls to a hitter, Pattin shouted, "You do the catching and I'll do the pitching," and the pitching coach had to rush to the mound to separate them.

Once, young pitcher Don Aase was laboring and told Fisk he was tired. The catcher snapped, "Bear down, you've got all winter to rest."

Pitcher Jim Wright, a rookie in 1978, said in a spring training game, after he gave up a monstrous line-drive home run to Johnny Bench, Fisk strolled out to give him a new ball and said, "Don't worry, that wouldn't have gone over the Green Monster. It might have gone through it . . ."

But it wasn't all sarcasm and growls. Wright said, "He was different with everybody. Some guys he really got on, others he was more of a cheerleader. He learned what worked best with each pitcher. . . One game I had given up a few runs and my curveball was hanging. He came out and told me, 'You don't have your curveball today, it's getting you in trouble. So we're going to do it with your fastball. We'll show them a few sliders, but it's going to be the fastball mostly. The rest of the game that's what we did. I just threw wherever he put his glove and I made it into the ninth inning."

The Orioles Jim Palmer and Earl Weaver, both of whom felt they needed no help whatsoever with anything, had some memorable mound exhibitions. Palmer, who frequently said that the only thing Weaver knew about pitching was that he couldn't hit it, would purposely stand on the very top of the mound, taking the high ground, to further emphasize the difference in their heights and to force the diminutive Weaver to look up at him.

Weaver frequently resorted to reverse psychology. Once when a spent Palmer asked him to take him out in the ninth inning of a close game, Weaver said, "Look down there at the bullpen. Do you think we've got anybody down there who's as good as you?"

Big Red Machine manager Sparky Anderson, known as Captain Hook for his proclivity to yank pitchers, by rule brooked no conversation with a pitcher on the mound. He simply held out his hand and expected the ball to be placed there. Once when a rookie, Pat Darcy, in the excitement of the moment, asked to stay in the game, and told him, "I feel good, Skip." Anderson didn't miss a beat. He answered, "Yeah, but you'll feel a lot better in the shower."

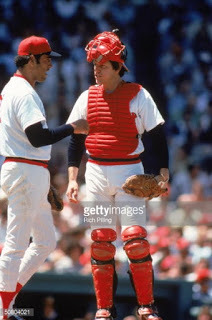

With no outs and a man on third in the ninth inning of a tied Game Six of the 1975 World Series, young reliever Will McEnaney, a left-hander in every sense of the word, crossed up catcher Johnny Bench on a two-strike pitch to dangerous Fred Lynn, throwing a fastball instead of a breaking pitch. Lynn lifted a fly ball down the left field line that was caught by George Foster, whose throw home to get the tagging runner was in time but took a high hop off the grass. Bench made a great play to hold his position, blocking the plate while reaching up to get the ball and then making the tag--narrowly avoiding disaster. After the play, an angry Bench went to the mound to confront McEnaney, "Will, what the hell? You crossed me up. I gave you the slider sign. You know the sequence."

Bench was surprised to find the pitcher ecstatic and unapologetic. "Yeah, I guess I did. But heck, John, those things work out, don't they?" For one of the only times in his career, Bench was speechless.

When the umpire walked out to keep the game moving and asked, "What's going on?" Bench could only shake his head. "You wouldn't believe it if I told you."

John McNamara was obviously feeling a little nervous about the start of the 1979 season as the new manager of the Reds. After all, the man he was replacing, Sparky Anderson, had only won five division titles, four pennants and two World Series in the past nine years. He felt a little better on Opening Day with his ace Tom Seaver on the mound, giving the Reds the top Hall of Fame vote-getting battery in baseball history (Seaver was elected in 1992 with 98.84% and Bench in 1989 with 98.4% , the first and eleventh highest in history before this year). Seaver wasn't sharp, however, and the Reds were quickly trailing. When the dyspeptic manager went to the mound in the fourth inning, already trailing by five runs in the new season, a smiling Bench greeted him with, "Enjoying your new job so far, John?"

So the next time you see players and coaches congregating on the mound just remember, they might be seriously discussing very important issues--or they might be talking about the game.

Published on January 22, 2016 06:40

December 17, 2015

Jackie Brandt: Baseball's Original Flake

Every era has certain players that teammates, opponents and writers love to talk about; the kind of guys who make playing, watching and covering the game fun. In the early 1960s, Jackie Brandt was such a man.

And for etymologists in the crowd (there is always at least one etymologist in every crowd), it's interesting to note that Brandt may have been the inspiration for the word "flakey" entering the modern lexicon. The term is commonly used now, but until the mid-1950s, it was used only by criminals and the drug culture, specifically for someone addicted to cocaine. Wally Moon and Rip Ripulski hung the moniker on Brandt soon after he showed up to the Cardinals' St. Petersburg camp in 1956 because, as Moon later explained, they felt the young Brandt was so wild that his brains were falling out--flaking out of his head. Whether or not Brandt was actually the first to be called that, it is unlikely anyone else earned or appreciated the handle as much as he did. He happily answered to "Flakey" the rest of his career.

Jackie Brandt was a gifted athlete with great speed, a strong arm, a solid bat and the type of physical ability that made everything he did look graceful. He had a fairly good major league career playing for 5 teams over 11 seasons, with his best years coming in Baltimore from 1960-65. He won a Gold Glove in 1959 and was named to the All-Star team in 1961 when he had his best season, hitting .297 with 16 home runs and 72 RBIs.

Brandt's curse was that, although he was a solid player, his natural ability made everyone always expect more. The fact that he glided smoothly across the outfield, eating up yardage while appearing disinterested--without his eyes bulging, head bobbing and hat flying off--made people assume that he wasn't trying, even though he in fact covered much more ground in a shorter period of time than the bulging, bobbing, hatless crowd.

Unrealized potential weighs heavily on athletes and those who attempt to manage them. It was Brandt's bad luck that sports people often compared his tools with those of guys named Kaline, Mantle and Mays. "The trouble is that people have said and other guys have written, that I am supposed to be half of each of them," he explained in a 1964 Sport magazine article. "In the first place, that adds up to one-and-a-half people. In the second, I don't want to be any of them. I would rather be me."

And there was nothing wrong with being Jackie Brandt. It's just that he made certain conservative types a bit nervous. You see, Brandt was, to put it politely, different. He did not conform to normal behavioral patterns. Some said he was a nut. True, he was not like anyone else, but is that necessarily bad? Brandt's mind was as agile as his body. There was always something extra going on between those ears and sometimes he didn't seem to bother with the details. Fans and teammates were never quite sure what he might do next, like the time when, hopelessly caught in a rundown, Brandt did a backflip to attempt to avoid a tag, earning great applause from the crowd but an unsympathetic thumbs up from the umpire.

"You gotta have fun," Brandt frequently told inquiring writers.

A new decade was dawning and attitudes were changing; conformity was on it's way out. No more would it be okay just to be another crew cut, button-downed, cliche-spewing man in a little box. Unfortunately for Jackie Brandt, he arrived just a few years too early. "The Sixties" hadn't really taken hold yet. He was ahead of his time. But he didn't know it. Or care.

Brandt didn't seem to care too much about anything and that was part of his charm. He was perpetually happy; impossible to make mad and as loosey-goosey as they came. His laid-back attitude and general contentment with life were sometimes mistaken for laziness. Writers complained that he played too nonchalantly. Aware of this, one spring he vowed to improve his image: "This year I'm going to play with harder nonchalance."

This was another of Brandt's charms. He was full of witticisms and odd views of the world and he was happy to share them. No writer ever walked away from Brandt with an empty notebook. "The most consistent thing about me is my inconsistency," he once explained to a reporter.

But managers, those stodgy slaves to win-loss records and nonlovers of anything different, often didn't appreciate Brandt's schtick. He was noted to have a special talent for driving managers crazy. This was especially acute when he plied his trade for serious-minded, leather-skinned, old-school hard-liners such as Fred Hutchinson, Paul Richards and Hank Bauer. One afternoon, Brandt wore out batting practice pitcher Charlie Lau, hitting 7 or 8 balls over the left field wall. Bauer, standing at the edge of the cage, growled, "Why don't you do that in a game?"

Brandt smiled and replied, "Put Lau out there in the game and I will." While his teammates broke up around the batting cage, the dour manager did his best imitation of a cigar store wooden Indian. Brandt's name was missing from the line-up card that day.

Brandt was never bothered by incidentals like facts and he had an excuse for everything. Once when he came back to the bench after taking a called third strike with the bases loaded, Richards asked, "What pitch were you guessing? Fastball or curve?"

"Neither," came the answer. "I was guessing ball."

In reply to a Bauer query as to what happened on a misplayed a fly ball, Brandt answered without hesitation, "I lost it in the jet stream."

When confronted by writers that one of his excuses didn't hold water, Brandt unabashedly pleaded innocence: "I said that? My lips must have been sunburned."

Brandt was equally quick-witted among teammates. Once as the team boarded a plane that was late due to bad weather, Brandt asked loudly, "What time is this plane scheduled to crash?" Standing nearby, catcher Clint Courtney, who was deathly afraid of flying anyway, was so unnerved by the comment that he left the airport and took a bus.

Many former teammates recall an expedition organized by Brandt. Tired of the minimal ice cream choices in the team's hotel, he gathered his buddies for a 20-mile drive to a place that offered multiple flavors. Once there, he was apparently overwhelmed with the possibilities and ended up ordering vanilla, causing the angry teammates to threaten to make him walk back.

Even being traded didn't seem to bother Brandt too much. In December of 1965, Brandt and young pitcher Darold Knowles were traded from Baltimore to Philadelphia for pitcher Jack Baldschun. Baldschun was then packaged with Milt Pappas and Harry Simpson to the Reds for an "old-thirty" Frank Robinson. For years, Brandt happily told anyone who would listen that if it weren't for him, the Orioles would have never gotten Robinson and won all those pennants that followed.

After the last game one year, Oriole general manager Lee MacPhail wished Brandt a nice winter. "I always have a nice winter," Flakey replied, "It's the damn summers that kill me."

The 81-year-old Brandt retired to Florida long ago. Here's hoping he has many more nice winters. He certainly made our summers more fun.

Published on December 17, 2015 05:11

December 13, 2015

Philistine Commish Expected to Give Ruling on Goliath Hall of Fame Eligibility Soon

Fans of the former Philistine champion Goliath are anxiously awaiting the promised before-the-end-of-the-year ruling by the new Philistine commissioner on his eligibility for inclusion in the Philistine Hall of Fame. In the past, each new commissioner has steadfastly refused to revisit the case, blindly following the view of the previous regime.

The subject has long been a public relations nightmare for the Hall. Goliath, of course, was once considered to be the mightiest Philistine warrior of all time and many fans remember his enthusiastic pillaging and plundering as the very embodiment of all that Philistia stood for. He was famously quoted as saying that he would walk through Israel in a manna suit just to get on the battlefield. Indeed, if any man deserved to be enshrined on the hallowed walls of the Philistine Hall of Fame it is Goliath of Gath.

It was apparent from the earliest age that Goliath was something special. Inhabitants of his home town recalled that his father, Beelzubub the Belligerent, mercilessly stacked his youth warrior squad and they literally slaughtered all comers. Later, when local officials tried to make more equitable teams, his father pulled him out, aligned him with local youth stars Ashkelon the Big For His Age and Uliat the Held Back For an Extra Year and formed a travel gang that marauded far and wide.

Goliath shot to national prominence in his late teens when a unprecedented growth spurt caused him to swell to giant-sized proportions, gaining two cubits and a span over a period of only three months. Thereafter, he reigned as the undefeated champ until he was upset by the Israelite David in one of the biggest, well, David and Goliath upsets in history.

The fact that Goliath has not been included in the Hall of Fame until this point has long sparked debate and has been extremely disappointing to those who invested heavily in his Topps rookie papyrus, once the most prized piece of memorabilia this side of the Holy Grail. [On a side note, archaeologists have determined that the same batch of bubble gum put in those packs was still being used as late as 1971]. It was originally thought that the crushing defeat to David played the major role in Goliath's exclusion from the Hall, however, recently discovered archaeological documents have shed new light on the subject.

It has become apparent that scribes of the time speculated that Goliath's phenomenal growth spurt did not occur, shall we say, just by living clean and eating unleavened bread. There were wide-spread rumors that his father had arranged for a series of injections which were originally passed off as vitamin B-12, but actually contained anabolic steroids. The suspicion became especially acute when Goliath showed up one spring needing a helmet nearly twice the size of that used the previous fall. And, indeed, one of the problems he had against David was the fact that his head was so large that none of the helmets fit him, leaving his massive forehead exposed as an easy target.

Other scholars point to a more sinister accusation--that of illegal gambling. It had long been suspected that the infamous David match was fixed. Many eyewitness accounts claimed that they did not even see the stone--giving rise to what became known as the "phantom stone theory." It was speculated by some that Goliath was not killed by David at all, but merely took a dive and then was trampled in the ensuing melee as the Israelites stormed the field.

Adding credence to this theory is the discovery of ancient documents which reveal that although Goliath was a prohibitive favorite, local scroll-makers were taking a surprising amount of action on David just before the fight.

Newly damning evidence against Goliath shows up in the recent translation of parchments found among the holdings of Shlomo the Greek, ancient Israel's most notorious gambling kingpin.

Numerous references are found to a "Big G" who placed copious wagers--often on some of the biggest upsets of the time, such as "Big G wants a dime on the Israelites plus 2 and a half over Jerico Sunday" and "One thousand sheckels for Big G on Samsom over Philistines."

One particular inscription states that "Big G may not be good against WLSB this weekend." Biblical scholars now feel that WLSB stands for wimpy little shepherd boy and Big G is indeed Goliath. It is now thought that, despite the fact that gambling on matches by participants was expressly forbidden under Philistine law, "Big G" not only gambled regularly but did so with the other side and ultimately met with a losing streak and found himself heavily in debt to underworld figures, leaving him little recourse but to arrange to throw the fight.

Several ancient Philistine Hall of Famers were quoted in scrolls on the matter. "He should have helped us win the Ark a couple of times but just didn't get it done, now you have to wonder," said one former running mate.

"Everyone knows the rules," said another. "He knew the rules and did it anyway. I hope he never gets in."

As so with these recent findings, Goliath, despite his continued popularity among fans, may have trouble ever getting into the Hall of Fame without a ticket.

Published on December 13, 2015 13:17

December 10, 2015

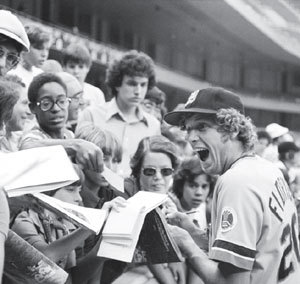

Giving Back, Bird Style: Mark Fidrych's Post-Baseball Years

One of the things that attracted me to the Mark Fidrych story was the way he lived his life after baseball--essentially the same way he lived it before. I found this rather remarkable given the circumstances of his career and how it ended.

Here was a guy who, improbably, became the most famous person in the country in 1976, who lit up baseball stadiums like no one ever had before. His youthful enthusiasm, electric talent and unparalleled natural charisma made him irresistible. He was on the cover of seemingly every magazine that year. For one incredible summer he was on top of the world, loved by fans everywhere.

And then it was over. An injury his second season set off an an agonizing 6-year journey of failed attempted comebacks--done in by a torn rotator cuff.

If anyone ever had cause to be bitter and wallow in self pity, maybe even descend into substance abuse and live a sad, tortured existence after baseball, it was Mark The Bird Fidrych. Since his first season was at the beginning of the free agent era, he never made big money--a year or two later and he could have named his price. Also he played in the days before medical advances that could have diagnosed and maybe even treated his injured arm--a few years later and he could have maybe pitched another 15 years. It should have been enough to drive him mad.

And yet from numerous sources, I learned first hand that he went back to his tiny Massachusetts home town and resumed his life. He remained the same upbeat, incredibly spontaneous, fun-loving, out-going, friendly guy he had always been. He bought a farm and a dump truck and worked for a living. He got married and raised a daughter.

He clearly understood how great his fame had been, yet he remained humble enough that once while working in his mother-in-law's diner--a few feet from a framed cover of Rolling Stone bearing his own smiling mug--in answer to a stranger's inquiry that he looked familiar, he answered, "Well, I used to work at the garage on Main Street."

And he never forgot those who helped him along the way. While busy working for a living, he still found time to lend his fame out for good causes.He regularly showed up on opening day of the local Little League to sign autographs and give inspirational talks to kids. He was active in the nearby Jimmy Fund and Dan Farber Clinic and could always be counted on to show up for charity golf and fishing events. The majority of his charity work involved children, especially those with special needs. "It's called giving back," he told a reporter in 2001. "If I can help a younger kid out that is a great thing to have because people helped me out."

Mark's biggest charitable activity became the Wertz Warriors of Michigan. Baseball fans will recognize the name--before he launched the 1954 World Series drive that made Willie Mays famous, Vic Wertz had been a popular member of the Detroit Tigers and he made the Detroit area his home after baseball. Wertz helped organize the Wertz Warriors in 1982 as a way to fund Michigan Special Olympics. The group uses an annual seven-day, 900-mile cross-country snowmobile ride across the state to provide complete funding for the Michigan State Special Olympics Winter Games.

After Wertz passed away, the group used other former Michigan-area athletes as front men for the fund-raising. Mark Fidrych, through a chance meeting with one of the members, signed on enthusiastically in 1992 and made it for the next 17 straight years. He was the drawing card, giving talks and signing autographs at each stop. Although he was the one everyone showed up to see, he didn't act like a big star. He was one of the guys. He blasted his way through the snow of Northern Michigan with the same enthusiastic abandon he showed on major league mounds. "For me it's the athletes, It's another thing to help out where you can," Mark said.

In talking to members of the Wertz Warriors, it was obvious that they loved the guy.

I recently found some pictures they had given me of Mark on their trips. Unfortunately, there wasn't room in the book to print them all.

Here's wishing every major league baseball player could remain as grounded and happy in retirement as the one and only Bird.

Published on December 10, 2015 06:43

December 6, 2015

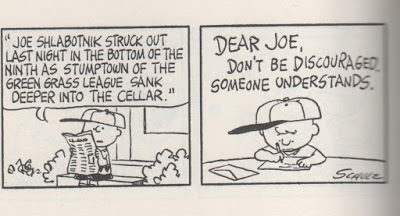

Joe, You Shoulda Made Us Proud: The Disappointing Baseball Career of Joe Shlabotnik

In the annals of baseball history, one name stands tall and resolute when it comes to futility: Joe Shlabotnik. But surprisingly the Joe Shlabotnik story is not one of failure, but of hope, loyalty and endless optimism as seen through the rosy lens of childhood. Shlabotnik's career was saved from the eternal scorn it so richly deserved thanks to the steadfast devotion of his greatest--and possibly only--fan, America's favorite round-headed juvenile baseball aficionado, Charlie Brown.

If idols are, as psychologists would have us believe, a form of identification attachment, Charlie Brown could not have picked a more perfect one. Remarkably fitting for the good-hearted born loser Charlie Brown, Shlabotnik failed spectacularly, and not just on the field. He let Charlie Brown down continually and consistently. But as spectators to the carnage, we somehow understood that no hero is ever as unequivocally infallible as the hero of our youth and Shlabotnik's foibles only made us love him more.

Little is known about Shlabotnik's early years. His last name hints a Slovenian ancestry. He was apparently blessed with enough athletic skill and opportunity that someone (no doubt later driven out of the sporting profession by shame, derision or both) felt that he was deserving of a professional baseball contract. He was signed during the 1950s, before the major league draft; maybe he was courted by numerous scouts and received a bonus, or maybe he was signed as a favor because his uncle was a former player or scout. Whatever the reason, he surely became part of the cautionary tale repeated for years on the perils of scouting and signing young baseball players: "Sometimes your guy turns out to be a Sandy Koufax, sometimes he becomes a Joe Shlabotnik."

In his initial years as a professional Shlabotnik, in the glory of his youthful strength, impressed the front office brass enough with his minor league play that he was eventually promoted to the major leagues. Alas, this is where his story turns sour. For all the promise and potential, Joe Shlabotnik failed to produce at the big league level. It didn't take long for Shlabotnik to establish the fact that he was, in the parlance of baseball men, a no-hit, no-field player.

Shlabotnik was first mentioned as the object of Charlie Brown's idolatry in 1963. He had apparently been in the major leagues for some time because Brown remarked that he had been trying for five years to get a Shlabotnik bubble gum card. Like Shlabotnik's play on the field, Charlie Brown's attempts to obtain memorabilia of his idol--no matter the effort and planning--are doomed to miserable, gut-wrenching failure. In typical Charlie Brown fashion, he spends five dollars on baseball cards (which came in 1 cent packs containing one card and one piece of gum at the time) trying to get a card of his hero. Alas, not one of the 500 packs contained a Shlabotnik. Charlie Brown's female nemesis, Lucy, who couldn't care less about baseball, spends one penny on bubble gum and, naturally, discovers a Joe Shlabotnik card in her pack. Determined to get the card, Charlie Brown offers to trade every card he has for it, offering Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Al Kaline, Stan Musial, Sandy Koufax and others. Lucy steadfastly refuses because she thinks Shlabotnik is "kind of cute." After Charlie Brown leaves in dismay, Lucy tosses the card in the trash and admits, "He's not as cute as I thought he was." This sets the trend for several decades of torture and disappointment, for both Brown and Shlabotnik.

As a baseball player and as an idol Joe Shlabotnik was remarkably consistent. He possessed, as they say, a unique ability to take a good situation and make it impossibly worse. But Charlie Brown was certainly no fair weather fan. He, of all people, understood the frustration and addictive nature of the game of baseball. Charlie Brown never lets reality cause disillusionment with his hero. He is all in, for better or worse. After a game in which Shlabotnik goes 0-for-5 and commits three errors, Brown explains to a friend, "When he suffers, I suffer."

Unfortunately, after too many such games team management finally decides to stick a fork in Joe Shlabotnik's major league career. Brown is incredulous and saddened when he learns of the demotion. "Other kids baseball heroes hit home runs, mine gets sent to the minors," he moans.

Offering much-needed moral support, in a letter to Shlabotnik, Brown writes, "I think it was unfair of them to send you to the minors just because you only got one hit in two hundred and forty times at bat."

Refusing to believe anything but the best for Shlabotnik, when a friend attempts to add psychological analysis and asks if his hero had feet of clay, Brown replies pragmatically, "No, he had a low batting average."

It should be noted that the batting average of .004 still stands as the mark in post-1900 baseball for the lowest batting average in a major league season for a player with more than 200 at bats. And, consistent to the end, the one hit Shlabotnik got that miserable year was a bloop single in the ninth inning with his team leading fifteen to three.

Perhaps because he can understand the struggles of Shlabotnik more than anyone else, Charlie Brown remains faithful. He even starts a Joe Shlabotnik fan club and produces the fan club newsletter which appraised the members of the exploits of their hero: playing for Hillcrest in the Green Grass League, Shlabotnik "batted .143 and made some spectacular catches of routine fly balls. He also threw out a runner who had fallen down between first and second." [Unfortunately the newsletter is stopped after one issue because, as Lucy remarked when asked for comment, "Who needs it?"]

Shlabotnik then threatened to become a Green Grass League lifer. He was traded to Stumptown, where his play continued to stink:

When it finally becomes apparent to management that Joe's playing days are woefully behind him, he is offered the chance to begin on the managerial track. He takes over the reins of the Waffeltown Syrups, a team so deep in the bush leagues that they play their home games in a field near a corner so they can play night games under the street lights.

Alas, Shlabotnik's minor league managing career is short-lived. He finishes with a record of 0-1, fired after the first game because he signaled for a squeeze play with no one on base. Despite the failure, he is touched by the continued devotion of his fan.

Shlabotnik's post-baseball career was similarly disappointing. Unfortunately, Shlabotnik played in the years before players made big bucks. As a guy who was sent down around 1963, he probably never made more than $25,000 a year, maybe even less. He was noted to be working for a time in a car wash.

In later years he tried to cash in on the memorabilia craze but had very little success. While some former major league players were able to command large speaking fees, Shlabotnik's stated going rate was only $100 but, as an old softy, he settled for 50 cents to appear at a Charlie Brown testimonial dinner because that was all the dough the committee could muster (unfortunately, Shlabotnik got lost and never made it to the dinner).

Another time Charlie Brown, Linus and Snoopy paid for tickets to sit at a table with Joe at a sports celebrity dinner, forgoing the opportunity to sit with other sports icons like Willie Mays and Muhammed Ali. Once again, Joe was a no-show as he mistakenly wrote down the wrong event, the wrong day and the wrong city on his planning calendar.

Even though his miserable professional baseball career ended almost fifty years ago, Joe Shlabotnik has not been forgotten. Indeed, the mere mention of the name usually evokes a smile among baseball faithful. Maybe it's because we can all relate to what he went through. Maybe, like us, despite effort, he sometimes couldn't avoid failure. But the failures made his triumphs--like the bloop single--so much sweeter. And he never gave up. Charlie Brown's blind devotion and optimism, tinged with doubts and frustration, are a heart-warming reminder that love should not be based on mere box scores and win-loss records.

So here's to you Joe Shlabotnik, where ever you are. You King of Catastrophe, Pharoah of Failure, Sultan of Snafu, Dauphin of Disappointment. You did your best. To paraphrase the immortal words of Casey Stengel: "We would have given you an award, but we wuz afraid you'd drop it."

Published on December 06, 2015 06:55

November 9, 2015

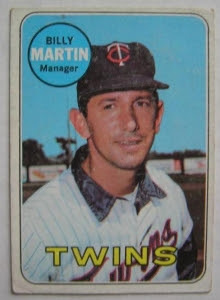

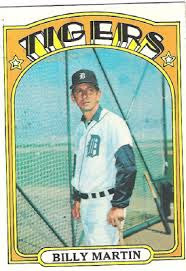

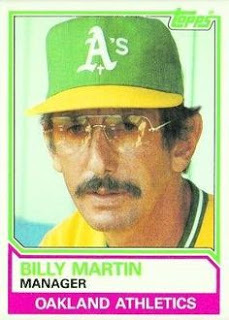

Jump-starting a Baseball Team: Nobody Did it Better Than Billy Martin

As the baseball season recedes and focus turns to next year, a large number of teams will be changing managers, hoping to hit the jackpot. In the past, owners usually resorted to a time-honored formula of following a laid-back player's manager with a fire-breathing tyrant and vice-versa. Often there was a very sad, short list of retread managers who were undoubtedly members of the old-boy network and they simply moved about the league, invariably producing the same results over time. In short, few managerial changes made drastic improvements in a team.

It has often been stated that good players make any manager look good, and there is little a man can do without talent. But there have been a few guys who demonstrated a consistent ability to immediately shake things up. No one did it any better than Billy Martin. Discounting the too-numerous-to-count mid-season dramatics with his buddy George, Billy took over six teams between 1969 and 1983. All of them made predictable jumps in performance. In fact, he never failed.

Below are his results with these teams, with the season immediately preceding Billy followed by his first year:

Record B.A . Runs Steals Sac ERATwins 1968 79-83 .237 562 98 69 2,89 1969 97-65 .268 790 115 65 2.95 Tigers 1970 79-83 .238 666 29 83 4.09 1971 91-71 .254 701 35 62 3.63 Rangers 1973* 57-105 .255 619 91 45 4.64 1974 84-76 .272 640 113 81 3.82

Yankees 1975* 83-77 .264 681 102 54 3.29 1976 97-62 .269 730 163 50 3.19

A's 1979 54-108 .239 573 104 75 4.75 1980 83-79 .259 686 175 99 3.46

Yankees 1982 79-83 .256 709 69 55 3.99 1983 91-71 .273 770 84 37 3.86

* Martin managed the last part of these seasons

Looking closely at the numbers, one is struck by the remarkable predictability of the results. An owner who replaced his manager with Billy Martin could be absolutely certain about several things, virtually without exception: the team would have an increase in batting average, runs, steals, a lower ERA, and, most importantly, an increase in wins (between 12 and 29 games)

And the numbers aren't even close. His new teams averaged an increase in batting average of .017, an increase in stolen bases of 30 (and this includes the lead-footed, veteran-laden Tiger team in which Billy wisely settled for only an increase in 6), a decrease in ERA of 0.48 and an average increase in wins of 18.67.

Surprisingly, while some consider bunting to be a staple of the small-ball Billy preferred, sacrifice bunts only went up an average of 2.2--statistically negligible.

While Billy's long-time pitching coach sidekick, Art Fowler, was sometimes derided as little more than a drinking buddy, it is obvious that the team of Martin-Fowler resulted in dramatic increases in pitching production. Every staff lowered it's ERA (some by as much as 1.29) under Martin except the 1969 Twins, but this must be examined with the understanding that virtually every team had a higher ERA in 1969 compared to the pitching-orgy year of 1968. This is balanced by the fact that modern pitch-count aficionados have criticized Martin for overusing his starters, particularly the young arms on the Oakland staff which turned in the curious stat in 1980 of 94 complete games and only 13 saves and were all out of baseball within a few year (by comparison, in 2015 American League teams averaged 4 complete games and 43 saves).

Some of Billy's reclamation projects were startling, particularly in Texas and Oakland where he took over moribund bottom-feeders and turned them into contenders.

Unfortunately, for both Billy and baseball owners, there was one more thing that everyone could be absolutely certain of; one slightly annoying quid pro quo to the use of his managerial brilliance; a downside to the whole Billy Martin-as-a-team-savior thing. Invariably within two years he would do or say something that would injure or embarrass--or both--a player, an owner, a coach or a marshmallow salesman. That would render all of his on-field heroics moot and he would be shown the door. Such was the Greek tragedy that was the managing legacy of one Alfred M. Pesano, aka Billy "The Kid" Martin.

Published on November 09, 2015 04:56

November 6, 2015

Adam's Rib: The First Surgery

Editor's note: Now that the baseball postseason has concluded I thought it would be good to take a very short respite from baseball and throw up a non-baseball post before the hot-stove campaign begins.

In church recently, mention was made of God removing one of Adam’s ribs to create Eve. It struck me that this was actually the first recorded medical operation. With the recent national debate over health care, I thought it would be interesting to compare that case with modern health care. By all biblical accounts, the procedure went very well. The surgeon was perfect, obviously, and the patient lived to the ripe old age of 930 years. Also, it set the precedent for all future surgeons to think they are God. What is not commonly known, however, is that there were a few minor problems. First, the procedure had to be moved a number of miles to the east, to the land of Nod, because the hospital in Eden did not participate with Adam’s insurance plan. Although the Nod Community Hospital accepted Adam’s plan, the anesthesia group there did not. This is the reason God placed Adam into a deep sleep instead of using general anesthesia.

Initially the insurance company refused to reimburse God for the surgery, claiming it was a pre-existing condition. After numerous phone calls, letters and burning bushes, God was able to convince them that since the Earth was only a few weeks old, it could not have been pre-existing. Then the insurance company denied the claim because the appropriate ICD-1 diagnosis code for "needs a mate" was not used. In God's defense, at the time ICD-1 only consisted of one medical diagnosis: "loss of immortality due to eating forbidden fruit," and that diagnosis had never even been used. The claim was eventually paid—but not without great gnashing of teeth. Unfortunately, God was hit with a hefty fine from OSHA for merely covering the wound with skin and not following accepted guidelines for aseptic technique. And when details of the procedure were printed in the Bible, God was fined again for violating Adam’s HIPAA rights as Adam had not signed a specific waiver consenting to the release of his personal health information.

Later, Adam filed a malpractice lawsuit against God claiming that the preoperative informed consent document should have warned him about the potential risk of his new partner tricking him into eating the forbidden fruit and all the complications which resulted from that. God countered that even He could not have anticipated all the remote complications which were possible. The suit was settled out of court, but God’s malpractice premiums sky-rocketed.

The family practice doctors of Eden were outraged when it was reported that God was reimbursed 30,000 shekels for the case. Actually, He received only 567 (this included a 5% reduction because He didn’t demonstrate meaningful use of electronic health records for the year). In addition, Adam did not pay his portion of the deductible and God was forced to send him to a collection agency.

God was further frustrated when the new Holy of Holies HMO plan restricted direct patient access to Him. When declining reimbursements along with rising overhead and small business taxes made it impossible to continue, God retired from the practice of medicine, even though he was universally regarded as a Great Healer—actually a genuine miracle worker.

It was many years before He came out of retirement for the famous Lazarus case. By then, thing’s were much smoother as the Israelites were covered under Rome’s National Health Plan. Of course, the backlog of cases and rationing of care required Him to wait four days before bringing Lazarus back to life, but that’s another story.

Published on November 06, 2015 15:58

November 1, 2015

Gee, Thanks Brooks: Robinson to Give Away Fortune in Memorabilia

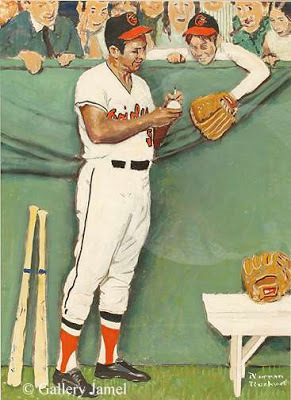

In 1971 Brooks Robinson, fresh off the greatest individual World Series domination in baseball history, visited the Massachusetts studio of Norman Rockwell. It was a classic pairing: the man who chronicled mid-twentieth century Americana on canvas and the man who embodied mid-twentieth century Americana on turf. The setting was commissioned by the ATO corporation, a conglomerate that owned the Rawlings Sporting Goods Company. Brooks had put on a fairly good advertisement for one of their products, a leather glove. The resulting painting by Rockwell was named, "Gee Thanks Brooks" and pictured the Orioles star signing an autograph (left-handed of course) for a star-struck youngster.

When the book Brooks: The Biography of Brooks Robinson came out a few years ago, an occasional complaint was that it overemphasized his legendary niceness. I'll admit that perhaps I should have edited out a few more of the redundant quotes to that effect, but in my defense, I did edit out about a third of them. The problem was that virtually everyone I talked to immediately launched into a story about what a thoughtful/kind/congenial/charitable/big-hearted/down-to-Earth (pick one or more) guy he was and almost all of them mentioned, usually within the first five minutes, that he was the nicest person they ever met or the best teammate they ever had. Also, and quite unusually, almost no one turned down a request to talk about him. They all eagerly contributed their memories--they all wanted to have their say about how much they loved the guy. I'll admit, I was blown away. After a while I felt like interrupting and reminding them, "I didn't ask about Mother Teresa, I asked about Brooks Robinson."

I don't write bubble gum books. My goal is not to make my subject look perfect; it is to explain the personality of the guy, what makes him tick and what makes him unique. And for Brooks Robinson, for better or for worse, that is it in a nutshell--he was a uniquely good guy. It's a totally unusual attribute for a highly successful professional athlete, many of whom have been pampered and given too much leeway throughout their lives because of their extraordinary talent.

Now comes the announcement that Brooks Robinson is unloading almost all the memorabilia from his 20-plus year career for auction. He is not doing this because he needs the dough; doesn't need to divide up the loot to make it easier to split up for ravenous heirs; isn't in any kind of dire financial straits. He and his wife of 55 years are doing quite nicely and they are donating 100% of the proceeds to their charitable foundation.

This is not just a few old broken bats or a mangled jersey. He is including almost everything, including the 1964 American League MVP award, the 1970 World Series MVP award and 16 Gold Gloves. The only thing he is keeping is his Hall of Fame ring--call him selfish. It is estimated that the haul will bring over one million dollars. The original print of the Norman Rockwell, which Brooks purchased at auction for $200,000 in the 1990s and has been loaned out to museums over the years, will be offered in a separate auction and should bring more than the rest of the stuff combined.

Sixteen Gold Gloves? Yeah, with so many of the things laying around, they did get to be a bother, constantly taking up space. Actually this is the second time he's tried giving them away. Over the years he gave Gold Gloves to his brother, his parents, the Boys Club in his hometown of Little Rock and a lawyer who helped him out, among others. As part of his farewell from baseball ceremonies, in 1977 the Rawlings company had 16 new ones recast and presented them to him. He probably thought, "What's a guy gotta do to get rid of these things?"

In recent years we have seen quite a few aging athletes auction off items. But never before has anyone given up his entire collection and donated the whole amount for charity. This is the sort of thing that immediately provokes questions. You know, the "What kind of a . . ." type questions. As in "What kind of a guy just gives away over a million dollars worth of precious pieces of his career?" And also, just as baffling, "What kind of kids did he raise that are okay with him giving it all away and not bestowing it on them?"

One of the very sad things in reading about former sports greats is the fact that frequently the only emotion provoked from so-called loved ones in their declining years is unspeakable avarice. The only thought is in how to exploit the old guy for all they can get. Apparently Brooks Robinson's children do not feel the need to plunder his memorabilia for their own means. Imagine that.

Of course, this doesn't surprise me and I already know the answers to the above questions. You see, in researching my book, I talked to nearly a hundred people. I heard people who went to high school with him tell how he seemed to know everyone in the largest high school in the south, and called them out by name in the halls, from the lowliest freshman to the captain of the football team. I was taken out to dinner in Little Rock by some of his childhood friends and listened as they recounted stories and told how close they have remained over the years and how highly he is still regarded by their classmates after 60 years--as a friend, not as a celebrity. I heard more than one former batboy discuss how Brooks treated them as equals and made them feel as if they were his friends. And I listened to a crusty former manager--once the scourge of umpires all over the league--almost break down and sob as he described an act of kindness from Brooks.

So I'm not surprised at all by this totally unselfish and memorable gesture by Brooks Robinson. As Earl Weaver told me, "Only Brooksie would do that."

Baltimore fans will never realize how lucky they are that their icon has been one of the best guys off the field in sports history. They have never had to worry about scandals distorting their opinion of their idol. He is truly unique among great athletes and is the kind of guy they would be proud to have their children emulate. So they should just smile and say, "Gee, thanks Brooks."

Published on November 01, 2015 05:53

Doug Wilson's Blog

- Doug Wilson's profile

- 43 followers

Doug Wilson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.