Doug Wilson's Blog, page 11

May 17, 2015

The Ken Griffey Jr. Bobblehead

One of the great things about being a parent is that you can rely on the hard-earned lessons of your youth to become a wise-beyond-your-years sage, always knowing the most appropriate, thoughtful ways to deal with each crisis to spare your children the demons and angst you yourself faced as a child. Or so you tell yourself.

And then you actually have kids and it becomes fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants and hang-on-tight. You put out day-to-day fires as they pop up and before you know it, the kids are grown and gone and you realize you never had time to say and teach all the little important things you wanted to. And you just hope that the good stuff somehow soaked through by example.

I was up in my son's room recently. He moved out to start medical school not long ago. Looking at a once-prized shelf of dust-covered, treasured mementos from his childhood--things much too valuable to throw out, but that didn't quite make the cut for a crowded grad-school apartment--I saw a small plastic figure, about two inches tall. It was sitting among several baseballs from long ago games, the significance of a few of them forgotten, a tiny plastic dinosaur which brought great joy when it was won at a grade school carnival, and a small football helmet from his favorite team. The emotional turmoil and pain that this seemingly insignificant little piece of plastic brought my son would be lost to time were it not for the oral history that is passed down, and relished (by his siblings), each year when the kids gather for holidays.

Eerily like my own experience with the Harmon Killebrew 3-D card of my youth (see my post from December, 2014), this one started with great expectation and avarice at the breakfast table. One year, I think it was around 2000, some cereal company put tiny baseball player bobbleheads in their boxes. I didn't pay too much attention, but it was a big deal to the kids. Or I should say, it was a big deal to my middle child, Matt. My oldest son, while remaining a baseball fan, was nearing adolescence and, since the hero of his early childhood (Nolan Ryan) had retired, he no longer had a particular favorite player. My daughter, about five at the time, only would have cared about baseball if the players rode horses while playing.

But Matt, at nine years old, was in the middle of ravenous, all-consuming, baseball fanaticism. Not yet jaded by years of toil and disappointment, he was thrilled when he saw on the cover of the box that the object of his idolization, Ken Griffey, Jr., was included in the players immortalized by the small, very-unlifelike, plastic bobbleheads. He just knew he would get the one he desired.

Not having learned a thing from my own childhood, I announced what I thought was a reasonable plan: the kids would take turns regarding who got the loot from each box. My older son went first and scored a Luis Gonzalez--no big deal. Then Matt's turn came and he got a Mike Piazza. Disappointed, but not devastated, he thought maybe he could last until the next round (not yet comprehending that the boxes with bobbleheads would all be gone a week later). And then in a few days, Stephanie opened her box. You guessed it--a Ken Griffey, Jr.

Matt immediately underwent painful spasms of gnashing of teeth (they actually gnashed, I heard them) as he watched his little sister hold and examine the precious object--the stuff that dreams were made of--with a mixture of barely-controlled rage and jealousy. He was able to pull himself together to come up with a plan, however: she was a little girl, she didn't care about baseball, maybe they could work out a trade. But Matt, who we've warned to never play poker, had already seriously overplayed his hand. Stephanie realized how much her big brother burned with desire to have this innocent-appearing token and she knew that she was very much in a position of power in the negotiations.

"Do you want to trade?" Matt asked, trying to put on his best loving-concerned-big brother face.

"No, I think he's cute," Stephanie replied. Her pigtails swirled as she flicked the tiny tab on the back of Ken Griffey Jr.'s head over and over with her dainty little fingers, making the head bobble. Matt's stomach churned painfully each time Ken Griffey Jr.'s head went up and down. Up and down. Up and down.

Stephanie rebuffed all of Matt's overtures, including, I'm sure, the rights to his first two or three future millions. She continued to torture him with it all week, as if playing with the little bobblehead was the most fun she had ever had. She carried it with her everywhere, continually bobbing the little head while we ate, rode in the car or watched television. All while her big brother's insides slowly turned to mush and he gave up the will to live.

All week, I reminded myself to stay at least a half step between the two of them, lest Matt's pain-twisted mind finally snap and give in to the murderous thoughts and reach for his little sister's neck with sinister intent. Fortunately, some lesson from Sunday School, or maybe threats from his mother, caused Matt to resist the urge and Stephanie lived on.

Finally, when I could take the sight of my son's pitiful suffering no longer, remembering my own pain years earlier, I sat down with my daughter for a serious, and well-rehearsed, heart to heart. "Stephanie, Matt really wants that Ken Griffey Jr. bad, it would be really nice of you if you could trade with him," I began.

"Oh, he can have it," she cut me off as she played with her little plastic horses--resuming her normal routine, as if the whole sordid episode had never occurred.

Amazed that I had convinced her so easily with my wisdom, I just stared.

"Besides," she continued while making her horses gallop, "it's broke. The head doesn't bobble anymore."

Even though it was no longer officially a "bobble" head, Matt was nevertheless ecstatic and relieved beyond all human comprehension when Stephanie presented him with the prize. His suffering was finally over. He immediately installed it next to his other most treasured objects on his shelf of fame.

Where it still sits today.

Published on May 17, 2015 06:19

May 12, 2015

Great Moments in Baseball History: Rabbit Takes Field; Wins Game Single-handedly

The baseball world was stunned in 1946 when a previously unknown jackrabbit from Flatbush entered a game at the Polo Grounds and, while playing all nine positions, simultaneously, defeated the always tough Gashouse Gorillas.

The Gorillas were running away with the game, displaying their powerful offense which included a literally-screaming liner hit into the seats and consistent hitting and base running that resembled a conga line going around the bases.

With the home team trailing 95-0, the rabbit was inserted into the game to stem the tide. The rabbit shutout the Gorillas with his pitching over the rest of the game. Particularly impressive was a single slow pitch that struck out three batters (establishing a new major league record). The rabbit mounted a steady comeback at the plate and pulled ahead by one run. Most old timers agree that his miraculous catch for the final out of a tremendous blast off a bat the size of a tree trunk, in which he took first a cab, then a bus and finally an elevator before climbing the flag pole on top of the Umpire State Building, deserves a place in the top ten greatest defensive plays in baseball history.

After the game, the rabbit voiced what most fans felt about the questionably rule-bending play of the losing team when he said, "The Gashouse Gorillas are a bunch of doity ballplayers."

a

While most observers predicted future stardom for the rabbit after his impressive debut, unfortunately his career fizzled--done in by a rotator cuff injury as well as, it was rumored, being chased out of the clubhouse by his gun-wielding manager who shouted, "Forget baseball, it's wabbit season."

Contacted years later, the manager expressed remorse about his role in possibly causing the rabbit's injury by pitching him too much. "I'm sincerely wegwetful about this," he explained. "Golly, I weally wiked that wascal. We could have wun away with the pennant wace if he hadn't gotten hurt."

The Gorillas were running away with the game, displaying their powerful offense which included a literally-screaming liner hit into the seats and consistent hitting and base running that resembled a conga line going around the bases.

With the home team trailing 95-0, the rabbit was inserted into the game to stem the tide. The rabbit shutout the Gorillas with his pitching over the rest of the game. Particularly impressive was a single slow pitch that struck out three batters (establishing a new major league record). The rabbit mounted a steady comeback at the plate and pulled ahead by one run. Most old timers agree that his miraculous catch for the final out of a tremendous blast off a bat the size of a tree trunk, in which he took first a cab, then a bus and finally an elevator before climbing the flag pole on top of the Umpire State Building, deserves a place in the top ten greatest defensive plays in baseball history.

After the game, the rabbit voiced what most fans felt about the questionably rule-bending play of the losing team when he said, "The Gashouse Gorillas are a bunch of doity ballplayers."

a

While most observers predicted future stardom for the rabbit after his impressive debut, unfortunately his career fizzled--done in by a rotator cuff injury as well as, it was rumored, being chased out of the clubhouse by his gun-wielding manager who shouted, "Forget baseball, it's wabbit season."

Contacted years later, the manager expressed remorse about his role in possibly causing the rabbit's injury by pitching him too much. "I'm sincerely wegwetful about this," he explained. "Golly, I weally wiked that wascal. We could have wun away with the pennant wace if he hadn't gotten hurt."

Published on May 12, 2015 13:45

May 8, 2015

When Ernie Banks Ran For Alderman

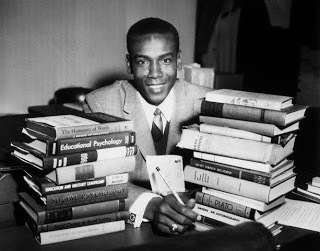

The young candidate woke up early, dressed sharply in a sport coat, white shirt and pencil-thin brown tie, kissed his wife and twin toddlers, then set off walking through the frigid Chicago weather for another day of campaigning. He covered the neighborhood, ringing door bells, shaking hands and handing out literature. He made cold calls on businesses and chatted up school officials, listening to opinions about taxes, juvenile delinquency and the need for local improvements, such as blacktopping a playground or installing a sewer at the corner of 83rd and St. Lawrence. He walked into a crowded pharmacy and introduced himself to the entire establishment. Few people gave him a second thought—just another guy stumping for election, until he introduced himself: “Hello, I’m Ernie Banks. I’d appreciate your support.”

As unlikely as it seems to modern baseball fans, Ernie Banks, who at the time was on the very short list of the best professional baseball players in the land, once ran for Alderman in Chicago, spending virtually all of his time in January and February campaigning. I was reminded of it during the recent primary elections. The episode is worth revisiting because it provides insight into the character and personality of Ernie Banks. The year was 1963 and Banks was 32 years old. It had been almost a decade since Banks had shown up in Chicago as a skinny kid with huge hands, rope-muscled forearms and a lightening-quick wrist power the likes of which had never been seen. His play on the field captured the hearts of Midwestern fans as he copped the MVP award in both 1958 and 1959 and hit more home runs than anyone in the major leagues from 1955 through 1960, clubbing 248 in the six years --more than Mays (214), more than Mantle (236), more than Aaron ( 206), more than Mathews (226 )--an average of 41 a year, unheard of numbers for a shortstop.

While his play for the miserable Cub teams of the era was decidedly spectacular, it was his personality that solidified his place in the psyche of the city Martin Luther King, Jr. once called the most segregated city in the United States. Banks had made an improbable transformation from a painfully shy 22-year old; a kid from a ghetto in rigidly-segregated Dallas, the grandson of slaves, the son of a man who worked odd jobs to raise a family of 11 kids and who taught his kids by example to be wary of white people, to hold their cards close to their chests and never show emotion. But Ernie was his own man and forged his own public personality. He took over Chicago with a unique brand of unfailing optimism and openness. Some people thought it was an act--his schtick--and it might have been, but it was remarkably consistent and the question remains: if you have to come up with an act, what's better than one that puts a smile on people's faces, makes them feel good about themselves and makes you always comes off as a nice guy?

Banks had been known as Mr. Cub for several years. His performance in baseball opened doors and allowed him to rub elbows and meet with important people, and do things that he could never have imagined even a few years earlier. He seemed determined to better himself and to become a factor away from the field. He rarely turned down a speaking invitation, often showing up for kids programs for free.

He took college classes at Northwestern and the University of Chicago several times over the years, taking classes in sociology, psychology and economics, as well as courses in real estate and the insurance business. He was a young man on the move, eternally grateful for the opportunities presented to him, determined to improve himself and make his mark.

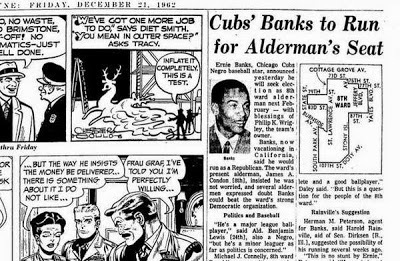

Still, it came as a surprise to the baseball world (and the Chicago political world) when Ernie Banks announced his candidacy for Alderman of Chicago's Eighth Ward on December 20, 1962.

While many former baseball players have had successful political careers, and it was not entirely unheard of at the time for off-duty baseball players to hold positions such as deputy in the off season in small towns back home, this was different. This was the big time--a leading position in the second-largest city in the country. Banks had been contacted while vacationing in California by Harold Rainville, aid to United States Senator Everett Dirkson (R-Ill.) who wanted someone to run as a Republican in the ward against Democratic incumbent James A. Condon. The Republicans soon double-crossed Ernie, however, by throwing their support to another candidate and letting it be known that they hoped Ernie would bow out gracefully (no reason was given for the change of heart). But Ernie, while disappointed to lose Republican support, was not discouraged. He apparently liked the idea of being Alderman and decided to stay in the race, campaigning as an independent. He announced that he had gotten the approval of the Cub brass before deciding. The election was set for February 28, the day before Ernie was scheduled to report for spring training. Owner Phil Wrigley said it was okay as long as the civic duties did not interfere with the baseball ones. "I don't want a part time ballplayer," he told reporters.

The announcement was met with a less-than-enthusiastic response from both the baseball and political worlds and neither could resist mixing corny baseball aphorisms for a laugh at Ernie's expense. John Baspar in the Chicago Daily Calumet said, “Ernie Banks should be right at home as Alderman of the 8th Ward. After all, the Cubs have been wards of around 8th place for some time.”

One wag noted that Banks was certain to win the election if only all of the Cubs’ coaches voted (the joke at the time being that Wrigley, in his disdain for the title "manager" had instituted a much-ridiculed and reviled policy called "the college of coaches" in which a massive rotating team of coaches took turns managing the club).

The Honorable Richard J. Daley, long-term Mayor and Czar of Chicago Democrats, publicly predicted that Banks would finish the alderman race, “Somewhere in left field.”

Flamboyant Alderman Benjamin (aka Duke, aka Big Cat) Lewis of the rough and tumble West Side 24th Ward said of Banks, “He’s a major league ballplayer, but he’s a minor leaguer as far as politics is concerned.”

The fact of the matter was that Ernie Banks was indeed out of his league; and out of his element. Banks' public persona was one in which he always wore a smile, was nice and agreeable to everyone and reflexively avoided all conflicts--not exactly ideal for politics. And this was Chicago politics we're talking about. Politics, as they say, is a dirty business and Chicago was one of the places “they” had in mind when they said this; it can safely be stated that over the years, certain episodes have occurred in the political arena in Chicago that have given citizens cause to wonder aloud whether the whole thing was really on the up and up. Alderman is a position that carries definite power and influence in Chicago--one of fifty men who form the City Council and make decisions for a city of millions. The temptations are numerous--think civic contracts, construction projects, valuable government jobs--and, apparently, more than one Chicago Alderman has attempted to use the powerful position to further his own cause. The first conviction of an alderman for accepting bribes to rig crooked contracts came in 1869. In the years from 1972 to 1999, 26 current or former aldermen convicted of official corruption--essentially one in three of all who served during that time.

And the risks to unwanted candidates were real. Threats, intimidation and even murders were not uncommon for Chicago political wannabes. The above mentioned Lewis, who flaunted an extravagant lifestyle that, according to contemporary reports, was much out of proportion to his known income, was found the morning after the 1963 election in his office, executed gangland style--handcuffed with three close-range bullets fired into the back of his head. It is a crime that remains "unsolved" to this day. Chicago politics--not a business for the faint of heart.

Ernie Banks faced long odds in his bid for election. Independents have a hard time winning elections for county clerk in rural Idaho; they have little chance winning elections against hard political veterans backed by political machines in Chicago. The Eighth Ward had very strong Democratic organization and the incumbent Condon told reporters he was not worried. Condon wasn't worried because he knew a little secret that Banks apparently did not: the odds of a non-Democrat without the express written consent of Mayor Daley winning the election was about the same as the odds of the Cubs winning the Series--that is to say, don't expect it more than maybe once every 100 years or so. But long odds were nothing new to Ernie Banks. Having no chance never stopped him from showing up at the corner of Addison and Sheffield with a huge smile on his face every day of every long, hopeless summer—greeting everyone in sight with his customary, “Welcome to the friendly confines of Wrigley Field,” and later admonishing the guys to play two.

“We’re gonna win it,” Ernie told a visiting reporter. “The Eighth Ward and the pennant.” But his promise sounded about as good as his yearly preposterously optimistic promise of a pennant winner with the dismal Cubs. Ernie explained his belief against long odds: “I believe in P. M. A. Positive Mental Attitude, that’s my theory of life.”

Ernie's campaign headquarters, on South Cottage Grove, displayed a big picture of him in baseball uniform in the window. Above it, a red and blue sign announced, “South Side Committee to Elect Ernie Banks Alderman, Eighth Ward.” Ernie's campaign slogan was "We need a slugger in City Hall." He eventually had a group of 65 volunteers helping him. The son of a local undertaker was his campaign manager (insert your own symbolism here) and promised, "Ernie will be a vocal spokesman for all the people in the ward."

"We need someone with a little independence in this ward," a local businessman told a reporter from the Sporting News. "Someone who doesn't jump every time Daley says something."

Asked if he would have speech writers, Banks said he would not, that he would talk about things he knows. Banks had become an excellent public speaker, making in excess of 50 speeches in recent years mostly appearances to juvenile groups.

The sprawling Eighth Ward contained 93 precincts, with 46,000 registered voters: 45% black, 55 % white. It lay within the so-called "Black belt" of the South Side in which blacks were free to obtain residence and was rapidly changing from white to black. Incumbent Condon was white. Daley's successful strategy in such wards seemed to be to stick with the white Alderman until the ward was nearly 100% black, then make the switch. In general, it was still a good ward, with a majority of homeowners, although in 1962, a small article in Jet magazine had noted that a rear breakfast room window of the Banks house had been broken by a bullet and Ernie's wife Eloise noted that "young toughs" had begun hanging around the "Negro" neighborhood looking for trouble.

Ernie campaigned hard. He averaged about four speeches a day during the two months. His main stated goal was to combat juvenile delinquency. By all indications, Banks was entirely altruistic in his desire for office. He did not appear to be motivated by the potential for monetary gain. He had never lived extravagantly and was currently under contract to the Cubs for $65,000--not as much as Mantle, Mays and Musial, who were $100,000 guys, but firmly entrenched in the second tier of baseball salaries (about as much as Aaron). It was more money than anyone in his family had ever dreamed of. Banks maintained that his political aspirations were not a stunt. He said that he wanted to get into politics in order “to do everything in his power to help youth.”

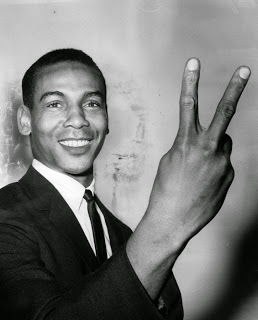

Unfortunately, Ernie had about as much success in politics as he did in his bid to get to a World Series. He came in a distant third in the four-man race, with 2,028 votes. Condon won easily with 9,296, the Republican's man Gerald Gibbons was second with 4264. Coleman Holt, another independent, finished last with 1335. An Associated Press headline February 27, 1963 led with the predictable, “Ernie Banks strikes out in First At Bat in Politics.”

While Ernie initially said he was anxious to try his luck again in 1967, he never did--apparently realizing the obvious.“I learned a lot," he said a little later. "I learned that those professional politicians are a lot tougher than the National League pitchers. Those boys don’t leave much to chance." He had earlier noted, “I don’t understand this political game too well. They try to strike you out before you even get a time at bat.”

Years later, Ernie said, “My timing was a little bit off.” But he added, “I don’t regret doing it.” He remained active in the community, however, and later served on numerous boards including Jackson Park Hospital, Glenwood Home for Boys, Metropolitan YMCA, the Woodlawn Boys Club, Chicago Rehabilitiation Institute and Big Brothers.

In retrospect, perhaps it is for the best that Ernie Banks did not win his election. He was able to maintain his public integrity and popularity, becoming a symbol for cooperativeness and optimism--something that may have been difficult had he won and attempted to serve. He understood that politics is not a game for nice guys and decided to make his mark in other ways.

Published on May 08, 2015 07:07

May 1, 2015

Baseball's Other Fights of the Century

After my last post regarding the fight of the century in baseball, some friends noted that there have been a number of baseball rumbles that could lay claim to the title fight of the century. And why not? It seems that boxing, college football and college basketball have fights or games of the century each week. With that in mind, I searched my memory for some other memorable days when baseball fans went to the ballpark and a hockey game broke out.

Marichal vs. Roseboro, August 22, 1965

One of the most celebrated, and scary, baseball fights occurred during the dog days of 1965 when Giant pitcher Juan Marichal, number 27, took matters into his own hands. The Giants and Dodgers, of course, had a long history of bad blood and the 1965 tight pennant race certainly did nothing to encourage them to play well together. While batting against Sandy Koufax, Marichal felt that catcher Roseboro was intentionally throwing the ball close to his ear when returning it to Koufax. Without a word, Marichal turned and cracked Roseboro over the head with his bat. He landed at least two blows before he was stopped. Roseboro left the game bleeding profusely from a scalp laceration but was otherwise, miraculously, left with no permanent damage. The damage to the psyche of the American baseball fan, however, was considerable. If baseball is, as lyrical wags like to state, a metaphor for American society, the image of Marichal, holding his bat with two hands high in the air, preparing to take another swat at Roseboro's unprotected head, should have scared the hell out of anyone paying attention to what lay ahead for us in the next five years.

Campaneris vs. LaGrow, October 8, 1972

The 1972 A.L. playoff series between the Oakland A's and the Detroit Tigers was a tense affair between two teams led by ultracompetitive managers. Tiger manager Billy Martin felt that Oakland shortstop Bert Campaneris was the key to the A's attack with his pesky base running habits and Campaneris did not disappoint early in the series. In the bottom of the 7th inning of Game 2, as Campaneris came to bat, he had already gotten 3 hits, scored 2 runs and stolen 2 bases in the game. Tiger pitcher Lerin LaGrow promptly nailed Campaneris in the ankle with a pitch. Campaneris, under the impression that the pitch was intentional, got up and hurled the bat at the pitcher. A shocked television nation watched as the projectile helicoptered its way 60 feet, 6 inches toward LaGrow, who ducked out of harm's way. Campaneris and LaGrow were ejected and suspended for the rest of the series.

This one really needs to be seen to be appreciated.

Also interesting is the reaction of Tiger manager Billy Martin who is apparently shocked--shocked--that someone would even suggest that his pitcher would deliberately throw at a batter.

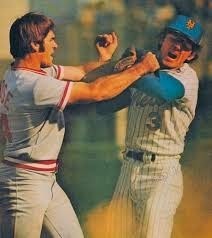

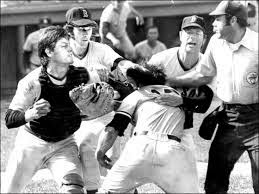

Rose vs. Harrelson, Ocotber 8, 1973

The league championship series frequently brings out the competitive spirit like no other time. The 1973 N.L. playoffs, between the Reds and the You-gotta-believe Mets was no exception. Pete Rose, loved in Cincinnati but viewed with annoyance throughout the rest of the league for his arrogance and annoyingly exuberant play, had just concluded an MVP season. In Game Three, in New York, Rose slid into second base to break up a double play. Actually "slid into second base" is a euphemism for "used his body as a weapon and hurled it in the general direction of the shortstop, Bud Harrelson, who had already stepped on second and pivoted and was about three feet north of the bag." The 150-pound Harrelson objected to the 200-pound Rose recklessly barreling into him and offered a few choice words. Later accounts of the words varied greatly depending on where they were published, but apparently the words referenced either Harrelson's opinion of what Rose did with his mouth or who he had intimate relations with. Whatever the exact exchange, Rose did not take it well and got up and shoved Harrelson. Both benches cleared and a general mob scene followed.

The league championship series frequently brings out the competitive spirit like no other time. The 1973 N.L. playoffs, between the Reds and the You-gotta-believe Mets was no exception. Pete Rose, loved in Cincinnati but viewed with annoyance throughout the rest of the league for his arrogance and annoyingly exuberant play, had just concluded an MVP season. In Game Three, in New York, Rose slid into second base to break up a double play. Actually "slid into second base" is a euphemism for "used his body as a weapon and hurled it in the general direction of the shortstop, Bud Harrelson, who had already stepped on second and pivoted and was about three feet north of the bag." The 150-pound Harrelson objected to the 200-pound Rose recklessly barreling into him and offered a few choice words. Later accounts of the words varied greatly depending on where they were published, but apparently the words referenced either Harrelson's opinion of what Rose did with his mouth or who he had intimate relations with. Whatever the exact exchange, Rose did not take it well and got up and shoved Harrelson. Both benches cleared and a general mob scene followed. After order was restored among the players, manager Sparky Anderson threatened to pull his team from the field as Shea Stadium partisans demonstrated their opinion of Rose by showering him with all manner of refuse when he took his position in the outfield. A peace delegation led by Yogi Berra and Willie Mays made its way to the outfield to plea for calm and the game was finally finished.

Rose got his revenge the next game, hitting a 12th inning home run and sprinting around the bases while defiantly shaking his fist at the Shea Stadium crowd, but the Mets took the series in five.

Ryan vs. Ventura, August 4, 1993

Robin Ventura, who had earlier had an RBI hit, was plunked in the back by Nolan Ryan's first pitch when he faced him in the third inning. Ventura, feeling that the pitch was not an accident, dropped his bat and charged at the 46-year-old pitcher, who appeared shocked that a batter would come out after him. Ryan recovered in time to show the baseball world how Texans punch them dogies when they get out of line.

Robin Ventura, who had earlier had an RBI hit, was plunked in the back by Nolan Ryan's first pitch when he faced him in the third inning. Ventura, feeling that the pitch was not an accident, dropped his bat and charged at the 46-year-old pitcher, who appeared shocked that a batter would come out after him. Ryan recovered in time to show the baseball world how Texans punch them dogies when they get out of line.Mathews vs. Robinson, August 15, 1960

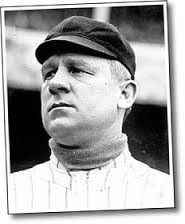

This one is not as well-known now, but it was a big deal when it happened. In the 1950s and 1960s two of the baddest dudes on any field were Frank Robinson of the Reds and Eddie Mathews of the Braves. They were extremely competitive guys who never backed down. Mathews, particularly, had a mean streak and would fight at the drop of a hat--and often dropped the hat himself.

This one is not as well-known now, but it was a big deal when it happened. In the 1950s and 1960s two of the baddest dudes on any field were Frank Robinson of the Reds and Eddie Mathews of the Braves. They were extremely competitive guys who never backed down. Mathews, particularly, had a mean streak and would fight at the drop of a hat--and often dropped the hat himself.Robinson was known to maul more than one baseman with hard, spikes-high slides. When he plowed into third base with a triple and spiked Mathews, the Braves' slugger immediately launched several shots to Robinson's face. While Mathews was ejected, Robinson, bleeding from both his nose and a nasty cut over his eye, stayed in the game. In the second game of the double header, playing with one eye nearly swelled shut and a badly jammed thumb, Robinson hit a 2-run home run and a 2-run double to lead the Reds to a 4-0 victory, prompting a rival coach to say, "Robinson beat the Braves with one eye."

After the game, wearing a face that should have been screaming, "Yo Adrian," a battered-appearing Robinson told reporters, "I won the fight because we won the game."

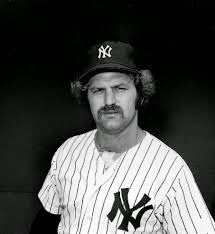

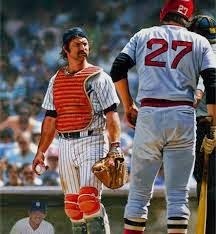

Piniella vs Fisk, May 20, 1976

By the mid-seventies, no one expected a cotillion when the Sox and Yanks got together, but this time they outdid themselves. Lead-footed Sweet Lou Piniella lumbered around third and unwisely tried to score from second on a line drive single to howitzer-armed Dwight Evans in right field. Evans fired a missile and Piniella was out by a mile. Piniella never slowed down, however, and attempted to steamroll Sox catcher Carlton Fisk, who responded by shoving Piniella down and punching him as the two teams raced each other onto the field.

While this one was billed as Piniella vs. Fisk, the undercard of Lee vs. Nettles turned out to be more interesting. Nettles grabbed the Boston lefty from behind, picked him up and body-slammed him to the turf on his left shoulder--fracturing it and knocking him out for the year. Lee, who had inspired Yankee ire after the 1973 fight by saying that they "fought like a bunch of hookers, swinging their purses," got up, realized that his pitching arm was dead and tried to unleash a lethal verbal barrage at Nettles. Perhaps realizing that he could not match words with Lee, Nettles did the only thing he could think of--he slugged him in the face with a haymaker, scoring a second knockdown. Nettles later said, "I wanted to make sure he knew he wasn't being hit by a purse."

Piazza vs. Clemens, October 22, 2000

These two already had a history as Clemens had drilled Piazza in the head during an interleague game earlier in the season, sparking much back and forth banter through the media. When they met for the first time in Game Two of the World Series between the Mets and the Yankees, an inside Clemens pitch shattered Piazza's bat on a foul ball, Clemens picked up the barrel and inexplicably fired it at the startled Piazza. Can you say, "Roid rage?"

These two already had a history as Clemens had drilled Piazza in the head during an interleague game earlier in the season, sparking much back and forth banter through the media. When they met for the first time in Game Two of the World Series between the Mets and the Yankees, an inside Clemens pitch shattered Piazza's bat on a foul ball, Clemens picked up the barrel and inexplicably fired it at the startled Piazza. Can you say, "Roid rage?"Martin vs. Jackson, June 18, 1977

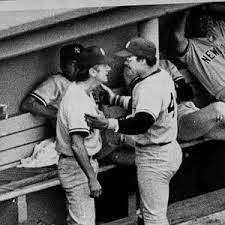

Yankee nerves were wearing thin as the expensive, talented team struggled to put it all together during the summer of '77 while the Bronx was burning. Manager Billy Martin and his star Reggie Jackson butted heads throughout the season. Martin particularly resented Jackson's lackadaisical approach to outfield play. When Jackson appeared to loaf after a blooper by Jim Rice, allowing him to take second, as the Red Sox were drubbing the Yanks in Fenway Park, Martin ordered outfielder Paul Blair to grab a glove and replaced Jackson in the middle of the inning. Jackson, always acutely aware of his image, particularly did not appreciate being shown up on national television. Jackson went directly to Martin in the dugout and the two argued face to face in full view of the television audience.

Yankee nerves were wearing thin as the expensive, talented team struggled to put it all together during the summer of '77 while the Bronx was burning. Manager Billy Martin and his star Reggie Jackson butted heads throughout the season. Martin particularly resented Jackson's lackadaisical approach to outfield play. When Jackson appeared to loaf after a blooper by Jim Rice, allowing him to take second, as the Red Sox were drubbing the Yanks in Fenway Park, Martin ordered outfielder Paul Blair to grab a glove and replaced Jackson in the middle of the inning. Jackson, always acutely aware of his image, particularly did not appreciate being shown up on national television. Jackson went directly to Martin in the dugout and the two argued face to face in full view of the television audience.As everyone knows, the two later made nice (temporarily) and Reggie responded with three home runs in the final game of the World Series that fall.

Martin vs. Boswell, August 6, 1969

Billy Martin, in his first managerial gig, set a tone which would be oft repeated. He immediately turned the team into winners, and very soon afterwards he began to get on people's nerves. And get on people's nerves is a nice way of saying that he beat them up. Dave Boswell was on his way to a 20-win season for the Twins, who would win the A.L. West that season. After a game in Detroit, a few players and Martin were relaxing in a favorite post-game nightspot not far from Tiger Stadium, the Lindell AC. Martin was apparently upset that Boswell had not finished his required running for pitching coach Art Fowler and decided to calmly discuss the matter. They continued their polite discussion out in the alley, where things soon took a turn for the worse. Martin described his version of managerial tough love for an AP reporter, telling him he landed "about five or six punches to the stomach, a couple to the head and when he came off the wall, I hit him again. He was out before he hit the ground." With friends like that, who needs enemies?

Yankees vs. Loudmouth drunks at the Copacabana, May 16, 1957

Even more notorious than Barry Manilow's celebrated Rico vs. Tony fight at New York's Copacabana (the hottest spot north of Havana) was the late-night brawl between several New York Yankees and members of a Manhattan bowling team who had a few too many drinks. One of the loudmouths woke up on the floor of the men's room with a broken jaw. The Yankees involved, not surprisingly, were Hank Bauer, Mickey Mantle, Billy Martin and Whitey Ford. No one ever said for sure who threw the punch, but it was apparently a good one.

Even more notorious than Barry Manilow's celebrated Rico vs. Tony fight at New York's Copacabana (the hottest spot north of Havana) was the late-night brawl between several New York Yankees and members of a Manhattan bowling team who had a few too many drinks. One of the loudmouths woke up on the floor of the men's room with a broken jaw. The Yankees involved, not surprisingly, were Hank Bauer, Mickey Mantle, Billy Martin and Whitey Ford. No one ever said for sure who threw the punch, but it was apparently a good one.The article reporting on the incident in the New York Post which stated, "The great battlefields include Bastogne, Verdun, Gettysburg and the kitchen of the Copacabana," was guilty of hyperbole and inaccuracy (I thought Verdun was overrated). In the aftermath,Yankee owners were so mad at Mickey and Whitey that they traded Billy.

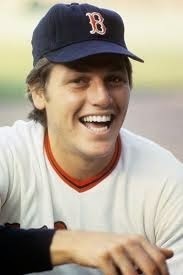

Lonborg vs. Tillotson, June 21, 1967

The Yankee-Red Sox feud had been dormant for years by 1967, but heated up as the Red Sox unexpectedly charged toward the pennant. In a game at Yankee Stadium, New York pitcher Thad Tillotson's first pitch to Joe Foy, who had been swinging a hot bat, was high and very tight. The next pitch clunked him on the head, knocking his batting helmet off. As so often happens in baseball, Tillotson led off an inning later for the Yanks. Gentleman Jim Lonborg, on the mound for the Red Sox, as per the time-honored tradition of protecting his peeps, nailed Tillotson on the shoulder. When Tillotson made some threatening comments regarding what he would do when Lonborg next came to the plate, Foy charged across the infield and the fight was on. Benches cleared, fists flew.

During the melee, Red Sox Rico Petrocelli and Yankee Joe Pepitone, buddies from their early years in Brooklyn, were apparently jawing and joking but were soon swallowed up in the fight. Pepitone, famous for his blow-dried coif, became enraged when someone in the pile pulled his hair.

Another curious sight in the mob scene was the appearance of a New York cop, a member of the special stadium security detail, who joined the fray and was noted to be threatening Yankees. It was later discovered that he was the brother of Petrocelli, who jumped in to protect his sibling.

A Rod vs. Varitek, July 24, 2004

In 2004 Alex Rodriguez was not yet the universally reviled pariah he would become in the next decade. He was simply the most destructive offensive force in the game. With the Yankees leading 3-0 in the top of the third inning, A Rod was drilled in the back by pitcher Bronson Arroyo. An unhappy A Rod exchanged angry words and threats with Arroyo as he slowly walked up the first base line. Lip readers could make out several words that begin with F. Red Sox catcher Jason Varitek apparently heard enough and responded on Arroyo's behalf with a shove to the face which was captured perfectly and for all time in the above photo.

Pedro Martinez vs. Don Zimmer, October 11, 2003

Red Sox-Yankee nastiness had been the norm for years by the time the two teams squared off in the 2003 ALCS. In Game Three, Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez, a man known for his impeccable control, drilled Yankee batter Karin Garcia in the upper back, triggering some spirited yelling and gesturing between Martinez and the Yankee bench, but little else. Yankee bench coach, 72-year-old bald, round-faced cherub Don Zimmer seemed to have the most to say among the penstripers.

Red Sox-Yankee nastiness had been the norm for years by the time the two teams squared off in the 2003 ALCS. In Game Three, Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez, a man known for his impeccable control, drilled Yankee batter Karin Garcia in the upper back, triggering some spirited yelling and gesturing between Martinez and the Yankee bench, but little else. Yankee bench coach, 72-year-old bald, round-faced cherub Don Zimmer seemed to have the most to say among the penstripers.In the bottom of the inning, Yankee pitcher Roger Clemens threw very close to the head of Manny Ramirez. Manny took exception and yelled out to the mound. Clemens stalked toward the plate, yelling choice words of his own. During the exchange of unpleasant words between teams, Pedro seemed to be gesturing at someone on the Yankee bench, saying, "Come at me bro."

Then the gates opened and both teams charged the field. One of the first men into battle was Zimmer, who targeted Martinez. Pedro sidestepped the charging septuagenarian like a bull fighter, grabbed him by the head and hurled him to the ground, thereby instantly becoming Public Enemy Number One in nursing homes throughout the country.

Phillips vs. Molina/Cueto vs. entire Cardinals team, August 10, 2010

The Cardinals had been rubbing their division rivals' noses in the dirt for several years. Instead of answering with his play on the field, Cincinnati's Brandon Phillips offered shots in the media to the effect that the Cardinals were crybabies. When Phillips came to the plate in the first inning of the game in Cincinnati, he tapped Cardinal catcher Yadier Molina on the shinguards with his bat. Molina responded angrily and the bench quickly cleared.This one turned very ugly when Reds pitcher Johnny Cueto, pinned against the backstop by the frenzied mob of players from both teams, began kicking wildly with his metal-cleated shoes. One of his kicks landed on the head of Cardinal back-up catcher Jason LaRue. Cueto was suspended for seven games, but LaRue sustained a concussion, later developed severe post-concussion syndrome and was forced to retire from the game.

So there you have it, my list of baseball's fights of the century. If you feel that I left out a better one, or if you take exception to anything I might have written about one of your favorite players, just throw one high and tight the next time I come up, I'll get the message.

Published on May 01, 2015 12:19

April 29, 2015

The Fight of the Century: Fisk vs. Munson, 1973

Amid all the hype and build-up regarding this week’s “fight of the century,” you’ll have to excuse me if I don't seem too excited. I think I represent all baseball fans as we view it with a condescending, knowing smirk on our faces. You see, we know that this is all artificial: the nasty words being thrown around, the supposed bad blood and, of course, the prefight stare down. Yeah, these guys don’t like each other and for $300 million they’re going to climb into a ring in front of a bunch of rich people and have it out. We're not excited because we remember the fight of the last century. And we know that there was absolutely nothing contrived or artificial about it. That one was real and it was spectacular.

I’m not talking about Clay-Liston, Ali-Frazier, or even Balboa-Crede, I’m talking about Fisk-Munson I, the 1973 version.

While there have been a number of famous brouhahas in baseball, I am partial to Fisk-Munson because of the historical context. You had two great players, closely related by geography, who played the same position, who were both in their prime and who were leaders of their teams; teams which, seemingly since the game was invented, had hated each other--all the ingredients were there.

The New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox had carried a long and distinguished animosity for each other throughout the twentieth century, but the Yankees, as rich, privileged heirs, had always seemed to maintain the upper hand and rubbed the collective New England noses in the infield dirt. It had been one of baseball’s best rivalries, but during the 1960s, it had faded without much fanfare as both teams were rarely good enough at the same time to stir any feelings whatsoever. In 1967 as the Sox were charging to a pennant, a beanball war erupted in Yankee Stadium that resulted in a celebrated brawl, but both teams soon fell into disrepair and the feelings of hate, however welcome, were soon lost.

Enter Mr. Munson and Mr. Fisk. Munson arrived first, a rare combination of athleticism and hitting ability for a catcher. He became the first American League catcher to win the Rookie of the Year Award in 1970 and quickly became acknowledged as the best catcher in the league.

But before Munson could bask in the glow of celebrity, Fisk arrived in Boston in September of 1971. By mid-season 1972, Fisk was beginning to annoy Munson greatly. Not that it was necessarily a bad thing--Munson lived to be annoyed, he thrived on it. He saved up little tidbits of hostility and perceived insults by opponents and used them for motivation, but with Fisk, things quickly elevated to an obsession as he watched the spotlight being stolen.

Fisk was tall with chiseled good looks and, although he played hard, always seemed neat and clean-shaven. Munson was short, squatty, wore a perpetual scowl through a three-day stubble and seemed to always have tobacco juice dribbled on his shirt.

In the days of one nationally televised game a week, on Saturdays, the Red Sox seemed to always appear and announcer Curt Gowdy, a former Red Sox man, continually gushed about Fisk.

Fisk had the audacity to win the Rookie of the Year Award in 1972, the second AL catcher ever (after Munson), along with the Gold Glove and was selected to the All-Star team. That immediately put him at the top of Munson's very long shit list.

Thereafter, Fisk and Munson vied for the title of best catcher, pound for pound, in the league.Both were very proud, very competitive men who had not the slightest inkling to ever back down from a challenge or an opponent.

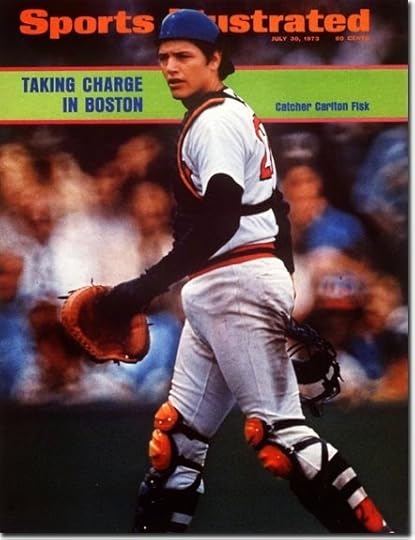

As the Yankees and Red Sox squared off for a series in Boston in August of 1973, a confrontation was inevitable. Only weeks before, Fisk had started the All-Star game--an unfathomable affront that Munson loudly dismissed to anyone who would listen. Fisk had appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated that week, strutting his famously arrogant walk and looking back at the camera in a pose that eerily evoked a Sasquatch.

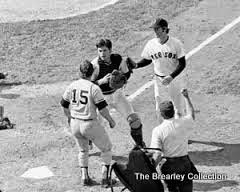

As fate would have it, Munson found himself standing on third base in a tie game, ninety feet away from his increasingly intrusive rival. Munson broke from third with the pitch from lefty John Curtis and Yankee shortstop Gene Michael (aka Stick) squared to bunt—a suicide squeeze. Michael whiffed at the pitch and Munson was hung out to dry. Rather than concede defeat, however, Munson lowered his shoulder and increased to ramming speed.

Michael stood in the way of the play. Fisk roughly elbowed Michael out of the way, straddled the baseline with the ball and held his ground.

The collision left both men sprawled in the dirt.

Fisk jumped up, the ball still held firmly in his hand, and began swinging. All hell broke loose.

Fisk jumped up, the ball still held firmly in his hand, and began swinging. All hell broke loose.

Players from both teams flooded the field and crowded around home plate. While Fisk was squared off with Munson, Michael took several shots at the back of Fisk's head. Fisk then grabbed Michael in a headlock and, while holding Michael firmly with one arm, slugged Munson with the other. They were then buried under both teams. At one point as peace-makers tried to separate the combatants, Yankee manager Ralph Houk slithered through the dirt under the pile with his hands on Fisk’s arm, trying to break the vise-like grip with which he held the scrawny neck of Gene Michael.

In the aftermath of Fisk-Munson I, Red Sox Nation found that they had a new champion, a hero who would stand up to the evil Yankees and never back down. Yankee fans also found something they cherished--a new opponent to despise. Yankee and Red Sox fans knew, without a doubt, that it was on again. It was go time. Baseball fans in general found that there was a new, great rivalry in their midst, something to enliven debates and viewing pleasure for the next decade.

And for Carlton Fisk and Thurman Munson, it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Published on April 29, 2015 09:48

March 7, 2015

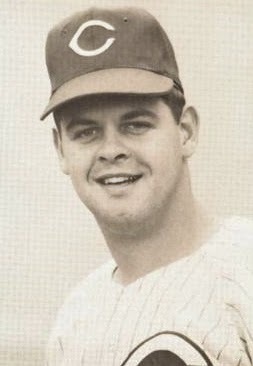

Belated Farewell to Billy McCool

I just found out that former Reds’ pitcher Bill McCool died last summer. He was only 69. Apparently his passing did not make much news outside of his home town. It should have. He was once one of the best young pitchers on the Reds.

When I learned that he had died, my first thought was, “Damn, another nice guy that I interviewed has died.” Bill McCool will always hold a special place in my heart. He was one of the first former major league players I interviewed when I was working on my first book in March of 2009. Had he been rude or uncooperative, I might have tucked my tail and given up on writing books. Instead, he was very accommodating and enjoyed talking about his playing days--and I am waiting for my fourth book to be released this fall.

Bill McCool was a star athlete at Lawrenceburg High School in Indiana, a small border town on the Ohio River only 20 miles from Cincinnati. He signed with the Reds, essentially his hometown team, upon graduation from high school in 1963 and blazed a quick trail through the minors that summer, compiling a 2.01 ERA in 148 innings at Class A Tampa and then going 4-0 with a 1.04 ERA at AAA San Diego in four games.

Bill was barely 19 years old and less than a year out of high school when he unexpectedly (to some) made the Reds coming out of spring training in 1964. Although young, he did not lack for confidence. “I had a pretty good idea I would make the team that year,” he said. “I had a good year in the minors the year before. I knew what I could do.” McCool was a 6’2 lefty with a silky-smooth delivery and a live arm. He had excellent control for a youngster and a classic sneaky-fast heater that developed the reputation of being one of the best fastballs in the league as it tended to tail in on hitters and shatter their bats.

McCool appreciated the the fact that his first manager, Fred Hutchinson, recognized his talent and had a plan to bring him along. “I thought the world of Fred," he said. "He could look mean and gruff and when he said to do something, you didn't bother to ask questions. But he was really a good man to play for. He was fair and you knew where you stood. He was just a no nonsense guy who was well respected by everyone who ever played for him. He knew how to handle people." It didn't take McCool long to find out why Hutch was nicknamed the Bear. "If you lost a close game and he was upset, you didn’t laugh, you didn’t smile, as a matter of fact, you didn’t even want to be in the clubhouse. When he told you to get out of the shower and get out of the clubhouse and on the bus, you didn’t waste time, you did it.”

The Reds of that year were a fairly close team, which helped the rookies fit in. Although the front office leaked to the press that future Hall-of-Famer Frank Robinson was trouble and had attitude problems (feelings that led to the infamous Pappas-for-Robinson trade in 1966 that made world champs of the Orioles), McCool said Robinson was the undisputed leader of the team and a great competitor. “Frank Robinson was just a great guy. He took a lot of us young guys under his wing. When we went into San Francisco, I didn’t know anything, being from a small town in Indiana. Frank called us and said, ‘Come up to my room.’ Me and Sammy Ellis and Mel Queen and a few other guys went in and Frank had called room service and had about 24 hamburgers sent up to the room. We sat in there and talked baseball for four or five hours. Frank was a great guy. He was the team leader.”

Popular veteran lefty Joe Nuxhall was another teammate who made an early impression on the rookie. "Nuxie was another great guy. But you never met a bigger competitor, he hated to lose. Once we walked into the San Francisco clubhouse after a game--he had gotten beat. I think McCovey hit one out late. Joe came in and you could tell he was mad and about to blow. Nobody said anything. He spotted the spread of food in the clubhouse and went to kick the table. He still had his spikes on and his back spike slipped on the concrete and he went flying on his keester. Food went everywhere. I'm at my locker hiding my face, doing everything I can to keep from laughing because he was still so mad." McCool’s first major league appearance came against the Giants. When asked if he was nervous, staring down sluggers like Cepeda, McCovey and Mays as a 19 year old, he replied, “I was never intimidated by anyone. I just went right at them.”

Recalling this line, I had to laugh when I later read the Cincinnati Post account of McCool’s first major league victory, which came in Milwaukee June 2, 1964. In the clubhouse after the game, veteran pitcher Joe Nuxhall laughingly told anyone who would listen that when the peach-fuzzed McCool first came off the field he said, “Boy that Joe Torre scared the hell out of me when he came to the plate. I’ll bet he hasn’t shaved in two weeks.”

The 1964 season became one of drama and tragedy as the Reds battled for the pennant while watching manager Fred Hutchinson fade due to the ravages of lung cancer. The Reds won 10 of 12 late in the season and had a chance to win the pennant on the last day, but lost. McCool was instrumental in the Reds' success that season as he and fellow first-year pitcher Sammy Ellis continually displayed cold-blooded relief pitching in late innings. They formed one of the best righty-lefty bullpen combos in the league. At one point, McCool went ten appearances in July without giving up a run. He finished the season at 6-5 with a 2.42 ERA and 7 saves and was named the National League’s Rookie Pitcher of the Year by the Sporting News.

In 1965, McCool again pitched great, winning 9 games with 21 saves and finished in second place, by one point, for the league’s Fireman Award (an award given by the Sporting News in which saves and wins in relief were added).

In 1966, he made the All-Star team with 8 wins, a 2.48 ERA and 18 saves. He was only 21 years old and his future seemed to hold greatness. But late in 1966, he hurt his knee. “I caught my spikes in the rubber in Pittsburgh and tore some cartilage in my knee,” he said. “Back then, they didn’t want to operate. They tried to medicate it, tried to drain fluid off the knee. I came back, but it totally changed my motion. I'm lefthanded and that was my left knee, my push-off leg. You’re not pitching the way you always have your whole life and you get wild. It started to affect my arm and calcium deposits formed. That was my demise. If it happened today, I would have been back within a month, good as new. But that is just the fortunes of the game. Things happen.”

After struggling for two years, he was left unprotected in the October, 1968 expansion draft and was nabbed by the San Diego Padres. After playing for the miserable expansion team one season, he tried to make it with the Red Sox and Royals but was essentially done at 25 years of age.

After baseball, McCool worked as sports director for a television station in nearby Dayton for two years, then went into the steel business for 31 years until retiring to Florida in 2005. He and his wife had three children and were married 47 years at the time of his death, which was due to long-standing heart problems.

Interestingly, he met his future wife on a blind double date set up by teammate Pete Rose. The Reds were in Milwaukee to play the Braves in 1965 and the future Mrs. McCool was a Marquette coed whose friend had a date for the night with Rose. McCool was drafted as an accomplice. Mrs. McCool later stated that the big-spending Rose (flush with cash as a third-year player making around $20,000) impressed the girls by dropping a 50 cent tip on the table at the end of dinner.

I enjoyed talking to Bill McCool. He was very free with his stories and memories. Before hanging up, however, he made a request which I have not heard since. He asked that I be careful and not write anything that he might have said that might make any teammate look bad. “These guys were all my friends,” he said. “I enjoyed those years on the Reds. We were all friends and had a good time together. We didn't make much money. We played for the love of the game.”

Published on March 07, 2015 08:51

March 3, 2015

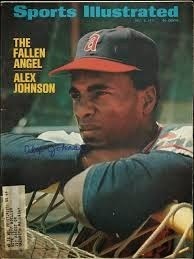

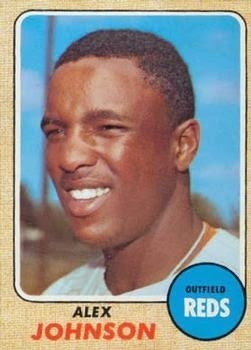

Alex Johnson: A Complicated Baseball Player

Alex Johnson was one of the most enigmatic players in baseball history. He was a supremely gifted athlete when he showed up in major league camp of the Phillies in 1964. He was built like a fullback, at a time when NFL fullbacks carried the ball 250 times a season (his younger brother Ron later became one of Michigan’s greatest running backs and rushed for over 1,000 yards with the New York Giants in 1970 and 1972). Johnson had great speed to go with his size. His Reds manager Dave Bristol swore Johnson was the fastest from home to first of any righthanded batter he had ever seen. And with a bat in his hands, Johnson could absolutely rake.

Managers and GMs couldn’t help but feel that Johnson could do anything on a baseball field he wanted—but therein lay the problem. Sometimes, for some reason, he just didn’t seem to want to do anything. Despite his physical gifts, he was a horrible defensive player, very much earning the nickname “Iron hands.” Not that it bothered him enough to do anything about it. He often skipped or gave less than half-effort in fielding practice. He would end up leading his leagues’ outfielders in errors six times—including a horrific 18 in 1969.

Johnson quickly developed a reputation as moody, unapproachable and aloof. He was labeled as uncoachable. Suggestions from coaches or criticism of his lack of hustle only made matters worse. He would simply shut down.

Johnson also had trouble with teammates. Dick Allen, in his 1989 autobiography had this to say about his former teammate with the Phillies and why he had trouble getting along: he “called everybody ‘dickhead.’ To Alex Johnson, baseball was a whole world of dickheads. Teammates, managers, general managers, owners. Alex would say, ‘How ya doing dickhead?’ Just like that. The front office types would take it personally.” Imagine that.

Few things are more infuriating to coaches than an immensely talented player who appears to waste the talent. Dick Sisler, the Cardinals hitting coach (whose dad George knew a thing or two about hitting), said, “He easily could have become a great Cardinal player, but he showed no interest, even at clubhouse meetings. He doesn’t seem to want to improve. . . We tried everything to bring out his potential.” Both the Phillies and the Cardinals quickly gave up on him.

When Johnson was asked in early 1968, what the Cardinals had tried to change about his hitting, he replied, “You’ll have to ask them. I didn’t pay any attention to what they told me.” That was actually one of his longer quotes. Johnson usually showed an open disdain for reporters. He was not the least bit communicative and frequently gave them the impression that he might snap at any time and commit mayhem with his bare hands. When he was traded to the Reds, a St. Louis writer warned his Cincinnati colleague, “When Alex Johnson says, ‘Mother,’ he has exhausted half of his vocabulary.”

Reds long-time beat reporter Earl Lawson (who was punched out by Reds players Johnny Temple and Vada Pinson in two separate incidents in his early years) later said that Johnson was the only ballplayer he was ever actually scared of. Lawson, on assignment from Sport, asked Johnson in 1968 what Bristol was doing different that helped Johnson have a better year, hoping for at least some compliment for the manager. The reply (“Basically all those mother******s are the same") did not make the article.

As a player, Johnson lucked out when he arrived in Cincinnati before the 1968 season. The Reds’ manager, Dave Bristol, was a classic players’ manager. He figured out that the best way to manage Johnson was to just put him in the lineup and leave him alone. Under Bristol, Johnson flourished. He still led the league’s outfielders in errors in both 1968 and 1969, but he hit .312 in 1968 (one of only six major leaguers to hit .300 in the notorious pitcher's year) and .315 in 1969.

The improvement at the plate led to one of Johnson’s quotes which went down in history, although it may or may not have been as intended. A writer noted early in 1969 that he already had 7 home runs, whereas in 1968 he had hit only two. “What’s the difference?” he was asked.“Five,” Johnson replied straightfaced and walked off.

Although Johnson enjoyed good production at the plate and had few reported problems with Reds teammates, he was traded to the Angels after the 1969 season. The errors played a role, but also the Reds had outfielders Pete Rose and Bobby Tolan, with minor league hotshots Bernie Carbo and Hal McRae coming up, so Johnson was the obvious choice to use as bait for much-needed pitching help. He was traded to the Angels for pitchers Pedro Borbon and Jim McGlothlin.

Johnson proceeded to lead the American League in hitting in 1970 with a .329 average. Things went south in midseason, however, when he was fined by manager Lefty Phillips for loafing. He became worse, and was a serial offender for failing to even make a show of jogging out infield grounders (which, given his great speed, some could have been beaten out). His career rapidly unraveled. He became increasingly erratic, frequently screaming at teammates and media. It was reported that he was despised by virtually all his teammates. He stopped taking outfield practice all together, was benched five times and fined 29 more times before finally being suspended without pay June 26, 1971.

Union boss Marvin Miller had two psychiatrists testify that Johnson had emotional problems in a hearing before an arbitrator. The arbitrator bought Miller’s reasoning and ruled in Johnson’s favor, reinstating $29,000 in back pay and stating that a mental illness should have been treated like a physical illness.

It was never recorded whether or not the players association helped get Johnson psychiatric help after it helped him get back the money. But apparently they did not. He was bounced from the Indians to the Rangers to the Yankees to the Tigers over the next four years, always the same story—periods of great hitting intermingled with exasperating periods of disruption and lack of effort. He never again was the impact player he had been from 1968-70. His major league odyssey included 8 teams in 13 years.

After baseball, Alex Johnson returned to his hometown of Detroit and took over his father’s trucking business. He was apparently a good citizen—there were no reports of run-ins with the police and in the 1990s he gave a very thoughtful and cooperative interview looking back at his career.

By all accounts, Alex Johnson was a complicated man. Few teammates ever really knew him. Maybe it was his fault; his own behavior certainly contributed to his reputation. Maybe he had demons that no one could understand. He was an easy player for teammates, fans and the media to dislike.

Interestingly, in his final season of 1976, playing for his hometown Tigers, he was befriended by an enthusiastic rookie pitcher named Mark Fidrych. The Bird later credited his daily pregame sessions of pepper with Johnson for helping his fielding and helping him go through the entire 1976 season without an error. Johnson also loaned Fidrych some tools and helped him work on his car. Fidrych, who had a unique ability to find the good in everyone and a unique way of expressing his opinion, later said, "You goof around with each player differently. . . I look at him [Johnson] as a baseball player . . . he helped me out . . . I look at the reporters that used to go at him. I'd say, 'Why don't you just leave the guy alone, man?' I don't care what they think. I think he's a good guy. . . If you really sit down with Alex Johnson, Alex is an intelligent man. . . .But he ain't a bad ballplayer at all. That's what's weird, y'know. He hits, when he wants to."

The story of Alex Johnson raises questions. Is a mental health problem the same as a physical health problem for a player, and if so, is the league or team obligated to get the player help? Also is uncoachability or the failure to put forth an effort or get along with teammates (something in which there is unfortunately a long line of offenders) a sign of a mental health problem? Are personality disorders, such as antisocial disorder or oppositional-defiant disorder considered mental health diseases and are teams responsible? Many questions. One can only look at Alex Johnson's batting ability and wonder what if?

Published on March 03, 2015 18:49

February 12, 2015

Little League Founder Sounds Off About Latest Scandal

With the news of the disqualification of the 2014 U.S. Little League champs due to using illegal players, once again last year’s feel-good story is this year’s ethics-challenging scandal. It got me to wondering what Carl Stotz, who founded Little League in 1938, would think of it all. Since Stotz died in 1992, it appeared to be a challenge, but fortunately my last cell phone update came with the Friends and Angels plan and I was able to get in touch with him:

DW: Mr Stotz, thanks for taking your time to talk to me.CS: No problem. Call me Carl. I’m just glad someone down there actually remembers me.DW: How are things going?CS: Great, great. You know the weather is always perfect. Never have a rainout. And we just got Ernie Banks last week. Can’t get that big smile off his face. I bet he’s already said, “Let’s play two” a thousand times. Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply that I would actually bet. That’s not allowed up here you know.DW: The reason I called is to get your opinion of the Little League scandal.CS: Terrible. Just terrible. You know, I never wanted this when we started. I envisioned a program for local competition for all kids. I wanted adults to teach kids about fair play and sportsmanship. DW: That reminds me. I’ve got bad news for you about the Easter Bunny.CS: You’re not one of those guys who’s going to try to tell me he’s not real are you?DW: But back to the scandal.CS: I actually started worrying about the influence of too much commercial enterprise taking away from the kids and our real goals back in the fifties. The Little League World Series was great, but I started getting a bad feeling.DW: Didn’t Howard Cosell do the play-by-play for the first telecast of the Little League World Series in 1953.CS: Yeah, I can’t understand how it got so over-hyped. And that reminds me—Brian Williams did NOT pitch a no-hitter and win the World Series that year like he claims.DW: Maybe he just mis-remembered.CS: Anyway, did you hear that they kicked me out of my own organization in 1955?DW: No.CS: It’s true. I complained too much about the money and potential for corruption. They didn’t want to hear it. I said they were “making the boys pawns in the managers’ dreams.” That’s a quote from fifty years ago. You could look it up. Was I wrong? Now look at it. They have a $10 million dollar annual budget, the TV contract is better than some major league teams had 10 years ago, the tournament lasts through football season, keeping kids out of school. And they have the managers miked during the games so they all try to be Knute Rockne between every pitch. It’s ridiculous. And they wonder why there’s the incentive to cheat. But still, overall it’s a great organization. I’m glad I started it. Just sorry a lot of adults ruin it. You wouldn’t believe how many guys we get every week who say they wish they’d taken the time to teach their kids what was really important when they had a chance, instead of just trying to win every game.DW: That’s sad.CS: I know. They learn too late that the most important thing in a kids’ life is not how he does in a game when he is 12 years old. Listen, it’s been great talking to you, but I gotta go. The kids have practice in a few minutes. Big tournament in Hades this weekend.DW: Good luck.CS: Are you kidding? We’ll need more than luck against those guys. Talk about cheating. Every one of their coaches sold their kids’ immortal soul for 10 more miles per hour on their fastball when they were eleven. And I know for a fact that three of their better players don’t live in their district—they play travel ball year ‘round for a team out of Purgatory. But there’s one more reason why we can never beat them.DW: What’s that?CS: They’ve got all the umpires.

DW: Mr Stotz, thanks for taking your time to talk to me.CS: No problem. Call me Carl. I’m just glad someone down there actually remembers me.DW: How are things going?CS: Great, great. You know the weather is always perfect. Never have a rainout. And we just got Ernie Banks last week. Can’t get that big smile off his face. I bet he’s already said, “Let’s play two” a thousand times. Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply that I would actually bet. That’s not allowed up here you know.DW: The reason I called is to get your opinion of the Little League scandal.CS: Terrible. Just terrible. You know, I never wanted this when we started. I envisioned a program for local competition for all kids. I wanted adults to teach kids about fair play and sportsmanship. DW: That reminds me. I’ve got bad news for you about the Easter Bunny.CS: You’re not one of those guys who’s going to try to tell me he’s not real are you?DW: But back to the scandal.CS: I actually started worrying about the influence of too much commercial enterprise taking away from the kids and our real goals back in the fifties. The Little League World Series was great, but I started getting a bad feeling.DW: Didn’t Howard Cosell do the play-by-play for the first telecast of the Little League World Series in 1953.CS: Yeah, I can’t understand how it got so over-hyped. And that reminds me—Brian Williams did NOT pitch a no-hitter and win the World Series that year like he claims.DW: Maybe he just mis-remembered.CS: Anyway, did you hear that they kicked me out of my own organization in 1955?DW: No.CS: It’s true. I complained too much about the money and potential for corruption. They didn’t want to hear it. I said they were “making the boys pawns in the managers’ dreams.” That’s a quote from fifty years ago. You could look it up. Was I wrong? Now look at it. They have a $10 million dollar annual budget, the TV contract is better than some major league teams had 10 years ago, the tournament lasts through football season, keeping kids out of school. And they have the managers miked during the games so they all try to be Knute Rockne between every pitch. It’s ridiculous. And they wonder why there’s the incentive to cheat. But still, overall it’s a great organization. I’m glad I started it. Just sorry a lot of adults ruin it. You wouldn’t believe how many guys we get every week who say they wish they’d taken the time to teach their kids what was really important when they had a chance, instead of just trying to win every game.DW: That’s sad.CS: I know. They learn too late that the most important thing in a kids’ life is not how he does in a game when he is 12 years old. Listen, it’s been great talking to you, but I gotta go. The kids have practice in a few minutes. Big tournament in Hades this weekend.DW: Good luck.CS: Are you kidding? We’ll need more than luck against those guys. Talk about cheating. Every one of their coaches sold their kids’ immortal soul for 10 more miles per hour on their fastball when they were eleven. And I know for a fact that three of their better players don’t live in their district—they play travel ball year ‘round for a team out of Purgatory. But there’s one more reason why we can never beat them.DW: What’s that?CS: They’ve got all the umpires.

Published on February 12, 2015 05:21

February 3, 2015

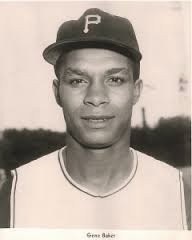

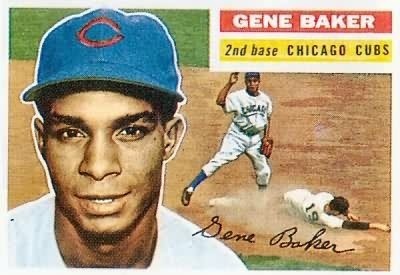

Gene Baker: First African-American Major League Manager

Few things are more annoying than bad baseball trivia—especially when its picked up and repeated by popular media. Since February is Black History Month, I wanted to take this opportunity to correct a misconception and ensure that proper credit is given where its due. Everyone knows that Frank Robinson became the first African-American to manage a major league baseball team full time in 1975. It has been stated erroneously numerous times, however, that Ernie Banks was the first to ever serve in that capacity during a game. Indeed, Ernie Banks, who was a coach for the Cubs, did take over as manager in the 11th inning of a game May 8, 1973 after manager Whitey Lockman was thrown out.

The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide for 1974 even stated, “Ernie Banks became the major league’s first black manager, but only for a day.” An article in Sport magazine in 1988 congratulated Banks regarding the feat and several websites have mentioned it, one in 2013 even interviewed Banks and he admitted that he felt proud of the achievement. This was repeated several times after Banks passed away last month. This is all good, and Banks certainly deserves praise for his optimistic personality and accomplishments during his Hall of Fame career—except that when it comes to this particular achievement, it is completely false.

Ten years before an umpire’s thumb forced Banks into the managerial role for the Cubs, a similar event occurred. The date was September 21, 1963. The Pittsburgh Pirates were facing the Dodgers in Los Angeles. In the 8th inning with the score 2-2, Pirate manager Danny Murtaugh and coach Frank Oceak were tossed by umpire Doug Harvey and the reins were passed to coach Gene Baker. Earlier that summer Baker had become the second African-American to coach at the major league level, trailing the Cubs’ Buck O’Neil by a few months. As Baker led the Pirates, they took a 3-2 lead, then lost on a ninth-inning home run by Willie Davis.

Ten years before an umpire’s thumb forced Banks into the managerial role for the Cubs, a similar event occurred. The date was September 21, 1963. The Pittsburgh Pirates were facing the Dodgers in Los Angeles. In the 8th inning with the score 2-2, Pirate manager Danny Murtaugh and coach Frank Oceak were tossed by umpire Doug Harvey and the reins were passed to coach Gene Baker. Earlier that summer Baker had become the second African-American to coach at the major league level, trailing the Cubs’ Buck O’Neil by a few months. As Baker led the Pirates, they took a 3-2 lead, then lost on a ninth-inning home run by Willie Davis.A small article in that weeks’ Sporting News was titled, “Baker First Negro at Major ‘Helm.’” It stated, “Coach Gene Baker of the Pirates is believed to be the first Negro to ‘manage’ a big league team. He led the Bucs against the Dodgers, September 21, at Los Angeles for the last 2 innings.”

As Buck O’Neil was the only other African-American to have preceded Baker as a major league coach and special “precautions” had been taken by Chicago management to ensure that the circumstances could not have occurred that forced Baker to the role as manager, it can be said with certainty that the title belongs to Baker.

It is perhaps ironic that Banks was remembered for the feat at the expense of Baker. It was not the first time that Banks unwittingly upstaged Baker.

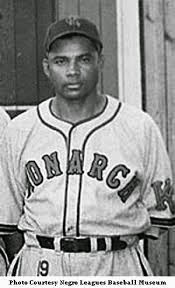

Gene Baker was born in 1925 in Davenport, Iowa. After starring at shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1948 and 1949 (playing the same position for them that Jackie Robinson had a few years earlier), Baker was signed by the Cubs’ organization in 1950, becoming the first African-American signed by the Cubs. Baker was then assigned to the minor leagues where he quickly established himself as a first-rate shortstop. The Cubs, who had the much-maligned Roy Smalley at short, had to defend themselves repeatedly over calls for Baker’s promotion. Smalley's arm was so erratic that the chant at Wrigley Field for double play ground balls hit to second baseman Eddie Miksis (in the manner of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance) was Miksis-to-Smalley-to-Addison Avenue. Wendell Smith (who figured prominently in the recent Jackie Robinson movie) of the Chicago Herald-American and writers for the African-American paper, the Chicago Defender, led the chorus all through the 1953 season as Baker led the AAA Los Angeles Angels with a .282 average, 20 home runs and 99 RBIs while being clearly felt to be the best fielding shortstop in the Pacific Coast League.