Doug Wilson's Blog, page 13

November 8, 2014

Baseball's Pranksters, you gotta love 'em

A key component of every good team is chemistry. The baseball season lasts more than six months--a long time for a collection of 25 guys to spend in close proximity, traveling, playing and hanging out together; 25 competitive, uber-testosteroned guys in various stages of arrested development, struggling to play a difficult game in front of millions, with their results not only printed the next day, but analyzed endlessly on talk shows. In talking with former baseball players, certain names come up frequently when the topic of clubhouse personalities is broached. You can hear the tone change and a genuine chuckle as they recall the antics and pranks. Everyone loves baseball’s pranksters. As fans, we realize that it’s just cool because they can get away with it and we can’t. Imagine a guy getting up to make a presentation in a tense board room and suddenly his suit jacket falls off in shreds, or a surgeon ready to cut open a patient and feeling his foot burning because a nurse crawled over and gave him a hot foot. It’s just not the same.It’s all about timing, the appropriate marriage of personalities, opportunity and atmosphere. Being on a winning team is a must. The ancient Romans clearly understood this and had a saying, “Sic transit gloria mundi,” which roughly translated means: if you give Caesar a hot foot after a victory, you’re regarded as a fun-loving guy who keeps everyone loose, but if you do it after a defeat, you’re lion food. A lot of guys pull the occasional prank, but it takes more than just a sense of humor and imagination to be considered one of the masters. It takes patience, feckless nerves of steel, the diabolical cunning of an evil genius, the audacity of a cat burglar, and a total lack of fear of the inevitable reprisal--no good prank ever goes unrewarded; retribution is swift and brutal. It helps to have a great poker face, the ability to innocently throw up the hands and, with righteous indignation, disavow any knowledge of the caper, all while the entire room knows exactly who the perp is. It also helps, perhaps, to have a lack of social decorum and inhibition.

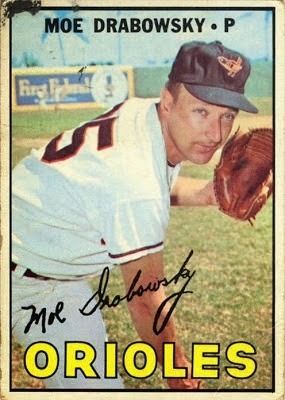

By all accounts, one of the greatest clubhouse pranksters was relief pitcher Moe Drabowsky. His exploits became legendary. He was known to put goldfish in the water cooler of the opposing team’s bullpen and reportedly once put sneezing powder in the air conditioning system of an opponent’s locker room. Possessing a great ability to mimic familiar voices, one spring while he was on the A’s Moe called several teammates and, imitating owner Charlie Finley’s voice, made contract offers to them. He was a master of the hot foot, elevating it to an art form.He hit top form after being picked up by the Baltimore Orioles before their 1966 championship season. While doing research for Brooks, I spoke with Vic Roznovsky. As a backup catcher for the Orioles in 1966 and 1967, Roz spent a lot of time in the bullpen which gave him a closeup view of the master at work. He recalled the game in Kansas City on May 27, 1966 in which Moe officially entered the prankster Hall of Fame. “Moe had remembered the number of the A’s bullpen phone from when he played with them,” said Roznovsky. “Moe could imitate anybody. He called over to their bullpen and, imitating [A’s manager Al] Dark’s voice, he ordered Lew Krausse to get warm. It was only about the third inning and the A’s starter had a shutout going. They thought Dark was crazy, but suddenly you saw guys scramble up and Krausse started throwing.” The real Dark, surprised to see his reliever warming up so early in the game, called his bullpen and yelled, “Sit back down. What’s the matter with you?”“Moe called back two more times,” said Roznovsky, “each time he got Krausse up and then Dark would call back and yell at him to quit throwing. Poor Krausse didn’t know what was going on. We were sitting in our bullpen just cracking up laughing.” After a newspaper article exposed the hoax, the next week Moe called the A’s clubhouse and, pretending to be Charlie Finley, demanded an explanation for the players having been fooled so easily.Moe was infamous for sliding lit firecrackers under the stall door in the clubhouse restroom. “Once in Cleveland, Moe threw a firecracker in the teepee where the Indian was,” said Roznovsky. “You never saw anyone move as fast as when the Indian came running out of there.”For weeks late in the 1966 season, Moe terrorized teammates, especially shortstop Luis Aparicio, with appropriately placed rubber snakes. Then he went for the kill. “We rode together to the stadium and one day he pulled over into a strip mall and ran into a pet store,” said Roznovsky. “He came out and had a snake in a box, it was about two feet long. When we got to the clubhouse, he put it in Aparicio’s shoe and stuffed a sanitary sock in so it wouldn’t get out. I was out on the field warming up and here comes Aparicio flying out of the clubhouse. He was only wearing his underwear. He told [manager Hank] Bauer he wasn’t playing unless he got the snake out of the clubhouse. Bauer had to get somebody to bring Aparicio’s uniform out into the dugout and he dressed there.” No one was safe from Drabowsky, regardless of stature. During the 1970 World Series, he ran a trail of lighter fluid from the trainer’s room to a match slipped into the sole of baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s shoe as he sat in the clubhouse before a game. The trick went off perfectly and a delighted Drabowsky watched the commissioner leap up, dance around and rip his shoe off.

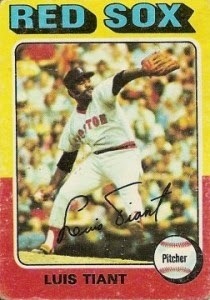

In the Red Sox clubhouse of the 1970s, Luis Tiant was king. With a big cigar (which somehow managed to stay fully lit even in the shower) and a constant running commentary in his high-pitched Cuban accent, he was impossible to ignore. While I talked to utility infielder Buddy Hunter, Rico Petrocelli and Fred Lynn for Pudge they laughed remembering Tiant’s clubhouse act. Tiant’s fertile mind was constantly on the prowl for mischief. He frequently slithered along the ground like a snake to give unsuspecting teammates hot foots while they talked to reporters. No article of clothing was safe in the Red Sox locker room—suits would be shredded, ties cut in half, legs cut off pants, shoes nailed to lockers--everything was fair game. Teammates learned not to savor the hot water in the showers without first checking on the whereabouts of Tiant—they never knew when a bucket of ice water might appear in mid-shower. No one could take themselves too seriously around Tiant. Reggie Smith, who liked to impress with his groovy threads, was a frequent target. “We were in Oakland and Reggie Smith came in with a solid orange polyester jump suit [this was the seventies],” said Hunter. “During batting practice, Luis went in and put it on. It was extremely tight on his body, he had a funny-shaped body anyway, and he had to squeeze to get it zipped up. He put two benches together and walked sideways down the benches; then he put a ball bag around each arm, like a parachute, and jumped off and yelled ‘Geronimo!’ I laughed so hard it brought tears to my eyes.”Outfielder Tommie Harper, who had played with Tiant in Cleveland, joined the Red Sox in the offseason before 1972 in a trade from Milwaukee and was his closest friend. As such, Harper frequently bore the brunt of Tiant’s practical jokes. Once Carl Yastrzemski brought in a prized fish he had caught to show off in the clubhouse. Tiant borrowed the fish, put tongue depressors in its mouth to make it smile, got into Harper’s dressing area and dressed it in Harper’s cap and uniform. When Harper came off the field, the whole clubhouse was waiting see his reaction to a smiling fish wearing his uniform. “LT was just the funniest guy I ever met,” said Lynn. “There’s no way you could sulk or hang your head in that clubhouse, no matter what happened in the game. He could crack you up with just a look.”Yaz enjoyed the pranks more than anyone else. Shortstop Luis Aparicio was famous for his tailor-made suits—a regal, dapper, classy guy. As such, he made an irresistible target. Once Yaz came up behind Aparicio in a bar and tore the whole suit behind the back. “Once during a game, Yaz went back in the clubhouse and took a pair of scissors to Luis Aparicio’s suit,” says Petrocelli. “Aparicio was a great dresser, shark skin suits and all that. And Yaz cut off a sleave of the jacket and taped it on the other side and put it back in his locker. Aparicio comes in, puts on the jacket and the sleave falls off. We were all dying. Aparicio yells, ‘I’ll get you, you son of a bitch.’ Then he did it to Yaz a few days later. But Yaz didn’t care because he wore such bad clothes on the road anyway. He had an old trench coat he wore that must have been 15 years old. We called it the Columbo coat. You couldn’t make his clothes look any worse.”

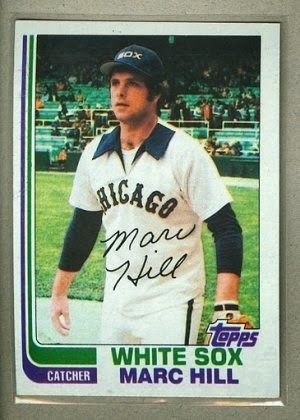

The Chicago White Sox of the early 1980s had one of the masters in Marc (aka Booter) Hill. Hill had been a starting catcher for the Cardinals and Giants before becoming a backup to Carlton Fisk in Chicago. The time on the bench behind Fisk gave Hill time to perfect his craft. After hearing of his prowess from several teammates, I got the chance to talk to Hill for Pudge. Hill’s signature caper was the old shaving-cream-in-the-phone-earpiece trick: “Hey, there’s a phone call for you in the clubhouse,” the unwitting victim picks up the phone and holds it to his ear, and gets an ear full of shaving cream. According to legend, he once got President Jimmy Carter who was visiting the clubhouse. I asked Hill if the story was true, after first assuring him that since the statute of limitations for pranking the leader of the free world had now run out he could come clean. “That’s true,” he said laughing. “He was coming through the clubhouse with a bunch of secret service guys around and I said, ‘Phone for you Mr. President.’ He picked it up. It was funny because he didn’t realize that he had shaving cream in his ear and the secret service guys were dying trying to keep from laughing.”In the dugout between innings, Hill once pilfered third baseman Vance Law’s hat out of his glove, which was sitting on the bench, and replaced it with that of Tom Seaver. Seaver had one of the biggest heads on the team and Law had a very small one (he was referred to in the sensitive vernacular of the clubhouse as a pinner—short for pinhead). The whole team watched the next inning as Law tried to continually pull the hat up and out of his eyes between pitches as it sagged over his ears. On the road, Hill prowled novelty shops and he was especially enamored with little devices that could be stuck into the ends of cigarettes to make them explode. He would find an unguarded pack of cigarettes in the clubhouse, pop one of the babies in and wait for nature to take it’s course. Whenever chain-smoking third base coach Jim Leyland would nervously come off the field between innings and head back down the tunnel for a quick smoke, the entire dugout would go quiet, waiting for the inevitable bang. “Leyland was easy because he would go through a whole pack each game,” said Hill. “You knew it was just a matter of time before he got to the right one. Everybody would listen. Then BANG and you’d hear him yelling down the tunnel, ‘Dammit Booter.’”So here’s a tip of the cap to the great pranksters of days gone by. Some people think that baseball clubhouse pranks don’t seem the same now. Maybe it’s the money, or maybe the game’s more serious. I think they probably still have fun though. There’s always a place for a good prankster. As a little kid wrote in a letter to Moe Drabowsky in 1966 after reading about his gems in the Sporting News, “Baseball needs more nuts like you.” More nuts indeed.

Published on November 08, 2014 08:48

It's All About the Personalities

I’ve been away from here for a while working on books. After sending in the manuscript for my fourth book last month, I thought it would be fun to look back at some of the characters I have interviewed and discussed while doing the research. I’m not really a numbers guy. Yea, numbers are important, but for me the real interest is in the personalities of the players. What were the guys really like? How did the personality of a player, and the mixture of personalities on the team, contribute to their triumphs and failures? And what was it in their early years that contributed to the well-known public personas later? In researching my books, I have interviewed more than 100 former major league players. Some of the best stuff in our conversations never completely made it into the books as they were a bit off topic—those pesky editors are always looking for things to slash. In the next few months I hope to prowl through my notes and post topics of interest.

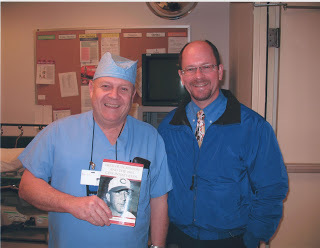

Me and former Astros, Reds and Tigers pitcher Jack Billingham

Published on November 08, 2014 08:07

I’ve been away from here for a while working on bo...

I’ve been away from here for a while working on books. After sending in the manuscript for my fourth book last month, I thought it would be fun to look back at some of the characters I have interviewed and discussed while doing the research. I’m not really a numbers guy. Yea, numbers are important, but for me the real interest is in the personalities of the players. What were the guys really like? How did the personality of a player, and the mixture of personalities on the team, contribute to their triumphs and failures? And what was it in their early years that contributed to the well-known public personas later? In researching my books, I have interviewed more than 100 former major league players. Some of the best stuff in our conversations never completely made it into the books as they were a bit off topic—those pesky editors are always looking for things to slash. In the next few months I hope to prowl through my notes and post topics of interest.

Me and former Astros, Reds and Tigers pitcher Jack Billingham

Published on November 08, 2014 08:07

May 22, 2011

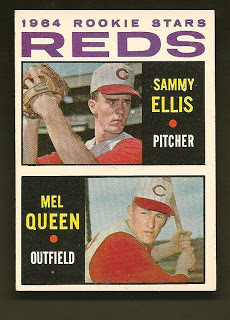

RIP Mel Queen

I find that I am saddened when I learn of the death of someone I haveinterviewed for my books. Whether we talked as little as half an hour or much longer, I am always appreciative of these former players for taking the time to discuss their careers with me. I had the opportunity to interview Mel Queen in 2009 for Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds. Modern fans know Mel Queen, who died last week at 69 due to complications of cancer, as the long-time Blue Jays pitching guru who famously revamped Roy Halladay’s career in 2001, but he was once a very promising outfielder in the Reds system. His rookie season was 1964. Mel Queen was the son of a former major league baseball player, Mel Queen, who pitched for the Yankees and Pirates from 1942-1952. The younger Mel was signed to a large bonus (around $80,000 to $90,000) by the Reds after a stellar high school career in San Luis Obispo, California. Queen was a high school teammate and best friend of future major leaguer Jim Lonborg. He later became Lonborg’s brother-in-law when he married his sister. Coming up through the Reds system, Queen showed some power (93 RBIs at AA Macon in 1962 and 25 homers at AAA San Diego in 1963) and was noted to have one of the best outfield arms in the minors. Because of his bonus and the fact that he was out of options, Queen was kept on the major league roster in 1964 even though the Reds were loaded with outfielders--Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson were All-Star fixtures, second-year man Tommie Harper looked to be a future star and veterans Marty Keough and Hal Skinner provided bench-support. There wasn’t much opportunity for the youngster to get playing time and this would ultimately cause the demise of Queen’s hitting as he could not develop properly while sitting on the bench.

I find that I am saddened when I learn of the death of someone I haveinterviewed for my books. Whether we talked as little as half an hour or much longer, I am always appreciative of these former players for taking the time to discuss their careers with me. I had the opportunity to interview Mel Queen in 2009 for Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds. Modern fans know Mel Queen, who died last week at 69 due to complications of cancer, as the long-time Blue Jays pitching guru who famously revamped Roy Halladay’s career in 2001, but he was once a very promising outfielder in the Reds system. His rookie season was 1964. Mel Queen was the son of a former major league baseball player, Mel Queen, who pitched for the Yankees and Pirates from 1942-1952. The younger Mel was signed to a large bonus (around $80,000 to $90,000) by the Reds after a stellar high school career in San Luis Obispo, California. Queen was a high school teammate and best friend of future major leaguer Jim Lonborg. He later became Lonborg’s brother-in-law when he married his sister. Coming up through the Reds system, Queen showed some power (93 RBIs at AA Macon in 1962 and 25 homers at AAA San Diego in 1963) and was noted to have one of the best outfield arms in the minors. Because of his bonus and the fact that he was out of options, Queen was kept on the major league roster in 1964 even though the Reds were loaded with outfielders--Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson were All-Star fixtures, second-year man Tommie Harper looked to be a future star and veterans Marty Keough and Hal Skinner provided bench-support. There wasn’t much opportunity for the youngster to get playing time and this would ultimately cause the demise of Queen’s hitting as he could not develop properly while sitting on the bench.I missed Mel Queen when I first called, but I explained the book and interview request to his wife who was very pleasant. She said she would give Mel the message. That night, he returned my call and proceeded to talk my ear off. Mel Queen seemed to be the kind of guy who enjoyed telling a good story. He seemed to be the kind of guy who enjoyed telling a bad story. He seemed to be the kind of guy who just plain enjoyed telling stories. I had fun listening to him talk about his trials as a young rookie, his great respect for manager Fred Hutchinson, the personality and struggles to learn English of young Cuban teammate Tony Perez and the clubhouse humor of teammates Chico Ruiz, Joe Nuxhall and Jim Maloney.

He also spoke of the great competitiveness of Frank Robinson, whom he called "The most competitive player I ever saw in the major leagues."“Once, before a game, the other club was still taking batting practice and we were down the line in the outfield,” he said. “I was talking to one of the opposing players who I had known back in California. Frank walked up to me and said, ‘What does it say on the front of your uniform?’ “I said, ‘Cincinnati.’” “And he said, ‘What does it say on the front of that other guy’s uniform?’” “And I said, ‘Cubs.’” “He said, ‘When we are on the field, you don’t talk to them, you don’t socialize with them, they are the enemy. After the game, out of uniform, you can do whatever you want, but on the field, they’re the enemy.’” “Later in the early seventies,” Queen continued, “when Frank was with Baltimore and I was with the Angels, I was walking down the line after BP and Frank came up behind me and said, kind of low, ‘Hey Queenie, how’re you doing?’ “And I said, ‘Hey Frank, how are you?’ And we kept walking. If you were watching from the stands you wouldn’t have known we said anything.” (Baseball on-field czar Joe Torre would appreciate this story in view of his recent complaints of fraternizing between opponents).

Queen spoke with appreciation of the compassion manager Hutchinson showed the lowly rookie who made a clubhouse faux pas while being hungry after a tough double header loss. The two losses came on July 12 to the Mets in New York, with the Reds scoring only one run the whole day off the lowly Mets pitching staff. Fred Hutchinson hated dropping games to the Mets, and it provoked one more appearance by The Bear of old. “We went into the clubhouse after the game and all the players were sitting at their locker,” remembered Queen. “I was a stupid, naïve rookie. There was a spread of food on a table for after the game. I went up and started making myself a plate. Fred came in, kind of looked at me, then walked by into his office. So I finished making my plate and went over to my locker, not noticing that no one else was eating. He came back out and cleared the whole spread with one swipe of his big arm. ‘I don’t want anybody in here eating,’ he said. ‘There better not be a player in this clubhouse when I come out of my office after I shower.’ All of the sudden you’ve got guys like Pinson, Robinson and Rose flying through their lockers getting out of there. Nobody wanted to take a chance on being caught when he came out. He had seen me and knew I was a rookie and didn’t know any better. So instead of saying something there to embarrass me in front of the whole club, he walked on by and let me get back to my locker, then came back out and had his tirade. I really respected him for that because he could have embarrassed me greatly but he chose not to, knowing I was a rookie.”

While not getting off the bench much in 1964, Queen did have a few bright moments:Against Houston, July 14, the second game of a double header was notable for the first major league home run off the bat of rookie Mel Queen. The seventh-inning blast put the Reds in front 10-3 and loosened up the Reds bench. When Queen came back to the dugout he witnessed Marty Keough stretched out on his back, apparently fainted from shock. Backup catcher Hal Smith was fanning him with a towel while Joe Nuxhall was administering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. “We just had to acknowledge the first one,” a laughing Keough told reporters after the game. “Queenie was so excited the second time he went to the plate that he was going to use the lead bat we use for warm-up swings in the on-deck circle,” Pete Rose joked.

Queen pinch hit a seventh-inning three-run home run off Bob Gibson on August 1 to rally the Reds from a 3-1 deficit and September 2 had a twelfth-inning pinch single to plate the winning run in a 1-0 win over Chicago.

Unfortunately, Queen’s skills atrophied sitting on the bench in the mid-sixties as the Reds first played power-hitting Deron Johnson in the outfield and then moved Pete Rose there, in addition to bringing in hard-hitting Alex Johnson and Art Shamsky, leaving him little opportunity in the field. After mopping up from the mound a few games late in 1966, Queen switched positions and became a full-time pitcher in 1967—having never pitched in the minor leagues. While several players have switched from pitching to fulltime playing, Queen became the only successful pitcher to have been switched the other way while in the major leagues in the past fifty years. And he pitched brilliantly, going 14-8 with a 2.76 ERA that season. The 1967 season was to be the pinnacle of Mel Queen's career, however, as arm troubles limited his effectiveness over the next five years. Thereafter, he embarked on a coaching career which lasted until recently when he was no longer physically able to show up on the field due to his illness. It is perhaps with a touch of irony that Mel Queen spoke to me in 2009 with such sadness and respect for the way that his manager Fred Hutchinson had faced cancer--the very disease which he would himself face in the very near future.

Published on May 22, 2011 13:17

April 23, 2011

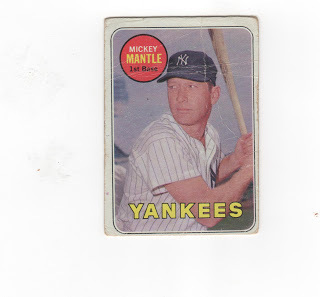

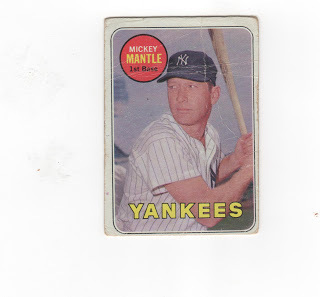

The Mickey Mantle Baseball Cards

Growing up in the sixties, baseball cards held a hallowed place in our hearts. Other than the occasional Saturday Game of the Week, it was the closest chance we had to actually see our heroes. Each year, there was an unspoken contest to be the first in the neighborhood to get the new year's cards. We couldn't wait to see what the design was, what jokes or little factoids were on the back, and what pose our favorite players had. There was an incredible joy in opening the waxy packs, smelling the sweet chalky aroma of the bubble gum and finding out who we had gotten. There was nothing like the feeling of our aching jaws as we tried to meld that tenth piece of the brittle foul-tasting bubble gum into the wad which stretched our aching jaws to the limit. There was nothing like the ecstatic squeals from our bubble-gum loaded mouths as we discovered a Mays or an Aaron in that last pack.

We didn't need no stinking price guides to tell us what our cards were worth. We didn't know and didn't care about rookie cards or limited runs. Mint condition was something that made your breath smell good. The only thing that mattered to us was the man on the front of the card. We all knew that a Bob Gibson was worth more than a Juan Pizarro, a Harmon Killebrew was worth more than a Rich Reese, a Mickey Mantle was worth more than anybody and two Mickey Mantles were worth more than any punishment known to western civilization.

Back then cards came ten in a pack (plus an insert of a game card, poster or coin) for a dime. For a few hours work riding our bikes around collecting Coke bottles for the two cent refund, we could get quite a few cards. It wasn't always easy to find cards though. Frequently the food stores, dime stores and gas stations only bought a few boxes--and there were always jokers around who bragged about "buying out" the stores. The most reliable place for us to score some cards was a 7-11 store which, unfortunately, lay on the other side of a four-lane road which we were forbidden to cross without adult assistance.

One fateful day in 1969 my brother and I heard from a guy who knew a guy who said that there were only a few cards left at the 7-11. With ready cash burning holes in our pockets, we decided that we could not simply wait for it to be sold out and we decided to sneak over there. To our amazing good luck, our haul included two Mickey Mantles! The Mick, the All-Time World Series Home Run Leader himself, the last remaining link to the great Yankee dynasties--to the time when giants roamed the Earth (or at least roamed New York). He had already announced his retirement and we knew this was the last baseball card he would ever have. To a kid in 1969 this was like finding the Hope diamond in a box of Cracker Jacks.

With a sibling cooperativeness usually reserved only for snooping for Christmas presents, my brother and I quickly agreed to divvy up the loot fairly (one Mantle each), hid the cards in the garage, put on our best poker faces and marched into the house. We were amazed to find out that we were already busted. Somehow my mom was always one step ahead of us. Later we discovered that our neighborhood held an elaborate network of mother-spies which would have put the CIA to shame--kids in that neighborhood never had a chance--and someone had seen us crossing the road and ratted us out.

My mom confiscated our treasure and put it on top of the refrigerator, announcing that we would be lucky to get them back before winter. We were semi-celebrities at school that week as news of our great fortune spread quickly. Along with the notoriety, however, came scoffs from wise guys who doubted our story and said that since we couldn't produce the evidence, we must be lying. Finally after an eternity (one week) of torture, my mother, understanding the gravity of the situation, commuted the sentence and the cards were ours.

I don't know what happened to my brother's Mickey Mantle card, but I know what happened to mine--I still have it. According to Beckett's Price Guide grading scale, the rounded corners and numerous creases the card sustained as it went to school in my back pocket every day that week 42 years ago make it virtually worthless now. But, like I said, we never needed no stinking price guides to tell us what our cards were worth.

We didn't need no stinking price guides to tell us what our cards were worth. We didn't know and didn't care about rookie cards or limited runs. Mint condition was something that made your breath smell good. The only thing that mattered to us was the man on the front of the card. We all knew that a Bob Gibson was worth more than a Juan Pizarro, a Harmon Killebrew was worth more than a Rich Reese, a Mickey Mantle was worth more than anybody and two Mickey Mantles were worth more than any punishment known to western civilization.

Back then cards came ten in a pack (plus an insert of a game card, poster or coin) for a dime. For a few hours work riding our bikes around collecting Coke bottles for the two cent refund, we could get quite a few cards. It wasn't always easy to find cards though. Frequently the food stores, dime stores and gas stations only bought a few boxes--and there were always jokers around who bragged about "buying out" the stores. The most reliable place for us to score some cards was a 7-11 store which, unfortunately, lay on the other side of a four-lane road which we were forbidden to cross without adult assistance.

One fateful day in 1969 my brother and I heard from a guy who knew a guy who said that there were only a few cards left at the 7-11. With ready cash burning holes in our pockets, we decided that we could not simply wait for it to be sold out and we decided to sneak over there. To our amazing good luck, our haul included two Mickey Mantles! The Mick, the All-Time World Series Home Run Leader himself, the last remaining link to the great Yankee dynasties--to the time when giants roamed the Earth (or at least roamed New York). He had already announced his retirement and we knew this was the last baseball card he would ever have. To a kid in 1969 this was like finding the Hope diamond in a box of Cracker Jacks.

With a sibling cooperativeness usually reserved only for snooping for Christmas presents, my brother and I quickly agreed to divvy up the loot fairly (one Mantle each), hid the cards in the garage, put on our best poker faces and marched into the house. We were amazed to find out that we were already busted. Somehow my mom was always one step ahead of us. Later we discovered that our neighborhood held an elaborate network of mother-spies which would have put the CIA to shame--kids in that neighborhood never had a chance--and someone had seen us crossing the road and ratted us out.

My mom confiscated our treasure and put it on top of the refrigerator, announcing that we would be lucky to get them back before winter. We were semi-celebrities at school that week as news of our great fortune spread quickly. Along with the notoriety, however, came scoffs from wise guys who doubted our story and said that since we couldn't produce the evidence, we must be lying. Finally after an eternity (one week) of torture, my mother, understanding the gravity of the situation, commuted the sentence and the cards were ours.

I don't know what happened to my brother's Mickey Mantle card, but I know what happened to mine--I still have it. According to Beckett's Price Guide grading scale, the rounded corners and numerous creases the card sustained as it went to school in my back pocket every day that week 42 years ago make it virtually worthless now. But, like I said, we never needed no stinking price guides to tell us what our cards were worth.

Published on April 23, 2011 08:28

April 2, 2011

Bench me or trade me: remembering Chico Ruiz

Chico Ruiz was one of the more colorful characters and popular members of the Reds in the 1960s. When 25 year old Hiraldo Sablon Ruiz, known to all as Chico, joined the club in spring 1964, he had several very good years in the minors behind him and was ready for the majors. He grew up in Santo Domingo, Cuba where his father operated a cigar factory. Chico and teammate Tony Perez were part of the last of the wave of great players to come from Cuba before Fidel Castro shut down the pipeline. In the fifties the Reds had a great thing going in Cuba. Reds’ general manager Gabe Paul was good friends with the owner of the Havana club and the Reds actually made Havana a triple-A team a few years. Baseball had been introduced to Cuba in the early 1900s and the island had a great baseball tradition, more than any other Caribbean country at the time. Ruiz told reporters in early 1964, “Where I live in Cuba, if baby is boy, his first gift is always a bat.” The Reds occasionally took spring training trips to Havana in the fifties. The Reds got first shot at a large number of great players thanks to their relationships on the island. In addition to Ruiz, Cardenas and Perez, other players such as Mike Cuellar, Tony Gonzalez and Cookie Rojas--players who had long successful careers in the majors--were brought in and traded. Unfortunately, soon after taking power Castro decided to favor the Communist Reds over the Reds from Cincinnati and he put an end to baseball players leaving the island for the major leagues. The early days of the Castro uprising had centered in Ruiz’s native area of Santo Domingo and had closed the secondary school he was attending. Ruiz’s father had opposed Chico signing a baseball contract which would take him to the United States. His father’s fears were confirmed as, once the Castro government had been established, Chico, like other Cubans playing major league baseball, could not visit his home because of the uncertainty of being allowed to leave to return to the United States. It would be years before Chico saw some members of his family again.Chico was popular with his teammates on the Reds. He was always smiling and bubbly--a happy-go-lucky kind of guy. He was proud of the control he had gained of the English language through hard work, without any educational assistance, and he mixed well with his teammates. “Everybody liked Chico,” says Sammy Ellis.“Chico Ruiz was extremely funny,” says Mel Queen. “He was always joking.” One of the characters on the team, he kept teammates laughing. One season, he spent his idle time in the dugout making a huge ball of bubble gum wrappers. He became renowned for the alligator shoes he bought and fit with spikes. “When we were going to be on the Saturday Game of the Week on TV,” adds Queen, “Chico would wear his alligator shoes and sit in the front part of the dugout with his feet up so everybody on TV could see them.”Ruiz was once spotted on the bench with his own personal cushion and a battery-operated portable fan. “If you’re going to sit on the bench, why not be comfortable?” he said. He loved practical jokes, once slicing a teammate’s sports jacket into shreds and then sewing it back together loosely so that it fell apart as soon as it was put on. While Ruiz had blazing speed, he was not near the all-around player Cardenas was and could not beat him out at shortstop. Although the switch hitter had a good batting average in the minors, he was never able to hit much more than .250 in the majors. But he was a very valuable player to have on a team because of his disposition and because he could play, better than adequately, every position on the field except pitcher and catcher. He started at third base early in 1964, however Steve Boros won the job after the first few weeks. Starting or not, Chico’s attitude was the same. Later in his career, as a utility infield-lifer, he was forced by injuries to others to be in the starting lineup for several weeks in a row. He came into the dugout after a game, slammed his glove on the bench, complained that playing every day was killing him and jokingly yelled the immortal phrase, “Bench me or trade me.”Late in spring training of 1964, Earl Lawson had run a column discussing the great speed of Chico Ruiz, who had led the league in stolen bases every year in the minors from 1959 through 1963. Three times in his career, he had gotten doubles on bunts and once had reportedly gotten a triple on an infield popup. “God give me speed,” Chico told Lawson, “I got to use it.”Lawson quoted coach Regie Otero as saying, “If Chico make team, we be the terrors of the National League. . . we drive pitchers crazy.” Lawson and Otero did not know at the time that six months later their words would seem like prophecy. That prophecy would come true on September 21, 1964. The Reds were in Philadelphia to take on the Phillies who were seemingly in command of first place--a six and a half game lead with twelve games left to play. In the top of the sixth inning of the scoreless game, Chico found himself on third base with two outs. Frank Robinson stepped into the batter’s box. After a great month of August, Robinson had remained hot in September, his batting average now over .300. Robinson menacingly took his familiar stance, head bent, elbow leaning over the plate, daring the pitcher to give him anything close. Phillies pitcher Art Mahaffey peered in for the sign. He knew he would have to be careful with Robinson. With first base open, there was no need to give him a good pitch, but the next batter, Deron Johnson, had also been hitting well and so Mahaffey didn’t want to intentionally put Robinson on. The righthanded Mahaffey slowly went into his wind up and fired a fastball which Robinson took a vicious swing at and missed.Leading off third, Chico Ruiz watched the windup and pitch. Had Mahaffey checked him or was he focusing only on the dangerous batter at the plate? Ruiz looked at Mahaffey, then looked at homeplate, then back at Mahaffey. As the pitcher lifted his left foot to bring it back to start his wind up Ruiz . . . took off! Out of the periphery of his vision, Mahaffey detected movement in a place where his brain quickly registered no movement should be. Having already committed to his windup, Mahaffey could not break off and simply throw the ball home for fear of committing a balk. Was it a bluff, a steal or a squeeze bunt? Why would they squeeze with two outs? Why would they steal or squeeze with Robinson at the plate? With two outs?! Mahaffey’s brain quickly tried to process the information in a fraction of a second while completing his windup as 20,000 screaming fans, along with the players and coaches from both teams reached the astonishing conclusion at the same time: he’s trying to steal home!! Robinson also noticed movement out of the corner of his eye and sort of half turned as if to bunt and stuck his bat out. “I did what I could to protect him,” he later told reporters. A pitcher’s normal response to a squeeze or steal of home is to throw the pitch either at the batter to force him to get out of the way or to throw it outside where it can’t be reached with a bunt attempt. Perhaps Mahaffey’s brain quickly ruled out throwing inside due to the standing order from Mauch not to ever throw inside to Robinson. Perhaps he just threw it as fast as he could. The ball reached home in time to get the streaking Ruiz, but it sailed too high and outside. Catcher Clay Dalrymple jumped but couldn’t reach it. Ruiz scored. A steal of home is one of the rarest plays in baseball. Most are part of a double steal with a man on first and third. A straight steal from third is an almost impossible task off a major league pitcher. The baserunner is betting he can sprint almost ninety feet faster than the pitcher can throw a ball sixty feet. Most managers tend to discourage taking such chances. Ruiz had taken this chance entirely on his own. Indeed, perhaps the most surprised person in the park to see him running was acting-manager Dick Sisler. When Ruiz broke for home, Sisler jumped up screaming, “No, No!” To take a chance like that, in that situation, at that stage of the season was mind-boggling. And for a rookie to risk laying there at homeplate, being tagged with the third out and looking up at the unhappy face of Frank Robinson, standing there holding a baseball bat, defies comprehension. “Chico Ruiz was a smart player who wasn’t afraid to take a chance,” says Billy McCool. “Of course, if Frank had gotten a good pitch and turned on it, Chico would have died a whole lot sooner.”“If he had been out they would have shot him,” says Ellis.“It was about the dumbest play I’ve ever seen,” Rose said years later, “except that it worked.” Reds pitcher John Tsitouris blanked the Phillies the rest of the way, striking out the final batter with a man on third, and the Reds won, 1-0. After the game in the Reds clubhouse, a jubilant Ruiz told reporters, “I was hoping I would be safe because I didn’t want to hear what the manager would say if I was out.” “On the first pitch to Robby, Mahaffey only look at me once and then went into a slow windup,” Ruiz explained. “He did the same thing on the second pitch and I run.” Ruiz admitted that he had stolen home a few times in the minors but had never attempted it in the majors. “I don’t think I try again,” he laughed, “I keep my record perfect.” “I didn’t give Ruiz the steal sign,” Sisler told reporters. Then, stating the obvious, added “with Robby up there at the plate, I’d rather gamble on him hitting than Ruiz stealing.”“When I saw Ruiz start running I just went blank,” said third base coach Regie Otero. “I couldn’t say anything.”Phillies manager Gene Mauch certainly could say something. In the clubhouse he was beside himself. “Who the f--- is Chico Ruiz?” he screamed to no one in particular, “If he had been thrown out he would be sent back to the minors where he belongs.” The play had defied logic. It was an affront to all that Mauch believed in. To lose a game on a play like that, by an unknown player like that, was more than he could stand.“Chico F---ing Ruiz! Chico F---ing Ruiz!” he screamed over and over at his demoralized team. “I can’t believe it. You guys let Chico F---ing Ruiz beat you.” The Phillies had reached their highwater mark. They would never recover.

The Phillies promptly went on an epic losing streak. That, coupled with a Red winning streak which reached ten in a row, brought the two teams back together at Crosley Field the last weekend of the season in a virtual three-way tie with the Cardinals. Unfortunately for Chico Ruiz, the 1964 season would be the high point of his major league career. He never topped the number of games, at bats or hits he recorded that season. As an infielder he was cursed with bad timing: Reds shortstop Leo Cardenas was one of the best in the National League throughout the 1960s and the second baseman, Rose, was pretty fair also. A few years later, Rose was moved to the outfield and Tommy Helms, who also made a few All-Star teams, took over second base. The Reds eventually used third base for power hitters, first Deron Johnson, then Tony Perez, leaving Chico without a legitimate shot at a regular place in the line up. As will happen, Chico's skills, and perhaps his confidence, eroded the longer he sat on the bench. But he remained a valuable member of the team due to his readiness and upbeat attitude. Every ex-player I interviewed had nothing but good things to say about Chico.

Chico Ruiz was traded to the Angels in 1970 and was tragically killed in a car accident in California in 1972 at the age of 33 years. Here's to you Chico, bench me or trade me.

Published on April 02, 2011 07:10

March 19, 2011

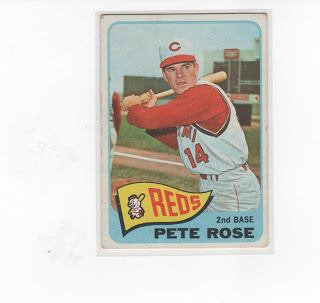

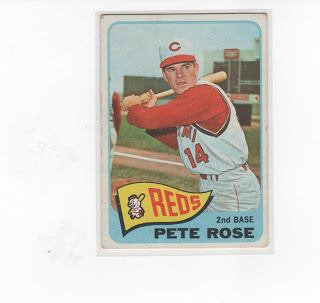

Hutch and Pete

Fred Hutchinson unknowingly helped Pete Rose break Ty Cobb's record. The 1962 Reds had won 98 games, but had finished in third place behind the Giants and the Dodgers. As a 21-year-old second baseman for the Macon Peaches, Pete Rose had torched the Class AA South Atlantic League, hitting .330 with 17 triples and scoring 136 runs. Most people in the Reds' organization felt that he needed at least one more year in the minors, however. Complicating matters was the fact that the Reds had a reliable veteran second baseman, Don Blasingame, who was coming off one of his best years. One man who felt that Pete was ready to make the jump from AA to the majors was Cincinnati manager Fred Hutchinson. He had witnessed Rose while in the Fall Instructional League and fell in love with his style of play. "I can clearly remember in the fall of 1962 my father telling my brother and I, 'If you want to see how the game of baseball should be played, come over tonight and watch one of our minor leaguers, Pete Rose,'" recalled Fred Hutchinson's son Jack, who was 17. "And, of course, being teenagers, we didn't really believe him at the time."

Hutch, an old-school battler who got the most out of his ability due to an iron will and intense competitiveness when he pitched for the Tigers, could see the same qualities in the gritty, hustling Rose. "If I had any guts, I'd stick Rose at second and just leave him there," Hutch told Cincinnati beat writer Earl Lawson that winter. Hutch was determined to give Pete every chance to make the team in 1963 and eventually named him the starter during spring training. Hutch stuck with Rose through an early slump and Rose rewarded him by becoming the Rookie of the Year, hitting .273 with 170 hits and 101 runs.

By spring training of 1964, Rose had established himself on the team and Lou Smith of the Cincinnati Enquirer proclaimed him the most popular player on the Reds according to fans, adding that Rose was "an earnest, honest youngster who loves the game so much he would play it for nothing."

Had Hutch gone with conventional wisdom and left Rose at AAA for 1963, it is probable that time would have run out on Rose's chase of Cobb's record 23 years later--he needed every one of those 170 hits that he got in 1963.

Hutch, an old-school battler who got the most out of his ability due to an iron will and intense competitiveness when he pitched for the Tigers, could see the same qualities in the gritty, hustling Rose. "If I had any guts, I'd stick Rose at second and just leave him there," Hutch told Cincinnati beat writer Earl Lawson that winter. Hutch was determined to give Pete every chance to make the team in 1963 and eventually named him the starter during spring training. Hutch stuck with Rose through an early slump and Rose rewarded him by becoming the Rookie of the Year, hitting .273 with 170 hits and 101 runs.

By spring training of 1964, Rose had established himself on the team and Lou Smith of the Cincinnati Enquirer proclaimed him the most popular player on the Reds according to fans, adding that Rose was "an earnest, honest youngster who loves the game so much he would play it for nothing."

Had Hutch gone with conventional wisdom and left Rose at AAA for 1963, it is probable that time would have run out on Rose's chase of Cobb's record 23 years later--he needed every one of those 170 hits that he got in 1963.

Published on March 19, 2011 09:10

March 12, 2011

New Book Highlights Sad Season For Reds, by Lew Freedman,...

New Book Highlights Sad Season For Reds, by Lew Freedman, The Republic, March 8, 2011

Cincinnati Reds fans’ memories of the 1964 season must be painful. Beloved manager Fred Hutchinson, forthright and open about his illness, announced he was suffering from cancer, yet continued to lead the club from the bench for much of a tense pennant race.

He did so as long as he was able, with interruptions for radiation treatments and in the face of a terminal diagnosis.

Doug Wilson, 49, a Columbus ophthalmologist, and Reds fan, has branched into a new field. He is the author of a new book called “Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds,” published by McFarland & Company, Inc., of North Carolina.

The book is well-researched and well-reported and although a sad story, very much a worthwhile read for baseball fans and especially Reds fans.

“I finally got a little time to write,” Wilson said of how he plunged into his first book. “I always was a Reds fan.”

Wilson interviewed many Reds figures from the 1960s, including Jim Brosnan, Sammy Ellis, Jim O’Toole, Mel Queen and Dave Bristol. He also had the assistance and cooperation of the Hutchinson family, including that of Hutchinson’s widow Patsy, 91.

Before becoming a respected manager, Hutchinson was a prominent athlete in his home area of Seattle. Born in 1919, Hutchinson was not yet 20 when he made his Major League debut as a pitcher for the Detroit Tigers.

In 10 big-league seasons he posted a record of 95-71 with a 3.73 earned run average. He won 18 games in 1947 and 17 in 1950 for the Tigers.

Hutchinson managed Detroit and the St. Louis Cardinals before taking over the Reds midway through the 1959 season. In 1961, Hutchinson led Cincinnati to its first pennant in 21 years. The next year the Reds won 98 games.

The portrait of Hutchinson Wilson paints is of a tough man with a big heart who was demanding of his players, but benevolent to them even as he was determined to make them winners. He seemed to have both a temper and a sense of humor.

After the Reds blew a double-header to the down-trodden expansion New York Mets with erratic play an angry Hutchinson said he wanted the clubhouse cleared in moments. The players fled to the bus so quickly most didn’t shower.

O’Toole, one of the Reds’ aces, was ordered to pitch the day after he got married.

“I didn’t set O’Toole’s wedding date,” Hutchinson growled.

Hutchinson broke Pete Rose into the lineup on a veteran team and stuck with him through his early tribulations. Rose became rookie of the year and baseball’s all-time hits leader.

By the time Hutchinson had a lump on his neck checked in December of 1963 his lung cancer was so far advanced Bill, his brother and physician, told him he had perhaps a year to live. Hutchinson was 44.

Hutchinson decided to go public and conducted a press conference in Seattle Jan. 2, 1964. He was to undergo immediate treatment, but was back in charge of the Reds by spring training.

What followed was a lengthy fight of man against the inexorable advance of disease. Showing remarkable daily courage, Hutchinson joked with his players, was candid with reporters, and wrote out the lineup card day after day.

Baseball fans nationwide responded to Hutchinson’s perseverance, sending cards and letters by the hundreds, a reaction that surprised him.

Gradually, as the season wore on and with the Reds striving for another pennant, Hutchinson’s weight loss and weakness pushed him into a leave of absence.

Perpetually gracious, never bitter, Hutchinson’s attitude amazed observers. “Whatever happens, I’m grateful for everybody’s good wishes,” he said in a True Magazine story headlined, “How I Live With Cancer.”

Hutchinson turned 45 in August, but then left the team for more treatment. His players were watching him waste away.

“It was an inspiration for us,” pitcher Joe Nuxhall said, “to try to win it for Hutch.”

Neither the Reds nor Hutchinson won their battle that poignant summer. The team didn’t capture the pennant and Hutchinson died Nov. 11.

As a long-time crusader for more focused, expanded attention on cancer treatment, Fred’s brother did win. Dr. Hutchinson spearheaded the fund-raising for construction of a cancer center in Seattle in 1965, one that has only grown since.

For those who know more about cancer than baseball, that center is world famous as the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Lew Freedman is sports editor of The Republic. He can be reached at lfreedman@therepublic.com or 379-5628.

Cincinnati Reds fans’ memories of the 1964 season must be painful. Beloved manager Fred Hutchinson, forthright and open about his illness, announced he was suffering from cancer, yet continued to lead the club from the bench for much of a tense pennant race.

He did so as long as he was able, with interruptions for radiation treatments and in the face of a terminal diagnosis.

Doug Wilson, 49, a Columbus ophthalmologist, and Reds fan, has branched into a new field. He is the author of a new book called “Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds,” published by McFarland & Company, Inc., of North Carolina.

The book is well-researched and well-reported and although a sad story, very much a worthwhile read for baseball fans and especially Reds fans.

“I finally got a little time to write,” Wilson said of how he plunged into his first book. “I always was a Reds fan.”

Wilson interviewed many Reds figures from the 1960s, including Jim Brosnan, Sammy Ellis, Jim O’Toole, Mel Queen and Dave Bristol. He also had the assistance and cooperation of the Hutchinson family, including that of Hutchinson’s widow Patsy, 91.

Before becoming a respected manager, Hutchinson was a prominent athlete in his home area of Seattle. Born in 1919, Hutchinson was not yet 20 when he made his Major League debut as a pitcher for the Detroit Tigers.

In 10 big-league seasons he posted a record of 95-71 with a 3.73 earned run average. He won 18 games in 1947 and 17 in 1950 for the Tigers.

Hutchinson managed Detroit and the St. Louis Cardinals before taking over the Reds midway through the 1959 season. In 1961, Hutchinson led Cincinnati to its first pennant in 21 years. The next year the Reds won 98 games.

The portrait of Hutchinson Wilson paints is of a tough man with a big heart who was demanding of his players, but benevolent to them even as he was determined to make them winners. He seemed to have both a temper and a sense of humor.

After the Reds blew a double-header to the down-trodden expansion New York Mets with erratic play an angry Hutchinson said he wanted the clubhouse cleared in moments. The players fled to the bus so quickly most didn’t shower.

O’Toole, one of the Reds’ aces, was ordered to pitch the day after he got married.

“I didn’t set O’Toole’s wedding date,” Hutchinson growled.

Hutchinson broke Pete Rose into the lineup on a veteran team and stuck with him through his early tribulations. Rose became rookie of the year and baseball’s all-time hits leader.

By the time Hutchinson had a lump on his neck checked in December of 1963 his lung cancer was so far advanced Bill, his brother and physician, told him he had perhaps a year to live. Hutchinson was 44.

Hutchinson decided to go public and conducted a press conference in Seattle Jan. 2, 1964. He was to undergo immediate treatment, but was back in charge of the Reds by spring training.

What followed was a lengthy fight of man against the inexorable advance of disease. Showing remarkable daily courage, Hutchinson joked with his players, was candid with reporters, and wrote out the lineup card day after day.

Baseball fans nationwide responded to Hutchinson’s perseverance, sending cards and letters by the hundreds, a reaction that surprised him.

Gradually, as the season wore on and with the Reds striving for another pennant, Hutchinson’s weight loss and weakness pushed him into a leave of absence.

Perpetually gracious, never bitter, Hutchinson’s attitude amazed observers. “Whatever happens, I’m grateful for everybody’s good wishes,” he said in a True Magazine story headlined, “How I Live With Cancer.”

Hutchinson turned 45 in August, but then left the team for more treatment. His players were watching him waste away.

“It was an inspiration for us,” pitcher Joe Nuxhall said, “to try to win it for Hutch.”

Neither the Reds nor Hutchinson won their battle that poignant summer. The team didn’t capture the pennant and Hutchinson died Nov. 11.

As a long-time crusader for more focused, expanded attention on cancer treatment, Fred’s brother did win. Dr. Hutchinson spearheaded the fund-raising for construction of a cancer center in Seattle in 1965, one that has only grown since.

For those who know more about cancer than baseball, that center is world famous as the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Lew Freedman is sports editor of The Republic. He can be reached at lfreedman@therepublic.com or 379-5628.

Published on March 12, 2011 07:06

Catching up with an old ex-Reds batboy

I was fortunate to catch up with former Reds batboy Mike Holzinger recently. Holzinger, who is now a representative for a surgical laser company, was batboy for the Cincinnati Reds in 1964 as a 15 year old. He describes that time as "the best summer of my life."

Along with the long hours and work--making five bucks a day--he got the unforgettable opportunity to get to know the Reds players. As batboy he had the run of Crosley Field and both clubhouses, mixing with players and coaches. He fondly recalls watching one game sitting next to Dodgers Sandy Koufax and Pee Wee Reese (who was a coach then).

He remembers Reds pitcher Jim O'Toole as an extremely tough competitor on days he pitched, but an irrepressible joker on the other days. O'Toole also was guilty of snitching Holzinger's lunches on occasion. "I used to get a sandwich and leave it in the clubhouse for after the games," says Holzinger. "But they kept disappearing. I finally caught O'Toole. He told me, 'Start ordering two sandwiches.' Then he quickly added, 'But don't tell Hutch.'"

Cuban shortstop Leo Cardenas caused some headaches for the batboy due to his refusal to ever use a bat which he thought "didn't have any hits in it." If Cardenas used a bat and went hitless for the day, he would discard that bat. "One time I had to complain to hitting coach Dick Sisler," says Holzinger. "Cardenas had a stack of 32 bats but wouldn't use any of them because he thought they didn't have any hits in them."

A special treat for the batboys was to accompany the team on two road trips a year. Holzinger went to New York and St. Louis with the Reds. He recalls what a nice guy first baseman Gordy Coleman was, taking the youngster under his wing and helping him get around New York City. Also, he warmly recalls listening to old baseball stories over breakfast in St. Louis with venerable Reds radio man Waite Hoyt, whose favorite team mate during his playing days with the Yankees was a certain hot dog-eating, home run-hitting right fielder.

One of the neat things Mike showed me from his batboy days was an official letter he received, addressed "to the Cincinnati National League Club Players," from then commissioner Ford Frick, dated October 28, 1964, which noted that the second place Reds' share of the 1964 World Series Receipts was $42,661.86 and showed how the money was to be distributed according to the teams' vote. Each regular player and coach received a full share of $1,254.76. The bat boys were voted a share of $209.13--not a bad bonus for a 15-year-old. Of interest on the list was one Atanasio Perez--known to most later as Tony--who played in a handful of games that year. He was voted a share of $250.95. So, for one season, Mike Holzinger was worth only $41.82 less to the Reds than a future Hall of Famer. How many 62-year-old medical laser reps can say that?

One of the neat things Mike showed me from his batboy days was an official letter he received, addressed "to the Cincinnati National League Club Players," from then commissioner Ford Frick, dated October 28, 1964, which noted that the second place Reds' share of the 1964 World Series Receipts was $42,661.86 and showed how the money was to be distributed according to the teams' vote. Each regular player and coach received a full share of $1,254.76. The bat boys were voted a share of $209.13--not a bad bonus for a 15-year-old. Of interest on the list was one Atanasio Perez--known to most later as Tony--who played in a handful of games that year. He was voted a share of $250.95. So, for one season, Mike Holzinger was worth only $41.82 less to the Reds than a future Hall of Famer. How many 62-year-old medical laser reps can say that?

Along with the long hours and work--making five bucks a day--he got the unforgettable opportunity to get to know the Reds players. As batboy he had the run of Crosley Field and both clubhouses, mixing with players and coaches. He fondly recalls watching one game sitting next to Dodgers Sandy Koufax and Pee Wee Reese (who was a coach then).

He remembers Reds pitcher Jim O'Toole as an extremely tough competitor on days he pitched, but an irrepressible joker on the other days. O'Toole also was guilty of snitching Holzinger's lunches on occasion. "I used to get a sandwich and leave it in the clubhouse for after the games," says Holzinger. "But they kept disappearing. I finally caught O'Toole. He told me, 'Start ordering two sandwiches.' Then he quickly added, 'But don't tell Hutch.'"

Cuban shortstop Leo Cardenas caused some headaches for the batboy due to his refusal to ever use a bat which he thought "didn't have any hits in it." If Cardenas used a bat and went hitless for the day, he would discard that bat. "One time I had to complain to hitting coach Dick Sisler," says Holzinger. "Cardenas had a stack of 32 bats but wouldn't use any of them because he thought they didn't have any hits in them."

A special treat for the batboys was to accompany the team on two road trips a year. Holzinger went to New York and St. Louis with the Reds. He recalls what a nice guy first baseman Gordy Coleman was, taking the youngster under his wing and helping him get around New York City. Also, he warmly recalls listening to old baseball stories over breakfast in St. Louis with venerable Reds radio man Waite Hoyt, whose favorite team mate during his playing days with the Yankees was a certain hot dog-eating, home run-hitting right fielder.

One of the neat things Mike showed me from his batboy days was an official letter he received, addressed "to the Cincinnati National League Club Players," from then commissioner Ford Frick, dated October 28, 1964, which noted that the second place Reds' share of the 1964 World Series Receipts was $42,661.86 and showed how the money was to be distributed according to the teams' vote. Each regular player and coach received a full share of $1,254.76. The bat boys were voted a share of $209.13--not a bad bonus for a 15-year-old. Of interest on the list was one Atanasio Perez--known to most later as Tony--who played in a handful of games that year. He was voted a share of $250.95. So, for one season, Mike Holzinger was worth only $41.82 less to the Reds than a future Hall of Famer. How many 62-year-old medical laser reps can say that?

One of the neat things Mike showed me from his batboy days was an official letter he received, addressed "to the Cincinnati National League Club Players," from then commissioner Ford Frick, dated October 28, 1964, which noted that the second place Reds' share of the 1964 World Series Receipts was $42,661.86 and showed how the money was to be distributed according to the teams' vote. Each regular player and coach received a full share of $1,254.76. The bat boys were voted a share of $209.13--not a bad bonus for a 15-year-old. Of interest on the list was one Atanasio Perez--known to most later as Tony--who played in a handful of games that year. He was voted a share of $250.95. So, for one season, Mike Holzinger was worth only $41.82 less to the Reds than a future Hall of Famer. How many 62-year-old medical laser reps can say that?

Published on March 12, 2011 07:02

January 9, 2011

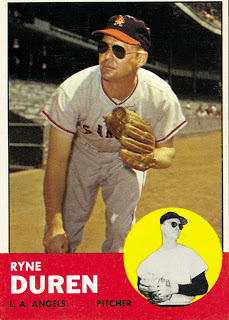

RIP Ryne Duren

Ryne Duren passed away this weekend. He was one of baseball's alltime great characters. I had the priviledge of interviewing Mr. Duren last year for my book, Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds. I wrote him a letter explaining the book and asked for permission to conduct an interview. He wrote me back, gave me his cellphone number with the best time to call, and added "Glad to help, Ryne." When I called, he was happy to talk to me and explained that he was, "Doing what I love, driving through back country Wisconsin roads on my way to dinner." The thought of the man famous for his poor vision driving along winding roads with one hand on the steering wheel and the other on the phone was somewhat unnerving, but I didn't hear a crash and he made it to his destination. Mr. Duren was extremely open and helpful and provided lots of funny stories. At the conclusion of the interview he explained that, at 80 years of age, he still found time to travel delivering his message on the perils of alcohol addiction. "The answer is always yes whenever people ask me to come talk," he said. "Money is never a factor in whether or not I come."

The following is an excerpt from the book:

Ryne Duren, 35, was already a legend when the Reds purchased him from the Phillies May 13. His reputation preceded him to Cincinnati. When first discovered in the tiny Wisconsin town of Cazenovia, his fastball exceeded 100 miles per hour. He was said by most baseball men of the time to be faster than anyone other than Bob Feller. The problem was that no one, especially Ryne, knew where the ball would go when he turned it loose. It was reported that he had not been allowed to pitch in high school after breaking a batter’s ribs. Later, another problem was found: he couldn’t see. His vision was measured at 20/70 and 20/200—almost legally blind. He was rumored to have once hit a man in the on-deck circle. When he finally made it to the big leagues, Ryne was smart enough to use these stories to his advantage. His warm-up routine when he came into a game from the bullpen classically started with a nasty heater flung up against the backstop. He squinted in at the plate through coke-bottle thick, darkly tinted glasses. Strong men had to battle their better judgment before stepping into the batter’s box against Rinold Duren. “Part of that was an act,” Duren says with a chuckle. “It started in New York. I was a pretty good drinking buddy of some of the New York writers and they told me, ‘Hey, throw one up at the stands.’ They needed something to write about. Of course, it didn’t hurt me when the batters didn’t want to dig in.” The story about hitting a guy in the on-deck circle was partially true. “It was Jimmy Piersall in Boston,” Duren remembers warmly. “Ted Williams used to come up from the on-deck circle and watch you pitch when you warmed up, to get a closer look at the timing. Sometimes he would take a practice swing as the ball crossed the plate. But he was Ted Williams, what are you going to do? Then one day, I’ll be damned if Piersall didn’t come over and do that. Well, he was no Ted Williams. So I threw a ball in his direction. I didn’t get too close, it was just to get his attention. He shouted, ‘What the hell’s the matter with you?’ I said, ‘What the hell’s the matter with you. You’ve got yourself confused with a hitter.’ That’s probably where the story got started.” Ryne Duren was soon found to be a guy who also liked to have fun, which allowed him to fit in with the Reds quickly. “The Reds were about the rowdiest team I ever played on,” he says. And he had played on the Angels and Yankees of the early sixties—teams known for their enjoyment of off-field activities. “We had a bunch of guys who had a lot of fun together,” says catcher John Edwards. “Deron Johnson, Maloney, O’Toole, Nuxhall. Ryne joined in. We goofed around a little bit. Ryne Duren thought the telephone was the greatest invention there ever was. He would call all around the world. He called Princess Grace in Monaco. He called President Johnson at the White House--I think he almost got in trouble over that one.” Bat boy Mike Holzinger recalls an incident in which Duren answered the phone in the Crosley Field bullpen before a game. “It was Mrs. DeWitt, she was looking for one of the coaches or something,” says Holzinger. Unfortunately for the owner’s wife, Ryne Duren did not just use a phone for communication but used it for fun as well. “He started giving her a real hard time, talking back, laughing and refusing to help her. Finally I heard her shout over the phone, ‘Who is this?’ Ryne answered, ‘Gordy Coleman’ and hung up.” There was a dark side to the Ryne Duren story, however. He was an alcoholic. In an era when most players drank, Ryne seemed to drink differently. Teammates on other teams had noted that he had trouble knowing when to stop. Many times he woke up with no memory of the preceding night—only broken doors and furniture and a black eye to give him hints. “One time in New York, Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle told me I shouldn’t drink,” says Duren of those two noted Yankee milkshake drinkers. “They said I was a different type of drinker.” “I was so addicted to alcohol that it was part of my makeup and personality,” Duren continues. “I think I was probably irreversibly addicted from a very early age. Alcohol is a drug and if you don’t understand it as such it’s pretty dangerous.” Duren lost more than one baseball job during his career because of off field, alcohol-fueled incidents. That was the reason the Yankees had dumped him, the Angels had let him go and the Phillies had sold him to the Reds. In the early sixties the term “alcoholic” was rarely used and never used associated with baseball. Many players during those years ruined their careers and lives without ever getting treatment. “I knew a lot of guys who drunk themselves to death,” says Duren. * * * After baseball, Ryne Duren successfully underwent alcoholic rehab and spent years as an alcoholic counselor and speaker. He was one of the first to speak out to organized baseball about the problem of alcoholism. He proudly told me that he had not had a drink in 41 years. He did not say how long it had been since he had tried to call Princess Grace. Ryne Duren, a great baseball character and a great guy who remade himself and tried to help others overcome the same demons which he had battled--we're going to miss him.

The following is an excerpt from the book:

Ryne Duren, 35, was already a legend when the Reds purchased him from the Phillies May 13. His reputation preceded him to Cincinnati. When first discovered in the tiny Wisconsin town of Cazenovia, his fastball exceeded 100 miles per hour. He was said by most baseball men of the time to be faster than anyone other than Bob Feller. The problem was that no one, especially Ryne, knew where the ball would go when he turned it loose. It was reported that he had not been allowed to pitch in high school after breaking a batter’s ribs. Later, another problem was found: he couldn’t see. His vision was measured at 20/70 and 20/200—almost legally blind. He was rumored to have once hit a man in the on-deck circle. When he finally made it to the big leagues, Ryne was smart enough to use these stories to his advantage. His warm-up routine when he came into a game from the bullpen classically started with a nasty heater flung up against the backstop. He squinted in at the plate through coke-bottle thick, darkly tinted glasses. Strong men had to battle their better judgment before stepping into the batter’s box against Rinold Duren. “Part of that was an act,” Duren says with a chuckle. “It started in New York. I was a pretty good drinking buddy of some of the New York writers and they told me, ‘Hey, throw one up at the stands.’ They needed something to write about. Of course, it didn’t hurt me when the batters didn’t want to dig in.” The story about hitting a guy in the on-deck circle was partially true. “It was Jimmy Piersall in Boston,” Duren remembers warmly. “Ted Williams used to come up from the on-deck circle and watch you pitch when you warmed up, to get a closer look at the timing. Sometimes he would take a practice swing as the ball crossed the plate. But he was Ted Williams, what are you going to do? Then one day, I’ll be damned if Piersall didn’t come over and do that. Well, he was no Ted Williams. So I threw a ball in his direction. I didn’t get too close, it was just to get his attention. He shouted, ‘What the hell’s the matter with you?’ I said, ‘What the hell’s the matter with you. You’ve got yourself confused with a hitter.’ That’s probably where the story got started.” Ryne Duren was soon found to be a guy who also liked to have fun, which allowed him to fit in with the Reds quickly. “The Reds were about the rowdiest team I ever played on,” he says. And he had played on the Angels and Yankees of the early sixties—teams known for their enjoyment of off-field activities. “We had a bunch of guys who had a lot of fun together,” says catcher John Edwards. “Deron Johnson, Maloney, O’Toole, Nuxhall. Ryne joined in. We goofed around a little bit. Ryne Duren thought the telephone was the greatest invention there ever was. He would call all around the world. He called Princess Grace in Monaco. He called President Johnson at the White House--I think he almost got in trouble over that one.” Bat boy Mike Holzinger recalls an incident in which Duren answered the phone in the Crosley Field bullpen before a game. “It was Mrs. DeWitt, she was looking for one of the coaches or something,” says Holzinger. Unfortunately for the owner’s wife, Ryne Duren did not just use a phone for communication but used it for fun as well. “He started giving her a real hard time, talking back, laughing and refusing to help her. Finally I heard her shout over the phone, ‘Who is this?’ Ryne answered, ‘Gordy Coleman’ and hung up.” There was a dark side to the Ryne Duren story, however. He was an alcoholic. In an era when most players drank, Ryne seemed to drink differently. Teammates on other teams had noted that he had trouble knowing when to stop. Many times he woke up with no memory of the preceding night—only broken doors and furniture and a black eye to give him hints. “One time in New York, Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle told me I shouldn’t drink,” says Duren of those two noted Yankee milkshake drinkers. “They said I was a different type of drinker.” “I was so addicted to alcohol that it was part of my makeup and personality,” Duren continues. “I think I was probably irreversibly addicted from a very early age. Alcohol is a drug and if you don’t understand it as such it’s pretty dangerous.” Duren lost more than one baseball job during his career because of off field, alcohol-fueled incidents. That was the reason the Yankees had dumped him, the Angels had let him go and the Phillies had sold him to the Reds. In the early sixties the term “alcoholic” was rarely used and never used associated with baseball. Many players during those years ruined their careers and lives without ever getting treatment. “I knew a lot of guys who drunk themselves to death,” says Duren. * * * After baseball, Ryne Duren successfully underwent alcoholic rehab and spent years as an alcoholic counselor and speaker. He was one of the first to speak out to organized baseball about the problem of alcoholism. He proudly told me that he had not had a drink in 41 years. He did not say how long it had been since he had tried to call Princess Grace. Ryne Duren, a great baseball character and a great guy who remade himself and tried to help others overcome the same demons which he had battled--we're going to miss him.

Published on January 09, 2011 11:50

Doug Wilson's Blog

- Doug Wilson's profile

- 43 followers

Doug Wilson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.