Doug Wilson's Blog, page 5

September 30, 2016

Mike Torrez: He Threw Lots of Other Pitches

One lousy pitch.

That's all they'll ever remember.

It's an unfortunate aspect of sport that a man can perform better than average for 10 or 15 years, but one less-than-happy result can sully his reputation for eternity.

This is the cross Mike Torrez must bear. He was a quality starting pitcher during a career that included parts of 18 major league seasons. A workhorse during the 1970s, from 1972-79 he averaged 240 innings pitched and nearly 16 wins a year. In a career that included 458 starts, if we assume around 100 pitches per start, that gives him roughly 45,000 pitches thrown. It is safe to assume that, given his longevity in the league, the vast majority of those 45,000 or so pitches did exactly what he intended for them to do: set up a batter for an out.

One memorable pitch, however, did not. There is absolutely no doubt that when Mike Torrez passes away, the first line of his obituary will include a prominent reference to that one pitch, thrown on an 0-2 count with two outs in the seventh inning to Mr. Bucky F. Dent of the New York Yankees in Fenway Park on October 2, 1978.

Most likely the obituaries won't mention the fact that until that one pitch, Torrez had pitched great in what was the 163rd game of the year; a game to determine the division championship. They also won't mention that in any other major league park the ball would have been a can of corn and not a home run or that the blow did not end the game, that actually a home run by Reggie Jackson off Bob Stanley an inning later provided the ultimate deciding margin. All of that seems to have been lost in the collective fog that is our memory of such events. Torrez was forced to wear the goat horns, made progressively all the more heavy with each passing year that the championship-starved Sox fans endured over the next three decades.

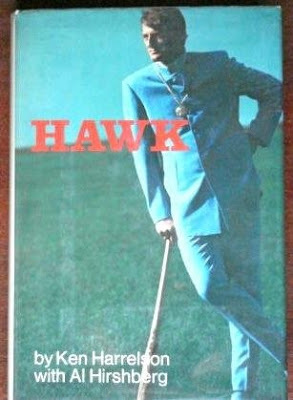

But the Mike Torrez story is about much more than the one fateful pitch. Jorge Iber, a distinguished professor of history at Texas Tech, has released a new book, Mike Torrez: A Baseball Biography, which explains all this.

A prominent undertone throughout the story is the fact that Mike Torrez, the grandson of immigrants who moved to Kansas to escape the violence of the Mexican Revolution in 1911, became one of the greatest Mexican-American players in major league baseball history. Torrez has won more major league games than any other Mexican-American pitcher. His career record of 185-160 compares favorably with the more celebrated Fernando Valenzuela (173-153). Iber has published extensively, both in academic and popular venues, on the Mexican-American and Latin American experience, and has a particular interest in baseball. He puts this expertise to good use explaining Torrez' background and upbringing and detailing the hurdles he had to overcome.

Mike Torrez grew up in a hard-working barrio in Topeka, Kansas. His life's course was forever altered when he discovered that he could hurl a baseball with much more velocity than anyone else in the area. As a youngster, he won a pitching contest sponsored by the Class A Topeka Reds and was given tips by the teams' star, Jim Maloney. After starring for American Legion teams in the area, Torrez was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals.

The career of Mike Torrez reads like a mini-review of prominent names and events of the 1960s and 1970s. He came up with the Cardinals for cups of coffee as they charged to pennants in 1967 and 1968. He made the rotation in 1969, going 10-4 as a 22-year-old rookie. Unfortunately for Torrez, he arrived just as the powerful team was being dismantled for financial reasons. While with the Cards, Torrez befriended Curt Flood and would forever appreciate Flood's sacrifice for the benefit of future players.

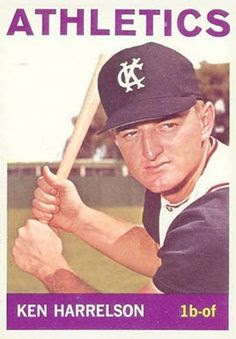

Torrez blossomed after a trade to Montreal in 1972, becoming one of the most durable starting pitchers of the decade. He had his best season, winning 20 games, with Baltimore in 1975. Traded in 1976 with Don Baylor for Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman, he spent a turbulent year in Oakland as the A's dynasty was winding down due to the threat of increasing salary demands.

Salary struggles and the changing economics of the game played a prominent role in each stop for Mike Torrez and his story is set upon the background of the player union revolution. When Torrez first visited the Cardinals, before signing a contract, he was warned by second baseman Julian Javier in Spanish to be careful, that the Cards would try to take advantage of him with a low-ball offer. Not knowing any better, he went ahead and signed and later learned that Javier was right.

As the pendulum in player-owner relations swung, Torrez became more wary and savvy. In one of the more entertaining parts of the book, Iber explains that after the 1976 season, in which Torrez won 16 games with a 2.50 ERA, he received a contract from Charlie Finley calling for a 20 % raise to $100,000 a year. Surprised at the largess from the notoriously penny-pinching owner, Torrez soon received a call from a contrite Finley who explained that due to cutbacks in the front office he had been forced to do the paperwork himself and had made a mistake--he actually wanted to cut the salary by 20%. "Let's treat this like gentlemen," Finley told him. "Let's tear up the contract." Finley offered as compensation a year's supply of his famous chili (Torrez, not surprisingly, declined the chili and kept the hundred grand).

Shipped to New York in a salary dump, Torrez joined the Billy Martin-Reggie Jackson-Thurman Munson Bronx Zoo and ended up winning two games for the Yankees in the 1977 World Series, including the clincher.

Fresh off the World Series heroics, Torrez became the first person with a Mexican background to be named "Kansan of the Year." He became one of the first big free agent signees, inking a 7-year deal for a cool two-and-a-half million dollars with the Red Sox, unbelievable numbers at the time, especially for a kid from his background. The deal would be a turning point in Torrez' life, and not necessarily for the better. Much was expected of Torrez because of the big salary and he was singled out by disappointed fans when the Sox failed to deliver .

The book details the painful sequelae in Boston for Torrez after the 1978 season--six more years of boos. The infamy persisted, joined by that of Bill Buckner, until the demons were exercised by the championship of 2004. For a long time Torrez bore hard feelings for Boston due to his treatment by fans.

The book was written with extensive participation by Torrez and contains many pictures from his personal collection. Also Iber interviewed teammates such as Dennis Eckersley and Ken Singleton along with Torrez' former wife. Along with his baseball exploits, the book details some of Torrez' off-field fun and trials. Iber describes him in his heyday as a "Knight of the Neon," known for partying seventies style.

Overall, this is a good read for any baseball fan and a nice trip back through the decades of the '60s, '70s and '80s. Iber is a professional historian who knows how to conduct research and it shows.

Published on September 30, 2016 06:38

August 13, 2016

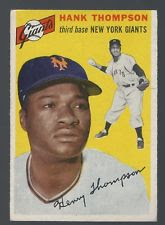

The Turbulent Life and High Times of Hank Thompson, Baseball's Third Black Player

We real cool. WeLeft school. WeLurk late. We Strike straight. WeSing sin. WeThin gin. WeJazz June. WeDie soon.

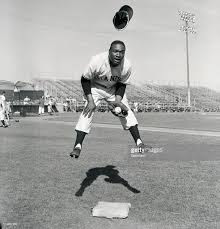

Few players in baseball history ever embodied Gwendolyn Brooks’ classic poem--every single line-- the way Hank “Machine Gun” Thompson did. Thompson was a talented ballplayer and a pioneer, the third black player ever to grace major league fields. Although he had a solid career, he has unfortunately been forgotten by modern fans. There’s a reason.

Trouble found Hank Thompson early and often, although when he later had a few stiff belts, he didn’t exactly hide from it. You could say Hank had a tough childhood; and you'd be guilty of a gross understatement.

Hank's old man was an alcoholic who took a leather strap to his kids whenever he felt the need. But mostly, he just wasn't around. By the time Hank was five, his father was gone forever. Thereafter the totally segregated streets of North Dallas, the city’s impoverished African-American section, became his home. This was a time when everyone was expected to know his place; separate but unequal was the law of the land. Sneak over to play on the wrong playground and someone would call the cops. The nearby Moorland YMCA had the only pool in town black kids could jump into on sweltering summer days. Kids who looked like Hank weren't allowed to go to the Texas state fair, even though they lived within walking distance of the fairgrounds. They let them in one day each summer; it was called "Negro Day."

Hank’s mother worked hard to pay the bills, frequently leaving the house before 6 AM and returning after sundown. Left in the care of his older sister and brothers, Hank had little direction. School held no promise or interest for him. While he later said he skipped school to play baseball, this is most likely a middle-aged man’s euphemism. The only kids out during school hours were other truants and older guys who had dropped out. These became his peers. And it’s doubtful they spent most of their time playing ball.

At age 12 Hank did a stent in the Gatesville State School for boys, a Texas reform school near Waco; reportedly for chronic truancy but there was also an arrest about that time for stealing jewelry out of a car. Gatesville was an overcrowded place for the state’s throw-away kids and had a reputation for ruthlessness—both from the guards and from the other delinquents.

Released from Gatesville as an early teen, Hank was back on the streets of North Dallas, finished with school forever. The pool halls and jazz joints of the notorious Deep Ellum section of town became his haunts. He later said he began drinking by 15. He liked the taste.

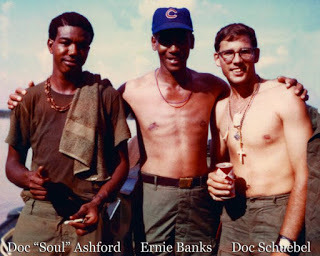

But Hank Thompson could play ball. At the time, fast-pitch softball was the game in North Dallas. Playing in the rec leagues and church leagues, Hank quickly got a reputation due to a quick, short stroke –like a Joe Louis punch--that launched impressive home runs. A skinny Dallas kid named Ernie Banks, five years younger, was so impressed with Thompson’s swing that he later claimed he spent an entire summer trying to emulate it.

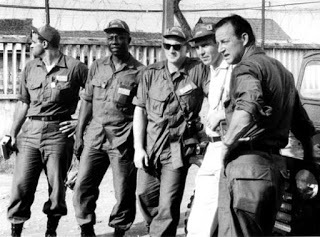

By the age of only 17, Hank was playing professionally for the fabled Kansas City Monarchs. He was given the nickname "Machine Gun" due to the rapid-fire line drives that flew off his bat in practice. After a solid first season, he was drafted into the Army in March of 1944. Hank served in an all-black engineering unit commanded by white officers and spent the occasional night in the stockade for drunkenness. His unit made it to Europe in time to participate in heavy action, particularly during the Battle of the Bulge, where Thompson manned a machine gun. “If there was ever a moment that I did something for society, that was it,” he said in 1965. “But you can’t make three good days balance off the rest of a man’s life.”

Discharged from the Army in 1946, Thompson returned to the Monarchs and became one of their stars. The 5-9, 170 pound Thompson generated serious power and consistently hit between .300 and .350. Still only 20 years old, he picked up the habit, which he would keep for years, from some of the older players of carrying a gun. It would be a habit that he would later regret.

In July, 1947, just three months after Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers, Thompson and Willard Brown were purchased from the Monarchs by the St. Louis Browns for a 30-day trial. The deal was that if the two proved their worth, at the end of that time they would stay with the Browns and the Monarchs would receive more money.

But the Browns were a public fiasco masquerading as a baseball team. A perennially last-place team that drew less than 5,000 a game, by far the lowest in the majors, their owners continually sold off any decent players to make ends meet. The Browns’ vice-president and general manager, Bill DeWitt, had watched with envy as the Brooklyn Dodgers attendance figures skyrocketed after the addition of Jackie Robinson. He ordered his head scout to round up some black players who could play major league baseball.

Unfortunately for Thompson and Brown, their trial was as bumbling and poorly planned as the Dodgers trial for Jackie Robinson had been well-orchestrated. Whereas Robinson was carefully scouted, for talent, temperament and habits, was given time in the farm system to acclimate--and also for teammates to acclimate to him—and was given the unquestionable full support of the front office, Thompson and Brown were merely thrown in with the lousy team. It was a situation which was so destined to fail that some have questioned the Browns’ motives.

While Brown and Thompson had obvious talent, it is also evident that they were the types Branch Rickey had warned about with his oft-used line that, in order for the great experiment of integration to work, the first blacks in major league baseball had to be of a special character as well as playing ability. The 32-year-old Brown, whose on-field exploits were as legendary as any player in the Negro Leagues, and who would later be named to Baseball’s Hall of Fame solely on those exploits, had a reputation as a head-strong guy who played hard only when he wanted to. Thompson was known as a hothead and was already an alcoholic. Neither quite fit Rickey’s criteria.

The manager of the Browns was Muddy Ruel, a former catcher from St. Louis, who went on record as saying he didn’t want the two black players. Teammates did not welcome the pair. “No one on the club would have anything to do with us,” Thompson said in a Washington Afro-American interview in 1950. “They wouldn’t speak to us and they wouldn’t even warm up with us. If Brown wasn’t around and I asked another player to warm up with me, he’d just shake his head.” Thompson’s only company, besides Brown, was a bottle of Dewar’s.

Thompson got the first chance to play, on July 17, 1947, less than two weeks after Larry Doby had taken the field for Cleveland, narrowly missing the distinction of becoming the first black player in the American League. He went 0-4 and made an error at second base. Brown debuted two days later. They settled into a routine whereby the two—heavily advertised of course--would play the first game of a series then, unless they did something spectacular, they would sit. Both became frustrated watching their inept new teammates flounder while they sat the bench. Brown remarked that his old Monarchs could thrash this Browns team without even trying.

Veteran sportswriter Sam Lacy, of the Baltimore Afro-American, who usually called things as he saw them in racial issues, interviewed Ruel a couple of weeks into the trial. He came away believing the two would get a serious evaluation. “Each time he spoke of Brown or Thompson, it was as though either or both were just two new men—not two colored men,” he wrote.

But it was not to be; neither got much of a chance. Thompson played more, 27 games in all, and hit .256. Brown, despite impressive displays of power in batting practice, only got 67 at bats and hit .179. The Browns attracted a few more fans on the road, but home attendance failed to increase.Although the .256 Thompson hit was considerably better than the Browns team batting average of .241 for the year and Willard Brown had more ability than the rest of the team put together, both players were returned to the Monarchs. Bill DeWitt told the media they “had failed to reach major league standards.” When viewed from afar, the trial appeared to be solely a quick attempt to increase attendance and when that failed the two were dumped. DeWitt was a man of questionable racial tendencies who later as the owner of the Cincinnati Reds ordered rookie Pete Rose to stop hanging around the colored players and demonstrated his ability to judge “major league standards” when he pawned off Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, Jack Baldschun and Dick Simpson in one of the worst trades in baseball history.

In the spring of 1948 Hank stopped by Dallas to visit his sister on his way to the Monarch’s spring training camp in San Antonio. While in a bar with his brother-in-law, Hank ran into an ex-sandlot teammate named Buddy Crow. The two had never liked each other and Crow taunted Hank about his abbreviated major league career. Words quickly turned nasty, tempers flared and Crow whipped out a knife. Hank later said he had seen what Crow could do with a knife before when he had filleted someone’s stomach open and intestines spilled out on the floor. He didn’t want to chance that happening to him. He pulled his gun and fired three shots into Crow’s chest. Crow lay dead on the floor of the bar and Thompson fled. The next day, at his sister’s urging, Hank turned himself in. He was allowed to post bail and two days later joined the Monarchs in San Antonio. The case was later dismissed as justifiable. He expressed remorse in 1965 saying, “seventeen years later I still haven’t gotten over it.”

Hank's play on the field continued to attract notice. He was purchased from the Monarchs by the New York Giants in February, 1949. It speaks to the 23-year-old’s talent and potential that he helped integrate two different teams. He was sent first to the Giants' Jersey City farm team to acclimate himself. When he was brought up to New York in mid-season, arriving along with Monte Irvin, who had also been signed from the Negro Leagues, he became the first black to play in both leagues.

This time everything was different. Rather than playing in the southernmost city in baseball, Hank joined a team who played their games in the Polo Grounds, in upper Manhattan, next to Harlem. The Giants manager was Leo Durocher. While Leo was many things, he was not a racist; the only color he cared about was green—the color of the money to be won for a pennant. Leo had played an important role in Jackie Robinson's acceptance with Brooklyn earlier. Hearing about a petition some Dodger players were circulating protesting Robinson's presence, Leo called a late-night team meeting and told them where they could stick their petition.

On the day of the arrival of Thompson and Irvin, Leo gathered his team in the clubhouse and told them, "This is all I'm going to say about race. I don't give a damn about what color you are. As long as you play good baseball, you can play on this team. We got Monte and Hank here. They got good credentials. I'm sure they'll help us get out of fifth place. We're all one team." And no one dared buck Leo's policy.

Monte Irvin was a perfect older settling influence for the young Thompson. Irvin, 30 years old in 1947, was a strong character who would later become one of the most respected men in baseball. “Every once in a while Thompson would get out of line and Monte would get on his case,” second baseman Bill Rigney later said.

Hank’s initial game as a Giant, July 8, 1949, was another first of sorts. When he faced Brooklyn’s Don Newcombe it was the first time two black men faced each other in a major league game.

Hank’s reputation as a tough character preceded him. Everyone knew he had killed a man. Teammates gave him room, especially when he had been drinking. But otherwise, he and Irvin were readily accepted. “Things have been smooth,” Hank told a reporter for the New York World Telegram in April, 1950. He added that he had been getting along well, on the whole, with the Giant players. “There’s always one or two smart guys no matter where you go. A couple of them spoke out of turn to me even this spring and I told them where to get off.”

Other than the "one or two smart guys," Thompson and Irvin had it much easier than most of their contemporary pioneers in baseball integration. Irvin later noted that, as far as teammates, the Giants of that era had almost no racial tension. It was a unique blend of personalities in which the two, and Willie Mays who joined them in 1951, were accepted merely for their ability to help the club. "Once you put on that uniform, it wasn't between black and white," said Irvin. "It was the Giants against the Dodgers. The name of the team on the front of your uniform mattered more than the color of your skin."

Speaking of the young Willie Mays, legend has it that Thompson gave Willie his first taste of hard liquor—and the reeling Mays had to be carried from the room.

Thompson thrived for the Giants. Described as an acrobatic fielder, Hank could play infield or outfield, but settled in at third base. In 1950 he set a major league record for most double plays by a third baseman in one season (43) and had a solid year at the plate hitting .289 with 20 home runs and 91 RBIs.

He was severely spiked in 1951 and missed much of the frantic stretch run by his teammates as they overtook the Dodgers. He got a second chance when Giant right fielder Don Mueller broke his ankle sliding into third base just before Bobby Thomson’s historic home run in the playoffs. For the World Series, Durocher put Hank in the outfield (instead of moving Bobby Thomson from third to his more natural position in the outfield). Many people felt Durocher, who never missed a chance to stick it to the establishment, purposely did this to have three black men play in the outfield together for the first time in baseball history—and they did it in venerated Yankee Stadium no less.

Hank came back strong in 1952 and strung together three more solid seasons. In 1953 he hit .302 with 24 home runs. In 1954, he was second on the team with 26 homers and 86 RBIs. Perhaps Hank Thompson's greatest moment in baseball came during the 1954 World Series, the surprise Giants sweep over a Cleveland team that had set a record with 111 wins. Hanks scored six runs and had a hit in each game, hitting .364 overall. He also broke Lou Gehrig’s record for most walks in a Series, getting 7 to give him a .611 on base percentage.

Although Hank lacked the electric charisma of Mays and the commanding presence of the universally respected Irvin, making him much less popular with the national media, he was a hero to the hometown Harlem fans nonetheless. After the Series, he got a raise to $16,000 a year.

But Hank Thompson, loose on the streets of Harlem with a pocketful of money was not a good mix. There were high times; high living. Every night was Uptown Saturday Night. Hank bought a sweet Lincoln Capri. He had a closet full of $200 custom-tailored suits. He was spotted flashing hundred dollar bills around. When he was in a good mood, he might spring for a round for an entire bar. When he was in a bad mood . . .

Stanley Glenn, a former Negro League teammate, later described him as “a little bit off center. He had a drinking problem and a woman problem. He was like a time bomb.”

In 1963 Gary Schumacher, the veteran public relations man for the Giants, said, “He always had a drinking problem. When he drank, he would do things that you just couldn’t explain. It was like a shade came down over his mind.”

After a home game Hank would head straight to a bar and have two or three scotches “to get the game out of my system.” Then he might get a steak dinner, head home and “drink a fifth of Scotch or maybe two fifths.” While he claimed to never drink before games, he admitted that often come game time he felt “weak as a kitten.”

Problems with drink were not uncommon in baseball at the time although the term alcoholic was never used. Teammate and 1954 World Series MVP Dusty Rhodes was said to be unable to hit without a hangover, although, as far as anyone knows, he never tried. Over in Brooklyn, Don Newcombe was fighting a losing battle of his own with the bottle, a battle that would derail a potential Hall of Fame career.

The high living began to take its toll. Hank’s career, and life, started to unravel. In 1953 there was a 4 AM incident on a Harlem street involving a cab driver, a sawed-off bat used as a weapon and 14-stitches in Thompson’s head.

Hank fought often with his wife and she eventually left him. “I guess I was mainly to blame,” he explained later. “I was drinking heavily.”

His skills and physical condition deteriorated. He missed an annoying number of games with a series of minor injuries. In 1956, he was out for a time after a serious beaning. By then he was almost through anyway. His batting average had sunk to .235—the fourth consecutive year it had dropped. Demoted to Minneapolis, he continued to waste and eventually quit in mid-season 1957. He was 31 years old.

Without an education, he drifted from job to job; occasionally driving a cab, most of the time hustling work doing what he knew best--as a bartender. Several times he was fired for taking money from the register. And he continued to commit felonious assault on his liver. He sold his 1954 World Series ring to a bar owner for drinking money.

There was a series of run-ins with the law; never planned capers, but usually alcohol-fueled spurious affairs. In 1958 he was arrested for auto theft. During a night of heavy drinking, unable to get his car out of a lot, he had taken another car from a Harlem public garage that had the keys in it. Later that night, at a party, he loaned the car to two friends. When they were picked up by the police, Thompson went to the station to clear them and was arrested himself.

In 1959 he was arrested for assault on a woman in New York City. While going through divorce proceedings, he had taken up with a married woman, Ruth Bowen, the wife of former Ink Spots singer Billy Bowen. When she showed up with a black eye after a drunken night of brawling, Hank spent a week in jail.

In 1961 he had his most serious brush with the law to date—for armed robbery. Thompson, who had been drinking heavily, entered a Harlem bar at 1:30 AM. It was a bar he had frequented in the past. He pulled a .22 pistol and announced, “This is a stickup. Put the money on the bar.” His haul was $37. He then herded the bartender and ten patrons to a rear room and fled. Unfortunately for Thompson, a patrolman nearby noticed him fleeing and, after a short chase and brief scuffle, arrested him. “You are a very serious disappointment to thousands of baseball fans in this city,” the judge told him at the bail hearing. Baseball commissioner Ford Frick and Giants owner Horace Stoneman wrote to the judge on Thompson’s behalf and he was given probation, escaping jail time.

After the bar hold up Stoneman gave him a job cleaning the swimming pool at the team’s spring training site in Arizona. It was a short-lived gig. With New York played out, Hank moved back to Texas in the early 1960s but his luck didn’t change.

In 1963 in Houston, drunk and needing money, Thompson held up a liquor store with a stolen gun. He made off with $90 but was quickly spotted by police. After his appearance in court, a contrite Thompson told a reporter he had made an estimated quarter of a million dollars in baseball in salary and endorsements but lost it all to “liquor and gold diggers.” He added “Tell those young fellows out there that have a chance to play big league baseball to keep the gold diggers away from their money.”

Hank was given a 10-year sentence. Hard time; in a place for hardened criminals. He was sent to Eastham, the turd of the Texas penal system. The rurally isolated complex in Houston County housed the rough cases. Back in the day, it had temporarily held a restless young man named Clyde Barrow. The prison profited from the prisoner-assisted harvest of the cotton plantation on the grounds. Prisoners who didn’t work hard were beaten or stuffed into tiny tin sweat boxes. The work was hot—Texas hot—days of 105 degrees. No wonder Barrow called the place, “that hell hole.” Things hadn’t change much over the decades. In 1986 Newsweek called Eastham “America’s Toughest Prison.”

But Hank Thompson was a model prisoner. After six months of what his supervisor called “exemplary behavior” he was transferred to the Ferguson Unit. Compared to Eastham, Ferguson, built in 1962 for less violent offenders, was a vacation paradise. Thompson was assigned to the rec department and, in time, made a trustee. His job was directing athletics for first-time offenders 17-21 years old. He joined alcoholics anonymous.

In 1965 he gave a prison interview for a Sport magazine article entitled, “How I wrecked my life and how I hope to save it.” He seemed to express genuine remorse. “I kicked society in the teeth and now I’m glad society is paying me back,” he said. “The only person for me to blame for being here is me. I’m in jail, not my father. Don’t ask me to blame society, or the fact that I’m a Negro in a white world. I blame drink. I’m the guy who did the drinking.”

He acknowledged that the road ahead would be difficult, but vowed to sick with AA on the outside and be a better man. “You might say the count on me is two strikes and I’ve only got one swing left.”

It would be nice to think that Hank Thompson kept his promise and turned his life around. And by all accounts, he did. He was released from prison early for good behavior in 1967. He moved to Fresno, California to be near his mother, got married and found a good job, playground director for the city rec department. His boss later said, “He did a tremendous job. He was dedicated and helped quite a few boys who could have gone wrong.”

He occasionally made his way down to San Francisco to watch his displaced old team, and visit his ex-teammate Willie Mays, a man whose career and life went another direction. He played in the 1969 old-timers game, his first time on a baseball field in years, and appeared to enjoy himself. He talked of getting a job in baseball.

In October, 1969 he suffered a seizure at home, was rushed to the hospital and never regained consciousness. His wife and mother were at his bedside when he passed away. The official report was natural causes, perhaps a heart attack. He was 43 years old.

Hank Thompson was a good baseball player, an important pioneer in integrating the game, a World Series hero and, maybe, a guy who learned from his mistakes and turned his life around. He quit school; he drank gin (though he much preferred Scotch whiskey); he lurked late and shot straight; and, whatever the hell it is, if it was a vice, he probably jazzed June.

He definitely died much too soon.

But he should be remembered.

Published on August 13, 2016 17:52

August 10, 2016

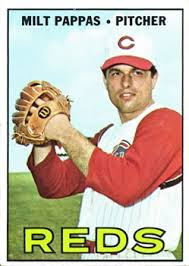

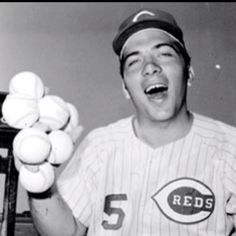

Milt Pappas: It Wasn't His Fault

Before we discuss anything else about Milt Pappas, know this: it wasn't his fault.

He couldn't help that the man for whom he was traded went on to hit 49 home runs, win the Triple Crown and MVP and lead his team to the World Championship--the very year of the trade. He was blameless that American League pitchers had no idea how to get Frank Robinson out. He was not culpable for the fact that Robinson played like a man on a mission to prove that his previous owner was an imbecile. He had nothing to do whatsoever with Robinson leading his new team to four pennants in six years. It just wasn't his fault. It really wasn't.

And yet . . .

When Milt Pappas passed away April 19 of this year, every single obituary carried some mention, usually in the first line, that he had been on the wrong side of one of the most infamous trades in baseball history.

ESPN.com: "Milt Pappas, the former All-Star pitcher who was part of the 1965 trade . . ."

New York Times: "Milt Pappas, a cagey righthander who won 209 games in his major league career, but whose most memorable, if unlucky, legacy is that he was traded for . . ."

Daily Herald: "Milt Pappas, who came within a disputed pitch of throwing a perfect game for the Chicago Cubs in 1972 and was part of the lopsided trade that . . ."

You get the idea.

It's sad. And unfair.

Milt Pappas was a very good major league baseball player and played a valuable roll in the early days of the players' union. He should be remembered for more than just his inclusion in a lousy trade.

Milt Pappas first appeared in a major league uniform at the age of 18 years, a cocky kid from Detroit with a smoking fastball and great command. He pitched in four games that year and came away with a cool 1.00 ERA. That first year he roomed with another teenager, Brooks Robinson, giving the team hope for the future, albeit in two peach-fuzzed guys not yet old enough to order a beer after games.

Pappas proceeded to became the most consistent pitcher for a team known for great pitching. In 1960, as the leader of Paul Richards' Baby Birds, he helped the Baltimore Orioles to their first winning season, and came within two weeks of pulling out a surprise pennant.

Pappas was reliable. Every year you could write him in for 15 or 16 wins--even when some of his teams were decidedly mediocre--and not be wrong. On a given day, he could beat any pitcher in the league head-to-head. He finished his career with a record of 209-164 and an ERA of 3.40. He was the first major leaguer to win 200 games without ever winning 20 in a season and he missed winning 100 games in each league by one (he won 99 National League games).

But the trade. We always have to talk about the trade. It was actually a six-player, three team swap. The Orioles sent Jackie Brandt to the Phillies for relief pitcher Jack Baldschun and first baseman Norm Siebern to the Angels for outfielder Dick Simpson, then packaged the two with Pappas to the Reds for Frank Robinson. There were reasons the Reds owner Bill DeWitt wanted to get rid of Robinson--too complicated to be listed here, but all of them tragically erroneous and misguided.

Part of the injustice is the general feeling among the public that Pappas somehow didn't play well and live up to his part of the trade. In fact, he did. Other than a little higher ERA, he was almost equally effective before and after the trade. In eight complete seasons before the trade, he won 110 games, an average of 13.75 a year. In eight seasons after the trade, he won 99, an average of 12.38. If you throw out his total of only seven wins in his last year (everyone has a lousy last year--that's why it's the last), he averaged 13.14 wins a season for the seven seasons after the trade.

So there was nothing wrong with Pappas; he came as advertised. The problem was entirely the responsibility of the nearsighted bumblers in the Reds front office who allowed themselves to be royally swindled. Of course Milt Pappas, and Dick Simpson (who retired with a .207 career batting average in parts of seven seasons), and Jack Baldschun (who won exactly one game for the Reds in 1966 and zero in 1967 before being released) were not worth a Frank Robinson. Any fan with a second-grade education could have told them that.

Pappas later said that he "hated every minute in Cincinnati." This was most prominently because of the pressure put on him by the front office, media and fans that increased with each American League home run Frank Robinson hit. The fact that Pappas' comrades in the trade, Simpson and Baldschun, did absolutely nothing seemed to be lost to history but further increased the feeling that the Reds got hosed. But there were also other causes of difficulty for Pappas in Cincinnati.

It can not be accurately said that Milt Pappas was well-liked by everyone. His extreme confidence on the mound, brutal honesty off it and unwillingness to back down when he felt he or others had been wronged had a propensity to anger fellow players and management types alike.

Despite the fact that he was intensely competitive during games and did not have a losing season until 1968 when he went 12-13, some teammates openly questioned his work ethic and desire, at the time a charge comparable to a gunslinger being called yellow in a Dodge City saloon--you'd better be reaching for iron when you said it.

Pappas had the reputation of a being a six or seven inning pitcher. Perfectly acceptable, even preferred nowadays, but scandalously close to being viewed as a slacker in the 1960s. The reason for this reputation was that Pappas had no problem speaking the truth late in a game when a manager asked how he felt. If Pappas was gassed and thought the bullpen had a better chance of pulling the game out, he said so. He reasoned why go out there trying to be John Wayne and pitch with an arrow through your heart and lose the game, when a fresh arm can come in and finish? This tendency contributed to him throwing fewer complete games than his contemporaries and kept his yearly innings-pitched totals around 220 each year, at a time when first-line starters were expected to go 275 or more. Maybe he was just ahead of his time, but it left him open to criticism.

When Pappas went to Vietnam on a goodwill tour with fellow players after the 1969 season, the joke that made the rounds went: Did you hear about Pappas leaving for Vietnam? He didn't make it, they had to take him out in San Francisco."

After the 1966 season, veteran Reds pitchers Jim O'Toole and Joe Nuxhall both complained to writers that they felt Pappas failed to give one-hundred percent. Pappas, who had opted out of a few scheduled starts with arm pain and sinus headaches, countered in the press that he didn't think he should jeopardize a team win by taking the mound when he didn't feel good and commented to the effect that losing pitchers (Nuxhall was 6-8, O'Toole 5-7) should not hurl invectives at winning pitchers (Pappas was 12-11).

Pappas was also criticized by management for counseling young sore-armed pitchers, of which the Reds seemed to lead the league every year, not to throw until their arms felt better. For this, he was treated like the lead writer for the Daily Worker.

Perhaps the number one reason Pappas was disliked by management was his work in the nascent players union. For the majority of his career, Pappas served as a team player rep, a position voted on by team members each spring. In an era when player reps were universally viewed as trouble makers, Pappas actually sought the position and held it for all four teams for which he played. While some player reps did little, Pappas took the job very seriously. He picked the brain of respected, committed veterans such as Robin Roberts, who was a teammate with the Orioles from 1962 to 1965 and who was instrumental in the hiring of Marvin Miller as chief of the union. He studied up on the issues and fully understood the stakes and the chance that baseball players of his generation had to make improvements for the future. Modern players owe their multimillion dollar contracts to pioneers like Pappas.

Player rep Pappas was a thinking man who did not hesitate to state his opinions and as such, was labeled as a clubhouse lawyer and even a team cancer. Player union boss Marvin Miller said of Pappas, "Milt is an extremely conscientious player representative," and noted that he attended more meetings with owners groups than any other player rep, often on his own time in the offseason.

Pappas later labeled the position "the most thankless job in baseball," yet he kept accepting it each year.

A big issue for the Reds in the summer of 1968 was the fact that the Reds management reneged on an agreement to seat players in first class on the team's trips, which were on commercial flights. Several Reds players, who were considerably larger than the average person, complained to Pappas that they were tired of squeezing next to yokels in cramped economy sections while the front office types, coaches, writers, and radio and television members enjoyed first class accommodations. As player rep Pappas took the complaint to the front office then, when nothing was done, to the press. For this he was roundly chastised by the media--a natural reaction when viewed with the fact that the Cincinnati Enquirer was owned by the Reds' majority owner at the time and frequently parroted the ownership position.

Soon thereafter, Pappas punched his ticket out of Cincy (and presumably it was coach, not first class). With the nation stunned by the assassination of Robert Kennedy in early June, 1968, baseball commissioner Eckert decried that the schedule be adjusted so that no games would be played during the funeral. When the funeral was delayed due to traffic problems associated with the funeral train's procession, the Reds-Cardinals game in Cincinnati, a 7 PM start, was in jeopardy.

Pappas felt strongly that the game should not be played. Manager Dave Bristol and general manager Bob Howsam were just as adamant that the game should go on. Howsam delivered a speech in the Reds clubhouse to the effect that Bobby Kennedy would have wanted the players to play the game. "Who is this guy anyway," Pappas later said to a reporter, "to tell us what Bobby Kennedy would have wanted us to do?" Pappas then stood up and argued passionately against playing. A team vote was taken and the players, some of whom were privately badgered by Bristol and Howsam, voted 13-12 in favor of playing. Pappas resigned as player rep and told reporters that he knew right then his days as a Reds were numbered.

As if on cue, he was traded to the Braves two days later (Howsam told reporters the clubhouse incident had nothing to do with it, but that a trade had been in the works for some time).

Pappas was traded from the Braves to the Cubs in 1970 and enjoyed several more good years, winning 17 games each in 1971 and 1972.

His finest moment, and most frustrating also, came September 2, 1972 against the Padres at Wrigley Field. After retiring the first 26 consecutive men he faced, Pappas went 0-2 on pinch-hitter Larry Stahl, then missed with three straight pitches. With the pay-off pitch, he threw a ball he thought caught a piece of the outside corner, however home-plate umpire Bruce Froemming called it a ball. Pappas is still the only man to lose a perfect game on a walk to the 27th batter. Had Froemming possessed a better understanding of the Greek words Pappas screamed from the mound, Pappas undoubtedly would have also been the first man tossed out of a perfect game after walking the 27th batter. As it was, he retired the next man on a popup and had a no-hitter.

While his account of how close the last pitch to Stahl had been varied over the years, Pappas remained adamant that on a two-out, ninth-inning, 3-2 pitch with a perfect game on the line, the pitcher should be given an inch, at least. It was a belief he took to his grave.

After retirement from baseball, living in the Chicago area, Pappas retained his love for the game and never shied away from talking about it, or from giving his honest opinions. He was noted to enjoy mixing with fans when recognized at Cubs games. He never turned down a request for an interview or an autograph.

I had the opportunity to talk to Milt Pappas on three occasions for various projects. He was very cooperative and friendly and seemed to genuinely enjoy talking about baseball and his career. It was obvious the game never lost its appeal for him. Once, he called me back late at night when he remembered a story he wanted me to know.

I was impressed that he and Brooks Robinson not only remained friends but corresponded regularly, even though it had been almost 50 years since they were teammates.

Pappas liked to tell one of my all-time favorite Ted Williams stories. Early in his major league career, the teenaged Pappas found himself on the mound, two outs in the first inning and staring in at Teddy Ballgame. Pappas carefully worked to a full count then, as a kid just cocky enough to be dangerous, threw his best fastball right down the middle. The Splendid Splinter watched the ball all the way into the catcher's mitt without moving his bat. Time froze as the catcher, umpire and pitcher all watched the great man for a reaction. Finally, Williams laid down his bat and started for the dugout. The umpire shot out his hand and yelled, "Strike three!" On his way to the dugout, Pappas detoured by home plate and asked the umpire, "What would you have called if he had started walking toward first base?"

"Then it would have been a ball," came the immediate reply. "His eyes are better than mine."

Milt Pappas, a man not afraid to stand up for his beliefs, even when they made him unpopular. And not a bad ballplayer either.

And remember, it wasn't his fault.

Published on August 10, 2016 11:35

August 3, 2016

Life Lessons From College Baseball II: Sociology, Geography and the Workings of the Human GI Tract

I have heard it said that school-sponsored athletic trips contribute greatly to the education process and I agree wholeheartedly. When I think back to the treks of our sadly underfunded Division II college baseball team, I realized that we learned about much more than baseball.

One of our most memorable trips was over spring break in 1982. We had spent the winter raising money ourselves and looked forward to traveling to the northern Florida coast to play games in the warm weather. Sun, beaches and baseball—what could be better? Well, apparently there was one other thing. The day before we left, the coach of the local Catholic high school dropped by to pick up the pitching machine our coach was loaning him to use while we were away. The Catholic coach was a robust man in his early thirties, with a thick chest and an impossible shock of dark hair exploding from the top of his two-sizes-too-small t-shirt. He had an unkempt mustache that hung down at the corners and made him look like a tobacco-chewing walrus. He listened impatiently as our coach talked about how excited we were to get down there and play baseball. He responded with a gruff voice between spits of brown juice, "If I was their age I know what I'd be wanting to get down there for. To look for some butt." Somehow, by a linguistic talent I had not heard before, he turned the last word into two syllables. Our coach, who never uttered a stouter word than crap, and aware that our young impressionable ears were nearby, quickly tried to overlook the comment, "Yeah, they're pretty tired of this miserable cold weather up here. They can't wait to get down there for some nice weather." "They can't wait to get down there to look for some bu-utt," came the immediate reply.

With great anticipation, of nice weather, baseball and other things, we loaded the vans in the cool early morning darkness. While some teams traveled in comfort on chartered busses, we rode in two ancient rusty vans, sitting on hard, cracked vinyl benches. There was a definite social order to the vans, although it was never spoken or written down. The first van, which I’ll call the “cool” van, was where the upper classmen and leaders of the team rode. The "other" van contained underclassmen, benchwarmers and the socially inept. I rode the other van.

Gino, one of the seniors Coach deemed responsible, usually drove the cool van. Coach drove our van. I tried to kid myself that he drove our van because the contents were so valuable that he wouldn't trust anyone else to drive, but I wasn't convinced. The cool van got to listen to our second baseman’s boom box—an enormous monstrosity of 1970s technology that allowed the user to carry his tunes wherever he went. The back of the boom box held enough D batteries to power a small third world republic and provided just enough energy to hear music for a few hours. They listened to the Eagles, the Rolling Stones and Journey. A great time was had in the cool van.

In our van we didn’t have music other than what could be pulled in from the small scratchy dashboard AM radio--which was often very little while traveling through rural cornfields. Instead, we listened to Coach play music trivia for hours: “Who sang King of the Road? Roger Miller.”

Before climbing in for the long trip to Florida, I overheard Coach tell Gino to be prepared for quick stops because, “I got the Raging Buttholes, I think I had a bad burrito last night.” While I had never heard of this nefarious malady before (or since), by the gravity of his tone, I surmised that it was significant and I considered myself lucky to pick up this little tidbit of info. I moved as far in the back of the van as possible and cracked the window.

Although none of us had seen the hideous hour of 5 AM before, spirits were incredibly high. As the two vans vied for the lead racing down the highway, we exchanged friendly hand gestures back and forth. Once as the vans passed, we witnessed everyone in their van frantically rolling down windows and waving their hats in the air. Everyone, that is, except our catcher, who had known gastrologic issues. He sat back with his hands behind his head and a satisfied smile on his face. We were all silently happy that we were in our own van at that point.

Chatter eventually died down and we drifted off to sleep, a difficult task in the cramped vans. Since there was no place to rest our heads, we would just close our eyes. As sleep arrived, this inevitably led to our heads haphazardly lolling from side to side or plunging straight down in a free fall that snapped out necks and brought laughter from those sitting behind.

The western Kentucky flatlands passed by in an oblivious blur of headsnapping slumber. When we stopped and unpiled at a Tennessee gas station, I heard one of the freshmen timidly mention to Coach that he thought he had left our bucket of baseballs--the only balls we had other than the dozen game balls under Coach's seat--sitting next to the gym door. The Tennessee hills echoed with an agonizing "CRAAAAP!" that sounded like an injured bear.

Coach's fragile psychologic state was saved when Gino ambled by and casually remarked that he had seen the bucket sitting there alone and stuck it in the back of his van.

After hours of watching the Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama countryside pass by, it was a big event when someone spotted the ocean in the distance. The sun seemed to grow in brilliance with each passing minute. Soon, the smell of saltwater and the fishy aroma of the beach increased our anticipation. We gawked at the beautiful high-rise beachfront hotels as we drove by, wondering which would be ours.

Our hearts fell when Coach slowed and instead of turning left into the pristine parking lots of the hotels on the beach, made a right, into the broken-asphalted, weed-strewn parking lot of a shabby motel with a low, uneven roof. The rusted sign in front with two missing lights announced it as The Tiki House, but Bucky, our center fielder, instantly dubbed it the Tiki-Dive.

Undaunted, we quickly recovered our excitement—we wouldn’t be spending much time in the motel anyway, we reasoned. We poured from the vans, got our keys and room assignments--four players to each tiny room--and quickly stored our stuff, anxious to hit the beach. Coach announced that we had two hours before we had to be back for dinner.

We made our way in a single file line through a dirty alley, along a narrow sand trail with large weeds on either side that pricked at our bare ankles and calves, crossed the street and walked between two nice hotels to the public beach access point. The beach was packed. Sunbathers glistened from blankets and people were splashing in the surf. We peeled our shirts, revealing pitiful ghost-white chests with baseball-tanned arms. We walked up the beach, allowing the ice-cold water to pour over our feet as we collectively pondered the next move. The possibilities were endless.

A long-haired bearded beach rat who looked like he had been in the same place since the sixties, spotted us, spread his arms wide and hollered, "What are you guys doing just standing there? You're wasting your time. Just look at all this skin."

Just then, as if ordered by Coach to save us from certain temptation, the heavens opened up and it began to pour. We quickly ran back to our safe haven, the Tiki-Dive, and waited.

And waited.

It rained non-stop for two days. We sat in our miserable, cramped, smelly rooms, playing cards or watching mindless game shows, occasionally risking an optimistic look out the window and making stupid jokes about building arks. After our first two days of games were washed out, we were elated when the rain finally stopped. We loaded our stuff into the vans and headed toward a local college where Coach said he was good friends with the coach there and he was sure the field would be in great shape.

The field looked like a swamp when we pulled up. There was standing water in several places in the infield and around the dugouts. Someone stepped into the mud of the on-deck circle and his foot sunk two inches, making a loud sucking noise when, with effort, he pulled his shoe out. I thought I saw an alligator floating in left field.

But Coach would not be denied. He picked up a rake and started frantically pawing at the infield dirt. He grabbed a wheelbarrow and lugged a couple of bags of Diamond Dry out and spread the contents around. Their coach, probably feeling sorry for these crazed northerners, finally agreed to play ball. As if by magic, the sun suddenly broke through the clouds and bathed us in all its glory. Someone in our dugout shouted, "Let's play two!" With great joy we scurried out on to the field, the misery of our lodgings and the weather totally forgotten. We were young, the sun was peeking through the clouds and we were playing baseball. Life couldn’t be better.

And then the other team came up to bat.

One of our most memorable trips was over spring break in 1982. We had spent the winter raising money ourselves and looked forward to traveling to the northern Florida coast to play games in the warm weather. Sun, beaches and baseball—what could be better? Well, apparently there was one other thing. The day before we left, the coach of the local Catholic high school dropped by to pick up the pitching machine our coach was loaning him to use while we were away. The Catholic coach was a robust man in his early thirties, with a thick chest and an impossible shock of dark hair exploding from the top of his two-sizes-too-small t-shirt. He had an unkempt mustache that hung down at the corners and made him look like a tobacco-chewing walrus. He listened impatiently as our coach talked about how excited we were to get down there and play baseball. He responded with a gruff voice between spits of brown juice, "If I was their age I know what I'd be wanting to get down there for. To look for some butt." Somehow, by a linguistic talent I had not heard before, he turned the last word into two syllables. Our coach, who never uttered a stouter word than crap, and aware that our young impressionable ears were nearby, quickly tried to overlook the comment, "Yeah, they're pretty tired of this miserable cold weather up here. They can't wait to get down there for some nice weather." "They can't wait to get down there to look for some bu-utt," came the immediate reply.

With great anticipation, of nice weather, baseball and other things, we loaded the vans in the cool early morning darkness. While some teams traveled in comfort on chartered busses, we rode in two ancient rusty vans, sitting on hard, cracked vinyl benches. There was a definite social order to the vans, although it was never spoken or written down. The first van, which I’ll call the “cool” van, was where the upper classmen and leaders of the team rode. The "other" van contained underclassmen, benchwarmers and the socially inept. I rode the other van.

Gino, one of the seniors Coach deemed responsible, usually drove the cool van. Coach drove our van. I tried to kid myself that he drove our van because the contents were so valuable that he wouldn't trust anyone else to drive, but I wasn't convinced. The cool van got to listen to our second baseman’s boom box—an enormous monstrosity of 1970s technology that allowed the user to carry his tunes wherever he went. The back of the boom box held enough D batteries to power a small third world republic and provided just enough energy to hear music for a few hours. They listened to the Eagles, the Rolling Stones and Journey. A great time was had in the cool van.

In our van we didn’t have music other than what could be pulled in from the small scratchy dashboard AM radio--which was often very little while traveling through rural cornfields. Instead, we listened to Coach play music trivia for hours: “Who sang King of the Road? Roger Miller.”

Before climbing in for the long trip to Florida, I overheard Coach tell Gino to be prepared for quick stops because, “I got the Raging Buttholes, I think I had a bad burrito last night.” While I had never heard of this nefarious malady before (or since), by the gravity of his tone, I surmised that it was significant and I considered myself lucky to pick up this little tidbit of info. I moved as far in the back of the van as possible and cracked the window.

Although none of us had seen the hideous hour of 5 AM before, spirits were incredibly high. As the two vans vied for the lead racing down the highway, we exchanged friendly hand gestures back and forth. Once as the vans passed, we witnessed everyone in their van frantically rolling down windows and waving their hats in the air. Everyone, that is, except our catcher, who had known gastrologic issues. He sat back with his hands behind his head and a satisfied smile on his face. We were all silently happy that we were in our own van at that point.

Chatter eventually died down and we drifted off to sleep, a difficult task in the cramped vans. Since there was no place to rest our heads, we would just close our eyes. As sleep arrived, this inevitably led to our heads haphazardly lolling from side to side or plunging straight down in a free fall that snapped out necks and brought laughter from those sitting behind.

The western Kentucky flatlands passed by in an oblivious blur of headsnapping slumber. When we stopped and unpiled at a Tennessee gas station, I heard one of the freshmen timidly mention to Coach that he thought he had left our bucket of baseballs--the only balls we had other than the dozen game balls under Coach's seat--sitting next to the gym door. The Tennessee hills echoed with an agonizing "CRAAAAP!" that sounded like an injured bear.

Coach's fragile psychologic state was saved when Gino ambled by and casually remarked that he had seen the bucket sitting there alone and stuck it in the back of his van.

After hours of watching the Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama countryside pass by, it was a big event when someone spotted the ocean in the distance. The sun seemed to grow in brilliance with each passing minute. Soon, the smell of saltwater and the fishy aroma of the beach increased our anticipation. We gawked at the beautiful high-rise beachfront hotels as we drove by, wondering which would be ours.

Our hearts fell when Coach slowed and instead of turning left into the pristine parking lots of the hotels on the beach, made a right, into the broken-asphalted, weed-strewn parking lot of a shabby motel with a low, uneven roof. The rusted sign in front with two missing lights announced it as The Tiki House, but Bucky, our center fielder, instantly dubbed it the Tiki-Dive.

Undaunted, we quickly recovered our excitement—we wouldn’t be spending much time in the motel anyway, we reasoned. We poured from the vans, got our keys and room assignments--four players to each tiny room--and quickly stored our stuff, anxious to hit the beach. Coach announced that we had two hours before we had to be back for dinner.

We made our way in a single file line through a dirty alley, along a narrow sand trail with large weeds on either side that pricked at our bare ankles and calves, crossed the street and walked between two nice hotels to the public beach access point. The beach was packed. Sunbathers glistened from blankets and people were splashing in the surf. We peeled our shirts, revealing pitiful ghost-white chests with baseball-tanned arms. We walked up the beach, allowing the ice-cold water to pour over our feet as we collectively pondered the next move. The possibilities were endless.

A long-haired bearded beach rat who looked like he had been in the same place since the sixties, spotted us, spread his arms wide and hollered, "What are you guys doing just standing there? You're wasting your time. Just look at all this skin."

Just then, as if ordered by Coach to save us from certain temptation, the heavens opened up and it began to pour. We quickly ran back to our safe haven, the Tiki-Dive, and waited.

And waited.

It rained non-stop for two days. We sat in our miserable, cramped, smelly rooms, playing cards or watching mindless game shows, occasionally risking an optimistic look out the window and making stupid jokes about building arks. After our first two days of games were washed out, we were elated when the rain finally stopped. We loaded our stuff into the vans and headed toward a local college where Coach said he was good friends with the coach there and he was sure the field would be in great shape.

The field looked like a swamp when we pulled up. There was standing water in several places in the infield and around the dugouts. Someone stepped into the mud of the on-deck circle and his foot sunk two inches, making a loud sucking noise when, with effort, he pulled his shoe out. I thought I saw an alligator floating in left field.

But Coach would not be denied. He picked up a rake and started frantically pawing at the infield dirt. He grabbed a wheelbarrow and lugged a couple of bags of Diamond Dry out and spread the contents around. Their coach, probably feeling sorry for these crazed northerners, finally agreed to play ball. As if by magic, the sun suddenly broke through the clouds and bathed us in all its glory. Someone in our dugout shouted, "Let's play two!" With great joy we scurried out on to the field, the misery of our lodgings and the weather totally forgotten. We were young, the sun was peeking through the clouds and we were playing baseball. Life couldn’t be better.

And then the other team came up to bat.

Published on August 03, 2016 16:51

July 30, 2016

The Curious Case of the Cubs College of Coaches

As the 2016 Chicago Cubs continue to charge furiously toward destiny, threatening to reverse more than a century of futility, now is a good time to look back at some of the team's history; to give modern fans a proper feel for the magnitude of the ineptness that has marked the franchise so they can fully appreciate the suffering and angst of older fans. One of the strangest episodes, and possibly the most revealing for those who don't believe in things like curses to explain a teams' perpetual failure, was the College of Coaches experiment.

The baseball world was stunned in January of 1961 when Chicago Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley announced that the club, in an unprecedented break from baseball tradition, would make their way through the coming season without a manager. Instead they would have a panel of coaches who would divide their time between the Cubs and their minor league farm teams and would furthermore take turns acting as head coach. The plan was given the ostentatious name “the College of Coaches.”

Like all great ideas, and a lot of terrible ones as well, this was not a precipitous decision; the stage had been set for over a decade. So many managers had jumped on and off the Cubs' carousel that vertigo was an accepted hazard for Cub fans.

Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch managed the team from 1949 to 1951. He was an irascible fellow, chronically dyspeptic because none of his charges could play the game nearly as well as he had. When he managed to alienate virtually all of his players by belittling their ability and being a chronic ill-tempered grouch he was let go in mid-season 1951.

Phil Cavaretta, a 35-year-old hometown hero, was then given the mantle. Cavaretta had been one of the franchise’s all-time best players, a key member of glory teams of the 1930s and early 1940s. A hard-charging, quick-tempered man who felt he could still play, he was nonetheless popular with his players and universally respected. Cavaretta’s fatal flaw was his preference for the truth. When he gave Wrigley an honest assessment of the team’s chances a few weeks before the opener of the 1954 season--that they didn’t have enough decent players to compete--he was summarily given the axe.

Wrigley then brought up Smiling Stan Hack, also a stalwart member of the glory teams, who had experienced a moderately successful three-year tenure at the helm of the Cubs’ AAA PCL team in Los Angeles. Hack lasted with the Cubs through the 1956 season, when he was shown the door with the public explanation that he had been too much of a nice guy to manage major league players.

Keeping to the time-honored owner play book, Wrigley replaced a nice guy with a tough guy. Disciplinarian Bob Scheffing was brought in and led the team to a slight improvement for three years. Scheffing’s mistake, apparently, was that he hadn’t clued his wife in on the expected decorum of the team and it’s owner. Scheffing was fired after the 1959 season and the rumor among the players was that his wife had said something at a team function, within earshot of Wrigley, about how poor the talent on the team was (this fact seemed to be apparent to everyone except Wrigley but no one was allowed to publicly state that the emperor had no clothes).

The year 1960 brought the Cubs management drama to new heights. Jolly Cholly Grimm, a good-timing oldster, generally credited with mismanaging the great Milwaukee Braves of Aaron, Mathews and Spahn out of a few pennants, took over. Grimm, as player-manager and later as just manager, had won pennants with the Cubs in 1932, 1935 and 1945--when the team contained an entire roster of legitimate major league ballplayers. After a 6-11 start in 1960, however, Wrigley traded Grimm to the broadcast booth for Lou Boudreau. A knowledgeable baseball man, generally credited as being a good manager, Boudreau could only forge a 54-83 record but was enthusiastic about the team’s future with newcomers Ron Santo and Billy Williams in the lineup. Unfortunately, Boudreau had the audacity to express his desire for the security of a two-year contract which was something Wrigley vehemently opposed on a matter of principle. They agreed amicably to part ways.

So if you’re keeping score at home, that’s six managers in ten years: four 7th place teams, two 8th (last) and zero first division finishes.

When an organization is either ridiculously successful or perennially unsuccessful, the cause is frequently found at the top and the Cubs were no different. Cubs owner P. K. Wrigley was, depending on who you talk to, either a benevolent, beloved old-school owner who deeply cared for his team or a blundering fool whose reliance on inept yes-men kept his team perpetually in the second division. While the actual truth may lie somewhere in between, the record of his teams speaks for itself. P. K. took over a highly successful baseball franchise after the death of his father in 1932. Legend has it that his father extracted a death-bed promise from P.K., who had never taken much interest in the Cubs before, to look after his beloved team and keep it in the family. After the well-stocked team won pennants in 1935, 1938 and 1945, the team’s fortunes plummeted.

There were those who said P. K. Wrigley did not particularly care for the game of baseball and pointed to the fact that he had not been seen at a game in decades. Wrigley’s supporters--mostly newspapermen who seemed to be on some kind of dole and Ernie Banks--reported that he indeed attended many games, but did so incognito—mixing in with regular crowd. The fact that he was never actually spotted in the stands, which often were so sparsely populated that players knew each paying customer by name, lends credence to the first theory.

Wrigley spared no expense on the maintenance of his namesake ballfield, but he expected the team to turn a profit on its own without help from the deep pockets of the Wrigley Chewing Gum empire. The fact that he regularly mismanaged the team’s finances--missing out on opportunities to make bundles of money on radio and television rights, virtually giving away the franchise territory to Los Angeles, which he owned with his PCL club, to Walter O’Malley and the Dodgers and wasting thousands of dollars on young bonus players who never panned out—made this difficult at best.

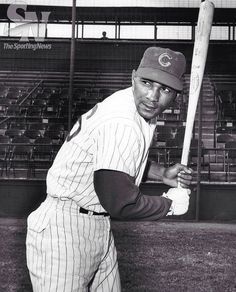

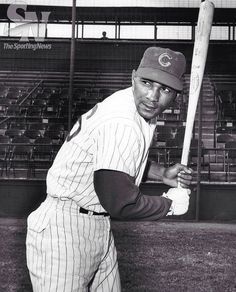

Wrigley’s Cubs had some good players at times, such as future Hall of Famers Billy Williams, Ron Santo and Ernie Banks, but never enough. He cut corners on the scouting department and virtually ignored his farm system. He picked up well-past-their-prime former stars on the cheap and rushed youngsters into the fray too quickly--then dumped them just as quickly for another crop. While that strategy kept the payroll down, it did little to help field competitive teams.

Wrigley never totally jettisoned anyone from his employment rolls except for those who committed the ultimate crime of being disloyal (read: disagreeing with the top man). Anyone he fired, no matter for whatever level of incompetence, was kept within the organization in another role. The result was a system overloaded with unproductive, inefficient men with little aptitude for winning. There was no direction or honest leadership to be found anywhere within the organization.

Wrigley liked to view himself as a nonconformist among baseball men, and he was definitely that. He also proclaimed himself to be an innovator, yet it took him seven years to join in the biggest major league innovation of the 20thcentury—the integration of baseball. In doing so, he and his scouts passed over dozens of very good ballplayers who could have been had cheap and who could have helped his miserable team, merely because they had the wrong color skin.

Wrigley attempted to camouflage the horrendous lack of talent and organization with hokey ideas and flowery speech about the family experience of a trip to his beautiful ball park—but these tactics were little more effective than the layers of paint he regularly bestowed on the Wrigley Field bathroom walls.

Wrigley preferred to portray himself as media-shy, yet he himself was quoted in newspapers with more regularity than any of his players or staff and he frequently seemed to come up with ideas just for publicity sake. And so it was with great fanfare that a Wrigley-lead news conference introduced the grand plan for 1961. Wrigley even went so far as to release to the press a 21-page booklet explaining the team’s philosophy in detail, comparing it to modern business-management practices. He pronounced that after 14 consecutive years in the second division, he wanted to take full advantage of every possible means to improve the Cubs.

After losing Boudreau during the 1960 postseason, Wrigley had met with his top men to formulate a new strategy. Historians would later credit 32-year-old part-time backup catcher and coach Elvin Tappe, a Wrigley favorite, with the origins of the College of Coaches. While Tappe agreed that he had suggested a panel of coaches, for unified coaching throughout the system, he would go to his grave denying that he had anything to do with the lack of a manager and the rotating head coach part of the plan. That was all P.K.'s baby.

Wrigley had always detested the term “manager” for some reason. For years he had referred to his chief of baseball operations (called General Manager everywhere else) by every term other than General Manager. He went to great length to avoid the M-word. He told the press that he had looked up the word in the dictionary and the closest synonym was dictator. “We don’t need a dictator,” he explained.

“Since we’ve attempted just about everything else possible trying to improve our lot, I think the time has come to assemble the soldiers and sergeants before turning them over to a brand-new general.”Wrigley stated that he had tried all kinds of personalities as manager for his team, “every type of manager from inspirational leader to slave driver,” and he had come to the conclusion that no single manager would work.

“Managers are expendable. I believe there should be relief managers just like relief pitchers.”Wrigley announced that henceforth the word manager would be taboo under his new system. Coaches or supervisor would be the preferred verbiage.

Everyone on the executive team bought into the system and enthusiastically promoted it to the press. “We couldn’t hire a Durocher or Stanky, although they’re good baseball men,” said vice president John Holland. “We didn’t want the type of guy who wants it done his way or else. We needed harmony, men who can be overruled and not take it personally.”

One of the big ideas of the College of Coaches was continuity in the way the game was taught throughout the system. “If we bring a young pitcher up from San Antonio at mid-season, we won’t have to teach him how we work our pickoff play," said Charlie Grimm, a senior member of Wrigley’s inner circle. "He’ll know. It’ll be the same one he’s been using all season.” Bunt defense, curve balls and hitting approach would be taught the same way in Class A ball as in the majors--a very sane idea and something that teams such as the Dodgers and Cardinals had been doing for years.

But not content to merely stop with coaches teaching the same system, Wrigley insisted that the key tenant of the new plan was that there would be no manager. A rotating team of coaches would take turns being the "Head Coach." He did not offer, and apparently there was no set plan for, what the criteria would be for who the head coach would be on any given day and when a change would be made.

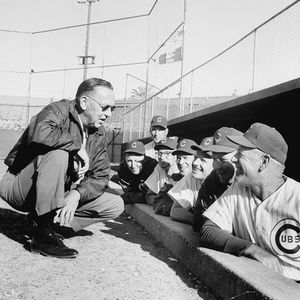

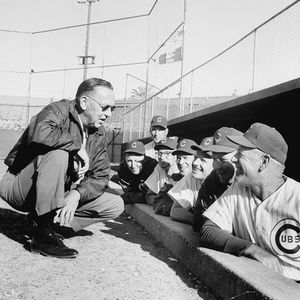

The College of Coaches for 1961 included Elvin Tappe, Harry Craft, Vedie Himsl, Rip Collins, Goldie Holt, Charlie Grimm, Verlon Walker and Bobby Adams. Most had been long-term members of the Cubs system at various levels.

The coaches were all supposed to have equal authority and equal importance. Each coach had a specialty such as pitching, hitting, first base, infield or outfield. Four would always be with the Cubs, the other four would circulate through the farm system. During the season every coach would spend some time with the Cubs.

As with any novel idea that breaks with tradition, Wrigley’s project was met with skepticism. With almost a century of well-established practice patterns to back them up, critics opened fire mercilessly. The national press enjoyed much mirth at the Cubs’ expense. One wag suggested that “The Cubs have been playing without players for years. Now they’re going to try it without a manager.” The coaches were called "the enigmatic eight" and the team was labeled “the unmanagables." It was said that the reason the Cubs went with eight coaches is so there would be more room to spread out the blame for their inevitable failure. Rumors circulated that Wrigley was going to install a rotisserie at Wrigley Field to keep the revolving coaches hot.

One sports editor penned, “Not since the legendary Headless Horsemen of Sleepy Hollow has there been a decapitated phenomenon like the Chicago Cubs are going to present in major league baseball this season.”

Jim Murray, veteran writer for the L.A. Times, wrote, “The Cubs are less of a team than a comic-opera in baseball suits. They have more generals and less troops than a South American revolution. They come to a game like a bull to the plaza; the best they can hope is that someone doesn’t cut off their ears.”

And so it was in a state of nervous expectation that Chicagoland fans watched as the 1961 Cubs took the field.

Vedie Himsl, a labeled pitching expert, opened the season as head coach and lasted all of two weeks. April 23, after guiding the team to a 5-4 record, he was dispatched and found himself teaching pitching in Wenatchee, Washington, home of the Cubs Class B team.

Harry Craft, Lou Klein and Elvin Tappe then took their turns as the head man and Himsl returned later for another try. No reason was given as to why the other four did not get a chance as head coach. The results were somewhat underwhelming to say the least. The 1961 Chicago Cubs had five future Hall of Famers on their roster: Banks, who hit 29 home runs (his first season below 40 since 1956), Santo, who had 23 home runs and 83 RBIs, Williams, who hit 25 home runs and 86 RBIs, an aging Richie Ashburn who hit .257 in 109 games, and a young Lou Brock, who only appeared in a few games but would make a bigger splash in 1962, but won only 64 games and lost 90 and finished in 7th place (out of 8 teams). Himsl was 10-21, Craft 7-9, Tappe 42-54 and Klein 5-6.

Banks, the best all-around shortstop baseball had ever seen to that point, began experiencing severe knee problems in 1961. One coach moved him to left field for 23 games (an experiment that he detested privately, but publicly endured without complaint), another preferred to see him limping around at shortstop and another played him at first base, a position that would become his home the rest of his career.

George Altman had a great year with 27 home runs and 96 RBIs and a .303 average, but played four different positions and sometimes was not in the lineup at all as a few of the coaches did not apparently appreciate his talent or know where to play him. The team's top-winning pitcher, Don Cardwell, who won 15 games, commented to Holland at the end of the season that he didn't like the rotating coach system and he was traded, along with Altman in 1962.

In short, the College of Coaches was a disaster. Players, who had been skeptical at the start, rapidly learned that the system was killing the team. There was a tremendous void of leadership—in the dugout and in the clubhouse. Several of the coaches were good baseball men, but nobody, absolutely nobody, knew who was in charge. Because nobody was.

Confused players were told one thing by one coach and another by a different one; no one knew who to listen to or believe. When the head coach changed, players did not know where they stood with the new guy—their status changed without explanation or cause. They never knew where they stood. One guy could like them, the next might put them on the bench or move them to a new position.

The coaches were noted to become territorial and defensive, suspicious of undermining by others. Players noticed that some coaches did absolutely nothing to help the current head coach, but merely watched until their turn came. Others openly stabbed their fellow coaches in the back. Rather than everyone working within the same system and philosophy, there was no cohesiveness. And no one knew how or why or when the head coaching job would change hands.