Doug Wilson's Blog, page 4

May 20, 2017

The Ballad of Mr. Cub and Leo the Lip

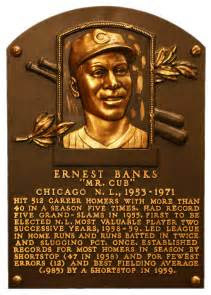

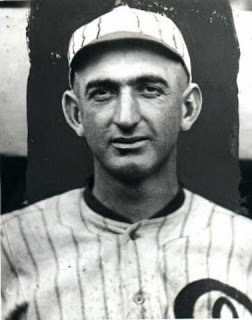

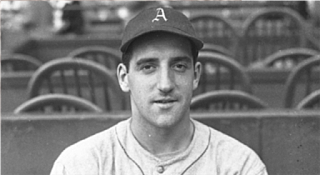

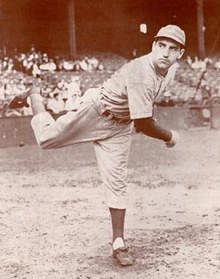

It was one of the most intriguing matchups in baseball history. Ernie Banks and Leo Durocher--thrown together in the same clubhouse. Rarely have two more disparate characters been coupled outside of a lousy television sitcom. Smiling Ernie Banks, the perpetually glass-is-half-full line drive of sunshine; a man so outrageously optimistic that he actually claimed the Cubs had a chance each spring when everyone else in the western hemisphere knew otherwise; but a man unable to lift his team out of mediocrity, no matter how brilliantly he played. Leo Durocher, the consummate tough-talking, rule-bending, angle-playing wise guy, who never hesitated to break any person in his way; a man summoned to Chicago to try to rescue a moribund franchise.

While Ernie was loved by millions and, except for a few ex-wives, liked by virtually everyone else, Leo was . . . well, I’m sure he must have once had a dog who acted like he liked him at dinner time.

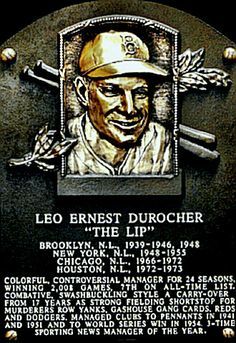

Before he arrived in Chicago, Leo Durocher was already a baseball legend, an outsized caricature who dominated every scene by sheer force of personality. His baseball career had started with the Yankees of the late 1920s where as a hustling, under-talented shortstop, he famously had trouble getting along with Babe Ruth, who called him “the all-American out.” And he either did or did not steal the Babe’s watch, depending on whose version you're willing to believe. As a manager Leo had taken over losing teams in Brooklyn and New York and turned both into pennant winners.Possessing a voice with the commanding ring of a Marine drill sergeant and a snarl savage enough to give even the toughest of badasses pause, Leo could captivate a group of men like few others. Learning at an early age that yelling was the way for him to get the upper hand in life, he had an explosive temper that begged for anger management therapy.Durocher routinely used every vile invective and slur against both his players and opponents. Jews were Kikes, Italians were Dagos, and Blacks were, well, called much worse. And according to the grammatical rules Leo preferred, the slurs were most often used as adjectives, surrounded by other less-than-endearing terms, such as when he often referred to pitcher Ken Holtzman--to his face and in front of teammates--as a “gutless Kike bastard.”But it could not be accurately said that Leo was racist. He hated everyone equally--regardless of race, religion or belief--who stood between him and victory. He had taken a stand for Jackie Robinson during Jackie’s first spring with the Dodgers, telling a late-night meeting of the team, “I’ll play an elephant if he can do the job, and to make room for him I’ll send my own brother home.” With the Giants he had been a father figure to Willie Mays who adored him.Leo never lacked for enthusiasm, especially when there was a microphone in his face or a photographer nearby. While he loved publicity in general, he hated media members personally. For their part writers uniformly despised the man, but loved the fact that he was in their city; if nothing else, he was always good for easy copy.As a player and manager Leo Durocher was a master of the dark arts of baseball. Flinging dirt in infielders faces, kicking balls out of their gloves, stealing signs, beanballs, intimidation, nothing was too much if it helped him win a game. He would say virtually anything from the dugout to give his team an edge. When he yelled to his pitcher from the dugout, “Stick one in his ear,” no one doubted that he meant it with all his heart. No fan of sportsmanship, Leo said “Show me a good loser in professional sports, and I’ll show you an idiot.” And, “I believe in rules. Sure I do, if there weren’t any rules, how could you break them?” He wanted “scratching, diving, hungry ballplayers who come to kill you,” on his team. He freely admitted that if his mother was rounding third with the winning run he would trip her—but just to show that he did have a heart, he added that he would pick the old lady up and brush her off afterwards.

But few men could get more out of a team than Leo Durocher. While he knew baseball and knew how to win, he was extremely hard on his players. For those who won his approval, who showed their toughness through fire, they were his guys for life, or until the next loss. Only a certain type of ballplayer, with a certain tough hide, could play for Leo Durocher. His past was littered with the carcasses of players for whom he had no use; men he had broken. He loved letting his team know that no one’s job was secure, no matter the past. His favorite expression was to “back up the truck” as in loading up all the unwanted players and carting them away.Brutally frank and decisive, if Leo ever had a doubt about anything he did, he never showed it. Confidence exuded from his pores and enveloped him like a bad cologne. He was absolutely certain deep in his heart that there was no man whom he couldn’t bluff out of a pot while holding a hand full of nothing and there was no dame he couldn’t talk out of her pants with a few well-chosen words and a fist full of charm.

Although Leo had not managed a baseball team since 1955 he had remained very much in the public eye by coaching, commentating on televised games and being a general celebrity. He was perhaps the only man who could boast of achieving the 1960s cultural trifecta of appearing on the Mr. Ed, Munsters and Beverly Hillbillies television shows (as himself of course). When Fred Flintstone was wooed by a no-nonsense big league manager named Leo Ferocious of the Boulder City Giants, no one doubted who the cartoon character represented.

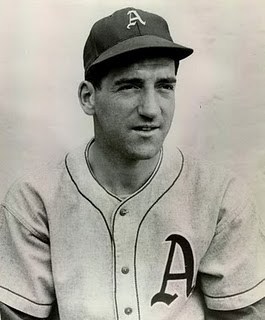

Ernie Banks was in many ways the polar opposite of Leo Durocher, exactly the kind of nice guy Leo famously said finished last. While Leo spent a lifetime refining how to get what he wanted by climbing in faces and forcing uncomfortable situations, Ernie was a walking conflict-avoidance seminar. He was constitutionally, almost pathologically, unable to have a forceful face-to-face disagreement with another human being. Want to know the essence of Ernie Banks: a 1967 clubhouse encounter with teammate Ron Santo tells you all you need to know. Santo played with Banks for more than a decade and knew him as well as anyone, which is to say he didn’t have a clue what made the man tick. When the hot-headed Santo entered the clubhouse the day after a tough loss and flew into a tirade, Ernie calmly pleaded, “Don’t let the past influence the present."

Santo turned on Banks and exploded, “What the hell’s wrong with you? You like losing?”

Ernie merely walked away while saying something about it being a lovely day—the fact that it was cloudy and drizzling at the time did not matter—and that it was time to “beat the Pirates, beat the Pirates.” That day, the Cubs did beat the Pirates, winning 8-4 and Ernie’s two doubles and Santo’s home run accounted for four RBIs.

Avoidance of conflict, avoidance of controversy, show the world only happy thoughts, put a positive spin on virtually everything; this was the protective hard-shelled candy coating in which Ernie Banks had successfully encased himself. It was a philosophy born of a combination of the optimism of Ernie’s Negro League manager, Buck O’Neil, and the ultraconservative don’t-ever-show-anybody-what-you-really-think and, above all, don’t-stand-out, Ernie’s father preached as a way to survive the uncompromising Jim Crow life of Dallas in the 1930s and 1940s.

It was a seemingly simple aura of smiling optimism and it worked well for Ernie. But was it the real Ernie Banks? We’ll never know, because he never told. Even those closest to him were never able to penetrate the candy coating. Few people, if any, ever knew the true Ernie Banks.

And where Leo loved talking to the media about himself, Ernie could not be forced to talk about himself by any means. Unfailingly polite with the media, he would hold forth at length spouting his well-worn clichés and meaningless optimistic proclamations and at the end of a half hour, the writer would have absolutely nothing. Even when young Ernie was copping consecutive MVP awards in the late ‘50s, writers approaching him for a personal story would come away with only, “Yessir, yessir, quite an honor to be included with these guys. That Willie Mays, what a great player. And, my, Henry Aaron. What a fantastic year he had.”

By the mid-1960s Ernie had perfected a smiling two-step whenever a writer got too close: “Thank you, thank you, it’s a beautiful day for baseball here at the friendly confines,” he would say while walking the writer to the other side of the clubhouse. “And the guys you want to talk to are right here, Donnie Kessinger and Glenn Beckert. Two of the next stars. The best young double play combo in baseball.” And when the writer turned around, Ernie would have vanished. It was a polished, seemingly effortless, shtick and always left Ernie looking like a good guy, while both giving young players some exposure and saving Ernie from any truly prying questions.

By 1966 Ernie had been in Chicago a dozen years, the face of the franchise, not only a perennial All-Star but recognized as one of the game’s great gentlemen off the field. He never turned down a request for an autograph or a speaking engagement, often appearing gratis at Little League banquets and the like throughout the upper Midwest. He had a rare moral compass that refused to allow any public perception of trouble. Through all the losing years he never said a bad word about management. Ernie was the ultimate organization man for a team without organization. When he began to be referred to publicly as Mr. Cub in the early 1960s, no one disagreed. Banks had been one of baseball’s top hitters, hitting more home runs between 1955 and 1960 than anyone in the game. Although never out of shape, still retaining the thin frame that impossibly launched all those home runs, Ernie had not aged well. Chronic knee problems and a variety of other ailments had cut his production and forced a move from shortstop to first base in 1961. By 1966 Banks visibly hobbled at times on the field and in the dugout.

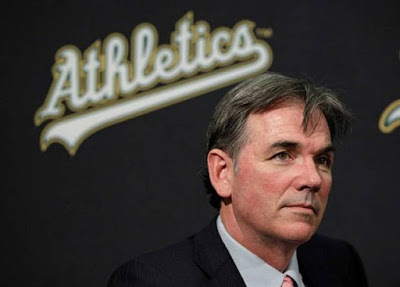

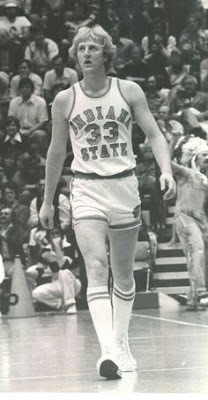

By 1966 Ernie had been in Chicago a dozen years, the face of the franchise, not only a perennial All-Star but recognized as one of the game’s great gentlemen off the field. He never turned down a request for an autograph or a speaking engagement, often appearing gratis at Little League banquets and the like throughout the upper Midwest. He had a rare moral compass that refused to allow any public perception of trouble. Through all the losing years he never said a bad word about management. Ernie was the ultimate organization man for a team without organization. When he began to be referred to publicly as Mr. Cub in the early 1960s, no one disagreed. Banks had been one of baseball’s top hitters, hitting more home runs between 1955 and 1960 than anyone in the game. Although never out of shape, still retaining the thin frame that impossibly launched all those home runs, Ernie had not aged well. Chronic knee problems and a variety of other ailments had cut his production and forced a move from shortstop to first base in 1961. By 1966 Banks visibly hobbled at times on the field and in the dugout.Leo Durocher, at 59, was still very much an energetic, dynamic, forceful, dominating personality when he was hired to manage the Cubs for the 1966 season. He was the alpha male of all he surveyed. Leo’s impact on the windy city was both immediate and seismic. The Cubs were fresh off four years of PK Wrigley’s ridiculous College of Coaches experiment and had not finished above 7th place since 1959. “I’m not a nice guy,” Leo said at his Chicago unveiling in October 1965. In case anyone was wondering, he added, “I’m still the same SOB I always was.”

“Pitching, defense and speed, that’s the kind of ball club I like,” pronounced Durocher that day. “And that’s what I’m going to be working toward with the Cubs. Hit and run, bunt, steal. You can’t win with those big slow-footed guys even if they do hit one out of the park for you once in a while.”Initially Durocher said, “As for Banks, he comes with the franchise and I’m glad to have him on my side for a change.” But anyone with even remote knowledge of the game could see that Leo obviously had other plans for the slow-footed first baseman who could no longer run, bunt or steal.

Shortly after taking over the Giants in 1949, as part of his master plan that would produce two pennants and a world championship within five years, Leo had traded thirty-something year old All-Stars Johnny Mize and Walker Cooper--less than two years removed from combining for 86 home runs—peddling them to open space on the team for the kind of guys he liked. He wanted to do something similar in Chicago and there was one big unavoidable target: Mr. Banks.

Durocher initially talked of trading Banks to the Giants for Orlando Cepeda, but he quickly learned what every other manager, director of player personnel and general manager (whatever Wrigley’s title de jour for them was) had learned: the chances of PK Wrigley agreeing to any trade involving Ernie Banks depended entirely on the weather—just in case Hell did freeze over . . .

Since Leo could not trade Ernie, he did the next best thing: he began to hate him and plotted a way to shame him off the field. Leo was merciless in pointing out Banks’ deficiencies to both Ernie and anyone who would listen. He constantly harped on Ernie’s lack of speed and publicly called him a “rally killer.”

“Mr. Cub, my ass,” he told reporters. “I’ll give Mr. Cub $100 anytime he even attempts to steal second.”[editors note: for the record Ernie Banks stole 4 bases in 7 attempts in the 6 seasons he played for Leo; it was never noted if Leo actually ponied up the $700].

Pitcher Fergie Jenkins later wrote, “One thing that drove Durocher nuts was that, at that point in Ernie’s career, when he was 35 or 36 years old, you didn’t have to be Einstein to know he wasn’t going to steal any bases. So Ernie took tiny leads off first base, like three inches. He wasn’t going to steal, and he sure as heck wasn’t going to let himself get picked off. Durocher screamed to the first-base coach, ‘Get him off! Get him off!’ Meaning he wanted him to make Ernie take a bigger lead so if someone got a hit he might make it to third base safely. That went on the whole year. The rest of us, sitting on the bench, watching and listening, just wanted to turn to Leo and say, ‘Give it a rest.’ But nobody did that. Ernie was just the greatest guy. He was a lot of fun to be with. He always talked when he was in the field. He was always bubbly and great to be around. Durocher seemed to be the only person on planet Earth who had trouble getting along with Ernie Banks.”

In Leo’s defense, inheriting an aging star is one of the least pleasant tasks for a new manager—a political and managerial quicksand for any polite leader concerned with social etiquette (see Stengel/DiMaggio). And Leo was never accused of politeness or social etiquette.

Also Leo loved to play amateur psychologist. No one had ever gotten on Banks before. Leo was making a statement to the entire team that no one was above reproach.

Others have hinted at more sinister motives: “He disliked Ernie from the go,” wrote longtime Cubs announcer Jack Brickhouse, himself no great Durocher fan. “It was just that Ernie was too big a name in Chicago to suit Durocher.”

While Leo grudgingly conceded that Ernie Banks had been a great player in his time,“Unfortunately, his time wasn’t my time,” he later wrote. “He couldn’t run, he couldn’t field; toward the end, he couldn’t even hit. . . . As a player, by the time I got there, there was nothing wrong with Ernie that two new knees wouldn’t have cured. He’d come up with men on the bases and if he hit a ground ball they could walk through the double play. . . . I’ve got to have somebody there who can play. Balls are going by there this far that should be outs or double plays. . . But I had to play him. Had to play the man or there would have been a revolution in the street. Ernie Banks owns Chicago.”

Leo was mystified at the goodwill Ernie had built up in the city and did not buy into his act. “How does he do it? You could say about Ernie that he never remembered a sign or forgot a newspaperman’s name. All he knew was, ‘Ho, let’s go. Ho, babydoobedoobedoo. It’s a wonderful day for a game in Chicago. Let’s play twooo.’ We’d get on the bus and he’d sit across from the writers. ‘A beaooootiful day for twoooo.’ It could be snowing outside, ‘Let’s play three.’”

Whatever the motive, the opportunity Leo hoped for arrived soon. In mid-May, 1966, with Banks hitting .188, the Cubs traded pitcher Ted Abernathy to the Braves for first baseman-outfielder Lee Thomas. “I’m going to him [Thomas] every chance to play regularly at first base,” Durocher announced to the press. “Ernie Banks hasn’t done it for me, so I’m going to give Lee every chance to show me.”Durocher made the peculiar move of shuffling Ron Santo to shortstop and putting Ernie at third base and Thomas at first—an ill-conceived experiment that weakened all three positions and lasted a mere four days. Then he benched Ernie and gave first base to Thomas outright.

But Thomas failed to cooperate with Leo’s plan. In early June, with Thomas hitting .200, Ernie was back as the regular first baseman and he launched an 8-game hitting streak. June 11, the old man legged out three triples in a game—all pokes to right field. But the slump returned. In early July Durocher announced that Banks was benched again—this time for powerful youngster John Boccabella, who had hit 30 homers in the minors in 1965. With the Cubs locked in the cellar, Durocher added, “The future of this team has to be with the young fellows.” The unmistakable message was that Banks was officially over the hill and finished.

Reporters wrote that Banks took the news with “Impeccably good grace. He has the unfailing gift of always saying the right thing.” Among the “right things” they quoted Ernie with saying was, “There comes a time in every player’s life when he must face up to this sort of thing. As we get older, we have to make way for the younger players. . . . I won’t say it doesn’t hurt because it definitely does. However, I simply have to adjust to it.”

But Boccabella failed to hit and once again, before the last shovel-full of dirt could be tossed on his grave, Ernie came back. From the All-Star game to August 11, over a five-week period, he hit .359 (37-103). He ended the season with a mediocre 15 homers, 75 RBIs and a .272 batting average for the last place, 59-103 Cubs.

All winter Leo said he was sticking with the youth movement, adding that Boccobella would be given a full shot at first. At one ceremony, Leo called Banks “Grandpa.” Liking the way it sounded, Leo used the term liberally throughout the winter.

And the offseason gave Leo time to think of a new strategy to deal with his unwanted aging star. February 28, 1967, Leo announced that Ernie Banks had been named to the Cubs’ coaching staff: “Banks will do a lot of playing for us, the only difference is that Ernie now will be able to teach our kids. He’ll have as much authority as any of the other four coaches.”

The move was a complete surprise, and Banks seemed more surprised than anyone else. It immediately led to open speculation and interpretation: was it was the beginning of the climb up the corporate ladder for Banks or was it a public relations move by Durocher to keep Banks on the bench. Durocher, sensing everyone’s suspicion, stated that this shouldn’t be construed in any way as a move to end Banks’ playing career. He added that Ernie still had a chance to fight off Boccabella for first base playing time. The tone left little doubt that the job appeared to be Boccabella’s to lose. For his part, Ernie smiled, noted that he would become just the fourth African-American major league coach (behind Buck O’Neil, Gene Baker and Junior Gilliam) and said, “It’s all very gratifying.”

Leo played Boccabella, Clarence Jones, Norm Gigon and Lee Thomas at first all through the spring, along with feeding rumors of other first base candidates being brought in by trades. Banks didn’t get any regular playing time until about 10 days before the exhibition season was over even as the mythical coaching duties never seemed to materialize.

While Ernie hit ropes in the batting cage, Leo acted like he didn’t notice, raving instead about the young prospects. When writers ventured that Banks was being ignored, Leo snarled, “Why don’t you knock off that Mr. Cub stuff? The guy’s wearing out. He can’t go on forever.”

It became a running gag in the press box, whenever Banks hit a home run or knocked in a key run: “Do you think Durocher will acknowledge that?”

Despite the near daily criticism and indications that he was through, outwardly Banks seemed exactly the same to observers. He never let on that it was anything other than another routine, glorious spring training in the sun. He showed up every day with a smile on his face, singing to pregame music, welcoming one and all to the park and cheering opposing teams through their calisthenics. Then he would get into the cage and flick line drives with his still-magnificent wrists.

Near the end of the spring, when Ernie was hitting .419, Leo conceded that the first base job probably belonged to him. Except for two second games of doubleheaders, Leo wrote “Banks” on the lineup card every game from April 28 to June 20. Ernie got off to his best first half since the MVP season of 1959 and made the All-Star team.

Leo Durocher delivered for the Cubs the way he had promised. Two decades of futility were laid to rest as the Cubs took over first place in July, 1967 for the first time since 1945. They finished the season in third place—their first time in the first division in 21 years. Ernie played in 151 games in 1967, finishing with 23 homers and 94 RBIs, second on the team to Santo’s 98 and second among league first basemen.

Reporters, eager for a good winter-time story, kept giving Banks chances to rub his success in Leo’s face, unmistakably teeing up leading questions. But Ernie steadfastly left the bat on his shoulder. In fact, in an act similar to happily digging through a pile of manure looking for a horse, he gave Leo credit for the good season. All that time on the bench in the spring, Ernie explained with a smile, had been the plan all along to allow him to get ready on his own, to take his time getting in shape. “That undoubtedly was a good break for me, because if I had tried to compete with the young fellows, I would have been struggling, really struggling. . . . [when the time to play came] I was ready.”It was an explanation Ernie repeated numerous times all through the fall and winter, leaving incredulous writers to question their sanity.

Reporters, eager for a good winter-time story, kept giving Banks chances to rub his success in Leo’s face, unmistakably teeing up leading questions. But Ernie steadfastly left the bat on his shoulder. In fact, in an act similar to happily digging through a pile of manure looking for a horse, he gave Leo credit for the good season. All that time on the bench in the spring, Ernie explained with a smile, had been the plan all along to allow him to get ready on his own, to take his time getting in shape. “That undoubtedly was a good break for me, because if I had tried to compete with the young fellows, I would have been struggling, really struggling. . . . [when the time to play came] I was ready.”It was an explanation Ernie repeated numerous times all through the fall and winter, leaving incredulous writers to question their sanity.The pattern quieted the next two years as Ernie got off to hot starts and showed that, while he couldn’t run, he could still drive in teammates. In the notoriously tough pitcher’s year of 1968, Ernie was second in the league with 32 home runs and his hot hitting helped the Cubs jump out to a big lead in 1969 as he ended up with 106 RBIs.

By 1970, however, Ernie’s body was just about ready for the glue factory. His knees were so swollen and achy that some days he could barely walk. The final countdown is difficult with any aged star and Ernie’s was no less painful, for him or his manager. Their relationship deteriorated as a familiar pattern played out: Leo would watch Ernie limping through the clubhouse and ask the trainer who would tell him that Ernie couldn't play and Leo would write him out of the lineup. Reporters would go to Ernie and he would say he felt fine. They would ask him why he didn’t play and Ernie would shrug and say, "The man says I play, I play.” They would then write that Durocher had benched Banks for no reason and fans would complain. Durocher felt that Ernie was betraying him with passive-aggressive behavior.

May 4, 1971 against the Mets, Ernie suffered the indignity all geriatric stars eventually face: he was removed for a pinch-hitter in a clutch situation. Teammates felt Leo humiliated Banks by allowing him to face Nolan Ryan three times, only to pinch-hit for him with right-handed batter Jim Hickman when lefty Ray Sadecki was on the mound in the eighth inning with men on first and third, trailing 2-1 . Ernie was in the ondeck circle when he unexpectedly saw the shadow of Hickman approaching. Hickman sheepishly told him, “I gotta hit for you.” Banks nodded without emotion, walked back, put his bat in the rack slowly and sat down on the bench—right next to Leo. He never said a word.

“Hickman told me later it was one of the toughest things he ever had to do,” wrote Brickhouse.

Ernie retired as a player after the 1971 season, but owner Wrigley kept him on the Cubs as a coach for 1972, against Leo’s wishes. By that time the Cubs’ pennant chances were in sharp decline. As the team struggled, amid speculation that Leo would be replaced, tempers flared, leading to a famous clubhouse explosion involving Leo, Milt Pappas, Joe Pepitone and Ron Santo. Afterwards Leo stormed out and threatened to quit. Ernie and coach Joey Amalfitano went to his office and tried to talk Durocher into staying. According to Durocher, Ernie told him, “Please Leo, don’t quit. We want you here. We need you. Don’t go doing something you might regret.”

Soon after, on September 3, PK Wrigley ran a full page ad in a Chicago paper backing Durocher. He concluded with the immortal line: “P.S. If only we could find more team players like Ernie Banks.”

Within two years Leo and Ernie were both gone from the Cubs clubhouse.

It is insightful to look at their words in the years after their time together. They both stayed remarkably true to character. Ernie never said a bad word about Leo and Leo, well, they didn’t call him Leo the Lip because of his trumpet-playing ability.Over the next four decades numerous interviewers gave Ernie a chance to trash Leo. Or at least take a few good pokes. He never did. Usually he changed the subject or offered only bland statements. Ernie knew exactly what everyone else said and thought, but he pretended not to. When cornered, he only gave them: “I learned long ago that when you say derogatory things about people it stays with you. Everybody remembers it, especially if it’s written. You can’t retract those things. Of course you have those feelings. . . . but suppose that tomorrow you feel he’s a nice guy again."

In Banks’ 1971 autobiography the chapter dealing with the late ‘60s was titled, “Life With Leo.” While the title of the chapter may have given readers hope of learning his true thoughts, in keeping with the entirely vanilla tone of the book, there were exactly zero negative comments. Ernie credited “Leo’s leadership” with helping the Cubs become a winner. “Leo is unlike any other manager I’ve played for,” he stated. But he offered no specifics. Instead there were generic statements such as “A bark now, a good laugh a little later. He does it to keep us on our toes,” and “Leo can build a players’ morale like no one else.” He credited “Leo’s fine head planning and plotting for the future.” There was absolutely nothing about what “Life with Leo” was really like.

In 1977 Jet magazine offered an article with the leading title, “Banks Finally Tells of Durocher’s Many Insults.” Actually in the article, Banks told very little. The article summed up the many insults and included quotes from others, but Banks himself said nothing of substance.

In his old age, Ernie would add his own altered reality: “It was misinterpreted that Leo disliked me. He made my life better, he made me a better player,”and “Leo wasn’t jealous of me. I think he was just trying to push me. You know, when you’re in the latter stages of a career like I was, sometimes you get lackadaisical. I understood what he was trying to do.”

In 2006, the 71-year-old Banks finally allowed that life with Leo was a bit tough. Even then he quickly added, “As hard as he [Durocher] was on me, I tried to treat him with kindness, always talked to him, on the lane, in the dugout.”

Of course, Leo was much less reserved, and much more nasty. In his book “Nice Guys Finish Last” he devoted an entire chapter to Ernie. It was not a nice chapter. He took care to tarnish both Ernie Banks the player and the myth. He even took swipes at Ernie’s book, writing “All the writers in the country rushed to write what a great book it was, and all of them said in private, ‘If he wanted to write a book, with all the goodwill he has going for him, why didn’t he get himself a writer?' I don’t know why it is, but where Ernie is concerned everybody is always ready to fall over and play dead.”[In Leo’s defense, the criticism of Ernie’s co-writer, Jim Enright, was entirely valid—and it takes only a reading a few pages to agree].

Years later, Leo Durocher had a change of heart, perhaps surgically induced. In 1983 a very contrite 78-year-old Leo, recovering from a recent open heart procedure, perhaps seeing his own mortality at last, spoke at a Cubs reunion and tearfully apologized to the team in general and Ernie Banks specifically for how he had behaved.

Leo passed away in 1991 at the age of 86, Ernie in 2015 at 84. It's nice to think that they are now finally happy together in a better place:

Published on May 20, 2017 07:05

February 20, 2017

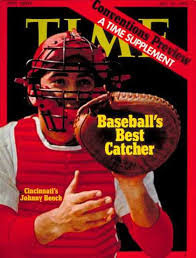

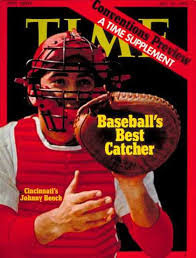

When Johnny Bench's Career Almost Ended at 25

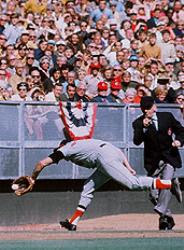

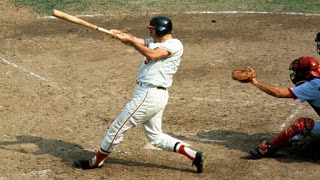

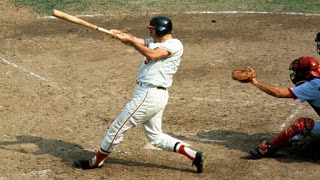

The Cincinnati Reds were only three outs away from being eliminated in the 1972 Playoffs. Trailing the defending World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, 3-2, in the fifth and final game, Johnny Bench led off the bottom of the ninth inning against the Pirates' ace reliever Dave Guisti.

As Bench prepared to leave the on-deck circle, his mother caught his eye. Katy Bench had left her seat and worked her way to the rail near the Reds dugout. Although Katy would later tell a reporter that she yelled, "This is it," in the version Johnny would tell for years he heard her say, “Hit a home run." The exact words are perhaps unimportant, (who can hear clearly when 50,000 fans are screaming?) but his account sounded much better for the myth-makers.

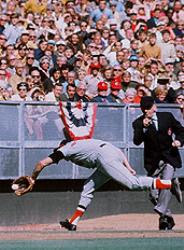

The dutiful son then walked to home plate, swung at an outside two-strike pitch and lined it over the right field wall. Riverfront Stadium exploded. In the broadcasting booth, the voice of 28-year-old Reds announcer Al Michaels reached an octave previously thought unattainable by primates. Although the Reds didn’t officially win the game until a few minutes later when George Foster scored on a wild pitch, there was no doubt that the game was over as soon as Bench’s drive cleared the wall.

It would be remembered as the most dramatic moment in Reds’ history. And the amazing thing about it was that as Bench walked to the plate for that at bat, he was burdened with a secret. None of the fans, no one in the press box, very few in the dugout knew that if he had made an out here, if the Reds failed to advance to the World Series, there was a plausible chance that this would be the last at bat of his major league career.

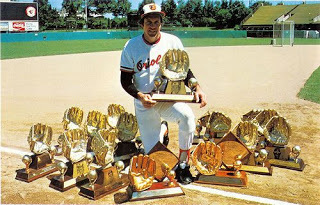

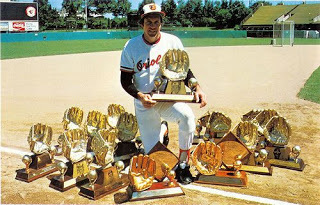

Johnny Bench had proven himself to be a once-in-a-generation transcendent talent. He hit 45 home runs and 148 RBIs in 1970 and followed that with 40 and 129 in 1972, leading the league in both categories both times. On defense, it was immediately apparent that Bench was special from the first day he laced up the shin guards in a late 1967 call-up. No one else would win a National League Gold Glove for catching for the next ten years.

By the end of the 1972 season, Bench had played in five All-Star games and had taken home five Gold Gloves and two MVP awards--and he hadn’t turned 25 yet.

In addition he had reached a level of pop-cultural appeal rarely seen among baseball players. He had toured with Bob Hope, appeared on the popular TV spy show Mission Impossible and belted out songs on Hee Haw. Few major league players would have even tried pulling off the act of snapping his fingers in front of Junior Samples and a hound dog, surrounded by hay bales and fake corn, wearing a pair of lime-green pants borrowed from Kermit the Frog. He was clearly a man of rare talents and accomplishments.

The trouble started when Reds players had their annual routine physical exams in early September. Traditionally this was a casual off-day away from the ballpark, a chance for Pete Rose and Joe Morgan to hold court trading endless put-downs and wise cracks, for Tony Perez to sneak among his teammates, pinching them on the butt and then scurrying away giggling. Few players took the tests seriously. The players, all marvelous athletic specimens in the prime of their lives, passed easily. All except one.

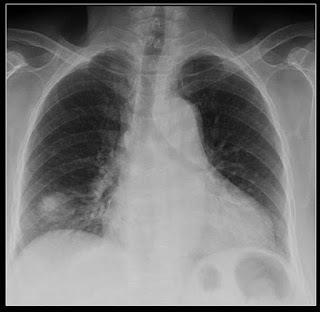

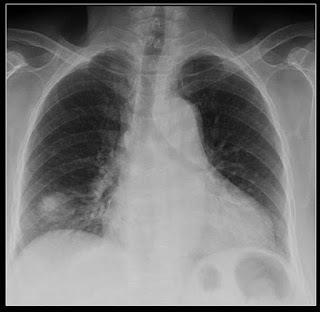

Johnny Bench got a call the next day from someone at the hospital who wanted him to return for another Chest X-Ray; the first one had been a bit blurry, he was told. So Bench went back the next day and the X-Ray was repeated. Before he could leave, they needed another one—just routine, he was told. Then they wanted to do some more tests. Finally he learned the problem: there was a spot on his right lung. A spot that hadn’t been there the previous year.

Doctors couldn’t tell exactly what the spot represented—it could be benign or it could be cancer; they needed more tests to be sure. Blood tests for the usual suspects, tuberculosis and histoplasmosis, were taken and came back negative. Attempts to reach the lesion with a bronchoscope were unsuccessful. Bench was informed that they would need a more invasive test to determine the diagnosis. The only other option was to just watch the lesion awhile and see if it changed. But if they waited and it turned out to be malignant, the waiting would throw away the only chance of cure.

In 1972 lung cancer was almost uniformly fatal. Immediately jumping to mind was the movie Brian’s Song which had debuted the previous year, making more tough he-men run for the kitchen to avoid public tears than anything since Old Yeller. Dying jocks were on the brain.

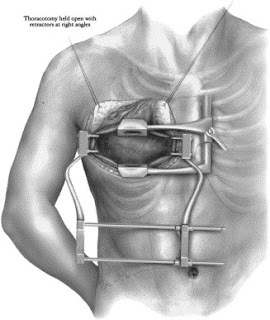

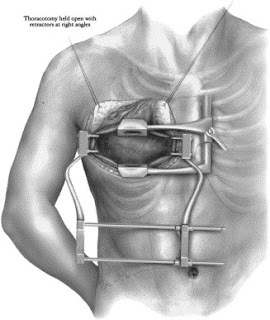

What Bench would need in order to diagnose the spot on his lung was a serious surgical procedure. The medical term thoracotomy was derived from old Greek which, loosely translated, means to have one’s chest filleted open like a mackerel. In 1972 technology the most-commonly used, traditional operation was a posterolateral thoracotomy in which the large muscles of the back, the latissimus dorsi, were completely cut through, often accompanied by the removal of a rib. It was, and remains, one of the most painful surgical incisions known, usually resulting in a slow agonizing recovery process. Cutting through and then sewing the muscles results in scar tissue which can restrict free arm movement. Playing baseball at a high level afterwards is an iffy prospect and could take as long as a year, or longer.

While digesting this information and what it might mean--for his career and his life--Bench silently bore the strain and went about his day job. He not only showed up for work, but performed brilliantly in the closing weeks of the season, hitting 11 home runs and 33 RBIs during the month of September as the Reds drove toward the pennant. Only closest family members and friends were told.

One of those let in on the secret, Bench's attorney and friend Reuven Katz, also happened to represent the surgical department of the University of Cincinnati Medical School. Katz made some discrete inquiries about thoracic surgery and came up with the name of Luis Gonzalez.

Luis Gonzalez, 45 years old in 1972, was a trim, dark-haired man with a warm smiling face and a good sense of humor. A war-time Marine before going to medical school, he had been on staff at the University of Cincinnati for a decade and was known not only as an excellent surgeon, but an innovator. Dr. Gonzalez had been an early proponent of a type of incision for these operations that avoided severing the latissimus dorsi and removing a rib.

Bench met with Dr. Gonzalez and a date was set for the surgery to take place in early December. A brief statement was released to the press informing them of the procedure before Bench entered the hospital, just days after his 25th birthday.

Suddenly Johnny Bench was the most famous hospital patient in the midwest. Cincinnati's two daily newspapers, along with those in nearby Dayton, would keep interested citizens informed of his progress with daily articles, in both the front page and sports page, for the next two weeks.

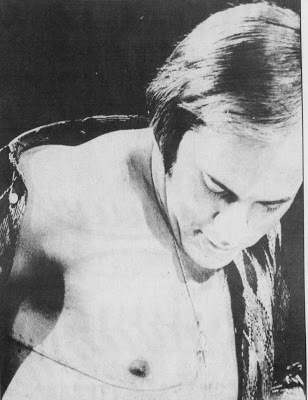

Modern baseball fans, accustomed to players having a myriad of off-season surgical procedures and returning unscathed the next season, should realize that in 1972, the type of operation Bench underwent, although termed a muscle-sparing procedure, was still a harrowing experience. The incision started just below his right nipple and arched under his armpit toward the back. A minor muscle, the serratus anterior, was severed to reach the chest wall.

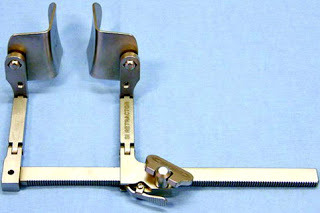

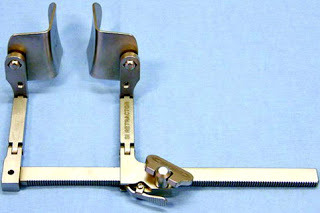

Next, think of the meaty space between the ribs the last time you had a rack at your favorite barbecue joint. This muscle was cut through with a blade. The surgeon then reached for a sinister-looking torture device called a rib-spreader. The scariest aspect of the rib-spreader is that there is no attempt at deception--it does exactly what the name implies: it . . . spreads . . . ribs.

The metal ends are inserted between the ribs and the knob turned, gradually spreading, widening the ribs until adequate visualization of the contents of the chest is achieved. If done too forcefully, this could break ribs or dislocate them from their attachments. Also spreading the ribs stretches the nerve that runs just underneath, resulting in prolonged pain.

Once the biopsy was taken and bleeding controlled, the whole mess was closed with multiple layers of sutures, some in the muscles, some in the tissue beneath the skin and, last, the skin itself. Legend has it that the surgeon, a veteran of more than 15 years in the operating room, remarked that he had never seen a patient with such unusually developed musculature as Bench had in his back.

The operation took two hours and was a success. The lesion, which was slightly larger than a marble, was found in a fissure between the lower and upper lobes of the right lung and was completely removed along with a small amount of actual lung tissue. A frozen section pathology exam was done during the procedure and revealed no sign of cancer.

The official diagnosis, confirmed with further tests in the lab, was coccidiodomycosis, a fungus which is ubiquitous in the southwest. Infection occurs by breathing in an airborne spore which then causes an inflammatory lesion in the lung. It was felt that Bench had probably contracted it in during a golf tournament in the southwest the preceding year.

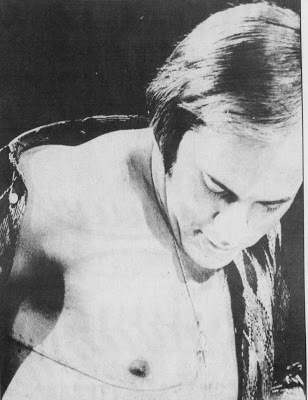

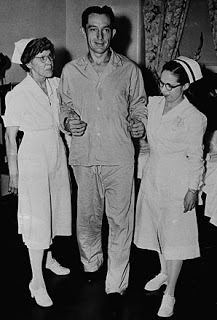

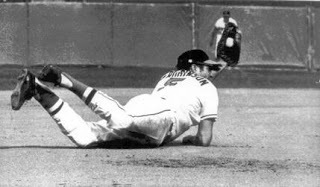

The patient made a quick recovery. Two days after the operation, dressed in red pajamas and a pink robe, Johnny held a press conference in his hospital room. He proudly showed off the gnarly ten-inch scar and joked with reporters that he was taking interviews for pretty young nurses to look after him when he went home. He added that he hoped to be able to use the operation as an excuse in spring training. “If Sparky Anderson gets tough I can just say, ‘Hey, Sparky, I’ve got this lung, you know.’”

Bench spent a restless six weeks recovering. By early February, he was testing his baseball swing and playing golf. By spring training, he was ready. He would catch every game during the exhibition season, a marked increase to his normal spring work load.

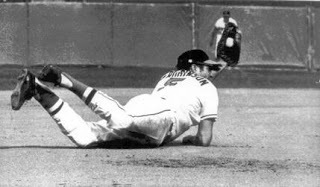

Early, there were rumors that his famed right arm was not yet back to strength. In one of the first spring games, two successive Cardinal base runners tried him out and both would-be thieves were gunned down at second. By the time the season started, the rest of the league had regained their healthy respect for Bench's wing. While the 1973 Reds were stealing 148 bases, only 55 brave souls dared to attempt to take a base without permission against Bench. Half were thrown out.

Bench started slowly at the plate, but in early May he had put together a modest nine-game hitting streak when the Reds traveled to Philadelphia to face the Phillies and their ace Steve Carlton. Bench then treated the Hall of Fame-bound Carlton like a batting practice pitcher, slamming three home runs and seven RBIs in a 9-7 win—he was back. Oddly, it was the second time in three years Bench had victimized Lefty with a three-homer game.

To a casual observer, Bench seemed to bear little negative effect from the drama of the offseason. He would play in 152 games (134 as catcher) in 1973 and finish the season with 104 RBIs. He went on to play ten more years, retiring as the all-time leader in home runs and RBIs for a catcher and had more RBIs than any major league player for the decade of the 1970s.

But the operation did have a cost. While remaining a good RBI man, Bench was not the power-hitter he had been. In the three seasons before the operation, he had averaged 37 home runs a year. His best seasons afterwards were 33 home runs in 1974 and 31 in 1977. He later admitted that he was never quite the same player. “I never felt like I was Johnny Bench after that surgery.”

All things considered, it's remarkable he was able to perform as well as he did. And it's awe-inspiring to wonder what might have been, considering his first five seasons.

As Bench prepared to leave the on-deck circle, his mother caught his eye. Katy Bench had left her seat and worked her way to the rail near the Reds dugout. Although Katy would later tell a reporter that she yelled, "This is it," in the version Johnny would tell for years he heard her say, “Hit a home run." The exact words are perhaps unimportant, (who can hear clearly when 50,000 fans are screaming?) but his account sounded much better for the myth-makers.

The dutiful son then walked to home plate, swung at an outside two-strike pitch and lined it over the right field wall. Riverfront Stadium exploded. In the broadcasting booth, the voice of 28-year-old Reds announcer Al Michaels reached an octave previously thought unattainable by primates. Although the Reds didn’t officially win the game until a few minutes later when George Foster scored on a wild pitch, there was no doubt that the game was over as soon as Bench’s drive cleared the wall.

It would be remembered as the most dramatic moment in Reds’ history. And the amazing thing about it was that as Bench walked to the plate for that at bat, he was burdened with a secret. None of the fans, no one in the press box, very few in the dugout knew that if he had made an out here, if the Reds failed to advance to the World Series, there was a plausible chance that this would be the last at bat of his major league career.

Johnny Bench had proven himself to be a once-in-a-generation transcendent talent. He hit 45 home runs and 148 RBIs in 1970 and followed that with 40 and 129 in 1972, leading the league in both categories both times. On defense, it was immediately apparent that Bench was special from the first day he laced up the shin guards in a late 1967 call-up. No one else would win a National League Gold Glove for catching for the next ten years.

By the end of the 1972 season, Bench had played in five All-Star games and had taken home five Gold Gloves and two MVP awards--and he hadn’t turned 25 yet.

In addition he had reached a level of pop-cultural appeal rarely seen among baseball players. He had toured with Bob Hope, appeared on the popular TV spy show Mission Impossible and belted out songs on Hee Haw. Few major league players would have even tried pulling off the act of snapping his fingers in front of Junior Samples and a hound dog, surrounded by hay bales and fake corn, wearing a pair of lime-green pants borrowed from Kermit the Frog. He was clearly a man of rare talents and accomplishments.

The trouble started when Reds players had their annual routine physical exams in early September. Traditionally this was a casual off-day away from the ballpark, a chance for Pete Rose and Joe Morgan to hold court trading endless put-downs and wise cracks, for Tony Perez to sneak among his teammates, pinching them on the butt and then scurrying away giggling. Few players took the tests seriously. The players, all marvelous athletic specimens in the prime of their lives, passed easily. All except one.

Johnny Bench got a call the next day from someone at the hospital who wanted him to return for another Chest X-Ray; the first one had been a bit blurry, he was told. So Bench went back the next day and the X-Ray was repeated. Before he could leave, they needed another one—just routine, he was told. Then they wanted to do some more tests. Finally he learned the problem: there was a spot on his right lung. A spot that hadn’t been there the previous year.

Doctors couldn’t tell exactly what the spot represented—it could be benign or it could be cancer; they needed more tests to be sure. Blood tests for the usual suspects, tuberculosis and histoplasmosis, were taken and came back negative. Attempts to reach the lesion with a bronchoscope were unsuccessful. Bench was informed that they would need a more invasive test to determine the diagnosis. The only other option was to just watch the lesion awhile and see if it changed. But if they waited and it turned out to be malignant, the waiting would throw away the only chance of cure.

In 1972 lung cancer was almost uniformly fatal. Immediately jumping to mind was the movie Brian’s Song which had debuted the previous year, making more tough he-men run for the kitchen to avoid public tears than anything since Old Yeller. Dying jocks were on the brain.

What Bench would need in order to diagnose the spot on his lung was a serious surgical procedure. The medical term thoracotomy was derived from old Greek which, loosely translated, means to have one’s chest filleted open like a mackerel. In 1972 technology the most-commonly used, traditional operation was a posterolateral thoracotomy in which the large muscles of the back, the latissimus dorsi, were completely cut through, often accompanied by the removal of a rib. It was, and remains, one of the most painful surgical incisions known, usually resulting in a slow agonizing recovery process. Cutting through and then sewing the muscles results in scar tissue which can restrict free arm movement. Playing baseball at a high level afterwards is an iffy prospect and could take as long as a year, or longer.

While digesting this information and what it might mean--for his career and his life--Bench silently bore the strain and went about his day job. He not only showed up for work, but performed brilliantly in the closing weeks of the season, hitting 11 home runs and 33 RBIs during the month of September as the Reds drove toward the pennant. Only closest family members and friends were told.

One of those let in on the secret, Bench's attorney and friend Reuven Katz, also happened to represent the surgical department of the University of Cincinnati Medical School. Katz made some discrete inquiries about thoracic surgery and came up with the name of Luis Gonzalez.

Luis Gonzalez, 45 years old in 1972, was a trim, dark-haired man with a warm smiling face and a good sense of humor. A war-time Marine before going to medical school, he had been on staff at the University of Cincinnati for a decade and was known not only as an excellent surgeon, but an innovator. Dr. Gonzalez had been an early proponent of a type of incision for these operations that avoided severing the latissimus dorsi and removing a rib.

Bench met with Dr. Gonzalez and a date was set for the surgery to take place in early December. A brief statement was released to the press informing them of the procedure before Bench entered the hospital, just days after his 25th birthday.

Suddenly Johnny Bench was the most famous hospital patient in the midwest. Cincinnati's two daily newspapers, along with those in nearby Dayton, would keep interested citizens informed of his progress with daily articles, in both the front page and sports page, for the next two weeks.

Modern baseball fans, accustomed to players having a myriad of off-season surgical procedures and returning unscathed the next season, should realize that in 1972, the type of operation Bench underwent, although termed a muscle-sparing procedure, was still a harrowing experience. The incision started just below his right nipple and arched under his armpit toward the back. A minor muscle, the serratus anterior, was severed to reach the chest wall.

Next, think of the meaty space between the ribs the last time you had a rack at your favorite barbecue joint. This muscle was cut through with a blade. The surgeon then reached for a sinister-looking torture device called a rib-spreader. The scariest aspect of the rib-spreader is that there is no attempt at deception--it does exactly what the name implies: it . . . spreads . . . ribs.

The metal ends are inserted between the ribs and the knob turned, gradually spreading, widening the ribs until adequate visualization of the contents of the chest is achieved. If done too forcefully, this could break ribs or dislocate them from their attachments. Also spreading the ribs stretches the nerve that runs just underneath, resulting in prolonged pain.

Once the biopsy was taken and bleeding controlled, the whole mess was closed with multiple layers of sutures, some in the muscles, some in the tissue beneath the skin and, last, the skin itself. Legend has it that the surgeon, a veteran of more than 15 years in the operating room, remarked that he had never seen a patient with such unusually developed musculature as Bench had in his back.

The operation took two hours and was a success. The lesion, which was slightly larger than a marble, was found in a fissure between the lower and upper lobes of the right lung and was completely removed along with a small amount of actual lung tissue. A frozen section pathology exam was done during the procedure and revealed no sign of cancer.

The official diagnosis, confirmed with further tests in the lab, was coccidiodomycosis, a fungus which is ubiquitous in the southwest. Infection occurs by breathing in an airborne spore which then causes an inflammatory lesion in the lung. It was felt that Bench had probably contracted it in during a golf tournament in the southwest the preceding year.

The patient made a quick recovery. Two days after the operation, dressed in red pajamas and a pink robe, Johnny held a press conference in his hospital room. He proudly showed off the gnarly ten-inch scar and joked with reporters that he was taking interviews for pretty young nurses to look after him when he went home. He added that he hoped to be able to use the operation as an excuse in spring training. “If Sparky Anderson gets tough I can just say, ‘Hey, Sparky, I’ve got this lung, you know.’”

Bench spent a restless six weeks recovering. By early February, he was testing his baseball swing and playing golf. By spring training, he was ready. He would catch every game during the exhibition season, a marked increase to his normal spring work load.

Early, there were rumors that his famed right arm was not yet back to strength. In one of the first spring games, two successive Cardinal base runners tried him out and both would-be thieves were gunned down at second. By the time the season started, the rest of the league had regained their healthy respect for Bench's wing. While the 1973 Reds were stealing 148 bases, only 55 brave souls dared to attempt to take a base without permission against Bench. Half were thrown out.

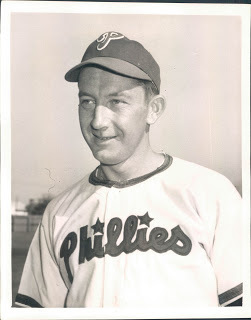

Bench started slowly at the plate, but in early May he had put together a modest nine-game hitting streak when the Reds traveled to Philadelphia to face the Phillies and their ace Steve Carlton. Bench then treated the Hall of Fame-bound Carlton like a batting practice pitcher, slamming three home runs and seven RBIs in a 9-7 win—he was back. Oddly, it was the second time in three years Bench had victimized Lefty with a three-homer game.

To a casual observer, Bench seemed to bear little negative effect from the drama of the offseason. He would play in 152 games (134 as catcher) in 1973 and finish the season with 104 RBIs. He went on to play ten more years, retiring as the all-time leader in home runs and RBIs for a catcher and had more RBIs than any major league player for the decade of the 1970s.

But the operation did have a cost. While remaining a good RBI man, Bench was not the power-hitter he had been. In the three seasons before the operation, he had averaged 37 home runs a year. His best seasons afterwards were 33 home runs in 1974 and 31 in 1977. He later admitted that he was never quite the same player. “I never felt like I was Johnny Bench after that surgery.”

All things considered, it's remarkable he was able to perform as well as he did. And it's awe-inspiring to wonder what might have been, considering his first five seasons.

Published on February 20, 2017 11:10

February 9, 2017

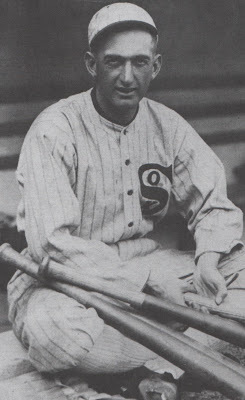

Say it Wasn't So: Joe Jackson, World War I's Most Famous Baseball Slacker

Here's one you may not have heard: how Shoeless Joe Jackson was almost turned into America's most-hated draft-dodger in World War 1. It's true, but as with all Shoeless Joe stories, some work is required to separate fact from myth. It also helps to read published reports from his contemporaries and to view everything in the context of the times and to be aware of other forces which were at work.

The War began in Europe in July, 1914 but had little effect on baseball in America the first few years. The 1916 season had been both successful on the field and profitable for the owners. Business was good. But things would soon be changing. The United States declared war on Germany just days before the start of the 1917 season.

Initially there was talk of shutting down baseball--a thought that mortified owners, who understandably did not want to lose their businesses. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey was especially unhappy at the prospect. He had invested heavily to build his championship-caliber team (he spent his money on obtaining players, not necessarily on paying them). His star hitter, Joe Jackson, had been acquired from Cleveland in 1915 in a deal described as worth $74,000--$31,000 in cash and 3 players who had cost Comiskey $44,000--one of the most expensive deals of the time.

Outwardly eager to help the national cause, baseball owners made a great show of their patriotism. They donated cash and rounded up baseball equipment for soldiers to use in their spare time. Exhibition baseball games were played for the benefit of the Red Cross. Special enlistment booths were set up at American League parks. Players went through military marching drills in pre-game ceremonies. There was even a prize for the best drilling major league team.

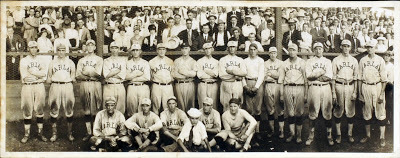

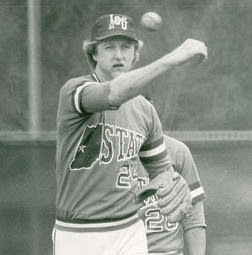

The Chicago White Sox go through pregame military drills (Jackson is third from the right)

As the war turned into a second year, the owners agreed to abbreviate the 1918 schedule to 140 games. It soon became obvious that benefits and drills and shortened seasons were not going to be enough to keep baseball players out of the war, however. When the U.S. military leaders got their first real good look at the teeth of the German military machine, they murmured around their cigarettes, "We're gonna need a bigger army."

And thus in May, 1918 Provost Marshall General Enoch Crowder issued the famous "Work or Fight" order, stating that every healthy male between the ages of 21 and 30 must find "essential work" by July 1 or face military conscription.

The wording of the order was particularly chilling for baseball owners. It included a list of employment which was regarded as nonessential to the war effort: "games, sports and amusements, excepting actual performers in legitimate concerts, operas or theatrical performances." Baseball owners were suddenly aware that they needed to round up some guys who could not only hit .300 and play the field, but do so while wearing a Viking helmet and belting out a rousing falsetto. But since such men were in short supply at the time (they always seem to be), other arrangements needed to be made.

Initially owners tried to get special consideration for their able-bodied players. While the government in Washington indicated that they hoped the game would go on, if it could be accomplished "in harmony with the great purpose of putting winning the war first above everything," and Crowder released another statement within a week suggesting that ballplayers would be considered by draft boards on an individual basis, it became clear that a great many ballplayers would be leaving their teams. Overall, an average of 15 players would be lost per team in the 1918 season.

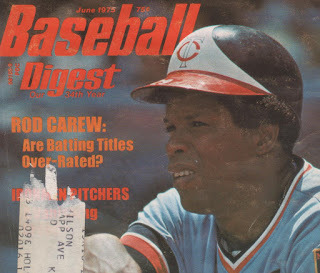

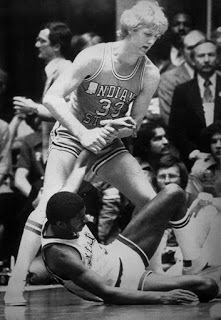

Which brings us to Joe Jackson. In 1918 Joe was 30 years old and had completed seven major league seasons with a sparkling .352 lifetime batting average. He was considered to be the second best hitter in the land (some thought the best at purely swinging the stick as Ty Cobb usually bunted enough to get more than the five or so hits per 500 at bats that gave him the roughly ten point lead in average, whereas Joe bunted about as often as he read from The Complete Works of William Shakespeare).

In 1917 Joe had hit .301, the worst average of his career, but he had helped to lead the White Sox to the World Series title (he hit .304 in the Series, not bad, but not as good as the .375 he would hit in the more famous Series two years later).

As a great hitter and key member of the World Champs, Jackson was one of the game's most famous personalities. But he was also one of the most difficult for fans and writers to figure out. His very existence seemed to be an amalgam of assorted tall-tales, half-truths and outright lies. Joe himself did little to clear up the confusion when interviewed or spotted on the street.

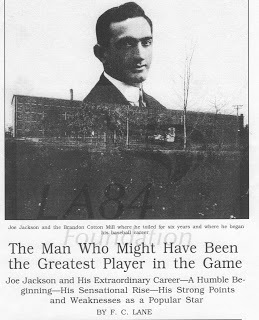

In a 1916 profile for Baseball Magazine, one of the pre-eminent early baseball writers, F. C. Lane, reported that "The oddest character in baseball today is that brilliant but eccentric genius, Joe Jackson. . . To sum up his talents is merely to describe those qualities which should round out and complete the ideal player. In Jackson, nature combined the greatest gifts any one ball player has ever possessed but she denied him the heritage of early advantages and that well balanced judgement so essential to the full development of his extraordinary powers." And that lack of early advantages and well-balanced judgement would prove to be very important to Joe in the years to come.

In a 1916 profile for Baseball Magazine, one of the pre-eminent early baseball writers, F. C. Lane, reported that "The oddest character in baseball today is that brilliant but eccentric genius, Joe Jackson. . . To sum up his talents is merely to describe those qualities which should round out and complete the ideal player. In Jackson, nature combined the greatest gifts any one ball player has ever possessed but she denied him the heritage of early advantages and that well balanced judgement so essential to the full development of his extraordinary powers." And that lack of early advantages and well-balanced judgement would prove to be very important to Joe in the years to come.By the spring of 1918 three of Joe Jackson's brothers had already volunteered for military service. Joe was the sole supporter of his wife, Katie, his mother, a younger brother and a sister. Because of this, the Greenville, South Carolina draft board had placed him in Class 4, making him safe from the draft.

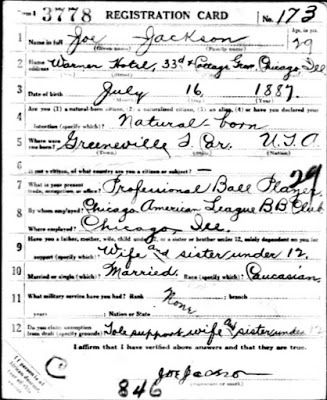

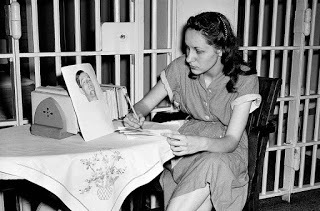

Joe Jackson's draft card (those under the impression that Jackson was unable to write should note the fairly legible signature at the bottom)

After 17 games of the 1918 season, Joe was hitting .354. The White Sox were in Philadelphia for a series against the A's when Joe received a dispatch informing him that the Greenville draft board had reclassified him 1-A. He reported as ordered to the Philadelphia examining board, passed with a perfect mark and was told to expect orders to leave for an army training camp within the next two weeks.

When the White Sox departed for Cleveland the next day, Joe Jackson was nowhere to be found. He soon turned up and announced that he had found a position of employment with the Harlan and Hollingsworth Shipbuilding Company, a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel, in Wilmington, Delaware. Work in the shipbuilding industry was considered essential and thus exempted Joe from military service.

The news did not play well in the national press. While many other players were avoiding combat by playing on ball teams in industry and the military, Joe Jackson, the most prominent of the early names, was singled out.

That week's Sporting News carried several editorials about the "Jackson Case," as it was roundly being called. Readers were informed that "at a time of every man doing his patriotic duty," Joe Jackson was "cleverly seeking exemption when by all rights . . . he should be in an Army or Navy training camp." Jackson "owed it to the great game he represents, to join the military and set an example to myriads of youngsters coming of age who hold him as an example."

In the same issue, American League President Ban Johnson "leveled a solar plexus wallop at the baseball slacker." Johnson, who hated Charles Comiskey's ample guts and loved nothing more than a chance to knife his enemy when he was vulnerable, to publicly humiliate him, derail his business and maybe cost him a player or two, announced a warning to players seeking to avoid conscription. He told the writer he would like to yank back by the collar those who entered employment with the ship construction business particularly. Johnson left little doubt this was specifically in response to Joe Jackson's status. Johnson would soon announce that hereafter athletes would have to stick with their clubs until the final Government call, and then go straight to war-service.

That was only the beginning. A scathing editorial soon followed in the Chicago Tribune entitled "The Case of Joe Jackson." Joe, a man of "unusual physical development," who "presumably would make an excellent fighting man," was excoriated and branded a coward and shirker.

Another article entitled "Retreats to Shipyard" stated "The fighting blood of the Jacksons is not as red as it used to be in the days of old Stonewall and Old Hickory for General Joe of the White Sox has fled to the refuge of a shipyard."

Charles Comiskey, according to some sources, had initially encouraged his players to try to find exemptions to remain playing for the White Sox as long as possible. Always careful of the winds of public opinion, however, he now pompously joined in piling on his employee. Comiskey was shocked (shocked!) that one of his beloved employees would even think of trying to avoid military service in this time of national need. "There is no room on my club for players who wish to evade the army draft by entering the employ of shipbuilders," he told reporters from atop his soapbox. The great man was so disappointed, he threatened to not take the "jumpers" back after the war. Skeptics to Comiskey's pure intentions would later point out that while this posture kept him on the side of patriotism and duty, it also prepared him for future player negotiations, well aware that a man who thinks he is not welcomed back (and has no other employment options due to the reserve clause) is much more pliable at the contract table.

It soon became apparent that the thing that truly rankled Comiskey was not that Joe Jackson was shirking his duty to his country by not carrying a rifle, but that he was doing so while playing baseball for someone else; and doing so while Comiskey's team was certain to fall in the standings.

According to Baseball Magazine, "One disagreeable feature made itself manifest during May--what looked almost like a second Federal League, fostered and developed under the wing of the Government . . . a new league of steel, shipbuilding, and munition plants, with the players mostly well-known stars of the present or the past. There was a gasp of surprise when the list of players gathered by the steel plants was given out. . . It was frankly asserted [by major league owners] that agents of the steel plants were gathering big league stars, promising them fat salaries, nominal positions in the plants, with nothing to do but play ball, and at the same time pointing out that munition workers wouldn't have to go to the trenches. . . . The pot boiled over, though, when Joe Jackson, the great star of the White Sox, after being called by the draft, announced that he would enter a shipbuilding or steel-plant and the steel-folks began to bill him as a star of their ball club. . . . making money on the side."

In the same vein, the Sporting News asserted that "Jackson was not a volunteer in the ship building concern, but was sought out and went because he was importuned to do so."

Owners were outraged that fans (people who should be paying money to them!) were going to see baseball stars (who used to belong to them!) play for someone else.

Through it all, Joe uttered not a word of public comment or protest against the accusations. A solitary writer in the Sporting News offered some defense for Joe, stating that there was something unfair in the Greenville draft board decision. "I can't understand why Jackson was placed in Class One-A. There are many stars of the big leagues who are married and have many times the amount of wealth Joe possesses who are in Class Four." It appeared the Greenville decision was made to give a great show of not showing favoritism to a famous athlete or perhaps as the result of a personal grudge.

Despite the public outcry, work by the ballplayers at the shipyards continued throughout the war. How much work was done and how much baseball did the guys actually play? It's anyone's guess. For the record, they did play a lot of baseball. But a foreman at the ship yard told a reporter, "The boys in the yard all knew they [the ball players] were married men and hence not attempting to duck the draft and they warmed up with them right away when they observed that they meant business. . . and they weren't handed any soft jobs like watchmen . . . they do a good day's work." He added that they only went to the ball field at the close of the work day.

And much good came out of the ballplaying. They played a series of exhibitions for the Red Cross. One at the Polo Grounds, with Joe as the headliner, raised $6,000. Joe's wife would keep in her scrapbook a letter from a Reading, Pennsylvania organization thanking him for drawing 10,000 fans to a benefit.

The tumult over Joe soon faded from the public's attention as much more pressing matters arose and attention turned to the actual fighting in Europe. As for 1918, it turned out pretty well, Joe Jackson was the star of the Steel League, hitting a robust .393. Harlan won the championship--Joe hit two home runs in the title game--and, oh yeah, we won the war, which is always nice.

So everyone was in good spirits and ready to get back to baseball business as usual for 1919. There was only the small matter of rounding up the players. When the 1918 season had ended early on September 1, the owners had released all players, saving around $200,000 they would have otherwise spent on those pesky salaries. Amazingly, the next spring every single player--technically all free agents--signed back with their original team for 1919 (66 years later this practice would be labeled collusion and would cost the owners millions in a court settlement, but at the time a players union was as inconceivable as another, larger World War ever occurring).

As an example of just how much the owners had baseball writers in their pockets, the said writers soiled themselves attempting to educate fans on all that the owners had done for their country and baseball in general. "[The baseball] fan, when it's all over and the game comes back to its former basis, should remember how the . . . magnates acted in the hour of need." W. A. Phelon, wrote in Baseball Magazine. Not satisfied with mere praise, Phelon even suggested the public should give them a "Magnates' Day and a lot of floral tokens just to show that these gentlemen, after many years won the public heart at last?"

Early in 1919, Comiskey, that gentleman magnate, let it be known that Joe Jackson had been reinstated to his team. What with the war being won and all, opinions had changed and the big ol' lovable Roman was willing to let bygones be bygones--especially for guys who could hit .350 in their sleep and were willing to do so for a pittance. He signed Joe back for the same $6,000 a year he had been making since 1914.

Joe Jackson and his White Sox teammates quickly proved to be the best in baseball in 1919 as they stormed toward the pennant, and a date with infamy.

So all the ingredients were there: the avarice of owners, the unrelenting drive of organized baseball and writers, working side-by-side, to maintain the proper image at all costs, sacrificing a few players if necessary, the cut-throat rivalry between Ban Johnson and Charles Comiskey, and the players, plugging along on the field, accepting the results of it all.

Shoeless Joe Jackson, the great misunderstood slugger from Greenville, South Carolina, whose legacy would be still provoking emotional debates a full century later, was, as so eloquently put by Mongo in Blazing Saddles, only a pawn in the game of life. Unfortunately for Joe, it wouldn't be the last time.

Published on February 09, 2017 16:08

November 21, 2016

It Happens Every Spring: Baseball's Infamous Relationships

Baseball fans were shocked by last week's tweet from Kate Upton about Justin Verlander losing the Cy Young Award vote. It wasn't the fact that a supermodel would express displeasure with voters for a baseball award or even her choice of verbiage that surprised them, however, it was the simple realization that here was news of a baseball player and his significant other that, for once, did not spell doom for the ballplayer. She was merely supporting her guy; which is always nice.

Fans have unfortunately grown accustomed over the years that when something involving a baseball player and his spouse or girlfriend hits the news it is invariably of such depravity and disgrace that fans must force themselves to watch and read about it over and over (and over and over).

I thought this might be a good time to review some of these unfortunate events if for no other reason than the season is over and there are no more games to talk about.

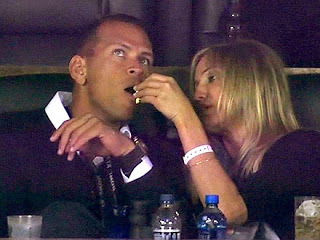

Alex Rodriguez eats popcorn:

Forget about the sulking postseason slumps, the steroid allegations and everything else. The single reason most baseball fans hated A-Rod was the unwanted spectacle of the camera catching his then-best girl Cameron Diaz feeding him popcorn during Super Bowl XLV in 2011. The sight of baseball's highest paid player smugly enjoying such contrived, domestic pseudo-bliss with a gorgeous actress was too much for anyone to bear without yakking in their nachos.

But in A-Rod's defense, what would you do? Some guys just likes popcorn.

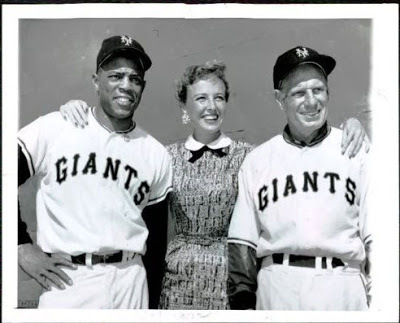

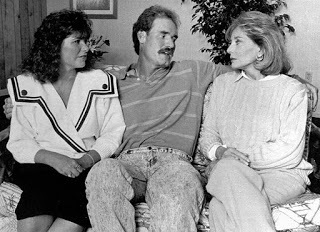

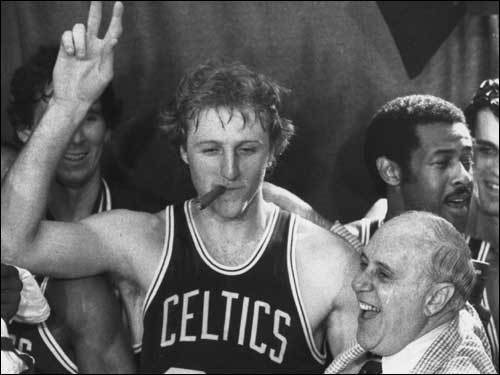

Leo Durocher-Laraine Day

At the time Leo was the headline-grabbing, much-reviled manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Prematurely bald, loud, rude and selfish, he was also a snazzy dresser and reeked of confidence and masculinity. Since he was known to never lack for female companionship, apparently these latter qualities were considered somewhat desirable to the opposite sex when weighed against the former.

Laraine Day was a pretty young actress who starred in a number of B-level mediocre films, most notably seven Doctor Kildaire flicks as the main character's fiance. She and Leo met, and, in the manner of all classic stories, fell in love.

One slight technicality: Day was married with three adopted children at the time.

Nevertheless, in late 1946 the 26-year-old Day abruptly filed for divorce in California and took up with 41-year-old Leo the Lip. Divorce was not something to be entered into and obtained easily in those days. When she learned that state law required a one-year cooling-off period of separation, Day scurried to Mexico for a quickee divorce in December and married Leo there. There were complications as it would be a year before her divorce and new marriage would be recognized in the states.

Day's ex-husband, as might be expected from the jilted husband of a girl who looks that good in a nursing cap, was not pleased by the whole monkey business. He complained to reporters that Leo was not a fit or proper person to associate with and accused Leo of "dishonorable and ungentlemanly conduct" with his wife (anyone who had ever played baseball for or against Durocher would have wholeheartedly agreed with him on both accounts). Leo, who steadfastly believed that all was fair in love and war and baseball, neither denied nor apologized for anything.

The scandal mushroomed in newspaper print. In February, 1947, the Catholic Youth Organization publicly denounced Leo's behavior as a poor example for youngsters and withdrew its support for the Dodger's Knothole Gang. Meanwhile, Durocher had already been suspected by the baseball commissioner's office of hanging out with undesirable gambling figures and he also became caught up in some skulduggery between the Yankee's Larry MacPhail and Branch Rickey. The end result (anyone can draw a conclusion as to which of the problems was the main cause) was that Leo was suspended by Commissioner Chandler for the year.

For her part, Laraine quickly charmed sportswriters and her new husband's players. Although there were later reports of some hard feelings due to disparaging remarks about players and umpires on her radio show, she became known as the "First lady of baseball."

The marriage, much to the amazement of anyone who knew Leo from the baseball field, lasted until 1960.

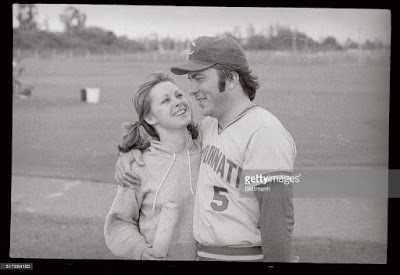

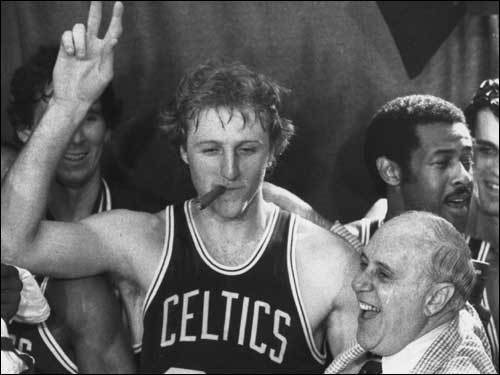

Johnny Bench's first marriage

In the early 1970s Johnny Bench was generally acknowledged as the most eligible bachelor in sports not named Joe Namath. He was perpetually seen with blond models on his arm and, in a nod to his hometown of Binger, Oklahoma, was referred to as the Swinger from Binger; and the name had nothing to do with his ability with a bat.

By the winter of 1974, the 27-year-old Bench had already appeared in seven All-Star games, won seven Gold Gloves, two Most Valuable Player Awards, two home run titles and three RBI titles. He owned the burg of Cincinnati.

In January, 1975 Bench made the grand announcement that he had become engaged and would be married in a few weeks. The mournful wail of gnashing of teeth loudly echoed throughout the Ohio Valley as female baseball fans learned the news. Several even called the Reds' office and demanded a refund for their season tickets.

The anguish of disappointed ladies-in-waiting notwithstanding, the news was otherwise greatly celebrated in the Queen City. It was as if a royal prince had ventured forth and returned to the realm bearing a princess.

Peasants of the Kingdom were informed that the lucky bride-to-be was Vickie Chesser, a former Miss South Carolina, 1970 Miss USA Runner-up and Ultrabrite toothpaste model.

The last title was not insignificant in the mid-70s, Ultrabrite toothpaste commercials, proclaiming to add sex appeal, had been the launching board for such luminaries as future Charilie's Angels Farrah Fawcett and Cheryl Ladd.

The whole affair dominated Cincinnati society columns, and the thoughts of the good citizens, for weeks. Vickie was feted at a never-ending parade of cocktails and dinners.

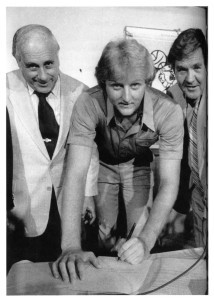

Details of the whirlwind courtship emerged in the newspaper and were fawned over by all. The uber-confident Bench had seen Vickie on TV, got her phone number from a friend and cold-called her apartment in New York City (not a baseball fan, she'd never heard of him) and convinced her to fly to Cincinnati to meet him for a date. The couple soon flew to Las Vegas to become better acquainted over the New Years weekend. By January 21 they were engaged. Vickie proclaimed to reporters that it was a "fairy tale love story."

The marriage was billed as the social event of the decade--perhaps the century--in Cincinnati and indeed it was. Some were disappointed to find out local TV was not carrying the event live. The much-talked-about guest list, which one Cincinnati Society column writer joked included "only the immediate city," actually included President Gerald Ford, Bob Hope, Dinah Shore, Joe DiMaggio and Jonathan Winters (they all sent their regrets).

The marriage took place February 21, 1975. More than 800 attended the ceremony, while a crowd estimated at 400 stood outside the church hoping to catch a glimpse of royalty and soak up some of the aura. The Cincinnati Enquirer ran a four-column, half-page photo of the happy couple smooching on the next day's front page, above the fold.

They honeymooned in Tampa, while Johnny went to work in spring training. While there, Vickie thoroughly charmed all sportswriters. She cooed and giggled and remarked how cute and adorable Johnny was with his little hat turned backwards when he caught and how serious he and his little friends seemed to be as they chased the ball around the field. The middle-aged wags ate it up.

.

Unfortunately, the happiness was very shortlived. Apparently Vickie soon learned that the life of a baseball wife was not for her. By that fall observers noticed the couple was rarely seen together. By March, 1976, they announced they were divorcing.

Bench tried to take the high road and said publicly that it was a private matter, that they had agreed to disagree and refused to divulge any details or lay blame. Vickie, however, took a different approach.