Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 7

December 5, 2013

Facebookers Like The Idea Of A 'Sympathize' Button (Keep Waiting For 'Dislike')

The long-coveted "dislike" button may never make its way Facebook. But a Facebook engineer said Thursday that the social network has informally experimented with an alternative to "like": specifically, the "sympathize" button.

Facebook's members have for years demanded a less cheery way to quickly respond to friends' posts, pointing out that "liking" becomes awkward and inappropriate when someone posts about a breakup, a death or even just a bad day.

The social network evidently hears their complaints: During a Facebook hackathon held "a little while back," an engineer devised a "sympathize" button that would accompany gloomier status updates, according to Dan Muriello, a different Facebook engineer who described the hackathon experiment at a company event Thursday. If someone selected a negative emotion like "sad" or "depressed" from Facebook's fixed list of feelings, the "like" button would be relabeled "sympathize."

Playing around with a "sympathize" button at a hackathon -- a chance for staffers to brainstorm new ideas for site features -- hardly guarantees it'll pop up in feeds soon. The social network relies on its hackathons to explore out-of-the-box ideas, many of which never materialize.

Muriello said his colleague's creation was well-received by fellow Facebookers, but isn't making its way to the site. For now.

"It would be, 'five people sympathize with this,' instead of 'five people ‘like’ this,'" said Muriello. "Which of course a lot of people were -- and still are -- very excited about. But we made a decision that it was not exactly the right time to launch that product. Yet."

Muriello spoke during a presentation at Facebook's Compassion Research Day, a day-long public event at which researchers from Facebook, Yale University and the University of California, Berkeley shared findings from studies on human behavior on Facebook.

A Facebook spokesman called the hackathons "the foundation for great innovation and thinking about how we can better serve people around the world."

"Some of our best ideas come from hackathons, and the many ideas that don’t get pursued often help us think differently about how we can improve our service,” the spokesman wrote in a email to The Huffington Post.

Yet many of the site's signature features, like Facebook Chat, the friend suggester and the Timeline profile pages, have indeed emerged from hackathons.

If you're someone who loves the idea of "sympathizing" your way through the News Feed, here's one reason to be hopeful: The "like" button itself was a hackathon invention.

Facebook's members have for years demanded a less cheery way to quickly respond to friends' posts, pointing out that "liking" becomes awkward and inappropriate when someone posts about a breakup, a death or even just a bad day.

The social network evidently hears their complaints: During a Facebook hackathon held "a little while back," an engineer devised a "sympathize" button that would accompany gloomier status updates, according to Dan Muriello, a different Facebook engineer who described the hackathon experiment at a company event Thursday. If someone selected a negative emotion like "sad" or "depressed" from Facebook's fixed list of feelings, the "like" button would be relabeled "sympathize."

Playing around with a "sympathize" button at a hackathon -- a chance for staffers to brainstorm new ideas for site features -- hardly guarantees it'll pop up in feeds soon. The social network relies on its hackathons to explore out-of-the-box ideas, many of which never materialize.

Muriello said his colleague's creation was well-received by fellow Facebookers, but isn't making its way to the site. For now.

"It would be, 'five people sympathize with this,' instead of 'five people ‘like’ this,'" said Muriello. "Which of course a lot of people were -- and still are -- very excited about. But we made a decision that it was not exactly the right time to launch that product. Yet."

Muriello spoke during a presentation at Facebook's Compassion Research Day, a day-long public event at which researchers from Facebook, Yale University and the University of California, Berkeley shared findings from studies on human behavior on Facebook.

A Facebook spokesman called the hackathons "the foundation for great innovation and thinking about how we can better serve people around the world."

"Some of our best ideas come from hackathons, and the many ideas that don’t get pursued often help us think differently about how we can improve our service,” the spokesman wrote in a email to The Huffington Post.

Yet many of the site's signature features, like Facebook Chat, the friend suggester and the Timeline profile pages, have indeed emerged from hackathons.

If you're someone who loves the idea of "sympathizing" your way through the News Feed, here's one reason to be hopeful: The "like" button itself was a hackathon invention.

Published on December 05, 2013 16:25

New Selfie-Help Apps Are Airbrushing Us All Into Fake Instagram Perfection

A few weeks ago, a friend posted a “#carselfie” to Instagram. It was a beautiful photo -- she peered up at the camera from under a beanie and looked positively radiant in the passenger seat of her car -- and I duly “liked” it. “#Toogorgeous,” another friend wrote in a comment under the photo.

She’s a stunning lady. But the photo, I learned later, was in fact “#toogorgeous” to be true: She’d had some digital work done.

My friend, like millions of others online, had spruced up her selfie with Perfect365, a free app that lets people instantly smooth skin, excise zits, highlight eyes and even resize noses before sending their image out on the Internet.

Perfect365 belongs to a growing breed of selfie-help apps, like FaceTune, ModiFace, Pixtr and Visage Lab, that let anyone with fingers and a smartphone transform basic snapshots into flawless Annie Leibovitz portraits (Buzzfeed’s John Herrman dubs this “selfie surgery.”) Eyelashes can be added, teeth whitened, smiles stretched, pounds shed, clocks reversed, genes fought. And artfully, too: unlike the previous generation of portrait-editing apps, which left figures with the two-dimensional masks of anime characters, these apps, like the best plastic surgeon, leave few obvious marks. I, for one, would never have guessed the #carselfie had a little help.

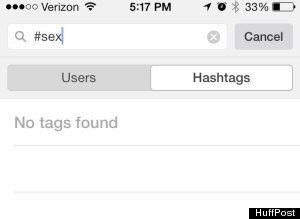

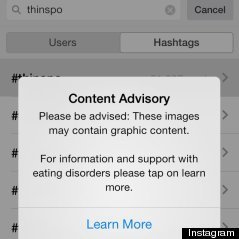

Perfect365 in action. Users must first align their face with "KeyPoints," then can choose a range of effects, from adding false eyelashes and sweeping on blush to evening out skintones and whitening teeth.

While many claim social media has provided a more authentic and unvarnished view into people’s lives, the popularity of these selfie-help apps suggests precisely the opposite. We’ve always cherry-picked what we share online, but more than ever, what you see isn’t what you get. Even as people use Snapchat to share silly photos that, crucially, disappear after a few seconds, those same social media users are delighting in new ways to edit their lives and present an ever-more perfected, artificial image of their world. We’re hungry for ways to exert more control over our images, not less. And who’s to blame us? The rise of selfie-help represents a new way for people to cope with the relentless judgment of the web and the pressure to disclose more online. It also hints at the start of an airbrushing arms race that could make impossibly attractive photos the norm.

“There’s definitely more pressure to have a better version of yourself or put your best foot forward,” said Caroline Tien-Spalding, director of consumer marketing at ArcSoft, Perfect365’s parent company. “You don’t know how long that photo is going to live or how long the impression that you’re putting out there will last.”

While selfies have lost their stigma, these selfie-help apps are still taboo. Just 50,000 Instagram photos have been tagged #Perfect365 -- mostly people playing with the app's makeup filters for dramatic effect -- but the app has been downloaded 17 million times since its launch two years ago. People’s reluctance to acknowledge the handiwork of their digital dermatologists hasn’t much hampered the success of this type of app: ModiFace’s suite of about 20 editing apps have been installed nearly 27 million times, and FaceTune, since its debut this past March, has topped Apple’s rankings as the most popular paid app in 69 countries, including the U.S.

These selfie-enhancers skew toward teens and 20-somethings, who are highly active on social media, and are also overwhelmingly female. Seventy percent of the users of FaceTune, which its creators, perhaps naively, thought was “gender neutral,” are female. And two-thirds of Perfect365’s users are under 24 years old.

The pictures end up on dating profiles, Instagram, Facebook or even Christmas cards. (The chief executive of ModiFace said there’s always a bump in downloads around the holidays.) An 18-year-old high-school student in New York, who declined to be named to protect her privacy and her friends’, said that nine out of ten female friends quietly edit their Facebook profile photos before they’re uploaded, sometimes making an arm look skinnier or blurring a double chin, other times just tweaking the lighting to make it more flattering.

“I’ve had phone calls where girls will ask me to go on iChat and send me four different versions of the same picture -- with different lighting, with different skin," she said. Among her peers, iPhoto’s suite of tools is still the most popular, she said.

Much as in real life, the only thing worse than looking zitty, wrinkled and tired is looking like you’ve sought help. If you get caught editing a photo, “it’s very embarrassing,” the 18-year-old said. “People are hyperaware of not wanting to seem fake in their pictures. As much as they edit them, it has to come off as natural.”

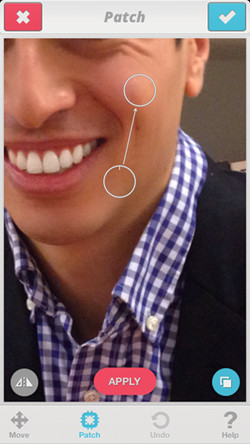

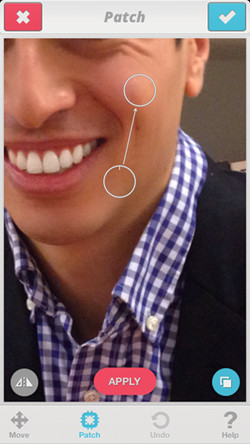

FaceTune's "Patch" tool in action.

Though Perfect365 offers a range of dramatic makeup styles, with names like “Enchant,” or “Ocean,” the app’s most natural-looking filter, which gently evens skin tones, is the most popular. (According to ArcSoft, 80 percent of people either use the "Natural" filter or custom settings.) The co-creator of FaceTune, Nir Pochter, agreed that most of their users opt for only minor improvements, like whiter teeth or fewer pimples, that don’t reveal any futzing with the photo.

“My impression from our users is that they want to look in all their photos how they know they can look, because they saw it in their best photos,” he said.

Jacqui Adkins, a 29-year-old FaceTune fan from South Amherst, Ohio, recently used the app to spruce up a shot of herself and her 7-year-old son. She touched up her skin, covered up a scratch on her son’s chin and then made the picture her Facebook profile photo. The appeal, she said, was that she could subtly fix temporary flaws caused by a breakout or poor lighting.

Another FaceTune aficionado, Jennifer Brewer, 32, said she sees the apps as a necessary response to flawless Photoshopped fashion spreads. She doesn’t have great skin, she conceded, and the app lets her “even the playing field.”

“We live in a world where everything you see on TV or in a magazine is edited to make a person look great,” Brewer wrote in an email. “I want to look good too.”

So may everyone else. Even with a small fraction of Facebook and Instagram’s users currently morphing their photos, it’s clear these apps have the potential to make touching up de rigueur, so that every casual snapshot has the polish of a Vogue photo shoot. Sebastian Thrun, the co-founder of Google X, told me in an interview last year that he imagined technology like Google Glass, with its ever-present camera, could push us to share photos that are “uglier” and “more personal.” Instead, a contradictory trend is in motion: our pictures are getting prettier.

These apps are attractive for the simple reason that they work. To be fair, I fall precisely in these apps’ prime demographics -- 20-something, female, active online. Yet I’ve found myself drawn to them much more quickly than I’d have liked, in large part because my pictures really do look better. And every other photo looks worse.

After browsing the FaceTune-tweaked portraits on Instagram, and editing a few of my own, I’m horrified to see the photos I’ve shared on Facebook in the past. I have blotchy skin in one picture, and I’m too pale in another. Red eyes! Too-yellow teeth! The selfie-enhancers set a new baseline for photo perfection, and unlike Instagram filters, the face fixing happens covertly, without any acknowledgment of the divine digital intervention.

It seems inevitable we'll face even more fictions from each other online. But then the high-schooler from New York tells me a story about her friends that suggests there may be a strange authenticity to our photo fakery as well. She recounts how one of her friends asked her if another girl had tried to make herself look skinnier by blurring her waist in a bikini photo she’d uploaded to Facebook. (Indeed, the girl had.)

“I cringed when I heard that story today,” the 18-year-old told me. “Her insecurities are exposed.”

In the images where the selfie-enhancement isn’t done so carefully, and the cheek is just a tad off or smile a bit over-stretched, you learn more about a person than an unaltered photo ever could have revealed, and more than they’d ever want to admit on social media: In our effort to fix everything, we reveal what isn’t going right.

The HuffPostTech team, "perfected" with Pixtr.

She’s a stunning lady. But the photo, I learned later, was in fact “#toogorgeous” to be true: She’d had some digital work done.

My friend, like millions of others online, had spruced up her selfie with Perfect365, a free app that lets people instantly smooth skin, excise zits, highlight eyes and even resize noses before sending their image out on the Internet.

Perfect365 belongs to a growing breed of selfie-help apps, like FaceTune, ModiFace, Pixtr and Visage Lab, that let anyone with fingers and a smartphone transform basic snapshots into flawless Annie Leibovitz portraits (Buzzfeed’s John Herrman dubs this “selfie surgery.”) Eyelashes can be added, teeth whitened, smiles stretched, pounds shed, clocks reversed, genes fought. And artfully, too: unlike the previous generation of portrait-editing apps, which left figures with the two-dimensional masks of anime characters, these apps, like the best plastic surgeon, leave few obvious marks. I, for one, would never have guessed the #carselfie had a little help.

Perfect365 in action. Users must first align their face with "KeyPoints," then can choose a range of effects, from adding false eyelashes and sweeping on blush to evening out skintones and whitening teeth.

While many claim social media has provided a more authentic and unvarnished view into people’s lives, the popularity of these selfie-help apps suggests precisely the opposite. We’ve always cherry-picked what we share online, but more than ever, what you see isn’t what you get. Even as people use Snapchat to share silly photos that, crucially, disappear after a few seconds, those same social media users are delighting in new ways to edit their lives and present an ever-more perfected, artificial image of their world. We’re hungry for ways to exert more control over our images, not less. And who’s to blame us? The rise of selfie-help represents a new way for people to cope with the relentless judgment of the web and the pressure to disclose more online. It also hints at the start of an airbrushing arms race that could make impossibly attractive photos the norm.

“There’s definitely more pressure to have a better version of yourself or put your best foot forward,” said Caroline Tien-Spalding, director of consumer marketing at ArcSoft, Perfect365’s parent company. “You don’t know how long that photo is going to live or how long the impression that you’re putting out there will last.”

While selfies have lost their stigma, these selfie-help apps are still taboo. Just 50,000 Instagram photos have been tagged #Perfect365 -- mostly people playing with the app's makeup filters for dramatic effect -- but the app has been downloaded 17 million times since its launch two years ago. People’s reluctance to acknowledge the handiwork of their digital dermatologists hasn’t much hampered the success of this type of app: ModiFace’s suite of about 20 editing apps have been installed nearly 27 million times, and FaceTune, since its debut this past March, has topped Apple’s rankings as the most popular paid app in 69 countries, including the U.S.

These selfie-enhancers skew toward teens and 20-somethings, who are highly active on social media, and are also overwhelmingly female. Seventy percent of the users of FaceTune, which its creators, perhaps naively, thought was “gender neutral,” are female. And two-thirds of Perfect365’s users are under 24 years old.

The pictures end up on dating profiles, Instagram, Facebook or even Christmas cards. (The chief executive of ModiFace said there’s always a bump in downloads around the holidays.) An 18-year-old high-school student in New York, who declined to be named to protect her privacy and her friends’, said that nine out of ten female friends quietly edit their Facebook profile photos before they’re uploaded, sometimes making an arm look skinnier or blurring a double chin, other times just tweaking the lighting to make it more flattering.

“I’ve had phone calls where girls will ask me to go on iChat and send me four different versions of the same picture -- with different lighting, with different skin," she said. Among her peers, iPhoto’s suite of tools is still the most popular, she said.

Much as in real life, the only thing worse than looking zitty, wrinkled and tired is looking like you’ve sought help. If you get caught editing a photo, “it’s very embarrassing,” the 18-year-old said. “People are hyperaware of not wanting to seem fake in their pictures. As much as they edit them, it has to come off as natural.”

FaceTune's "Patch" tool in action.

Though Perfect365 offers a range of dramatic makeup styles, with names like “Enchant,” or “Ocean,” the app’s most natural-looking filter, which gently evens skin tones, is the most popular. (According to ArcSoft, 80 percent of people either use the "Natural" filter or custom settings.) The co-creator of FaceTune, Nir Pochter, agreed that most of their users opt for only minor improvements, like whiter teeth or fewer pimples, that don’t reveal any futzing with the photo.

“My impression from our users is that they want to look in all their photos how they know they can look, because they saw it in their best photos,” he said.

Jacqui Adkins, a 29-year-old FaceTune fan from South Amherst, Ohio, recently used the app to spruce up a shot of herself and her 7-year-old son. She touched up her skin, covered up a scratch on her son’s chin and then made the picture her Facebook profile photo. The appeal, she said, was that she could subtly fix temporary flaws caused by a breakout or poor lighting.

Another FaceTune aficionado, Jennifer Brewer, 32, said she sees the apps as a necessary response to flawless Photoshopped fashion spreads. She doesn’t have great skin, she conceded, and the app lets her “even the playing field.”

“We live in a world where everything you see on TV or in a magazine is edited to make a person look great,” Brewer wrote in an email. “I want to look good too.”

So may everyone else. Even with a small fraction of Facebook and Instagram’s users currently morphing their photos, it’s clear these apps have the potential to make touching up de rigueur, so that every casual snapshot has the polish of a Vogue photo shoot. Sebastian Thrun, the co-founder of Google X, told me in an interview last year that he imagined technology like Google Glass, with its ever-present camera, could push us to share photos that are “uglier” and “more personal.” Instead, a contradictory trend is in motion: our pictures are getting prettier.

These apps are attractive for the simple reason that they work. To be fair, I fall precisely in these apps’ prime demographics -- 20-something, female, active online. Yet I’ve found myself drawn to them much more quickly than I’d have liked, in large part because my pictures really do look better. And every other photo looks worse.

After browsing the FaceTune-tweaked portraits on Instagram, and editing a few of my own, I’m horrified to see the photos I’ve shared on Facebook in the past. I have blotchy skin in one picture, and I’m too pale in another. Red eyes! Too-yellow teeth! The selfie-enhancers set a new baseline for photo perfection, and unlike Instagram filters, the face fixing happens covertly, without any acknowledgment of the divine digital intervention.

It seems inevitable we'll face even more fictions from each other online. But then the high-schooler from New York tells me a story about her friends that suggests there may be a strange authenticity to our photo fakery as well. She recounts how one of her friends asked her if another girl had tried to make herself look skinnier by blurring her waist in a bikini photo she’d uploaded to Facebook. (Indeed, the girl had.)

“I cringed when I heard that story today,” the 18-year-old told me. “Her insecurities are exposed.”

In the images where the selfie-enhancement isn’t done so carefully, and the cheek is just a tad off or smile a bit over-stretched, you learn more about a person than an unaltered photo ever could have revealed, and more than they’d ever want to admit on social media: In our effort to fix everything, we reveal what isn’t going right.

The HuffPostTech team, "perfected" with Pixtr.

Published on December 05, 2013 13:36

November 18, 2013

Inside The One-Man Intelligence Unit That Exposed The Secrets And Atrocities Of Syria's War

There was something strange about the rockets that landed on Zamalka, a town south of Syria's capital, just after two in the morning on Aug. 21. They didn't explode. Yet even lodged into walls of homes or injected into the dirt fully intact, they proved lethal. Hundreds of people sleeping near the landing sites were killed instantly and bloodlessly, as if choked by invisible hands. A cloud of death spread quietly, ending hundreds of other lives.

Just after dawn the following day, Muhammed al-Jazaeri, a 27-year-old engineer who had joined a coalition of activists fighting to take down the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, felt an urge to document what had occurred. He found one of the rockets protruding from a patch of orange dirt behind a mosque a mile from his home. Recalling later that he was determined to reveal to the world the "real picture" of life in Syria, he used a handheld Sony camera to capture a short video of its twisted remains. That same day, he uploaded his clip to a site that has become an intelligence hub for war-watchers and a time-killing venue for bored teenagers: He sent it to YouTube.

Several hours later and 2,300 miles to the northwest in Leicester, England, a shaggy-haired blogger named Eliot Higgins peered at his laptop and clicked play on al-Jazaeri's video. It was one of scores Higgins turned up that day as he trawled Twitter, Google+ and the more than 600 Syrian YouTube accounts he monitors daily. From his living room, Higgins was racing to solve the same whodunit confronting world leaders amid claims that Assad had unleashed chemical weapons against rebel sympathizers in the suburbs of Damascus. Was Zamalka a victim of such an attack? If so, who was responsible for the deed?

On paper, Higgins -- a 34-year-old with a 2-year-old daughter -- brought no credentials for the job. He had no formal intelligence training or security clearance that gave him access to classified documents. He could not speak or read Arabic. He had never set foot in the Middle East, unless you count the time he changed planes in Dubai en route to Manila, or his trip to visit his in-laws in Turkey.

Yet in the 18 months since Higgins had begun blogging about Syria, his barebones site, Brown Moses, had become the foremost source of information on the weapons used in Syria's deadly war. Using nothing more sophisticated than an Asus laptop, he had uncovered evidence of weapons imported into Syria from Iran. He had been the first person to identify widely-banned cluster bombs deployed by Syrian forces. By The New York Times' own admission, his findings had offered a key tip that helped the newspaper prove that Saudi Arabia had funneled arms to opposition fighters in Syria.

His work unraveling the mystery of the rocket strikes of Aug. 21 played a key role in bringing much of the world to the conclusion that it was indeed a chemical weapons attack, one unleashed by Assad's forces. That conclusion led to a diplomatic deal under which the Syrian government submitted to international inspections and pledged to destroy its stocks of chemical weapons.

"I saw the U.N. got the Nobel Prize for Syria," says one weapons expert, referring to the United Nations-backed Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, who declined to be named on account of his own work with the international body. "I think Eliot has done a lot more for Syria than the U.N."

Higgins belongs to an obsessive coterie of self-appointed military intelligence experts who use social media to piece together critical details of faraway conflicts, often well ahead of seasoned professionals. Frequently self-taught and operating far outside the military-industrial complex, these amateur analysts have honed a novel set of sleuthing skills that fuse old-fashioned detective work with new sources of intelligence generated by cell phone cameras and spread by social networks. Syria's war, widely considered the most documented conflict in history, has turned social media into a weapon of mass detection -- critical both for fighters on the ground and for faraway observers trying to make sense of the conflict.

"All parties to the conflict in Syria realize that social media is an important front in this war," says Peter Bouckaert, an expert in humanitarian crises and the emergencies director for Human Rights Watch. "There is a war for the truth as much as for territory."

Many government agencies, private research groups and newsrooms are still wary of analyses based on the Facebook status updates or viral videos of Syria's opposition groups. Such "open source intelligence" -- so-called by the U.S. military -- is deeply biased and difficult to verify, its critics say, often amounting to meaningless chatter.

"I personally don't really have the time to go through the social media in Syria so as to start knowing which sources, which sites, which media, which individuals are credible or not," said Yezid Sayigh, a senior associate at the Carnegie Middle East Center. "All that takes time and continuous follow up. "

But in an age in which social media produces seemingly limitless streams of information, some people are proving obsessive enough to go rooting through it all in search of small nuggets of undiscovered reality. People like Higgins.

After a temporary job reviewing orders at a ladies' lingerie maker came to an end in February, he dispensed with looking for another so that he could devote himself to blogging full-time. His wife admits she does not read his blog and yearns for a time that he will return to "a real job." But as Higgins sees it, he is consumed with the realest job of all, sifting through a digital goldmine disdained by those who lack the patience for the work.

"If you're in intelligence and you want to know what your enemies are armed with, just watch their YouTube channels and see what weapons they're waving around," he advises. "You'll find out all sorts of information -- and not necessarily the stuff they intend to show you."

The YouTube video uploaded by al-Jazaeri.

***

Higgins operates from his command center in a narrow, two-story home just down the street from a Salvation Army and a community center, in a town about 100 miles north of London. His "office" alternates between a cream leather couch in the living room and an Ikea chair with a lap desk in an upstairs bedroom. His standard uniform is jeans and white T-shirts layered with dark-colored V-necks.

Born in 1979 to a Royal Air Force engineer and a caterer, Higgins describes himself as an avid gardener and budding cook, but his core passions have always centered on a fascination with screens: During his schooling years, he engaged in marathon sessions playing video games and argued ceaselessly on Internet forums. These two pursuits trumped his attention to schoolwork, filling his report cards with Cs.

Throughout his life, Higgins has taken hobbies to illogical extremes. After his brother introduced him to the iconoclastic rockstar Frank Zappa, Higgins rushed out to buy all of his four-dozen albums. As a video gamer, Higgins pressed well past casual bouts of "World of Warcraft," staying up late to lead teams of 40 players in complex online raids. Even now, he feels compelled to systematically beat each new video game before he can start another, in this fashion gradually making his way through strategy and role-playing games like "Fallout," "Baldur's Gate," "Total War: Rome II" and "Command and Conquer." Before getting married, he was known to game for 36 hours at a stretch.

"It's like he's got tunnel vision," says Higgins' brother, Ross. "He latches onto something and gets kind of obsessed about it. Most people don't think like my brother does."

After dropping out of university midway through a media studies degree, Higgins moved through a series of jobs with no relation to munitions, Syria or blogging. He worked as a data entry clerk at Barclays bank and then managed invoices for a process management firm. When that task was outsourced overseas, he helped asylum seekers find housing. His next, and most recent, job was working on women's undergarments.

Yet in his off hours, Higgins morphed into "Brown Moses," a fastidious online commenter who challenged strangers to heated debates over protests in Egypt or the veracity of videos showing civilians shot down in Libya. He took his alias from a Zappa song and his avatar from a portrait by Francis Bacon of the howling Pope Innocent X flanked by animal carcasses.

"I was always interested in that sort of counterculture stuff," Higgins says. He lists as his favorite authors Naomi Klein, Noam Chomsky and Nick Davies.

Higgins also brought a longstanding interest in media and American policy in the Middle East. He attacked this interest, like every other, with a fanatic intensity. In 2011, "Brown Moses" became an active voice in the online comments section of the British newspaper The Guardian. Almost as soon as The Guardian would publish a new story on its website touching on the Middle East, "Brown Moses" would be the first to leave a comment. Initially, this was purely by chance; later, as Higgins confesses, he would get there first just to annoy people irked by his obsessiveness. By latest count, Higgins has left a total of 4,700 comments on The Guardian's site. That's just a fraction of his activity on Something Awful, one of the oldest forums on the web and a favorite of Higgins' for more than a decade. In just over two years, he posted 10,000 times to a live-blog chronicling the twists and turns of Libya's revolution.

"I just got obsessed with it," Higgins says.

But what drove this obsession -- Idealism? Politics?

"Boredom at work more than anything," Higgins says. "And I guess I'm a bit argumentative."

It was an online argument that got Higgins mulling over the idea of a blog. A Guardian commenter challenged him to prove that a certain protest had actually been filmed in Libya. In piecing together evidence from satellite images and social media, Higgins experienced a series of epiphanies.

When viewed in isolation, the micro-dispatches posted to Twitter, Facebook and YouTube tended to confuse and overwhelm anyone trying to make sense of events. But if you viewed such posts together, Higgins realized, the photos and videos could yield detailed accounts of events across the globe. The posts could be used to fact check claims, providing clues far beyond what cameramen had intended to show. Arguments could be won, myths disproved, rival commenters put in their place.

Most people were failing to scrutinize such material in a systematic fashion. The answers to big questions were out there -- such as which rebel groups were working together, what guns they carried, and how much force they could rally against Assad. Yet confronted with so many thousands of videos and contrasting depictions, observers threw up their hands. Too much information became no information. Journalists and analysts lacked time to dissect YouTube clips, or figured there was nothing to gain there. Higgins came to recognize a form of "snobbery" and "dismissiveness" toward social media, which meant that crucial evidence was disappearing into a morass of "likes," tweets, shares, uploads and updates.

In the spring of 2012, Higgins created a small site, Brown Moses, where he could save some of this digital material for his own future reference. A pet project, nothing more.

He fell into a routine of writing about weapons purely out of convenience. His early blogs were less focused, ranging from analyses of the Murdoch phone hacking scandal to a critique of a tasteless tweet. Drawn to the action in the Middle East but unable to speak Arabic, Higgins was attracted to analyzing munitions videos, which transcended all languages.

Higgins also craved daily fodder for his blog, and it seemed every day he delivered a newsworthy video about rocket launchers or warheads in Syria, a country then becoming more volatile. In the course of just three days in July 2012, for example, Higgins' blog posts included the following: evidence of an increasingly well-armed Free Syrian Army packing heavy assault rifles and truck-mounted Soviet machine guns; videos of al-Farouq Brigades rebels showing off tanks captured from the Syrian Army; and documentation that Syrians were being hit with cluster bombs, controversial and widely-outlawed munitions that pose high risks to civilians.

Higgins got a rush from being the first to spot things that no one -- outside, perhaps, Assad's army -- knew existed. And it helped that with each month, more and more powerful people were taking their talking points from his blog. Even before the attacks this past August, Higgins' audience had grown to include members of the Defense Department, the State Department, the United Nations, the U.K. Foreign Commonwealth Office, Turkey's National Intelligence Organization, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, The New York Times, The Guardian, as well as countless think tanks and Russia's state-run news channel.

"Brown Moses has been carrying a lot of hod in the coverage of the Syrian war," CJ Chivers, a New York Times reporter covering Syria, wrote on his personal website in the summer of 2012. "So c'mon, let's say it: Many people (whether they admit it or not) have been relying on that blog's daily labor to cull the uncountable videos that circulate from the conflict." (Chivers himself had based a story for the Times in part on Higgins' work tracking Yugoslav weapons in Syria.)

In April 2013, Chivers delivered another endorsement, providing a promotional blurb that Higgins used as he raised funds -- about $17,000 -- so he could support his family while devoting himself to the blog full-time. He raised the sum quickly. Half came from the crowdfunding site Indiegogo, and the other half from an anonymous donor. Higgins also began picking up occasional contract work doing social media forensics for groups that track weapons use overseas, like Human Rights Watch and Action on Armed Violence.

Still, six months after his fundraising campaign, Higgins was having doubts he could pay his mortgage analyzing YouTube videos. He figured he had just a few months of finance left before he once again needed to find the steady income of a full-time job.

Yet in the course of Brown Moses' lifetime, Higgins has created an indispensable news source by doing what no news organization can: devoting virtually unlimited time to digging through the endless detritus of YouTube in the hopes of possibly coming up with something interesting to say on some or another niche topic. And he shares his loot. Unlike journalists, who guard their scoops, Higgins works like an open source Sherlock Holmes, asking questions, bouncing ideas off other people, soliciting tips and generally thinking out loud.

The obsessiveness that has framed much of his life has a new channel. He spends his days on seemingly arcane minutiae -- analyzing the welding on the lip of a rocket, reconstructing how metal folds over the edge of a warhead's column, compiling endless YouTube playlists, or clicking play-pause-play-rewind-play in rapid succession on numerous videos to freeze the precise moment when a blurry rocket appears for just a few seconds in Syria's sky.

"I love it when there's a new bomb used in the combat," Higgins says. "Well, not love. But I see a new bomb and I'm like, 'Oh! Great! There's something new to look at.'"

****

The morning of Aug. 21 delivered something new to look at. Something so new, no one knew what it was.

Like most mornings, this one began with Higgins reaching for his Nexus 4 smartphone while still in bed so he could check Twitter before getting up to care for his daughter. His Twitter stream was full of frantic dispatches claiming that a chemical weapons attack had been directed at several suburbs of Damascus, killing what seemed an impossibly large number of people -- more than 1,000. After Higgins had downed a black coffee, changed and fed his daughter, his wife, Nuray, took over. Nuray, who is Turkish and works part-time at a post office, happened to be home that day, and she tended to their daughter so Higgins could watch YouTube videos in peace.

While his daughter played, Higgins settled on the couch in his living room and quickly assembled nearly 200 videos of the victims into a YouTube playlist. He sent his findings to chemical weapons experts he'd come to know in the course of writing his blog, asking them to opine on whether these clips were consistent with a nerve gas strike. Probably so, the experts agreed, but they could not say definitively. The world would have to wait for the United Nations to test samples collected from Syria.

Waiting was the last thing Higgins planned to do. As he saw it, a "ridiculously huge" number of people had been killed, and no one knew how, or by whom. Waiting seemed tantamount to letting a criminal get a head start. There was also the issue of nerve gas. If chemical weapons had been used in the attack, the party responsible had violated nothing less than an international ban on munitions "justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilized world," in the words of the Geneva Protocol. And the stakes could not have been higher. President Barack Obama had declared that chemical weapons usage constituted a red line that, if crossed, could trigger American military intervention. That moment was potentially at hand.

Higgins sees his one-man intelligence unit as a vital source of information for the general public -- more in depth than any newspaper article, but more open than any think tank or government agency. The world needed answers, and he was singularly able to help find them. "I can't imagine there are many people in the world who know more about this than I do," he says matter-of-factly. "It became my mission to find out everything about these things because no one knew anything."

That day and into the next, his research surfaced hundreds more videos, including Muhammed al-Jazaeri's video clip from Zamalka.

The photos and videos Higgins tracks down online are posted by scores of different sources in Syria: armed rebel groups, like the Environs of the Holy House Battalions, Ahrar al-Sham and Liwa al-Islam; local news outlets run by the opposition, like "Darya Revolution," "Erbin City," "Ugarit News" and the "Adra News Network"; and individual activists, like al-Jazaeri. Thanks to this near-real-time feed, Higgins can describe activity in Syria as if he'd seen it from his own window. "Today there's been a lot of mid-29s flying around Damascus," he observed recently from the security of his kitchen table.

The proliferation of this material attests to how Syria's opposition has embraced social media as a PR tool, a form of subterfuge, a propaganda apparatus and a crucial fundraising mechanism. Activists and armed battalions have assembled a sophisticated media arsenal, having long ago realized that their online presence can affect their offline success in forging alliances, raising funds and securing weapons. Their press offices carry out online brand-building campaigns complete with up-to-the-minute press releases and carefully edited highlight reels of successful attacks. The social media guru is the newest recruit in the fighting army.

"It's sort of like a social media arms race," said Nate Rosenblatt, an analyst for Caerus Associates, a research and advisory firm. "They continuously try to innovate and improve on the uses and purposes of social media to stay ahead of their opponents and gain an advantage."

The Free Syrian Army unit Suqur al-Sham, for example, boasts a media staff of eight. In addition to keeping up a steady stream of posts on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, it maintains three dedicated websites and last year added training in social networking for Suqur al-Sham press staff. Its YouTube channel -- like those of many other rebel groups -- features clips of soldiers leading attacks on enemy outposts. Most follow a predictable formula. There's a close-up of men firing machine guns or loading warheads into rocket launchers, then a cut to the target being destroyed with off-camera voices shouting "Allahu Akbar" ("God is great").

A promotional video, "The Age of Peace is Over," uploaded in June 2013 by the Al-Islam brigade, an opposition group in Syria. (via Syria Conflict Monitor)

With so many Syrian opposition groups vying for dominance, rebels have used these videos as a kind of resume-booster intended to show off their strength and brand them as heir-apparent to the Assad regime. Brigades also hope their highlight reels -- often meticulously edited with Instagram-style filters and custom animation -- will convince wealthy, sympathetic donors to part with their cash. For Higgins and other armchair analysts like him, these videos serve a very different purpose: They can offer valuable glimpses at what weapons are being used in battle, or who's leading the charge.

Professional analysts often discount this kind of footage because so much of it can be faked. One opposition group's footage of a Syrian Army helicopter shot down mid-air, for example, turned out to be a video of a Russian craft that had been filmed in the Chechen conflict.

But Higgins is undeterred, having refined his skill in separating the real from the bogus. He has determined that not all social media is created equally. Tweets and Facebook posts are no good because text is far easier to fake than photos. He distrusts footage of casualties or bombed-out buildings.

"People will say, 'Oh well that person just wrapped bandage around their head, they're faking it,'" Higgins says. "And, you know, fair enough. But when you've got an unexploded bomb stuck inside of someone's house, that's a lot harder to fake."

He was immediately suspicious when an anonymous tipster sent videos purporting to show Liwa al-Islam, an opposition group, firing chemical weapons on Aug. 21. Liwa al-Islam produces high-quality videos, but these had been filmed on a blurry cell phone camera, Higgins said. Flags with the Liwa al-Islam emblem had been hung everywhere, also atypical for the group's videos. Then there was the issue of the T-shirts. Liquid sarin can kill through contact with skin, Higgins knew. Would these rebels really be hanging around a deadly toxin in short sleeves?

Higgins credits this attention to detail to the many years he's spent arguing with Internet commenters -- the harshest, most meticulous and most relentless critics on the planet. In martialing evidence for analysis on Brown Moses, Higgins tries to imagine every disagreement from some ticked-off stranger online, and preemptively strengthen his argument's weaknesses.

"If you want someone to really question your work, just post it on the Internet," he says. "There are plenty of people who'll want to tell you you're an idiot and you're wrong."

One of three videos Higgins says he received purporting to show Liwa al-Islam firing chemical weapons.

* * *

As Higgins trawled through videos the day after the attacks, he saw, over and over again, long, cylindrical rockets with fins on one end and a round plate on the other, and red numbers stenciled in between.

Hello, I know I've seen these before, Higgins thought. He did a mental inventory of the thousands of YouTube videos he'd watched over the preceding eight months, trying to remember where else he'd come across these hunks of metal.

Daraya, Adra, Homs, Higgins realized. He quickly pulled up videos filmed in three other cities, on four different dates between January and August, and embedded them in a blog post. The rocket he'd seen after the strike the day before had also been spotted after four separate attacks, two of which were suspected to have involved chemical weapons, he wrote.

Higgins still had no idea what it was. And neither did the arms experts he consulted. He christened the weapons UMLACAs, short for Unidentified Munitions Linked to Alleged Chemical Attacks, and began a hunt to rebuild them using everything that had been shared about them online.

His methodology recalls the card game "Memory," in which players overturn two cards at a time trying to find a pair. But instead of finding clubs or hearts, he'll try to match a mystery object -- a blurry warhead, a kind of rocket launcher -- to an image of something that's known. Earlier that month, Higgins had debunked a rumor that pouches of glass tubes, widely documented online, were proof that chemical weapons had been used in Syria. He did so by matching the vials captured in videos to photos of a Cold War-era chemical weapons testing kit for sale on eBay.

In the week following the bombing outside Damascus, Higgins spent hours a day at his computer, breaking only to feed his daughter and perhaps catch an episode of "Columbo," the detective TV series, with his wife. (Higgins says he feels like he and the TV detective are "kindred spirits in some ways.")

One crucial challenge was figuring out exactly where the rockets had landed. If Higgins could determine where a weapon had crashed, he'd have a better chance of finding where it was shot from. And, in turn, who fired it.

He zeroed in on one well-documented rocket labeled "197" that he knew, from a Twitter follower's tip, had fallen somewhere approximately between the towns of Zamalka and Ein Tarma.

To narrow that down further, he began studying images of "197" to see what landmarks he could make out in the background. He tried to sketch a rough map of the area beyond the twisted metal. A building here, an apartment there, an empty plot of land just in front. Next, he compared his makeshift diagram to satellite imagery of the Damascus suburb on Google Maps and its open-source equivalent, Wikimapia, hoping he'd find an area that matched it. It was like "finding a key and matching it to a lock," Higgins says. Imagine being given a snapshot taken at a backyard barbecue somewhere in Tacoma, and being asked to match it to a house on a map in Washington state -- an area roughly the size of Syria.

He couldn't find an exact likeness. Yet there were five images that corresponded well enough. After some back-and-forth with Syria-watchers and journalists on Google+, where Higgins often turns to ask for help and second opinions, Higgins wrote a blog post that walked through his best guess of where "197" had crashed. He presented five composite images, each juxtaposing a still taken from an activist's video with a screenshot of satellite imagery. To each, he added red lines and small numbers meant to indicate which spots matched up, along with a brief explanation.

Based on the maps and the way the rocket buckled on impact, the weapon must have been fired from the north, Higgins concluded. He didn't fail to point out what was located just 6 to 8 kilometers in that direction: a missile base belonging to the Syrian Army's 155th Brigade.

One of the images Higgins published attempting to show where rocket "197" had landed. The top picture is from satellite imagery, the bottom from a YouTube video.

* * *

On Aug. 31, 10 days after the attacks in Damascus, President Obama convened reporters in the White House Rose Garden. The United States had evidence Assad's army had fired chemical weapons on opposition groups outside the country's capital, he announced. He was calling for a military strike against Syria.

By then, Higgins had published nine stories on the attacks. He had identified not only where one of the rockets had landed, but had also shared proof that they resembled munitions used in prior suspected chemical attacks. He'd argued that the Syrian opposition's "Hell Cannon" couldn't have been used to fire rockets like those in the Aug. 21 strike; that Assad forces had been using "DIY weapons," previously linked to chemical weapons; and that United Nations inspectors in Syria had examined an artillery rocket, collected after the strikes, that could be used as a chemical warhead and loaded with more than 4 pounds of sarin gas.

He shared high-resolution photographs of activists holding a tape measure over a rocket recovered in Damascus after the attacks -- the first time anyone had offered clear measurements of the weapons. And Higgins also posted a video that showed Assad's Republican Guard -- recognizable from its red berets -- had loaded and fired munitions similar to those linked to chemical attacks.

Visitors to the Brown Moses blog had reached an all-time high, growing eightfold in the days and weeks following the attacks, from about 3,000 daily readers to more than 25,000. News networks were regularly airing videos Higgins had featured on his blog and Human Rights Watch had tapped Higgins to help compile its report on the alleged nerve gas attacks outside Damascus. The group was drawing liberally from the YouTube footage and Facebook photos he'd gathered.

What made his analysis so compelling, even to those in government or with security clearance, was its detail. While the White House's case for a chemical weapons attack had included vague references to "independent sources" and "thousands of social media reports" in the four-page document it released to the public, Higgins had pointed people directly to the sources themselves. His readers didn't have to believe rockets were fired. They could look at them in dozens of videos and photographs Higgins had compiled. The White House asked the public to trust them. Higgins' instructions? "Go see for yourself."

Higgins sympathizes with the pressures that prevent journalists from scouring social media the way he does. But he says he has little patience for political leaders and their tendency to offer vague assurances that they have proof of weapons of mass destruction -- in Iraq, in Syria, wherever -- while refusing to make the goods public.

"The U.S., U.K. and France produce a one-page report saying, 'We have this evidence, we can't show you it,'" he says. "That's frustrating in this modern era where we have access to all this open source information. People don't just want reassurances that the evidence is there. They want to see it."

Higgins plans to keep revealing it.

Even months after Obama's showdown with Syria, and after Syria's chemical weapons have largely faded from headlines, Higgins is still scouring social media to expose dark secrets and cruel acts.

"No one cares anymore because the chemical attack was two-and-a-half months ago," he says. "But I'm still looking into it. You do get the feeling there are people who have this obsessive nature. And then there are the normal people."

Just after dawn the following day, Muhammed al-Jazaeri, a 27-year-old engineer who had joined a coalition of activists fighting to take down the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, felt an urge to document what had occurred. He found one of the rockets protruding from a patch of orange dirt behind a mosque a mile from his home. Recalling later that he was determined to reveal to the world the "real picture" of life in Syria, he used a handheld Sony camera to capture a short video of its twisted remains. That same day, he uploaded his clip to a site that has become an intelligence hub for war-watchers and a time-killing venue for bored teenagers: He sent it to YouTube.

Several hours later and 2,300 miles to the northwest in Leicester, England, a shaggy-haired blogger named Eliot Higgins peered at his laptop and clicked play on al-Jazaeri's video. It was one of scores Higgins turned up that day as he trawled Twitter, Google+ and the more than 600 Syrian YouTube accounts he monitors daily. From his living room, Higgins was racing to solve the same whodunit confronting world leaders amid claims that Assad had unleashed chemical weapons against rebel sympathizers in the suburbs of Damascus. Was Zamalka a victim of such an attack? If so, who was responsible for the deed?

On paper, Higgins -- a 34-year-old with a 2-year-old daughter -- brought no credentials for the job. He had no formal intelligence training or security clearance that gave him access to classified documents. He could not speak or read Arabic. He had never set foot in the Middle East, unless you count the time he changed planes in Dubai en route to Manila, or his trip to visit his in-laws in Turkey.

Yet in the 18 months since Higgins had begun blogging about Syria, his barebones site, Brown Moses, had become the foremost source of information on the weapons used in Syria's deadly war. Using nothing more sophisticated than an Asus laptop, he had uncovered evidence of weapons imported into Syria from Iran. He had been the first person to identify widely-banned cluster bombs deployed by Syrian forces. By The New York Times' own admission, his findings had offered a key tip that helped the newspaper prove that Saudi Arabia had funneled arms to opposition fighters in Syria.

His work unraveling the mystery of the rocket strikes of Aug. 21 played a key role in bringing much of the world to the conclusion that it was indeed a chemical weapons attack, one unleashed by Assad's forces. That conclusion led to a diplomatic deal under which the Syrian government submitted to international inspections and pledged to destroy its stocks of chemical weapons.

"I saw the U.N. got the Nobel Prize for Syria," says one weapons expert, referring to the United Nations-backed Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, who declined to be named on account of his own work with the international body. "I think Eliot has done a lot more for Syria than the U.N."

Higgins belongs to an obsessive coterie of self-appointed military intelligence experts who use social media to piece together critical details of faraway conflicts, often well ahead of seasoned professionals. Frequently self-taught and operating far outside the military-industrial complex, these amateur analysts have honed a novel set of sleuthing skills that fuse old-fashioned detective work with new sources of intelligence generated by cell phone cameras and spread by social networks. Syria's war, widely considered the most documented conflict in history, has turned social media into a weapon of mass detection -- critical both for fighters on the ground and for faraway observers trying to make sense of the conflict.

"All parties to the conflict in Syria realize that social media is an important front in this war," says Peter Bouckaert, an expert in humanitarian crises and the emergencies director for Human Rights Watch. "There is a war for the truth as much as for territory."

Many government agencies, private research groups and newsrooms are still wary of analyses based on the Facebook status updates or viral videos of Syria's opposition groups. Such "open source intelligence" -- so-called by the U.S. military -- is deeply biased and difficult to verify, its critics say, often amounting to meaningless chatter.

"I personally don't really have the time to go through the social media in Syria so as to start knowing which sources, which sites, which media, which individuals are credible or not," said Yezid Sayigh, a senior associate at the Carnegie Middle East Center. "All that takes time and continuous follow up. "

But in an age in which social media produces seemingly limitless streams of information, some people are proving obsessive enough to go rooting through it all in search of small nuggets of undiscovered reality. People like Higgins.

After a temporary job reviewing orders at a ladies' lingerie maker came to an end in February, he dispensed with looking for another so that he could devote himself to blogging full-time. His wife admits she does not read his blog and yearns for a time that he will return to "a real job." But as Higgins sees it, he is consumed with the realest job of all, sifting through a digital goldmine disdained by those who lack the patience for the work.

"If you're in intelligence and you want to know what your enemies are armed with, just watch their YouTube channels and see what weapons they're waving around," he advises. "You'll find out all sorts of information -- and not necessarily the stuff they intend to show you."

The YouTube video uploaded by al-Jazaeri.

***

Higgins operates from his command center in a narrow, two-story home just down the street from a Salvation Army and a community center, in a town about 100 miles north of London. His "office" alternates between a cream leather couch in the living room and an Ikea chair with a lap desk in an upstairs bedroom. His standard uniform is jeans and white T-shirts layered with dark-colored V-necks.

Born in 1979 to a Royal Air Force engineer and a caterer, Higgins describes himself as an avid gardener and budding cook, but his core passions have always centered on a fascination with screens: During his schooling years, he engaged in marathon sessions playing video games and argued ceaselessly on Internet forums. These two pursuits trumped his attention to schoolwork, filling his report cards with Cs.

Throughout his life, Higgins has taken hobbies to illogical extremes. After his brother introduced him to the iconoclastic rockstar Frank Zappa, Higgins rushed out to buy all of his four-dozen albums. As a video gamer, Higgins pressed well past casual bouts of "World of Warcraft," staying up late to lead teams of 40 players in complex online raids. Even now, he feels compelled to systematically beat each new video game before he can start another, in this fashion gradually making his way through strategy and role-playing games like "Fallout," "Baldur's Gate," "Total War: Rome II" and "Command and Conquer." Before getting married, he was known to game for 36 hours at a stretch.

"It's like he's got tunnel vision," says Higgins' brother, Ross. "He latches onto something and gets kind of obsessed about it. Most people don't think like my brother does."

After dropping out of university midway through a media studies degree, Higgins moved through a series of jobs with no relation to munitions, Syria or blogging. He worked as a data entry clerk at Barclays bank and then managed invoices for a process management firm. When that task was outsourced overseas, he helped asylum seekers find housing. His next, and most recent, job was working on women's undergarments.

Yet in his off hours, Higgins morphed into "Brown Moses," a fastidious online commenter who challenged strangers to heated debates over protests in Egypt or the veracity of videos showing civilians shot down in Libya. He took his alias from a Zappa song and his avatar from a portrait by Francis Bacon of the howling Pope Innocent X flanked by animal carcasses.

"I was always interested in that sort of counterculture stuff," Higgins says. He lists as his favorite authors Naomi Klein, Noam Chomsky and Nick Davies.

Higgins also brought a longstanding interest in media and American policy in the Middle East. He attacked this interest, like every other, with a fanatic intensity. In 2011, "Brown Moses" became an active voice in the online comments section of the British newspaper The Guardian. Almost as soon as The Guardian would publish a new story on its website touching on the Middle East, "Brown Moses" would be the first to leave a comment. Initially, this was purely by chance; later, as Higgins confesses, he would get there first just to annoy people irked by his obsessiveness. By latest count, Higgins has left a total of 4,700 comments on The Guardian's site. That's just a fraction of his activity on Something Awful, one of the oldest forums on the web and a favorite of Higgins' for more than a decade. In just over two years, he posted 10,000 times to a live-blog chronicling the twists and turns of Libya's revolution.

"I just got obsessed with it," Higgins says.

But what drove this obsession -- Idealism? Politics?

"Boredom at work more than anything," Higgins says. "And I guess I'm a bit argumentative."

It was an online argument that got Higgins mulling over the idea of a blog. A Guardian commenter challenged him to prove that a certain protest had actually been filmed in Libya. In piecing together evidence from satellite images and social media, Higgins experienced a series of epiphanies.

When viewed in isolation, the micro-dispatches posted to Twitter, Facebook and YouTube tended to confuse and overwhelm anyone trying to make sense of events. But if you viewed such posts together, Higgins realized, the photos and videos could yield detailed accounts of events across the globe. The posts could be used to fact check claims, providing clues far beyond what cameramen had intended to show. Arguments could be won, myths disproved, rival commenters put in their place.

Most people were failing to scrutinize such material in a systematic fashion. The answers to big questions were out there -- such as which rebel groups were working together, what guns they carried, and how much force they could rally against Assad. Yet confronted with so many thousands of videos and contrasting depictions, observers threw up their hands. Too much information became no information. Journalists and analysts lacked time to dissect YouTube clips, or figured there was nothing to gain there. Higgins came to recognize a form of "snobbery" and "dismissiveness" toward social media, which meant that crucial evidence was disappearing into a morass of "likes," tweets, shares, uploads and updates.

In the spring of 2012, Higgins created a small site, Brown Moses, where he could save some of this digital material for his own future reference. A pet project, nothing more.

He fell into a routine of writing about weapons purely out of convenience. His early blogs were less focused, ranging from analyses of the Murdoch phone hacking scandal to a critique of a tasteless tweet. Drawn to the action in the Middle East but unable to speak Arabic, Higgins was attracted to analyzing munitions videos, which transcended all languages.

Higgins also craved daily fodder for his blog, and it seemed every day he delivered a newsworthy video about rocket launchers or warheads in Syria, a country then becoming more volatile. In the course of just three days in July 2012, for example, Higgins' blog posts included the following: evidence of an increasingly well-armed Free Syrian Army packing heavy assault rifles and truck-mounted Soviet machine guns; videos of al-Farouq Brigades rebels showing off tanks captured from the Syrian Army; and documentation that Syrians were being hit with cluster bombs, controversial and widely-outlawed munitions that pose high risks to civilians.

Higgins got a rush from being the first to spot things that no one -- outside, perhaps, Assad's army -- knew existed. And it helped that with each month, more and more powerful people were taking their talking points from his blog. Even before the attacks this past August, Higgins' audience had grown to include members of the Defense Department, the State Department, the United Nations, the U.K. Foreign Commonwealth Office, Turkey's National Intelligence Organization, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, The New York Times, The Guardian, as well as countless think tanks and Russia's state-run news channel.

"Brown Moses has been carrying a lot of hod in the coverage of the Syrian war," CJ Chivers, a New York Times reporter covering Syria, wrote on his personal website in the summer of 2012. "So c'mon, let's say it: Many people (whether they admit it or not) have been relying on that blog's daily labor to cull the uncountable videos that circulate from the conflict." (Chivers himself had based a story for the Times in part on Higgins' work tracking Yugoslav weapons in Syria.)

In April 2013, Chivers delivered another endorsement, providing a promotional blurb that Higgins used as he raised funds -- about $17,000 -- so he could support his family while devoting himself to the blog full-time. He raised the sum quickly. Half came from the crowdfunding site Indiegogo, and the other half from an anonymous donor. Higgins also began picking up occasional contract work doing social media forensics for groups that track weapons use overseas, like Human Rights Watch and Action on Armed Violence.

Still, six months after his fundraising campaign, Higgins was having doubts he could pay his mortgage analyzing YouTube videos. He figured he had just a few months of finance left before he once again needed to find the steady income of a full-time job.

Yet in the course of Brown Moses' lifetime, Higgins has created an indispensable news source by doing what no news organization can: devoting virtually unlimited time to digging through the endless detritus of YouTube in the hopes of possibly coming up with something interesting to say on some or another niche topic. And he shares his loot. Unlike journalists, who guard their scoops, Higgins works like an open source Sherlock Holmes, asking questions, bouncing ideas off other people, soliciting tips and generally thinking out loud.

The obsessiveness that has framed much of his life has a new channel. He spends his days on seemingly arcane minutiae -- analyzing the welding on the lip of a rocket, reconstructing how metal folds over the edge of a warhead's column, compiling endless YouTube playlists, or clicking play-pause-play-rewind-play in rapid succession on numerous videos to freeze the precise moment when a blurry rocket appears for just a few seconds in Syria's sky.

"I love it when there's a new bomb used in the combat," Higgins says. "Well, not love. But I see a new bomb and I'm like, 'Oh! Great! There's something new to look at.'"

****

The morning of Aug. 21 delivered something new to look at. Something so new, no one knew what it was.

Like most mornings, this one began with Higgins reaching for his Nexus 4 smartphone while still in bed so he could check Twitter before getting up to care for his daughter. His Twitter stream was full of frantic dispatches claiming that a chemical weapons attack had been directed at several suburbs of Damascus, killing what seemed an impossibly large number of people -- more than 1,000. After Higgins had downed a black coffee, changed and fed his daughter, his wife, Nuray, took over. Nuray, who is Turkish and works part-time at a post office, happened to be home that day, and she tended to their daughter so Higgins could watch YouTube videos in peace.

While his daughter played, Higgins settled on the couch in his living room and quickly assembled nearly 200 videos of the victims into a YouTube playlist. He sent his findings to chemical weapons experts he'd come to know in the course of writing his blog, asking them to opine on whether these clips were consistent with a nerve gas strike. Probably so, the experts agreed, but they could not say definitively. The world would have to wait for the United Nations to test samples collected from Syria.

Waiting was the last thing Higgins planned to do. As he saw it, a "ridiculously huge" number of people had been killed, and no one knew how, or by whom. Waiting seemed tantamount to letting a criminal get a head start. There was also the issue of nerve gas. If chemical weapons had been used in the attack, the party responsible had violated nothing less than an international ban on munitions "justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilized world," in the words of the Geneva Protocol. And the stakes could not have been higher. President Barack Obama had declared that chemical weapons usage constituted a red line that, if crossed, could trigger American military intervention. That moment was potentially at hand.

Higgins sees his one-man intelligence unit as a vital source of information for the general public -- more in depth than any newspaper article, but more open than any think tank or government agency. The world needed answers, and he was singularly able to help find them. "I can't imagine there are many people in the world who know more about this than I do," he says matter-of-factly. "It became my mission to find out everything about these things because no one knew anything."

That day and into the next, his research surfaced hundreds more videos, including Muhammed al-Jazaeri's video clip from Zamalka.

The photos and videos Higgins tracks down online are posted by scores of different sources in Syria: armed rebel groups, like the Environs of the Holy House Battalions, Ahrar al-Sham and Liwa al-Islam; local news outlets run by the opposition, like "Darya Revolution," "Erbin City," "Ugarit News" and the "Adra News Network"; and individual activists, like al-Jazaeri. Thanks to this near-real-time feed, Higgins can describe activity in Syria as if he'd seen it from his own window. "Today there's been a lot of mid-29s flying around Damascus," he observed recently from the security of his kitchen table.

The proliferation of this material attests to how Syria's opposition has embraced social media as a PR tool, a form of subterfuge, a propaganda apparatus and a crucial fundraising mechanism. Activists and armed battalions have assembled a sophisticated media arsenal, having long ago realized that their online presence can affect their offline success in forging alliances, raising funds and securing weapons. Their press offices carry out online brand-building campaigns complete with up-to-the-minute press releases and carefully edited highlight reels of successful attacks. The social media guru is the newest recruit in the fighting army.

"It's sort of like a social media arms race," said Nate Rosenblatt, an analyst for Caerus Associates, a research and advisory firm. "They continuously try to innovate and improve on the uses and purposes of social media to stay ahead of their opponents and gain an advantage."

The Free Syrian Army unit Suqur al-Sham, for example, boasts a media staff of eight. In addition to keeping up a steady stream of posts on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, it maintains three dedicated websites and last year added training in social networking for Suqur al-Sham press staff. Its YouTube channel -- like those of many other rebel groups -- features clips of soldiers leading attacks on enemy outposts. Most follow a predictable formula. There's a close-up of men firing machine guns or loading warheads into rocket launchers, then a cut to the target being destroyed with off-camera voices shouting "Allahu Akbar" ("God is great").

A promotional video, "The Age of Peace is Over," uploaded in June 2013 by the Al-Islam brigade, an opposition group in Syria. (via Syria Conflict Monitor)

With so many Syrian opposition groups vying for dominance, rebels have used these videos as a kind of resume-booster intended to show off their strength and brand them as heir-apparent to the Assad regime. Brigades also hope their highlight reels -- often meticulously edited with Instagram-style filters and custom animation -- will convince wealthy, sympathetic donors to part with their cash. For Higgins and other armchair analysts like him, these videos serve a very different purpose: They can offer valuable glimpses at what weapons are being used in battle, or who's leading the charge.

Professional analysts often discount this kind of footage because so much of it can be faked. One opposition group's footage of a Syrian Army helicopter shot down mid-air, for example, turned out to be a video of a Russian craft that had been filmed in the Chechen conflict.

But Higgins is undeterred, having refined his skill in separating the real from the bogus. He has determined that not all social media is created equally. Tweets and Facebook posts are no good because text is far easier to fake than photos. He distrusts footage of casualties or bombed-out buildings.

"People will say, 'Oh well that person just wrapped bandage around their head, they're faking it,'" Higgins says. "And, you know, fair enough. But when you've got an unexploded bomb stuck inside of someone's house, that's a lot harder to fake."

He was immediately suspicious when an anonymous tipster sent videos purporting to show Liwa al-Islam, an opposition group, firing chemical weapons on Aug. 21. Liwa al-Islam produces high-quality videos, but these had been filmed on a blurry cell phone camera, Higgins said. Flags with the Liwa al-Islam emblem had been hung everywhere, also atypical for the group's videos. Then there was the issue of the T-shirts. Liquid sarin can kill through contact with skin, Higgins knew. Would these rebels really be hanging around a deadly toxin in short sleeves?

Higgins credits this attention to detail to the many years he's spent arguing with Internet commenters -- the harshest, most meticulous and most relentless critics on the planet. In martialing evidence for analysis on Brown Moses, Higgins tries to imagine every disagreement from some ticked-off stranger online, and preemptively strengthen his argument's weaknesses.

"If you want someone to really question your work, just post it on the Internet," he says. "There are plenty of people who'll want to tell you you're an idiot and you're wrong."

One of three videos Higgins says he received purporting to show Liwa al-Islam firing chemical weapons.

* * *

As Higgins trawled through videos the day after the attacks, he saw, over and over again, long, cylindrical rockets with fins on one end and a round plate on the other, and red numbers stenciled in between.

Hello, I know I've seen these before, Higgins thought. He did a mental inventory of the thousands of YouTube videos he'd watched over the preceding eight months, trying to remember where else he'd come across these hunks of metal.

Daraya, Adra, Homs, Higgins realized. He quickly pulled up videos filmed in three other cities, on four different dates between January and August, and embedded them in a blog post. The rocket he'd seen after the strike the day before had also been spotted after four separate attacks, two of which were suspected to have involved chemical weapons, he wrote.

Higgins still had no idea what it was. And neither did the arms experts he consulted. He christened the weapons UMLACAs, short for Unidentified Munitions Linked to Alleged Chemical Attacks, and began a hunt to rebuild them using everything that had been shared about them online.

His methodology recalls the card game "Memory," in which players overturn two cards at a time trying to find a pair. But instead of finding clubs or hearts, he'll try to match a mystery object -- a blurry warhead, a kind of rocket launcher -- to an image of something that's known. Earlier that month, Higgins had debunked a rumor that pouches of glass tubes, widely documented online, were proof that chemical weapons had been used in Syria. He did so by matching the vials captured in videos to photos of a Cold War-era chemical weapons testing kit for sale on eBay.

In the week following the bombing outside Damascus, Higgins spent hours a day at his computer, breaking only to feed his daughter and perhaps catch an episode of "Columbo," the detective TV series, with his wife. (Higgins says he feels like he and the TV detective are "kindred spirits in some ways.")

One crucial challenge was figuring out exactly where the rockets had landed. If Higgins could determine where a weapon had crashed, he'd have a better chance of finding where it was shot from. And, in turn, who fired it.

He zeroed in on one well-documented rocket labeled "197" that he knew, from a Twitter follower's tip, had fallen somewhere approximately between the towns of Zamalka and Ein Tarma.

To narrow that down further, he began studying images of "197" to see what landmarks he could make out in the background. He tried to sketch a rough map of the area beyond the twisted metal. A building here, an apartment there, an empty plot of land just in front. Next, he compared his makeshift diagram to satellite imagery of the Damascus suburb on Google Maps and its open-source equivalent, Wikimapia, hoping he'd find an area that matched it. It was like "finding a key and matching it to a lock," Higgins says. Imagine being given a snapshot taken at a backyard barbecue somewhere in Tacoma, and being asked to match it to a house on a map in Washington state -- an area roughly the size of Syria.