Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 11

June 28, 2013

Why I Include 'Sent From My iPhone' -- Even When It's Not

On more than one occasion, I've opened up an email on my MacBook, typed out an answer and then, against my better judgment, typed out four familiar words: "Sent from my iPhone."

That's right: I've manually added the brief disclaimer that smartphone makers automatically append to emails sent from our BlackBerrys, iPhones, Galaxy handsets and HTC phones. I've even caught myself purposefully sending emails from my iPhone while sitting at my computer -- purely to get out of writing a lengthy, detailed response.

I've been embarrassed to admit the tactic (and still am), but a study highlighted this week by author and tech writer Clive Thompson suggests my deceitful behavior may be a perfectly rational insurance policy against seeming careless or incompetent in cases when I'm really just short on time or unwilling to make it. "Sent from my iPhone" is no longer just a pretentious sign-off (though it's that, too). It's acquired a more practical purpose.

The 19-character disclaimer, with its implications of movement, speed and on-the-fly response, not only excuses typos, but offers a free pass on including any sort of detail or depth to a message. The same devices we use to keep in touch with one another -- and to make ourselves available at all times -- are coming to our rescue when we want to avoid each other.

"People now see it as an excuse or cloak," said Maggie Jackson, author of Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age, of the iPhone signature. "It's definitely not only a means of communication, but it's also a means of escape from richer, deeper and in-the-face communication."

We've embraced technology's shortcomings as a way of masking our own. And though our devices aren't fail-safe, we blame them for our bad behavior far more often than is actually warranted -- usually, whenever it's convenient to do so. When someone we don't want to speak to is trying to get ahold of us, Verizon will start mysteriously dropping calls, our iPhone becomes more prone to running out of battery, Facebook will mistakenly send messages to our spam folder and the bad reception in the subway will keep their messages from coming through.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Applied Communication Research showed this technological scapegoating to be actually quite effective. After receiving a typo-addled email that he instantly pardoned upon catching sight of the iPhone sign-off, Chad Stefaniak, chair of the accounting department at Central Michigan University and the study's co-author, decided to investigate how the brief email disclaimer shapes how people perceive an individual's professionalism and competence.

Stefaniak and his co-author, Caleb Carr, showed 111 students error-ridden emails with and without "Sent from my iPhone" appended to the bottom of the message, and asked them to rate the competence and "organizational prestige" of the email's sender. They found that undergraduates forgave the errors in the email that appeared to come from a smartphone, but not the grammatical mistakes in the message that appeared to come from a desktop computer, whose sender was seen as considerably less credible than the one whose signature indicated he'd typed the email on a smartphone.

To err is human. To err on an iPhone is divine.

The results were so striking that the researchers ventured that "less scrupulous" people might append the "Sent from my iPhone" signature to their desktop correspondence as insurance against errors. (No! What monster would do such a thing?) Our tolerance of sloppy, shoddy communication via smartphones may also put us at risk for being duped by people who hope to blame their shoddy social skills on their devices.

"This forgiveness about grammar and formalized communication can overshadow the fact someone might not be good at grammar," Stefaniak noted. "The risk is that the mobile device might mask someone's true credibility. You might perceive them as credible when they're really not."

That forgiveness stems from a sense of "technological empathy," Stefaniak explains. The proliferation of personal technology -- 56 percent of Americans now have smartphones, according to the Pew Research Center -- means most people are intimately aware of the difficulties of pecking out words on a mini-keyboard or trying to look up information on a small screen. When I fake an iPhone reply, I do so with the full knowledge the recipient will recognize that it means I'm operating at a limited capacity, on a tiny touchscreen device that won't allow me to look up the detailed information he's asking for, or include any pleasantries or answer in great depth. It's not that I won't answer your irritating question, the signature implies, it's just that I can't.

Yet just as the signature can make careless answers seem more careful, it can also make careful answers seem less considered. Wary of an email being dismissed because it was sent on-the-go, I've removed the signature more often than I've kept it in. A colleague of mine observed that emails from smartphones don't seem to offer a full or credible response.

A familiarity with technology's flaws may be only part of what drives our forgiveness, however. The goodwill effect of the iPhone signature also stems from its position as a subtle marker of status and class, notes Nathan Jurgenson, a social media theorist and graduate student in sociology at the University of Maryland.

"'Sent from my iPhone,' especially in the early days of the iPhone when that signature became a cultural norm, also said, 'I'm successful, I'm of a certain class, I'm hip and modern and with it," wrote Jurgenson in an email.

Though no study has yet examined whether Android, BlackBerry and Windows Phone owners are afforded the same consideration as their iPhone-toting brethren, those distinctions could soon be meaningless: As technology improves, we may lose our roster of excuses and white lies, and be forced to be more genuine in our own communications. As the gadgets get better, we may get better.

Already, apps like Find My Friends or Google Latitude allow people to see exactly where their dinner date is when she claims she's "almost there. Google Now can alert users when traffic on their route to work means they should leave early to avoid arriving late for a meeting. If such tools continue to proliferate, old excuses like "I got lost" or "We got stuck in traffic" could become null and void.

But just in case:

--Sent from my iPhone

That's right: I've manually added the brief disclaimer that smartphone makers automatically append to emails sent from our BlackBerrys, iPhones, Galaxy handsets and HTC phones. I've even caught myself purposefully sending emails from my iPhone while sitting at my computer -- purely to get out of writing a lengthy, detailed response.

I've been embarrassed to admit the tactic (and still am), but a study highlighted this week by author and tech writer Clive Thompson suggests my deceitful behavior may be a perfectly rational insurance policy against seeming careless or incompetent in cases when I'm really just short on time or unwilling to make it. "Sent from my iPhone" is no longer just a pretentious sign-off (though it's that, too). It's acquired a more practical purpose.

The 19-character disclaimer, with its implications of movement, speed and on-the-fly response, not only excuses typos, but offers a free pass on including any sort of detail or depth to a message. The same devices we use to keep in touch with one another -- and to make ourselves available at all times -- are coming to our rescue when we want to avoid each other.

"People now see it as an excuse or cloak," said Maggie Jackson, author of Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age, of the iPhone signature. "It's definitely not only a means of communication, but it's also a means of escape from richer, deeper and in-the-face communication."

We've embraced technology's shortcomings as a way of masking our own. And though our devices aren't fail-safe, we blame them for our bad behavior far more often than is actually warranted -- usually, whenever it's convenient to do so. When someone we don't want to speak to is trying to get ahold of us, Verizon will start mysteriously dropping calls, our iPhone becomes more prone to running out of battery, Facebook will mistakenly send messages to our spam folder and the bad reception in the subway will keep their messages from coming through.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Applied Communication Research showed this technological scapegoating to be actually quite effective. After receiving a typo-addled email that he instantly pardoned upon catching sight of the iPhone sign-off, Chad Stefaniak, chair of the accounting department at Central Michigan University and the study's co-author, decided to investigate how the brief email disclaimer shapes how people perceive an individual's professionalism and competence.

Stefaniak and his co-author, Caleb Carr, showed 111 students error-ridden emails with and without "Sent from my iPhone" appended to the bottom of the message, and asked them to rate the competence and "organizational prestige" of the email's sender. They found that undergraduates forgave the errors in the email that appeared to come from a smartphone, but not the grammatical mistakes in the message that appeared to come from a desktop computer, whose sender was seen as considerably less credible than the one whose signature indicated he'd typed the email on a smartphone.

To err is human. To err on an iPhone is divine.

The results were so striking that the researchers ventured that "less scrupulous" people might append the "Sent from my iPhone" signature to their desktop correspondence as insurance against errors. (No! What monster would do such a thing?) Our tolerance of sloppy, shoddy communication via smartphones may also put us at risk for being duped by people who hope to blame their shoddy social skills on their devices.

"This forgiveness about grammar and formalized communication can overshadow the fact someone might not be good at grammar," Stefaniak noted. "The risk is that the mobile device might mask someone's true credibility. You might perceive them as credible when they're really not."

That forgiveness stems from a sense of "technological empathy," Stefaniak explains. The proliferation of personal technology -- 56 percent of Americans now have smartphones, according to the Pew Research Center -- means most people are intimately aware of the difficulties of pecking out words on a mini-keyboard or trying to look up information on a small screen. When I fake an iPhone reply, I do so with the full knowledge the recipient will recognize that it means I'm operating at a limited capacity, on a tiny touchscreen device that won't allow me to look up the detailed information he's asking for, or include any pleasantries or answer in great depth. It's not that I won't answer your irritating question, the signature implies, it's just that I can't.

Yet just as the signature can make careless answers seem more careful, it can also make careful answers seem less considered. Wary of an email being dismissed because it was sent on-the-go, I've removed the signature more often than I've kept it in. A colleague of mine observed that emails from smartphones don't seem to offer a full or credible response.

A familiarity with technology's flaws may be only part of what drives our forgiveness, however. The goodwill effect of the iPhone signature also stems from its position as a subtle marker of status and class, notes Nathan Jurgenson, a social media theorist and graduate student in sociology at the University of Maryland.

"'Sent from my iPhone,' especially in the early days of the iPhone when that signature became a cultural norm, also said, 'I'm successful, I'm of a certain class, I'm hip and modern and with it," wrote Jurgenson in an email.

Though no study has yet examined whether Android, BlackBerry and Windows Phone owners are afforded the same consideration as their iPhone-toting brethren, those distinctions could soon be meaningless: As technology improves, we may lose our roster of excuses and white lies, and be forced to be more genuine in our own communications. As the gadgets get better, we may get better.

Already, apps like Find My Friends or Google Latitude allow people to see exactly where their dinner date is when she claims she's "almost there. Google Now can alert users when traffic on their route to work means they should leave early to avoid arriving late for a meeting. If such tools continue to proliferate, old excuses like "I got lost" or "We got stuck in traffic" could become null and void.

But just in case:

--Sent from my iPhone

Published on June 28, 2013 08:37

June 27, 2013

Why Your Friends Go Around 'Liking' Brands On Facebook

To many, "liking" a brand on Facebook seems even more disagreeable than befriending a former coworker with a cat obsession. It means opting in for more advertising, cluttering up an already-cluttered News Feed and irritating all the friends who'll soon get pitches from whatever brand you've "liked." To sign up for all that, many assume there’d have to be some kind of cash reward.

Yet according to a new study from Syncapse, a social media marketing firm, people who “like” brands on Facebook do so because they actually like that brand -- not necessarily because they’re being bribed.

The survey polled 2,080 Facebook users who were fans of 20 major consumer brands, such as Nike, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, on why they’d decided to “like” a brand’s page. Forty-nine percent of respondents cited their desire to “support the brand I like,” making it the most popular reason among the 10 that Syncapse’s survey offered.

Though the survey’s "support" language is somewhat vague, the finding nonetheless underscores that some Facebook users are willing to befriend corporations and endorse their products on the companies’ behalf, without any financial incentive.

A large share of the survey respondents (41 percent) actually wanted to get updates from the brands they "liked," and just under a third (27 percent) had become fans the brand to "share my interests/lifestyle with others."

The motivation to show off one’s taste in fast food or apparel hints the “like” could be evolving into the online equivalent of the logo tee. The “like” helps publicize your brand affiliations to all the faraway Facebook friends who can’t see you donning your Adidas sandals while sipping from a Starbucks cup.

Perhaps the “like” is merely a precursor to more explicit brand endorsement by Facebook users. If a friend will “like” Victoria’s Secret’s Facebook page, why wouldn’t she be willing to put the lingerie-maker’s PINK logo all over her Facebook Timeline? After all, she may already be wearing it on her sweatpants, tank tops, swimsuit and sweatshirts. Nike T-shirts, with their enormous swoosh logo, could easily evolve into the Nike Timeline.

In a press release outlining the suvey’s findings, Syncapse advised its corporate clients that, "Overall, emotional and relationship motivators were more prominent reasons for becoming a fan of a brand, versus transactional offers and incentives.”

Yet money still speaks: a desire to get coupons or discounts was the second-most highly ranked motivator for "liking" a brand. Forty-two percent said they'd hoped to get special offers by becoming a brand’s Facebook fan and 35 percent had "liked" the brand in order to participate in a contest.

Syncapse’s research did not probe why people who haven't "liked" brands opted not to do so. Nor did it examine how people react to seeing updates from all the companies their brand-friendly acquaintances have subscribed to.

What’s good for the brands may not be good for Facebook. Just over a year ago, the social network started showing users ads from brand pages their friends have liked, and though Mark Zuckerberg has claimed users don't mind the ads, it remains to be seen whether people really will put up with the new noise.

Yet according to a new study from Syncapse, a social media marketing firm, people who “like” brands on Facebook do so because they actually like that brand -- not necessarily because they’re being bribed.

The survey polled 2,080 Facebook users who were fans of 20 major consumer brands, such as Nike, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, on why they’d decided to “like” a brand’s page. Forty-nine percent of respondents cited their desire to “support the brand I like,” making it the most popular reason among the 10 that Syncapse’s survey offered.

Though the survey’s "support" language is somewhat vague, the finding nonetheless underscores that some Facebook users are willing to befriend corporations and endorse their products on the companies’ behalf, without any financial incentive.

A large share of the survey respondents (41 percent) actually wanted to get updates from the brands they "liked," and just under a third (27 percent) had become fans the brand to "share my interests/lifestyle with others."

The motivation to show off one’s taste in fast food or apparel hints the “like” could be evolving into the online equivalent of the logo tee. The “like” helps publicize your brand affiliations to all the faraway Facebook friends who can’t see you donning your Adidas sandals while sipping from a Starbucks cup.

Perhaps the “like” is merely a precursor to more explicit brand endorsement by Facebook users. If a friend will “like” Victoria’s Secret’s Facebook page, why wouldn’t she be willing to put the lingerie-maker’s PINK logo all over her Facebook Timeline? After all, she may already be wearing it on her sweatpants, tank tops, swimsuit and sweatshirts. Nike T-shirts, with their enormous swoosh logo, could easily evolve into the Nike Timeline.

In a press release outlining the suvey’s findings, Syncapse advised its corporate clients that, "Overall, emotional and relationship motivators were more prominent reasons for becoming a fan of a brand, versus transactional offers and incentives.”

Yet money still speaks: a desire to get coupons or discounts was the second-most highly ranked motivator for "liking" a brand. Forty-two percent said they'd hoped to get special offers by becoming a brand’s Facebook fan and 35 percent had "liked" the brand in order to participate in a contest.

Syncapse’s research did not probe why people who haven't "liked" brands opted not to do so. Nor did it examine how people react to seeing updates from all the companies their brand-friendly acquaintances have subscribed to.

What’s good for the brands may not be good for Facebook. Just over a year ago, the social network started showing users ads from brand pages their friends have liked, and though Mark Zuckerberg has claimed users don't mind the ads, it remains to be seen whether people really will put up with the new noise.

Published on June 27, 2013 11:16

June 25, 2013

Wealthier College Students Share, Connect More On Facebook: Study

Social media may have to reconsider its reputation as the great equalizer: according to a new study, college students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely than their wealthier peers to communicate and share on Facebook, behavior the study's author argues could in turn be detrimental to academic performance and social life.

Purdue University Libraries Associate Professor Reynol Junco surveyed 2,359 college students with an average age of 22 years old to understand how gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status affected their time spent on and usage of the social networking site. The survey participants were asked to estimate how much time they spent on Facebook and what they did during that time. (However, a previous study by Junco showed self-reporting to be an inaccurate representation of the time students actually spent browsing the site.)

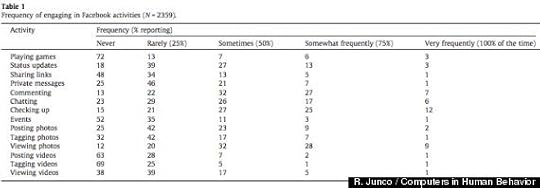

The table above lists the frequency with which all the students surveyed said they engaged in different activities on Facebook.

Junco found that students used the site with equal frequency, irrespective of their backgrounds, spending an average of 101 minutes a day on Facebook.

But those whose parents completed a lower level of education -- a proxy for socioeconomic status -- were less inclined to engage in seven of 14 of core social activities on Facebook, including tagging photos, messaging privately, chatting on the site and creating or RSVPing to events, according to the study.

While the study did not determine if there were any activities that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to engage in, what those students are less likely to do on the site is notable, Junco wrote.

“[I]t can be concluded that those from lower SES [socio-economic status] are less likely to use Facebook for exactly the types of activities for which Facebook was created -- communicating, connecting, and sharing with others,” writes Junco. “Failure to connect in these ways could deprive students of the benefits of participation on such sites, such as increased social capital, improved social integration, opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, and improving the technological and communication skills valued in today’s workplace."

While acknowledging that some studies have found increased Facebook usage can harm academic performance, Junco maintains that the socializing Facebook fosters can lead to stronger relationships among students -- ultimately improving their on-campus experience. He explained that the seven Facebook activities that are less popular among students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are all important facilitators of inter-peer communication, and that abstaining from those activities means those students risk not forming as close bonds with others on their campus as they otherwise would.

"Take for example, those students who are from lower SES and how they use Facebook -- they are less likely to use it for communication and connection. Since Facebook is one of the primary communication sources for most college students, these students are at a disadvantage when attempting to build a social support system to help them integrate in their college environment," writes Junco.

Junco further argues that Facebook use can help college students develop more robust ties to the academic community, which could spur them to apply themselves to their studies and lower their chances of dropping out. The researcher found in a previous study that students who used Facebook to check in on friends and share links boasted higher GPAs.

"Using Facebook for communication and connection with fellow students helps strengthen social bonds, which leads to a greater sense of commitment to the institution and to increased motivation to perform better academically," Junco argues in the new study.

"One of the things we know from the retention literature is that students have to feel a sense of connection to the institution within their first three to six weeks, and if they don't feel a sense of connection to the institution ... then they're at risk of not coming back," Junco added in a phone interview with The Huffington Post. "The activities they engage in on Facebook -- information seeking, sharing videos, sharing pictures, tagging things -- are a way they also interact with other people."

Other studies examining the link between college students' Facebook use, academic success and social well-being have reached mixed conclusions on how much benefit social media confers to undergraduates. A study published earlier this year, for example, found that Facebook users experienced a boost of self esteem after looking at their own profiles for five minutes, but then performed more poorly when asked to complete a brief math test than groups who hadn't examined their Facebook accounts. The study's author, the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Catalina Toma, found the "self-esteem boost that came from looking at their profiles ultimately diminished participants' performance in the follow-up task by decreasing their motivation to perform well," according to a summary of the findings.

A 2011 paper examining how Facebook use affected college students' sense of well-being found variations between younger and older students. "The number of Facebook friends was negatively associated with emotional and academic adjustment among first-year students but positively related to social adjustment and attachment to institution among upper-class students," the researchers, who worked in Assumption College's Psychology Department, wrote in their abstract. "The results suggest that the relationship becomes positive later in college life when students use Facebook effectively to connect socially with their peers."

The Pew Research Center has also found that higher-income adults are more likely to use social networking sites: A December 2012 study found that 48 percent of adults in households earning under $30,000 per year used social media, while 65 percent earning over $75,000 did so.

Gender, more than race or class, ultimately accounted for the greatest difference in students’ activity on Facebook, Junco found in his study. Female students surveyed were more likely than their male counterparts to comment on Facebook; post status updates; and share, tag and browse photos -- a finding that concurs with other research into social media habits.

Purdue University Libraries Associate Professor Reynol Junco surveyed 2,359 college students with an average age of 22 years old to understand how gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status affected their time spent on and usage of the social networking site. The survey participants were asked to estimate how much time they spent on Facebook and what they did during that time. (However, a previous study by Junco showed self-reporting to be an inaccurate representation of the time students actually spent browsing the site.)

The table above lists the frequency with which all the students surveyed said they engaged in different activities on Facebook.

Junco found that students used the site with equal frequency, irrespective of their backgrounds, spending an average of 101 minutes a day on Facebook.

But those whose parents completed a lower level of education -- a proxy for socioeconomic status -- were less inclined to engage in seven of 14 of core social activities on Facebook, including tagging photos, messaging privately, chatting on the site and creating or RSVPing to events, according to the study.

While the study did not determine if there were any activities that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to engage in, what those students are less likely to do on the site is notable, Junco wrote.

“[I]t can be concluded that those from lower SES [socio-economic status] are less likely to use Facebook for exactly the types of activities for which Facebook was created -- communicating, connecting, and sharing with others,” writes Junco. “Failure to connect in these ways could deprive students of the benefits of participation on such sites, such as increased social capital, improved social integration, opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, and improving the technological and communication skills valued in today’s workplace."

While acknowledging that some studies have found increased Facebook usage can harm academic performance, Junco maintains that the socializing Facebook fosters can lead to stronger relationships among students -- ultimately improving their on-campus experience. He explained that the seven Facebook activities that are less popular among students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are all important facilitators of inter-peer communication, and that abstaining from those activities means those students risk not forming as close bonds with others on their campus as they otherwise would.

"Take for example, those students who are from lower SES and how they use Facebook -- they are less likely to use it for communication and connection. Since Facebook is one of the primary communication sources for most college students, these students are at a disadvantage when attempting to build a social support system to help them integrate in their college environment," writes Junco.

Junco further argues that Facebook use can help college students develop more robust ties to the academic community, which could spur them to apply themselves to their studies and lower their chances of dropping out. The researcher found in a previous study that students who used Facebook to check in on friends and share links boasted higher GPAs.

"Using Facebook for communication and connection with fellow students helps strengthen social bonds, which leads to a greater sense of commitment to the institution and to increased motivation to perform better academically," Junco argues in the new study.

"One of the things we know from the retention literature is that students have to feel a sense of connection to the institution within their first three to six weeks, and if they don't feel a sense of connection to the institution ... then they're at risk of not coming back," Junco added in a phone interview with The Huffington Post. "The activities they engage in on Facebook -- information seeking, sharing videos, sharing pictures, tagging things -- are a way they also interact with other people."

Other studies examining the link between college students' Facebook use, academic success and social well-being have reached mixed conclusions on how much benefit social media confers to undergraduates. A study published earlier this year, for example, found that Facebook users experienced a boost of self esteem after looking at their own profiles for five minutes, but then performed more poorly when asked to complete a brief math test than groups who hadn't examined their Facebook accounts. The study's author, the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Catalina Toma, found the "self-esteem boost that came from looking at their profiles ultimately diminished participants' performance in the follow-up task by decreasing their motivation to perform well," according to a summary of the findings.

A 2011 paper examining how Facebook use affected college students' sense of well-being found variations between younger and older students. "The number of Facebook friends was negatively associated with emotional and academic adjustment among first-year students but positively related to social adjustment and attachment to institution among upper-class students," the researchers, who worked in Assumption College's Psychology Department, wrote in their abstract. "The results suggest that the relationship becomes positive later in college life when students use Facebook effectively to connect socially with their peers."

The Pew Research Center has also found that higher-income adults are more likely to use social networking sites: A December 2012 study found that 48 percent of adults in households earning under $30,000 per year used social media, while 65 percent earning over $75,000 did so.

Gender, more than race or class, ultimately accounted for the greatest difference in students’ activity on Facebook, Junco found in his study. Female students surveyed were more likely than their male counterparts to comment on Facebook; post status updates; and share, tag and browse photos -- a finding that concurs with other research into social media habits.

Published on June 25, 2013 14:08

How Facebook Explains User Data Bug That Leaked 6 Million People's Information

When Facebook admitted Friday that a year-old glitch had erroneously exposed 6 million users’ contact information, the social network known for helping things go viral seemed to do its best to keep the news from spreading.

Though Facebook did take pains to email all 6 million people affected, the social network posted its announcement about the data leak just before 5 p.m. ET on a Friday afternoon -- on a Facebook page belonging to the company’s security team, rather than its main account, and with a deceptively boring title, ”Important Message from Facebook’s White Hat Program.”

Facebook noted that describing the cause of the bug "can get pretty technical," and proceeded with an explanation that seemed to befuddle tech writers, aficionados and users.

"Received this Note from Facebook via my private email. Concerned & don't understand !!! How do we know... who, what, when, where & how this happened? [sic]" asked one Facebook user. "That being said... How do we know it's been fixed? Will somebody help me to better understand!"

Yes, someone will. Here’s some context and analysis on what Facebook meant by its announcement -- and an exegesis of how a major tech company issues a non-apology mea culpa in the age of recurring privacy leaks.

Though Facebook did take pains to email all 6 million people affected, the social network posted its announcement about the data leak just before 5 p.m. ET on a Friday afternoon -- on a Facebook page belonging to the company’s security team, rather than its main account, and with a deceptively boring title, ”Important Message from Facebook’s White Hat Program.”

Facebook noted that describing the cause of the bug "can get pretty technical," and proceeded with an explanation that seemed to befuddle tech writers, aficionados and users.

"Received this Note from Facebook via my private email. Concerned & don't understand !!! How do we know... who, what, when, where & how this happened? [sic]" asked one Facebook user. "That being said... How do we know it's been fixed? Will somebody help me to better understand!"

Yes, someone will. Here’s some context and analysis on what Facebook meant by its announcement -- and an exegesis of how a major tech company issues a non-apology mea culpa in the age of recurring privacy leaks.

Published on June 25, 2013 06:31

June 20, 2013

Instagram Video Takes Selfies To New Extremes

In a blog post published Thursday, Instagram introduced the app's new video-sharing feature by showcasing four short cinematic clips people had shared with its service. There was a video of Kobe Bryant walking through a doctor's office on crutches; another of babies gurgling on a blanket; a whimsical one of an amusement park ride above the mountains of Hong Kong; and a video of a latte being made in a Santa Cruz café.

Once the new service went live to Instagram users, however, the videos rushing in were of a decidedly different sort: Every few seconds brought a new clip of people speaking into their smartphones, extended at arm's length, with expressions of disbelief, horror, surprise, confusion and excitement. There were stop-action videos of people smiling and sticking their tongues out. One girl filmed herself lip-syncing to Miley Cyrus.

"This is awkward!" another teen squealed.

It marked a major moment not only for Instagram -- which had just announced that users could, for the first time ever, post videos up to 15 seconds long -- but also for the "selfie." The static cellphone self-portrait, the breed of photo the Internet most loves to hate, had officially been recast in an animated form. In the process, the selfie returned to its roots: messy, vaguely uncomfortable and strangely honest.

As one Instagrammer observed, staring into her phone's camera, "This whole video thing is pretty weird. I don't even know what to do. [...] But I guess it's cool."

Photographic selfies, which have been around at least as long as it's been possible to take pictures with cell phones, have been staging a comeback, as Kate Losse observed in the New Yorker earlier this month.

While the first selfies were a blurry, unattractive bunch that caught people in bathroom mirrors or under harsh fluorescent bulbs, the high-resolution cameras on smartphones and the rise of filters, like those available on Instagram, have effectively sanitized the medium. In photo form, the selfie has become faux-unflattering, a carefully-staged candid of oneself that, as Losse writes, "can look as polished and crisp as posed group shots." Celebrities, and even CEOs, are now sharing selfies.

But social media apps like Instagram and Vine -- Twitter's six-second video-sharing app that Facebook effectively cloned with the new Instagram product -- are revamping the selfie with video, turning it from a document into a kind of diary entry. There's a confessional quality and an honesty to the filmed selfies proliferating wildly on Vine and Instagram. After all, even in the reality TV and viral video age, most of us are still used to seeing people in videos that have been edited, where outfits and makeup have been carefully staged.

In their new video form, selfies could actually counter much of the criticism of social media. Even with Instagram's filters and Vine's simple photo-editing tools, video is still harder to fake, pose and perfect; it captures not just an instant, but a period in time.

We see a person getting distracted by a sound off-camera, or people shuffling around in the background of the frame. We hear noises that don't belong, noises that throw off the whole scene. (In one Insta-selfie, a girl films herself reacting to Instagram's new video tool -- and is interrupted by someone asking for pants in another size. She's in the changing room of a store, we realize, something that wouldn't have been apparent in an image.)

We are also likely to see what's initially beyond the camera's frame. A coworker's Cancun cruise might seem blissful according to the album she uploaded on Facebook, from which all unflattering photos have been excised. Filmed on Instagram or Vine, however, we might catch sight of the interminable line at the breakfast buffet, or the sea of people crowding her chair by the pool. All the imperfections become harder to hide.

But that doesn't mean Instagram has given up on helping people cover them up.

Kevin Systrom, Instagram's co-founder, explained during a press conference Thursday that people would be able to add the app's trademark filters to their videos, and could also delete parts of a video and film it over again. Instagram will also offer "Cinema," a video-stabilizing feature that will lend shaky home videos a more professional air, and let users pick a frame to serve as a cover image for each video, guaranteeing they can avoid an awkward, mouth-agape-eyes-closed still. Those are four features Vine still doesn't offer.

"It wouldn't be Instagram without allowing you to produce beautiful content," Systrom said. "We need to do to video what we did to photos."

The beauty isn't just for our benefit, however.

It turns out that the same instincts of self-preservation and self-centeredness that make us want to look beautiful in front of our online audience actually serve social media sites' interests, too.

Facebook's advertisers -- who will no doubt come to Instagram shortly -- also want us to look our best. They want their brands next to people who are happy, who "like" things, who don't crack jokes about rape and who aren't showing too much skin. The video selfies flowing through Instagram might seem honest now, but it's easy to imagine they'll soon evolve beyond personal confessionals and into personal advertisements.

After all, it's no coincidence that Instagram's new 15-second-long clips will be just as long as another well-known form of video: TV commercials. The more beautifully we advertise ourselves, the more effectively we can be advertised to.

Once the new service went live to Instagram users, however, the videos rushing in were of a decidedly different sort: Every few seconds brought a new clip of people speaking into their smartphones, extended at arm's length, with expressions of disbelief, horror, surprise, confusion and excitement. There were stop-action videos of people smiling and sticking their tongues out. One girl filmed herself lip-syncing to Miley Cyrus.

"This is awkward!" another teen squealed.

It marked a major moment not only for Instagram -- which had just announced that users could, for the first time ever, post videos up to 15 seconds long -- but also for the "selfie." The static cellphone self-portrait, the breed of photo the Internet most loves to hate, had officially been recast in an animated form. In the process, the selfie returned to its roots: messy, vaguely uncomfortable and strangely honest.

As one Instagrammer observed, staring into her phone's camera, "This whole video thing is pretty weird. I don't even know what to do. [...] But I guess it's cool."

Photographic selfies, which have been around at least as long as it's been possible to take pictures with cell phones, have been staging a comeback, as Kate Losse observed in the New Yorker earlier this month.

While the first selfies were a blurry, unattractive bunch that caught people in bathroom mirrors or under harsh fluorescent bulbs, the high-resolution cameras on smartphones and the rise of filters, like those available on Instagram, have effectively sanitized the medium. In photo form, the selfie has become faux-unflattering, a carefully-staged candid of oneself that, as Losse writes, "can look as polished and crisp as posed group shots." Celebrities, and even CEOs, are now sharing selfies.

But social media apps like Instagram and Vine -- Twitter's six-second video-sharing app that Facebook effectively cloned with the new Instagram product -- are revamping the selfie with video, turning it from a document into a kind of diary entry. There's a confessional quality and an honesty to the filmed selfies proliferating wildly on Vine and Instagram. After all, even in the reality TV and viral video age, most of us are still used to seeing people in videos that have been edited, where outfits and makeup have been carefully staged.

In their new video form, selfies could actually counter much of the criticism of social media. Even with Instagram's filters and Vine's simple photo-editing tools, video is still harder to fake, pose and perfect; it captures not just an instant, but a period in time.

We see a person getting distracted by a sound off-camera, or people shuffling around in the background of the frame. We hear noises that don't belong, noises that throw off the whole scene. (In one Insta-selfie, a girl films herself reacting to Instagram's new video tool -- and is interrupted by someone asking for pants in another size. She's in the changing room of a store, we realize, something that wouldn't have been apparent in an image.)

We are also likely to see what's initially beyond the camera's frame. A coworker's Cancun cruise might seem blissful according to the album she uploaded on Facebook, from which all unflattering photos have been excised. Filmed on Instagram or Vine, however, we might catch sight of the interminable line at the breakfast buffet, or the sea of people crowding her chair by the pool. All the imperfections become harder to hide.

But that doesn't mean Instagram has given up on helping people cover them up.

Kevin Systrom, Instagram's co-founder, explained during a press conference Thursday that people would be able to add the app's trademark filters to their videos, and could also delete parts of a video and film it over again. Instagram will also offer "Cinema," a video-stabilizing feature that will lend shaky home videos a more professional air, and let users pick a frame to serve as a cover image for each video, guaranteeing they can avoid an awkward, mouth-agape-eyes-closed still. Those are four features Vine still doesn't offer.

"It wouldn't be Instagram without allowing you to produce beautiful content," Systrom said. "We need to do to video what we did to photos."

The beauty isn't just for our benefit, however.

It turns out that the same instincts of self-preservation and self-centeredness that make us want to look beautiful in front of our online audience actually serve social media sites' interests, too.

Facebook's advertisers -- who will no doubt come to Instagram shortly -- also want us to look our best. They want their brands next to people who are happy, who "like" things, who don't crack jokes about rape and who aren't showing too much skin. The video selfies flowing through Instagram might seem honest now, but it's easy to imagine they'll soon evolve beyond personal confessionals and into personal advertisements.

After all, it's no coincidence that Instagram's new 15-second-long clips will be just as long as another well-known form of video: TV commercials. The more beautifully we advertise ourselves, the more effectively we can be advertised to.

Published on June 20, 2013 14:28

June 19, 2013

Privacy Officials From 7 Nations Question Google On Glass' 'Ubiquitous Surveillance'

Privacy officials from seven nations sent a letter Wednesday to Google chief executive Larry Page, pressing him to explain the privacy implications of Glass, Google's forthcoming wearable computing device.

The letter, co-signed by 10 privacy and data commissioners from Mexico, Israel, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland and a Dutch representative from the European Commission, outlined eight questions concerning Glass' privacy safeguards. They ranged from what information Glass collects and how Google uses that data, to how Glass might incorporate facial recognition in the future.

"Fears of ubiquitous surveillance of individuals by other individuals, whether through such recordings or through other applications currently being developed, have been raised," the officials wrote. "We understand that other companies are developing similar products, but you are a leader in this area, the first to test your product 'in the wild' so to speak, and the first to confront the ethical issues that such a product entails."

Glass, which is worn on a user's face, is equipped with a camera, touchpad and small screen suspended over the wearer's right eye to display messages and alerts. Glass connects to the user's smartphone via Bluetooth and, like a smartphone, can be used for messaging, taking pictures, calling up driving directions, placing calls and searching the web. Developers from Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr and CNN, among other firms, have begun releasing apps for Glass, though Google recently updated its policies to bar facial recognition and pornography apps.

The privacy authorities who co-signed the letter to Page noted that, though they'd encouraged companies to "consult in a meaningful way with our respective offices," most of them had "not been approached by your company [Google] to discuss any of these issues in detail." They also asked Google if it would be willing to demonstrate Glass for them, and allow officials to test the device themselves.

Glass has so far been released in a limited trial in the U.S., and Google has given no specific date by which it will be available to the public, or in other countries.

"It’s very early days and we are thinking very carefully about how we design Glass because new technology always raises new issues," a Google spokesman told The Huffington Post in an emailed statement. "Our Glass Explorer program, which reaches people from all walks of life, will ensure that our users become active participants in shaping the future of this technology -- and we're excited to hear the feedback."

The June 19 letter follows another sent to Google in May by members of Congress, who also asked Google to address privacy concerns raised by Glass. Google was asked to reply to their questions by June 14, but the eight representatives who queried the company have not yet released Google's reply.

Google employees have previously noted that Glass wearers' "social contract" with other people around them should help allay some privacy concerns and keep bad behavior in check.

"If I'm recording you, I have to stare at you -- as a human being. And when someone is staring at you, you have to notice," Google engineer Charles Mendis said during a panel discussion last month, according to The Verge. "If you walk into a restroom and someone's just looking at you -- I don't know about you but I'm getting the hell out of there."

The letter, co-signed by 10 privacy and data commissioners from Mexico, Israel, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland and a Dutch representative from the European Commission, outlined eight questions concerning Glass' privacy safeguards. They ranged from what information Glass collects and how Google uses that data, to how Glass might incorporate facial recognition in the future.

"Fears of ubiquitous surveillance of individuals by other individuals, whether through such recordings or through other applications currently being developed, have been raised," the officials wrote. "We understand that other companies are developing similar products, but you are a leader in this area, the first to test your product 'in the wild' so to speak, and the first to confront the ethical issues that such a product entails."

Glass, which is worn on a user's face, is equipped with a camera, touchpad and small screen suspended over the wearer's right eye to display messages and alerts. Glass connects to the user's smartphone via Bluetooth and, like a smartphone, can be used for messaging, taking pictures, calling up driving directions, placing calls and searching the web. Developers from Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr and CNN, among other firms, have begun releasing apps for Glass, though Google recently updated its policies to bar facial recognition and pornography apps.

The privacy authorities who co-signed the letter to Page noted that, though they'd encouraged companies to "consult in a meaningful way with our respective offices," most of them had "not been approached by your company [Google] to discuss any of these issues in detail." They also asked Google if it would be willing to demonstrate Glass for them, and allow officials to test the device themselves.

Glass has so far been released in a limited trial in the U.S., and Google has given no specific date by which it will be available to the public, or in other countries.

"It’s very early days and we are thinking very carefully about how we design Glass because new technology always raises new issues," a Google spokesman told The Huffington Post in an emailed statement. "Our Glass Explorer program, which reaches people from all walks of life, will ensure that our users become active participants in shaping the future of this technology -- and we're excited to hear the feedback."

The June 19 letter follows another sent to Google in May by members of Congress, who also asked Google to address privacy concerns raised by Glass. Google was asked to reply to their questions by June 14, but the eight representatives who queried the company have not yet released Google's reply.

Google employees have previously noted that Glass wearers' "social contract" with other people around them should help allay some privacy concerns and keep bad behavior in check.

"If I'm recording you, I have to stare at you -- as a human being. And when someone is staring at you, you have to notice," Google engineer Charles Mendis said during a panel discussion last month, according to The Verge. "If you walk into a restroom and someone's just looking at you -- I don't know about you but I'm getting the hell out of there."

Published on June 19, 2013 15:14

Siri Is Taking A New Approach To Suicide

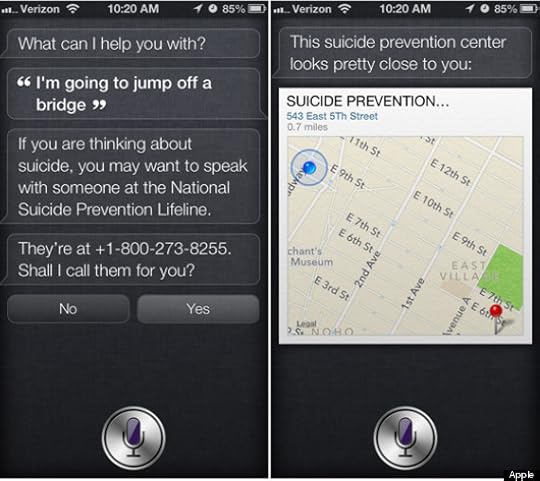

A new update to Apple's Siri is helping the virtual assistant better handle questions about suicide and more quickly assist people who are seeking help.

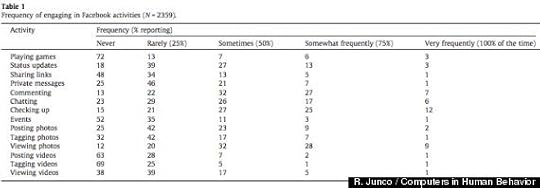

If Siri receives a query that suggests a user may be considering suicide, it will now prompt the individual to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and offer to phone the hotline directly. If the prompt is dismissed, Siri will follow up by displaying a list of suicide prevention centers closest to the user's location.

The update underscores the increasingly intimate nature of what people tell their phones and how smartphones could be expected to help in a broader array of situations in the future. Siri's new offering is activated by statements such as "I'm going to jump off a bridge," "I think I want to kill myself" and "I want to shoot myself" -- all unusually intimate confessions to be spoken to software.

The update also also raises the prospect that virtual assistants could soon counsel us on an ever-widening range of personal and profound life events. Given its current ability to assist people who appear to be debating self-harm, could Siri soon try to intervene when people ask about buying guns or killing other people? What about domestic abuse or sexual assault?

When it was first released, Siri had trouble grappling with some suicidal queries and sometimes offered answers that seemed bizarrely callous. Asked, "Should I jump off a bridge?" a 2011 version of Siri would answer with a list of nearby bridges. After a frustrating exchange with Siri about addressing a mental health emergency, feeling suicidal and finding suicide hotlines, PsychCentral's Summer Beretsky concluded that when it comes to getting support for people feeling suicidal, "you might as well consult a freshly-mined chunk of elemental silicon instead." Beretsky found it took her 21 minutes to get Siri to locate the number for a suicide hotline.

Prior to the most recent update, queries from users considering self-harm were answered with a map of nearby suicide prevention centers.

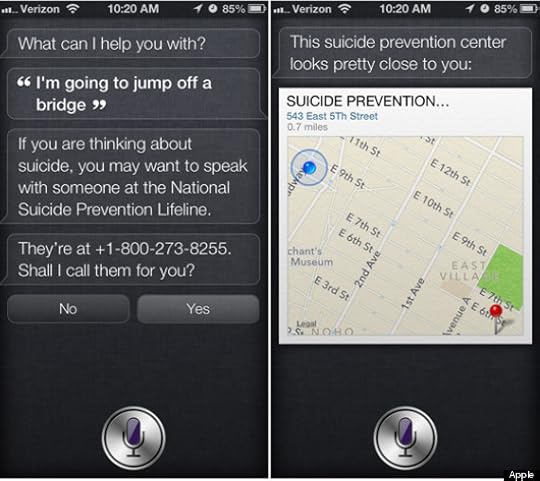

Even after the upgrade, Siri still misses a few cues. Tell the assistant, "I'm thinking about hurting myself," and it will offer to search the web.

Informing Siri, "I don't want to live anymore" prompts an even more insensitive answer: "OK, then."

If Siri receives a query that suggests a user may be considering suicide, it will now prompt the individual to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and offer to phone the hotline directly. If the prompt is dismissed, Siri will follow up by displaying a list of suicide prevention centers closest to the user's location.

The update underscores the increasingly intimate nature of what people tell their phones and how smartphones could be expected to help in a broader array of situations in the future. Siri's new offering is activated by statements such as "I'm going to jump off a bridge," "I think I want to kill myself" and "I want to shoot myself" -- all unusually intimate confessions to be spoken to software.

The update also also raises the prospect that virtual assistants could soon counsel us on an ever-widening range of personal and profound life events. Given its current ability to assist people who appear to be debating self-harm, could Siri soon try to intervene when people ask about buying guns or killing other people? What about domestic abuse or sexual assault?

When it was first released, Siri had trouble grappling with some suicidal queries and sometimes offered answers that seemed bizarrely callous. Asked, "Should I jump off a bridge?" a 2011 version of Siri would answer with a list of nearby bridges. After a frustrating exchange with Siri about addressing a mental health emergency, feeling suicidal and finding suicide hotlines, PsychCentral's Summer Beretsky concluded that when it comes to getting support for people feeling suicidal, "you might as well consult a freshly-mined chunk of elemental silicon instead." Beretsky found it took her 21 minutes to get Siri to locate the number for a suicide hotline.

Prior to the most recent update, queries from users considering self-harm were answered with a map of nearby suicide prevention centers.

Even after the upgrade, Siri still misses a few cues. Tell the assistant, "I'm thinking about hurting myself," and it will offer to search the web.

Informing Siri, "I don't want to live anymore" prompts an even more insensitive answer: "OK, then."

Published on June 19, 2013 08:39

June 18, 2013

'Hell Is Other People' Helps You Steer Clear Of Your Awful 'Friends'

Finally, there's a social media app for people who hate social media -- and other people: "Hell Is Other People," an "experiment in anti-social media," uses Foursquare check-ins to help people avoid their so-called friends.

The app pulls Foursquare data to calculate "safe zones" around a city, or "optimally distanced locations" where people can feel certain they'll avoid anyone they know. Rather than holing up at home -- a surefire way to avoid bumping into people -- individuals with social anxiety, frenemies or just plain annoying acquaintances can now navigate their city without fear of seeing friends.

"Hell Is Other People," inspired by a line from Jean-Paul Sartre's "No Exit," is the brainchild of Scott Garner, a Master's candidate at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. On his website, Garner describes the app as "partially a satire, partially a commentary on my disdain for 'social media,' and partially an exploration of my own difficulties with social anxiety." (He also notes it was a final for a course at ITP).

"I actually really hate social media," explains Garner in a short video he made of himself navigating New York with his app. "I had to sign up for a social media site and talk to people to get them to be my friends on that site so I could avoid them."

After allowing Hell Is Other People to access their Foursquare account, users will see a map of their location that shows the 20 most recent check-ins by their Foursquare acquaintances, with "safe zones" delineated in green. Users can click on the orange dots, which indicate a recent check-in, to see who checked in, where and when.

While Foursquare, the brainchild of another ITP graduate, seeks to help people discover new venues by getting recommendations from their friends, Garner's anti-Foursquare does much the same thing by steering them away from places populated by people they know. Hell Is Other People users can discover unexplored locales in the process of avoiding acquaintances, and counteract what Garner sees as the "homogenizing" effect of social recommendation services.

"You end up in places that have no meaning, but are far from your friends," Garner said during a phone interview with The Huffington Post. "If you think about how Foursquare works, it says, 'your friends like this, so you might like this too.' It has this homogenizing effect. You could see this [Hell Is Other People] as, 'No one you like goes to this place, so maybe you should try it to break out of this social sphere you're operating in.'"

As Garner notes, copiously working to avoid people can actually make a person maddeningly reliant on the very individuals he's trying to steer clear of: The app only works if a user's Foursquare friends are actively checking into the app. Otherwise, the playpen-like "safe zones" risk being out of date or inaccurate.

"Most frustrating of all is that people are not checking in today," Garner laments during his video. "I hate doing things that depend on other people because they are so unpredictable and unreliable."

Garner notes that he's considered incorporating other data, like Facebook check-ins or geo-tagged tweets, to give his app for a fuller picture of unsafe, social zones, though has no immediate plans to do so. Just shy of 600 people have installed his app, and he notes its popularity has actually forced him to socialize.

"In a weird way, it was a conversation starter that made me interact with more people in all regards," he said. "In that way, it kind of backfired, but that's okay."

(h/t Geekosystem, Betabeat)

The app pulls Foursquare data to calculate "safe zones" around a city, or "optimally distanced locations" where people can feel certain they'll avoid anyone they know. Rather than holing up at home -- a surefire way to avoid bumping into people -- individuals with social anxiety, frenemies or just plain annoying acquaintances can now navigate their city without fear of seeing friends.

"Hell Is Other People," inspired by a line from Jean-Paul Sartre's "No Exit," is the brainchild of Scott Garner, a Master's candidate at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. On his website, Garner describes the app as "partially a satire, partially a commentary on my disdain for 'social media,' and partially an exploration of my own difficulties with social anxiety." (He also notes it was a final for a course at ITP).

"I actually really hate social media," explains Garner in a short video he made of himself navigating New York with his app. "I had to sign up for a social media site and talk to people to get them to be my friends on that site so I could avoid them."

After allowing Hell Is Other People to access their Foursquare account, users will see a map of their location that shows the 20 most recent check-ins by their Foursquare acquaintances, with "safe zones" delineated in green. Users can click on the orange dots, which indicate a recent check-in, to see who checked in, where and when.

While Foursquare, the brainchild of another ITP graduate, seeks to help people discover new venues by getting recommendations from their friends, Garner's anti-Foursquare does much the same thing by steering them away from places populated by people they know. Hell Is Other People users can discover unexplored locales in the process of avoiding acquaintances, and counteract what Garner sees as the "homogenizing" effect of social recommendation services.

"You end up in places that have no meaning, but are far from your friends," Garner said during a phone interview with The Huffington Post. "If you think about how Foursquare works, it says, 'your friends like this, so you might like this too.' It has this homogenizing effect. You could see this [Hell Is Other People] as, 'No one you like goes to this place, so maybe you should try it to break out of this social sphere you're operating in.'"

As Garner notes, copiously working to avoid people can actually make a person maddeningly reliant on the very individuals he's trying to steer clear of: The app only works if a user's Foursquare friends are actively checking into the app. Otherwise, the playpen-like "safe zones" risk being out of date or inaccurate.

"Most frustrating of all is that people are not checking in today," Garner laments during his video. "I hate doing things that depend on other people because they are so unpredictable and unreliable."

Garner notes that he's considered incorporating other data, like Facebook check-ins or geo-tagged tweets, to give his app for a fuller picture of unsafe, social zones, though has no immediate plans to do so. Just shy of 600 people have installed his app, and he notes its popularity has actually forced him to socialize.

"In a weird way, it was a conversation starter that made me interact with more people in all regards," he said. "In that way, it kind of backfired, but that's okay."

(h/t Geekosystem, Betabeat)

Published on June 18, 2013 08:31

June 17, 2013

Dmitry Itskov Knows He'll Live Forever; Here's How He's Living Now

NEW YORK -- No sooner has Dmitry Itskov, a 32-year-old Russian multimillionaire, sat down at the table in his hotel room than he springs up again and begins pawing through the snacks in the minibar. He tosses aside chips and candy, settles on a box of mixed nuts, then sits back down.

Itskov maintains a strict diet -- no meat, fish, coffee, alcohol or cold water -- but not because he's afraid of high blood pressure or heart disease. In fact, he's convinced we’ll all live forever.

Itskov's 2045 Initiative has the goal of achieving human immortality within the next three decades. It aspires to change human evolution as we know it and Itskov has drawn up an ambitious timeline for this transition to “neo-humanity”: By 2045, his manifesto maintains, we’ll have “substance-independent minds” housed in non-biological bodies.

In 2011, he stepped back from his work as an internet entrepreneur to lead the project, which he runs from his home in Moscow. He has traveled to New York this week to host a conference at which luminaries such as Marvin Minsky and Ray Kurzweil will discuss this new evolutionary approach.

Though his endeavor immediately conjures up visions of robotic humanoids and artificial organs, Itskov is most concerned with how immortality will reshape the mind.

“Immortality is a side effect,” he explains, describing eternal life as a means of transforming and improving human consciousness. Decoupling the mind from the needy human body, which demands food, medicine and shelter, can curb our negative inclinations and pave the way for a more elevated and sublime human spirit, he believes.

“Sometimes the way people live makes me think that they’re just following programs,” he says. “We should try to look for the opportunity to develop spiritually.”

Itskov is preparing for eternal life by training himself to attain a higher state of consciousness, and he gives the impression of someone who considers his body only insofar as it hinders or helps his mental pursuits. He spends several hours a day meditating, doing yoga or engaged in breathing exercises, all part of a spiritual practice he says helps him “discover some different states of my consciousness.”

His diet is guided by how different foods affect his energy. Meat gives him an energy he’s “not comfortable with,” he says. Alcohol “affects the consciousness” so "you stop feeling the real nature of it.” Even ice water is off limits because it lowers energy, Itskov tells a documentary filmmaker who’s offered him a cup of ice water while her crew sets up in his hotel room.

Itskov, who has close-shaven blonde hair and a vague shadow of stubble, speaks softly, slowly and with the calm self-assurance of someone who’s used to considering much more cosmic questions than those being posed to him.

How certain is he that humans will attain immortality by 2045?

“I am 100 percent certain,” he answers.

And what gives him that certainty?

“My belief," he says. He pauses for a moment, then continues: "In an ancient text, I read that whatever we have in our mind, in our consciousness, whatever we intend to achieve, we will achieve. It depends when, and it depends on the internal certainty."

Questions are frequently answered with a question -- is he religious? “What is religion?” -- and even the nature of death is up for debate. Doctors can measure the death of the physical body, says Itskov, but no one has determined how to evaluate the death of consciousness.

Itskov has already considered a world in which biology is obsolete, and bodies are supplanted by holograms or avatars.("If the technology advances, I think there will be no need for biology at all," he says.)

Within a century, he tells the filmmaker, we’ll frequent “body service shops” where we can choose our bodies from a catalog, then transfer our consciousness to one better-suited for, say, life on Mars. He seems to find the world’s relentless focus on carnal matters to be quite tedious, and laments to the documentary crew that every interviewer asks him how his vision will affect eating, procreating and having sex.

“Why don’t people think about something more sophisticated than just food, sex and children?” he asks. “By the way, if you live in this biological body for 80 years and have five or six children, isn’t that enough? Why don’t you start living for a greater purpose than to just help raise your children?”

Itskov’s quest for a deeper consciousness hasn’t stopped him from indulging in a few earthly pleasures: When we sit down for an interview, he has on a Burberry button-down and Louis Vuitton sneakers.

So what does someone do for fun if he knows he’ll live forever? Itskov is content to dedicate his life to the pursuit of eternal life. He has no wife, children or immediate plans to have either, and spends just one week a month at his home in Moscow. The rest of the time he’s traveling between the U.S., Europe, India and China meeting with experts and potential supporters.

“We are mostly having fast fun in this world," says Itskov, likening fast fun to fast food. "But we are not thinking of a more essential fun, which is inside of us.”

Itskov says he has fond memories of visiting the Salvador Dali Theater and Museum in Figueres, and he loves the Prado Museum in Madrid. He's partial to paintings by El Greco and Goya. But once his mission has been realized, three decades from now, Itskov says he will seek out solitude, not sightseeing

“What will be intriguing to me is the process of development of my personal consciousness,” he tells the crew of filmmakers. “Probably, I’ll be sitting somewhere up in the mountains, just meditating.”

Itskov maintains a strict diet -- no meat, fish, coffee, alcohol or cold water -- but not because he's afraid of high blood pressure or heart disease. In fact, he's convinced we’ll all live forever.

Itskov's 2045 Initiative has the goal of achieving human immortality within the next three decades. It aspires to change human evolution as we know it and Itskov has drawn up an ambitious timeline for this transition to “neo-humanity”: By 2045, his manifesto maintains, we’ll have “substance-independent minds” housed in non-biological bodies.

In 2011, he stepped back from his work as an internet entrepreneur to lead the project, which he runs from his home in Moscow. He has traveled to New York this week to host a conference at which luminaries such as Marvin Minsky and Ray Kurzweil will discuss this new evolutionary approach.

Though his endeavor immediately conjures up visions of robotic humanoids and artificial organs, Itskov is most concerned with how immortality will reshape the mind.

“Immortality is a side effect,” he explains, describing eternal life as a means of transforming and improving human consciousness. Decoupling the mind from the needy human body, which demands food, medicine and shelter, can curb our negative inclinations and pave the way for a more elevated and sublime human spirit, he believes.

“Sometimes the way people live makes me think that they’re just following programs,” he says. “We should try to look for the opportunity to develop spiritually.”

Itskov is preparing for eternal life by training himself to attain a higher state of consciousness, and he gives the impression of someone who considers his body only insofar as it hinders or helps his mental pursuits. He spends several hours a day meditating, doing yoga or engaged in breathing exercises, all part of a spiritual practice he says helps him “discover some different states of my consciousness.”

His diet is guided by how different foods affect his energy. Meat gives him an energy he’s “not comfortable with,” he says. Alcohol “affects the consciousness” so "you stop feeling the real nature of it.” Even ice water is off limits because it lowers energy, Itskov tells a documentary filmmaker who’s offered him a cup of ice water while her crew sets up in his hotel room.

Itskov, who has close-shaven blonde hair and a vague shadow of stubble, speaks softly, slowly and with the calm self-assurance of someone who’s used to considering much more cosmic questions than those being posed to him.

How certain is he that humans will attain immortality by 2045?

“I am 100 percent certain,” he answers.

And what gives him that certainty?

“My belief," he says. He pauses for a moment, then continues: "In an ancient text, I read that whatever we have in our mind, in our consciousness, whatever we intend to achieve, we will achieve. It depends when, and it depends on the internal certainty."

Questions are frequently answered with a question -- is he religious? “What is religion?” -- and even the nature of death is up for debate. Doctors can measure the death of the physical body, says Itskov, but no one has determined how to evaluate the death of consciousness.

Itskov has already considered a world in which biology is obsolete, and bodies are supplanted by holograms or avatars.("If the technology advances, I think there will be no need for biology at all," he says.)

Within a century, he tells the filmmaker, we’ll frequent “body service shops” where we can choose our bodies from a catalog, then transfer our consciousness to one better-suited for, say, life on Mars. He seems to find the world’s relentless focus on carnal matters to be quite tedious, and laments to the documentary crew that every interviewer asks him how his vision will affect eating, procreating and having sex.

“Why don’t people think about something more sophisticated than just food, sex and children?” he asks. “By the way, if you live in this biological body for 80 years and have five or six children, isn’t that enough? Why don’t you start living for a greater purpose than to just help raise your children?”

Itskov’s quest for a deeper consciousness hasn’t stopped him from indulging in a few earthly pleasures: When we sit down for an interview, he has on a Burberry button-down and Louis Vuitton sneakers.

So what does someone do for fun if he knows he’ll live forever? Itskov is content to dedicate his life to the pursuit of eternal life. He has no wife, children or immediate plans to have either, and spends just one week a month at his home in Moscow. The rest of the time he’s traveling between the U.S., Europe, India and China meeting with experts and potential supporters.

“We are mostly having fast fun in this world," says Itskov, likening fast fun to fast food. "But we are not thinking of a more essential fun, which is inside of us.”

Itskov says he has fond memories of visiting the Salvador Dali Theater and Museum in Figueres, and he loves the Prado Museum in Madrid. He's partial to paintings by El Greco and Goya. But once his mission has been realized, three decades from now, Itskov says he will seek out solitude, not sightseeing

“What will be intriguing to me is the process of development of my personal consciousness,” he tells the crew of filmmakers. “Probably, I’ll be sitting somewhere up in the mountains, just meditating.”

Published on June 17, 2013 13:13

June 14, 2013

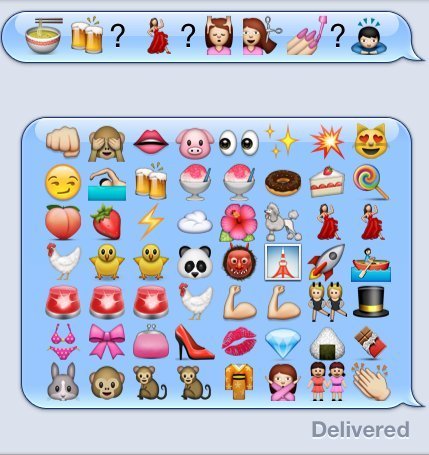

The Appeal Of Emoji: They Don't Say Anything

A few years ago, I staged an emoticon intervention with my father.

I'd realized with horror that he had been sprinkling smiley faces into the messages he sent to his friends, relatives and even business acquaintances, so I sat him down for a stern conversation about the crippling un-coolness that the habit conveyed. No one, I told him, should be caught dead using .

.

At the time, I congratulated myself on being a caring daughter who'd saved her father from looking like a fool. Yet recently, I've realized my dad was just an early adopter.

Emoticons and their more intricate Japanese cousins, emoji, have been enjoying a renaissance, while stickers -- cartoon-like digital illustrations -- are carving out a niche of their own.

The growing popularity of all this cutesy communication is usually attributed to the difficulty people have conveying emotion and nuance via quickly-typed text. But emoji and their ilk are more than elaborate punctuation marks, and in fact part of their appeal is precisely their indefinite meaning. They're a way to say something to someone when you don't have anything to say, a digital alter ego that establishes a virtual presence with another person, without any specific purpose besides "hi." Using emoji, in a sense, is like hanging out online.

In the past year, frowny faces, clinking beer mugs, adorable chicken legs and other illustrations have become virtually omnipresent online. My Instagram feed frequently has more emoji than photographs: Snapshots are captioned with a sprinkling of emoji, which range from the mundane (heart, kissy lips, crying face) to the poetic (bowl of ramen, power plant, dancing girls in black leotards and cat ears).

Facebook recently launched its own breed of emoticons, a stable of yellow faces depicting feelings of disappointment, annoyance and the feeling "meh" that are based on research done by Darwin. Startups are even touting stickers as a business model: The social networking app Path launched a store that peddles its own, branded stickers, while Lango, a messaging app that sells images users can add to their texts, said hundreds of people had purchased its $99.99 all-inclusive sticker packs within a few weeks of the app's launch. An app created by Snoop Lion, aka Snoop Dogg, sells $30,000 a week worth of digital stickers, according to the Wall Street Journal.

And while my father still isn't the typical emoji and emoticon user, emoji use in Japan spread from teenage girls, their early adopters, through all demographics. Lango notes that its users are currently about 40 percent male, and between 15 and 25 years old on average.

As we continue communicating more consistently, with more people, in more places, than before, we've turned to images as a way to transpose some offline customs, like comfortable silences between friends, into the online realm.

Mimi Ito, a cultural anthropologist researching technology use at the University of California, Irvine, explains that while email and desktop correspondence tends to be focused on completing a set task, a great deal of mobile communication -- given how frequently we have our hands on our phones -- is about sharing an "ambient state of being." People tend to text a great deal with just two to three people they know well, but they simultaneously seek to maintain a "virtual co-presence" with nearly a dozen acquaintances.

In these cases, pictures -- vague, but also personalized -- come in handy. A typed message seeks a definite outcome or answer. Emoji are like the smile from a colleague across the room, or the small talk you make walking to get coffee. It's pointless communication that nonetheless puts you in a good mood.

"Part of the reason the volume of text messaging is so high because lot of exchange is just, 'This is what I'm doing, this is what I'm feeling,' which is transmitting, 'I'm here with you, I'm connected to you,'" said Ito. "People often like to feel like they're inhabiting the same space as each other... Emoji and emoticons are really good for conveying that kind of thing."