Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 13

May 23, 2013

What Really Happens On A Teen Girl's iPhone

MILLBURN, N.J. -- Fourteen-year-old Casey Schwartz has ditched more social networking services than most people her parents’ age have joined. Like many of her friends, Casey has a tendency to embrace social media sites, then suddenly drop them.

Skype, Formspring and WhatsApp have all felt the consequences of these flighty users. Casey still uses Snapchat, but less than she did last year. And in three months, she's joined, quit, and rejoined Twitter. She’s collected banished apps into a folder on her phone labeled “Stuff Nobody Likes.” And she’s thought about deleting her Facebook account because she checks it so frequently.

“I’ll wake up in the morning and go on Facebook just … because,” Casey says. “It's not like I want to or I don’t. I just go on it. I’m, like, forced to. I don’t know why. I need to. Facebook takes up my whole life."

Inseparable from her iPhone, but apt to tire of the sites she uses it to access, Casey at once personifies why much of the technology world has become obsessed with capturing the attention of people her age, and why those efforts risk turning into expensive debacles. That teens' friendships and relationships will play out online is certain. But which site will host that social intrigue is constantly up for grabs.

Earlier this week, Yahoo became the latest tech giant to make a major play for younger users, agreeing to pay $1.1 billion in cash to take ownership of Tumblr, the blogging site that has emerged as a popular and engaging platform with users under the age of 35. Yahoo has in its sights young people with disposable income, still-evolving spending habits and a willingness to devote virtually unlimited amounts of time to staring at a screen.

In short, Yahoo is trying to gain access to people like Casey. As social media experts have already suggested, and as a day with Casey makes clear, winning the attention of teenagers and maintaining it are two very different things. Yet seeking that attention is irresistible.

Casey’s habits underscore a new reality for this networked generation: Social networks -- and the gadgets they run on -- aren’t a distraction from real life, but a crucial extension of it.

Born in 1999, just a few years after the mass adoption of the World Wide Web, Casey belongs to the first true generation of digital natives, who have no memory of life before the Internet. The eighth-grader, who lives in the northern New Jersey town of Millburn, has always been attached to her gadgets. When she was only 18 months old, she received a toy computer that quickly became her favorite plaything. In second grade, she got her first cellphone (“it could hold two numbers, it was stupid,” she says). Now, at 14, she’s the proud owner of a white iPhone 4S, which she takes with her to school, carries as she wanders around her house, uses at the breakfast table, and keeps beside her pillow when she sleeps at night.

“I bring it everywhere. I have to be holding it,” Casey says. “It’s like OCD -- I have to have it with me. And I check it a lot.”

Casey only parts with her phone during the hours she’s at school, when she leaves it in her locker. The rest of the time, she and seven friends keep up a running conversation over text messages.

Not having an iPhone can be social suicide, notes Casey. One of her friends found herself effectively exiled from their circle for six months because her parents dawdled in upgrading her to an iPhone. Without it, she had no access to the iMessage group chat, where it seemed all their shared plans were being made.

"She wasn’t in the group chat, so we stopped being friends with her,” Casey says. “Not because we didn’t like her, but we just weren’t in contact with her.”

On a recent Thursday, Casey and her friends are up texting on iMessage until midnight, then they pick up again around 7 a.m., when they wake for school. By 4 p.m. that day, the group has exchanged more than 56 messages, not including those sent in the private, one-on-one chats Casey also kept going during the day.

“That’s not even a lot. That’s small. And we were in school the whole day also,” Casey says.

Early that morning, they kicked off their conversation polling each other on what they’d wear to school.

“Shorts?” someone wrote, followed by, “Should I?”

“I’m not.”

“What are you wearing?”

“Leggings.”

“Would it be weird if I wore my Hunters [rainboots]?"

“Is the bus there?”

Later, the girls cast votes on which picture each should share for "TBT" (short for Throwback Thursday), a weekly Instagram tradition, where people post childhood photos. The typical teen girl will send and receive 165 text messages in a day, according to a 2012 report by the Pew Research Center. Casey's texting continues even when she and her friends are together.

“We’ll be sitting on a couch next to each other, texting each other,” she notes. “We text in the same room. It’s weird, I don’t know why.”

As we chat in her lime-and-lavender painted room, surrounded by soccer trophies and a framed collage of Justin Bieber photos, Casey alternates between checking her phone, which buzzes incessantly with a steady stream of texts, replying to messages, and refreshing her Instagram and Facebook feeds, where she “likes” people’s posts. Occasionally, she plays a few rounds on Dots, her new favorite iPhone game, or scrolls through fashion accessories on Wanelo, a social shopping site heavy on photos. Later, Casey uses Facebook to get homework help and posts a question in a private group chat set up by her classmates.

Casey’s social networking faces scrutiny from her mother, who has her own Instagram and Facebook accounts from which to monitor what Casey and her friends are doing online. Occasionally, Casey's mother will insist that a picture her daughter has shared needs to come down -- usually because Casey has been "exclusive," posting a photo of that could offend friends who weren't included in that day's activity. Via Apple's Find My iPhone app, the Schwartz family can also keep constant tabs on each other's location.

Thanks to Silicon Valley, there's no off-switch for one’s social life, and popularity has become instantly quantifiable.

Here are just a few of the things Casey regularly tracks: the number of contacts stored on her iPhone (187); the number of people following her on Instagram (around 580); the number of people who’ve asked to follow her on Instagram, but she’s refused to accept (more than 100); the number of people following her Tumblr blog (more than 100); her high score on Dots (almost 400); the number of photos she stores on her phone (363, fewer than before because she's maxed out her phone’s memory); the number of photos her friends store on their phones (around 800); the number of people she’s friends with on Facebook (1,110) and the number of acquaintances who’ve quit Facebook (three or four). She also uses the app InstaFollow to keeps tabs on who's unfollowed her on Instagram (she quickly unfollows those who defect).

Casey is a novice programmer and has customized the code on her Tumblr blog so it displays how many people are viewing it at one time. She and her friends aspire to becoming “Tumblr famous,” or attracting thousands of followers to their sites. She's wary of what will become of Tumblr under Yahoo's watchful, corporate eye.

"I don’t like that they bought it," she explains, echoing sentiments shared by others who use the media network. "I'd rather it was how it was before because I'm afraid they're going to change it and make it worse."

The most important and stress-inducing statistic of all is the number of “likes” she gets when she posts a new Facebook profile picture -- followed closely by how many “likes” her friends’ photos receive. Casey's most recent profile photo received 117 "likes" and 56 comments from her friends, 19 of which they posted within a minute of Casey switching her photo, and all of which Casey “liked” personally.

“If you don’t get 100 ‘likes,’ you make other people share it so you get 100,” she explains. “Or else you just get upset. Everyone wants to get the most ‘likes.’ It’s like a popularity contest.”

Still, she notes with a twinge of regret that a friend received more.

“I changed my profile picture and then [my friend] changed it right after and she got so many more 'likes' than I did,” Casey says. “And I didn’t get mad at her, but I was like, 'You got so many 'likes!'’ She just gets so many 'likes' on everything. She has more followers on Instagram. I have more friends than her.”

For all the time Casey spends online, she predicts that soon she won’t be using her smartphone or social networks as much as she has been. It’s distracting, she says, as her iPhone chimes for perhaps the 12th time that hour. Her phone, be it Facebook, Instagram or iMessage, is constantly pulling her away from her homework, or her sleep, or her conversations with her family.

“If I’m not watching TV, I’m on my phone. If I’m not on my phone, I’m on my computer. If I’m not doing any of those things, what am I supposed to do?” Casey says. “I think that in a few years, technology is going to go back and people won’t use it anymore because it’s getting to be a lot. I mean, I don’t put down my phone. And it makes me wish that I did. It's addicting.”

But at least for now, her iPhone remains the center of her existence. The friend who was the last to buy an iPhone has recently purchased one, regaining her place among the circle.

“Now we start hanging out with her every week because she knows the plans,” says Casey. “She has a smartphone now, so that’s what gets her in. We always loved her and she was always our good friend, but she was excluded -- and she knew it, too -- because she didn’t have an iPhone.”

Skype, Formspring and WhatsApp have all felt the consequences of these flighty users. Casey still uses Snapchat, but less than she did last year. And in three months, she's joined, quit, and rejoined Twitter. She’s collected banished apps into a folder on her phone labeled “Stuff Nobody Likes.” And she’s thought about deleting her Facebook account because she checks it so frequently.

“I’ll wake up in the morning and go on Facebook just … because,” Casey says. “It's not like I want to or I don’t. I just go on it. I’m, like, forced to. I don’t know why. I need to. Facebook takes up my whole life."

Inseparable from her iPhone, but apt to tire of the sites she uses it to access, Casey at once personifies why much of the technology world has become obsessed with capturing the attention of people her age, and why those efforts risk turning into expensive debacles. That teens' friendships and relationships will play out online is certain. But which site will host that social intrigue is constantly up for grabs.

Earlier this week, Yahoo became the latest tech giant to make a major play for younger users, agreeing to pay $1.1 billion in cash to take ownership of Tumblr, the blogging site that has emerged as a popular and engaging platform with users under the age of 35. Yahoo has in its sights young people with disposable income, still-evolving spending habits and a willingness to devote virtually unlimited amounts of time to staring at a screen.

In short, Yahoo is trying to gain access to people like Casey. As social media experts have already suggested, and as a day with Casey makes clear, winning the attention of teenagers and maintaining it are two very different things. Yet seeking that attention is irresistible.

Casey’s habits underscore a new reality for this networked generation: Social networks -- and the gadgets they run on -- aren’t a distraction from real life, but a crucial extension of it.

Born in 1999, just a few years after the mass adoption of the World Wide Web, Casey belongs to the first true generation of digital natives, who have no memory of life before the Internet. The eighth-grader, who lives in the northern New Jersey town of Millburn, has always been attached to her gadgets. When she was only 18 months old, she received a toy computer that quickly became her favorite plaything. In second grade, she got her first cellphone (“it could hold two numbers, it was stupid,” she says). Now, at 14, she’s the proud owner of a white iPhone 4S, which she takes with her to school, carries as she wanders around her house, uses at the breakfast table, and keeps beside her pillow when she sleeps at night.

“I bring it everywhere. I have to be holding it,” Casey says. “It’s like OCD -- I have to have it with me. And I check it a lot.”

Casey only parts with her phone during the hours she’s at school, when she leaves it in her locker. The rest of the time, she and seven friends keep up a running conversation over text messages.

Not having an iPhone can be social suicide, notes Casey. One of her friends found herself effectively exiled from their circle for six months because her parents dawdled in upgrading her to an iPhone. Without it, she had no access to the iMessage group chat, where it seemed all their shared plans were being made.

"She wasn’t in the group chat, so we stopped being friends with her,” Casey says. “Not because we didn’t like her, but we just weren’t in contact with her.”

On a recent Thursday, Casey and her friends are up texting on iMessage until midnight, then they pick up again around 7 a.m., when they wake for school. By 4 p.m. that day, the group has exchanged more than 56 messages, not including those sent in the private, one-on-one chats Casey also kept going during the day.

“That’s not even a lot. That’s small. And we were in school the whole day also,” Casey says.

Early that morning, they kicked off their conversation polling each other on what they’d wear to school.

“Shorts?” someone wrote, followed by, “Should I?”

“I’m not.”

“What are you wearing?”

“Leggings.”

“Would it be weird if I wore my Hunters [rainboots]?"

“Is the bus there?”

Later, the girls cast votes on which picture each should share for "TBT" (short for Throwback Thursday), a weekly Instagram tradition, where people post childhood photos. The typical teen girl will send and receive 165 text messages in a day, according to a 2012 report by the Pew Research Center. Casey's texting continues even when she and her friends are together.

“We’ll be sitting on a couch next to each other, texting each other,” she notes. “We text in the same room. It’s weird, I don’t know why.”

As we chat in her lime-and-lavender painted room, surrounded by soccer trophies and a framed collage of Justin Bieber photos, Casey alternates between checking her phone, which buzzes incessantly with a steady stream of texts, replying to messages, and refreshing her Instagram and Facebook feeds, where she “likes” people’s posts. Occasionally, she plays a few rounds on Dots, her new favorite iPhone game, or scrolls through fashion accessories on Wanelo, a social shopping site heavy on photos. Later, Casey uses Facebook to get homework help and posts a question in a private group chat set up by her classmates.

Casey’s social networking faces scrutiny from her mother, who has her own Instagram and Facebook accounts from which to monitor what Casey and her friends are doing online. Occasionally, Casey's mother will insist that a picture her daughter has shared needs to come down -- usually because Casey has been "exclusive," posting a photo of that could offend friends who weren't included in that day's activity. Via Apple's Find My iPhone app, the Schwartz family can also keep constant tabs on each other's location.

Thanks to Silicon Valley, there's no off-switch for one’s social life, and popularity has become instantly quantifiable.

Here are just a few of the things Casey regularly tracks: the number of contacts stored on her iPhone (187); the number of people following her on Instagram (around 580); the number of people who’ve asked to follow her on Instagram, but she’s refused to accept (more than 100); the number of people following her Tumblr blog (more than 100); her high score on Dots (almost 400); the number of photos she stores on her phone (363, fewer than before because she's maxed out her phone’s memory); the number of photos her friends store on their phones (around 800); the number of people she’s friends with on Facebook (1,110) and the number of acquaintances who’ve quit Facebook (three or four). She also uses the app InstaFollow to keeps tabs on who's unfollowed her on Instagram (she quickly unfollows those who defect).

Casey is a novice programmer and has customized the code on her Tumblr blog so it displays how many people are viewing it at one time. She and her friends aspire to becoming “Tumblr famous,” or attracting thousands of followers to their sites. She's wary of what will become of Tumblr under Yahoo's watchful, corporate eye.

"I don’t like that they bought it," she explains, echoing sentiments shared by others who use the media network. "I'd rather it was how it was before because I'm afraid they're going to change it and make it worse."

The most important and stress-inducing statistic of all is the number of “likes” she gets when she posts a new Facebook profile picture -- followed closely by how many “likes” her friends’ photos receive. Casey's most recent profile photo received 117 "likes" and 56 comments from her friends, 19 of which they posted within a minute of Casey switching her photo, and all of which Casey “liked” personally.

“If you don’t get 100 ‘likes,’ you make other people share it so you get 100,” she explains. “Or else you just get upset. Everyone wants to get the most ‘likes.’ It’s like a popularity contest.”

Still, she notes with a twinge of regret that a friend received more.

“I changed my profile picture and then [my friend] changed it right after and she got so many more 'likes' than I did,” Casey says. “And I didn’t get mad at her, but I was like, 'You got so many 'likes!'’ She just gets so many 'likes' on everything. She has more followers on Instagram. I have more friends than her.”

For all the time Casey spends online, she predicts that soon she won’t be using her smartphone or social networks as much as she has been. It’s distracting, she says, as her iPhone chimes for perhaps the 12th time that hour. Her phone, be it Facebook, Instagram or iMessage, is constantly pulling her away from her homework, or her sleep, or her conversations with her family.

“If I’m not watching TV, I’m on my phone. If I’m not on my phone, I’m on my computer. If I’m not doing any of those things, what am I supposed to do?” Casey says. “I think that in a few years, technology is going to go back and people won’t use it anymore because it’s getting to be a lot. I mean, I don’t put down my phone. And it makes me wish that I did. It's addicting.”

But at least for now, her iPhone remains the center of her existence. The friend who was the last to buy an iPhone has recently purchased one, regaining her place among the circle.

“Now we start hanging out with her every week because she knows the plans,” says Casey. “She has a smartphone now, so that’s what gets her in. We always loved her and she was always our good friend, but she was excluded -- and she knew it, too -- because she didn’t have an iPhone.”

Published on May 23, 2013 05:00

May 22, 2013

Google Glass 'Winners' Can Buy Glass Now

Google announced Wednesday that it will begin shipping Google Glass to the 8,000 individuals chosen to purchase an early version of the tech giant's wearable computing device.

In February, Google launched a contest inviting U.S. residents to submit applications detailing how they'd use Glass for a chance to join Google's Explorer Program. Glass Explorers would be able to buy an early version of Glass for $1,500, months before the product's forthcoming release to the public at large. General sales for Glass are expected to start in late 2013 or early 2014.

Google selected the "winners" at the end of March, and will now begin taking orders. Glass, which suspends a small glass cube over the wearer's right eye, allows people to search the web, translate phrases, send messages, take photos and film video, among other capabilities. Developers from Twitter, Elle, The New York Times, Facebook and other companies have already announced plans to create applications for Glass.

"In February, we opened up the Explorer Program by asking people across Google+ and Twitter what they would do if they had Glass. We were looking for bold, creative individuals to become our next wave of Explorers -- and wow, did we get them," Google's Project Glass team wrote in a post shared on Google+. "Over the next few weeks, we’ll be slowly rolling out invitations to successful #ifihadglass applicants. If you were one of the successful applicants, please make sure you have +Project Glass in your Circles so we can send you a message."

Google also tweeted that people selected for the program should follow @ProjectGlass in order to receive a direct message with instructions for ordering Glass. According to Marketing Land's Matt McGee, Google's emailed instructions for purchasing Glass specified that he should phone a 1-800 number, and then order Glass by sharing his "unique code" (and, presumably, his credit card information).

While some 8,000 people will be eligible to purchase Glass, it's unlikely that that many will shell out $1,500 for a still-buggy piece of technology -- albeit one as futuristic as Glass. Crowdfunding websites like Kickstarter, Indiegogo and FundMe have been teeming with requests from people hoping to raise money to buy Glass.

"My daughter has two hobbies: jumping horses & making videos. Using Google Glass will let her share the experience from her perspective," wrote one Kickstarter user, whose campaign failed to raise the $1,500 he was seeking within its deadline.

On Indiegogo, fundraisers seeking the cash to buy Glass are pitching it as a way for them to reinvent live performance, document life as an "avid social media user...in South Korea," experiment with new teaching approaches inside a school classroom and capture New Orleans "through the eyes of a native." There's even someone hoping to use Glass to document the Battle of Gettysburg as seen by a historical reenactor.

There are also privacy concerns surrounding the use of Glass -- members of Congress wrote to Larry Page last week asking him to clarify Glass' privacy safeguards -- and questions about whether its unusual appearance could prevent mass adoption. Glass has been described as "freakish" and "nerdy."

Google announced last week that it had finished distributing Glass to its first group of trial users, the 2,000 developers who signed up to receive the device at the 2012 Google I/O developer conference.

In February, Google launched a contest inviting U.S. residents to submit applications detailing how they'd use Glass for a chance to join Google's Explorer Program. Glass Explorers would be able to buy an early version of Glass for $1,500, months before the product's forthcoming release to the public at large. General sales for Glass are expected to start in late 2013 or early 2014.

Google selected the "winners" at the end of March, and will now begin taking orders. Glass, which suspends a small glass cube over the wearer's right eye, allows people to search the web, translate phrases, send messages, take photos and film video, among other capabilities. Developers from Twitter, Elle, The New York Times, Facebook and other companies have already announced plans to create applications for Glass.

"In February, we opened up the Explorer Program by asking people across Google+ and Twitter what they would do if they had Glass. We were looking for bold, creative individuals to become our next wave of Explorers -- and wow, did we get them," Google's Project Glass team wrote in a post shared on Google+. "Over the next few weeks, we’ll be slowly rolling out invitations to successful #ifihadglass applicants. If you were one of the successful applicants, please make sure you have +Project Glass in your Circles so we can send you a message."

Google also tweeted that people selected for the program should follow @ProjectGlass in order to receive a direct message with instructions for ordering Glass. According to Marketing Land's Matt McGee, Google's emailed instructions for purchasing Glass specified that he should phone a 1-800 number, and then order Glass by sharing his "unique code" (and, presumably, his credit card information).

While some 8,000 people will be eligible to purchase Glass, it's unlikely that that many will shell out $1,500 for a still-buggy piece of technology -- albeit one as futuristic as Glass. Crowdfunding websites like Kickstarter, Indiegogo and FundMe have been teeming with requests from people hoping to raise money to buy Glass.

"My daughter has two hobbies: jumping horses & making videos. Using Google Glass will let her share the experience from her perspective," wrote one Kickstarter user, whose campaign failed to raise the $1,500 he was seeking within its deadline.

On Indiegogo, fundraisers seeking the cash to buy Glass are pitching it as a way for them to reinvent live performance, document life as an "avid social media user...in South Korea," experiment with new teaching approaches inside a school classroom and capture New Orleans "through the eyes of a native." There's even someone hoping to use Glass to document the Battle of Gettysburg as seen by a historical reenactor.

There are also privacy concerns surrounding the use of Glass -- members of Congress wrote to Larry Page last week asking him to clarify Glass' privacy safeguards -- and questions about whether its unusual appearance could prevent mass adoption. Glass has been described as "freakish" and "nerdy."

Google announced last week that it had finished distributing Glass to its first group of trial users, the 2,000 developers who signed up to receive the device at the 2012 Google I/O developer conference.

Published on May 22, 2013 12:30

May 21, 2013

How Teens Are Really Using Facebook: It's a 'Social Burden,' Pew Study Finds

The Facebook generation is fed up with Facebook.

That's according to a report released Tuesday by the Pew Research Center, which surveyed 802 teens between the ages of 12 and 17 last September to produce a 107-page report on their online habits.

Pew's findings suggest teens' enthusiasm for Facebook is waning, lending credence to concerns, raised by the company's investors and others that the social network may be losing a crucial demographic that has long fueled its success.

Facebook has become a "social burden" for teens, write the authors of the Pew report. "While Facebook is still deeply integrated in teens’ everyday lives, it is sometimes seen as a utility and an obligation rather than an exciting new platform that teens can claim as their own."

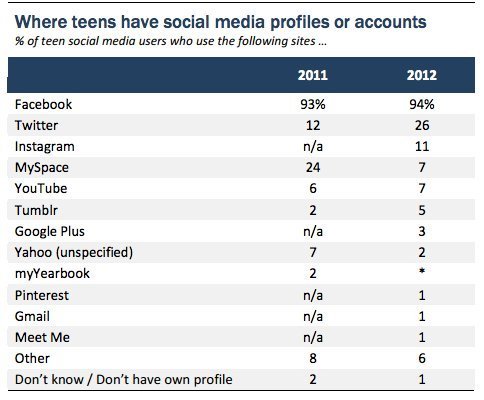

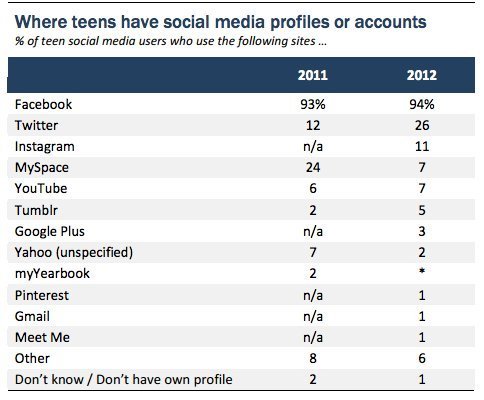

Teen's aren't abandoning Facebook -- deactivating their accounts would mean missing out on the crucial social intrigues that transpire online -- and 94 percent of teenage social media users still have profiles on the site, Pew's report notes. But they're simultaneously migrating to Twitter and Instagram, which teens say offer a parent-free place where they can better express themselves. Eleven percent of teens surveyed had Instagram accounts, while the number of teen Twitter users climbed from 16 percent in 2011 to 24 percent in 2012. Five percent of teens have accounts on Tumblr, which was just purchased by Yahoo for $1.1 billion, while 7 percent have accounts on Myspace.

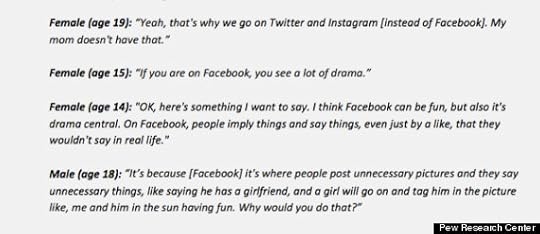

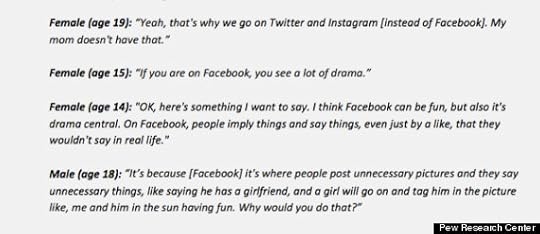

Facebook, teens say, has been overrun by parents, fuels unnecessary social "drama" and gives a mouthpiece to annoying oversharers who drone on about inane events in their lives.

“Honestly, Facebook at this point, I'm on it constantly but I hate it so much,” one 15 year-old girl told Pew during a focus group.

"I got mine [Facebook account] around sixth grade. And I was really obsessed with it for a while," another 14 year-old said. "Then towards eighth grade, I kind of just -- once you get into Twitter, if you make a Twitter and an Instagram, then you'll just kind of forget about Facebook, is what I did.”

On the whole, teens' usage of social media seems to have plateaued, and the fraction of those who check social sites "several times a day" has stayed steady at around 40 percent since 2011.

Asked about teens' Facebook habits during a recent earnings call with investors, Facebook's chief financial officer answered that the company “remain[s] really pleased with the high level of engagement on Facebook by people of all ages around the world" and called younger users "among the most active and engaged users that we have on Facebook."

Here's what that "high level of engagement" really looks like, according to Pew:

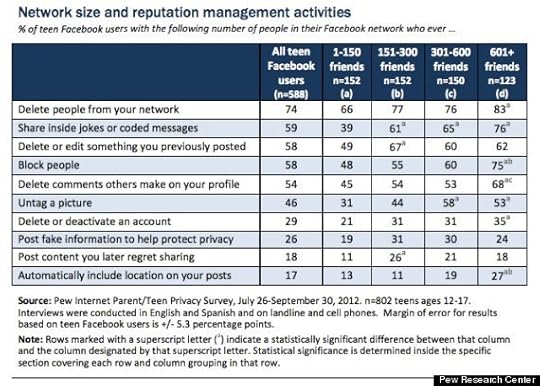

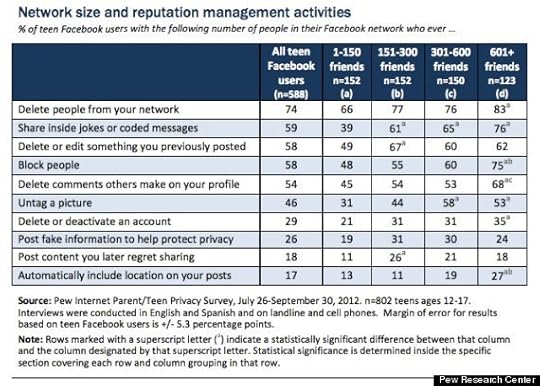

They’re deleting, lying and blocking: As the chart below shows, some three-quarters of Facebook users have purged friends on Facebook, 58 percent have edited or deleted content they’ve shared and 26 percent have tried to protect their privacy by sharing false information. Among all teens online (not just Facebook users), 39 percent have lied about their age. The report also notes, "Girls are more likely than boys to delete friends from their network (82 percent vs. 66 percent) and block people (67 percent vs. 48 percent)."

Superusers on Facebook are superusers on other social sites: Teens with large friend networks on Facebook are more likely than their peers to have profiles on other social media sites: 46 percent of teens with over 600 Facebook friends have a Twitter profile, and 12 percent of such users have an Instagram account. By comparison, just 21 percent and 11 percent of teens who have 150 to 300 friends have Twitter and Instagram accounts, respectively.

Teens have hundreds of friends, but they haven’t met them all: The typical Facebook-using teen has 300 friends, though girls are more likely to have more friends (the median is 350) than boys (300). Seventy percent of teens are friends with their parents, 30 percent are friends with teachers or coaches, and 33 percent are friends with people they’ve never met in person.

It turns out parents actually do see what their kids are posting: Just 5 percent of teens tweak their privacy to limit what their parents see.

They’re watching out for their privacy: Sixty percent of teens on Facebook say they’ve checked their privacy settings in the past month -- a third of them within the past seven days. The majority (60 percent) of teens have their profiles set to private, while 14 percent have profiles that are completely public.

But yes, they are sharing personal details: Teens with more Facebook friends are more likely to share a greater variety of personal details about themselves online. Among all teens on Facebook, 21 percent share their cell phone number, 63 percent share their relationship status and 54 perent share their email address.

Seventeen percent of teens on Facebook will automatically share their location in their posts, and 18 percent say they’ve shared something they later regret posting.

They’re enjoying themselves, but they’ve been contacted by creeps: Among all teens surveyed by Pew, 17 percent have been contacted by strangers in a way that made them “scared or uncomfortable.” However, 57 percent of social media-using teens said they’ve had an experience online that “made them feel good about themselves,” and 37 percent say social media has made them feel more connected to someone else.

That's according to a report released Tuesday by the Pew Research Center, which surveyed 802 teens between the ages of 12 and 17 last September to produce a 107-page report on their online habits.

Pew's findings suggest teens' enthusiasm for Facebook is waning, lending credence to concerns, raised by the company's investors and others that the social network may be losing a crucial demographic that has long fueled its success.

Facebook has become a "social burden" for teens, write the authors of the Pew report. "While Facebook is still deeply integrated in teens’ everyday lives, it is sometimes seen as a utility and an obligation rather than an exciting new platform that teens can claim as their own."

Teen's aren't abandoning Facebook -- deactivating their accounts would mean missing out on the crucial social intrigues that transpire online -- and 94 percent of teenage social media users still have profiles on the site, Pew's report notes. But they're simultaneously migrating to Twitter and Instagram, which teens say offer a parent-free place where they can better express themselves. Eleven percent of teens surveyed had Instagram accounts, while the number of teen Twitter users climbed from 16 percent in 2011 to 24 percent in 2012. Five percent of teens have accounts on Tumblr, which was just purchased by Yahoo for $1.1 billion, while 7 percent have accounts on Myspace.

Facebook, teens say, has been overrun by parents, fuels unnecessary social "drama" and gives a mouthpiece to annoying oversharers who drone on about inane events in their lives.

“Honestly, Facebook at this point, I'm on it constantly but I hate it so much,” one 15 year-old girl told Pew during a focus group.

"I got mine [Facebook account] around sixth grade. And I was really obsessed with it for a while," another 14 year-old said. "Then towards eighth grade, I kind of just -- once you get into Twitter, if you make a Twitter and an Instagram, then you'll just kind of forget about Facebook, is what I did.”

On the whole, teens' usage of social media seems to have plateaued, and the fraction of those who check social sites "several times a day" has stayed steady at around 40 percent since 2011.

Asked about teens' Facebook habits during a recent earnings call with investors, Facebook's chief financial officer answered that the company “remain[s] really pleased with the high level of engagement on Facebook by people of all ages around the world" and called younger users "among the most active and engaged users that we have on Facebook."

Here's what that "high level of engagement" really looks like, according to Pew:

They’re deleting, lying and blocking: As the chart below shows, some three-quarters of Facebook users have purged friends on Facebook, 58 percent have edited or deleted content they’ve shared and 26 percent have tried to protect their privacy by sharing false information. Among all teens online (not just Facebook users), 39 percent have lied about their age. The report also notes, "Girls are more likely than boys to delete friends from their network (82 percent vs. 66 percent) and block people (67 percent vs. 48 percent)."

Superusers on Facebook are superusers on other social sites: Teens with large friend networks on Facebook are more likely than their peers to have profiles on other social media sites: 46 percent of teens with over 600 Facebook friends have a Twitter profile, and 12 percent of such users have an Instagram account. By comparison, just 21 percent and 11 percent of teens who have 150 to 300 friends have Twitter and Instagram accounts, respectively.

Teens have hundreds of friends, but they haven’t met them all: The typical Facebook-using teen has 300 friends, though girls are more likely to have more friends (the median is 350) than boys (300). Seventy percent of teens are friends with their parents, 30 percent are friends with teachers or coaches, and 33 percent are friends with people they’ve never met in person.

It turns out parents actually do see what their kids are posting: Just 5 percent of teens tweak their privacy to limit what their parents see.

They’re watching out for their privacy: Sixty percent of teens on Facebook say they’ve checked their privacy settings in the past month -- a third of them within the past seven days. The majority (60 percent) of teens have their profiles set to private, while 14 percent have profiles that are completely public.

But yes, they are sharing personal details: Teens with more Facebook friends are more likely to share a greater variety of personal details about themselves online. Among all teens on Facebook, 21 percent share their cell phone number, 63 percent share their relationship status and 54 perent share their email address.

Seventeen percent of teens on Facebook will automatically share their location in their posts, and 18 percent say they’ve shared something they later regret posting.

They’re enjoying themselves, but they’ve been contacted by creeps: Among all teens surveyed by Pew, 17 percent have been contacted by strangers in a way that made them “scared or uncomfortable.” However, 57 percent of social media-using teens said they’ve had an experience online that “made them feel good about themselves,” and 37 percent say social media has made them feel more connected to someone else.

Published on May 21, 2013 11:44

Yahoo's Got Tumblr's Teens -- But For How Long?

In paying $1.1 billion for Tumblr, Yahoo has just gotten the attention of the 300 million, predominantly young people who have made the site one of the most engaged communities on the web.

But hanging on to that community may be difficult, say analysts, while focusing on an emerging truth of the web: Though young people beckon as the most prized of users, they can also be markedly fickle. Yahoo just paid a bundle to reach people who have proven easily distracted and inclined to move on.

It's a dilemma with which many social media sites are grappling, as they face off against a seemingly endless proliferation of new social networks all vying to be the favorite among millennials.

“Teens certainly look to en vogue websites, and in some cases they may be here today or gone tomorrow,” said Clark Fredrickson, a spokesman for eMarketer, a digital media market research firm. “Older generations have less free time, so it takes more time for their habits to change. The younger generation can spend hours a day on one site, get bored of it and switch to something else the next day.”

In a call with investors on Monday morning, Yahoo chief executive Marissa Mayer explained that Yahoo and Tumblr’s differing demographics would give the company’s advertisers access to a valuable new audience. More than 65 percent of Tumblr’s users are under 35, Tumblr chief executive David Karp told The Huffington Post at a Yahoo press conference Monday evening. Yahoo’s users, by contrast, “tend to be slightly older,” said Mayer.

Yet it remains to be seen how loyal those teens and 20-somethings are to the suite of sites they have embraced online -- from Tumblr and Twitter to Facebook and YouTube.

Like other social networking sites, Yahoo and Tumblr will be challenged to stay relevant to millennials, a population with an unquenchable appetite for the next new thing, an instinctive aversion to anything deemed uncool or corporate and the technical know-how to switch services easily. After all, teens and 20-somethings regularly outgrow their offline hangouts, gradually moving from their parents’ basements to bars and other spots. Who’s to say the same won’t happen online?

Karp maintained that Tumblr can hold onto its younger users because of its focus on content, rather than relationships. Mayer, for her part, referred to Tumblr not as a “social network” but as a “media network” during her call with investors Monday.

“I don’t think this has anything to do with, ‘We’re the social network of the moment.’ I think Tumblr is decidedly not social. It’s not about the people in your life, it’s not about relationships -- though it can grow into that -- but really, it’s about the stuff that you love,” Karp told The Huffington Post. “People come to Tumblr to find the stuff that they love, and that’s built on this incredibly creative community that we do everything to support.”

Tumblr helps people to create and distribute content, said Karp, who argued these activities are particularly popular among younger audiences.

“The thing about supporting creativity is that young people have much more boundless creativity,” Karp continued. “People start to give up when they get older. Creativity is a very human thing, but I think it’s something we all experience when we’re young.”

Yet some experts speculate that younger demographics may be more fickle than their parents or older peers. Not only do they have an ever-expanding selection of sites and services from which to choose, but these younger users are “more ambitious in what they explore,” noted Brian Solis, an analyst with Altimeter Group.

Just a few years ago, another mass media company paid top dollar for an up-and-coming social network that, like Tumblr, offered what reporters at the time deemed “a unique 'in' with the preteen, teen, and young-adult population” and that enjoyed “surging popularity with young audiences” -- Myspace.

Yet in the eight years since News Corporation’s 2005 acquisition of Myspace, the percentage of teens on the social media site has dropped dramatically. In 2006, 85 percent of teens who had social media accounts said their Myspace profile was the one they used most often, according to the Pew Research Center. By 2011, only a quarter of teens with social media accounts even had a Myspace profile.

Of course, Myspace’s dwindling popularity isn’t the only evidence that young users are inherently capricious in their online habits. Myspace's own strategic missteps -- and Facebook’s concurrent successes -- also help to account for the mass exodus. Yet Myspace’s foibles highlight how little tolerance millennials have for sites that go astray and the speed with which a flourishing site can find itself abandoned.

Though data are scant on millennials’ evolving usage of specific social media sites, a 2013 survey by investment bank Piper Jaffray suggests younger users have lately been turning away from sites like Facebook and YouTube that were once their preferred destinations. The proportion of teens that named Facebook the “most important social media site” fell 10 percent in the past year to just over 20 percent, according to Piper Jaffray. Tumblr’s importance also dropped slightly: Nearly 10 percent of teens identified Tumblr as the most important social media site in the spring of 2012, while just 5 percent said the same this year.

With so many alternatives from which young users can choose, social networking sites needn’t do anything besides mature to see their popularity plummet.

“If a site gets stale, millennials start to talk about banishing the network,” said Solis. “If a site starts to feel uncool, it is uncool. It has as much to do with the technology as the culture.”

Tumblr faces the real risk of becoming uncool by virtue of its association with Yahoo, noted Solis, and already some teens are threatening to leave the site.

“Karp has to make a strategic effort every day to protect Tumblr’s culture and evolve its culture so millennials feel like it evolves with them,” said Solis.

Karp already seems to be burnishing his anti-establishment street cred. The 26-year-old entrepreneur skipped Yahoo’s investor call on Monday morning to meet with Tumblr’s team, and signed off a blog post announcing Tumblr’s acquisition with a flippant, four-letter salutation: “f*** yeah.”

But hanging on to that community may be difficult, say analysts, while focusing on an emerging truth of the web: Though young people beckon as the most prized of users, they can also be markedly fickle. Yahoo just paid a bundle to reach people who have proven easily distracted and inclined to move on.

It's a dilemma with which many social media sites are grappling, as they face off against a seemingly endless proliferation of new social networks all vying to be the favorite among millennials.

“Teens certainly look to en vogue websites, and in some cases they may be here today or gone tomorrow,” said Clark Fredrickson, a spokesman for eMarketer, a digital media market research firm. “Older generations have less free time, so it takes more time for their habits to change. The younger generation can spend hours a day on one site, get bored of it and switch to something else the next day.”

In a call with investors on Monday morning, Yahoo chief executive Marissa Mayer explained that Yahoo and Tumblr’s differing demographics would give the company’s advertisers access to a valuable new audience. More than 65 percent of Tumblr’s users are under 35, Tumblr chief executive David Karp told The Huffington Post at a Yahoo press conference Monday evening. Yahoo’s users, by contrast, “tend to be slightly older,” said Mayer.

Yet it remains to be seen how loyal those teens and 20-somethings are to the suite of sites they have embraced online -- from Tumblr and Twitter to Facebook and YouTube.

Like other social networking sites, Yahoo and Tumblr will be challenged to stay relevant to millennials, a population with an unquenchable appetite for the next new thing, an instinctive aversion to anything deemed uncool or corporate and the technical know-how to switch services easily. After all, teens and 20-somethings regularly outgrow their offline hangouts, gradually moving from their parents’ basements to bars and other spots. Who’s to say the same won’t happen online?

Karp maintained that Tumblr can hold onto its younger users because of its focus on content, rather than relationships. Mayer, for her part, referred to Tumblr not as a “social network” but as a “media network” during her call with investors Monday.

“I don’t think this has anything to do with, ‘We’re the social network of the moment.’ I think Tumblr is decidedly not social. It’s not about the people in your life, it’s not about relationships -- though it can grow into that -- but really, it’s about the stuff that you love,” Karp told The Huffington Post. “People come to Tumblr to find the stuff that they love, and that’s built on this incredibly creative community that we do everything to support.”

Tumblr helps people to create and distribute content, said Karp, who argued these activities are particularly popular among younger audiences.

“The thing about supporting creativity is that young people have much more boundless creativity,” Karp continued. “People start to give up when they get older. Creativity is a very human thing, but I think it’s something we all experience when we’re young.”

Yet some experts speculate that younger demographics may be more fickle than their parents or older peers. Not only do they have an ever-expanding selection of sites and services from which to choose, but these younger users are “more ambitious in what they explore,” noted Brian Solis, an analyst with Altimeter Group.

Just a few years ago, another mass media company paid top dollar for an up-and-coming social network that, like Tumblr, offered what reporters at the time deemed “a unique 'in' with the preteen, teen, and young-adult population” and that enjoyed “surging popularity with young audiences” -- Myspace.

Yet in the eight years since News Corporation’s 2005 acquisition of Myspace, the percentage of teens on the social media site has dropped dramatically. In 2006, 85 percent of teens who had social media accounts said their Myspace profile was the one they used most often, according to the Pew Research Center. By 2011, only a quarter of teens with social media accounts even had a Myspace profile.

Of course, Myspace’s dwindling popularity isn’t the only evidence that young users are inherently capricious in their online habits. Myspace's own strategic missteps -- and Facebook’s concurrent successes -- also help to account for the mass exodus. Yet Myspace’s foibles highlight how little tolerance millennials have for sites that go astray and the speed with which a flourishing site can find itself abandoned.

Though data are scant on millennials’ evolving usage of specific social media sites, a 2013 survey by investment bank Piper Jaffray suggests younger users have lately been turning away from sites like Facebook and YouTube that were once their preferred destinations. The proportion of teens that named Facebook the “most important social media site” fell 10 percent in the past year to just over 20 percent, according to Piper Jaffray. Tumblr’s importance also dropped slightly: Nearly 10 percent of teens identified Tumblr as the most important social media site in the spring of 2012, while just 5 percent said the same this year.

With so many alternatives from which young users can choose, social networking sites needn’t do anything besides mature to see their popularity plummet.

“If a site gets stale, millennials start to talk about banishing the network,” said Solis. “If a site starts to feel uncool, it is uncool. It has as much to do with the technology as the culture.”

Tumblr faces the real risk of becoming uncool by virtue of its association with Yahoo, noted Solis, and already some teens are threatening to leave the site.

“Karp has to make a strategic effort every day to protect Tumblr’s culture and evolve its culture so millennials feel like it evolves with them,” said Solis.

Karp already seems to be burnishing his anti-establishment street cred. The 26-year-old entrepreneur skipped Yahoo’s investor call on Monday morning to meet with Tumblr’s team, and signed off a blog post announcing Tumblr’s acquisition with a flippant, four-letter salutation: “f*** yeah.”

Published on May 21, 2013 06:10

May 20, 2013

Tumblr's Porn Can Stay, Suggests Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer

Tumblr pornographers, take heart: Yahoo comes in peace.

During an investor call Monday morning announcing Yahoo's $1.1 billion acquisition of media network Tumblr, Yahoo chief executive Marissa Mayer emphasized that Yahoo wants to "let Tumblr be Tumblr," which she suggested would include allowing its numerous X-rated accounts to continue pumping out pornography undisturbed.

Asked by an investor how Yahoo would balance user and advertiser interests with regard to Tumblr content that is "not as brand safe as the rest of Yahoo" -- content that presumably includes posts by sexually explicit Tumblrs such as "Red Hot Porn," "Porn and Weed" and "Secretary Sex" -- Mayer noted that the diversity of Tumblr's content was "exciting" because it allowed Tumblr, and by extension Yahoo, to reach a far wider audience. She explained that carefully targeting ad placement should allay the concerns of marketers who might be skittish about placing their brand alongside explicit content.

"I think the richness and breadth of content available on Tumblr -- even though it may not be as brand safe as what's on our site -- is what's really exciting and allows us to reach even more users," said Mayer, who did not mention pornography as such, but referred obliquely to content that was not "brand safe." "One of the ways to start measuring our growth story here is around traffic and users, and this obviously produces a lot of that. In terms of how to address advertisers' concerns around brand safety, we need to have good tools for targeting."

Conscious of the threat of a mass exodus by Tumblr devotees wary of a corporate overlord, Mayer has repeatedly stressed that Yahoo will allow Tumblr to operate independently, and promised in a blog post about the acquisition that the tech giant would "not screw it up."

Tumblr chief executive David Karp, who was not present on the investor call Monday, wrote in his own blog, "We're not turning purple." Yahoo will keep Tumblr's team intact, noted Mayer, to whom Karp will report directly.

"In terms of the integration between the two sites, we plan to operate and brand and grow Tumblr separately from Yahoo," Mayer said during her call with investors. "We will not have Yahoo branding on the Tumblr site. We want to let Tumblr be Tumblr, and let Yahoo be Yahoo."

Tumblr's guidelines are upfront about the site's tolerance for explicit material, and merely ask users who share "sexual or adult-oriented content" to tag it "NSFW" ("Not Suitable for Work") so people can filter it out of their feed if they so desire. Tumblr also asks content creators not to upload sexually explicit videos using its video-sharing tool ("We're not in the business of profiting from adult-oriented videos and hosting this stuff is f***ing expensive."), but helpfully suggests they could use a service like xHamster.

Peter Shankman, a marketing expert and author of "Nice Companies Finish First," argues that Tumblr's extensive collection of pornography will do little to dissuade advertisers from buying real estate on the site, so long as the media network can offer access to the users and demographics brands seek to reach.

"Advertisers go where the audiences that matter to them are. They always have and they always will," said Shankman. "Yahoo will have the ability to create tools that help prevent some of that [explicit material] from being seen by people who shouldn't see it, and that will benefit advertisers. In the long run, I don't see advertisers running away from this any more than Twitter, or Vine, or Instagram. There's porn. It exists. It's 2013 and it's available anywhere."

But whether Tumblrers like it or not, more advertising will be coming to the blogging service, and Mayer said that Yahoo might feature Tumblr content on its main site. She also discussed the possibility of working with Tumblr bloggers to post ads on their sites, with their permission.

Mayer declined to go into detail about Tumblr's plans for advertising targeted to users' interests -- be it fashion, art or perhaps even pornography -- but noted that the "psychographic profiles on Tumblr are different from what we have on Yahoo, which enriches the user base and makes it that much more interesting to advertisers."

She ended the call by quoting a line from David Fincher's film "The Social Network," which she said summarized Tumblr's advertising evolution and readiness to feature more ads.

"It's like the line from 'The Social Network' movie: 'Why would you monetize it? You don't even know what 'it' is yet,'" said Mayer. "Tumblr is now at the point ... [where] they know what 'it' is, and it makes sense to monetize it in a way that is tasteful and seamless."

During an investor call Monday morning announcing Yahoo's $1.1 billion acquisition of media network Tumblr, Yahoo chief executive Marissa Mayer emphasized that Yahoo wants to "let Tumblr be Tumblr," which she suggested would include allowing its numerous X-rated accounts to continue pumping out pornography undisturbed.

Asked by an investor how Yahoo would balance user and advertiser interests with regard to Tumblr content that is "not as brand safe as the rest of Yahoo" -- content that presumably includes posts by sexually explicit Tumblrs such as "Red Hot Porn," "Porn and Weed" and "Secretary Sex" -- Mayer noted that the diversity of Tumblr's content was "exciting" because it allowed Tumblr, and by extension Yahoo, to reach a far wider audience. She explained that carefully targeting ad placement should allay the concerns of marketers who might be skittish about placing their brand alongside explicit content.

"I think the richness and breadth of content available on Tumblr -- even though it may not be as brand safe as what's on our site -- is what's really exciting and allows us to reach even more users," said Mayer, who did not mention pornography as such, but referred obliquely to content that was not "brand safe." "One of the ways to start measuring our growth story here is around traffic and users, and this obviously produces a lot of that. In terms of how to address advertisers' concerns around brand safety, we need to have good tools for targeting."

Conscious of the threat of a mass exodus by Tumblr devotees wary of a corporate overlord, Mayer has repeatedly stressed that Yahoo will allow Tumblr to operate independently, and promised in a blog post about the acquisition that the tech giant would "not screw it up."

Tumblr chief executive David Karp, who was not present on the investor call Monday, wrote in his own blog, "We're not turning purple." Yahoo will keep Tumblr's team intact, noted Mayer, to whom Karp will report directly.

"In terms of the integration between the two sites, we plan to operate and brand and grow Tumblr separately from Yahoo," Mayer said during her call with investors. "We will not have Yahoo branding on the Tumblr site. We want to let Tumblr be Tumblr, and let Yahoo be Yahoo."

Tumblr's guidelines are upfront about the site's tolerance for explicit material, and merely ask users who share "sexual or adult-oriented content" to tag it "NSFW" ("Not Suitable for Work") so people can filter it out of their feed if they so desire. Tumblr also asks content creators not to upload sexually explicit videos using its video-sharing tool ("We're not in the business of profiting from adult-oriented videos and hosting this stuff is f***ing expensive."), but helpfully suggests they could use a service like xHamster.

Peter Shankman, a marketing expert and author of "Nice Companies Finish First," argues that Tumblr's extensive collection of pornography will do little to dissuade advertisers from buying real estate on the site, so long as the media network can offer access to the users and demographics brands seek to reach.

"Advertisers go where the audiences that matter to them are. They always have and they always will," said Shankman. "Yahoo will have the ability to create tools that help prevent some of that [explicit material] from being seen by people who shouldn't see it, and that will benefit advertisers. In the long run, I don't see advertisers running away from this any more than Twitter, or Vine, or Instagram. There's porn. It exists. It's 2013 and it's available anywhere."

But whether Tumblrers like it or not, more advertising will be coming to the blogging service, and Mayer said that Yahoo might feature Tumblr content on its main site. She also discussed the possibility of working with Tumblr bloggers to post ads on their sites, with their permission.

Mayer declined to go into detail about Tumblr's plans for advertising targeted to users' interests -- be it fashion, art or perhaps even pornography -- but noted that the "psychographic profiles on Tumblr are different from what we have on Yahoo, which enriches the user base and makes it that much more interesting to advertisers."

She ended the call by quoting a line from David Fincher's film "The Social Network," which she said summarized Tumblr's advertising evolution and readiness to feature more ads.

"It's like the line from 'The Social Network' movie: 'Why would you monetize it? You don't even know what 'it' is yet,'" said Mayer. "Tumblr is now at the point ... [where] they know what 'it' is, and it makes sense to monetize it in a way that is tasteful and seamless."

Published on May 20, 2013 08:26

May 17, 2013

Google Glass Privacy Concerns Spurred Lawmakers To Ask Larry Page These 8 Questions

Eight members of congress belonging to a bipartisan "privacy caucus" have penned a letter to Google chief executive Larry Page to request additional information about the privacy implications of Google Glass, Google's yet-to-be released wearable computing device.

Noting that they are "curious whether this new technology could infringe on the privacy of the average American," the representatives laid out eight key questions for Google, including requests for additional information about Glass' ability to track non-users of the device, the use of facial recognition technology and whether Google will revise its privacy policy to take Glass' new capabilities into account.

Glass, which includes a camera that could allow wearers to surreptitiously film and photograph non-users, has sparked privacy fears among some who worry the technology could allow people to secretly record conversations. The product might also eventually make use of facial recognition technology, another privacy concern for some.

Glass also allows wearers to send text messages, check their email, search the web and get directions via the head-mounted gadget, and new apps from CNN, Twitter, Elle and Facebook, among others, are rapidly expanding the capabilities of the device. One developer boasted he'd created an app that allowed Glass wearers to snap pictures just by blinking their eye -- potentially making it easier than ever to record someone without his or her knowledge.

The lawmaker's questions, which Google has until June 14 to answer, include:

Google's track record thus far -- which includes multiple settlements with the FTC over privacy violations -- has undermined lawmakers' trust in the tech giant. They noted in their letter that Google's Street View vehicles had mistakenly collected personal information, including telephone numbers, email addresses and passwords, and asked how the company plans to ensure that Glass users don't commit similar errors.

In the case of Google Glass, bar policy also seems to be influencing public policy: Lawmakers, in outlining the reasons for their concern, cited a Seattle bar owner's decision to ban Glass because of privacy concerns.

The congressional committee's letter was delivered on the second day of Google's annual developer conference, Google I/O. Google's director of product management for Glass, Steve Lee, addressed some of the privacy questions in a panel discussion on Thursday afternoon during the developer conference.

Lee stressed that Google had designed Glass with privacy safeguards in mind, noting that the glass display lights up from both sides when in use so non-users can see when it's active. Users must also speak or tap Glass to record -- so "taking a picture has clear social cues," he said. But while privacy may be Google's intent, at least one developer has already found ways to circumvent those safeguards via the app that he says lets users wink to take a photo.

On Thursday, Lee did not rule out the possibility of including facial recognition capabilities in the device.

“We’ve consistently said that we won’t add new face recognition features to our services unless we have strong privacy protections in place,” he said, according to The New York Times.

Google chairman Eric Schmidt previously expressed concern over the implications of facial recognition systems, noting in a 2011 interview, "I'm very concerned personally about the union of mobile tracking and face recognition."

"We built that technology and we withheld it," Schmidt said of facial recognition at the All Things Digital D9 conference in 2011. "As far as I know, it's the only technology Google has built and, after looking at it, we decided to stop."

Google has repeatedly emphasized that social cues and peoples' "social contract" will help keep Glass wearers in line, a point Glass engineer Charles Mendis brought up again on Thursday.

"If I'm recording you, I have to stare at you -- as a human being. And when someone is staring at you, you have to notice," said Mendis, according to The Verge. "If you walk into a restroom and someone's just looking at you -- I don't know about you but I'm getting the hell out of there."

Read the letter in its entirety below:

Noting that they are "curious whether this new technology could infringe on the privacy of the average American," the representatives laid out eight key questions for Google, including requests for additional information about Glass' ability to track non-users of the device, the use of facial recognition technology and whether Google will revise its privacy policy to take Glass' new capabilities into account.

Glass, which includes a camera that could allow wearers to surreptitiously film and photograph non-users, has sparked privacy fears among some who worry the technology could allow people to secretly record conversations. The product might also eventually make use of facial recognition technology, another privacy concern for some.

Glass also allows wearers to send text messages, check their email, search the web and get directions via the head-mounted gadget, and new apps from CNN, Twitter, Elle and Facebook, among others, are rapidly expanding the capabilities of the device. One developer boasted he'd created an app that allowed Glass wearers to snap pictures just by blinking their eye -- potentially making it easier than ever to record someone without his or her knowledge.

The lawmaker's questions, which Google has until June 14 to answer, include:

[W]e would like to know how Google plans to prevent Google Glass from unintentionally collecting data about the user/non-user without consent?

Would Google place limits on the technology and what type of information it can reveal about another person?

What proactive steps is Google taking to protect the privacy of non-users when Google Glass is in use?

When using Google Glass, is it true that this product would be able to use Facial Recognition Technology to unveil personal information about whomever and even some inanimate objects that the user is viewing?

Given Google Glass's sensory and processing capabilities, has Google considered making any additions or refinements ot its privacy policy?

Google's track record thus far -- which includes multiple settlements with the FTC over privacy violations -- has undermined lawmakers' trust in the tech giant. They noted in their letter that Google's Street View vehicles had mistakenly collected personal information, including telephone numbers, email addresses and passwords, and asked how the company plans to ensure that Glass users don't commit similar errors.

In the case of Google Glass, bar policy also seems to be influencing public policy: Lawmakers, in outlining the reasons for their concern, cited a Seattle bar owner's decision to ban Glass because of privacy concerns.

The congressional committee's letter was delivered on the second day of Google's annual developer conference, Google I/O. Google's director of product management for Glass, Steve Lee, addressed some of the privacy questions in a panel discussion on Thursday afternoon during the developer conference.

Lee stressed that Google had designed Glass with privacy safeguards in mind, noting that the glass display lights up from both sides when in use so non-users can see when it's active. Users must also speak or tap Glass to record -- so "taking a picture has clear social cues," he said. But while privacy may be Google's intent, at least one developer has already found ways to circumvent those safeguards via the app that he says lets users wink to take a photo.

On Thursday, Lee did not rule out the possibility of including facial recognition capabilities in the device.

“We’ve consistently said that we won’t add new face recognition features to our services unless we have strong privacy protections in place,” he said, according to The New York Times.

Google chairman Eric Schmidt previously expressed concern over the implications of facial recognition systems, noting in a 2011 interview, "I'm very concerned personally about the union of mobile tracking and face recognition."

"We built that technology and we withheld it," Schmidt said of facial recognition at the All Things Digital D9 conference in 2011. "As far as I know, it's the only technology Google has built and, after looking at it, we decided to stop."

Google has repeatedly emphasized that social cues and peoples' "social contract" will help keep Glass wearers in line, a point Glass engineer Charles Mendis brought up again on Thursday.

"If I'm recording you, I have to stare at you -- as a human being. And when someone is staring at you, you have to notice," said Mendis, according to The Verge. "If you walk into a restroom and someone's just looking at you -- I don't know about you but I'm getting the hell out of there."

Read the letter in its entirety below:

Congress Inquires About Google Glass by WSJTech

Published on May 17, 2013 08:18

May 15, 2013

The Truth Behind Google's Bizarre Mission to Make Tech 'Go Away'

As a cadre of Google executives took turns touting Google's newest products at a conference in California on Wednesday, they also described how they were working toward a future in which technology would disappear.

That might sound like a bizarre mission for a tech company. Yet they promised that by fading into the background of our lives, technology would become easier to use, more intuitive, more efficient and more anticipatory, even allowing people to speak to Google like it were a person, rather than a piece of software. Google would usher in this new world with tools that would bring web services into every crevice of our lives, from maps that know where we'll go next, to Google Glass, eyewear that puts the Internet mere millimeters away from our eyeballs.

But Google's professed goal of making technology "get out of the way" masks what's truly taking place. By making technology invisible, Google is also making it omnipresent. As software and gadgets become less in-your-face, they also become more pervasive and more influential, as we in turn become more dependent on them, more accepting of their presence in our lives and less critical of them. After all, how can someone scrutinize what they can't see?

When Google says it's working on technology that will go away, it really means the opposite: It's after technology that gets into our heads and takes over.

"The idea of getting technology out of the way is a loose and fast way of saying we want to control more of your life, we just don't want you thinking that we have that level of control and mediation while we exert it," said Evan Selinger, an associate professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology and fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technology. "It's like the perfect black box -- I don't need to think about it, I just hope for the best."

In Wednesday's three-and-a-half hour keynote kicking off Google's three-day developer conference, Google I/O, engineers from multiple parts of the company discussed more than a dozen new offerings. Vic Gundotra, Google's senior vice president of engineering, unveiled a new messaging app that would "finally allow technology to get out of the way." By stitching together texts, photos and video into a single service accessible on any device, Gundotra promised, "technology can just go away and people can focus on what makes them the happiest."

Next, Google software engineer Ahmit Singhal demonstrated how people could speak their queries to Google Now, a Siri-like virtual assistant that anticipates people's questions even before they've been asked. It would allow people to "ask Google like you'd ask a friend," Singhal said, and bring the world closer to omniscient Star Trek-like devices that converse easily.

Google chief executive Larry Page concluded by discussing his dream of "really being able to get computers out of the way and really focused on what people really need."

Or, put more explicitly: Page and company aren't imagining computers that "get out of the way" because they're gone. Instead, they disappear because they've been fused with us.

Consider Google Glass, Google's wearable computing device slated for public release sometime next year. Glass' tagline boasts it's "getting technology out of the way" -- yet it's also a device people are expected to wear at virtually all times, mounted on their foreheads with a screen suspended over their right eye.

That may be modest by comparison with what Google has in store. Google co-founder Sergey Brin offered a vision of just how far the company might go when he mused, in 2005, "Perhaps in the future, we can attach a little version of Google that you just plug into your brain."

Allowing technology -- whether Google Now or Google Glass, Facebook or the iPhone -- to recede into the background of our lives may make us both more reliant on it and less critical of it, ultimately ensuring we're even more susceptible to its suggestions. At the same time, Google gains dedicated customers forking over ever more data -- and dollars -- that it can use to attract the advertisers who still account for the lion's share of its revenues.

A service like Google Now that's automatic, omniscient and omnipresent, whispering to us from our Glass headsets or speaking to us from our smartphones, could ultimately allow Google to access us so easily and intimately, its suggestions could feel like they're coming from our own subconscious. Over time, we might be less inclined to question them, or to unplug Google from our lives.

"The hope is that we begin to live much more mediated by algorithms, but we don't pay attention to them. They become invisible, almost like thoughts in our head," Selinger noted. "It allows a company like this to exert a profound influence, while making it harder to detect the impact of that influence."

When technology "goes away," so too does our ability our ability to analyze it objectively, argues Maggie Jackson, author of Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age.

"If we think that the technology is invisible and seamless, then Google can do anything they want and we lose our ability to be skeptical of what these devices do," said Jackson. "We need to retain the visibility of these gadgets to be skeptical of these gadgets."

In demonstrating the latest version of Google Now, Singhal noted it offered "a new interface -- or as I call it, 'no interface.'" That "no interface" opens up a direct pathway between our minds and Google Now's suggestions, from where to eat to when to leave for work.

But perhaps, with Google as our interface with the world, we'll be able to work with the tech giant to exert control over the version of the world Google delivers up. We could see only what we want to see, and excise the rest. Seemingly a part of our subconscious, Google could offer a kind of algorithmic anti-depressant, where not only avoid bad restaurants and traffic, but we can block unhappy articles, excise annoying people and hear only the songs that make us happy.

Get ready to see the world through rose-colored Google Glasses.

That might sound like a bizarre mission for a tech company. Yet they promised that by fading into the background of our lives, technology would become easier to use, more intuitive, more efficient and more anticipatory, even allowing people to speak to Google like it were a person, rather than a piece of software. Google would usher in this new world with tools that would bring web services into every crevice of our lives, from maps that know where we'll go next, to Google Glass, eyewear that puts the Internet mere millimeters away from our eyeballs.

But Google's professed goal of making technology "get out of the way" masks what's truly taking place. By making technology invisible, Google is also making it omnipresent. As software and gadgets become less in-your-face, they also become more pervasive and more influential, as we in turn become more dependent on them, more accepting of their presence in our lives and less critical of them. After all, how can someone scrutinize what they can't see?

When Google says it's working on technology that will go away, it really means the opposite: It's after technology that gets into our heads and takes over.

"The idea of getting technology out of the way is a loose and fast way of saying we want to control more of your life, we just don't want you thinking that we have that level of control and mediation while we exert it," said Evan Selinger, an associate professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology and fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technology. "It's like the perfect black box -- I don't need to think about it, I just hope for the best."

In Wednesday's three-and-a-half hour keynote kicking off Google's three-day developer conference, Google I/O, engineers from multiple parts of the company discussed more than a dozen new offerings. Vic Gundotra, Google's senior vice president of engineering, unveiled a new messaging app that would "finally allow technology to get out of the way." By stitching together texts, photos and video into a single service accessible on any device, Gundotra promised, "technology can just go away and people can focus on what makes them the happiest."

Next, Google software engineer Ahmit Singhal demonstrated how people could speak their queries to Google Now, a Siri-like virtual assistant that anticipates people's questions even before they've been asked. It would allow people to "ask Google like you'd ask a friend," Singhal said, and bring the world closer to omniscient Star Trek-like devices that converse easily.

Google chief executive Larry Page concluded by discussing his dream of "really being able to get computers out of the way and really focused on what people really need."

Or, put more explicitly: Page and company aren't imagining computers that "get out of the way" because they're gone. Instead, they disappear because they've been fused with us.

Consider Google Glass, Google's wearable computing device slated for public release sometime next year. Glass' tagline boasts it's "getting technology out of the way" -- yet it's also a device people are expected to wear at virtually all times, mounted on their foreheads with a screen suspended over their right eye.

That may be modest by comparison with what Google has in store. Google co-founder Sergey Brin offered a vision of just how far the company might go when he mused, in 2005, "Perhaps in the future, we can attach a little version of Google that you just plug into your brain."

Allowing technology -- whether Google Now or Google Glass, Facebook or the iPhone -- to recede into the background of our lives may make us both more reliant on it and less critical of it, ultimately ensuring we're even more susceptible to its suggestions. At the same time, Google gains dedicated customers forking over ever more data -- and dollars -- that it can use to attract the advertisers who still account for the lion's share of its revenues.

A service like Google Now that's automatic, omniscient and omnipresent, whispering to us from our Glass headsets or speaking to us from our smartphones, could ultimately allow Google to access us so easily and intimately, its suggestions could feel like they're coming from our own subconscious. Over time, we might be less inclined to question them, or to unplug Google from our lives.