Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 2

June 27, 2014

June 24, 2014

June 20, 2014

June 19, 2014

Tinder Tutors Ease The Burden of Picking Out 6 Photos

When the matchmaking app Tinder first launched, everyone claimed it was the easiest, laziest way to date online. There were no quizzes, no essays, no personality tests. Even reading was optional.

But those people were wrong. Tinder is hard. You must upload not one but six (6) different (!) attractive photos. You must select one of those to be the main photo that strangers see and judge. And, because Tinder hasn't realized we now communicate in "yo's," you must think of witty sentences to send to other human beings. Tough. Love.

Michael Raven, the 24-year-old co-founder of a tech-focused public relations company, is an avid Tinder user who feels its online daters' pain. So last Thursday afternoon, while in the Ozone coffee shop in London's hip Shoreditch hood, he decided to launch a Tinder consulting service called TinderUs. Two hours later, TinderUs was live. For a $50 "beta" fee, the website will arrange a live Facebook chat with one of Raven's three 20-something friends, who can help pick your Tinder photos, craft your 500-character bio and refine your come-ons.

TinderUs is one of several Tinder coaching companies that promise to take the headache out of dating on an app that vows to take the headache out of dating. For the uninitiated, Tinder's premise is simple: Is the stranger you see in that photo attractive? Then swipe right ("like!"), and repeat ad infinitum. If you turn the person down, they'll never know it -- but if you like them and they "like" you back, the two of you may begin chatting.

It would seem that very little could go seriously wrong in six curated photos. And yet one week after TinderUs' launch, the Tinder-tutoring service had already booked 45 consultations and paid Raven's rent for the month. It's also acquired a well-worn tagline: "It's the Uber for Tinder," says Raven.

Like previous "gotcha" services that start as a prank, get outsized attention for an absurd premise and then attempt to become real startups, TinderUs began has a "half-joke" that Raven is now taking seriously. Whether anyone else will is another question.

TinderUs is essentially selling the unbiased opinion of another Tinder user. Raven boasts that his consultants are young, in fashion, on Tinder and, somewhat cryptically, "on trend." Look at it this way: Do you have a friend with good judgment? He can probably do the same thing for free.

Raven is not one of TinderUs' dating consultants, all of whom work in the fashion industry (this is a key selling point, Raven emphasizes). Rather, TinderUs' creator is a self-described "tech hustler" and "future tech evangelist" with a "growth hacker background" and an evident affinity for tech buzzwords. His TinderUs Twitter account is a barrage of tweets begging for coverage from almost any journalist who's mentioned TinderUs, Tinder or online dating, while his Twitter profile picture is the go-to headshot of the aspiring tech elite: Raven wearing Google Glass.

Though I haven't personally glimpsed the photo on his Tinder account, TinderUs dating expert Rhyanna Taylor says Raven was "doing it all wrong" before she intervened on a recent ride home from a networking event.

"He's in business and has a PR company, so he put that in there, which is good. As women, we’re attracted to confidence and success in the opposite sex," Taylor explains, offering a taste of the advice she gives to clients. But Raven's pictures focused too much on his social life, says Taylor. "He had a lot of 'night out' photos of him out. He also had a lot of pictures of him and other people for the main image. I was like, 'it has to be you.'"

Taylor's crash course helped inspire TinderUs, and Raven later recruited 21-year-old Taylor and two other friends for his fledgling service. TinderUs charges a $50 fee for each 30- to 60-minute tutorial, and half of that goes to the consultant providing their services.

Raven already imagines he might expand the scope of the Tinder consulting with a premium service that provides fashion advice. The experts could "give advice on clothing, or send links saying, 'You should get this shirt, it would match your style,'" said Raven, adding that TinderUs could take a cut from any sales.

In the past week, Taylor has advised about 23 singles -- half of them male, many of them from the United States and most of them in their mid-20s to early 30s. One client told her she had a nice name and tried to pick her up (she demurred). Some men have come to her hoping to engineer their profiles to "hook up with as many people as they can." But, she said, "I don't feel like I'm going against any of my morals in this work."

Taylor offered up a few cardinal Tinder sins that must be avoided at all costs: Don't make a group photo your main picture ("I've seen it before where someone will say 'yes,' then ask who your friend is and it's awful"). Don't upload too many selfies (instead, your photos should include "a selfie, a social situation, your hobby and interests"). Don't ever include an inspirational quote ("Half the time it looks awful"). Better yet, don't say anything on your profile at all, unless it's certifiably brilliant or you're deliberately trying to weed people out ("You have to list the traits that are important").

On her personal Tinder account, Taylor's main photo is a selfie, but she's left her bio blank. She's too busy juggling her job as a photo shoot coordinator to fill it out.

"I haven't had the time for these kinds of things," she said. "I can't be bothered anymore."

For a small fee, she can always hire someone to help her out.

But those people were wrong. Tinder is hard. You must upload not one but six (6) different (!) attractive photos. You must select one of those to be the main photo that strangers see and judge. And, because Tinder hasn't realized we now communicate in "yo's," you must think of witty sentences to send to other human beings. Tough. Love.

Michael Raven, the 24-year-old co-founder of a tech-focused public relations company, is an avid Tinder user who feels its online daters' pain. So last Thursday afternoon, while in the Ozone coffee shop in London's hip Shoreditch hood, he decided to launch a Tinder consulting service called TinderUs. Two hours later, TinderUs was live. For a $50 "beta" fee, the website will arrange a live Facebook chat with one of Raven's three 20-something friends, who can help pick your Tinder photos, craft your 500-character bio and refine your come-ons.

TinderUs is one of several Tinder coaching companies that promise to take the headache out of dating on an app that vows to take the headache out of dating. For the uninitiated, Tinder's premise is simple: Is the stranger you see in that photo attractive? Then swipe right ("like!"), and repeat ad infinitum. If you turn the person down, they'll never know it -- but if you like them and they "like" you back, the two of you may begin chatting.

It would seem that very little could go seriously wrong in six curated photos. And yet one week after TinderUs' launch, the Tinder-tutoring service had already booked 45 consultations and paid Raven's rent for the month. It's also acquired a well-worn tagline: "It's the Uber for Tinder," says Raven.

Like previous "gotcha" services that start as a prank, get outsized attention for an absurd premise and then attempt to become real startups, TinderUs began has a "half-joke" that Raven is now taking seriously. Whether anyone else will is another question.

TinderUs is essentially selling the unbiased opinion of another Tinder user. Raven boasts that his consultants are young, in fashion, on Tinder and, somewhat cryptically, "on trend." Look at it this way: Do you have a friend with good judgment? He can probably do the same thing for free.

Raven is not one of TinderUs' dating consultants, all of whom work in the fashion industry (this is a key selling point, Raven emphasizes). Rather, TinderUs' creator is a self-described "tech hustler" and "future tech evangelist" with a "growth hacker background" and an evident affinity for tech buzzwords. His TinderUs Twitter account is a barrage of tweets begging for coverage from almost any journalist who's mentioned TinderUs, Tinder or online dating, while his Twitter profile picture is the go-to headshot of the aspiring tech elite: Raven wearing Google Glass.

Though I haven't personally glimpsed the photo on his Tinder account, TinderUs dating expert Rhyanna Taylor says Raven was "doing it all wrong" before she intervened on a recent ride home from a networking event.

"He's in business and has a PR company, so he put that in there, which is good. As women, we’re attracted to confidence and success in the opposite sex," Taylor explains, offering a taste of the advice she gives to clients. But Raven's pictures focused too much on his social life, says Taylor. "He had a lot of 'night out' photos of him out. He also had a lot of pictures of him and other people for the main image. I was like, 'it has to be you.'"

Taylor's crash course helped inspire TinderUs, and Raven later recruited 21-year-old Taylor and two other friends for his fledgling service. TinderUs charges a $50 fee for each 30- to 60-minute tutorial, and half of that goes to the consultant providing their services.

Raven already imagines he might expand the scope of the Tinder consulting with a premium service that provides fashion advice. The experts could "give advice on clothing, or send links saying, 'You should get this shirt, it would match your style,'" said Raven, adding that TinderUs could take a cut from any sales.

In the past week, Taylor has advised about 23 singles -- half of them male, many of them from the United States and most of them in their mid-20s to early 30s. One client told her she had a nice name and tried to pick her up (she demurred). Some men have come to her hoping to engineer their profiles to "hook up with as many people as they can." But, she said, "I don't feel like I'm going against any of my morals in this work."

Taylor offered up a few cardinal Tinder sins that must be avoided at all costs: Don't make a group photo your main picture ("I've seen it before where someone will say 'yes,' then ask who your friend is and it's awful"). Don't upload too many selfies (instead, your photos should include "a selfie, a social situation, your hobby and interests"). Don't ever include an inspirational quote ("Half the time it looks awful"). Better yet, don't say anything on your profile at all, unless it's certifiably brilliant or you're deliberately trying to weed people out ("You have to list the traits that are important").

On her personal Tinder account, Taylor's main photo is a selfie, but she's left her bio blank. She's too busy juggling her job as a photo shoot coordinator to fill it out.

"I haven't had the time for these kinds of things," she said. "I can't be bothered anymore."

For a small fee, she can always hire someone to help her out.

Published on June 19, 2014 12:43

June 17, 2014

Facebook's Snapchat Clone Has A Critical Flaw: You Never Know Who's Screenshotting

Facebook, the social network that needs, loves and wrings many billions of dollars out of our photos, has jealously watched Snapchat attract a greater share of our pictures, over 700 million of which we share daily on the app. To stop the hemorrhaging, Facebook did what Facebook always does: It cloned its competitor. Only it's left out one crucial feature.

Like Snapchat, Facebook's new Slingshot app lets people share photos or videos that disappear shortly after they're consumed. Snapchat lets you have up to ten seconds with a single picture; a "sling" lasts until you've swiped it away. Like Snapchat, Slingshot aims to capture the messy moments. "Photos and videos that don’t stick around forever allow for sharing that’s more expressive, raw and spontaneous," the self-described "Slingshot crew" wrote in a press release.

But unlike Snapchat, Slingshot doesn't warn its photographers if their "expressive, raw and spontaneous" image has been captured for all eternity by a friend who decides to screenshot it. (On smartphones, the native habitat of both Snapchat and Slingshot, it takes approximately half a second to capture whatever appears on the device's screen.)

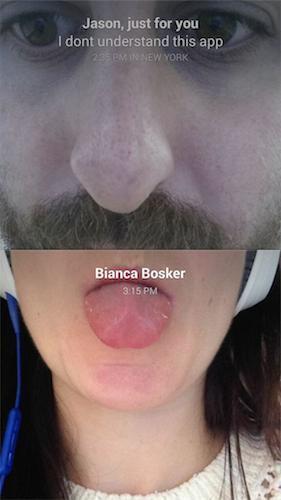

Snapchat warns me that sneaky Jason has captured a picture of my picture.

Snapchat has earned a reputation for its disappearing "snaps," although "ephemeral" messaging is something of a misnomer. Anything shared through the app can be, and often is, permanently documented with a quick screenshot. But realizing that people will mess around only if their images don't stick around, Snapchat's creators have tried to discourage the practice by tattling on anyone who, horror of horrors, takes a picture of someone else's snap. At least in my circle of snapchatters, it's worked: screenshotting a Snapchat message is like reading someone else's text messages when she leaves for the bathroom. It's feasible, but freaky and in poor form.

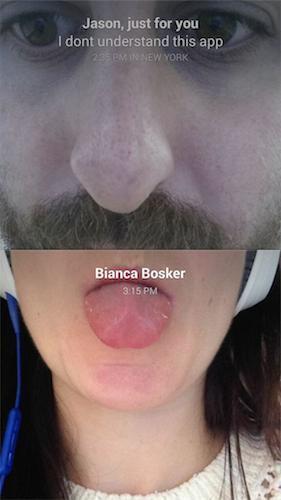

Little did I know Jason decided to screenshot our Slingshot exchange.

Slingshot, in its current version, has no such peer pressure mechanism to guilt screenshot-takers into better behavior. This omission begs the question: Will Facebook's new app ever be able to attract the ugly, impromptu and authentic photos it so hopes to steal away from Snapchat? Or will we worry with every sling that a screenshot -- and blackmail attempt -- is in our future?

It's perhaps little surprise Slingshot's creators have overlooked this small, but important, piece of social engineering that helps defend our privacy. While Snapchat's makers hit it big by discovering the value of disposable content, Facebook has always thrived based on how much it can keep.

Like Snapchat, Facebook's new Slingshot app lets people share photos or videos that disappear shortly after they're consumed. Snapchat lets you have up to ten seconds with a single picture; a "sling" lasts until you've swiped it away. Like Snapchat, Slingshot aims to capture the messy moments. "Photos and videos that don’t stick around forever allow for sharing that’s more expressive, raw and spontaneous," the self-described "Slingshot crew" wrote in a press release.

But unlike Snapchat, Slingshot doesn't warn its photographers if their "expressive, raw and spontaneous" image has been captured for all eternity by a friend who decides to screenshot it. (On smartphones, the native habitat of both Snapchat and Slingshot, it takes approximately half a second to capture whatever appears on the device's screen.)

Snapchat warns me that sneaky Jason has captured a picture of my picture.

Snapchat has earned a reputation for its disappearing "snaps," although "ephemeral" messaging is something of a misnomer. Anything shared through the app can be, and often is, permanently documented with a quick screenshot. But realizing that people will mess around only if their images don't stick around, Snapchat's creators have tried to discourage the practice by tattling on anyone who, horror of horrors, takes a picture of someone else's snap. At least in my circle of snapchatters, it's worked: screenshotting a Snapchat message is like reading someone else's text messages when she leaves for the bathroom. It's feasible, but freaky and in poor form.

Little did I know Jason decided to screenshot our Slingshot exchange.

Slingshot, in its current version, has no such peer pressure mechanism to guilt screenshot-takers into better behavior. This omission begs the question: Will Facebook's new app ever be able to attract the ugly, impromptu and authentic photos it so hopes to steal away from Snapchat? Or will we worry with every sling that a screenshot -- and blackmail attempt -- is in our future?

It's perhaps little surprise Slingshot's creators have overlooked this small, but important, piece of social engineering that helps defend our privacy. While Snapchat's makers hit it big by discovering the value of disposable content, Facebook has always thrived based on how much it can keep.

Published on June 17, 2014 13:26

June 9, 2014

Snapchat Wins Because You Have No Attention Span

What makes Snapchat so addictive, according to the standard refrain, is that it lets people send incriminating pictures guilt-free. Instead of us being self-destructive, it's the messages that self-destruct.

But for many Snapchatters, the appeal of the photo-sharing app lies somewhere else entirely: Snapchat forces focus.

We don't know how long we’ll have to look at the pictures delivered to our phones, but we do know we’ll lose them soon. Once we've opened them, they stick around for seconds, nothing more. Checking Snapchat gets us to eliminate distractions and, for a few moments, commit our undivided attention to a single task. Not even our boyfriends or babies are so compelling.

These ephemeral messages have proved so irresistible that both Apple and Tinder last week unveiled their own Snapchat-style clones. That's in addition to the half-dozen ephemeral messaging apps that have debuted since Snapchat's 2011 founding.

On Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or Secret, we gawk at a never-ending, constantly-updating feed -- a string of updates with a name that, unintentionally but appropriately, calls to mind the troughs of slop shoveled to livestock. The feed is mass content, presented en masse. Snapchat, by contrast, seems like the closest thing the Internet has to artisanal-style “small batch” goods: an imperfect but hand-made creation offered to a few people in a mini serving size that won’t last. The fact that we use Snapchat to show sides of us we shield from other social sites only makes the app more engaging.

I know this because I am a Snapchat hoarder. When I receive a snap, I don’t look at it. I silently congratulate myself on having friends who choose to communicate with me, I put down my phone and I wait. It might be hours, or it could be days. The snaps start piling up. Once I’m alone someplace very quiet, with nothing at all to do, I take out my phone, bring my face very close to its glowing screen and stare at the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it missives that I’ve temporarily been offered. Nothing can pull me away.

I’m not alone in this routine. Danah Boyd, a researcher at New York University and author of It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, made a similar observation in her time studying the tech habits of American teenagers.

“In a digital world where everyone’s flicking through headshots, images, and text without processing any of it, Snapchat asks you to stand still and pay attention to the gift that someone in your network just gave you,” Boyd wrote earlier this year. “Rather than serving as yet-another distraction, Snapchat invites focus.”

For apps like Tinder and Snapchat, the undivided attention their ephemeral messages attract could be a valuable pitch to the advertisers these still-unprofitable startups might choose to woo. Past social media services have focused on quantity, such that he who has the most people (and data) wins. But these services, if they maintain our interest, could compete on slightly different terms. They’ll not only claim more of us -- by adding additional members -- but they’ll also have more of a claim on us. Already, Snapchat, which reportedly turned down a $3 billion acquisition offer from Facebook, is worth an estimated $4 billion.

The traditional Silicon Valley model, perfected by Google, Apple and others, has sought to hang on to us by stockpiling more and more of our information, from music to emails. The success of Snapchat suggests the new prototype could be the opposite: We stay wherever we know the content will vanish.

But for many Snapchatters, the appeal of the photo-sharing app lies somewhere else entirely: Snapchat forces focus.

We don't know how long we’ll have to look at the pictures delivered to our phones, but we do know we’ll lose them soon. Once we've opened them, they stick around for seconds, nothing more. Checking Snapchat gets us to eliminate distractions and, for a few moments, commit our undivided attention to a single task. Not even our boyfriends or babies are so compelling.

These ephemeral messages have proved so irresistible that both Apple and Tinder last week unveiled their own Snapchat-style clones. That's in addition to the half-dozen ephemeral messaging apps that have debuted since Snapchat's 2011 founding.

On Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or Secret, we gawk at a never-ending, constantly-updating feed -- a string of updates with a name that, unintentionally but appropriately, calls to mind the troughs of slop shoveled to livestock. The feed is mass content, presented en masse. Snapchat, by contrast, seems like the closest thing the Internet has to artisanal-style “small batch” goods: an imperfect but hand-made creation offered to a few people in a mini serving size that won’t last. The fact that we use Snapchat to show sides of us we shield from other social sites only makes the app more engaging.

I know this because I am a Snapchat hoarder. When I receive a snap, I don’t look at it. I silently congratulate myself on having friends who choose to communicate with me, I put down my phone and I wait. It might be hours, or it could be days. The snaps start piling up. Once I’m alone someplace very quiet, with nothing at all to do, I take out my phone, bring my face very close to its glowing screen and stare at the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it missives that I’ve temporarily been offered. Nothing can pull me away.

I’m not alone in this routine. Danah Boyd, a researcher at New York University and author of It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, made a similar observation in her time studying the tech habits of American teenagers.

“In a digital world where everyone’s flicking through headshots, images, and text without processing any of it, Snapchat asks you to stand still and pay attention to the gift that someone in your network just gave you,” Boyd wrote earlier this year. “Rather than serving as yet-another distraction, Snapchat invites focus.”

For apps like Tinder and Snapchat, the undivided attention their ephemeral messages attract could be a valuable pitch to the advertisers these still-unprofitable startups might choose to woo. Past social media services have focused on quantity, such that he who has the most people (and data) wins. But these services, if they maintain our interest, could compete on slightly different terms. They’ll not only claim more of us -- by adding additional members -- but they’ll also have more of a claim on us. Already, Snapchat, which reportedly turned down a $3 billion acquisition offer from Facebook, is worth an estimated $4 billion.

The traditional Silicon Valley model, perfected by Google, Apple and others, has sought to hang on to us by stockpiling more and more of our information, from music to emails. The success of Snapchat suggests the new prototype could be the opposite: We stay wherever we know the content will vanish.

Published on June 09, 2014 04:40

June 6, 2014

Should Online Ads Really Offer Binge Drinkers A Booze Discount?

Does the Internet have a duty to protect us from ourselves?

I began to wonder as I attempted to trick Facebook into believing I was single. Hoping to escape the plague of bridal ads that descended after I announced my engagement, I tried to confuse the big data overlords by switching my relationship status and joining every dating site that wasn't obviously a scam. I wanted privacy. Instead, I got ads for matchmaking sites side-by-side with the wedding registries already pitching me in my News Feed.

The nature of these ads -- and the ease with which I’d triggered them -- points to the amoral state of the online marketing apparatus: The Internet makes no moral assessment of what its ads aim to make us do. If I’m a bride, the Internet offers me gowns. If I’m a bride who wants to cheat, it delivers me mates. According to the rules of the Web, the good and righteous path is whichever makes us spend.

But should the Internet really be so blind, especially when it knows us so well? To be fair, the technical limitations of today’s targeting techniques mean the marketers probably failed to realize I was both engaged and on the prowl. “A fairly large amount of people are listed as both male and female by data brokers,” said Brian Kennish, founder of Disconnect, a maker of privacy software. And yet, given the expanding range of digital information that we produce and companies collect, there's every reason to think the data overlords will have more complete portraits of us soon.

This raises a new quandary: Will online advertisements adopt a moral code? As they get more insight into our peccadillos, weak spots, indulgences and addictions, should the Facebooks and Googles of the world limit marketers from pushing products that make us behave badly or cause harm? And who’d decide what “bad” looks like?

Generations of Mad Men have been urging us to suspend good judgment and grab the extra Big Mac. Only this time, it’s different. The intimate ads on the Internet are providing “evermore ways to capitalize on our vulnerabilities by being able to figure out more precisely who we are and what we would be vulnerable to at those contexts and moments,” said Evan Selinger, a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology who studies the intersection of philosophy and tech. Compared with the omnipresent, personalized prompts that appear on our iPhones, yesteryear’s billboards, TV commercials and magazine pages “hit us at more of a generic consumer level.”

The ethical Internet of the future, having realized I was a confused bride trying to cheat, might have banished the OkCupid pitches and instead skewed toward ads for couples counseling. Alternately, if the trend toward indulging all urges continues, advertisers could have pitched me dating sites pixel-by-pixel with promos for books on hiding affairs from a boyfriend. “Getting cold feet because your fiancé’s acting distant?” an ad in my Gmail inbox might read -- Google knowing full well the warmth of my spouse-to-be’s emails had tapered off lately. “Meet these 17 guys near you who like to talk about their feelings.“

As the quality of personal data that data brokers collect increases, advertisers will be pitching us in more customized ways, potentially raising thorny ethical dilemmas with regard to the behavior they aim to induce, while gaining more sway than we might realize -- or want -- over our behavior. It may become harder to tell what was our idea, and what we did because a Fortune 500 company suggested.

If getting clicks and credit cards is the sole mandate, it's easy to imagine ads that might prey on our frailties. Consider a person who regularly researches antidepressants and Googles tips on beating depression. One day, her searches switch to “how to tie a noose.” Will she see banner ads peddling psychiatric help? Or ads for rope? In 2010, Google came under fire for displaying ads for toxic chemicals alongside a suicide discussion forum. "Hydrogen Sulphide. Find medical & lab equipment. Feed your passion on eBay.co.uk!" read one of the promotions, which Google only removed after media coverage. Searching Google for tips on how to commit suicide now automatically serves up the number for a counseling hotline -- though it also delivers ads touting "Best Way To Kill Your Self" and "Painless Quick Ways To Die."

A report released last week by the Federal Trade Commission offered a glimpse at how data brokers are already slicing and dicing populations into niche categories like “Urban Scramble” (primarily low-income African-American and Latino city dwellers) or “Rural Everlasting” (single people over 66 with “low educational attainment and low net worths").

Soon, with help from the data brokers that gather our particulars, marketers may be able to pinpoint people who appear to be compulsive gamblers so they can push ads for casinos. It’s coding to maximize clicks, no matter the moral or personal cost.

The alternative? Programming for the public good. Advertisers get to pick whom they’ll target, but it’s lawmakers and ad networks, like Facebook, Google, Twitter or Apple’s iAds, that set the rules of play. Government officials might step in with their own limits, and there’s ample precedent for curbing how brands can advertise (You won’t see Joe Camel in classrooms). The companies, with their do-no-evil mantras, also could lead the charge. Google could prohibit fast food chains from targeting people who want to diet, or ban Snickers from being pitched to diabetes sufferers. Already, Silicon Valley giants have bans on what marketers can show, no matter what the business would pay. Facebook, for example, only allows dating ads to reach members who've set their relationship status to "single" or left it undefined.

But relying on firms to self-police presumes we trust Google and Facebook to pick what’s good for us and rule on the most moral path. It also puts companies in the position of being our guardians, protecting us from advertising they deem unsavory, unhealthy, unethical or undesirable (a trickier task than it might seem. If a man married to a woman begins downloading dating apps for gay men, would it be right to show him more ads for gay singles sites, or to push marriage counseling?) Do we want Cook, Zuck, Page and Costolo deciding what’s in our best interest, or what's ethical?

Selinger argued such chaperoning would be unwelcome on the Web: “Frankly, because of a certain cyber-libertarian view that we have, if websites became more morally intrusive or morally inquisitive … there would be a big backlash."

And yet these are companies that have spent years positioning themselves as forces for public good. "Facebook was not originally created to be a company. It was built to accomplish a social mission," Mark Zuckerberg declared when the social network filed for its initial public stock offering. Though they might be loathe to turn down business or embrace a potentially controversial moral code, the alternative -- letting our every vulnerability be manipulated -- could be equally unpalatable.

Currently, Facebook and Google's extensive advertising guidelines focus on excluding ads that "provoke" or "offend" their members. But beyond banning ads for illegal substances, there's little explicit concern for our well-being. An even bigger backlash might arrive if people realize Facebook and Google are allowing advertisers to exploit our weaknesses and lead us down harmful paths.

The best way to avoid the moral-question morass may be a path that makes Silicon Valley's giants equally unhappy: Stop getting to know us. Quit looking for more ways to decipher our moods, stop going after our shopping patterns and drop the attempts to decode our psyches. Because if the data brokers and social networks keep gathering more, the questions around what advertising should or shouldn't be allowed to reach us will eventually demand answers. The big data barons might find that ignorance is bliss.

I began to wonder as I attempted to trick Facebook into believing I was single. Hoping to escape the plague of bridal ads that descended after I announced my engagement, I tried to confuse the big data overlords by switching my relationship status and joining every dating site that wasn't obviously a scam. I wanted privacy. Instead, I got ads for matchmaking sites side-by-side with the wedding registries already pitching me in my News Feed.

The nature of these ads -- and the ease with which I’d triggered them -- points to the amoral state of the online marketing apparatus: The Internet makes no moral assessment of what its ads aim to make us do. If I’m a bride, the Internet offers me gowns. If I’m a bride who wants to cheat, it delivers me mates. According to the rules of the Web, the good and righteous path is whichever makes us spend.

But should the Internet really be so blind, especially when it knows us so well? To be fair, the technical limitations of today’s targeting techniques mean the marketers probably failed to realize I was both engaged and on the prowl. “A fairly large amount of people are listed as both male and female by data brokers,” said Brian Kennish, founder of Disconnect, a maker of privacy software. And yet, given the expanding range of digital information that we produce and companies collect, there's every reason to think the data overlords will have more complete portraits of us soon.

This raises a new quandary: Will online advertisements adopt a moral code? As they get more insight into our peccadillos, weak spots, indulgences and addictions, should the Facebooks and Googles of the world limit marketers from pushing products that make us behave badly or cause harm? And who’d decide what “bad” looks like?

Generations of Mad Men have been urging us to suspend good judgment and grab the extra Big Mac. Only this time, it’s different. The intimate ads on the Internet are providing “evermore ways to capitalize on our vulnerabilities by being able to figure out more precisely who we are and what we would be vulnerable to at those contexts and moments,” said Evan Selinger, a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology who studies the intersection of philosophy and tech. Compared with the omnipresent, personalized prompts that appear on our iPhones, yesteryear’s billboards, TV commercials and magazine pages “hit us at more of a generic consumer level.”

The ethical Internet of the future, having realized I was a confused bride trying to cheat, might have banished the OkCupid pitches and instead skewed toward ads for couples counseling. Alternately, if the trend toward indulging all urges continues, advertisers could have pitched me dating sites pixel-by-pixel with promos for books on hiding affairs from a boyfriend. “Getting cold feet because your fiancé’s acting distant?” an ad in my Gmail inbox might read -- Google knowing full well the warmth of my spouse-to-be’s emails had tapered off lately. “Meet these 17 guys near you who like to talk about their feelings.“

As the quality of personal data that data brokers collect increases, advertisers will be pitching us in more customized ways, potentially raising thorny ethical dilemmas with regard to the behavior they aim to induce, while gaining more sway than we might realize -- or want -- over our behavior. It may become harder to tell what was our idea, and what we did because a Fortune 500 company suggested.

If getting clicks and credit cards is the sole mandate, it's easy to imagine ads that might prey on our frailties. Consider a person who regularly researches antidepressants and Googles tips on beating depression. One day, her searches switch to “how to tie a noose.” Will she see banner ads peddling psychiatric help? Or ads for rope? In 2010, Google came under fire for displaying ads for toxic chemicals alongside a suicide discussion forum. "Hydrogen Sulphide. Find medical & lab equipment. Feed your passion on eBay.co.uk!" read one of the promotions, which Google only removed after media coverage. Searching Google for tips on how to commit suicide now automatically serves up the number for a counseling hotline -- though it also delivers ads touting "Best Way To Kill Your Self" and "Painless Quick Ways To Die."

A report released last week by the Federal Trade Commission offered a glimpse at how data brokers are already slicing and dicing populations into niche categories like “Urban Scramble” (primarily low-income African-American and Latino city dwellers) or “Rural Everlasting” (single people over 66 with “low educational attainment and low net worths").

Soon, with help from the data brokers that gather our particulars, marketers may be able to pinpoint people who appear to be compulsive gamblers so they can push ads for casinos. It’s coding to maximize clicks, no matter the moral or personal cost.

The alternative? Programming for the public good. Advertisers get to pick whom they’ll target, but it’s lawmakers and ad networks, like Facebook, Google, Twitter or Apple’s iAds, that set the rules of play. Government officials might step in with their own limits, and there’s ample precedent for curbing how brands can advertise (You won’t see Joe Camel in classrooms). The companies, with their do-no-evil mantras, also could lead the charge. Google could prohibit fast food chains from targeting people who want to diet, or ban Snickers from being pitched to diabetes sufferers. Already, Silicon Valley giants have bans on what marketers can show, no matter what the business would pay. Facebook, for example, only allows dating ads to reach members who've set their relationship status to "single" or left it undefined.

But relying on firms to self-police presumes we trust Google and Facebook to pick what’s good for us and rule on the most moral path. It also puts companies in the position of being our guardians, protecting us from advertising they deem unsavory, unhealthy, unethical or undesirable (a trickier task than it might seem. If a man married to a woman begins downloading dating apps for gay men, would it be right to show him more ads for gay singles sites, or to push marriage counseling?) Do we want Cook, Zuck, Page and Costolo deciding what’s in our best interest, or what's ethical?

Selinger argued such chaperoning would be unwelcome on the Web: “Frankly, because of a certain cyber-libertarian view that we have, if websites became more morally intrusive or morally inquisitive … there would be a big backlash."

And yet these are companies that have spent years positioning themselves as forces for public good. "Facebook was not originally created to be a company. It was built to accomplish a social mission," Mark Zuckerberg declared when the social network filed for its initial public stock offering. Though they might be loathe to turn down business or embrace a potentially controversial moral code, the alternative -- letting our every vulnerability be manipulated -- could be equally unpalatable.

Currently, Facebook and Google's extensive advertising guidelines focus on excluding ads that "provoke" or "offend" their members. But beyond banning ads for illegal substances, there's little explicit concern for our well-being. An even bigger backlash might arrive if people realize Facebook and Google are allowing advertisers to exploit our weaknesses and lead us down harmful paths.

The best way to avoid the moral-question morass may be a path that makes Silicon Valley's giants equally unhappy: Stop getting to know us. Quit looking for more ways to decipher our moods, stop going after our shopping patterns and drop the attempts to decode our psyches. Because if the data brokers and social networks keep gathering more, the questions around what advertising should or shouldn't be allowed to reach us will eventually demand answers. The big data barons might find that ignorance is bliss.

Published on June 06, 2014 04:30