Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 5

February 20, 2014

WhatsApp CEO Is Against Whatever Facebook Is For

Mark Zuckerberg may be Facebook friends with the guys whose company he just bought for $19 billion. But by all indications, Jan Koum, WhatsApp’s CEO and Facebook’s newest board member, just doesn't like Facebook very much.

Koum’s Facebook profile is sparse by comparison with most, with airtight privacy settings that keep strangers from viewing his friends, his photos and his interests. His Facebook profile picture is as blank as they come: It’s a plain, white square.

When asked in a 2012 interview with The Recapp to name his favorite apps other than WhatsApp, Koum listed just three: “On my iPhone 3GS, I use Instagram, Twitter and Touch,” he said.

Facebook, the company that just made Koum a billionaire several times over, is notably absent from that list.

The portrait of Koum that emerges from his interviews and social media posts over the past several years is that of a company founder who jealously guards his privacy and staunchly rejects both data collection and mobile advertising -- values that clash with the core principles on which Facebook is built.

WhatsApp was created around the premise that it should collect as little information about the people using its service as possible. This commitment grew out of Koum’s personal experience with intrusive government surveillance during his childhood in the Ukraine, where he saw friends and dissidents punished for private speech. Though Facebook is certainly no totalitarian regime, the company does track each message that passes through its servers. Koum emphasized how different this model is from WhatsApp's in an interview with Wired just before the acquisition.

“I grew up in a society where everything you did was eavesdropped on, recorded, snitched on," Koum said. "People need to differentiate us from companies like Yahoo! and Facebook that collect your data and have it sitting on their servers. We want to know as little about our users as possible. We don't know your name, your gender… We designed our system to be as anonymous as possible."

Koum has stressed in previous interviews that he seeks to keep his personal life and his business affairs private, while Facebook prefers to have us make our lives an open book. Koum’s Facebook profile could almost pass for a spam account, though it’s the only “Jan Koum” who is friends with WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton, and the account is an administrator of the WhatsApp Facebook group. Koum did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Koum has also been an outspoken critic of online advertising, arguing that it intrudes on what he considers the intimate space of a smartphone and is quickly forgotten. Facebook, of course, draws most of its revenue from brands that pay to reach its more than 1 billion members.

“Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need,” Koum tweeted in 2011, quoting a line from the movie Fight Club.

Koum and Acton have said publicly that they oppose data tracking, another favorite practice of Facebook that undergirds its core business.

"Everything is tied to our rejection of advertising," Koum told El Pais in 2012. “We worked for a long time at Yahoo! and when we left we decided to create something that would have nothing to do with this model where the user is the product -- something that would be a more conscious, private experience."

The difference between the values of Koum and those of Facebook is hardly bad news for the company. If anything, it may be to Facebook’s advantage -- and its members’ -- to have a strong advocate for privacy and anonymity in the upper echelons of the social network. And the timing is especially fortuitous for Facebook, which faces growing competition from apps like Snapchat that lets users, and their messages, disappear.

Whether Koum's principles will be made to disappear within Facebook, however, is another matter entirely.

Koum’s Facebook profile is sparse by comparison with most, with airtight privacy settings that keep strangers from viewing his friends, his photos and his interests. His Facebook profile picture is as blank as they come: It’s a plain, white square.

When asked in a 2012 interview with The Recapp to name his favorite apps other than WhatsApp, Koum listed just three: “On my iPhone 3GS, I use Instagram, Twitter and Touch,” he said.

Facebook, the company that just made Koum a billionaire several times over, is notably absent from that list.

The portrait of Koum that emerges from his interviews and social media posts over the past several years is that of a company founder who jealously guards his privacy and staunchly rejects both data collection and mobile advertising -- values that clash with the core principles on which Facebook is built.

WhatsApp was created around the premise that it should collect as little information about the people using its service as possible. This commitment grew out of Koum’s personal experience with intrusive government surveillance during his childhood in the Ukraine, where he saw friends and dissidents punished for private speech. Though Facebook is certainly no totalitarian regime, the company does track each message that passes through its servers. Koum emphasized how different this model is from WhatsApp's in an interview with Wired just before the acquisition.

“I grew up in a society where everything you did was eavesdropped on, recorded, snitched on," Koum said. "People need to differentiate us from companies like Yahoo! and Facebook that collect your data and have it sitting on their servers. We want to know as little about our users as possible. We don't know your name, your gender… We designed our system to be as anonymous as possible."

Koum has stressed in previous interviews that he seeks to keep his personal life and his business affairs private, while Facebook prefers to have us make our lives an open book. Koum’s Facebook profile could almost pass for a spam account, though it’s the only “Jan Koum” who is friends with WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton, and the account is an administrator of the WhatsApp Facebook group. Koum did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Koum has also been an outspoken critic of online advertising, arguing that it intrudes on what he considers the intimate space of a smartphone and is quickly forgotten. Facebook, of course, draws most of its revenue from brands that pay to reach its more than 1 billion members.

“Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need,” Koum tweeted in 2011, quoting a line from the movie Fight Club.

Koum and Acton have said publicly that they oppose data tracking, another favorite practice of Facebook that undergirds its core business.

"Everything is tied to our rejection of advertising," Koum told El Pais in 2012. “We worked for a long time at Yahoo! and when we left we decided to create something that would have nothing to do with this model where the user is the product -- something that would be a more conscious, private experience."

The difference between the values of Koum and those of Facebook is hardly bad news for the company. If anything, it may be to Facebook’s advantage -- and its members’ -- to have a strong advocate for privacy and anonymity in the upper echelons of the social network. And the timing is especially fortuitous for Facebook, which faces growing competition from apps like Snapchat that lets users, and their messages, disappear.

Whether Koum's principles will be made to disappear within Facebook, however, is another matter entirely.

Published on February 20, 2014 17:19

February 19, 2014

WhatsApp and Facebook's Unite and Conquer Mission

The news that Facebook will spend $19 billion to acquire WhatsApp, a mobile messaging app with more than 450 million users, marks the latest phase in what has emerged as Facebook's defining strategy: The unite and conquer approach to social networking.

Facebook is no longer focused solely on building out Facebook, but is willing to meld itself into whatever shape, service or brand fits your socializing needs at a particular moment of your day. To expand its empire and place itself wherever we are, it'll spend dearly to buy whatever diverse services we value.

For several years now, Facebook has tried to position itself as the go-to messenger for every message we send, publicly or privately, baiting us with features like "chat heads" or the ability to send voice recordings. Buying WhatsApp, which processes 19 billion messages a day, clearly goes a long way toward fulfilling that mission. As soon as all the CEOs and lawyers sign on the doted line, nearly a half-billion people who were messaging off of Facebook will instantly begin routing their chats through Mark Zuckerberg's domain.

But beyond that, Facebook's WhatsApp deal makes it clear that Facebook isn't content to be Facebook. Facebook wants to be the hub for any social interaction you have over the Internet -- alone or in groups, broadcast or whispered, permanent or self-destructing, written or photographed, under the Facebook logo or a different mascot. The WhatsApp acquisition, which follows on Facebook's Instagram buy and its failed bid for Snapchat, suggest more than an effort to find the "next big thing" and cultivate it under Facebook's wing. Facebook wants whatever is the new big thing. (Like Instagram, Facebook confirmed that it will continue to run WhatsApp as a standalone app.)

"If you think about the overall space of sharing and communication, there's not just one thing that people are doing. People want to have the ability to share any kind of content with any audience," Zuckerberg said in an earnings call last month. "There are going to be a lot of different apps that exist, and Facebook has always had the mission of helping people share any kind of content with any audience, but historically we've done that through a single app."

We've thought of Facebook's growing ecosystem of services as revolving around and expanding the core Facebook experience. We're thinking too small. Zuckerberg is dreaming of an even larger universe of services that aren't tied to Facebooking, but communicating -- full stop.

This has obvious advantages for Facebook's business. A broader suite of services means bringing on more users (WhatsApp is particularly popular outside the U.S.), claiming more of people's time and sucking up more of their information, all of which helps Facebook woo advertisers.

But what about for those of us who use the services? It feels harder and harder to escape Facebook's reach while still being social online. While the WhatsApp acquisition will no doubt stoke privacy fears, there's another, less-discussed consequence of this unite and conquer approach: The rapid spread of the Facebook ethos, which values true identities, oversharing and the vague goal of "connecting" above all. Instagram looks a great deal like it did before Facebook acquired the app. But even there, there are subtle changes, like the push to tag friends in photos.

The principles and values that Facebook holds dear are becoming harder to escape as it exports them to whatever new satellite it brings into its orbit. Our online identities are part of the unite and conquer push: Whenever possible, Facebook prefers to combine our online activity to create one comprehensive, exhaustive persona.

Facebook is no longer focused solely on building out Facebook, but is willing to meld itself into whatever shape, service or brand fits your socializing needs at a particular moment of your day. To expand its empire and place itself wherever we are, it'll spend dearly to buy whatever diverse services we value.

For several years now, Facebook has tried to position itself as the go-to messenger for every message we send, publicly or privately, baiting us with features like "chat heads" or the ability to send voice recordings. Buying WhatsApp, which processes 19 billion messages a day, clearly goes a long way toward fulfilling that mission. As soon as all the CEOs and lawyers sign on the doted line, nearly a half-billion people who were messaging off of Facebook will instantly begin routing their chats through Mark Zuckerberg's domain.

But beyond that, Facebook's WhatsApp deal makes it clear that Facebook isn't content to be Facebook. Facebook wants to be the hub for any social interaction you have over the Internet -- alone or in groups, broadcast or whispered, permanent or self-destructing, written or photographed, under the Facebook logo or a different mascot. The WhatsApp acquisition, which follows on Facebook's Instagram buy and its failed bid for Snapchat, suggest more than an effort to find the "next big thing" and cultivate it under Facebook's wing. Facebook wants whatever is the new big thing. (Like Instagram, Facebook confirmed that it will continue to run WhatsApp as a standalone app.)

"If you think about the overall space of sharing and communication, there's not just one thing that people are doing. People want to have the ability to share any kind of content with any audience," Zuckerberg said in an earnings call last month. "There are going to be a lot of different apps that exist, and Facebook has always had the mission of helping people share any kind of content with any audience, but historically we've done that through a single app."

We've thought of Facebook's growing ecosystem of services as revolving around and expanding the core Facebook experience. We're thinking too small. Zuckerberg is dreaming of an even larger universe of services that aren't tied to Facebooking, but communicating -- full stop.

This has obvious advantages for Facebook's business. A broader suite of services means bringing on more users (WhatsApp is particularly popular outside the U.S.), claiming more of people's time and sucking up more of their information, all of which helps Facebook woo advertisers.

But what about for those of us who use the services? It feels harder and harder to escape Facebook's reach while still being social online. While the WhatsApp acquisition will no doubt stoke privacy fears, there's another, less-discussed consequence of this unite and conquer approach: The rapid spread of the Facebook ethos, which values true identities, oversharing and the vague goal of "connecting" above all. Instagram looks a great deal like it did before Facebook acquired the app. But even there, there are subtle changes, like the push to tag friends in photos.

The principles and values that Facebook holds dear are becoming harder to escape as it exports them to whatever new satellite it brings into its orbit. Our online identities are part of the unite and conquer push: Whenever possible, Facebook prefers to combine our online activity to create one comprehensive, exhaustive persona.

Published on February 19, 2014 17:24

February 11, 2014

True Love Is Sharing A Facebook Profile

It used to be that “going steady” meant getting pinned. Boy meets girl, boy gives girl fraternity pledge pin, and other boys back off. Eventually, pinning gave way to “making it Facebook Official,” then replaced by the nebulous practice of spreading the news by word of mouth. No trinkets, no status updates and no real clarity.

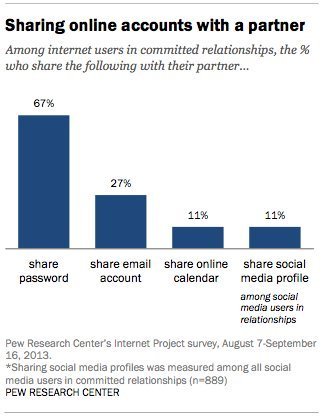

Yet according to the Pew Research Center's latest survey, several new symbols of romantic devotion have taken hold among couples: the shared password, the joint email address and the fused social media profile.

Along with having The Talk and meeting parents, creating joint accounts and passing passwords have apparently become relationship benchmarks. Moving inboxes together is the new moving in together.

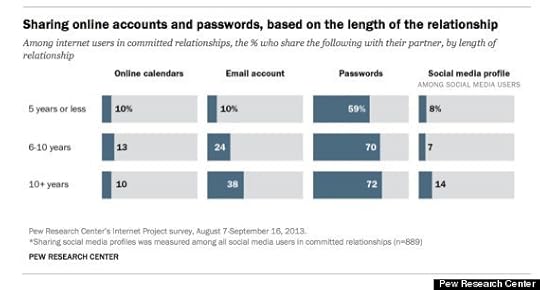

“Adults who are long-partnered use technology in their relationship, but are more likely to use some of it together—by sharing email addresses and social media profiles as a couple,” reads the Pew report, which based its findings on a survey of over 2,000 American adults. When it comes to a couple's likelihood of creating a single email account and social media profile, “the duration of the relationship is a more important factor than the age of the individuals,” Pew's report adds.

Among partners who’ve been together fewer than ten years, 8 percent share a social networking account, while 14 percent of couples together over ten years have a shared profile. Couples aren't necessarily shutting down their personal accounts in favor of a connected one, but might be "moving in" to a third, shared profile as part of a larger nesting process that goes along with getting serious, like buying furniture or a puppy together. The frequency with which couples share social media profiles is virtually identical for different age demographics, Pew found. (Ten percent of people 18 to 29 years old have a social media account with their partner; 11 percent of people over 65 do so, too.)

For single people, this may now mean an entirely new relationship threshold to worry about: Stop asking when you’ll meet her mother, and start wondering when you’ll share a Facebook page.

A similar pattern holds true for email, Pew found. Ten percent of couples who’ve been together five years or fewer use the same email account, a figure that jumps to 24 percent for couples together six to 10 years, and climbs to 38 percent for couples who’ve been together over a decade. In this case, older couples are more likely than their younger counterparts to agree to a single inbox.

Two-thirds of all couples have exchanged passwords to their online accounts, a ritual that’s almost equally common among millennials, 30-somethings and the middle-aged.

These fused online identities aren’t necessarily as romantic as penning poetry or offering big rocks, however. Sharing passwords can be purely practical, allowing couples to get two Netflix accounts for the price of one or enjoy all the perks of Amazon Prime without ponying up another $79. For jealous lovers, exchanging passwords can help them more easily and openly spy on each others’ correspondence. Some spouses and partners have also created joint profiles on online dating sites in the hopes of soliciting a third individual for threesomes. And others in longer relationships might have, out of convenience, set up a single account during their initial forays onto Instagram or Hotmail, rather than later switching to a shared account as a grand gesture of their love.

“It’s about timing,” wrote Amanda Lenhart, lead author of the Pew report, in an emailed statement. “[I]n many cases these couples were together when they first started using the technology and began using it as unit, while those who have been in a relationship for a shorter period of time were still independent actors when they first set up their accounts.”

But there are certainly couples for whom the combined virtual identities function as a pin or a ring. The single profile offers a way to broadcast their adoration for one another, no matter how saccharine it might appear to those who see it. What to them seems a sweet gesture of their affection can look to the rest of the world like one very long, very unavoidable form of digital PDA.

“Dave and I are one of those unique couples who have always been really in tune with each other," a woman who shares an Instagram account with her husband told Mashable last year. “We've been inseparable since 1991 and we know each other inside out. Other couples might want to keep their singular voice, but our identity has always been about being together."

A relationship therapist interviewed by Mashable wasn’t as smitten by this joint-account gesture.

“Psychologically, when couples share social media accounts, it more likely than not is a sign of codependency or insecurity,” Suzana Flores, the therapist, told Mashable. “It’s almost like the couple is ... too enmeshed."

Yet according to the Pew Research Center's latest survey, several new symbols of romantic devotion have taken hold among couples: the shared password, the joint email address and the fused social media profile.

Along with having The Talk and meeting parents, creating joint accounts and passing passwords have apparently become relationship benchmarks. Moving inboxes together is the new moving in together.

“Adults who are long-partnered use technology in their relationship, but are more likely to use some of it together—by sharing email addresses and social media profiles as a couple,” reads the Pew report, which based its findings on a survey of over 2,000 American adults. When it comes to a couple's likelihood of creating a single email account and social media profile, “the duration of the relationship is a more important factor than the age of the individuals,” Pew's report adds.

Among partners who’ve been together fewer than ten years, 8 percent share a social networking account, while 14 percent of couples together over ten years have a shared profile. Couples aren't necessarily shutting down their personal accounts in favor of a connected one, but might be "moving in" to a third, shared profile as part of a larger nesting process that goes along with getting serious, like buying furniture or a puppy together. The frequency with which couples share social media profiles is virtually identical for different age demographics, Pew found. (Ten percent of people 18 to 29 years old have a social media account with their partner; 11 percent of people over 65 do so, too.)

For single people, this may now mean an entirely new relationship threshold to worry about: Stop asking when you’ll meet her mother, and start wondering when you’ll share a Facebook page.

A similar pattern holds true for email, Pew found. Ten percent of couples who’ve been together five years or fewer use the same email account, a figure that jumps to 24 percent for couples together six to 10 years, and climbs to 38 percent for couples who’ve been together over a decade. In this case, older couples are more likely than their younger counterparts to agree to a single inbox.

Two-thirds of all couples have exchanged passwords to their online accounts, a ritual that’s almost equally common among millennials, 30-somethings and the middle-aged.

These fused online identities aren’t necessarily as romantic as penning poetry or offering big rocks, however. Sharing passwords can be purely practical, allowing couples to get two Netflix accounts for the price of one or enjoy all the perks of Amazon Prime without ponying up another $79. For jealous lovers, exchanging passwords can help them more easily and openly spy on each others’ correspondence. Some spouses and partners have also created joint profiles on online dating sites in the hopes of soliciting a third individual for threesomes. And others in longer relationships might have, out of convenience, set up a single account during their initial forays onto Instagram or Hotmail, rather than later switching to a shared account as a grand gesture of their love.

“It’s about timing,” wrote Amanda Lenhart, lead author of the Pew report, in an emailed statement. “[I]n many cases these couples were together when they first started using the technology and began using it as unit, while those who have been in a relationship for a shorter period of time were still independent actors when they first set up their accounts.”

But there are certainly couples for whom the combined virtual identities function as a pin or a ring. The single profile offers a way to broadcast their adoration for one another, no matter how saccharine it might appear to those who see it. What to them seems a sweet gesture of their affection can look to the rest of the world like one very long, very unavoidable form of digital PDA.

“Dave and I are one of those unique couples who have always been really in tune with each other," a woman who shares an Instagram account with her husband told Mashable last year. “We've been inseparable since 1991 and we know each other inside out. Other couples might want to keep their singular voice, but our identity has always been about being together."

A relationship therapist interviewed by Mashable wasn’t as smitten by this joint-account gesture.

“Psychologically, when couples share social media accounts, it more likely than not is a sign of codependency or insecurity,” Suzana Flores, the therapist, told Mashable. “It’s almost like the couple is ... too enmeshed."

Published on February 11, 2014 12:20

February 10, 2014

Nice To Meet You. I've Already Taken Your Picture

In the eight days ending on Friday, I took 5,940 photos of me eating cereal, getting crushed on the subway, cutting my fingernails, and checking my iPhone. I have photographed myself 523 times while writing this story. And in the time it takes you to read this, I could easily have snapped another dozen of you. Probably without you noticing.

I owe it all to my favorite new accessory: a Triscuit-sized, wearable camera called the Narrative Clip that automatically snaps a photo every 30 seconds. I’ve used the camera clipped to my clothes, strapped on my purse, fastened to a dog and propped up on my desk, where it’s watching me now through a pinhead-shaped lens in the corner of its white plastic frame. That black spot is the only vague hint it’s something more sinister than a pretty pin. From its rotating perch, my personal paparazzo has followed me to brunch, the office, dinners, two concerts, a baby shower, a television appearance, and even, by accident, to the bathroom. It stops shooting only when I slip it in my pocket.

If you’re anything like my friends, whose distaste for my surveillance binge I've captured on camera in frowns and furrowed brows, what you’re really wondering by now is, “Why?” Why be a creepy Tracking Tom who photographs strangers twice a minute? And why bother capturing such scintillating still-lives as the inside of a fridge?

Yet if you’re anything like the nearly 3,000 individuals who funded the Narrative Clip’s Kickstarter campaign, or the thousands more who’ve embraced “lifelogging” with tools like the FitBit, the appeal is obvious. Our memories are scattered, untrustworthy little things constantly misplacing important details from our lives. Computers, on the other hand, boast infinite brainpower and a knack for tracking everything we do -- one that gets better by the day. While people decry Big Brother-esque scrutiny amid disclosures of NSA spying and the spread of security cameras, the Narrative Clip taps into a related, but oddly contradictory, impulse: a zeal for subjecting ourselves to ceaseless surveillance, provided we’re in charge of the data.

The camera indulges a longstanding desire for technology-enabled total recall, an obsession that’s transforming the act of forgetting from an inevitable outcome into something that requires an active choice. Yet even more than expanding my memories, I found my own camera companion was actually creating new ones.

The Narrative Clip camera is scheduled to ship in March and costs $279 to purchase.

Martin Källström, the co-founder of Narrative, says his own glitchy cerebral cortex inspired the mini-camera. While birthdays and holidays are photographed (and thus remembered) in copious detail, he was distressed by how quickly the mundane events of everyday life, like breakfast with his kids, slipped from memory. He wanted something capable of “gathering as much data as possible” in a way that was “very, very effortless,” Källström told me in a 2012 interview. And thus was born the Narrative Clip, which claims to satisfy “the dream of a photographic memory.”

“Sadly, I’ve lost both my parents, and I really feel that the time I spent with them is fading, and the memories of them are fading much more quickly than I’d like them to,” Källström said. “What is left are the stories that we have always told each other … and the photos that have ended up in albums. The in-betweens are getting lost more and more.”

The early computer pioneer Vannevar Bush shared a similar concern. In his influential 1945 essay “As We May Think,” Bush made a case for augmenting the human mind by creating an all-remembering storage device Bush dubbed the “memex.” A person would create this “enlarged intimate supplement to his memory” by feeding it books, letters, records and the images captured by an unusual camera. Bush predicted the “camera hound of the future” would supplement memory by attaching to his forehead a camera only “a little larger than a walnut.” He was off only by the size: Narrative Clip is smaller than a walnut, though its creators do suggest strapping it to a headband. (This isn’t fantastic news for anyone who cares about their privacy. Like Google Glass, the Narrative Clip also enables stranger-on-stranger surveillance that, short of banning the technology or strictly limiting its uses, could be impossible to suppress as the device's popularity grows.)

At the end of a week, my Narrative Clip had assembled a photographic “memex” that offers the closest thing yet to a time machine. The Narrative app divvies my photos into albums that transport me to a specific time -- my car ride Saturday, Feb. 1 at 12:46 p.m., for example -- for a taste of who I was and what I was doing at that precise moment in the past. None of my Clip snaps have made it to Instagram, nor have I bothered to weed out the bad ones. The pleasure, as Källström envisioned, comes from replaying a stop-action animation of an unremarkable, totally average day. Looking through my albums, the only remarkable thing that emerges is how much I’d give to see the same kind of photos taken during an average day when I was 4, or 16, or even 26.

An image of the author's sink, captured by the Narrative Clip.

But then there were the things I couldn’t place, like the bizarre looks from unknown individuals, or the bookshelf in my apartment that, seen from a new angle, suddenly looked sadly shabby.

The Narrative Clip didn’t just let me “relive life’s special and everyday moments,” as the ad copy on the camera’s sleek box had promised. When I scrolled through the thousands of photos it captured, I had the feeling of discovering entirely new dimensions to an experience I thought I knew. It both jogged my memory and fiddled with it.

I’m crushed to discover someone sneering at me as I passed by her, leaving me obsessed trying to explain this mystery enemy I ticked off for unknown reasons. A picture of me gesticulating while I chat with a friend caught him looking miffed at our conversation. But since the Narrative can only tell me that we were talking -- not what we were talking about -- I can’t remember if I said something that might have irked him. Should I apologize? For what? Was it an awkward remark, or just the shutter's awkward timing? And then there’s watching my bad habits replayed over and over and over during the hundreds of photos during my workday -- the nibbling, the lip-biting, the squinting, the snacking. Cruel and unusual punishment indeed.

The Narrative Clip captures the author at work.

The Narrative Clip lets me see my life through someone else's eyes -- or in this case, the unfocused and impartial eye of a machine. Its blunt record can expose our faults. As Bush wrote, “Presumably man's spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems."

And yet, as any historian knows, reconstructing our past requires interpretation along with the facts. Even if an all-capturing camera provides us with a photo documentary of our lives, we still get final say when inventing the story that goes with it.

That picture of my friend, for instance. I just remembered what was happening: He was taken aback by the brilliant, inspired and utterly earth-shattering observation I'd made that same moment.

At least the picture doesn't say otherwise.

I owe it all to my favorite new accessory: a Triscuit-sized, wearable camera called the Narrative Clip that automatically snaps a photo every 30 seconds. I’ve used the camera clipped to my clothes, strapped on my purse, fastened to a dog and propped up on my desk, where it’s watching me now through a pinhead-shaped lens in the corner of its white plastic frame. That black spot is the only vague hint it’s something more sinister than a pretty pin. From its rotating perch, my personal paparazzo has followed me to brunch, the office, dinners, two concerts, a baby shower, a television appearance, and even, by accident, to the bathroom. It stops shooting only when I slip it in my pocket.

If you’re anything like my friends, whose distaste for my surveillance binge I've captured on camera in frowns and furrowed brows, what you’re really wondering by now is, “Why?” Why be a creepy Tracking Tom who photographs strangers twice a minute? And why bother capturing such scintillating still-lives as the inside of a fridge?

Yet if you’re anything like the nearly 3,000 individuals who funded the Narrative Clip’s Kickstarter campaign, or the thousands more who’ve embraced “lifelogging” with tools like the FitBit, the appeal is obvious. Our memories are scattered, untrustworthy little things constantly misplacing important details from our lives. Computers, on the other hand, boast infinite brainpower and a knack for tracking everything we do -- one that gets better by the day. While people decry Big Brother-esque scrutiny amid disclosures of NSA spying and the spread of security cameras, the Narrative Clip taps into a related, but oddly contradictory, impulse: a zeal for subjecting ourselves to ceaseless surveillance, provided we’re in charge of the data.

The camera indulges a longstanding desire for technology-enabled total recall, an obsession that’s transforming the act of forgetting from an inevitable outcome into something that requires an active choice. Yet even more than expanding my memories, I found my own camera companion was actually creating new ones.

The Narrative Clip camera is scheduled to ship in March and costs $279 to purchase.

Martin Källström, the co-founder of Narrative, says his own glitchy cerebral cortex inspired the mini-camera. While birthdays and holidays are photographed (and thus remembered) in copious detail, he was distressed by how quickly the mundane events of everyday life, like breakfast with his kids, slipped from memory. He wanted something capable of “gathering as much data as possible” in a way that was “very, very effortless,” Källström told me in a 2012 interview. And thus was born the Narrative Clip, which claims to satisfy “the dream of a photographic memory.”

“Sadly, I’ve lost both my parents, and I really feel that the time I spent with them is fading, and the memories of them are fading much more quickly than I’d like them to,” Källström said. “What is left are the stories that we have always told each other … and the photos that have ended up in albums. The in-betweens are getting lost more and more.”

The early computer pioneer Vannevar Bush shared a similar concern. In his influential 1945 essay “As We May Think,” Bush made a case for augmenting the human mind by creating an all-remembering storage device Bush dubbed the “memex.” A person would create this “enlarged intimate supplement to his memory” by feeding it books, letters, records and the images captured by an unusual camera. Bush predicted the “camera hound of the future” would supplement memory by attaching to his forehead a camera only “a little larger than a walnut.” He was off only by the size: Narrative Clip is smaller than a walnut, though its creators do suggest strapping it to a headband. (This isn’t fantastic news for anyone who cares about their privacy. Like Google Glass, the Narrative Clip also enables stranger-on-stranger surveillance that, short of banning the technology or strictly limiting its uses, could be impossible to suppress as the device's popularity grows.)

At the end of a week, my Narrative Clip had assembled a photographic “memex” that offers the closest thing yet to a time machine. The Narrative app divvies my photos into albums that transport me to a specific time -- my car ride Saturday, Feb. 1 at 12:46 p.m., for example -- for a taste of who I was and what I was doing at that precise moment in the past. None of my Clip snaps have made it to Instagram, nor have I bothered to weed out the bad ones. The pleasure, as Källström envisioned, comes from replaying a stop-action animation of an unremarkable, totally average day. Looking through my albums, the only remarkable thing that emerges is how much I’d give to see the same kind of photos taken during an average day when I was 4, or 16, or even 26.

An image of the author's sink, captured by the Narrative Clip.

But then there were the things I couldn’t place, like the bizarre looks from unknown individuals, or the bookshelf in my apartment that, seen from a new angle, suddenly looked sadly shabby.

The Narrative Clip didn’t just let me “relive life’s special and everyday moments,” as the ad copy on the camera’s sleek box had promised. When I scrolled through the thousands of photos it captured, I had the feeling of discovering entirely new dimensions to an experience I thought I knew. It both jogged my memory and fiddled with it.

I’m crushed to discover someone sneering at me as I passed by her, leaving me obsessed trying to explain this mystery enemy I ticked off for unknown reasons. A picture of me gesticulating while I chat with a friend caught him looking miffed at our conversation. But since the Narrative can only tell me that we were talking -- not what we were talking about -- I can’t remember if I said something that might have irked him. Should I apologize? For what? Was it an awkward remark, or just the shutter's awkward timing? And then there’s watching my bad habits replayed over and over and over during the hundreds of photos during my workday -- the nibbling, the lip-biting, the squinting, the snacking. Cruel and unusual punishment indeed.

The Narrative Clip captures the author at work.

The Narrative Clip lets me see my life through someone else's eyes -- or in this case, the unfocused and impartial eye of a machine. Its blunt record can expose our faults. As Bush wrote, “Presumably man's spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems."

And yet, as any historian knows, reconstructing our past requires interpretation along with the facts. Even if an all-capturing camera provides us with a photo documentary of our lives, we still get final say when inventing the story that goes with it.

That picture of my friend, for instance. I just remembered what was happening: He was taken aback by the brilliant, inspired and utterly earth-shattering observation I'd made that same moment.

At least the picture doesn't say otherwise.

Published on February 10, 2014 10:55

February 5, 2014

Twitter's Plan To Woo Regular People

Twitter CEO Dick Costolo kicked off the company's inaugural earnings call Wednesday by listing four adjectives that, to him, sum up the service's most winsome qualities: "public," "real-time," "conversational" and "widely distributed."

"Friendly" didn't make the cut.

Twitter does a lot of things well, but being easy to use and intuitive isn't among them. With Twitter's total number of active users hovering around 240 million -- about half as many as Costolo had promised by now -- the CEO dedicated much of his chat with investors and analysts to explaining how Twitter plans to attract all the regular people still unconvinced by its 140-character format.

"We have a massive global awareness of Twitter. And we have to bridge the gap between awareness and deep engagement with Twitter on the platform," said Costolo. He maintained that that Twitter's growth so far has been mostly viral and word of mouth -- or just "something that happened to us."

The strategy Costolo outlined rests on the assumption that more friends, more pictures, more chatting and more order will bring more users to Twitter.

So what does that mean, exactly?

Many fervent Twitter fans will tell you it's taken them years to build the perfect feed and, like fastidious artists, they're constantly improving it by making tiny tweaks to whom they follow. People new to the service don't necessarily have that patience, and Twitter recognizes it has to make the service immediately appealing to people when they first sign up. To do so, Costolo teased Twitter's plans to simplify the registration process and to help people connect with friends already on Twitter -- a key step he said boosts engagement from the very first day, and corresponds to higher growth later on.

"It's very much about making it easier for people who first come to the platform to get it more quickly," Costolo said. "It's not just 'get it in the first weeks and months on Twitter.' It's, 'get in the first moments, the first day on Twitter.'"

Costolo maintained that transforming Twitter into a "more visually engaging medium" -- think more pictures and video in the feed -- will make it "more accessible to broader audiences." Already, Twitter has made a move in this direction by launching services like Vine, a six-second video sharing platform, and by redesigning the Twitter app to show images in the stream itself.

The third part of Costolo's grand plan focuses on a topic that's commanded Facebook's attention of late, too: messaging. He promised the company will work to "make Twitter a better tool for conversations both public and private," adding that updates to Twitter's design had increased the number of direct messages by 25 percent in the most recent quarter.

And finally, Costolo teased a change he argued could "make Twitter easier to use and understand for everyone," albeit one that would be a departure from its traditional architecture. The current Twitter organizes tweets chronologically. But Costolo's new-and-improved, easy-to-use Twitter would seek to organize content "along topical and relevance lines," the chief executive said.

He cited last quarter's increase in direct messaging and 35 percent growth in retweets and "favorites" as evidence that these four planned revamps to Twitter's design will win over all the normal people still befuddled by Twitter's "RTs," "MTs," "HTs" and "#"s.

"We don’t need to change anything about the characters of our platform," said Costolo. "We have to make Twitter a better Twitter."

"Friendly" didn't make the cut.

Twitter does a lot of things well, but being easy to use and intuitive isn't among them. With Twitter's total number of active users hovering around 240 million -- about half as many as Costolo had promised by now -- the CEO dedicated much of his chat with investors and analysts to explaining how Twitter plans to attract all the regular people still unconvinced by its 140-character format.

"We have a massive global awareness of Twitter. And we have to bridge the gap between awareness and deep engagement with Twitter on the platform," said Costolo. He maintained that that Twitter's growth so far has been mostly viral and word of mouth -- or just "something that happened to us."

The strategy Costolo outlined rests on the assumption that more friends, more pictures, more chatting and more order will bring more users to Twitter.

So what does that mean, exactly?

Many fervent Twitter fans will tell you it's taken them years to build the perfect feed and, like fastidious artists, they're constantly improving it by making tiny tweaks to whom they follow. People new to the service don't necessarily have that patience, and Twitter recognizes it has to make the service immediately appealing to people when they first sign up. To do so, Costolo teased Twitter's plans to simplify the registration process and to help people connect with friends already on Twitter -- a key step he said boosts engagement from the very first day, and corresponds to higher growth later on.

"It's very much about making it easier for people who first come to the platform to get it more quickly," Costolo said. "It's not just 'get it in the first weeks and months on Twitter.' It's, 'get in the first moments, the first day on Twitter.'"

Costolo maintained that transforming Twitter into a "more visually engaging medium" -- think more pictures and video in the feed -- will make it "more accessible to broader audiences." Already, Twitter has made a move in this direction by launching services like Vine, a six-second video sharing platform, and by redesigning the Twitter app to show images in the stream itself.

The third part of Costolo's grand plan focuses on a topic that's commanded Facebook's attention of late, too: messaging. He promised the company will work to "make Twitter a better tool for conversations both public and private," adding that updates to Twitter's design had increased the number of direct messages by 25 percent in the most recent quarter.

And finally, Costolo teased a change he argued could "make Twitter easier to use and understand for everyone," albeit one that would be a departure from its traditional architecture. The current Twitter organizes tweets chronologically. But Costolo's new-and-improved, easy-to-use Twitter would seek to organize content "along topical and relevance lines," the chief executive said.

He cited last quarter's increase in direct messaging and 35 percent growth in retweets and "favorites" as evidence that these four planned revamps to Twitter's design will win over all the normal people still befuddled by Twitter's "RTs," "MTs," "HTs" and "#"s.

"We don’t need to change anything about the characters of our platform," said Costolo. "We have to make Twitter a better Twitter."

Published on February 05, 2014 16:35

February 4, 2014

The Oversharers Are Over Sharing: 10 Years On, The Facebook Generation Is Covering Up

In honor of Facebook's 10th anniversary Tuesday, which falls just a few months before my own 10th Facebook anniversary, I went rooting through the decade's worth of stuff I've forked over to Mark Zuckerberg and co.

Huge mistake. Nothing could have prepared me for the heart palpitations. I tried to tilt my screen away from my coworkers to shield them from the hundreds of photos I had, in some four-year-long lapse of judgment following high school, allowed posted of me -- sticking out my tongue, flopping on couches, stuffing my face with food, wearing too-short tops, strenuously trying to look effortlessly glamorous, attempting to show I was having an amaaaaazing time (whoooo!!!) and, all in all, trying much, much too hard (WHOO WHOOOO!!!!). There was an album titled -- I'm cringing even now -- "Bro'ing and Ho'ing out - Spring Break '07."

I sent friends a volley of texts demanding to know to why they hadn't confiscated my computer when I'd first shown an inclination for photographic self-destruction. "omg I know," my roommate from junior year of college wrote back. "also -- TEN YEARS AHH."

Allow me to translate. Flipping through Facebook, awkward as it was, brought to mind something that hadn't occurred to us in years: Facebook used to be fun. Somewhere along the way, it got boring. Or, more accurately, we did.

As I scrolled through my profile to the present day, the unspeakable stuff began to disappear, replaced by retouched snaps from weddings and bland party pictures from tech conferences.

My generation, the first on Facebook, was supposed to grow into a noisy army of oversharers. Raised on a steady diet of social media TMI, we were expected to lump fuddy-duddy ideas about privacy and discretion in with bell-bottoms and shoulder pads -- peculiar things our parents were into once. At the rate we were going back then, and judging by the way adults rolled their eyes at us, we should be broadcasting from the bathroom by now.

But when I poke through 10 years of Facebook, I see something else altogether. We're not an oversharing generation. We're a generation that's over sharing -- done, finished, kaput, through. Instead of feeding Zuckerberg's beast an ever expanding range of intimate details from our lives and believing in his promise that baring all would help us bond, we've covered up. All the chatty candor and hyperactive disclosure of our early years on Facebook now look like just another kind of youthful indulgence, like cargo shorts and spray tans, that we embraced once, tired of, then cast aside.

* * *

In the beginning, TheFacebook.com was to college students what fire must have been to early man: empowering and impossible to look away from. Anyone who tells you otherwise either is being deliberately contrary or was a more socially well-adjusted person than I.

As someone who spent (OK, spends) too much time wondering whether everyone I know is having fun out without me, Facebook was a gift from the benevolent nerd-gods of Harvard University. I could socialize without having to be invited anywhere, join conversations I wasn't having and learn inside jokes from the outside. Even better: for the first time, I could exist, constantly and continuously, like some sort of nagging worry, in the minds of all the people I cared about.

Which is how I ended up with so many photos in albums with names like "flowmentum" or "How Cool Is THAT?!" Facebook was a 24-hour party and our digital doubles were its 24-hour party people, all vying to be the most intriguing invitee on the guest list. We used Facebook to create more hilarious, attractive, popular-seeming versions of ourselves, then deployed them to be checked out, invited places and flirted with. NASA's Saturn V was great and all, but this Facebook thing -- here was a truly miraculous engineering breakthrough, a pinnacle of human ingenuity that offered, at last, a means of telling the world about all the very cool, very flowmentum-y things we were doing, without needing anyone to ask, much less care.

Yet cycling through my Facebook time capsule, I see that sometime around the fall of 2009, my flood of then-awesome/now-mortifying photos all but stopped. In 2008, I posted or was tagged in around nine dozen photos. Last year, that number dropped to a measly eight. Not eight dozen -- just eight pictures, total.

I immediately conclude that the Great Photo Shortage of 2013 occurred because I've become a tragically lame person. I'm working now, as are my friends, who on the whole have similarly anemic photo albums. But then I remember the adventures I had in the months where, according to Facebook, I'd done nothing worth recording. I congratulate myself. I am, at least for now, still fun.

Then a happier explanation strikes me. I and my peers have become mature, self-assured grownups, no longer desperate to impress one another with our enormous groups of friends or stylish ways. But then everything ever posted in the history of the insta-sucess Instragram tells me that's not it either: picture after pretty picture of pretty people in pretty places doing pretty fancy things to make others pretty jealous of their pretty fancy lives.

In fact, what I gather from the staid sharing I see on present-day Facebook is that Zuckerberg was wrong about the thing he arguably wanted to change most of all -- and even claimed he had changed: our generation's eagerness to make everything known.

The pictures I dug up on Facebook appalled me not because they were in any way illicit or incriminating. Their intimacy distressed me. I can't believe my younger self's candor, my willingness to share so much of what I did with my life. Now, those vacation pictures or dinner party snapshots would be whisked away to the safety of a Dropbox for invitation-only viewing.

Nor am I the lone recluse. The Pew Research Center celebrated Facebook's double-digit birthday by asking 1,800 people what they strongly disliked about the social network. The top five gripes all had to do with feeling over-exposed online.

Four years ago, Zuckerberg declared that privacy was no longer a "social norm," as though saying it would make it true.

It hasn't. For all the ways Facebook has supposedly changed us over the past 10 years -- the surge in narcissism, loneliness, bullying, insert-your-favorite-malady-here -- it hasn't loosened our grip on our own personal lives, or on our desire for carefully staged identities. I'm not saying we don't share things, or even personal things. That would be absurd. But whether it's out of concern for keeping our jobs or fear of who's lurking among our 857 friends (most of whom we don't even remember), I see a Facebook generation less inclined than ever to make their lives an open book. More so than just a few years ago, our online personas are meticulously assembled characters acting out whatever story we write for them.

People still share up the wazoo. They just aren't sharing their, ahem, wazoos the way they used to. What we've discovered is that anything we say or do can and will be used against us -- in a court of law, at the office, during a party, by a boyfriend, or by the friend who wasn't invited to dinner. It's easier to be selective about what we share than to deal with the fallout from a photo that hurts feelings or, now that we're adults with careers, gets us fired. Besides, with so many other ways of telling the world about what we're up to -- erasable Snapchats, private Picasa albums, one-on-one WhatsApp -- why go to the biggest, most public social network of them all?

In 2011, Facebook presented us with all the tools we needed to build an even more comprehensive time capsule. This one would archive for posterity every news story read, song listened to, movie watched, outfit considered, or piercing received. It encouraged us to add pivotal "Life Events" to our profiles, like going out on a first date or getting contact lenses. I could, thanks to Facebook, remember not only that great day where life changed irreversibly for the better, but even see what Bruce Springsteen song I'd been listening to a mere minutes before I picked up my Acuvue.

And what did we do with this glorious ability? Nothing. The products, almost without exception, tanked. Instead, we demonstrated the impulse for total artistic license that Friedrich Nietzsche described a century ago. We want, he wrote, "to be the poets of our lives, and first of all in the smallest and most commonplace matters."

Pay attention next time you take a photograph. You can actually chart the Facebook generation's shift away from sharing by the exhortations that accompany the pressing of a camera's shutter.

"Promise to tag this!" people used to beg as they lined up shoulder-to-shoulder in front of the lens. That gave way to, "Swear you won't tag me." Now, no one says anything: It's just assumed no one would be so vulgar, so mean-spirited as to capture this moment, put your name on it and let the world see what you were up to. Perhaps in the digital sense, just like in every other dimension, we really are turning into our parents. Pass the shoulder pads.

Huge mistake. Nothing could have prepared me for the heart palpitations. I tried to tilt my screen away from my coworkers to shield them from the hundreds of photos I had, in some four-year-long lapse of judgment following high school, allowed posted of me -- sticking out my tongue, flopping on couches, stuffing my face with food, wearing too-short tops, strenuously trying to look effortlessly glamorous, attempting to show I was having an amaaaaazing time (whoooo!!!) and, all in all, trying much, much too hard (WHOO WHOOOO!!!!). There was an album titled -- I'm cringing even now -- "Bro'ing and Ho'ing out - Spring Break '07."

I sent friends a volley of texts demanding to know to why they hadn't confiscated my computer when I'd first shown an inclination for photographic self-destruction. "omg I know," my roommate from junior year of college wrote back. "also -- TEN YEARS AHH."

Allow me to translate. Flipping through Facebook, awkward as it was, brought to mind something that hadn't occurred to us in years: Facebook used to be fun. Somewhere along the way, it got boring. Or, more accurately, we did.

As I scrolled through my profile to the present day, the unspeakable stuff began to disappear, replaced by retouched snaps from weddings and bland party pictures from tech conferences.

My generation, the first on Facebook, was supposed to grow into a noisy army of oversharers. Raised on a steady diet of social media TMI, we were expected to lump fuddy-duddy ideas about privacy and discretion in with bell-bottoms and shoulder pads -- peculiar things our parents were into once. At the rate we were going back then, and judging by the way adults rolled their eyes at us, we should be broadcasting from the bathroom by now.

But when I poke through 10 years of Facebook, I see something else altogether. We're not an oversharing generation. We're a generation that's over sharing -- done, finished, kaput, through. Instead of feeding Zuckerberg's beast an ever expanding range of intimate details from our lives and believing in his promise that baring all would help us bond, we've covered up. All the chatty candor and hyperactive disclosure of our early years on Facebook now look like just another kind of youthful indulgence, like cargo shorts and spray tans, that we embraced once, tired of, then cast aside.

* * *

In the beginning, TheFacebook.com was to college students what fire must have been to early man: empowering and impossible to look away from. Anyone who tells you otherwise either is being deliberately contrary or was a more socially well-adjusted person than I.

As someone who spent (OK, spends) too much time wondering whether everyone I know is having fun out without me, Facebook was a gift from the benevolent nerd-gods of Harvard University. I could socialize without having to be invited anywhere, join conversations I wasn't having and learn inside jokes from the outside. Even better: for the first time, I could exist, constantly and continuously, like some sort of nagging worry, in the minds of all the people I cared about.

Which is how I ended up with so many photos in albums with names like "flowmentum" or "How Cool Is THAT?!" Facebook was a 24-hour party and our digital doubles were its 24-hour party people, all vying to be the most intriguing invitee on the guest list. We used Facebook to create more hilarious, attractive, popular-seeming versions of ourselves, then deployed them to be checked out, invited places and flirted with. NASA's Saturn V was great and all, but this Facebook thing -- here was a truly miraculous engineering breakthrough, a pinnacle of human ingenuity that offered, at last, a means of telling the world about all the very cool, very flowmentum-y things we were doing, without needing anyone to ask, much less care.

Yet cycling through my Facebook time capsule, I see that sometime around the fall of 2009, my flood of then-awesome/now-mortifying photos all but stopped. In 2008, I posted or was tagged in around nine dozen photos. Last year, that number dropped to a measly eight. Not eight dozen -- just eight pictures, total.

I immediately conclude that the Great Photo Shortage of 2013 occurred because I've become a tragically lame person. I'm working now, as are my friends, who on the whole have similarly anemic photo albums. But then I remember the adventures I had in the months where, according to Facebook, I'd done nothing worth recording. I congratulate myself. I am, at least for now, still fun.

Then a happier explanation strikes me. I and my peers have become mature, self-assured grownups, no longer desperate to impress one another with our enormous groups of friends or stylish ways. But then everything ever posted in the history of the insta-sucess Instragram tells me that's not it either: picture after pretty picture of pretty people in pretty places doing pretty fancy things to make others pretty jealous of their pretty fancy lives.

In fact, what I gather from the staid sharing I see on present-day Facebook is that Zuckerberg was wrong about the thing he arguably wanted to change most of all -- and even claimed he had changed: our generation's eagerness to make everything known.

The pictures I dug up on Facebook appalled me not because they were in any way illicit or incriminating. Their intimacy distressed me. I can't believe my younger self's candor, my willingness to share so much of what I did with my life. Now, those vacation pictures or dinner party snapshots would be whisked away to the safety of a Dropbox for invitation-only viewing.

Nor am I the lone recluse. The Pew Research Center celebrated Facebook's double-digit birthday by asking 1,800 people what they strongly disliked about the social network. The top five gripes all had to do with feeling over-exposed online.

Four years ago, Zuckerberg declared that privacy was no longer a "social norm," as though saying it would make it true.

It hasn't. For all the ways Facebook has supposedly changed us over the past 10 years -- the surge in narcissism, loneliness, bullying, insert-your-favorite-malady-here -- it hasn't loosened our grip on our own personal lives, or on our desire for carefully staged identities. I'm not saying we don't share things, or even personal things. That would be absurd. But whether it's out of concern for keeping our jobs or fear of who's lurking among our 857 friends (most of whom we don't even remember), I see a Facebook generation less inclined than ever to make their lives an open book. More so than just a few years ago, our online personas are meticulously assembled characters acting out whatever story we write for them.

People still share up the wazoo. They just aren't sharing their, ahem, wazoos the way they used to. What we've discovered is that anything we say or do can and will be used against us -- in a court of law, at the office, during a party, by a boyfriend, or by the friend who wasn't invited to dinner. It's easier to be selective about what we share than to deal with the fallout from a photo that hurts feelings or, now that we're adults with careers, gets us fired. Besides, with so many other ways of telling the world about what we're up to -- erasable Snapchats, private Picasa albums, one-on-one WhatsApp -- why go to the biggest, most public social network of them all?

In 2011, Facebook presented us with all the tools we needed to build an even more comprehensive time capsule. This one would archive for posterity every news story read, song listened to, movie watched, outfit considered, or piercing received. It encouraged us to add pivotal "Life Events" to our profiles, like going out on a first date or getting contact lenses. I could, thanks to Facebook, remember not only that great day where life changed irreversibly for the better, but even see what Bruce Springsteen song I'd been listening to a mere minutes before I picked up my Acuvue.

And what did we do with this glorious ability? Nothing. The products, almost without exception, tanked. Instead, we demonstrated the impulse for total artistic license that Friedrich Nietzsche described a century ago. We want, he wrote, "to be the poets of our lives, and first of all in the smallest and most commonplace matters."

Pay attention next time you take a photograph. You can actually chart the Facebook generation's shift away from sharing by the exhortations that accompany the pressing of a camera's shutter.

"Promise to tag this!" people used to beg as they lined up shoulder-to-shoulder in front of the lens. That gave way to, "Swear you won't tag me." Now, no one says anything: It's just assumed no one would be so vulgar, so mean-spirited as to capture this moment, put your name on it and let the world see what you were up to. Perhaps in the digital sense, just like in every other dimension, we really are turning into our parents. Pass the shoulder pads.

Published on February 04, 2014 04:35

January 29, 2014

Facebook's Plan For Artificial Intelligence: Transcribe Your Calls, Decipher Your Photos

On Facebook's earnings call Wednesday afternoon, Mark Zuckerberg offered a peek at the social network's long-term plans for artificial intelligence. And just as we explained in November, Facebook hopes AI will help it more thoroughly understand the meaning of everything you share, from gauging your mood by the words in your status update, to picking out a Coke can in your photos.

Facebook has been working to expand its artificial intelligence research lab, and last month appointed a renowned researcher with expertise in deep learning to oversee it. Deep learning is a sub-field within AI that focuses on training computers to make sense of the many messy, undefined and irregular types of data we humans generate, such as when we speak, write, photograph or film. (Teaching a computer to recognize a cat, for example, turns out to be an extremely difficult problem.)

So what would Facebook do with deep learning capabilities? Get to know you much, much better by more effectively analyzing every item you share, according to Zuckerberg's clues.

"The goal really is just to try to understand how everything on Facebook is connected by understanding what the posts that people write mean and the content that's in the photos and videos that people are sharing," Zuckerberg explained to analysts and investors on the call. "The real value will be if we can understand the meaning of all the content that people are sharing, we can provide much more relevant experiences in everything we do."

Let's try to unpack some of those generalities. In a sense, you can imagine a deep learning-enhanced Facebook as a jealous ex who stalks and overanalyzes your every online move. Instead of merely knowing you'd shared a photo, Facebook might be able to figure out that the snapshot showed a beach, along with a picture of your ex-boyfriend and that you two were smiling. When, a few days later, you post a status update, Facebook could perhaps analyze your phrasing to guess that you're lonely and depressed. And before long, you might be seeing ads for dating sites, antidepressants and funny films.

Zuckerberg also mentioned that AI could be used to transcribe the voice clips people share in Messenger, so people could receive them more easily.

He acknowledged that these are "pretty big tasks in AI" that Facebook's teams are working on, and noted it could be years before they're fully formed. Within the next three years, Facebook will be focused on "building new experiences for sharing," Zuckerberg said. Five years from now, he predicted, we should see Facebook's AI work reshaping our experience.

Facebook has been working to expand its artificial intelligence research lab, and last month appointed a renowned researcher with expertise in deep learning to oversee it. Deep learning is a sub-field within AI that focuses on training computers to make sense of the many messy, undefined and irregular types of data we humans generate, such as when we speak, write, photograph or film. (Teaching a computer to recognize a cat, for example, turns out to be an extremely difficult problem.)

So what would Facebook do with deep learning capabilities? Get to know you much, much better by more effectively analyzing every item you share, according to Zuckerberg's clues.

"The goal really is just to try to understand how everything on Facebook is connected by understanding what the posts that people write mean and the content that's in the photos and videos that people are sharing," Zuckerberg explained to analysts and investors on the call. "The real value will be if we can understand the meaning of all the content that people are sharing, we can provide much more relevant experiences in everything we do."

Let's try to unpack some of those generalities. In a sense, you can imagine a deep learning-enhanced Facebook as a jealous ex who stalks and overanalyzes your every online move. Instead of merely knowing you'd shared a photo, Facebook might be able to figure out that the snapshot showed a beach, along with a picture of your ex-boyfriend and that you two were smiling. When, a few days later, you post a status update, Facebook could perhaps analyze your phrasing to guess that you're lonely and depressed. And before long, you might be seeing ads for dating sites, antidepressants and funny films.

Zuckerberg also mentioned that AI could be used to transcribe the voice clips people share in Messenger, so people could receive them more easily.

He acknowledged that these are "pretty big tasks in AI" that Facebook's teams are working on, and noted it could be years before they're fully formed. Within the next three years, Facebook will be focused on "building new experiences for sharing," Zuckerberg said. Five years from now, he predicted, we should see Facebook's AI work reshaping our experience.

Published on January 29, 2014 15:56

Google's New A.I. Ethics Board Might Save Humanity From Extinction

In 2011, the co-founder of DeepMind, the artificial intelligence company acquired this week by Google, made an ominous prediction more befitting a ranting survivalist than an award-winning computer scientist.

“Eventually, I think human extinction will probably occur, and technology will likely play a part in this,” DeepMind’s Shane Legg said in an interview with Alexander Kruel. Among all forms of technology that could wipe out the human species, he singled out artificial intelligence, or AI, as the “number 1 risk for this century.”

Google’s acquisition of DeepMind came with an estimated $400 million price tag and an unusual stipulation that adds extra gravity -- and a dose of reality -- to Legg’s warning: Google agreed to create an AI safety and ethics review board to ensure this technology is developed safely, as The Information first reported and The Huffington Post confirmed. (A Google spokesman said that DeepMind had been acquired, but declined to comment further.)

Even for a company that predictably pursues unpredictable projects (see: Internet-deploying balloons), an AI ethics board marks a surprising first for Google, and has some people questioning why Google is so concerned with the morality of this technology, as opposed to, say, the ethics of reading your email.

Reading your email may be abhorrent. But AI, according to Legg and sober minds at the University of Cambridge, could pose no less than an "extinction-level" threat to "our species as a whole."

Advances in AI could one day create computers as smart as humans, ending our powerful reign as the planet’s most intelligent beings and leaving us at the mercy of superintelligent software that, designed incorrectly, could threaten our very survival. As James Barrat, author of Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era, notes, we've ruled because we're the smartest creature out there, but "when we share the planet with a creature smarter than we are, it’ll steer the future."

Before we get there, ethicists, AI researchers and computer scientists argue Google’s soon-to-be-created ethics board must consider both the moral implications of the AI projects it pursues, and draw up the ethical rules by which its smart systems operate. The robot overlords are almost certainly coming. At least Google can ensure they're merciful.

"If, in the future, a machine radically surpassed us in intelligence, it would also be extremely powerful, able potentially to shape the future and decide whether there are any more humans or not,” explains Nick Bostrom, director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford. "You need to set up the initial conditions in just the right way so that the machine is friendly to humans.”

Artificial intelligence, a generic term that encompasses over a dozen specialized sub-fields, is already powering everything from Google’s self-driving cars and speech-recognition systems to its virtual assistant and search results. (DeepMind's technology, which applies a form of AI known as "deep learning" to gaming and e-commerce, will reportedly be incorporated into search.) While today’s AI software is still worse than a toddler at simple tasks like recognizing a cat or deciphering a phrase, it’s poised for exponential improvement that, within a few decades, could have AI diagnosing patients, writing best-sellers and putting our own brains to shame.

AI experts, who hail the board as a milestone for their field, hope Google’s committee will both steer the company away from morally suspect applications of AI technology and probe the social repercussions of the products it opts to develop. Imagine, for example, if Google chose to implant sophisticated, artificially intelligent brains in the industrial robots it acquired with the purchase last year of Boston Dynamics, a firm that worked closely with the U.S. military. Google might be able to build the most sophisticated robot soldiers on the market, paving the way for man and machine to fight shoulder-to-shoulder in battle.

But should Google be in the killer-bot business? Would launching these smart slaughter-machines for the military violate Google’s “do no evil” code? Or would it be more unethical to let human soldiers die in combat when robots could take their place? These are the kinds of questions the AI arbiters might grapple with, along with issues like whether to pursue automation that would put millions out of work, or whether facial recognition could threaten individual autonomy.

Together with input from other AI researchers, Barrat has developed a wishlist of five policies he hopes Google's safety board will adopt to ensure the applications of AI are ethical. These include creating guidelines that determine when it's "ethical for systems to cause physical harm to humans," how to limit "the psychological manipulation of humans" and how to prevent "the concentration of excessive power."

With AI poised to reason, learn, create, drive, speak, comfort and possibly even decide who dies, the world also needs a moral code for the computer code.

As Gary Marcus has noted in the New Yorker, sophisticated AI systems, such as self-driving cars, will increasingly face difficult moral decisions, like choosing whether to crash a school bus carrying kids, or risk harming the passenger the car has onboard. Software will have to be programmed to behave by a set of ethical principles, which the AI committee could help conceive.

“People ridicule terminator scenarios in which machines actively oppose us or disregard us. I don’t think we can afford to ignore those things or laugh them off,” says Marcus, a psychology professor at New York University and author of Kluge: The Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind. “In a driverless car -- or in any machine that has a certain power to control the world -- you want to make sure that the machine makes ethical decisions.”

The technical challenges of that are daunting. But even more complex may be deciding whose values inform the moral code of the intelligent machines who could be our teachers, caretakers and chauffeurs. As it is, Google's definition of proper and ethical behavior doesn't always jive with the rest of the world's -- just ask the FTC, the House, the German government, France's judges, and privacy commissioners from seven countries... While Google might be A-OK with, say, an AI virtual assistant that carries on "Her"-like trysts with married users, others of us might want to bar computers from being home-wreckers. But then who would we trust to develop a "10 commandments" for ethical AI? Do we trust governments to bear that responsibility? Religious leaders? Academics? Whoever decides will likely impact human life as much as the workings of the AI.

And even then, ensuring the ethics board has real influence within Google could be another issue. Sources familiar with the DeepMind acquisition noted that the startup's shareholders have some power to hold Google to its promise: Dismissing the guidance of the AI safety and ethics board could reportedly prompt legal action over a violation of the terms of the sale.

A handful of DeepMind funders and founders -- including co-founders Legg and Demis Hassabis, and backers Jaan Tallinn and Peter Thiel -- have consistently worked to raise awareness about the potential risks of uncontrolled AI development, so there's reason to believe they will urge Google to abide by its new board.

But if for some reason Google does ignore the safety committee's advice, and our artificially intelligent overlords do one day try to exterminate us, Legg predicts there'd be a silver lining to our species' demise.

"If a superintelligent machine (or any kind of superintelligent agent) decided to get rid of us," he wrote, "I think it would do so pretty efficiently."

“Eventually, I think human extinction will probably occur, and technology will likely play a part in this,” DeepMind’s Shane Legg said in an interview with Alexander Kruel. Among all forms of technology that could wipe out the human species, he singled out artificial intelligence, or AI, as the “number 1 risk for this century.”

Google’s acquisition of DeepMind came with an estimated $400 million price tag and an unusual stipulation that adds extra gravity -- and a dose of reality -- to Legg’s warning: Google agreed to create an AI safety and ethics review board to ensure this technology is developed safely, as The Information first reported and The Huffington Post confirmed. (A Google spokesman said that DeepMind had been acquired, but declined to comment further.)

Even for a company that predictably pursues unpredictable projects (see: Internet-deploying balloons), an AI ethics board marks a surprising first for Google, and has some people questioning why Google is so concerned with the morality of this technology, as opposed to, say, the ethics of reading your email.

Reading your email may be abhorrent. But AI, according to Legg and sober minds at the University of Cambridge, could pose no less than an "extinction-level" threat to "our species as a whole."

Advances in AI could one day create computers as smart as humans, ending our powerful reign as the planet’s most intelligent beings and leaving us at the mercy of superintelligent software that, designed incorrectly, could threaten our very survival. As James Barrat, author of Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era, notes, we've ruled because we're the smartest creature out there, but "when we share the planet with a creature smarter than we are, it’ll steer the future."